Abstract

The gene fnz from Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus encodes a cell surface protein that binds fibronectin (Fn). Fifty tested isolates of S. equi subspecies equi all contain DNA sequences with similarity to fnz. This work describes the cloning and sequencing of a gene, designated fne, with similarity to fnz from two S. equi subspecies equi isolates. The DNA sequences were found to be identical in the two strains, and sequence comparison of the fne and fnz genes revealed only minor differences. However, one base deletion was found in the middle of the fne gene and eight base pairs downstream of the altered reading frame there is a stop codon. An Fn-binding protein was purified from the growth medium of a subspecies equi culture. Determination of the NH2-terminal amino acid sequence and molecular mass, as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, revealed that the purified protein is the gene product of the 5′-terminal half of fne. Fn-binding activity has earlier only been found in the COOH-terminal half of FNZ. By the use of a purified recombinant protein containing the NH2 half of FNZ, we provide here evidence that this half of the protein also harbors an Fn-binding domain.

The specific role in the pathogenesis of streptococcal fibronectin (Fn)-binding cell surface proteins has not yet been elucidated, although it is assumed that these proteins enhance the potential of the bacteria to cause disease. The Fn-binding cell surface proteins SfbI/Protein F1 and M1, both from Streptococcus pyogenes, mediate the adherence to and the invasion of epithelial cells (4, 6, 12). Invasion of epithelial cells is thought to enable the spreading of bacteria into deeper tissues (8).

Streptococcus equi is usually divided into two subspecies, called subspecies zooepidemicus and subspecies equi. Subspecies zooepidemicus is part of the normal bacterial flora in horses, where it acts as an opportunistic pathogen that can cause disease in the upper respiratory tract, in the uterus, in the umbilicus, and in wounds. Subspecies zooepidemicus has also been isolated from a wide range of other mammals including humans, in whom it occasionally can cause severe disease (1). In contrast, subspecies equi is confined to horses, where it acts as an obligate pathogen causing strangles, a contagious and worldwide disease of the upper respiratory tract. Subspecies equi is thought to be a clone derived from subspecies zooepidemicus, since the former subspecies is genetically very homogeneous, whereas subspecies zooepidemicus is genetically diverse (5, 7, 10).

Many isolates of subspecies zooepidemicus bind Fn (10), and a gene, fnz, encoding a cell surface protein that binds Fn, has been cloned and sequenced from subspecies zooepidemicus strain ZV (9).

Whether subspecies equi expresses a functional FNZ protein or not is unclear. Arguments for an intact FNZ protein in this subspecies include the following: (i) subspecies equi contains DNA sequences homologous to fnz (10); (ii) Northern blots have shown that an fnz-like transcript in subspecies equi is in size and amount similar to the fnz transcript in subspecies zooepidemicus ZV (11); and (iii) the addition of FNZ protein inhibits the binding of Fn by subspecies equi (11). Surprisingly, subspecies equi does not bind the NH2-terminal 29-kDa fragment of Fn (3), which is a domain bound both by cells of subspecies zooepidemicus ZV and by purified protein FNZ (10). Furthermore, subspecies equi also binds considerably less native Fn than subspecies zooepidemicus ZV (10). These contradictory findings prompted us to clone and characterize the gene corresponding to fnz from two subspecies equi strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The streptococcal isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pUC19 was used together with Escherichia coli TG1 and XL1-Blue for cloning purposes. Streptococcal strains were grown on blood agar plates or in Todd-Hewitt broth (Oxoid, Basingstone, England) supplemented with 0.3% yeast extract (THY). The E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented in appropriate cases with 50 μg ampicillin per ml or LA plates (LB medium supplemented with 1.5% agar and 50 μg of ampicillin per ml). All incubations were at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Streptococcal strains used in this study

| Streptococcus strain | Origin (yr)a |

|---|---|

| S. equi subsp. equi | |

| Bd 3221 | Lidköping, Sweden (1989) |

| Bd 998 | Olofstorp, Sweden (1996) |

| Bd 640 | Stora Höga, Sweden (1991) |

| KLM 723 | Enköping, Sweden (1988) |

| S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | |

| Bd 871 | Sollentuna, Sweden (1989) |

| KLM 778 | Sigtuna, Sweden (1990) |

| B 168 | Uppsala, Sweden (1989) |

| Bd 440 | Västerhaninge, Sweden (1989) |

| B 262 | Ekerö, Sweden (1989) |

| KLM 201 | Uppsala, Sweden (1994) |

| K 18 | Nacka, Sweden (1991) |

| Bd 2502 | Klintehamn, Sweden (1993) |

| KLM 1030 | Bromma, Sweden (1987) |

| ZV | Sweden |

| S. dysgalactiae | |

| S2 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| Epi9 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| 8215 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| S. equisimilis | |

