Abstract

The enteric pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, similar to other facultative intracellular pathogens, has been shown to respond to the hostile conditions inside macrophages of the host organism by producing a set of stress proteins that are also induced by various environmental stresses. The stress-induced ClpXP protease is a member of the ATP-dependent proteases, which are known to be responsible for more than 90% of all proteolysis in Escherichia coli. To investigate the contribution of the ClpXP protease to the virulence of serovar Typhimurium we initially cloned the clpP and clpX operon from the pathogenic strain serovar Typhimurium χ3306 and then created insertional mutations in the clpP and/or clpX gene. The ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants were used to inoculate BALB/c mice by either the intraperitoneal or the oral route and found to be limited in their ability to colonize organs of the lymphatic system and to cause systemic disease in the host. A variety of experiments were performed to determine the possible reasons for the loss of virulence. An oxygen-dependent killing assay using hydrogen peroxide and paraquat (a superoxide anion generator) and a serum killing assay using murine serum demonstrated that all of the serovar Typhimurium ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants were as resistant to these killing mechanisms as the wild-type strain. On the other hand, the macrophage survival assay revealed that all these mutants were more sensitive to the intracellular environment than the wild-type strain and were unable to grow or survive within peritoneal macrophages of BALB/c mice. In addition, it was revealed that the serovar Typhimurium ClpXP-depleted mutant was not completely cleared but found to persist at low levels within spleens and livers of mice. Interferon gamma-deficient mice and tumor necrosis factor alpha-deficient mice failed to survive the attenuated serovar Typhimurium infections, suggesting that both endogenous cytokines are essential for regulation of persistent infection with serovar Typhimurium.

Salmonellae are facultative intracellular parasites responsible for a variety of disease syndromes, ranging from acute gastroenteritis to systemic infections like typhoid fever. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, which generally causes gastroenteritis in humans, can establish systemic infections in mouse that closely resemble typhoid fever in humans. Though many factors required for the virulence of salmonellae have been studied, the molecular mechanisms by which salmonellae cause disease are only beginning to be elucidated. Two major contributors to serovar Typhimurium virulence are encoded within the pathogenicity islands SPI-1 (46) and SPI-2 (26, 53), located at 63 and 30 centisomes on the chromosome, respectively, that code for a type III secretion system. SPI-1 is required for efficient invasion of the intestinal epithelium, suggesting a role in early infection, and SPI-2 is needed for survival and growth within macrophages, indicating a role in systemic infection (25, 26, 53). Besides the genes found within SPI-1 and SPI-2, molecular genetic approaches involving random or gene-targeted mutagenesis have identified many other bacterial genes associated with virulence in various animals and in vitro model systems, such as cultured macrophage cells and epithelial cells from various sources (1, 16, 26, 38). These mutations can be roughly classified according to their assigned gene functions, such as auxotrophy (e.g., aroA, aroC, aroD, purA, and purE), regulation of gene expression (e.g., cya, crp, rpoS, rpoE, and phoP), or secretion (ompR) (10, 13, 14, 26, 27, 29, 45, 52).

Stress response genes encode a group of proteins collectively referred to as stress proteins (for a review, see reference 47), which are induced in response to hostile environments. They have been studied by focusing on their potential roles in the virulence of various facultative intracellular bacteria, including serovar Typhimurium. During the complex multistage pathogenesis, bacteria are exposed to a variety of environmental stress conditions such as sudden elevated temperature, high osmolarity, oxidative damage, nutrient depletion, and bactericidal mechanisms associated with the host immune system (17). To successfully colonize the host organism and to avoid clearance by the immune system, a large number of general stress response systems as well as specific virulence factors would be required. The hypothesis that a global stress response plays an important role in the successful colonization and expression of virulence was initially based on indirect evidence, such as induction of the DnaK and GroEL homologues during intracellular growth of serovar Typhimurium within macrophages (5). DnaK and GroEL are major stress proteins that bind to unfolded polypeptides and function as molecular chaperones in cells (47). These chaperones stabilize the unfolded structure, protecting it from aberrant folding and nonspecific interactions with other proteins. In response to the intracellular stress associated with phagocytosis, induced levels of chaperones would be required to cope with the accumulation of partially unfolded or denatured proteins in the cell. Direct evidence for the essential role of stress proteins in bacterial virulence was originally demonstrated by insertional mutation of the stress protein gene htrA, which resulted in the inability of serovar Typhimurium to grow inside macrophages (30). The htrA gene encodes a periplasmic serine protease which is necessary for the degradation of abnormally folded proteins transported into the periplasmic space (61). Salmonellae maintain long-term residence in host phagocytic cells with bactericidal mechanisms, suggesting that intracellular bacteria experience a considerable amount of protein misfolding and damage within this compartment. It is proposed that HtrA functions as a stress protein to protect the extracytoplasmic component from damage. The essential role of the htrA homologue as a virulence factor has also been demonstrated in other facultative intracellular pathogens, such as Yersinia enterocolitica (69) and Brucella melitensis (55).

ATP-dependent proteolysis is involved in more than 90% of all cell protein turnover in Escherichia coli and appears to be essential for the rapid breakdown of abnormal protein (42). Most ATP-dependent proteolysis in E. coli has been attributed to two well-characterized proteases, Lon and Clp, which are also stress-induced proteins (for a review, see reference 17). Two types of Clp protease exist in E. coli, ClpP and ClpQ (or HslV). The ClpP proteolytic component associates with either of two ATPases, ClpA or ClpX (21, 43), whereas the ClpQ proteolytic subunit associates with the ClpY (or HslU) ATPase (32, 58). ClpP and ClpQ are not related in either amino acid structure or mode of proteolysis. The ClpP subunits form a cylindrical heptameric particle possessing the catalytic core of a serine protease (36, 43). Substrate specificity is determined by either ClpA or ClpX as a regulatory ATPase.

Though the disruption of clpP in E. coli creates no obvious phenotype and the bacteria appear to grow normally (43), the ClpP protease has a more important and diverse role in gram-positive bacteria. The disruption of the clpP gene in Bacillus subtilis causes pleiotropic effects. The B. subtilis clpP deletion mutant is highly filamentous and nonmotile (48) and cannot grow under several stress conditions, being most severely affected by starvation (67) and high temperature (48). ClpP is also required for sporulation in B. subtilis (48). The inactivation of the clpP gene in Lactococcus lactis results in significant loss of cell viability (18), indicating a major role for ClpP in basic cell metabolism. Streptomyces coelicolor contains at least two clp genes, clpP1 and clpP2. Disruption of the clpP1 gene in S. coelicolor blocks differentiation at the substrate mycelium step (12). The importance of ClpP has been also demonstrated in connection with bacterial pathogenesis. In Yersinia enterocolitica, a gastrointestinal pathogen in humans and animals, ClpP proteolysis modulates ail gene expression (54). Ail is a 17-kDa cell surface protein that confers resistance to serum killing and the ability to attach and invade cells in vitro (4). In Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive facultative intracellular pathogen responsible for infrequent but often serious opportunistic infections in humans and animals, ClpP plays a crucial role in intracellular parasitism and virulence (19). In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, the clpP gene was detected in a pool of transposon-tagged mutants with attenuated virulence (26), but the mutant has not been precisely characterized.

