Abstract

In the human proteome, 826 G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) interact with extracellular stimuli to initiate cascades of intracellular signaling. Determining conformational dynamics and intermolecular interactions are key to understand GPCR function as a basis for drug design. X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) contribute molecular architectures of GPCRs and GPCR-signaling complexes. NMR spectroscopy is complementary by providing information on the dynamics of GPCR structures at physiological temperature. In this review, several NMR approaches in use to probe GPCR dynamics and intermolecular interactions are discussed. The topics include uniform stable-isotope labeling, amino acid residue-selective stable-isotope labeling, site-specific labeling by genetic engineering, the introduction of 19F-NMR probes, and the use of paramagnetic nitroxide spin labels. The unique information provided by NMR spectroscopy contributes to our understanding of GPCR biology and thus adds to the foundations for rational drug design.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor dynamics, stable-isotope labeling, fluorine-19 NMR, GPCR biology, drug development

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are seven-transmembrane helix (TM) proteins which regulate cellular responses to extracellular stimuli, such as hormones and neurotransmitters [ 1– 3]. With 826 members in the human proteome, GPCRs represent one of the largest membrane protein families. GPCRs have been classified into five main classes, i.e., the rhodopsin (class A), secretin (class B), glutamate (class C), frizzled (class F) and adhesion GPCR families [4]. They are found in almost all human tissues and organs, and they are important drug targets because of their key physiological roles. It was estimated that over 700 approved prescription drugs target GPCRs, implying that approximately 35% of all approved drugs target GPCRs [5]. Structural information on GPCRs therefore has an important role as a foundation for “structure-based rational drug discovery”.

GPCRs interact with small molecule ligands as well as intracellular partner proteins [6]. Ligands binding to the orthosteric site on the extracellular GPCR surface ( Figure 1A) have been extensively studied and represent nearly all approved drug molecules. Orthosteric ligand binding has been shown to cause major conformational changes of GPCRs. The molecular architecture can be seen by crystallography or electron microscopy, while local conformational polymorphisms have in many cases been observed by NMR spectroscopy [7]. Generally, agonist-bound GPCRs mediate cellular responses by interacting with intracellular proteins such as G proteins and β-arrestins. Dual pathways of G protein and β-arrestin coupling have been described in a wide variety of in vitro and in vivo systems [ 8, 9]. Biased ligands preferentially activate one of the signaling pathways, which offers potential for reducing drug side effects and safety issues [10].

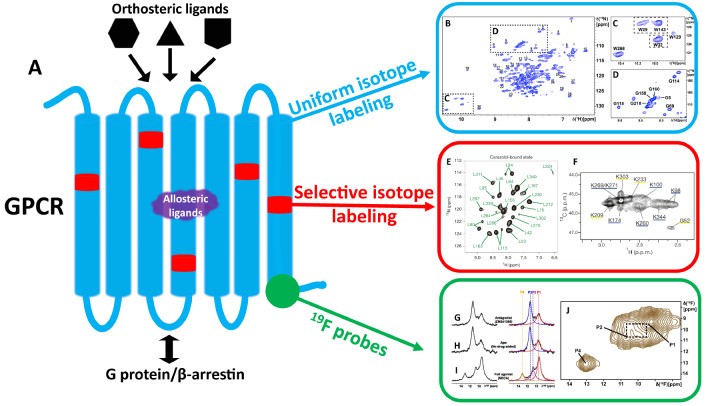

Figure 1 .