| 172 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| 165 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| S. pyogenes | |

| AW-43 | Lund, Sweden |

| 2-1047 | Uppsala, Sweden |

| AL-168 | Lund, Sweden |

All S. equi strains were obtained from E. Olsson Engvall or Per Jonsson, National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden. All S. dysgalactiae and S. equisimilis strains were detained from the National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden. S. pyogenes AW-43 and AL-168 were from G. Lindahl, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. S. pyogenes 2-1047 was obtained from the University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden.

Isolation of clones with fnz-like inserts.

To find useful restriction sites for cloning, Southern blots were performed as earlier described (10), using radioactively labeled probes derived from fnz. Southern blot data revealed that the restriction endonuclease SspI generates a 2.6-kb fragment, containing the fnz-like gene. SspI-digested chromosomal DNA from subspecies equi Bd 3221 and Bd 995 were separated on 1% agarose gels, and fragments of approximately 2.6 kb were cut out, purified, and ligated into pUC19. Ligated material was electrotransformed into TG1 cells that were subsequently spread on LA plates and incubated overnight. The following day, colonies were transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) filters (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel Germany) by replica plating and, after 2 h of incubation of the filters on LA plates, the colonies were lysed by chloroform vapor. After blocking the filters with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 ml NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM, Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4])–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) supplemented with casein (0.1 mg/ml), the filters were incubated overnight with human Fn (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The filters were washed and subsequently incubated with a rabbit anti-Fn antibody (diluted 1/1,000; Sigma) for 2 h. After being washed, the filters were incubated for 1 h with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (diluted 1/1,000; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Reactive colonies were visualized by using 4-chloro-1-naphtol (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). Lysates from clones displaying Fn-binding activity were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), using the Phast system (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), together with precast 8 to 25% gradient gels and SDS buffer strips. The separated proteins were transferred to an NC filter by diffusion at a temperature of 65°C. Fn-binding proteins were detected as described above. Inserts of clones subjected to SDS-PAGE were DNA sequenced using Thermo Sequenase dye terminator cycle sequencing premix kit (Amersham, Cleveland, Ohio) and the ABI Model 377XL DNA sequencer. Computer programs from the PC GENE, DNA, and protein sequence analysis software package (Intelligenetics, Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) were used to record and analyze the sequence data.

To confirm that the reading frame is changed in the fne gene from subspecies equi a fragment was PCR amplified using the primers Unna (5′-TAGAATTCTTGTGCTGGCA ACAAGC) and Lages1 (5′-TATCTAGAACCGCCGCCGATCCC), together with chromosomal DNA from the two subspecies equi strains and the subspecies zooepidemicus ZV strain. The underlined nucleotides in the respective primers correspond to complementary sequences in the fnz gene (9). The reaction mixtures were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and the major band obtained from each sample was cut out, purified, and sequenced using the primer Lages1.

Detection of secreted Fn-binding proteins.

After centrifugation, supernatants from streptococcal overnight cultures (8 ml) were sterile filtrated. The proteins in the supernatants were precipitated by adding 16 ml of acetone and, after centrifugation, the pellets were dried and resuspended in 0.5 ml of distilled water (dH2O). The samples were mixed with SDS loading buffer, boiled, and subjected to a 4 to 15% gradient SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad). After separation, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to an NC filter (Amersham). Fn-binding proteins were detected as described above. Molecular size markers (BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) were included on each gel.

Purification and amino acid sequencing of a Fn-binding protein present in the supernatant of subspecies equi.

Subspecies equi Bd 3221 was grown overnight in 700 ml of THY. After centrifugation and sterile filtration of the supernatant, the proteins in the supernatant were stepwise (50, 60, 70, 80, and 90%) precipitated with (NH4)2SO4 and resolved in dH2O. Fn-binding activity was only detected in the 60% (NH4)2SO4 fraction. By using a PD-10 column (Pharmacia Biotech) the buffer of the 60% (NH4)2SO4 fraction was changed to 50 mM lactate (pH 4.0), a change that caused precipitation. After separation of the precipitate, which displayed very low Fn-binding activity, the sample was applied on an ion exchanger (Fractogel TSK SP-650). Bound proteins were eluted with an NaCl gradient (0 to 1.5 M) and collected in 11 fractions. One fraction was found to contain the Fn-binding activity and, when separated on an SDS-PAGE gel, two equally strong bands were displayed. After confirmation that these bands had Fn-binding activity, they were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, cut out, and subjected to NH2-terminal amino acid sequencing.

