Abstract

We retrospectively evaluated complications and functional and oncologic outcomes of 94 consecutive men who underwent primary whole-gland cryoablation for localized prostate cancer (PCa) from 2002 to 2012. Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed using a landmark starting at 6 mo of follow-up. In total, 75% patients had D’Amico intermediate- (48%) or high- (27%) risk PCa. Median follow-up was 5.6 yr. Median time to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) nadir was 3.3 mo, and 70 patients reached PSA <0.2 ng/ml postcryoablation. The 90-d high-grade (Clavien Grade IIIa) complication rate was 3%, with no rectal fistulas reported. Continence and potency rates were 96% and 11%, respectively. The 5-yr biochemical failure-free survival (PSA nadir + 2 ng/ml) was 81% overall and 89% for low-, 78% for intermediate-, and 80% for high-risk PCa (p = 0.46). The median follow-up was 5.6 and 5.1 yr for patients without biochemical failure and with biochemical failure, respectively. The 5-yr clinical recurrence-free survival was 83% overall and 94% for low-, 84% for intermediate-, and 69% for high-risk PCa (p = 0.046). Failure to reach PSA nadir <0.2 ng/ml within 6 mo postcryoablation was an independent predictor for biochemical failure (p = 0.006) and clinical recurrence (p = 0.03). The 5-yr metastases-free survival was 95%. Main limitation is retrospective evaluation. Primary whole-gland cryoablation for PCa provides acceptable medium-term oncologic outcomes and could be an alternative for radiation therapy or radical prostatectomy.

Keywords: Biochemical failure, Clinical recurrence, Cryoablation, Prostate cancer

Patient summary:

Cryoablation is a safe, minimally-invasive procedure that uses cold temperatures delivered via probes through the skin to kill prostate cancer (PCa) cells. Whole-gland cryoablation may offer an alternative treatment option to surgery and radiotherapy. We found that patients had good cancer outcomes 5 yr after whole-gland cryoablation, and those with a prostate-specific antigen value ≥0.2 ng/ml within 6 mo after treatment were more likely to have PCa recurrence.

Cryoablation is recommended as an alternative treatment for recurrent localized prostate cancer (PCa) [1]. Although biochemical failure (BF) outcomes postcryoablation have been reported, there is a lack of predictors for clinical recurrence (CR) [2,3]. Herein, we evaluated perioperative, 90-d complications, functional and oncologic outcomes, and identified predictors for BF and CR following whole-gland prostate cryoablation.

At our institution, cryoablation is offered as an alternative to standard treatment modalities. We reviewed the records of 94 consecutive men who underwent primary whole-gland cryoablation for clinically localized PCa from 2002 to 2012. Patients underwent transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)-Doppler evaluation, followed by image targeting of suspicious hypoechoic lesions and systematic sextant prostate biopsy (Type EUB-6500; Hitachi Medical Systems America Inc.) [4–6]. Our study period started in 2002 when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not available for image-fusion biopsy or staging. Nevertheless, detailed mapping of cancer location was recorded in three-dimensional schematic drawings, and TRUS images were electronically stored for surgical planning and follow-up [4–6].

Patients were grouped based on D’Amico PCa risk classification [7]. High-risk PCa patients underwent whole-body bone scan and computed tomography of abdomen and pelvis to rule out metastases. Neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was administered for 6 mo prior to cryoablation in 38 (40%) patients with large prostates to down-size large-volume prostates, which may pose a challenge for proper whole-gland cryoablation. No patients received adjuvant ADT. Although prostate size was not a selection criterion, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) and maximum prostate size at the time of cryoablation were 37 (27–47) ml and 60 ml, respectively.

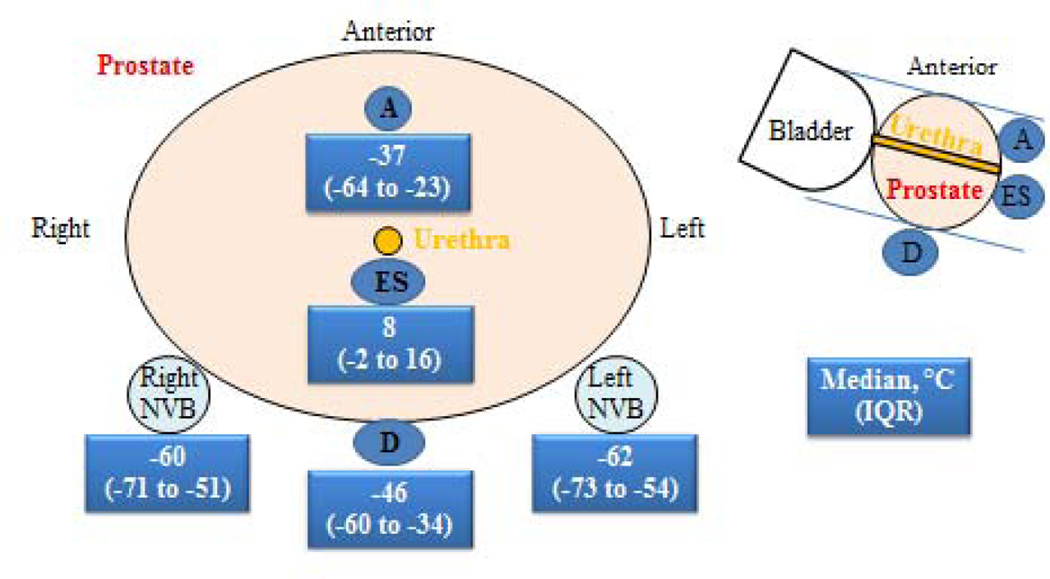

Whole-gland cryoablation was performed by a free-hand technique under TRUS guidance using an argon/helium gas-based system (Endocare, HealthTonics Inc., Austin, TX, USA), with a double freeze-thaw cycle (Fig. 1) [5,6]. All patients maintained an 18F Foley catheter for 1 wk after cryoablation that was discontinued after a voiding trial. Follow-up with digital rectal examination (DRE), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and TRUS imaging with Doppler was scheduled at 3, 6, and 12 mo after treatment and annually thereafter. Follow-up biopsy was offered to all patients at 12 and 24 mo or anytime if clinically indicated, including rising PSA, BF, or suspicious DRE or TRUS.

