Abstract

Evidence of doulas’ positive impacts on maternal health outcomes, particularly among underserved populations, supports expanding access. Health workforce-related barriers challenge the development of robust doula services in the United States. We investigated organizations’ barriers regarding training, recruitment, and employment of doulas. We conducted literature and policy reviews and 16 semi-structured interviews with key informants who contribute to state policymaking and from organizations involved in training, certifying, advocating for, and employing doulas. Our study shows barriers to more robust doula services, including varying roles and practices, prohibitive costs of training and certification, and insufficient funding. This study underscores the importance of doulas in providing support to clients from underserved populations. Health workforce-related challenges remain, especially for community-based organizations seeking to serve underserved communities.

Keywords: doulas, health equity, health access, community-based doulas

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and child health outcomes in the United States are pervasive and persistent. Non-Hispanic Black people, American Indians, and Alaska Natives, in comparison to non-Hispanic White people, have higher rates of cesarean surgeries and are three to four times more likely than White people to die during the perinatal period regardless of socioeconomic status. They report higher rates of preterm birth and postpartum depression, have lower rates of breastfeeding, and tend to be less satisfied with the communication with their medical providers in the perinatal period (CDC, 2019; National Partnerships for Women and Families, 2018; National Partnerships for Women and Families, 2019; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2020).

Birth doulas can serve important roles in improving birth outcomes, particularly among underserved populations (Thomas et al., 2017; Bohren et al., 2017). Birth doulas provide continuous assistance during labor, offering physical, emotional, and informational support as clients navigate care during the perinatal period (Kozhimannil et al., 2013). Despite the benefits birth doulas provide, their care remains underutilized, particularly among low-income pregnant persons and people of color (Kozhimannil et al., 2014). Prohibitive out-of-pocket costs and lack of availability can make culturally competent doula care inaccessible to populations who would benefit most from their services (Kozhimannil et al., 2013).

Due to growing evidence of doulas’ positive impact on birth outcomes, researchers and policymakers have pressed to expand access to doula services (Ballen & Fulcher, 2006). Previous research has focused on the challenges that individual doulas face in their work. Doulas are typically private, independent paraprofessionals who offer high quality services, but few doulas can secure a stable income. Many insurance providers do not cover birth doula services (Lantz et al., 2005). Training and employment organizations are crucial components in shaping doula care as they develop curricula, set national standards and certification criteria, aid in expanding reimbursement policies, and recruit doulas to work in underserved communities. Despite the important roles that organizations play in shaping the field of doula care from a public health perspective, their role and impact on expanding access to doulas services has been understudied. Our study aims to fill the gap in knowledge about the role of organizations in providing access to doulas through training and employment, contributing to reducing birth disparities in underserved communities. This study offers a high-level descriptive overview of the landscape of organizations involved in training, recruiting, and employing doulas. Its results show that organizations’ differential approaches to training and employment, plus their varied positionalities to contribute to future policy that shapes the future of doula services in the United States, complicates efforts to alleviate underserved communities’ barriers to quality birth doula services.

METHODS

For this descriptive study, we reviewed published and grey literature on birth doulas in the United States. Through web searches and reviewing key reports, we identified over 200 organizations across the United States involved in doula care. These were organizations that: train or certify birth doulas; employ doulas across a variety of work environments; and are involved in research, policy, or advocacy for doulas. Our list included training and certifying organizations, hospitals, and community-based doula organizations in underserved communities. We also sought input from experts familiar with key policy issues related to doula scope of practice and financial reimbursement.

We conducted 16 (of 37 invited for an interview), semi-structured, 60-minute interviews with key informants representing a variety of perspectives and experiences from March to August 2020. We interviewed executive directors, program directors, or other high-level individuals within the organizations of interest. We asked how organizations describe the role and scope of doula work; how they recruit doulas; the core competencies they cover in training; the skills and competencies they require for doulas working in underserved communities; and the barriers and challenges facing organizations and the doula workforce. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