Construction and purification of the NH2-terminal half of FNZ.

Construction of a clone expressing the NH2-terminal half of FNZ (amino acids 32 to 337 in Fig. 2) was done by PCR amplification using forward primer OFNZ1 (5′-ACCATGGCTAGCGCAGAGCAGCTTTATTATGGGT), reverse primer OFNZ2 (5′-ATACCCGGGATATCCTTCGGTACTACCATAGT), and chromosomal DNA from subsp. zooepidemicus ZV as the template. The underlined sequences correspond to complementary sequences in the fnz gene. The obtained fragment was cleaved with restriction endonucleases NheI and SmaI, followed by ligation into the corresponding restriction endonuclease sites in the expression vector pTYB2. This vector is part of an E. coli expression system IMPACT T7 (NEB, Inc.). The ligated DNA was electrotransformed into E. coli ER2566. Plasmids harboring inserts were isolated from transformants and verified by DNA sequencing. Production and purification of the fusion protein was done by using one verified clone, pT2fnzN, and following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, E. coli ER2566 harboring pT2fnzN was lysed by freezing and thawing and, after sterile filtration, the lysate was applied onto a chitin column. The column was extensively washed with column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X100) and subsequently treated with cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 30 mM dithiothreitol). The reducing conditions in the cleavage buffer induce an intein-mediated self-cleavage that releases the FNZ part from the column while the intein-chitin part is still bound. The eluted product, designated FNZN, was controlled on an SDS-PAGE gel.

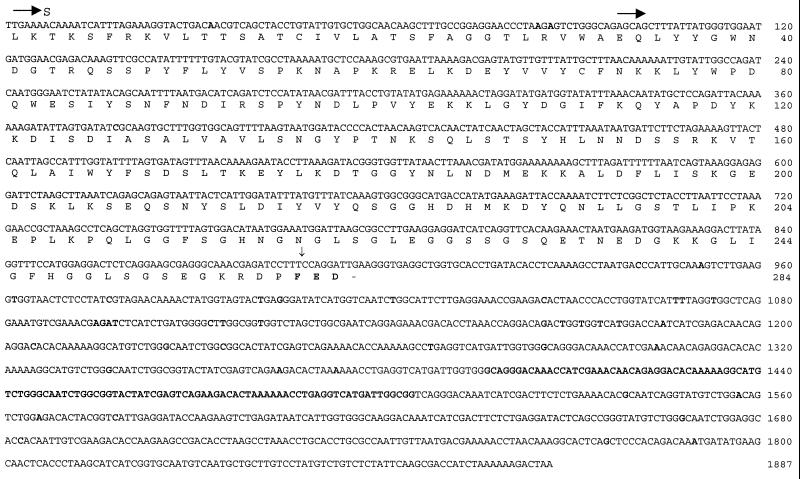

FIG. 2.

fne gene from subspecies equi. Nucleotides in boldface represent point mutations compared to the fnz gene (9). The deletion of the guanine base at position 995 causing the frameshift is represented by a vertical arrow. The altered reading frame results in three different amino acids (FED) in the COOH terminal end of FNE compared to the FNZ protein. The signal peptide (S) and the start of the mature FNE protein are indicated by horizontal arrows.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the nucleotide sequence of fne in subspecies equi is AF360373.

RESULTS

Cloning of a fnz related gene from two subspecies equi strains.

