Abstract

What is Known and Objective

After more than a year of negotiation, a $740 billion climate and health care bill known as The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) became law on 16 August 2022. In addition to its impact on the environment, job creation and reducing inflation, a key focus is to reduce the burden of Medicare by over $100B per year and other benefits to 65 million Medicare patients. A fixed number of top expenditures drugs that have stayed as single‐source chemical products for 8 years and the biologicals for 12 years; 2 years more are allowed if the approval of a generic or biosimilar is imminent. Once a second source appears, as a generic or biosimilar, the price reduction is removed. The number of products negotiated for price reduction goes from 10 to 20 over the years and stays fixed at this number. Reaching any significant number out of the 14,000 reimbursed will take forever if biosimilars and generics keep entering. The IRA does not apply to private markets.

Methods

The IRA legislation and related statutes were analysed in consultation with legal teams; the spending data were derived from the CMS portals and the FDA databases to rank the most likely products selected when the selection process is initiated.

Results and Discussion

The savings to Medicare will come from reducing the price of only a few products, primarily with $1B and upward spending; when Plan B product scheduling enters, these will be at the bottom of the selection because of their lower expenditure. The total number of products subject to price reduction may be negligible if generics and biosimilars are introduced after the exclusivity period of the listed drug or reference product. The private market with an 80% share may benefit due to price spillover but mainly by the expedited entry of generics and biosimilars.

What is New and the Conclusion

The entry of generics and biosimilars will now be encouraged by brand‐name product companies, reducing the intellectual property hurdles like the “patent dance” for biosimilars. The IRA includes restrictions to prevent the brand name companies from exploiting the entry of generics and biosimilars to assure their independence.

Keywords: AAM, biosimilars, Biosimilars Council, BPCIA, CMS, FDA, Medicare, the Inflation Reduction Act

The Inflation Reduction Act gives a significant boost to generics and biosimilars!Soon lowered out‐of‐pocket costBiosimilars promoted and adopted

1. INTRODUCTION

The US has a per capita cost of $1200 per capita and total healthcare expenses of $4 trillion‐plus. This is an untenable situation. However, unlike the rest of the world, there are no price controls in the US. This is the right strategy to promote competition.

The prohibition against the federal government negotiating drug prices was a contentious provision of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, 1 the law that established the Medicare Part D program. Lifting this prohibition has been a longstanding goal for many Democratic policymakers. On 16 August 2022, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA), enacting the most significant reform for the payment of drugs and biologicals.

The lower the out‐of‐pocket healthcare cost of seniors while saving over the 10 years between 2022 and 2031, through prescription drug negotiation and the Medicare inflationary rebates, approximately $101 billion and $71 billion, respectively. In addition, a significant saving is achieved by prohibiting the Secretary from implementing the drug rebate rule adopted by the Trump Administration until 1 January 2032.

The H. R. 5376 or IRA 2 incorporates many of the drug pricing concepts, and its most important health care provisions include:

Establishing a new program for Medicare to directly negotiate prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers for certain high‐spend Medicare drugs, with stiff penalties for companies that refuse;

Requiring manufacturers to pay rebates on drugs reimbursed under Medicare Parts B or D for which average (i.e. net) prices increase faster than inflation;

Revamping the Medicare Part D benefit, including establishing an annual out‐of‐pocket cap for beneficiary cost‐sharing on prescription drugs and eliminating patient cost‐sharing in the catastrophic phase;

Delaying the effective date of the November 2020 Anti‐Kickback Statute final rule removing safe harbour protection for prescription drug rebates until 2032; and

Extending the temporarily expanded health insurance subsidies for the ACA plans through 2025.

The first two provisions are the main topic of discussion in this article. This article clarifies the Bill, removes every misconception related to the impact on biosimilar products, and demonstrates how generic and biosimilar manufacturers should take advantage of these new opportunities. Other benefits are well‐defined in detail in the Bill.

2. UNDERSTANDING THE IRA

The objectives of the IRA will be achieved through a complex financing plan, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

IRS financing 3

| Total revenue raised | $737 billion |

| 15% Corporate minimum tax | 222 billion |

| Prescription drug pricing reform | 265 billion a |

| IRS Tax enforcement | 124 billion b |

| 1% Stock buybacks fee | 74 billion a |

| Loss limitation extension | 52 billion a |

| Total investments | $437 billion |

| Energy security and climate change | 369 billion a |

| Affordable Care Act extension | 64 billion b |

| Western drought resiliency | 4 billion c |

| Total deficit reduction | $300+ billion |

Joint Committee on Taxation estimate.

Congressional Budget Office estimate.

Senate estimate, awaiting final CBO score.

The IRA:

Expands Medicare benefits: free vaccines (2023), $35/month insulin (2023) and caps out‐of‐pocket drug costs to an estimated $4000 or less in 2024 and settling at $2000 in 2025.

Lowers energy bills: cuts energy bills by $500–$1000 per year.

Makes historic climate investment: reduces carbon emissions by roughly 40% by 2030.

Lowers health care costs: saves the average enrolee $800/year in the ACA marketplace, allows Medicare to negotiate 100 drugs over the next decade, and requires drug companies to rebate back price increases higher than inflation.

Creates manufacturing jobs: more than $60 billion investment will create millions of new domestic clean manufacturing jobs.

Invests in disadvantaged communities: cleaning up pollution and taking steps to reduce environmental injustice with $60 billion for environmental justice.

Closes tax loopholes used by the wealthy: a 15% corporate minimum tax, a 1% fee on stock buybacks and enhanced IRS enforcement.

Protects families and small businesses making $400,000 or less.

It helps 13 million people save an average of $800 a year on health insurance premiums.

Add insurance to 3 million more people will have health insurance than otherwise would without the law, according to the White House summary. 4 It does not affect private insurance or drug markets. It is also not a free insurance program as widely misrepresented.

The current CBO score 5 reports even the legislation would reduce deficits by $305 billion through 2031—including over $100 billion of net scoreable savings and another $200 billion of gross revenue from stronger tax compliance. Because the prescription drug savings would be larger than new spending, CBO finds the legislation would modestly reduce net spending by almost $15 billion through 2031, including nearly $40 billion in 2031. The legislation would generate almost $300 billion of net revenue over a decade, mostly from improved tax compliance and the spillover effects of higher wages as a result of lower health premiums—neither of which are tax increases—along with early revenue collection as corporations shift the timing of certain payments. Overall, CBO estimates the legislation includes $790 billion of offsets to fund roughly $485 billion of new spending and tax breaks as negotiators account for the policies, it includes $739 billion of offsets and $433 billion of investments.

To better understand how the IRA will transform American society, we need to look at the current state of healthcare in America.

The US has the highest national health expenditure (NHE) than other wealthy countries, reaching more than $4 trillion in 2020, or about $12,000 a person, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 6 However, other wealthiest countries have a much lower cost, 7 and the cost in developing countries is less than $200 per person. 8

One reason for the high cost of healthcare in the US is the cost of medication, which averages around $1200 per capita, 9 which is almost 20% of the GDP. To reduce the burden of drug costs, the US introduced the Hatch‐Waxman Bill 10 in 1984 to introduce generic drugs, and now 90% of all drugs dispensed are generics. 11 Yet they only constitute about 15% of the expenditure, the balance going to branded drugs. It is important to remember that the Hatch‐Waxman Act was not a cost‐fixing Bill; it allowed competition that brought the cost down. Without this Bill, we will be paying hundreds of billions more for drugs in the US.

The developers justify the high cost of new drugs to pay for developing new drugs that run around a billion dollars 12 ; it is evident that the US brings the highest number of new drugs 13 spending hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Despite the cost constraints, the US has the best healthcare system that should continue as an uncontrolled system, unlike the rest of the world; the social medicine system, as applied in many jurisdictions, has never worked well; Canada 14 and the UK 15 are just two examples. The US system works well and needs fine‐tuning, which the IRA aptly provides.

