Abstract

Objective:

Informal family caregivers provide critical support for patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. However, caregivers' experiences are largely unstudied. This study examined quality of life (QOL; physical functioning, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression), caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress in caregivers in the first 6 months after CAR T-cell therapy, when caregivers were expected to be most involved in providing care. Relationships between patients' clinical course and caregiver outcomes were also explored.

Methods:

Caregivers completed measures examining QOL and burden before patients' CAR T-cell therapy and at days 90 and 180. Treatment-related distress was assessed at days 90 and 180. Patients' clinical variables were extracted from medical charts. Change in outcomes was assessed using means and 99% confidence intervals. Association of change in outcomes with patient clinical variables was assessed with backward elimination analysis.

Results:

A total of 99 caregivers (mean age 59, 73% female) provided data. Regarding QOL, pain was significantly higher than population norms at baseline but improved by day 180 (p < .01). Conversely, anxiety worsened over time (p < .01). Caregiver burden and treatment-related distress did not change over time. Worsening caregiver depression by day 180 was associated with lower patient baseline performance status (p < .01). Worse caregiver treatment-related distress at day 180 was associated with lower performance status, intensive care unit admission, and lack of disease response at day 90 (ps < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Some CAR T-cell therapy caregivers experience pain, anxiety, and burden, which may be associated patients' health status. Further research is warranted regarding the experience of CAR T-cell therapy caregivers.

Keywords: adoptive immunotherapy, cancer, caregivers, chimeric antigen receptors, quality of life, psycho-oncology

1 ∣. BACKGROUND

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has resulted in durable remissions for approximately 40% of patients with relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies for whom other treatments have failed.1,2 Due to their advanced disease before CAR T-cell therapy, patients may be debilitated and require assistance from an informal caregiver. Patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy are also required by most programs to have a caregiver during their inpatient stay and recovery period.3 Caregivers may be anyone with a personal relationship to the patient (e.g., family member or friend) who provides support to the patient. Caregivers often help monitor CAR T-cell therapy-related side effects and provide support if the patient's health status worsens. Data from other cancer caregivers suggest they are at elevated risk of negative outcomes such as poor physical health and quality of life (QOL), elevated depression and post-traumatic stress symptomatology, and increased likelihood of sleep disorders.4 Notably, the cancer experience can be more distressing for caregivers than for patients themselves.5

CAR-T caregivers may experience considerable distress in particular due to the patient's relapsed/refractory disease, uncertainty regarding CAR T-cell therapy outcomes, and potential uncertainties inherent in transferring care to a cancer center that provides this novel therapy. The unique toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy may increase caregiver distress during the acute treatment period.6 Toxicities, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, can be life-threatening or cause temporary mental status and personality changes in the patient.7 Caregivers' experience of CAR T-cell therapy is largely unstudied. Research is needed to help educate future caregivers about what to expect during CAR T-cell therapy and to identify unmet caregiver needs.

The aims of the present study were twofold. The first aim was to describe changes over time in caregivers' QOL (i.e., physical functioning, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression), caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress in the first 6 months after CAR T-cell therapy, when the responsibilities of the caregiver were likely to be greatest. Because this is the first published study of CAR T-cell caregivers to our knowledge, to provide context we compared caregiving burden among study participants to published data from caregivers of other patient populations (e.g., dementia patients). The second aim was to explore associations of patients' clinical course (e.g., baseline performance status, CRS, neurotoxicity, and intensive care admission) with caregiver QOL, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress at day 90 and 180 post CAR T-cell therapy infusion. As aims of the study were exploratory in nature, no hypotheses were generated a priori.

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Participants

Participants were recruited prospectively as part of a larger, two-part study assessing patient-reported outcomes in caregivers and adult patients with hematologic malignancies scheduled to receive CAR T-cell therapy. Eligible caregivers were at least 18 years old, identified as a primary informal caregiver by a consented patient, able to speak and read English, and able to provide informed consent.

2.2 ∣. Procedure

Caregivers were recruited between October 2016 and September 2019 for Part I of the study, which focused on their caregiving experience before scheduled CAR T-cell therapy. Caregivers were consented and completed questionnaires prior to patient receipt of conditioning chemotherapy in preparation for CAR T-cell therapy. Caregivers who consented to the Part I were invited to participate in a second, longitudinal part focused on caregiving after CAR T-cell therapy. Caregivers were consented for Part II at day 90 and were asked to complete follow-up questionnaires at day 90 and 180. The study was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board, protocol approval number Pro00019234.

