Abstract

Background:

Medicare Part D medication therapy management (MTM) includes an annual comprehensive medication review (CMR) as a strategy to mitigate suboptimal medication use in older adults.

Objectives:

To describe the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries who were eligible, offered, and received a CMR in 2013 and 2014 and identify potential disparities.

Methods:

This nationally representative cross-sectional study used a 20% random sample of Medicare Part A, B, and D data linked with Part D MTM files. A total of 5,487,343 and 5,822,188 continuously enrolled beneficiaries were included in 2013 and 2014, respectively. CMR use was examined among a subset of 620,164 and 669,254 of these beneficiaries enrolled in the MTM program in 2013 and 2014. Main measures were MTM eligibility, CMR offer, and CMR receipt. The Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use informed covariates selected.

Results:

In 2013 and 2014, 505,658 (82%) and 649,201 (97%) MTM eligible beneficiaries were offered a CMR, respectively. Among those, CMR receipt increased from 81,089 (16%) in 2013 to 119,181 (18%) in 2014. The mean age of CMR recipients was 75 years (±7) and the majority were women, White, and without low-income status. In 2014, lower odds of CMR receipt were associated with increasing age (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.99 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.994–0.995), male sex (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.926–0.951), being any non-White race/ethnicity except Black, dual-Medicaid status (OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.626–0.650), having a hospitalization (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.839–0.893) or emergency department visit (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.658–0.686), and number of comorbidities (OR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.896–0.905).

Conclusions:

CMR offers and completion rates have increased, but disparities in CMR receipt by age, sex, race, and dual-Medicaid status were evident. Changes to MTM targeting criteria and CMR offer strategies may be warranted to address disparities.

Keywords: Medication therapy management, Comprehensive medication review, Medicare Part D, Older adults

Introduction

Medication therapy problems (MTPs) in older adults (≥65 years) are pervasive and include unnecessary medications, need for additional medications, incorrect dosage, ineffective medications, polypharmacy, adverse medication events, and poor adherence.1–5 Older adults also have age-related physiological changes, greater number of comorbidities, and frailty, further increasing their risk for MTPs, including medication-related adverse events.6 These potentially preventable adverse drug events contribute to increasing emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and avoidable healthcare costs.7–9

Medication therapy management (MTM), including comprehensive medication reviews (CMRs), is one strategy to optimize medication use, mitigate MTPs, and reduce health care costs. A CMR involves a review of all medications, development of a medication action plan to resolve problems and patient concerns, creation of a personalized medication list along with patient medication education, and referral for other services when necessary.10 MTM programs, including an annual CMR, are a required benefit for Medicare Part D beneficiaries meeting eligibility requirements based upon number of medications, chronic diseases, and Part D drug costs.11 A health plan’s success at delivering annual CMRs to eligible beneficiaries became a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Star Ratings quality measure in 2016.12,13

Studies evaluating MTM and CMR delivery are generally based in a single academic health setting, employee health program, pharmacy benefit plan, state, university, or community-based program.1,14–17 Therefore, results are often not generalizable beyond the populations and plans included. One of the larger studies to examine potential differences in MTM value used claims data from a large pharmacy benefit manager to examine risk for MTPs across different patient groups. This study found that the number of MTPs was higher for females, those with lower median household incomes, and all race minorities except Asians compared to Whites.15 This study also found that prior outpatient visits, ED visits, and hospitalizations were also associated with a 23–44% increase in MTPs.15 Additional work examining patterns of MTM eligibility have shown that non-Hispanic Black beneficiaries and Hispanics may be less likely to meet MTM eligibility criteria than White beneficiaries18 However, these data are based on eligibility and do not necessarily reflect differences in the actual offer of CMRs and receipt of this health service once a patient is enrolled in MTM.

The authors are unaware of any studies that have documented the delivery of CMR services among a nationally representative population of older adults enrolled in the MTM program. Nationally representative estimates of the characteristics of older adults that are offered and receive CMRs are important to identify and address potential disparities in the delivery of MTM services by age, race, sex, and income. With the 2017 release by CMS of the 2013 and 2014 Part D MTM files, an opportunity exists to examine patterns of MTM eligibility, CMR offer, and CMR receipt which will fill these critical gaps.19 The objectives of this study, therefore, are to describe the characteristics of older adult Medicare beneficiaries who were eligible, offered, and received a CMR in 2013 and 2014 and identify potential disparities in the delivery of CMR as part of Medicare Part D MTM programs.

Methods

Study design

This study used a cross-sectional study design to compare characteristics of different Medicare populations’ eligibility for MTM, CMR offer, and CMR receipt in 2013 and 2014.

