Abstract

In the present review, we synthesize information on the mechanisms of chronic copper (Cu) toxicity using an adverse outcome pathway framework and identify three primary pathways for chronic Cu toxicity: disruption of sodium homeostasis, effects on bioenergetics, and oxidative stress. Unlike acute Cu toxicity, disruption of sodium homeostasis is not a driving mechanism of chronic toxicity, but compensatory responses in this pathway contribute to effects on organism bioenergetics. Effects on bioenergetics clearly contribute to chronic Cu toxicity with impacts at multiple lower levels of biological organization. However, quantitatively translating these impacts into effects on apical endpoints such as growth, amphibian metamorphosis, and reproduction remains elusive and requires further study. Copper‐induced oxidative stress occurs in most tissues of aquatic vertebrates and is clearly a significant driver of chronic Cu toxicity. Although antioxidant responses and capacities differ among tissues, there is no clear indication that specific tissues are more sensitive than others to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress leads to increased apoptosis and cellular damage in multiple tissues, including some that contribute to bioenergetic effects. This also includes oxidative damage to tissues involved in neuroendocrine axes and this damage likely alters the normal function of these tissues. Importantly, Cu‐induced changes in hormone concentrations and gene expression in endocrine‐mediated pathways such as reproductive steroidogenesis and amphibian metamorphosis are likely the result of oxidative stress‐induced tissue damage and not endocrine disruption. Overall, we conclude that oxidative stress is likely the primary driver of chronic Cu toxicity in aquatic vertebrates, with bioenergetic effects and compensatory response to disruption of sodium homeostasis contributing to some degree to observed effects on apical endpoints. Environ Toxicol Chem 2022;41:2911–2927. © 2022 The Authors. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of SETAC.

Keywords: Adverse outcome pathway, copper, endocrine disruption, mode of action, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Copper (Cu) is a relatively abundant trace element in the earth's crust and naturally occurs in freshwaters in the range of 0.2–10 μg L−1, although concentrations as high as 30 μg L−1 can occur in highly mineralized areas (US Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA], 2007). It is widely used in modern society to support infrastructure and a wide variety of activities. Key uses of Cu and Cu alloys include use in electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, sustainable energy sources such as wind and solar, electric networks and power distribution, heating and cooling of buildings, and water distribution (Patterson et al., 1998; USEPA, 2007). In the environment, Cu is an essential element for all forms of life, but excessive exposure may trigger toxic effects (Grosell, 2012).

Copper is generally among the most studied environmental toxicants (Posthuma et al., 2019). The mechanism of action of Cu in short‐term (acute) exposures of fish and invertebrates is well characterized, with the main target being disruption of ion regulation, particularly the disturbance of Na homeostasis (Grosell, 2012). The same mechanism may also play a role in long‐term exposures but is unlikely to be the primary cause of chronic toxicity due to compensatory responses that generally allow for the maintenance of Na homeostasis (McGeer et al., 2000).

Handy (2003) reviewed information available at that time and hypothesized that the adverse effects of chronic exposure to waterborne Cu in fish may be triggered by general stress responses. Copper triggers cortisol release (De Boeck et al., 2001; Flik et al., 2002; Monteiro et al., 2005) and the sustained activation of this response in chronic Cu exposure may lead to multiple systemic effects. Since that publication, a significant body of literature has been generated that allows for a more detailed evaluation of the relative importance of various mechanisms of Cu toxicity resulting from chronic exposure. This new information, and the available knowledge on chronic toxicity of Cu has to date, not been synthesized into a conceptual framework.

Recent regulatory trends emphasize the importance of gathering and synthesizing knowledge about the mode of action of environmental toxicants. This is particularly evident in the European Union, where assessments of the endocrine disrupting properties of biocides and plant protection products have been mandatory since 2018 and dedicated guidance is available (European Chemicals Agency [ECHA], European Food Safety Authority [EFSA], 2018). Substances which have endocrine‐disrupting properties are normally not approved for widespread use. The European Union Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability shows that, over the coming years, regulation of endocrine disruptors will increase, and regulation can be expected for other endpoints with a strong mode‐of‐action component, such as immunotoxicants and neurotoxicants (European Commission, 2020). These new regulations are expected to be adopted in some form globally. The European Union Commission, for example, will propose a new hazard class for endocrine disruptors in the United Nations Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (UN GHS). In view of these regulatory trends, there is a clear and urgent need to better integrate the available knowledge on the modes of action of toxicants, particularly with respect to evaluating whether a chemical should be classified as an endocrine disruptor.

Regulatory definitions of endocrine disruptors are often based on the definition by the World Health Organization (WHO, United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2013) and imply that endocrine disruptors cause adverse effects on organisms through direct action on a hormone–receptor complex or direct action on specific proteins that control some aspect of hormone delivery. In contrast, adverse effects that are nonspecific secondary consequences of other toxic effects, which we define as endocrine modulation, shall not be considered for the identification of the substance as an endocrine disruptor (ECHA, EFSA, 2018). However, in reality, environmental toxicants can exert adverse effects through multiple pathways in parallel, and identifying cause and effect is not always straightforward. This challenge is particularly relevant for Cu, which is an essential nutrient, is homeostatically regulated, and has a physiological role in normal neuroendocrine functions in vertebrates (Linder, 1991), complicating elucidation of cause and effect. Copper therefore represents a challenging case study to integrate the wealth of available mechanistic information into a conceptual framework such as an adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework. Our objective was to synthesize and update our understanding of Cu mechanisms of action within an AOP framework, including any potential role in endocrine disruption, and to identify existing data gaps that should be prioritized for future research.

AOP FRAMEWORK

An AOP is a conceptual model that characterizes the linkage between a stressor‐induced molecular initiating event (MIE) and consequent key events (KEs) through increasingly higher levels of biological organization, ultimately connecting the MIE through a series of key event relationships (KERs) to adverse outcomes (AOs) at the whole organism and population level (Ankley et al., 2010). Adverse outcome pathways are not generally stressor‐specific, but rather describe a physiological cascade of events triggered by a particular MIE, which may be induced by multiple stressors. Adverse outcome pathways provide a relatively standardized model framework for integrating a wide range of information on how stressors elicit responses in an organism at various levels of biological organization. In addition, AOPs are a useful tool for identifying important areas of uncertainty in our understanding for how a stressor may cause effects on organisms (Brix et al., 2017; Fay et al., 2017).

In the present analysis we use the AOP framework as a tool to evaluate how known mechanisms of action for Cu in chronic exposures to aquatic vertebrates (fish and amphibians) lead to AOs at higher levels of biological organization. An additional objective was to investigate if any KEs are associated with endocrine disruption or modulation. To accomplish this, we first identified known mechanisms of action for waterborne Cu exposure based on a review of the primary literature, literature reviews, and book chapters. We did not consider dietary Cu exposure in our evaluation because toxicity via this exposure pathway typically does not occur in vertebrates at environmentally realistic concentrations (Clearwater et al., 2002; DeForest & Meyer, 2015; Meyer et al., 2002). Furthermore, we did not explicitly consider marine fish in this assessment because there are very few studies on the mechanisms of chronic Cu toxicity for marine fish. However, in general, we expect marine fish to have similar responses to Cu, as described in this assessment, because most aspects of their physiology are similar or identical to those of freshwater fish. The obvious exception to this generalization is with respect to osmo‐ and ionoregulation. Similar to freshwater fish, the acute mechanisms of action for Cu to marine fish are relatively well described and are related to disruption of water and ion balance, with both the gill and intestine being target tissues (Grosell, 2012; Grosell et al., 2007).

Six general mechanisms of action for Cu were identified: disruption of ion regulation, oxidative stress, effects on liver metabolism, effects on bioenergetics leading to impaired growth and reproduction, effects on sensory systems (olfactory and lateral line), and effects on amphibian metamorphosis.

Using the identified mechanisms of action as anchors, we developed AOP frameworks delineating known and putative linkages to KEs and ultimately MIEs at lower levels of biological organization, as well as KEs and AOs at high levels of biological organization. We put particular emphasis on identifying and discussing the involvement of the endocrine system in these pathways with the objective of discriminating between endocrine modulation and endocrine disruption in response to chronic Cu exposure.

Differences in the complexity of each mechanism of action necessitated developing the AOP frameworks from different perspectives (Villeneuve et al., 2014). The AOP for disruption of ion regulation takes a bottom‐up approach beginning with MIEs. Oxidative stress resulting from excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) was identified as an MIE for effects on multiple systems and is presented as multiple components of the same AOP. Conversely, for bioenergetic effects, we used a top‐down approach to develop and describe how multiple AOPs converge and interact to affect whole‐organism phenotypes.