Since the US never had any price control contrary to such policies worldwide, including in the wealthiest countries that also partake in developing new drugs. The campaigns to control drug prices in the US have failed for various reasons, including the lobby efforts of the big pharma. In addition, the high cost of drugs brings a tremendous burden to the US government through the CMS Medicare and Medicaid plans. Some relief was provided to private insurance through the Affordable Care Act, 16 yet the US government obligations remained high; now, there is hope that the IRA will reduce these costs.

The primary source for these changes will come from the CMS, responsible for Medicare and Medicaid. Therefore, the IRA is mainly focused on the scope and activities of the CMS and its budget 17 :

In 2022, CMS will reimburse over $110B for Part D 18 and $50B for Part B drugs. 19

Medicare spending grew 3.5% to $829.5 billion in 2020 or 20% of total NHE.

Medicaid spending grew 9.2% to $671.2 billion in 2020 or 16% of total NHE.

Private health insurance spending declined 1.2% to $1151.4 billion in 2020 or 28% of total NHE.

Out‐of‐pocket spending declined 3.7% to $388.6 billion in 2020 or 9% of total NHE.

Federal government spending for health care grew 36.0% in 2020, significantly faster than the 5.9% growth in 2019. This faster growth was largely in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Hospital expenditures grew 6.4% to $1270.1 billion in 2020, slightly faster than the 6.3% growth in 2019.

Physician and clinical services expenditures grew 5.4% to $809.5 billion in 2020, faster than the 4.2% in 2019.

Prescription drug spending increased 3.0% to $348.4 billion in 2020, slower than the 4.3% growth in 2019.

The federal government sponsored the most significant share of total health spending (36.3%) and the households (26.1%). The need for reducing this burden is evident as the NHE is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.4% to reach $6.2 trillion by 2028.

- The total expenditure for both Part D and B was $435.6B in 2020 (the most recent data available):

- For Part B drugs, the amount was $38.52B; seven drugs with $1B+ expenditure accounted for $13.16B. Total drugs reimbursed are 600.

- For Part D drugs, the amount was $397.3B, with 40 drugs with billing of $1B+, and the total amount of these drugs was $78.6B. Total drugs reimbursed 13,570.

- Part D and B total for drugs over $1B was $91.75B for 45 drugs.

3. THE NEW PROGRAM FOR MEDICARE

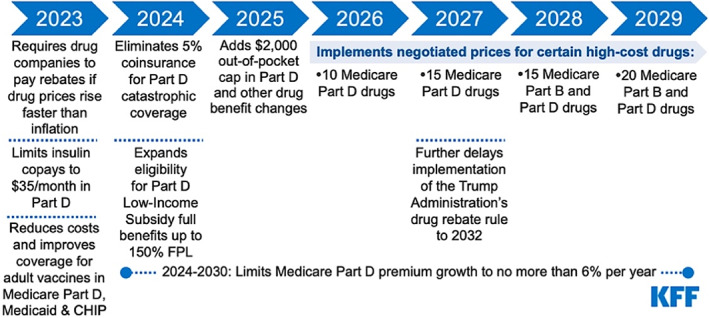

The IRA requires negotiating and renegotiating the prices that will commence in 2026 based on a tiered schedule (Figure 1). It is noteworthy that biologicals are primarily included in Part B unless it is a dispensed product such as adalimumab that is included in Part D. Most concerns about biosimilars related to Part B where the price negotiation starts in 2027, provided the entries in Part B drugs are higher than the entries in Part B, as it would be a combined selection.

FIGURE 1.

Implementation timeline of the prescription drug provisions in the IRA (https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue‐brief/how‐will‐the‐prescription‐drug‐provisions‐in‐the‐inflation‐reduction‐act‐affect‐medicare‐beneficiaries/). It is anticipated that by 2031, up to 100 drugs could be subject to price negotiation.

Table 2 list the top 74 drugs for 2020 spending drugs of CMS on Part D and Part B 20 —the most likely drugs to be selected in the first round of the price negotiation in 2026 for Pard D and 2028 for Part B, subject to the exclusivity, the change of current spending and availability of generics of biosimilars or being part of another reimbursement program such as the Social Security or the plan for insulins.

TABLE 2.

Part D and Part B drugs 2020 spending

| No. | Part | Brand | Generic | Approved | 2020 Spending | Qualified | Eligible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D | Eliquis | Apixaban | 2014 | 9,936,069,814 | Yes | 2021 |

| 2 | D | Revlimid | Lenalidomide | 2017 | 5,356,050,275 | Yes | 2024 |

| 3 | D | Xarelto | Rivaroxaban | 2011 | 4,701,314,805 | Yes | 2018 |

| 4 | D | Januvia | Sitagliptin Phosphate | 2006 | 3,865,087,773 | Yes | 2013 |

| 5 | B | Keytruda | Pembrolizumab | 2016 | $3,500,947,569 | No* | 2027 |

| 6 | D | Trulicity | Dulaglutide | 2014 | 3,284,873,062 | Yes | 2021 |

| 7 | B | Eylea | Aflibercept | 2011 | $3,013,081,886 | No* | 2022 |

| 8 | D | Imbruvica | Ibrutinib | 2017 | 2,962,909,304 | Yes | 2024 |

| 9 | D | Lantus Solostar | Insulin Glargine | 2000 | 2,663,360,232 | No* | 2011 |

| 10 | D | Jardiance | Empagliflozin | 2016 | 2,376,166,292 | Yes | 2023 |

| 11 | D | Humira(Cf) Pen | Adalimumab | 2002 | 2,169,430,424 | No* | 2009 |

| 12 | D | Ibrance | Palbociclib | 2017 | 2,108,937,188 | Yes | 2024 |

| 13 | D | Symbicort | Budesonide/Formoterol Fumarate | 2006 | 1,979,983,682 | Yes | 2013 |

| 14 | D | Xtandi | Enzalutamide | 2019 | 1,968,567,948 | Yes | 2026 |

| 15 | D | Novolog Flexpen | Insulin Aspart | 2000 | 1,844,084,368 | Yes | 2007 |

| 16 | D | Biktarvy | Bictegrav/Emtricit/Tenofov Ala | 2018 | 1,775,846,507 | Yes | 2025 |

| 17 | D | Myrbetriq | Mirabegron | 2012 | 1,749,232,347 | Yes | 2019 |

| 18 | B | Prolia | Denosumab | 2010 | $1,626,844,122 | Yes | 2021 |

| 19 | B | Opdivo | Nivolumab | 2014 | $1,586,591,103 | Yes | 2025 |

| 20 | D | Levemir Flextouch | Insulin Detemir | 2005 | 1,554,791,325 | Yes | 2012 |

| 21 | D | Victoza 3‐Pak | Liraglutide | 2010 | 1,545,815,415 | Yes | 2017 |

| 22 | D | Breo Ellipta | Fluticasone/Vilanterol | 2013 | 1,504,155,910 | Yes | 2020 |

| 23 | D | Trelegy Ellipta | Fluticasone/Umeclidin/Vilanter | 2020 | 1,487,802,308 | No | 2027 |

| 24 | D | Ozempic | Semaglutide | 2020 | 1,455,812,267 | No | 2027 |

| 25 | D | Pomalyst | Pomalidomide | 2013 | 1,453,860,767 | Yes | 2020 |

| 26 | D | Restasis | Cyclosporine | 2003 | 1,451,534,384 | Yes | 2010 |

| 27 | D | Ivega Sustenna | Paliperidone Palmitate | 2009 | 1,372,610,289 | Yes | 2016 |