2.3 ∣. Measures

Caregivers self-reported the following demographic variables at baseline: age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, and income. Patients' clinical data were extracted from medical charts and included baseline Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index (HCT-CI),8 highest grade of CRS, highest grade of neurotoxicity, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), number of days hospitalized during the first 100 days post CAR T-cell therapy infusion, and disease response at day 90. CRS and neurotoxicity were graded by the provider on a 5-point scale with higher scores indicating worse toxicity. Grading was first conducted in accordance with the CAR-T cell-therapy associated TOXicity classification system,9 and then with the American Society of Transplant and Cellular Therapy Consensus Grading for CRS and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells grading systems, based on the practice guidelines published in 2018.10

Caregiver quality of life was assessed at all-time points in Part I and II of the study. Initially the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form-36 (SF-36) was used.11 Following the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services coverage decision for CAR T-cell therapy in February 2019 recommending use of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-29 Profile v2.1 (PROMIS®-29) to assess quality of life outcomes in patients,12 the SF-36 was replaced by PROMIS®-2913 for both patients and caregivers. Using the established and well-validated PROsetta Stone® data harmonization methodology,14 SF-36 scores were converted to PROMIS®-29 T-scores. The PROsetta Stone® conversion yields five outcomes: physical functioning, pain interference, fatigue, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating more of the construct being measured. A mean score of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 correspond to US population norms.15 To place these findings in context, a difference of 0.5 SD is generally considered clinically significant,16 which corresponds to a difference score of 5 points on the PROMIS-29.

Caregiving burden was assessed at all-time points in Parts I and II of the study with the 22-item Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (CBI).17 The CBI captures the effects of caregiving on the caregiver's physical and psychological well-being, finances, social life, and relationship with the patient. Item responses range from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always). Total scores range from 0 to 88. Scores of 41 or above indicate moderate to severe burden.17

Caregiver treatment-related distress was assessed only in Part II of the study (i.e., day 90 and 180) with the 7-item intrusion subscale of the Impact of Events Scale.18 Examples of items on this subscale are “I had dreams about the event” and “Other things kept making me think about the event.” Items were keyed to distress about the patient's cancer and its treatment over the past week. Item responses range from 0 (not at all) to 5 (often). Scores of 20 or above indicate clinically significant treatment-related distress.19

2.4 ∣. Statistical analysis

Caregivers were included in the current analysis if they completed one or more assessments in either Part I or Part II. Means, SD, frequencies, and percentages were used to describe caregivers' demographic characteristics and patients' clinical course. Independent samples t-tests, chi-square tests, and Fishers exact tests were used to compare caregiver characteristics (i.e., age, sex, marital status, race, ethnicity, education, income, quality of life, and burden) and patient clinical characteristics (i.e., days to hospitalization in the first 100 days, ICU admission, KPS, comorbidities, CRS, neurotoxicity, and disease response) between caregivers who consented to Part II and those who did not. Non-consented caregivers included those who dropped, withdrew or declined before day 90; caregivers of patients who passed away before day 90 were not included. Means and 99% confidence intervals (CI) were used to evaluate changes in caregiver quality of life, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress over time. Linear regression analyses with backward elimination were used to estimate residualized change in quality of life and caregiver burden from baseline to day 90 and 180 and examine associations with patient characteristics including baseline KPS (less than 80 vs. 80 or higher), HCT-CI (2 or less vs. 3 or higher), highest grade of CRS and neurotoxicity (score of 0 or 1 vs. score of 2–4), admission to the ICU, number of days hospitalized during the first 100 days, and disease response at day 90. Baseline caregiver outcome was included in residualized change models (i.e., baseline depression to predict depression at day 90 and 180). Although linear regression analyses were exploratory, p values < 0.01 in these analyses were considered statistically significant to reduce the possibility of Type I error. A one-half SD was used to determine clinically significant changes in caregivers' outcomes and differences compared to population norms.16 All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