The remainder of the present study is organized around these three AOP frameworks, first presenting an AOP for disruption of ion regulation, then an AOP for oxidative stress that has multiple pathways related to mechanisms of action commonly considered in the literature for Cu, and finally an AOP framework for Cu effects on organism bioenergetics. Overlaying these AOPs, we highlight involvement of the endocrine system, identifying potential KEs involving endocrine modulation and disruption resulting from chronic Cu exposure.

INHIBITION OF TRANSPORTERS AND ENZYMES INVOLVED IN Na+ REGULATION

Inhibition of transporters and enzymes involved in sodium ion (Na+) uptake in freshwater is one of several MIEs for Cu. Although the resulting AOP has been primarily studied in acute (lethal) exposures at relatively high Cu concentrations, effects in sublethal exposures have also been documented (De Boeck et al., 2007; Kamunde et al., 2005; McGeer et al., 2000). In freshwater aquatic systems, dissolved Cu can be present as the Cu2+ ion, complexed with inorganic anions (e.g., CuCl2, CuSO4) or complexed with organic ligands in the system such as fulvic and humic acids (Campbell, 1995). Generally, the Cu2+ ion is considered the primary aqueous species that is bioavailable. The effects of water chemistry on the fraction of dissolved Cu present as Cu2+ and competitive reactions between binding sites at the respiratory surfaces of aquatic organisms and inorganic and organic ligands form the basis of the biotic ligand model (Di Toro et al., 2001).

In aquatic organisms, Cu uptake generally occurs across ionocytes localized in the respiratory epithelia (e.g., the gill). In fish, uptake occurs via both Na‐sensitive and Na‐insensitive pathways (Grosell & Wood, 2002) and likely occurs via analogous pathways in amphibians, but this has not been studied in detail. The Na‐sensitive pathway is most likely an Na channel whereas the Na‐insensitive pathway is most likely divalent metal transporter 1 and/or copper transporter 1 (Grosell & Wood, 2002). There is some evidence that Cu directly affects Na+ uptake at the apical membrane, with studies on rainbow trout showing non‐monotonic effects on Na transport affinity and capacity in the presence of increasing Cu concentrations (Grosell & Wood, 2002). These studies have also demonstrated that Cu rapidly (2 h) inhibits Na+ uptake, further supporting an immediate effect at the apical membrane of the ionocyte. However, Cu uptake via the Na‐sensitive pathway is inhibited by very low Na concentrations (median inhibition concentration of 104 μM Na+) such that this uptake pathway will have only a minor role in inhibiting Na+ uptake in most natural waters. Consequently, Cu uptake is thought to primarily occur via the Na‐insensitive pathway under most conditions.

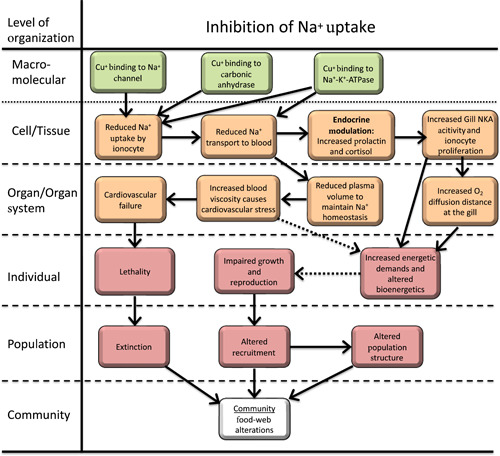

Once Cu enters the gill ionocyte, it can inhibit both carbonic anhydrase and Na+‐K+‐ATPase (NKA) activity (Lauren & McDonald, 1987a; Li et al., 1998; Zimmer et al., 2012; Figure 1). The combination of these effects, which are concentration‐dependent and vary across species, leads to inhibition of Na+ uptake and a reduction in circulating plasma Na+ (Lauren & McDonald, 1985; McGeer et al., 2002). In fish, reduced Na+ uptake triggers an endocrine response with an increase in cortisol and prolactin production (Mancera & McCormick, 2007). Cortisol may stimulate NKA activity (although there is more evidence for this in marine fish than freshwater fish) whereas prolactin reduces gill permeability and triggers ionocyte proliferation. Reduction of plasma Na+ also triggers a diffusive reduction in blood volume, increasing blood viscosity and consequently reducing cardiovascular circulation efficiency primarily by eliciting changes in cardiac stroke volume (Shiels et al., 2006). At a minimum, this may impart bioenergetic costs, while greater reductions in blood volume may lead to reductions in gas (O2, CO2) exchange efficiency throughout the body. If plasma volume is reduced too much (~30%), cardiovascular failure and death result.

Figure 1.

Adverse outcome pathway for effects of Cu on Na+ homeostasis in freshwater vertebrates. Solid lines indicate relationships that are well supported in the literature. Dashed lines indicate hypothesized relationships or relationships supported by limited or conflicting data.

Although the etiology of Cu effects on Na+ homeostasis is relatively well understood, if Cu concentrations are not sufficiently high to cause death, compensatory mechanisms allow a complete or near complete restoration of Na+ homeostasis (Lauren & McDonald, 1987b; McGeer et al., 2000). Specifically, increases in gill NKA activity (McGeer et al., 2000), proliferation of ionocytes (Pelgrom et al., 1995), and reductions in Na+ diffusive loss (Lauren & McDonald, 1987b) occur over a period of several weeks. It is possible that persistent small reductions in plasma Na+ and compensatory reductions in blood volume may impart long‐term energy deficits via increased work by the heart. Similarly, ionocyte proliferation correspondingly reduces the lamellar surface area covered by pavement cells and increases net O2 diffusion distance (Perry, 1998; Wood & Eom, 2021). Although this osmorespiratory compromise could lead to alterations in whole‐animal bioenergetics, studies indicate routine oxygen consumption in Cu‐exposed fish is not impacted or even increases (De Boeck et al., 2006) under normoxic conditions. However, studies have also shown that under hypoxic conditions Pcrit, the lowest O2 concentration in water at which standard metabolic rate can be maintained, increases in a concentration‐dependent manner consistent with limitations in O2 diffusion in common carp (De Boeck et al., 1995). In contrast to trout, hypoxia and anoxia tolerant species such as common and gibel carp seem to exploit the osmorespiratory compromise even further and develop an interlamellar cell mass (De Boeck et al., 2007). This gill remodeling reduces ion losses, but also explains the increased Pcrit at reduced oxygen levels. Finally, compensatory increases in NKA activity (McGeer et al., 2000) clearly impart a long‐term increase in energy demand also affecting the whole‐animal energy budget.

In conclusion, numerous studies support that Cu directly competitively and noncompetitively inhibits transport proteins and enzymes involved in Na uptake, leading to a physiological cascade. At low Cu concentrations, compensatory responses are elicited that may negatively impact organism bioenergetics and ultimately affect apical endpoints like growth and reproduction. At higher Cu concentrations, cardiovascular failure and death may occur. As part of this physiological cascade, Cu does elicit compensatory endocrine responses aimed at maintaining ion homeostasis. However, these responses are consistent with those typically observed when organisms experience the ionoregulatory challenges associated with being exposed waters with low ion content. Consequently, with respect to disruption of ion regulation, Cu modulates but does not disrupt normal endocrine function.

OXIDATIVE STRESS

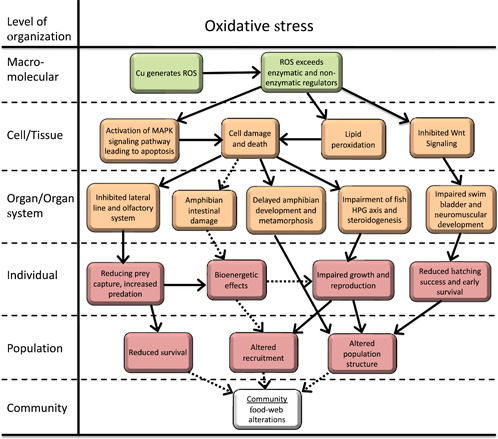

Induction of ROS is another major MIE for Cu‐induced effects and has been postulated to trigger multiple KEs across a broad range of physiological systems via the generation of oxidative stress. To further characterize this pathway, the overall AOP for Cu‐induced oxidative stress was organized around five KEs that are commonly identified as “mechanisms of action” for Cu. Details for each of these components of the overall oxidative stress AOP was then evaluated in greater detail along with potential interactions between components (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adverse outcome pathway for the effects of Cu‐induced oxidative stress on freshwater vertebrates. Solid lines indicate relationships that are well supported in the literature. Dashed lines indicate hypothesized relationships or relationships supported by limited or conflicting data. ROS = reactive oxygen species; HPG = hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal.

