Abstract

Purpose:

Capture-recapture methods estimate the size of hidden populations by leveraging the proportion of overlap of the population on independent lists. Log-linear modeling relaxes the assumption of list independence, but best model selection criteria remain uncertain. Incorrect model selection can deliver incorrect and even implausible size estimates.

Methods:

We used simulations to model when capture-recapture methods deliver biased or unbiased estimates and compare model selection criteria. Simulations included five scenarios for list dependence among three incomplete lists of population of interest. We compared metrics of log-linear model selection, accuracy, and precision. We also compared log-linear model performance to the decomposable graph approach (a Bayesian model average), the sparse multiple systems estimation (SparseMSE) approach that accounts for zero or low cell counts, and the Sample Coverage approach.

Results:

Log-linear models selected by Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) calculated accurate population size estimates in all scenarios except for those with sparse or zero cell counts. In these scenarios, the decomposable graph and the Sample Coverage models produced more accurate size estimates.

Conclusion:

Conventional capture-recapture model selection fails with sparse cell counts. This naïve approach to model selection should be replaced with the implementation of multiple different models in order triangulate the truth in real-world applications.

Keywords: Capture-Recapture, Population Size Estimation, Simulation Study

INTRODUCTION

In public health, valid estimates of population sizes are needed to understand disease burden, distribution, and the impact of control efforts.1 Many populations of special interest lack a census or representative sample. Numerous methods have been developed to leverage incomplete information from biased samples to estimate the total size of target populations.2 Capture-recapture (CRC) is a well established population size estimation (PSE) method that estimates the population size based on the degree of overlap between two or more incomplete lists (samples) of the population.3,4 Intuitively, with a high level of overlap (i.e., the same individuals seen on multiple lists), then most individuals in the population are likely already observed on the combined lists. With little overlap across lists, the size of the population is likely much larger than what has been observed. CRC has broad applications for estimating unobserved populations, including disease and injury surveillance,5–10 and is commonly used to estimate the size of key populations for HIV surveillance.11–14 The major challenges of surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the importance of flexible feasible tools to monitor the size of hidden populations.

A key assumption for CRC estimation is that lists are statistically independent from one another. Presence or absence of an individual on one list does not affect the probability that individual is included on another list. This theoretical assumption is difficult to meet in practice, but methodologic innovations offer opportunities to estimate population size even when there is dependence between lists.

To account for potential bias due to list dependencies, at least three lists must be included and log-linear regression models (LLMs) can be fit to the data. LLM is a common approach for the analysis of cross-classified categorical data.15 In CRC estimation with LLMs, data are structured with indicator variables for presence on each list (L1, L2, or L3), and a dependent variable representing the count of individuals with that combination of list inclusion (Y). These models can include up to 2k−1 parameters (where k is the number of lists), with interaction terms between list indicators to control list dependency. An example of a three-list model with no list dependency is log(Y) = β0 + β1L1 + β2L2 + β3L3. β0 is the log expected count for the number of people not observed on any list. β1 is the difference of the log of the number of people uniquely observed on L1 and the log of the number of people not observed on any list (β1 can also be interpreted as the log of the ratio of the number of people on L1 alone to the number of people not on any list). β2 and β3 offer the same contrast for L2 and L3, respectively. The row in which L1, L2, and L3 are 0 is unobserved in the data. The intercept β0 is identified because of the constraints implied by the lack of interaction terms in the model. For example, the number of people on both L1 and L2 but not on L3 is predicted by β0+β1+β2. This model can be modified to include combinations of possible two-way interactions (e.g., L1*L2) or a three-way interaction (L1*L2*L3), but at least one of these interaction terms must be omitted to identify β0. The k-way interaction is often not modeled because of the hierarchy principle, which instructs that all lower level interactions must first be modeled before a k-way interaction is included.

Conventionally, the model with the lowest information criterion (e.g. Akaike Information Criterion [AIC]), a data-based statistic reflecting the fit of the statistical model to the observed data adjusted for the complexity of the model, is selected as the best estimate. This model selection approach is referred to as naïve CRC. Alternatively, as recommended by Cormack et al., researchers may select the fully saturated model (i.e., the model with all possible pairwise interaction terms) as the best estimate.16 In contrast, Wesson et al applied CRC models to evaluate the completeness of the HIV surveillance system in Alameda County, CA and found that as the models became more saturated population size estimates of people living with HIV became more biased, less precise, and ultimately implausible (Table 1).17

Table 1.

