Abstract

Solid‐state nanopores are an emerging technology used as a high‐throughput, label‐free analytical method for the characterization of protein aggregation in an aqueous solution. In this work, we used Levodopamine to coat a silicon nitride nanopore surface that was fabricated through a dielectric breakdown in order to reduce the unspecific adsorption. The coating of inner nanopore wall by investigation of the translocation of heparin. The functionalized nanopore was used to investigate the aggregation of amyloid‐β and α‐synuclein, two biomarkers of degenerative diseases. In the first application, we demonstrate that the α‐synuclein WT is more prone to form dimers than the variant A53T. In the second one, we show for the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ (Osaka mutant) that the addition of Aβ(42)‐WT monomers increases the polymorphism of oligomers, while the incubation with Aβ(42)‐WT fibrils generates larger aggregates.

Keywords: α-synuclein, aggregation, amyloid-β, nanopore, single molecule

A solid state nanopore fabricated through dielectric breackdown was coated with levodopamine and then used for the translocation of α‐synuclein wild type and A53T mutant variant, as well as for Amyloid β 42 OSAKA aggregation.

Introduction

For the past 20 years, solid‐state nanopore (SSN) technology has emerged as a high‐throughput, analytical method [1] for the characterization of free‐label bio‐macromolecules directly in solutions. [2] Such SSN can be tuned to adjust their size, and their surface properties to fit well with the analyte. [3] A classical experiment of nanopore sensing is based on the resistive pulse technique (RPS). The latter consists to immerse a single nanopore in an electrolyte solution and apply a constant voltage. The resulting ionic current is recorded as a function of time. When an analyte passes through the nanopore, it induces a perturbation of the ion current that is usually characterized by its amplitude, noted ΔI/I0, and the dwell time Δt. [4] The amplitude of the perturbation ΔI/I0 is used to estimate the analyte size through Maxwell's equation. [5] On the other hand, Δt can be used to extract the diffusion coefficient and the charge of the analyte inside the nanopore. Numerous proteins were investigated using SSN including BSA, avidin, IgG, thrombin, lysozyme, etc..[ 2d , 4h , 5 , 6 ] Further analysis of the current perturbation structure can provide additional information shape, charge, orientation, and dipole moment of the proteins.[ 4h , 7 ] In addition, SSN garnered great interest in particular for their ability to characterize the protein conformational change[ 4i , 8 ] and protein‐polyphenol binding. [9] Another interest of nanopore sensing is the investigation of the protein aggregation process [10] allowing the detection of oligomers to protofibrils.[ 4a , 10a ] Among the proteins able to easily self‐assemble, intrinsically disordered amyloid‐β (Aβ(42)) and α‐synuclein (αS) are of particular interest due to their involvement in two major neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's and Parkinson respectively). [11] SSN is considered an alternative to classical methods, essentially microscopy, for the detection of such aggregates, difficult to characterize due to their transient character and their polymorphism.

SiN nanopore was used in the identification of several populations of αS and Aβ(42) after several days of their incubation.[ 10b , 10c , 12 ] In addition, polymer nanopores were used to provide evidence for the promoting role of pyrimethanil for Aβ(42) aggregation during the lag‐phase [13] and Aβ(42) protofibril growth. [14] Recently, nanopipette‐type SSN was used to amplify the αS misfolding, thus opening a new opportunity to develop diagnosis tools for Parkinson's disease. [15]

From an experimental point of view, raw Silicon base nanopore requires oxidative treatment by piranha, ozone or plasma to increase its wettability to enable its filling electrolyte solution. For protein measurements, this treatment, combined with their low concentrations, limits the interfacial concentration of protein at the equilibrium. [4a] However, for Aβ(42) and αS, the adsorption onto the SiN surface is a far more dramatic issue since it conducts to partial or total pore clogging. [5] To prevent such clogging several strategies were employed including the deposition of the lipid bilayer [5] or TWEEN 20 surfactant [12] as well as the PEG grafting.[ 10a , 16 ] It is important to note that these functionalizations require an activation step through oxidative treatment as mentioned before. This can be done only for preformed nanopore drilled using transmission electron microscopy or focused ion beam microscopy. Nevertheless, this treatment is impossible for SiN in situ drilled by controlled dielectric breakdown (CDB) since the interest of this method is to obtain a filled nanopore directly after opening. [17] Recently, Karmi et al. reported a simple and fast functionalization based on Levodopamine (L‐dopa‐X where X is an amino acid) to tune the surface charge of SiN and control DNA translocation time. From the chemical point of view, L‐dopa is known to form a Si−O bond between the catechol moieties of the L‐dopa and a silicon substrate. Despite the potential interest of L‐dopa to increase the hydrophilicity of the surface, this small zwitterionic was never considered as an alternative to SiN nanopore functionalization. [18]

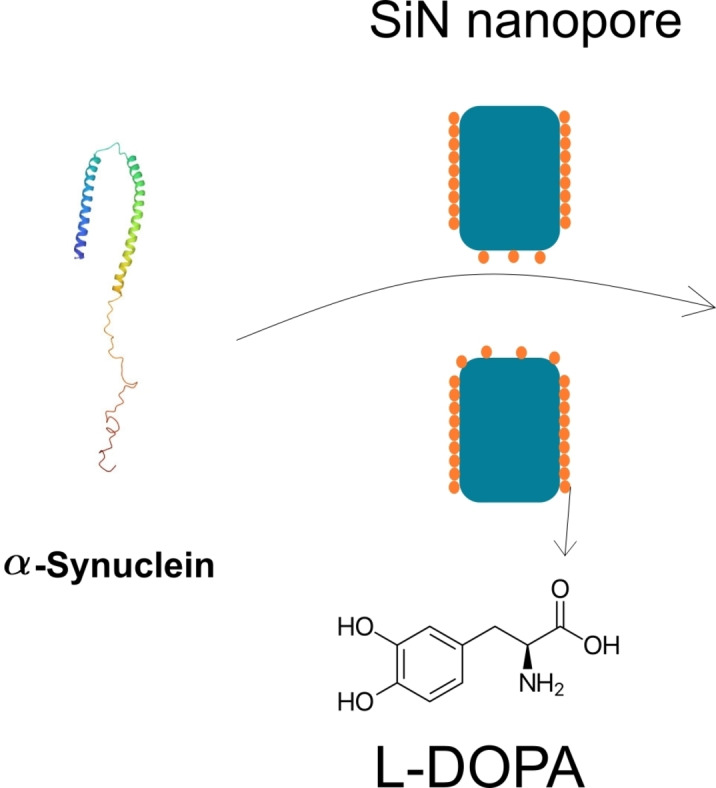

This work aims to investigate the potentiality of the coating with L‐dopa of SiN nanopore to detect the αS and Aβ(42) monomers and oligomers. To this end, we have considered SiN nanopore obtained by CDB and functionalized with L‐dopa. The coating will be characterized on the flat SiN surface but also by investigation of a polymer translocation to evidence the eventual reduction of the nanopore radius. Then, we propose two applications of the L‐dopa coated nanopore. In the first one, the αS wild type (αS‐WT) and A53T variant (αS‐A53T) just dissolved in buffer were analysed in order to discriminate the oligomer populations. In the second one, we want to investigate the size of the oligomer obtained from Aβ(42) Osaka (Aβ(42)‐E22Δ) variant in the presence or absence of Aβ42 wild type (Aβ(42)‐WT) protofibril to emphasize the cross‐seeding mechanisms at the early stage of aggregation.

