Abstract

VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi, contains two invariable domains located at the amino and carboxyl terminal ends, respectively, and a central variable domain. In this study, both immunogenicity and antigenic conservation of the C-terminal invariable domain were assessed. Mouse antiserum to a 51-mer synthetic peptide (Ct) which reproduced the entire sequence of the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE from B. burgdorferi strain B31 was reacted on immunoblots with whole-cell lysates extracted from spirochetes of 12 strains from the B. burgdorferi sensu lato species complex. The antiserum recognized only VlsE from strain B31, indicating that epitopes of this domain differed among these strains. When Ct was used as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antigen, all of the seven monkeys and six mice that were infected with B31 spirochetes produced a strong antibody response to this peptide, indicating that the C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant. None of 12 monkeys and only 11 of 26 mice that were infected with strains other than B31 produced a detectable anti-Ct response, indicating a limited antigenic conservation of this domain among these strains. Twenty-six of 33 dogs that were experimentally infected by tick inoculation were positive by the Ct ELISA, while only 5 of 18 serum samples from dogs clinically diagnosed with Lyme disease contained detectable anti-Ct antibody. Fifty-seven of 64 serum specimens that were collected from American patients with Lyme disease were positive by the Ct ELISA, while only 12 of 21 European samples contained detectable anti-Ct antibody. In contrast, antibody to the more conserved invariable region IR6 of VlsE was present in all of these dog and human serum samples.

All variable antigens, such as the variant surface glycoprotein of the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei (4, 5, 31), the variable major protein (Vmp) of the spirochete Borrelia hermsii (23, 28), pilin of the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae (11), the major surface protein 2 of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale (8, 9, 24), and the variable surface antigen (VlsE) of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (14, 32–34), are immunodominant surface proteins which contain both variable and invariable portions. In the variant surface glycoprotein, Vmp, pilin, and major surface protein 2, immunodominance is contributed almost exclusively by their variable portions (1, 3, 6–9, 27). The latter are able to generate multiple serotypes for a given isolate, and thus, these variable antigens have little value for serodiagnosis. In contrast, VlsE contains several immunodominant invariable portions (16, 17), which are likely the molecular basis for the usefulness of this molecule in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease (15, 18, 20, 21; R. Murphree, B. J. Biggerstaff, and B. J. B. Johnson, Abstr. 100th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. V-10, p. 661, 2000).

VlsE has a predicted molecular mass of 34 kDa in the B31 strain of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (32). It contains two invariable domains, one at the amino and the other at the carboxyl terminus, which together encompass approximately one-half of the molecule's length; there is, in addition, one central variable domain (32). The latter contains six variable regions and six invariable regions (IRs), named IR1 to IR6 (16, 32). Regardless of their antigenicity, the variable portions probably have no diagnostic value. The six IRs remain unchanged during antigenic variation, and limited sequence data indicate that they are conserved among B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies and strains (14, 16, 32). Both IR2 and IR6 not only are immunodominant but are also antigenically conserved among the genospecies and strains of Lyme disease spirochetes (16, 17, 20, 21). Immunodominance of IR2 has been noted in selected host species, such as mice and dogs, but not humans or monkeys (17, 21). Thus, IR2 has no diagnostic value in human Lyme disease. Although IR2 is immunodominant in dogs, its diagnostic value is negligible (21). In contrast, IR6, when adapted to a peptide-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), has been shown to be a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic reagent both for human and canine Lyme disease (18, 20, 21). Like the six IRs, the two invariable domains are also unchanged during antigenic variation (32). It is not known if the sequences of these two domains are conserved among the genospecies and strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato since sequence data are available only for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 (32).

In the present study, immunogenicity of the C-terminal invariable domain was assessed in four host species, namely monkeys, mice, dogs, and humans. The antigenic conservation of this domain was investigated among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, and its potential diagnostic application in both human and canine Lyme disease was evaluated. Antibody to the C-terminal invariable domain of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 was generated in mice and allowed to react with immunoblots of whole-cell antigens extracted from 12 spirochetal strains that represented the three pathogenic genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. To determine immunogenicity and further assess antigenic conservation of the C-terminal domain of VlsE, serum specimens from monkeys and mice that were experimentally infected with different spirochetal strains were tested for antibody to a synthetic peptide (Ct) that reproduced the sequence of the C-terminal invariable domain of strain B31. To examine the potential diagnostic value of the Ct peptide, sera from dogs that were either clinically diagnosed with Lyme disease or experimentally infected with B. burgdorferi and from human patients with Lyme disease were also tested for anti-Ct antibody levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Spirochete strains.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains B31, Sh-2-82, NT1, JD1, and N40, Borrelia garinii strains IP90, G1, G25, NBS23A, and NBS16, and Borrelia afzelii strains J1 and P/Gau were cultivated in BSK-H medium supplemented with 10% rabbit serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Spirochetes grown to stationary phase were used in this study.

Peptide synthesis and conjugation to biotin and KLH.

