Abstract

Background

Early detection of herbicide resistance in weeds is crucial for successful implementation of integrated weed management. We conducted a herbicide resistance survey of the winter annual grasses feral rye (Secale cereale), downy brome (Bromus tectorum), and jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica) from Colorado winter wheat production areas for resistance to imazamox and quizalofop.

Results

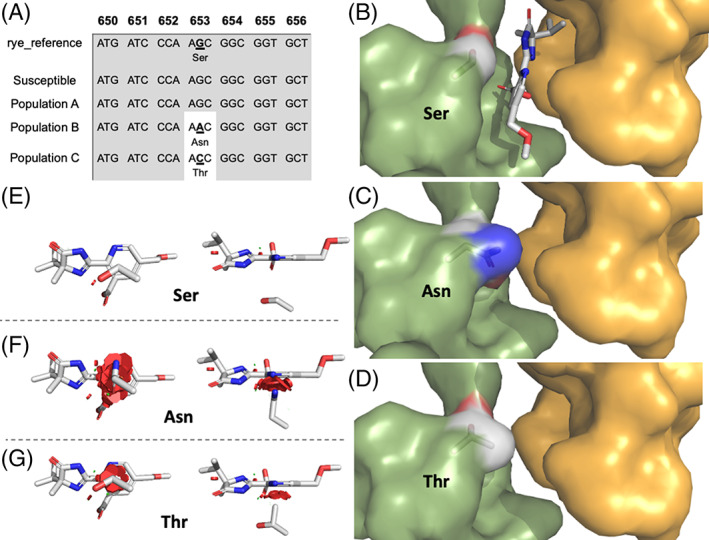

All samples were susceptible to quizalofop. All downy brome and jointed goatgrass samples were susceptible to imazamox. Out of 314 field collected samples, we identified three feral rye populations (named A, B, and C) that were imazamox resistant. Populations B and C had a target‐site mechanism with mutations in the Ser653 residue of the acetolactate synthase (ALS) gene to Asn in B and to Thr in C. Both populations B and C had greatly reduced ALS in vitro enzyme inhibition by imazamox. ALS feral rye protein modeling showed that steric interactions induced by the amino acid substitutions at Ser653 impaired imazamox binding. Individuals from population A had no mutations in the ALS gene. The ALS enzyme from population A was equally sensitive to imazamox as to known susceptible feral rye populations. Imazamox was degraded two times faster in population A compared with a susceptible control. An oxidized imazamox metabolite formed faster in population A and this detoxification reaction was inhibited by malathion.

Conclusion

Population A has a nontarget‐site mechanism of enhanced imazamox metabolism that may be conferred by cytochrome P450 enzymes. This is the first report of both target‐site and metabolism‐based imazamox resistance in feral rye. © 2022 The Authors. Pest Management Science published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Society of Chemical Industry.

Keywords: nontarget‐site resistance, metabolic resistance, Clearfield wheat, cytochrome P450, target‐site resistance

A resistance survey in winter annual grasses identified three feral rye populations resistant to imazamox. Resistance mechanism investigations showed populations B and C contained an amino acid substitution at Ser653 in the ALS gene, whereas population A showed imazamox‐enhanced metabolism.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALS

acetolactate synthase

- ACCase

acetyl‐coenzyme A carboxylase

- UAN

urea ammonium nitrate

- MSO

methylated seed oil

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- GR50

inhibition 50% of biomass

1. INTRODUCTION

Herbicide resistance surveys in weeds are essential for early detection of resistant biotypes to inform proactive mitigation practices in agricultural fields. 1 Winter annual grasses such as feral rye (Secale cereale L.), downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.), and jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica Host) are troublesome weed species in winter wheat. 2 , 3 In addition to competing with wheat for resources, contaminating seeds from feral rye and jointed goatgrass in harvested grain can result in payment penalties. Jointed goatgrass can hybridize with wheat as these two species are partially genetically compatible, increasing the risk of interspecific gene flow and low grain quality. 4 , 5

Control of winter annual downy brome, feral rye, and jointed goatgrass in winter wheat is challenging due to similar growth cycles and a lack of selective post‐emergence herbicides. Downy brome can be controlled in wheat with several selective Group 2 acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibiting herbicides, but selective control of feral rye and jointed goatgrass can only be obtained using wheat varieties with herbicide resistance traits. The first option available was Clearfield wheat, 6 with resistance to imazamox, 7 which has been utilized since 2002. 8 Imazamox is an imidazolinone herbicide that inhibits ALS (also referred as acetohydroxyacid synthase or AHAS), blocking synthesis of the branched chain amino acids valine, leucine, and isoleucine. 9 Imazamox provides excellent control of downy brome and jointed goatgrass, whereas feral rye is labeled for suppression rather than control. This difference in imazamox efficacy between species is related to less translocation and a higher metabolism rate in feral rye than in jointed goatgrass. 10 Quizalofop‐resistant wheat varieties carrying a target‐site mutation in two of three wheat acetyl‐coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCase) genes have been commercialized (trade name CoAXium wheat production system). 11 The target site mutation in ACCase (Ala2004Val) alters the binding affinity of quizalofop for the enzyme. 12 Additionally, quizalofop‐resistant winter wheat varieties can also metabolize quizalofop. The detoxification rate depends on atmospheric temperature, with less rapid metabolism at lower temperatures. 13 Quizalofop‐p‐ethyl (quizalofop) is part of the Group 1 aryloxyphenoxypropionate chemical family and is used to control grass weeds. This herbicide mode of action is related to fatty acid biosynthesis through inhibition of ACCase. 14 Field experiments with quizalofop on resistant wheat varieties reported good control of downy brome, jointed goatgrass, and feral rye, with no crop injury in the tested varieties. 15 , 16

ALS and ACCase inhibitors have a higher probability of resistance evolution compared to other modes of action based on application frequency and reported cases. 17 These two modes of action are ranked as the first and third for the most resistance cases reported, with 165 and 49 weed species resistant to ALS and ACCase inhibitors, respectively. 18 Target‐site and nontarget‐site resistance mechanisms to ACCase and ALS herbicides have been described in several weed species. 19 Target‐site mechanisms refer to mutations that lead to a change in the binding affinity between the herbicide and its enzyme target, whereas nontarget‐site mechanisms are related to pathways to reduce the amount of herbicide reaching the target enzyme such as limited absorption and cellular transport, organelle sequestration, or detoxification by enhanced metabolism. Eleven mutations conferring resistance to one or more chemical families of the ACCase inhibitors have been identified in the homomeric plastidic ACCase carboxyltransferase domain in grasses, which is the herbicide site of action. 20 Several target‐site mutations have been documented that confer resistance to ALS herbicides. 21 ALS herbicides are noncompetitive inhibitors that bind in the channel leading to the substrate active site, with higher initial mutation frequency and diversity of possible mutations conferring target‐site resistance as the mutations occur outside of the catalytic domain and have minimal effects on normal protein function. 22 Nontarget‐site mechanisms for ACCase and ALS herbicides are primarily related to metabolic detoxification pathways. 23

