Abstract

Medical clowns (MCs) are trained professionals who aim to change the hospital environment through humor. Previous studies focused on their positive impact and began identifying their various skills in specific situations. When placed in pediatrics, MCs face various challenges, including approaching frustrated adolescents who are unwilling to cooperate with their care, dealing with their anxious parents, and communicating in a team in the presence of other health professionals. Research that systematically describes MCs’ skills and therapeutic goals in meeting these challenges is limited. This article describes a qualitative, immersion/crystallization study, triangulating between 26 video-recorded simulations and 12 in-depth-semi-structured interviews with MCs. Through an iterative consensus-building process we identified 40 different skills, not limited to humor and entertainment. Four main therapeutic goals emerged: building a relationship, dealing with emotions, enhancing a sense of control, caring, and encouragement, and motivating treatment adherence. Mapping MCs’ skills and goals enhances the understanding of MCs’ role and actions to illustrate their unique caring practices. This clarification may help other healthcare professionals to recognize their practices and the benefits in involving them in care. Furthermore, other health professionals may apply some of the identified skills when faced with these challenges themselves.

Keywords: medical clowns, communication skills, therapeutic goals, connecting to patients, qualitative

Introduction

Medical clowns (MCs), also called hospital clowns or clown doctors, are trained professionals who aim to change the perception of the hospital environment by creating humoristic situations to elicit laughter and joy in children’s wards as well as with adults and older adults (Dionigi et al., 2014; Dionigi & Goldberg, 2019; Friedler et al., 2017; Koller & Gryski, 2008; Lalantika & Yuvaraj, 2020; Linge, 2008; Ofir et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 2007). In many cases, patients, families, and staff value MCs (Dionigi & Canestrari, 2016; Higueras et al., 2006; Schwebke & Gryski, 2003; Warren & Spitzer, 2013), especially for improving patients’ physical and mental well-being through creating an alternative atmosphere (Dionigi et al., 2014; Friedler et al., 2017; Lopes-Júnior et al., 2020; Nuttman-Shwartz et al., 2010; Weaver et al., 2007). Medical clowns entertain patients during recovery (Dionigi & Canestrari, 2016; Koller & Gryski, 2008; Ofir et al., 2016), and reduce anxiety, distress, and pain during acute care and invasive examinations (Finlay et al., 2014; Friedler et al., 2017; Kristensen et al., 2018). Furthermore, MCs assist in coping with chronic and terminal illness by improving quality of life and decreasing fear (Nuttman-Shwartz et al., 2010; Warren & Spitzer, 2011).

When placed in pediatrics where they work with sick children and adolescents and their parents, MCs face various challenges related to their care. Challenges include trying to help children and adolescents who are experiencing frustration from the illness itself and from the need to be in a new, strange, isolated environment. (Barkmann et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2021; Rennick & Rashotte, 2009; Wilson et al., 2010) Interaction with these children and adolescents is challenging as they experience distress and difficulty in dealing with painful procedures and treatments, (Kristensen et al., 2018; Rennick & Rashotte, 2009; Wilson et al., 2010) leading, at times to unwillingness to cooperate with medical teams’ recommendations (Gray et al., 2021; Holland et al., 2022). Another challenge is communicating with worried, anxious, and exhausted parents. Some parents are reluctant to let MCs enter the child’s room, hindering the MC from helping the child or adolescent as well as from helping the parent who is dealing with challenges as a caregiver. An additional challenge is the triadic nature of most pediatric medical encounters (e.g., involving a child/adolescent and a parent or another healthcare provider). Triadic interactions are difficult to handle in the small, organized, hierarchical medical setting (Gray et al., 2021). Triadic interactions have features that differ fundamentally from those of a dyad and can negatively affect communication, for example, by limiting children and adolescents’ involvement or actually excluding them from the care discussions. (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2012) These challenges are prevalent and some studies have begun to identify specific medical clowning skills that are useful in certain interactions, for example, when helping children cope with invasive procedures and in children’s rehabilitation (Gray et al., 2021; Kristensen et al., 2018). Still, MCs’ skills and related therapeutic goals require further exploration and identification, as they are considered “ill-defined in the academic literature” (Holland et al., 2022), especially when interacting with parents and in a triad with healthcare teams (Kristensen et al., 2018).

The need to learn about MCs’ skills and competencies has led to an increase in research papers, in recent years, including quantitative satisfaction surveys, case studies, storytelling, observational perspectives, and ethnographic fieldwork (Dionigi et al., 2014; Dionigi & Goldberg, 2019; Finlay et al., 2014; Friedler et al., 2017; Holland et al., 2022; Kristensen et al., 2018; Mora-Ripoll, 2010)1. These papers were very important in identifying performance arts skills among MCs (such as music, comedy, mime, magic, or puppetry) that entail cognitive distraction, humor, improvisation, imagery, and relational aspects to shift attention from pain or distress (Barkmann et al., 2013; Dionigi & Canestrari, 2016; Finlay et al., 2014; Koller & Gryski, 2008; Kristensen et al., 2018; Linge, 2008, 2013; Ofir et al., 2016; Tener et al., 2010). These efforts signify the need to move from a general description of MCs’ practices to a clearer identification of their skills—as done in other health professions, for example, the clear identification of physicians’ verbal and nonverbal communication skills (Duffy et al., 2004; Levinson et al., 2010; Little et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2011; Zulman et al., 2020).

Furthermore, there is a need to identify MCs’ motives and therapeutic goals and the skills used to achieve them. A systematic identification, focused on specific challenges, can help this art of improvisation become informed (Oakes, 2009) and can help teach other MCs to establish their high-quality practice and professional training (Dionigi & Canestrari, 2016; Finlay et al., 2014; Linge, 2008; Ofir et al., 2016; Tschiesner & Farneti, 2020). Naming the skills and understanding the goals can assist in identifying MCs different kind of “treatment” or “care.” Publishing and sharing this material with other health professionals can also potentially reduce the experiences of misunderstanding of MCs’ presence and actions. In this manner, medical staff or patients will experience their presence as less of a distraction or annoyance (Barkmann et al., 2013; Gomberg et al., 2020; Mortamet et al., 2017; van Venrooij & Barnhoorn, 2017). Thus, enhanced understanding can promote interdisciplinary teamwork and improve MCs’ integration in the medical team, without limiting their unique contribution.

Therefore, the present study focuses on qualitative in-depth systematic identification of MCs’ skills and therapeutic goals, through observing and analyzing their actions in the challenging encounters with adolescents, parents, and healthcare providers, and learning about their motives and reasoning to identify their therapeutic goals.