3 ∣. RESULTS

In total, 99 caregivers completed at least one assessment and were included in analyses (see Figure S1). Caregivers' and patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. On average, caregivers were 59 years old and the majority were female, white, non-Hispanic, and married. Caregivers who consented to Part II (n = 58) did not differ from those who did not (n = 34) on sociodemographic characteristics, baseline quality of life, baseline caregiver burden, or patient clinical characteristics (p values ≥ 0.10).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 99 caregivers)

| Caregiver demographic characteristics | |

| Age: Mean (SD) | 59.01 (12.22) |

| Sex: n (%) female | 69 (73) |

| Race: n (%) white | 84 (89) |

| Ethnicity: n (%), non-Hispanic | 83 (92) |

| Marital status: n (%) married | 81 (85) |

| Education: n (%) college graduate | 53 (56) |

| Annual household income: n (%) ≥$40,000 | 61 (80) |

| Patient clinical characteristics | |

| Diagnosis: non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n) % | 83 (84) |

| Baseline KPS: n (%) ≥80 | 86 (90) |

| Baseline HCT-CI: n (%) ≥3 | 34 (38) |

| Maximum CRS: n (%) Grade 2-4 | 40 (41) |

| Maximum neurotoxicity: n (%) Grade 2-4 | 21 (22) |

| ICU Admission: n (%) yes | 12 (13) |

| Disease response at day 90: n (%) yes | 61 (67) |

| Inpatient days until day 100: Mean (SD) | 15.74 (10.33) |

Abbreviations: CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HCT-CI, Hematopoietic Cell Transplant-Comorbidity Index; ICU, intensive care unit; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status.

Means and 99% CI for caregiver quality of life, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress over time are provided in Table 2. Changes in quality of life (i.e., physical function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression) among caregivers are shown in Figure S2. Pain significantly decreased from baseline to day 180 (p < 0.01) whereas anxiety worsened over the same time period (p < 0.01). No significant changes over time were observed for caregiver physical function, fatigue, or depression (p > 0.01). Notably, pain was on average one SD above the threshold at baseline, indicating caregivers' pain was clinically meaningful.15 No other clinically meaningful differences were observed when comparing caregiver physical function, fatigue, anxiety, and depression to population norms. Regarding caregiving burden, 15% of caregivers reported moderate to severe burden at baseline, 17% at day 90, and 16% at day 180. There were no significant changes in mean caregiver burden over time. Clinically significant treatment-related distress was reported by 33% of caregivers at day 90 and 24% at day 180. There were no significant changes in mean treatment-related distress over time.

TABLE 2.

Caregiver quality of life, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress over time

| Part I |

Part II |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 96) |

Day 90 (n = 53) |

Day 180 (n = 49) |

||||

| Mean | 99% CI | Mean | 99% CI | Mean | 99% CI | |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| Physical function | 51.32 | 49.00–53.64 | 50.35 | 47.22–53.49 | 50.57 | 47.54–53.60 |

| Pain | 61.32 | 57.98–64.66 | 59.35 | 54.65–64.04 | 52.77 | 48.33–57.22 |

| Fatigue | 49.11 | 46.80–51.42 | 49.71 | 45.35–54.06 | 48.91 | 44.15–53.67 |

| Anxiety | 51.53 | 49.23–53.82 | 54.01 | 48.57–59.45 | 59.93 | 54.11–65.75 |

| Depression | 48.68 | 46.70–50.66 | 48.91 | 45.33–52.50 | 49.24 | 45.30–53.17 |

| Caregiving burden | 22.65 | 18.76–26.55 | 21.61 | 15.23–27.99 | 20.41 | 13.96–26.85 |

| Distress | - | - | 11.81 | 8.17–15.46 | 11.63 | 7.40–15.86 |

Notes: Higher scores indicate more of all variables assessed. Treatment-related distress was not assessed in Part I of the study because CAR T-cell therapy had not yet occurred. Bold numbers indicate statistically significant differences among outcomes over time.