In the Western United States winter wheat production region there are no reports of quizalofop‐resistant weed species. Three Bromus spp. populations and one jointed goatgrass population have been reported resistant to imazamox in this cropping system. 18 , 24 , 25 Currently, there is no information on imazamox and quizalofop resistance status for feral rye, downy brome, and jointed goatgrass in Colorado winter wheat. A herbicide resistance survey was conducted to determine both imazamox resistance status after nearly two decades of imazamox‐resistant winter wheat systems and initial quizalofop resistance status after the commercial release in 2018 of quizalofop‐resistant wheat varieties. Our objectives were (i) to conduct a herbicide resistance survey for identification of winter annual grasses resistant to imazamox and quizalofop, and (ii) to characterize the resistance mechanisms from resistant biotypes identified in the survey.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Herbicide resistance survey

To evaluate possible cases of resistance to quizalofop or imazamox, a total of 44 downy brome, 22 jointed goatgrass, and 251 feral rye samples were screened from Colorado winter wheat fields. Samples were collected during the summers of 2012, 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2019 (Table 1). Although this resistance survey focused on winter wheat cropping systems, some feral rye samples from 2012 and 2016 were collected from roadsides, rangelands, and natural areas in Colorado, resulting in higher total sample numbers for feral rye. Seeds (120) from each sample were planted in 60 × 30 cm trays filled with potting soil (Farfard #2‐SV; American Clay Works, Denver, CO, USA) for each herbicide. Plants were grown in a greenhouse under a photoperiod regimen of 14 h light/10 h dark and temperatures maintained between 22 and 26 °C. Trays were watered daily to maintain normal plant growth. Quizalofop (Aggressor; Albaugh, LLC Ankeny, IA, USA) and imazamox (Beyond®; BASF, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) application rates were based on commercial label recommendations to control downy brome, feral rye, and jointed goatgrass. Quizalofop and imazamox were applied at 62 and 53 g ai ha−1, respectively. In addition, 0.25% (v/v) nonionic surfactant and 2.5% (v/v) urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) were used as adjuvants for quizalofop, and 1% (v/v) methylated seed oil (MSO) and 5% (v/v) UAN were used for imazamox. Plants were treated when they reached three true leaves. Herbicides were sprayed using a cabinet spray chamber (DeVries Generation III Research Sprayer, Hollandale, MN, USA) with a XR TeeJet 11002 VS nozzle calibrated to deliver 187 L ha−1. Survival percentage was determined at 3–4 weeks after treatment. Plants that had no or very low herbicide injury were subject to a second herbicide application after survival evaluation using the same rates (quizalofop at 62 g ai ha−1, imazamox at 53 g ai ha−1). A regrowth assessment was conducted by pruning plants above 4 cm at 1 week after treatment and measuring regrowth to rule out possible escapes and confirm the resistant phenotypes. Populations were classified as resistant if they had survival >1%.

Table 1.

Quizalofop and imazamox resistance survey sample collection and resistance screening results for downy brome, jointed goatgrass, and feral rye by year

| Winter annual grass species | Number of resistant populations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | |||||||

| Collection year | Downy brome | Jointed goatgrass | Feral rye | Quizalofop | Imazamox | Imazamox % survival | |

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2015 | 18 | 12 | 20 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2016 | 26 | 10 | 38 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2018 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 0 | 2 | Feral rye population A | 27% |

| Subsample A1 (n = 77) | 1% | ||||||

| Subsample A2 (n = 58) | 81% | ||||||

| Subsample A3 (n = 71) | 30% | ||||||

| Subsample A4 (n = 68) | 7% | ||||||

| Feral rye population B | 76% | ||||||

| Subsample B1 (n = 12) | 92% | ||||||

| Subsample B2 (n = 7) | 100% | ||||||

| Subsample B3 (n = 54) | 89% | ||||||

| Subsample B4 (n = 55) | 96% | ||||||

| Subsample B5 (n = 57) | 84% | ||||||

| Subsample B6 (n = 68) | 88% | ||||||

| Subsample B7 (n = 68) | 9% | ||||||

| Subsample B8 (n = 88) | 88% | ||||||

| 2019 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1 | Feral rye population C | 56% |

| Total | 44 | 22 | 251 | 0 | 3 | ||

Resistant populations are defined as those with individual survival >0% following herbicide treatment with quizalofop at 62 g ai ha−1 or imazamox at 53 g ai ha−1.

2.2. Feral rye imazamox‐resistant population characterization

2.2.1. Dose‐response experiment

Based on the survey results, three feral rye populations (populations A, B, and C) were identified as imazamox resistant. A dose response experiment was conducted to characterize the resistance level from populations A, B, and C compared with a susceptible population that was identified in the survey. Imazamox application rates were 0, 13, 26, 52, 105, 210, 315, 420, and 525 g ai ha−1 combined with the same adjuvants as described above. Four seedlings were placed in a 3.8 × 3.8 × 5.8 cm pot filled with the same potting soil type used for the screening. Each pot was considered a biological replication. Each treatment included three replications for a total of 12 plants. In addition, for populations A and B the same imazamox rates were used in combination with malathion at 1000 g ha−1 as a cytochrome P450 inhibitor to identify potential metabolic resistance. The same procedure as described above was followed, with malathion applied in a mixture with the herbicide. Plants from imazamox and imazamox plus malathion dose responses were pruned at 4 cm height at 1 week after treatment to quantify the fresh weight only of the regrowth biomass at 3 weeks after treatment. The imazamox dose response for populations A and B was replicated twice and the imazamox plus malathion dose response was conducted once. The dose response for population C was conducted once.

