Abstract

Purpose

In general, men are less likely to seek health care than women. Infertility is a global disease that afflicts approximately 15% of reproductive age couples and the male contributes to 40% of the diagnosable cause. Remarkably, no large or multi-national population data exist regarding men’s perceptions about their infertility. The purpose of this study was to advance our knowledge about the infertile male’s social experience regarding: (1) how they feel about their infertility, (2) what motivated them to seek health care, (3) how likely are they to talk with others about their infertility, (4) their awareness of male infertility support groups, and (5) what their primary source for information is regarding male infertility? Based on the results from this study, these simple questions now have clearer definition.

Materials and Methods

An Institutional Review Board-approved, male-directed, anonymous questionnaire translated into 20 languages was made globally available through the Fertility Europe website (https://fertilityeurope.eu). Males (n=1,171) age 20–49 years were invited to complete the online survey after informed consent.

Results

Most respondents were European (86%). Of European men, <15.8% were self-motivated to seek medical help. Further, their physician was not the primary source of information regarding their infertility. While most men (59%) viewed their infertility positively, a large majority were not very likely (73%) to talk about it. Most respondents indicated a lack of awareness or absence of male infertility support groups.

Conclusions

These are the first multi-national population data revealing men’s feelings about their infertility, what motivates them to seek help and their awareness of resources for peer support and information. These findings also serve to highlight significant gaps that exist in the provision of male reproductive health care and in supportive resources for men suffering from infertility. We offer recommendations on how to address the problem(s).

Keywords: Attitiude to health; Feelings; Infertility, male; Reproductive health

INTRODUCTION

For any organism, reproduction is essential for life. For most humans, attempts to reproduce will be successful. However, for approximately 15% of reproductive age couples conception will be unsuccessful after one year of unprotected intercourse [1]. Thus, a reproductive health investigation of the couple becomes necessary and practice guidelines recommend that the initial infertility evaluation for the woman and the man be done concurrently [2].

The literature database contains many publications demonstrating that in comparison with women, men are characteristically less likely to seek routine health care unless intervention for an acute medical issue presents [3,4]. To fill that void, women make up to 80% of health care decisions for her family and her male partner [5]. In the field of Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR), it is frequently said that women provide the primary motivation for an infertility investigation including for that of her male partner. However, it is difficult to find any specific evidence in literature data to confirm or refute this assertion, and thus must be considered as anecdotal.

Inference of men taking a ‘passenger’ role in the investigation of infertility for the couple comes from one study showing that both men and women felt that fertility is a woman’s issue [6]. Further, men expressed that despite their desire to be involved in infertility discussions, they felt they didn’t have a voice. Evidence of women being the motivator of infertility investigations on behalf of the couple is reflected by recent data showing that the male infertility investigation is most frequently initiated through the reproductive gynecologist of the female partner [7]. Collectively the data suggest that men feel ‘left out’ of the infertility discussion and are potentially lacking in self-motivation to be evaluated for their infertility. These important yet unanswered questions lead to an equally if not more significant question of how do men specifically feel about their infertility?

How men feel about their infertility is surprisingly under-explored [8]. For those publications that do exist, research has focused primarily on more peripheral aspects, such as feelings about their involvement in‘MAR treatment’ [9], knowledge about fertility [10], and, importantly, a relationship between infertility and masculinity [11].

The latter topic is intertwined with men’s generalized attitudes about health care seeking [12,13], and as such one might anticipate there being a plethora of studies given the global pervasiveness of infertility and the prominent profile of the MAR industry. However, very few investigations explored infertility-associated feelings, and all were comprised of small subject sample sizes, e.g., less than 50 subjects, and with isolated demographics, e.g., single region with a country, and lack of diversity [11]. Conclusively, no publications exist in the literature database that have explored population-based, geographically, and culturally diverse populations of men regarding their feelings about their infertility.

A recent systematic review found that fertility awareness among reproductive age individuals is low to moderate and that men tended to have lower fertility awareness [10]. The investigators commented that it is “important to rethink reproductive health to be more male inclusive”. Male awareness and knowledge about infertility can come from many sources, for example, his physician, his partner’s gynecologist, social media and support groups. Having a better understanding of what if any resources men preferentially use to learn about their infertility might serve to empower and engage them collaboratively with their partner throughout their MAR journey. Surprisingly, the resources that are most preferentially used is not known.

