Abstract

Study Design

A retrospective multicenter case series was conducted.

Purpose

This study was designed to investigate the clinical features and surgical outcomes of lower lumbar osteoporotic vertebral collapse (LL-OVC) with symptomatic stenosis based on various surgical procedures and classify them using the newly developed collapse severity criteria.

Overview of Literature

The surgical outcomes of LL-OVC with symptomatic stenosis remain unclear.

Methods

We investigated patients who underwent surgical intervention for LL-OVC (L3, L4, and/or L5) with symptomatic foraminal and/or central stenosis from eight spine centers. Only patients with a minimum follow-up duration of 1 year were included. We developed new criteria to grade vertebral collapse severity (grade 1, 0%–25%; grade 2, 25%–50%; grade 3, 50%–75%; and grade 4, 75%–100%). The clinical features and outcomes were compared based on the collapse grade and surgical procedures performed (i.e., decompression alone, posterior lateral fusion [PLF], lateral interbody fusion [LIF], posterior/transforaminal interbody fusion [PLIF/TLIF], or vertebral column resection [VCR]).

Results

In this study, 59 patients (average age, 77.4 years) were included. The average follow-up period was 24.6 months. The clinical outcome score (Japanese Orthopaedic Association score) was more favorable in the LIF and PLIF/TLIF groups than in the decompression alone, PLF, and VCR groups. The use of VCR was associated with a high rate of revision surgery (57.1%). No significant difference in clinical outcomes was observed between the collapse grades; however, grade 4 collapse was associated with a high rate of revision surgery (40.0%).

Conclusions

When treating LL-OVC, appropriate instrumented reconstruction with rigid intervertebral stability is necessary. According to our newly developed criteria, LIF may be a surgical option for any collapse grade. The use of VCR for grade 4 collapse is associated with a high rate of revision.

Keywords: Lower lumbar, Osteoporotic fracture, Stenosis

Introduction

Although osteoporotic vertebral collapse (OVC) is usually observed in the thoracolumbar region [1], its occurrence in the lower lumbar segments (below L3) is not unusual. The clinical features of lower lumbar OVC (LL-OVC) are distinct from those of thoracolumbar OVC (TL-OVC), especially in terms of neurological manifestations. While TL-OVC typically induces bladder dysfunction and/or paraparesis due to compromises of the epiconus, patients with LL-OVC present with radiculopathy caused by stenosis of the central cauda equina and/or neural foramen [2,3]. This stenosis can be due to preexisting degeneration, in addition to intervertebral/intravertebral instability or a retro-pulsed bone fragment [4]. Determining the appropriate fusion (or decompression) length and reconstruction technique is challenging during the surgical treatment of LL-OVC compared with that of TL-OVC. Due to the load-sharing biomechanics of the lower lumbar vertebral column [5], anterior reconstruction is required during surgical treatment to obtain optimal stability of the construct. In surgical decision-making, the type of anterior reconstruction procedure is usually determined by the severity of vertebral collapse. However, to date, no study has recommended surgical strategies based on vertebral collapse severity. Furthermore, clinical outcomes of various surgical procedures for LL-OVC are unclear.

Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the clinical features of LL-OVC according to newly developed simple criteria for assessing collapse severity and compare surgical outcomes between various surgical procedures in a large multi-institutional case series. We hypothesized that recent advances related to lumbar interbody cages, including lateral cages, may facilitate rigid anterior column reconstruction by resolving footprint mismatch derived from collapsed endplates, thus leading to better clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient population and data collection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyoto University (IRB approval no., R2091). The requirement for informed consent from individual patients was omitted because of the retrospective design of this study. We retrospectively reviewed patients who underwent surgical intervention for OVC at the L3, L4, or L5 levels at eight major spine referral centers between January 2007 and January 2019. In total, 146 patients with concomitant stenosis diagnosed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were identified; among them, those who had a minimum of 1 year of follow-up were enrolled in this study (n=87). The exclusion criteria were applied to these 87 patients. Specifically, patients were excluded if (1) they previously underwent lumbar spine surgery, (2) they did not have radiculopathy symptoms (only back pain), (3) their preoperative and postoperative radiographic evaluations were unavailable, or (4) they underwent vertebroplasty/balloon kyphoplasty alone. Consequently, 59 patients were included in this analysis.

Baseline demographics, including age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, perioperative osteoporosis treatment, collapsed vertebral level, number of collapsed vertebrae, and interval from onset to surgery, were investigated.

