Abstract

Uptake of COVID-19 vaccine first doses in UK care homes has been higher among residents compared to staff. We aimed to identify causes of lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake amongst care home staff within Liverpool. An anonymised online survey was distributed to all care home managers, between the 21st and the 29th January 2021. 53 % of 87 care homes responded. The overall COVID-19 vaccination rate was 52.6 % (n = 1119). Reasons, identified by care home managers for staff being unvaccinated included: concerns about lack of vaccine research (37.0 %), staff being off-site during vaccination sessions (36.5 %), pregnancy and fertility concerns (5.6 %), and allergic reactions concerns (3.2 %). Care home managers wanted to tackle vaccine hesitancy through conversations with health professionals, and provision of evidence dispelling vaccine misinformation. Vaccine hesitancy and logistical issues were the main causes for reduced vaccine uptake among care home staff. The former could be addressed by targeted training, and public health communication campaigns to build confidence and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines.

Keywords: COVID-19, Care homes, Vaccine hesitancy, UK

1. Introduction

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and up until the roll out of the COVID-19 vaccine in English care home on 8th December 2020, 20.7 % of all reported care home deaths have been due to COVID-19 [1]. The majority of these occurred in homes which had experienced a COVID-19 outbreak [2]. The Liverpool City Council (LCC) area (North West of England) had significantly more COVID-19 related deaths in its care home population (33.4 %, n = 206) compared to the English national average; a risk ratio of 1.62 (95 % 1.45–1.81, p < 0.001) [1]. At least 62 % of Liverpool care homes have experienced COVID-19 outbreaks [3]. LCC serves a population of almost half a million people, and is one of the most deprived local authorities in England, with lower than average life expectancy (for males 76 years in Liverpool and 80 years in England, for females 80 and 83 years respectively); 14.6 % of its population is over 65 [4], [5].

Care home residents have high levels of frailty and multi-morbidity [6]. They are affected by immunosenescence [7], which makes them very susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. There are three main portals of entry for SARS-CoV-2 into a care home: newly admitted or readmitted residents; staff; and visitors. Strategies to limit infections and outbreaks have included: improved infection prevention and control (IPC); testing staff, visitors and residents; isolation and zoning; limiting non-essential professional visits; and restricting indoor visiting [8]. Despite these measures, COVID-19 outbreaks have continued [1]. The COVID-19 vaccine programme brought hope to the care home staff, residents and the wider community. At the time of this study, it was thought that successful vaccination of care home staff and residents would result in less severe outbreaks with reduced morbidity and mortality. Subsequently it has been shown that vaccination in care home residents reduced COVID-19 infections, hospitalisations and deaths, but currently regular boosters are needed to maintain protective immunity [9]. In order to improve population protection, it is critical that vaccine uptake amongst care home staff and residents is optimised.

A recent systematic review has defined vaccine hesitancy as the ‘state of indecisiveness regarding a vaccination decision’[10], [11]. This is the definition that we utilise throughout this work. International surveys have shown that 28 % of the general population are COVID-19 vaccine hesitant, with the highest rates in the 25–34 age group and in females [12]. Hesitancy reasons include concerns about safety, lack of effectiveness, and the belief that vaccination is unnecessary [13]. Twenty-nine percent of health care workers are hesitant, with higher levels in young adults and females, and 41 % of those hesitant have safety concerns about the vaccine [14]. An American study of 11,460 care homes found that only 37.5 % of staff members had received a COVID-19 vaccine, compared to 77.8 % of their residents [15]. These data were based on vaccination administration data from Skilled Nursing Facilities in the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program, which is coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No qualitative data exploring motivators or hesitancy around vaccination were explored. At the time our evaluation was performed, only one study had investigated COVID-19 hesitancy levels in care home staff (in Indiana, United States of America) [16]. In this study, 36 % were reluctant, with the main barrier being concerns about side effects. Hesitancy levels were higher in female and younger members of staff. Another study of American health care workers found that there were low levels of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine [17], and that the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy included vaccine safety concerns, vaccine efficacy, workplace requirements (this could have both a positive and negative influence), and social influences [18].

On the 23rd of December 2020 the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines were offered to care home residents and staff in the 87 care homes within LCC. By the 29th of January 2021, 70.3 % of care home residents, and 39.8 % of staff had received their first vaccination (confidential data provided by LCC and Liverpool Clinical Commission Group vaccine tracker). A rapid service evaluation of the vaccination roll-out was performed to assess whether low levels of vaccine uptake in Liverpool care home staff were due to high levels of vaccine hesitancy, or other unidentified factors. The results of this evaluation directly informed immediate strategy and action plans to ensure that vaccine uptake in care home staff was as high as possible.

