Abstract

Introduction:

Knee dislocations are an uncommon complication following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). There are many causes of TKA dislocation; however, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is one uncommon neurologic condition that increases the risk of TKA dislocation.

Case Report:

A 71-year-old male with presented to a local community hospital with knee pain due to advanced osteoarthritis of the knee and subsequently underwent an uncomplicated TKA with a cruciate retaining prosthesis. He eventually returned to the hospital due to infection, medical instability, chronic knee instability, and posterior tibiofemoral dislocation. A revision process was required. Throughout the course of management, the patient had altered mental status and was admitted to the intensive care unit. The first procedure involved removing the cruciate retaining prosthesis and replacing it with a static cement antibiotic spacer. This prosthesis was eventually dislocated through the tibia and a second procedure requiring the placement of an intercalary fusion was needed. The patient has not followed up after the hospital admission.

Conclusion:

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome is an uncommon condition that affects alcoholics and complicates treatment with joint replacement surgery. Patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome provide a unique set of challenges that may require multiple surgeries and varying prostheses. Chronic posterior tibiofemoral dislocation is one specific complication that may affect the management of these patients. As orthopedic surgeons, it is important to consider alcohol use disorder and Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome when treating patients with total joint replacement.

Keywords: Wernicke-Korsakoff, intercalary fusion, total knee arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty dislocation, tibiofemoral dislocation

Learning Point of the Article:

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is an overlooked alcohol related neurological syndrome that affects the treatment and outcome of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty and may necessitate alternative management.

Introduction

Knee dislocations are an uncommon complication following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [1]. Newer designs incorporating a higher tibial polyethylene post and reduced anterior translations have lowered the frequency of cruciate retaining TKA to about 15–5% [2, 3].

Knee dislocation after TKA can be related to a flexion-extension mismatch, component malposition, extensor mechanism dysfunction, remnant of the cement, and valgus deformity [4]. Other less common causes of dislocation include late PCL and polyethylene failure, and neurologic disease [1]. Two mechanisms for dislocation have been suggested. The first is a rotary dislocation that occurs in patients with a valgus deformity who then underwent an extensive lateral release injuring the popliteus tendon and the lateral collateral ligament. The second mechanism occurs with strong contraction of the hamstring with a flexed knee causing the femoral component to displace anterior to the polyethylene insert [5, 6]. Polyethylene damage and ligamentous insufficiency can also cause tibiofemoral dislocation [7].

Although these mechanical factors increase the risk of knee dislocations, neurologic conditions present a unique set of challenges for surgeons. These patients can suffer from contractures, weakness, spasticity, and ligament instability which makes treatment more difficult [8]. A systematic review of TKA in neurologic disorders assessed the outcomes of TKA in patients with neurologic disorders and included common TKA complicating neurologic disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, polymyositis, Charcot joint, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and stroke. They found that these patients are at a significantly increased risk for complications, including knee dislocation [8]. Although uncommon, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is another neurological condition that may increase the risk of tibiofemoral dislocation following TKA.

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is a condition caused by a deficiency of Vitamin B1 (thiamine). This disorder begins with Wernicke encephalopathy, which causes damage to the thalamus and hypothalamus. This is followed by Korsakoff psychosis, which causes irreversible impairment to the brain’s memory centers. Symptoms include confusion, loss of mental acuity, ataxia, vision changes, inability to form new memories, memory loss, confabulation, disorientations, emotional changes, and hallucinations [9]. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common cause of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome as it affects many of the body’s neurotransmitters. Acute and chronic neurologic effects of alcohol consumption include alcohol related seizures, myopathy, delirium tremens, peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, and cognitive deficits. Neuropathy can slowly progress to muscular weakness, loss of sensation, and reflexes leading to neuromuscular disorders such as foot drop [10, 11]. These clinical features can complicate total joint replacement surgery in high-risk patients.

Alcohol abuse and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome can predispose patients to tibiofemoral dislocation following TKA and increases the complication risk. At present, there is no literature discussing the association of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and dislocation following TKA. The purpose of this case report is to discuss the history, timeline, and orthopedic management of a patient with recurrent tibiofemoral femoral dislocations following TKA as a result of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and AUD.