Two peptides were prepared using the fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl synthesis protocol (2). The Ct peptide (CEGAIKGAAESAVRKVLGAITGLIGDAVSSGLRKVGDSVKASKET PPALNK) reproduced the sequence of the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE from the B. burgdorferi clonal isolate B31-5A3 (32). The C6 peptide (CMKKDDQIAAAMVLRGMAKDGQFALK) was synthesized based on the IR6 sequence of VlsE cloned from B. garinii strain IP90 (16). The cysteine residue that was included at the N terminus of each synthetic peptide was used as the conjugation site. Conjugation to biotin or keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) was performed by the N-succinimidyl maleimide carboxylate method. The maleimide reagent was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.), and the protocol suggested by the manufacturer was followed.

Preparation of antibodies to peptides Ct and C6.

To generate antiserum to the Ct peptide, mice (6- to 8-week-old C3H/HeN; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were given three intraperitoneal injections at 3-week intervals of 100 μg of Ct-KLH conjugate emulsified with MPL and TOM adjuvant (Sigma). Two weeks after the last injection, the titer of antibody to the Ct peptide was assessed by ELISA. To generate antibody to the C6 peptide, 6-month-old New Zealand White rabbits were given three subcutaneous doses at biweekly intervals of 200 μg of C6-KLH conjugate emulsified with Freund's complete (first injection) or incomplete (remaining injections) adjuvant. Ten days after the last injection, the antibody titer was determined by the C6 ELISA.

Peptide-based ELISA.

Ninety-six-well ELISA plates were coated with 100 μl per well of 4 μg of streptavidin (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, Ill.)/ml in coating buffer (0.1 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.2) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The remaining steps were conducted in a rotatory shaker at room temperature. After two 3-min washes with 200 μl per well of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (pH 7.4) (PBS/T) at 200 rpm, 200 μl of 5 μg of biotinylated peptide (Ct or C6)/ml dissolved in blocking solution (PBS/T supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk) was applied to each well. The plate was shaken at 200 rpm for 2 h. After three washes with PBS/T, 50 μl of mouse, monkey, dog, or human serum diluted 1:200 with blocking solution was added to each well. The plate was incubated at 200 rpm for 1 h and then washed three times with PBS/T. Each well then received 100 μl of 0.5 μg of goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (heavy and light chain specific; Sigma)/ml, 0.5 μg of goat anti-monkey IgG (γ chain specific; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.)/ml, 0.35 μg of rabbit anti-dog IgG (heavy and light chain specific; Sigma)/ml, or 0.1 μg of goat anti-human IgG (heavy and light chain specific; Pierce)/ml, as appropriate. All additives were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and were dissolved in blocking solution. The plate contents were incubated for 1 h while being shaken. After three washes with PBS/T each for 3 min, the antigen-antibody reaction was probed using the TMB microwell peroxidase substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry), and color was allowed to develop for 10 or 25 min depending on the host species tested. The enzyme reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M H3PO4. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm.

Immunoblotting.

Spirochetes grown to stationary phase were harvested and washed twice with PBS by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Washed spirochetes were suspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (125 mM Tris, 3% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue [pH 6.8]) at a concentration of 2.5 × 109 organisms per ml. The suspension was incubated at 95°C for 5 min. Approximately 15 μl of such preparation was applied to each sample lane of a 15-well minigel of 12% acrylamide. Resolved proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose in Towbin transfer buffer (30). The blot was shaken in blocking solution for 2 h and then in the same solution supplemented with either 1:500 diluted mouse anti-Ct serum or 1:1,000 diluted rabbit anti-C6 serum for an additional 2 h. After 3 washes with PBS/T, the blot was incubated in 2.0 μg of goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate per ml for 1 h. After three washes with PBS/T, the blot was developed in PBS/T supplemented with 0.05% 4-chloro-naphthol, 0.015% H2O2, and 17% methanol.

Monkey serum specimens.

Serum specimens from 19 B. burgdorferi-infected rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were used in this study. All of the animals were infected by the bite of Ixodes scapularis nymphal ticks as described previously (25). Seven animals were infected with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31 (animals L379, L452, L453, L457, L549, M021, and M581), six animals with strain JD1 (J200, J831, K205, K216, K383, and L131), and six animals with NT1 (P285, P607, R383, R454, R817, and V591). Blood samples were drawn at 8 to 10 weeks postinfection.

Mouse serum specimens.

Serum specimens from 32 B. burgdorferi-infected mice were examined. Eighteen mice were of the C3H/HeN strain, and 14 were BALB/c. Animals of both strains were 6 to 8 weeks old. Six of the C3H mice were inoculated with B. burgdorferi strain B31 (mice 184, 191, 194, 196, 408, and 409) by tick bite as described elsewhere (22). The remainder of the C3H mice were needle inoculated with strains N40 (n = 2; Q53 and Q59), JD1 (n = 5; A77, A78, A79, A80, and A81), and Sh-2-82 (n = 5; 219, 220, 228, 288, and 289). Each mouse received 106 cultured spirochetes administrated by subcutaneous injection. Blood samples were drawn at 4 weeks postinfection.

