Abstract

There are differences in the diagnoses of superficial gastric lesions between Japan and other countries. In Japan, superficial gastric lesions are classified as adenoma or cancer. Conversely, outside Japan, the same lesion is classified as low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia, or invasive neoplasia. Gastric carcinogenesis occurs mostly de novo, and the adenoma-carcinoma sequence does not appear to be the main pathway of carcinogenesis. Superficial gastric tumors can be roughly divided into the APC mutation type and the TP53 mutation type, which are mutually exclusive. APC-type tumors have low malignancy and develop into LGD, whereas TP53-type tumors have high malignancy and are considered cancerous even if small. For lesions diagnosed as category 3 or 4 in the Vienna classification, it is desirable to perform complete en bloc resection by endoscopic submucosal dissection followed by staging. If there is lymphovascular or submucosal invasion after mucosal resection, additional surgical treatment of gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is required. In such cases, function-preserving curative gastrectomy guided by sentinel lymph node biopsy may be a good alternative.

Keywords: Gastric adenoma, Low-grade dysplasia, High-grade dysplasia, Intramucosal carcinoma, Submucosal carcinoma, Endoscopic submucosal dissection

Core Tip: Gastric carcinogenesis occurs mostly de novo. Superficial gastric tumors can be roughly divided into the APC mutation type and the TP53 mutation type, which are mutually exclusive. APC-type tumors have low malignancy and develop into low-grade dysplasia, whereas TP53-type tumors have high malignancy and are considered cancerous even if they are small. For lesions diagnosed as category 3 or 4 in the Vienna classification system, endoscopic submucosal dissection and staging should be performed. If the tumor is diagnosed with lymphovascular or submucosal invasion, additional surgical treatment of gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is required.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide. However, the incidence of gastric cancer declined in many Western countries during the 20th century. Japan was one of the countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer, but the incidence is also decreasing. This fact proves that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is deeply involved in the development of gastric cancer[1]. In Japan, the water supply and sewerage systems were completed in the 1960s, and the H. pylori infection rate has decreased among the generations born subsequently[2,3]. Most patients with gastric cancer in Japan are elderly, and the incidence of gastric cancer among age groups with low H. pylori infection rates is low. Besides H. pylori, many factors are known to be involved in gastric carcinogenesis. These include salt intake, smoking, exposure to N-nitroso compounds, and Epstein-Barr virus infection[4-7]. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to gastric carcinogenesis are not well understood.

In contrast, the molecular mechanism leading to colorectal cancer has been clarified to some extent. Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide. Many colorectal cancers are thought to develop from adenomas and serrated polyps through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. The molecular mechanism of colorectal carcinogenesis has long been a subject of interest and has been well-studied, with genetic and epigenetic changes in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes identified in considerable detail.

There are various reasons for this difference in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms between gastric carcinogenesis and colorectal carcinogenesis. The most important is that gastric carcinogenesis is often of the de novo type and does not necessarily follow the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, making it difficult to examine the genetic changes from benign lesions to carcinoma in a sequential manner. Another reason is that the diagnostic criteria for gastric adenomas are vague and differ between countries in the East and West.

In this article, we describe the issues surrounding gastric adenomas, the molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis that have been identified to date, and future perspectives.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR GASTRIC ADENOMA

