Abstract

The positive effect of nostalgia provides an effective way to improve subjective well-being. However, there is little research on the relationship between nostalgia and subjective well-being, especially the mechanism of this link. This study tested the positive effects of nostalgia on emotional well-being (positive affect and negative affect) and cognitive well-being (satisfaction with life) via gratitude. Two experiments were conducted in samples of young adults who were randomized to experimental or control conditions. The analyses involved group comparisons as well as regression-based analyses of mediation. In Experiment 1 (N = 196), we induced nostalgia using a guided autobiographical recall procedure. The nostalgia group had higher positive affect and gratitude, and gratitude partially mediated the association between nostalgia and positive affect. In Experiment 2 (N = 102), we induced nostalgia by showing a nostalgic video from the period when the participants were children. The nostalgia group had higher positive affect and lower negative affect, and gratitude partially mediated these associations. The findings suggest that nostalgia could improve emotional well-being by increasing gratitude, but may not alter cognitive well-being.

Keywords: Nostalgia, Subjective well-being, Gratitude, Emotional well-being, Cognitive well-being

Introduction

As the forefront topic in positive psychology, how to improve individuals’ subjective well-being has been widely discussed (Anglim et al., 2020; Diener et al., 2018; Song & Gao, 2020). Research suggests that emotional experiences are essential components of subjective well-being (Diener & Emmons, 1984), and nostalgia, as a reservoir of positive emotions (Wildschut et al., 2006), is intrinsically associated with subjective well-being (Cox et al., 2015; Hepper et al., 2021; Routledge et al., 2013; Sedikides et al., 2016). Nostalgia can facilitate social connection and alleviate loneliness (Polletta & Callahan, 2017), which is also one of the primary coping mechanisms applied despite chronic isolation, fear, and widespread deprivation of freedom (Lee & Kao, 2021). When individuals experience nostalgia, they typically bring back reflections of experiences with close people, or of significant events such as the weddings and family reunions (Wildschut et al., 2006, 2011). Memories over past events (i.e., nostalgia) can be considered important assets in one's life, which makes it easier for individuals to find meaning and increase their satisfaction with life (Webster et al., 2010).

Gratitude, as a typical positive trait and positive emotional experience, is one of the key components of Positive Psychology. Positive Psychology focuses on human' positive traits and self-value, and gratitude is a subjective positive emotion elicited from positive experiences (Bono & Froh, 2009; Froh et al., 2011). Studies have examined the positive effects of state gratitude on the increased well-being (Algoe et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2021; Nezlek et al., 2017, 2019; Sztachańska et al., 2019; Zygar et al., 2018). State gratitude is associated with higher optimism, greater satisfaction with life, more pro-social behavior, higher social support, and lower negative emotions (Froh et al., 2008). Additionally, when facing upward social comparisons, individuals with high levels of state gratitude are likely to adopt strategies of greater positivity, thereby suppressing negative emotions such as envy (Mao et al., 2021). As such, gratitude is important for the experience of happiness (Watkins et al., 2018). However, few scholars have proposed whether the temporary evocation of gratitude in daily life is still exerted on well-being positively? It also lacks some discussion on how nostalgia works on subjective well-being, does nostalgia alleviate negative emotions effectively, and how come it can increase positive affect remains unclear (Rao et al., 2018). Moreover, there is a paradox in the relationship between nostalgia and negative affect in existing studies (Holak & Havlena, 1998; Leunissen et al., 2021; Wildschut et al., 2006).

To tackle above issues, this study examined state gratitude as the mechanism by which nostalgia affects subjective well-being. First, we tested whether nostalgia has positive effects on subjective well-being, which is defined in terms of emotional well-being (higher positive affect and lower negative affect) and cognitive well-being (satisfaction with life). Focusing on the distinction between the emotional and cognitive aspects of subjective well-being, we delved into how nostalgia increases subjective well-being. Second, we tested the mediation effect of state gratitude on the relationship between nostalgia and SWB, which broadened and deepened our understanding of how nostalgia affects subjective well-being, as well as enriched the studies on the influencing factors of state gratitude and its impact on well-being.

Literature Review and Hypothesis

The concept and Phenomenon of Nostalgia

The word nostalgia originated from the combination of nostoc (returning home) and algos (pain) in Greek, which literally means the pain caused by homesickness and was initially regarded as a psychiatric disorder with symptoms of anxiety, sadness, and insomnia (Sedikides et al., 2008). Gradually, nostalgia has become a universal experience: It concerns all persons, regardless of age, gender, social class, ethnicity, or other social groupings (Sedikides et al., 2004). Studies of college students have shown that 79% of participants experience nostalgia at least once a week (Wildschut et al., 2006). Nostalgia is generally triggered by external stimuli associated with the past. These can be social or nonsocial stimuli (Holak & Havlena, 1998; Holbrook, 1993). Examples of social stimuli include friends, family members, social events such as birthdays and reunions, and major life events such as getting married. Nonsocial stimuli include examples such as music, smells, and coldness (Wildschut et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008) as well as adverse weather (Van Tilburg et al., 2019).

Nostalgia is a complex emotion. Some researchers have regarded nostalgia as a positive emotional experience (Holak & Havlena, 1998; Pascal et al., 2002; Wildschut et al., 2006). However, some other scholars believe that nostalgia is a negative and painful emotion (Holbrook & Schindler, 1991; Sedikides et al., 2006). Additionally, some scholars have synthesized and defined nostalgia as a bittersweet emotion (Barrett et al., 2010; Merchant et al., 2013; Werman, 1977), which means that when experiencing nostalgia, individuals may feel happy or slightly sad (Hepper et al., 2012). Davalos et al. (2015) also reported that the emotions expressed in Facebook conversations tend toward the positive and often contain mixed emotions, which is consistent with the bittersweet nature frequently discussed and debated in the nostalgia literature. When experiencing nostalgia, individuals usually recall significant others or events in their lives as protagonists, indicating that nostalgia is an emotional experience related to the self and significant others (Wildschut et al., 2006).