GPCR molecular structure and strategies for NMR characterization

(A) Schematic view of a GPCR molecular structure and its interactions with orthosteric and allosteric small molecule ligands (potentially druggable binding sites) and intracellular partner proteins. The black triangle, pentagon and hexagon represent different orthosteric ligands, which all target the orthosteric binding site on the extracellular surface. The purple polygon represents allosteric ligands, which may target a variety of binding sites in GPCR structures. Three NMR spectroscopy approaches to study conformational dynamics and intermolecular interactions of GPCRs are indicated on the right, i.e., uniform stable-isotope labeling (blue, B–D), residue-selective stable-isotope labeling (red, E–F) and 19F-NMR probes (green, G–J). In the GPCR structure, thin blue lines represent extracellular and intracellular loops, thick blue lines are the TMs, red spots and a green circle indicate sites for selective labelling with 13C or 15N, and with a 19F-label, respectively. (B–D) 2D [15N, 1H]-transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) of A2AAR in complex with the antagonist ZM241385. (E) 2D [15N, 1H]-TROSY spectrum of [2,3,3-2H, 15N]-leu-labeled β2AR. (F) 2D [13C, 1H]-heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC) spectrum of ε-N[13CH3]2-lysines in the μ-opioid receptor (μOR). (G–I) 1D 19F-NMR spectra of A2AAR[A289CTET] bound to an inverse agonist, in the apo-form, and bound to an agonist. Spectral components contained in the observed signal envelope are shown on the right of this panel. (J) 2D [19F, 19F]-EXSY spectrum of the A2AAR–agonist complex in I, recorded at 280 K with a mixing time of 100 ms. B to D are adapted from Figure1 in reference [20]. E is adapted from Figure1 in reference [23]. F is adapted from Figure1 in reference [28]. G to J are adapted from Figure1 in reference [29].

Allosteric ligands bind spatially distinct from the orthosteric pocket and can serve as additional tools to modulate function-related conformational states of the GPCRs. Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) increase the response of the receptor to a given orthosteric ligand, while negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) attenuate receptor activity [11]. Allosteric modulators approved as drugs include cinacalcet (PAM of a calcium-sensing receptor) and maraviroc (NAM of the chemokine receptor CCR5) [12]. Overall, allosteric ligands thus enrich the ways to manipulate the functions of GPCRs for potential therapeutic benefits [13].

NMR Methods for the Study of GPCRs

Since the molecular architecture of the human β 2-adrenergic receptor (β 2AR) was reported in 2007 [14], more than 400 structures of human GPCR complexes have been determined by X-ray crystallography [15]. During the past few years, cryo-electron microscopy contributed structure determinations of GPCR signaling complexes including orthosteric ligands and G proteins or β-arrestins. Recently, AI methods have generated GPCR structures with atomic accuracy even in cases in which no similar structure is known [ 16, 17]. NMR spectroscopy technologies complement the information on the molecular architectures obtained by these methods, especially with studies of the structural dynamics and of intermolecular interactions at physiological temperatures. Gautier et al. [18] also reported a de novo NMR structure determination of the phototaxis receptor sensory rhodopsin II (pSRII). With the use of transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) [19], it is quite generally possible to obtain de novo structure determination of GPCRs. However, NMR spectroscopy approaches to study structural dynamics of GPCRs and intermolecular interactions with GPCRs complement molecular architectures determined with different methods, and this type of NMR applications is pursued by many groups around the world.

NMR studies using uniform stable-isotope labeling

Uniform stable-isotope labeling is a widely-used method for structural studies of proteins. 15N and 13C are enriched in the protein far over the natural abundance to increase the sensitivity ( Table 1) and overcome the 1H signal overlapping problem of NMR spectroscopy with biological macromolecules. Eddy et al. [20] expressed A 2A adenosine receptor (A 2AAR) in Pichia pastoris to obtain uniform double labeling with 2H and 15N ( Figure 1B–D). All six tryptophan side-chain and eight glycine backbone 15N- 1H NMR signals were assigned by engineered amino acid replacements. The uniform labeling provided a comprehensive view of plasticity and structural dynamics of the entire receptor. Egloff et al. [21] and Nasr et al. [22] used directed evolution technologies to obtain rat neurotensin receptor 1 (NTR1) in E. coli, which was then reconstituted in circularized nanodiscs for collecting [ 15N, 1H]-TROSY spectra. Uniform stable-isotope labeling can afford, in principle, a comprehensive view of GPCR structural dynamics, but obtaining NMR assignments of GPCRs tends to be a major challenge [20]. Limitations arise because of the high cost of 13C, 15N, 2H triple-labeling and low expression levels. Furthermore, the molecular weight of detergent-solubilized complex of GPCRs is close to 100 kDa, which leads to increased line widths and signal overlaps in the NMR spectra.

Table 1 Nuclear properties of selected isotopes

|

NMR isotopes |

Spin |

Natural abundance (%) |

Gyromagnetic ratio (10 7 rad s −1 T −1) |

Sensitivity rel. 1H a |

|

1H |

1/2 |

99.99 |

26.7522 |

1.00 |

|

13C |

1/2 |

1.07 |

6.7282 |

1.59×10 −2 |

|

15N |

1/2 |

0.36 |

−2.7126 |

1.04×10 −3 |

|

19F |

1/2 |

100 |

25.1623 |

0.83 |

From Bruker topspin user guide, BRUKER Almanac. a For work at natural abundance, the effective sensitivity for NMR detection relative to 1H is obtained by multiplying the “sensitivity” with the “natural abundance” (in %).