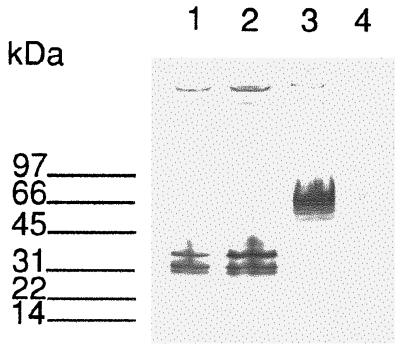

Southern blots revealed that SspI digestion of chromosomal DNA of subspecies equi Bd 3221 and Bd 998 produces a 2.6-kb fragment hybridizing to the fnz probe. Several clones expressing Fn-binding activity were isolated from partial libraries containing SspI-digested chromosomal DNA from subspecies equi strains Bd 3221 and Bd 995, respectively. Lysates from two Fn-binding clones, designated p62FNE and p79FNE, from the subspecies equi Bd 3221 and Bd 995 libraries, respectively, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and after transfer to an NC filter, the clones were tested for Fn-binding activity (Fig. 1). One clone, pSZF1000 (9), harboring the complete fnz gene from subspecies zooepidemicus ZV, expressed an Fn-binding protein with a molecular mass of 66 kDa, while both p62FNE and p79FNE expressed Fn-binding proteins with estimated molecular masses of 37, 32, and 31 kDa (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Western ligand blot analysis E. coli cells harboring the fnz gene from subspecies zooepidemicus ZV or fne from subspecies equi Bd 3221 or Bd 995 were lysed by boiling in SDS sample buffer. After separation by SDS-PAGE, the samples were transferred to an NC filter and analyzed for Fn-binding activity. Lane 1, p62FNE; lane 2, p79FNE; lane 3, pSZF1000; lane 4, pUC19. Molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons.

Sequencing of the complete genes, designated 62fne and 79fne, revealed no sequence difference between the two genes. Comparison to fnz revealed 42 point mutations (Fig. 2). The point mutations were predominantly found in the 3′-half of fne. This half of the gene was found to contain repetitive sequences similar to the repetitive R regions found in fnz (9). One 102-bp insert, encoding almost a complete repeat, was found in the corresponding repetitive R region in fne (not shown). Of the three deletions found, two were situated close to each other (positions 1203 to 1207 and 1212 to 1221), resulting in deletion of five and a change of two amino acids in the deduced amino acid sequence. Surprisingly, the third deletion consisted of one guanine base at position 995, causing a frameshift, and eight base pairs downstream of the deletion there is a TGA stop codon present that terminates translation in the altered reading frame. A fragment covering the one-base deletion was PCR amplified using chromosomal DNA from the two subspecies equi strains and subspecies zooepidemicus ZV as a template. Sequencing of the three PCR fragments confirmed that the guanine base is missing in the two subspecies equi strains but not in subspecies zooepidemicus ZV.

Subspecies equi but not subspecies zooepidemicus secretes an Fn-binding protein.

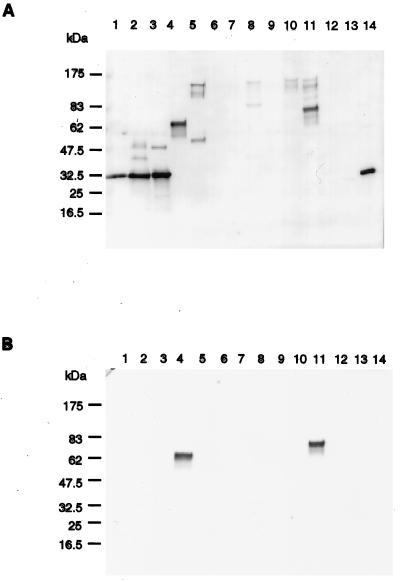

Acetone concentrated supernatants from overnight cultures of different streptococcal species were tested for Fn-binding activity (Fig. 3A). The four subspecies equi isolates used are all clinical isolates taken from horses suffering from strangles, and the isolates also fall into different pulsotypes, based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (12). An Fn-binding protein with a molecular mass of approximately 32 kDa was present in the supernatant from all four subspecies equi isolates (lanes 1, 2, 3, and 14). Detection of Fn-binding activity involved the use of an anti-Fn antibody and a peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody. An identical Western ligand blot was made but with the Fn excluded in order to determine whether the signals resulted from Fn binding or were an effect of a direct binding between the bacterial proteins and the antibodies (Fig. 3B). Comparison between the two Western ligand blots revealed that the major signal for Streptococcus equisimilis 172 (lane 4) and Streptococcus dysgalactiae Epi9 (lane 11) is due to an immunoglobulin G (IgG)-binding effect. However, Fn-binding proteins were, besides subspecies equi, found for S. equisimilis 165 (lane 5), S. pyogenes AL-168 (lane 8), S. dysgalactiae 8215 (lane 10), and S. dysgalactiae Epi9 (lane 11). No Fn-binding was seen for the two subspecies zooepidemicus strains (lanes 12 and 13), and further investigation showed that supernatants from 10 out of 10 tested subspecies zooepidemicus isolates, all containing an fnz-like gene (12), did not bind Fn or IgG in the Western ligand blot assay (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Western ligand blots. (A) Concentrated supernatants from overnight cultures of different streptococci were, after SDS-PAGE, electroblotted over to an NC filter. The filter was blocked and thereafter incubated with Fn, followed by an anti-Fn antibody, and finally a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody was added. Lanes: 1, subspecies equi Bd 3221; 2, subspecies equi Bd 998; 3, subspecies equi Bd 640; 4, S. equisimilis 172; 5, S. equisimilis 165; 6, S. pyogenes AW-43; 7, S. pyogenes 2-1047; 8, S. pyogenes AL-168; 9, S. dysgalactiae S2; 10, S. dysgalactiae 8215; 11, S. dysgalactiae Epi9; 12, subspecies zooepidemicus Bd 871; 13, subspecies zooepidemicus KLM 778; 14, subspecies equi KLM 723. (B) Same as in panel A, except that no Fn was added to the filter.