Nostalgia and Subjective Well-being

Nostalgia is an important resource for maintaining and promoting individuals’ physical and psychological health. For example, nostalgia can not only alleviate some of the physiological pain caused by cold water (Zhou et al., 2012a, 2012b), it can also buffer the perceived threat of mortality (Sedikides & Wildschut, 2018), promote social connection and positive self-regard (Wildschut et al., 2006). Nostalgia is also positively associated with self-continuity (Sedikides et al., 2008), prosocial behavior (Zhou et al., 2012a, 2012b), and existential meaning (Routledge et al., 2012). Besides, it is helpfully strengthening individuals’ intrinsic motivation and work effort (Van Dijke et al., 2019).

Subjective well-being is a comprehensive psychological construct that refers to personal quality of life. It is thought to include two essential components: emotional experience and life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1999). The former refers to the emotional experience of life events, including positive emotions (e.g., pleasure, ease, etc.) and negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.); the latter refers to the cognitive evaluation of the overall quality of life—that is, a judgment of one's personal life on the whole (Li et al., 2016). Subjective well-being is characterized by more positive emotions, fewer negative emotions, and a relatively high sense of life satisfaction. Positive and negative affect are independent factors (Diener & Emmons, 1984), which means that individuals’ scores on positive emotions do not necessarily indicate their scores on negative emotions, and vice versa, thus, nostalgia may affect on them differently. Life satisfaction is a crucial indicator of subjective well-being and as a cognitive factor that is independent of positive and negative emotions (Diener, 2000).

Previous studies explored the relationship between nostalgia and positive affect or satisfaction with life separately (Cox et al., 2015; Leunissen et al., 2021; Wildschut et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2018). In this study, we operationalized nostalgia as the arousal of positive memories and explored its different effects on the components of subjective well-being (including positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction with life). In the nostalgic condition, individuals may experience an increase in positive emotions such as warmth, relief and satisfaction by recalling past events, and they may also experience an alleviation of negative emotions such as anxiety. Additionally, the nostalgic positive evaluation of the past is based in part on the evaluation of the current situation (Davis, 1979); by comparing the present with the past, individuals may evaluate their current life more positively. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H1

Nostalgia will increase individuals’ subjective well-being. Specifically, nostalgia will increase positive affect (H1a), decrease negative affect (H1b), and increase satisfaction with life (H1c).

Gratitude as Mediator Between Nostalgia and Subjective Well-being

Gratitude is defined as an individual's positive emotional response to others' assistance and kindness (Grant & Gino, 2010; Mccullough et al., 2001; Spence et al., 2014; Tsang, 2006), which includes trait gratitude and state gratitude. State gratitude is a positive emotion of short duration and can change dramatically (Emmons & Mccullough, 2003; McCullough et al., 2004). It is generally activated by specific events or circumstances referring to the receipt of material or non-material assistance from others in everyday life and work (Mccullough et al., 2001). Research on gratitude suggests that receiving gifts or assistance from others stimulates the feelings of gratitude (Emmons & Crumpler, 2000; Grant & Gino, 2010; Mccullough et al., 2001, 2008; Tsang, 2006). Nostalgia is primarily a positive, self-relevant social emotion (Hepper et al., 2012; Sedikides et al., 2008), whose principal source is the recollection of significant life events, generally involving fond and personally meaningful memories of childhood or intimate relationships (Hepper et al., 2012). When individuals experience nostalgia, they typically recall past experiences with close associates, such as friends and family, or significant events like weddings and family reunions (Wildschut et al., 2006, 2011). These specific memories concerning interactions with others tend to be more positive and able to recall back to those good times (Evans et al., 2021). State gratitude is an emotion connected with social interactions, often induced by interventions (Dickens, 2017; Sedikides & Wildschut, 2020; Sedikides et al., 2015), hence when individuals recall past events, they probably think of the assistance and support received from significant others, which leads them to a sense of gratitude for what they have (Puente-Díaz & Cavazos-Arroyo, 2021).

Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H2

Nostalgia will increase individuals' gratitude.

Studies have shown that state gratitude enables individuals to better cope with incidents and regulate their behavior, which in turn leads to a better understanding of well-being (Mccullough et al., 2001). Many studies on subjective well-being have been based on the theory of happiness, which maintains that overall well-being involves the pursuit of happiness and subjective well-being (including high positive emotions, low negative emotions, high life satisfaction and avoidance of pain) (Li et al., 2022). It is demonstrated that state gratitude interacts with high and low arousal-positive emotions (McCullough et al., 2008) and can affect subjective well-being by boosting positive experiences and buffering negative affects (Nelson, 2009; Ouweneel et al., 2014). Interventions that encourage participants to reflect on gratitude for a person, an object, or a particular moment contribute to increased subjective well-being, greater life satisfaction, the feeling of optimism and self-esteem, as well as reduced negative affect (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Froh et al., 2008; Rash et al., 2011). For example, interventions to induce gratitude could aid older adults and patients in alleviating anxiety and depression symptoms, improving mental health and maintaining relational well-being (Cregg & Cheavens, 2021; Dickens, 2017; Emmonse & Mccullough, 2003). Bohlmeijer et al. (2021) revealed that long-term practices of gratitude interventions did increase well-being, despite failure to reduce distress. Bohlmeijer et al. (2021) revealed that long-term practices of gratitude interventions did increase well-being, despite failure to reduce distress. Giving even brief gratitude interventions, such as meditating or memorizing previous positive experiences for a few sustained minutes, helped improve immediate mood (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Watkins et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2010).

Thus, we hypothesized that:

H3

Gratitude will mediate the relationship between nostalgia and subjective well-being. Specifically, nostalgia will increase individuals' positive affect (H3a), decrease negative affect (H3b), and increase satisfaction with life (H3c) through gratitude.