The generation of excessive ROS in the form of superoxide and hydroxide radicals is generally driven by the Haber–Weiss and/or Fenton reactions (Regoli, 2012):

Reactive oxygen species generation is regulated by both enzymatic (catalase and super‐oxide dismutase) and nonenzymatic reactions (glutathione) that reduce superoxide anions back to H2O2 and ultimately O2. However, excess Cu and consequently ROS generation at sufficiently high concentrations can overwhelm these regulatory processes resulting in lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and interference with cell cycle regulatory pathways, leading to increased induction of apoptosis (Di Giulio et al., 1989). Reactive oxygen species‐induced apoptosis involves regulatory pathways associated with multiple mitogen‐activated protein kinases that interact in complex positive and negative feedback loops. The specifics of these interactions are dependent on a variety of factors, including the concentration of ROS, the tissue, whether a stressor (e.g., Cu) directly interacts with these pathways in addition to generating ROS, and the general oxidative status of the tissue or organism (Yue & Lopez, 2020). Consequently, the specific KEs and KERs that lead from excess ROS (i.e., oxidative stress) to apoptosis are not readily generalized.

Detailed AOPs linking oxidative stress to apoptosis in each physiological system impacted by Cu in aquatic organisms is not currently possible because it has not been studied in sufficient detail. However, to varying degrees, oxidative stress and increased rates of apoptosis have been characterized in all of the following physiological systems in response to Cu exposure. Consequently, this MIE (generation of excess ROS leading to oxidative stress) is hypothesized to be an important, perhaps primary, factor in AOPs associated with these physiological systems.

Effects on fish sensory systems

The effects of Cu on both olfaction and the lateral line system in fish are relatively well studied. Multiple studies have been conducted on fish olfaction and the ability to detect an odorant in the presence and absence of Cu. Observed effect concentrations range from 3.6 up to approximately 25 μg L−1 Cu depending on the species, odorant, and statistical endpoint (Baldwin et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 1999; McIntyre et al., 2008; Sandahl et al., 2004). Effects on the lateral line system of fish have been observed at somewhat higher Cu concentrations (25–50 μg L−1; Linbo et al., 2006; 2009).

A specific MIE for Cu effects on the olfactory system has not been identified but it is postulated to be triggered by Cu‐induced oxidative stress and subsequent increased apoptosis in the cilia and microvilli of the olfactory rosette (Figure 2). In the olfactory rosette of fish, either cilia or microvilli are attached to the dendritic bulb and are the location of receptor proteins for odorants (Schild & Restrepo, 1998). The cilia and microvilli are embedded in and project out of a mucus layer into the external environment.

There are two physiological pathways involved in odorant stimulation. Both pathways involve an odor‐specific receptor located in the cilia or microvilli of the olfactory rosette neuron. The receptor is coupled to a G protein which, when triggered by the odor, undergoes a conformational change, releasing the α subunit. On release, the α subunit interacts with either adenylate cyclase (cAMP pathway) or phospholipase C (IP3 pathway) both of which, through several steps, ultimately lead to signal transduction. Studies in catfish, goldfish, and salmonids indicate that the cAMP olfaction pathway is strictly associated with receptors located on cilia. These receptors are sensitive to amino acids and bile salts. In contrast, the IP3 pathway is associated with microvilli and is sensitive to amino acids and nucleotides (Hansen et al., 2003; 2004).

The signaling pathways for olfactory sensory neurons theoretically provide multiple potential mechanisms by which Cu may interfere with fish olfaction. However, consideration of available data allows for a reasonable hypothesis regarding the most likely target of Cu toxicity. First, keeping in mind that amino acid odorants stimulate both signaling pathways, inhibited detection of amino acids by Cu is suggestive that the mechanism of action occurs prior to differentiation in these two pathways (i.e., at either the microvilli or cilia). Baldwin et al. (2003) have shown a similar degree of inhibition between several amino acid and bile salt odorants. Although these odorants all trigger the cAMP pathway, they have different binding sites on the cilia (Cagan & Zeiger, 1978), suggesting that Cu is not targeting specific receptor binding sites.

Although by no means conclusive, these data suggest that the target of action is the cilia and microvilli. Hansen et al. (1999) showed severe damage to cilia and microvilli of Oncorhynchus mykiss and Oncorhynchus tshawytscha exposed to 50 μg L−1 Cu for 4 h. Similarly, Julliard et al. (1996) observed apoptosis of olfactory rosette neurons exposed to 20 μg L−1 Cu for 15 days, with a significant increase in apoptotic cells after only 1 day of exposure. The mechanism underling rapid loss of cilia and microvilli exposed to Cu has not been determined. However, ROS has been linked to enhanced and rapid apoptosis of olfactory sensory neurons in fish subjected to prolonged exposure to natural odorants, suggesting that this is a potential mechanism for the rapid effects observed in Cu‐exposed fish (Klimenkov et al., 2020).

Analogous to the olfactory system, the neuromasts of the lateral line system contain a rosette of hair cells that projects into the water column and is sensitive to changes in water pressure (Linbo et al., 2006). Also similar to the olfactory rosette, concentration‐dependent loss of cilia from neuromasts of the lateral line system in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has been observed at Cu concentrations ≥20 μg L−1 with degeneration of cilia beginning within 1 h of exposure (Linbo et al., 2006). Subsequent studies with zebrafish larvae exposed to 64 μg L−1 Cu for 1–2 h also resulted in the rapid apoptosis of hair cells (Olivari et al., 2008). Under this same experimental regime, the generation of ROS in neuromast hair cells was visualized using immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, when larvae were first incubated in antioxidants (glutathione, I‐N‐acetyl cysteine, N,N’‐dimethylthiourea), then rinsed and exposed to Cu, no ROS was observed and hair cells were not lost, providing relatively strong support for ROS being an important factor in the loss of hair cells from lateral line neuromasts.

Overall, there is moderately strong linkage indicating that ROS initiates increased apoptosis of hair cells in neuromasts of the lateral line system and weak inference that ROS also causes similar effects in the cilia and microvilli of olfactory sensory neurons (Figure 2). Regardless of the MIE, the loss of these structures and subsequent reduction or loss of function in these sensory systems on exposure to Cu is well documented. Loss of sensory system function has been shown to have significant impacts on organism behavior, including reduced ability to locate food (Kuz'mina, 2011) and reduced response to alarm cues from conspecifics, which could lead to increased predation (Dew et al., 2014; McIntyre et al., 2012; Pilehvar et al., 2020).

There are no studies indicating either endocrine disruption or modulation within this component of the overall AOP for oxidative stress.

Effects on amphibian intestine

Active drinking in freshwater fish is very limited and most water intake is a result of incidental ingestion during feeding (Baldisserotto et al., 2007). In contrast, larval amphibians are known to actively drink water, providing a mechanism for Cu exposure to the gastrointestinal tract. Although not studied extensively, two studies have observed intestinal lesions, including disordered enterocytes, and abnormal villi and vacuoles in tadpoles exposed to Cu at concentrations (32–64 µg L−1 Cu) that elicit reduced tadpole growth (Yang et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021). These types of histological effects may be the result of oxidative stress from Cu exposure, although direct measurements of the oxidative status of the intestine were not made (Figure 2). Regardless of the MIE, intestinal function plays an active role in bioenergetics and potentially immunological processes (Bletz et al., 2016), and potential alteration by Cu exposure may reduce the ability of the larval phase amphibian to thrive and of the metamorphosing amphibian to properly transition from the larval phase to the terrestrial life phase.

Effects on early development and metamorphosis in amphibians

Amphibian larval development is divided into four phases, with three specifically addressing the status of metamorphic processes, early embryo‐larval development, premetamorphosis, pro‐metamorphosis, and metamorphic climax. Developmental progression is most commonly identified by developmental Gosner staging (Gosner, 1960) for ranids (true frogs) and in the commonly used laboratory pipid frogs Xenopus laevis and Silurana tropicalis by Nieuwkoop & Faber (NF) staging (Nieuwkoop & Faber, 1994). Both can be cross‐referenced and both will be used in this discussion based on the species referenced with the cross‐reference provided.

During early embryo‐larval development (NF stages 1–46), rapid development and primary organogenesis occur and larvae are prefeeding because nutrition is provided by the yolk. Premetamorphosis (NF stages 47–53) is characterized by larval growth and nonthyroidal development. During this phase, the thyroid continues to develop, but is not physiologically functional because thyroid hormone (TH) is not produced. During prometamorphosis (NF stages 54–59) the thyroid is responsive and produces TH which, along with autonomously expressed thyroid hormone receptors, progresses the metamorphic processes to support TH‐induced morphogenesis. The final stage, metamorphic climax, begins at NF stage 60 and is characterized by a large surge in TH peaking at approximately NF stage 61. The surge in TH initiates major tissue remodeling and tail resorption, and decreases to preclimax levels by NF stage 62.