Method

This qualitative immersion/crystallization study (elaborated later) used triangulation (Patton, 1999). Triangulation is a methodological process that utilizes different research techniques to achieve deeper insight and understanding and enhance trustworthiness of findings and “completeness” (Adami & Kiger, 2004; Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Shih, 1998). Therefore, to identify and learn about the various skills used by MCs and to enhance our understanding of MCs’ perceptions of their role and therapeutic goals, we triangulated between the analysis of 26 video-recorded simulations of 3 challenging scenarios and 12 in-depth semi-structured interviews with participating MCs. The various medical clowning skills were identified through the video-recorded simulations. The interviews then shed light on the MCs’ perceptions of the use of and rationale behind those skills, that is, their motives and therapeutic goals.

Background, Sampling, and Participants

The MCs were trained and recruited by the Israeli non-profit Dream Doctors Project that was founded in 2002 with the mission of establishing medical clowning as an official paramedical profession. The Project trains and integrates professional MCs as members of multidisciplinary care teams. It is dedicated to improving patients’ well-being and enhancing the efficacy of healthcare delivery. As part of the training, Dream Doctors, with the Israel Center for Medical Simulation (MSR), created a simulation-based workshop focused on developing experienced MCs’ skills. Drawing on these workshops, we used purposeful sampling of maximum variation (Patton, 1999) of 26 simulations with 12 MCs (average age M = 40.8), 6 males and 6 females, working in different hospitals, to allow the identification of different skills and motives. The Sheba Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Research Tools

This study explores different MCs’ application of skills in simulations as well as their personal experiences and motives to act in such a manner as expressed in their own words in the interviews.

- (1) Analysis of video-recorded simulations: The data used in this study were based on the video-recorded simulations from the medical clowning workshop. In the workshop, experienced MCs interacted with trained actors in scenarios incorporating various clinical experiences and different participants (Issenberg et al., 2005). The chosen simulated scenarios included 3 different challenges that MCs experience frequently in pediatrics:

- (a) Meeting an adolescent girl with a serious burn injury and acute pain, who was upset and unwilling to cooperate in implementing her treatment plan (Title-“I cannot! It hurts!”). This scenario was chosen because MCs are invited to help with patients who are upset and suffering and are unwilling to cooperate with medical team recommendations (Gray et al., 2021; Holland et al., 2022).

- (b) Communicating in a triad of physiotherapist, adolescent, and MC, where the adolescent with respiratory problems is reluctant to perform prescribed physio exercises (Title-“Teamwork”).

- (c) Communicating with the mother of a (sleeping) young boy. The mother is anxious, protective, and suspicious as she is concerned about her child’s health (Title-“Don’t touch my child”).

(2) In-depth semi-structured interviews: Following analysis of the simulations and identification of the skills, we conducted individual interviews with 12 MCs who participated in the simulations. The interviews were guided by a 3-part interview guide including open-ended questions that encouraged them to share their experiences. The interview guide included, first, an invitation to share MCs’ general experiences concerning their role, goals, and professional perceptions (e.g.,“Can you tell me about your role in the hospital?”). The second included specific questions inviting them to share their use of different skills in their interactions with patients/families/medical staff. The third invited them to share their reasoning and perception of the skills and goals identified in their own simulations (e.g.,“I saw that when the patient cried, you did XXX. What were you trying to achieve?”). Probing questions were included, for example, “What did you feel/think? How do you define this skill? When and why do you use it?” Probing was intended to broaden our understanding and verify the research team’s interpretation of the simulations.

Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The original Hebrew data were translated into English after analysis and selection of quotes. When translating complex constructs or metaphors, the two lead authors consulted with a professional English editor to keep interpretations as close as possible to the sociocultural context and to ensure high interpretative and translation validity (Squires, 2008; Michael et al., 2018; van Nes et al., 2010).

The Analysis

We used immersion/crystallization analysis (Borkan, 1999; Miller & Crabtree, 1992), a thematic narrative analysis framework developed in medicine. Immersion/crystallization requires cognitive and emotional engagement, with iterative re-watching/re-reading of the data to familiarize ourselves with it (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2010a; Karnieli-Miller et al., 2010b; Karnieli-Miller et al., 2011a; Meitar et al., 2009; Miller & Crabtree, 1992). This included an inductive process allowing broader understanding of simulation content (e.g., the different types of skills and the manner, timing, and ratio of their use, i.e., immersion). This process helped identify different skills from the simulations toward creating an exhaustive codebook. We repeated the process several times to reach saturation and consensus (Karnieli-Miller, et al., 2011b; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016; Patton, 2015). Some videos were transcribed to allow clear identification of the various skills. Later, we analyzed the interviews using the same process, focusing on understanding MCs’ experiences, feelings, and thoughts for further exploration of their therapeutic goals and use of different skills.

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness, we applied several processes:

• Investigator triangulation and working as a team with diverse, relevant expertise. To differentiate our own knowledge/perceptions and the data that exist, we used investigator triangulation (Patton, 1990). A research team with diverse, relevant expertise observed the simulations. Then we met as a team. Each team member shared the skills/themes identified, leading to rich, stimulating discussion about the data, and identifying various skills. This collaboration enabled us to verify that our findings represent the phenomenon rather than our own agendas or perceptions. The ongoing discussion broadened the interpretation of the data (e.g., identifying different MCs’ goals), allowed examination of additional opinions (e.g., understanding the importance of proportionate and sensitive use of different skills), and reduced possible biases in interpreting the findings (Adami & Kiger, 2004) (e.g., a narrowed perception of the MCs’ role that was related only to humor).

• Reflective process at the end of each analysis of the simulation and interview The research team performed reflection at different stages of the study. For example, during simulation analysis, we reflected about the way that team members analyzed the simulations, to identify which situations and skills they ignored or “wrapped” together. Furthermore, at the end of each interview, the interviewer was invited to reflect on the way questions were asked, to help ensure the quality of the interview as well as to improve interviewing skills.

• Methods triangulation (Patton, 1999) This study used both simulations and interviews. Simulations allowed exploration of the actual skills used, spontaneously, when dealing with the challenges. Through the interviews, we learned about participants’ thoughts, reasoning, and past experiences that led them to choose each skill. Furthermore, the interviews offered the opportunity to perform a member check (Goldblatt et al., 2011) to verify the MCs’ perspectives concerning the goals and skills identified by the research team in the simulation analysis.

Results

The simulation and interview analysis yielded 40 specific skills used by MCs including verbal communication (e.g., anchoring, encouragement, asking about emotions, telling jokes, imaginative play) and nonverbal communication (e.g., using accessories, movement in space). The use of either one or a combination of these skills helped MCs achieve different therapeutic goals, including connecting to patients and to their wishes; dealing with patients’ emotions and difficulties; enhancing motivation for treatment adherence, and increasing a sense of control, caring, and encouragement. These therapeutic goals are connected and some skills used within them overlap. The results include a description of the primary skills identified (marked in bold), their use and rationale, under each therapeutic goal, followed by Table 1 that summarizes MCs’ therapeutic goals and skills.