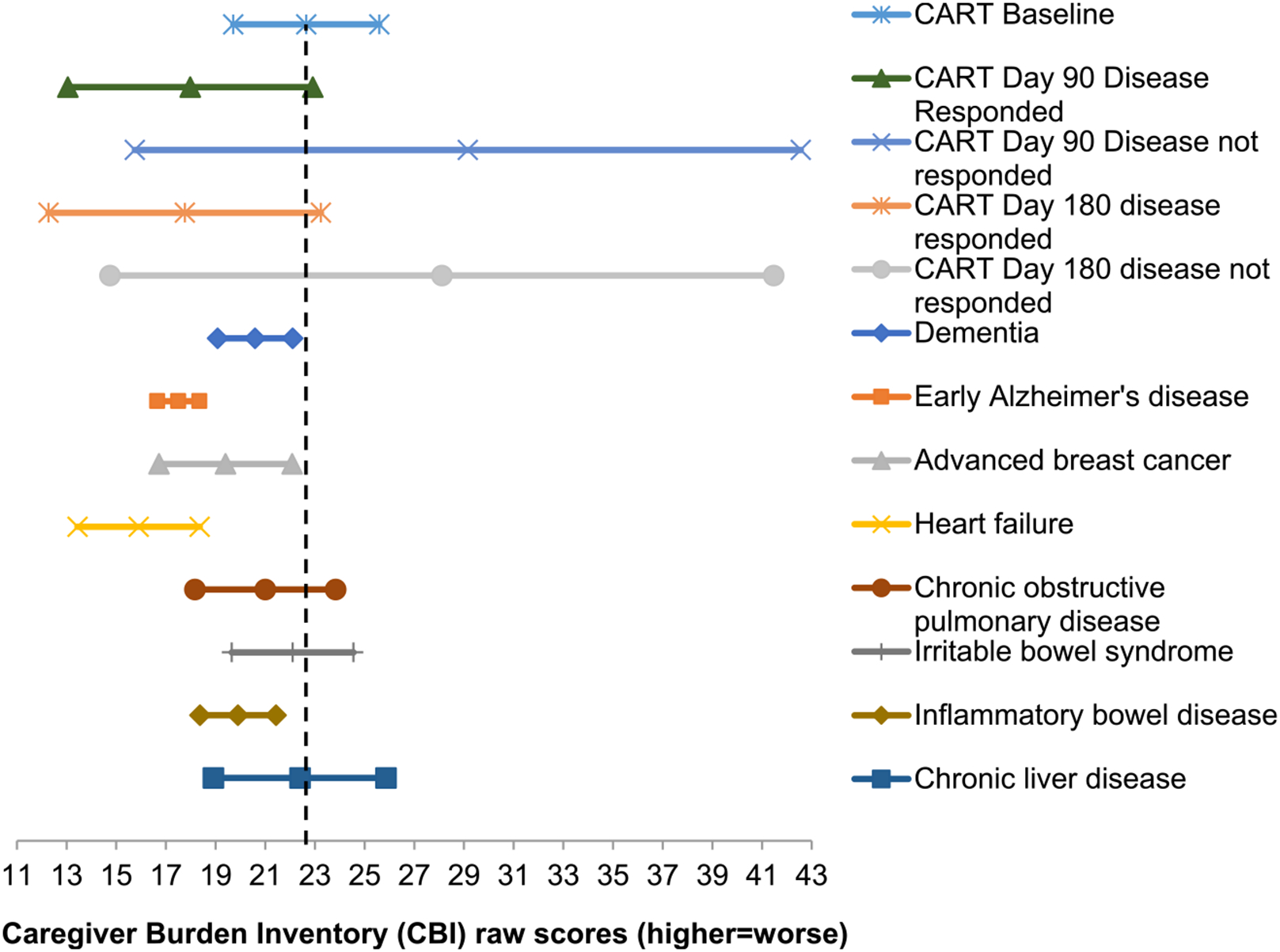

CAR T-cell therapy caregiving burden scores were compared to other caregiver samples using mean difference scores and 95% CI (Figure 1). Prior to CAR T-cell therapy, caregivers reported more caregiving burden than those caring for patients with early Alzheimer's disease and heart failure.20,21 Caregivers of patients whose disease responded to CAR T-cell therapy did not differ in caregiving burden at day 90 and 180 relative to other population of caregivers.20-26 Caregivers of patients whose disease did not respond to CAR T-cell therapy reported more caregiver burden at day 90 than caregivers of patients with early Alzheimer's disease, advanced breast cancer, heart failure and inflammatory bowel disease.20,21,23,24 Caregivers of patients whose disease did not respond to CAR T-cell therapy reported more caregiving burden at day 180 than caregivers of patients with early Alzheimer disease, heart failure and, inflammatory bowel disease.20,21,24

FIGURE 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals in caregivers of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy patients compared to other populations of caregivers

Results of the linear regression analyses are shown in Table 3. Increases in depression from baseline to day 180 were associated with worse baseline patient KPS (p < 0.01). Greater burden at day 90 and 180 was associated with greater baseline burden (p < .01). Residualized change in caregiver outcomes from baseline to day 90 or 180 was not associated with any other patient clinical variables. Greater treatment-related distress at day 180 was significantly associated with worse patient baseline KPS, ICU admission, and lack of disease response (p values < .01).