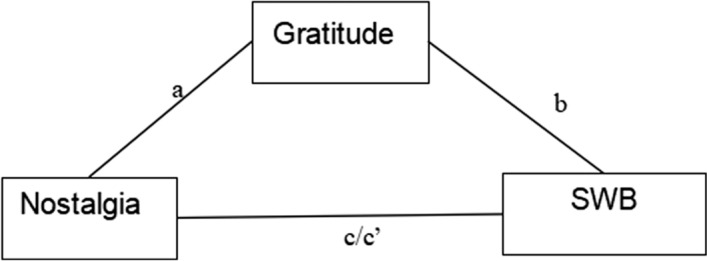

We conducted two experiments. All participants in the current study provided informed consent. The participants were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. They were also told that their responses would be kept confidential. In Experiment 1, we induced nostalgia with a guided autobiographical recall procedure to test whether nostalgia had a causal effect on subjective well-being. Subjective well-being was defined as emotional well-being (positive affect and negative affect) and cognitive well-being (satisfaction with life). Self-reported gratitude was tested as a mediator of the association between nostalgia and these two aspects of subjective well-being. Experiment 2 was conducted to replicate the results of Experiment 1 using a different induction method, namely, a nostalgic video. The full model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of the full model. SWB = subjective well-being. The model specifies a direct positive effect of nostalgia on SWB (path c) and a positive indirect effect of nostalgia on SWB via gratitude (path ab). The indirect effect consists of a positive effect of nostalgia on gratitude (path a) and a positive effect of gratitude on SWB (path b). Paths c′ denote partial effects of nostalgia on SWB when gratitude is introduced as a mediator

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we manipulated nostalgia by using the classic paradigm in which participants randomized to recall a nostalgic memory (nostalgia condition) or an ordinary memory (control condition) from their past (Routledge et al., 2011; Wildschut et al., 2006). The effects of nostalgia on gratitude and subjective well-being were then measured. We tested the hypotheses that nostalgia improves both emotional well-being and cognitive well-being and that these effects are mediated by gratitude.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were 196 Chinese undergraduate students from a large public university, ranging in age from 18 to 24 years (140 females, Mage = 21.74, SDage = 1.36). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (nostalgia vs. control) and they were given a small monetary reward to thank them for their time and effort. Calculated using G*power, when the total sample size is 196, assuming α = 0.005, β = 0.95, the effect size f for F tests is 0.26 (medium).

Procedure

Manipulation. We induced nostalgia using a recall procedure (Wildschut et al., 2006, see Study 5; see also Routledge et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008). In the nostalgia condition, participants read some examples of nostalgia and were asked to bring to mind a nostalgic event in their life: “Specifically, try to think of a past event that makes you feel most nostalgic. Take a few moments to think about the nostalgic event and how it makes you feel.” In the control condition, participants read a description of scenic spot and were asked to write down keywords or sentences to briefly reflect on the scenery and their feelings.

Manipulation check. Following this instruction, participants were asked to complete a manipulation check (Wildschut et al., 2006) consisting of three items, for example, "Right now, I am feeling quite nostalgic," "Right now, I have nostalgic thoughts," and "I feel nostalgic at the moment" (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree; α = 0.912). Attesting to the effectiveness of the manipulation, participants in the nostalgia condition reported feeling more nostalgic than those in the control condition, t(1, 194) = 6.711, d = 0.966.

Materials

Gratitude. Gratitude was measured using the self-report Gratitude Schedule (McCullough et al., 2002). Participants were given three gratitude-related adjectives (grateful, thankful, and appreciative) and asked how accurately each adjective described them (1 = inaccurate, 6 = accurate). The internal consistency was α = 0.955.

Subjective well-being. Subjective well-being included emotional well-being and cognitive well-being. Emotional well-being was measured by the Revised Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) (Qiu et al., 2008), which consists of 9 items assessing positive affect (PA; e.g., “interested,” “enthusiastic”; α = 0.928) and 9 items assessing negative affect (NA; e.g., “distressed, “upset”; α = 0.877). Participants were instructed to indicate how they felt by rating the PANAS items on a six-point scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 6 = extremely). Cognitive well-being was measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985). All five items are rated on a six-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree, α = 0.631). The SWLS is a widely used and well-validated scale (Pavot & Diener, 1993).

Results

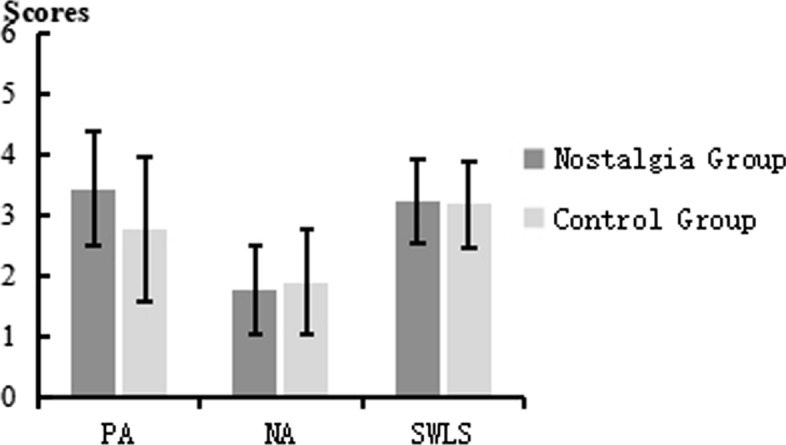

Group differences. As expected, participants in the nostalgia condition (M = 3.42, SD = 0.95) scored significantly higher on the PA index than those in the control condition (M = 2.76, SD = 1.18), F(1, 194) = 18.785, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.088. However, there was no significant group difference for NA (Mnostalgia = 1.76, SD = 0.73 vs. Mcontrol = 1.88, SD = 0.87; F(1, 194) = 1.028, p = 0.312, η2 = 0.005) or SWLS (Mnostalgia = 3.22, SD = 0.70 vs. Mcontrol = 3.17, SD = 0.72, F(1, 194) = 0.197, p = 0.658, η2 = 0.001). Thus, H1a was supported, but not H1b or H1c. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The PA, NA, and SWLS in Experiment 1. PA = positive affection; NA = negative affection; SWLS = satisfaction with life scale. The vertical bars represent the range of ± 1 SD. The results show significant group difference for PA, but not for NA and SWLS