2. Surgical procedures performed and clinical outcome evaluation

Surgical indication was determined based on the surgeon’s discretion in each institution; essentially, patients who were intolerable despite more than approximately 3 months of conservative treatment were indicated for surgery. Moreover, the type of surgical procedure was chosen based on the surgeon’s preference; the severity of collapse, intervertebral/intravertebral instability, presence of an intravertebral cleft, and stenosis type (central or foraminal stenosis) were considered in surgical decision-making. In this study, the surgical procedures performed were classified as follows: decompression alone, posterolateral fusion (PLF), posterior/transforaminal interbody fusion (PLIF/TLIF [PTLIF]), lateral interbody fusion (LIF), and vertebral column resection (VCR). If an intravertebral cleft was identified, vertebroplasty was performed using polymethylmethacrylate or hydroxyapatite. Variable augmentation techniques (sublaminar polyethylene cable and/or spinous process plate fixation) were used at the discretion of the surgeon. Clinical outcomes were evaluated using the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score for degenerative lumbar diseases (maximum score=29), which includes subjective symptoms and objective clinical signs [6]. The JOA score was calculated preoperatively and at the final follow-up (minimum of 1 year). If a patient underwent revision surgery, the reason for the revision was investigated.

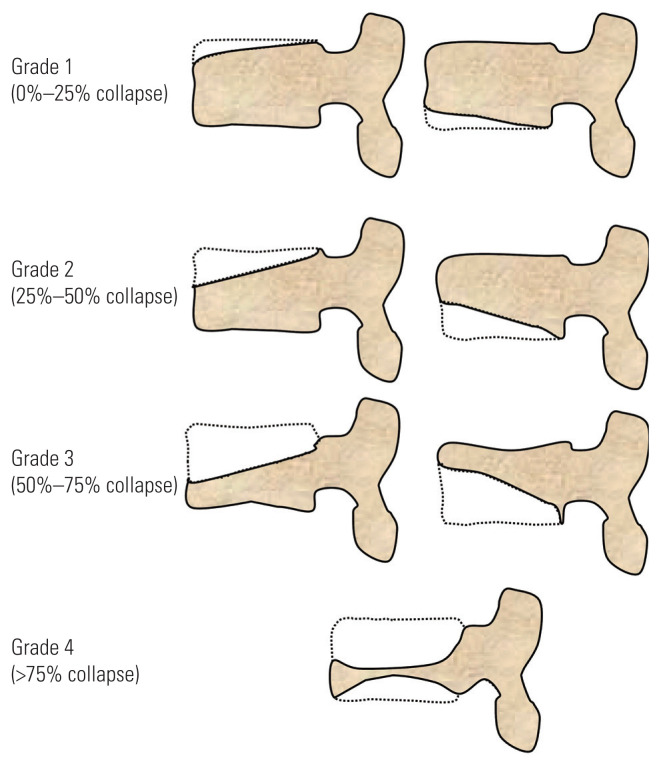

3. Radiographic assessment

For this analysis, we defined the new criteria for determining collapse severity by modifying the Genant semi-quantitative grading scheme, which is based on the visual assessment of plain lateral radiographs (Fig. 1) [7]. These are simplified easy-to-use criteria that aid surgical decision-making: grade 1: most collapsed height with 0%–25% of normal vertebral height (referenced with unfractured vertebra), regardless of endplate orientation (superior or inferior); grade 2: most collapsed height with 25%–50% of normal vertebral height; grade 3: most collapsed height with 50%–75% of normal vertebral height; and grade 4: most collapsed height with 75%–100% of normal vertebral height.

Fig. 1.

Grading of vertebral collapse severity (grades 1–4). Dot lines indicates original vertebra.

The Cobb method was used to measure the local kyphosis angle (LKA) between the upper endplate of a proximal adjacent vertebra and the lower endplate of a distal adjacent vertebra of a collapsed vertebra on plain lateral radiographs. The LKA was measured preoperatively, immediately postoperatively, and at the final follow-up. The presence of an intravertebral cleft was evaluated using a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan. Intervertebral/intravertebral instability was assessed using a preoperative lateral flexion–extension radiograph. The presence of instability was defined as more than 10° kyphotic change of the disk angle and/or more than 4 mm of vertebral translation [8]. Concomitant stenosis was evaluated using preoperative MRI. The stenosis type was classified as central, foraminal, or both. The presence of foraminal stenosis was diagnosed using the MRI grading system for foraminal stenosis developed by Lee et al. [9]. The relationship between the stenosis type and collapse grade was assessed. Fusion status was evaluated using a CT scan obtained at the final follow-up. Solid fusion was defined as a continuous trabecular bone in the instrumented posterior column and/or anterior column.

4. Comparison of clinical outcomes based on differences in surgical procedures and collapse severity

Clinical and radiographic outcomes (JOA score, LKA, fusion rate, and revision surgery) were compared based on the surgical procedure chosen. Moreover, these outcomes were compared to the preoperative collapse severity (grades 1–4).

5. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as means±standard deviations, unless otherwise specified. The analysis of variance was used for inter-group analyses. Fischer’s exact test was used for categorical variables. The paired t-test was used to compare preoperative and postoperative data. JMP ver. 13.0 (Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses. Results were considered statistically significant if p-values are less than 0.05.