2.2.2. ALS enzyme activity assay

A modified in vitro assay was conducted to assess ALS inhibition by imazamox for populations A and B, compared with a susceptible control, using a colorimetric estimation of acetoin, the reaction product after acetolactate decarboxylation. 26 One gram of plant meristem tissue was collected. Tissue was flash frozen, ground to powder texture in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C. An extraction buffer composed of deionized water, 25 mmol L−1 potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 4 mmol L−1 thiamine phosphate, 200 mmol L−1 pyruvate, 5 mmol L−1 magnesium chloride, and 20 μmol L−1 flavin adenine dinucleotide was continuously stirred and the pH was adjusted to 7. Tissue powder was mixed with 5 mL of the extraction buffer, vortexed vigorously for 1 min, and incubated on ice for 15 min. The homogenate was filtered through a cheese cloth and centrifuged at 16 000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant containing the crude protein extract was pipetted into a separate tube and used immediately for the enzyme assay. A 10 mmol L−1 commercial imazamox 7 stock solution was mixed with the buffer extraction to reach a 1 mmol L−1 final herbicide concentration. The ALS inhibition assay was conducted in a 96‐deep well plate, where 125 μL of the extraction buffer was added to each well. A herbicide concentration gradient of 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 63, 125, 250, and 500 μmol L−1 was made by adding 125 μL of the 1 mmol L−1 imazamox solution to the first row in the plate. The extraction buffer and herbicide solution were mixed thoroughly by pipetting and a 125‐μL aliquot was used to repeat the same process in the following row to reach the desired concentrations. In each well 125 μL of the crude protein extract was added. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The ALS inhibition reaction was stopped by adding 62.5 μL of sulfuric acid at 5% and an incubation period of 15 min at 60 °C. To continue the acetolactate derivatization to acetoin, a fresh 2 N sodium hydroxide solution was mixed with α‐naphthol and creatine at 2.5% (v:w) and 0.25% (v:w), respectively. Each well received 437.5 μL of this solution and underwent an incubation period of 15 min at 60 °C. After incubation the plate was centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 × g. Aliquots of 250 μL were pipetted into UV‐transparent microplates to measure absorbance at 530 nm with a spectrophotometer (BioTek Sinergy 2, Winooski, VT, USA). Total crude protein was measured for each biological replication using the Bradford assay. 27 The ALS activity as a percentage of control was calculated by subtracting the background from the control samples and normalized by total crude protein. Three biological replications per population were used.

2.3. Target‐site and nontarget‐site resistance mechanism in feral rye

2.3.1. Target‐site investigation: ALS gene sequencing and ALS protein modeling

Partial ALS gene sequencing was conducted to identify possible target‐site mutations. A 160 bp region containing the Ser653 codon located in the conserved region of domain E was sequenced. Additional sequencing was conducted on a 1680 bp region for individuals from populations A and B to include all known ALS target‐site mutations except for Ala122. Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB protocol 28 from 15, 39, and two imazamox‐resistant plants from populations A, B, and C, respectively, and three individuals from a susceptible line. DNA quantity and quality were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For the 160 bp region, forward primer 5′AAGTCACTGCAGCAATCAAGAAG′3 and reverse primer 5′CAATACGCAGTCCTGCCAT′3 were designed to amplify the ALS gene based on the published cereal rye genome. 29 For the 1680 bp region, forward primer 5′ATCGTCGACGTCTTCGCCTAC3′ was used with the same reverse primer as above. A 50‐μL master mix containing 25 μL of GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison WI, USA), 2 μL of each forward and reverse primer at 10 μmol L−1, and 17 μL of sterile high‐performance liquid chromatography‐grade water was prepared. A total of 4 μL of DNA at 35 ng μL−1 was mixed with 46 μL of the master mix in a tube. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted in a Bio‐Rad T100 thermal cycler (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations of 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, then 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension of 5 min at 72 °C. Prior to sequencing, the amplicon size from each sample was assessed in a 1% agarose gel using electrophoresis. PCR products were purified and Sanger sequenced by Genewiz, Inc (South Plainfield, NJ, USA) using the same forward and reverse primers as described above. The resulting sequences were assembled and aligned to the cereal rye reference using Geneious R11 (Biomatters, Ltd, San Diego, CA, USA).

A feral rye ALS protein‐imidazolinone model was built to assess the interaction changes caused by the identified target site mutations. A consensus protein sequence of feral rye ALS was aligned to Arabidopsis thaliana ALS using Clustal Omega 30 and Praline 31 to identify residues involved in the binding domain of herbicides from the crystal structure of A. thaliana ALS co‐crystalized with imazaquin (1z8n). 22 A homology model of feral rye ALS was obtained as described before by generating a preliminary model using Modeller (version 10.0) 32 , 33 and an optimized model using Gromacs (version 2018.3). 34 , 35 Feral rye ALS models with the Ser653Asn and Ser653Thr mutations were derived from the original ALS homology model. The structure of imazamox was obtained from PubChem and its conformation was adjusted from imazaquin in the crystal structure. Steric interactions between imazamox and Ser653, or Asn653, and Thr653 mutants, were evaluated using the Strider algorithm 36 and van der Waals interactions were determined using the show_bumps.py script. Figures were generated in PyMOL (version 2.3.3).

2.3.2. Nontarget‐site investigation: enhanced metabolism experiment

Nontarget‐site resistance was investigated by measuring imazamox metabolites from populations A and a susceptible control. Based on the malathion treatment response and ALS enzyme activity, this was the only population identified with a potential nontarget‐site mechanism. Measured metabolites were determined based on the compounds identified in the imazamox wheat metabolism registration report. 37 They correspond to parent imazamox (CAS 114311‐32‐9), a demethylated metabolite (CAS 81335‐78‐6), a glucosylated metabolite (CAS 200111‐50‐8), and an oxidized metabolite (CAS 146953‐32‐4) (Fig. 1). Feral rye plants at the three to four true leaf stage were treated with imazamox at 62 g ai ha−1 alone and in combination with malathion at 1000 g ha−1 as a cytochrome P450 inhibitor using a spray cabinet calibrated to deliver 200 L ha−1. Aboveground biomass was harvested at 0, 1, 3, and 7 days after treatment. Tissue was washed in a 1:1 water:acetonitrile solution to quantify the nonabsorbed herbicide. Plant tissue homogenization was obtained after placing 2–3 g of diced tissue in a gentleMACS M tube (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA) with 3 mL of 1:1 water:acetonitrile solution and processing twice in a gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotech). GentleMACS M tubes were centrifuged at 4000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. A total of 2 mL of the supernatant was vacuum filtered using a 0.2 μm nylon 96‐well plate. The remaining supernatant was stored at −80 °C. Aliquots of 500 μL of plant extract were diluted to half of the concentration and placed in a microplate for mass spectrometry analysis. Metabolite quantification was conducted using an ultra‐performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) UltiMate 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) connected to a high‐resolution mass spectrometry OrbiTrap Q Exactive HF (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) with a heated electrospray source (HESI‐II). Then 10 μL of each sample was injected into the UPLC‐OrbiTrap through a PAL HTS‐xt autosampler (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland) for the analysis. The chromatographic separation was conducted with a Nucleodur C18 Pyramid column (150 × 3 mm, 3 μm) (Macherey‐Nagel, Duren, Germany) kept at a constant temperature of 40 °C using as mobile phases (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. A linear gradient of A and B was used with a flow of 600 μL min−1 as follows: 0 min (10% B) to 6 min (40% B) to 6.5 min (99% B) to 7.5 min (10% B) until the run end at 10 min. The ionization source of the mass spectrometer was set with the following parameters: polarity = positive, spray voltage = 2.7 kV, probe heater temperature = 350 °C, capillary temperature = 275 °C, sheath gas = 55, auxiliary gas = 10, and spare gas = 3. The OrbiTrap was set with the following parameters: scan range = 70–800 m/z, resolution = 30 000, Automatic Gain Control (AGC) target = 10, 6 and maximum Injection Time (IT) = 200 ms. Calibration curves for each studied compound were prepared using analytical standards with acetonitrile and plant matrix as backgrounds. The data generated from the OrbiTrap were checked for quality and processed using TraceFinder 4.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The experiment was conducted twice. The first experiment had two biological replicates per time point and the second experiment contained three biological replicates. Intact imazamox and metabolites amounts were normalized to nmol (g fresh weight)−1 (FW).