Results and Discussion

Evidence of L‐dopa functionalization by Heparin translocation

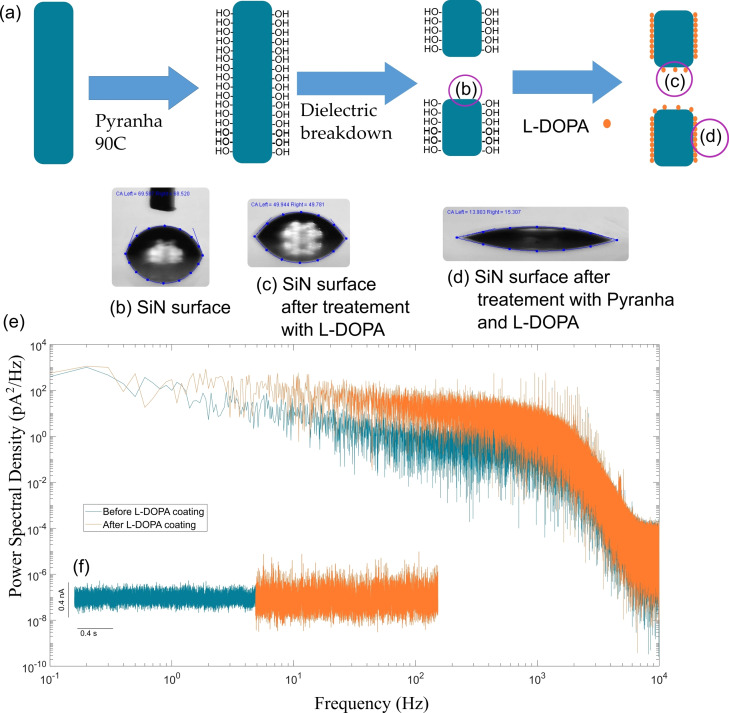

One of major problem in the intrinsically disordered proteins (IDP) (typically α‐synuclein and Aβ) detection using nanopore is the fouling due to their adsorption. This involves coating the SiN to reduce the adsorption. Here, we chose the L‐dopa. The latter is known to create Si−O−C bonds between catechol moieties and silanol present on the surface after activation of SiN. In this work, the SiN nanopores were drilled by CDB, meaning that only the external surface of the chip is activated through oxidative treatment (piranha treatment in this case) (Figure 1). As such, we have to prove that L‐dopa is also able to bind inactivated SiN present at the inner surface of the nanopore. To this end, L‐dopa was grafted on SiN substrate without oxidative treatment. The non‐activated SiN surface exhibits a contact angle about 63° that decreases to 49° after coating with the L‐dopa. By contrast, the L‐dopa coating on an activated SiN induces a contact angle of about 14° (Figure 1). In addition, on the area of the SiN surface where the wetting is total, the addition of L‐DOPA cause it to fall to 0°. These results suggest that the coating of non‐activated SiN is likely not homogeneous. This agrees with previous reports showing that catechol moieties are partially adsorption on SiN surface but does not form a structuration of monolayers.[ 18 , 19 ] On the other hand, assuming that the nanopore drilled by CDB is not activated compared to the external surface of the chip, we could have a dissymmetry between the inner and external nanopore surfaces. When measuring the current trace after the functionalization of L‐DOPA, a significant increase in the of RMS noise was observed (Figure 1). In addition, the power spectrum reveals an increase of 1/f at low frequency. The increase of noise after SiN functionalization was previously reported for several types of grafted organic molecules.[ 16b , 20 ] Even if the exact origin of the 1/f noise is controverted, [21] it could be a signature of the non‐heterogenous surface state due to the partial functionalization of the inner surface wall and/or the difference with the external nanopore surface.

Figure 1.

(a) a scheme showing the opening and functionalization of a SiN nanopore using dielectric breakdown and L‐dopa followed by showing the contact angle taken by a representative SiN surface of the nanopore (b) raw SiN surface, (c) SiN surface after functionalization with L‐dopa (innersurface wall), and (d) SiN surface treated with piranha then functionalized with L‐dopa (external surface). (e) ) is the resulting power spectral diagram obtained from a fast Fourier transformation of the above current traces.and (f) are the current traces obtained before (blue) and after (orange) functionalization of the nanopore with L‐DOPA at 2 M NaCl with PBS at +300 mV obtaining a baseline for this particular nanopore of +9.6 nA.