Population Size Estimates of the diagnosed PLWH population under Alameda County, CA, public health jurisdiction from the best fitting Identifiable Models, 2013

| Model | 95% CI | AIC | df* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 5,943 | 5,867 – 6,023 | 974.5 | 10 |

| Base + L1*L3 | 5,891 | 5,820 – 5,965 | 715.1 | 9 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L2*L3 | 5,846 | 5,780 – 5,915 | 485.8 | 8 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L2*L3 + L3*L4 | 5,684 | 5,625 – 5,747 | 417.7 | 7 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L1*L4 + L2*L3 + L2*L4 | 6,198 | 6,069 – 6,338 | 391.2 | 6 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L1*L4 + L2*L3 + L2*L4 + L3*L4 | 7,543 | 6,270 – 11,026 | 387.4 | 5 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L1*L4 + L3*L4 + L1*L3*L4 + L2*L3 + L2*L4 | 10,234 | 6,739 – 30,225 | 382.75 | 4 |

| Base + L1*L3 + L1*L4 + L3*L4 + L1*L3*L4 + L2*L3 + L2*L4 + L3*L4 + L2*L3*L4 | 1.113e10 | 8,062 – 3.339e10 | 379.9 | 3 |

Degrees of freedom remaining. Selected models are the best-fitting model (lowest AIC) within strata of models with equivalent degrees of freedom remaining (e.g., among the log-linear models with nine degrees of freedom remaining, models where only one interaction term is included along with the Base parameters, the model with the L1*L3 interaction had the lowest AIC).

Base= main terms corresponding to each individual list (not including list interactions); L1= List 1; L2= List 2; L3= List 3; L4= List 4

= estimated population size

Other researchers have advised against naïve CRC, as multiple LLMs can fit the data equally well yet generate very different size estimates.18 The non-identifiability of PSE through CRC, as well as the weak identifiability through various constraints, has been well-described in other disciplines.19,20 While these fundamental concerns are not wholly unknown to epidemiologists, naïve CRC remains common, potentially introducing unreliable denominators to characterize populations and disease surveillance. Therefore, we conducted a simulation study to test the robustness and limits of CRC estimators in different data-generating systems and inform the more critical application of this tool among epidemiologists.

METHODS

Simulation Study

We simulated a population of 1000 individuals and three incomplete lists generated by randomly sampling from this source population. Four scenarios were specified, varying the probabilities that individuals were sampled and the degree of list dependence, while maintaining the marginal probabilities with which each list sampled the population. A fifth scenario was simulated that varied the marginal probabilities to test the performance of estimators when sampling probabilities are small.

Scenario 1 depicts perfect independence: L1 randomly sampled 20% of the population, L2 randomly sampled 25% of the population, and L3 randomly sampled 30% of the population.

Scenario 2 depicts direct positive dependency between L1 and L3. L1 randomly sampled 20% of the population, L2 randomly sampled 25%, and, if an individual was not included on L1, L3 randomly sampled 24%. However, if an individual was included on L1 their probability of inclusion on L3 increased by 30 percentage points (PP). This scenario could occur in practice if a medical center had a policy of referring their patients to a specialty clinic.

Scenario 3 includes a third-order interaction. L1 and L2 randomly sampled 20% and 25% of the population, respectively. The probability of inclusion on L3 is 25% if not on L1 or L2. Inclusion on L3 increases by 45 PP if included on L1, and increases by 20 PP if included on both L1 and L2. In this case, L3 could represent a surveillance system that receives reports of cases from multiple sources – presence on one source substantially increases inclusion on the surveillance list and presence on multiple other sources nearly guarantees inclusion.

Scenario 4 depicts dependency between two lists due to a shared variable. Individuals coded as “0” for this binary third variable, U (e.g., males, if the third variable is sex) have 0% chance of being sampled by L1 or L2 (e.g., being on OB/Gyn clinic patient lists), violating the capture homogeneity assumption (i.e., for each sample, each individual has the same probability of being included in the sample). U has probability of 50%. L1 samples 40% of the population when U=1. L2 samples 50% of the population when U=1. L3 randomly samples the entire target population, irrespective of U.

Scenario 5 also depicts dependency between two lists due to a shared third variable and tests model performance when sampling probabilities are small. The probability of being observed on L1 or L2 increases for people coded as “1” for the binary third variable, U (e.g., females, if the third variable is sex). U has a probability of 50%. The probability of being observed on L1 when U=0 is 2% (and is increased by 20 PP if U=1). The probability of being observed on L2 when U=0 is 3% (and is increased by 20 PP if U=1). The probability of being observed on L3 is 6%, irrespective of U.

Each scenario was simulated 500 times. We used four modeling frameworks for estimation. First, the R package Rcapture estimated the population size using conventional LLMs.21 Each scenario built all possible combinations of interaction terms, except the 3-way interaction term. Second, the R package DGA estimated the population size using the decomposable graph approach (DGA).22 DGA uses a Bayesian approach to average the posterior probability distributions from all possible models of list dependencies, weighted by the marginal likelihood of each model.17,22,23 DGA does not involve model selection because information from all models is used to calculate a single posterior probability distribution, from which the mean is calculated as the point estimate, bounded by a 95% credible interval. The third approach was the R package SparseMSE, a recently developed model from the human trafficking literature to account for small or no overlap between lists.24,25 In conventional LLMs, the statistical model will search the parameter space for the value that maximizes the likelihood of the sparse or zero cell count. The model will iterate towards negative infinity in search of, but never reaching, the maximum likelihood until the default maximum number of iterations for the program is reached. This search of the extreme range of the parameter space impacts the estimation of the remaining parameters in the model and drives down the value of the information criterion, making the model appear more favorable. The SparseMSE model prevents this iterative search of the extreme range of the parameter space by selecting a large negative value for the maximum likelihood of the parameter for sparse or zero cell count, effectively making that value zero and removing its contribution to the maximization of the likelihood of the remaining parameters. The remaining parameters are then fit through a stepwise process to determine which dependencies should be modeled, resulting in a single model for the population size. The final approach was the Sample Coverage approach, developed by Chao and Tsay,20,26,27 implemented using the R package CARE1.28 This model estimates the population size based on the fraction observed on two or more lists. Three estimators are calculated: , assumes list independence; , accounts for list dependence and estimates the population size when sample coverage is sufficient (>= 55%); and , estimates an upper (lower) bound when there is negative (positive) dependence and sample coverage is insufficient to estimate the population size parameter itself (<55%).

