Summary

Use of a complete dynamic model of NADP‐malic enzyme C4 photosynthesis indicated that, during transitions from dark or shade to high light, induction of the C4 pathway was more rapid than that of C3, resulting in a predicted transient increase in bundle‐sheath CO2 leakiness (ϕ).

Previously, ϕ has been measured at steady state; here we developed a new method, coupling a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope with a gas‐exchange system to track ϕ in sorghum and maize through the nonsteady‐state condition of photosynthetic induction.

In both species, ϕ showed a transient increase to > 0.35 before declining to a steady state of 0.2 by 1500 s after illumination. Average ϕ was 60% higher than at steady state over the first 600 s of induction and 30% higher over the first 1500 s.

The transient increase in ϕ, which was consistent with model prediction, indicated that capacity to assimilate CO2 into the C3 cycle in the bundle sheath failed to keep pace with the rate of dicarboxylate delivery by the C4 cycle. Because nonsteady‐state light conditions are the norm in field canopies, the results suggest that ϕ in these major crops in the field is significantly higher and energy conversion efficiency lower than previous measured values under steady‐state conditions.

Keywords: bundle‐sheath leakage, C4 photosynthesis, carbon isotope discrimination, maize, photosynthetic efficiency, photosynthetic induction, sorghum, tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy

Introduction

Photosynthetic energy conversion efficiency (ε c), the efficiency with which crops convert intercepted radiation into biomass, is a major limitation to the yield potential for both C3 and C4 crops (Zhu et al., 2008, 2010; Long et al., 2015). The ε c of C4 species has the intrinsic advantage of minimizing energy loss to photorespiration under most conditions, compared with C3 species (Long & Spence, 2013). Although only 3% of species use the C4 pathway, they account for 23% of terrestrial gross primary productivity (Sage et al., 2012). C4 species are also overrepresented in agricultural production in which just three C4 crops (maize, sugarcane and sorghum) account for 32% of global production (Long & Spence, 2013; FAO et al., 2020). All three are from a single C4 evolutionary clade, tribe Andropogoneae, and use the NADP malic enzyme (ME) for decarboxylation in the bundle sheath. Despite high productivity, even under optimum conditions, these C4 crops still fall well short of the theoretical maximum energy conversion efficiency of 6% in the field (Zhu et al., 2008, 2010; Dohleman & Long, 2009). Understanding the limitations to realizing the theoretical maximum in field conditions is key to increasing the productivity of C4 crops.

C4 photosynthesis includes a light energy‐driven CO2‐concentrating mechanism that increases the CO2 concentration around Ribulose‐1,5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) in bundle‐sheath cells, competitively inhibiting the oxygenation reaction, with the result that photorespiration is almost eliminated under normal conditions (Hatch, 1978, 1987; Edwards & Walker, 1983; Keeley & Rundel, 2003; Sage, 2004). Compared with C3 photosynthesis, C4 photosynthesis requires two additional ATP per CO2 assimilated in the regeneration of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), the initial acceptor molecule for CO2 in the mesophyll. However, as the bundle sheath is not hermetically sealed, an inevitable consequence of the high [CO2] gradient formed between bundle sheath and mesophyll cells is leakiness (ϕ). Leakiness describes the proportion of carbon fixed by PEP carboxylase (PEPC) and released by decarboxylation in the bundle sheath that diffuses back to the mesophyll. A variety of methods have estimated an average ϕ of 0.2 in C4 NADP‐ME species when measured at steady state in high light (Kromdijk et al., 2014). This means that for every five CO2 molecules released by decarboxylation of malate in the bundle sheath, one will diffuse back to the mesophyll, raising the cost per net CO2 assimilated by 0.5 ATP. Minimizing ϕ requires close coordination between the C3 and C4 cycles. Any elevation of ϕ indicates some lack of coordination between the two photosynthetic cycles and therefore a loss of photosynthetic efficiency (Henderson et al., 1992).

Although previous studies of C4 leakiness have focused on steady‐state conditions (Bellasio & Griffiths, 2014; Kromdijk et al., 2014; von Caemmerer & Furbank, 2016), leaves in crop fields are seldom under steady‐state conditions; instead these crop species experience frequent fluctuations in environmental conditions, especially light intensity. Intermittent cloud cover, the movement of leaves, and the changing solar angle over the course of a day cause dramatic and often abrupt changes in the light environment, including sunflecking within the crop canopy (Pearcy, 1990; Zhu et al., 2004; Slattery et al., 2018; Ohkubo et al., 2020; Sakoda et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Qiao et al., 2021; Long et al., 2022). The planting densities of these crops are increasing such that self‐shading and more frequent light fluctuations will continue to increase. Although light fluctuations at points on a leaf can occur in fractions of a second, the photosynthetic apparatus may require many minutes to adjust, potentially leading to losses of efficiency at the crop canopy level. This has led to a growing awareness of the need to address photosynthetic efficiency in fluctuating light (Hubbart et al., 2012; McAusland et al., 2016; Deans et al., 2019; Acevedo‐Siaca et al., 2020; De Souza et al., 2020; McAusland & Murchie, 2020; Murchie & Ruban, 2020). Much progress has been made in understanding the dynamic response to light in C3 plants in the past few years. Photosynthetic induction of C3 plants during shade‐to‐sun transitions is mainly influenced by three factors: activation of Rubisco, the speed of stomatal opening, and activation of the enzymes involved in RuBP regeneration within the C3 cycle (Pearcy, 1994; Mott & Woodrow, 2000; Kaiser et al., 2016; Slattery et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2022). Photosynthetic rate during induction is lower than that under steady‐state; however, the major factors limiting photosynthesis, primarily Rubisco activation and stomatal opening, vary among crop species and all represent a loss of potential efficiency (McAusland et al., 2016; Taylor & Long, 2017; Acevedo‐Siaca et al., 2020, 2021; De Souza et al., 2020).

When grown under fluctuating light, two C4 species (Setaria macrostachya and Amaranthus caudatus) showed a greater reduction in biomass than that observed in two C3 species (Triticum aestivum and Celosia argentea) relative to growth under steady‐state light (Kubásek et al., 2013). As rapid stomatal movement was reported in C4 plants (Bellasio et al., 2017; Ozeki et al., 2022), the biomass reduction suggests that C4 species may be more vulnerable to efficiency losses under fluctuating light, perhaps because of the need to coordinate between the two photosynthetic cycles. This finding was challenged by Lee et al. (2022) who compared carbon assimilation during fluctuating light to steady‐state across six C3 and six C4 species. Whereas Kubásek et al. (2013) made measurements during photosynthetic induction, Lee et al. (2022) examined plants that were fully acclimated to high light and suggested that differences between the two studies could be a result of photosynthetic induction causing lower coordination between C3 and C4 cycles.

A dynamic modeling simulation of C4 photosynthetic induction coupled with gas‐exchange measurements identified Rubisco activase, PPDK regulatory protein and stomatal conductance as the major limitations to the efficiency of NADP‐ME‐type photosynthesis during dark to high‐light fluctuations. The degree of influence of these limiting factors varied somewhat among single accessions of maize, sorghum and sugarcane (Wang et al., 2021). Owing to the complex compartmentation of the photosynthetic reactions between mesophyll and bundle‐sheath cells, the gas‐exchange measurements in Wang et al. (2021) were not able directly to investigate the relationship between the C4 and C3 cycles or determine leakiness during induction. However, a higher leakiness was predicted during induction compared with the steady state, as activation of the C4 dicarboxylate cycle appeared significantly faster than that of Rubisco in the bundle sheath, based on available kinetic data (Wang et al., 2021).

Steady‐state ϕ increases only slightly with decreasing light and varies little when measured at different [CO2], suggesting the C3 and C4 cycles are well coordinated under steady‐state conditions (Henderson et al., 1992; Ubierna et al., 2011, 2013; Bellasio & Griffiths, 2014; Kromdijk et al., 2014). However, little is known about how ϕ changes under nonsteady‐state conditions. Leakiness can be estimated by including measurements of photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (Kromdijk et al., 2014). Estimates of leakiness using stable isotopes compare the theoretical model of photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13C) (Farquhar, 1983; Farquhar & Cernusak, 2012) with measured photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13Cobs) (Kromdijk et al., 2014). Stable isotope discrimination can be estimated in real‐time using a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope (TDL) coupled to a gas‐exchange system (Barbour et al., 2007). In steady‐state measurements of ϕ, the TDL cycles through a set of calibration gases, and the infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) reference and leaf chamber. The TDL remains on each sample for a period of c. 30 s, thus allowing a single measurement every c. 120–360 s, precluding continuous monitoring of the leaf chamber. Recently, Sakoda et al. (2021) and Liu et al. (2022) estimated mesophyll conductance in C3 plants through induction using the steady‐state TDL method and were only able to measure c. 15 data points over a 30 min activation curve.