The effects of Cu exposure on embryo‐larval and premetamorphic development have been investigated in several species, including Rana (Lithobates) pipiens (Chen et al., 2007), Gastrophryne carolinensis (Flynn et al., 2015), L. sylvatica (Peles, 2013), Anaxyrus terrestris (Rumrill et al., 2016), and X. laevis (Fort, Rogers, et al., 2000; Fort et al., 2004). Chen et al. (2007) exposed newly hatched northern leopard frogs to 5–100 μg L−1 Cu (as CuSO4) for 154 days. An increased incidence of malformation (gills, mouth) and edema was observed early in exposure (10 days) in the 100 μg L−1 Cu treatment. Exposure to 100 μg L−1 Cu decreased survival, impaired swimming behavior, and slowed time to metamorphosis. Flynn et al. (2015) found that the sensitivity of embryo‐larval eastern narrowmouth toads to chronic Cu exposure ranging from 10 to >50 μg L−1 was dependent on parental exposure. Parental exposure reduced embryo‐larval lethality, but increased the larval phase in progeny compared with progeny from parents not exposed to Cu. However, developmental delay in the transition from embryo to free‐swimming larva was noted in embryonic exposure to >50 μg L−1 Cu regardless of parental exposure. Peles (2013) found that wood frog larvae exposure to Cu (1–200 μg L−1 Cu, pH 4.7) through the completion of metamorphosis (43–102 days) reduced body mass early in exposure (50–200 μg L−1 Cu) and markedly increased the time to hindlimb, forelimb, and tail resorption stages by 3–4 weeks. Exposure to 10 μg L−1 Cu increased the time to the forelimb and tail resorption stages. Rumrill et al. (2016) found that exposure of early larval southern toads to 30 μg L−1 Cu decreased the time to emergence. Fort, Stover, et al. (2000) investigated the nutritional essentiality of copper, demonstrating that parental X. laevis maintained on a Cu‐deficient diet produced embryos with reduced viability, including increased occurrence of early embryo‐larval craniofacial and eye deformities. Interestingly, the same response was observed with a high‐Cu diet, but not with a standard diet, resulting in a classical U‐shaped dose–response curve indicative of the nutritional essentiality of Cu in early development. Early developmental abnormalities resulting from Cu exposure, including the eye, craniofacial region, and gut, were also noted by Fort et al. (2004) in both X. laevis and S. tropicalis. Collectively, each of these studies emphasized that Cu targeted premetamorphic development and, depending on the study, early embryo‐larval development prior to the onset of more advanced metamorphic processes. Therefore, the apparent effects of Cu exposure on metamorphosis may actually be the result of earlier effects resulting in developmental delay and growth retardation.

Amphibian metamorphosis is a complex, conserved process of development, remodeling, and loss of tissues once important to the larval life phase, but necessary for advancement to an adult life stage. Generally, metamorphosis is controlled by the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis (Buchholz et al., 2006; Denver et al., 2002; Denver, 2009, 2013; Fort et al., 2007; Shi, 2000; Trudeau et al., 2020). More specifically, the hypothalamic factors thyroid‐releasing hormone (TRH) and corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF); pituitary hormones thyroid‐stimulating hormone (TSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone, and ultimately two specific hormones which direct metamorphosis at the tissue level, TH and corticosterone, provide regulation of the HPT axis and control metamorphic processes. Paradoxically, in anurans TRH is associated with release of prolactin and growth hormone from the pituitary which provides inhibitory control of some metamorphic processes such as tail resorption and is interconnected with larval growth (Buckbinder & Brown, 1993; Hayes, 1997; Shi, 2000; Tata, 1997). Alternatively, CRF is associated with TSH release from the pituitary. In anurans, negative feedback by the HPT axis does not suppress TSH levels through elevated TH levels during metamorphosis (Buckbinder & Brown, 1993). Following metamorphic climax leading up to the completion of metamorphosis, TSH and TH decrease leads to quiescent, less hypertrophic thyroid follicles (Grim et al., 2009). Control of metamorphosis is also afforded by peripheral TH transport (Shi, 2000), autonomous expression of thyroid hormone receptors, and metabolic recycling of TH in the liver by deiodinases (Huang et al., 1999; Manzon & Denver, 2004).

Current understanding of the biochemical basis for events associated with metamorphosis at the cellular level, such as remodeling of the intestine for terrestrial life (Damjanovski et al., 2000) and resorption of the tail (Inoue et al., 2004), suggest that two primary and mechanistically linked processes are involved: changes in tissue‐specific oxidative stress and induction of apoptosis (Allen, 1991; Buchholz, 2017; Menon & Rozman, 2007). Oxidative stress in the intestine and tail tissue is the result of depleted catalase and reduced glutathione coupled with increased lipid peroxidation, which is consistent with decreased superoxide dismutase and catalase expression (Menon & Rozman, 2007). An increase in the antioxidant ascorbic acid was found in intestinal and tail tissue during metamorphic climax and hypothesized to control collagen formation in the intestine and resorption of the tail. Thus, a key aspect of the normal metamorphic process in amphibian tissue is a progression toward an oxidative state.

As with the early developmental effects of Cu exposure, the effects of Cu exposure on metamorphosis have also been studied in several species, including L. sphenocephala (Lance et al., 2012), Bufo gargarizans (Chai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016), and X. laevis (Fort, Rogers, et al., 2000). Experiments involving Cu exposure from pre‐metamorphic through metamorphic climax (NF stage 47–62) on the same species found decreased metamorphic success and increased length of both the hind limb and tail (Chai et al., 2017). These investigators observed down‐regulation of hsp, sod, and phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (phgpx) suggesting potential Cu‐induced oxidative stress during metamorphosis. However, confounding results were observed by this same research group in an earlier experiment with Cu using the same developmental exposure window despite similar effects on apical endpoints (reduced growth, delayed metamorphosis; Wang et al., 2016). More specifically, Wang et al. (2016) observed up‐regulated expression of deiodinase III (Dio3; T4 to rT3 and T3 to T2), whereas Chai et al. (2017) observed down‐regulation of both deiodinase II (Dio2; T4 to T3) and Dio3 in response to Cu exposure. Both studies observed down‐regulation of trα and trβ expression in response to Cu. Overall, these two studies demonstrated that Cu exposure delayed metamorphosis and decreased metamorphic completion at concentrations ranging from 6 to 64 µg L−1 Cu, but more precise conclusions cannot be drawn due to reliability issues and conflicting evidence.

In contrast to the above studies, exposure of X. laevis to 800 μg L−1 Cu during metamorphic climax had no effect on tail resorption (Fort, Rogers, et al., 2000). The X. laevis study only included the most advanced stage of metamorphosis, whereas the previously discussed studies (Chai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) included Cu exposure over the course of larval development into the metamorphic stages. These disparate findings suggest that the late metamorphic stages may be relatively insensitive to Cu exposure and underscore the potential importance of generalized earlier systemic toxicity in eliciting responses on late metamorphic processes.

Given the importance of oxidative stress in amphibian metamorphosis (Allen, 1991; Buchholz, 2017; Menon & Rozman, 2007), it is not surprising that Cu‐induced increases in ROS have been postulated to interfere with metamorphosis (Huang et al., 2020; Figure 2). Studies on multiple amphibian life stages have measured a variety of indices indicating Cu increases oxidative stress. Experiments on embryo‐larval stages of B. gargarizans demonstrate that Cu alters the expression of genes involved in fatty acid β‐oxidation genes (acolxl, scp, and echs1) and lipid synthesis (kar, aclsl3, adsl4, and tecr), likely in response to lipid peroxidation (Huang et al., 2020). Concomitant with these changes, up‐regulation of genes involved in controlling oxidative stress (sod, gpx, and hsp90) along with changes in the expression of genes involved in apoptotic control (bcl‐1 and bax) were observed (Huang et al., 2020).

In general and not specific to amphibians or Cu, multiple MIEs, including TH synthesis, TH metabolism, TH transport, xenobiotic receptor activation, and thyroid hormone receptor expression and transactivation, have been identified in the thyroid AOP (Noyes et al., 2019). Some studies have speculated a direct effect of Cu on the HPT axis and postulated endocrine disruption (Chai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016), but there is considerable evidence that contradicts this hypothesis. The histological information presented on effects to the thyroid (Wang et al., 2016) are of limited diagnostic value, leaving uncertainties regarding this result (Wolf et al., 2021). Specifically, nuclear superimposition resulting from thyroid follicles tangentially sectioned were misdiagnosed as follicular cell hyperplasia. Observed changes in gene expression associated with TH (dio2, dio3, trα, trβ) are suggestive of a potential decrease in TH at the tissue level, subsequently decreasing expression of thyroid hormone receptors and the antioxidant system, thus altering metamorphic processes. However, the lack of measurement of peripheral TH concentrations presents a large data gap because the complexity of feedback loops during prometamorphosis and metamorphic climax limits the interpretive value of gene expression data in the absence of direct measurements of peripheral TH concentrations. Currently there is no evidence to support the suggestion that observed changes in gene expression associated with TH metabolism are the result of endocrine disruption, which would require specific confirmation of the direct interactions between Cu and receptor ligands involved in TH synthesis, transport, metabolism, or transactivation.