Recently, we cloned the clpP clpX operon of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenic strain χ3306, constructed insertional mutations in the operon, assayed their pathogenicities in an animal system, and found that disruption of the clpP and clpX genes results in persistent infection with serovar Typhimurium rather than loss of virulence in BALB/c mice. In this report, we demonstrate that the depletion of ClpXP protease in serovar Typhimurium results in inability to survive and multiply within peritoneal macrophages, inability to cause systemic infection, and ability to cause persistent infection in BALB/c mice. In addition, we show evidence that endogenous gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are required for development of a persistent infection with serovar Typhimurium in mouse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown in L-broth and L-agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). When necessary, the media were supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), and/or nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| χ3306 | Nx resistance derivative from SR-11 | Provided by R. Curtiss III |

| CS2007 | clpP:Cm in χ3306 | This study |

| CS2016 | clpP:Km in χ3306 | This study |

| CS2018 | clpX:Cm in χ3306 | This study |

| CS2022 | lon:Cm in χ3306 | This study |

| χ3306 rpoE | rpoE:Km in χ3306 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| SM10 λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA:RP4-2Tc::MuKm λpir | 70 |

| JM109 | recA endA gyrA thi hsdR supE recA Δ(lac-proAB)/F′ (traD proAB+ lacIq) lacZΔM15 | Our collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTKY229 | Carrying oriγ of R6K and oriT of RP4 | 69 |

| pTKY320b | pTW229 with 1.3-kb FspI-PstI fragment containing clpP region | This study |

| pYKY323 | pTKY320 carrying clpP:Cm | This study |

| pTKY349 | pTKY229 with 2.4-kb MluI-PstI fragment containing clpP:Cm | This study |

| pTKY366 | pTKY320 carrying clpP:Km | This study |

| pTKY367 | pTW229 with 0.9-kb NruI-EcoRI fragment containing part of clpX | This study |

| pTKY368 | pTKY229 with 2.0-kb MluI-PstI fragment containing clpP:Km | This study |

| pTKY369 | pTKY367 carrying clpX:Cm | This study |

| pCLP01 | Carrying E. coli-clpP | Provided by M. Kitagawa |

| pNK2884 | Carrying Cm resistance gene cassette | 33 |

| pUC18K | Carrying Km resistance gene cassette | 44 |

| pTW229 | Cloning vector | Our collection |

| pHSG422 | Ts for replication, Ap, Km, Cm resistance | 24 |

Abbreviations: Nx, nalidixic acid; Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Ap, ampicillin; Ts, temperature sensitive.

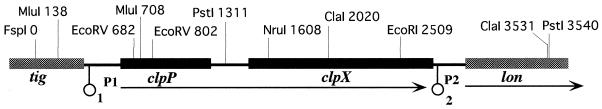

The structure of the clpP region is shown in Fig. 1.

Animals.

The mice used in this study were all 5 to 8 weeks of age and included BALB/c, C57BL/6, IFN-γ-deficient (IFN-γ−/−) mice from a C57BL/6 × Sv129 cross (64), and TNF-α-deficient (TNF-α−/−) mice from a C57BL/6 × Sv129 cross (65).

DNA isolation and manipulation, and PCR amplification and sequencing.

DNA purification, ligation, restriction analysis, and gel electrophoresis were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (59). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and Klenow enzyme were products of Takara Shuzo (Ohtsu, Japan). The DNA fragments of the clpP region were amplified using genomic DNA of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains χ3306, CS2007, CS2016, and CS2018 as a template by PCR using primers S66 (5′TAAGCGTCGTGTAGTTGTCG), S529 (5′CCGTCCATCAGGTTACAATC), S589 (5′ATGTCATACAGCGGAGAACG), A1110 (5′AGATTGACCCGTATGATGCG), A1211 (5′CAATTACGATGGGTCAAAAT), and A2828 (5′TTTCCCACACATTCAACGGC). Southern blotting was done basically as described before (69), and hybridizations using the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was carried out with Sequenase (USB, Cleveland, Ohio) and synthetic primers.

Insertional inactivation of clpP and clpX in strain χ3306.

Plasmid pTKY320 was cleaved at the EcoRV sites situated at nucleotide (nt) 682 and nt 802 (see Fig. 1) and ligated to the chloramphenicol (Cm) resistance gene block generated from the BamHI-digested and filled-in pNK2884. The resultant plasmid, pTKY323, was cleaved at the MluI site situated at nt 138 and HindIII in the vector plasmid, and the overhanging ends were filled in with Klenow enzyme. The generated clpP:Cm fragment was ligated to the filled-in EcoRI site of pTKY229, which is a transferable suicide vector previously constructed by us (70). A suicide feature of pTKY229 is based on one of the replication origins of R6K, oriγ, which is functional only in a host when the π protein is encoded by the pir gene. The resulting mutator plasmid, pTKY349, carrying clpP:Cm was introduced into strain SM10λpir, which can mobilize the plasmid by the conjugative function provided in trans from the RP4 integrated chromosome. Conjugative crosses with serovar Typhimurium χ3306 were carried out as previously reported (70). The chromosomal clpP was replaced by the clpP:Cm construct by double recombination. The clpP mutant was selected by resistance to chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid. Allelic exchange was checked by Southern blot analysis and direct sequencing of the clpP:cat region in the resultant strain (CS2007) mutant amplified by PCR.

FIG. 1.

Genomic organization and restriction site of the serovar Typhimurium χ3306 clpP clpX locus. The DNA sequence established in the present work extends from the FspI site at position 0 to the PstI site at position 3540 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database accession number AB033628). The horizontal arrows indicate the direction of transcription. The promoters P1 and P2 were deduced from the sequences. Potential stem-loop structures numbered 1 and 2 are indicated (circles).

To generate a nonpolar mutation in the clpP gene, EcoRV-cleaved pTKY320 was ligated to the kanamycin (Km) resistance gene block generated from SmaI-digested pUC18K. The resultant plasmid, pTKY366, was digested with MluI and HindIII, and the overhanging ends were filled in with Klenow enzyme. The generated clpP:Km fragment was ligated to the filled EcoRI site of suicide vector pTKY229. Strain SM10λpir, harboring the resulting mutator plasmid pTKY368 with clpP:Km, was mobilized into serovar Typhimurium χ3306 by conjugation. The chromosomal clpP was replaced by the clpP:Km construct by double recombination. The clpP mutant was selected by resistance to kanamycin and nalidixic acid. Allelic exchange was checked by Southern blot analysis and direct sequencing of the clpP:Km region in the resultant strain (CS2016) amplified by PCR.