Gratitude. Participants in the nostalgia condition (M = 4.47, SD = 1.24) reported significantly more gratitude than those in the control condition (M = 3.52, SD = 1.51), F(1, 194) = 22.879, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.105, which supported H2. Furthermore, gratitude was positively correlated with nostalgia, r(196) = 0.61, p < 0.001, and with PA, r(196) = 0.42, p < 0.001. There was no significant relationship between gratitude and NA, r(196) = 0.082, p = 0.25, or between nostalgia and SWLS, r(196) = 0.09, p = 0.193. These results indicated that gratitude qualified as a potential mediator of the nostalgia effect on PA.

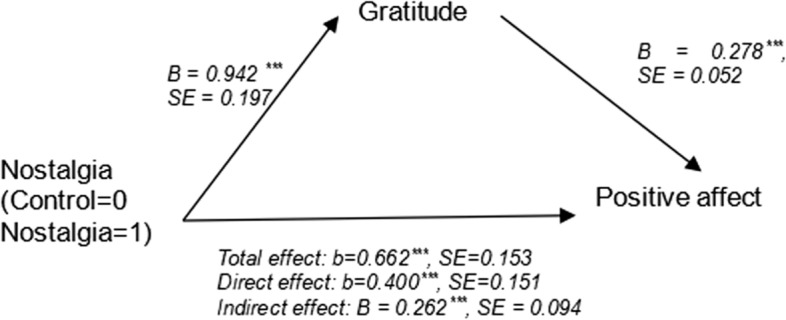

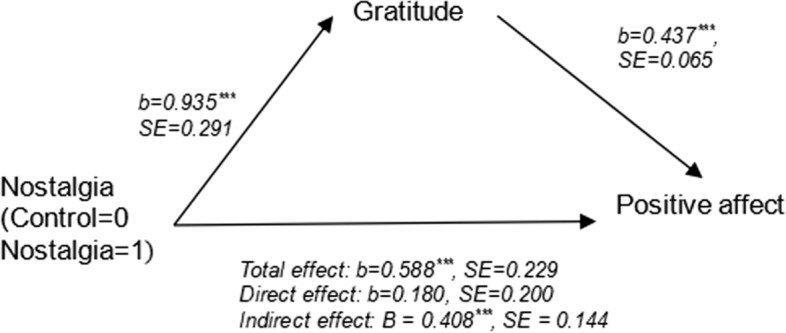

Gratitude as a mediator. We used the PROCESS macro in SPSS, Model 4 (Hayes, 2017; Preacher & Hayes, 2004) (5000 bootstrap samples) to test the indirect effect of nostalgia on SWB via gratitude. Group assignment was the independent variable, and was coded as 0 = control, 1 = nostalgia. Nostalgia was significantly positively related to positive affect, and the indirect effect via gratitude was significant: B = 0.262, SE = 0.094, 95% CI [0.106, 0.474]. The mediation effect explained 40% of the variance in the total effect. The conditional direct effect was still significant, B = 0.400, SE = 0.151, 95% CI [0.102, 0.698], which suggests partial mediation. Thus, H3a was partially supported. Nostalgia was not significantly associated with either negative affect (B = -0.117 SE = 0.115, 95% CI [− 0.344, 0.110]) or satisfaction with life (B = 0.045, SE = 0.101, 95% CI [-0.155, 0.245]). Thus, H1b and H1c were not supported. See Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Mediation of the effect of nostalgia on positive affect by gratitude in Experiment 1. All coefficients are unstandardized. ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Experiment 1 provides partial support for our conceptual model. Nostalgia predicted positive affect both directly and indirectly through the partial mediating effect of gratitude. Contrary to expectations, nostalgia not associated with lower negative affect or higher satisfaction with life. Considering the possibility that particular manipulation may effect on nostalgia and state gratitude, we used a different paradigm to manipulate nostalgia in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

The objective of Experiment 2 was to provide corroborating evidence of the direct salutary effect of nostalgia on subjective well-being, and of the mediating role of gratitude in this association, using a different paradigm to manipulate nostalgia. Nostalgia was induced using a video showing objects from the period corresponding to the participants' childhoods.

Method

Participants and Design

We recruited 102 undergraduate students (55.9% female) from a large public university to participate in the experiment. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 24 years (M = 21.74, SD = 1.36). They were randomly assigned to the nostalgia condition or the control condition. At the end of the experiment, the participants received a small monetary reward to thank them for their effort. Calculated using G*power, when the total sample size is 102, assuming α = 0.005, β = 0.95, the effect size f for F tests is 0.36 (medium).

Procedure and Materials

Nostalgia manipulation. In the nostalgia condition, all participants watched a video related to the college students’ childhood memories, which included snacks, toys, electronic games and animations from that era when they were children, with corresponding nostalgic music. In the control condition, participants watched a neutral video showing natural landscapes with background music as pure music. To enhance the validity of our study, the duration of both videos was equivalent at 5 min. Screenshots from the videos were showed in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Screenshots from the videos

Manipulation check. The three manipulation check items were the same as those in Experiment 1. As expected, participants in the nostalgia condition reported feeling more nostalgic than those in the control condition, t(1, 100) = 7.039, d = 1.399.