| 28 | D | Enbrel Sureclick | Etanercept | 2003 | 1,371,059,068 | No | 2007 |

| 29 | D | Latuda | Lurasidone HCl | 2017 | 1,317,919,887 | Yes | 2024 |

| 30 | D | Jakafi | Ruxolitinib Phosphate | 2021 | 1,296,674,522 | No | 2028 |

| 31 | B | Rituxan | Rituximab | 1997 | $1,295,821,132 | Yes | 2008 |

| 32 | D | Tradjenta | Linagliptin | 2011 | 1,288,663,293 | Yes | 2018 |

| 33 | D | Humira Pen | Adalimumab | 2008 | 1,215,774,159 | No* | 2019 |

| 34 | D | Entresto | Sacubitril/Valsartan | 2015 | 1,203,043,540 | Yes | 2022 |

| 35 | D | Advair Diskus | Fluticasone Propion/Salmeterol | 2000 | 1,160,474,903 | Yes | 2007 |

| 36 | D | Ofev | Nintedanib Esylate | 2020 | 1,157,563,828 | No | 2027 |

| 37 | D | Spiriva | Tiotropium Bromide | 2004 | 1,153,453,863 | Yes | 2011 |

| 38 | D | Linzess | Linaclotide | 2012 | 1,144,468,128 | Yes | 2019 |

| 39 | B | Lucentis | Ranibizumab | 2006 | $1,113,026,179 | Yes | 2017 |

| 40 | D | Stelara | Ustekinumab | 2020 | 1,106,356,248 | No | 2027 |

| 41 | D | Lantus | Insulin Glargine | 2000 | 1,055,722,607 | No* | 2011 |

| 42 | D | Tecfidera | Dimethyl Fumarate | 2013 | 1,054,984,601 | Yes | 2020 |

| 43 | D | Humalog KPen U‐100 | Insulin Lispro | 2017 | 1,053,915,810 | Yes | 2024 |

| 44 | B | Orencia | Abatacept | 2005 | $1,023,001,524 | Yes | 2016 |

| 45 | D | Anoro Ellipta | Umeclidinium Brm/Vilanterol Tr | 2013 | 1,002,343,776 | Yes | 2020 |

| 46 | B | Neulasta | Pegfilgrastim | 2002 | $899,790,554 | Yes | 2013 |

| 47 | B | Darzalex | Daratumumab | 2015 | $837,400,701 | Yes | 2026 |

| 48 | B | Avastin | Bevacizumab | 2004 | $680,539,026 | No* | 2015 |

| 49 | B | Remicade | Infliximab | 1998 | $663,412,142 | No* | 2009 |

| 50 | B | Tecentriq | Atezolizumab | 2021 | $624,194,083 | Yes | 2032 |

| 51 | B | Ocrevus | Ocrelizumab | 2017 | $618,708,735 | Yes | 2028 |

| 52 | B | Soliris | Eculizumab | 2007 | $610,425,467 | Yes | 2018 |

| 53 | B | Cimzia | Certolizumab Pegol | 2008 | $508,504,399 | Yes | 2019 |

| 54 | B | Imfinzi | Durvalumab | 2017 | $505,845,757 | Yes | 2028 |

| 55 | B | Alimta | Pemetrexed Disodium | 2004 | $498,501,786 | Yes | 2015 |

| 56 | B | Herceptin | Trastuzumab | 1998 | $461,732,465 | No* | 2009 |

| 57 | B | Sandostatin Lar Depot | Octreotide Acetate, mi‐Spheres | 1998 | $445,226,506 | Yes | 2009 |

| 58 | B | Entyvio | Vedolizumab | 2014 | $434,481,708 | Yes | 2025 |

| 59 | B | Xolair | Omalizumab | 2013 | $399,757,988 | No* | 2024 |

| 60 | B | Gammagard Liquid | Immun Glob G(Igg)/Gly/Iga Ov50 | 2005 | $389,369,090 | Yes | 2016 |

| 61 | B | Gammaked | Immune Globulin G/Gly/Iga Avg 46 | 2005 | $385,877,482 | Yes | 2016 |

| 62 | B | Velcade | Bortezomib | 2003 | $381,241,268 | Yes | 2010 |

| 63 | B | Yervoy | Ipilimumab | 2011 | $365,961,395 | Yes | 2022 |

| 64 | B | Simponi Aria | Golimumab | 2009 | $359,631,479 | Yes | 2020 |

| 65 | B | Somatuline Depot | Lanreotide Acetate | 2007 | $340,276,002 | Yes | 2014 |

| 66 | B | Abraxane | Paclitaxel Protein‐Bound | 2005 | $339,486,064 | Yes | 2016 |

| 67 | B | Privigen | Immun Glob G(Igg)/Pro/Iga 0–50 | 2007 | $334,425,289 | Yes | 2018 |

| 68 | B | Botox | Onabotulinumtoxina | 2002 | $330,554,707 | Yes | 2013 |

| 69 | B | Perjeta | Pertuzumab | 2012 | $303,275,857 | Yes | 2023 |

| 70 | B | Stelara (J3357) | Ustekinumab | 2016 | $302,454,069 | Yes | 2027 |

| 71 | B | Kyprolis | Carfilzomib | 2016 | $293,472,937 | Yes | 2027 |

| 72 | B | Eligard | Leuprolide Acetate | 2004 | $285,196,045 | Yes | 2011 |

| 73 | B | Actemra | Tocilizumab | 2010 | $282,144,470 | Yes | 2021 |

| 74 | B | NPlate | Romiplostim | 2008 | $232,040,247 | Yes | 2015 |

Note: Eligibility for drugs in the first round in 2026 and biologicals first round in 2027. Asterisk entries are disqualified because of the presence of a generic or biosimilar or imminent before the first date of selection.

No biological product will enter price reduction for 5 years as most of them are Part B drugs unless they are dispensed directly to patients like adalimumab. The chemical drugs have a particular concession for up to 8 years, while the NCE exclusivity is only 5 years. Since the product selection does not mandate that products from Part B must be chosen—it is all rank ordered, the likelihood of selecting biological products remains remote (Table 2). The products listed in Table 2 should be the imminent choice for biosimilar developers.

The total number of products with price reduction will increase by a fixed number per year, but the total number of price‐controlled products will decrease as there is no replacement for those removed from the list if they are no longer single‐source products. As a result, this list may stay short forever, hailing the entry of generics and biosimilars.

The inclusion criteria for products subject to price negotiation include a single source drug or under Medicare Part B and D:

In addition, having the highest expenditures for a given year, manufactured by a single source, for example, a company making both brand name and generic or biosimilar, will count as one.

Approved or licensed (as applicable) under section 505(j) or section 351(a), and it is not listed as the reference product for a 351(k) product or application.

Drugs or biologics have been on the market for at least 7 years for branded drugs or 11 years for biologics. It is noteworthy that the exclusivity of a new chemical entity is 5 years. 21 The biological drugs have a 12‐year exclusivity. 22 Two years are added if requested if a generic or biosimilar product is expected to be registered within 2 years. If a biosimilar is not approved within 2 years, the reference product will have to pay rebates from the date of selection listing. These rebates are likely lower than the negotiated price difference, giving the reference product manufacturer to invoke this exclusivity, even if a biosimilar entry is not imminent.

Among the 50 qualifying products with the highest total expenditures during the most recent 12‐month period.

- The exclusion criteria for products subject to price negotiation include:

- Biologicals are named reference products for a product approved or under approval in the 351(k) filing.

- Change status due to entry until a generic or biosimilar enters the market. This exclusion applies to a biological that is an extended‐monopoly drug approved for 12 and 16 years; this is an automatic classification since biological products have 12‐year exclusivity; the negotiations begin past 11 years.

- Small biotech drugs. Expenditure is less than 1% of Medicare Part D or B spending. Therefore, the maximum fair price (MFP) negotiated may not be less than 66% of the average non‐Federal average manufacturer price (AMP) for 2021. In addition, for the minor volume biotech drugs, the MFP is not subject to an MFP less than 34% off the non‐FAMP.