2. Methods

An anonymous online survey was designed by members of LCC’s public health team and piloted within the COVID-19 care homes team. It was distributed, via email, between the 21st and 29th of January 2021, to care home staff managers whose care homes (n = 87) lie within the LCC area. The care home staff managers answered the survey and provided information about the number of permanent staff employed at the home and the number of staff that had not been vaccinated. A list of possible reasons for staff remaining unvaccinated were listed and the number of staff associated with each reason was quantified by the care home managers. These reasons were based on previous research, [13] and local knowledge shared in the weekly LCC care home COVID-19 outbreak meetings. If there were further reasons not listed, respondents had the ability to add new reasons and quantify them. All listed reasons are provided in the results and Table 1 . Respondents [care home managers] were asked to describe what they had done to encourage vaccine hesitant staff to get vaccinated and what further assistance they required. All data collated from the survey were analysed descriptively. This service evaluation had no patient and public involvement.

Table 1.

Reasons for care home staff members being unvaccinated against COVID-19.

| Reported reasons for staff remaining unvaccinated | Proportion (95 % CI) of unvaccinated staff (n = 1009) | Proportion (95 % CI) of care homes with this reason present (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Hesitancy | ||

| Staff member believes that not enough research has been performed into vaccine safety | 37.0 %, (34.0–40.0) | 82.6 %, (69.6–91.6) |

| No reason provided | 9.4 %, (7.7–11.3) | 34.8 %, (22.1–49.3) |

| Staff member believes that the vaccine contains microchips | 1.9 %, (1.2–2.9) | 10.9 %, (4.1–22.5) |

| Staff member is afraid of needles | 1.5 %, (0.9–2.4) | 13.0 %, (5.5–25.2) |

| Staff member believes that the vaccine could alter their DNA | 1.4 %, (0.8–2.3) | 6.5 %, (1.7–16.7) |

| Logistical Issues | ||

| Staff member was not on site on the day of vaccination | 36.5 %, (33.5–39.5) | 52.2 %, (37.8–66.3) |

| Staff member was not offered the vaccine | 2.5 %, (1.6–3.6) | 8.7 %, (2.8–19.7) |

| Health Concerns | ||

| Staff member was pregnant, planning a family, or concerned about long term fertility impact of vaccine | 5.6 %, (4.3–7.2) | 43.5 %, (29.8–58.0) |

| Staff member has been advised by health professionals not to be vaccinated due to a history of allergic reactions | 3.2 %, (2.2–4.4) | 34.8 %, (22.1–49.3) |

| Health-related contraindications | ||

| Staff member currently COVID-19 positive | 1.1 %, (0.6–1.9) | 6.5 %, (1.7–16.7) |