Materials. The same questionnaires used in Experiment 1 were used in Experiment 2. As in Experiment 1, the measures all showed good internal consistency: α = 0.941 for the Gratitude Schedule; α = 0.925 for PA; α = 0.761 for NA; α = 0.808 for SWLS.

Results

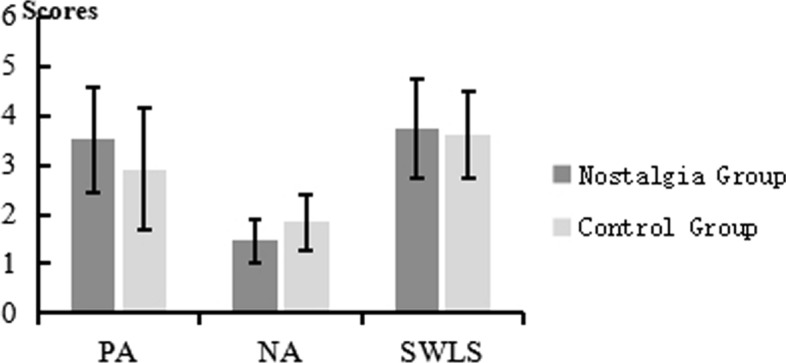

Group differences. As expected, participants in the nostalgia condition scored significantly higher on PA (Mnostalgia = 3.51, SD = 1.07 vs. Mcontrol = 2.92, SD = 1.23, F(1, 100) = 6.618, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.062) and significantly lower on NA (Mnostalgia = 1.46, SD = 0.43 vs. Mcontrol = 1.84, SD = 0.57, F(1, 100) = 14.224, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.125) than those in the control condition. However, the nostalgia and control conditions did not significantly differ on SWLS (Mnostalgia = 3.73, SD = 1.00 vs. Mcontrol = 3.60, SD = 0.87, F(1, 100) = 0.542, p = 0.463, η2 = 0.005). Thus, H1a and H1b were supported, but H1c was not. See Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The PA, NA, and SWLS in Experiment2. PA = positive affection; NA = negative affection; SWLS = satisfaction with life scale. The vertical bars represent the range of ± 1 SD. The results show significant group difference for PA and NA, but not for SWLS

Gratitude. Participants in the nostalgia condition reported significantly more gratitude than those in the control condition (Mnostalgia = 4.27, SD = 1.29 vs. Mcontrol = 3.33, SD = 1.64, F(1, 100) = 10.239, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.093). Furthermore, gratitude was positively correlated with nostalgia, r(102) = 0.64, p < 0.001, and with PA, r(102) = 0.51, p < 0.001, and nostalgia negatively correlated with the NA, r(102) = − 0.61, p < 0.001. There was no significant relationship between gratitude and SWLS, r(102) = 0.15, p = 0.127. These results indicated that gratitude qualified as a potential mediator of the nostalgia effect on PA and NA.

Gratitude as a mediator. To test whether gratitude mediated the nostalgia effect on SWB, we used the PROCESS macro in SPSS, Model 4, with 5000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, 2017; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Group assignment was the independent variable, and coded as 0 = control, 1 = nostalgia. The indirect effect of nostalgia on PA was significant: B = 0.408, SE = 0.144, 95% [0.144, 0.710]. The mediation effect explained 58% of the variance in the total effect, and the conditional direct effect was not significant, B = 0.180, SE = 0.200, 95% CI [-0.217, 0.578]. These results suggest full mediation. Thus, H3a was supported. See Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Mediation of the effect of nostalgia on positive affect by gratitude in Experiment 2. All coefficients are unstandardized. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

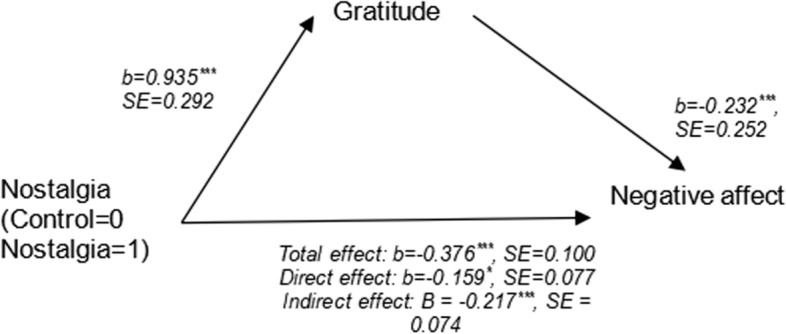

The indirect effect of gratitude in the association between nostalgia and NA was significant: B = -−0.217, SE = 0.074, 95% CI [-0.168, -0.080]. The mediation effect explained 58% of the variance in the total effect. Additionally, the conditional direct effect was significant, B = -−0.159, SE = 0.077, 95% CI [−0.312, −0.006], suggesting partial mediation. Thus, H3b was supported. As in Experiment 1, the indirect effect of nostalgia on SWLS via gratitude was not significant (B = 0.050, SE = 0.076, 95% CI [−0.083, 0.229]); thus, H3c was not supported. See Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Mediation of the effect of nostalgia on negative affect by gratitude in Experiment 2. All coefficients are unstandardized. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Experiments 1 and 2 used different paradigms to manipulate nostalgia and obtained similar results concerning the nostalgia's associations with gratitude and positive affect. That is, nostalgia was associated with higher gratitude and PA, and gratitude mediated the association between nostalgia and PA. In Experiment 2, nostalgia was also related to lower NA, and this association was also mediated by gratitude. This suggests the possibility that the manipulation in Experiment 2 (a video showing toys and other objects associated with the time period when the participants were children) was more effective than that in Experiment 1 (think of a nostalgic memory and how it makes you feel). In both experiments, there was no group difference in SWLS scores, suggesting the possibility that nostalgia is more strongly linked to the emotional than cognitive aspects of well-being.