Here, we developed an experimental design that measures ϕ every c. 10 s over a 30 min induction. Based on our previous metabolic modeling (Wang et al., 2021) we hypothesized that leakiness will be higher during activation of C4 photosynthesis than during steady‐state conditions. The hypothesis is tested directly here from near‐continuous Δ13C discrimination measurements through induction of photosynthesis in maize and sorghum.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench, Tx430) and maize (Zea mays L., B73) plants were grown in a controlled‐environment glasshouse at the University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign. Temperature in the glasshouse was 28°C : 24°C, day : night. Plants were grown in 20 l pots filled with peat‐and‐perlite growing medium (BM6; Berger, Saint‐Modeste, QC, Canada). Measurements were taken on plants at 40 d after planting. Plants were kept in darkness for ≥ 30 min before measurement. The youngest fully expanded leaf on the main stem, as indicated by a fully emerged ligule, was selected for enclosure into the controlled‐environment measurement chamber.

Gas‐exchange measurements

For sorghum, the leaf was placed in the opaque conifer chamber (LI‐6400‐22; Li‐Cor Environmental, Lincoln, NE, USA) with an integrated RGB light source (LI‐6400‐18; Li‐Cor Environmental) attached to a LI‐6400XT gas‐exchange system (Li‐Cor Environmental). The chamber was fitted with a leaf thermocouple (Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA) (Fig. S1a). To minimize leakage from the chamber, an opaque flexible polymer sealant (Qubitac Sealant; Qubit Systems Inc., Kingston, ON, Canada) was applied around the chamber lips after enclosing the leaf (Fig. S1a). For maize, the leaf was placed in the large leaf and needle chamber (LI‐6800‐13; Li‐Cor Environmental) incorporating the large light source (LI‐6800‐03; Li‐Cor Environmental) (Fig. S1b). The flows to the reference and sample IRGAs were monitored to ensure that both analyzers received sufficient flow. Because maize has a large midvein, the sample chamber pressure was set to 0.1 kPa to ensure that any leaks were out of, not into, the sample chamber. The average (±SE) leakage from the chamber from all the maize measurements was 6.4 ± 1.9 μmol s−1, which accounted for 2.1 ± 0.68% of the flow. For both species, the leaf was placed in the chamber in darkness with a leaf temperature of 27°C, CO2 reference of 800 μmol mol−1, an [O2] of 21% and a flow rate of 300 μmol s−1. We controlled reference [CO2] to avoid artifacts caused by system adjustment. Reference CO2 of 800 μmol mol−1 was used to ensure that the sample [CO2] during the measurement is not lower than the ambient CO2. Leaf area was calculated as the product of the internal length of the chamber and the average of the width of the leaf at both ends of the chamber.

Isotopic gas‐exchange measurement

The gas‐exchange system was coupled to a TDL (model TGA 200A; Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA) to measure [12CO2], [13CO2] and δ13C (Bowling et al., 2003; Pengelly et al., 2010; Ubierna et al., 2013; Jaikumar et al., 2021). For sorghum, the reference line for the LI‐6400XT was split on the back of the sensor head so that a portion of the reference gas was diverted to the TDL. The exhaust gas from the leaf chamber was taken from the match port on the chamber, fitted with a three‐way valve to allow the gas to go to either the TDL or the match valve on the LI‐6400XT (Fig. S1a). For maize, the TDL was connected to the LI‐6800 reference air stream using the reference port on the back of sensor head while the port on the front of the head supplied air from the leaf chamber (Jaikumar et al., 2021; Fig. S1b). CO2‐free air (N2/O2) with a known [O2] was created by mixing two gas streams using precision mass flow controllers (Omega Engineering Inc.). A portion of this N2/O2 air traveled to the gas‐exchange system while the remainder was used as CO2‐free air in calibration to correct for drift in the TDL over the course of the measurements. The TDL was calibrated using the concentration series method by diluting a 10% CO2 gas cylinder into the N2/O2 stream to produce three different [CO2] of the same isotopic composition (Pengelly et al., 2010; Tazoe et al., 2011; Ubierna et al., 2013; Jaikumar et al., 2021). The measurement sequence cycled through eight gas streams in the following sequence: CO2‐free air, followed by three different CO2 concentrations of the same isotopic signature, air from a calibration tank with a known [12CO2], [13CO2], and δ13C composition (NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, Boulder, CO, USA), the IRGA reference and leaf chamber air streams, and the IRGA reference again. Each step had a duration of 20 s, except for the leaf chamber air, which had a duration of 600 s with a total cycle time of 740 s. Measurements were collected at a 10 Hz interval and averaged over 10 s as a single data point. The first 10 s of each gas stream was excluded to produce a single data point, except for the sample line which produced 59 data points each cycle. Instrument performance, including Allan deviations and instrument precision, are presented in Notes S1.

When the TDL switched to measuring the gas from the leaf chamber, the irradiance incident on the leaf was changed from 0 to 1800 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. The gas‐exchange system was set to auto‐log at 10 s intervals over the course of 30 min. Dark respiration rate was recorded before illumination.

Calculations of photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13C) and leakiness (ϕ)

Instantaneous online determination of observed photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13Cobs; Table 1) was calculated according to Evans & von Caemmerer (2013):

| (Eqn 1) |

where δ13Csamp and δ13Cref are the carbon isotope compositions of the leaf chamber and reference air, respectively, and ξ is:

| (Eqn 2) |

C ref and C samp are the [CO2] of dry air entering and exiting the leaf chamber, respectively, as measured by the TDL. For each measurement sequence, we averaged the [CO2] and δ13C of the reference air measured before and after the measurement of leaf chamber air.

Table 1.

List of symbols used in the text for calculating leakiness in maize and sorghum.

| Variable | Definition | Units | Equations/value/reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Fractionation across the stomata | ‰ | 4.4 (Craig, 1953; a s in Ubierna et al., 2013, 2018) | |

| a b | Fractionations across the boundary layer | ‰ | 2.9 | |

|

|

Weighted fractionation across the boundary layer and stomata in series | ‰ | Eqn 18 (Ubierna et al., 2013, 2018) | |

| Α | Rate of photosynthesis | μmol m−2 s−1 | Measured | |

| b 3 | 13C fractionation during carboxylation by Rubisco, including respiration and photorespiration fractionations | ‰ | Eqn 13 (Farquhar, 1983) | |

|

|

13C fractionation during carboxylation by Rubisco | ‰ | 30 | |

| b 4 | Net fractionation by CO2 dissolution, hydration and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) including respiratory fractionation | ‰ | Eqn 14 (Farquhar, 1983) | |

|

|

Net fractionation by CO2 dissolution, hydration and PEPC activity dependent upon temperature | ‰ | Eqn 15 | |

| C a | Ambient CO2 partial pressure | Pa | Measured in μmol mol−1 air | |

| C bs | CO2 partial pressure in the bundle‐sheath cells | Pa | Eqn 7 | |

| C i | CO2 partial pressure at the intercellular airspace | Pa | Measured in μmol mol−1 air | |

| C s | CO2 partial pressure at the leaf surface | Pa | Measured in μmol mol−1 air | |

| C ref | CO2 concentration of the dry air exiting the leaf chamber | μmol mol−1 | Measured | |

| C samp | CO2 concentration of the dry air exiting the leaf chamber | μmol mol−1 | Measured | |

| e | 13C fractionation during decarboxylation | ‰ | 0 (Evans & von Caemmerer, 2013; Ubierna et al., 2013) | |

| e′ | 13C fractionation during decarboxylation including the effect of a respiratory substrate isotopically distinct from recent photosynthate | ‰ | Eqn 16 | |