Model accuracy for each scenario was evaluated according to the bias and root mean squared error (RMSE). Additional model performance metrics included the percent of simulations each model was selected as the best estimate (lowest AIC) and the percent of simulations the 95% confidence interval (CI) included the true population size. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated simulations for population sizes of 10,000 and 50,000. The relative RMSE (RRMSE) was calculated by dividing the RMSE by the true population size to compare standardized results across population sizes.

RESULTS

Table 2 shows simulation results. Under scenario 1, perfect independence, all LLMs produced valid estimates with negligible bias. The correct model assuming list independence was selected 66.4% of the time and nominal coverage of the 95% CI. Although models incorrectly including interactions were selected in over a third of simulations, these models delivered similar point estimates. Including gratuitous interactions when the underlying sampling processes were independent widened CIs but did not substantially bias estimated population size.

Table 2.

Population size estimation results from five different simulation scenarios and four capture-recapture modeling frameworks.

| Scenario 1: L1=20%; L2=25%; L3=30% | |||||

| Model | Bias | RMSE | # of times selected (%) | CI includes N (%) | Average CI width |

| 1. Independence† | 0.3 | 52.8 | 332 (66.4) | 475 (95) | 205.7 |

| 2. L1*L2 | −0.2 | 61.3 | 50 (10) | 470 (94) | 235.0 |

| 3. L1*L3 | 0.3 | 61.0 | 50 (10) | 479 (95.8) | 245.3 |

| 4. L2*L3 | −3.9 | 66.6 | 43 (8.6) | 476 (95.2) | 266.7 |

| 5. L1*L2, L1*L3 | −1.6 | 76.3 | 6 (1.2) | 472 (94.4) | 302.1 |

| 6. L1*L2, L2*L3 | −9.3 | 88.9 | 7 (1.4) | 473 (94.6) | 347.3 |

| 7. L1*L3, L2*L3 | −11.4 | 92.9 | 12 (2.4) | 479 (95.8) | 386.4 |

| 8. L1*L3, L2*L3, L1*L2 | −30.2 | 195.0 | 0 | 469 (93.8) | 752.8 |

| 9. DGA | 0.7 | 54.9 | NA | 481 (96.2) | 225.6 |

| 10. SparseMSE | 0.5 | 53.0 | NA | 475 (95) | 298.9 |

| 11. | −18.8 | 196.5 | NA | 489 (97.8) | 1117 |

| 12. | −1.1 | 52.5 | NA | 473 (94.6) | 211.9 |

| 13. | −0.1 | 69.6 | NA | 481 (96.2) | 281.3 |

| Scenario 2: L1=20%; L2=25%; L3=24% + (30%*L1) | |||||

| Model | Bias | RMSE | # of times selected (%) | CI includes N (%) | Average CI width |

| 1. Independence | 193.5 | 196.9 | 0 | 3 (0.6) | 134.0 |

| 2. L1*L2 | 232.5 | 235.4 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 130.8 |

| 3. L1*L3† | −0.6 | 66.2 | 371 (74.2) | 479 (95.8) | 271.7 |

| 4. L2*L3 | 275.3 | 277.3 | 0 | 0 | 124.8 |

| 5. L1*L2, L1*L3 | −3.4 | 87.8 | 56 (11.2) | 471 (94.2) | 355.8 |

| 6. L1*L2, L2*L3 | 333.8 | 335.0 | 6 (1.2) | 0 | 99.4 |

| 7. L1*L3, L2*L3 | −17.7 | 120.6 | 67 (13.4) | 482 (96.4) | 517.7 |

| 8. L1*L3, L2*L3, L1*L2 | −30.1 | 195.8 | 0 | 475 (95) | 789.0 |

| 9. DGA | 0.2 | 71.0 | NA | 487 (97.4) | 332.1 |

| 10. SparseMSE | 0.2 | 67.8 | NA | 166 (33) | 206.5 |

| 11. | −22.7 | 154.1 | NA | 492 (98.4) | 716.7 |

| 12. | 191.5 | 194.9 | NA | 4 (0.8) | 136.7 |

| 13. | 136.8 | 146.1 | NA | 173 (34.6) | 201.5 |

| Scenario 3: L1=20%; L2=25%; L3=25% + (45%*L1) + (20%*L1*L2) | |||||

| Model | Bias | RMSE | # of times selected (%) | CI includes N (%) | Average CI width |