Data Sources

A random 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries’ Parts A, B, and D data for calendar years 2013 and 2014 was obtained. In addition, a 100% sample of the newly released Part D MTM files for 2013 and 2014 was obtained. This resource, containing 2013 and 2014 MTM data for Medicare beneficiaries, was released by CMS for the first time in 2017, with future years of data being available at later dates.19 These files contain information related to MTM enrollment, the provider of CMR services, dates of CMR receipt, the type of CMR provider, dates of CMR offer, and reasons for declining CMR services. In addition, a number of annual summary variables are provided for each beneficiary in the MTM file such as number of MTP recommendations made to prescribers and number of MTPs resolved with prescribers within each year.19 The MTM data files were merged with Medicare claims data and Medicare enrollment tables for the 20% random sample of beneficiaries to capture MTM delivery in this population.

Patient population

Beneficiaries were eligible for inclusion if they were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D for all 12 months of each calendar year. This study focuses specifically on the delivery of CMRs in older adult populations, excluding individuals age 64 and younger and beneficiaries eligible for Medicare due to end-stage renal disease or other disability.

Variables

The Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use was used as a conceptual model to group variables into predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics.20–22 Andersen’s model posits a process whereby predisposing characteristics predict differences in the enabling ability of a person to receive health services. This enabling ability is predictive of an individual’s need, or evaluated health status as determined by a healthcare professional, for services which ultimately predicts whether they receive health services (e.g., CMR).21,22

For the purposes of this project, predisposing characteristics included age as a continuous variable, sex (male/female), and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, Native American, and other). Enabling resources included income assistance status for Medicare enrollment (Medicare/Medicaid dual enrollment, qualified Medicare beneficiary enrollment, specified low-income Medicare beneficiary enrollment, or no income assistance),23 urban residence (defined as rural/urban continuum codes with populations of 250,000 or more),24 and geographic region (categorized as North East, South, Midwest, West, and other). Given the unique benefit design of Part D, in which patient out-of-pocket copayment rates vary at different levels of prescription spend, MTM delivery was examined across copayment status. Copayment status was defined as the maximum level of the Part D benefit achieved throughout the calendar year from catastrophic coverage, prescription use reaching the coverage gap (i.e., “donut hole”), to prescription use not reaching the coverage gap.

Finally, a number of different characteristics associated with the need for CMR including history of any inpatient hospitalization or ED visits within the year were included. The burden of health conditions using the Elixhauser Index25 and a count of the number of therapeutic drug classes used each year was also examined.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe three different comparisons of Medicare beneficiary cohorts in both 2013 and 2014. First, beneficiaries enrolled in MTM were compared to those not enrolled. Second, among the subset of beneficiaries enrolled in MTM, those offered a CMR to those not offered a CMR were compared. Third, among those offered a CMR, those receiving versus not receiving a CMR were compared. A small number of beneficiaries (569 and 215 in 2013 and 2014, respectively) received a CMR regardless of any record of CMR offer. Given CMR receipt, an assumption of an offer was made, even if not documented, and thus, these individuals were categorized as both being offered and receiving a CMR. Bivariable statistics were used to examine if there were differences across each of these three cohorts. Two-tailed t-tests were used to compare continuous variables and chisquare tests for categorical variables.

To better understand the relationship of predisposing, enabling, and need variables on the three outcomes, multivariable logistic regression was used to identify predictors for all three outcomes (i.e., MTM enrollment, CMR offer, CMR receipt). Following Andersen’s model, hierarchical models first including predisposing, then enabling, then need characteristics were used. The purpose of hierarchical modeling was to examine the impact of adding enabling and need variables on point estimates for variables representative of potential disparity in CMR delivery, such as age, sex, race and low-income enrollment status. All statistics were deemed significant at an a priori alpha of 0.05. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota.