The BALB/c mice were infected with European strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato by exposure to nymphal Ixodes ricinus ticks, as described previously (10, 13). These ticks were field collected either in Malonne, Belgium, or Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Seven mice were exposed to ticks from Neuchâtel (animals N57, N59, N63, N65, N67, N69, and N71) and the remainder (animals M50, M52, M54, M56, M58, M62, and M64) were exposed to Malonne ticks. Spirochetes were isolated from all of the mice that were exposed to Neuchâtel ticks by ear punch biopsy culture. Spirochete species were identified by a standard protocol described previously (26). Spirochetes from Malonne ticks were not classified. Blood samples were drawn at 4 weeks postinfection. Serum specimens from mice infected with European spirochetes were kindly provided by Lise Gern (University of Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland) and by Vincent Weynants (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium).

Dog serum specimens.

Thirty-three 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free beagles of both sexes were infected by tick bite as described previously (29). Serum specimens collected at 8 weeks postinoculation were used in this study. The specimens were kindly provided by Reinhard Straubinger (Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.).

Eighteen dog serum specimens (a gift from Richard Jacobson, Cornell University) were also used in this study. These samples were originally submitted for the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease and were collected from dogs that were suspected to have Lyme disease. They were submitted from different areas of the United States.

Ten control serum specimens (a gift from Amy Grooters, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La.) were collected from healthy dogs in Louisiana. This panel of serum specimens was used to calibrate a cutoff value for the ELISA. Lyme disease is not endemic in Louisiana, and the dogs had no history of travel to areas of endemicity.

Human serum specimens.

Six panels of human serum specimens were used in this study. Twenty samples (CDC1 to CDC20) were kindly provided by Martin Schriefer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo.). This serum panel was collected from convalescent Lyme disease patients. Thirty-four serum specimens (T1 to T34) were kindly provided by Allen Steere (Tufts University, Boston, Mass.). These serum samples were collected from patients with late Lyme arthritis or neuroborreliosis. Ten serum specimens (NIH1 to NIH10) were collected from patients with posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) and were provided by Adriana Marques (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.).

Two additional serum panels were from European patients. Thirteen serum specimens (A1 to A13) were collected from Austrian patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. The Austrian panel was kindly provided by Elisabeth Aberer (University of Graz, Graz, Austria). Eight samples (I1 to I8) were from Italian patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, Lyme arthritis, or neuroborreliosis. The Italian panel was kindly provided by Marina Cinco (Università Trieste, Trieste, Italy).

Ten control human serum samples were collected from patients of a local hospital in Louisiana. Lyme disease is not endemic in this area. This serum panel was used to calibrate a cutoff value for the ELISA.

RESULTS

Epitopes of the C-terminal invariable domain differ among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato.

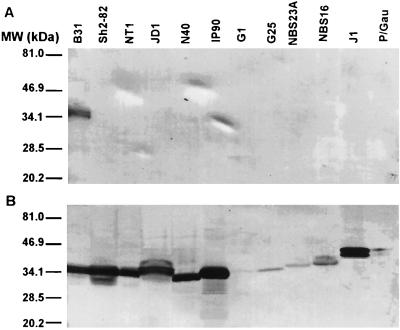

Although the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE remains unchanged during antigenic variation (32), it is not known if this sequence is generally conserved among strains and genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. To address this issue, antibodies to Ct, a peptide which reproduces the sequence of the C-terminal invariable domain of strain B31, and to C6, which was designed based on the sequence of IR6 of strain IP90, were reacted with whole-cell extracts from 12 spirochetal strains on immunoblots. These included B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains B31, Sh-2-82, NT1, JD1, and N40; B. garinii strains IP90, G1, G25, NBS23A, and NBS16; and B. afzelii strains J1 and P/Gau. Anti-Ct antibody recognized only the VlsE antigen expressed by strain B31 but not that expressed by the other 11 strains. This result indicates that epitopes of the C-terminal domain are not conserved among these strains (Fig. 1A). Loss of the plasmid lp28-1, which carries the vlsE locus, or lack of VlsE expression in vitro could not explain absence of reactivity, as the 12 strain isolates that were used in this experiment expressed an antigen that reacted with the anti-C6 antibody, albeit weakly in some cases (Fig. 1B). This result also illustrates the antigenic conservation of IR6.

FIG. 1.

Epitopes of the C-terminal invariable domain differ among strains and genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. Whole-cell lysates of strains B31, Sh-2-82, NT1, JD1, N40, IP90, G1, G25, NBS23A, NBS16, J1, and P/Gau were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose. Blots were reacted with either mouse anti-Ct antiserum (A) or rabbit anti-C6 antiserum (B). Molecular masses (MW) are depicted in kilodaltons (kDa) at the left of the figure.

The C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant during a B. burgdorferi infection but antigenically scarcely conserved among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato.