The purpose of this investigation was to address some of the basic and significant gaps in knowledge as presented previously and to gain a more clear understanding of men's social experience as it relates to their infertility by using a brief questionnaire translated into 20 languages and made globally available to ask men: (1) how they feel about their infertility, (2) what motivated them to seek health care, (3) how likely are they to talk with others about their infertility, (4) their awareness of male infertility support groups, and (5) what their primary source for information is regarding male infertility?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Male Reproductive Health Initiative (MRHI) developed an 8-question non-interventional social questionnaire for placement on the Fertility Europe (FE) website (https://fertilityeurope.eu) to survey men suffering with male infertility from November 2020 through December 2021 (Appendix).

1. Ethics statement

The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined this study meets criteria for exemption from IRB review (ID: Study00011359; 5 November 2020). Informed consent was submitted by all subjects when they were enrolled.

2. Study population

The questionnaire (ongoing) is anonymous and voluntary, and participants can leave the survey at any time if they do not want to answer the questions or if the questions make them feel uncomfortable. English and non-English speaking males of reproductive age (≥18 y) were targeted, and vulnerable population groups were included but not specifically targeted. There are no questions that identify anyone as part of any of these populations, and we expect, although we cannot be sure, that people who identify with these groups will be included among the anonymous respondents. As this survey is placed on a FE website with global outreach, we expected and welcomed participants who speak languages besides English.

3. Access to the questionnaire

The questionnaire is posted on the FE website and its participating country patient support groups, the questionnaire was announced via patient support groups, in particular from United States (US) RESOLVE and from Latin America “Red Latinoamericana de Organizaciones de Personas Infértiles” or RedTRAscender, as well as “Concebir” and “Concebir Hombres”. The link was promoted on the following reproductive medicine professional society websites: European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), Asia-Pacific Initiative on Reproduction (ASPIRE), International Society of Andrology (ISA), Latin American Network of Assisted Reproduction (RedLARA), Sociedad Argentina de Andrologia (SAA), Sociedad Panameña de Obstetricia y Ginecología and Sociedad Española de Fertilidad, and several social media spaces including Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. Announcement of the availability and link to the questionnaire is posted on the opening page of the FE website. Clicking on the link (https://fertilityeurope.eu/male-infertility-questionnaire-participate-now/) redirects the interested English and non-English speaking male participant to (1) select their language preference from 20 European, Spanish, and Asian languages, followed by (2) an introductory page with an embedded link containing the informed consent document, and (3) concluding with the questionnaire.

4. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for the % distribution in response per question. Further, data were analyzed for differences between geographic regions and nations. Since European respondents contributed overall to the largest number and percentage of participants, European geographical regions (for definition see, e.g., Wikipedia) were subdivided into Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western regions and data further analyzed for % distribution in response to individual questions.

RESULTS

A total of 1,171 men responded to the questionnaire in a 12-month period. Of those, the following distribution data (%) for different age groups were recorded: 30–39 years (n=712; 60.8%), 40–49 years (n=280; 23.9%), 20–29 years (n=106; 9.1%), and 50–59 years (n=55; 4.7%). The remaining 1.5% (n=18) were comprised of men >60 years or <20 years of age.