To insert a mutation into the clpX gene, pTKY367 was cleaved at ClaI site situated at nt 2020 and then ligated to the cat gene block prepared from pNK2884. The resulting plasmid, pTKY369, was partially digested with EcoRI and at the generated clpX:Cm of the EcoRI site of suicide vector pTKY229. The chromosomal clpX was replaced in the same way used to construct the clpP:Cm mutant. Allelic exchange was checked by Southern blot analysis and direct sequencing of the clpP:Cm region in the resulting strain (CS2018) amplified by PCR.

Immunoblot analysis.

Equivalent numbers of bacterial cells were suspended in sample buffer (35), boiled for 5 min, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Separated proteins on the gels were transferred onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) as suggested by the manufacturer. Proteins were reacted with rabbit anti-E. coli ClpX (1:25,000) antibody or anti-E. coli Lon antibody (1:25,000), followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G as the secondary antibody. The enzymatic reactions were performed in the presence of nitro blue tetrazolium (30 mg/ml) (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) and bromochloroindolylphosphate (Amresco, Solon, Ohio) (15 mg/ml).

Survival and growth of serovar Typhimurium strains in macrophage cells.

The ability of the different strains of serovar Typhimurium to survive and grow in macrophage cells was assessed by using resident peritoneal macrophages prepared from BALB/c mice. The macrophages were harvested from peritoneal lavage using cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Sigma, Saint Louis, Mo.) suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, allowed to adhere to each well of 24-well plates, and then incubated at 37°C before infection. Bacterial cells were grown in L-broth at 37°C to the exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.5), and a portion was opsonized with 50% fresh normal mouse serum for 15 min at 37°C and diluted in DMEM. Opsonized bacteria were added to each well at a multiplicity of infection of 5. The plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g to enhance and synchronize infection. The cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C to permit phagocytosis, and the free bacteria were removed by three washes with HBSS warmed at 37°C. DMEM containing 10% FCS and 100 μg of gentamicin per ml was added, and the cells were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. The cells were washed with the warmed HBSS three times, followed by incubation with DMEM containing 10% FCS and 10 μg of gentamicin per ml at 37°C. Wells were sampled at various times by aspirating the medium, three washes with HBSS, and lysing each well with PBS containing 0.1% sodium deoxycholate. The triplicate samples were plated individually after appropriate dilutions.

Determination of viable bacteria in organs of mice after infection with serovar Typhimurium.

Serovar Typhimurium strains grown in L-broth at 37°C to the late exponential growth phase were diluted in sterile PBS. The actual number of bacteria present was determined by counting viable cells. Mice were challenged either orally or intraperitoneally by injection. The spleens and livers were aseptically removed at indicated times after infection and homogenized in PBS. The numbers of viable bacteria in the organs of infected mice were established by plating serial 10-fold dilutions of organ homogenates on L-agar plates. Colonies were routinely counted 18 to 24 h later.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data of the complete operon reported here will appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession number AB033628.

RESULTS

Genetic organization of the strain χ3306 clpP locus.

To determine the nucleotide sequence of the clpP locus of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium χ3306, we initially cloned the 16-kb BamHI fragment prepared from chromosomal DNA which hybridized to the DNA fragment containing the E. coli clpP gene from pCLP01 (data not shown). By using subclones and synthetic oligonucleotides, the sequence of the clpP locus was determined. A total of 3,540 bp were sequenced, revealing the presence of four open reading frames (the region is shown schematically in Fig. 1). The ClpP protein predicted from the sequence was 99.0% identical to ClpP of E. coli. Downstream was an open reading frame encoding a protein 97.6% identical to ClpX of E. coli. Immediately upstream of the ATG start codon for clpP, a consensus ribosome-binding site and putative −10 and −35 sequences were located. There is an intergenic region of 252 bp between the clpP and clpX genes. No apparent promoter elements for clpX were found in this region. A consensus ribosome-binding site was identified 9 bp upstream of clpX. A potential stem-loop structure is located downstream of clpX, indicating a rho-independent transcriptional terminator. Downstream of clpX, the sequence is assigned to a homologue of the E. coli lon gene, which encodes an ATP-dependent serine protease (8), with a consensus ribosome-binding site. A consensus heat shock promoter sequence (9) was also identified upstream of the lon gene. Upstream of clpP, the sequence is predicted to be a homologue of the E. coli tig gene, whose product is known to be a ribosome-associated chaperone, trigger factor (23).

Construction of clpP and clpX disruption mutants of strain χ3306.

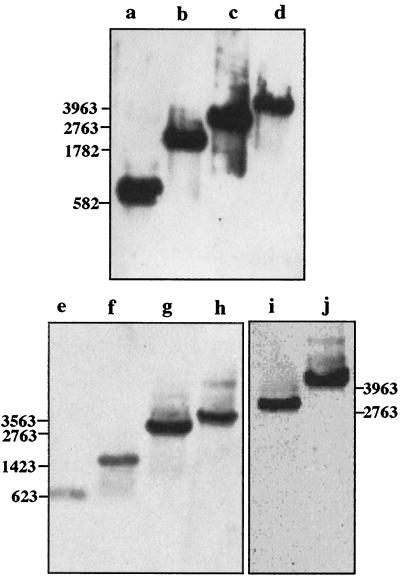

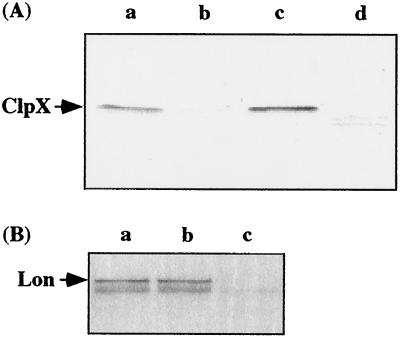

Since sequence analysis revealed that the clpP gene exists in an operon with clpX, we constructed a clpP clpX double mutant, a clpP mutant, and a clpX mutant. The clpP gene was insertionally inactivated in vitro by using a Cm resistance cassette, and this construct was used to create the serovar Typhimurium χ3306 clpP:Cm mutant (strain CS2007) by allelic exchange. The disruption of the clpP gene in CS2007 was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 2). To examine whether the insertion affected the expression of clpX, which is downstream of clpP, lysates from the wild-type parent and strain CS2007 were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-ClpX antiserum (Fig. 3A). The absence of the band corresponding to ClpX suggests that insertion of the cassette in clpP resulted in a polar mutation in the clpX gene. Since a lon gene which is downstream of clpX is preceded by a consensus promoter sequence, it is unlikely that the insertion of a polar mutation in the clpP gene blocks the expression of the lon gene. This was confirmed by immunoblot analysis with anti-Lon antiserum (Fig. 3B). The result suggests that the insertion of the Cm cassette in the clpP gene does not affect the expression of the lon gene.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis showing insertional inactivation of clpP and clpX in mutant derivatives of serovar Typhimurium χ3306. The clpP or clpX region was amplified by PCR, using genomic DNA prepared from strains χ3306 (lanes a, c, e, g, and i), CS2007 (clpP:Cm; lanes b and d), CS2016 (clpP:Km; lanes f and h), and CS2018 (clpX:Cm; lane j) as templates and three sets of oligonucleotide primers, S529-A1110 (a and b), S589-A1211 (e and f), and S66-A2828 (c, d, g, h, i, and j). The nucleotide sequences of these primers are shown in Materials and Methods. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel by electrophoresis and subjected to Southern hybridization using the DNA fragments between nt 529 and 1110, covering the entire clpP open reading frame (a to h), and between nt 1743 and 2391, carrying a part of the clpX gene (i to j), as probes. Sizes are shown in nt.