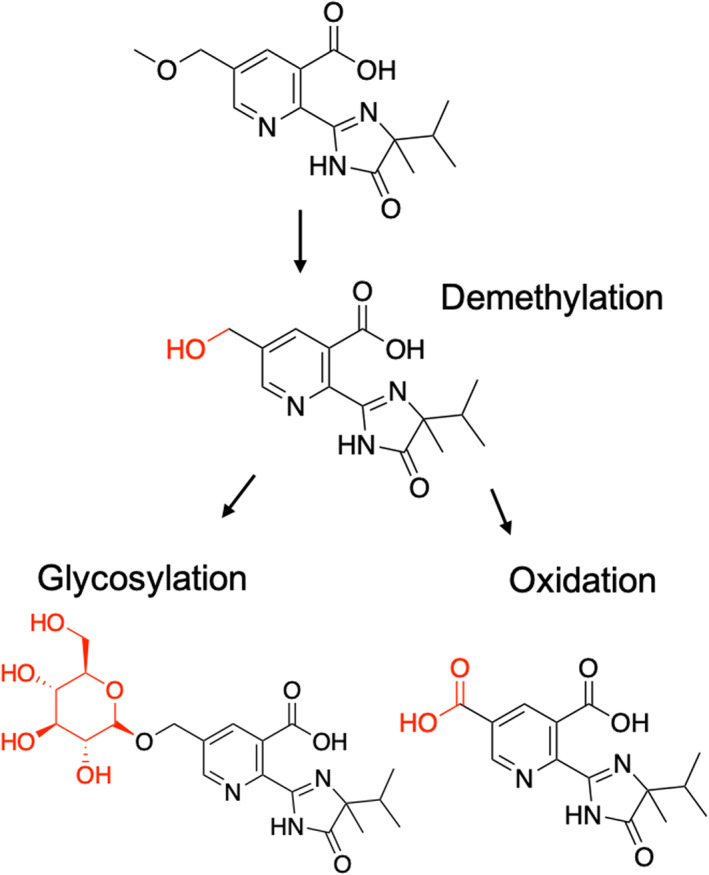

Figure 1.

Imazamox metabolic detoxification pathway in wheat. Modified from Grosshans et al. 37

2.4. Statistical analysis

Biomass data from the imazamox‐only dose response was analyzed as the percentage of untreated control fitting a three‐parameter log‐logistic regression (Eqn (1)) in R using the ‘drc’ package. 38 , 39

| (1) |

The equation parameters are defined as Y, the response variable, d is the upper limit, b is the slope, E corresponds to the amount of herbicide required to inhibit 50% growth (GR50), and x is the herbicide rate. The imazamox plus malathion dose‐response biomass data were analyzed using a two‐way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison (α = 0.05) to identify significant differences among treatments with and without malathion. The ALS activity assay was analyzed as a percentage of control. These data were subjected to nonlinear three‐parameter regression to calculate the IC50 (concentration required to inhibit 50% of the enzyme activity). Metabolism data were analyzed using a first‐order one‐phase decay model for the imazamox parent compound and a quadratic model for the three studied metabolites. The T50 (time for 50% compound degradation) of intact imazamox values were calculated based on the regression model. 40 Imazamox dose‐response graphs and the remaining statistical analysis were conducted using GraphPad Prism. 41

3. RESULTS

3.1. Quizalofop and imazamox resistance survey

All downy brome, feral rye, and jointed goatgrass samples were susceptible to quizalofop. All downy brome and jointed goatgrass populations were susceptible to imazamox. From the 251 feral rye samples, three populations were identified as imazamox‐resistant based on survival following imazamox treatment in the initial survey screening and confirmed by dose response (Table 2). Populations A and B were part of the 2018 collection and population C was from the 2019 survey (Table 1). These populations were collected from three independent farms that follow a conventional winter wheat–fallow rotation program. These farms were located in Northern Colorado within a 60‐km radius. Feral rye seed was collected from four and eight different locations (subsamples) from populations A and B, respectively, in each farm, whereas population C was obtained from one site. Survival following imazamox treatment at 53 g ai ha−1 was 27%, 76%, and 56% for populations A, B, and C, respectively.

Table 2.

Imazamox only log‐logistic three‐parameter dose response for feral rye populations A, B, C, and susceptible control

| Populations | Dose‐response model parameter estimates response variable: biomass (percent of untreated control) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d a | b a | e a (GR50) | R/S ratio | R/S P value | |

| Susceptible control | 98.2 | 3.4 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | ||

| Population A | 95.7 | 1.1 | 24.4 ± 5.17 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Population B | 96.0 | 0.6 | 164.8 ± 51.2 | 30 | 0.003 |

| Population C | 99.6 | 0.3 | 36.9 ± 31.3 | 7 | 0.321 |

d corresponds to the upper limit representing biomass at the lowest herbicide rate. b is the slope for each curve. e represents the required herbicide to inhibit 50% of biomass (GR50).

Model lack of fit test P value = 0.0704.

3.2. Imazamox resistance characterization in populations A, B, and C

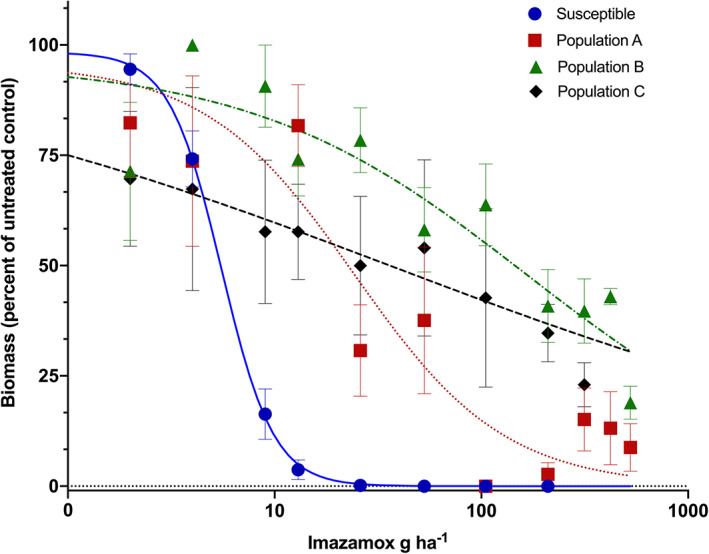

Dose‐response assays using imazamox and a mixture of imazamox and malathion were conducted to characterize the resistance levels for both populations with a cytochrome P450 inhibitor to identify possible enhanced herbicide metabolism. Imazamox‐only dose‐response curves showed that populations A, B, and C survived higher herbicide doses compared to a susceptible population (Fig. 2), with a calculated GR50 that was four, 30, and seven times higher for populations A, B, and C compared to the susceptible control (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Figure 2.