It has long been known that some benign superficial gastric lesions are difficult to distinguish from adenocarcinoma. They are conventionally called atypical epithelial lesions or IIa-subtype[8,9]. These cases were organized and given the diagnostic name “gastric adenoma[10]” approximately during the time the World Health Organization (WHO) histological classification of gastric cancer was established in the 1970s. In Japan, superficial gastric lesions are classified into adenoma and cancer and a treatment policy is adopted: The cancer is resected, small adenomas are followed up, and large adenomas are regarded as early gastric cancer (EGC) and treated by mucosal resection. In Japan, gastric adenomas are classified mainly according to glandular structure, with occasional reference to immunohistochemical mucin staining. Recently, foveolar-type gastric adenomas with a raspberry-like appearance in H. pylori-negative cases have become a contentious issue[11,12]. Conversely, outside Japan, dysplasia is used to describe lesions that are difficult to distinguish from benign to malignant. Dysplasia is defined as a histologically probable neoplastic lesion without evidence of invasive growth within the specimen. Intraepithelial neoplasia is a synonymous condition. Dysplasia is classified into low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) according to the degree of cellular atypia[13]. Gastric adenoma exists outside Japan but mainly refers to a protruding tumor.

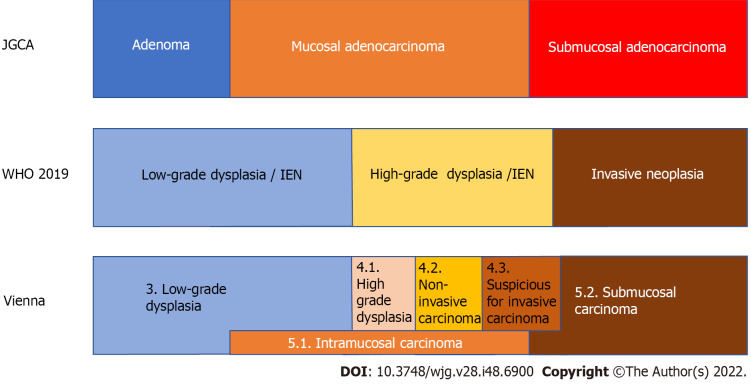

Therefore, there are differences in the diagnoses of superficial gastric lesions between Japan and other countries. Table 1 also shows the classification of gastric lesions according to the WHO classification, Vienna classification proposed at the worldwide pathologists’ consensus meeting[14], and revised Vienna classification[15]. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the diagnosis of gastric lesions and the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma[16], WHO classification, and Vienna classification. The diagnosis of adenomas in Japan is probably the most limited. It is difficult to determine the correct classification system because they all have advantages and disadvantages, and there are also differences in the frequency of encountering lesions and treatment strategies. In Japan, where the prevalence of gastric cancer is high, clinicians perform numerous endoscopic screenings. They often find EGCs, and targeted biopsy is frequently used for definitive diagnosis. Pathologists and clinicians must determine benign or malignant lesions from biopsies and determine cancer based on cellular and structural atypia. As the presence or absence of submucosal invasion is not required under the Japanese classification, cancer can be diagnosed without performing complete resection and determining the presence or absence of submucosal invasion. However, intramucosal carcinoma is also considered a cancer, although this is not accepted by some pathologists in Western countries. Conversely, according to criteria other than those of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA), it is difficult to obtain tissue from the submucosal layer with endoscopic biopsy; therefore, pathological judgment using biopsy material can only be performed in dysplasia, making it difficult to diagnose cancer using biopsy. Pathologists cannot determine gastric cancer without complete resection of the lesion, and intramucosal cancer is not defined as cancer. Although intramucosal carcinoma has a good prognosis and rarely metastasizes, lymph node metastasis still occurs in 2% of cases[17]; if left untreated, it can progress to submucosal and advanced cancer[18]. Therefore, intramucosal cancer should still be considered life-threatening. In Japan, adenomas are regarded as “benign lesions”; therefore, even among Japanese pathologists, it is difficult to distinguish high-grade intestinal-type adenomas and foveolar-type adenomas from cancer, and discrepancies in diagnosis sometimes occur.

Table 1.