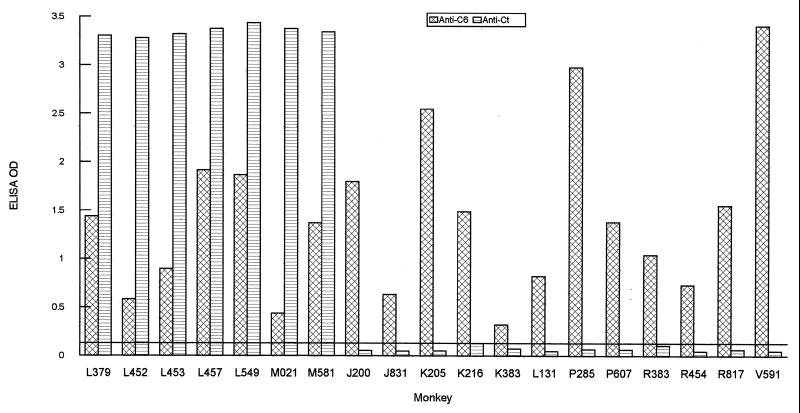

In a previous study, all four mice that were infected with B. burgdorferi B31 showed a strong antibody response to the C-terminal invariable domain (22). To further determine if this domain is immunodominant during B. burgdorferi infection, serum specimens from seven monkeys and six mice that were infected with B31 spirochetes by tick inoculation were tested. A strong antibody response to the C-terminal invariable domain was detected in all of the animals (Fig. 2, monkeys L379, L452, L453, L457, L549, M021, and M581, and 3, mice 184, 191, 194, 196, 408, and 409) as assessed by the Ct ELISA. These results indicated that the C-terminal invariable domain was immunodominant during B. burgdorferi infection regardless of host species.

FIG. 2.

The C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant but is not antigenically conserved among strains of B. burgdorferi in monkeys. Monkeys were infected with B. burgdorferi strain B31 (monkeys L379, L452, L453, L457, L549, M021, and M581), JD1 (monkeys J200, J831, K205, K216, K383, and L131) or NT1 (monkeys P285, P607, R383, R454, R817, and V591) by tick bite. Levels of antibody to IR6 and the C-terminal invariable domain were assessed using C6 and Ct ELISAs, respectively. The cutoff value (0.113) was based on the mean OD plus 3 standard deviations of 10 monkey prebleeds when the two peptides were separately used as an ELISA antigen.

To determine if the C-terminal invariable domain is antigenically conserved among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, serum specimens from monkeys and mice that were infected with spirochetal strains other than B31 either by needle inoculation or tick bite were assessed. None of the 12 monkeys that were infected with either JD1 (monkeys J200, J831, K205, K216, K383, and L131) or NT1 spirochetes (monkeys P285, P607, R383, R454, R817, and V591) produced a detectable antibody response to the Ct peptide (Fig. 2). In contrast, antibody to IR6 was detected in all animals by C6 ELISA (Fig. 2). This latter result ruled out the possibility that the spirochetes infecting these animals did not express VlsE or had lost lp28-1, the plasmid that carries the vlsE locus. Since the C-terminal invariable domain appears to be immunodominant, the negative Ct ELISA results are most likely due to lack of antigenic conservation of the C-terminal invariable domain expressed by these strains.

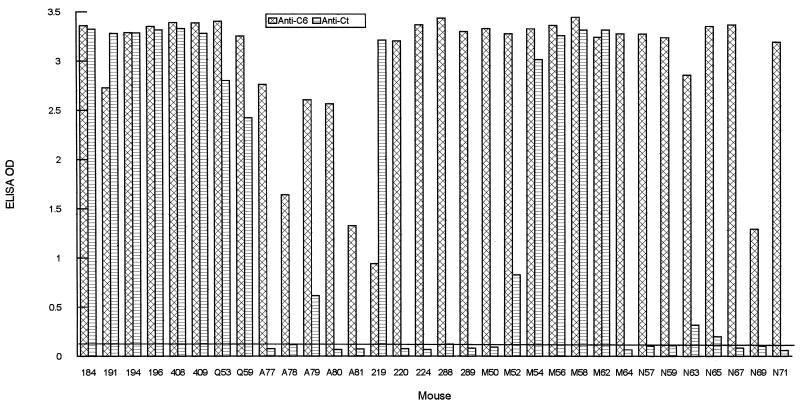

Slightly different results were obtained with mice. The two mice that were infected with strain N40 (mice Q53 and Q59), one of the five mice that were infected with strain JD1 (mice A77, A78, A79, A80, and A81) and one of the five mice that were infected with strain Sh-2-82 (mice 219, 220, 224, 288, and 289) produced a significant antibody response to the Ct peptide (Fig. 3). Five of the seven mice that were infected by Malonne ticks (mice M50, M52, M54, M56, M58, M62, and M64) contained a high level of antibody to Ct, while only two of the seven mice infected with Neuchâtel ticks (mice N57, N59, N63, N65, N67, N69, and N71) produced a weak antibody response to this peptide (Fig. 3). Strong antibody responses to IR6 in all of the 32 mice indicated, as with monkeys, that VlsE was expressed (Fig. 3). Since the C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant, antibody to this domain should have been elicited in all of the infected mice. Therefore, failure to detect anti-Ct antibody in most of the infected mice (only 11 of the 26 infected mice responded to Ct) is likely due to lack of antigenic conservation of the C-terminal invariable domain.

FIG. 3.