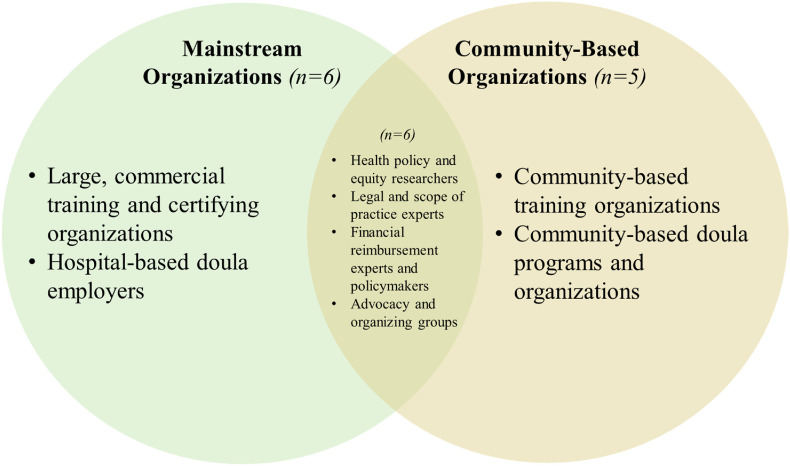

We used qualitative software to analyze interview transcripts using thematic analysis. Research team members independently read transcripts to identify potential themes. Informed by research and interview questions, codes were reviewed and finalized together, producing major themes and sub-themes. Based on our data collection and analysis, organizations often fell into two prevailing conceptual classifications (Figure 1). One classification included organizations that view doulas as part of the mainstream US healthcare system and are involved in training, certifying, and employing doulas within hospital-based settings. Six such “mainstream” organizations were interviewed, including: four commercial training organizations and two hospital-based doula employers. The other classification included organizations involved in training, certifying, and/or employing doulas who are rooted in underrepresented communities to work outside of the hospital-based system, which we refer to as “community-based organizations” (CBOs). We interviewed five CBOs: two which provided doula training, two which trained and employed doulas, and one which employed doulas (but did not provide training), all specific to work in community settings. We also interviewed six experts in the legal, policy, and financial reimbursement aspects of the profession, which we classified as working at the intersection of mainstream and community-based organizations.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for interviewee classification.1.

Note. The number of interviewees in each category exceeds the number of total interviews conducted as some individuals spanned multiple categories.

RESULTS

How Do Organizations Train Doulas?

Defining a Doula

The largest doula certification organization worldwide, DONA, defines a doula as a non-clinical “trained professional who provides physical, emotional, and informational support to a pregnant person and their support people before, during and shortly after childbirth to help them achieve the healthiest, most satisfying experience possible” (Dona International, n.d.). Interviewees across organizations cited this definition and stressed the importance of training doulas on physiological childbirth, basic breastfeeding and childbirth education, and effective support of clients and their families. Yet organizations’ trainings and their content, duration, scope, and price differed drastically, in part because, as of 2020, the United States does not have any national guidelines for training doulas (Chen, n.d.).

A Diverse Doula Landscape of Training, Recruitment, and Funding

As described earlier, organizations in our sample fell into two main categories and as such, encompassed different training, certification, and recruitment approaches. Mainstream organizations train, certify and/or employ doulas to work primarily in hospital-based environments. The two mainstream training organizations interviewed also provided an optional certification for doulas to pursue and did not employ individual doulas. The two mainstream employer organizations tended to exclusively hire doulas who came from mainstream training organizations, with a preference for certified doulas.

With respect to the CBOs in our sample, the two that both trained and employed doulas to work in their communities offered a full training for new doulas or additional education to doulas who had already completed training with a mainstream organization. CBO doula employers placed less of an emphasis on certification as a hiring qualification. Overall, these different stances toward training, certification, and recruitment illustrate the diversity of the organizational doula landscape.

Diversity in Training, Curricula, and Requirements

Without national standards or accreditation for birth doulas, trainings and topics covered varied widely. Often the individual doula must decide which training best aligns with their background and career goals. Training components across mainstream organizations include communication, pregnancy, and birth physiology, how to be a birth doula, and entrepreneurship and business skills (Childbirth International, 2019). Their training workshops were typically 3 days, or 26–28 hours long, and cost between $350 and $1,000 (Childbirth International, 2020). For example, a standard curriculum may focus on six principal areas of competency: ethics and professionalism, cultural competency, communication skills, practice (through teaching, supporting, and counseling skills), leadership (skills around advocating for clients’ needs), and wellbeing (skills relating to self-care and business sustainability) (Childbirth International, 2019).