The classifications of gastric adenoma of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association and gastric superficial lesions of the WHO classification and the Vienna classification

|

Classification

|

Code

|

Diagnosis

|

Subtype

|

Subtype 2

|

| JGCA[16] | Gastric adenoma | Intestinal type | ||

| Gastric type | Pyloric gland type | |||

| Foveolar type | ||||

| WHO 2019[13] | 8148/0 | Glandular intraepithelial neoplasia, low grade | ||

| 8148/2 | Glandular intraepithelial neoplasia, high grade | |||

| 8213/0 | Serrated dysplasia, low grade | |||

| 8213/2 | Serrated dysplasia, high grade | Intestinal-type dysplasia | ||

| Foveolar-type (gastric type) dysplasia | ||||

| Gastric pit/crypt dysplasia | ||||

| 8144/0 | Intestinal-type adenoma, low grade | |||

| 8114/2 | Intestinal-type adenoma, low grade | Sporadic intestinal-type gastric adenoma | ||

| Syndromic intestinal-type gastric adenoma | ||||

| 8210/0 | Adenomatous polyp, low-grade dysplasia | |||

| 8210/2 | Adenomatous polyp, high-grade dysplasia | |||

| Vienna[14] | 3 | Non-invasive low-grade neoplasia | Low-grade adenoma/dysplasia | |

| 4 | Non-invasive high-grade neoplasia | |||

| 4.1 | High-grade adenoma/dysplasia | |||

| 4.2 | Non-invasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ) | |||

| 4.3 | Suspicion of invasive carcinoma | |||

| 5 | Invasive neoplasia | |||

| 5.1 | Intramucosal carcinoma | |||

| 5.2 | Submucosal carcinoma or beyond | |||

| Revised Vienna[15] | 3 | Mucosal low-grade neoplasia | Low-grade adenoma/dysplasia | |

| 4 | Mucosal high-grade neoplasia | |||

| 4.1 | High-grade adenoma/dysplasia | |||

| 4.2 | Non-invasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ) | |||

| 4.3 | Suspicious for invasive carcinoma | |||

| 4.4 | Intramucosal carcinoma | |||

| 5 | Submucosal invasion by carcinoma |

JGCA: Japanese Gastric Cancer Association.

Figure 1.

The relationship of the diagnosis of superficial gastric lesions between the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, the WHO classification, and the Vienna classification. In Japan, gastric cancer is diagnosed based on cellular and structural atypia. On the other hand, outside Japan, dysplasia is used to describe lesions that are histologically probable neoplastic lesions without evidence of invasive growth. Intraepithelial neoplasia is a synonymous condition. Therefore, all mucosal and some submucosal cancers diagnosed by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association criteria are diagnosed as dysplasia outside Japan. The original Vienna classification is the answer to this discrepancy by setting non-invasive carcinoma and intramucosal carcinoma. IEN: Intraepithelial neoplasia; JGCA: Japanese Gastric Cancer Association.

DOES GASTRIC ADENOMA BECOME CANCER?

Many colorectal cancers are thought to develop from adenomas and serrated polyps. Do gastric adenomas become cancers, similar to colorectal cancer?

Some gastric lesions might be cancerous after mucosal resection, even if the preoperative diagnosis is adenoma using targeted biopsy. The frequency of such cases varies in the literature; however, there are reports of a reasonably high rate; therefore, caution should be exercised[19]. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between high-grade intestinal-type adenomas and very well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinomas, and sampling errors may occur in targeted biopsies[19]. In contrast, adenocarcinoma in adenoma, unlike colorectal cancer, is rarely observed in low-grade intestinal-type adenoma, and it is rare for low-grade adenoma of Vienna classification category 3 to become malignant[20]. In addition, gastric minute carcinomas without adenomatous components are common. Gastric carcinogenesis is mostly de novo, and the adenoma-carcinoma sequence does not appear to be the main pathway of carcinogenesis.

The Cancer Genome Atlas system classifies gastric cancer into four categories based on molecular biological characteristics[21]. A summary of this classification system is presented in Table 2. The molecular biological features revealed here help in the consideration of treatment strategies for advanced gastric cancer; however, this system does not provide insight into genetic alterations in the early stages of carcinogenesis.