| 1. Independence | 249.3 | 251.6 | 0 | 0 | 98.0 |

| 2. L1*L2 | 297.4 | 299.1 | 0 | 0 | 89.9 |

| 3. L1*L3 | −1.6 | 70.5 | 27 (5.4) | 478 (95.6) | 267.6 |

| 4. L2*L3 | 286.4 | 288.5 | 0 | 0 | 81.0 |

| 5. L1*L2, L1*L3 | −6.5 | 101.0 | 8 (1.6) | 476 (95.2) | 347.2 |

| 6. L1*L2, L2*L3 | 356.6 | 357.8 | 0 | 0 | 58.6 |

| 7. L1*L3, L2*L3 | −9.70e+9 | 1.39e+11 | 465 (93) | 134 (26.8) | ND** |

| 8. L1*L3, L2*L3, L1*L2 | −6.32e+11 | 8.29e+12 | 0 | 120 (24) | ND** |

| 9. DGA | 225.1 | 316.4 | NA | 499 (99.8) | 869.3 |

| 10. SparseMSE | −661.7 | 2,539.3 | NA | 473 (94.6) | 254.7 |

| 11. | −1,054.2 | 1,290.1 | NA | 236 (47.2) | 16,677.2 |

| 12. | 219.4 | 222.4 | NA | 2 (0.4) | 136.7 |

| 13. | 32.1 | 68.2 | NA | 448 (89.6) | 235.7 |

| Scenario 4: U=50%; L1=40%*U; L2=50%*U; L3=30% | |||||

| Model | Bias | RMSE | # of times selected (%) | CI includes N (%) | Average CI width |

| 1. Independence | 183.8 | 187.6 | 0 | 7 (1.4) | 137.5 |

| 2. L1*L2† | −9.8 | 66.3 | 372 (74.4) | 481 (96.2) | 266.9 |

| 3. L1*L3 | 237.9 | 240.9 | 0 | 0 | 133.5 |

| 4. L2*L3 | 266.0 | 268.4 | 0 | 0 | 128.9 |

| 5. L1*L2, L1*L3 | −16.8 | 95.0 | 61 (12.2) | 479 (95.8) | 379.3 |

| 6. L1*L2, L2*L3 | −22.3 | 116.8 | 66 (13.2) | 477 (95.4) | 464.0 |

| 7. L1*L3, L2*L3 | 347.1 | 348.3 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 92.5 |

| 8. L1*L3, L2*L3, L1*L2 | −42.5 | 185.7 | 0 | 481 (96.2) | 771.7 |

| 9. DGA | −10.8 | 72.4 | NA | 488 (97.6) | 320.2 |

| 10. SparseMSE | −9.8 | 66.3 | NA | 498 (99.6) | 248.2 |

| 11. | −30.7 | 162.6 | NA | 490 (98) | 479.9 |

| 12. | 196.7 | 200.0 | NA | 5 (1) | 135.3 |

| 13. | 139.3 | 148.3 | NA | 168 (33.6) | 204.5 |

| Scenario 5: U=50%; L1=2% + (20%*U); L2=3% + (20%*U); L3=6% | |||||

| Model | Bias | RMSE | # of times selected (%) | CI includes N (%) | Average CI width |

| 1. Independence | 257.7 | 273.0 | 76 (15.2) | 168 (33.6) | 356.6 |

| 2. L1*L2† | −67.0 | 287.2 | 253 (50.6) | ND** | ND** |

| 3. L1*L3 | 300.9 | 314.5 | 42 (8.4) | ND** | ND** |

| 4. L2*L3 | 306.9 | 320.6 | 41 (8.2) | ND** | ND** |

| 5. L1*L2, L1*L3 | −7.11e+9 | 1.59e+11 | 28 (5.6) | ND** | ND** |

| 6. L1*L2, L2*L3 | −3.53e+10 | 4.96e+11 | 27 (5.4) | ND** | ND** |

| 7. L1*L3, L2*L3 | 365.9 | 377.1 | 33 (6.6) | ND** | ND** |

| 8. L1*L3, L2*L3, L1*L2 | −2.09e+11 | 2.69e+12 | ND** | ND** | |

| 9. DGA | 312.7 | 319.7 | NA | 0 | 338.7 |

| 10. SparseMSE | 258.6 | 296.1 | NA | 144 (28.8) | 359.1 |

| 11. | −454.6 | 3,373.5 | NA | 411 (82.2) | 67,275.0 |

| 12. | 206.8 | 229.4 | NA | 279 (55.8) | 426.2 |

| 13. | 175.4 | 217.4 | NA | 382 (76.4) | 536.6 |

L1= List 1; L2= List 2; L3= List 3; U= binary third variable; CI= confidence interval; DGA= Decomposable Graph Approach; = Sample Coverage model assuming independence; = Sample Coverage model allowing list dependence and sufficient sample coverage fraction (>=55%); = Sample Coverage model estimating lower(upper) bound estimate due to insufficient sample coverage fraction (<55%); RMSE = Root Mean Squared Error

N=1,000 (the true population size)

Indicates the correct log-linear model for each scenario

ND**=Not Defined. Upper limit of confidence interval not defined in simulations; therefore, average confidence interval width could not be calculated.