NMR studies using amino acid residue-selective stable-isotope labeling

Residue-selective stable-isotope labeling reduces peak overlap in the NMR spectra, when compared with uniform stable-isotope labeling. Imai et al. [23] used [2,3,3- 2H, 15N]-leucine to selectively label β 2AR in insect cells ( Figure 1E). Assignments were established by engineered amino acid replacements, similar to the aforementioned illustration of uniform stable-isotope labeling [20]. Upon binding of the agonist formoterol, chemical shift differences larger than 0.4 ppm were observed for L212, L284 and L287, indicating that large local conformational changes of the PIF motif region are associated with activation. In addition to 15N, 13C enrichment has also been used for residue-selective stable-isotope labeling, such as 13C-dimethylated lysine [ 24, 25], and 13CH 3-ε-methionine [ 26, 27]. Sounier et al. [28] expressed the μ-opioid receptor (μOR) in sf9 and applied posttranslational reductive 13C-methylation to methylate the ε-NH 2 groups of lysine side chains (ε-N[ 13CH 3] 2-lysines). Figure 1F shows the [ 13C, 1H]-heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC) spectrum of the 13C labeled μOR. Comparisons of the spectra of μOR with different ligands bound indicated that conformational changes in TM5 and TM6 are almost completely dependent on the presence of both the agonist and a G protein mimetic nanobody. Residue-selective stable-isotope labeling can quite generally yield multiple-site structural dynamics information from NMR spectra with reduced peak overlap, as applied in the illustrations of Figure 1E,F, with GPCRs from eukaryotic expression systems.

NMR studies using chemically conjugated 19F-NMR probes

Although the uniform or residue-selective labeling methods have been greatly optimized, it is challenging for GPCRs to be highly expressed in labeling media for insect cells or mammalian systems. 19F is an attractive nucleus with high sensitivity and 100% natural abundance ( Table 1). Furthermore, 19F is rarely found in biological macromolecules, which enables the NMR detection of extrinsic 19F labels with minimal background signals. 19F-probes can be introduced by post-translational chemical modification [30], and they have been widely used for studies of structure and dynamics of proteins during the past several decades [ 31– 34]. As with all extrinsic probes, one has to deal with the concern that fluorine labeling could affect the conformation of the protein. However, indications so far are that GPCR conformations are little affected by carefully designed labeling sites. This is especially true for the post-translational conjugation of the fluorine labels, since only solvent-exposed residues are readily labeled. Proper functional assays and combination of 19F-NMR with other biophysical and biochemical methods help to verify that structure and function of the receptor are preserved after labeling with fluorine probes.

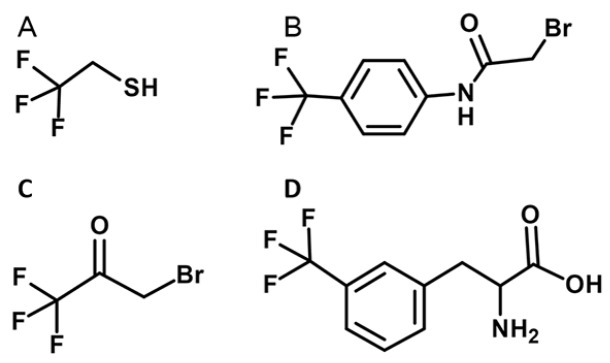

Figure 2 presents the chemical structures of 19F-NMR probes that have been used for studies of GPCRs. The sizes of 3-bromo-1,1,1-trifluoroacetone (BTFA) and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanethiol (TET) are small, causing minimal structural perturbations [30]. BTFA, which can form a stable thioester bond with the protein by a one-step process, has been used in β 2AR studies [35]. Similarly, TET, which can link with cysteines by a disulfide bond, has been used in β 2AR and A 2AAR [ 36, 29]. 2-bromo-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl) acetamide (BTFMA) exhibits an outstandingly large range of chemical shift differences with variable solvent polarity [37], and it has been used for interaction studies of A 2AAR with G-proteins [38].

Figure 2 .