General Discussion

As hypothesized, nostalgia was significantly correlated with the emotional dimension of subjective well-being (higher positive affect), but contrary to expectations, it was not associated with the cognitive aspect (life satisfaction), and the relationship between nostalgia and negative affect was less stable. Similar conclusions have been reached in other studies, where nostalgia increased PA but had no significant effect on NA or the effect was variable and had no statistical significance (Leunissen et al., 2021; Wildschut et al., 2006), suggesting that the state nostalgia induced in the experiments promotes well-being essentially by increasing positive affect rather than decreasing negative affect. One possible reason for this finding is that experimentally manipulated nostalgia still entails negative affect (though to a lesser extent), or it is because participants’ affects measured in a normal circumstance (without any negative incidents), which is inherently associated with lower negative affect. The buffering effect of nostalgia on negative affect might be more notable upon coping with negative incidents, for example, nostalgia helps to deal with adverse weather (Tilburg et al., 2018, 2019), resist the threat of death (Sedikides & Wildschut, 2018), reduce prejudice and offset loneliness (Polletta & Callahan, 2019). The emotional benefits may help explain why people are keen to purchase nostalgic commodities and participate in nostalgic activities, as this may increase happiness (Rao et al., 2018; Wulf et al., 2018).

We also found the result of gratitude as a mediator of the association between nostalgia and subjective well-being was mixed. Gratitude partially mediated the association between nostalgia and the emotional components of subjective well-being (higher PA in Experiment 1; higher PA and lower NA in Experiment 2). State gratitude induced by nostalgia indeed improves subjective well-being. This improvement is probably enabled by interactions between positive emotions. State gratitude, which is a positive emotion that can be induced via nostalgia priming, and this particular positive emotion can reflect on broader, more diffuse positive affect, increasing subjective well-being. The fact that gratitude partially mediated the effect of nostalgia on NA only in Experiment 2 suggests that the effect of nostalgia on negative affect may be conditioned by how it is induced, with biographical recollections being more actively recalling, so that individuals tend to recall a particular event or situation.Whereas, nostalgic videos designed to indirectly induce nostalgia through the reminder of external stimulis and are more diffuse in affects. These results suggest the need for further research on the link between nostalgia and emotion. For example, earlier research showed that nostalgia was significantly correlated with happiness, but not with sadness, whereas anticipated nostalgia (which means missing aspects of the present before they are lost in the future, for example, "Someone you love will leave someday") was significantly correlated with sadness, but not happiness (Batcho & Shikh, 2016). The mediating effect of gratitude in the relationship between nostalgia and cognitive well-being (life satisfaction) was not significant in Experiment 1 or Experiment 2. One possible reason is that in this research, experimental manipulation induced only a temporary state of nostalgia. Life satisfaction is an individual’s overall evaluation of the quality of life over a long period (Shin & Johnson, 1978), and thus it may be related more to individuals’ long-time nostalgia proneness or trait nostalgia than to a brief experience of nostalgia (state nostalgia). It is also possible that nostalgia-induced gratitude is probably a low arousal-positive emotion rather than intense, and therefore it is difficult to affect individual' satisfaction with life in the short term, or that there exist additional mediating mechanisms, such as savoring the present, a sense of hope, etc.

Previous research on subjective well-being mostly focused on the emotional aspect of subjective well-being, and there was not much investigation on the cognitive aspect. Besides, though there are many studies on nostalgia, gratitude and subjective well-being, most of these studies separate the three variables for research. There has been little research focused on the mechanisms between nostalgia and subjective well-being. We expanded on this earlier research by examining nostalgia in relation to both the emotional and cognitive aspects of subjective well-being, and by testing whether gratitude was an underlying mechanism of these links. Gratitude has received much attention from researchers in the area of positive psychology (Naito et al., 2005; Wood et al., 2008, 2010). Our results suggest that nostalgia is a potential cause of gratitude, and gratitude is a potential cause of subjective well-being. The results therefore have potential applied value, for example, in assisting older adults in sharing nostalgic memories as a way to promote more positive mood. Additionally, knowledge of the positive effects of nostalgia can also be applied to fields such as marketing, tourism and psychotherapy. Nostalgia and gratitude may be helpful to people who are isolated due to COVID-19 and may be beneficial during transitions after the pandemics.

Limitations and Future Directions

We revealed the relationships among nostalgia, gratitude and subjective well-being in two experiments, providing strong evidence for conclusions. Nevertheless, the study has limitations. First, the participants were college students, and the results need to be replicated in samples of participants with other backgrounds and ages, especially for older adults and the elderly who experience nostalgia more frequently. Second, there are thought to be many types of nostalgia, and these different types may also have different effects on subjective well-being (Li et al., 2015). For example, Stern (1992) distinguished historical and personal nostalgia, depending on whether the social experience was collective or individual and whether the experience was direct or indirect. Holak et al. (2005) divided nostalgia into four categories: personal, interpersonal, cultural, and virtual. In our study, we did not distinguish between the types of nostalgia induced, thus these types of nostalgia warrant attention. Finally, the results showed that nostalgia directly predicted more positive emotions but no higher life satisfaction, suggesting that future research should further explore the boundary condition between nostalgia and subjective well-being.

Funding

Humanity and Social Science Youth foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 22YJCZH074); Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Foundation Regular Project (Grant No. GD22CGL05); National Natural Science Fund of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 71601084 and 71971099), Foundation of Institute for Enterprise Development, Jinan University, Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2021MYZD01), The Project of “the 13th Five-Year Plan” for the Development of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Guangzhou (Grant No. GY21011), and Jinan University Management School Funding Program (Grant No. GY21011).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bin Li, Email: bingoli@jnu.edu.cn.

Aimei Li, Email: tliaim@jnu.edu.cn.