Imazamox dose‐response curves comparing biomass reduction of feral rye from populations A ( ), B (

), B ( ), and C (

), and C ( ) with a susceptible biotype (

) with a susceptible biotype ( ) at 21 days after treatment. Each data point corresponds to the mean and standard error.

) at 21 days after treatment. Each data point corresponds to the mean and standard error.

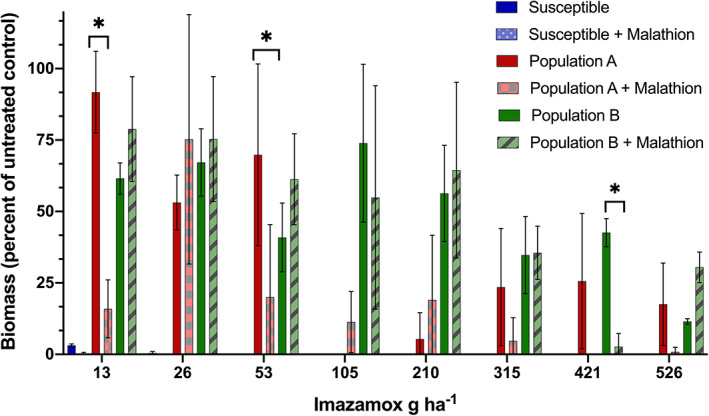

Imazamox combined with malathion dose‐response results exhibited high variability between treatments and within populations (Fig. 3). However, imazamox doses of 13 and 53 g ha−1 resulted in 76% and 50% less biomass with malathion than without malathion for population A. In population B, imazamox at 421 g ha−1 decreased biomass by 40% with malathion compared with herbicide alone. These results indicate that the malathion treatment may have inhibited cytochrome P450 enzyme activity in some individuals in populations A and B, reducing imazamox metabolism and increasing sensitivity to the herbicide. These dose‐response experiments were conducted with heterogeneous, segregating populations obtained from the field collection that contained both resistant and sensitive individuals, therefore the population mean resistance response was variable.

Figure 3.

Imazamox dose‐response of feral rye populations A and B to imazamox alone and combined with malathion at 1000 g ha−1 with differences in biomass shown as percentage of untreated control. Bars with * represent significant differences per population and among treatment based on Tukey's multiple comparison (α = 0.05) (* P value <0.005).

3.2.1. Target‐site mechanism investigation

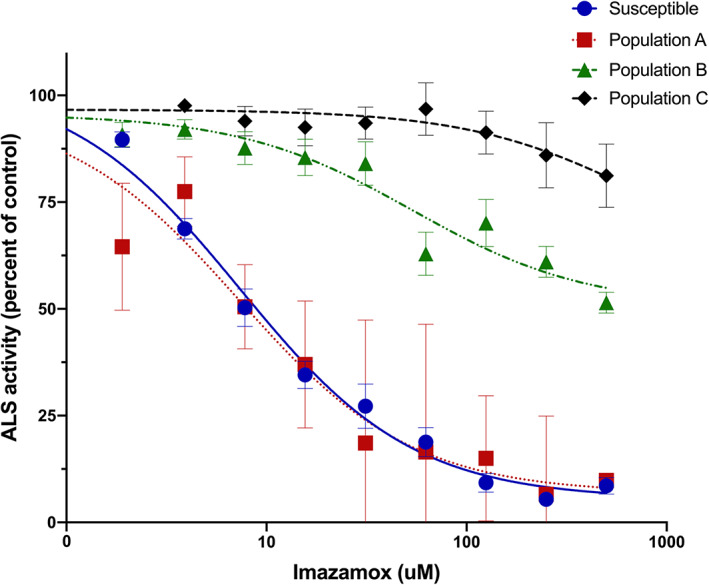

An enzyme activity assay was conducted to assess the inhibition of ALS by imazamox in vitro. Population B had an IC50 of 247 μmol L−1, whereas population A was similar to the susceptible control, with an IC50 of 16 μmol L−1 (Fig. 4). The IC50 could not be estimated for population C due to the lack of enzyme inhibition at the highest rate included in the experiment. These results suggest that populations B and C may contain a target‐site resistance mutation in the ALS gene. On the other hand, population A had a similar trend to the susceptible control, suggesting a nontarget‐site resistance mechanism.

Figure 4.

ALS enzyme activity in vitro assay from feral rye populations A ( ), B (

), B ( ), and C (

), and C ( ), and a susceptible control (

), and a susceptible control ( ). ALS activity was quantified as acetoin absorbance and calculated as a percentage based on the control. Each data point corresponds to the mean and standard error of three biological replications.

). ALS activity was quantified as acetoin absorbance and calculated as a percentage based on the control. Each data point corresponds to the mean and standard error of three biological replications.

Partial sequencing was conducted to identify possible nonsynonymous mutations in the ALS gene, comparing populations A, B, and C, a known susceptible reference, and the cereal rye reference genome ALS sequence (Fig. 5 and Appendix S1; ALS sequences available at NCBI as accessions OP186428‐OP186447). Populations B and C had a single nucleotide polymorphism in the 653 position of the ALS gene that caused a change in the amino acid sequence. In population B, the G to A nucleotide substitution changed the codon from serine to asparagine, whereas in population C, a change from G to C changed the codon to threonine (Fig. 5). No mutations in the ALS gene partial sequencing were identified in population A. All known ALS target‐site mutations were included in the partial sequencing, except for position Ala122. The population A sequences had the wild‐type codon at Pro197, Ala205, Asp376, Arg377, Trp574, Ser653, and Gly654 (Appendix S1). As individuals from population A had an ALS enzyme that was equally sensitive to imazamox inhibition as a known susceptible reference line, we consider it unlikely that a resistance‐conferring target‐site mutation at Ala 122 is present in the A population. The presence of mutations at position Ser653 in populations B and C supports the results from the ALS enzyme inhibition assay indicating a target‐site resistance mechanism in populations B and C.

Figure 5.