| E | Rate of transpiration | mol m−2 s−1 | Measured | |

| f | 13C fractionation during photorespiration | ‰ | 1.6‰ (Ubierna et al., 2013) | |

|

|

Total conductance to CO2 diffusion including boundary layer and stomatal conductance | mol m−2 s−1 | Measured | |

| g bs | Bundle‐sheath conductance to CO2 | mol m−2 s−1 | 0.00113 (Brown & Byrd, 1993) | |

| J t | Total electron transport rate | μmol m−2 s−1 | Eqn 3 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | |

| O m | O2 partial pressure in the mesophyll cells | Pa | 21.2 Pa atmospheric pressure | |

| O s | O2 partial pressure in the bundle‐sheath cells | Pa | Eqn 11 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | |

| R d | Leaf mitochondrial respiration in the light assumed to equal the rate of respiration in the dark | μmol m−2 s−1 | Measured | |

| R m | Rate of mesophyll cell respiration in the light | μmol m−2 s−1 | R m = 0.5R d | |

| s | Fractionation during leakage from the bundle‐sheath cells | ‰ | 1.8 (Henderson et al., 1992) | |

| t | Ternary effect | ‰ | Eqn 17 | |

| V c | Rubisco carboxylation rate | μmol m−2 s−1 | Eqn 9 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | |

| V o | Rubisco oxygenation rate | μmol m−2 s−1 | Eqn 10 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | |

| V p | PEP carboxylation rate | μmol m−2 s−1 | Eqn 8 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | |

| x | Fraction of J t allocated to the C4 cycle | 0.4 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | ||

| α | Fraction of PSII activity in the bundle sheath | 0 (von Caemmerer, 2000) | ||

| δ13Cgatm | Isotopic signature of growth CO2 | ‰ | −8 | |

| δ13Cref | Isotopic signature of the CO2 entering the leaf chamber | ‰ | Measured | |

| δ13Csamp | Isotopic signature of the CO2 exiting the leaf chamber | ‰ | Measured | |

| ξ | Ratio of the 12CO2 mole fraction in the dry air coming into the gas‐exchange cuvette over the difference in 12CO2 mole fractions of air in and out of the cuvette | unitless | Eqn 2 | |

| Δ13Cobs | Observed 13C photosynthetic discrimination | ‰ | Eqn 1 | |

| ϕ is | Leakiness estimated assuming infinite mesophyll conductance | Unitless | Eqn 12 |

The electron transport flux (J t) was calculated as (von Caemmerer, 2000; Ubierna et al., 2013):

| (Eqn 3) |

where

| (Eqn 4) |

| (Eqn 5) |

| (Eqn 6) |

R d is leaf mitochondrial respiration in the light, assumed to be equal to dark respiration, R m (R m = 0.5R d) is the rate of mesophyll cell respiration in the light, and A is the rate of net CO2 assimilation. C m is CO2 concentration in the mesophyll cells, which was assumed to equal measured C i, γ * is half of the reciprocal of Rubisco specificity (0.000193; von Caemmerer et al., 1994), O m is the O2 mol fraction in the mesophyll cells (210 000 μmol mol−1), and x is the portion of ATP used by the C4 cycle, assumed to equal 0.4 (von Caemmerer, 2000). The fraction of PSII activity in the bundle sheath (α) was assumed to be 0 for maize and sorghum (von Caemmerer, 2000). The bundle‐sheath conductance to CO2 (g bs) was set as 0.00113 mol m−2 s−1 (Brown & Byrd, 1993).

We calculated the CO2 partial pressure in the bundle‐sheath cells (C s), PEP carboxylation rate (V p), Rubisco carboxylation rate (V c), oxygenation rate (V o) and the O2 partial pressure in the bundle‐sheath cells (O s) using the following expressions (von Caemmerer, 2000):

| (Eqn 7) |

| (Eqn 8) |

| (Eqn 9) |

| (Eqn 10) |

| (Eqn 11) |

We estimated leakiness, assuming infinite mesophyll conductance, using the model proposed by Ubierna et al. (2013):

| (Eqn 12) |

where C a, and C i are the ambient and intercellular CO2 partial pressures, respectively, and t is the ternary effect (Farquhar & Cernusak, 2012). The fractionation during leakage from the bundle‐sheath cells (s) is 1.8‰, and b 3 and b 4 were defined as (Farquhar, 1983):

| (Eqn 13) |

| (Eqn 14) |

where f is fractionation during photorespiration, assumed to be 11.6‰ (Lanigan et al., 2008). (30‰) is Rubisco fractionation, and , the net fractionation by CO2 dissolution, hydration and PEPC activity at 27°C, was calculated according to Mook et al. (1974), which is used by Henderson et al. (1992) and von Caemmerer et al. (2014):

| (Eqn 15) |

We estimated e′, which is the 13CO2 fractionation during decarboxylation and takes into account respiration that is isotopically distinct from recent photosynthate, as previously discussed (Wingate et al., 2007; Ubierna et al., 2018):

| (Eqn 16) |

where e is the respiratory fractionation during decarboxylation, 0‰, δ13Cgatm is the isotopic signature of the CO2 in the air where the plants were grown, assumed to be −8‰, and δ13Cref is the isotopic signature of the measurement CO2 and was between −10‰ and −6.5‰.

The ternary effect (t) (Farquhar & Cernusak, 2012) takes into account the effect of transpiration on the rate of CO2 assimilation through the stomata and is calculated as:

| (Eqn 17) |

where E is the rate of transpiration, is the total conductance to CO2 diffusion from the atmosphere to the intercellular airspace including boundary layer and stomatal conductance (von Caemmerer & Farquhar, 1981), and denotes the combined fractionation factor through the leaf boundary layer and the stomata:

| (Eqn 18) |

where C s is the leaf surface CO2 partial pressure, a b (2.9‰) is the fractionation occurring through diffusion in the boundary layer, and a (4.4‰) is the fractionation as a result of diffusion in air (Craig, 1953).

The error associated with Δ13Cobs measurements

The error associated with Δ13Cobs was calculated according to Ubierna et al. (2018):

| (Eqn 19) |

where X is instrument precision (Notes S1). The error (%) was calculated as

Instrument precisions during the measurements were 0.24‰ and 0.14‰ for sorghum and maize, respectively. We excluded all data points where the error in Δ13Cobs was > 50%. This occurred in the first 144 s for sorghum and the first 110 s for maize.

Data processing

A fully automatic data processing and leakiness calculation tool was developed in Matlab. The tool used the pretreated (LI‐6400XT and LI‐6800) data files and the raw TDL data to calculate the leakiness through the photosynthetic induction, with the equations described earlier. The TDL data were averaged every 10 s to match the gas‐exchange data and to reduce noise (Fig. S2). See the Data availability statement for access to this tool.

Correction of the system delay

System delays were caused by both the large volume of the leaf chambers and the gas path from leaf chamber to the TDL (see Methods S1 for further information). The time delay from leaf chamber to the TDL was estimated by pulsing the leaf chamber with high CO2 and monitoring the time it took to observe the CO2 spike in the TDL. A 5‐cm‐wide paper strip was clipped into the chamber sealed with opaque flexible polymer sealant (Qubitac Sealant) to mimic the effect of the leaf on flow and mixing. The [CO2] was recorded every 2 s until the chamber outlet [CO2] was stable at 400 μmol mol−1 (Fig. S3). Three different flow rates were measured, 300, 500 and 700 μmol s−1. For each flow rate, the measurements were repeated three times. Results were used to estimate the chamber volume (V chamber) and time constant (τ), as defined later (https://www.licor.com/env/support/LI‐6400/topics/custom‐chamber.html).

Assuming the gas is well mixed in the chamber, for an open, flow‐through system, the [CO2] in the chamber C(t) at time t is:

| (Eqn 20) |

where C 0 is the initial chamber [CO2], C in is the incoming [CO2], V m is the molar volume of air, which was assumed to approximate an ideal gas at standard atmospheric pressure and 27°C, and is set as 24.6 l mol−1, f is the air flow rate (s) and V chamber is the chamber volume (l). Then, an ordinary differential equation model was used to estimate the system delay during photosynthetic induction measurement:

| (Eqn 21) |

where S leaf is the leaf area, A leaf (C) is the leaf carbon assimilation rate estimated by the gas‐exchange system at a given [CO2ref], and is the actual carbon assimilation rate. Here we set it as:

| (Eqn 22) |

where A f is the steady‐state photosynthesis rate at high light, τ A is the time constant of the induction of photosynthesis, and A f and τ A were set as 40 μmol m−2 s−1 and 300 s, respectively, according to gas‐exchange measurements.