Results

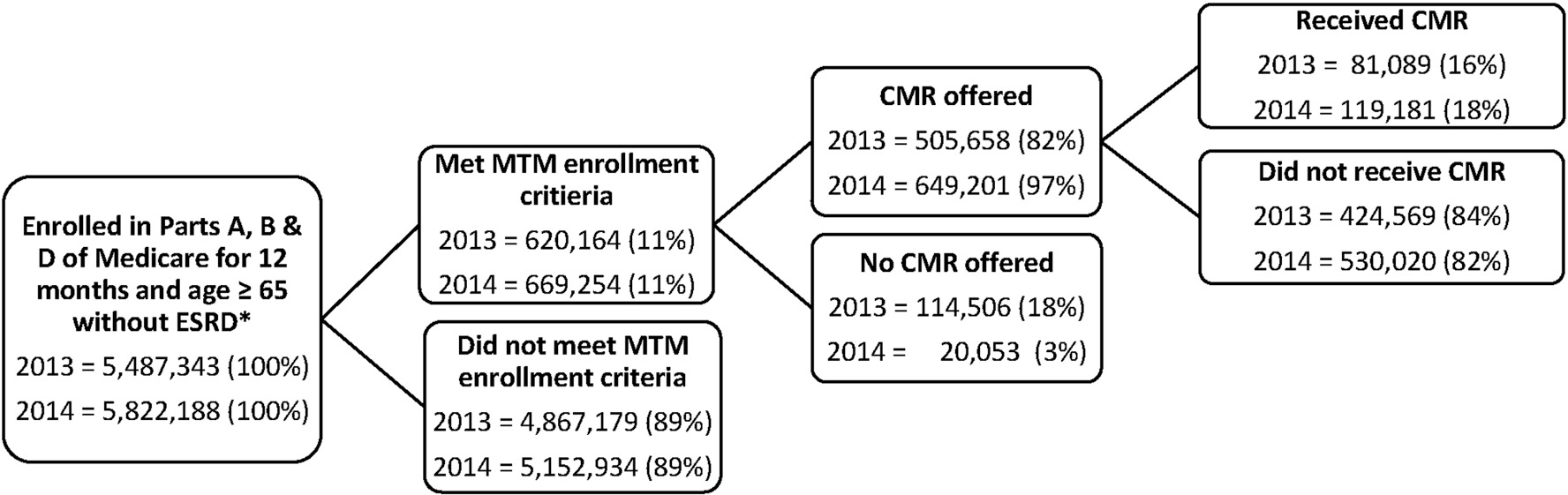

A total of 5,487,343 beneficiaries in 2013 and 5,822,188 in 2014 met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In both years, 11% of continuously enrolled older adults in Medicare met MTM enrollment criteria. Further, both CMR offer rates and CMR receipt increased over the two years. Among eligible older adults offered a CMR, CMR receipt was 16% (n = 81,089) in 2013 and increased to 18% (n = 119,181) in 2014. Overall, predictors of MTM eligibility, CMR offer, and CMR receipt were similar between 2013 and 2014. Given considerations of space, results are only presented for 2014. However, when meaningful differences between years exist, they are noted.

Fig. 1.

Older adult Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in medication therapy management (MTM), offered a comprehensive medication review (CMR), and receiving a CMR in 2013 and 2014.

*ESRD = End-stage renal disease

Predisposing characteristics

The average age of beneficiaries, approximately 76 years, was similar across cohorts (Table 1). The majority of beneficiaries enrolled in MTM and offered a CMR were female (62%) and White (74%), and approximately 11% were Black, 3% were Asian, and 11% were Hispanic. Among those offered a CMR, a higher proportion of beneficiaries received a CMR if they reported their race/ethnicity as Black (13% vs. 10%) or Hispanic (11% vs. 10%) compared to those who reported being White, Asian, North American Native, and other race/ethnicity (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2014 older adult Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in MTM, offered a CMR, and received a CMR.

| MTM Enrollmenta | CMR Offera | CMR Receiveda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Not Enrolled | Enrolled | No CMR Offer | CMR Offer | No CMR | CMR Received | |

|

|

||||||

| (n = 5,152,934) | (n = 669,254) | (n = 20,053) | (n = 649,201) | (n = 530,020) | (n = 119,181) | |

|

| ||||||

| Predisposing Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age, Mean (SD), years | 75.5 (7.5) | 75.9 (7.3) | 76.1 (7.3) | 75.9 (7.3) | 76.0 (7.4) | 75.4 (6.9) |

| Male, No. (%) | 2,067,474 (40.1) | 257,828 (38.5) | 7,654 (38.2) | 250,174 (38.5) | 205,780 (38.8) | 44,394 (37.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 4,017,480 (78.0) | 494,791 (73.9) | 12,481 (62.2) | 482,310 (74.3) | 396,331 (74.8) | 85,979 (72.1) |

| Black | 425,510 (8.3) | 71,475 (10.7) | 3,257 (16.2) | 68,218 (10.5) | 52,581 (9.9) | 15,637 (13.1) |

| Asian | 171,763 (3.3) | 20,341 (3.0) | 542 (2.7) | 19,799 (3.1) | 17,151 (3.2) | 2,648 (2.2) |

| Hispanic | 444,331 (8.6) | 72,610 (10.9) | 3,512 (17.5) | 69,098 (10.6) | 55,810 (10.5) | 13,288 (11.2) |

| North American Native | 13,718 (0.3) | 2,261 (0.3) | 43 (0.2) | 2,218 (0.3) | 1,893 (0.4) | 325 (0.3) |

| Other/Unknown | 80,132 (1.6) | 7,776 (1.2) | 218 (1.1) | 7,558 (1.2) | 6,254 (1.2) | 1,304 (1.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Enabling Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Income Based Enrollment Status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Dual Medicaid Enrollment | 596,541 (11.6) | 150,074 (22.4) | 4,237 (21.1) | 145,837 (22.5) | 124,192 (23.4) | 21,645 (18.2) |