FIG. 3.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of proteins from serovar Typhimurium strains χ3306 (lane a), CS2007 (clpP:Cm; lane b), CS2016 (clpP:Km; lane c), and CS2018 (clpX:Cm; lane d) with an antiserum against E. coli ClpX. (B) Immunoblot analysis of proteins from strains χ3306 (a), CS2007 (clpP:Cm; b), and CS2022 (lon:Cm; c) with an antiserum against E. coli Lon.

To create a nonpolar mutation in clpP, a Km resistance cassette that allows natural downstream transcription (44) was used. This cassette has no promoter or transcription terminator. In addition, the Km resistance gene is preceded by a translation stop codon and immediately followed by a consensus ribosome-binding site. The disruption of the clpP gene in the resulting strain, the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium χ3306 clpP:Km mutant (strain CS2016), was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 2). The immunoblot analysis with anti-ClpX antiserum (Fig. 3A) suggests that the insertion of the cassette in the clpP gene does not affect the expression of the clpX gene.

The clpX gene was insertionally inactivated in vitro by using a Cm resistance cassette, and this construct was used to create the serovar Typhimurium χ3306 clpX:cat mutant (strain CS2018) by in vivo homologous recombination. The disruption of the clpX gene was confirmed by PCR and Southern analysis of DNA prepared from the mutant (Fig. 2) and by immunoblot analysis using anti-ClpX antiserum (Fig. 3A).

Analysis of the role of the ClpXP protease genes in virulence in mouse.

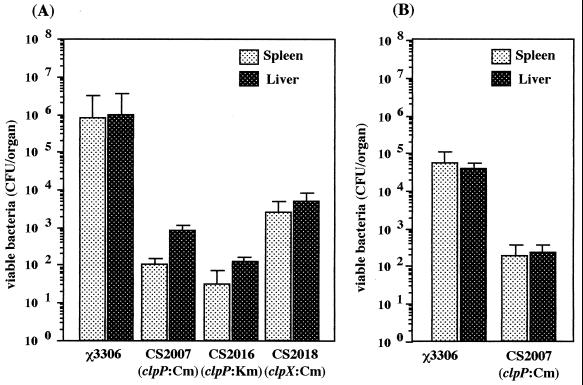

One estimation of the virulence of serovar Typhimurium is the ability of the bacteria to establish a lethal systemic infection in mice. To measure the contribution of the ClpXP protease in serovar Typhimurium virulence, we determined the abilities of serovar Typhimurium clpP:Cm, clpP:Km, and clpX:Cm mutants to grow in the organs of BALB/c mice. As shown in Fig. 4A, mice that were infected by intraperitoneal administration with 102 CFU of χ3306 had more than 106 bacteria in both the spleen and liver on day 5 after infection. All five mice infected with χ3306 died at day 5. In contrast, mice infected with mutant strain CS2007 (clpP:Cm), CS2016 (clpP:Km), or CS2018 (clpX:Cm) appeared to be much more capable of controlling infection. Mice infected with each mutant strain had approximately 102 bacteria in the spleen and 103 bacteria in the liver. Unlike mice infected with the wild-type strain χ3306, which colonizes the spleen and liver in large numbers, resulting in death 5 days after infection, all mice challenged with mutant strain CS2007, CS2016, or CS2018 survived beyond day 5 after infection, indicating that these strains had lost the ability to cause a systemic infection in mice.

FIG. 4.

Colonization of the organs of BALB/c mice following intraperitoneal (A) and oral (B) administration of serovar Typhimurium strains χ3306, CS2007 (clpP:Cm), CS2016 (clpP:Km), and CS2018 (clpX:Cm). On day 5 after infection, the numbers of bacteria recovered from the spleens and livers of five mice were determined. The error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means of these counts.

BALB/c mice were inoculated orally with 2 × 108 cells of strain χ3306 or CS2007 (clpP:Cm). The number of bacteria in spleens and livers was assessed on day 5 after challenge (Fig. 4B). The wild-type strain χ3306 colonized the spleen and liver in large numbers and resulted in death 5 days after infection. Again, the ClpXP-depleted mutant strain, CS2007, exhibited an impaired ability to cause a systemic infection in mice.

Depletion of the ClpXP protease in strain χ3306 impairs survival in macrophages.

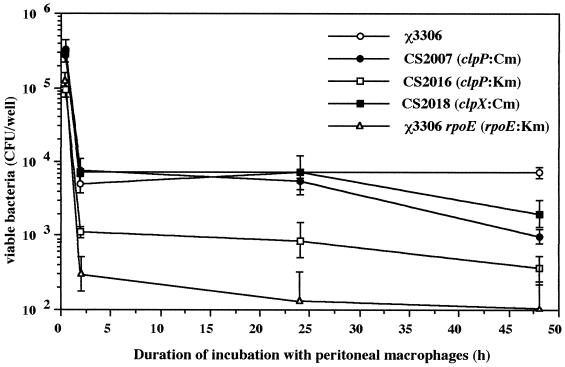

One of the most probable factors contributing to the reduced virulence of serovar Typhimurium ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants is the reduced capacity to survive interactions with professional killing cells such as macrophages in mouse. To address this possibility, we examined the capacity of mutant strains CS2007 (clpP:Cm), CS2016 (clpP:Km) and CS2018 (clpX:Cm) to survive and grow in macrophages. It is known that serovar Typhimurium grown under conditions such as hyperosmolarity (0.3 M NaCl) or a change in the pH of the medium from 6.0 to 8.0 that allow expression of the type III secretion system encoded by SPI-1 readily kills cultured macrophages (7, 11). To avoid the cytotoxic effect of expression of the type III secretion system, bacterial cells were grown in L-broth (pH 7.0) to infect the macrophages. The resident peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice were cultured and exposed to the different strains for 30 min at a multiplicity of infection of 5 bacteria per macrophage cell. Bacterial growth was then monitored for 48 h (Fig. 5). Previous studies with serovar Typhimurium showed that the rpoE gene encoding an alternative ς factor, ςE, is critically involved in intracellular survival within macrophages (29). To test the validity of the resident peritoneal macrophages of mice prepared in the present study, the macrophage cells were challenged with the opsonized serovar Typhimurium rpoE:Km strain. The number of viable bacteria was drastically decreased during the first 2 h of incubation. Between 2 and 48 h, the number of rpoE:Km bacteria present intracellularly had decreased 10-fold, whereas the number of the wild-type strain, χ3306, had increased 4-fold, suggesting a valid Salmonella-macrophage interaction system. When macrophages were challenged with strains CS2007, CS2016, and CS2018, none of the mutants seemed to grow intracellularly. Between 2 and 48 h after infection, the number of mutant bacteria present within macrophages had decreased ∼9-fold. These results suggest that the ClpXP protease is required for the intracellular survival and growth of serovar Typhimurium within macrophages.