Rubisco activation estimation

If the photosynthetic rate is limited by Rubisco, the maximum Rubisco activity is:

| (Eqn 23) |

Thus, the rate constant of Rubisco activation is equal to the rate constant of induction of CO2 assimilation. A semilogarithmic plot of the difference between A and steady‐state CO2 assimilation at 1800 μmol m−2 s−1 (A f) as a function of time during photosynthetic induction was plotted (Fig. S4). The linear portion of the semilogarithmic plot reflects an exponential phase in the time course that is proposed to be limited primarily by Rubisco (Woodrow & Mott, 1993; Wang et al., 2021). The slope of this linear portion is equal to the negative reciprocal of the time constant for CO2 assimilation and Rubisco activation (τ A = τ Rubisco). As Rubisco limits the later phase of the induction of C4 crops, we used the measured photosynthetic rate between 300 and 900 s for this estimation.

Statistical analyses

Normal distribution and homogeneity of variances were tested by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Student's t‐test was used to determine if the means of two datasets were significantly different from each other (P < 0.05). All statistical analyses used Python (v.3.7), Shapiro–Wilk test, Levene test and Student's t‐test were performed using the SciPy library. The piecewise function was fitted by linear and exponential goodness‐to‐fit regression (OriginPro v.2020; OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Results

Leakiness during photosynthetic induction in sorghum

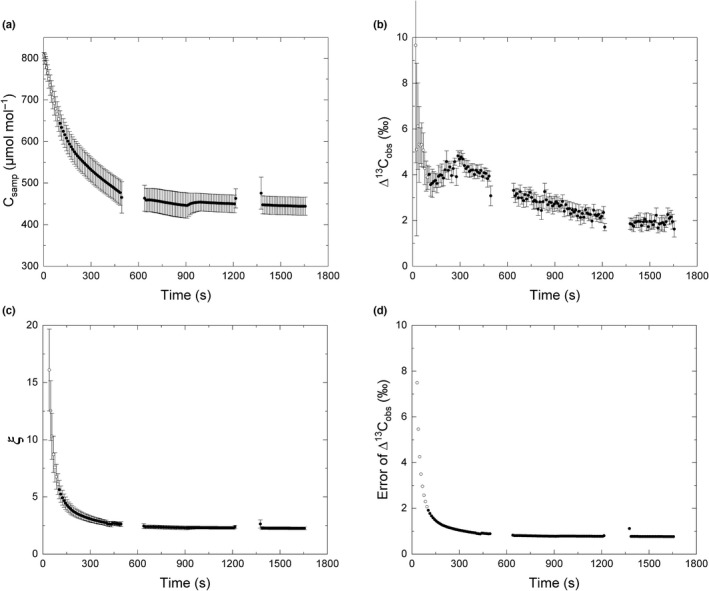

During the photosynthetic induction, sample [CO2] declined rapidly from 820 μmol mol−1 to a steady state of c. 450 μmol mol−1 at c. 600 s (Fig. 1a). Photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13Cobs) was used to estimate leakiness (ϕ), declining from an initial 10‰ to c. 3.5‰ at 120 s, then rising to 5‰ at 300 s and finally declining to a steady state of c. 2.0‰ at c. 1500 s (Fig. 1b). As expected, ξ, a measure of the uncertainty in Δ13Cobs was high (15) when rates of photosynthesis were low and decreased as A increased through induction, to a steady state of 2.5 at c. 600 s (Fig. 1c). The error of Δ13Cobs was higher than 2‰ (50% of Δ13Cobs) in the first 100 s of the measurement and quickly declined to around 1.2‰ (30% of Δ13Cobs) by 200 s (Fig. 1d; Table N1 in Notes S1).

Fig. 1.

Measured carbon isotope discrimination during photosynthetic induction of sorghum (Tx430) using a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope (TDL) coupled to a gas‐exchange system (LI‐6400XT). (a) Sample [CO2]; (b) the observed leaf photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13Cobs); (c) ξ, an estimate of the uncertainty in Δ13Cobs and ϕ calculations; (d) error of Δ13Cobs going from dark to high light (1800 μmol m−2 s−1). Time 0 s refers to when the light was switched on. Open dots represent the data points where the error of Δ13Cobs was > 50%. The TDL was calibrated after every 600 s of measurement. The gas from leaf chamber was not measured during the calibration and the measurement of reference gas (140 s), which occurred from c. 490 to 640 s and c. 1215 to 1365 s. Leaf gas‐exchange and carbon discrimination of the youngest fully expanded leaf was measured on 40‐d‐old sorghum (Tx430) plant. The leaf was dark‐adapted for 30 min before the measurement. Each data point is the mean (±SE) of eight plants (n = 8).