Case Report

A 71-year-old male with a medical history of osteoarthritis, right total hip arthroplasty, hypercholesterolemia, disorder of thyroid gland, steatosis of liver, lung nodules, calcification of coronary artery, and benign prostatic hyperplasia was admitted to Larkin Community Hospital in South Miami after a routine cruciate retaining TKA due to osteoarthritis (Figs. 1a, b and 2). Before surgery, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented (AAO) times 3 (AAO × 3). He showed a full understanding of the procedure and treatment options. He admitted to alcohol abuse but quit 1 year ago. He was cleared by his primary care and cardiology physicians. He had the following medical problems: Hypercholesterolemia, benign prostatic hyperplasia, disorder of the thyroid gland, steatosis of the liver, nodule of the lung, and calcification of the coronary artery. Muscle strength was 5/5, pulses were 2+ in both lower extremities and body mass index was 30.1 kg/m2. The patient was discharged the following day after an unremarkable hospital course. Post-operative X-rays are shown below (Fig. 3a , b).

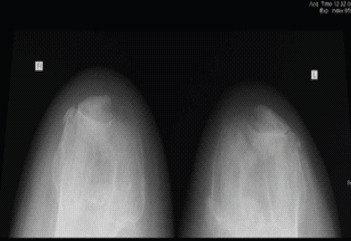

Figure 1.

(a and b: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of bilateral knees.

Figure 2.

Sunrise view radiographs of both knees.

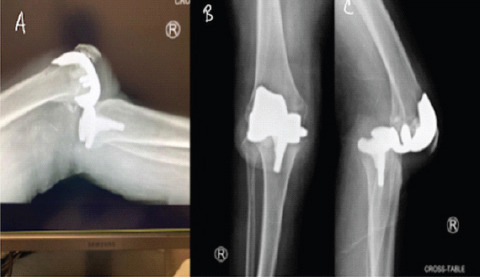

Figure 3.

(a and b) Anteroposterior and lateral radiographic views of the right knee.

The patient returned to the emergency department (ED) 7 weeks later with right knee pain. On examination, he was found to be awake, AAO × 1 to person only. During this time, the patient had a respiratory rate of 11 bpm, blood pressure of 131/89, and oxygen saturation of 97%. There was no prior history of altered mentation or memory deficits. There was obvious deformity of the right knee with tenting of the skin and signs of prosthetic joint infection (draining sinus with elevated CRP and ESR) as well as a skin ulcer on the foot (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Physical inspection of the patient’s right knee upon arrival to the emergency room.

According to a history obtained by his proxy, the patient was doing well until 2 weeks prior (approximately 5 weeks postoperatively) when he was found by his physical therapist lying on the floor of his home in his own urine with an apparent right knee dislocation. He was taken to an outside facility that preformed a closed reduction. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility after this encounter. The patient was then transferred to the Larkin Community Hospital ED from the rehabilitation facility due to another apparent knee dislocation. The dislocation was reduced but continued to dislocate on extension. Once the knee reduced in extension a well-padded knee immobilizer was put on to prevent complications and recurrent dislocation. He was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was started on appropriate antibiotics and scheduled for revision surgery after medical optimization. Radiographs obtained during time of admission are shown in Fig. 5ab and c. The patient also had a previous THA which appeared in appropriate alignment (Fig. 6). Further imaging of the right lower extremity was unremarkable.

Figure 5.

(a-c) Anteroposterior, lateral, and cross table lateral radiographic views of the right knee demonstrating a posterior tibiofemoral dislocation.

Figure 6.

A previous total right hip arthroplasty that shows normal alignment and no signs of loosening or complication.

The patient was later taken to the operating room to undergo a Stage 1 right TKA revision with placement of a static cement antibiotic spacer (Fig. 7a,b). The femoral component was removed in the usual fashion. The tibial component was completely loosened. Attached to the tibial component were parts of bone, which may indicate trauma as the etiology of the patient’s dislocation. Furthermore, a significant amount of scar tissue had formed on the anterior aspect of the patella and the patellar tendon. Dissection and histopathology also demonstrated evidence of infection. Knee cultures grew Enterobacter Cloacae which was sensitive to levofloxacin. The patient was then taken to the operating room to remove his current prosthesis and add an antibiotic cement spacer (Fig. 7a, b). He was eventually discharged AAO × 1 to a × DCF with 6 weeks of medication.

Figure 7.

(a and b) Oblique and lateral radiographic view of the right knee demonstrating an intact antibiotic cement spacer with no signs of fracture or displacement.

Six days after discharge, the patient returned with an inflamed knee (AAO × 0) and some evidence of hematoma formation but no infection. Almost no fluid was aspirated and there was no pus. The patient remained AAO X1 in the ICU with multiple medical problems including pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, anemia, encephalopathy, and atrial fibrillation. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth during that time.