The C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant, but its antigenic conservation is limited among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in mice. Eighteen C3H mice were infected either with strain B31 (184, 191, 194, 196, 408, and 409) by tick inoculation or with strain N40 (Q53 and Q59), JD1 (A77, A78, A79, A80, and A81), or Sh-2-82 (219, 220, 224, 288, and 289) by needle inoculation. Fourteen BALB/c mice were inoculated by either Malonne (M50, M52, M54, M56, M58, M62, and M64) or Neuchâtel (N57, N59, N63, N65, N67, N69, and N71) ticks. Levels of antibody to IR6 and the C-terminal invariable domains were assessed using C6 and Ct ELISAs, respectively. The cutoff value (0.120) was based on the mean OD plus 3 standard deviations of 10 mouse prebleeds when the two peptides were separately used as an ELISA antigen.

Serodiagnostic value of the Ct peptide for both canine and human Lyme disease is limited.

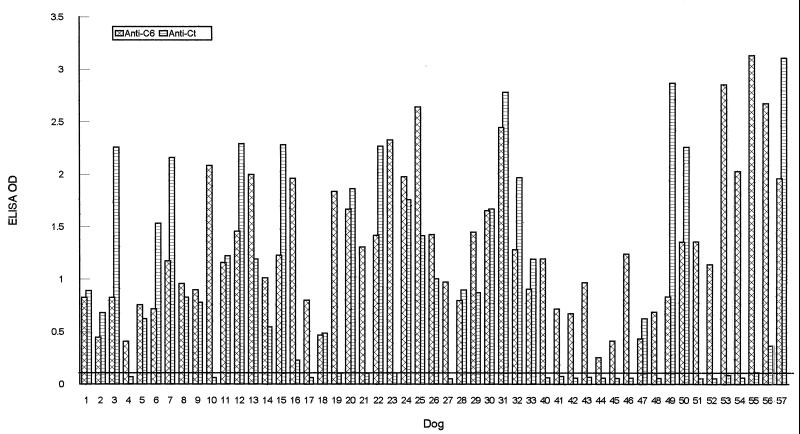

The diagnostic sensitivity of the Ct peptide ELISA was compared with that of the C6 ELISA in both dogs and humans. Twenty-six of the 33 serum samples from dogs that were infected with field-caught ticks (dogs 1 to 33) and only 5 of the 18 serum samples from clinically diagnosed dogs (samples 40 to 57) contained detectable anti-Ct antibody, while all of these 51 specimens were anti-C6 antibody positive (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the C6 ELISA performs better than the Ct ELISA as a diagnostic tool for dogs. The 33 serum specimens were collected at 7 to 8 weeks after dogs were experimentally infected with B. burgdorferi. In a previous study, the C6 ELISA yielded 100% sensitivity with sera from experimentally infected dogs as early as 4 weeks postinfection and 32% sensitivity (7 of 22) with sera collected at 3 weeks postinfection (21). To determine if the Ct ELISA is able to detect early infections, 30 dog serum samples that were collected at 2 to 3 weeks after experimental inoculation via ticks were analyzed using the Ct ELISA. No positive results were obtained (data not shown). Thus, the Ct ELISA did not improve diagnostic sensitivity with respect to the C6 ELISA in early canine Lyme disease.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of peptides C6 and Ct for detection of B. burgdorferi infection in dogs. Thirty-three dogs (dogs 1 to 33) were infected by tick inoculation. Eighteen sera (sera 40 to 57) were collected from dogs clinically diagnosed with Lyme disease. Antibody levels to IR6 and the C-terminal invariable domain were assessed using C6 and Ct ELISAs, respectively. The cutoff value (OD = 0.113) was defined as the mean OD plus 3 standard deviations of 10 serum samples from healthy dogs from an area where Lyme disease is not endemic, when the two peptides were separately used as ELISA antigens.

To compare the performance of these two peptides in the serodiagnosis of human Lyme disease, 85 serum samples collected from both American and European patients with early or late Lyme disease were analyzed. All of the serum specimens were positive by the C6 ELISA regardless of their geographic origins (Table 1). Although most of the American sera (57 of 64) were also positive by the Ct ELISA, only 12 of the 21 European specimens contained detectable anti-Ct antibody (Table 1). To determine if the Ct ELISA is able to detect an earlier infection, 32 sera that were collected from both American and European patients with early B. burgdorferi infection were analyzed by the Ct ELISA. All of the 32 samples were negative by the C6 ELISA. Two of the 24 American specimens were positive, while none of the 8 European specimens was positive by the Ct ELISA (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of peptides C6 and Ct for detection of B. burgdorferi infection in humansa

| Geographic origin | Disease (phase) | Serum no. | C6 ELISA OD | Ct ELISA OD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | Lyme disease (early) | CDC1 | P3.475 | P3.297 |