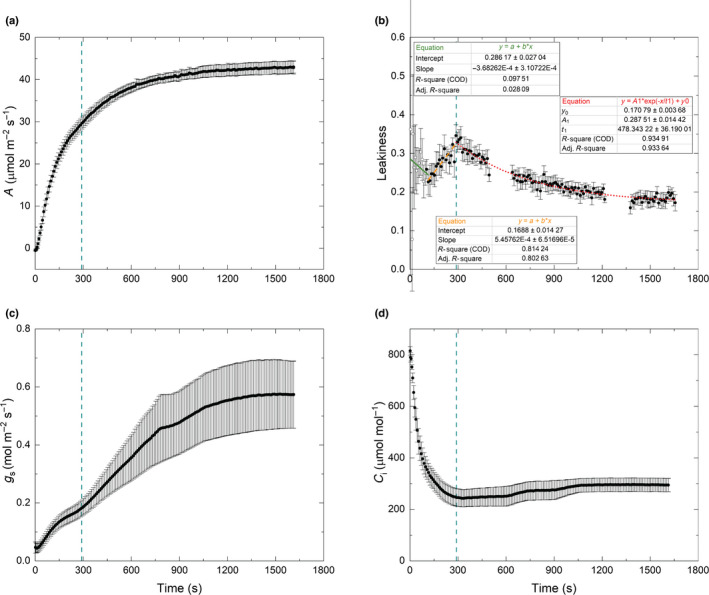

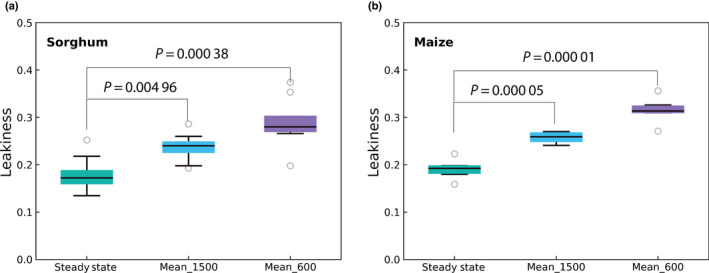

In the first 120 s in high light (1800 μmol quanta m−2 s−1), leakiness (ϕ) in sorghum declined from 0.32 to c. 0.23; however, ϕ then increased to c. 0.35 at 300 s, before gradually decreasing and reaching a steady state of c. 0.18 (Fig. 2b) at c. 1500 s. The leakiness curve was fitted with a piecewise function. No obvious trend was found in the first segment (R‐squared (R 2) = 0.098; Fig. 2b), which is also the segment with the greatest error of Δ13Cobs. The second segment of the piecewise function showed linear growth (R 2 = 0.81); during this time the error rapidly declined to < 50% of the associated measurement. The third segment was exponential decline (R 2 = 0.93; Fig. 2b). The transition time point of the leakiness curve of sorghum occurred at c. 290 s. Excluding the initial 100 s of measurement, given its high error of Δ13Cobs, the average (±SE) ϕ was 0.237 ± 0.012 over the 1500 s period of induction, which was 32% higher than the steady‐state ϕ in high light (0.180 ± 0.015, P = 0.005; Fig. 4a (see later); Table S1), indicating a substantial loss of efficiency during induction, compared with the steady state. The average ϕ value over the first 600 s period of induction was 0.289 ± 0.022, which was 61% higher than the steady‐state ϕ (P < 0.001; Fig. 4a (see later); Table S1). The reference [CO2] was set as 800 μmol mol−1 to minimize the limitations induced by stomatal and mesophyll conductance of CO2 to PEPC. In sorghum, intercellular [CO2] (C i) was always > 200 μmol mol−1, and so assumed not to be limiting to PEP carboxylation (Fig. 2d). Stomatal conductance to water vapor increased from 0.04 to c. 0.57 mol m−2 s−1 through the induction (Fig. 2c). The time constant of photosynthetic induction (τA) between 300 and 900 s was 332 s, which was assumed to reflect the kinetics of Rubisco activation (Eqn 21; Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of sorghum measured with an LI‐6400XT coupled to a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope (TDL). (a) CO2 assimilation rate (A). (b) Bundle‐sheath leakiness (ϕ, Eqn 12). Open dots represent the data points derived from values of observed discrimination that had large uncertainty (the error in the calculated Δ13Cobs was > 50% of its calculated value). (c) Stomatal conductance to water vapor (g s). (d) Intercellular CO2 concentration (C i). The dotted vertical lines mark the time of highest leakiness, which was 286 s. t 1 is the time constant (τ) of the exponential curve for leakiness. Time 0 s is when the light was switched on to 1800 μmol m−2 s−1. Each data point is the mean (±SE) of eight plants (n = 8).

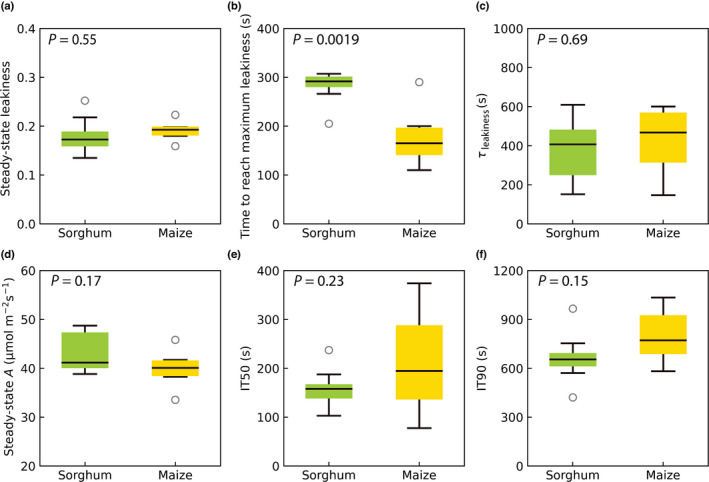

Fig. 4.

The comparison between steady‐state and transient leakiness in sorghum (a) and maize (b). Steady state, the average leakiness after 1500 s; Mean_1500, the average leakiness over the 1500 s period of induction; Mean_600, the average leakiness of the first 600 s in the induction. The data points with the error of Δ13Cobs > 50% were excluded. Data of each replicate were listed in Tables S1, S2. P‐values were calculated using Student's t‐test. Black circles represent the outliers; black lines in boxes show the medians. Upper and lower whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values, respectively.

Leakiness during photosynthetic induction in maize

During the dark to high‐light transition, leakiness increased faster in maize than in sorghum (Figs 3b, S8; see later). Similar to the measurement of sorghum, the error associated with Δ13Cobs estimation was > 50% for the first 90 s (Fig. S5d open circles) and photosynthetic discrimination rose rapidly to c. 120 s before a slow decrease to the steady state (Fig. S5b). As with sorghum, ξ was high when rates of photosynthesis were low and decreased with increasing rates of assimilation to a steady state at c. 600 s (Fig. S5c). ϕ during the photosynthetic induction in maize was fitted with the piecewise function. The first segment of the piecewise function was linear growth (Fig. 3b). The first segment of the piecewise function was linear increase, and R 2 of the linear regression was 0.57; however, the error of Δ13Cobs in this segment is large (Fig. S5d). After 110 s, ϕ during the induction can be fitted with an exponential decline function (Fig. 3b). The time constant of the exponential decline in ϕ was 540 s. The highest ϕ was c. 0.4 at 110 s. Excluding the initial 90 s of measurement, given its high error of Δ13Cobs, over the 1500 s period of induction, the average ϕ was 0.258 ± 0.006, which was 35% higher than the steady‐state ϕ at high light (0.191 ± 0.010). Average ϕ over the first 600 s period of induction was 0.315 ± 0.014, which was 65% higher than the steady state ϕ (P < 0.001; Fig. 4b; Table S2). As in the case of sorghum, intercellular [CO2] (C i) of maize was always > 200 μmol mol−1 (Fig. 3d). Stomatal conductance to water vapor increased from 0.02 to about 0.4 mol m−2 s−1 through induction (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of maize B73 measured with an LI‐6800 coupled to a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope (TDL). (a) CO2 assimilation rate (A). (b) Bundle‐sheath leakiness (ϕ, Eqn 12). Open dots represent data points derived from values of observed discrimination that had large uncertainty (the error in the calculated Δ13Cobs was > 50% of its calculated value). (c) Stomatal conductance to water vapor (g s); and (d) intercellular CO2 concentration (C i). The dotted vertical lines mark the time of highest leakiness, which was 110 s. t 1 is the time constant (τ) of the exponential curve for leakiness. Time 0 is when the light was switched on to 1800 μmol m−2 s−1. The TDL was calibrated after every 600 s of measurement. Each point is the mean (±SE) of six plants.

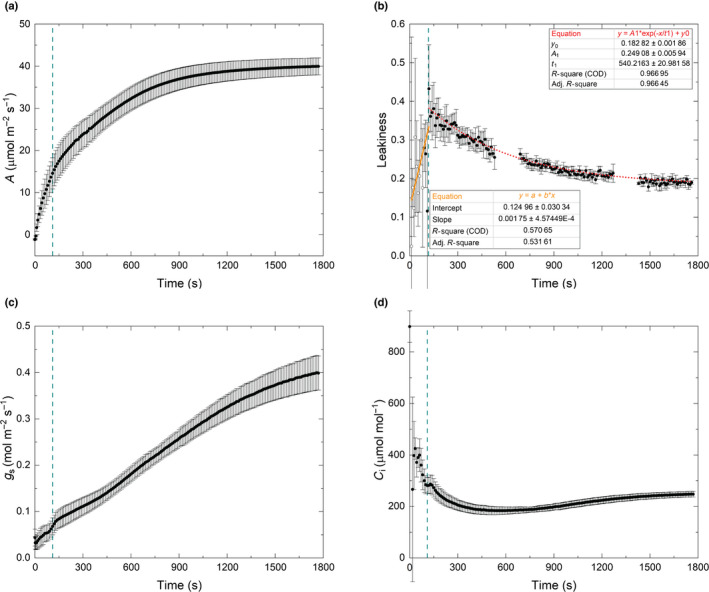

After 1800 s (30 min) in photosynthetic photon flux density of 1800 μmol m−2 s−1, maize and sorghum had similar rates of steady‐state CO2 assimilation and leakiness (Fig. 5a,d), and there was no significant difference between the species in the time taken for A to reach 50% and 90% of the steady‐state value, IT50 and IT90, respectively (Fig. 5e,f). However, the rise in leakiness in sorghum was significantly more prolonged than in maize, as indicated by the time taken to reach the peak of leakiness during induction (Fig. 5b). The speed of exponential decay of ϕ was similar, and there was no significant difference between the two species in ϕ (Fig. 5c), which is the time constant of exponential decline segment of the leakiness function (Figs 2b, 3b; curve‐fitting parameter t 1).

Fig. 5.

Mean and variation of steady‐state leakiness, the time to reach the maximum leakiness and the time constant of the exponential decay (τ leakiness), steady‐state CO2 assimilation rate (A), and IT50 and IT90 during the induction in sorghum and maize. (a) Average leakiness after 1500 s; (b) the time at the end of the linear growth segment of leakiness; (c) τleakiness, the time constant of exponential decline segment; (d) average A after 1500 s; (e) IT50, the time at which A reached 50% of the steady state; (f) IT90, the time at which A reached 90% of the steady state A. P‐values were calculated using Student's t‐test. Black circles represent the outliers; black lines in boxes show the medians; upper and lower whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values, respectively.