An alternative, and currently better supported, hypothesis Is that these systems are impacted by oxidative stress and increased apoptosis in early development (Huang et al., 2020). This results in generalized systemic toxicity, which manifests as delayed metamorphosis and growth on a morphological level, and indiscriminate changes in gene expression on a molecular level. Support for this hypothesis includes alterations in gene expression for fatty acid β‐oxidation elements and lipid metabolism potentially in response to lipid peroxidation. There are also Cu‐induced changes in sod, cat, and gpx expression during early development indicative of oxidative stress at the cellular and tissue level, and ultimately alteration of ROS defense. These changes in ROS defense and cellular oxidative state may alter the apoptotic processes that are important in developmental and metamorphic processes. Changes in oxidative stress may also lead to visceral organ system and metamorphic tissue damage, which in turn can affect bioenergetics. A similar process can be described for effects on the control of apoptosis, but altered apoptotic control may also lead to direct effects on the highly orchestrated metamorphic processes.

Ultimately, oxidative effects on autonomous metamorphic tissues can lead to modulation of the primary HPT MIEs identified above and subsequently to delayed metamorphosis without direct involvement of the HPT axis. The effects on these indirect endocrine‐based MIEs may then result in delayed metamorphosis. Importantly, compromised visceral organ function may also lead to generalized systemic (non‐HPT) effects on growth and lethality or systemic (non‐HPT) pre‐metamorphic developmental delay. Regardless of which process is affected and the proposed mode of action, the primary population level responses are altered population structure, extinction, and alteration of the food web at the community level.

Effects on fish embryo development

Although fish do not undergo the complex metamorphic process just described for amphibians (Effects on early development and metamorphosis in amphibians), embryo development in fish has been shown to be relatively sensitive to Cu and potentially linked to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has been measured in Cu‐exposed embryos of multiple fish species at environmentally relevant concentrations (Xu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Several studies in D. rerio embryos have demonstrated down‐regulation of Wnt signaling pathways, which are critical for normal embryo development and are also down‐regulated in response to oxidative stress in mammalian systems.

Copper‐induced effects on swim bladder development in D. rerio embryos leads to a noninflatable bladder (Xu et al., 2017). These effects have been linked to down‐regulation of Wnt signaling genes (ndk1, axin2, znf703, fzd3) and associated down‐regulation of swim bladder initiation genes (sox2, pbx1). The observed effects were subsequently eliminated when fish were also exposed to a Wnt signaling agonist, providing evidence that the down‐regulation of this pathway was responsible (Xu et al., 2017).

Copper has also been shown to increase defective development (truncation, branching, improper enervation) of secondary motor neurons (Sonnack et al., 2015). These effects appear to lead to reduced embryo hatching success via reduced locomotor activity of the embryos during hatching (Zhang et al., 2018). Again, the Wnt signaling pathway is implicated in this effect, as clearly shown by using a Wnt signaling agonist to rescue the effect. Furthermore, the introduction of ROS scavengers to the system also partially rescued this effect and a cox17 mutant line of D. rerio, which is not susceptible for Cu‐induced ROS, was also not susceptible to Cu‐induced effects on hatching. These findings all support the link between oxidative stress, Wnt signaling, and developmental effects leading to reduced hatching success (Zhang et al., 2018). The available data indicate Cu does not elicit effects on the early life stages of fish via endocrine mediated pathways.

Effects on fish reproduction

Reproduction is typically the most sensitive apical endpoint for fish in sublethal Cu exposures (Horning & Neiheisel, 1979; Mount, 1968; Pickering et al., 1977). As in all vertebrates, reproduction is under the control of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, but in oviparous organisms such as fish there is also an important role for the liver, which produces egg‐yolk proteins such as vitellogenin. At a high level, there are several potential pathways by which Cu could initiate effects that lead to impacts on reproduction. These include bioenergetic effects, oxidative damage to the liver that impacts vitellogenesis, oxidative damage to the gonads that impairs endocrine pathways, oxidative damage to the gonads that leads to direct reproductive impairment, and endocrine disruption. As discussed later in Effects on Bioenergetics, it is clear that Cu can elicit bioenergetic effects on fish via several pathways. Furthermore, given the higher energetic costs of reproduction and the direct link between energy stores and fecundity, this appears to be a viable pathway, but mechanistic linkage and quantification of impacts of bioenergetic effects at lower levels of biological organization on apical endpoints like reproduction remain elusive.

Copper is rapidly accumulated in the fish liver (Grosell et al., 2001; Kamunde et al., 2002) and at high concentrations can cause oxidative stress, potentially disrupting various aspects of liver function (Machado et al., 2013). Linkages between Cu effects on the liver and fish reproduction were studied in Pimephales promelas (Driessnack et al., 2016; 2017). These studies exposed fish to 45–80 μg L−1 Cu for 21 days and observed a 55%–69% reduction in egg production normalized for the number of spawning events, but no effects on female gonado‐somatic index (GSI) were noted. No effects on circulating estradiol concentrations or vitellogenin (vtg) gene expression were observed with exposure to Cu, but er‐αa expression was reduced in one of the two studies. Overall, these studies do not provide evidence that Cu effects on the liver, beyond a potential generalized bioenergetic effect, are strongly linked to subsequent effects on fish reproduction in P. promelas.

In vertebrates in general, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus in response to internal and external cues stimulating production of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which in turn interact with receptors in the gonads to initiate reproductive steroidogenesis and gametogenesis (Wootton & Smith, 2015). Several studies have undertaken investigations on whether Cu exposure impacts the HPG axis in fish. The study by Cao et al. (2019) on D. rerio is the most comprehensive, with those by Zhang et al. (2016) on Pelteobagrus fulvidraco and Garriz et al. (2019) on Odontesthes bonariensis generally providing supporting information on some aspects of the HPG axis. However, we note that female GSI was unusually low (~5%) in the control group of the Cao et al. (2019) study, suggesting these fish were just reaching reproductive maturity, and there were inconsistencies in the reported weights for fish at the beginning and end of the study. The extent to which these issues confound the study results and interpretation described below is unclear.

Copper was shown to actually stimulate expression of gnrh2 and gnrh3 in zebrafish hypothalamus, while corresponding receptors in the pituitary (gnrhr1, gnrhr2) were down‐regulated along with fshβ and lhβ (Cao et al., 2019). Zhang et al. (2016) supported these observations with measured decreases in serum FSH and LH whereas Garriz et al. (2019) contradicted them with measured increases in lhβ expression. The mechanism for up‐regulation of gnrh2 and gnrh3 expression was not investigated, but GnRH is known to be regulated by kisspepsin, which in turn is regulated by neurokinin‐β (nkβ; Peacey, Elphick, et al., 2020). Both GnRH and nkb are known to bind Cu in vertebrates and echinoderms (Peacey, Elphick, et al., 2020; Peacey et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2019), with the Cu–GnRH complex having a higher affinity for GnRH receptors and/or triggering alternative signaling pathways that lead to enhanced release of FSH and LH compared with the unbound form (Gajewska et al., 2016). This suggests Cu, as an essential element, may have a regulatory role in GnRH activity even at normal, homeostatically controlled concentrations. Within this context, it is difficult to infer the mechanisms that would lead to up‐regulation of gnrh2 and gnrh3 and down‐regulation of corresponding receptors. In mammalian systems, the pulse frequency of GnRH is known to influence GnRH receptor expression, but this has not been explored in piscine systems (Bedecarrats & Kaiser, 2003).

As an alternative to the top‐down mechanism described in the previous paragraph, all three of these studies demonstrated histopatholgical lesions on the ovaries and testis of Cu‐exposed fish, potentially the result of oxidative stress (Cao et al., 2019; Garriz et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2016). Oxidative damage to gonads will most likely directly interfere with gonadal steroidogenesis, with subsequent feedback loops initiated by reduced reproductive steroid levels leading to effects on the hypothalamus and pituitary. The down‐regulation of fshr, lhr, star, cyp11a, 3βhsd, cyp17, and 17βhsd in the gonads along with reductions in serum concentrations of estradiol (females), progesterone (females), testosterone (males), and 11‐KT (males and females) and genes involved in regulatory feedbacks (cyp19b, erα, er2βb, and ar) despite up‐regulation of gnrh2 and gnrh3 are generally consistent with this pathway (Cao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2016) but are not conclusive. Within this context, the up‐regulation of gnrh2 and gnrh3 may be an attempted compensatory response to down‐regulation of steroidogenesis resulting from oxidative tissue damage in the gonads.