Interviewees from mainstream organizations often focused on training doulas to work in hospital settings, emphasizing inter-professional communication and collaboration with hospital delivery teams. Our interviews and curricula review showed that many mainstream training organizations set a core curriculum focused on specific competencies and skills but allowed independent doula trainers to determine what to emphasize in their trainings.2 As such, trainers working for these organizations had the authority and flexibility to assign more reading or spend more time on the physiological aspects of birth and less time on entrepreneurship, the history of labor support in the United States, or cultural competency. Other mainstream organizations had standardized their training curricula across trainers within their organizations.

Smaller mainstream training organizations offered longer, three- to seven-month training courses, with an option for certification. In these trainings, doula trainers had more flexibility to assign more background reading and hold more in-depth discussions of the physiology of childbirth. They could also provide more hands-on simulation of how a doula can support their clients during labor and delivery, offer practice scenarios of pregnancy and post-partum visits, and teach trainees about the history of labor support in the United States and its impact on marginalized communities and how doulas can best support clients from those communities.

CBOs that trained doulas, in addition to covering topics of childbirth, breastfeeding, and childbirth education, emphasized education on the life course approach, trauma-informed and culturally responsive care, and approaches to reducing gaps in health equity through doula services. One interviewee from a training CBO explained the range of topics in their training curriculum,

[Our doulas are] engaged in the prenatal period, labor and delivery, postpartum period, and breastfeeding education… aspects of family planning and making sure we’re providing advocacy and education…so [clients can] navigate when they’re not able to have their doula with them.

Interviewees of CBOs that trained doulas were critical of the larger training organizations and what they interpreted as these organizations’ limited curricula. Some interviewees argued that a weekend workshop was the bare minimum, and that doulas should receive more training tailored to the needs of specific communities and environments, especially communities of color and other underserved populations.

Certification

As of 2020, certification is not mandated for doulas to practice, but it is required under some Medicaid and private insurance reimbursements (Platt & Kaye, 2020). A doula need not stay with the same organization from training to certification, but often does (DONA International, 2019). Certification often requires additional training, including the completion of reflection essays, physiology exams, reflections on attended births; evaluations from medical personnel or other birth attendants for those births; additional fees for training; and service hours or job shadowing (DONA International, 2019; Childbirth International, n.d.). Certification can take from three months to a year and cost thousands of dollars if a doula receives a mentor or shadows a professional doula on the job. The time doulas invest for certification is often unpaid. In some cases, a training/certification organization oversees the certification, offering mentorship and support. In others, a doula is on their own. Organizations across the two types offered certification as an option for doulas who had completed their respective trainings, but mainstream organizations in our sample placed greater importance on certification than CBOs. For example, some mainstream doula organizations saw certification as a means of validation for doulas working in hospital-based environments. Interviewees from CBOs were hesitant around over-emphasizing the importance of certification due to concerns over increasing financial barriers for doulas entering the field and mainstream organizations having the potential to set the scope of practice for birth doulas without much input from CBOs and other smaller training organizations.

How Do Organizations Recruit Doulas for Training and Employment?

Recruitment into Training

Interviewees from mainstream organizations said they relied on word-of-mouth and advertisements on social media to recruit doulas for training. They emphasized that their training cohorts came from “every single background that you can imagine (…) something they have in common is that something lit a spark in them for helping with births.” Other interviewees from mainstream organizations stated that trainees’ goals as a doula ranged from assisting friends and family to wanting to start and grow their own business or work to serve their own communities’ needs. Mainstream organizations interviewed did not require skills or specific backgrounds as prerequisites for recruitment.

Interviewees from mainstream training organizations mentioned several ways they aimed to diversify recruitment because birth doulas have been and have catered to predominantly White, and middle-class pregnant women and many interviewees across organization type indicated that this is still primarily the case but shifting (Kozhimannil et al., 2013). One organization hoped to diversify their trainer population and training locations to reach and enroll more members of underrepresented and marginalized communities. Other mainstream organizations had partnered with either community-based social and health services organizations and/or CBOs with doula services to advertise and offer scholarships to individuals from diverse backgrounds and communities, but those few scholarship opportunities were not well advertised.

CBOs that train doulas used their community connections to recruit doulas, often through word-of-mouth. In contrast to mainstream organizations, these organizations looked for prospective doulas who had lived experiences as a member of an underserved group or had worked with the organization’s target communities and were committed to the organization’s mission. One interviewee explained,

The prerequisite is your mindset and commitment to the work and to your ability and capacity to learn. There’s also the prerequisite of being Black. We are an unapologetically Black organization dedicated to addressing Black families and the health in our communities.