Discussion

Coordination between the C3 and C4 cycles was disrupted during photosynthetic induction

Coordination between the C3 and C4 cycles is essential to the high efficiency of C4 photosynthesis. We estimated CO2 leakiness with stable carbon isotopes by coupling a TDL to a gas‐exchange system. Leakiness (ϕ) is the proportion of CO2 released by decarboxylation of dicarboxylates in the bundle sheath that leaks back to the mesophyll. Any variation in ϕ reflects the degree of coordination between the two cycles.

A complete metabolic model of NADP‐ME photosynthesis, incorporating activation of enzymes, stomatal induction and dynamic changes in metabolic pools predicted poor coordination and transient increase in ϕ during photosynthetic induction, as a result of a more rapid activation of PPDK in the mesophyll by the PPDK regulatory protein, than activation of Rubisco in the bundle sheath by Rubisco activase (Wang et al., 2021). The transient increases in ϕ in both maize and sorghum observed here are fully consistent with this explanation.

Leaves in a crop canopy often face intense and rapid light changes (Zhu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020; Qiao et al., 2021). Over this 1500 s period of induction, the average ϕ was > 30% higher than the steady‐state ϕ at high light for sorghum and maize. Leakiness over the first 600 s was 61% higher than the steady‐state ϕ for sorghum and 65% for maize. The lack of coordination between C4 and C3 cycles will substantially reduce the efficiency of C4 photosynthesis at both leaf and canopy levels. Although the present study uses an extreme case of fluctuation (i.e. an immediate transfer from darkness to full sunlight), leaves in the canopy will frequently experience transfer from 10% to full sunlight (Long et al., 2022). A recent application of a high‐throughput assay of Rubisco activation has shown that deactivation on transfer to shade is very rapid, occurring within a minute (Taylor et al., 2022). So why has natural selection not removed this inefficiency? In the wild, many C4 plants, including wild ancestors of maize and sorghum, are most abundant in hot semiarid and nutrient‐poor regions (De Wet, 1978; Yang et al., 2019). As a result, leaf canopies may be sparse, and cloud cover infrequent. In these conditions there will be fewer light fluctuations and little selective pressure to avoid these transient increases in ϕ. The dense modern crop canopies of maize and sorghum are recent in an evolutionary context, but here the losses as a result of these transient inefficiencies would be much greater.

Differences of transient leakiness between sorghum and maize during induction

The induction rate of CO2 assimilation was similar between the two species, and a transient increase in leakiness was detected in both sorghum and maize (Figs 2a,b, 3a,b, S6). Leakiness reached a maximum significantly faster in maize than in sorghum (Fig. 5b), which most probably indicates faster activation of PPDK, possibly as a result of either more of its regulatory protein (PDRP) or a more efficient PDRP (Ashton et al., 1984; Burnell & Chastain, 2006; Wang et al., 2021). These results, consistent with the previous metabolic modeling of NADP‐ME C4 photosynthesis, through induction suggest activation of Rubisco as the key limitation through induction and the primary cause of lost efficiency. Rubisco activase (Rca) appears to be an exceptionally heat‐labile protein, implicated in loss of photosynthetic efficiency at high temperatures (Crafts‐Brandner & Salvucci, 2000). This implies that the loss of efficiency in these key crops would be amplified by rising global temperatures. This loss of efficiency might be overcome by breeding or engineering an increase in Rca content, and in particular more high‐temperature‐tolerant isoforms (Carmo‐Silva & Salvucci, 2013; Degen et al., 2021). Kim et al. (2021). These studies have shown that the redox‐regulated Rca‐α isoform is expressed in sorghum, sugarcane, maize and Sateria only at temperatures > 42°C and the time course of Rca‐α corresponds to recovery of Rubisco activation and the rate of photosynthesis from heat shock. However, overall variation in Rca in C4 crops has so far received little attention. Based on our estimation and previous studies, increasing the activity of Rca by either increasing Rca content or engineering a more efficient Rca would increase photosynthetic efficiency under constant and fluctuating light. Both now appear possible through bioengineering and possibly breeding (Long et al., 2022).

The high CO2 concentration supplied to the leaf chamber in our experiment (Figs 1a, S6a) minimized diffusional limitations (stomatal and mesophyll) to photosynthesis. During induction, the CO2 concentrations inside the leaf (C i) were > 200 and 180 μmol mol−1 for sorghum and maize, respectively (Figs 2d, 3d). Previous research (Wang et al., 2021) demonstrated that at ambient CO2 concentrations, slow stomatal opening during the middle phase of induction reduced both CO2 assimilation rate and leakiness in three C4 crops. The CO2 concentration used for measurements should have had a negligible effect on leakiness determined for the fast response of stomata in sorghum but could have impacted values for the slower response of stomata seen in maize. Mesophyll conductance (g m) could also be a limiting factor during induction. In this study, g m was assumed to be infinite and constant. There are no experimental data on the variation of g m during induction in C4 species. However, the main resistances to CO2 diffusion through, the cell wall and plasmalemma to the PEP carboxylase baring mesophyll cytoplasm, are probably unaffected by light, barring a Péclet effect with increasing outflow of water. This is a topic for subsequent investigation.

Energy‐use efficiency of C4 crops under fluctuating light

The steady‐state ϕ values were c. 0.2 in maize and sorghum; thus 5.5 ATP are used to assimilate one CO2. However, over the 1500 s period of the induction, the average ϕ was 0.25. Moreover, the average ϕ of the first 600 s was c. 0.30 in both sorghum and maize. The higher transient ϕ will have increased the ATP consumption of assimilating a CO2 to 5.7 and 5.9, respectively. The energetic cost of CO2 assimilation is therefore higher in fluctuating light than under steady‐state conditions. However, when light is in excess, as in induction, this will have little effect.

Variation in carbon assimilation during fluctuating light was previously observed by Lee et al. (2022) across four NADP‐ME grass species and may well arise from variation in the degree to which the C4 and C3 cycles are coordinated, as was shown here for maize and sorghum, but was not determined in their study. Being able to estimate variation in ϕ between species and genotypes during fluctuating light will be necessary for developing strategies to improve C4 crop performance. Additionally, low‐growth‐light intensity increases steady‐state ϕ of shaded field‐grown M. × giganteus leaves, assuming the C i in the bundle sheath is much higher than C i in the ϕ estimation (Kromdijk et al., 2008). Although the underlying basis of the increased ϕ in shade‐adapted leaves may be different from the increased ϕ in fluctuating light, these leakages could be additive, which would further handicap the efficiency of leaves within C4 canopies. We demonstrated a new experimental design with the TDL to estimate ϕ at high resolution and under transient conditions. This technique provides opportunities to investigate further the underlying causes of increased ϕ, as well as facilitating strategies to improve C4 plant performance in fluctuating light.

A new experimental design for the TDL with a gas‐exchange system

The coupling of a TDL with a gas‐exchange system has been used to measure leakiness in C4 plants under photosynthetic steady‐state conditions (Pengelly et al., 2010; Ubierna et al., 2011, 2013). Recent work has coupled gas‐exchange systems to a TDL to measure mesophyll conductance during induction curves (Sakoda et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022); however, these studies were only able to estimate mesophyll conductance every 120 s over the activation curve. Our method, allowing the TDL to remain on the leaf chamber for 600 s, enabled us to have a nearly continuous high‐resolution (10 s) dataset over a 30 min high‐light induction. This allowed the measurement of ϕ under nonsteady‐state conditions. The stability and precision of the instrument are critical to the accuracy of the estimation of ϕ (Fig. N1 in Notes S1). The error of our laser could be controlled within a limited range during the experiment, and the averaging time of 10 s significantly reduced the system noise and improved the prediction accuracy, with sufficient time resolution for the purposes of the questions asked in this study (Notes S1, laser performance). In the first c. 100 s of the induction, the error associated with Δ13Cobs estimation was > 50%, which indicated that our measurements were masked by instrument error. Thus, we minimized our interpretation of the leakiness values in this time frame. The error associated with photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13Cobs) was < 30% after 200 and 130 s for sorghum and maize, respectively, indicating that the error associated with the TDL was acceptable for the remainder of the induction. The error associated with the laser can change through time, environment and with retuning of the laser. These characters were verified for each laser and tested before each application. As CO2 concentration around Rubisco (C bs) should not be much higher than CO2 in mesophyll (C m) at the beginning of the induction, the complete calculation of leakiness (Eqn 12) was used instead of the simplified model that assumes the C bs is much higher than C m (Fig. S7). Additionally, we developed a program to calculate the leakiness automatically from raw carbon isotope and gas‐exchange data, which improved throughput of data analysis.