- Drugs of a manufacturer acquired by a certain manufacturer after 2021.

- Orphan drugs for only one rare disease or condition for which there is only one indication.

- Drugs or biologicals with Part B and D spend less than $200,000,000 per year (increased annually by inflation).

- Plasma‐derived products.

- Products of the manufacturer are acquired after 2021 by another manufacturer or, in the case of an acquisition, before 2025.

- New formulations include extended‐release, higher concentration and change of route of administration of a qualifying drug.

- Drugs for a single rare disease or condition.

- Drug or biological product that is a selected drug in special Social Security Plan for which 106% of the MFP will be applicable for such drug and a year during such period.

- If the drug or biological constitutes 80% of the manufacturer's revenue and expenditure is not more than 1% of the total Part B or Part D, as the case may be.

- Part B reimbursement for a selected drug is not average sales price (ASP) plus 6%, but the maximum price plus 6%.

- Renegotiation.

- Renegotiation is mandatory if selected drug graduates to extended‐monopoly have 75% market for at least 11 years but less than 16 years; long‐monopoly drugs have 65% market for 16 years or more. Standard monopoly drugs have a 40% market. It excludes vaccines.

- If a selected drug receives a new indication or there is a material change in the factors considered by the Secretary in setting the initial negotiated price.

- A selected drug's negotiated price (or as renegotiated when applicable) will remain in place until a generic or biosimilar is launched, in which case the selected drug's MFP would terminate at the start of the first year that begins 9 months after the generic or biosimilar has entered the market.

- The MFP is based on:

- The statute includes specific minimum discounts based on categories of products to serve as a ceiling to the MFP, which is the lesser of: (1) 25% of the non‐federal AMP for short‐monopoly drugs, 35% off the non‐federal AMP for extended monopoly drugs, and 60%of the non‐federal AMP for long‐monopoly drugs; or (2) the sum of the plan‐specific enrolment weighted amounts (for Part D selected drugs), or the drug's Part B payment amount for the year before the year of the selected drug publication date concerning the initial price applicability year for the drug or biological product (for Part B selected drugs).

Research and development costs;

Current unit costs of production and distribution of the drug;

Prior Federal financial support for novel therapeutic discovery and development;

Data on pending and approved patent applications, exclusivities recognized by the FDA, and applications and approvals under sections 505(c) or 351(a);

Market data and revenue and sales volume data for the drug in the United States; The extent to which such drug represents a therapeutic advance as compared with existing therapeutic alternatives and the costs of such existing therapeutic alternatives; comparative clinical effectiveness research evidence that treats extending the life of an elderly, disabled or terminally ill individual as of lower value than extending the life of an individual who is younger, nondisabled or not terminally ill.

4. PRESCRIPTION DRUG INFLATION REBATES

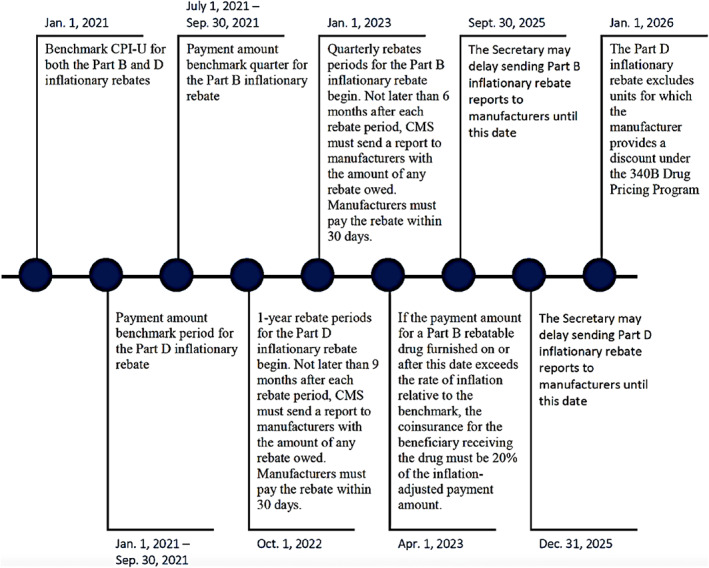

The Act requires manufacturers to pay rebates for certain drugs under Medicare Parts B or D if their average prices increase faster than inflation. (Figure 2). Beginning on 1 January 2023, the Part B inflationary rebate applies to single‐source drugs and biologicals (including biosimilars) for which payment is made under Medicare Part B. Drugs and biologicals excluded from the inflationary rebate include those with annual price changes of less than $100 per individual, certain specified Part B vaccines, and qualifying biosimilar biological products with ASPs that do not exceed the reference biological's ASP during the quarter for 5 years. Part B inflationary rebates may also be waived or reduced in the case of drug shortages and severe supply chain disruptions.

FIGURE 2.

Timeline: Medicare Parts B and D Drug Inflationary Rebates 23

Exclusion includes qualifying biosimilars within 5 years—a biosimilar with an ASP for the quarter that is not greater than the ASP for the reference drug.

5. ENFORCEMENT

Manufacturers that do not agree to an MFP with HHS will be subject to a tax of 65%–95% of Medicare utilization based on the prior year. In addition, manufacturers that agree on an MFP, but do not honour it, will be subject to civil monetary penalties equal to 10 times the amount of the product dispensed or administered that year, as well as the difference between the reimbursed price and the MFP.

Manufacturers will be subject to civil monetary penalties of 125% of the rebate amounts for untimely payments.

The Act precludes administrative and judicial review of the Secretary's selection of drugs subject to the Program, determining MFPs, and choosing renegotiation‐eligible drugs.

6. SUMMARY

The US legislative system is complex and not ideal and thus subject to criticism, the IRA being no exception. The same happened with the Affordable Healthcare Act 24 that quietly embedded in the BPCIA 25 to allow entry of biosimilars. The BPCIA had been on the table at the Senate for a decade; when it became part of a much larger Bill, many deniers did not even pay attention to it and signed off without realizing that it had only 7 years of exclusivity for biological products. An uproar post‐approval made President Obama concede to 12 years of exclusivity.

The IRA is similar to the AHA in many ways. While bringing extreme comfort to Medicare patients by removing the famous “donut hole,” it capped the cost for the elderly. It also brought support to the direly needed environmental control. Unfortunately, the cost of $780 billion had to be paid somehow. The Act added a minimum tax of 15% on corporations and taxed the purchase of own equity by the companies. However, it does not force additional tax and removes the already unavailable clause that is already not available to individuals.

The IRA does not restrict the pricing of biosimilars as commonly practiced in the EU. 26 A reference product selected towards the end of the exclusivity period will likely be subject to a 35% price reduction since it will be considered an extended monopoly drug, notwithstanding other considerations that might reduce this margin. This is not a “precipitous” drop in the price that a biosimilar could not match. But that scenario does not even arrive since the approval of a biosimilar removes this price reduction. If the reference product decides to keep the lower price, this has little to do with the IRS, and it is market play.

The IRA only applies to Medicare, and the price negotiation applies only to chemical drugs after 7 years of market monopoly and the past 11 years to biological drugs when the negotiations begin. Two additional years are added if the arrival of a generic or biosimilar is imminent.

Over a decade, there will be about 10 drugs put into price reduction out of 14,000 that the CMS reimburses. The cumulative number will keep reducing as generics and biosimilars are approved. The Act will reduce the cost of drugs to 63 million patients on Medicare and 3.5 million on Medicaid, 27 compared with 177 million patients receiving drugs through private insurance. 28 The negotiated price will benefit everyone if it spills over to the private market.