TABLE 3.

Associations among caregiver outcomes and patient clinical characteristics

| Physical function |

Pain |

Fatigue |

Depression |

Anxiety |

Caregiving burden |

Treatment-related distress |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 90 | Day 180 | |

| R 2 | 43% | 41% | 26% | 0% | 51% | 51% | 51% | 55% | 0% | 0% | 61% | 51% | 0% | 56%** |

| Intercept | 17.29* | 24.22** | 27.62* | 52.51** | 5.34 | −2.72 | 5.64 | 20.72 | 54.00** | 59.44** | 0.39 | 1.56 | 11.05** | 32.07** |

| Baseline caregiver outcome | 0.65** | 0.53** | 0.52** | - | 0.88** | 1.01** | 0.88** | 0.76** | - | - | 1.02** | 0.85** | N/A | N/A |

| Number of hospital days | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| KPS ≥ 80a | - | - | - | - | - | - | −10.50* | - | - | - | - | −14.22** | ||

| High comorbidities HCT ≥ 3a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CRS ≥ grade 2a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Neurotoxicity ≥ grade 2a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ICU admissiona | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11.91* |

| Disease responsea | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −13.43** | |||

Notes: All clinical variables were introduced in each model. Baseline levels of caregiver outcomes were included in all models (i.e., baseline physical function as a predictor of physical function at day 90 and 180) with the exception of treatment-related distress, which was not assessed at baseline. As a guide to interpretation, R2 indicates the percentage of variance in the outcome accounted by predictor variables, and the intercept indicates the outcome score at the assessment point. The estimates indicate differences in outcomes for each one unit increase of the predictor variable and empty rows indicate non-significant associations. Higher scores indicate worse caregivers' well-being, except for physical function, where higher scores indicate better well-being.

0 = no, 1 = yes.

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to examine quality of life, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress in informal caregivers of CAR T-cell therapy recipients. Results indicate that caregivers experience clinically meaningful pain on average before CAR T-cell therapy and worsening anxiety over time. In addition, up to 17% of caregivers reported moderate to severe caregiving burden and up to 33% reported clinically significant treatment-related distress before or within the first 6 months after CAR T-cell therapy. Interestingly, worse patient health status was associated with worse caregiver depression and distress over time. These results provide important new knowledge that can be used to help support caregivers as CAR T-cell therapy is increasingly used.27

Regarding caregiver quality of life, results indicate that pain was higher than population norms at baseline but significantly decreased over time. While caregiver pain is not widely studied, pain is prevalent in the general population,28 with some evidence suggesting that pain is related to psychological stress.29 Research in other caregiving contexts suggest that caregiver pain may be specifically related to caregiver stress and burden.30,31 Caregivers commonly put off addressing their own health needs and infrequently engage in self-care practice32,33 As such, the intensive nature of CAR-T caregiving may exacerbate existing pain issues. Future research should examine self-care in caregivers of CAR T-cell therapy recipients.

Caregiver anxiety at baseline was similar to population norms, but significantly worsened over time, although it was not significantly different than population norms15 at day 180. Symptoms of anxiety are common among caregivers of cancer patients receiving cellular therapies such as hematologic cell transplant and are associated with uncertainty about the patient health status.34 Interestingly, changes in anxiety were not associated with patient clinical characteristics. Previous studies have found caregivers' anxiety to be associated with patients' worse physical well-being and treatment-related complications.35 The increase in anxiety in this study may be due to caregivers concerns about future relapse after CAR T-cell therapy, although this relationship should be evaluated in future studies.