Table 2.

Brief summary of The Cancer Genome Atlas classification

|

Type

|

Chromosomal instability

|

EBV

|

Microsatellite instability

|

Genomically stable

|

| Percentage | 50% | 9% | 21% | 20% |

| Profile of patients | Male prevalence | Elderly age | Younger age | |

| Location | GEJ, cardia | Corpus or fundus | Antrum | Distal location |

| Lauren type | Intestinal | Intestinal | Poorly cohesive | |

| Other pathological feature | DNA aneuploidy | Carcinoma with lymphoid stroma | ||

| Prognosis | Favorable | Worst | ||

| Genetic features | TP53 mutation | Extensive DNA promoter methylation | MLH1 promoter hypermethylation | Low copy number alterations and mutational burden |

| Amplification of TKR | CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation | High mutational burden | ARID1, RHOA, CDH1 mutations | |

| PIK3CA, ARID1A, BCOR mutations | CLDN18-ARHGAP26 fusion in 15% |

TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; EBV: Eptein-Barr virus; GEJ: Esophagogastric junction.

The pathway for the accumulation of gene mutations leading to gastric carcinogenesis is not as clear as that in colorectal cancer. This may be mainly due to the lack of a clear adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the stomach and the discrepancy in the diagnostic criteria for gastric adenoma and intramucosal carcinoma between countries in the East and West.

GENETIC MUTATION AND CANCERIZATION OF GASTRIC ADENOMA AND DYSPLASIA

Recent advances in genetic analysis have provided insights into gene mutations in adenomas and dysplasia, and the pathway to carcinogenesis in adenomas and dysplasia is becoming more clear.

Fassan et al[22] investigated the mutational status of HGD and EGC using high-throughput mutation profiling. Mutations in APC, ATM, FGFR3, PIK3CA, RB1, STK11, and TP53 were confirmed in both HGD and EGC. Lim et al[23] examined the mutation profiles of LGD using whole-exome sequencing and confirmed that APC mutations occur in LGD. Lee et al[24] examined APC mutations in adenomas, dysplasias, and adenocarcinomas. They found that APC mutations play an essential role in the pathogenesis of adenoma and dysplasia but have a limited role in the progression to adenocarcinoma. Rokutan et al[25] investigated the mutational status of LGD, HGD, and intramucosal carcinoma using targeted deep DNA sequencing. They found that APC mutations and TP53 mutations were highly prevalent in these lesions and were the initial mutations in the tumors. TP53 mutations were also found in microscopic intramucosal carcinomas of 1 mm and 3 mm. APC mutations were found in all the LGDs examined. In contrast, no TP53 mutations were detected in the LGD group. APC mutations and TP53 mutations are frequently observed in patients with HGD, but they are mutually exclusive.