| Qualified Medicare Beneficiary | 121,802 (2.4) | 21,732 (3.2) | 695 (3.5) | 21,037 (3.2) | 16,309 (3.1) | 4,728 (4.0) |

| Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary | 84,984 (1.7) | 17,397 (2.6) | 618 (3.1) | 16,779 (2.6) | 12,641 (2.4) | 4,138 (3.5) |

| No Low Income Subsidy | 4,349,607 (84.4) | 480,051 (71.7) | 14,503 (72.3) | 465,548 (71.7) | 376,878 (71.1) | 88,670 (74.4) |

| Copayment Status during Year, No. (%) | ||||||

| Catastrophic Coverage | 173,425 (3.4) | 148,283 (22.2) | 2,476 (12.4) | 145,807 (22.5) | 118,921 (22.4) | 26,886 (22.6) |

| Coverage Gap Exposure | 541,873 (10.5) | 238,809 (35.7) | 3,703 (18.5) | 235,106 (36.2) | 188,944 (35.7) | 46,162 (38.7) |

| No Coverage Gap Exposure | 4,437,636 (86.1) | 282,162 (42.2) | 13,874 (69.2) | 268,288 (41.3) | 222,155 (41.9) | 46,133 (38.7) |

| Geographic Region, No. (%) | ||||||

| North East | 968,186 (18.8) | 120,372 (18.0) | 1,680 (8.4) | 118,692 (18.3) | 97,386 (18.4) | 21,306 (17.9) |

| South | 1,799,667 (34.9) | 274,462 (41.0) | 11,114 (55.4) | 263,348 (40.6) | 214,820 (40.5) | 48,528 (40.7) |

| Midwest | 1,141,975 (22.2) | 155,654 (23.3) | 3,638 (18.1) | 152,016 (23.4) | 128,318 (24.2) | 23,698 (19.9) |

| West | 1,139,707 (22.1) | 106,337 (15.9) | 2,232 (11.1) | 104,105 (16.0) | 80,754 (15.2) | 23,351 (19.6) |

| Other | 103,399 (2.0) | 12,429 (1.9) | 1,389 (6.9) | 11,040 (1.7) | 8,742 (1.7) | 2,298 (1.9) |

| Urban Residence, No. (%) | 4,259,695 (82.7) | 546,899 (81.7) | 16,785 (83.7) | 530,114 (81.7) | 430,298 (81.2) | 99,816 (83.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Need Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Any Hospitalization, No. (%) | 447,615 (8.7) | 114,329 (17.1) | 1,738 (8.7) | 112,591 (17.3) | 100,383 (18.9) | 12,208 (10.2) |

| Any ED Visit, No. (%) | 626,297 (12.2) | 121,330 (18.1) | 1,691 (8.4) | 119,639 (18.4) | 105,675 (19.9) | 13,964 (11.7) |

| Hospitalizations, Mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.48) | 0.3 (0.80) | 0.2 (0.66) | 0.3 (0.81) | 0.3 (0.85) | 0.2 (0.60) |

| ED Visits, Mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.68) | 0.3 (0.94) | 0.2 (0.73) | 0.3 (0.94) | 0.3 (0.98) | 0.2 (0.74) |

| Elixhauser Conditions, Mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.50) | 1.5 (2.62) | 0.7 (2.06) | 1.5 (2.63) | 1.7 (2.71) | 0.9 (2.14) |

| Elixhauser Admission Weight, Mean (SD) | 3.0 (9.24) | 8.1 (16.04) | 4.0 (12.42) | 8.2 (16.12) | 8.9 (16.69) | 5.0 (12.79) |

| Elixhauser Mortality Weight, Mean (SD) | 1.1 (4.68) | 2.4 (7.08) | 1.2 (5.13) | 2.4 (7.13) | 2.7 (7.44) | 1.4 (5.40) |

| Therapeutic Drug Classes, Mean (SD) | 7.2 (4.79) | 14.4 (5.47) | 11.4 (6.14) | 14.5 (5.42) | 14.5 (5.47) | 14.9 (5.17) |

| Specific Elixhauser Conditions, No. (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 311,133 (6.0) | 154,829 (23.1) | 1,952 (9.7) | 152,877 (23.5) | 134,837 (25.4) | 18,040 (15.1) |

| Hypertension | 834,790 (16.2) | 192,078 (28.7) | 2,624 (13.1) | 189,454 (29.2) | 167,517 (31.6) | 21,937 (18.4) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 120,992 (2.4) | 57,449 (8.6) | 898 (4.5) | 56,551 (8.7) | 50,485 (9.5) | 6,066 (5.1) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 190,653 (3.7) | 71,291 (10.7) | 1,090 (5.4) | 70,201 (10.8) | 61,360 (11.6) | 8,841 (7.4) |

| Depression | 105,003 (2.0) | 36,445 (5.4) | 688 (3.4) | 35,757 (5.5) | 31,799 (6.0) | 3,958 (3.3) |

Chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables comparing enrolled in MTM vs. not enrolled, offered a CMR vs. not offered, and CMR received vs. not received were all significant at p < 0.001.