References

- Algoe SB, Gable SL, Maisel NC. It's the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 2010;17(2):217–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anglim J, Horwood S, Smillie LD, Marrero RJ, Wood JK. Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2020;146(4):279–323. doi: 10.1037/bul0000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett FS, Grimm KJ, Robins RW, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Janata P. Music-evoked nostalgia: Affect, memory, and personality. Emotion. 2010;10(3):390–403. doi: 10.1037/a0019006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batcho KI, Shikh S. Anticipatory nostalgia: Missing the present before it's gone. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;98:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer ET, Kraiss JT, Watkins P, Schotanus-Dijkstra M. Promoting gratitude as a resource for sustainable mental health: Results of a 3-armed randomized controlled trial up to 6 months follow-up. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(3):1011–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00261-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bono G, Froh J. Gratitude in school: Benefits to students and schools. In: Furlong MJ, Gilman R, Huebner ES, editors. Handbook of positive psychology in schools. London: Routledge; 2009. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cox CR, Kersten M, Routledge C, Brown EM, Van Enkevort EA. When past meets present: The relationship between website–induced nostalgia and well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2015;45(5):282–299. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: Effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(1):413–445. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00236-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos S, Merchant A, Rose GM, Lessley BJ, Teredesai AM. ‘The good old days’: An examination of nostalgia in Facebook posts. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2015;83:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2015.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. Yearning for yesterday: A sociology of nostalgia. New York: Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens LR. Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2017;39(4):193–208. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):34. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA. The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47(5):1105–1117. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.47.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(4):253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(2):276. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Crumpler CA. Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19(1):56–69. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Mccullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):377–389. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans ND, Reyes J, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Fetterman AK. Mental transportation mediates nostalgia’s psychological benefits. Cognition and Emotion. 2021;35(1):84–95. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2020.1806788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Fan J, Emmons RA, Bono G, Huebner ES, Watkins P. Measuring gratitude in youth: Assessing the psychometric properties of adult gratitude scales in children and adolescents. Psychological Aassessment. 2011;23(2):311. doi: 10.1037/a0021590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Sefick WJ, Emmons RA. Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46(2):213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AM, Gino F. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(6):946–955. doi: 10.1037/a0017935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hepper EG, Ritchie TD, Sedikides C, Wildschut T. Odyssey's end: Llay conceptions of nostalgia reflect its original Homeric meaning. Emotion. 2012;12(1):102. doi: 10.1037/a0025167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepper EG, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Robertson S, Routledge CD. Time capsule: Nostalgia shields psychological wellbeing from limited time horizons. Emotion. 2021;21(3):644–664. doi: 10.1037/emo0000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holak SL, Havlena WJ. Feelings, fantasies, and memories: An examination of the emotional components of nostalgia. Journal of Business Research. 1998;42(3):217–226. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00119-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holak S, Havlena W, Matveev A. Exploring nostalgia in Russia: Testing the index of nostalgia-proneness. European Advances in Consumer Research. 2005;7:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook MB. Nostalgia and consumption preferences: Some emerging patterns of consumer tastes. Journal of Consumer Research. 1993;20(2):245–256. doi: 10.1086/209346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook MB, Schindler RM. Echoes of the dear departed past: Some work in progress on nostalgia. Advances in Consumer Research. 1991;18(1):330–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Yang K, Yan W, Li X. How does trait gratitude relate to subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents? The mediating role of resilience and social support. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(4):1611–1622. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00286-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Kao G. “You know you’re missing out on something”: Collective nostalgia and community in Tim’s Ttwitter listening party during COVID-19. Rock Music Studies. 2021;8(1):36–52. doi: 10.1080/19401159.2020.1852772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leunissen J, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Routledge C. The hedonic character of nostalgia: An integrative data analysis. Emotion Review. 2021;13(2):139–156. doi: 10.1177/1754073920950455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., Ma, H. Y., Li, A. M., & Ling, W. Q. (2015). The trigger, research paradigm and measurement of nostalgic. Advances in Psychological Science, 23(7), 1289–1298.

- Li, B., Li, A., Wang, X., & Hou, Y. (2016). The money buffer effect in China: A higher income cannot make you much happier but might allow you to worry less. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 234. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li Bin, Wang Sijun, Cui Xinyue, Tang Zhen. Roles of Indulgence versus Restraint Culture and Ability to Savor the Moment in the Link between Income and Subjective Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(12):6995. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19126995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Zhao J, Xu Y, Xiang Y. How gratitude inhibits envy: From the perspective of positive psychology. PsyCh Journal. 2021;10(3):384–392. doi: 10.1002/pchj.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(1):112–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(2):249–266. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Kimeldorf MB, Cohen AD. An adaptation for altruism: The social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17(4):281–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00590.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Tsang JA, Emmons RA. Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(2):295–309. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant A, Latour K, Ford JB, Latour MS. How strong is the pull of the past? Measuring personal nostalgia evoked by advertising. Journal of Advertising Research. 2013;53(2):150–165. doi: 10.2501/JAR-53-2-150-165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naito T, Wangwan J, Tani M. Gratitude in university students in Japan and Thailand. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2005;36(2):247–263. doi: 10.1177/0022022104272904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. Appreciating gratitude: Can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being? Counselling Psychology Review. 2009;24(3–4):38–50. doi: 10.53841/bpscpr.2009.24.3-4.38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Krejtz I, Rusanowska M, Holas P. Within-person relationships among daily gratitude, well-being, stress, and positive experiences. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2019;20(3):883–898. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9979-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Newman DB, Thrash TM. A daily diary study of relationships between feelings of gratitude and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(4):323–332. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1198923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel E, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. On being grateful and kind: Results of two randomized controlled trials on study-related emotions and academic engagement. The Journal of Psychology. 2014;148:37–60. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.742854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal VJ, Sprott DE, Muehling DD. The influence of evoked nostalgia on consumers' responses to advertising: An exploratory study. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising. 2002;24(1):39–47. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2002.10505126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. The affective and cognitive context of self-reported measures of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research. 1993;28(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01086714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta F, Callahan J. Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. American Journal of Cultural Sociology. 2017;5(3):392–408. doi: 10.1057/s41290-017-0037-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, F., & Callahan, J. (2019). Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. In J. L. Mast & J. C. Alexander, (Eds.), Politics of Meaning/Meaning of Politics (pp. 55–73). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1007/978-3-319-95945-0_4