Overall, these studies provide evidence that Cu disturbs fish reproduction through either direct tissue damage and/or damage to tissue in the HPG axis ultimately resulting in reduction of critical sex steroid hormones. Effects on organism bioenergetics are likely to also contribute to the Cu‐induced effects on fish reproduction, but studies to date have not quantified the magnitude of this contribution. The prevailing data suggest these changes are initiated by oxidative stress and subsequent tissue damage in the gonads, with various feedback loops in the HPG axis causing a cascade of changes in gene expression circulating hormone levels. Currently, no data support the alternative hypothesis that Cu directly interferes with receptor binding domains somewhere in the HPG axis leading to endocrine disruption, but this possibility cannot be entirely ruled out given the known role of Cu as an essential element in GnRH activity.

EFFECTS ON BIOENERGETICS

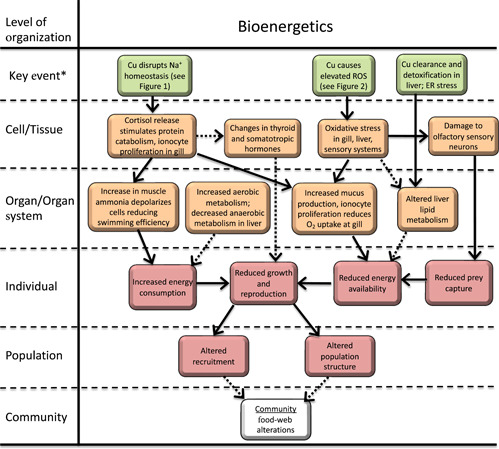

Copper exposure can affect organism bioenergetics and ultimately growth and reproduction in several ways, with multiple MIEs potentially contributing to this AOP. We identified five KEs involved in alterations to overall energy metabolism in aquatic organisms: changes in food intake rate, changes in oxygen diffusion across the gill, changes in hormone concentrations, changes in liver metabolism, and elevated muscle ammonia (Figure 3). The relative importance of each component of this AOP depends on the species and on the magnitude and duration of Cu exposure and is generalized in our review.

Figure 3.

Adverse outcome pathway for effects of Cu on bioenergetics in freshwater vertebrates. Solid lines indicate relationships that are well supported in the literature. Dashed lines indicate hypothesized relationships or relationships supported by limited or conflicting data. *Note, in this figure pathways are initiated by key events. Molecular initiating events are described in other figures or are unkown. ROS = reactive oxygen species; ER = endoplasmic reticulum.

Changes in food intake rate

As described previously in Effects on fish sensory systems, there is support for Cu‐induced oxidative stress to induce apoptosis of specialized cells in the olfactory rosette that result in altered or inhibited sensory input. On a whole‐organism level, impaired olfaction by Cu has been shown to affect the ability to locate food, likely leading to a net reduction in food intake (Kuz'mina, 2011). Several studies have also demonstrated more generalized changes in food intake in response to Cu exposure, but the effect varies by species. Transient (14 days) reductions in food intake followed by recovery to control levels have been observed in common carp (De Boeck et al., 1997), whereas long‐term (45 days) increases in food intake have been observed in rainbow trout (McGeer et al., 2000). Although there are suggestions that increases in food intake may be due to the increased costs of Cu detoxification, this hypothesis remains quite speculative and no MIEs with supporting data have been identified for these nonolfactory‐based changes in feeding.

Changes in oxygen diffusion across the gill

Copper exposure in fish can cause hypertrophy and hyperplasia of gill cells, as well as increased mucus production, all of which increase the diffusion distance for oxygen into the gill (see Tavares‐Dias [2021] for overview). These changes may be the result of oxidative stress and/or disruption of Na+ homeostasis, but are typically only observed at Cu concentrations that rarely occur in the environment (>100 μg L−1). In addition, as described earlier, cortisol release can result in ionocyte proliferation contributing to increased O2 diffusion distance at the gill (Figure 1). In studies at environmentally relevant Cu concentrations, routine oxygen uptake is generally not compromised in rainbow trout, although reductions in maximum oxygen consumption rates have been observed (De Boeck et al., 2006; Waiwood & Beamish, 1978). Similarly, oxygen consumption is only transiently (<3 days) reduced in common carp and gibel carp even when blood oxygen levels remained chronically reduced (De Boeck et al., 2006; 2007). Chronic reductions in blood oxygen levels in carp were linked to behavioral hypoventilation, gill remodeling, and the capacity for anaerobic metabolism rather than structural damage. However, increases in Pcrit have been observed in Cu‐exposed fish consistent with the hypothesis that Cu imparts limitations of O2 uptake (De Boeck et al., 1995). Consequently, there does appear to be some conditions under which O2 diffusion is limited as a result of Cu exposure and therefore may play a role in fish bioenergetics.

Effects on hormones involved in energy metabolism

Many hormones are involved directly or indirectly in fish and amphibian bioenergetics. The effects of Cu exposure on the concentrations or gene expression of hormones involved in bioenergetics, as well as gene expression of associated hormone receptors, has not been studied extensively. As described earlier for amphibians, Effects on early development and metamorphosis in amphibians, THs in fish contribute to regulation of organism development, metabolism, and growth. The effects of Cu exposure on piscine THs and their receptors are often transient and overall quite variable, with responses depending on species, exposure level, and timing of exposure (Eyckmans et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2008; Ruuskanen et al., 2020). The variability in responses makes it unclear whether there is any link between these observations and apical endpoints like growth and reproduction. These changes in TH are likely the result of direct oxidative damage to the thyroid and/or endocrine modulation (response of TH to some other Cu‐induced disturbance). There is no evidence these changes in TH are a result of direct endocrine disruption.

The somatotropic axis, or growth hormone–insulin‐like growth factor axis, in fish is involved in lipid, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism, with subsequent effects on growth and reproduction (Butler & Le Roith, 2001; Norris & Carr, 2020). In a life‐long (345 days) exposure in guppies, Poecilia vivipara, exposure to 5 and 9 μg L−1 Cu elicited 25% and 34% reductions in growth (Zebral et al., 2018). Reduced mRNA expression for the growth hormone receptor ghr2, and reduced igf1 and igf2 mRNA expression were observed in fish muscle, but without a concomitant change in growth hormone receptor (GHR) concentration. Differences between gene expression and protein concentration may be the result of the protein assay not differentiating between GHR isoforms. Considering only the gene expression data, the reduced ghr2 mRNA expression may cause an insensitivity of the skeletal muscle to growth hormone, resulting in reduced igf1 and igf2 mRNA expression and therefore reduced growth. However, given the lack of change in protein concentrations, inferences that Cu meaningfully altered the somatotropic axis leading to effects on fish growth are uncertain. Overall, it can be postulated that any observed changes to thyroid and somatotropic hormone levels are compensatory mechanisms which allow organisms to respond to stress factors and cope with elevated Cu exposure, but conclusive evidence is currently lacking.

Effects on liver metabolism

In fish, circulating Cu is rapidly cleared from plasma by the liver (Grosell et al., 2001; Kamunde et al., 2002), where it is bound to ceruloplasmin and then either excreted via the bile or stored in protein complexes (Grosell, 2012). Copper accumulation rates have the potential to exceed detoxification rates, leading to oxidative stress in the liver (Machado et al., 2013). Alternatively, enhanced detoxification in the liver may impart bioenergetic costs. Consistent with the latter hypothesis, at a cellular level, and comparable to mammals (Belyaeva et al., 2011), in vivo Cu exposure elevates hepatic mitochondrial electron transport system activity and in some experiments citrate synthase activity (Anni et al., 2019; Sappal et al., 2015; Zebral et al., 2020). Conversely, Cu exposure generally reduced hepatic lactate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase activity, indicating a corresponding reduction in anaerobic metabolic pathways (Anni et al., 2019; Vieira et al., 2009; Zebral et al., 2020), which also may be the result of oxidative stress (Anni et al., 2019). Despite reductions in anaerobic metabolism, overall there appears to be increased energy use in the liver in response to Cu exposure. The magnitude of this effect and consequent impact on the energy balance of other physiological systems is uncertain.