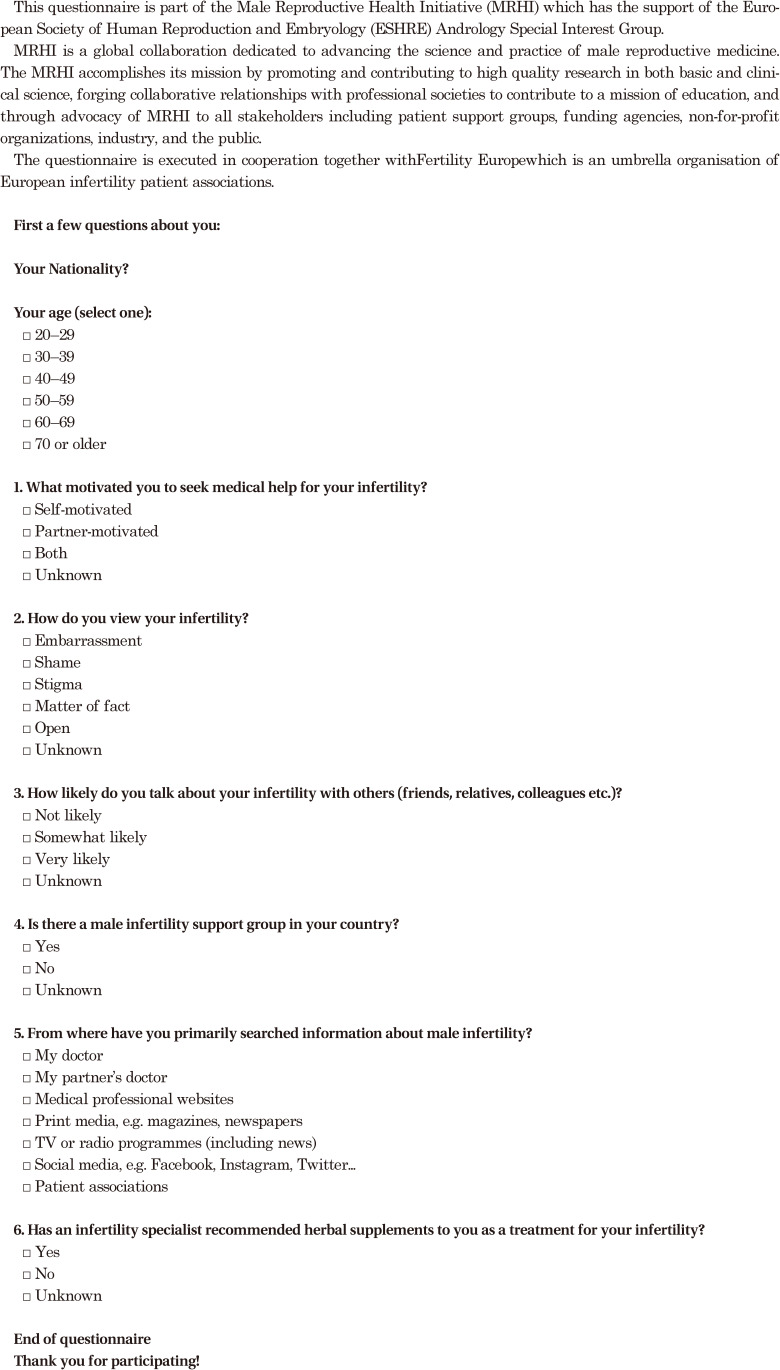

Overall, 18.9% of men independently sought medical help for infertility investigation. The male’s partner was the motivator for slightly more than 27% of men. For 52% of male respondents, infertility help seeking was pursued collaboratively with their partner.

The European region had the greatest number and percentage of respondents (n=1,001; 86%). From the graph for this region, male self-motivation was 15.8%, his partner provided 28.4% of motivation and 54.8% of participants responded that motivation for seeking medical help was collaborative. Asia had the next highest number of respondents (n=105), and there was slightly greater motivation for independent help seeking (30%) versus motivation from their partner (23%) (Fig. 1). Data analysis of respondents from the geographical subregions of Europe were similar overall in% distribution of categories except for Eastern Europe, where approximately 40% of respondents indicated it was their partner providing the motivation (data not shown).

Fig. 1. What motivated you to seek medical help for your infertility (n=1,162)?

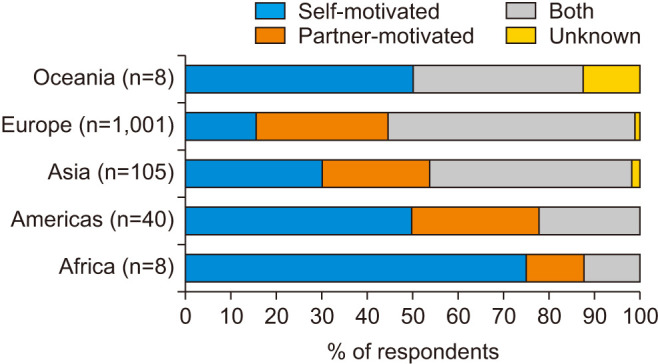

A slight majority of men (59%) expressed positivity (matter of fact, open) about their infertility regardless of global region. However, 34% of respondents felt negatively (embarrassment, shame, stigma) or conflicted (combination of positive and negative feelings) (Fig. 2). The geographical subregions of Europe largely followed similar patterns except for Northern Europe where over 50% of men felt negative or conflicted emotions about their infertility (data not shown).

Fig. 2. How do you view your infertility (n=1,160)?