Bias = (); RMSE = ); where is the estimated population size from simulation i, m is the number of simulations, and N is the true population size.

In scenario 2 the correct model was selected the majority of simulations (74.2%). In most cases when the correct model was not selected, another model that included the L1L3 interaction among other interaction terms was chosen. These models calculated valid size estimates with moderately wider CIs.

In scenario 3, generated with a third-order dependency, the model selected most often (93%) grossly over-estimated the population size (9.7 billion times higher than the truth). The CIs had poor coverage, containing the truth only 26.8% of the time. The two models selected the remaining 7% of simulations, each included the L1L3 interaction and accurately estimated the population size with valid CIs.

In scenario 4, the correct model was selected 74.4% of the time, with valid CIs. Other models selected almost always included the L1L2 interaction and had accurate estimates with appropriate (albeit wider) coverage.

In scenario 5, where sampling probabilities were greatly reduced, the correct model, which included an L1L2 interaction term, calculated valid size estimates on average, but was only selected in half of simulations (50.6%). The CI for this model, and most others in this scenario, could not be calculated due to undefined upper limits. The next most oft selected model assumed independence and resulted in nearly four times the bias and poor CI coverage. Other selected models increased in bias to unacceptable levels.

The DGA model provided approximately correct estimates for most scenarios. Although this model underestimated the truth in scenario 4, the 95% credible intervals were conservative, including the truth nearly 100% of simulations. When capture probabilities were small (scenario 5), results indicated moderate bias and 95% credible intervals that never included the truth.

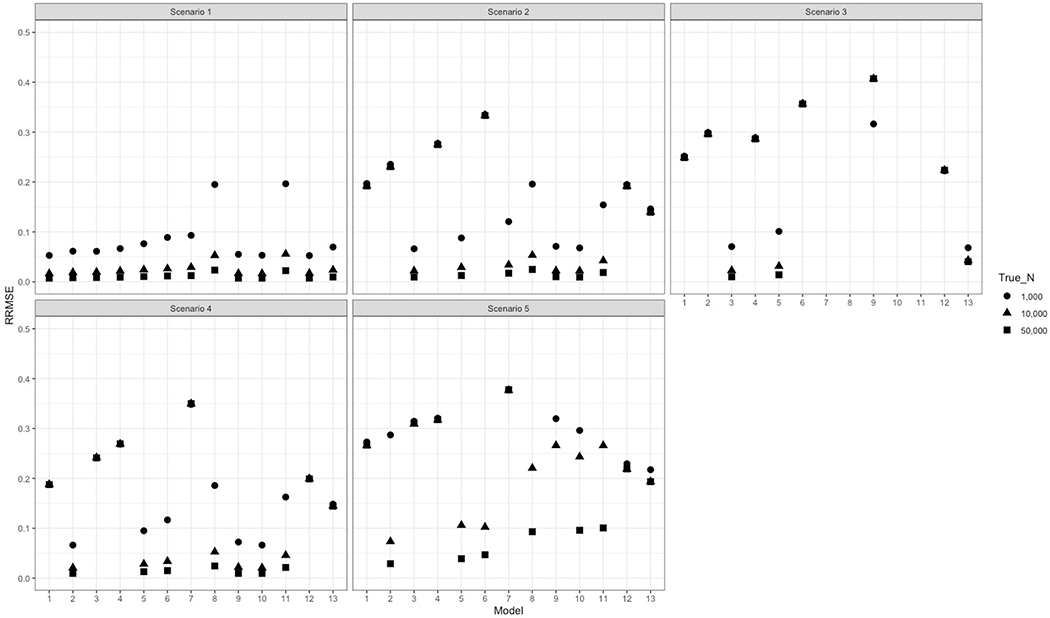

The SparseMSE model produced reasonably accurate estimates for most scenarios. In scenarios 3 and 5, which were most likely to include small list intersections (Figure 1), the model did not overcome the statistical bias. Bias was moderate in scenario 3, though far preferable to the best-fitting LLMs, and CIs had appropriate coverage. In scenario 5, the bias was again moderate, though comparable to or less than most other models, however the CI included the truth in less than 1/3 of simulations.

Figure 1.

Plotted interquartile ranges of the distribution of cell counts for each list intersection from 500 simulations for each scenario featuring a different list dependency structure.