Chemical structures of 19F-NMR probes used for studies of GPCRs

(A) 2,2,2-trifluoroethanethiol (TET). (B) 2-bromo-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl) acetamide (BTFMA). (C) 3-bromo-1,1,1-trifluoroacetone (BTFA). (D) 3-trifluoromethyl-L-phenylalanine (mtfF).

In a historical first, Klein-Seetharaman et al. [39] applied TET to successfully label rhodopsin in detergent micelles. Six single cysteine mutants of rhodopsin were labeled and studied with 19F-NMR in dark environment and after illumination. Clear chemical shift changes demonstrated the applicability of solution 19F-NMR spectroscopy for studies of different rhodopsin activation states in the dark and on light activation. TET labels were also introduced into β 2AR, and 19F-NMR revealed equilibria between simultaneously populated, locally different conformational states near the cytoplasmic receptors surface [36]. While agonist binding primarily shifts the equilibrium towards the G protein-specific active state, the β-arrestin-biased ligands predominantly impact the other conformational state. 2D [ 19F, 19F] exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) and 1D 19F saturation transfer NMR experiments were then used to further investigate the exchange rates between the two conformational states [40]. Sušac et al. [29] successfully introduced TET probes to the intracellular surface of A 2AAR, showing largely different 1D 19F-NMR spectra for A 2AAR[A289C TET] bound to an inverse agonist, in the apo-form, and bound to an agonist ( Figure 1G–I). Two signals with chemical shifts of 11.4 ppm and 9.5 ppm were observed in the apo-form and the antagonist bound state of A 2AAR, representing two conformational states. In the active-like state of the agonist complex, two new peaks at 10.8 ppm and 13.1 ppm appeared, indicating a transition to a different conformational state. EXSY cross peaks ( Figure 1J) then further demonstrated conformational exchange between the different activation levels. These results suggest that A 2AAR activation includes both induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms. In addition, the comparison of A 2AAR and a constitutively active mutant established correlations between NMR parameters and GPCR basal activity.

These works nicely illustrate advantages of 19F-NMR probes for studies of conformational dynamics of GPCRs. However, care needs to be exercised to account for possible non-specific labeling with 19F-NMR probes [ 35, 41]. In-membrane chemical modification (IMCM) was developed to obtain selective chromophore labeling of intracellular surface cysteines in GPCRs with minimal mutagenesis [42], which greatly reduced the non-specific labeling problem encountered in detergent micelles.

NMR studies using genetically incorporated 19F-NMR probes

Most of the human GPCRs harbor more than 10 cysteine residues, and mutation of all surface-exposed cysteine residues for the prevention of non-specific labeling may cause significant structural perturbation. Moreover, residues buried in the protein core cannot usually be labeled through the chemical conjugation approach described in the preceding section. Genetic incorporation of fluorine-containing unnatural amino acids can overcome these limitations of the cysteine conjugation methods, which ensures that the modified protein can be expressed with sufficiently high yields.

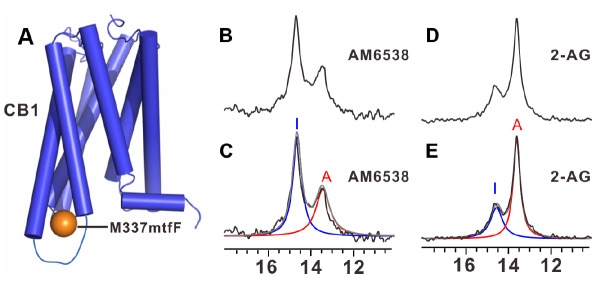

19F-containing phenylalanine and tyrosine analogs have been incorporated into proteins in prokaryotic expression system [ 43– 46]. In 2021, Wang et al. [47] reported successful genetic incorporation of 3′-trifluoromethyl-L-phenylalanine (mtfF, see Figure 2D) into the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), using the baculovirus sf9 expression system. Figure 3A is a schematic view of CB1 with this genetically engineered mtfF probe at the sequence position 337. Figure 3B,D shows the 1D 19F-NMR spectra of CB1 [M337 6.29mtfF] in complexes with the antagonist AM6538 and the agonist 2-AG, respectively. Two 19F-NMR peaks at 14.6 ppm (I) and 13.5 ppm (A) represent inactive and active-like states, respectively. Effects of the allosteric modulator Org27569 on the conformational landscape of CB1 were also characterized. Using this approach for investigating site-specific dynamics of GPCRs adds to the great potential of 19F-NMR probes in eukaryotic proteins. With genetically incorporated 19F-NMR probes, the peak assignment is straightforward, and the aforementioned non-specific labeling problem with chemical conjugation methods is, in principle, not encountered.