Recruitment Into Employment

Organizations in our sample also reflected different approaches to recruit doulas into employment. Mainstream employment organizations when hiring doulas typically looked to hire doulas with formal doula education and training, often requiring certification from a mainstream certification organization and previous experiences attending births. They often required doulas to be on-call during labor and birth and work with a set schedule of pregnancy and postpartum appointments. Of the hospital-based organizations interviewed, one stated that their model is like that of other doula agencies in that their doulas work schedules that are based on patient load and organized in shifts. The doulas in this organization did not have individual clients but attended to a broad patient base during their shift. For mainstream employer organizations, these requirements for shift work and being on call were often secondary to a candidate’s relational skills, communication style and potential to work collaboratively within hospital systems and medical care teams. One interviewee from a mainstream employer organization mentioned,

One of the answers we’re looking for [when hiring] is—can this doula be a collaborative and collegial member of a maternity care team? We’re looking for someone whose primary interest and responsibility is the emotional wellbeing of the client and at the same time can work with other care providers.

When hiring, CBOs focused on serving specific underserved and minority communities and providing doula services that fit communities’ needs. CBOs were looking for doulas who had lived experience as a member of that community or had deep ties to that community. Doulas needed to be committed to improving health equity and health outcomes through their work and be able and willing to invest time helping clients and their families navigate this system throughout the perinatal period (whereas birth doulas typically attend two visits during pregnancy, labor, and birth, and two postpartum visits). After hiring, CBOs often provided new doulas additional on-the-job or specialized training to educate them on the specific health, communication, and support needs of their communities.

How Do Organizations Employ Doulas and Fund Their Programs?

The organizations in our sample had different employment arrangements for birth doulas, ranging from using unpaid volunteers to independent contractors and salaried employees. Some interviewed mainstream hospital-based organizations employed their doulas through unpaid volunteer agreements. Interviewees from CBOs tended to highlight the need to pay doulas a fair and living wage as part of their organization efforts to improve equity for clients and workers. They emphasized the need to pay doulas wages at or above market value. Yet these organizations often struggled to find the resources to cover their doulas’ wages. Like some mainstream organizations interviewed, CBOs employed their doulas through salaried or independent contract work.

Interviewees across organization types reported struggling to raise sufficient funds to run their programs, recruit and hire new doulas, and invest in already-employed doulas through increasing wages, reimbursement for services, and professional development. Most organizations relied on multiple, smaller, and irregular grants and local agreements with managed care organizations or took on private-pay clients to subsidize low-income clients. Some mainstream employer organizations subsidized their programming for low-income or underserved populations by charging high income clients a higher fee-for-service rate. CBOs financed their operations and wages through external grant funding from private and public sources, other fee-for-service programs, and Medicaid reimbursement where available. One community-based doula organization used payments for speaking engagements to cover program costs and doula wages. The patchwork of funding sources added an additional barrier to many organizations interviewed that sought to expand access to and utilization of birth doula services. One interviewee said, “We just need a more diverse funding source for security. There are doulas out there to hire, but I need the money to hire more doulas.”

To expand coverage for doula services, some organizations and policy makers have turned to public funding through Medicaid.3 As of 2020, only Oregon and Minnesota offer reimbursement under their public Medicaid programs, which can help pregnant persons utilize otherwise unaffordable services while reducing costs on state and national levels (Thomas et al., 2017; Chen, n.d.). However, interviewees familiar with Medicaid policies stressed that seeking Medicaid reimbursement may trigger additional barriers. In Oregon, one interviewee said, doulas must take a community health worker training that costs $600–800 dollars, which can be prohibitive for those already struggling to pay for training and certification. Other interviewees stressed that the reimbursement process is complicated and that the current reimbursement rate is too low to cover the costs of multiple visits and ensure birth doulas a living wage. Interviewees said that low reimbursements rates may lead independent doulas to turn down Medicaid clients, which is a fundamental problem for organizations and doulas who want to serve underserved populations that would benefit most from doula support (Kozhimannil et al., 2014).