The accuracy of the measured gas‐exchange values was significantly improved by correcting for the time delay of the system (Figs S8, S9). The measuring noise of carbon isotope mole fractions was also constrained by averaging signals within every 10 s (Fig. N1 in Notes S1), and thus the noise in leakiness estimation was also reduced (Fig. S2), although the accuracy of the measurement was still limited by the precision of the gas‐exchange system and the TDL in the first c. 100 s after the illumination. We expect that our measurement experience and data‐processing program will help researchers to save time and develop new applications for this system.

Author contributions

The project was conceived by YW, SSS and SPL. YW and SSS performed the experiments. YW developed the data‐processing tool and analyzed the data. SSS developed the method for continual monitoring of leakage through induction. CJB and SSS set up the TDL. YW, SSS and SPL wrote the manuscript with insights from DRO, RAB and CJB. YW and SSS contributed equally to this work.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Pictures of the setup for the two gas‐exchange systems used for the measurements.

Fig. S2 Increasing the time averaged for each data point from 1 to 10 s significantly limited the estimation noise of the leakiness.

Fig. S3 The [CO2] of Li‐Cor 6400 opaque conifer chamber and Li‐Cor 6800 large leaf chamber (CO2S) changes with the decrease of influx [CO2] (CO2R) from 800 to 400 μmol mol−1.

Fig. S4 A semilogarithmic plot of the difference between the net CO2 assimilation (A) and steady‐state net CO2 assimilation at 1800 μmol m−2 s−1 (A f) as a function of time.

Fig. S5 Estimated bundle‐sheath leakiness, Δ13Cobs and ξ during photosynthetic induction of maize B73 calculated from tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope coupled to a gas‐exchange system (LI‐6800).

Fig. S6 Bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of maize B73 and sorghum Tx430.

Fig. S7 Estimated ϕ is is and ϕ i during photosynthetic induction of sorghum and maize.

Fig. S8 Time correction of CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of sorghum.

Fig. S9 Time correction of CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of maize.

Methods S1 Correction of the system delay.

Notes S1 Performance of tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope.

Table S1 Estimated values of leakiness and CO2 assimilation rate (A) of each individual sorghum plant.

Table S2 Estimated values of leakiness and CO2 assimilation rate (A) of each individual maize plant.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Acknowledgements

The sorghum work was supported by the DOE Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under award no. DE‐SC0018420) and the maize work by the project Realizing Increased Photosynthetic Efficiency (RIPE), which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, under grant no. OPP1172157. We thank Amanda P. de Souza, Jeff Hansen, Wei Wei, Elena Pelech, Elsa De Becker, Cindy Kher Xing Chan, Yi Xiao and Benjamin Haas for their comments and advice on earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank Dr Nerea Ubierna for helpful comments on previous drafts.

Data availability

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available at doi: 10.13012/B2IDB‐1181155_V1.