Various Skills Used by MCs Divided by Therapeutic Goals

Therapeutic Goal: Connecting to Patients and to Their Wishes

Medical clowns emphasized their intention to connect with patients and their families, and truly to be there for them. When MCs enter a patient’s room, they seek ways to connect, relate, and gain the patient’s and family members’ acceptance of their presence. The MC tries to capture the patient’s attention and interest, and to gain some level of communication and cooperation. The connection is often made through anchoring, that is, the MC identifies an object, feeling, or behavior and immediately relates to it either verbally or nonverbally, to create an initial bond. The MC may comment on an accessory, for example, pointing at a box of cookies by the patient’s bed: “Woooo…who brought you these cookies?” Noticing and asking about the object initiates a conversation, enabling dialogue, even without asking permission to enter the room. Anchoring can also focus on an emotion, on patient’s nonverbal or verbal expressions, for example, “Bummer…things are bad…you are right,” openly acknowledging a feeling that others may try to ignore or change.

By connecting, MCs emphasize and give voice to the patient’s feelings and/or wishes. Medical clowns home in on the patient’s experience, through repeating or echoing the patient’s words. For example, when the physiotherapist tries to convince the patient to cooperate with an exercise using a specific device, the patient declares: “This exercise is torture.” The MC immediately repeats the word “torture!” and says “absolute torture!”

In other cases, the MC voices what the patient wants to say, but does not verbally communicate. For example, when the patient has finished an exercise, the MC immediately identifies his negative emotion toward the next exercise, turns to the physiotherapist, and asks: “That’s it, is he done? Only one more exercise left?” When the physiotherapist replies that the patient needs to do one more exercise, the MC says, in disappointment and surprise: “Another exercise?!”

Giving voice to the patient’s wishes was observed in various situations, especially at the beginning or in conflicting situations where the patient was frustrated. In some cases, MCs humorously exaggerated the patient’s struggle. For example, when patients declared refusal to cooperate with the medical team, the MC immediately took up the patient’s struggle or concern, repeating, legitimizing, and exaggerating it, as illustrated next:

Patient: “The therapist [who is not present] wants me to do stupid exercises and I can’t!”

The MC runs, opens the door, and shouts: “She is not doing those stupid exercises!”

MC: “I told them you aren’t doing it, no matter what! If necessary, we will protest… you’re not doing anything!!! Don’t worry, I’m responsible for the not doing.”

The MC assumes a role] calling the lack of willingness to cooperate as part of a (legitimate) protest, emphasizing her authority regarding “not doing.” The exaggeration can include strong expressions, such as “stupid exercises” and can progress to other dimensions of joining: “I’m not doing anything, we’re on a general strike!” The MC adopts the role of patient’s advocate: “I’ll tell them you’re never going to move,” taking the statement to the extreme.

Another skill is the use of the plural “we aren’t doing it!” to legitimize the difficulty, and to create partnership. The plural is also used to enable reassessment of the decision or difficulty, from an innocent and non-judgmental stance: “What aren’t we doing?” This allows reexamination of the conflict, inviting a discussion, this time with a supportive partner.

Medical clowns use the plural and exaggeration to emphasize that they stand behind or in front of the patient “against” others, while inviting them to laugh and look at the decision from a different perspective. For example, when the patient says: “I can’t come with you because it really hurts me, and they don’t even realize how much it hurts…,” the MC replies: “We will go together and tell them how much it hurts…we will tell them to try it themselves!” The immediate acceptance sends a clear message of partnership: The patient is no longer alone in dealing with the entire medical team or system, while ignoring the statement that she cannot go ☺.

Therapeutic Goal: Dealing with Patients’ Emotions and Difficulties.

Patients cope with various difficult emotions (as seen above) vis-à-vis the medical system and the medical experience. Medical clowns focused on relieving patients’ emotions, trying to help them overcome their difficulties and improve their coping during their hospital stay. To help patients gain relief, MCs use direct and indirect responses. Direct responses to the emotions include acknowledging patients’ feelings, using mirroring, sending a message of seeing the pain, physical touching, and providing space to share emotions and gain some catharsis. Indirect responses include allowing patients to act out their hard feelings or creating a distraction.

Medical clowns emphasize their role of being for the patient and listening to them. These skills are not classic “clownish” examples, representing MCs’ uniqueness and varied roles. As one MC said: “I am here to contain patients’, parents’, or staff’s needs, without setting time boundaries or an opinion…just being there to contain whatever needs to be contained…to allow them to share what happened to them… I am there to be a friend, to build a human connection…”

Medical clowns see themselves as “an emotional pipeline.” They invite patients and their family members to “let go” and release and vent their emotions to gain catharsis.

They can do it through music “Sometimes, people cry when I sing to them… It’s good crying, allowing them to release tension …” or as another MC said: “I did not make them laugh. I wanted them to have the opportunity to share their anger, to take it out on me…because who else can the sick adolescent take it out on? Her mother? Come, vent, scream, and curse me instead of blowing up at others…” MCs acknowledge the emotions and provide the opportunity to vent, with no harm, guilt, or shame that would have followed venting toward family members or the healthcare team.

Medical clowns focused on sending a message of seeing the pain and wanting to help relieve it, inviting the patient to share it with them. This is done with or without physical touching, verbally expressing their intent: “I’m putting my hand here [on patients’ back]. As you breathe, some of the pain will transfer to my hand.” Another example is when the MC touches the mother’s shoulders saying: “Your muscles must be stiff [from sleeping here]… Anyone who sleeps on this bed deserves a massage…” A few seconds into the message, the mother starts crying and shares her worries.

Another way in which MCs dealt with emotions was through mirroring, that is, verbally or nonverbally repeating and displaying the patient’s emotion, behavior, or thought. Using mirroring, MCs show that they “see” patients, connect to their situation, understand their emotions, and invite them to express and address them. An example of nonverbal mirroring is when the patient walks painfully and slowly, the MC mimics his condition, walking slowly beside him to connect. Or when a child sits in the corner of the room, with his hands over his mouth, refusing to take his medicine, the MC imitates his position, connecting to the disgust.

Medical clowns also verbally used reflection, direct questions, and inviting patients to discuss their feelings about their suffering and pain, for example, asking: “Don’t you like it here? Where would you like to be?” or a situation in which the MC sits down and asks: “How much does it hurt?” The patient says: “A lot.” MC: “Case? Box? Can I take some?”… putting the pain “out there” and showing willingness to take it away.

Another MC practice for dealing with emotions is trying to move patients away from them, to shift them from this state, to create a distraction, to change the atmosphere. This can be done when MCs choose to respond indirectly by diverting a patient’s attention from the negative emotion. Distraction breaks the cycle of negativity. The simulation analyses identified various distraction methods to change the atmosphere, including changing the topic/main issue of conversation by asking questions:

Patient: “I want to go home.”

MC: “Do you live far away?” “Further north, ahh right …” or

“Do you eat a lot of chocolate? When did you last get your haircut?”

The MC connects to the topic of conversation, but shifts it to other issues, away from the patient’s original statement.