Fig. 1 –

Thermocouple temperatures during whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate.

A = apex; D = Denonvilliers’ fascia, ES: external rhabdoshphincter, IQR = inter quartile range, NVB = neurovascular bundles.

BF was defined as a PSA rise of ≥2 ng/ml above the nadir (Phoenix criteria). Other BF criteria were explored: PSA nadir + 1.2 ng/ml (Stuttgart criteria) and PSA ≥0.2 ng/ml (post-radical prostatectomy criteria) [2,8,9]. CR was defined as cancer on follow-up biopsy, evidence of recurrence by physical exam or imaging, salvage treatment, or initiation of ADT [8–10].

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival curves. Log-rank test was used to compare risk groups. Multivariable cox regression included clinically important parameters and statistical significance on univariate analysis. Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed using a landmark starting at 6 mo of follow-up postcryoablation. Statistical significance was considered if p value was <0.05.

Table 1 shows patients’ baseline characteristics. Furthermore, 90-d Clavien Grade I or II complications were 14% and 10%, respectively (Table 2). Three (3%) patients experienced urinary retention (Clavien Grade IIIa) requiring transurethral resection of the prostate. There were no rectal fistulas.

Table 1 –

Demographics pre whole-gland cryoablation of the prostatea

| Parameter | Median (IQR) or n (%) | Median (IQR) or n (%) | Median (IQR) or n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up time | All patients | ≥6 mo | <6 mo | – |

|

| ||||

| n | 94 | 87 | 7 | – |

|

| ||||

| Age, yr | 71 (66–75) | 71 (66–75) | 68 (60–78) | 0.53 |

|

| ||||

| Prostate volume, ml | 37 (27–47) | 37 (27–50) | 38 (24–40) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| PSA, ng/ml | 7.5 (5–11) | 7.5 (5–11) | 11 (4.6–24) | 0.33 |

|

| ||||

| Clinical stage | ||||

| T1c | 47 (50) | 44 (51) | 3 (43) | |

| T2a | 35 (37) | 31 (36) | 4 (57) | |

| T2b | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| T2c | 4 (4) | 4(5) | 0 (0) | 0.79 |

| T3a | 6 (6) | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| T3b | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||||

| Gleason score | ||||

| 3+3 | 29 (31) | 27 (31) | 2 (29) | |

| 3+4 | 24 (26) | 23 (26) | 1 (14) | |

| 4+3 | 25 (27) | 22 (25) | 3 (43) | 0.26 |

| 4+4 | 13 (14) | 12 (14) | 1 (14) | |

| 4+5 | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||||

| Biopsy cores, n | 7 (6–8) | 7 (6–8) | 7 (7–8) | 0.35 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer cores in biopsy, n | 2 (2–4) | 2 (2–4) | 3 (2–3) | 0.59 |

|

| ||||

| Maximum cancer core length, mm | 6 (3–9) | 6 (3–8.7) | 3.5 (2–9) | 0.38 |

|

| ||||

| Maximum cancer core, % | 48 (20–65) | 48 (20–68) | 45 (25–60) | 0.92 |

|

| ||||

| D’Amico risk group | ||||

| Low | 24 (25) | 22 (25) | 2 (29) | |

| Intermediate | 45 (48) | 43 (49) | 2 (29) | 0.46 |

| High | 25 (27) | 22 (25) | 3 (43) | |

|

| ||||

| Patients that received neoadjuvant | ||||

| ADT | ||||

| Low | 10 (11) | 9 (10) | 1 (14) | |

| Intermediate | 14 (15) | 14 (16) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| High | 14 (15) | 12 (14) | 2 (29) | |

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate specific antigen.

Some cumulative percentages may not be 100% because of rounding.

Table 2 –

Summary of 90-d complications post whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate

| Complication | Management | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Clavien grade | n | 13 (14%) | |

| I | 1 | Tissue sloughing | Expectant management |

| 1 | Urgency of urination | Symptomatic | |

| 2 | Urinary retention | Prolonged Foley catheterization | |

|

| |||

| II | 1 | Excruciating pain in the penis and scrotum | Analgesics |

| 1 | UTI | Antibiotics | |

| 1 | Recurrent UTI/ chronic prostatitis | Antibiotics | |

| 1 | Urinary retention + UTI | Antibiotics + CIC | |

| 2 | Urinary retention + UTI | Prolonged Foley catheterization + antibiotics | |

|

| |||

| IIIa | 1 | Urinary retention | TURP |

| 2 | Urinary retention + UTI | TURP + antibiotics | |

CIC = clean intermittent catheterization; TURP = transurethral resection of the prostate; UTI = urinary tract infection.

There were no rectal fistulas.

One patient developed late complication at 6 mo postcryoablation presenting with urinary retention due to bladder neck contracture and bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral ureteral strictures that required TURP, ureteral catheterization, and dilation.