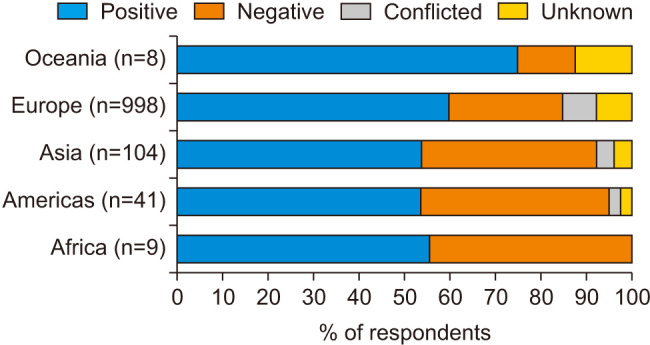

Most men (73%), regardless of global region, reflected that they were not very likely to talk about their infertility with others. In fact, 39% of men were not at all likely to talk about their infertility. Analysis of European geographical subregions (data not shown) reflected that 50% of men in the Northern and Southern regions were not likely to discuss their infertility. Whereas Western and Eastern Europe men did not express a similar reluctance (30%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. How likely do you talk about your infertility with others (n=1,164)?

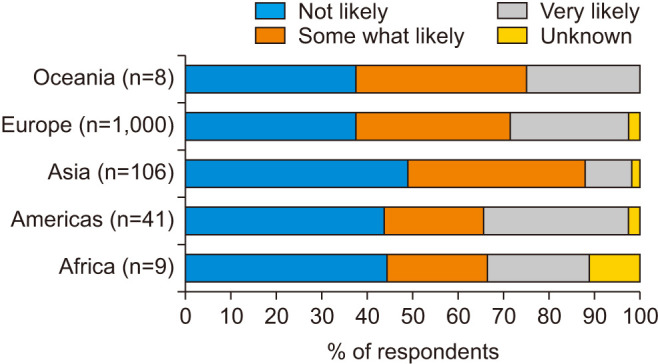

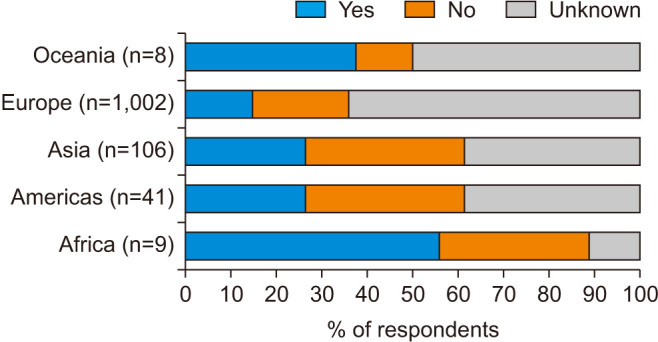

In Europe, 65% of men were unaware if an infertility support group exists where they live, 20% indicated no groups exist and only 15% acknowledged that social support is available (Fig. 4). In Asia, 26% of respondents were aware of support groups but the remainder were either unaware or indicated no such groups exist. Sub-regional analysis of Europe (data not shown) reflects more disparate results with only 10% of men in Southern and Eastern regions aware of support groups. In contrast, 35% to 40% of men in Western and Northern Europe regions are aware of male infertility support groups.

Fig. 4. Is there a male infertility support group in your country (n=1,166)?

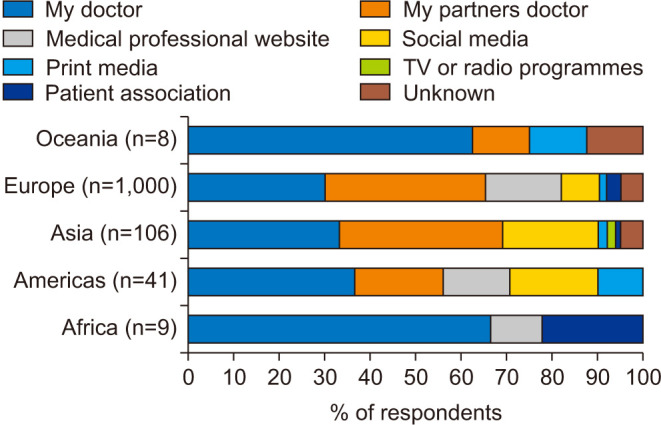

In Europe, Asia and the Americas, 31% of men responded that they receive information about male infertility from their physician. Whilst 33% of men replied that they rely upon their partner’s physician for male infertility information. For these same three global regions, internet-based resources, such as social media and medical professional websites, are used by 27% of respondents for male infertility information (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. From where have you primarily searched for information about male infertility (n=1,164)?