Increasing age was a significant predictor for enrollment in MTM (adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 95% confidence intervals (CI)) AOR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.001–1.002)), but was associated with lower odds of CMR offer and CMR receipt (Table 2). Older adult beneficiaries who were Black, Hispanic, or North American Native had higher odds of MTM enrollment compared to Whites, but eligible Black and Hispanic older adults had lower odds of a CMR offer. Only older adult Black beneficiaries had higher odds of receiving a CMR (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.417–1.475) compared to White beneficiaries in 2014. In 2013, both older adult Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had higher odds of receiving a CMR compared to older adult White beneficiaries.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Modeling: Predictors of MTM enrollment, CMR Offer, and CMR Receipt in Older Adult Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014.

| MTM Enrollment | CMR Offer | CMR Receipt | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| AOR (95%CI)a | AOR (95%CI)a | AOR (95%CI)a | |

|

|

|||

| (n = 5,822,188)b | (n = 669,254)c | (n = 649,201)d | |

|

| |||

| Predisposing Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Age | 1.00 (1.001, 1.002) | 0.99 (0.992, 0.996) | 0.99 (0.994, 0.995) |

| Male | 1.23 (1.222, 1.238) | 1.05 (1.024, 1.087) | 0.93 (0.926, 0.951) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Black | 1.43 (1.417, 1.446) | 0.73 (0.701, 0.762) | 1.45 (1.417, 1.475) |

| Asian | 1.01 (0.994, 1.031) | 0.92 (0.841, 1.011) | 0.64 (0.610, 0.665) |

| Hispanic | 1.25 (1.235, 1.263) | 0.72 (0.686, 0.753) | 0.97 (0.944, 0.988) |

| North American Native | 1.09 (1.033, 1.151) | 1.10 (0.815, 1.503) | 0.84 (0.741, 0.942) |

| Other/Unknown | 0.99 (0.965, 1.020) | 0.89 (0.779, 1.028) | 0.90 (0.850, 0.960) |

|

| |||

| Enabling Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Income Based Enrollment | |||

| No Low Income Subsidy | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary | 0.77 (0.759, 0.787) | 0.76 (0.705, 0.829) | 1.08 (1.048, 1.123) |

| Qualified Medicare Beneficiary | 0.93 (0.909, 0.946) | 0.68 (0.623, 0.739) | 1.18 (1.136, 1.224) |

| Dual Medicaid Enrollment | 0.69 (0.682, 0.694) | 0.48 (0.457, 0.497) | 0.64 (0.626, 0.650) |

| Copayment Status During Year | |||

| No Coverage Gap | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Coverage Gap Exposure | 3.71 (3.686, 3.737) | 3.04 (2.923, 3.156) | 1.27 (1.254, 1.291) |

| Catastrophic Coverage | 4.20 (4.158, 4.241) | 2.27 (2.158, 2.380) | 1.23 (1.202, 1.249) |

| Geographic Region | |||

| North East | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| South | 1.01 (1.001, 1.018) | 0.35 (0.328, 0.365) | 0.92 (0.902, 0.936) |

| Midwest | 1.23 (1.222, 1.245) | 0.59 (0.555, 0.626) | 0.86 (0.845, 0.882) |

| West | 0.81 (0.798, 0.815) | 0.71 (0.661, 0.753) | 1.36 (1.330, 1.388) |

| Other | 0.63 (0.611, 0.641) | 0.10 (0.095, 0.113) | 0.83 (0.786, 0.871) |

| Urban Residence | 1.02 (1.014, 1.030) | 0.94 (0.904, 0.979) | 1.05 (1.029, 1.066) |

|

| |||

| Need Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Any Hospitalization | 0.54 (0.528, 0.543) | 0.84 (0.782, 0.911) | 0.87 (0.839, 0.893) |

| Any ED Visit | 0.63 (0.622, 0.633) | 1.44 (1.364, 1.522) | 0.67 (0.658, 0.686) |

| Elixhauser Conditions (sum) | 1.07 (1.064, 1.069) | 1.08 (1.063, 1.090) | 0.90 (0.896, 0.905) |

| Therapeutic Drug Classes (sum) | 1.24 (1.237, 1.238) | 1.12 (1.115, 1.122) | 1.05 (1.045, 1.048) |

AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio, 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Likelihood ratio for the model probability to be enrolled in MTM; χ2 = 1158113, p < 0.0001. Pseudo R2 = 0.28.

Likelihood ratio for the model probability to be offered a CMR if enrolled in MTM; χ2 = 18499, p < 0.0001. Pseudo R2 = 0.10.