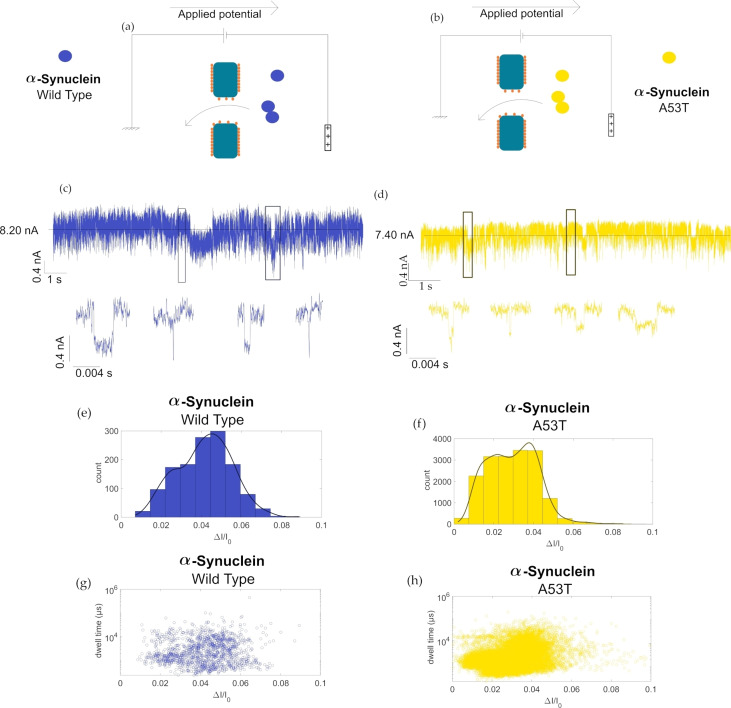

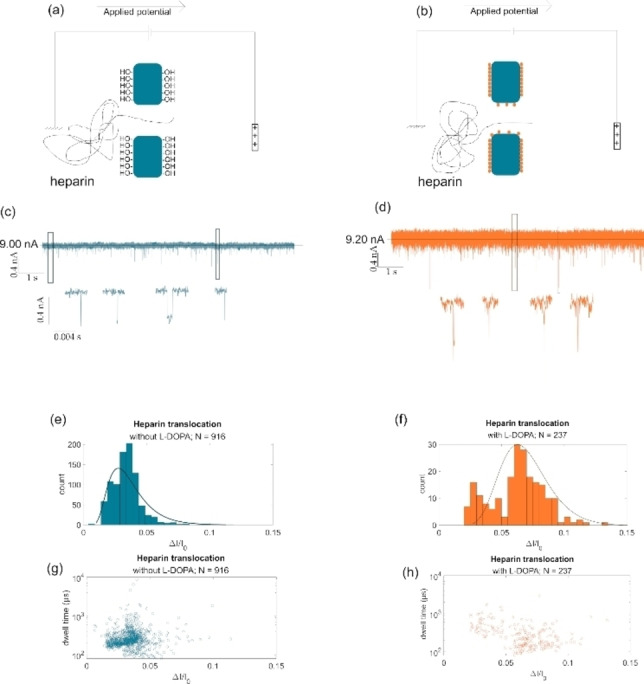

Upon further investigation of the L‐dopa functionalization inside the nanopore, we hypothesize that the L‐dopa coating modifies the nanopore diameter. In order to verify this, we investigate the influence L‐dopa coating on the heparin translocation through a nanopore with a radius about 3 nm (Figure 2). The L‐dopa modifies both the diameter and the surface state of the nanopore making it more hydrophilic. It is also zwitterionic exhibiting negative and one positive charge. Thus, we could also expect that L‐dopa coating will modify the dynamic of heparin translocation. The heparin used in this work has molecular weights ranging from 6,000 to 30,000 Daltons, while most chains in a given sample are in the range of 17,000 to 19,000 Daltons according to the supplier. Its structure was determined in solution by small‐angle neutron scattering. [22] It forms long strands of 7 Å of diameter. It has a flexible helical structure that can form kinks and turns to better bind to proteins. In general, polymers translocate through a nanopore in two distinct conformations: a coil if the nanopore diameter is large enough, or a strand if the nanopore diameter is too small. The hydrodynamic radius of the heparin is estimated from the following equation: [23]

| (1) |

Figure 2.

Sketch of heparin translocation in (a) raw SiN and (b) L‐dopa coated SiN nanopores under +300 mV in 2 M NaCl PBS solution. 10 seconds sample of the current trace for heparin translocation in (c) uncoated and (d) coated SiN nanopore. The full current trace is 5 min long and generally have a baseline of 9 n. Current blockades in the form of histograms for heparin translocation in (e) uncoated (N=916) and (f) coated SiN (N=237) nanopore. Scatter plots showing the translocation events in dwell time (μs) in logarithmic scale versus the current blockade (ΔI/I0) for heparin translocation in (g) uncoated and (h) coated SiN nanopore.

where M is the number of monomer units, the viscosity (0.16.9 dl/g for NaCl 1 M). [24] The obtained Rh is about 3.6 nm that is larger than the nanopore one. Thus, heparin does not translocate as a coil. In Figure 2c and d are reported current trace recorded for a heparin solution in NaCl 2 M PBS 1X pH 7.4 under 300 mV. The current blockades were characterized by their amplitude (noted ) and their dwell time .First of all, the experiments were performed at 2 M NaCl with PBS 1X and thus the counterions driven by the polymer can be neglected in the calculation of polymer volume inside the nanopore. For the nanopore with a radius of 3 nm, the event distribution is monomodal centred to 0.03 (Figure 2e). After L‐dopa coating, the relative current blockade distribution shifts to larger values ( =0.06). Considering that the where Vpol and Vpore are the polymer and pore volume respectively and assuming that Vpol is constant regardless the nanopore surface state, we can estimate the radius of the nanopore coated with L‐dopa's (R dopa):

| (2) |

with R raw is the radius of the nanopore before coating with L‐dopa and is the blockade amplitude as a factor proportion of the volume occupied by the polymer. Using the centre of the distribution obtained for the heparin translocation in the raw and coated nanopore ( and respectively), we found that R dopa is equal to 2.2 nm. The L‐dopa molecule has a length of about 0.9 nm and thus we could expect to find a nanopore diameter equal to about 2.1 nm after coating assuming an optimal grafting of L‐dopa. However, the contact angle suggests a partial functionalization of SiN that is confirmed by the smaller value of the L‐dopa layer than the expected one. For the raw nanopore, the dwell time distribution is centred at 234 μs. It increases to 405 μs after coating with L‐dopa (Figure 2g and h). We estimate the diffusion coefficient (Drp ) of the heparin inside the nanopore using the following equation:

| (3) |

where E is the electric field given by (lp is the nanopore length), Q is the charge of the heparin given by (Mw and mw are the molecular weight for a polymer chain and a monomer respectively). We obtain for =460 nm2/S and 268 nm2/S for the raw and coated nanopore respectively. This means that the L‐dopa coating slows down the heparin translocation. Karmi et al. also reported that the coating of SiN nanopore with dopamine‐His slowed down the DNA translocation. [18] At this stage, the slowdown of heparin translocation and the reduction of the nanopore diameter confirm the presence of L‐dopa inside the nanopore even if the coating is not optimal. We also observe that after coating with L‐dopa, the capture rate of heparin measured under V=300 mV significantly decreases from 4±0.8 to 0.8±0.4. An estimation based on the diffusive approach allows estimating the theoretical capture rate (equation 4.

| (4) |

Where C is the heparin concentration, D the diffusion coefficient estimated from the Rh , A the nanopore surface area and l the nanopore length. The expected value 66.5 hep/s and 32.6 hep/s found without and with L‐dopa coating are larger than the experimental one because due to the energy barrier that the polymer have to overcome to enter inside the nanopore. A roughly the capture rate ratio after and before coating is found to 0.49 using expecting value and 0.05 using experimental value. This show that the decrease of the capture rate is not only due to the reduction of pore diameter but also an increase of the energy barrier of entrance.

Detection of αS monomer and dimer

In the first application, we aim to investigate the oligomerization of αS‐WT and αS‐A53T. In solution, this protein coexists in different oligomer forms. The dimer form has a particular interest since it is likely the first step in the oligomerization of αS to Lewy bodies. It was shown that this dimerization is dependent on the solvent condition (pH) but also the variant. Marmolino et al. reported that the αS‐WT is more prone to dimerization than the A53T variant. [25] To perform such an experiment, fluorescent dyes have to be grafted to the αS which could strongly affect the dynamic of the self‐assembly. The interest is that nanopore sensing is suitable to identify different protein oligomers in a mixture without labelling, making it a good candidate to investigate αS dimerization. To this end, a monomer solution of αS‐WT or αS‐A53T was directly introduced into the fluidic cell to be detected with a SiN of 5 nm diameter coated with L‐dopa. A voltage of 300 mV was applied on the cis side to drive the translocation with electro‐osmotic flow. In Figure 3 are reported current traces showing blockades induced by the presence of αS. Compared to the heparin, the distribution of are bimodal for the αS‐WT centred at 0.023 and 0.045. We observe that the centres of distribution are similar regardless of the applied voltage between 100 mV until 300 mV. First, we estimate the volume occupy by the αS inside the nanopore. To this end, we cannot assume a specific geometry of the αS due to its disordered nature avoiding the use of model taking into account the location of analyte inside the nanopore. [26] Thus, we use the following equation:

| (5) |

Figure 3.

Sketch of αS‐WT (a) and αS‐A53T (b) translocation through an L‐dopa coated SiN nanopores. 10 s of current trace recorded under +300 mV in 2 M NaCl PBS solution for (c) αS‐WT, and (d) αS‐A53T variants. Full current trace is 5 min long and generally have a baseline of 8.25 nA. The average current blockade of these events are then plotted in histogram (e) for the wild type and (f) for αS‐A53T. Scatter plots showing the dwell time in logarithmic scale vs average blockade showing the resulting scatter for (g) the αS‐WT and (h) αS‐A53T of the αS measurements.

where is the volume of the αS located inside the nanopore, Ap and Lp the pore surface and length respectively. We found for the first population of αS‐WT has a volume of 11 nm3. A rough estimation from the PDB structure gives the helix volume around 14 nm3. [27] The αS‐WT can adopt different conformations playing in the excluded volume.