The secreted Fn-binding protein in subspecies equi is FNE.

The secreted Fn-binding protein from subspecies equi Bd 3221 was purified from an overnight culture by using (NH4)2SO4 precipitation and ion-exchange chromatography. On an SDS-PAGE gel the purified protein appeared as two major bands that were transferred to a PVDF membrane and subjected to amino acid sequencing. The sequence obtained (EQLYY) correlates to the sequence directly after the predicted signal-peptide cleavage site of protein FNE (Fig. 2).

The NH2-terminal half of FNZ binds Fn.

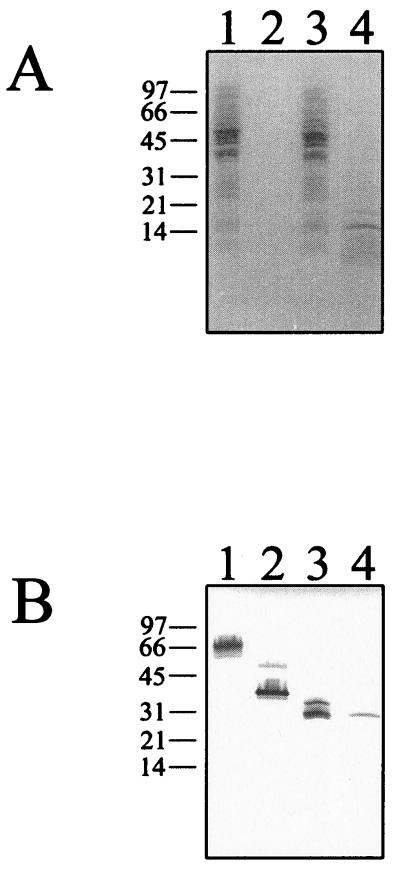

The finding that FNE binds Fn is contradictory to the earlier report that the NH2-terminal half of FNZ does not bind Fn (9). To investigate this further a recombinant protein covering the NH2-terminal half of FNZ was produced, purified, and tested for Fn-binding activity. As seen in Fig. 4 (lane 2), the NH2-terminal half of FNZ (FNZN protein) clearly has Fn-binding activity.

FIG. 4.

(A) SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, cell lysates of E. coli clone pSZF1000 (9); lane 2, purified FNZN protein from pT2fnzN; lane 3, cell lysates from E. coli clone p62FNE; lane 4, concentrated supernatant from growth medium of an overnight culture of subspecies equi Bd 3221. Molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Western ligand blot analysis. After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to an NC filter and analyzed for Fn-binding activity. Lanes are as described in panel A.

DISCUSSION

The earlier contradictory results, that subspecies equi binds considerably less Fn than subspecies zooepidemicus, although the size and amount of an fnz-like transcript is similar between the two subspecies, have now been clarified. The reading frame of fne is interrupted due to a one-base deletion present in the middle of the gene and, as a consequence, only the 5′-terminal half of fne is translated in subspecies equi. We found that the FNE protein is secreted into the growth medium, which is logically since it has a signal peptide (Fig. 2), but is lacking the COOH-terminally located sequence motifs involved in cell wall anchoring found in the FNZ protein (9). The finding that FNE binds to Fn was surprising since it was earlier reported that the Fn-binding domains in FNZ all were located in the COOH-terminal half of FNZ (9). However, this finding was mainly based on analyzing a E. coli cell lysate containing a plasmid construct (pSZF21) expressing the NH2-terminal half of FNZ which did not bind Fn. In the present study we used the corresponding DNA fragment from fnz to produce the NH2-terminal half of FNZ (FNZN expressed by pT2fnzN) and, as shown in Fig. 4, lane 2, FNZN clearly binds Fn. The reason for the lack of Fn-binding activity previously reported (9) is at present unclear, but it might be due to several reasons, e.g., a low level of expression of the fnz gene in the specific construct used.