Likelihood ratio for the model probability to receive a CMR if offered; χ2 = 20687, p < 0.0001. Pseudo R2 = 0.03.

Enabling characteristics

A higher proportion in the MTM enrolled group were dual-Medicaid enrollees or had low-income assistance versus those not enrolled (Table 1). However, a lower proportion of dual-Medicaid enrolled older adults received a CMR among those offered a CMR (18% vs. 23%, p < 0.001). Likewise, more beneficiaries in the MTM enrolled group entered the coverage gap (36% vs. 11%) or catastrophic coverage phase (22% vs. 3%) than the non-enrolled group (p < 0.001). Across all groups, approximately 80% of the older adults Medicare beneficiaries resided in an urban setting.

Older adults enrolled in low-income based Medicare programs had lower odds of MTM enrollment and CMR offer (Table 2). However, only those with dual Medicaid enrollment had 0.64 times lower odds of CMR receipt compared to those not in low-income based enrollment (95% CI: 0.626–0.650). Coverage gap exposure or catastrophic coverage compared to no exposure throughout the year was associated with higher odds of MTM enrollment, CMR offer, and CMR receipt in 2014. In contrast, entering the coverage gap or catastrophic coverage was associated with lower odds of CMR receipt in 2013. Compared to those residing in the North East, only those who resided in the West had 1.4 times higher odds of receiving a CMR (AOR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.330–1.388). Urban residence was associated with higher odds of MTM enrollment and CMR receipt in this group of older adults.

Need characteristics

Need characteristics were higher in older adults enrolled in MTM and receiving a CMR offer. A higher proportion of MTM enrolled older adults offered a CMR had a hospitalization (17% vs. 9%) or an ED visit (18% vs. 8%) during the year compared to those without a CMR offer (both p < 0.001, Table 1). However, among beneficiaries offered a CMR, actual CMR receipt was lower in older adults with a hospitalization (10% vs. 19%) or ED visit (12% vs. 20%, both p < 0.001). Likewise, CMR receipt was lower in older adults with diabetes (15% vs. 25%), hypertension (18% vs. 32%), and congestive heart failure (5% vs. 10%) compared to those not receiving a CMR with these comorbidities (all p < 0.001).

A hospitalization during the year was associated with lower odds of MTM enrollment, CMR offer, and CMR receipt (AOR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.839–0.893) (Table 2). Those with an ED visit had lower odds of MTM enrollment and CMR receipt (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.622–0.633, AOR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.658–0.686, respectively), but 1.4 times higher odds of CMR offer (AOR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.364–1.522). Increasing number of comorbidities was associated with higher odds of MTM enrollment and CMR offer, but with lower odds of CMR receipt (AOR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.896–0.905). Increasing number of therapeutic drug classes was associated with higher odds of MTM enrollment, CMR offer, and CMR receipt in this group of older adult beneficiaries.

Discussion

This study provides the first nationally representative estimates of the delivery of MTM through Medicare Part D. Disparities in older adults’ CMR receipt by age, sex, race, and the low-income status of Medicare-Medicaid enrollees were observed. Specifically for predisposing characteristics, Black older adults were more likely to receive a CMR compared to White older adults, whereas Asian, Native American Indian, and Hispanic older adults were less likely. Additional predisposing characteristics of increasing age and sex (men) were predictors of being less likely to receive a CMR. For enabling characteristics, older adult Medicare-Medicaid enrollees and those living in the South, Midwest, or other geographic regions of the United States compared to the North East were less likely to receive a CMR.

In contrast to retrospective analyses of Medicare beneficiaries in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey,26,27 this study found that a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic older adults were likely to be enrolled in MTM. This study used the CMS MTM research files, including information reported from Part D prescription drug plans about actual CMR receipt, as opposed to survey data and examined the enabling characteristic of income based enrollment in Medicare Part D. This study observed that older adults that qualified for income-based enrollment were less likely to be enrolled in MTM, receive a CMR offer, and that only older adult dual Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries were less likely to receive a CMR. It is possible that MTM services, including CMRs, may have been provided to dual eligible beneficiaries by Medicaid managed care plans, fee-for-service programs, or through grant funding,28 potentially accounting for low receipt of CMRs within this group. Further research is warranted to examine the impact and interplay between predisposing and enabling characteristics with different MTM programs for low-income older adults.

The relationship between the need characteristics of ED visits and hospitalizations with CMR receipt is complex. While older adults with an ED visit or increased number of comorbidities were more likely to be offered a CMR, they appeared to be less likely to actually receive a CMR. Older adults with a hospitalization were less likely to be MTM eligible and receive a CMR once offered. ED and hospital visits represent an institutional visit followed by a care transition to another setting. Given that the risk for MTPs increases after a transition of care or with increasing medical complexity,29,30 the low receipt of CMR services among beneficiaries who had been hospitalized or had an ED visit may be of concern. Medicare Part D MTM programs may want to consider care transitions as a specific CMR targeting criteria and engagement strategies for their beneficiaries.