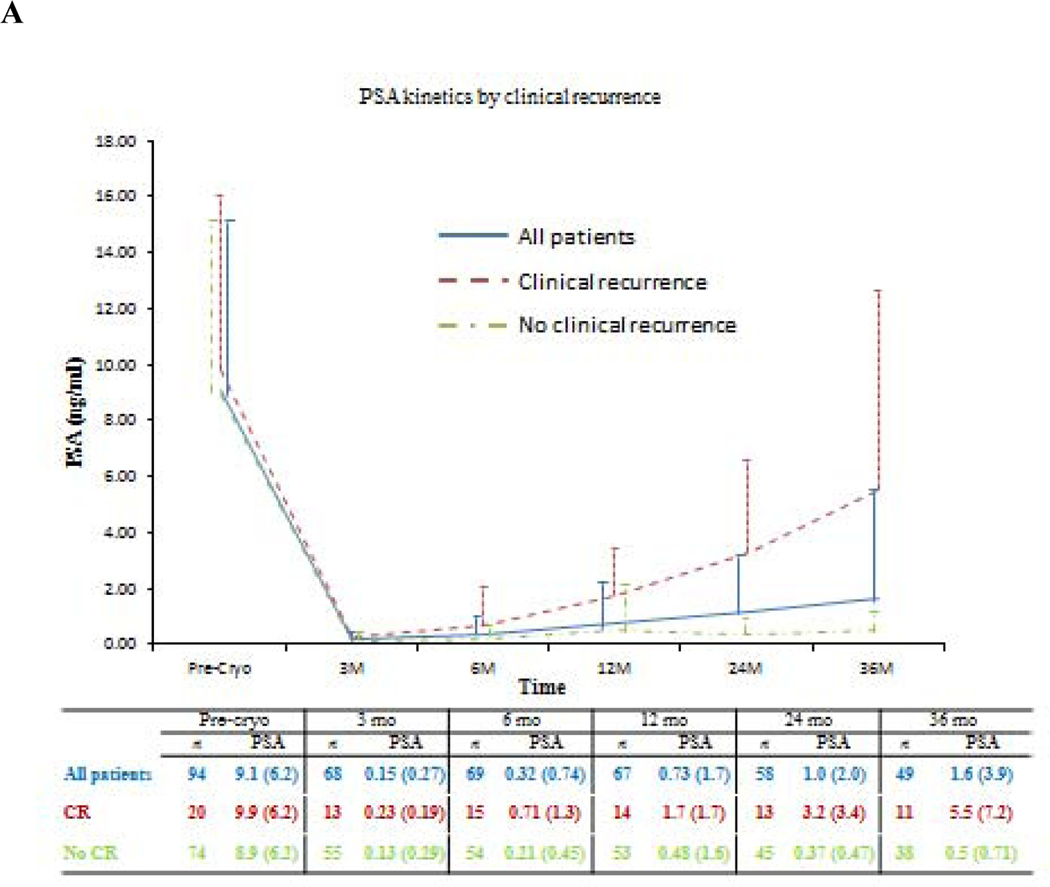

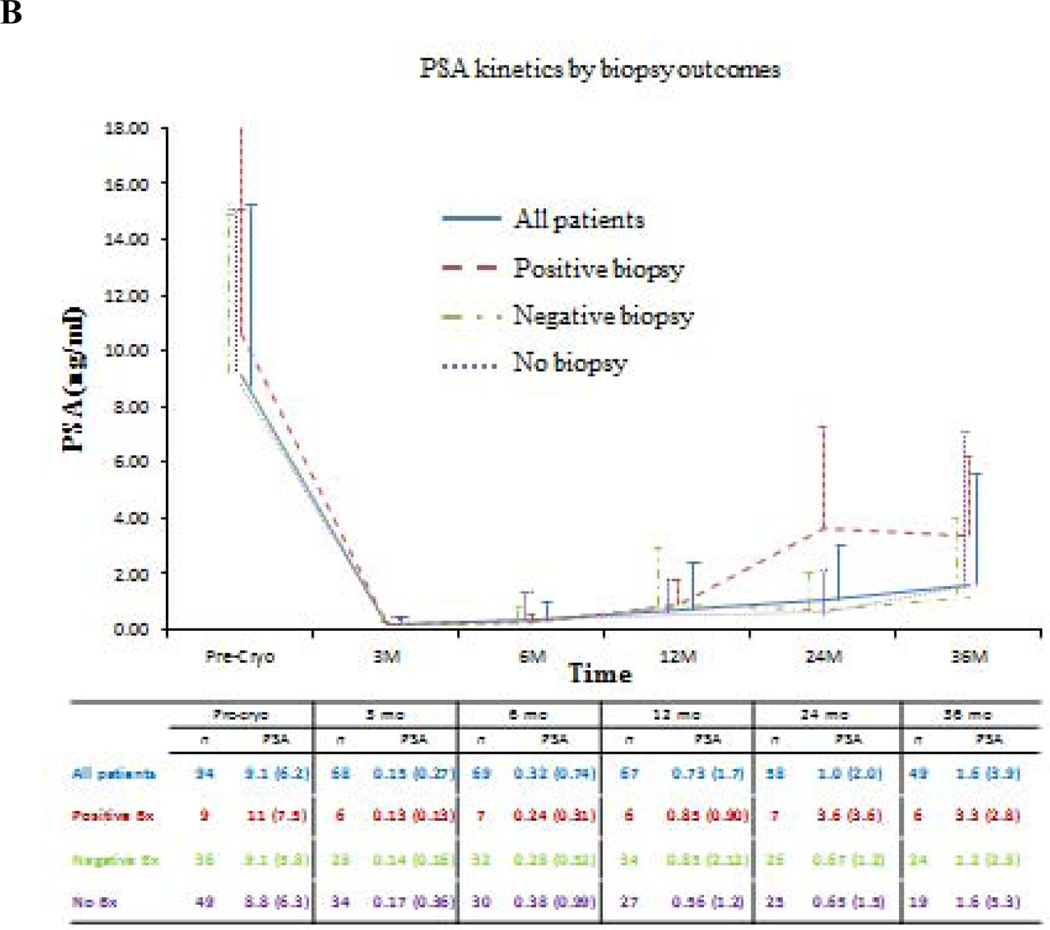

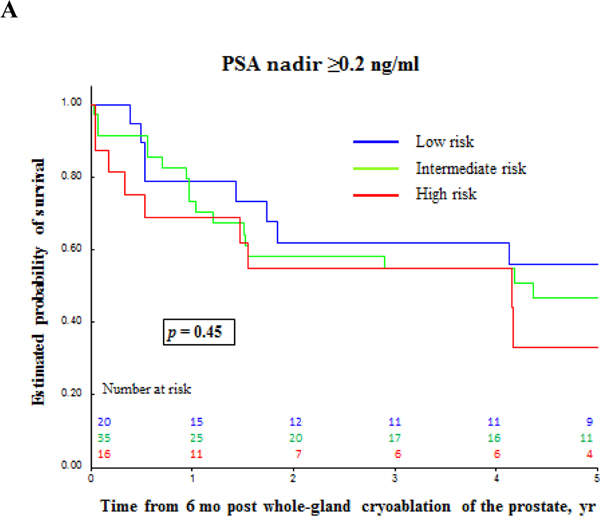

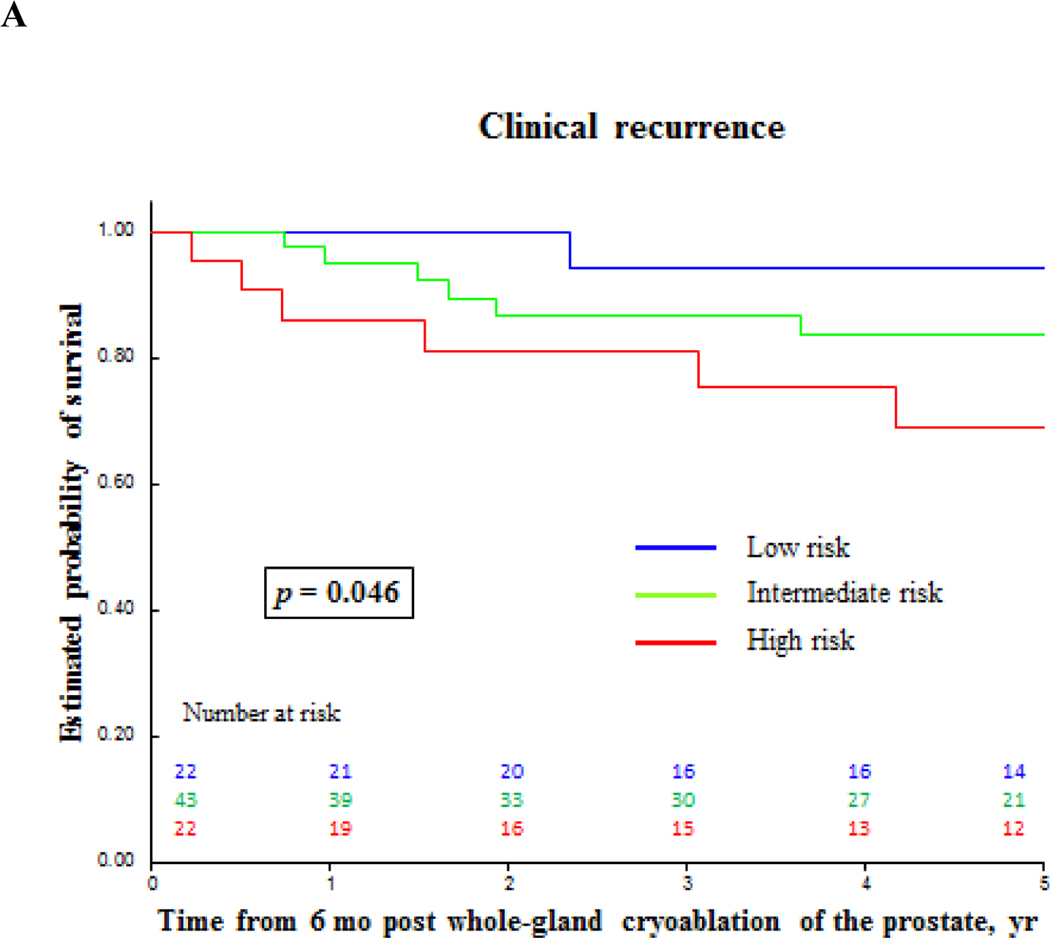

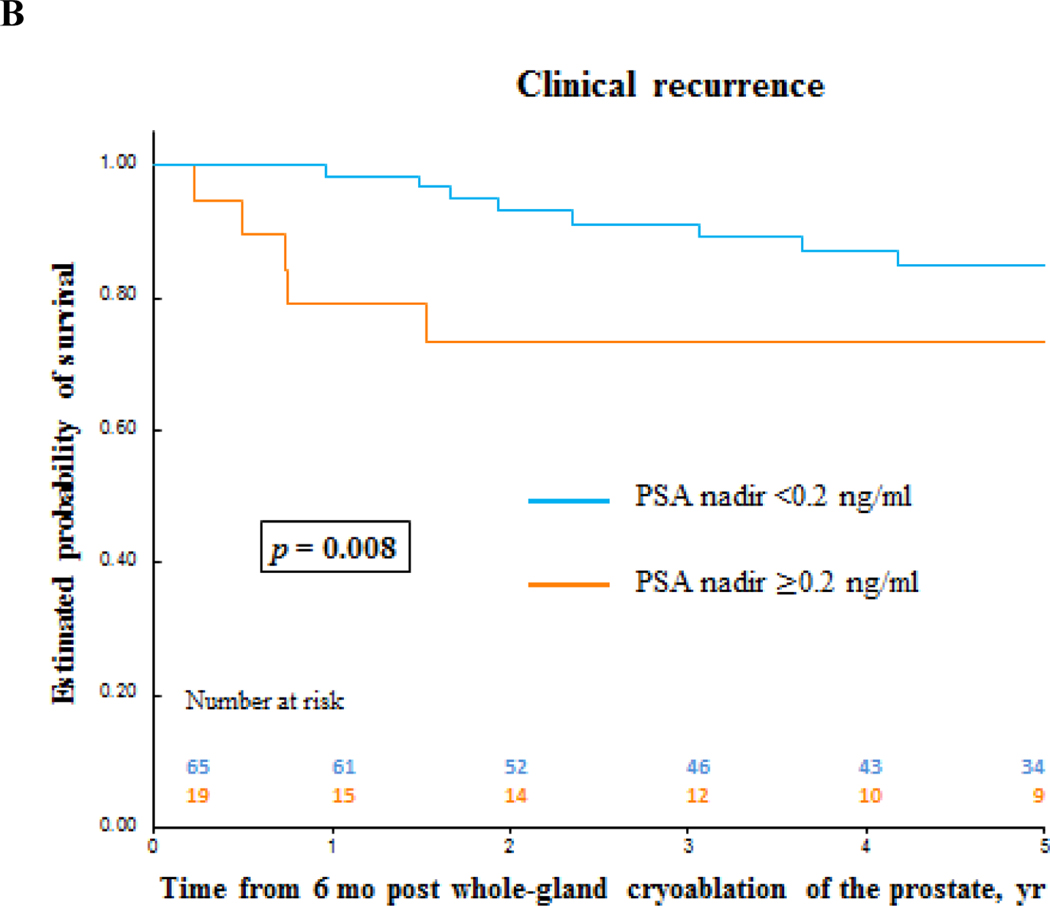

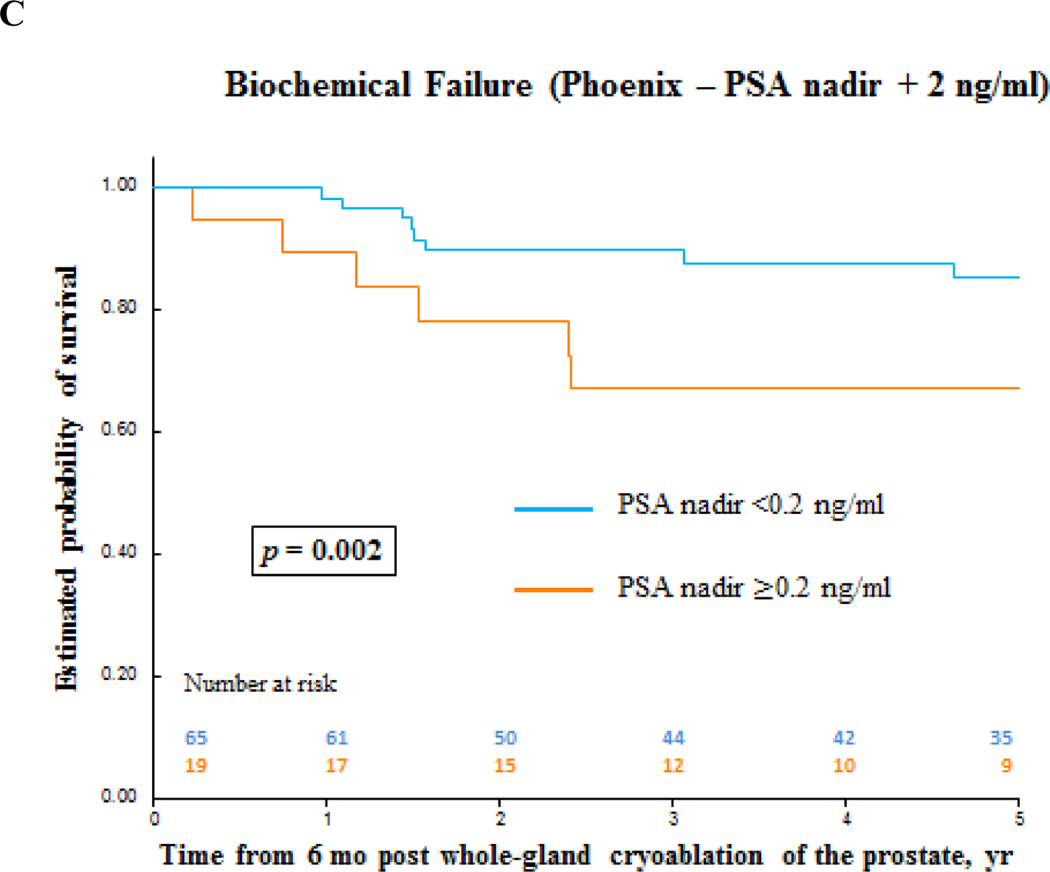

Oncologic outcomes are summarized in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Median (IQR) follow-up was 5.6 (3–7.9) yr (Table 3). According to PSA nadir + 2 ng/ml BF criteria, the median (IQR) follow-up was 5.6 (2.8–7.8) yr and 5.1 (3.5–7.5) yr for patients without BF and patients with BF, respectively. Median (IQR) time to PSA nadir was 3.3 (3–6.3) mo, and median nadir PSA was 0.1 (0.0–0.1) ng/ml. Seventy patients reached PSA <0.2 ng/ml. A total of 77 follow-up biopsies were performed in 45 patients with PCa found in nine patients (Table 3). Figure 2 shows PSA and PSA kinetics by CR and biopsy outcomes. Table 4 and Figures 3 and 4 show the estimated 5-yr BF-free survival and estimated 5-yr CR-free survival by different criteria. The 5-yr metastases-free survival was 95%. Two patients died, one from PCa originally diagnosed with intermediate-risk PCa. Multivariable analysis showed that failure to reach PSA nadir <0.2 ng/ml within 6 mo postcryoablation was as an independent predictor for BF (p = 0.006) and CR (p = 0.03; Table 5).