The argument is fallacious; if the price of brand name products is reduced, it will reduce the incentive for generics and biosimilars to enter the market. The entry of biosimilars will remove the price reduction, incentivizing reference product manufacturers to encourage biosimilars entry. If the reference product manufacturer decides to keep its price lower after the restrictions are removed, this can happen to any drug and has little to do with the IRA.

Medicare Part B reimbursement for biosimilars will be temporarily increased to ASP +8% (8% is calculated on the ASP of the reference product) for 5 years. For biosimilars currently on the market, the increase will be effective through 31 December 2027. In addition, new biosimilars launched before 31 December 2027, will experience a temporary increase in reimbursement from their launch date to the end of the 5 years. Biosimilars launched after 31 December 2027, will be reimbursed as ASP +6% (6% is calculated on the ASP of the reference product). This is a benefit included in the IRA.

The IRA not only reduces the burden of the CMS by $100 billion; it also reduces the cost burden of millions of patients, improves the environment and holds corporations responsible for their contribution to the welfare of society. The clear beneficiaries are the 60+ million Americans who will no longer have to deal with the notorious “donut hole” and now have a ceiling of $2000 for their Part D and B contribution.

As the list of price‐negotiated drugs shrinks over time, the Medicare saving will shift from reimbursing the reference product to the biosimilar, as it is doing now. So, in essence, the entire purpose of the price‐reduction exercise is to prompt the entry of generics and biosimilars.

The proposition of negotiating the price is not new or uncommon; more than half of the EU countries now fix the pricing with a tender system, and others require significant price reductions for biosimilars. 26 The IRA is much less aggressive than it was supposed to be; it is based on fairness that chooses biological drugs after 11 years of marketing and 7 years for chemical drugs, regardless of the patent status. This period should be enough to secure a profitable return on the investment when we look at the prices charged by the reference product companies. For example, according to WHO, 29 the cost of producing an antibody ranges from $95 to 150 per gram; these are sold at 100–1000 times the COGs during the exclusivity periods. There is enough allowance for the reference product to recoup its billion‐dollar investment. This is the same argument offered in patent rights; when a patent expires, humanity should be able to benefit.

The drug negotiation provisions of the IRA do not extend to the private market. However, the negotiation agreement requires manufacturers to make the MFP available to MFP‐eligible individuals who are enrolled in a prescription drug plan under either Part C or D and are dispensed a selected drug, but also those who are furnished or administered a selected drug for which payment is made under Part B. However, there is no penalty if offering MFP to an individual who is not an MFP‐eligible individual.

While the IRA pertains only to Medicare, the inflation rebates based on Medicare utilization could have spillover effects in other market segments. However, it is not likely to happen since there is already in place a rebate program managed by the Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently began an inquiry into how these drug rebates block patient access to cheaper pharmaceuticals. 30 The FTC has charged that rebates could be driving up prices of vital drugs such as insulin, the list price of which has increased by more than 300% in recent decades. The “exclusionary” rebates cut off competition from a less expensive alternative like a generic or a biosimilar. The PBMs, as the “drug middlemen,” have placed higher‐priced drugs on formularies instead of “lower‐cost alternatives” in a manner that shifts costs to payers and patients. In addition to other factors, some have suggested that high rebates and fees to PBMs and other intermediaries may incentivize higher list prices for drugs and discourage coverage of the lowest‐cost products.

A new Senate bill aims to empower FTC to crack down on PBMs. 31

Major supporters of IRA include the Commonwealth Fund, 32 The American Pharmaceutical Association, 33 which also pointed out the need to fix the PBM's role in drug distribution. Surprisingly, the opponents of the IRA are going to be the biggest beneficiary, the associations representing the generic and biosimilar industry, 34 as well as the big pharma groups like the BIO, while accepting it as good news for agricultural biotechnology. 35 While many scholars and leaders support the Bill, many have opposed it due mainly to their misconceptions and misunderstanding of the Bill, as explained below.

7. MISCONCEPTIONS AND MISUNDERSTANDINGS

The statements and pleadings made by prominent scholars and heads of associations responsible for promoting generics and biosimilars are presented below, along with a detailed explanation to remove these misconceptions and misunderstandings. The numerical parenthesis is added to focus on the underlined comments.

Association for Affordable Medicines 36 states: “Senate has chosen to replace competition – the only proven way to provide patients relief from high brand drug prices – with a flawed framework for (1) government price setting that will (2) chill the development of, and (3) reduce patient access to, lower‐cost generic and biosimilar medicines . While the bill's ill‐advised price setting scheme (4) will harm Medicare and seniors, its negative impact will (5) extend to employers and patients that rely on generic and biosimilar medicines to keep costs down.” Dan Leonard, President & Chief Executive Office, Association for Accessible Medicines [parentheses added]

(1) There is no “price setting”; it is a price reduction of about 25% for chemical drugs after 8 years and 35% for biological drugs after 12 years of monopoly, provided no generic or biosimilars become available.

(2) This statement is incorrect and misleading. 37 The correct number is 15 out of 1300, 38 or about 1%, over 20 year period, assuming that no biosimilar or the generic product arrives and the price reduction of the single‐source product stays at 65% after 16 years of exclusivity. All the while, the CMS had saved over $2–3 trillion. A major misunderstanding comes from thinking that once a reference product has been subjected to price‐reduction, it will remain so; chances are that most of product brought into price negotiation will soon leave the classification, significantly reducing the number of products in this category. Products removed are not replaced by additional products, except 20 per year; faster removal of drugs from price negotiation may leave the number of such drugs to no more than those selected each year.

(3) The entry of 15 fewer drugs over 20 year period applies to new chemical or biological drugs; it has no impact on the affordable generics and biosimilars. If it is asserted that the price reduction of single‐source products will hamper the entry of generics and biosimilars is welcomed, the single‐source product is faced with price reduction.

(4) It is impossible to give credence to this statement; how would Medicare patients and seniors suffer? They are even getting a cap on their out‐of‐pocket expense, the “donut hole” is leaving, and no change will come to their medical supplies. They will receive their reimbursement as before; only private patients might see a difference, which is in their favour with the lowered cost of single‐source drugs.

(5) How could there be a negative impact on employers and patients? If it refers to employers paying for insurance, it will reduce the burden, not increase, if the price spillover comes to the private market. If the employers are referred to generic and biosimilar companies, they are here to get the biggest benefits.

Robert E. Moffit, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, Center for Health and Welfare Policy, 39 has also stated: “(6) the so‐called Medicare prescription drug ‘negotiation’ plan has nothing to do with negotiation and everything to do with government price setting. For the record, when CBO issued its 2021 report on the impact of the Lower Drug Costs Now Act, last year's Democratic congressional proposal, it concluded that that bill, (7) if enacted, would have ‘reduced global revenue for new drugs by 19 percent’, resulting in the 30 fewer drugs over a 20‐year period .”

(6) The price reduction applies only to a single‐source drug, whether a brand‐name drug, generic or biosimilar, and if their expenditure is the highest, likely above $1B per year; the reduced price goes away once the product is no longer a single‐source product.

(7) This is also misrepresenting the data from the CBO, as shown above.

Biosimilars Council: 40 states: “Contrary to its name, the Inflation Reduction Act would increase prescription costs by (8) stifling biosimilar competition and innovation,” said Craig Burton, Executive Director of the Biosimilars Council. “The price control proposals would actively (9) harm millions of patients by rewarding brand drug manufacturers with a perpetual monopoly . Congress should reject this proposal and support solutions that sustainably lower drug prices by (10) encouraging generic and biosimilar adoption .”

(8) Biosimilar competition is fostered by the IRA as it makes the entry of biosimilars a condition to remove the price reduction of the reference product. There is no impact on innovation as these products will have exclusivity. If the intent is to state that the price reduction will reduce the entry of new drugs, then it is the same misconceived statement discussed above.