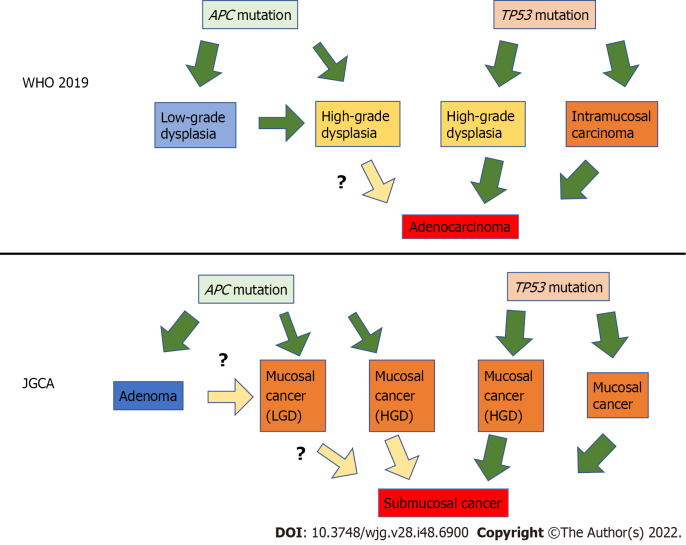

Based on these results, superficial gastric tumors can be roughly divided into the APC mutation type and the TP53 mutation type. APC-type tumors have low malignancy and develop into LGD, whereas TP53-type tumors have high malignancy and are judged as cancerous even if they are small[25]. It is still unclear whether APC-type LGD progresses into HGD or whether APC-type HGD progresses into cancer. In contrast, it is reasonable to treat TP53-type HGD as cancer. This finding is illustrated in Figure 2; it also shows the translation of this to the JGCA criteria. Many Japanese gastric cancer specialists believe that all mucosal cancers progress from submucosal to advanced. However, some mucosal cancers may not progress to submucosal cancer, although they may progress laterally.

Figure 2.

The diagram assuming the relationship between gene mutations and gastric carcinogenesis. Superficial gastric tumors can be roughly divided into two types by specific gene mutations: The APC mutation type and the TP53 mutation type. APC-type tumors have low malignancy and develop into low-grade dysplasia, whereas TP53-type tumors have high malignancy and are considered cancerous even if small. JGCA: Japanese Gastric Cancer Association; HGD: High-grade dysplasia; LGD: Low-grade dysplasia.

HOW SHOULD GASTRIC TUMORS BE TREATED?

Superficial gastric tumors are often observed in H. pylori-positive stomachs under numerous gastroscopies. There is still no consensus regarding the treatment of these tumors.

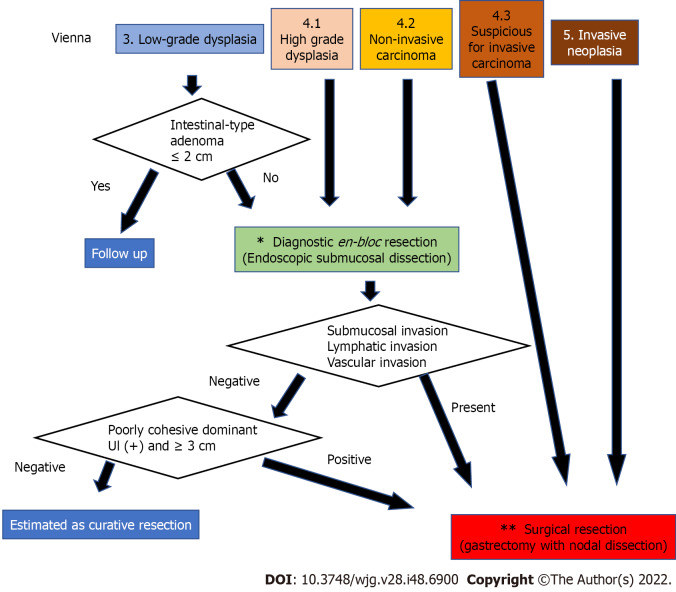

In Japan, EGC is often detected, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is frequently performed; therefore, most superficial gastric tumors, including gastric adenomas, are resected by ESD[19]. The treatment policy is the same in China and South Korea, where there are many H. pylori-positive individuals. In contrast, in Western countries, the treatment of dysplasia is not always standardized due to the small number of H. pylori-positive patients, low number of gastroscopies performed, and lack of widespread use of ESD. In the Vienna classification[14,15], a target biopsy diagnosis is set from category 1 to 5, with category 1 being negative for neoplasia and should undergo no treatment, category 2 is indefinite for neoplasia and should undergo repeat biopsy, and category 5 is indicated for surgical resection. The problem is the treatment of categories 3 and 4. The revised Vienna classification[15] recommends endoscopic resection or follow-up for category 3 and endoscopic or surgical local resection for category 4. The 2012 MAPS guideline[26] states that “patients with endoscopically visible HGD or carcinoma should undergo staging and adequate management”. According to this, category 3 should be followed up, and category 4 should undergo excision. In contrast, the 2019 MAPS II guideline[27] states that “patients with an endoscopically visible lesion harboring LGD, HGD, or carcinoma should undergo staging and treatment”. Due to the uncertainty of biopsy diagnosis[28,29], it is assumed that LGD would be upgraded to HGD or adenocarcinoma after resection. Therefore, treatment is also required for LGD[27], and category 3 is targeted for diagnostic treatment. However, staging and treatment methods have not been described. Considering the invasiveness of surgical resection, it is desirable to perform complete en bloc resection by ESD first[30] and then perform staging. Subsequent treatment should follow the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines[31]. If the tumor is a well to moderately differentiated mucosal cancer with no lymphovascular invasion, treatment is completed, and if lym-phovascular invasion or submucosal invasion is found, additional surgical treatment of gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is required.