Table 3 –

Oncologic outcomes for whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate

| Parameter | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Follow-up time, yr | 5.6 (3.0–7.9) |

|

| |

| PSA nadir value, ng/ml | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) |

|

| |

| Time to PSA nadir, mo | 3.3 (3.0–6.3) |

|

| |

| Patients who reached PSA <0.2 ng/ml, n | 70 |

|

| |

| Follow-up biopsy sets, n | 77 |

|

| |

| Follow-up biopsy sets per patient, n | |

| 1 | 21 |

| 2 | 16 |

| 3 | 8 |

|

| |

| Patients with follow-up biopsy, n | 45 |

|

| |

| Patients with cancer on follow-up biopsy, n | 9 a |

|

| |

| Patients with recurrent disease b, n | 20 |

|

| |

| Patients with recurrent disease by baseline risk, n | |

| Low | 2 |

| Intermediate | 9 |

| High | 9 |

|

| |

| Type of recurrent disease, n | |

| Cancer on follow-up biopsy | 9 |

| 3+4 | 3 |

| 4+3 | 2 |

| 4+4 | 3 |

| 5+5 | 1 |

| Local invasion | 1 |

| Salvage treatment | 3 (EBRT n = 1, ADT n = 2) |

| Metastases c | 7 |

|

| |

| 5-yr metastases-free survival | 95% |

|

| |

| Patients died d, n | 2 |

|

| |

| Patients died from prostate cancer, n | 1 |

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; EBRT = external bean radiation therapy; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen;

Includes one patient with prostate cancer on cystoprostatectomy specimen.

Recurrent disease was defined as follows: cancer on follow-up biopsy, any evidence of clinical recurrence (by physical exam or imaging), or initiation of salvage treatment or androgen deprivation therapy. Clinical recurrence was detected in 20 (21%) patients: positive prostate biopsy, 8; prostate cancer in cystoprostatectomy specimen, 1; metastasis, 7; local invasion, 1; salvage treatment, 1; initiation of ADT, 2.

Of the seven patients with metastatic disease, three had high-risk and four intermediate-risk prostate cancer at entry. Two patients had bone metastases alone, two patients had lymph node metastases alone, and three patients had both bone and lymph node metastases.

One patient died of penile cancer.

Table 4 –

Biochemical failure and clinical recurrence outcomes post whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate

| Estimated 5-yr biochemical failure-free survival | Estimated 5-yr clinical recurrence-free survival a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Criteria | PSA ≥0.2 ng/ml, % | PSA nadir + 1.2 ng/ml (Stuttgart), % | PSA nadir + 2 ng/ml (Phoenix), % | Clinical recurrence, % |

| All patients | 47 | 78 | 81 | 83 |

| Low-risk PCa | 56 | 90 | 89 | 94 |

| Intermediate-risk PCa | 47 | 79 | 78 | 84 |

| High-risk PCa | 33 | 65 | 80 | 69 |

PCa = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Clinical recurrence was defined as follows: cancer on follow-up biopsy, any evidence of clinical recurrence (by physical exam or imaging), any salvage treatment or initiation of androgen deprivation therapy.

Table 5 –

Univariate and multivariate analysis for detecting predictors for biochemical failure and clinical recurrence post whole-gland cryoablation for prostate cancer

| Biochemical failure (PSA nadir + 2ng/mL, Phoenix) | Clinical recurrence b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| HR, 95% CI | p value | HR, 95% CI | p value | HR, 95% CI | p value | HR, 95% CI | p value | |

| Risk classification | ||||||||

| Intermediate vs low | 2.19, 0.61–7.89 | 0.24 | 1.96, 0.54–7.12 | 0.31 | 2.7, 0.58–12.6 | 0.21 | 2.48, 0.53–11.6 | 0.25 |

| High vs low | 2.07, 0.52–8.28 | 0.30 | 1.59, 0.39–6.46 | 0.92 | 5.38, 1.16–24.9 | 0.03 | 4.48, 0.96–21.0 | 0.06 |

|

| ||||||||

| Failed to reach PSA <0.2 ng/ml a | 3.75, 1.52–9.29 | 0.004 | 3.63, 1.45–9.05 | 0.006 | 3.24, 1.30–8.09 | 0.01 | 2.83, 1.12–7.11 | 0.03 |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Within 6 mo of follow-up.

Clinical recurrence was defined as follows: cancer on follow up biopsy, any evidence of clinical recurrence (by physical exam or image), any salvage treatment or initiation of androgen deprivation therapy.

Fig. 2 –

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) kinetics in follow-up of primary whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate by: (A) Clinical recurrence; (B) Biopsy outcomes. PSA values are shown as mean (standard deviation). Bx = biopsy; Cryo = cryoablation; CR = clinical recurrence; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