Figure 3 .

Schematic view of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) with 19F-NMR probe and its 19F-NMR spectra

(A) Schematic view of CB1 with a genetically engineered 19F-NMR probe, 3-(trifluoromethyl) phenylalanine (mtfF) at the sequence position 3376.29. The brown sphere represents the position of the mtfF. (B,D) 1D 19F-NMR spectra of CB1 [M3376.29mtfF] in complexes with the antagonist AM6538 and the agonist 2-AG, respectively. (C,E) Spectra of B,D, respectively, with indication of the component signals (blue and red) identified by Lorentzian deconvolution. The spectra B to E were previously included in Figure2 of reference [47].

NMR studies using paramagnetic nitroxide spin labels

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) is often used for studying long-distance intra- or intermolecular interactions [ 48– 50]. The unpaired electron spin (such as a nitroxide spin-label or paramagnetic metal ions) enhances the relaxation rates and may affect the chemical shifts of nearby nuclear spins. The PRE decreases proportional to r –6 (where r is the distance between the paramagnetic center and the nuclear spin), and the effects over distances up to about 20 Å can be observed with nitroxide spin labels [51]. Using the spin-label, S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro- 1H-pyrrol-3yl) methyl methanesulfonothioate (MTSL) introduced by chemical coupling, Imai et al. [23] evaluated the distance between a particular amide proton and this paramagnetic center in β 2AR. In addition, the solvent accessibilities of residues in GPCRs could be examined by solvent PRE experiments. Takuya et al. [52] used Gd-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-bismethylamide (Gd-DTPA-BMA), which is a highly water-soluble paramagnetic probe, to investigate the solvent accessibilities of the methionine residues in [[α,β,β- 2H, methyl- 13C] Met, u- 2H] A 2AAR. From the NMR studies, the authors concluded that the A 2AAR conformation was shifted toward states that are preferable for G protein binding. Similar paramagnetic Gd 3+-DTPA probe was used by Lindsay et al. [53] to detect solvent accessibility. The solvent PRE effects seen for Ile δ1- 13C-labeled A 2AAR indicated that breathing of the structure to expose this region to the Gd 3+-DTPA complex. Combined with the aforementioned stable-isotope labeling methods of GPCRs, PRE opens avenues to a wide range of novel strategies.

Conclusions and Perspectives

With the use of various labeling methods, NMR spectroscopy is an attractive technique in structural biology of GPCRs. NMR spectroscopy is used to explore conformational dynamics and intermolecular interactions to complement the molecular architectures obtained from X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy [7]. De novo structure determination of GPCRs with NMR spectroscopy in solution has also been described [18], but this is currently not a focus and no similar work has recently appeared. Among the various labeling approaches, 19F-NMR probes have outstanding potential to investigate conformational equilibria and associated rate processes with high sensitivity. Genetic site-specific 19F-labeling technique in eukaryotic expression systems promises to become a powerful tool for studies of otherwise not detectable conformational states of GPCRs. With future improvements of biochemical and biosynthetic methods, for uniform or selective stable-isotope labeling as well as for the introduction of 19F-probes and paramagnetic nitroxide spin labels, NMR spectroscopy in solution will further strengthen its role in GPCR structural biology.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21904088 to L.Y. and No. 31971153 to D.L.). K.W. acknowledges the support from “1000 Talent Plan for High-level Foreign Experts” of the Shanghai government. K.W. is the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Professor of Structural Biology at Scripps Research.