FIG. 5.

Fate of serovar Typhimurium strain χ3306 and mutant derivatives within peritoneal macrophages prepared from BALB/c mice. The error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means of triplicate samples assayed individually.

In addition, the sensitivity of these mutants to hydrogen peroxide and superoxide, which mimic the oxidative killing mechanisms by respiratory burst in macrophages and phagosomes, was assessed by determining their sensitivity to 3% hydrogen peroxide and 2% paraquat (a superoxide anion generator) using the disk diffusion assay. All of the serovar Typhimurium ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants were as resistant to these killing mechanisms as the wild-type strain (data not shown). Salmonellae are typically resistant to the killing activity of complement that is present in serum. Since serum resistance is known to be an important factor for full expression of virulence in serovar Typhimurium, we examined the effect of ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutations on serum sensitivity. Mutant strains CS2007, CS2016, and CS2018 were exposed to normal and heat-inactivated BALB/c mouse serum, and their viability was determined by counting the CFU for each assay. None of the mutants was sensitive to the killing action of mouse serum (data not shown).

Depletion of ClpXP protease in strain χ3306 results in persistent infection of BALB/c mice.

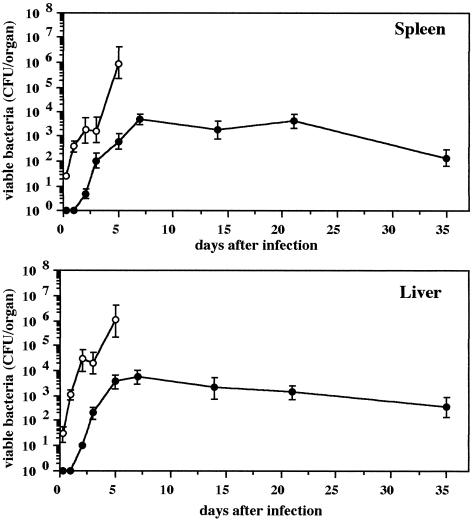

To determine whether the loss of virulence was due to the inability of the mutants to grow in the host, the number of bacteria in spleens and livers of a group of mice infected with strain CS2007 (clpP:Cm) was monitored for up to 35 days after infection (Fig. 6). At 3 days postinfection, a few bacteria were recovered from both organs of mice infected with the clpP:Cm mutant compared with the parental strain, whose number increased to approximately 2 × 103 CFU in the spleens and 3 × 104 CFU in the livers of the infected mice. Unlike mice infected with the wild type, which resulted in death by 5 days after infection, mice challenged with the same number (102 CFU) of the clpP:Cm mutant survived. Beginning at 7 days and continuing through 35 days postinfection, however, the clpP:Cm mutant bacteria were not cleared from the mice, but a similar number of the bacteria were recovered from the spleens and livers even on day 35 after initial infection. The clpP:Cm mutant also persisted in mice for several weeks following oral challenge with 108 cells (result not shown).

FIG. 6.

Kinetics of bacterial growth in the organs of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal administration of 102 CFU of serovar Typhimurium strains χ3306 (open circles) and CS2007 (clpP:Cm, solid circles). Each time point indicates the mean ± standard deviation for a group of five mice.

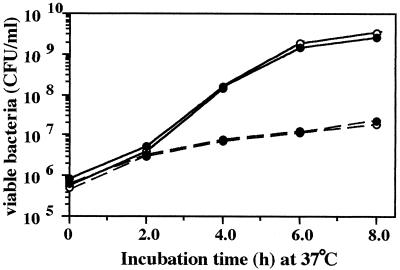

To examine whether the reduced virulence of the ClpXP-depleted mutant is due to its inherently poor growth, the growth rate of strain CS2007 (clpP:Cm) was compared to that of wild-type strain χ3306 using bacteria carrying a few copies of plasmid pHSG422. This plasmid exhibits defective replication above 37°C and is diluted out during bacterial growth (24). The use of this plasmid to differentiate bacterial growth rate has been described previously (3, 22). Bacterial growth at 37°C was monitored for 8 h. As shown in Fig. 7, the proportions of the population carrying pHGS422 were indistinguishable between strains χ3306 and CS2007 up to 8 h, indicating no significant differences in growth rate of these strains. Therefore, it is unlikely that the reduced virulence of the ClpXP-depleted mutant is attributable to impaired bacterial growth.

FIG. 7.

Growth curves of serovar Typhimurium strains carrying pHGS422 at 37°C. Bacterial cells of strains χ3306 (open circles) and CS2007 (clpP:Cm, solid circles) were grown overnight at 30°C to obtain uniform plasmid copy number, diluted 1:500 into fresh medium, and then incubated for 8 h at 37°C. Bacterial cells were diluted at the indicated time points and then plated to determine the numbers of total bacteria (solid lines) and ampicillin-resistant (pHSG422-containing) bacteria (dotted lines).

These results indicate that the ClpXP protease is essential for systemic infection by serovar Typhimurium and the depletion of its function results in persistent infection with serovar Typhimurium in BALB/c mice.

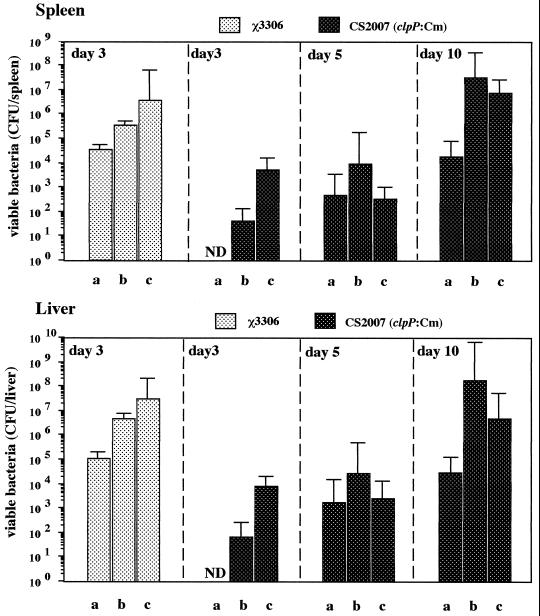

Effect of endogenous cytokines on persistence of ClpXP-depleted mutant in mice.