Another practice included asking embarrassing questions (e.g., “Can you ask him if he has a girlfriend?”), taking the focus away from pain, suffering, disease, or the wish to leave.

In addition, MCs used accessories and gimmicks to capture patients’ attention, such as puns, metaphors, images, or changing the context of a word to distract their feelings from the therapeutic context, to transform it into something “cool” or funny. These puns and action involved much humor.

Another way that MCs try to reduce tension, pain, and unpleasantness in applying treatment is by creating a calmer, playful environment, focused on making the treatment part of a game. They draw on fantasy and imagination, for example, while the patient breathes into a water pipe, the MC relates to the noise as if produced from an aquarium, apparently mesmerized by the exotic fish. In doing so, the MC focuses on an imaginary positive experience, reducing the burden and the boredom of routine care.

In similar cases, the clown encourages cooperation through the use of accessories, for example, whenever the patient does his exercise and blows into the medical equipment, the MC presses a shining ball. The patient likes this and wants to see it shine again. The MC then says encouragingly to the patient: “Blow into the instrument and it will shine again.”

Therapeutic Goal: Enhancing Excitement and Motivation to Adhere to Treatment

Medical clowns see themselves as part of the medical team, emphasizing their professional role in the healing process, including enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment. Medical clowns encourage patients to endure treatment using various skills. Some, also mentioned above, serve as a distraction by creating an environment of success (e.g., boisterous cheering and extravagant gestures “Wow!!! Great job!” while applauding). Others include supportive statements and physical contact. Although attempting to enhance excitement and motivation regarding the treatment, MCs stage a competition. They initiate a contest with the patient to shift attention to the positive desire to win:

I heard a child screaming: “I don’t want it!!!” He sat in the corner of the room, his hand over his mouth, shouting: “I don’t want it! It’s disgusting!”…Screams… He didn’t want to take antibiotics… So, I quickly took another syringe, put it in a glass of water and pumped, as if we were having a competition to finish first. He grabbed the syringe from his mother, put it in his mouth, and squeezed. He finished before me…I walked out of the room as a loser…He won, and happily raised his hands.

Instead of a struggle and use of force, the MC makes the process seem worthwhile, encouraging the child to win. The competition allows the child to shift his stance and decide to take the medicine as quickly as possible. The MC’s “walk of shame” creates the child’s positive experience of triumph.

Proportion and sensitivity in the use of competition was crucial. An attentive MC uses competition to motivate and raise the patient’s sense of competence. Insensitive competition, through a flawless performance, generated the opposite reaction of frustration or despair.

When MCs sense patients’ lack of will or strength to continue the medical regimen, they may also initiate a negotiation, moving back and forth between the patient’s and the “treatment’s” voice:

A boy argues with the therapist and complains: “I can’t be bothered to do these exercises.”

The MC stands between them and asks the therapist: “What does he need to do?”

The therapist replies: “Twice more.”

The MC turns enthusiastically to the patient, saying: “Only twice more! Only two more! Only two more times!”

The MC turns to the therapist again: “And that’s it! And then you leave him alone because you’re being a nag! Nag, nag, nag!”

The clown turns back and advises the patient: “I would do it fast so he’ll stop nagging and you can leave…”

The boy, convinced, continues to exercise.

In addition to verbal skills, the MC uses nonverbal skills such as movement in space. When a difficulty occurred, the MC stood physically between the patient and the therapist, to stop the argument, change the atmosphere, and allow them to move forward. Moreover, when the treatment was progressing and their goal was accomplished, MCs moved aside and watched from a distance without interfering.

Medical clowns emphasized that they know how to reconcile and mediate between the staff and the child or between parents and staff—an act that may result in trust, reduced tension, and increased patient willingness to cooperate. In the situation illustrated below, the MC interrupts an argument between the patient and the physiotherapist about the number of exercises needed:

“Hold on a second…if he does it will you sign the letter [of release] and I’ll take him with me? I’ll take you somewhere…come on, let’s do it! When you’ve finished, where would you like to go? To the beach? Home? Where do you live? I have a car, I’ll take you…” At that point, the patient starts the exercise.

As seen here, although we broke the skill down to the smallest pieces, various skills are manifested almost simultaneously. The MC negotiates with the physiotherapist and then focuses on imaginary results and distractions, all employed to motivate the patient to do the exercises.

Therapeutic Goal: Enhancing Sense of Control, Caring, and Encouraging

Medical clowns pay special attention to meeting and accommodating patients’ needs in the attempt to change the difficult atmosphere and experience in the hospital. Hospitalized children become immediately subject to the system’s rules, required to adhere to a strict regime, with little control. Therefore, MCs try to help patients cope through reestablishing “the child’s control” and autonomy. The MC wishes to “elevate and empower the child…” by giving him an opportunity to choose, for example, if he wants the MC inside his room or not, and when. Medical clowns adopt an inferior position:

To show respect for the child…to give control, at least in his interactions with me…I lower myself to become less threatening…Because the patient is at the lowest status in a hospital, I place myself even lower…so he can laugh at me and build an alliance.

The MC acts on the patients’ wishes and obeys him. The MC offers an invitation and opportunity to act in whatever way the patient chooses: “To contradict what hospital is all about… The MC is unlimited—he has no time pressure and no boundaries in what he should be, feel, or say…he provides legitimacy (to acting as one wants).”

In sum, MCs use these various skills to accomplish four main therapeutic goals described above. The skills are summarized in supplement Table 1.

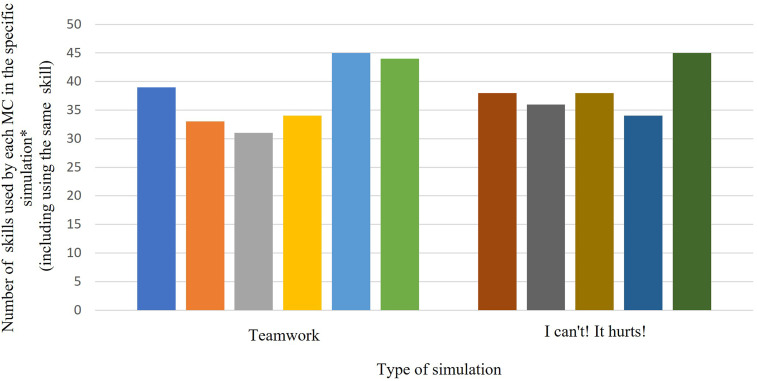

MCs Differ in the Range of Skills Used

Within the simulations, we found variance when comparing MCs’ use of skills. As seen in Figure 1, different MCs use a different range of skills to deal with the same type of simulation (similar in the challenge and time frame). One MC might use 30 skills during this challenge (some repeated), while another might apply 45 skills. In the analysis, we noticed that those with fewer skills tended to use them repetitively, even if they were unsuccessful, perhaps indicating less mastery and without many alternatives. Others, however, used various skills and accomplished more of their therapeutic goals in the encounter. Their ability to use various skills, in the simulations, allowed them to help the patient move from frustration and lack of cooperation to some relief and enhanced engagement with the MC or treatment. see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Range of skills used by different MCs in different simulations.