3. Results

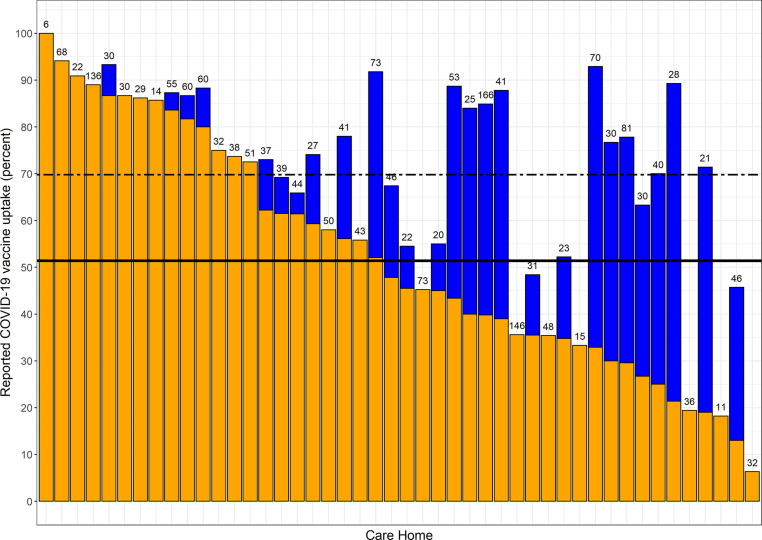

Fifty-three percent (52.8 %, n = 46) of care home managers in Liverpool responded with results available for analysis. In total, these homes employed 2128 individuals, with a median staff size of 38 (range:6–166). The overall COVID-19 first vaccination rate reported by staff was 52.6 % (n = 1119), with a mean vaccination rate per care home of 51.4 % (95 % CI 43.9–58.8 %) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Vaccination uptake rate in Liverpool care home staff. Orange columns represent the self-reported vaccine uptake rates in each home. Blue columns represent potential vaccine uptake rate if only logistically issues are resolved. The solid black line represents the mean vaccine uptake rate. The dashed black line represents the predicted mean vaccine uptake rate if logistical issues are resolved. The number above each column equals the total number of staff employed at that home. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fifty-one percent (51.2 %) of care home staff (n = 1009) were not vaccinated due to vaccine hesitancy, 39.0 % due to logistical issues, and 8.8 % due to health concerns (Table 1). The belief that not enough research had been performed into vaccine safety was present in almost all homes (82.6 %). Logistical issues impacted over half of care homes. If logistical issues were resolved, the mean vaccination rate could have increased to 69.8 % (95 % CI 63.2–76.3 %) (Fig. 1). Health concerns were widespread and were prevalent reasons for not receiving the vaccine. The following fears were reported: the vaccine affecting fertility; vaccine immunity being short-lived; one could still become sick, or die, despite being vaccinated; and concerns that vaccinations would not stop transmission.

Reported methods to address vaccine hesitancy included: one-on-one meetings to discuss concerns (34.8 % of care homes, n = 16); staff meetings (15.2 %, n = 7); provision of educational material (15.2 %, n = 7); individual discussions with general practitioners or the vaccination team (10.9 %, n = 5); managers leading by example and encouragement (6.5 %, n = 3); and reviewing employment law to see whether vaccination could be enforced (2.2 %, n = 1).

Twenty-six percent (n = 12) of care home managers did not want assistance in reducing vaccine hesitancy. The remainder would have liked: health professionals’ advice (e.g. forums, one-on-one calls, weekly meetings) (15.2 %, n = 7); information about the vaccine, including expected side effects (10.9 %, n = 5); ‘myth-busting’ material, especially about long-term fertility impact (6.5 %, n = 3); repeat visits by the vaccination team (2.2 %, n = 1); a local awareness campaign (2.2 %, n = 1); and making vaccination compulsory for care home staff (2.2 %, n = 1).

4. Discussion

Our evaluation highlights that care home managers report that vaccine hesitancy and logistical challenges are the main reasons for reduced vaccine uptake amongst care home staff in Liverpool. Conspiracy theories about vaccines were not prevalent or widespread amongst this group of staff. The reported vaccine uptake rate of 52.6 % at the date of this survey is concerning. This is comparable to COVID-19 vaccination in American care homes [15].

The social care workforce is predominately female (82 %, compared to 47 % in the economically active population), and with a higher proportion of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) individuals (21 % vs 14 % in England) [19]. This is a similar demographic to the parts of the general population with high levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [18], [20], [21], [22]. Concerns about the lack of adequate research into vaccine safety were widespread and were the most prevalent reason for non-vaccination. These mirror concerns of the general population [20], [21], [22]. Strategies to quell these specific fears need to utilise personal experience alongside expert advice, in order to be successful [23], for example sharing success stories from homes with high vaccine uptake. This could include material about vaccine development, safety profile, and the number of participants in vaccine trials [24], [25]. To reduce vaccine hesitancy for all vaccines, staff knowledge and awareness around general vaccine development and licensing process requirements could be improved through training.

The national COVID-19 vaccination roll-out has been a great success in the United Kingdom (UK), but logistical issues resulted in Liverpool’s care homes having reduced vaccine uptake. On the assumption that these issues were independent from vaccination hesitancy, then, if resolved, vaccine uptake among staff members would have increased by almost 20 %. However, in some homes there would be no discernible increase in vaccine uptake.