A previous report demonstrated that IFN-γ and TNF-α play an essential role in acquired resistance during the early phase of serovar Typhimurium infection (49). Therefore, we assessed the relevance of endogenous cytokines in the establishment and maintenance of the persistent infection developed by the ClpXP-depleted mutant by monitoring bacterial growth in IFN-γ- and TNF-α-deficient mice following infection. C57BL/6 mice, IFN-γ−/− mice, and TNF-α−/− mice were infected with strain χ3306 or mutant strain CS2007 (clpP:Cm), and the number of bacterial cells in the spleens and livers was determined on day 3 after infection (Fig. 8). The number of wild-type cells in both spleens and livers of the IFN-γ- and TNF-α-deficient mice was higher than in C57BL/6 mice. All cytokine-deficient mice died following infection with the wild-type strain. While no clpP:Cm bacterial cells were detected in either the spleens or livers of C57BL/6 mice, significant numbers were detected in the organs of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-deficient mice. The number of bacteria in the cytokine-deficient mice infected with the clpP:Cm mutant was also examined on days 5 and 10 after infection (Fig. 8). In these mice, clpP:Cm bacteria progressively increased to 108 and 107 per organ in the IFN-γ- and TNF-α-deficient mice, respectively, by day 10 postinfection. After infection with the clpP:Cm mutant, all the cytokine-deficient mice died on day 10 after infection. Though no clpP:Cm bacterial cells were detected in either the spleens or livers of C57BL/6 mice on day 3 postinoculation, significant numbers were detected in the organs of the mice 5 and 10 days postinoculation (Fig. 8). Furthermore, we confirmed that the clpP:Cm mutant persisted in the C57BL/6 mice by monitoring the numbers of bacteria in the spleens and livers for several weeks (data not shown). These results suggest that both endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α are necessary for developing in vivo persistence after infection with the clpP:Cm mutant.

FIG. 8.

Bacterial growth in the organs of IFN-γ-deficient and TNF-α-deficient mice during infection with different strains of serovar Typhimurium. C57BL/6 mice (a) and IFN-γ- (b) and TNF-α- (c) deficient mice were infected intraperitoneally with 102 CFU of serovar Typhimurium strains χ3306 and CS2007 (clpP:Cm). The numbers of bacterial cells in the spleens and livers were determined on days 3, 5, and 10 of infection. ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

ClpP proteases have been identified not only in a wide range of bacteria but also in plants and animals (56). In E. coli, the ClpP protein is a cylindrical heptameric particle, forming the catalytic core of the protease, which associates with one of two ATPases, ClpA or ClpX, thus determining the substrate specificity (21, 36, 43). A hexamer of the Clp ATPase is located on the ClpP rings. The sequence analysis of the serovar Typhimurium clpP-clpX operon cloned in the present study revealed that these homologues show high identity with the equivalent E. coli proteins. The functional regions in both proteins are also conserved between serovar Typhimurium and E. coli. In ClpP, these include Ser-111 and His-136, which are required for proteolytic activity, and the 14-amino-acid precursor peptide, which is processed to produce the active form of ClpP (43). An ATP-binding motif, two tail motifs, and a zinc finger motif (21) are also found in the serovar Typhimurium ClpX homologue. The genetic organization of the clpP region in serovar Typhimurium, tig-clpP-clpX-lon, is also identical to that of E. coli (21).

The inactivation of clpP in E. coli results in no obvious phenotype, and clpP mutants appear to grow normally (43). However, as clpP genes from other organisms have been identified, it has become increasingly apparent that the ClpP protease performs more important and diverse roles in other bacteria. The inactivation of the clpP gene in L. lactis results in significant loss of cell viability, suggesting a major role for ClpP proteolysis in basic cell metabolism (18). Similarly, depletion of ClpP in B. subtilis causes pleiotropic effects such as filamentation, nonmotility, and impaired growth under certain stress conditions, starvation and high temperature (48). In the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, ClpP is essential for cell growth (28).

Here we have extended the study of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants by comparing their virulence to that of the parental strain, serovar Typhimurium χ3306. The virulence assay in the mouse model demonstrated that the ability of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants to cause systemic infection was apparently decreased (Fig. 4). During the course of infection in mice, serovar Typhimurium, which colonizes many different organs, including the Peyer's patches of the small intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, and liver, is found in both extracellular and intracellular locations (16, 57). The ability of serovar Typhimurium to multiply inside professional phagocytic cells has been linked to virulence in mice (11, 37). Pleiotropic regulators of Salmonella virulence have been identified and characterized in the mouse model and in the cultured macrophage cell model as well. Mutations in any of these regulators render salmonellae avirulent. These include mutations in two-component regulator systems (phoP/phoQ and ompR/envZ) (13, 45), the heat shock protein htrA (30), and sigma factors (rpoS and rpoE) (14, 29). The rpoS product, ςs, which regulates gene expression in response to nutrient deprivation during stationary phase, is known to also regulate the spv genes carried on a plasmid essential for Salmonella virulence (34). Though serovar Typhimurium rpoS mutants are avirulent, they replicate normally inside macrophages (50). On the contrary, the mutant of rpoE encoding ςE, which is involved in the gene expression for several extracytoplasmic proteins, was severely defective in its ability to survive in macrophages and highly attenuated in mice (29).

To gain a better understanding of why the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants have lost the ability to cause systemic disease, we examined the ability of these mutants to replicate inside macrophages using an in vitro assay with resident peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice and found that none of these mutants could survive or grow within the peritoneal macrophages of mice (Fig. 5). While the rates of survival of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants were only four- to ninefold lower than that of the wild-type strain over a 48-h period, the disparity could explain the reduced growth rate of the mutants in the spleen and liver over the entire mouse infection period. We cannot explain definitively why the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants are unable to replicate intracellularly and are attenuated in mice at present. This is probably due to the combination of defects generated from the depletion of the ClpXP protease. The activity would be required to cope with the accumulation of partially unfolded or denatured protein in bacteria exposed to various killing mechanisms associated with the host defense system during infection. Furthermore, the ClpXP protease could be involved in the expression of virulence genes and/or the turnover of virulence factors. One virulence gene known to be regulated by ClpP, rpoS, is also modulated by DksA (68) and MviA (2) in connection with serovar Typhimurium virulence. DksA appears to positively regulate the expression of rpoS at the level of translation. The decreased virulence of a dksA mutant can be explained, at least partially, by the effect of DksA on the expression of rpoS, which is required for virulence (14, 50). However, it is probable that ςs is overproduced in serovar Typhimurium ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants, because the ClpXP protease rapidly degrades ςs in exponentially growing E. coli (60). MviA is also known to affect ςs production posttranslationally via proteolysis (2). Therefore, at present, it is not clear why mutations (clpP/clpX and mviA) that cause increases in ςs levels also attenuate Salmonella virulence. It would appear that the bacteria need to modulate ςs activity as they encounter areas of high and low stress within the host during pathogenesis. Alternatively, it is possible that ClpXP directly modulates the levels of the major contributors for virulence specified by the SPI-1 and SPI-2 regions on the serovar Typhimurium chromosome.