(9) There is no monopoly awarded; it is instead punished. For example, when a biosimilar product comes out of exclusivity, the price reduction will be 35%, and if no competitor arrives until 16 years, the price reduction goes to 65%. Suppose the statement intends that the price reduction of a single‐source product will deter the entry of generics and biosimilars. In that case, the statement is misconceived since the price cap for reference products goes away once a generic or biosimilar enters the market.

(10) No legislation or effort has done more to promote generics and biosimilars than the IRA. It is straightforward. Unless a generic or biosimilar is available, the brand name product must sell at a lower price. Can there be a better incentive for generic and biosimilar industries?

Craig Burton 41 responding to the opinion of the author 42 : “… threatens to undermine (11) biosimilar competition by creating unprecedented price controls. In addition, this misguided provision could (12) compromise future biosimilar development and inadvertently leave patients with costlier brand‐name treatment options .”

(11) Since there has never been a price control, there cannot be a precedence. The reference product manufacturer will prefer to have biosimilars enter the market to remove their price reduction after their exclusivity period. Medicare is already reimbursing all licensed biosimilars and waiting to remove the reimbursement of reference products once the biosimilars arrive.

(12) On the contrary, it will speed up the entry of biosimilars; if the intent is to say that since there are price reductions for a single‐source product, no competition will arrive even though its arrival removes the price reduction, then this is entirely unrealistic. Furthermore, to assume that the costlier brand‐name products with a 65% reduction will stay expensive and continue to sell is also misleading. If the brand‐name product decides to keep its price lower of its own volition, then the assumption that a biosimilar product cannot sell at less than the price of the brand‐name product it should be in the market.

“(13) If the reference biologic is selected for negotiations near the end of its exclusivity period, its product's price will (14) drop precipitously. This would then require the biosimilar competitors to price themselves (15) even lower than the point of economic viability and out of the market entirely.”

(13) There is no “if,” all products will be selected at the end of their exclusivity.

(14) A 35% reduction in price after 12 years of exclusivity of biological drugs and 25% price reduction of single‐source chemical drug after 8 years is not “precipitous.”

(15) This statement has two misconceptions. First, a biosimilar product cannot sell at a price lower than the reference product; second, a 35% price reduction will make biosimilar unviable. Most biosimilars sell at much more than 35% and remain economically viable.

“significantly reduce the competitive edge (16) just as the market considers which potential competitors to bring to market.”

(16) The choice of competitors shall remain the same; the highest value products are most likely to be selected for the price reduction. The CMS listing of spending is an open database that anyone can use to determine which drug or biological product will be subject to price negotiation (see Tables 2, 3, 4).

TABLE 3.

Biosimilar candidates as Part B reimbursed biologicals (biosimilars in bold) with only one drug (*) with $1B+ expenditure

| *Abatacept | Abobotulinumtoxina | Ado‐Trastuzumab Emtansine | *Aflibercept | Agalsidase Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin Human | Alemtuzumab | Alglucosidase Alfa | Alpha‐1‐Proteinase Inhibitor | Alteplase |

| Anti‐Inhibitor Coagulant Comp. | Anti‐Thymocyte Globulin, rabbit | Antihem. FVIII, several types | Antihemophilic Factor/VWF | Antithrombin III (Hum Plas) |

| Antivenin, crotalidae Fab(Ovin) | Asparaginase (Erwinia Chrysan) | Atezolizumab | Avelumab | Basiliximab |

| Belatacept | Belimumab | Bendamustine HCL | Benralizumab | Bevacizumab |

| Bezlotoxumab | Blinatumomab | Bortezomib | Brentuximab Vedotin | Brolucizumab‐Dbll |

| Burosumab‐Twza | C1 Esterase Inhibitor, Recomb | Canakinumab/PF | Carfilzomib | Cemiplimab‐Rwlc |

| Certolizumab Pegol | Cetuximab | Chorionic Gonadotropin, Human | Coagulation Factor VIIA, recomb | Coagulation Factor X |

| Crizanlizumab‐Tmca | Daratumumab | Darbepoetin Alfa In Polysorbat | *Denosumab | Digoxin Immune Fab |

| Dornase Alfa | Durvalumab | Eculizumab | Elotuzumab | Emicizumab‐Kxwh |

| Enfortumab Vedotin‐Ejfv | Epoetin Alfa | Factors IX several types | Factor XIII several types | Fam‐Trastuzumab Deruxtecn‐Nxki |

| Filgrastim | Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin | Glucagon, human Recombinant | Golimumab | Ibalizumab‐Uiyk |

| Idursulfase | Imiglucerase | Imm Glob G (Igg)/Sorb/Iga 0–50 | Incobotulinumtoxina | Infliximab |

| Inotuzumab Ozogamicin | Insulin Aspart | Insulin Lispro | Interferon Alfa‐2b, recomb. | Interferon Beta‐1a |

| Ipilimumab | Isatuximab‐Irfc | Mepolizumab | Methoxy Peg‐Epoetin Beta | Mogamulizumab‐Kpkc |

| Moxetumomab Pasudotox‐Tdfk | Natalizumab | Necitumumab | *Nivolumab | Obinutuzumab |

| Ocrelizumab | Ocriplasmin/PF | Ofatumumab | Olaratumab | Omalizumab |

| Onabotulinumtoxina | Panitumumab | Pegaspargase | Pegfilgrastim | Pegloticase |

| *Pembrolizumab | Pertuzumab | Polatuzumab Vedotin‐Piiq | Ramucirumab | *Ranibizumab |

| Ravulizumab‐Cwvz | Reslizumab | Rho(D) Immune Globulin | Rimabotulinumtoxinb | *Rituximab |

| Rituximab/Hyaluronidase, human | Romosozumab‐Aqqg | Sargramostim | Siltuximab | Tagraxofusp‐Erzs |

| Taliglucerase Alfa | Teprotumumab‐Trbw | Thyrotropin Alfa | Tildrakizumab‐Asmn | Tocilizumab |

| Trastuzumab | Trastuzumab‐Hyaluronidase‐Oysk | Treprostinil | Ustekinumab | Vedolizumab |

| Velaglucerase Alfa | Von Willebrand Factor | Ziv‐Aflibercept |

Note: Adalimumab is classified under Part D.

TABLE 4.

Top market‐share biosimilar opportunities

| Product | Category | Global ($B) Market, 2025 | Biosimilar approval US/EU; *interchangeable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythropoietin (Epoetin), Amgen | Haematopoietic | 18 | 1/3 |

| Pembrolizumab (Keytruda), Merck | HER2 | 16 | 0/0 |

| Nivolumab (Opdivo), BMS | PD‐1 | 14 | 0/0 |

| Adalimumab (Humira) AbbVie | TNF‐alfa | 11 | 7/10 |

| Etanercept (Enbrel), Amgen | TNF‐alfa | 8 | 2/3 |

| Infliximab (Remicade), Janssen | TNF‐alfa | 8 | 4/4 |

| Ustekinumab (Stelara), Janssen | IL‐12, IL‐23 | 8 | 0/0 |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin), Roche | VEGF‐A | 7 | 3*/9 |

| Ocrelizumab (Ocrevis), Genentech | CD‐20 | 7 | 0/0 |

| Pertuzumab (Perjeta), Roche | HER‐2 | 7 | 0/0 |

| Secukinumab (Cosentyx), Novartis | PD‐1 | 6 | 0/0 |

| Aflibercept (Eyelea), Regeneron | VEGF | 4 | 0/0 |

| Darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp), Amgen | Haematopoietic | 4 | 0/0 |

| Peg‐filgrastim (Neulasta), Amgen | Neutropenic | 4 | 5/7 |

| Ranibizumab (Lucentis), Novartis | VEGF | 4 | 2*/1 |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin), Genentech | HER‐2/neu | 4 | 5/6 |

| Rituximab (Rituxan), Genentech | CD‐20 | 3 | 3/5 |

| Cetuximab (Erbitux), Lilly/Merck | EGF | 1 | 0/0 |

| Eculizumab (Soliris), Alexion | Complement C5 | 1 | 0/0 |

| Filgrastim (Neupogen), Amgen | Neutropenic | 1 | 3/9 |

“Biosimilar manufacturers have (17) no role in the negotiation process and would instead have to (18) gamble on whether or not a reference biologic becomes 1 of the 100 negotiated drugs.”