DISCUSSION

This study shows the diversity of organizations involved in doula training and certification, different strategies organizations employ to recruit prospective doulas, and different employment models that organizations use. Our study showed that doula training components such as: requirements for training course material, time commitments, core competencies, and certification, all varied. Mainstream training and certifying organizations offered shorter training courses to equip doulas for a variety of work environments, often hospital settings, typically incorporating into their curricula entrepreneurship and business skills. CBOs started their own, often longer programs that, in addition to topics of childbirth, breastfeeding, and childbirth education, also focused on racial and reproductive justice and health inequities.

Organizations differed in their views of the preferred doula’s position in the health-care system. Mainstream organizations positioned birth doulas often, although not exclusively, in hospital settings where they were to collaborate within birth teams. CBOs, in contrast, placed birth doulas squarely in community settings, such as in people’s homes or birth centers, to better serve the communities impacted by systemic racism and facing structural barriers when seeking access to the US health system. These different views translate into a range of doula training, recruitment, and employment strategies.

The fragmented doula landscape indicates that organizations differ in their ability to shape the future of birth doula services in the US. Mainstream organizations can draw on greater resources, established infrastructure, and prestige to advocate for coverage and directly converse with politicians on state and federal levels. Moreover, these organizations were frequently cited in legislation, but do not necessarily employ doulas and can be further removed from the challenges that individual doulas experience in the field (Chen, n.d.; Gebel & Hodin, 2020). Smaller, community-based organizations may lack the infrastructure, material resources, and institutional stature to advocate for coverage. They are less visible and may less often be called upon to offer expertise in working with underserved populations. These differences in ability to inform state and national policy and decision-making, in turn, impact what policymakers construe as appropriate reimbursement rates or scope of practice. For instance, some interviewees argued that early efforts to expand doula services through Medicaid reimbursement did not involve diverse stakeholder groups. Many interviewees from CBOs reported feeling excluded from decision-making around reimbursement rates, required competencies, and qualifications.

Limitations

We did not focus on the work of individual doulas or interview working doulas. Our focus was the perspective of organizations that train and employ doulas to work in underserved communities. Individual doulas would be able to provide an additional perspective on the barriers and challenges they face in serving underserved communities as well as comment on their training, recruitment, and employment situations. Our study does not offer a full representation of the organizations involved in training, employing, and advocating for doulas. We had an overrepresentation of interviewees from the Pacific Northwest and New England. This was mainly due to convenience and the number of organizations located in these areas. Our aim was not to offer precise representation, but to explore the barriers and challenges organizations face when seeking to provide and expand doula services in the US.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The diverse doula and funding landscape, plus organizations’ differential positionalities to provide meaningful input on the future of doula services in the United States, complicates efforts to lessen underserved communities’ barriers to quality birth doula services. Mainstream training organizations have a wide network and offer training and recruit trainees across states. They also shape public policies and advocate for coverage. Yet, in our study, interviewees from mainstream organizations were least likely to mention that they specifically targeted underserved communities in their recruitment efforts, although some were trying to diversify their trainers and curricula. CBOs, in contrast, often worked locally and recruited trainees from the underserved communities that they identified as in need of doula services. Addressing health inequities and reducing systemic barriers were key foci in their often-tailor-made training programs. However, these organizations, like smaller training organizations, struggled to secure the funding on top of running their training, hiring doulas, offering continuing education to their existing doulas, and providing quality birth doula services. These struggles, and other workforce-related barriers we identified in our study, can compound barriers that community-based doulas and their underserved communities already experience in accessing hard-to-reach services. Future work is needed to better position and support CBOs in contributing to federal and state policies to expand doula services and to ensure equitable access in all communities.

Non-Hispanic Black people, American Indians, and Alaska Natives, in comparison to non-Hispanic White people, have higher rates of cesarean surgeries and are three to four times more likely than White people to die during the perinatal period regardless of socioeconomic status.

Birth doulas can serve important roles in improving birth outcomes, particularly among underserved populations.

Doulas needed to be committed to improving health equity and health outcomes through their work and be able and willing to invest time helping clients and their families navigate this system throughout the perinatal period.

The diverse doula and funding landscape, plus organizations’ differential positionalities to provide meaningful input on the future of doula services in the US, complicates efforts to lessen underserved communities’ barriers to quality birth doula services.

As of 2020, only Oregon and Minnesota offer reimbursement under their public Medicaid programs.