Of further interest is the finding that the ClpXP-depleted mutant persists in the mouse for long periods of time without causing an overwhelming systemic infection. The ability of the ClpXP-depleted mutant to survive and grow within the lymphatic environment of the mouse was examined by monitoring colonization in the spleens and livers of mice for up to 35 days. The monitoring revealed that there was persistence and net growth of serovar Typhimurium with a moderate growth rate in both organs for 35 days. It is clear that the mice, while not able to eliminate the ClpXP-depleted mutant organisms, were able to control growth of the bacterial strain in the lymphatic organs and survive. Most salmonellae in the spleens and livers of the infected mice are localized within the phagocytes present in the focal lesions (57). TNF-α, IFN-γ, and nitric acid derivatives appear to be required for the suppression of Salmonella growth in the reticuloendothelial system (39, 49, 66). TNF-α is required for the recruitment of mononuclear cells in the tissues and for granuloma formation (41) and IFN-γ activates macrophages to kill salmonellae (31). We therefore examined whether the endogenous cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ are necessary for the development of a persistent infection by the serovar Typhimurium ClpXP-depleted mutant by monitoring bacterial growth in TNF-α- and IFN-γ-deficient mice following infection. In the organs of these mice, the ClpXP-depleted mutant colonized and progressively grew, resulting in bacterial counts in the spleens and livers of the cytokine-deficient mice that were 100- to 1,000-fold higher than normally observed in C57BL/6 mice. These mice did not survive beyond 10 days postinfection (Fig. 8).

Mice infected with salmonellae become hyper-susceptible to endotoxin. A previous study reported that interleukin-12 neutralization prevented the death of infected mice following subcutaneous injection of lipopolysaccharide (40). It is therefore possible that interleukin-12 is also required to control the persistence of the serovar Typhimurium ClpXP-depleted mutant in mice. The abilities to control growth and persist in the lymphatic organs of the host are considered important in the development of a live vaccine strain. Attenuated Salmonella mutants present potential live vaccine candidates to protect against infection or to deliver heterologous antigen to the mammalian immune system. The present results show that such an attenuated strain may cause severe infections, but only in animals with serious and persistent immunological defects.

Several other serovar Typhimurium strains that cause persistent infections in mice have been described. These include a purE derivative (52), an ompR mutant (13), an aroA mutant (6), an htrA mutant (62), an agfA mutant (62), and an surA mutant (63). Whereas these mutants have been well characterized for their potential usefulness as vaccines against virulent Salmonella infection and carriers expressing foreign protein antigens derived from unrelated pathogens, the specific involvement of these genes in persistent infection has not been demonstrated. Persistent infection is the result of balance between virulence and host immunity. Though the inability of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX mutants to cause systemic infection could be explained by the loss of ability to survive or grow inside macrophages, the conclusion that the mutation somehow specifically associates with the persistent infection in mice cannot be definitively reached on the present results.