Results

The patient demographics are shown in Table 1. Most patients (81.3%) were female, and the mean age of the patients was 77.4±5.4 years. More than 57.6% of the patients received osteoporotic treatment perioperatively (bisphosphonate, teriparatide, or denosumab). OVC was most commonly observed in the L4 level (47.4%), followed by L3 (44.0%) and L5 (25.4%). Multiple (two or three) collapsed vertebrae were observed in 16.9% of the patients. Grade 2 was the most commonly (40.6%) observed collapse severity category. An intervertebral cleft was identified on the preoperative CT image of 32.2% of the patients. Preoperative MRI showed that most patients (64.4%) had both central and foraminal stenoses at the collapsed vertebral level.

Table 1.

Patient demographics (N=59)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 77.4±5.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 48 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.2±3.7 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Steroid use | 9 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 |

| Parkinson disease | 3 |

| Osteoporosis treatment | |

| Bisphosphonate | 9 (15.2) |

| Teriparatide | 23 (38.9) |

| Denosumab | 2 (3.3) |

| Collapse level | |

| L3 | 26 (44.0) |

| L4 | 28 (47.4) |

| L5 | 15 (25.4) |

| No. of collapsed vertebrae | |

| 1 | 49 (83.0) |

| 2 | 9 (15.2) |

| 3 | 1 (1.6) |

| Interval from onset to operation (mo) | 11.6±16.3 |

| Preoperative JOA score | 10.4±5.4 |

| Follow-up duration (mo) | 24.6±17.9 |

| Collapse severity grade (1–4) | |

| Grade 1 | 13 (22.0) |

| Grade 2 | 24 (40.6) |

| Grade 3 | 12 (20.3) |

| Grade 4 | 10 (16.9) |

| Intravertebral cleft | |

| (+) | 19 (32.2) |

| (−) | 40 (67.7) |

| Concomitant stenosis on MRI | |

| Central | 16 (27.1) |

| Foraminal | 5 (8.4) |

| Central+foraminal | 38 (64.4) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation, number, or number (%).

JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

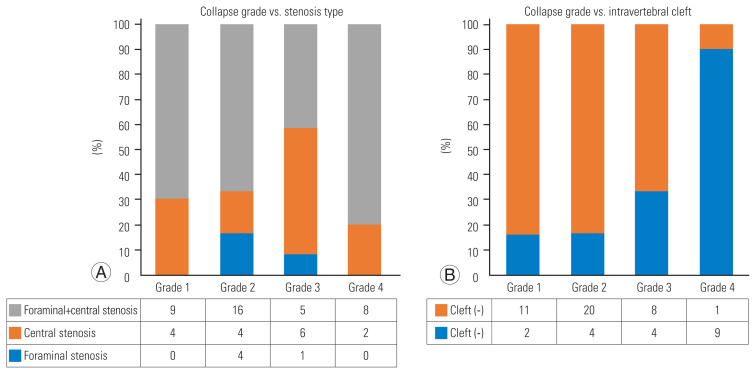

1. Relationship between collapse grade and stenosis type/intervertebral cleft

No significant association was observed between collapse grade and stenosis type; foraminal and central stenoses could be observed in any grade of collapse severity (Fig. 2A). The frequency with which intervertebral clefts were identified increased as the collapse severity grade increased; intervertebral clefts were identified in 90% (9/10) of the grade 4 cases, and this association was statistically significant (p<0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between collapse grade and stenosis type (A) & intravertebral cleft (B).

2. Surgical approach/collapse grade and outcome

The surgical approaches and clinical outcomes are compared in Table 2. Decompression alone tended to be chosen for lower collapse severity grades (1 and 2), whereas VCR was frequently performed for higher collapse severity grades (3 and 4). Interbody fusions (PTLIF and LIF) were preferred in grades 2 and 3. Significant improvement in the JOA score was achieved in all procedures (postoperative average JOA score: 18.3–24.5). Postoperative JOA scores were significantly higher in the PTLIF and LIF groups than those in other groups. Local kyphosis correction was relatively well-maintained in the PTLIF and LIF groups at the final follow-up (final LKA: −2.7° and −2.3°, respectively), whereas a significant correction loss was observed in the VCR group (final LKA=8.5°). The fusion rate was 100.0% in the LIF group, which was significantly higher than that in other groups (p<0.001). The revision rate was significantly higher in the VCR group (57.1%) than that in other groups (p=0.013).

Table 2.