These findings are important, as previous studies evaluating the impact of MTM on the need characteristics of hospitalization and ED utilization resulted in mixed findings. For example, multiple telephonic MTM intervention studies found no significant difference in 30-day and 60-day hospitalization/ED utilization rates compared to usual care.31–36 Similarly, a systematic review of outpatient MTM intervention studies found insufficient evidence to suggest differences in health outcomes.37 In contrast, studies including sub-analyses of patients with specific characteristics, such as low baseline risk,31,32 diabetes,38 and heart failure39 revealed lower odds of hospitalization compared to usual care. Additional research using these MTM delivery files to examine which populations with different need characteristics experience the greatest benefit from a CMR and timing of CMR delivery after a care transition is suggested.

This study indicated that almost all MTM enrolled older adults were offered a CMR in 2014, but only about 1 in 5 received a CMR. While Part D prescription drug plan Star Ratings’ CMR completion rate increased from 2016 (15%) to 2018 (33%), there is still continued need for plans to improve their rates and reach of CMR delivery.40 As health plans are evaluated against this measure, interventions to increase CMR uptake have the potential for widespread medication use improvement in older adults.

Although MTM has been available through Medicare Part D since 2006, there remains a lack of familiarity and understanding of MTM services and CMRs among MTM-enrolled beneficiaries.41,42 This has strong implications for healthcare providers caring for older adults and Medicare Part D plans around potential CMR messaging strategies to increase uptake. Studies have indicated that having a physician or pharmacist recommend a CMR, providing the CMR in the older adults’ usual pharmacy, higher patient perceived susceptibility to MTPs, and knowing a CMR’s cost improves a patient’s decision to receive a CMR.43,44 In addition, scripted language to increase CMR uptake has been used successfully to educate older adults on the benefits and eligibility for MTM.45,46 Given the low rates of CMR receipt (16–18%) in this study, alternative messaging and techniques may need to be explored to encourage CMR receipt and improve CMR completion rates, particularly among vulnerable, high-risk populations. Future research is warranted on how CMR completion rates change over time and how frequency of delivery and reasons for declining CMR impact medication and health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As a secondary data analysis, this study was limited to the available data. Additional variables that might have been of interest for analysis but were unavailable to the study team included socioeconomic information such as income and education. Additionally, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries enrolled through part C were not included and estimates cannot be generalized to this population. Information on how a CMR offer was made or the quality of that offer was not available; only information about how the CMR was delivered. For instance, a mailed letter describing the service compared to a face-to-face description may affect uptake and CMR receipt.47 Finally, MTM data from 2013 to 2014 calendar years was used which may not apply to current CMS MTM eligibility criteria (e.g., changes in the annual drug costs eligibility threshold) or Star Ratings Measures. These results, however, raise important questions for consideration in future years.

Conclusions

CMR offer and completion rates increased from 2013 to 2014, but disparities in CMR receipt by predisposing and enabling characteristics in older adults were observed by age, sex, race, and dual-Medicaid status. Older adults with a need characteristic of a hospitalization, ED visit, and higher number of comorbidities were also less likely to receive a CMR indicating that those with a higher need for a CMR may not receive one. Changes to MTM targeting criteria and CMR offer strategies may be warranted to address potential disparities in the delivery of this service and the targeting of patients with greatest need. Future work should examine how receipt of CMR changes over time and if these observed predisposing, enabling, and need disparities persist.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Eric Berger, MS, for programming the tables and data to support this project.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Dr. Coe is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR002241. Dr. Adeoye-Olatunde is supported by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Award Number TL1TR001107 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Farris is serving as a paid consultant for QuiO, New York, NY.

Dr. Snyder is serving as a paid consultant to Westat for an evaluation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Part D Enhanced Medication Therapy Management program.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Antoinette B. Coe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Omolola A. Adeoye-Olatunde: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Deborah L. Pestka: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Margie E. Snyder: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Alan J. Zillich: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Karen B. Farris: Writing - review & editing, Conceptualization. Joel F. Farley: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Previous presentation: This research was presented at the American Pharmacists Association Annual Meeting and Exposition, Seattle, WA, March 22, 2019.