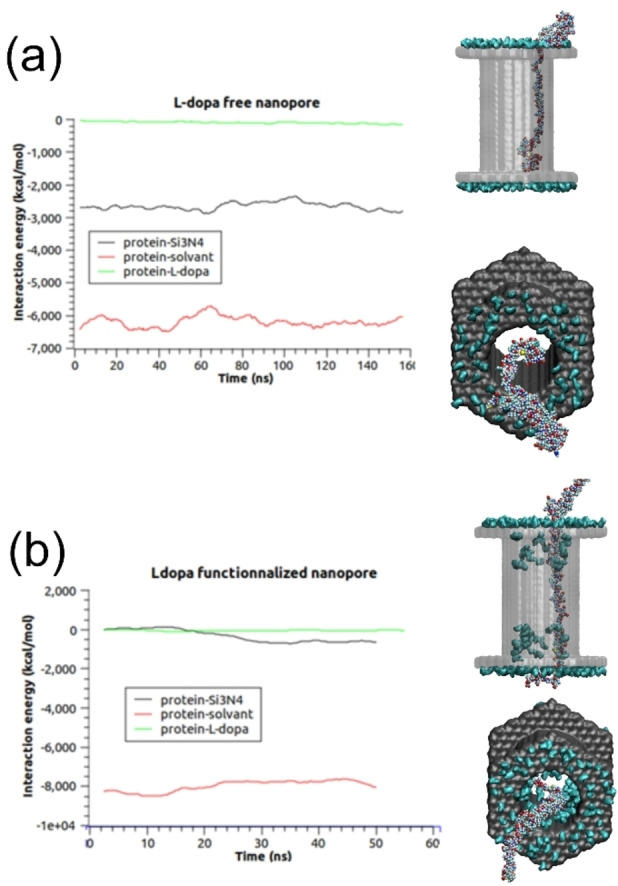

To further investigate the αS‐WT inside the nanopore. MD simulations were performed in different conditions of nanopore functionalization. The αS monomer, relaxed in the buffer before being placed in front of the nanopore, was kept constraint before its release in different positions near the nanopore entry. This latter was either free of L‐dopa molecules or contained a concentration of 30% of L‐dopa molecules in the first and last 10 Å of the nanopore. The surface supporting the nanopore has been tested with multiple L‐dopa coverage ranging from 0 to 50%, and it shows no significant effect on the pore conductance. Hence, all the studied systems for αS translocation used the same 30% grafting rate. In these configurations, the completed systems (αS located near the nanopores) are relaxed under a strong potential difference of 1.5 V for the purpose of accelerating the diffusion process of the monomer. For all the simulations, we observe the same characteristics for the αS monomer. After a rapid insertion of one strand extremity inside the nanopore, this latter starts to interact with the portion of the nanopore wall that is free of L‐dopa. Since the protein‐nanopore interactions is highly attractive, the protein will gradually unfold to maximize its interaction's surface with the nanopore and ultimately results on the protein being almost stuck in place. This behaviour only occurs inside the L‐dopa free pore. Conversely, the protein has less accessible surface to interact with the nanopore when both of the pore's opening areas are functionalized. The external part of the αS still located in the reservoir is also attracted by the external surface of the membrane and tries to avoid L‐dopa grafting sites with which its interaction is very weak (<100 kcal/mol).

To characterize all these observations, we plot in Figure 4 the pair interactions between the αS and its surrounding during its diffusion. As we can observe in the plots of Figure 4a, the monomer is in strong interaction with the surface with an important pair interaction reaching around 2800±100 kcal/mol, which compensates for the loss of energy with the solvent. On the contrary, we can see in Figure 4b that the functionalization of the nanopore can prevent most of the protein‐surface interactions, since these latter reached only −680±50 kcal/mol, thus increasing the translocation speed significantly.

Figure 4.

a) pair interaction of αS with the surface (black), with the solvent, i. e. water+ion (red) and with L‐dopa molecules (green) for the nanopore free of L‐DOPA b) pair interaction of αS with the surface ( black), with the solvent, i. e. water+ion (red) and with L‐dopa molecules (green) for the L‐DOPA functionalized nanopore.

Even though we have observed a slow progression of the monomer inside the nanopore whatever the functionalized systems we have built, we have always stopped the simulations before the complete translocation was obtained. A full translocation would take place on a time scale that would be inaccessible for molecular dynamic simulations. To improve our studies, we have computed the current blockades for each simulation. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Current blockades and monomer velocities obtained through the different simulations at a voltage equal to 1.5 V. The reference current obtained when no monomer is present in the simulations is equal to 23.2 nA on naked pore, and 17.9 nA with functionalized pore.

|

|

L‐dopa 30% naked pore Simulation 1 |

L‐dopa 30% naked pore Simulation 2 |

L‐dopa 30%naked pore Simulation 3 |

L‐dopa 30% functionalized pore |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current Blockades |

14.3% ±0.8% |

14.0% ±0.8% |

14.7% ±0.8% |

3.8% ±0.9% |

We can observe in Table 1 that the functionalized nanopore tends to decrease drastically the current blockade calculated during the simulation of the αS monomer translocation. Here again, this modification is due to the position of the monomer in the nanopore. While strongly in interaction with the full length of the nanopore surface, the monomer did not reach this surface when this latter is covered by the L‐DOPA. As a consequence, only a few parts of the protein are in contact with the nanopore surface and the diffusing systems (ions+monomer) can thus diffuse with fewer constraints. We did not perform simulations with two monomers inside the nanopore but the interaction of the two monomers and the occupied volume by these two molecules will certainly increase the observed current blockades, whatever the functionalization of the surface. The velocities of the strand have been estimated through a very approximate scheme by following the centre of mass of the αS‐WT monomer diffusing in the nanopore (the external part was omitted in our calculations). Through these calculations, we obtained a mean velocity which is around 3 pm/ns for the nude nanopore and 44 pm/ns for the L‐DOPA nanopore. This means that the minimum dwell time for these events should be at least equal to 6 μs (0.3 μs, respectively for the L‐DOPA) to diffuse inside the nanopore. These calculations are performed at 1.4 V. The same calculations performed at 0,3 V showed no displacement of the strand whatever the functionalization of the nanopore. This means that the interaction of the αS ‐WT monomer with the nanopore is so strong that the diffusion is not observable in our MD simulations.

Hence, regarding the simulation, we can hypothesize that the relative amplitude of the first distribution can be assigned to αS ‐WT monomers while the conformation of the monomer could also be at the origin of the blockade changes. Interestingly, the second population of corresponds to a volume roughly twice that of the first one (21 nm3). This suggests that the second population is due to αS‐WT dimers. For αS‐A53T, the distribution of is also bimodal centred for the experiments performed at 300 mV at 0.015 and 0.037. These values are closer than the ones obtained for the αS‐WT. However, the calculation of the volume gives 7 nm2 and 18 nm2 for the monomer and the dimer. This small difference can be assigned to the different conformation adopted by the monomer and the dimer inside the nanopore. Indeed, a previous structural study using atomic force microscopy has shown that the αS monomer takes various conformations from globular to filamentous. [28] Dimers of αS are considered unstable and transient making their in situ characterization difficult. Now, we evaluate the ratio between the monomer and dimer detected by the nanopore. To this end, the histograms were fitted with two Gaussians. The area of each peak was calculated from four experiments. The ratio monomer/dimer obtained for the αS‐WT is about 0.42±0.17 while 1.01±0.23 for αS‐A53T. This does not reflect exactly the concentration ratio between the monomer and the dimer since the capture rate depends on the concentration but also the diffusion coefficient (equation 3). However, our result indicates that the αS‐WT is more prone to form transient dimers than αS‐A53T.