| CDC2 | P1.120 | P1.213 | ||

| CDC3 | P3.320 | N0.175 | ||

| CDC4 | P1.531 | P3.448 | ||

| CDC5 | P3.382 | P3.455 | ||

| CDC6 | P3.035 | P3.282 | ||

| CDC7 | P3.306 | P3.359 | ||

| CDC8 | P3.341 | P3.408 | ||

| CDC9 | P3.420 | P3.148 | ||

| CDC10 | P3.018 | P3.348 | ||

| CDC11 | P3.313 | N0.118 | ||

| CDC12 | P2.966 | P0.737 | ||

| CDC13 | P3.528 | P0.549 | ||

| CDC14 | P3.528 | P0.609 | ||

| CDC15 | P0.652 | P1.158 | ||

| CDC16 | P2.218 | N0.121 | ||

| CDC17 | P0.680 | P2.189 | ||

| CDC18 | P0.606 | P2.173 | ||

| CDC19 | P2.142 | P0.490 | ||

| CDC20 | P3.246 | P3.374 | ||

| Lyme disease (late) | T1 | P3.358 | P0.493 | |

| T2 | P3.288 | P3.398 | ||

| T3 | P3.165 | N0.196 | ||

| T4 | P3.800 | N.0190 | ||

| T5 | P3.367 | P3.371 | ||

| T6 | P3.428 | P3.030 | ||

| T7 | P3.406 | P3.239 | ||

| T8 | P3.175 | P3.398 | ||

| T9 | P3.335 | P0.988 | ||

| T10 | P3.488 | P3.260 | ||

| T11 | P3.337 | P3.285 | ||

| T12 | P3.443 | P3.382 | ||

| T13 | P3.365 | P3.237 | ||

| T14 | P3.095 | N0.217 | ||

| T15 | P0.565 | N0.297 | ||

| T16 | P3.394 | P3.312 | ||

| T17 | P3.384 | P3.394 | ||

| T18 | P3.454 | P3.267 | ||

| T19 | P3.272 | P3.477 | ||

| T20 | P3.404 | P3.491 | ||

| T21 | P3.417 | P0.505 | ||

| T22 | P3.406 | P3.334 | ||

| T23 | P3.425 | P3.393 | ||

| T24 | P3.444 | P3.374 | ||

| T25 | P3.306 | P3.597 | ||

| T26 | P3.442 | P3.433 | ||

| T27 | P3.197 | P2.852 | ||

| T28 | P1.460 | P3.321 | ||

| T29 | P3.349 | P3.457 | ||

| T30 | P3.505 | P3.450 | ||

| T31 | P3.292 | P2.607 | ||

| T32 | P3.136 | P0.818 | ||

| T33 | P3.504 | P2.260 | ||

| T34 | P3.419 | P3.307 | ||

| PTLDS | NIH1 | P3.477 | P2.681 | |

| NIH2 | P3.261 | P3.128 | ||

| NIH3 | P3.382 | P2.189 | ||

| NIH4 | P3.451 | P2.055 | ||

| NIH5 | P3.435 | P3.359 | ||

| NIH6 | P3.220 | P3.407 | ||

| NIH7 | P3.326 | P3.431 | ||

| NIH8 | P3.430 | P3.302 | ||

| NIH9 | P0.870 | P1.195 | ||

| NIH10 | P3.356 | P3.345 | ||

| Europe | Lyme disease (late) | A1 | P3.426 | N0.394 |

| A2 | P3.459 | P3.348 | ||

| A3 | P3.344 | P3.005 | ||

| A4 | P3.477 | P0.620 | ||

| A5 | P2.592 | N0.136 | ||

| A6 | P3.568 | P2.572 | ||

| A7 | P3.392 | N0.186 | ||

| A8 | P3.459 | P3.408 | ||

| A9 | P3.320 | P2.964 | ||

| A10 | P3.415 | P1.839 | ||

| A11 | P3.407 | N0.155 | ||

| A12 | P3.399 | P0.790 | ||

| A13 | P3.442 | P0.489 | ||

| I1 | P2.940 | P3.217 | ||

| I2 | P3.249 | N0.331 | ||

| I3 | P3.425 | N0.182 | ||

| I4 | P3.536 | N0.328 | ||

| I5 | P3.443 | N0.169 | ||

| I6 | P3.563 | P0.703 | ||

| I7 | P3.437 | P3.366 | ||

| I8 | P3.270 | N0.439 |

Three types of serum specimens (early and late Lyme disease and PTLDS) were from either U.S. or European patients. The antibody responses to IR6 and the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE were assessed by C6 and Ct ELISAs, respectively. The cutoff value (OD = 0.453) was defined as the mean OD plus 3 standard deviations of serum samples collected from 10 hospitalized patients in Louisiana, where Lyme disease is not endemic. P and N indicate positive and negative ELISA results, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Although VlsE is a variable antigen, its C-terminal invariable domain accounts for 15% of the entire molecule's length and remains unchanged during antigenic variation (32). Initial data indicated that the sequence conservation of this domain might be limited among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (12) and that the domain is antigenic in mice during B. burgdorferi infection (22). However, nothing was known about its antigenic conservation and its diagnostic value in Lyme disease serology.