*The number of skills used by a MC can be more than 40, as some skills are repeated and were counted cumulatively.

Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed MCs’ skills based on analysis of their actions in simulated encounters and on their perceptions expressed in their interviews. The aim was empirical learning of MCs’ skills used and their therapeutic goals in various challenging encounters with different participants: adolescents, parents, and healthcare providers. We identified a variety of skills applied with the intent to build a relationship (connect), to deal with emotions, to enhance a sense of control and encouragement, and to promote motivation for treatment adherence. The findings of this study fit well with recent literature, indicating that MCs’ roles and goals are broad, ranging from a humanistic relationship to motivation to adhere to the treatment plan (Gray et al., 2021; Hanuka et al., 2011; Holland et al., 2022; Kontos et al., 2017). This broad range of goals requires the MCs to be flexible to adapt to different partners and situations (Holland et al., 2022) and explains the need for the various skills.

The common knowledge is that MCs focus on humor with the ultimate goal of making the patient smile (Battrick et al., 2007; Dionigi & Goldberg, 2019; Finlay et al., 2014; Friedler et al., 2017; Mora-Ripoll, 2010). However, this study showed that expressions of joy and relief were considered positive but were not the only or even the principal goal. This relates to the increased understanding that MCs have a broader function than creating humor and happiness (Grinberg, 2018; Holland et al., 2022; Koller & Gryski, 2008; Pendzik & Raviv, 2011; Warren & Spitzer, 2011) and to the concept that MCs in healthcare settings collaborate with others, to best meet patients’ and families’ needs (Gray et al., 2021) using different skills. This systematic identification of MCs’ skills demonstrates their instantaneous use of clown play (Holland et al., 2022) in response to the ideas, emotions, gestures, and movements to address various momentary needs and challenges and to achieve these various therapeutic goals.

Medical clowns’ skills and therapeutic goals that were identified seem to fit and promote the values of patient-centered care (PCC) encouraged in medicine (Epstein et al., 2005; Mead & Bower, 2000; Michael et al., 2019). Patient-centered care includes considering patients’ social, emotional, and spiritual needs through thoughtful and sensitive communication. In this study, MCs implemented various skills to allow patients to express their needs and concerns. However, while some professionals avoid uncomfortable conversations, denying patients the opportunity to express their concerns freely (Catapan et al., 2020), MCs stressed the importance of openness and expressing the patient’s “hidden agenda.” They engaged in “relational presence” (Kontos et al., 2017) with the patient/parent to respond to and express their experience. Performative arts practices seemed useful here (Butler, 2012), through the variable use of their bodies (gestures, movements, and voices) as well as performance techniques, such as singing, to create a space for expression.

Medical clowns in this study emphasized their role of being with the patient in handling the emotional difficulty or as an ally for emotional support (Gray et al., 2021; Kontos et al., 2017). Similar to other health professionals’ expressions of empathy (Kim et al., 2000; Zulman et al., 2020), MCs acknowledged emotions through direct responses (e.g., naming and legitimizing the emotion) and indirect responses. Using various skills, they expressed immediate acceptance of the patient and his/her emotional state, including themselves in the patient’s experience by speaking in the first-person plural, or what Kristensen et al. (2018) refers to as the process of WE (are in this together), bringing some relief. Furthermore, MCs in this study demonstrated the nonjudgmental invitation to the patient to observe the emotion from outside and the MCs’ empathy that may assist patients’ ability to release negative emotions.

Another aspect of PCC enhanced by MCs is empowering patients to regain control in medical interactions. Similar to previous studies (Kristensen et al., 2018), our findings show that MCs empower patients to determine the relationship that develops with the MC—to either engage or disengage with the MC. Medical clowns take an inferior position, allowing patients to feel victorious and superior, a feeling rarely experienced in the hospital setting. Furthermore, MCs empower patients by treating them as experts, encouraging them to express their needs and wishes and to become more involved and to take control in their treatment plan. This is accomplished by taking the patient’s side and building a partnership.

As part of enhancing a sense of control, caring, and encouragement, some of the skills identified here may be related to what Gray (Gray et al., 2021) termed as MCs’ power of foolishness, that is, engaging with other people bravely and vulnerably while being prepared to fail and to seem ridiculous (Gray et al., 2021; Salverson, 2006, 2008). The ability to fail, to acknowledge their position as inferior to the patient is very helpful in the challenging, strict, powerful setting, where success and failure are very clear and objectively measured. The MCs’ willingness to take on the role of failure, giving it other forms and colors, “surviving” and recovering from the failure, can be an opportunity to challenge the hospital norms. Thus, they change the patient’s perspective and mood, at least for several minutes; rethinking what is valued as successful and/or positive (Bailes, 2011; Stanley, 2013; Tannahill, 2015).

In this study, we identified that MCs take on the role of patients’ advocates, facilitating and encouraging negotiation and expression of difference of opinion, allowing patients to learn new ways to express themselves (Barkmann et al., 2013). These elements are crucial in PCC and challenge the hierarchical medical environment. In this sense, MCs try to create an alternative environment (Dionigi et al., 2014; Friedler et al., 2017; Lopes-Júnior et al., 2020; Nuttman-Shwartz et al., 2010; Weaver et al., 2007), excluding some of the traditional, patriarchal characteristics.

In addition, MCs invested much effort in taking patients’ minds off pain or distracting them from their current gloom. Distraction, which “involves deploying attention away from the emotionally salient aspects of an emotion-eliciting event,” (Thiruchselvam et al., 2011) is an important tool to refocus attention from pain, suffering, or fear (Carlson et al., 2020; Windich-Biermeier et al., 2007). Effective distraction diverts attention from the unpleasant details of the medical procedure and devises an enjoyable, engaging task. It requires creativity, that is, the use of imagination and creativity to transform the situations and the physical world possessing an open and joyful outlook, identified as a core competency for MCs (Holland et al., 2022). In this study, distraction was used effectively to make difficult treatment doable or even enjoyable. Distraction was verbal, for example, asking an embarrassing question, and nonverbal, using accessories. The ability to use various forms of distraction is important as the more actively engaging and diverse it is, the more effectively it will interfere with the perception of pain (Dahlquist et al., 2002; Duff, 2003; Windich-Biermeier et al., 2007). Some forms of distraction identified here can be applicable to other healthcare professionals to help minimize resistance and change the mood.