L1= (List 1=1, List 2=0, List 3=0); L2 = (List 1=0, List 2=1, List 3=0); L3 = (List 1=0, List 2=0, List 3=1); L1xL2 = (List 1=1, List 2=1, List 3=0); L1xL3 = (List 1=1, List 2=0, List 3=1); L2xL3 = (List 1=0, List 2=1, List 3=1); L1xL2xL3 = (List 1=1, List 2=1, List 3=1). Where 1=observed on list, 0=not observed on list

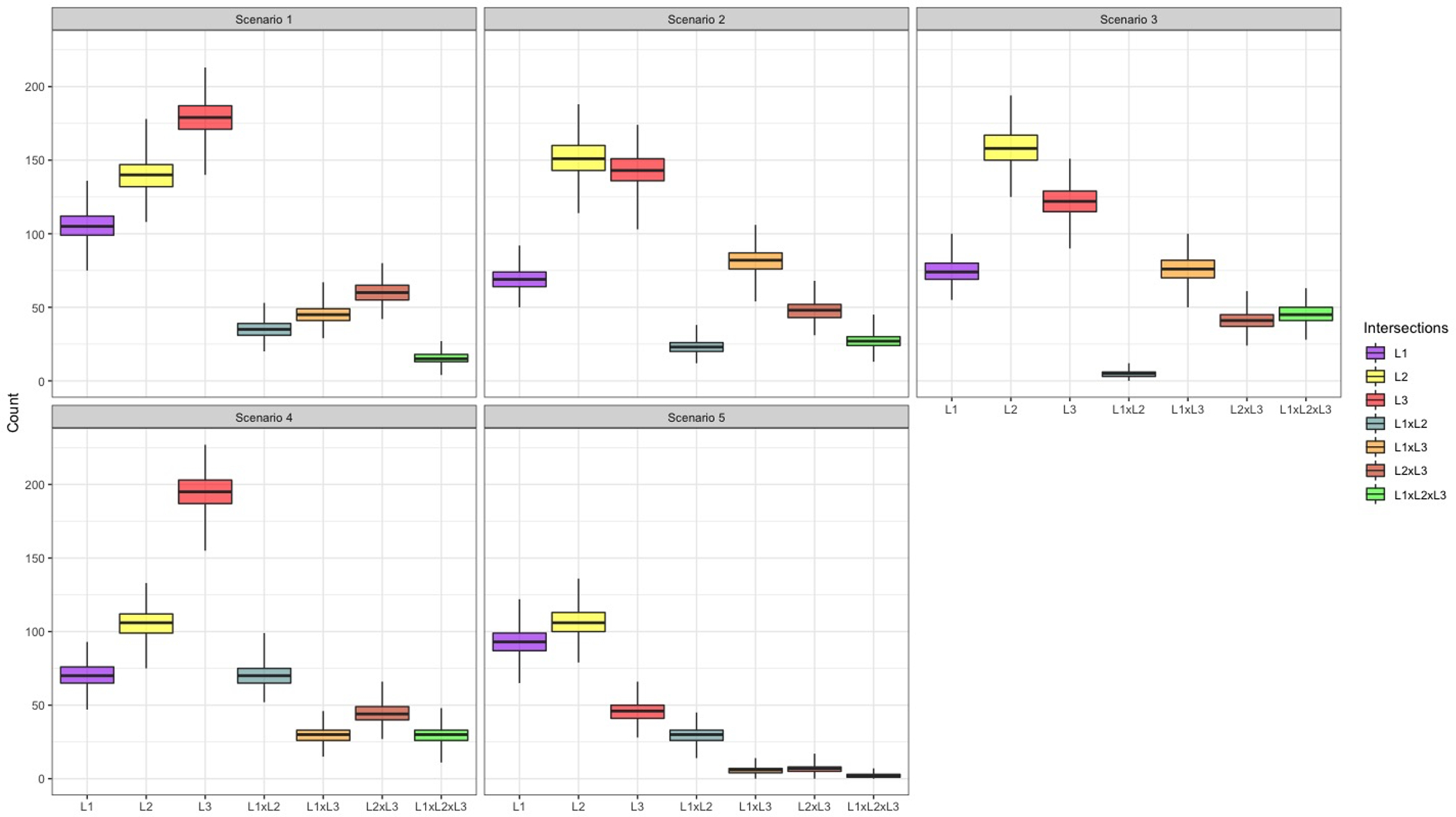

In nearly all scenarios, at least one of the three Sample Coverage estimators demonstrated high accuracy and appropriate CI coverage. The estimator with the least bias did not always align with the true data structure (e.g., was most biased in scenario 1 and the least biased in scenario 2; Table 2). Although model robustness declined in scenario 5, performance metrics still outperformed other leading models (including DGA and SparseMSE). As the true population size increased, relative accuracy of each of the estimators improved as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative Root Mean Squared Error (RRMSE) for each capture-recapture model under varying list dependency structure scenarios and true population sizes.