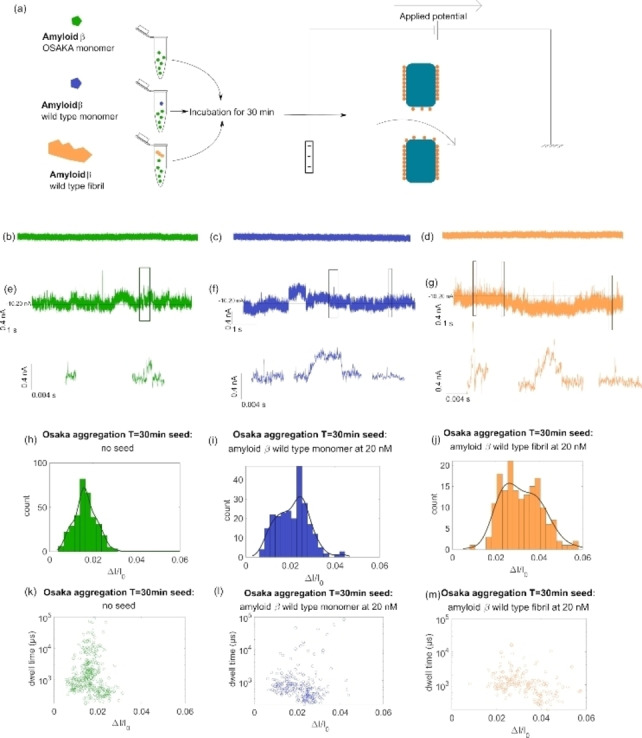

Detection of Aβ(42) bearing the Osaka mutation (Aβ(42)‐ E22Δ): effect of seeding

In the second application, the SiN nanopore coated with L‐dopa was used to investigate the oligomerization of the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ variant in the presence and absence of preformed fibril as seeds of Aβ(42)‐WT (or only monomers as a control). We expect to validate the hypothesis that the preformed seed will promote aggregation at an earlier stage through a seeding mechanism. To this end, the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ variant was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a microplate well at a concentration of 4 μM without and with preformed seeds Aβ42‐WT (40 nM). To detect only the self‐assembled species, we used a nanopore with a diameter of about 10 nm and a voltage of −300 mV was applied on the cis side to drive the proteins with electrophoretic flow. However, the current traces, seen in Figure 5 for only Aβ(42) monomer (t=0 minutes) with or without preformed seeds do not show any current blockade. This indicates that the Aβ(42) monomers are too small to be detected if the incubation time is not sufficient. In addition, the preformed aggregate concentration (seeds) is too low to be detected with a suitable frequency. Conversely, the current trace obtained for the samples withdrawn after 30 minutes of incubation exhibits current blockade events with a significant frequency to confirm the presence of newly formed Aβ(42)‐E22Δ aggregates. In Figure 5, we report the scatter plot and the distribution histogram of the relative current blockade. For the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ seeded with and without Aβ(42)‐WT monomers (20 nM), the distributions of are monomodal and centred at 0.025 and 0.028 respectively. According to equation 4, these values correspond to aggregates with a volume of 38 nm3 and 44 nm3 respectively. Such volumes suggest that only oligomers were detected. We note that the distribution of is more spread (FWHM value) for the sample containing Aβ(42)‐WT monomers at 20 nM. This indicates a more heterogeneous sample. Interestingly, the dwell time distribution is centred on a shorter value for the sample seed with Aβ(42)‐WT. We found the mean velocity is 11.8 μm/s for the sample with Aβ(42)‐E22Δ variant which increases to 19.2 μm/s for the sample with mixed Aβ(42)‐WT monomers. This indicates that even if the volume of the aggregate is quite similar, the number of charges and thus monomer units involved in the aggregates are different. This suggests that the aggregation process of the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ variant is impacted by the presence of Aβ(42)‐WT monomers.

Figure 5.

(a) Sketch of Aβ(42) Osaka aggregate preparation and detection through an L‐dopa coated SiN nanopores Current trace at t=0 min taken at nanopore 10 nm in diameter in 3 M LiCl+4 mM HEPES at −300 mV for Aβ(42)‐E22Δ (b), with Aβ(42)‐WT monomers (c), and with 20 nM Aβ(42)‐WT fibrils (d); current trace at t=30 min taken at nanopore 10 nm in diameter in 3 M LiCl+4 mM HEPES at −300 mV for Aβ(42)‐E22Δ variant (e), with Aβ(42)‐WT monomers (f), and with 20 nM Aβ(42)‐WT fibrils (g) generally the baseline measured was around 10 nA; Histogram showing the registered ΔI/I at T=30 min in 5 min of measurement for Aβ(42)‐E22Δ (N=344) (h), with Aβ(42)‐WT monomer (N=244) (i), and 20 nM Aβ(42)‐WT fibril (N=164) (j); scatter plot showing ΔI/I against Δt (μs) in logarithmic scale for these same events for Aβ(42)‐E22Δ (k), with Aβ(42)‐WT monomer (l), and with 20 nM Aβ(42)‐WT fibril (m).

For the samples seeded with Aβ(42)‐WT fibrils, the distributions of clearly show three populations centred to 0.058, 0.1, and 0.22. The corresponding volumes 91 nm3, 157 nm3, and 346 nm3 are significantly larger than the aggregate obtained without seeds of Aβ42‐WT fibrils. This result can be interpreted by a mechanism of secondary nucleation that allows the production of larger aggregates. [29] This observation is consistent with numerous previous investigations that show the seed mechanism using other methods to detect amyloid such as ThT. [30] Here, we can argue that the acceleration occurs at a very early stage of the aggregation process since, compared to the classical detection methods, nanopore sensing does not require that aggregates adopt a β‐sheet structure. This also confirms the cross‐seeding acceleration process of amyloid with several variants. [31]

Conclusion

In summary, we have functionalized SiN nanopore drilled with dielectric breakdown with L‐dopa. Thus, increasing the hydrophilicity of SiN through a partial functionalization. The investigations of heparin translocation through nanopore before and after coating emphasize a decrease of its diffusion coefficient and larger current blockades. This confirms the functionalization of the inner wall of the nanopore with L‐dopa. Then, the functionalized nanopore was applied to detect the aggregate of two IDPs the αS and the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ at very early stage. In the first application, we investigated the dimerization of αS‐WT and A53T variant. The MD simulation performed on the monomer show that the proteins interact only with the SiN and not with the L‐dopa explaining why the clogging of the nanopore was not observed. The detections of the αS‐WT and A53T variant show that monomer and dimer forms co‐exist. We show that under the experimental conditions, the αS‐WT is more prone to generate dimers than the A53T variant. In a second application, we detect the formation of Aβ(42)‐E22Δ oligomers after a short incubation (seed) with Aβ(42)‐WT monomers and fibrils. We demonstrate that for the Aβ(42)‐E22Δ, with and without Aβ(42)‐WT monomers, the volumes of the newly formed assemblies are similar. However, the Aβ(42)‐WT monomer increase the polymorphism of oligomers. We also show that after incubation with Aβ(42)‐WT fibrils, the aggregates are larger. This emphasizes that a mechanism of second nucleation occurred through a seeding process. With two applications, we demonstrated that SiN nanopore obtained with CDB are suitable to detect IDP aggregates after a simple functionalization with L‐dopa. This work is therefore of great interest since this manufacturing method for these commercial devices is easy and accessible.