Distraction can be messy and noisy, and may be perceived by other medical staff as disturbing, annoying, challenging (Barkmann et al., 2013; Gomberg et al., 2020; Mortamet et al., 2017; van Venrooij & Barnhoorn, 2017). This may be due to displays of loud and slapstick humor in a limited space, where other health professionals need to concentrate on performing a task, or due to the dissonance between the patient’s acute suffering and the MC’s high spirits. However, the noise, distraction, and dissonance identified appear to be calculated and designed both to meet patient’s/family’s needs and to assist medical staff to accomplish treatment goals. In this sense, most MCs in our study seemed to manage to hold the competency of organizational finesse (Holland et al., 2022)—integrating into the teams in their settings. Organizational finesse requires MCs to perform a quick, sensitive reading of the environment, the situations, and the issues. This was seen in the triadic simulations (with the patient and the healthcare provider) where MCs moved rapidly through various skills to present the patient’s voice, while encompassing the treatment needs as well. In these cases, MCs acted as mediators, who bridge between the 2 “opposing” sides of the dyad—the patients/relatives and the medical caretakers. This was sometimes achieved even by physically standing between the patient and the healthcare provider when conflict arose and stepping aside when the relationship and treatment continued as planned. These type of skills and interventions require other health professionals’ cooperation in allowing the MCs to “interrupt” (Gomberg et al., 2020; Raviv, 2014).

The invitation to MCs to “interrupt” is not easy. Medical clowns work in an environment that may be experienced as challenging and even hostile to their actions. The healthcare setting is hierarchical when MCs try to break down this hierarchy. The medical environment contains order. The physician is the one in control, so that when MCs make a mess, they may surprise the healthcare team and give more control to the patient. Healthcare professionals may experience this “interruption” negatively if they are unaware of MCs’ therapeutic goals and skills, and may lack patience with the process they are trying to achieve. Thus, this study is important for helping healthcare professionals to create more ties and clarity vis-à-vis the MCs and to learn how to work in duo (as when two MCs work together) (Holland et al., 2022) to avoid unintended negative consequences of MCs’ intervention in the sensitive, sterile, healthcare environment.

Strengths, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

This study helped move the MC profession one step forward through systematically identifying MCs’ skills and therapeutic goals in three challenging simulations with different participants. Although important and useful, the study has several limitations, indicating the need for further research. First, all participating MCs were from one training program, Dream Doctors. As this training program sees MCs as part of the medical team, it looks upon them as partners in achieving the therapeutic goal of motivation for treatment. Other training programs may see their role differently and emphasize different goals. Second, the study was based on simulated encounters and interviews. This triangulation was helpful as the simulations were used for exploring “what occured, that is, which skills were used (e.g., physical touching), while interviews facilitated learning about MCs’ motives, explanations, and personal experience (e.g., the intent to send a message of seeing the other’s pain). It is important to do future studiesne in a genuine hospital setting, with different patients, parents, and healthcare providers, to explore the relevance of the various skills identified here. Finally, analysis was from the research team perspective. We recommend exploring patients’ and health professionals’ perspectives of MCs’ use of the identified skills. Further assessment is needed of the actual outcomes of MCs’ application of the various skills.

Conclusions and Practice Implications

The findings from this study show that MCs apply a variety of skills intended to help achieve four main therapeutic goals of connecting, dealing with emotions, empowering patients and establishing their control, and promoting treatment adherence. Identification of these goals and clarification of the fast-moving, creativity, flexibility, organizational finesse, and use of performance arts, can take the MC profession one step forward from being perceived as a strange, mysterious, and sometimes ridiculous art to a profession with specific skills and therapeutic goals intended to help patients, family members, and medical staff. The skills identified in this study can be used to in training MCs to expand the range of skills applied by MCs them for better tailoring to the specific patient, purpose, situation, and goal.

Learning the skills identified here can benefit other healthcare professionals in two main ways: First, by adopting selected skills, such as anchoring to a patient’s object, facilitating small talk and initial connection, or distraction to relieve pain. Second, better understanding of MCs’ roles and skills can improve teamwork and make health professionals more amenable to MCs’ presence in the room. If health professionals know how and when to collaborate with MCs to help patients overcome challenges, they may be more tolerant of MCs’ “disruption” of hospital order. This will provide MCs with the time and space to connect with patients, to help patients feel cared for and seen, to encourage them to become active participants in their treatment plan, and to increase their motivation and ability for adherence. This may in turn enhance PCC and improve patients’ well-being.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for More Than Just an Entertainment Show: Identification of Medical Clowns’ Communication Skills and Therapeutic Goals by Orit Karnieli-Miller, Orna Divon-Ophir, Doron Sagi, Liat Pessach-Gelblum, Amitai Ziv, and Lior Rozental in Qualitative Health Research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Danielle Freedman from the School of Medicine and Anat Zonnenstein, a medical clown, for their helpful comments in the initial analysis process.

Note

Holland et al., 2022 described MCs’ competencies as “clown play, quality of presence, creativity, organizational finesse, flexibility and relational skills” based on “Vinit, F., Roy, A., Fauconnier, M., & Sirois, M. (2014). Core competencies of the therapeutic clown practitioner. Dr. Clown.” We were unable to identify the original file.

Author Contribution Statement: First author is responsible for conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; writing - original draft & editing. Second author is responsible for the resources, formal analysis, validation, writing - review & editing. Third author is responsible for the formal analysis, validation, data curation; formal analysis; writing - review & editing. Fourth author is responsible for writing - review & editing. Fifth author is responsible for conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing - review & editing. Last author is responsible for formal analysis; validation; writing - original draft & editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by The Magi Foundation & Adelis Foundation and Dream Doctors Project through a grant for research on “Identifying best practices for communication challenges of medical clowns with patients’ parents, adolescent patients, and medical teams.”

Previous presentations: Earlier versions of this manuscript were presented at three conferences: The 3rd Scientific Conference of the Israeli Association for Medical Education (HEALER), The Sackler Faculty of Medicine Medical Research Fair and the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare (ICCH).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Orit Karnieli-Miller https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5790-0697

Lior Rozental https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4338-2814

References

- Adami M., Kiger A. (2004). The use of triangulation for completeness purposes. Nurse Researcher, 12(4), 19–29. 10.7748/nr2005.04.12.4.19.c5956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailes S. J. (2011). Performance theatre and the poetics of failure. [Google Scholar]