During the post-surgical course, he was confused, disorganized in thought, restless, delusional, aggressive, and tangential in his responses with a blunted affect. According to a psychiatric consult, the patient had delayed responses and processing. He had thought blocking and was unable to recall events. It was evident that the patient had an extensive history of alcohol use. According to his son, the patient was a recovering alcoholic who may have relapsed past year when he found several empty beer cans in the patient’s car before this admission. The son also stated the patient had a history of bipolar II disorder. He had never been admitted to any psychiatric facility and had not been on medication for his bipolar disorder in several years.

Overtime the patient became aggressive and disoriented. There was increased pain in the right knee, tenting of skin, soiled dressing, and an inflamed incision. New radiographs showed a dislodged antibiotic spacer perforating through the distal aspect of the tibia (Fig. 8a and b). Due to the subsequent dislocation, an intercalary fusion was indicated (Fig. 9a and b). Surgical and histopathologic examination at this time continued to show evidence of infection. Blood cultures during this time were negative. He was admitted to the ICU and suffered from nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal polyp hemorrhage. Other medical problems included acute blood loss anemia, hypokalemia, pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, lung nodule, and shock of undetermined significance. The patient had normal B12 levels, negative rapid plasma reagent test, and normal ammonia levels. He was given many medications and treatments throughout his hospital course including apixaban, loop diuretics, epinephrine, and packing, lorazepam for seizure prophylaxis, aspirin and atorvastatin, and Vitamin K. The patient’s mental status improved to AAO × 3 overtime through treatment of underlying medical conditions. MRI was recommended but never performed. A new 6-week course of antibiotics was started. He was eventually cleared medically for discharge. There are no new follow-ups following this hospital admission.

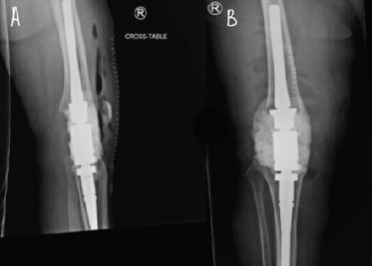

Figure 8.

(a and b) Oblique and lateral radiographic view of the right knee demonstrating a anteriorly displaced antibiotic cement spacer.

Figure 9.

(a and b) Anteroposterior and lateral radiographic views of the right demonstrating an intercalary fusion prosthesis.

Discussion

This patient returned with a history of chronic posterior tibiofemoral dislocation, which resulted in two revision procedures ending in an infection and eventual intercalary fusion. His mentation was altered throughout his return. The patient initially presented with a periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) during his first visit to the ED. Infection persisted and was managed by infectious disease; however, there was no evidence of PJI of the knee or sepsis as blood cultures, urine cultures, and aspirates were negative. His normal pressure hydrocephalus was likely not the cause of the patient’s altered mentation. A mental health assessment discovered a history of AUD and bipolar II disorder for the patient. Nevertheless, psychiatry attributed this patient’s delirium to either infection, fall, recent ICU admission, or chronic alcohol use.

Although there are no specific laboratory tests to diagnose Wernicke-Korsakoff

syndrome, many patients have altered electrolyte abnormalities, magnesium levels, coagulation studies, arterial blood gas, and liver enzymes with possible lactic acidosis and thiamine deficiency. MRI may show areas of symmetrical increased T2/FLAIR signals [12, 13]. This patient’s metabolic derangements could be due to a combination of factors including AUD, infection, pneumonia, or other simultaneously occurring medical complications. However, his history and course are consistent with AUD and, in turn, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome as the impetus of his deterioration. This patient was found on the floor in his own urine and feces during the first episode of dislocation suggesting incontinence and ataxia, two signs consistent with Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome [13, 14]. His delirium suggests possible delirium tremens, which involves global confusion, sympathetic overdrive, and cardiovascular collapse, a severe complication of alcohol withdrawal [15]. This patient also had chronic persistent amnestic signs, delusions, and confabulations suggesting Korsakoff psychosis [16]. Unfortunately, MRI was not ordered during his medical course and, therefore, radiologic evidence is inconclusive. Blood cultures, urine cultures, and knee aspirate were also negative indicating that sepsis may not be the etiology of his delirium. Finally, this patient suffered from nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal polyps, a sign of alcohol related liver damage. Although our patient’s did not display ophthalmoplegia, common in Wernicke Encephalopathy, <1/3 of patients have the complete triad of ocular dysfunction, altered mental status, and ocular dysfunction [17].

Orthopedic surgeons are challenged with the difficulties managing patient comorbidities including neurologic conditions such as Wernicke-Korsak off syndrome, which is easily overlooked and missed due to their low prevalence (1–3%) [13]. A detailed history assessing alcohol abuse and psychiatric history can help identify patients at risk for developing any of the above-mentioned alcohol-related complications. Knowledge of such predisposing factors may alter a surgeon’s typical perioperative plan such as inpatient admission after surgery or even delay in surgery until the patient is medically optimized. To further minimize the risk of dislocation, orthopedic surgeons may also elect to alter the prosthesis type in high-risk patients like the one mentioned in this case report.