Conversely, do we need ESD for all category 3 cases? Endoscopic resection of colorectal adenomas reduces the incidence of colorectal cancer, which provides evidence that the adenoma-carcinoma sequence is an essential pathway for colorectal carcinogenesis. In contrast, low-grade intestinal adenomas, which are rarely associated with adenocarcinomas, are unlikely to become cancerous even if left untreated. Upgrading to HGD or adenocarcinoma has been reported to be less than 10% after follow-up for adenoma and LGD[20,32], and the possibility of regression with H. pylori eradication therapy has also been reported[32]. For these reasons, category 3 adenomas can be safely treated with observation; if the adenoma meets the intestinal type in the JGCA criteria and is less than 2 cm in size, resection may not be necessary. However, a case of gastric-type adenoma that was adenocarcinoma in adenoma with submucosal invasion has been reported[33], and follow-up of gastric-type adenoma may not always be safe. In addition, the safety of observing LGDs that fall into mucosal cancer in the JGCA criteria is not guaranteed. In the future, further understanding of the relationship between genetic mutations in LGD and the natural history of lesions will provide profiles for safe follow-up of category 3 Lesions. Category 3 patients with APC mutations may be observed. However, at this time, category 3 adenomas, other than intestinal-type adenomas, seem to have no choice but to undergo complete diagnostic resection with ESD.

The results are summarized in Figure 3. Since category 3 and 4 Lesions are highly likely to be mucosal adenocarcinomas according to the JGCA criteria, complete en bloc resection of the mucosal layer is desirable even for diagnostic purposes, and ESD is appropriate. However, ESD is a complicated procedure. Surgical mucosal resection and laparoscopic intragastric surgery may also be acceptable in cases where there is no skilled endoscopist[34]. In contrast, category 5 corresponds to submucosal adenocarcinoma in the JGCA criteria; therefore, gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is necessary[17,30]. Category 4.3. also has a high possibility of developing similar lesions; thus, surgery should be performed from the beginning. In addition, since the possibility of lymph node metastasis is only 15%-20% even for such lesions, not only gastrectomy with nodal dissection up to D1+ but also function-preserving curative gastrectomy guided by sentinel lymph node biopsy may be a good indication[17].

Figure 3.

The strategy for diagnosis, staging, and treatment of gastric dysplasia and cancer according to the Vienna classification. Since category 3 and 4 Lesions are highly likely to be mucosal adenocarcinomas according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) criteria, complete en bloc resection of the mucosal layer is desirable for diagnosis and initial treatment. However, a small part of category 3, such as a small intestinal-type adenoma judged by the JCGA criteria, can be followed up. In contrast, category 5 corresponds to submucosal adenocarcinoma according to the JGCA criteria; therefore, curative surgery is necessary. Category 4.3 was also treated surgically. The asterisk (*): For en bloc mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection is appropriate; however, laparoscopic intragastric surgery may also be acceptable in cases where there is no skilled endoscopist. The two asterisks (**): Gastrectomy with lymph node dissection up to D1+ is recommended for surgical treatment. However, since the possibility of lymph node metastasis is only 15%-20% even for such lesions, function-preserving curative gastrectomy guided by sentinel lymph node biopsy can be performed by a specialist.