Model 1 = Base

Model 2 = Base + L1*L2

Model 3 = Base + L1*L3

Model 4 = Base + L2*L3

Model 5 = Base + L1*L2 + L1*L3

Model 6 = Base + L1*L2 + L2*L3

Model 7 = Base + L1*L3 + L2*L3

Model 8 = Base + L1*L3 + L2*L3 + L1*L2

Model 9 = Decomposable Graph Approach (DGA; Bayesian Model Averaging)

Model 10 = SparseMSE

Model 11 = Sample Coverage −

Model 12 = Sample Coverage −

Model 13 = Sample Coverage −

Base= main terms corresponding to each individual list, does not include list interactions (log-linear model)

DISCUSSION

Naïve CRC calculated the population size with minimal bias and appropriate CIs in most scenarios. Results from scenario 4 were surprising because some members of the population had zero probability of capture on two of the three lists. Our simulations suggest that the assumption that all members of the population must have non-zero chance of being on all lists may be relaxed if there is at least one list for which all members have a positive probability of representation.

However, the naïve CRC approach selected biased estimates with third-order list dependencies so extreme that they produced sparse or zero list overlaps (scenario 3). In this scenario, the model selected by naïve CRC overestimated the truth, producing implausibly large size estimates with CIs that contained the truth only a quarter of the time. We observed this result in our empirical study in Alameda County.9 Our simulation demonstrates that as list overlaps shrink, uncertainty in the model increases as two- and three-way interaction coefficients are determined by a small number of people. In addition, small cell counts for some overlaps will impact the entire model because coefficients are jointly determined, which in turn further alters the prediction. We observe similar findings in scenario 5, which also suffers from small counts at list intersections, resulting in models selected with moderate to severe bias in nearly half of simulations.

Our results align with a recent simulation study by Gutreuter, which highlights the unreliability of naïve CRC to select the model that matches the correct data structure and variation in encounter probabilities.29 The performance of naïve CRC improves with the number of lists and encounter probabilities but, as shown here as well, is generally outperformed by the DGA model.

The DGA model produced accurate estimates in nearly every scenario, along with 95% credible intervals with excellent coverage. Even with complex third-order interaction and sparse or zero overlap counts (scenario 3), the DGA model produced 95% CIs that contained the truth in nearly every simulation. In scenario 3, the magnitude of the bias for estimates from this model was minimal compared to the enormous and implausible over-estimates produced by naïve CRC. Notably, in scenario 5, where sampling probabilities were low, the 95% CIs for the DGA model never covered the truth. This persisted at higher population sizes (Supplementary Tables). Our results build upon Gutreuter’s simulation study by evaluating the performance of two additional models applied less often in epidemiology. Suprisingly, the SparseMSE model did not overcome the bias resulting from sparse cells in scenarios 3 and 5. While accuracy and CI coverage improved with higher population sizes in scenario 5 (Figure 2, Supplementary Table), both worsened at higher population sizes in scenario 3. In contrast, results from the Sample Coverage estimators were generally robust to variations in capture probabilities and performance improved with increasing population size.

LIMITATIONS

We were not exhaustive in our selection of models. For example, multinomial logit models have been applied to capture-recapture problems to model heterogeneities in capture probabilities due to individual-level covariates.30,31 Latent class modeling has also been used to satisfy the list independence assumption, conditional on assigning individuals to latent classes.32,33 Additional innovative estimators using machine learning and doubly robust methods are currently in the pipeline.34,30 While our simulation study does not comment on these specific estimators, the conclusion of our study encourages using multiple different estimators for triangulation, as the direction and magnitude of the overall bias brought on by assumption violations may be unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Results from our simulation study reveal the dramatic impact of just a few cells with sparse cell counts (as both a function of the underlying population size and the list sampling probabilities). Uncritical reliance on the information criterion for model selection often performed well but sometimes failed spectacularly. We warn against routinely relying on this practice without evaluating more robust models. Our simulation study also demonstrates the importance of including multiple different types of statistical modeling. When the DGA model and the best fitting model gave similar estimates, the best-fitting model was generally acurate and had slightly narrower CIs. When they diverged, the DGA model was more accurate and gave informatively wide CIs. Although not consistently the most accurate, the Sample Coverage model was among the most robust to variations in capture probabilities and population size. Therefore, we recommend both the DGA and Sample Coverage as default models in future CRC studies. However, we, like Gutreuter, caution against inferring the underlying data structure from the selected model(s). The true correlations between administrative lists and the selection factors that compose those lists are likely complex in epidemiologic applications. Implementing a combination of models that each address different potential limitations of CRC analysis can reduce the impact of some biases and better triangulate the truth.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was supported by a career development award through the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NIAID K01 AI145572). We also thank the peer reviwer for comments that improved the rigor and focus of this evaluation of capture-recapture estimators.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CRC