Surgical approach and outcomes

| Variable | Surgical approach | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decompression (n=14) | PLF (n=10) | PTLIF (n=16) | LIF (n=12) | VCR (n=7) | ||

| Collapse grade | 0.095 | |||||

| Grade 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade 2 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 1 | |

| Grade 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Grade 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| JOA score (max=29) | ||||||

| Preoperative | 9.6±3.9 | 8.0±5.2 | 10.6±6.0 | 13.5±6.5 | 9.5±3.5 | 0.166 |

| Final FU | 18.3±7.2a) | 18.6±6.1a) | 23.0±3.3a) | 24.5±3.6a) | 20.1±4.7a) | 0.014* |

| Local kyphosis angle (°)b) | ||||||

| Preoperative | 0.2±9.5 | 1.2±13.0 | −0.1±13.6 | −0.6±10.2 | 12.1±8.8 | 0.154 |

| Immediate postoperative | −0.4±9.2 | −4.5±11.4a) | −5.9±12.6a) | −4.0±9.8a) | 2.5±3.0a) | 0.357 |

| Final FU | 1.7±8.5 | 0.2±11.5 | −2.7±11.6 | −2.3±10.4 | 8.5±10.6 | 0.174 |

| Fusion length (no. of vertebrae fused) | 2.5±2.2 | 2.2±0.6 | 2.4±1.2 | 1.9±0.9 | 4.0±2.8 | 0.083 |

| Intervertebral instability (+) | 6/14 (42.8) | 10/10 (100.0) | 15/16 (93.7) | 11/12 (91.6) | 6/7 (81.3) | 0.001* |

| Fusion rate | - | 0/100 (0) | 9/16 (56.2) | 12/12 (100.0) | 2/7 (28.5) | <0.001* |

| FU duration (mo) | 21.5±15.6 | 17.3±4.7 | 31.8±23.9 | 20.3±13.5 | 32.1±20.8 | 0.156 |

| Revision surgery | 2 (14.2) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (6.25) | 0 | 4 (57.1) | 0.013* |

| Surgical site infection | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| Adjacent vertebra fracture | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | |

| Post-decompression instability (required fusion) | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Rod breakage | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Pedicle screw loosening | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

Values are presented as number, mean±standard deviation, or number (%).

PLF, posterior lateral fusion; PTLIF, posterior/transforaminal interbody fusion; LIF, lateral interbody fusion; VCR, vertebral column resection; JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association; FU, follow-up.

p<0.05.

Indicates p-value <0.01 compared with preoperative data.

Negative value indicates lordosis.

When the clinical outcomes were compared according to the collapse grades, no difference in either the postoperative JOA scores or the LKA was observed between the different grades (Table 3); however, the revision rate was considerably higher for the grade 4 group (40.0%) than that for other groups, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.066). The causes of revision surgeries for patients with grade 4 collapses were adjacent vertebral fracture (n=2), rod breakage (n=1), and surgical site infection (n=1).

Table 3.

Collapse grades and outcomes

| Variable | Collapse grade | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (n=13) | Grade 2 (n=24) | Grade 3 (n=12) | Grade 4 (n=10) | ||

| Surgical approach | 0.124 | ||||

| Decompression | 5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | |

| PLF | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| PTLIF | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | |

| LIF | 0 | 7 | 4 | 1 | |

| VCR | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| JOA score (max=29) | |||||

| Preoperative | 6.9±5.6 | 12.6±5.1 | 11.8±5.2 | 7.9±2.8 | <0.01* |

| Final FU | 17.8±6.1a) | 22.4±5.9a) | 22.1±4.8a) | 21.1±3.9a) | 0.107 |

| Local kyphosis angle (°)b) | |||||

| Preoperative | −0.2±8.4 | −2.1±11.9 | 5.3±12.4 | 8.0±11.6 | 0.065 |

| Immediate postoperative | −3.3±8.1a) | −4.9±11.3a) | −0.1±10.0a) | −1.4±11.6a) | 0.574 |

| Final FU | −0.5±6.6 | −2.5±11.6 | 2.9±9.7 | 4.7±13.3 | 0.251 |

| Fusion length (no. of vertebrae fused) | 1.9±0.7 | 2.5±1.6 | 2.6±2.4 | 2.7±1.2 | 0.596 |

| Intervertebral instability (+) | 8/13 (61.5) | 20/24 (83.3) | 10/12 (83.3) | 10/10 (100.0) | 0.128 |

| Fusion rate | 3/8 (37.5) | 10/18 (55.5) | 6/10 (60.0) | 4/9 (44.4) | 0.571 |

| FU duration (mo) | 25.3±21.9 | 21.2±12.2 | 30.8±23.1 | 24.3±17.9 | 0.527 |

| Revision surgery | 1 (7.6) | 4 (16.6) | 0 | 4 (40.0) | 0.066 |

| Surgical site infection | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Adjacent vertebra fracture | - | 1 | - | 2 | |

| Post-decompression instability (required fusion) | - | 1 | - | - | |

| Rod breakage | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Pedicle screw loosening | - | 1 | - | - | |

Values are presented as number, mean±standard deviation, or number (%).

PLF, posterior lateral fusion; PTLIF, posterior/transforaminal interbody fusion; LIF, lateral interbody fusion; VCR, vertebral column resection; JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association; FU, follow-up.

p<0.05.

Indicates p-value <0.01 compared with preoperative data.