CONCLUSION

Gastric carcinogenesis occurs mostly de novo, and the adenoma-carcinoma sequence does not appear to be the main pathway of carcinogenesis. Superficial gastric tumors can be roughly divided into the APC mutation type and the TP53 mutation type, which are mutually exclusive. For lesions diagnosed as category 3 or 4 in the Vienna classification, it is desirable to perform ESD for accurate diagnosis and staging. If there is lymphovascular or submucosal invasion, additional surgical treatment of gas-trectomy with lymph node dissection is required.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest related to the publication of this study.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: September 15, 2022

First decision: October 30, 2022

Article in press: December 5, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Noh CK, South Korea; Vieth M, Germany S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

Contributor Information

Shinichi Kinami, Department of Surgical Oncology, Kanazawa Medical University, kahoku-gun 920-0293, Ishikawa, Japan. kinami@kanazawa-med.ac.jp.

Sohsuke Yamada, Department of Clinical Pathology, Kanazawa Medical University, Uchinada 920-0293, Ishikawa, Japan.

Hiroyuki Takamura, Department of Surgical Oncology, Kanazawa Medical University, Kahoku-gun 920-0293, Ishikawa, Japan.

References

- 1.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueda J, Gosho M, Inui Y, Matsuda T, Sakakibara M, Mabe K, Nakajima S, Shimoyama T, Yasuda M, Kawai T, Murakami K, Kamada T, Mizuno M, Kikuchi S, Lin Y, Kato M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth year and geographic area in Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:105–110. doi: 10.1111/hel.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamada T, Haruma K, Ito M, Inoue K, Manabe N, Matsumoto H, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Akiyama T, Tanaka S, Shiotani A, Graham DY. Time Trends in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis Over 40 Years in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:192–198. doi: 10.1111/hel.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maddineni G, Xie JJ, Brahmbhatt B, Mutha P. Diet and carcinogenesis of gastric cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38:588–591. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P. Gastric carcinogenesis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:729–742. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0810-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirvish SS. Role of N-nitroso compounds (NOC) and N-nitrosation in etiology of gastric, esophageal, nasopharyngeal and bladder cancer and contribution to cancer of known exposures to NOC. Cancer Lett. 1995;93:17–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03786-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J, Liu Z, Zeng B, Hu G, Gan R. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer: A distinct subtype. Cancer Lett. 2020;495:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K, Fuchigami A. Histopathological study on early carcinoma of the stomach: criteria for diagnosis of atypical epithelium. Gan. 1966;57:613–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugano H, Nakamura K, Takagi K. An atypical epithelium of the stomach. Gann Monogr . 1971;11:257–269. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura K, Takagi K. Some considerations on lesion of atypical epithelium of the stomach. Stomach and Intestine (Jpn) . 1975;10:1455–1463. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibagaki K, Mishiro T, Fukuyama C, Takahashi Y, Itawaki A, Nonomura S, Yamashita N, Kotani S, Mikami H, Izumi D, Kawashima K, Ishimura N, Nagase M, Araki A, Ishikawa N, Maruyama R, Kushima R, Ishihara S. Sporadic foveolar-type gastric adenoma with a raspberry-like appearance in Helicobacter pylori-naïve patients. Virchows Arch. 2021;479:687–695. doi: 10.1007/s00428-021-03124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertz S, Angeloni M, Drgac J, Falkeis C, Lang-Schwarz C, Sterlacci W, Veits L, Hartmann A, Vieth M. Helicobacter Infection and Gastric Adenoma. Microorganisms. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K, Hattori T, Hirota T, Itabashi M, Iwafuchi M, Iwashita A, Kim YI, Kirchner T, Klimpfinger M, Koike M, Lauwers GY, Lewin KJ, Oberhuber G, Offner F, Price AB, Rubio CA, Shimizu M, Shimoda T, Sipponen P, Solcia E, Stolte M, Watanabe H, Yamabe H. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251–255. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51:130–131. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 15th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Shuppan, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinami S, Nakamura N, Tomita Y, Miyata T, Fujita H, Ueda N, Kosaka T. Precision surgical approach with lymph-node dissection in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1640–1652. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i14.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsukuma H, Oshima A, Narahara H, Morii T. Natural history of early gastric cancer: a non-concurrent, long term, follow up study. Gut. 2000;47:618–621. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato M. Diagnosis and therapies for gastric non-invasive neoplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12513–12518. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada H, Ikegami M, Shimoda T, Takagi N, Maruyama M. Long-term follow-up study of gastric adenoma/dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2004;36:390–396. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fassan M, Simbolo M, Bria E, Mafficini A, Pilotto S, Capelli P, Bencivenga M, Pecori S, Luchini C, Neves D, Turri G, Vicentini C, Montagna L, Tomezzoli A, Tortora G, Chilosi M, De Manzoni G, Scarpa A. High-throughput mutation profiling identifies novel molecular dysregulation in high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and early gastric cancers. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:442–449. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim CH, Cho YK, Kim SW, Choi MG, Rhee JK, Chung YJ, Lee SH, Kim TM. The chronological sequence of somatic mutations in early gastric carcinogenesis inferred from multiregion sequencing of gastric adenomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7:39758–39767. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Abraham SC, Kim HS, Nam JH, Choi C, Lee MC, Park CS, Juhng SW, Rashid A, Hamilton SR, Wu TT. Inverse relationship between APC gene mutation in gastric adenomas and development of adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:611–618. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rokutan H, Abe H, Nakamura H, Ushiku T, Arakawa E, Hosoda F, Yachida S, Tsuji Y, Fujishiro M, Koike K, Totoki Y, Fukayama M, Shibata T. Initial and crucial genetic events in intestinal-type gastric intramucosal neoplasia. J Pathol. 2019;247:494–504. doi: 10.1002/path.5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O'Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A, Dumonceau JM, Machado JC, Macedo G, Malfertheiner P, Matysiak-Budnik T, Megraud F, Miki K, O'Morain C, Peek RM, Ponchon T, Ristimaki A, Rembacken B, Carneiro F, Kuipers EJ European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; European Helicobacter Study Group; European Society of Pathology; Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) Endoscopy. 2012;44:74–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365–388. doi: 10.1055/a-0859-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim H, Jung HY, Park YS, Na HK, Ahn JY, Choi JY, Lee JH, Kim MY, Choi KS, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim JH. Discrepancy between endoscopic forceps biopsy and endoscopic resection in gastric epithelial neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1256–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao G, Xue M, Hu Y, Lai S, Chen S, Wang L. How Commonly Is the Diagnosis of Gastric Low Grade Dysplasia Upgraded following Endoscopic Resection? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ono H. Early gastric cancer: diagnosis, pathology, treatment techniques and treatment outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:863–866. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200608000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition) Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Suzuki H, Kono S, Iwatsuka K, Kusano C, Oda I, Sekine S, Moriyasu F. Morphologic and Histologic Changes in Gastric Adenomas After Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Long-Term Prospective Analysis. Helicobacter. 2015;20:431–437. doi: 10.1111/hel.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirata I, Kinugasa H, Miyahara K, Higashi R, Kunihiro M, Morito T, Ichimura K, Tanaka T, Nakagawa M. [Gastric type adenoma with submucosal invasive carcinoma:a case study] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2018;115:283–289. doi: 10.11405/nisshoshi.115.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohashi S. Laparoscopic intraluminal (intragastric) surgery for early gastric cancer. A new concept in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:169–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00191960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]