References

- 1.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. . 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. . 2005;85:1159–1204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonin AV, Darling AL, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Uversky VN. Multi-functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder-based proteoforms. Cell Mol Life Sci. . 2019;76:4461–4492. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander SP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, et al. The concise guide to pharmacology 2015/16: overview. Br J Pharmacol. . 2015;172:5729–5743. doi: 10.1111/bph.13347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriram K, Insel PA. G protein-coupled receptors as targets for approved drugs: how many targets and how many drugs? Mol Pharmacol. . 2018;93:251–258. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.111062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SGF, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. . 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada I, Ueda T, Kofuku Y, Eddy MT, Wüthrich K. GPCR drug discovery: integrating solution NMR data with crystal and cryo-EM structures. Nat Rev Drug Discov. . 2019;18:59–82. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wingler LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Conformational basis of G protein-coupled receptor signaling versatility. Trends Cell Biol. . 2020;30:736–747. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisler JW, Rockman HA, Lefkowitz RJ. Biased G protein–coupled receptor signaling. Circulation. . 2018;137:2315–2317. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JS, Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal S. Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. . 2018;17:243–260. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentry PR, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Novel allosteric modulators of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. . 2015;290:19478–19488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.662759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. . 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wootten D, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM. Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. . 2013;12:630–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen SGF, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, et al. Crystal structure of the human β2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. . 2007;450:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kooistra AJ, Mordalski S, Pándy-Szekeres G, Esguerra M, Mamyrbekov A, Munk C, Keserű GM, et al. GPCRdb in 2021: integrating GPCR sequence, structure and function. Nucleic Acids Res. . 2021;49:D335–D343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baek M, DiMaio F, Anishchenko I, Dauparas J, Ovchinnikov S, Lee GR, Wang J, et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. . 2021;373:871–876. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. . 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautier A, Mott HR, Bostock MJ, Kirkpatrick JP, Nietlispach D. Structure determination of the seven-helix transmembrane receptor sensory rhodopsin II by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. . 2010;17:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Attenuated T 2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole–dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. . 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eddy MT, Lee MY, Gao ZG, White KL, Didenko T, Horst R, Audet M, et al. Allosteric coupling of drug binding and intracellular signaling in the A 2A adenosine receptor . Cell. . 2018;172:68–80.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egloff P, Hillenbrand M, Klenk C, Batyuk A, Heine P, Balada S, Schlinkmann KM, et al. Structure of signaling-competent neurotensin receptor 1 obtained by directed evolution in Escherichia coli . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. . 2014;111:E655–E662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317903111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasr ML, Baptista D, Strauss M, Sun ZYJ, Grigoriu S, Huser S, Plückthun A, et al. Covalently circularized nanodiscs for studying membrane proteins and viral entry. Nat Methods. . 2017;14:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imai S, Yokomizo T, Kofuku Y, Shiraishi Y, Ueda T, Shimada I. Structural equilibrium underlying ligand-dependent activation of β 2-adrenoreceptor . Nat Chem Biol. . 2020;16:430–439. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bokoch MP, Zou Y, Rasmussen SGF, Liu CW, Nygaard R, Rosenbaum DM, Fung JJ, et al. Ligand-specific regulation of the extracellular surface of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. . 2010;463:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Hu Y, Batebi H, Heng J, Xu J, Liu X, Niu X, et al. Analysis of β 2 AR-G s and β 2 AR-G i complex formation by NMR spectroscopy . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. . 2020;117:23096–23105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009786117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Hu Y, Kaindl J, Risel P, Hübner H, Maeda S, Niu X, et al. Conformational complexity and dynamics in a muscarinic receptor revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Mol Cell. . 2019;75:53–65.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu FJ, Williams LM, Abdul-Ridha A, Gunatilaka A, Vaid TM, Kocan M, Whitehead AR, et al. Probing the correlation between ligand efficacy and conformational diversity at the α1A-adrenoreceptor reveals allosteric coupling of its microswitches. J Biol Chem. . 2020;295:7404–7417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sounier R, Mas C, Steyaert J, Laeremans T, Manglik A, Huang W, Kobilka BK, et al. Propagation of conformational changes during μ-opioid receptor activation. Nature. . 2015;524:375–378. doi: 10.1038/nature14680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sušac L, Eddy MT, Didenko T, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. A 2A adenosine receptor functional states characterized by 19 F-NMR . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. . 2018;115:12733–12738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813649115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Didenko T, Liu JJ, Horst R, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. Fluorine-19 NMR of integral membrane proteins illustrated with studies of GPCRs. Curr Opin Struct Biol. . 2013;23:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerig JT. Fluorine NMR of proteins. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. . 1994;26:293–370. doi: 10.1016/0079-6565(94)80009-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou Y, Hu W, Li X, Skinner JJ, Liu D, Wüthrich K. Solvent-accessibility of discrete residue positions in the polypeptide hormone glucagon by 19F-NMR observation of 4-fluorophenylalanine . J Biomol NMR. . 2017;68:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10858-017-0107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picard LP, Prosser RS. Advances in the study of GPCRs by 19F NMR . Curr Opin Struct Biol. . 2021;69:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, McFarland A, Madsen JJ, Aalo E, Ye L. The potential of 19F NMR application in GPCR biased drug discovery . Trends Pharmacol Sci. . 2021;42:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KY, Kim TH, Manglik A, Alvares R, Kobilka BK, Prosser RS. Role of detergents in conformational exchange of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. . 2012;287:36305–36311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.406371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. Biased signaling pathways in β 2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR . Science. . 2012;335:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye L, Larda ST, Frank Li YF, Manglik A, Prosser RS. A comparison of chemical shift sensitivity of trifluoromethyl tags: optimizing resolution in 19F NMR studies of proteins . J Biomol NMR. . 2015;62:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang SK, Pandey A, Tran DP, Villanueva NL, Kitao A, Sunahara RK, Sljoka A, et al. Delineating the conformational landscape of the adenosine A2A receptor during G protein coupling. Cell. . 2021;184:1884–1894.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein-Seetharaman J, Getmanova EV, Loewen MC, Reeves PJ, Khorana HG. NMR spectroscopy in studies of light-induced structural changes in mammalian rhodopsin: applicability of solution 19F NMR . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. . 1999;96:13744–13749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horst R, Liu JJ, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. β 2-Adrenergic receptor activation by agonists studied with 19F NMR spectroscopy . Angew Chem Int Ed. . 2013;52:10762–10765. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim TH, Chung KY, Manglik A, Hansen AL, Dror RO, Mildorf TJ, Shaw DE, et al. The role of ligands on the equilibria between functional states of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Am Chem Soc. . 2013;135:9465–9474. doi: 10.1021/ja404305k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sušac L, O’Connor C, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. In-membrane chemical modification (IMCM) for site-specific chromophore labeling of GPCRs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. . 2015;54:15246–15249. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson JC, Hammill JT, Mehl RA. Site-Specific Incorporation of a 19 F-Amino Acid into Proteins as an NMR Probe for Characterizing Protein Structure and Reactivity . J Am Chem Soc. . 2007;129:1160–1166. doi: 10.1021/ja064661t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones DH, Cellitti SE, Hao X, Zhang Q, Jahnz M, Summerer D, Schultz PG, et al. Site-specific labeling of proteins with NMR-active unnatural amino acids. J Biomol NMR. . 2009;46:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi P, Wang H, Xi Z, Shi C, Xiong Y, Tian C. Site-specific 19F NMR chemical shift and side chain relaxation analysis of a membrane protein labeled with an unnatural amino acid . Protein Sci. . 2011;20:224–228. doi: 10.1002/pro.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li F, Shi P, Li J, Yang F, Wang T, Zhang W, Gao F, et al. A genetically encoded 19F NMR probe for tyrosine phosphorylation . Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. . 2013;52:3958–3962. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Liu D, Shen L, Li F, Li Y, Yang L, Xu T, et al. A genetically encoded F-19 NMR probe reveals the allosteric modulation mechanism of cannabinoid receptor 1. J Am Chem Soc. . 2021;143:16320–16325. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McConnell HM, McFarland BG. Physics and chemistry of spin labels. Q Rev Biophys. . 1970;3:91–136. doi: 10.1017/S003358350000442X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaffney BJ, Willingham GL, Schepp RS. Synthesis and membrane interactions of spin-label bifunctional reagents. Biochemistry. . 1983;22:881–892. doi: 10.1021/bi00273a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeschke G. Conformational dynamics and distribution of nitroxide spin labels. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. . 2013;72:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madl T, Sattler M. NMR methodologies for the analysis of protein–protein interactions. In: Ivano B, Kathleen SM, Giacomo P eds. NMR of Biomolecules. . 1st ed. Germany: Wiley-VCH 2012, 173-194

- 52.Mizumura T, Kondo K, Kurita M, Kofuku Y, Natsume M, Imai S, Shiraishi Y, et al. Activation of adenosine A 2A receptor by lipids from docosahexaenoic acid revealed by NMR . Sci Adv. . 2020;6:eaay8544. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay8544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark LD, Dikiy I, Chapman K, Rödström KE, Aramini J, LeVine MV, Khelashvili G, et al. Ligand modulation of sidechain dynamics in a wild-type human GPCR. eLife. . 2017;6:e28505. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]