Prior to infusion, CAR T-cell therapy caregivers reported more caregiving burden than those caring for patients with early Alzheimer's disease and heart failure.20,21 In contrast, caregivers of CAR T-cell therapy patients whose disease responded to treatment did not differ in caregiving burden when compared to other populations of caregivers.20-26 These data suggest that caregivers' experience with CAR T-cell therapy may have a lingering impact, even for those whose who cared for patients with disease response. Caregivers of CAR T-cell therapy patients whose disease did not respond to treatment reported more caregiving burden at day 90 than caregivers of patients with early Alzheimer's disease, advanced breast cancer, heart failure and inflammatory bowel disease,20,21,23,24 and more burden at day 180 than caregivers of patients with early Alzheimer disease, heart failure, and inflammatory bowel disease.20,21,24 The wide confidence intervals of caregiving burden in caregivers of patients whose disease did not respond to treatment suggests there may be additional factors contributing to caregiving burden in these caregivers, such as having had caregiving help or trading off caregiving responsibilities with other family members. In general, comparisons of CAR T-cell therapy caregivers to other caregiving populations should be interpreted with caution, as small cell sizes may have contributed to variability.

Worse patient health status was associated with worse caregiver outcomes. For instance, lower baseline KPS was associated with increases in depression from baseline to day 180, as well as with treatment-related distress at day 180. To place these findings in context, a difference of 0.5 SD is generally considered clinically significant,16 which corresponds to a difference score of 5 points on the PROMIS-29 and 5 points on the Impact of Events Intrusion subscale. Patient clinical variables were associated with differences between 10 and 14 points in caregiver outcomes, well beyond the threshold for clinical significance, underscoring the importance of patients' health on caregivers' well-being. Baseline caregiver quality of life (i.e., physical function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression) and caregiving burden were significantly associated with caregiver outcomes at day 90 or 180. Notably, baseline levels of caregiver outcomes accounted for up to 61% of variance in later caregiver outcomes. These data suggest that early identification and referral to appropriate support is needed for this particularly vulnerable group of caregivers.

4.1 ∣. Study limitations

Study limitations should be noted. Because CRS and neurotoxicity occur during the first 30 days,36 a first post-treatment assessment at 90 days may have missed important clinical events that impacted caregiver outcomes. Additional follow-ups beyond 180 days are also needed to examine longer-term effects of CAR T-cell therapy on caregiver outcomes. The study did not collect data on the relationship between patients and caregivers (e.g., spouse, adult child, and other), the amount of time caregivers provided care, nor whether caregivers shared caregiving responsibilities with others. These are important variables to assess in future studies of CAR T-cell therapy caregivers. In addition, the study was conducted in two parts and a significant number of caregivers who consented to Part I declined participation in Part II. There were no baseline differences between caregivers who did and did not consent to Part II. Anecdotally however, several caregivers of patients who were doing well declined to continue in the study because they no longer considered themselves to be caregivers. This observation suggests the role of some CAR T-cell therapy caregivers may be transient, in contrast with other populations, such as hematopoietic cell transplant caregivers.34 Moreover, the study was conducted at a single institution in the United States, in a sample that was primarily white and non-Hispanic. Additional research is needed in more diverse samples of CAR T-cell therapy caregivers. In summary, this study was intended to be an initial overview of the experience of CAR T-cell therapy caregivers. Future studies should follow up on these findings to examine caregivers' self-care in the CAR T-cell therapy context, investigate why caregivers' anxiety increases over time, and develop interventions accordingly.

4.2 ∣. Clinical implications

Results highlight the need to address caregiver well-being when providing clinical care to CAR T-cell therapy recipients. Notably, for almost all outcomes the strongest predictor of outcomes at days 90 and 180 were baseline levels of the same outcome. These data suggest that early intervention with caregivers, even prior to CAR T-cell therapy, is appropriate and may have beneficial longer-term effects. Caregivers of cancer patients are less likely than patients to use mental health services37 and to receive guideline-concordant mental health treatment,38 despite high levels of distress. Further studies are needed to determine whether interventions tailored to CAR T-cell therapy caregivers should be developed. In the meantime, CAR T-cell therapy programs should consider screening for caregiver distress and refer caregivers to psychosocial resources as appropriate.