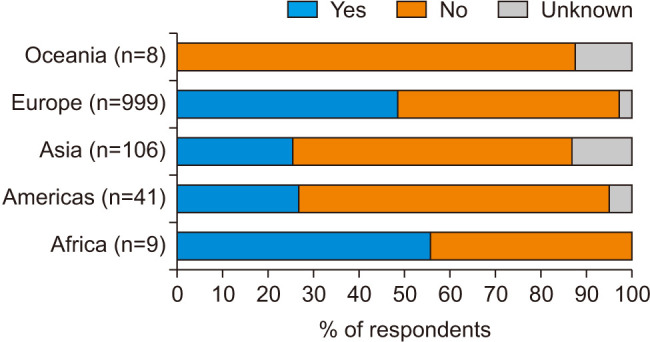

An herbal supplement had been prescribed to 45% of respondents for male infertility treatment. Examination of data (data not shown) from the geographical subregions of Europe were quite revealing in that almost 60% of men in Southern and Eastern Europe have had supplements prescribed, whereas only about 13% of men in Western and Northern Europe have received a prescription for herbal supplements (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Has an infertility specialist recommended herbal supplements to you as a treatment for your infertility (n=1,163)?

DISCUSSION

This is the first large-scale and culturally diverse study to specifically report on how men feel about their infertility. This investigation was unique from other survey studies regarding male infertility in that it relied solely upon men being interested in the subject matter to anonymously self-initiate access to the questionnaire at their leisure on the FE website. In contrast to most studies, there was no requirement to interact with an interviewer to discuss participation, to be phoned/emailed and encouraged to participate or to be subsequently contacted for their participation. It is reasonable to consider that layers of contact, communication and scheduling requirements may fall outside a comfort level for some men and contribute to participant drop-out. The simplicity in our approach resulted in over 99% of enrolled participants having completed the survey. Based on the study design and survey completion rate, we conclude there was high likelihood that the men’s responses were open and honest expressions of their feelings, and free from any coercive pressures that might otherwise impact the veracity of their responses.

How men feel about their infertility is an important issue that requires clearer understanding because how they feel may offer insight(s) into how they engage in their role(s) throughout the infertility treatment journey. Indeed, there have been few studies that looked more broadly about how men feel about infertility treatment [9] and how men view their role with their partner in the infertility and family-planning experience [6]. In general, men have described themselves as not having a voice in the process, and that, despite their desire to participate, they feel that because infertility treatment focuses on the women and her body that her voice is most important. These reflections are troubling because they impart that these men view themselves as passengers rather than equal stakeholders in the infertility process, and they may not realize their critical role and, in consequence, may lack motivation to seek infertility treatment. Reassuringly, the results from our investigation revealed that half of male respondents attributed their infertility help seeking to a collaborative effort with their partner. Perhaps not surprisingly, only a small percentage of men were self-motivated to seek help while the remainder of men were motivated solely by their partner. Do these latter findings offer any insight regarding how men feel about their infertility? In other words, do positive or negative feelings impact on self-motivation for seeking infertility care?

For health care seeking in general, men have difficulty being well-engaged participants. One explanation for men being disengaged is that they feel going to the doctor is perceived as a weakness and consequently a threat to their masculinity [3,4]. Further, men are said to be fearful of going for medical help because an underlaying and significant health issue might be revealed [3,4]. The emotions of weakness and fear may be labeled ‘negative’ whereas the opposite qualities of strength and courage as ‘positive’. In focusing on male infertility, a diagnosis of poor semen quality or poor sperm parameters might carry additional emotions of lacking in virility or feeling pitied because of their infertility [13], and these emotions might be labeled as negative. Our study revealed that slightly more than half of respondents feel open and matter of fact about their infertility, and for our study those feelings were considered as positive. This group of men reflecting emotional positivity may also be some of the same men in couples who sought infertility care collaboratively–as equal stakeholders. In stark contrast, one third of men felt negatively, with those men feeling shame, embarrassment, and even social stigma. The scale of our study brings to light the ‘reality’ that a fair percentage of men have poor feelings about their infertility. Of interest for further investigation is whether this group of men mirror those men lacking in self-motivation and/or of requiring their partner to motivate them to seek medical help for infertility. Data from European respondents reflect that the percentage of men who feel negatively about their infertility closely approximates the percentage of men whose partner motivated their visit for infertility evaluation.

A well-recognized way of sharing emotional issues is by engaging friends or family for support. Since roughly half of men had ‘positive’ feelings about their infertility, one might anticipate that a similar percentage would be likely to talk with friends or relatives about their condition. The results in our study reveal something quite contradictory. A large majority of men, almost 75%, were not likely or only somewhat likely to share about their infertility. These results of being unlikely to talk about infertility with friends or family are seemingly disjointed from the responses of feeling matter of fact and open about infertility. There are several conclusions that can be drawn (1) men feel accepting and open within themselves about infertility but are reluctant to share with family and friends for fear of ridicule or more [13], (2) men share their feelings only with their significant other or not at all [13], (3) men are not honest with themselves about their feelings, or (4) men are unaware of male-specific infertility support groups to meet with other ’like’ men to share the gamut of feelings that are a part of being a man afflicted by the disease of infertility.