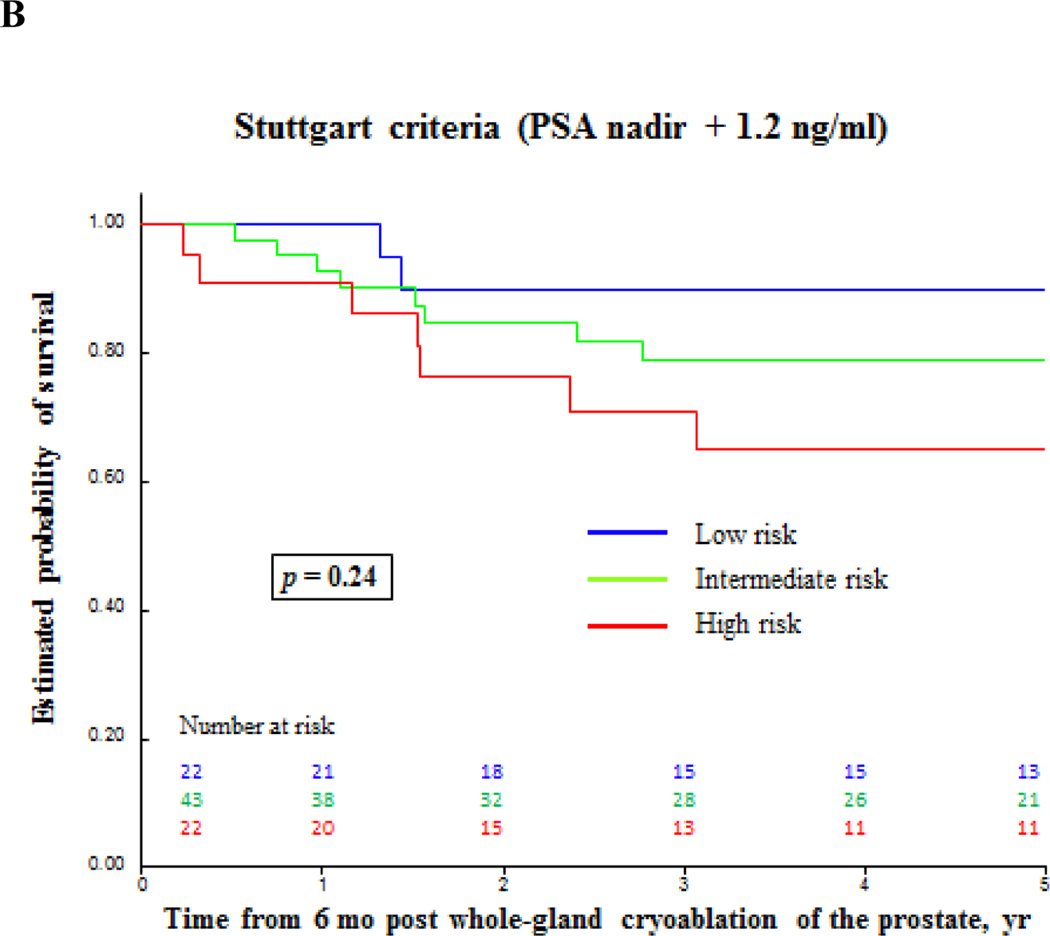

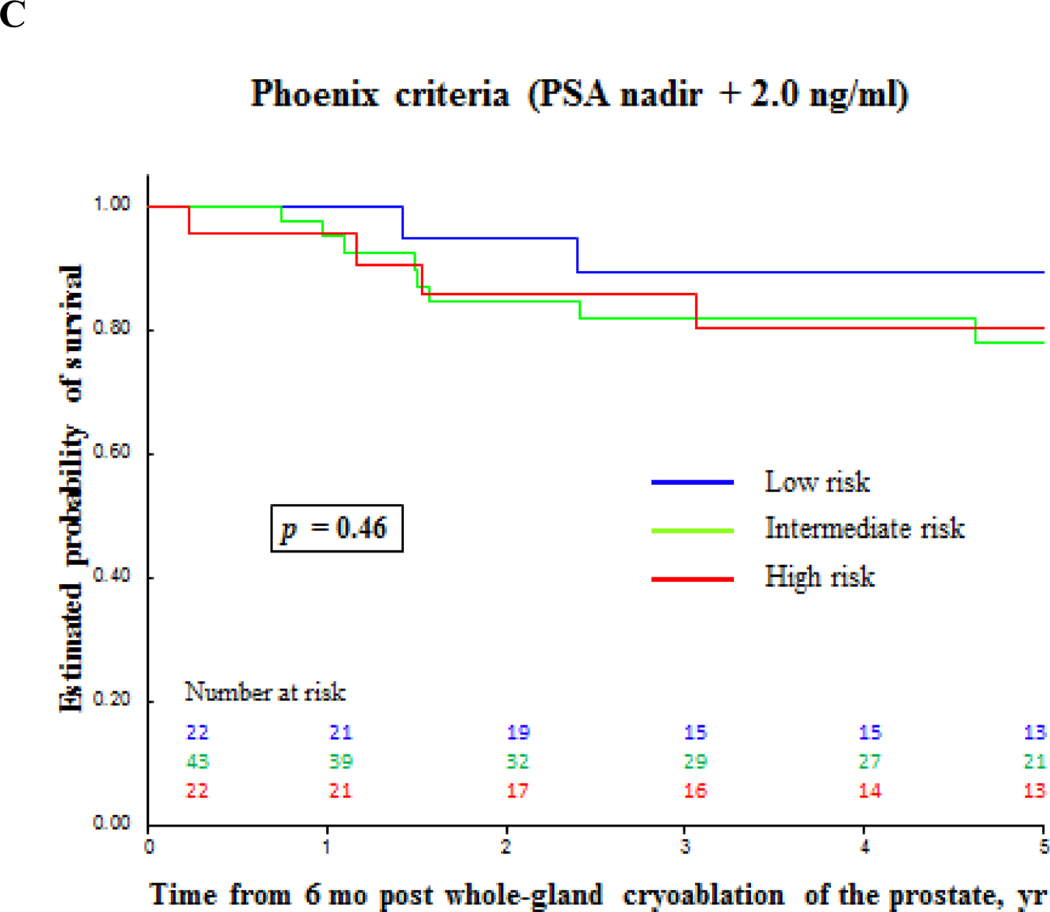

Fig. 3 –

Biochemical failure-free survival for prostate cancer after primary whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate accordingly to different definitions. (A) Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ≥ 0.2 ng/ml; (B) PSA nadir + 1.2 ng/ml; (C) PSA nadir + 2.0 ng/ml.