Partial feral rye ALS sequence alignment, target‐site mutations impact on herbicide binding domain of feral rye ALS, and visualization of steric interactions between imazamox and mutated residues. (A) Consensus alignment from the partial ALS gene nucleotide and amino acid sequencing region showing the Ser653Asn and Ser653Thr mutations from each collection site for populations A, B, and C. The numbers at the top of the graph depict the residue number based on the Arabidopsis thaliana ALS amino acid sequence. (B–D) Docking of imazamox in the channel between subunit A in green and subunit B in yellow of feral rye ALS. Coordinates from the homology model of ALS were derived from the crystal structure of A. thaliana ALS co‐crystalized with imazaquin (1z8n). The conformation of imazamox was adjusted from the coordinates of imazaquin bound in ALS. Changes in the architecture of the channel caused by the (C) asparagine and (D) threonine mutations, respectively. Imazamox is not displayed because it no longer fits the channel. (E–G) Visualization of the steric interactions (in red) between imazamox and residues at position 653. (E) Susceptible population with Ser653, (F) population B with Asn653, and (G) population C with Thr653. Van der Waals forces were 17.6 kJ mol−1 for serine in the susceptible population, 179.6 kJ mol−1 for asparagine in population B, and 72.2 kJ mol−1 for threonine in population C. Left‐hand images are views from behind the amino acid residue at position 653 and right‐hand images are views from above.

Feral rye ALS models with the Ser653Asn and Ser653Thr mutations were conducted to assess the changes in the binding site and imazamox interactions. While the sequence identity between ALS from A. thaliana and feral rye was 75%, all the amino acids involved in the binding of imazamox were identical, with the single exception of a leucine to isoleucine in one location. As the chemical properties of these two residues are very similar, this amino acid change was introduced in the homology and resulted in negligible changes in ALS structure. The Ser653Asn and Ser653Thr mutations caused significant changes to the imazamox binding region (Fig. 5). The impact of asparagine on imazamox binding to ALS was greater than the threonine mutation. Both of these mutations interfere with the binding of imazamox because of steric hindrance and excessive van der Waals forces (Fig. 5). 22

3.2.2. Nontarget‐site mechanism

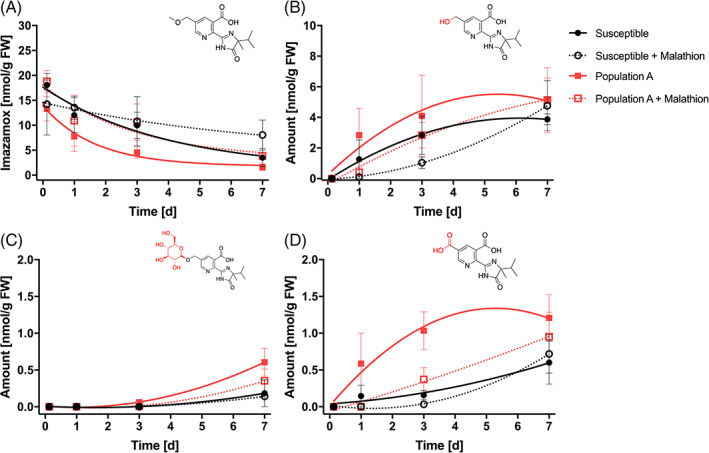

Intact imazamox and three other metabolites (Fig. 1) were measured in both the absence and presence of the P450 inhibitor malathion (Fig. 6 and Appendix S2). Susceptible plants treated with imazamox had a higher T50 for intact imazamox of 3 days than population A, which had a T50 of 1 day (t‐test 5.33, P value 0.0129). When imazamox was applied with malathion, the T50 for susceptible plants was 5 days, which was not different from susceptible without malathion. Applying imazamox in combination with malathion increased the T50 from 1 days (no malathion) to 2 days (with malathion) for population A (t‐test 4.628, P value 0.019). The demethylated, glucosylated, and oxidized metabolites followed a similar trend where population A had a greater concentration of these metabolites compared with the susceptible control, and the metabolite concentrations decreased in malathion treatments (Fig. 6 and Appendix S2). These results suggest that population A may have an enhanced metabolism mediated by cytochrome P450s as a resistance mechanism.

Figure 6.

Quantification of intact imazamox (A), demethylated metabolite (B), glucosylated metabolite (C), and oxidized metabolite (D) as nmol per g fresh weight (FW) after treatment with imazamox at 62 g ai ha−1 or imazamox 62 g ai ha−1 plus malathion 1000 g ai ha−1 at 0, 1, 3, and 7 days after treatment. Curves correspond to feral rye susceptible control ( ), susceptible control plus malathion (

), susceptible control plus malathion ( ), population A (

), population A ( ), and population A plus malathion (

), and population A plus malathion ( ). Bars represent the standard error of the mean from both experimental replications.

). Bars represent the standard error of the mean from both experimental replications.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Herbicide resistance survey

We surveyed winter annual grasses for resistance to quizalofop and imazamox across five collection years in Colorado (Table 1). No quizalofop‐resistant biotypes were identified after screening 317 samples of the three species (Table 1). This knowledge at the early stages of quizalofop‐resistant wheat varieties is relevant for the resistance stewardship program, including use of nonchemical integrated control methods such as harvest weed seed control to decrease the seed bank of these winter annual grass species. 42 Imazamox selection pressure in Colorado has been present since 2002 due to the use of imazamox‐resistant wheat systems in winter wheat. 8 We confirmed three imazamox‐resistant feral rye populations. To date, relatively few winter annual grasses in winter wheat have been reported resistant to imazamox, despite the fact that ALS inhibitors have the most reported resistance cases among all herbicide mode of action groups. 18 , 24 , 25

4.2. Target‐site mechanism investigation

Partial ALS gene sequencing identified the Ser653Asn mutation in population B and the Ser653Thr mutation in population C. No mutations were identified in population A. This result is supported by the ALS enzyme activity assay (Fig. 4), where population A had an IC50 similar to the susceptible control whereas population B required 24‐fold more imazamox to reach 50% inhibition. Similarly, at the highest imazamox concentration, the population C ALS enzyme was only inhibited by 20%. Substitutions at Ser653 confer resistance to imidazolinones, including imazamox, and have been reported in three other grass species. 43 , 44 The Ser653Asn mutation provided a high imazamox resistance level of 110‐fold compared to a susceptible population in downy brome along with cross‐resistance to other ALS chemical families such as sulfonylaminocarbonyltriazolinone and triazolopyrimidines but not to sulfonylureas. 24 Although the fitness cost associated with this specific single amino acid substitution has not been investigated in feral rye, known mutations in the ALS gene typically have little to no negative fitness cost in resistant biotypes. 45 , 46

The Ser653Asn and Ser653Thr mutations altered the architecture between the two subunits of ALS, resulting in a significant narrowing of the channel where imazamox binds (Fig. 5). While serine and threonine have similar function hydroxy groups, their physicochemical properties are different, with the additional methyl group of threonine protruding in the channel and reducing the size of the opening. As would be predicted, the presence of the much larger asparagine side chain causes an even greater occlusion of the channel. Both mutations interfere with the binding of imazamox because of steric hindrance of the residue side chains. This resulted in 10.2‐ and 4.1‐fold increased van der Waals forces for asparagine and threonine, respectively (Fig. 5). These forces prevent imazamox from binding and inhibiting ALS activity, thereby imparting resistance to this herbicide.