- Barkmann C., Siem A.-K., Wessolowski N., Schulte-Markwort M. (2013). Clowning as a supportive measure in paediatrics - A survey of clowns, parents and nursing staff. BMC Pediatrics, 13(1), 166. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battrick C., Glasper E. A., Prudhoe G., Weaver K. (2007). Clown humour: The perceptions of doctors, nurses, parents and children. Journal of Children’s and Young People’s Nursing, 1(4), 174–179. 10.12968/jcyn.2007.1.4.24403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkan J. (1999). Immersion/crystallization. In Crabtree B. R., Miller W. L. (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (2nd ed.), pp. 179–194. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Butler L. (2012). Everything seemed new”: Clown as embodied critical pedagogy. Theatre Topics, 22(1), 63–72. 10.1353/tt.2012.0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D. T., Fiske D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. In: Psychological Bulletin (56, Issue 2, pp. 81–105). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/h0046016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson K. L., Broome M., Vessey J. A. (2000). Using distraction to reduce reported pain, fear, and behavioral distress in children and adolescents: A multisite study. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses, 5(2), 75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapan S. D. C., Oliveira W., Uvinha R. R. (2020). Clown therapy: Recovering health, social identities, and citizenship. June. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlquist L. M., Busby S. M., Slifer K. J., Tucker C. L., Eischen S., Hilley L., Sulc W. (2002). Distraction for children of different ages who undergo repeated needle sticks. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 19(1), 22–34. 10.1053/jpon.2002.30009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionigi A., Canestrari C. (2016). Clowning in health care settings: The point of view of adults. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 12(3), 473–488. 10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionigi A., Flangini R., Gremigni P. (2014). Clowns in hospitals (pp. 213–227). Humor and Health Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Dionigi A., Goldberg A. (2019). Highly sensitive persons, caregiving strategies and humour: The case of Italian and Israeli medical clowns. European Journal of Humour Research, 7(4), 1–15. 10.7592/EJHR2019.7.4.dionigi [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duff A. J. A. (2003). Incorporating psychological approaches into routine paediatric venepuncture. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(10), 931–937. 10.1136/adc.88.10.931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy F. D., Gordon G. H., Whelan G., Cole-Kelly K., Frankel R., Buffone N., Lofton S., Wallace M., Goode L., Langdon L. (2004). Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II report. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 79(6), 495–507. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15165967. 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. M., Franks P., Fiscella K., Shields C. G., Meldrum S. C., Kravitz R. L., Duberstein P. R. (2005). Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Social Science and Medicine, 61(7), 1516–1528. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay F., Baverstock A., Lenton S. (2014). Therapeutic clowning in paediatric practice. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(4), 596–605. 10.1177/1359104513492746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedler S., Glasser S., Levitan G., Hadar D., Sasi B. El, Lerner-Geva L. (2017). Patients’ evaluation of intervention by a medical clown visit or by viewing a humorous film following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 22(1), 47–53. 10.1177/2156587216629041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt H., Karnieli-Miller O., Neumann M. (2011). Sharing qualitative research findings with participants: Study experiences of methodological and ethical dilemmas. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(3), 389–395. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg J., Raviv A., Fenig E., Meiri N. (2020). Saving costs for hospitals through medical clowning: A study of hospital staff perspectives on the impact of the medical clown. Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics, 14(8273), 117955652090937. 10.1177/1179556520909376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J., Donnelly H., Gibson B. E. (2021). Seriously foolish and foolishly serious: The art and practice of clowning in children’s rehabilitation. Journal of Medical Humanities, 42(3), 453–469. 10.1007/s10912-019-09570-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg C. (2018). These things sometimes happen”: Speaking up about harassment. Health Affairs, 37(6), 1005–1008. 10.1377/HLTHAFF.2017.1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanuka P., Rotchild M., Gluzman A., Uziel Y. (2011). Medical clowns: Dream doctors as an important team member in the treatment of young children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology, 9(Suppl 1), P118. 10.1186/1546-0096-9-S1-P118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higueras A., Carretero-Dios H., Muñoz J. P., Idini E., Ortiz A., Rincón F., Prieto-Merino D., Rodríguez del Águila M. M. (2006). Effects of a humor-centered activity on disruptive behavior in patients in a general hospital psychiatric ward. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Holland M., Fiorito M. E., Gravel M. L., McLeod S., Polson J., Incio Serra N., Blain-Moraes S. (2022). We are still doing some magic”: Exploring the effectiveness of online therapeutic clowning. Arts and Health, 9, 1–16. 10.1080/17533015.2022.2047745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg S. B., McGaghie W. C., Petrusa E. R., Gordon D. L., Scalese R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 10–28. 10.1080/01421590500046924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli-Miller O., Taylor A. C., Cottingham A. H., Inui T. S., Vu T. R., Frankel R. M. (2010. a). Exploring the meaning of respect in medical student education: An analysis of student narratives. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(12), 1309–1314. 10.1007/s11606-010-1471-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli-Miller O., Vu T. R., Holtman M. C., Clyman S. G., Inui T. S. (2010. b). Medical students’ professionalism narratives: A window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Academic Medicine, 85(1), 124–133. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c42896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli-Miller O., Vu T. R., Frankel R. M., Holtman M. C., Clyman S. G., Hui S. L., Inui T. S. (2011. a). Which experiences in the hidden curriculum teach students about professionalism. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 369–377. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182087d15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli-Miller O., Taylor A., Inui T., Ivy S., Frankel R. (2011. b). Understanding values in a large health care organization through work-life narratives of high-performing employees. Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal, 2(4), 1–14. 10.5041/RMMJ.10062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli-Miller O., Werner P., Neufeld-Kroszynski G., Eidelman S. (2012). Are you talking to me?! an exploration of the triadic physician-patient-companion communication within memory clinics encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 88(3), 381–390. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.-S., Klingle R. S., Sharkey W. F., Park H. S., Smith D. H., Cai D. (2000). A test of a cultural model of patients’ motivation for verbal communication in patient-doctor interactions. Communication Monographs, 67(3), 262–283. 10.1080/03637750009376510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koller D., Gryski C. (2008). The life threatened child and the life enhancing clown: Towards a model of therapeutic clowning. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : ECAM, 5(1), 17–25. 10.1093/ecam/nem033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos P., Miller K. L., Mitchell G. J., Stirling-Twist J. (2017). Presence redefined: The reciprocal nature of engagement between elder-clowns and persons with dementia. Dementia, 16(1), 46–66. 10.1177/1471301215580895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen H. N., Lundbye-Christensen S., Haslund-Thomsen H., Graven-Nielsen T., Elgaard Sørensen E. (2018). Acute procedural pain in children. Clinical Journal of Pain, 34(11), 1032–1038. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalantika V., Yuvaraj S. (2020). Being a therapeutic clown- an exploration of their lived experiences and well-being. Current Psychology, Apel 2003, 41(3), 1131–1138. 10.1007/s12144-020-00611-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W., Lesser C. S., Epstein R. M. (2010). Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Affairs, 29(7), 1310–1318. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linge L. (2008). Hospital clowns working in pairs - in synchronized communication with ailing children. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 27–38. 10.1080/17482620701794147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linge L. (2013). Joyful and serious intentions in the work of hospital clowns: A meta-analysis based on a 7-year research project conducted in three parts. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 8, 1–8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3538281&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. 10.3402/qhw.v8i0.18907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little P., White P., Kelly J., Everitt H., Mercer S. (2015). Randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention targeting predominantly non-verbal communication in general practice consultations. British Journal of General Practice, 65(635), Article e351–e356. 10.3399/bjgp15X685237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes-Júnior L. C., Bomfim E., Olson K., Neves E. T., Silveira D. S. C., Nunes M. D. R., Nascimento L. C., Pereira-Da-Silva G., Lima R. A. G. (2020). Effectiveness of hospital clowns for symptom management in paediatrics: Systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. The BMJ, 371(8273), 371. 10.1136/bmj.m4290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead N., Bower P. (2000). Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine, 51(7), 1087–1110. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meitar D., Karnieli-Miller O., Eidelman S. (2009). The impact of senior medical students’ personal difficulties on their communication patterns in breaking bad news. Academic Medicine, 84(11), 1582–1594. 10.1097/acm.0b013e3181bb2b94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S. B., Tisdell E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tvFICrgcuSIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=research+Merriam+1988&ots=Kkiw2VBDnO&sig=JkQrAzeLNcEjEtEXB9VGUwaVKV8#v=onepage&q=research-Merriam-1988&f=false [Google Scholar]