To study the expression of secreted Fn-binding activity in subspecies zooepidemicus, 10 isolates were chosen for their cell surface-located Fn-binding capacity ranging from low binders to high binders. The reason why some subspecies zooepidemicus strains display low Fn-binding activity although they harbor an fnz-like gene is not because of a one-base deletion as in fne, since no Fn-binding activity was found in any of the growth media from overnight cultures of subspecies zooepidemicus. Several streptococcus isolates other than the four subspecies equi strains were found to secrete Fn-binding proteins. Whether these are cell surface-attached proteins that have been released during the cultivation or were actively secreted into the growth medium is not clear. Interestingly, the supernatant from a culture of subspecies zooepidemicus KLM 778 (lane 13 in Fig. 3A) displayed no Fn-binding activity, although cells from this strain have been shown to have high Fn-binding capacity (10).

In S. pyogenes, large biologically active fragments of cell surface proteins are released by a serine protease called SCP (2). One of the released fragments binds IgG and has been found to originate from protein H, an IgG-binding cell surface protein (2). Cells of S. dysgalactiae Epi9 bind IgG-efficiently (J. Vasi, personal communication), so whether the two IgG-binding proteins found in the supernatant of S. dysgalactiae Epi9 and S. equisimilis 172, respectively, are parts from cell surface proteins or directly secreted into the growth medium is not yet known.

It has been proposed that subspecies equi is a clone derived from subspecies zooepidemicus (7) and that certain evolutionary changes turned it from a commensal to a pathogen (13). The acquisition of SeM, an M-like protein present in subspecies equi but not in subspecies zooepidemicus, has been postulated to be one of these key elements (13). The finding that the 4 tested subspecies equi isolates secreted an Fn-binding protein whereas the 10 tested subspecies zooepidemicus isolates did not also reflects a distinct difference between the two subspecies. Thus, there is a possibility that the deletion of one base in fnz has also contributed to change a commensal to a pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin Lindberg for advice and critical comments.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Council for Forestry and Agricultural Research (32.0370/96 and 32.0646/97) and the Swedish Horserace Totalizator Board (ATG).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnham M, Ljunggren A, McIntyre M. Human infection with Streptococcus zooepidemicus (Lancefield group C): three case reports. Epidem Infect. 1987;98:183–190. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800061896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berge A, Björck L. Streptococcal cysteine proteinase releases biologically active fragments of streptococcal surface proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9862–9867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chhatwal G S, Blobel H. Heterogeneity of fibronectin reactivity among streptococci as revealed by binding of fibronectin fragments. Comp Immun Microbiol Infect Dis. 1987;10:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(87)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cue D, Dombek P E, Lam H, Cleary P P. Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M1 encodes multiple pathways for entry into human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4593–4601. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4593-4601.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galán J E, Timoney J F. Immunologic and genetic comparison of Streptococcus equi isolates from the United States and Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1142–1146. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.6.1142-1146.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jadoun J, Ozeri V, Burstein E, Skutelsky E, Hanski E, Sela S. Protein F1 is required for efficient entry of Streptococcus pyogenes into epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:147–158. doi: 10.1086/515589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorm L R, Love D N, Bailey G D, Bailey G M, Briscoe D A. Genetic structure of populations of β-haemolytic Lancefield group C streptococci from horses and their association with disease. Res Vet Sci. 1994;57:292–299. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaPenta D, Rubens C, Chi E, Cleary P P. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12115–12119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindmark H, Jacobsson K, Frykberg L, Guss B. Fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3993–3999. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.3993-3999.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindmark H, Jonsson P, Olsson Engvall E, Guss B. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and distribution of the genes zag and fnz in isolates of Streptococcus equi. Res Vet Sci. 1999;66:93–99. doi: 10.1053/rvsc.1998.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindmark H, Guss B. SFS, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus equi, inhibits the binding between fibronectin and collagen. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2383–2388. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2383-2388.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molinari G, Talay S R, Valentin-Weigand P, Rohde M, Chhatwal G S. The fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes SfbI, is involved in the internalization of group A streptococci by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1357–1363. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1357-1363.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timoney J F, Artiushin S C, Boschwitz J S. Comparison of the sequences and functions of Streptococcus equi M-like proteins SeM and SzPSe. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3600–3605. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3600-3605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]