To initially assess epitope conservation of the C-terminal invariable domain, whole-cell extracts of spirochetes belonging to 12 different strains that represent the three pathogenic genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato were reacted with mouse anti-Ct antiserum. This antiserum was generated by immunizing animals with the Ct-KLH conjugate; the Ct peptide reproduced the sequence of the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE expressed by the B31 B. burgdorferi strain (32). The anti-Ct antibody recognized only the VlsE antigen extracted from B31 spirochetes but not others, indicating that epitopes of the C-terminal invariable domain expressed by different strains are not the same. Antigenic conservation may be more stringent than sequence conservation in that a single amino acid substitution, a minimal sequence alteration, may destroy or diminish antigenicity of an epitope. Nonetheless, our results show that the C-terminal domain sequences of the VlsE of the 11 strains tested are not the same as that of B31. What our experiment cannot ascertain is to what extent the antigenic differences observed are reflected by sequence differences. The mouse anti-Ct antibody that we generated may be directed to a single epitope among the many that are likely present in the 51 amino acids of Ct. Thus, the absence of antigenicity could be brought about by relatively small sequence differences. Moreover, it is formally possible although unlikely that the 11 strains that we compared all have identical C-terminal VlsE sequences that differ from that of B31.

To determine if the C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant during a natural infection, sera from seven monkeys that were infected with B31 spirochetes via ticks were analyzed for an antibody response with the Ct ELISA. To further assess the antigenic conservation of this domain among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, anti-Ct antibody was quantified in serum specimens obtained from an additional 12 monkeys that were infected with spirochetes from strains other than B31. Only the B31-infected monkeys produced a significant level of antibody to Ct. These results suggested that the C-terminal invariable domain is immunodominant in monkeys but is not antigenically conserved among strains of B. burgdorferi during infection in this host species. The strong immunogenicity or immunodominance of the C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE during infection was further demonstrated by the high anti-Ct antibody levels quantified in six of six mice infected with B31 spirochetes.

The response was less uniform in mice than in monkeys. Some of the mice that were infected with spirochetes from strains other than B31 responded to Ct, albeit weakly in some cases, whereas others did not. We had already determined that the response of mice and dogs to VlsE differed from that of both humans and nonhuman primates (17, 21). For instance, IR2 and IR4 are antigenic in both mice and dogs but not in humans and monkeys. In addition, the two primate species respond to a single epitope within IR6, but mice may recognize multiple epitopes of this region (19). The 51-mer C-terminal invariable domain might contain several epitopes. Some of them might be more antigenically conserved than others among the strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. Monkeys probably only respond to less antigenically conserved regions, while mice can produce antibody to more conserved ones.

The C6 peptide ELISA has been shown to yield nearly 100% diagnostic sensitivity with serum specimens from humans (including American and European patients) with late Lyme disease (18, 20) and dogs with B. burgdorferi infection (21). In this study, the diagnostic performance of peptides C6 and Ct was compared with both human and dog serum samples. Although most of the dogs (26 of 33) that were experimentally infected by tick inoculation had a detectable anti-Ct response, only 5 of 18 specimens from clinically diagnosed animals were positive by the Ct ELISA. This difference may have resulted from a more disparate geographic distribution of the latter samples, as the ticks that were used to experimentally infect the dogs probably were collected in a more constrained region of the state of New York than that from which the clinically diagnosed samples originated. The spirochetes that were carried by the ticks may be genetically more related to strain B31 than are the spirochetes that infected the clinically diagnosed dogs. This interpretation also applies to the results obtained with human samples. A high proportion of the American patients with Lyme disease (57 of 64) had a detectable anti-Ct antibody response, while only 12 of the 21 European specimens were positive by the Ct ELISA. The American specimens were collected mainly from East Coast regions of the United States.

The C6 ELISA yielded sensitivities of 85% (117 of 138) for American patients and 83% (20 of 24) for European patients with early Lyme disease (including both acute and convalescent phases) (18, 20). In dogs, 7 of 22 (32%) B. burgdorferi infections were detected as early as 3 weeks and 100% (33 of 33) sensitivity was achieved after 4 weeks postinfection by the C6 ELISA (21). In this study, to assess if the Ct ELISA could improve sensitivity for detecting earlier B. burgdorferi infection, 22 canine serum specimens that were collected at 2 to 3 weeks postinfection and 32 human specimens that were collected from both American and European patients at either the acute or convalescent phase were analyzed by this assay. All these specimens were negative by the C6 ELISA. None of the dog or European human samples had a detectable anti-Ct antibody response, and only 2 of the 24 American specimens were positive by the Ct ELISA. Hence, overall, no significant sensitivity improvement was afforded. So far, the C6 peptide, which is based on the sequence of IR6 of the IP90 strain of B. garinii, is the best single antigen for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease in both the United States and Europe (18, 20). Moreover, in view of the limited conservation of the antigenicity of the C-terminal domain of VlsE, it is possible that the diagnostic performance of this molecule may hinge entirely upon that of IR6. It should be noted, however, that the antigenic contribution of the N-terminal domain has not been determined as yet.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lise Gern (University of Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland), Vincent Weynants (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium), Reinhard Straubinger (Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany), Richard Jacobson (Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.), Amy Grooters (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La.), Martin Schriefer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo.), Allen Steere (Tufts University, Boston, Mass.), Adriana Marques (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.), Elisabeth Aberer (University of Graz, Graz, Austria), and Marina Cinco (Università Trieste, Trieste, Italy) for providing serum samples.