Health-associated concerns represented the smallest contributors to reduced vaccine uptake, with pregnancy and fertility associated concerns being widespread. Both vaccines’ safety briefs have limited information on this topic [26], [27]. The UK government advice is that those who are pregnant and are ‘at very high risk of catching the infection or those with clinical conditions that put them at high risk of suffering serious complications from COVID-19 should be vaccinated [28].’ Care home staff members would fit within this category and should be encouraged to get vaccinated following a risk assessment. The ‘history of allergies’ reason was present in around a third of homes. Vaccine-induced anaphylaxis is an extremely rare event, and care home staff should be reassured, utilising the most update information available, that this is an unlikely occurrence (1.3 cases per million doses) [29]. It is important for vaccinators to be clear with staff that “history of allergies” is not the same as “history of anaphylaxis”. Emerging data from Moderna and Pfizer suggest that their vaccines have had an anaphylaxis rate of 2.5 and 11.1 cases per million doses respectively [30], [31].

Conspiracy theories, such as believing that the vaccine contained microchips, or that they could alter the recipients DNA, were not commonplace and only mentioned in a small number of care homes. This is good news, because conspiracy theories, or controversies, are more likely to affect the attitudes of people with neutral feelings towards vaccination and make them less willing to get vaccinated [23]. Thus, the influence of such topics maybe minimal within the care home staff population. However, populations with a large proportion of individuals with neutral feelings towards vaccination should be targeted for vaccine campaigns, as they are just as likely swayed to become vaccine acceptant as vaccine hesitant [23]. This same study highlighted that vaccination campaigns can be enhanced by sharing personal experiences of the negative consequences of remaining unvaccinated [23]. Strategies should not rely solely on directly debunking false information, but encourage engagement with health professionals, and the use of publicly visible campaigns that build vaccine confidence and encourage participation through peer pressure.

5. Limitations

The survey describes self-reported vaccination uptake rates, and views were compiled by one senior member of the care home. It is possible that this may not reflect the views of all staff members. Social desirability bias may be present, however from these data we cannot ascertain the degree of this. We do not know the demographics of the care home staff population and whether any specific risk factors were associated with uptake rates or views on vaccination. This methodology was chosen, rather than surveying all care home staff members, to facilitate speed of survey responses and enable a high response rate. This was so that that LCC could quickly amend and tailor vaccine roll-out strategies and develop campaigns to counter vaccine hesitancy in this population. Parts of the city-wide vaccination campaign that were developed specifically for care home staff included: virtual question and answer sessions led by trusted clinicians from primary care practices and the Liverpool Women’s hospital, the offer of access to free taxis to and from a vaccination appointment, the offer of paid time and approved work absences to attend vaccination appointments, and the provision of information about the array of vaccination opportunities that Liverpool offered as part of its campaign [32]. We do not know how representative the views are of care home staff in Liverpool, nor the wider UK care home staff population. As not all Liverpool care homes responded to the survey, we do not know how over or under-representative vaccine uptake figures were. The reported vaccine uptake rates (52.6 %), were higher than what was provided through the National Health Service vaccine tracker to LCC (39.8 %) at the time of the survey, however it is noted that the tracker has a delay between individuals receiving the vaccine and the vaccinations being reported [33]. In comparison, the earliest English national data reported was on the 21st of February (a month after the survey) and stated that only 54.2 % of care home staff had been vaccinated [33]. It must be remembered that the focus of this survey was to ascertain key reasons for poor vaccination uptake rates rather than to explicitly quantify vaccine uptake rates. The reasons described here could assist not only in maximising vaccination rates in the UK care home staff population, but in this same population in other countries.

6. Conclusions

The public health emergency and severe consequences of COVID-19 in care homes has led to the rapid administration of vaccines within the care home resident and staff populations – which is an incredible success story. The necessary speed of roll-out has resulted in missed vaccinations due to last minute appointments, and vaccine-related fears could not always be allayed. This work has shown that most vaccine hesitancy in care home staff, as reported by care home managers, is not due to conspiracy driven theories, but due to perceived lack of adequate research into vaccine safety. These reasons could be countered by a multifaceted public health campaign, aimed at both care home staff and the wider public, to emphasise the overwhelming vaccine acceptance in the general population.

Ethics statement

These data were collected as part of routine public health service evaluation by Liverpool City Council. Fully anonymised data were provided to JT for secondary data analysis. As such, the University of Liverpool ethics department confirmed that review by the University of Liverpool research ethics committee was not needed (see https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/docs/DefiningResearchTable_Oct2017-1.pdf).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to Liverpool City Council.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all care home staff who continue to provide incredible care and support to their residents during the most difficult of times.