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Díaz R, Cavazos-Arroyo J. Fighting social isolation with nostalgia: Nostalgia as a resource for feeling connected and appreciated and instilling optimism and vitality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.740247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Zheng X, Wang YF. Revision of the positive affect and negative affect scale. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;14(3):249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rao M, Wang X, Sun H, Gai K. Subjective well-being in nostalgia: Effect and mechanism. Psychology. 2018;9(7):1720–1730. doi: 10.4236/psych.2018.97102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JA, Matsuba MK, Prkachin KM. Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(3):350–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, Arndt J, Sedikides C, Wildschut T. A blast from the past: The terror management function of nostalgia. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44(1):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, Arndt J, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Hart CM, Juhl J, Vingerhoets JJM, Schlotz W. The past makes the present meaningful: Nostalgia as an existential resource. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2011;101(3):638–652. doi: 10.1037/a0024292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Juhl J. Nostalgia as a resource for psychological health and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2013;7(11):808–818. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Juhl J, Arndt J. The power of the past: Nostalgia as a meaning-making resource. Memory. 2012;20(5):452–460. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.677452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Hepper, E. G., & Zhou, X. (2015). To nostalgize: Mixing memory with affect and desire. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 51, pp. 189–273). Cambridge: Academic Press. 10.1016/bs.aesp.2014.10.001

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T. Finding meaning in nostalgia. Review of General Psychology. 2018;22(1):48–61. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T. The motivational potency of nostalgia: The future is called yesterday. Advances in Motivation Science. 2020;7:75–111. doi: 10.1016/bs.adms.2019.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Arndt J, Routledge C. Self and affect: The case of nostalgia. In: Forgas JP, editor. Affect in social thinking and behavior: Frontiers in social psychology. Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Arndt J, Routledge C. Nostalgia: Past, present, and future. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17(5):304–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Baden D. Nostalgia: Conceptual issues and existential functions. In: Greenberg J, Koole S, Pyszczynski T, editors. Handbook of experimental existential psychology. Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Cheung WY, Routledge C, Hepper EG, Arndt J, Vail K, Zhou X, Brackstone K, Vingerhoets AJ. Nostalgia fosters self-continuity: Uncovering the mechanism (social connectedness) and consequence (eudaimonic well-being) Emotion. 2016;16(4):524–539. doi: 10.1037/emo0000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DC, Johnson DM. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 1978;5(1):475–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00352944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Gao J. Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020;21(7):2649–2668. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00196-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JR, Brown DJ, Keeping LM, Lian H. Helpful today, but not tomorrow? Feeling grateful as a predictor of daily organizational citizenship behaviors. Personnel Psychology. 2014;67(3):705–738. doi: 10.1111/peps.12051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stern BB. Historical and personal nostalgia in advertising text: The fin de siècle effect. Journal of Advertising. 1992;21(4):11–22. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1992.10673382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sztachańska J, Krejtz I, Nezlek JB. Using a gratitude intervention to improve the lives of women with breast cancer: A daily diary study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1365. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang JA. The effects of helper intention on gratitude and indebtedness. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30(3):198–204. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9031-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijke M, Leunissen JM, Wildschut T, Sedikides C. Nostalgia promotes intrinsic motivation and effort in the presence of low interactional justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2019;150:46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg WA, Bruder M, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Göritz AS. An appraisal profile of nostalgia. Emotion. 2019;19(1):21–36. doi: 10.1037/emo0000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg WA, Wildschut T, Sedikides C. Nostalgia’s place among self-relevant emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 2018;32(4):742–759. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2017.1351331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC, Emmons RA, Greaves MR, Bell J. Joy is a distinct positive emotion: Assessment of joy and relationship to gratitude and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2018;13(5):522–539. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2017.1414298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC, Woodward K, Stone T, Kolts RL. Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2003;31(5):431–451. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JD, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GY. Mapping the future of reminiscence: A conceptual guide for research and practice. Research on Aging. 2010;32:527–564. doi: 10.1177/0164027510364122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werman DS. Normal and pathological nostalgia. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 1977;25(2):387–398. doi: 10.1177/000306517702500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Arndt J, Routledge C. Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(5):975–993. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Cordaro, F. (2011). Self-regulatory interplay between negative and positive emotions: The case of loneliness and nostalgia. In I. Nyklicek, A. J. J. M. Vingerhoets & M. Zeelenberg (Eds.), Emotion regulation and well-being (pp. 67–83). New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-6953-8_5

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Maltby J. Gratitude uniquely predicts satisfaction with life: Incremental validity above the domains and facets of the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wulf T, Rieger D, Schmitt JB. Blissed by the past: Theorizing media-induced nostalgia as an audience response factor for entertainment and well-being. Poetics. 2018;69:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2018.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, Ng TK, Lam CL. Nostalgia and temporal life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2018;19(6):1749–1762. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9884-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Gao DG. Counteracting loneliness: On the restorative function of nostalgia. Psychological Science. 2008;19(10):1023–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Chen X, Vingerhoets AJ. Heartwarming memories: Nostalgia maintains physiological comfort. Emotion. 2012;12(4):678. doi: 10.1037/a0027236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Shi K, Feng C. Nostalgia: The gift that keeps on giving. Journal of Consumer Research. 2012;39(1):39–50. doi: 10.1086/662199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zygar C, Hagemeyer B, Pusch S, Schönbrodt FD. From motive dispositions to states to outcomes: An intensive experience sampling study on communal motivational dynamics in couples. European Journal of Personality. 2018;32(3):306–324. doi: 10.1002/per.2145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]