Ultimately, management of the tibiofemoral dislocation depends on the proper identification of the etiology of the instability. Patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff may have specific manifestations that make them prone to tibiofemoral dislocation. For example, these patients may experience ataxia and ophthalmoplegia, which increases their risk of falls. This may require more stability in their TKA with a constrained, hinged, or posterior stabilized prosthesis. Furthermore, early detection and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome with glucose and thiamine may help shorten the duration of the condition and prevent permanent damage [9, 12, 13].

Conclusion

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome is a neurologic condition that may affect the stability and longevity of CR TKA. These patients suffer from problems that predispose them to TKA dislocations like ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, delirium, or seizures. Increasing awareness of this syndrome and including it with the other TKA complicating neurologic diseases is imperative, as many patients with Wernicke-Karsakoff syndrome are underdiagnosed and provide a unique set of complications for orthopedic surgeons.

Clinical Message.

Wernicke-Korsokoff syndrome is a neurological condition that can affect the stability and longevity of the total joint arthroplasty prostheses, specifically by increasing the risk of chronic tibiofemoral dislocations. Orthopedic surgeons should approach these patients differently to prevent surgical complications.

Declaration of patientconsent: The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given the consent for his/ her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his/ her names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflict of Interest:Nil Source of support:None

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Villanueva M, Rios-Luna A, Pereiro J, Fahandez-Saddi H, Pérez-Caballer A. Dislocation following total knee arthroplasty:A report of six cases. Indian J Orthop. 2010;44:438–43. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.69318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombardi AV, Jr, Mallory TH, Vaughn BK, Krugel R, Honkala TK, Sorscher M, et al. Dislocation following primary posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8:633–9. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(93)90012-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hossain S, Ayeko C, Anwar M, Elsworth CF, McGee H. Dislocation of Insall-Burstein II modified total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:233–5. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi H, Akamatsu Y, Taki N, Ota H, Mitsugi N, Saito T. Spontaneous dislocation of a mobile-bearing polyethylene insert after posterior-stabilized rotating platform total knee arthroplasty:A case report. Knee. 2011;18:496–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao V, Targett JP. Instability after total knee replacement with a mobile-bearing prosthesis in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:731–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laskin RS, Maruyama Y, Villaneuva M, Bourne R. Deep-dish congruent tibial component use in total knee arthroplasty:A randomized prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;380:36–44. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jethanandani RG, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI, Goodman SB, Amanatullah DF. Tibiofemoral dislocation after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2282–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomeroy E, Fenelon C, Murphy EP, Staunton PF, Rowan FE, Cleary MS. A systematic review of total knee arthroplasty in neurologic conditions:Survivorship, complications, and surgical considerations. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:3383–92. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelat AM, Zieve D. Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome:Medlineplus Medical Encyclopedia. MedlinePlus. 2022. [[Last accessed on 2020 Feb 4]]. Available from: https://www. Medlineplus. Gov/Ency/Article/000771 Htm .

- 10.Hammoud N, Jimenez-Shahed J. Chronic neurologic effects of alcohol. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:141–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinsella LJ. Vitamin deficiencies and other nutritional disorders of the nervous system In:Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience. Netherlands: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 1455–67. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salen PN. Wernicke Encephalopathy Workup:Approach Considerations, Biomarkers, Serum Electrolyte Levels;2021. [[Last accessed on 2022 Apr 24]]. Available from: https://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/794583-workup#c2 .

- 13.Vasan S, Kumar A. Wernicke Encephalopathy. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verra WC, van den Boom LG, Jacobs W, Clement DJ, Wymenga AA, Nelissen RG. Retention versus sacrifice of the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee arthroplasty for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD004803. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004803.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman A, Paul M. Delirium Tremens. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charness ME. Overview of the Chronic Neurologic Complications of Alcohol. United States: UpToDate; 2022. [[Last accessed on 2022 Apr 24]]. Available from: https://www. Uptodate. Com/Contents/Overview-Of-The-Chronic-Neurologic-Complications-Of-Alcohol?Search=Korsakoff+Syndrome+Encephalopathy&Amp;Source=Search_Result&Amp;Selectedtitle=1~150&Amp;Usage_Type=Default&Amp;Display_Rank=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isen DR, Kline LB. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of wernicke encephalopathy. Eye Brain. 2020;12:49–60. doi: 10.2147/EB.S234078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]