In addition to changes in liver energy consumption, Cu also alters hepatic lipid metabolism in a time‐dependent manner. In general, Cu exposures on the order of 1 month in duration have demonstrated increases in hepatic lipid content and corresponding increases in hepatosomatic indices (HSI) in fish (Chen, Luo, Liu, et al., 2013). Conversely, longer exposures (or later time‐point samples within the same experiment) result in reduced hepatic lipid content and HSI (Chen, Luo, Pan, et al., 2013). This pattern is also observed in studies that sampled multiple time points supported by a time effect rather than study effect (Huang et al., 2014; Song et al., 2016). Detailed studies in yellow catfish (Peltiobagrus fulvidraco) demonstrate that increased hepatic lipid content is caused by Cu‐induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, but the MIE for this effect is unknown. In ER stress, an accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins in the ER leads to an unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is a series of signaling cascades that aims to return ER homeostasis and triggers SREBP‐1c, a transcription factor that regulates multiple genes (fatty acid synthase, acetyl CoA carboxylase) involved in lipogenesis (Song et al., 2016). Studies have shown up‐regulated expression of these genes in the first 30 days of Cu exposure, followed by down‐regulation at later time points (Chen, Luo, Pan, et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2014; Song et al., 2016). It is suggested this down‐regulation is the result of re‐establishment of ER homeostasis.

Increased muscle ammonia

Copper exposure consistently results in elevated plasma and muscle ammonia concentrations (Beaumont, Butler, et al., 2000, 2003; Lauren & McDonald, 1985). A MIE for this effect has not been conclusively demonstrated, but is likely at least partly related to a generalized stress response to Cu exposure resulting in elevated plasma cortisol (Beaumont et al., 2003; De Boeck et al., 2001; Monteiro et al., 2005; Tellis et al., 2012), which promotes protein catabolism leading to increased ammonia production (Beaumont et al., 2003). This hypothesis is supported by observations of reduced muscle and liver protein (De Boeck et al., 1997) during Cu exposures and a reduction in plasma and muscle ammonia when cortisol synthesis is pharmacologically blocked in Cu‐exposed fish (Beaumont et al., 2003). Alternatively, or in combination, there is some evidence that Cu can directly inhibit Rhesus proteins involved in ammonia excretion at the gills (Lim et al., 2015).

Elevated muscle ammonia can depolarize muscle cells through displacement of K+ in cellular ion exchange, reducing the capacity for intense swimming (Beaumont, Butler, et al., 2000; Beaumont, Taylor, et al., 2000; De Boeck et al., 2006). This is supported by observations of increased (30%) energy demand, as measured by oxygen consumption, at the same swimming speed in Cu‐exposed rainbow trout and reductions in maximum sustainable swimming speeds (Beaumont, Butler, et al., 2000; McGeer et al., 2000; Waiwood & Beamish, 1978). This effect could contribute significantly to overall bioenergetic effects through a general increase in the cost of transport as well as increased costs during burst swimming events such as prey capture and predator avoidance.

DISCUSSION

The overall objective of our analysis was to evaluate known and hypothesized mechanisms of action for Cu in freshwater aquatic vertebrates, including the ways in which Cu may interact with the endocrine system. To accomplish this, we used a generalized AOP framework to summarize the literature and attempt to provide linkages from MIEs through to AOs at the whole‐animal level of biological organization. As an essential element, it is not surprising that elevated Cu concentrations in the environment and subsequently in organisms can interact with multiple, and in many cases overlapping, physiological pathways.

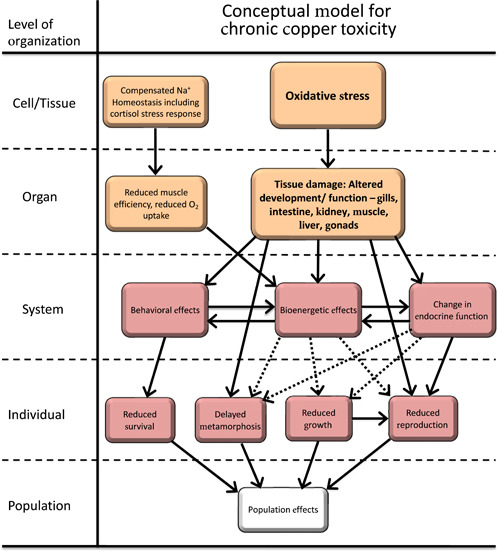

At a high level, our evaluation indicates sublethal Cu exposure to aquatic vertebrates has the potential to exert toxicity primarily through oxidative stress with a generally lesser role of compensatory responses to disruption of Na+ homeostasis (Figure 4). Maintenance of Na+ homeostasis includes cortisol‐mediated compensatory responses that reduce muscle efficiency and elicit ionocyte proliferation in the gills, which reduces uptake of O2, both of which may alter energy budgets.

Figure 4.

High‐level conceptual model of adverse outcome pathways for chronic Cu exposure to vertebrates integrating the more detailed adverse outcome pathways presented in Figures 1 through 3. Solid lines indicate relationships that are well supported in the literature. Dashed lines indicate hypothesized relationships or relationships supported by limited or conflicting data. Oxidative stress and tissue damage are shown in bold to highlight the dominant pathway for chronic Cu toxicity. Change in endocrine function is due to direct tissue damage from oxidative stress and is not endocrine disruption.

Copper is effective at generating ROS, with numerous studies showing Cu‐induced ROS can overwhelm antioxidant systems, leading to oxidative stress. Copper‐induced oxidative stress has been measured in most tissues and organ systems of aquatic vertebrates, where it can increase apoptosis and alter signaling pathways. The resulting tissue damage can manifest in a variety of ways involving altered sensory behavior, gill morphology, and liver metabolism that ultimately impact bioenergetic budgets (Figure 3). Changes in energy budget can then negatively impact key apical endpoints like growth, metamorphosis, and reproduction (Figure 4).

The wide‐ranging oxidative stress and corresponding cellular damage to organs and tissues includes those involved in endocrine regulation (Figure 2). The available weight of evidence suggests Cu‐induced oxidative damage to tissues may be an important mechanism by which alterations in endocrine signaling occur. The extensive feedback loops involved in major endocrine pathways such as the HPT and HPG axes are apt to facilitate a cascade of changes in hormone and hormone receptor levels if tissue damage inhibits the biosynthesis of any hormone in the axis, leading to dysfunction in apical endpoints. Overall, the linkage between oxidative stress and histopathological effects on endocrine systems is reasonably well supported, but not conclusive.

We did not identify any study that directly supports the hypothesis that observed changes in endocrine axes in response to Cu exposure are the result of endocrine disruption. Copper is known to bind to several hormones, providing pathways for it to negatively interact with the endocrine system (Stevenson et al., 2019). Binding sites on GnRH‐1, GnRH‐2, and neurokinin‐β are perhaps the most obvious links to apical endpoints given their critical role in reproduction, but the available data does not support disruption of endocrine function via this mechanism. Although there is no direct evidence of Cu‐mediated endocrine disruption, we simply point out that Cu can directly bind to hormones in the endocrine system and that detailed studies of these interactions in aquatic vertebrates have not been undertaken, precluding us from conclusively eliminating any role of Cu in endocrine disruption.

Our analysis highlighted additional significant uncertainties in the AOPs for Cu. First, the AOP for effects on amphibian metamorphosis (Figure 2) would benefit from more detailed evaluations of each developmental window during Cu exposure to determine the metamorphic phases in which Cu‐induced developmental delay is initiated and the associated endocrine and bioenergetic status at these phases. Second, although there does appear to be a link between oxidative stress‐induced damage to gonads and altered steroidogenesis in fish, further study of this pathway is needed to discriminate between direct effects on the HPG axis and any secondary effects (e.g., bioenergetic) that could also indirectly impact this axis. It is important that future studies on the fish HPG axis include the measurement of hormone levels and not rely so heavily on gene expression data. Finally, the largest uncertainty surrounds the linkage between altered bioenergetics and apical endpoints (metamorphosis, growth, reproduction). Multiple AOPs incur, or have the potential to incur, bioenergetic costs and additional pathways may alter energy metabolism as a result of Cu exposure (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). However, quantification of these costs and alterations is generally difficult and typically only undertaken at the whole‐animal level of organization (if at all), limiting our ability to understand the relative importance of alterations in bioenergetic pathways on apical endpoints (Figure 4). More detailed studies on energy budgets and status at the system or organ level are needed to better populate emerging dynamic energy budget models (Chen et al., 2012; Vlaeminck et al., 2021) and to better link these effects to apical and higher level endpoints.

In conclusion, significant progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms by which Cu exerts sublethal effects on aquatic vertebrates. The accumulated weight of evidence indicates that oxidative stress leading to tissue damage and downstream effects on bioenergetics and endocrine function are the primary mechanisms of toxicity, although other pathways may contribute in more subtle ways. There is no evidence that Cu acts as an endocrine disruptor on aquatic vertebrates, but this pathway cannot be conclusively ruled out with the available studies to date.

Author Contributions Statement

Kevin V. Brix: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Gudrun De Boeck: Formal analysis; Writing—original draft. Stijn Baken: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Writing—original draft. Douglas J. Fort: Formal analysis; Writing—original draft.

Acknowledgments

C. Poland and two anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. The International Copper Association provided financial support for this research.