Negative value indicates lordosis.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of LL-OVC with symptomatic stenosis can be challenging and is associated with a high revision rate [10–13]. Moreover, it involves working with more fragile bone, foraminal decompression, and a technically demanding anterior reconstruction procedure compared with that of the more common TL-OVC. Significantly, however, the literature included only vague treatment recommendations for LL-OVC. In this study, we sought to develop easy-to-use criteria for vertebral collapse severity and create a surgical strategy using these criteria. Here, we described our surgical suggestion according to the newly developed vertebral collapse severity grades.

1. Grade 1 collapse

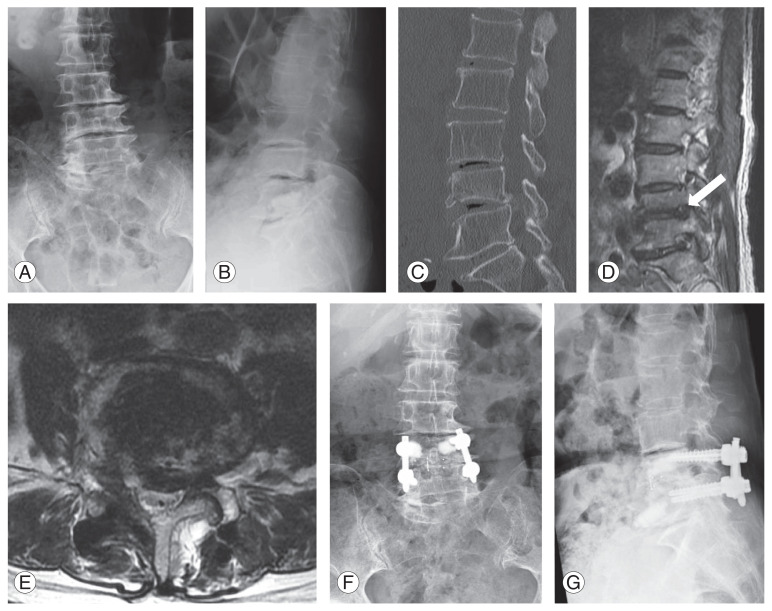

Grade 1 collapse is a mild compression fracture of either the superior or inferior endplate. Patients with grade 1 collapse exhibit both foraminal and central stenoses (Fig. 2). This central stenosis was most likely due to a preexisting degenerative condition, whereas foraminal stenosis may have been caused by a collapsed intervertebral disk and/or instability (spondylolisthesis). The presence of an intravertebral cleft is relatively rare, indicating that vertebroplasty would not be required for this patient group. For cases without intervertebral instability and an intravertebral cleft, decompression alone would be indicated. Otherwise, single-level instrumented fusion (PLIF or TLIF) should be the standard procedure for this subset of patients (Fig. 3). As footprint mismatch can occur between the collapsed endplate and PLIF/TLIF cage surface, Yamashita et al. [14] have reported a useful technique where a local bone tip is used to fill this gap. This method can reliably augment the stability of the anterior column and may facilitate the fusion process. Although not used in this series, using a large lateral interbody cage (LIF) is also a surgical option for cases of grade 1 collapse with instability.

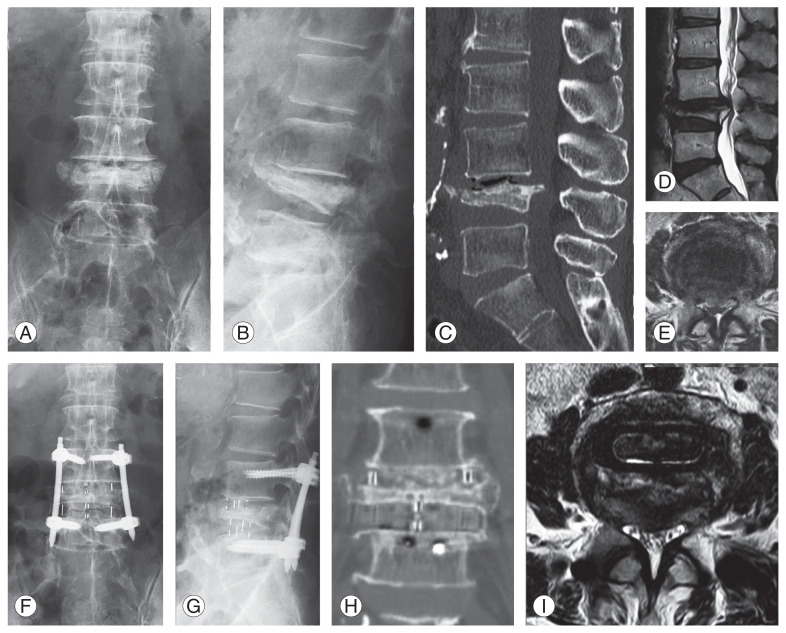

Fig. 3.

Case example for grade 1 collapse. (A, B) Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph demonstrating grade 1 collapse at L4. (C) Preoperative sagittal computed tomography image showing inferior endplate compression fracture at L4. (D) Preoperative parasagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing foraminal stenosis (white arrow). (E) Preoperative axial MRI showing central stenosis at L4–5. (F, G) Postoperative radiographs at 28 months after PLIF at L4–5.