(17) Negotiations are held with the product manufacturer; if a biosimilar is a one‐source product (say, if the innovator leaves the market), then it will be subject to a price reduction as well if it spends on it more than a billion dollars. So why would they be part of any negotiation for another product?

(18) It will be 2033 when the total number of drugs negotiated will reach 100. Given that only the top 50 drugs in Part D and B are eligible for price negotiation with no preference for Plan D or B, it is improbable that any biological product will be added to the list (see Tables 2, 3, 4). The total count of price‐reduced drugs will likely be no larger than 20, the newly introduced drugs for the year as the entry of generics and biosimilars for these lufratige market drugs will reduce the count of single‐source products.

“(19) …too risky for would‐be biosimilar manufacturers to invest the decades and hundreds of millions of dollars required to produce lower‐cost alternatives. This would (20) give costly brand‐name medicines a de facto monopoly at a price likely higher than what patients would have paid in (21) a traditionally functioning market with multiple biosimilar competitors.”

(19) Unlike chemical drugs, biologicals have almost perpetual life; one of the earliest products, erythropoietin, is now projected to become the #1 product in 2025 (Table 4). The only risk to biosimilars is the competition from other biosimilars, and if that is the case, then it is a business decision with little to do with the IRA.

(20) De facto monopoly assumes that the reference product stays the single‐source product after its exclusivity expires. The price will be reduced eventually by 65%, but all of it applies to Medicare, not the private market. Not realized here is that the price reduction plan penalizes monopoly.

(21) Nothing in the IRA impacts the market, it only reduces the price of a few drugs reimbursed by Medicare. 80% of the private market is not included in the IRA. If there is any impact on the private market, it will be positive, not negative.

(22) “ Biologic brands often file non‐innovative patents that, in this case, would delay biosimilars past the point of the negotiation window – effectively rendering this safeguard provision useless.”

(22) The IRA motivates reference product manufacturers to let go of the Patent Dance and let the biosimilars arrive sooner, so they may not be subject to price negotiation. It will expedite, not delay, the entry of biosimilars. It is time for first‐time biosimilar entries to work with reference product manufacturers to reduce the cost burden of patent litigation—it is an unprecedented opportunity.

(23) “Under the bill, the Department of Health and Human Services would be required to negotiate prices for over 100 drugs—many of which would be reference biologics subject to biosimilar competition.”

(23) It will take a decade before 100 out of 14,000 drugs are put to price negotiation and only those that make the top 50 list of Medicare expenditure. No reference biological product qualifies for at least a decade (Table 2). Given the historical difference in the expenditure between Plan D and Plan B drugs, it is improbable that any biological product will ever be subject to price negotiation. The cumulative number will remain very small as most of the drugs in the price‐control category will be removed with the arrival of generics and biosimialrs.

“(24) Essentially, biosimilars are forced to accept the outcome of the negotiation process, and they would be in no position to establish any incentives for themselves.”

(24) This statement conjectures that the biosimilars will sell at a lower price than the reduced price of the reference product, even if there is no reduced price.

“(25) What's ironic about the Inflation Reduction Act is that artificially setting prices ignores the proven benefits of competition established by the Hatch‐Waxman Act. Further, (26) it bypasses bipartisan legislative solutions that would nurture future competition and sustainably lower prices.”

(25) There is no arbitrary price setting; a biological product that has passed beyond its 12‐year exclusivity will be subject to a 35% price reduction or less if it qualifies for many circumstantial waivers. The BPCIA has done what the Hatch‐Waxman Act did to chemical drugs. Both the BPCIA and the IRA operate with no price controls.

(26) This statement may be showing the slip. The IRA was rejected by 100% of Republicans in both the Senate and the House. Dreamers can think of a bipartisan resolution to anything in America. The IRA has many humanitarian and environmental benefits besides the budget reduction of Medicare. But none of these were countable when the decision came to partisanship.

Amitabh Chandra, 43 director of health policy research at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, stated: “there could also be ‘strong incentives’ for the brand manufacturer to (27) introduce its biosimilar and forestall negotiations through this channel.”

(27) The IRA already prevents such practice. The imminent biosimilar cannot be owned directly or indirectly by the reference product company, or if the product company incentivizes the biosimilar developer, that is defined under the Aggregation Rule. The IRA further prohibits tactics from using biosimilar entries to remove the reference production selection for price negotiation. The statement is misconceived.

8. PERSPECTIVE

The future of biosimilars depends on the efficiency of their development cost, enabling the offering of affordable products. 44 However, the current $100–300 million price for each biosimilar is untenable. 45 Therefore, the onus to reduce the development cost lies as much on the developers 46 and the regulatory agencies. 47 The associations representing generic and biosimilar companies should focus on achieving this goal instead of politicizing the efforts intended to help the generic and biosimilar industry if they disagree with the legislature due to their partisan views.

The US FDA has approved more than 130 recombinant proteins for clinical use. However, and more than 170 recombinant proteins are available. 48 Yet, only nine molecules in the US and 14 in the EU are available as biosimilars. The opportunities for biosimilars are boundless (Table 3).

The IRA's impact on biosimilars will help bring more biosimilars sooner and reduce legal hurdles like the “patent dance.” In addition, the IRA offers many concessions to biosimilars.

The developers and promoters of biosimilars should realize that eventually, the biosimilars will become fully adopted when the price drops by 60%–70%, regardless of the current efforts to change the opinions of prescribers, patients and other stakeholders. Once the payors come into play, biosimilars will turn no different than generics.

Table 3 lists the biological drugs reimbursed under Plan B, all of which make an excellent choice for the biosimilar developers to choose from since these have an established market through Medicare.

Table 4 lists the biosimilar candidates with the anticipated market of over $135B in 2025. None of these would be subject to price reduction, including the 10 single‐source products for which the arrival of biosimilars. In addition, none of these drugs are likely to make it to the top 15–20 drugs in expenditure to be selected.

Significant changes coming to the regulatory guidelines will reduce the burden of testing as the analytical assessment becomes more sophisticated and reliable. For example, the FDA has recently funded a grant of $2 million 49 to create strategies to reduce the testing burden to establish biosimilarity. In addition, the MHRA 50 has already declared that animal testing 51 and comparative efficacy testing may not be required, 52 as suggested by the author.

9. CONCLUSION

The IRA is the law now; there is no perfect law, but it can be made perfect by those who choose to practice it diligently. The law relating to drug price reduction applies only to Medicare, which serves 20% of patients; it has little to do with the 80% of the private market. The IRA does not control (meaning capping) the price of drugs; it forces the reduction of specific products that meet limited criteria of the highest expenditure to Medicare and time on the market as a single‐source product. The price reduction is 25% for generics and 35% for biologics when they become eligible for a price reduction; staying as a single source beyond 16 years will increase the reduction to 65%; thus, the IRA promotes the generic and biosimilar industry to remove the single‐source status of drugs.

Any projections of impact on the industry, the patients and other stakeholders based on the number of price‐reduced single‐source products are overblown, not realizing that most of these products will be removed and replaced with other products; it should not surprise if the total number is not more than 10–20, the first entrants, throughout the life of the practice of the IRA.