4.3. Nontarget site: enhanced imazamox metabolism

The ALS enzyme of imazamox‐resistant population A was equally sensitive as a susceptible line (Fig. 4). The addition of malathion to imazamox reduced plant biomass for population A compared to imazamox alone for three imazamox doses (Fig. 3). The phenotypic data for the malathion effect across herbicide doses in population A had high variation, which we attribute to heterogeneity in the field‐collected seed, which contained both susceptible and resistant individuals. Sequencing data demonstrated the absence of a Ser653 mutation in the ALS gene sequence of individuals from population A (Fig. 5). These data strongly suggested that the population A resistance mechanism was nontarget site. Metabolite analysis with and without malathion treatment in confirmed imazamox‐resistant individuals indicated that enhanced metabolic detoxification confers imazamox resistance in population A (Fig. 6).

Metabolic resistance to imazamox in other grass weeds is mediated by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. 47 , 48 Cytochrome P450s are a large protein family that have a hemethiolate co‐factor often involved in the phase I of herbicide detoxification. 19 Malathion is an insecticide used to inhibit the activity of certain cytochrome P450 subfamilies. 49 Adding malathion to imazamox increased the quantity of intact imazamox 2.3‐fold relative to imazamox treatment alone for population A, while the level of intact imazamox remained similar for the susceptible control at 3 days after treatment (Fig. 6). Imazamox underwent an O‐demethylation reaction where a methyl group was removed, leading to a demethylated imazamox with a free hydroxy group that in wheat is either oxidized to a carboxy group or conjugated to a glucose molecule by a glucosyl‐O‐d‐transferase (Fig. 1). The three metabolites quantified in population A concurred with the enhanced metabolic detoxification hypothesis, where the quantity of metabolites detected was higher when malathion was absent (Fig. 6). Although susceptible feral rye can metabolize imazamox, population A detoxifies imazamox faster than the susceptible biotype. Wheat can metabolize imazamox, 37 target‐site ALS mutations are necessary for imidazolinone‐resistant varieties as metabolism alone is not sufficient for wheat to survive imazamox treatment. The evolution of resistance to wheat‐selective herbicides due to a wheat‐like metabolic detoxification pathway such as the enhanced metabolic degradation identified in feral rye has been repeatedly observed in grass weeds. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55

The next steps to better understand this mechanism in population A will be to utilize transcriptomic and functional genomics approaches to identify the specific cytochrome P450s involved in this metabolic detoxification of imazamox in feral rye. Potential P450 candidates have been identified in other species. CYP81A24 from the grass weed Echinochloa phyllopogon (Stapf) Koso‐Pol conferred imazamox resistance when expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana. 56 CYP81A9 confers tolerance in corn to a sulfonylurea ALS herbicide. 57 CYP81A10v7 confers metabolic resistance to chlorsulfuron in Lolium rigidum. 53

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J.L. and G.A. are employees of BASF SE, which markets herbicide products containing imazamox for use in Clearfield wheat.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

Appendix S2: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the contribution of Kent Davis, crop advisor of Crop Quest, for alerting Dr Phil Westra, Colorado State University extension weed scientist, to two original suspected imazamox feral rye lack of control sites. We thank the Cold Metabolism Lab at BASF for supporting a graduate student internship for Dr Neeta Soni to conduct the metabolite detection and the undergraduate students at Colorado State University who helped with the greenhouse screening.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, reference number OP186428‐OP186447.

REFERENCES

- 1. Beckie HJ, Heap IM, Smeda RJ and Hall LM, Screening for herbicide resistance in weeds. Weed Technol 14:428–445 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lyon DJ and Baltensperger DD, Cropping systems control winter annual grass weeds in winter wheat. J Prod Agric 8:535–539 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleming GF, Young FL and Ogg AG Jr, Competitive relationships among winter wheat (Triticum aestivum), jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica), and downy brome (Bromus tectorum). Weed Sci 36:479–486 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaines TA, Henry WB, Byrne PF, Westra P, Nissen SJ and Shaner DL, Jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica) by imidazolinone‐resistant wheat hybridization under field conditions. Weed Sci 56:32–36 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mallory‐Smith C, Kniss AR, Lyon DJ and Zemetra RS, Jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica): a review. Weed Sci 66:562–573 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newhouse KE, Smith WA, Starrett MA, Schaefer TJ and Singh BK, Tolerance to imidazolinone herbicides in wheat. Plant Physiol 100:882–886 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anonymous, Beyond® herbicide product label. BASF Publication No. NVA 2009–04–191‐0084. Research Triangle Park, NC: BASF. 22 p. (2009).

- 8. Haley SD, Lazar MD, Quick JS, Johnson JJ, Peterson GL, Stromberger JA et al., Above winter wheat. Can J Plant Sci 83:107–108 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaner DL, Anderson PC and Stidham MA, Imidazolinones: potent inhibitors of acetohydroxyacid synthase. Plant Physiol 76:545–546 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pester TA, Nissen SJ and Westra P, Absorption, translocation, and metabolism of imazamox in jointed goatgrass and feral rye. Weed Sci 49:607–612 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ostlie M, Haley SD, Anderson V, Shaner D, Manmathan H, Beil C et al., Development and characterization of mutant winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) accessions resistant to the herbicide quizalofop. Theor Appl Genet 128:343–351 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bough R and Dayan FE, Biochemical and structural characterization of quizalofop‐resistant wheat acetyl‐CoA carboxylase. Sci Rep 12:679 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bough R, Gaines TA and Dayan FE, Low temperature delays metabolism of quizalofop in resistant winter wheat and three annual grass weed species. Front Agron 3:800731 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burton JD, Gronwald JW, Somers DA, Gengenbach BG and Wyse DL, Inhibition of corn acetyl‐CoA carboxylase by cyclohexanedione and aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides. Pestic Biochem Phys 34:76–85 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar V, Liu R, Manuchehri MR, Westra EP, Gaines TA and Shelton CW, Feral rye control in quizalofop‐resistant wheat in central Great Plains. Agron J 113:407–418 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hildebrandt C, Haley S, Shelton C, Westra EP, Westra P and Gaines TA, Winter annual grass control and crop safety in quizalofop‐resistant wheat varieties. Agron J 114:1374–1384 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kniss AR, Genetically engineered herbicide‐resistant crops and herbicide‐resistant weed evolution in the United States. Weed Sci 66:260–273 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heap I, The international survey of herbicide resistant weeds. Available: www.weedscience.com. 17 February 2022. (2022).