- Michael K., Dror M. G., Karnieli-Miller O. (2019). Students’ patient-centered-care attitudes: The contribution of self-efficacy, communication, and empathy. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(11), 2031–2037. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael K., Solenko L., Yakhnich L., Karnieli-Miller O. (2018). Significant life events as a journey of meaning making and change among at-risk youths. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(4), 441–460. 10.1080/13676261.2017.1385748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. L., Crabtree B. F. (1992). Primary care research: A multimethod typology and qualitative road map. In Doing qualitative research. Crabtree B. F., Miller W. L. (Eds.), (pp. 3–28). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Ripoll R. (2010). Narrative review the theraputic value of laughter in medicine. Altemative Therapy Health Med, 16(6), 56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortamet G., Roumeliotis N., Vinit F., Simonds C., Dupic L., Hubert P. (2017). Is there a role for clowns in paediatric intensive care units? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 102(7), 672–675. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttman-Shwartz O., Scheyer R., Tzioni H. (2010). Medical clowning: Even adults deserve a dream. Social Work in Health Care, 49(6), 581–598. 10.1080/00981380903520475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes S. (2009). Freedom and constraint in the empowerment as jazz metaphor. Marketing Theory, 9(4), 463–485. 10.1177/1470593109346897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ofir S., Tener D., Lev-Wiesel R., On A., Lang-Franco N. (2016). The therapy beneath the fun: Medical clowning during invasive examinations on children. Clinical Pediatrics, 55(1), 56–65. 10.1177/0009922815598143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. In Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, inc. 10.1002/nur.4770140111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5), 1189–1208. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10591279%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1089059 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/mst/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962 [Google Scholar]

- Pendzik S., Raviv A. (2011). Therapeutic clowning and drama therapy: A family resemblance. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(4), 267–275. 10.1016/j.aip.2011.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv A. (2014). The clown’s carnival in the hospital: A semiotic analysis of the medical clown’s performance. Social Semiotics, 24(5), 599–607. 10.1080/10350330.2014.943460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rennick J. E., Rashotte J. (2009). Psychological outcomes in children following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: A systematic review of the research. Journal of Child Health Care, 13(2), 128–149. 10.1177/1367493509102472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salverson J. (2006). Witnessing subjects: A fool’s help. In: A boal companion: Dialogues on theatre and cultural politics (146–157). [Google Scholar]

- Salverson J. (2008). Taking liberties: A theatre class of foolish witnesses. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 13(2), 245–255. 10.1080/13569780802054943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R., Brown-Johnson C., Haverfield M. C., Tierney A. A., Bharadwaj S., Zionts D. L., Romero I., Piccininni G., Shaw J. G., Thadaney S., Azimpour F., Verghese A., Zulman D. M., Zulman D. M. (2018). Fostering patient-provider connection during clin-ical encounters: Insights from non-medical profes-sionals. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(2), 205–2117. http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L622329379. 10.1007/s11606-019-05525-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwebke S., Gryski C. (2003). Gravity and levity—Pain and play: The child and the clown in the pediatric health care setting. In: Humor in Children’s Lives. A Guidebook for Practitioners, 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shih F. J. (1998). Triangulation in nursing research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(3), 631–641. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires A. (2008). Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review. Bone, 23(1), 1–7. 10.1038/jid.2014.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. G. (2013). Failure theatre: An artist’s steatement. Queen University. [Google Scholar]

- Stein T., Krupat E., Frankel R. M., Permanente K. (2011). Talking to patients using the four habits model. madisonstreetpress.com/shop.shtml [Google Scholar]

- Tannahill J. (2015). Theatre of the unimpressed. In Searc of vital drama. Coach House Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tener D., Lev-Wiesel R., Franco N. L., Ofir S. (2010). Laughing through this pain: Medical clowning during examination of sexually abused children: An innovative approach. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19(2), 128–140. 10.1080/10538711003622752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchselvam R., Blechert J., Sheppes G., Rydstrom A., Gross J. J. (2011). The temporal dynamics of emotion regulation: An EEG study of distraction and reappraisal. Biological Psychology, 87(1), 84–92. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschiesner R., Farneti A. (2020). Clowning training to improve working conditions and increase the well-being of employees. In McKay L., Barton G., Garvis S., Sappa V. (Eds.), Arts-based research, resilience and well-being across the lifespan (pp. 191–208). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-26053-8_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Nes F., Abma T., Jonsson H., Deeg D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. 10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Venrooij L. T., Barnhoorn P. C. (2017). Hospital clowning: A paediatrician’s view. European Journal of Pediatrics, 176(2), 191–197. 10.1007/s00431-016-2821-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren B., Spitzer P. (2011). The art of medicine: Laughing to longevity - the work of elder clowns. The Lancet, 378(9791), 562–563. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61280-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren B., Spitzer P. (2013). Smiles are everywhere: Integrating clown-play into healthcare practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver K., Prudhoe G., Battrick C., Glasper E. A. (2007). Sick children’s perceptions of clown doctor humour. Journal of Children’s and Young People’s Nursing, 01(08), 359–365. 10.12968/jcyn.2007.1.8.27777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. E., Megel M. E., Enenbach L., Carlson K. L. (2010). The voices of children: Stories about hospitalization. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 24(2), 95–102. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windich-Biermeier A., Sjoberg I., Dale J. C., Eshelman D., Guzzetta C. E. (2007). Effects of distraction on pain, fear, and distress during venous port access and venipuncture in children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 24(1), 8–19. 10.1177/1043454206296018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulman D. M., Haverfield M. C., Shaw J. G., Brown-Johnson C. G., Schwartz R., Tierney A. A., Zionts D. L., Safaeinili N., Fischer M., Thadaney Israni S., Asch S. M., Verghese A. (2020). Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA, 323(1), 70. 10.1001/jama.2019.19003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for More Than Just an Entertainment Show: Identification of Medical Clowns’ Communication Skills and Therapeutic Goals by Orit Karnieli-Miller, Orna Divon-Ophir, Doron Sagi, Liat Pessach-Gelblum, Amitai Ziv, and Lior Rozental in Qualitative Health Research.