Biographies

MARIEKE S. VAN EIJK is an Associate Teaching Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA (USA).

GRACE A. GUENTHER is a Research Scientist in the Center for Health Workforce Studies, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

ANDREW D. JOPSON is a Research Scientist in the Center for Health Workforce Studies, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

SUSAN M. SKILLMAN is a Research Scientist and Senior Deputy Director in the Center for Health Workforce Studies, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

BIANCA K. FROGNER is a Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Director in the Center for Health Workforce Studies, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Footnotes

For mainstream organizations, there was very little or no overlap between organizations that train doulas and organizations that employ doulas to work in hospital-based settings. For community-based organizations, we often found overlap between organizations that train doulas and those that employ doulas to work in community-based settings.

Due to privacy and consent concerns, we are not mentioning the names of these organizations. We retrieved this information through web searches and interviews.

A few private insurers cover doula services.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant financial interest or affiliations with any commercial interests related to the subjects discussed within this article.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $450,000 with zero percentage financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/manage/acknowledge-hrsa-funding.

REFERENCES

- Ballen, L. E., & Fulcher, A. J. (2006). Nurses and doulas: Complementary roles to provide optimal maternity care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN, 35(2), 304–311. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, M. A., Hofmeyr, G. J., Sakala, C., Fukuzawa, R. K., & Cuthbert, A. (2017). Continuous support for women during childbirth. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD003766–CD003766. 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2019, September 6). Racial and ethnic disparities continue in pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html

- Chen, A. (n.d.). Doula Medicaid Project. National Health Law Program. https://healthlaw.org/doulamedicaidproject/ [Google Scholar]

- Childbirth International. (2019). Birth doula syllabus. https://childbirthinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Birth-Doula-Syllabus.pdf

- Childbirth International. (n.d.) Birth doula training and certification. https://childbirthinternational.com/birth-doula

- Childbirth International. (2020). Comparison of birth doula training programs. https://childbirthinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Birth-Doula-Comparison.pdf

- DONA International. (n.d.). What is a doula? https://www.dona.org/what-is-a-doula/

- DONA International (2019). Birth doula certification: A Doula’s Guide [PDF file]. https://www.dona.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Certification-Overview-Birth-1-20.pdf

- Gebel, C., & Hodin, S. (2020; January 8). Expanding access to doula care: State of the union [Maternal Health Task Force]. Maternal Health Task Force. https://www.mhtf.org/2020/01/08/expanding-access-to-doula-care/

- Kozhimannil, K. B., Attanasio, L. B., Jou, J., Joarnt, L. K., Johnson, P. J., & Gjerdingen, D. K. (2014). Potential benefits of increased access to doula support during childbirth. The American Journal of Managed Care, 20(8), e340–e352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K. B., Hardeman, R. R., Attanasio, L. B., Blauer-Peterson, C., & O’Brien, M. (2013). Doula care, birth outcomes, and costs among Medicaid beneficiaries. American Journal of Public Health, 103(4), e113–e121. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, P. M., Low, L. K., Varkey, S., & Watson, R. L. (2005). Doulas as childbirth paraprofessionals: Results from a national survey. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 15(3), 109–116. 10.1016/j.whi.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottl-Santiago, J., Herr, K., Rodrigues, D., Walker, C., Walker, C., & Feinberg, E. (2020). The birth sisters program: A model of hospital-based doula support to promote health equity. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 31(1), 43–55. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Partnership for Women and Families. (2019). American Indian and Alaska Native women’s maternal health: Addressing the crisis [PDF file]. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/american-indian-and-alaska.pdf

- National Partnership for Women and Families. (2018). Black women’s maternal health: A multifaceted approach to addressing persistent and dire health disparities. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/black-womens-maternal-health-issue-brief.pdf

- Platt, T., & Kaye, N. (2020). Four state strategies to employ doulas to improve maternal health and birth outcomes in medicaid – The national academy for state health policy. National Academy for State Health Policy. https://www.nashp.org/four-state-strategies-to-employ-doulas-to-improve-maternal-health-and-birth-outcomes-in-medicaid/

- Thomas, M.-P., Ammann, G., Brazier, E., Noyes, P., & Maybank, A. (2017). Doula services within a healthy start program: Increasing access for an underserved population. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(Suppl 1), 59–64. 10.1007/s10995-017-2402-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]