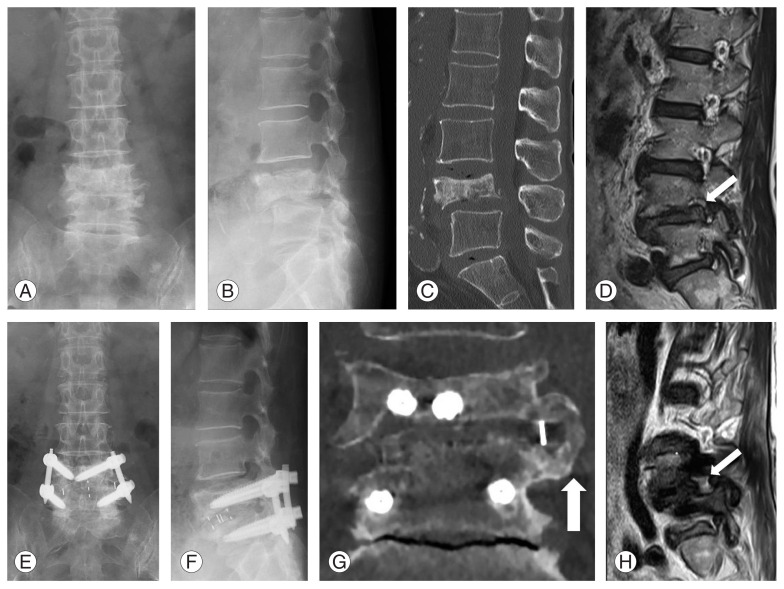

2. Grade 2 collapse

Grade 2 collapse is a moderate vertebral collapse with fracture of either the superior or inferior endplate. Patients with grade 2 collapse typically present with both central and foraminal stenoses (Fig. 2), although foraminal stenosis alone can also occur, especially if the posterior inferior wall collapse is profound. Despite the absence of an intravertebral cleft, intervertebral instability exists in most cases due to a diffusely collapsed endplate and disk injury. Thus, single-level interbody fusion is required for this group. We suggest using a large lateral cage for grade 2 collapse rather than TLIF or PLIF as footprint mismatch is more prominent in this group than in the grade 1 group and because a lateral cage can stabilize the intervertebral space with its large footprint. Furthermore, support at the bilateral cortical rim of the vertebra may contribute to rigid stabilization (Fig. 4). In patients who underwent LIF in this study, posterior decompression was never required (only LIF with supplemental percutaneous pedicle screws), probably due to the indirect decompressive effect of the lateral cage and the resolution of instability-related symptoms. The fusion rate was 100% at the final follow-up in patients who underwent LIF, which was considerably higher than that in patients who underwent TLIF/PLIF. Furthermore, loss of correction of local kyphosis was minimal in patients who underwent LIF. Using expandable TLIF/PLIF cages that minimize footprint mismatch may be a more favorable option than using conventional bullet or kidney-type cages [15].

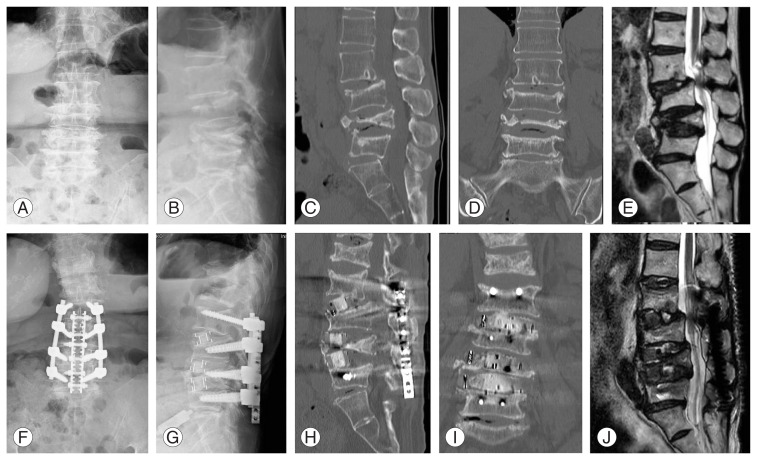

Fig. 4.

Case example for grade 2 collapse. (A, B) Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph demonstrating grade 2 collapse at L4. (C) Preoperative sagittal computed tomography (CT) image showing inferior endplate collapse at L4. (D) Preoperative sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing foraminal stenosis (white arrow). (E, F) Postoperative radiographs at 24 months after LIF. (G) Postoperative coronal CT image showing bony fusion 24 months postoperatively (white arrow). (H) Postoperative parasagittal MRI shows indirectly decompressed neural foramen (white arrow).