Data Availability Statement

This is a critical review. All evaluations were conducted based on published papers accessible in the peer reviewed literature. (KevinBrix@EcoTox.onmicrosoft.com).

REFERENCES

- Allen, G. R. (1991). Oxygen reactive species and antioxidant responses during development: The metabolic paradox of cellular differentiation. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 196, 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley, G. T. , Bennett, R. S. , Erickson, R. J. , Hoff, D. J. , Hornung, M. W. , Johnson, R. D. , Mount, D. R. , Nichols, J. W. , Russom, C. L. , Schmieder, P. K. , Serrano, J. A. , Tietge, J. E. , & Villeneuve, D. L. (2010). Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 29, 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anni, I. S. A. , Zebral, Y. D. , Afonso, S. B. , Abril, S. I. M. , Lauer, M. M. , & Bianchini, A. (2019). Life‐time exposure to waterborne copper III: Effects on the energy metabolism of the killifish Poecilia vivipara . Chemosphere, 227, 580–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldisserotto, B. , Mancera, J. M. , & Kapoor, B. G. (2007). Fish osmoregulation. Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, D. H. , Sandahl, J. F. , Labenia, J. S. , & Scholz, N. L. (2003). Sublethal effects of copper on coho salmon: Impacts on nonoverlapping receptor pathways in the peripheral olfactory nervous system. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 22, 2266–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, M. W. , Butler, P. J. , & Taylor, E. W. (2000). Exposure of brown trout, Salmo trutta, to a sub‐lethal concentration of copper in soft acidic water: Effects upon muscle metabolism and membrane potential. Aquatic Toxicology, 51, 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, M. W. , Butler, P. J. , & Taylor, E. W. (2003). Exposure of brown trout Salmo trutta to a sublethal concentration of copper in soft acidic water: Effects upon gas exchange and ammonia accumulation. Journal of Experimental Biology, 206, 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, M. W. , Taylor, E. W. , & Butler, P. J. (2000). The resting membrane potential of white muscle from brown trout (Salmo trutta) exposed to copper in soft, acidic water. Journal of Experimental Biology, 203, 2229–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedecarrats, G. Y. , & Kaiser, U. B. (2003). Differential regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene promoter activity by pulsatile gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) in perfused LBT2 cells: Role of GnRH receptor concentration. Endocrinology, 144, 1802–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyaeva, E. A. , Korotkov, S. M. , & Saris, N. E. (2011). In vitro modulation of heavy metal‐induced rat liver mitochondrial dysfunction: A comparison of copper and mercury with cadmium. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 25S, S63–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bletz, M. C. , Goedbloed, D. J. , Sanchez, E. , Reinhardt, T. , Tebbe, C. C. , Bhuju, S. , Geffers, R. , Jarek, M. , Vences, M. , & Steinfartz, S. (2016). Amphibian gut microbiota shifts differentially in community structure but converges on habit‐specific predicted functions. Nature Communications. 7, 13699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brix, K. V. , Schlekat, C. E. , & Garman, E. R. (2017). The mechanisms of nickel toxicity in aquatic environments: An adverse outcome pathway analysis. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36, 1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, D. R. (2017). Xenopus metamorphosis as a model to study thyroid hormone receptor function during vertebrate developmental transitions. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 459, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, D. R. , Paul, B. D. , Fu, L. , & Shi, Y. B. (2006). Molecular and developmental analyses of thyroid hormone receptor function in Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 145, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckbinder, L. , & Brown, D. D. , 1993. Expression of the Xenopus laevis prolactin and thyrotropin genes during metamorphosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 90, 3820–3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A. A. , & Le Roith, D. (2001). Control of growth by the somatotropic axis: Growth hormone and insulin‐like growth factors have related and independent roles. Annual Review of Physiology, 63, 141–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan, R. H. , & Zeiger, W. N. , 1978. Biochemical studies of olfaction: Binding specificity of radioactively labeled stimuli to an isolated olfactory preparation from rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 75, 4679–4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, P. G. C. (1995). Interactions between trace metals and aquatic organisms: A critique of the free‐ion activity model in metal speciation and bioavailability. In Tessier A. & Turner D. R. (Eds.), Aquatic systems (pp. 45–102). John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. , Wang, G. , Wang, T. , Chen, J. , Wenjing, G. , Wu, P. , He, X. , & Xie, L. (2019). Copper caused reproductive endocrine disruption in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic Toxicology, 211, 124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L. , Chen, A. , Deng, H. , & Wang, H. (2017). Inhibited metamorphosis and disruption of antioxidant defenses and thyroid hormone systems in Bufo gargarizans tadpoles exposed to copper. Water Air and Soil Pollution, 228, 359. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. , Luo, Z. , Liu, X. , Song, Y. F. , Liu, C. X. , Zheng, J. L. , & Zhao, Y. H. (2013). Effects of waterborne chronic copper exposure on hepatic lipid metabolism and metal‐element composition in Synechogobius hasta . Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 64, 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. L. , Luo, Z. , Pan, Y. X. , Zheng, J. L. , Zhu, Q. L. , Sun, L. D. , Zhuo, M. Q. , & Hu, W. (2013). Differential induction of enzymes and genes involved in lipid metabolism in liver and visceral adipose tissue of juvenile yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco exposure to copper. Aquatic Toxicology, 136–137, 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. H. , Gross, J. A. , & Karasov, W. H. (2007). Adverse effects of chronic copper exposure in larval northern leopard frogs (Rana pipiens). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 26, 1470–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Y. , Lin, C. J. , Ju, Y. R. , Tsai, J. W. , & Liao, C. M. (2012). Coupled dynamics of energy budget and population growth of tilapia in response to pulsed waterborne copper. Ecotoxicology, 21, 2264–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearwater, S. J. , Farag, A. M. , & Meyer, J. S. (2002). Bioavailability and toxicity of dietborne copper and zinc to fish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 132C, 269–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanovski, S. , Amano, T. , Li, Q. , Ueda, S. , Shi, Y. B. , & Ishizuya‐Oka, A. (2000). Role of ECM remodeling in thyroid‐hormone dependent apoptosis during anuran metamorphosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 926, 180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, G. , De Smet, H. , & Blust, R. (1995). The effect of sublethal levels of copper on oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion in the common carp, Cyprinus carpio . Aquatic Toxicology, 32, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, G. , Van der Ven, K. , Hattink, J. , Blust, R. (2006). Swimming performance and energy metabolism of rainbow trout, common carp and gibel carp respond differently to sublethal copper exposure. Aquatic Toxicology, 80, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, G. , Van der Ven, K. , Meeus, W. , & Blust, R. (2007). Sublethal copper exposure induces respiratory stress in common and gibel carp but not in rainbow trout. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 144C, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, G. , Vlaeminck, A. , Balm, P. H. M. , Lock, R. A. C. , De Wachter, B. , & Blust, R. (2001). Morphological and metabolic changes in common carp, Cyprinus carpio, during short‐term copper exposure: Interactions between Cu2+ and plasma cortisol elevation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 20, 374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, G. , Vlaeminck, A. , & Blust, R. (1997). Effects of sublethal copper exposure on copper accumulation, food consumption, growth, energy stores, and nucleic acid content in common carp. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 33, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeForest, D. K. , & Meyer, J. S. (2015). Critical review: Toxicity of dietborne metals to aquatic organisms. Critical Reviews Environmental Science Technology, 45, 1176–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Denver, R. J. (2009). Structural and functional evolution of vertebrate neuroendocrine stress systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1163, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver, R. J. (2013). Neuroendocrinology of amphibian metamorphosis. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, 103, 195–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver, R. J. , Boorse, G. C. , & Glennemeier, K. A. (2002). In Pfaff D., Arnold A., Etgen A., Fahrbach S., Moss R., & Rubin R. (Eds.), Endocrinology of complex life cycles: Amphibians (p. 469). Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, W. A. , Azizishirazi, A. , & Pyle, G. G. (2014). Contaminant‐specific targeting of olfactory sensory neuron classes: Connecting neuron class impairment with behavioural deficits. Chemosphere, 112, 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giulio, R. T. , Washburn, P. C. , Wenning, R. J. , Winston, G. W. , & Jewell, C. S. (1989). Biochemical responses in aquatic animals: A review of determinants of oxidative stress. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 8, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Di Toro, D. M. , Allen, H. E. , Bergman, H. L. , Meyer, J. S. , Paquin, P. R. , & Santore, R. C. (2001). A biotic ligand model of the acute toxicity of metals. I. Technical basis. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 20, 2383–2396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessnack, M. K. , Jamwal, A. , & Niyogi, S. (2017). Effects of chronic exposure to waterborne copper and nickel in binary mixture on tissue‐specific metal accumulation and reproduction in fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Chemosphere, 185, 964–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]