This work was supported in part by grant RR00164 from NCRR, NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbet A F, McGuire T C. Crossreacting determinants in variant-specific surface antigens of African trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:1989–1993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.4.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barony G, Merrifield R B. The peptides: analysis, synthesis, and biology. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 3–285. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barstad P A, Coligan J E, Raum M G, Barbour A G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii, epitope mapping and partial sequence analysis of CNBr peptides. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1302–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borst P. Molecular genetics of antigenic variation. Immunol Today. 1991;12:A29–A33. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borst P, Cross G A M. Molecular basis for trypanosome antigenic variation. Cell. 1982;29:291–303. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross G A M. Crossreacting determinants in the C-terminal region of trypanosome variant surface antigens. Nature. 1979;277:310–312. doi: 10.1038/277310a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forest K T, Bernstein S L, Getzoff E D, So M, Tribbick G, Geysen H M, Deal C D, Tainer J A. Assembly and antigenicity of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilus mapped with antibodies. Infect Immun. 1996;64:644–652. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.644-652.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French D M, McElwain T F, McGuire T C, Palmer G H. Expression of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 variants during persistent cyclic rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1200–1207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1200-1207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French D M, Brown W C, Palmer G H. Emergence of Anaplasma marginale antigenic variants during persistent rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5834–5840. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5834-5840.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gern L, Schaible U E, Simon M M. Mode of inoculation of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi influences infection and immune responses in inbred strains of mice. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:971–975. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature. 1985;315:156–168. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer R, Hardham J M, Wormser G P, Schwartz I, Norris S J. Conservation and heterogeneity of vlsE among human and tick isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1714–1718. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1714-1718.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahl O, Gern L, Gray J S, Guy E C, Jongejan F, Kirstein F, Kurtenbach K, Rijpkema S G, Stanek G. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks: immunofluorescence assay versus polymerase chain reaction. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1998;287:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawabata H, Myouga F, Inagaki Y, Murai N, Watanabe H. Genetic and immunological analyses of Vls (VMP-like sequences) of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:155–166. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrenz B M, Hardham J M, Owens R T, Nowakowski J, Steere A C, Wormser G P, Norris S J. Human antibody responses to VlsE antigenic variable protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3997–4004. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3997-4004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang F T, Alvarez A L, Gu Y, Nowling J M, Ramamoorthy R, Philipp M T. An immunodominant conserved region within the variable domain of VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 1999;163:5566–5573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang F T, Philipp M T. Analysis of antibody response to invariable regions of VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6702–6706. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6702-6706.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang F T, Steere A C, Marques A R, Johnson B J B, Miller J N, Philipp M T. Sensitive and specific serodiagnosis of Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a peptide based on an immunodominant conserved region of Borrelia burgdorferi VlsE. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3990–3996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3990-3996.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang F T, Philipp M T. Epitope mapping of the immunodominant invariable region of VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2349–2352. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2349-2352.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang F T, Aberer E, Cinco M, Gern L, Hu C M, Lobet Y N, Ruscio M, Voet P E, Jr, Weynants V E, Philipp M T. Antigenic conservation of an immunodominant invariable region of the VlsE lipoprotein among European pathogenic genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi SL. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1455–1462. doi: 10.1086/315862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang F T, Jacobson R H, Straubinger R K, Grooters A, Philipp M T. Characterization of a Borrelia burgdorferi VlsE invariable region useful for canine Lyme disease serodiagnosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4160–4166. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4160-4166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang F T, Jacobs M B, Philipp M T. C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE may not serve as target for protective immune response against Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1337-1343.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier J T, Simon M I, Barbour A G. Antigenic variation is associated with DNA rearrangements in a relapsing fever Borrelia. Cell. 1985;41:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer G H, Brown W C, Rurangirwa F R. Antigenic variation in the persistence and transmission of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philipp T M, Aydintug M K, Bohm R P, Jr, Cogswell F B, Dennis V A, Lanners H N, Lowrie R C, Jr, Roberts E D, Conway M D, Karaçorlu M, Peyman G A, Gubler D J, Johnson B J B, Piesman J, Gu Y. Early and early disseminated phases of Lyme disease in the rhesus monkey: a model for infection in humans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3047–3059. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3047-3059.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothbard J B, Fernandez R, Schoolnik G K. Strain-specific and common epitopes of gonococcal pili. J Exp Med. 1984;160:208–221. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straubinger R K, Straubinger A F, Summers B A, Jacobson R H. Status of Borrelia burgdorferi infection after antibiotic treatment and the effects of corticosteroids: an experimental study. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1069–1081. doi: 10.1086/315340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Ploeg L H T, Gottesdiener K, Lee M G S. Antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Trends Genet. 1992;8:452–457. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J R, Norris S J. Genetic variation of the Borrelia burgdorferi gene vlsE involves cassette-specific, segmental gene conversion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3698–3704. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3698-3704.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J R, Norris S J. Kinetics and in vivo induction of genetic variation of vlsE in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3689–3697. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3689-3697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]