3. Grade 3 collapse

Grade 3 is a severe vertebral collapse that can involve both superior and inferior endplate fractures. Central stenosis due to retro-pulsed bone fragment is commonly observed in grade 3 collapse cases and can co-occur with foraminal stenosis. As indicated for grade 2, a large lateral cage of the appropriate height (over 14 mm in this study) can be used to treat grade 3 collapse. In most cases, two-level interbody fusion is necessary as pedicle screws cannot be placed in severely collapsed vertebrae; pedicle fracture can also occur. If rigid fixation is achieved, posterior decompression may not be necessary for this patient group as the bony fragment is remodeled over time with the progression of intervertebral arthrodesis (Fig. 5). An intravertebral cleft is frequently observed in grade 3 collapse; therefore, vertebroplasty using polymethylmethacrylate cement or hydroxyapatite could augment the stabilization of the construct. Moreover, the supplemental use of a spinous process plate and/or sublaminar cable could decrease screw-loosening and backout [16].

Fig. 5.

Case example for grade 3 collapse. (A, B) Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph demonstrating grade 3 collapse at L4. (C) Preoperative sagittal computed tomography (CT) image showing severely collapsed superior endplate at L4. (D, E) Preoperative sagittal and axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing severe central stenosis due to retropulsed bony fragment. (F, G) Postoperative radiographs at 24 months after two-level LIF. (H) Postoperative coronal CT image showing bony fusion 24 months postoperatively. (I) Postoperative axial MRI showing indirectly decompressed central canal.

4. Grade 4 collapse

Grade 4 is the most severe type of vertebral collapse and involves both superior and inferior endplate fracture. Surgical treatment for grade 4 collapse is the most challenging of all grades and is associated with a high rate of revision surgery. We believe that the key for successfully treating this type of collapse is the anterior reconstruction procedure. Surgeons tend to choose VCR for grade 4 collapse as the residual bone bed of the collapsed vertebra must be replaced with a strut implant. Reports have shown that VCR can be a useful surgical option in treating various pathologies [17]. However, this procedure is associated with an average estimated blood loss of more than 2,000 mL and a high rate of major perioperative complications [13,17]. In this study, the revision rate was significantly high (40.0%) for patients with grade 4 collapse. The reasons for the revision surgeries included an adjacent vertebral fracture, rod breakage, and surgical site infection; these complications were mainly mechanical failures likely caused by severe preoperative kyphotic alignment, poor bone quality, and insufficient anterior construct stability. Possible treatment solutions for grade 4 collapse might be the perioperative use of teriparatide to improve the bone quality [18] and/or a large lateral cage that uses the residual bone bed of the collapsed vertebra (even though it is minimal) in a minimally invasive fashion. Even with grade 4 collapses, cortical rims often remain and can be used as a support for a lateral cage (Fig. 6). Furthermore, using an autograft/allograft in the middle of the vertebra would help stabilize the cages inserted into the intervertebral space. Furthermore, the VCR constructs in this series required relatively long fusion levels (average level, 4.0; typically, two above and two below). Moreover, this may contribute to the incidence of instrumentation failure. The fusion length could be decreased (one above and one below) using lateral cages.

Fig. 6.

Case example for grade 4 collapse. (A, B) Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph demonstrating grade 4 collapse at L4, and concomitant grade 1 and 2 collapses at L3 and L5, respectively. (C, D) Preoperative sagittal and coronal computed tomography (CT) images showing severe superior and inferior endplates collapse at L4 with the cortical rim remaining. (E) Preoperative sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing central stenosis at L3–4 and L2–3. (F, G) Postoperative radiographs at 12 months after 3-level lateral interbody fusion with a supplemental spinous process plate. (H, I) Postoperative sagittal and coronal CT images showing adjacent vertebral fracture at L1 with the fusion construct well-maintained (postoperative Japanese Orthopaedic Association score 21 with no instrumentation failure). (J) immediately postoperative sagittal MRI showing indirectly decompressed central canal.

5. Overall consideration

Except for cases of grade 1 collapse without intravertebral and intervertebral instability, decompression alone is not indicated for OVC. In any collapse grade, obtaining adequate anterior column stability is a key factor for successful outcome. We recommend performing LIF with an effective use of the remaining residual bone bed and augmenting the defect with the available bone graft to minimize footprint mismatch. However, cage subsidence can occur with LIF if the patient’s bone quality is poor [19], particularly during the acute or subacute fracture phase (less than 3 months after onset), as fracture consolidation may be insufficient with a high risk of cage subsidence. Therefore, we suggest delaying surgery, if possible, until approximately 3 months after onset. We typically use an anabolic agent (teriparatide or romosozumab) during conservative treatment to facilitate an increase in the bone marrow density [20]. If an intravertebral cleft is present, vertebroplasty should serve to augment the construct. Using a supplemental spinous plate system and/or sublaminar cable may be effective in reducing the potential risk of mechanical failure. Moreover, perioperative osteoporosis treatment could affect surgical outcomes. Murata et al. [18] have reported that the absence of postoperative teriparatide administration was a predictor of poor performance of activities of daily living postoperatively. Although not assessed in this study, the perioperative use of anabolic anti-osteoporotic agents should be strongly considered.

6. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective case series involving a small sample size for each categorized group with poor statistical power. Second, the patient cohort was heterogeneous in terms of osteoporosis severity (bone mineral density was not assessed) and underlying comorbidity. Furthermore, different surgical indications and techniques (e.g., anterior/posterior fusion techniques, bone graft material, and variable cage material) should be acknowledged as a study limitation due to the heterogeneity of the surgeons. Third, the postoperative follow-up duration of 1 year may not be adequate to determine the surgical outcomes, and an additional whole-spine radiographic analysis, including spinopelvic parameters, may have been beneficial. We emphasize that a large population study with a multivariate analysis and long follow-up data collection period is needed to confirm the reliability of our preliminary grading criteria.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed simplified grading criteria to assess the severity of LL-OVC to optimize surgical strategies. According to our retrospective multi-institutional case analysis, performing decompression alone is inappropriate for LL-OVC as most patients demonstrate intravertebral and/or intervertebral instability. Anterior column reconstruction is a key factor for successful surgical outcomes. LIF may be an effective technique for obtaining rigid anterior column stability with arthrodesis in any collapse grade. Although VCR is commonly used in severe collapse cases, it is associated with a high rate of revision. Various supplemental surgical techniques and perioperative use of anabolic anti-osteoporotic agents should be carefully considered, especially in cases of severe collapse (grade 4).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Data acquisition: TS, SM, HK, TI, MO, YT, EO, HI; conceptualization, methodology, writing original draft, data analysis: TS; manuscript review and edit: SF, BO, KM, SM; supervision: SF, SM; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Rajasekaran S, Kanna RM, Schnake KJ, et al. Osteoporotic thoracolumbar fractures-how are they different?: classification and treatment algorithm. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(Suppl 4):S49–56. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung SK, Lee SH, Kim DY, Lee HY. Treatment of lower lumbar radiculopathy caused by osteoporotic compression fracture: the role of vertebroplasty. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:461–8. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki M, Aoki M, Nishioka K, Yoshimine T. Radiculopathy caused by osteoporotic vertebral fractures in the lumbar spine. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:484–9. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sills AK. Lumbar stenosis with osteoporotic compression fracture and neurogenic claudication. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White AA, III, Panjabi MM. Clinical biomechanics of the spine. 2nd ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara A, Kobayashi N, Saiki K, Kitagawa T, Tamai K, Saotome K. Association of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association score with the Oswestry Disability Index, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and short-form 36. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:1601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–48. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2257–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Lee JW, Yeom JS, et al. A practical MRI grading system for lumbar foraminal stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1095–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima H, Uchida K, Honjoh K, Sakamoto T, Kitade M, Baba H. Surgical treatment of low lumbar osteoporotic vertebral collapse: a single-institution experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;24:39–47. doi: 10.3171/2015.4.SPINE14847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohno M, Iwamura Y, Inasaka R, et al. Surgical intervention for osteoporotic vertebral burst fractures in middle-low lumbar spine with special reference to postoperative complications affecting surgical outcomes. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2019;59:98–105. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2018-0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe K, Miyakoshi N, Kobayashi T, et al. Surgical treatment of complete fifth lumbar osteoporotic vertebral burst fracture: a retrospective case report of three patients. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:437. doi: 10.25259/SNI_553_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazan M, Ryang YM, Gerhardt J, et al. L5 corpectomy-the lumbosacral segmental geometry and clinical outcome-a consecutive series of 14 patients and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:1147–52. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita T, Sakaura H, Miwa T, Ohwada T. Modified posterior lumbar interbody fusion for radiculopathy following healed vertebral collapse of the middle-lower lumbar spine. Global Spine J. 2014;4:255–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1394124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massie LW, Zakaria HM, Schultz LR, Basheer A, Buraimoh MA, Chang V. Assessment of radiographic and clinical outcomes of an articulating expandable interbody cage in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E8. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.FOCUS17562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano A, Ryu C, Baba I, Fujishiro T, Nakaya Y, Neo M. Posterior short fusion without neural decompression using pedicle screws and spinous process plates: a simple and effective treatment for neurological deficits following osteoporotic vertebral collapse. J Orthop Sci. 2017;22:622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Aquino D, Tarawneh AM, Hilis A, Palliyil N, Deogaonkar K, Quraishi NA. Surgical approaches to L5 corpectomy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2020;29:3074–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06617-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murata K, Matsuoka Y, Nishimura H, et al. The factors related to the poor ADL in the patients with osteoporotic vertebral fracture after instrumentation surgery. Eur Spine J. 2020;29:1597–605. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, Shan Z, Zhao F, Cheung JP. Poor bone quality, multilevel surgery, and narrow and tall cages are associated with intraoperative endplate injuries and late-onset cage subsidence in lateral lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;480:163–88. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langdahl BL, Libanati C, Crittenden DB, et al. Romosozumab (sclerostin monoclonal antibody) versus teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis transitioning from oral bisphosphonate therapy: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1585–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]