Experimental Section

Materials: The L‐dopa (ref. D9628), PBS (ref. P4417), H2SO4 (ref. 07208), H2O2 (ref. 31642), KCl (ref. P3911), HEPES (ref. H3375), KOH (ref. 221473), NaCl (ref. 71380), NaOH (ref. S5881), heparin (ref. H4784), guanidine thiocyanate (ref. 50983) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Aβ peptides wild type and Osaka variant were purchased from ERI Amyloid Laboratory LLC, Oxford, CT,USA. αS A53T human recombinant (ref S1071) were all purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich, and αS, recombinant human (AS‐55555‐1000) monomers were purchased from Anaspec.

Nanopore fabrication: Stressless SiN thin film of 12 nm thickness (Norcada) was used for the fabrication of the nanopore through dielectric breakdown using Northern Nanopore apparatus. First, the SiN microchip was washed in piranha (H2SO4:H202, 3 : 1) at 90 °C for 1 hour. It was then rinsed with Milli‐Q water and dried thoroughly with compressed air. The SiN chip was then placed in the microfluidic cell (Northern Nanopore). 100 μL of Propan‐2‐ol was used to remove all the air from the fluidic system before flushing it with deionized and degassed water. After that, the cell was then filled with a solution of KCl (1 M)/HEPES (8.3 mM) pH 8 (adjusted using KOH (1 M)). To open a nanopore, a potential ramp from 0 to 5 V followed by a slower ramp from 5 to 14 V was applied across the microchip until a pore opening was detected. Once the nanopore was opened, NaCl 1.5 M, HEPES 8.3 mM at pH 8 (adjusted using NaOH 1 M) was introduced for the conditioning step where an applied box voltage from −3 V to 3 V was repeated for several cycles until the nanopore reached the desired diameter of 6 nm+/‐0.6 nm. Afterward, the nanopore was characterized by measuring the conductance using 2 M NaCl with PBS 1X pH 7.4. The nanopore coating with L‐dopa was performed using 10 mg/mL L‐dopa prepared with Mili‐Q water and degassed under vacuum. This solution was then introduced into the fluidic system of the nanopore for 2 h before washing with the MiliQ‐water. The contact angle was done using lab‐made equipment to investigate the effectiveness of using L‐dopa on a silicon nitride surface. To this end, the contact angle was measured using 6 μL deionized water for 10 seconds on silicon nitride surfaces. The experiments were performed on SiN treated or not with piranha before and after L‐dopa coating.

Protein solubilization and purification: αS monomers were solubilized following the protocol of Pujol et al. [32] with slight modifications. Briefly, 500 μl of filtered 1X PBS was added to 100 μg of monomers. Then, the solution was filtered with a 0.45 μm PVDF filter (millipore). The concentration of the monomer was determined by absorbance measurement at 280 nm (JASCO) with the molar extinction coefficient of alpha synuclein equal to 5960 M−1.cm−1. The protein was diluted to the desired concentration, and stored at −30 °C until nanopore experiments. All steps were made on ice to avoid the spontaneous aggregation of the monomer.

Aβ Monomers: To maintain Aβ peptides in the monomeric state the protocol described by Serra‐Batiste et al. was followed. [33] Aβ(1–42) peptides were dissolved in a 6.8 M guanidine thiocyanate solution (Sigma‐Aldrich) to a final concentration of 8.5 mg mL−1. Then, the solution was sonicated for 5 min at 52 °C, and diluted with ultrapure water (4 °C) to reach a final concentration of 5 mg mL−1 of Aβ(1–42) peptides and 4 M of guanidine thiocyanate. The solution was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 6 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and filtered using PVDF filter of 0.45 μm (millipore) and then injected into a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300GL column (GE Healthcare Life Science) previously equilibrated with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Purification was performed with a 0.5 mL/flow to collect the peak attributed to the monomeric Aβ peptide. Finally, Aβ(1–42) peptide concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The aliquots of peptides were flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until the experiments.

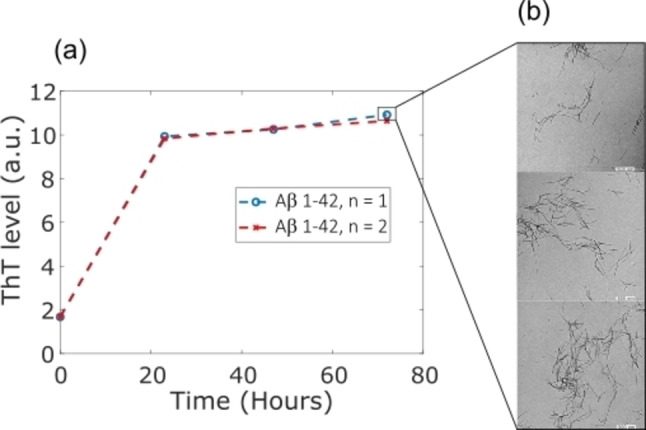

Aβ seed: Aβ(1–42) stock solution was diluted to 30 μM in a 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and left to aggregate in low‐binding Eppendorf tubes for a final volume of 600 μL. These tubes were incubated vertically at 37 °C without agitation. Thioflavine T (ThT) fluorescent molecule was used to monitor the aggregation of the peptide. Briefly, 20 μL aliquots were withdrawn at specific times and mixed with 14 μL of 142 mM GlyNaOH buffer, pH 8.3, and 6 μL of 100 μM of ThT in a 96‐well plate of black polystyrene with a clear bottom coated with a PEG (Thermofisher Scientific). ThT fluorescence of each sample was measured (λex=445 nm and λem=485 nm) in a Fluoroskan Ascent microplate fluorimeter (Thermofisher Scientific). The plateau phase of the aggregation was reached after 2 days of incubation (see Figure 6a). The fibrils were stocked at 4 °C until seeding experiments.

Figure 6.

(a) ThT fluorescence intensity as a function of time showing the kinetics of Aβ aggregation and (b) the resulting fibril imaged by TEM microscopy at 80 kV.

Aβ aggregation: Osaka monomers were incubated into a well of a microplate (black polystyrene with a clear bottom coated with a PEG, Thermofisher Scientific) at a final concentration of 4 μM in presence of 40 nM of Aβ 1–42 aggregates formed previously as seen in Figure 6 or just with 40 nM of monomers. A control condition that contains no seed was also prepared. The final volume of the well was 100 μl containing 6 μM of ThT and the incubation was done at 37 °C without agitation. 10 μl of the well was harvested at different times of aggregation (0 and 30 min) and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stocked at −80 °C until their use for the experiments.

Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) of seeds TEM Samples of Aβ42 aggregates formed after 70 h of incubation at 37 °C were deposited onto Formvar carbon‐coated grids, negatively stained with freshly filtered 2% uranyl acetate, and dried. The TEM images were performed using a JEOL 1400 electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV as seen in Figure 6b.

Resistive pulse experiments: The time‐resolved current measurement under constant voltage (V) was done using patch‐clamp amplifier HEKA EPC800 amplifier coupled with an LIH 8+8 acquisition card. The data acquisition was performed using patchmaster software (HEKA Electronics, Germany). The ionic current was recorded at a sampling rate of 200 kHz and filtered at Bessel filter at 10 kHz. The current blockades were detected using a custom‐made LabVIEW software “Peak Nano Tools”. The raw signals were filtered at 5000 kHz with a Butterworth filter. The threshold for event detection was determined as 6 times the standard deviation after correction of baseline fluctuations by a Savitzky−Golay filter.

Detection of Heparin: Heparin solution (100 mg/mL) was prepared with 2 M NaCl+PBS 1X, pH 7.4. The heparin was placed in the half‐cell connected to the ground.

Detection of αS: αS solution of 25 nM concentration was detected in electrolyte solution 2 M NaCl+PBS 1X, pH 7.4. The αS solution was placed in the half‐cell connected to the working electrode.

Detection of Aβ: Aβ solution of concentration 20 nM was detected in electrolyte solution LiCl 3 M with 4 mM HEPES solution, pH 7.4. the Aβ solution was placed in the half‐cell connected to the working electrode.

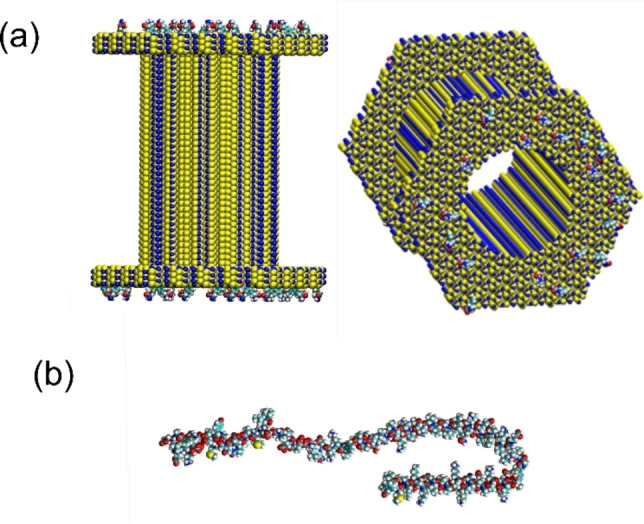

Simulation

Nanopore and protein: To build the silicon nitride nanopore and to converge to a system which is near the experimental conditions, we used the protocol developed by Comer et al.. [34] Briefly, using the Inorganic Builder function of the visual molecular dynamics software (VMD) we created a hexagonal prism presenting the same length as the experimental nanopore (i. e. 12 nm) corresponding to 41 Si3N4 unit cells. In this crystal, we remove centre atoms belonging to a diameter close to the experiment (i. e. 5 nm). The structural and position files are then obtained using the normal protocol. To functionalize the nanopore, L‐dopa molecules were added at different concentrations to the external part of the nanopore, but also in the vicinity of the nanopore exit. The force field of the L‐dopa was obtained using the SWISS PARAM protocol and adapted to take into account the bond created between the Si atom of the nanopore and the C−O function of the L‐dopa molecule. 0, 10, 30 and 50% of L‐dopa coverage were used at the silicon nitride surface while only 0 or 30% of L‐dopa at the entry of the nanopore were imposed (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

a) Schematic representation of the functionalize nanopore of SiN with the L‐dopa molecules. Only the external part of the nanopore was modified chemically here with a concentration of 10%. b) Representation of the αS molecule in the 1XQ8 PDB structure framework. Atoms H, O, C, S, N are respectively coloured in white, red, cyan, green and blue.

To model the αS molecule, the 1XQ8 PDB structure was used. [27] Before mixing the nanopore system with the αS molecule, a complete relaxation in the buffer was performed in order to avoid time during the translocation measurements (See Figure 7b).

Molecular dynamic: The molecular dynamicsimulations were performed in the NAMD 2.13 [35] software environment using the CHARMM36 force field [36] and the TIP3P [37] water model. Note that the protein, when used in the nano‐fluidic modelization, was placed in different starting orientations so that the lowest protein atom had a distance of 5 to 10 Å to the first surface layer of the simulated nanopore. Then the protein was relaxed progressively, before applying an oriented electric field to the system. For all simulations, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [38] for long‐range electrostatics were used to take into account periodic boundary conditions, with a grid spacing of 1.2 Å, and a fourth‐order spline interpolation. 40000 water molecules with a salt concentration of 2.1 mol/L NaCl were included in the system to match experimental conditions. The system net charge was neutralized for correct usage of PME by adding more sodium ions than chloride ions in total. To prevent periodic image interaction, the dimensions of the system was sufficiently large with a 130 Å thick layer of water bulk between periodic images of the membrane. The cutoff for the Van der Waals interactions was chosen as 12 Å. All parameters describing the interaction of the nanopores with the molecules of the system were taken from the procedure previously described [34] which fitted at best the experimental data. After energy minimization, all systems were equilibrated for at least 5 ns at a temperature of 310 K and constant pressure of 1 atm with some protein atoms restrained from preventing translocation before equilibration. Following the equilibration, classical MD simulations were carried out with a time step of 1.0 fs enabled by the SHAKE [39] algorithm to ensure rigid hydrogen atoms. The protein progression is prevented by fixing some of its atoms until the nanopore is fully equilibrated (i. e. constant ions number inside). Then the protein is released from these constraints for an additional duration ranging from 80 to 180 ns. To analyse the simulations, root mean square deviations of the protein were extracted during the production phase to analyse the behaviour of the protein backbone during its translocation. Then, during this phase, pair interactions were extracted from the total duration of the molecular dynamic simulation. These are made of the sum of the Van der Waals and electrostatic contributions between the protein and its neighbourhood (Si3N4 surface/water and ions/L‐dopa).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Acknowledgements

This work was founded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR‐19‐CE42‐0006, NanoOligo). Calculations were performed at the supercomputer regional facility Mesocentre of the University of Franche‐Comté with the assistance of K. Mazouzi. This work was also granted access to the HPC resources of IDRIS, Jean Zay supercomputer, under the allocation 2021 – DARIA0110913048 made by GENCI.