Systemic infection by serovar Typhimurium in mice closely resembles typhoid fever in humans caused by infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. It is well known that, in certain persons, S. enterica serovar Typhi persists in the gall bladder and that these persons can shed bacteria in their feces for years as chronic carriers. The ClpXP-depleted mutant in the present study will be useful for resolving the mechanisms by which chronic infection with salmonellae is established and developed, in combination with further studies on the fundamental mechanisms of immunity to salmonellosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to R. Curtiss III for sending strain χ3306. We are indebted to M. Zylicz and T. Ogura for their gifts of anti-ClpX antiserum and anti-Lon antiserum, respectively. We thank Y. Hachiman, Y. Ukyo, and A. Tokumitsu for technical assistance. We thank D. Ang for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumler A J, Kusters J G, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium loci involved in survival within macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1623–1630. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1623-1630.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin W H, Jr, Yother J, Hall P, Briles D E. The Salmonella typhimurium locus mviA regulates virulence in ltys but not ltyr mice: functional mviA results in avirulence; mutant (nonfunctional) mviA results in virulence. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1043–1083. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin W H, Jr, Hall P, Roberts S J, Briles D E. The primary effect of the Ity locus is on the rate of growth of Salmonella typhimurium that are relatively protected from killing. J Immunol. 1990;144:3143–3151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bliska J, Falkow S. Bacterial resistance to complement killing mediated by Ail protein of Yersinia enterocolitica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3561–3565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchimeier N A, Heffron F. Induction of Salmonella stress proteins upon infection of macrophages. Science. 1990;248:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1970672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatfield S N, Strahan K, Pickard D, Charles I G, Hormaeche C E, Dougan G. Evaluation of Salmonella typhimurium strains harbouring defined mutations in htrA and aroA in the murine salmonellosis model. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L M, Kaniga K, Galán J E. Salmonella spp. are cytotoxic for cultured macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1101–1115. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.471410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung C H, Goldberg A L. The product of the lon (capR) gene in Escherichia coli is the ATP-dependent protease La. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4931–4935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowing D W, Bardwell J C A, Craig E A, Woolford C, Hendrix R W, Gross C. Consensus sequence of Escherichia coli heat-shock gene promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2679–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M. Salmonella typhimurium deletion mutants lacking adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein are avirulent and immunogenic. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3035-3043.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daefler S. Type III secretion by Salmonella typhimurium does not require contact with a eukaryotic host. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:45–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Crecy-Lagard V, Servant-Moisson P, Viala J, Grandvalet C, Mazodier P. Alteration of the synthesis of the Clp ATP-dependent protease affects morphological and physiological differentiation in Streptomyces. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:505–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorman C J, Chatfield S, Higgins C F, Hayward C, Dougan G. Characterization of porin and ompR mutants of a virulent strain of Salmonella typhimurium: ompR mutants are attenuated in vivo. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2136–2140. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2136-2140.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative sigma factor katF (rpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field P I, Swanson R V, Haidaris C G, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay B B. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of Salmonella pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;192:163–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78624-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster J W, Spector M P. How Salmonella survive against the odds. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:145–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frees D, Ingmer H. ClpP participates in the degradation of misfolded protein in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:79–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaillot O, Pellegrini E, Bregeholt S, Nair S, Berche P. The ClpP serine protease is essential for the intracellular parasitism and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1286–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottesman S. Proteases and their targets in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:465–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottesman S, Clark W P, de Crecy-Lagard V, Maurizi M R. ClpX, an alternative subunit for the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22618–22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulig P A, Doyle T J, Clare-Salzler M J, Maiese R L, Matsui H. Systemic infection of mice by wild-type but not Spv 2 Salmonella typhimurium is enhanced by neutralization of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5191–5197. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5191-5197.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guthrie B, Wickner W. Trigger factor depletion or overproduction causes defective cell division but does not block protein export. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5555–5562. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5555-5562.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Franklin F C H, Nordheim A, Timmis K N. Specific purpose plasmid cloning vectors. I. Low copy number, temperature-sensitive, mobilization-defective pSC101-derived containment vectors. Gene. 1981;16:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hensel M, Shea J E, Raupach B, Monack D, Falkow S, Gleeson C, Holden D W. Functional analysis of ssaJ and the ssaK/U operon, 13 genes encoding components of the type III secretion apparatus of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3271699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hensel M, Shea J E, Gleeson C, Johrns M D, Dalton E, Holden D W. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science. 1995;269:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.7618105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A D. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–240. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang C, Wang S, Chen L, Lemieux C, Otis C, Turmel M, Lue X Q. The Chlamydomonas chloroplast clpP gene contains translated large insertion sequences and is essential for cell growth. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:151–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00283516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphreys S, Stevenson A, Bacon A, Weinhardt A B, Roberts M. The alternative sigma factor, ςE, is critically important for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1560–1568. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1560-1568.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson K, Charles I, Dougan G, Pickard D, O'Gaora P, Costa G, Ali T, Miller I, Hormaeche C. The role of a stress-response protein in Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagaya K, Watanabe K, Fukazawa Y. Capacity of recombinant gamma interferon to activate macrophages for Salmonella-killing activity. Infect Immun. 1989;57:609–615. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.609-615.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessel M, Maurizi M R, Kim B, Kocsis E, Trus B, Singh S K, Steven A C. Homology in structural organization between E. coli ClpAP protease and the eukaryotic 26S proteasome. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:587–594. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleckner N, Bender J, Gottesman S. Uses of transposons, with emphasis on Tn10. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:139–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowarz L, Coynault C, Robbe-Saule V, Norel F. The Salmonella typhimurium katF (rpoS) gene: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of spvR and spvABCD virulence plasmid gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6852–6860. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6852-6860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen C N, Finley D. Protein translocation channels in the proteasome and other proteases. Cell. 1997;91:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung K Y, Finlay B B. Intracellular replication is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11470–11474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahan M J, Strauch J M, Mekalanos J J. Selection of bacterial virulence genes that are specifically induced in host tissue. Science. 1993;259:686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.8430319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mastroeni P, Arena A, Costa G B, Liberto M C, Bonina L, Hormaeche C E. Serum TNF-α in mouse typhoid and enhancement of a Salmonella infection by anti-TNF-α antibodies on a Salmonella infection in the mouse model. Microb Pathog. 1991;14:473–480. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90091-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mastroeni P, Harrison J A, Robinson J H, Clare S, Khan S, Maskell D J, Dougan G, Hormaeche C E. Interleukin-12 required for control of the growth of attenuated aromatic-compound-dependent salmonellae in BALB/c mice: role of gamma interferon and macrophage activation. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4767–4776. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4767-4776.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mastroeni P, Skipper J N, Hormaeche C E. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibodies on histopathology of primary Salmonella infections. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3674–3682. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3674-3682.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maurizi M R. Proteases and protein degradation in Escherichia coli. Experientia. 1992;48:178–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01923511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Katayama Y, Rudikoff S, Pumphrey J. Sequence and structure of ClpP, the proteolytic component of the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12536–12545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menard R, Sansonetti P J. Isolation of noninvasive mutants of gram-negative pathogens. Methods Enzymol. 1994;236:493–509. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)36038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller S I, Kakral A M, Mekalanos J J. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5054–5058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mills D M, Bajaj V, Lee C A. A 40 kb chromosomal fragment encoding Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene is absent from the corresponding region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:749–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morimoto R I, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C. Progress and perspectives on the biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperone. In: Morimoto R I, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C, editors. The biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Msadek T, Dartois V, Kunst F, Herbaud M L, Denizot F, Rapoport G. ClpP of Bacillus subtilis is required for competence, development, motility, degradative enzyme synthesis, growth at high temperature and sporulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:899–914. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nauciel C, Espinasse-Maes F. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha in resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60:450–454. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.450-454.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nickerson C A, Curtiss R., III Role of sigma factor RpoS in initial stages of Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1814–1823. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1814-1823.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishikawa S, Miura T, Sasaki S, Nakane A. The protective role of endogenous cytokines in host resistance against an intragastric infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;16:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Callaghan D, Maskell D, Liew F Y, Easmon C S F, Dougan G. Characterization of aromatic- and purine-dependent Salmonella typhimurium: attenuation, persistence, and ability to induce protective immunity in BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1988;56:419–426. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.419-423.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ochman H, Soncini F C, Solomon F, Groisman E A. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella survival in host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7800–7804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pederson K J, Carlson S, Pierson D E. The ClpP protein, a subunit of the Clp protease, modulates ail gene expression in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:99–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5551916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop R M., II A Brucella melitensis high temperature-requirement A (htrA) deletion mutant demonstrates a stress response defective phenotype in vitro and transient attenuation in the BALB/c mouse model. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porankiewicz J, Wang J, Clarke A K. New insights into the ATP-dependent Clp protease: Escherichia coli and beyond. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:449–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richter-Dahlfors A, Buchan A M J, Finlay B B. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytosis in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohrwild M, Coux O, Huang H C, Moerschell R P, Yoo S J, Seol J H, Chung C H, Goldberg A L. HslV-HslU: a novel ATP-dependent protease complex in Escherichia coli related to the eukaryotic proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5808–5813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schweder T, Lee K H, Lomovskaya O, Martin A. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (ςs) by ClpXP protease. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:470–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.470-476.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strauch K L, Johnson K, Beckwith J. Characterization of degP, a gene required for proteolysis in the cell envelope and essential for growth of Escherichia coli at high temperature. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2689–2696. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2689-2696.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sukupolvi S, Edelstein A, Rhen M, Normark S J, Pfeifer J D. Development of a murine model of chronic Salmonella infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:838–842. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.838-842.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sydenham M, Douce G, Bowe F, Ahmed S, Chatfield S, Dougan G. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium surA mutants are attenuated and effective live oral vaccines. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1109–1115. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1109-1115.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tagawa Y, Sekikawa K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in IFN-gamma(−/−) mice, but not in TNF-alpha(−/−) mice: role for IFN-gamma in activating apoptosis of hepatocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:1418–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taniguchi T, Takata M, Ikeda A, Momotani E, Sekikawa K. Failure of germinal center formation and impairment of response to endotoxin in tumor necrosis factor alpha-deficient mice. Lab Investig. 1997;77:647–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Umezawa K, Akaike T, Fujii S, Suga M, Setoguchi K, Ozawa A, Maeda H. Induction of nitric oxide synthesis and xanthine oxidase and their roles in the antimicrobial mechanism against Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2932–2940. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2932-2940.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Volker, U., S. Engelmann, B. Maul, S. Riethdorf, A. Volker, R. Schmid, M. Hiltraut, and M. Hecker. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 140:741–752. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Webb C, Moreno M, Wilmes-Riesenberg M, Curtiss III R, Foster J W. Effects of DksA and ClpP protease on sigma S production and virulence in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:112–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto T, Hanawa T, Ogata S, Kamiya S. Identification and characterization of the Yersinia enterocolitica gsrA gene, which protectively responds to intracellular stress induced by macrophage phagocytosis and to extracellular environmental stress. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2980–2987. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2980-2987.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamamoto T, Hanawa T, Murayama S Y, Ogata S. Isolation of thermosensitive mutants of Yersinia enterocolitica by transposon insertion. Plasmid. 1994;32:238–243. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]