Fig. 4 –

Biochemical failure-free survival and clinical recurrence-free survival for prostate cancer after primary whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate. (A) Clinical recurrence-free survival by prostate cancer risk. (B) and (C) Clinical recurrence-free survival and biochemical failure-free survival by PSA nadir value. PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Functional outcomes were assessed within 2 yr of follow-up using the best score on patients’ self-reported questionnaires. Continence (use of no pads) and potency (patient reporting a score ≥3 on International Index of Erectile Function-5 question 2) were reported in 96% and 11% patients, respectively (Table 6). While whole-gland cryoablation has been associated with high rates of impotence [3], focal cryoablation is associated with potency in 86% of patients, with zero incontinence, and encouraging oncologic outcomes [6]. These may be improved by better patient selection with the use of multiparametric MRI.

Table 6 –

Functional outcomes post whole-gland cryoablation of the prostate

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Potency | |

|

| |

| Potent men pre-cryoablation | 34 (36) |

| Score for IIEF-5 question 2 (1–5) pre-cryoablation, n | |

| 1–2 | 60 |

| 3 | 7 |

| 4 | 6 |

| 5 | 21 |

| Score for IIEF-5 question 2 (1–5) postcryoablation, n | |

| 1–2 | 90 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 |

| Maintain potency postcryoablation | 4 (11) |

|

| |

| Continence | |

|

| |

| Continent men pre-cryoablation | 92 (98) |

| Retained continence postcryoablation a | 88 (96) |

IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

Functional outcomes were assessed, within 2 yr of follow up, using the best score on patients’ self-reported questionnaires.

Definition of continence: use of no pads.

Of the four patients that did not retain continence, three (75%) patients used only one pad per day.

Definition of potency: patient reporting a score 3 or more for IIEF-5 question 2: “When you had erections with sexual stimulation, how often were your erections hard enough for penetration (entering your partner)?”

Almost never or never

A few times (much less than half the time)

Sometimes (about half the time)

Most times (much more than half the time)

Almost always or always.

There is a lack of consensus on the definition of BF postcryoablation. We used the Phoenix criteria, which is used for patients with clinically localized PCa, with or without short-term neoadjuvant ADT [8]. Our data are in agreement with prior reports from the Cryo On-line Database registry [2,3] and randomized controlled trials [10].

Post-cryoablation biopsy rates range from 28% to 72% of patients, with an estimated positive biopsy rate of 7.7–23.5% [3,10]. The rate of post-cryoablation biopsy is influenced by PCa risk, biopsy protocol (mandatory vs for-cause), patient compliance, and follow-up time. A previous study reported that 72% patients underwent mandatory biopsy at 36 mo post-treatment, with 7.7% showing recurrent PCa [10]. It is noteworthy that in our study, patients with negative biopsy postcryoablation had similar PSA kinetics as those with no follow-up biopsy (Fig. 2B).

Predictors for CR post whole-prostate cryoablation still need to be explored [2,3]. After a comprehensive exploratory univariate analysis, various clinically relevant (ie, D’Amico risk stratification) and statistically significant parameters (ie, PSA nadir) were selected for multivariable analysis, demonstrating that failure to reach PSA nadir <0.2ng/ml within 6 mo post whole-gland cryoablation is an independent predictor for both BF and CR. It is noteworthy that high-risk PCa was a predictor for CR on univariate analyses (p = 0.03) and trended towards statistical significance (p = 0.06) on multivariable analysis.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature. Patients were selected by TRUS and biopsy rather than with MRI and MRI/TRUS fusion biopsy, which could add accuracy to staging and potentially provide better outcomes [11]. Similarly, MRI was not part of the follow-up protocol either, which may have identified recurrences earlier. Nevertheless, our data show that whole-gland prostate cryoablation is safe and provides acceptable medium-term oncologic outcomes that are comparable to other treatment modalities. Failure to reach PSA nadir <0.2 ng/ml within 6 mo postcryoablation is a predictor for BF and, more importantly, for CR.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Jie Cai for providing statistical support.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor:

This study was funded in part by grant R01 CA205058-01 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (I.S.G. and A.L.deCA.)

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: Andre Luis de Castro Abreu certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Cornford P, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2017;71:630–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Levy DA, Ross AE, ElShafei A, Krishnan N, Hatem A, Jones JS. Definition of biochemical success following primary whole gland prostate cryoablation. J Urol 2014;192:1380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jones JS, Rewcastle JC, Donnelly BJ, Lugnani FM, Pisters LL, Katz AE. Whole gland primary prostate cryoablation: initial results from the cryo on-line data registry. J Urol 2008;180:554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ukimura O, de Castro Abreu AL, Gill IS, Shoji S, Hung AJ, Bahn D. Image visibility of cancer to enhance targeting precision and spatial mapping biopsy for focal therapy of prostate cancer. BJU Int 2013;111:E354–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de Castro Abreu AL, Bahn D, Leslie S, et al. Salvage focal and salvage total cryoablation for locally recurrent prostate cancer after primary radiation therapy. BJU Int 2013;112:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bahn D, de Castro Abreu AL, Gill IS, et al. Focal cryotherapy for clinically unilateral, low-intermediate risk prostate cancer in 73 men with a median follow-up of 3.7 years. Eur Urol 2012;62:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].D’Amico AV, Moul J, Carroll PR, Sun L, Lubeck D, Chen MH. Cancer-specific mortality after surgery or radiation for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer managed during the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Roach M, Hanks G, Thames H, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:965–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Blana A, Brown SC, Chaussy C, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer: comparative definitions of biochemical failure. BJU Int 2009;104:1058–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Donnelly BJ, Saliken JC, Brasher PM, et al. A randomized trial of external beam radiotherapy versus cryoablation in patients with localized prostate cancer. Cancer 2010;116:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schoots IG, Roobol MJ, Nieboer D, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG. Magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsy may enhance the diagnostic accuracy of significant prostate cancer detection compared to standard transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2015;68:438–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]