I. Abrao-Nemeir, J. Bentin, N. Meyer, J.-M. Janot, J. Torrent, F. Picaud, S. Balme, Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202200726.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Drndić M., Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 606. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Fologea D., Gershow M., Ledden B., McNabb D. S., Golovchenko J. A., Li J., Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1905–1909; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Li X., Ying Y.-L., Fu X.-X., Wan Y.-J., Long Y.-T., Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 24787–24792; [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Zeng X., Xiang Y., Liu Q., Wang L., Ma Q., Ma W., Zeng D., Yin Y., Wang D., Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1942; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Fologea D., Ledden B., McNabb D. S., Li J., Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 539011–539013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He Y., Tsutsui M., Zhou Y., Miao X.-S., NPG Asia Mater. 2021, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Balme S., Coulon P. E., Lepoitevin M., Charlot B., Yandrapalli N., Favard C., Muriaux D., Bechelany M., Janot J.-M., Langmuir 2016, 32, 8916–8925; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Houghtaling J., Ying C., Eggenberger O. M., Fennouri A., Nandivada S., Acharjee M., Li J., Hall A. R., Mayer M., ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5231–5242; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Hu R., Tong X., Zhao Q., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2020, 9, e2000933; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Luo Y., Wu L., Tu J., Lu Z., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2808; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Sha J., Si W., Xu B., Zhang S., Li K., Lin K., Shi H., Chen Y., Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 13826–13831; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Si W., Aksimentiev A., ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7091–7100; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4g. Xue L., Yamazaki H., Ren R., Wanunu M., Ivanov A. P., Edel J. B., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 931–951; [Google Scholar]

- 4h. Yusko E. C., Bruhn B. R., Eggenberger O. M., Houghtaling J., Rollings R. C., Walsh N. C., Nandivada S., Pindrus M., Hall A. R., Sept D., Li J., Kalonia D. S., Mayer M., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 360–367; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4i. Waduge P., Hu R., Bandarkar P., Yamazaki H., Cressiot B., Zhao Q., Whitford P. C., Wanunu M., ACS Nano 2017, 11, 5706–5716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yusko E. C., Johnson J. M., Majd S., Prangkio P., Rollings R. C., Li J., Yang J., Mayer M., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Plesa C., Kowalczyk S. W., Zinsmeester R., Grosberg A. Y., Rabin Y., Dekker C., Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 658–663; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Pedone D., Firnkes M., Rant U., Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9689–9694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Larkin J., Henley R. Y., Muthukumar M., Rosenstein J. K., Wanunu M., Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 696–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fried J. P., Swett J. L., Nadappuram B. P., Mol J. A., Edel J. B., Ivanov A. P., Yates J. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4974–4992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Li J., Fologea D., Rollings R., Ledden B., Protein Pept. Lett. 2014, 21, 256–265; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Hu R., Rodrigues J. V., Waduge P., Yamazaki H., Cressiot B., Chishti Y., Makowski L., Yu D., Shakhnovich E., Zhao Q., Wanunu M., ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4494–4502; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Tripathi P., Firouzbakht A., Gruebele M., Wanunu M., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 5918–5924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coglitore D., Giamblanco N., Kizalaité A., Coulon P. E., Charlot B., Janot J.-M., Balme S., Langmuir 2018, 34, 8866–8874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Giamblanco N., Coglitore D., Janot J.-M., Coulon P. E., Charlot B., Balme S., Sens. Actuators B 2018, 260, 736–745; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Yusko E. C., Prangkio P., Sept D., Rollings R. C., Li J., Mayer M., ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5909–5919; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Li X., Tong X., Lu W., Yu D., Diao J., Zhao Q., Nanoscale 2019, 11, 6480–6488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Chen G.-F., Xu T.-H., Yan Y., Zhou Y.-R., Jiang Y., Melcher K., Xu H. E., Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1205–1235; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Bengoa-Vergniory N., Roberts R. F., Wade-Martins R., Alegre-Abarrategui J., Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 819–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu R., Diao J., Li J., Tang Z., Li X., Leitz J., Long J., Liu J., Yu D., Zhao Q., Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meyer N., Arroyo N., Baldelli M., Coquart N., Janot J. M., Perrier V., Chinappi M., Picaud F., Torrent J., Balme S., Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meyer N., Arroyo N., Janot J.-M., Lepoitevin M., Stevenson A., Nemeir I. A., Perrier V., Bougard D., Belondrade M., Cot D., Bentin J., Picaud F., Torrent J., Balme S., ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 3733–3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meyer N., Janot J.-M., Torrent J., Balme S., ACS Cent. Sci. 2022, 8, 441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Fujinami Tanimoto I. M., Cressiot B., Jarroux N., Roman J., Patriarche G., Le Pioufle B., Pelta J., Bacri L., Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 183, 113195; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Awasthi S., Sriboonpeng P., Ying C., Houghtaling J., Shorubalko I., Marion S., Davis S. J., Sola L., Chiari M., Radenovic A., Mayer M., Small Methods 2020, 4, 2000177. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Waugh M., Briggs K., Gunn D., Gibeault M., King S., Ingram Q., Jimenez A. M., Berryman S., Lomovtsev D., Andrzejewski L., Tabard-Cossa V., Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 122–143; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Kwok H., Briggs K., Tabard-Cossa V., PLoS One 2014, 9, e92880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karmi A., Sakala G. P., Rotem D., Reches M., Porath D., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 14563–14568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jia Y.-F., Gao C.-Y., He J., Feng D.-F., Xing K.-L., Wu M., Liu Y., Cai W.-S., Feng X.-Z., Analyst 2012, 137, 3806–3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roman J., Jarroux N., Patriarche G., Français O., Pelta J., Le Pioufle B., Bacri L., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41634–41640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liang S., Xiang F., Tang Z., Nouri R., He X., Dong M., Guan W., Nanotechnol. Precision Engin. 2020, 3, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rubinson K. A., Chen Y., Cress B. F., Zhang F., Linhardt R. J., Biopolymers 2016, 105, 905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bertini S., Bisio A., Torri G., Bensi D., Terbojevich M., Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo X., Condra M., Kimura K., Berth G., Dautzenberg H., Dubin P. L., Anal. Biochem. 2003, 312, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marmolino D., Foerch P., Atienzar F. A., Staelens L., Michel A., Scheller D., Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 71, 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qin Z., Zhe J., Wang G.-X., Meas. Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 45804. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ulmer T. S., Bax A., Cole N. B., Nussbaum R. L., J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 9595–9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y., Hashemi M., Lv Z., Williams B., Popov K. I., Dokholyan N. V., Lyubchenko Y. L., J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 123322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zimmermann M. R., Bera S. C., Meisl G., Dasadhikari S., Ghosh S., Linse S., Garai K., Knowles T. P. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16621–16629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scheidt T., Łapińska U., Kumita J. R., Whiten D. R., Klenerman D., Wilson M. R., Cohen S. I. A., Linse S., Vendruscolo M., Dobson C. M., Knowles T. P. J., Arosio P., Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lucas M. J., Pan H. S., Verbeke E. J., Partipilo G., Helfman E. C., Kann L., Keitz B. K., Taylor D. W., Webb L. J., J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 2217–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pujols J., Peña-Díaz S., Conde-Giménez M., Pinheiro F., Navarro S., Sancho J., Ventura S., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Serra-Batiste M., Ninot-Pedrosa M., Bayoumi M., Gairí M., Maglia G., Carulla N., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10866–10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Comer J. R., Wells D. B., Aksimentiev A., Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 749, 317–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K., J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. MacKerell A. D., Bashford D., Bellott M., Dunbrack R. L., Evanseck J. D., Field M. J., Fischer S., Gao J., Guo H., Ha S., Joseph-McCarthy D., Kuchnir L., Kuczera K., Lau F. T., Mattos C., Michnick S., Ngo T., Nguyen D. T., Prodhom B., Reiher W. E., Roux B., Schlenkrich M., Smith J. C., Stote R., Straub J., Watanabe M., Wiórkiewicz-Kuczera J., Yin D., Karplus M., J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L., J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Darden T., York D., Pedersen L., J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ryckaert J.-P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H. J. C., J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.