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics. Number of deaths in care homes notified to the Care Quality Commission, England; 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/numberofdeathsincarehomesnotifiedtothecarequalitycommissionengland (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 2.Burton J.K., Bayne G., Evans C., et al. Evolution and effects of COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: a population analysis in 189 care homes in one geographical region of the UK. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020;1:e21–e31. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30012-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green R, Tulloch JSP, Tunnah C et al. COVID-19 testing in outbreak free care homes: What are the public health benefits? J Hosp Infect 2021; S0195-6701(21)00009-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Liverpool City Council. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. Liverpool Compendium of Health Statistics. 2018. https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/9732/liverpool-compendium-of-health-statistics-2018.pdf (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 5.Public Health England. Liverpool - local authority health profile 2018. 2018. https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/1356614/phe-profile-2018.pdf (16 December 2022 date last accessed).

- 6.Gordon A.L., Franklin M., Bradshaw L., Logan P., Elliott R., Gladman J.R.F. Health status of UK care home residents: A cohort study. Age Ageing. 2014;43:97–103. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox LS, Bellantuono I, Lord JM et al. Tackling immunosenescence to improve COVID-19 outcomes and vaccine response in older adults. Lancet Healthy Longev 2020; 1: e55–e57. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Public Health England. Admission and care of residents in a care home during COVID-19. 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-admission-and-care-of-people-in-care-homes/coronavirus-covid-19-admission-and-care-of-people-in-care-homes (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 9.Shrotri M, Krutikov M, Nacer-Laidi H et al. Duration of vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalisation, and death in residents and staff of long-term care facilities in England (VIVALDI): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Heal Longev. 2022; 3: e470–e480. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bussink-Voorend D., Hautvast J.L.A., Vandeberg L., Visser O., Hulscher M.E.J.L. A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6:1634–1648. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson H.J. Defining and measuring vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6:1609–1610. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feleszko W., Lewulis P., Czarnecki A., Waszkiewicz P. Flattening the curve of COVID-19 vaccine rejection—an international overview. Vaccines. 2021;9:44. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K., Wong E.L.Y., Ho K.F., et al. Change of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine and reasons of vaccine hesitancy of working people at different waves of local epidemic in Hong Kong, China: Repeated cross-sectional surveys. Vaccines. 2021;9:62. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., et al. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021;26:2002047. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharpure R., Guo A., Bishnoi C.K., et al. Early COVID-19 First-dose vaccination coverage among residents and staff members of skilled nursing facilities participating in the pharmacy partnership for long-term care program — United States, December 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:178–182. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unroe K.T., Evans R., Weaver L., Rusyniak D., Blackburn J. Willingness of long-term care staff to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: A single state survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niznik J.D., Harrison J., White E.M., et al. Perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines among healthcare assistants: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(1):8–18. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niznik J.D., Berry S.D., Syme M., et al. Addressing hestitancy to COVID-19 vaccines in healthcare assistants. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;45:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skills for Care. The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. 2020. https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 20.Murphy J., Vallières F., Bentall R.P., et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021;12:29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman D., Loe B.S., Chadwick A., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2021:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickerson J., Lockyer B., Moss R.H., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in an ethnically diverse community : descriptive findings from the Born in Bradford study. Wellcome Open Res. 2021 doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16576.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiménez Á.V., Stubbersfield J.M., Tehrani J.J. An experimental investigation into the transmission of antivax attitudes using a fictional health controversy. Soc Sci Med. 2018;215:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca. 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 27.Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Information for Healthcare Professionals on Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-pfizer-biontech-vaccine-for-covid-19/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-pfizerbiontech-covid-19-vaccine (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 28.Public Health England. COVID-19 vaccination: a guide for women of childbearing age, pregnant or breastfeeding. 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-women-of-childbearing-age-currently-pregnant-planning-a-pregnancy-or-breastfeeding/covid-19-vaccination-a-guide-for-women-of-childbearing-age-pregnant-planning-a-pregnancy-or-breastfeeding (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

- 29.McNeil M.M., Weintraub E.S., Duffy J., et al. Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination in children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimabukuro T., Nair N. Allergic Reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. JAMA. 2021:780–781. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Allergic Reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine - United States, December 21, 2020-January 10, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70: 125–129. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7004e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Liverpool City Council Liverpool's journey through 2021. Public Health. Annu Rep. (16 December 2022, date last accessed). https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/1361423/public-health-annual-report-2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.NHS England. COVID-19 Vaccinations. 2021 https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/covid-19-vaccinations/ (16 December 2022, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to Liverpool City Council.