References

- 1.Caffiero N, Delate T, Ehizuelen MD, Vogel K. Effectiveness of a clinical pharmacist medication therapy management program in discontinuation of drugs to avoid in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(5):525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray SL, Marcum ZA, Schmader KE, Hanlon JT. Update on medication use quality and safety in older adults, 2017. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(12):2254–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohman MC, Cotton BP, Zagaria AB, et al. Hospitalization risk and potentially inappropriate medications among Medicare home health nursing patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maust DT, Gerlach LB, Gibson A, et al. Trends in central nervous system-active polypharmacy among older adults seen in outpatient care in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):583–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ElDesoky ES. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic crisis in the elderly. Am J Ther. 2007;14(5):488–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, et al. US emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events, 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2115–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Pharmacists Association and National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model version 2.0. https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/core_elements_of_an_mtm_practice.pdf; March 2008, Accessed date: 24 May 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). HHS. Medicare program; Medicare prescription drug benefit, Final rule. Fed Regist. 2005;70:4193–4585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare health & drug plan 2013 Part C & Part D display measure technical notes. https://www.cms.gov; 2013, Accessed date: 22 February 2019.

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact sheet – 2016 star ratings. https://www.cms.gov; 2016, Accessed date: 22 February 2019.

- 14.Buhl A, Augustine J, Taylor AM, et al. Positive medication changes resulting from comprehensive and noncomprehensive medication reviews in a Medicare Part D population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(3):388–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Yang J, Stockl KM, et al. Evaluation of eligibility criteria used to identify patients for medication therapy management services: a retrospective cohort study in a Medicare Advantage Part D population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore JM, Shartle D, Faudskar L, et al. Impact of a patient-centered pharmacy program and intervention in a high-risk group. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(3):228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moczygemba LR, Barner JC, Gabrillo ER. Outcomes of a Medicare Part D telephone medication therapy management program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(6):e144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Shih YC, Qin Y, et al. Trends in Medicare Part D medication therapy management eligibility criteria. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(5):247–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Part D medication therapy management data file. 22 February 2019. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/part-d-mtm-data-file. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare savings programs. https://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/get-help-paying-costs/medicare-savings-programs, Accessed date: 4 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Bureau of Economic Research. CMS’s SSA to FIPS CBSA and MSA county crosswalk. http://www.nber.org/data/cbsa-msa-fips-ssa-county-crosswalk.html, Accessed date: 4 March 2019.

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Mullins CD, Brown LM, et al. Disparity implications of Medicare eligibility criteria for medication therapy management services. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):1061–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Qiao Y, Spivey CA, et al. Disparity implications of proposed 2015 Medicare eligibility criteria for medication therapy management services. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2016;7(4):209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neyarapally GA, Smith MA. Variability in state Medicaid medication management initiatives. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(1):214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zillich AJ, Snyder ME, Frail CK, et al. A randomized, controlled pragmatic trial of telephonic medication therapy management to reduce hospitalization in home health patients. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1537–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gernant SA, Snyder ME, Jaynes H, et al. The effectiveness of pharmacist-provided telephonic medication therapy management on emergency department utilization in home health patients. J Pharm Technol. 2016;32(5):179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeZeeuw EA, Coleman AM, Nahata MC. Impact of telephonic comprehensive medication reviews on patient outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(2):e54–e58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haag JD, Davis AZ, Hoel RW, et al. Impact of pharmacist-provided medication therapy management on healthcare quality and utilization in recently discharged elderly patients. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(5):259–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller DE, Roane TE, McLin KD. Reduction of 30-day hospital readmissions after patient-centric telephonic medication therapy management services. Hosp Pharm. 2016;51(11):907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fennelly JE, Coe AB, Kippes KA, et al. Evaluation of clinical pharmacist services in a transitions of care program provided to patients at highest risk for readmission. J Pharm Pract. 2018 10.1177/0897190018806400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, et al. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brummel AR, Soliman AM, Carlson AM, de Oliveira DR. Optimal diabetes care outcomes following face-to-face medication therapy management services. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roughead EE, Barratt JD, Ramsay E, et al. The effectiveness of collaborative medicine reviews in delaying time to next hospitalization for patients with heart failure in the practice setting: results of a cohort study. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(5):424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pharmacy Quality Solutions. Medicare 2019 star rating threshold update https://www.pharmacyquality.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2019StarRatingThreshold4.pdf, Accessed date: 21 May 2019.

- 41.Taylor AM, Axon DR, Campbell P, et al. What patients know about services to help manage chronic diseases and medications: findings from focus groups on medication therapy management. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(9):904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandt NJ, Cooke CE. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services support for medication therapy management (enhanced medication therapy management): testing strategies for improving medication use among beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(2):153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doucette WR, Zhang Y, Chrischilles EA, et al. Factors affecting Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ decision to receive comprehensive medication reviews. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(5):482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Doucette WR. Consumer decision making for using comprehensive medication review services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2019;59(2):168–177 e165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doucette WR, Pendergast JF, Zhang Y, et al. Stimulating comprehensive medication reviews among Medicare Part D beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(6):e372–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miguel A, Hall A, Liu W, et al. Improving comprehensive medication review acceptance by using a standardized recruitment script: a randomized control trial. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huet AL, Frail CK, Lake LM, Snyder ME. Impact of passive and active promotional strategies on patient acceptance of medication therapy management services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55(2):178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]