Capture-Recapture

- DGA

Decomposible Graph Approach

- L1

List 1

- L2

List 2

- L3

List 3

- LLM

Log-Linear (Regression) Model

- PP

Percentage Points

- PSE

Population Size Estimation

REFERENCES

- 1.Neal JJ, Prybylski D, Sanchez T, Hladik W. Population Size Estimation Methods: Searching for the Holy Grail. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2020;6(4):1–7. doi: 10.2196/25076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesson P, Reingold A, McFarland W. Theoretical and Empirical Comparisons of Methods to Estimate the Size of Hard-to-Reach Populations: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1678-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forcasting. Capture-recapture and multiple-record systems estimation. I: History and theoretical development. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1047–1058. http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/82976. Accessed April 28, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forcasting. Capture-Recapture and Multiple-Record Systems Estimation II: Applications in Human Diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1059–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post LA, Balsen Z, Spano R, Vaca FE. Bolstering gun injury surveillance accuracy using capture – recapture methods. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):674–680. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00017-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raskind-Hood C, Hogue C, Overwyk KJ, Book W. Estimates of adolescent and adult congenital heart defect prevalence in metropolitan Atlanta, 2010, using capture-recapture applied to administrative records. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;32:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taherpour N, Mehrabi Y, Seifi A, Eshrati B, Nazari SSH. Epidemiologic characteristics of orthopedic surgical site infections and under-reporting estimation of registries using capture- recapture analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreshpaj B, Bodin T, Wegman DH, et al. Under-reporting of non-fatal occupational injuries among precarious and non-precarious workers in Sweden. Occup Env Med. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2021-107856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales-Gamarra O, Alva-diaz C, Pacheco-Barrios K, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Peru: National prevalence study using capture-recapture analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthias J, Bernard S, Schillinger JA, Hong J, Pearson V, Peterman TA. Estimating Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Incidence and Mortality Using Capture-recapture, Florida. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(3):506–512. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guure C, Dery S, Afagbedzi S, et al. National and subnational size estimation of female sex workers in Ghana 2020: Comparing 3-source capture-recapture with other approaches. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khandu L, Tobgay T, Kinley K, et al. Characteristics and Population Size Estimation of Female Sex Workers in Bhutan. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(10):754–760. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okiria AG, Bolo A, Achut V, et al. Novel Approaches for Estimating Female Sex Worker Population Size in Conflict-Affected South Sudan. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2019;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.2196/11576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen LT, Patel S, Nguyen NT, et al. Population Size Estimation of Female Sex Workers in Hai Phong, Vietnam: Use of Three Source Capture – Recapture Method. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11(2):194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fienberg SE. The Analysis of Cross-Classified Categorical Data. Second Edi. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cormack RM, Chang Y, Smith GS. Estimating deaths from industrial injury by capture-recapture: a cautionary tale. 2000:1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wesson P, Murgai N. Evaluating the Completeness of HIV Surveillance Using Capture – Recapture Models, Alameda County, California. AIDS Behav. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1883-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones HE, Hickman M, Welton NJ, De Angelis D, Harris RJ, Ades AE. Recapture or Precapture? Fallibility of Standard Capture-Recapture Methods in the Presence of Referrals Between Sources. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(11):1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huggins R A note on the difficulties associated with the analysis of capture – recapture experiments with heterogeneous capture probabilities. Stat Probab Lett. 2001;54:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chao A, Tsay PK. A Sample Coverage Approach to Multiple-System Estimation with Application to Census Undercount A Sample Coverage Approach to Multiple-System Estimation With Application to Census Undercount. J Am Stat Assoc. 1998;93(441). doi: 10.1080/01621459.1998.10474109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivest L-P, Baillargeon S Rcapture: Loglinear Models for Capture-Recapture Experiments. R package version 1.4–2. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johndrow J, Lum K, Ball P. dga: Capture-Recapture Estimation using Bayesian Model Averaging. R package version 1.2. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madigan D, York J. Bayesian methods for estimation of the size of a closed population. Biometrika. 1997;84(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan L, Silverman BW, Vincent K. Multiple Systems Estimation for Sparse Capture Data: Inferential Challenges When There Are Nonoverlapping Lists. J Am Stat Assoc. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2019.1708748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan L, Silverman B, Vincent K. SparseMSE: “Multiple Systems Estimation for Sparse Capture Data.” 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/package=SparseMSE.

- 26.Tsay PK, Chao A. Population size estimation for capture-recapture models with applications to epidemiological data. J Appl Stat. 2001;28(1):25–36. doi: 10.1080/02664760120011572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chao A, Tsay PK, Lin SH, Shau WY, Chao DY. The applications of capture-recapture models to epidemiological data. Stat Med. 2001;20(20):3123–3157. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11590637. Accessed May 6, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh TC. CARE1: Statistical package for population size estimation in capture-recapture models. 2012.

- 29.Gutreuter S Comparative performance of multiple-list estimators of key population size. PLOS Glob Public Heal. 2022;2(3):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilling K, Sterne AC, Da C. Estimation of the incidence of stroke using a capture-recapture model including covariates. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilling K, Sterne JAC. Capture-Recapture Models Including Covariate Effects. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(4):392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manrique-vallier D Bayesian Population Size Estimation Using Dirichlet Process Mixtures. Biometrics. 2016;72:1246–1254. doi: 10.1111/biom.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doshi RH, Apodaca K, Ogwal M, et al. Estimating the Size of Key Populations in Kampala, Uganda: 3-Source Capture-Recapture Study. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2019;5(3):1–9. doi: 10.2196/12118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You Y, Van Der Laan M, Collender P, et al. Estimation of population size based on capture recapture designs and evaluation of the estimation reliability. arXiv:210505373. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.05373. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.