References

- Acevedo‐Siaca LG, Coe R, Wang Y, Kromdijk J, Quick WP, Long SP. 2020. Variation in photosynthetic induction between rice accessions and its potential for improving productivity. New Phytologist 227: 1097–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo‐Siaca LG, Dionora J, Laza R, Paul Quick W, Long SP. 2021. Dynamics of photosynthetic induction and relaxation within the canopy of rice and two wild relatives. Food and Energy Security 10: e286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton A, Burnell J, Hatch M. 1984. Regulation of C4 photosynthesis: inactivation of pyruvate, Pi dikinase by ADP‐dependent phosphorylation and activation by phosphorolysis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 230: 492–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour MM, McDowell NG, Tcherkez G, Bickford CP, Hanson DT. 2007. A new measurement technique reveals rapid post‐illumination changes in the carbon isotope composition of leaf‐respired CO2 . Plant, Cell & Environment 30: 469–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014. Acclimation to low light by C4 maize: implications for bundle sheath leakiness. Plant, Cell & Environment 37: 1046–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Quirk J, Buckley TN, Beerling DJ. 2017. A dynamic hydro‐mechanical and biochemical model of stomatal conductance for C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 175: 104–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling DR, Sargent SD, Tanner BD, Ehleringer JR. 2003. Tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy for stable isotope studies of ecosystem–atmosphere CO2 exchange. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 118: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RH, Byrd GT. 1993. Estimation of bundle sheath cell conductance in C4 species and O2 insensitivity of photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 103: 1183–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell JN, Chastain CJ. 2006. Cloning and expression of maize‐leaf pyruvate, Pi dikinase regulatory protein gene. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 345: 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. 2000. Biochemical models of leaf photosynthesis. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Hudson GS, Andrews TJ. 1994. The kinetics of ribulose‐1, 5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta 195: 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. 1981. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 153: 376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Furbank RT. 2016. Strategies for improving C4 photosynthesis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 31: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Ghannoum O, Pengelly JJ, Cousins AB. 2014. Carbon isotope discrimination as a tool to explore C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 3459–3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo‐Silva AE, Salvucci ME. 2013. The regulatory properties of Rubisco activase differ among species and affect photosynthetic induction during light transitions. Plant Physiology 161: 1645–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crafts‐Brandner SJ, Salvucci ME. 2000. Rubisco activase constrains the photosynthetic potential of leaves at high temperature and CO2 . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 97: 13430–13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig H. 1953. The geochemistry of the stable carbon isotopes. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 3: 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza AP, Wang Y, Orr DJ, Carmo‐Silva E, Long SP. 2020. Photosynthesis across African cassava germplasm is limited by Rubisco and mesophyll conductance at steady state, but by stomatal conductance in fluctuating light. New Phytologist 225: 2498–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wet J. 1978. Special paper: systematics and evolution of Sorghum sect. Sorghum (Gramineae). American Journal of Botany 65: 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Deans RM, Farquhar GD, Busch FA. 2019. Estimating stomatal and biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction. Plant, Cell & Environment 42: 3227–3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen GE, Orr DJ, Carmo‐Silva E. 2021. Heat‐induced changes in the abundance of wheat Rubisco activase isoforms. New Phytologist 229: 1298–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohleman FG, Long SP. 2009. More productive than maize in the Midwest: how does Miscanthus do it? Plant Physiology 150: 2104–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Walker D. 1983. C3, C4: mechanisms, cellular and environmental regulation of photosynthesis. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S. 2013. Temperature response of carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance in tobacco. Plant, Cell & Environment 36: 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO , IFAD , UNICEF , WFP , WHO . 2020. The state of food security and nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, Italy: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. 1983. On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Functional Plant Biology 10: 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA. 2012. Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant, Cell & Environment 35: 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. 1978. Regulation of enzymes in C4 photosynthesis. Current Topics in Cellular Regulation 14: 1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. 1987. C4 photosynthesis: a unique elend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Bioenergetics 895: 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. 1992. Short‐term measurements of carbon isotope discrimination in several C4 species. Functional Plant Biology 19: 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbart S, Ajigboye OO, Horton P, Murchie EH. 2012. The photoprotective protein PsbS exerts control over CO2 assimilation rate in fluctuating light in rice. The Plant Journal 71: 402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaikumar NS, Stutz SS, Fernandes SB, Leakey AD, Bernacchi CJ, Brown PJ, Long SP. 2021. Can improved canopy light transmission ameliorate loss of photosynthetic efficiency in the shade? An investigation of natural variation in Sorghum bicolor . Journal of Experimental Botany 72: 4965–4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Morales A, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Prinzenberg AE, Marcelis LF. 2016. Metabolic and diffusional limitations of photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance in Arabidopsis thaliana . Scientific Reports 6: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, Rundel PW. 2003. Evolution of CAM and C4 carbon‐concentrating mechanisms. International Journal of Plant Sciences 164(S3): S55–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Slattery RA, Ort DR. 2021. A role for differential Rubisco activase isoform expression in C4 bioenergy grasses at high temperature. GCB Bioenergy 13: 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Schepers HE, Albanito F, Fitton N, Carroll F, Jones MB, Finnan J, Lanigan GJ, Griffiths H. 2008. Bundle sheath leakiness and light limitation during C4 leaf and canopy CO2 uptake. Plant Physiology 148: 2144–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Ubierna N, Cousins AB, Griffiths H. 2014. Bundle‐sheath leakiness in C4 photosynthesis: a careful balancing act between CO2 concentration and assimilation. Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 3443–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubásek J, Urban O, Šantrůček J. 2013. C4 plants use fluctuating light less efficiently than do C3 plants: a study of growth, photosynthesis and carbon isotope discrimination. Physiologia Plantarum 149: 528–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanigan GJ, Betson N, Griffiths H, Seibt U. 2008. Carbon isotope fractionation during photorespiration and carboxylation in Senecio. Plant Physiology 148: 2013–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Boyd RA, Ort DR. 2022. The photosynthetic response of C3 and C4 bioenergy grass species to fluctuating light. GCB Bioenergy 14: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Barbour MM, Yu D, Rao S, Song X. 2022. Mesophyll conductance exerts a significant limitation on photosynthesis during light induction. New Phytologist 233: 360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Marshall‐Colon A, Zhu X‐G. 2015. Meeting the global food demand of the future by engineering crop photosynthesis and yield potential. Cell 161: 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Spence AK. 2013. Toward cool C4 crops. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64: 701–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Taylor SH, Burgess SJ, Carmo‐Silva E, Lawson T, DeSouza A, Leonelli L, Wang Y. 2022. Into the shadows and back into sunlight: photosynthesis in fluctuating light. Annual Reviews of Plant Biology 73: 617–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Murchie EH. 2020. Start me up; harnessing natural variation in photosynthetic induction to improve crop yields. New Phytologist 227: 989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Vialet‐Chabrand S, Davey P, Baker NR, Brendel O, Lawson T. 2016. Effects of kinetics of light‐induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water‐use efficiency. New Phytologist 211: 1209–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mook W, Bommerson J, Staverman W. 1974. Carbon isotope fractionation between dissolved bicarbonate and gaseous carbon dioxide. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 22: 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA, Woodrow IE. 2000. Modelling the role of Rubisco activase in limiting non‐steady‐state photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 51(Suppl 1): 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie EH, Ruban AV. 2020. Dynamic non‐photochemical quenching in plants: from molecular mechanism to productivity. The Plant Journal 101: 885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo S, Tanaka Y, Yamori W, Adachi S. 2020. Rice cultivar Takanari has higher photosynthetic performance under fluctuating light than Koshihikari, especially under limited nitrogen supply and elevated CO2 . Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki K, Miyazawa Y, Sugiura D. 2022. Rapid stomatal closure contributes to higher water use efficiency in major C4 compared to C3 Poaceae crops. Plant Physiology 189: 188–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. 1990. Sunflecks and photosynthesis in plant canopies. Annual Review of Plant Biology 41: 421–453. [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. 1994. Photosynthetic utilization of sunflecks: a temporally patchy resource on a time scale of seconds to minutes. In: Caldwell MM, Pearcy RW, eds. Exploitation of environmental heterogeneity by plants. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pengelly JJ, Sirault XR, Tazoe Y, Evans JR, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2010. Growth of the C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis: photosynthetic acclimation to low light through shifts in leaf anatomy and biochemistry. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 4109–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao M‐Y, Zhang Y‐J, Liu L‐A, Shi L, Ma Q‐H, Chow WS, Jiang C‐D. 2021. Do rapid photosynthetic responses protect maize leaves against photoinhibition under fluctuating light? Photosynthesis Research 149: 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2004. The evolution of C4 photosynthesis. New Phytologist 161: 341–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sage TL, Kocacinar F. 2012. Photorespiration and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63: 19–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoda K, Yamori W, Groszmann M, Evans JR. 2021. Stomatal, mesophyll conductance, and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis during induction. Plant Physiology 185: 146–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoda K, Yamori W, Shimada T, Sugano SS, Hara‐Nishimura I, Tanaka Y. 2020. Higher stomatal density improves photosynthetic induction and biomass production in Arabidopsis under fluctuating light. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery RA, Walker BJ, Weber AP, Ort DR. 2018. The impacts of fluctuating light on crop performance. Plant Physiology 176: 990–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SH, Gonzalez‐Escobar E, Page R, Parry MA, Long SP, Carmo‐Silva E. 2022. Faster than expected Rubisco deactivation in shade reduces cowpea photosynthetic potential in variable light conditions. Nature Plants 8: 118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SH, Long SP. 2017. Slow induction of photosynthesis on shade to sun transitions in wheat may cost at least 21% of productivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 372: 20160543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, Von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR. 2011. Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant, Cell & Environment 34: 580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Holloway‐Phillips M‐M, Farquhar GD. 2018. Using stable carbon isotopes to study C3 and C4 photosynthesis: models and calculations. In: Covshoff S, ed. Photosynthesis: methods in molecular biolody. New York, NY, USA: Humana Press, 155–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Cousins AB. 2011. The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions: assumptions and calculations with CO2 isotope discrimination. Journal of Experimental Botany 62: 3119–3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Kramer DM, Cousins AB. 2013. The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions in Zea mays, Miscanthus x giganteus and Flaveria bidentis . Plant, Cell & Environment 36: 365–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Burgess SJ, de Becker EM, Long SP. 2020. Photosynthesis in the fleeting shadows: an overlooked opportunity for increasing crop productivity? The Plant Journal 101: 874–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chan KX, Long SP. 2021. Toward a dynamic photosynthesis model to guide yield improvement in C4 crops. The Plant Journal 107: 343–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingate L, Seibt U, Moncrieff JB, Jarvis PG, Lloyd J. 2007. Variations in 13C discrimination during CO2 exchange by Picea sitchensis branches in the field. Plant, Cell & Environment 10: 600–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow IE, Mott KA. 1993. Modeling C3 photosynthesis – a sensitivity analysis of the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle. Planta 191: 421–432. [Google Scholar]

- Yang CJ, Samayoa LF, Bradbury PJ, Olukolu BA, Xue W, York AM, Tuholski MR, Wang W, Daskalska LL, Neumeyer MA. 2019. The genetic architecture of teosinte catalyzed and constrained maize domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 116: 5643–5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X‐G, Long SP, Ort DR. 2008. What is the maximum efficiency with which photosynthesis can convert solar energy into biomass? Current Opinion in Biotechnology 19: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X‐G, Long SP, Ort DR. 2010. Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annual Review of Plant Biology 61: 235–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Ort DR, Whitmarsh J, Long SP. 2004. The slow reversibility of photosystem II thermal energy dissipation on transfer from high to low light may cause large losses in carbon gain by crop canopies: a theoretical analysis. Journal of Experimental Botany 55: 1167–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Pictures of the setup for the two gas‐exchange systems used for the measurements.

Fig. S2 Increasing the time averaged for each data point from 1 to 10 s significantly limited the estimation noise of the leakiness.

Fig. S3 The [CO2] of Li‐Cor 6400 opaque conifer chamber and Li‐Cor 6800 large leaf chamber (CO2S) changes with the decrease of influx [CO2] (CO2R) from 800 to 400 μmol mol−1.

Fig. S4 A semilogarithmic plot of the difference between the net CO2 assimilation (A) and steady‐state net CO2 assimilation at 1800 μmol m−2 s−1 (A f) as a function of time.

Fig. S5 Estimated bundle‐sheath leakiness, Δ13Cobs and ξ during photosynthetic induction of maize B73 calculated from tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope coupled to a gas‐exchange system (LI‐6800).

Fig. S6 Bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of maize B73 and sorghum Tx430.

Fig. S7 Estimated ϕ is is and ϕ i during photosynthetic induction of sorghum and maize.

Fig. S8 Time correction of CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of sorghum.

Fig. S9 Time correction of CO2 assimilation and bundle‐sheath leakiness during photosynthetic induction of maize.

Methods S1 Correction of the system delay.

Notes S1 Performance of tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope.

Table S1 Estimated values of leakiness and CO2 assimilation rate (A) of each individual sorghum plant.

Table S2 Estimated values of leakiness and CO2 assimilation rate (A) of each individual maize plant.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available at doi: 10.13012/B2IDB‐1181155_V1.