To address the last question above, we asked respondents whether they were aware of any male infertility support groups in their country. In the three regions with the greatest number of responses, less than one quarter of respondents were aware that support groups were an available resource. Even more alarming, less than 15% of men in the European region were aware that a male infertility support group exists in their country. Conversely, more than 75% of infertile males who responded to the questionnaire answered that there are no support groups, or they are unaware of any male infertility support groups in their country. More concerning is that a significant percentage of men with negative and conflicted emotions do not know if there are groups for infertile peers to meet for mutual support. With no peers for support to talk with about how their disease impacts them, how might it affect their relationship and or how stress might impact on other aspects of life, e.g., workplace, or contribute to feelings of isolation and worse, depression [14,15,16]. Despite the very real potential for this desperate state, there are resources, such as medical professionals, social media and support programs, that men can be directed to use to gain information about their condition and to find supportive resources for any emotional concerns [17].

To gain an understanding for how men become informed about their infertility, men were asked what resources they primarily used. Most men indicated they received information either from their doctor or their partner’s doctor. While these are important resources for credible medical information, they limit access for consultation primarily to a scheduled appointment, which may require the man to take time away from work and potentially resulting in a loss of wages. By contrast, internet access affords greater on-demand opportunity to scope for information and resources on male infertility, that includes, for example, medical professional websites, patient support associations and social media blog groups [18]. Somewhat surprising is that men sourced medical professional websites and social media virtually equivalently. In contrast, male infertility patient associations were rarely sourced. This result falls in contrast to a report [18] that found individuals experiencing infertility-related emotional stress and negative feelings had an increased desire to connect with ‘like’ individuals who can better empathize. However, while increased stress translated into increased desire to connect, a negative outcome of unmet needs increased. This latter finding of unmet needs may be reflective of (1) inability of men to find an infertility support group that meets their needs, or (2) male infertility resources not being tailored to what men need but rather to what are perceived to be men’s needs. Social media male-only infertility blog posts offer a haven for men to have their needs met and feelings validated based on a peer-to-peer forum [19]. Finding such support groups, whether in-person or virtual, might be challenging because those resources may not be locally, regionally, or globally available, as evidenced by the responses from men in the present study. Finally, an important message for men to be made aware of is that information regarding male infertility on social media websites can be inaccurate, misleading, or even sensationalized [20]. Infertility doctors, whether the man’s own, e.g., reproductive urologist, or his partner’s, e.g., Ob/Gyn or reproductive endocrinologist, are perfectly positioned to counsel the man to be cautious and discriminating about what they search for and where because even some medical websites are lacking in information about male infertility [21,22].

The final question in our study questionnaire regarded a seemingly obtuse yet very topical issue regarding physician recommended use of herbal supplements as a treatment for male infertility. Television, print and social media are rife with non-pharmaceutical approaches to enhance fertility, and the evidence to support their use for the indication of male infertility is equivocal at best [20]. Indeed, a recently published registered clinical trial of couples undergoing infertility treatment showed that the semen quality of men taking daily folic acid and zinc supplementation had no beneficial effect on semen quality parameters or live birth rates [23]. In addition, a recently published Cochrane review [24] concluded, based on a dozen small or medium-sized randomized controlled trials, that there is low-certainty evidence that antioxidant supplementation improves live birth rates in infertile couples and that larger trials including placebo are required. Strikingly, our study revealed that 40% of men from the three regions with the greatest number of respondents indicated that their physician recommended a non-pharmaceutical supplement to treat their infertility. The global market value of fertility supplements was $1.75 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach $3.65 billion by 2030 [25]. That said, a recent review [26] provided data from a number of studies where both favorable and unclear results were presented. They concluded “…physicians should better consider the scientific evidence on effective ingredients and their doses before… prescribing these products.”

This investigation brings to light similarities and differences between men from globally diverse geographic regions about their attitudes, perceptions, and motivations regarding their infertility. The respondents reflect a variety of socioeconomic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds which are recognized barriers to access for reproductive health care [20].

Large-scale global programs, such as the World Health Organization, are well-positioned to implement policies and procedures for making male reproductive health care access and equity inclusive to pre-existing male health strategic development goals. Individual countries can adopt and expand upon the strategy for implantation in their own environment. As it currently stands, only 7 countries in the world have men’s health policies. Following the lead from these successful policies are countries such as the UK and US who have policy proposals put forth to their respective legislative bodies for the creation of national centers for men’s health, inclusive of male reproductive health.