- 19. Gaines TA, Duke SO, Morran S, Rigon CAG, Tranel PJ, Küpper A et al., Mechanisms of evolved herbicide resistance. J Biol Chem 295:10307–10330 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takano HK, Ovejero RFL, Belchior GG, Maymone GPL and Dayan FE, ACCase‐inhibiting herbicides: mechanism of action, resistance evolution and stewardship. Sci Agri 78:e20190102 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy BP and Tranel PJ, Target‐site mutations conferring herbicide resistance. Plants 8:382 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCourt JA, Pang SS, King‐Scott J, Guddat LW and Duggleby RG, Herbicide‐binding sites revealed in the structure of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:569–573 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jugulam M and Shyam C, Non‐target‐site resistance to herbicides: recent developments. Plan Theory 8:417 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumar V and Jha P, First report of Ser653Asn mutation endowing high‐level resistance to imazamox in downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.). Pest Manage Sci 73:2585–2591 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez J, Hauvermale A, Carter A, Zuger R and Burke IC, An ALA122THR substitution in the AHAS/ALS gene confers imazamox‐resistance in Aegilops cylindrica . Pest Manag Sci 77:4583–4592 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dayan FE, Owens DK, Corniani N, Silva FML, Watson SB, Howell JL et al., Biochemical markers and enzyme assays for herbicide mode of action and resistance studies. Weed Sci 63:23–63 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bradford MM, A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein‐dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doyle J, DNA Protocols for Plants–CTAB Total DNA Isolation, in Molecular Techniques in Taxonomy, ed. by Hewitt GM and Johnston A. Springer, Berlin, pp. 283–293 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bauer E, Schmutzer T, Barilar I, Mascher M, Gundlach H, Martis MM, et al., Towards a whole‐genome sequence for rye (Secale cereale L.). Plant J 89:853–869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sievers F and Higgins DG, Clustal omega. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 48:3.13.11–3.13.16 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simossis VA and Heringa J, PRALINE: a multiple sequence alignment toolbox that integrates homology‐extended and secondary structure information. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W289–W294 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Šali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H and Karplus M, Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins 23:318–326 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Webb B and Sali A, Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinf 54:5.6.1–5.6.37 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B et al., GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi‐level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1:19–25 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hess B, Kutzner C, Van Der Spoel D and Lindahl E, GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load‐balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theor Comput 4:435–447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patro LPP and Rathinavelan T, STRIDER: steric hindrance and metal coordination identifier. Computational Biology and Chemistry, 98: 107686 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grosshans F, Lutz T and Possienke M, Metabolism of 14C‐Imazamox in Wheat, DocID 2012/1064722. BASF SE, Limburgerhof, Germany: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 38. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available: http://www.R-project.org/. 3.5.4 ed. (2018).

- 39. Ritz C, Baty F, Streibig JC and Gerhard D, Dose‐response analysis using R. PLoS ONE 10:e0146021 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kniss AR, Vassios JD, Nissen SJ and Ritz C, Nonlinear regression analysis of herbicide absorption studies. Weed Sci 59:601–610 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41. GraphPad Software GraphPad Prism, 8.4.2 edn. La Jolla, California, USA: (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soni N, Nissen SJ, Westra P, Norsworthy JK, Walsh MJ and Gaines TA, Seed retention of winter annual grass weeds at winter wheat harvest maturity shows potential for harvest weed seed control. Weed Technol 34:266–271 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakka S, Jugulam M, Peterson D and Mohammad A, Herbicide resistance: development of wheat production systems and current status of resistant weeds in wheat cropping systems. Crop J 7:750–760 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tranel PJ, Wright TR and Heap IM, Mutations in herbicide‐resistant weeds to ALS inhibitors. Available: http://wwwweedsciencecom 10 January 2022 (2022).

- 45. Yu Q and Powles SB, Resistance to AHAS inhibitor herbicides: current understanding. Pest Manag Sci 70:1340–1350 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vila‐Aiub MM, Neve P and Powles SB, Fitness costs associated with evolved herbicide resistance alleles in plants. New Phytol 184:751–767 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wright AA, Sasidharan R, Koski L, Rodriguez‐Carres M, Peterson DG, Nandula VK et al., Transcriptomic changes in Echinochloa colona in response to treatment with the herbicide imazamox. Planta 247:369–379 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iwakami S, Endo M, Saika H, Okuno J, Nakamura N, Yokoyama M et al., Cytochrome P450 CYP81A12 and CYP81A21 are associated with resistance to two acetolactate synthase inhibitors in Echinochloa phyllopogon . Plant Physiol 165:618–629 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Powles SB and Yu Q, Evolution in action: plants resistant to herbicides. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61:317–347 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Christopher JT, Powles SB, Liljegren DR and Holtum JA, Cross‐resistance to herbicides in annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum): II. Chlorsulfuron resistance involves a wheat‐like detoxification system. Plant Physiol 95:1036–1043 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Busi R, Porri A, Gaines TA and Powles SB, Pyroxasulfone resistance in Lolium rigidum is metabolism‐based. Pest Biochem Physiol 148:74–80 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dücker R, Zöllner P, Lümmen P, Ries S, Collavo A and Beffa R, Glutathione transferase plays a major role in flufenacet resistance of ryegrass (Lolium spp.) field populations. Pest Manage Sci 75:3084–3092 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Han H, Yu Q, Beffa R, González S, Maiwald F, Wang J et al., Cytochrome P450 CYP81A10v7 in Lolium rigidum confers metabolic resistance to herbicides across at least five modes of action. Plant J 105:79–92 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu Q and Powles S, Metabolism‐based herbicide resistance and cross‐resistance in crop weeds: a threat to herbicide sustainability and global crop production. Plant Physiol 166:1106–1118 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dücker R, Zöllner P, Parcharidou E, Ries S, Lorentz L and Beffa R, Enhanced metabolism causes reduced flufenacet sensitivity in black‐grass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) field populations. Pest Manage Sci 75:2996–3004 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dimaano NG, Yamaguchi T, Fukunishi K, Tominaga T and Iwakami S, Functional characterization of cytochrome P450 CYP81A subfamily to disclose the pattern of cross‐resistance in Echinochloa phyllopogon . Plant Mol Biol 102:1–14 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu X, Bi B, Xu X, Li B, Tian S, Wang J et al., Rapid identification of a candidate nicosulfuron sensitivity gene (Nss) in maize (Zea mays L.) via combining bulked segregant analysis and RNA‐seq. Theor Appl Genet 132:1351–1361 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

Appendix S2: Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, reference number OP186428‐OP186447.