Associations promoting generics and biosimilars need to rethink their opposition to IRA; the challenge is the high development cost, not the temporary price reduction of the reference product that will positively impact generics and biosimilars. They should work to educate the developers and the regulatory agencies 47 instead of focusing on advertising the value of generics and biosimilars. The FDA has already approved them. Once the cost of goods goes down, the biosimilars, as do the generics, will become adopted, forced by the payors. A significant hurdle in the accessibility of affordable biosimilars is the presence of PBMs. 53 Getting out of this trap alone can reduce the cost of all drugs by 50%.

Despite the partisan politics, the generics and biosimilars have a great future, now brightened by the IRA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author has served as an advisor to Vice President Kamala Harris on drafting the IRA. The author is also a US patent law practitioner.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this article are entirely author's and do not necessarily represent any institution, association, or company.

Niazi SK. The Inflation Reduction Act: A boon for the generic and biosimilar industry. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(11):1738‐1751. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13783

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/24/us/medicare-debate-turns-to-pricing-of-drug-benefits.html

- 2. The Inflation Reduction Act . https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22inflation+reduction+act%22%2C%22inflation%22%2C%22reduction%22%2C%22act%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1

- 3. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/inflation_reduction_act_one_page_summary.pdf

- 4. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/15/by-the-numbers-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- 5. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58366

- 6. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet

- 7. https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm

- 8. https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2022/07/how‐does‐the‐us‐healthcare‐system‐compare‐to‐other‐countries?utm_term=per%20capita%20healthcare%20spending%20by%20country&utm_campaign=Healthcare+General&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc

- 9. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart‐collection/how‐do‐prescription‐drug‐costs‐in‐the‐united‐states‐compare‐to‐other‐countries/#Per%20capita%20prescribed%20medicine%20spending%20U.S.%20dollars%202004‐2019g

- 10. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-98/pdf/STATUTE-98-Pg1585.pdf

- 11. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2021-annual-report

- 12. Wouters OJ, McKee M, Luyten J. Estimated Research and Development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market 2009‐2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):844‐853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/where-drugs-come-country

- 14. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/canada‐not‐a‐good‐example‐of‐universal‐health‐care#:~:text=The%20reality%20of%20Canadian%20health,any%20country%20should%20consider%20replicating.

- 15. https://www.nationalreview.com/2021/01/the-deadly-failures-of-britains-national-health-service/

- 16. https://www.healthcare.gov/where-can-i-read-the-affordable-care-act/

- 17. https://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Statistics‐Trends‐and‐Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE‐Fact‐Sheet#:~:text=Historical%20NHE%2C%202020%3A&text=Medicaid%20spending%20grew%209.2%25%20to,9%20percent%20of%20total%20NHE.

- 18. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-the-medicare-part-d-prescription-drug-benefit/

- 19. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue‐brief/relatively‐few‐drugs‐account‐for‐a‐large‐share‐of‐medicare‐prescription‐drug‐spending/#:~:text=Part%20B%20covers%20a%20substantially,drugs%20are%20relatively%20costly%20medicationsy.

- 20. https://data.cms.gov/summary‐statistics‐on‐use‐and‐payments/medicare‐medicaid‐spending‐by‐drug/medicare‐part‐d‐spending‐by‐drug/data

- 21. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development‐approval‐process‐drugs/frequently‐asked‐questions‐patents‐and‐exclusivity#What_is_the_difference_between_patents_a

- 22. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/background-information-list-licensed-biological-products-reference-product-exclusivity-and

- 23. https://foleyhoag.com/-/media/files/foley%20hoag/publications/white%20papers/foley%20hoag%20llp%20-%20summary%20of%20inflation%20reduction%20act%20of%202022%20-%20key%20drug%20pricing%20provisions%20and%20implementation%20timeline.ashx?la=en

- 24. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/3590

- 25. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1428/text

- 26. Vogler S, Schneider P, Zuba M, Busse R, Panteli D. Policies to encourage the use of biosimilars in European countries and their potential impact on pharmaceutical expenditure. Front Pharmacol. 2021;25(12):625296. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.625296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/news‐alert/cms‐releases‐latest‐enrollment‐figures‐medicare‐medicaid‐and‐childrens‐health‐insurance‐program‐chip#:~:text=As%20of%20October%202021%2C%20the%20total%20Medicare%20enrollment%20is%2063%2C964%2C675.

- 28. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10830.pdf

- 29. WHO . Call for consultant on monoclonal antibodies for infectious diseases. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/call-for-consultant-on-monoclonal-antibodies-for-infectious-diseases.

- 30. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payers/ftc‐puts‐pbms‐notice‐enforcement‐policy‐surrounding‐drug‐rebates

- 31. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payers/senate-bill-aims-ban-pbm-practices-such-spread-pricing-and-boost-ftc-enforcement-powers

- 32. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/apr/lower-drug-costs-now-act-hr3-how-it-would-work

- 33. https://www.pharmacist.com/APhA‐Press‐Releases/apha‐reminds‐policymakers‐to‐fix‐broken‐pbm‐marketplace‐to‐compliment‐new‐drug‐pricing‐law

- 34. https://khn.org/news/article/big‐pharma‐oppose‐drug‐pricing‐negotiations‐history/

- 35. https://www.bio.org/gooddaybio‐archive/good‐day‐bio‐inflation‐reduction‐act‐and‐ag‐biotech

- 36. https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/aam-statement-senate-passage-inflation-reduction-act

- 37. Cookson G, Hitch J. Limitations of CBO's simulation model of new drug development as a tool for policymakers. OHE Consulting Report; 2021. https://www.ohe.org/publications/limitations-cbo%E2%80%99s-simulation.

- 38. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-07/senSubtitle1_Finance.pdf

- 39. https://www.heritage.org/medicare/commentary/reducing-patient-access-new-medications-the-lefts-latest-medicare-price-fixing

- 40. https://biosimilarscouncil.org/news/inflation-reduction-act-would-stifle-biosimilar-competition-and-savings/

- 41. Burton C. Opinion: the Inflation Reduction Act is a step backward for biosimilar competition. August 18, 2022. https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/opinion‐the‐inflation‐reduction‐act‐is‐a‐step‐backward‐for‐biosimilar‐competition

- 42. Niazi S. Impact of Inflation Reduction Act 2022; Addressing Critics. https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/opinion-impact-of-inflation-reduction-act-2022-addressing-critics

- 43. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/drug-negotiations-will-drive-biosimilars-as-patent-tactics-shift

- 44. Niazi SK. The coming of age of biosimilars: a personal perspective. Biol Theory. 2022;2(2):107‐127. doi: 10.3390/biologics2020009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen Y, Monnard A, Jorge Santos DS. An inflection point for biosimilars, McKinsey & Co. June 8 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/an-inflection-point-for-biosimilars.

- 46. Niazi S. Biosimilars: a futuristic fast‐to‐market advice to developers. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(2):1‐7. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2022.2020241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Niazi SK. Biosimilars: harmonizing the approval guidelines. Biol Theory. 2022;2(3):171‐195. doi: 10.3390/biologics2030014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/recombinant-proteins

- 49. NIH Grant 1U01FD007763‐01 . Anna Schwendemen (PI) and Sarfaraz Niazi (CoPI). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-FD-22-026.html

- 50. MHRA . Biosimilar guidance. June 8, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance‐on‐the‐licensing‐ofbiosimilar‐products/guidance‐on‐the‐licensing‐of‐biosimilar‐products.

- 51. Niazi S. End animal testing for biosimilar approval. Science. 2022;377(6602):162‐163. doi: 10.1126/science.add4664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Niazi S. Scientific rationale for waiving clinical efficacy testing of biosimilars. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2022;16:2803‐2815. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S378813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. https://phrma.org/resource‐center/Topics/Access‐to‐Medicines/New‐Report‐Finds‐Largest‐PBMs‐Restrict‐Access‐to‐More‐Than‐1150‐Medicines

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.