Data presented in this study revealed that men from the same geographic region, such as Europe, have intra-regional differences in how they feel talking about their infertility. For example, infertile men from the Northern and Southern regions expressed a lesser likelihood of talking about their infertility compared with men from the Eastern and Western regions. This emotional diversity should be embraced because the attributes that contribute to a man having positive feelings can serve as supportive resource to those men who may feel differently.

While the questionnaire did not dig into the responses from men between countries per se, the collective response to the question about support groups was unanticipated and concerning. A large majority of infertile males responded that they either lack awareness about support groups or they responded that the groups don’t exist.

For more positive change to occur regarding men’s attitudes towards infertility, a starting point is to ask men what their needs are rather than them having to accept what their needs are perceived to be. For example, administering a standardized ‘quality of life’ assessment to the male prior to initiating care and then intermittently throughout treatment has the possibility to reveal changes in emotional and psychosomatic wellbeing that might reveal a man’s emotional need for professional intervention [27]. Having an established support program in the MAR setting could be very beneficial not only for the man but also his partner as they progress through treatment. In a social setting, a successful example of a men’s health and wellness support organization that started in Australia is called‘Men’s sheds’. This male-centric support group has expanded globally to the UK, Republic of Ireland, USA, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, and Greece [28]. Men’s sheds operate as local, e.g., village, town, non-profit groups where men meet for social interaction, such as to have coffee or to work on different projects together, e.g., woodworking, equipment repair. The slogan for Men’s sheds: “Men don’t talk face to face, they talk shoulder to shoulder” [28] is an excellent example of men giving and getting what they ‘need’ from a social interaction whilst sharing about their health and wellness. Hopefully the success of ‘Men’s sheds’ and others can serve as template to fill the support group void that currently exists for men suffering from infertility.

CONCLUSIONS

In closing, an overarching conclusion from this investigation is to emphasize the importance of men more openly sharing their feelings about their infertility, that by gaining knowledge about their infertility they may feel more empowered, and that by being in a more positive state of mind may help them to feel emotionally stronger and in a better supportive position with their partner as they collaboratively pursue infertility treatment.

Appendix

Male Infertility Questionnaire

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Christopher J. De Jonge is Associate Editor, Frontiers in Molecular and Cellular Reproduction. Steven A. Gellatly: no conflicts to disclose. Mónica H. Vazquez-Levin (MHVL) is Editor for Fertility & Sterility and for F&S Science, and Associate Editor for Human Reproduction. Christopher L.R. Barratt (CLRB), as an employee of the University of Dundee, serves on the Scientific Advisory board of ExSeed Health (from October 2021, financial compensation to the University of Dundee) and is a scientific consultant for Exscientia (from September 2021-Feb 2022, financial compensation to the University of Dundee). CLRB has previously received a fee from Cooper Surgical for lectures on scientific research methods outside the submitted work (2020) and Ferring for a lecture on male reproductive health (2021). CLRB is Editor for RBMO. Satu Rautakallio-Hokkanen: no conflicts to disclose.

Funding: None.

- Conceptualization: CJDJ, SRH.

- Data curation: SRH.

- Formal analysis: SRH, SAG, CJDJ.

- Funding acquisition: N/A.

- Investigation: CJDJ, SRH, CLRB, MHVL.

- Methodology: CJDJ, SRH.

- Project administration: CJDJ, SRH.

- Resources: SRH.

- Supervision: CJDJ, SRH, CLRB, MHVL.

- Validation: SRH, SAG, CJDJ.

- Visualization: SAG.

- Writing – original draft: CJDJ.

- Writing – review & editing: CJDJ, CLRB, MHVL, SAG.

Data Sharing Statement

The data analyzed for this study have been deposited in HARVARD Dataverse and are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AB5UMY.