5 ∣. CONCLUSIONS

This study provides a first look at quality of life and other outcomes among caregivers of CAR T-cell therapy recipients, a novel cancer population. Results indicate pain, anxiety, caregiving burden, and treatment-related distress are concerns for some caregivers. Future studies are warranted to further evaluate these findings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23 CA201594; P30 CA762292, T32 CA090314), and a 2017 Moffitt Team Science Award. This work has been partially supported by the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement Core Facility at the Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the abovementioned parties.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Jain: Consultant for Kite/Gilead and Novartis; Locke: Scientific Advisor: Kite, Novartis, BMS/Celgene, Allogene, Amgen, Calibr, Wugen, GammaDelta Therapeutics. Consultant: Cellular BioMedicine Group Inc. Research Funding: Kite. Jim: Consultant for RedHill Biopharma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. There are no other conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Deidentified data upon which the current manuscript is based are available upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perica K, Curran KJ, Brentjens RJ, Giralt SA. Building a CAR garage: preparing for the delivery of commercial CAR T cell products at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(6):1135–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, Currow D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beattie S, Lebel S. The experience of caregivers of hematological cancer patients undergoing a hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a comprehensive literature review. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(11):1137–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roeland E, LeBlanc T. Effect of Palliative Care Engagement in the Era of Immunotherapy American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care Quarterly; 2017. Accessed June 3 2020. http://aahpm.org/quarterly/summer-17-feature [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buitrago J, Adkins S, Hawkins M, Iyamu K, Oort T. Adult Survivorship: considerations following CAR T-cell therapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(2):42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw BE, Syrjala KL, Onstad LE, et al. PROMIS measures can be used to assess symptoms and function in long-term hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Cancer. 2018;124(4):841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware J, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen T, Chin J, Ashby LM, Hakim R, Paserchia LA, Szarama KB. National Coverage Determination for Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy for Cancers. Baltimore, Maryland: CMS.gov. editor Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Schalet BD, Cella D. PROMIS-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(7):1885–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi S, Podrabsky R, McKinney N, Schalet BD, Cook KF, Cella D. PROsetta Stone ® Methodology: A Rosetta Stone for Patient Reported Outcomes. Chicago, IL: Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/reference-populations. Accessed June 6 2020.

- 16.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life. Medical Care. 2003;41(5):582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6): 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41(3):209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cella DF, Mahon SM, Donovan MI. Cancer recurrence as a traumatic event. Behav Med. 1990;16(1):15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson RL, Rentz DM, Bruemmer V, et al. Observation of patient and caregiver burden associated with early Alzheimer's disease in the United States: design and baseline findings of the GERAS-US cohort Study1. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72(1):279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung ML, Pressler SJ, Dunbar SB, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Predictors of depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(5):411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004;170(2):1795–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parekh N, Shah S, McMaster K, et al. Effects of caregiver burden on quality of life and coping strategies utilized by caregivers of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterology. 2017;30(1):89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badr H, Federman AD, Wolf M, Revenson TA, Wisnivesky JP. Depression in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their informal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(9):975–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen D, Chao D, Ma G, Morgan T. Quality of life and factors predictive of burden among primary caregivers of chronic liver disease patients. Ann Gastroenterology. 2015;28(1):124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nastoupil J, Jain M, Feng L, et al. Standard-of-Care Axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: results from the US lymphoma CAR T consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(27):3119–3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortego G, Villafañe JH, Doménech-García V, Berjano P, Bertozzi L, Herrero P. Is there a relationship between psychological stress or anxiety and chronic nonspecific neck-arm pain in adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosomatic Res. 2016;90:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones SL, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Janzen JA, Hadjistavropoulos T. The relation of pain and caregiver burden in informal older adult caregivers. Pain Med 2011;12(1):51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivey K, Allen RS, Liu Y, Parmelee PA, Zarit SH. Immediate and lagged effects of daily stress and affect on caregivers' daily pain experience. Gerontologist. 2018;58(5):913–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(4):398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the United States 2020. Washington, DC: AARP; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jim HSL, Quinn GP, Barata A, et al. Caregivers' quality of life after blood and marrow transplantation: a qualitative study. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2014;49(9):1234–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langer SL, Yi JC, Chi N-C, Lindhorst T. Psychological impacts and ways of coping reported by spousal caregivers of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a qualitative analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karschnia P, Jordan JT, Forst DA, et al. Clinical presentation, management, and biomarkers of neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CAR T cells. Blood. 2019;133(20):2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litzelman K, Keller AO, Tevaarwerk A, DuBenske L. Adequacy of depression treatment in spouses of cancer survivors: findings from a nationally representative US Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6): 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data upon which the current manuscript is based are available upon request from the corresponding author.