References

- 1.Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018;62:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlegel PN, Sigman M, Collura B, De Jonge CJ, Eisenberg ML, Lamb DJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of infertility in men: AUA/ASRM guideline part I. J Urol. 2021;205:36–43. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men's health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2201–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahalik JR, Backus Dagirmanjian FR. Working men's constructions of visiting the doctor. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12:1582–1592. doi: 10.1177/1557988318777351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miner MM, Heidelbaugh J, Paulos M, Seftel AD, Jameson J, Kaplan SA. The intersection of medicine and urology: an emerging paradigm of sexual function, cardiometabolic risk, bone health, and men's health centers. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:399–415. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grace B, Shawe J, Johnson S, Stephenson J. You did not turn up… I did not realise I was invited…: understanding male attitudes towards engagement in fertility and reproductive health discussions. Hum Reprod Open. 2019;2019:hoz014. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoz014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samplaski MK, Smith JF, Lo KC, Hotaling JM, Lau S, Grober ED, et al. Reproductive endocrinologists are the gatekeepers for male infertility care in North America: results of a North American survey on the referral patterns and characteristics of men presenting to male infertility specialists for infertility investigations. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culley L, Hudson N, Lohan M. Where are all the men? The marginalization of men in social scientific research on infertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arya ST, Dibb B. The experience of infertility treatment: the male perspective. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2016;19:242–248. doi: 10.1080/14647273.2016.1222083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedro J, Brandão T, Schmidt L, Costa ME, Martins MV. What do people know about fertility? A systematic review on fertility awareness and its associated factors. Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123:71–81. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1480186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna E, Gough B. Experiencing male infertility: a review of the qualitative research literature. SAGE Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1177/2158244015610319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Jonge C, Barratt CLR. The present crisis in male reproductive health: an urgent need for a political, social, and research roadmap. Andrology. 2019;7:762–768. doi: 10.1111/andr.12673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolan A, Lomas T, Ghobara T, Hartshorne G. 'It's like taking a bit of masculinity away from you': towards a theoretical understanding of men's experiences of infertility. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39:878–892. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher JR, Hammarberg K. Psychological and social aspects of infertility in men: an overview of the evidence and implications for psychologically informed clinical care and future research. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:121–129. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dooley M, Dineen T, Sarma K, Nolan A. The psychological impact of infertility and fertility treatment on the male partner. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014;17:203–209. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.942390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baloushah S, Elsous A, Eid SA, Zaqout H, Ibrahim FM, Shawish MA. Depression among infertile men in the Gaza Strip, Palestine: the neglected aspect of fertility care. J Reprod Infertil. 2021;22:289–294. doi: 10.18502/jri.v22i4.7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warchoł-Biedermann K, Mojs E. What causes distress in males undergoing infertility work-up? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:7333–7345. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brochu F, Robins S, Miner SA, Grunberg PH, Chan P, Lo K, et al. Searching the internet for infertility information: a survey of patient needs and preferences. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e15132. doi: 10.2196/15132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanna E, Gough B. Searching for help online: an analysis of peer-to-peer posts on a male-only infertility forum. J Health Psychol. 2018;23:917–928. doi: 10.1177/1359105316644038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaila KE, Osadchiy V, Shahinyan RH, Mills JN, Eleswarapu SV. Social media sensationalism in the male infertility space: a mixed methodology analysis. World J Mens Health. 2020;38:591–598. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta A, Nangia AK, Dupree JM, Smith JF. Limitations and barriers in access to care for male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blakemore JK, Bayer AH, Smith MB, Grifo JA. Infertility influencers: an analysis of information and influence in the fertility webspace. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1371–1378. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schisterman EF, Sjaarda LA, Clemons T, Carrell DT, Perkins NJ, Johnstone E, et al. Effect of folic acid and zinc supplementation in men on semen quality and live birth among couples undergoing infertility treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:35–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18714. Erratum in: JAMA 2020;323:1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Ligny W, Smits RM, Mackenzie-Proctor R, Jordan V, Fleischer K, de Bruin JP, et al. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD007411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007411.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava A, Sumant O. Fertility supplement market by ingredient (natural and synthetic/blend of natural & synthetic), product (capsules, tablets, soft gels, powders, and liquids) and end user (men and women): global opportunity analysis and industry forecast, 2020–2030 [Internet] Portland (OR): Allied Market Research; c2021. [cited 2022 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/fertility-supplements-market-A07134 . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garolla A, Petre GC, Francini-Pesenti F, De Toni L, Vitagliano A, Di Nisio A, et al. Dietary supplements for male infertility: a critical evaluation of their composition. Nutrients. 2020;12:1472. doi: 10.3390/nu12051472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warchol-Biedermann K. The etiology of infertility affects fertility quality of life of males undergoing fertility workup and treatment. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15:1557988320982167. doi: 10.1177/1557988320982167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Men's Shed Association [Internet] Newcastle: Australian Men’s Shed Association; c2017. [cited 2022 Jun 17]. Available from: https://mensshed.org . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed for this study have been deposited in HARVARD Dataverse and are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AB5UMY.