Abstract

Background:

Desistance is a concept that has been poorly defined in the literature, yet greatly impacts the arguments for and against providing gender-affirming care for transgender and gender expansive (TGE) youth. This literature review aims to provide an overview of the literature on desistance and how desistance is defined.

Methods:

A systematically guided literature review was conducted on March 27, 2020, using CINAHL, Embase, LGBT Life, Medline, PsychINFO, and Web of Science to identify English language peer-reviewed studies, editorials, and theses that discuss desistance concerning TGE pre-pubertal youth for a minimum of three paragraphs. Articles were divided based on methodology and quantitative data were quality assessed and congregated. Definitions of desistance were compiled and analyzed using constant comparative method.

Results:

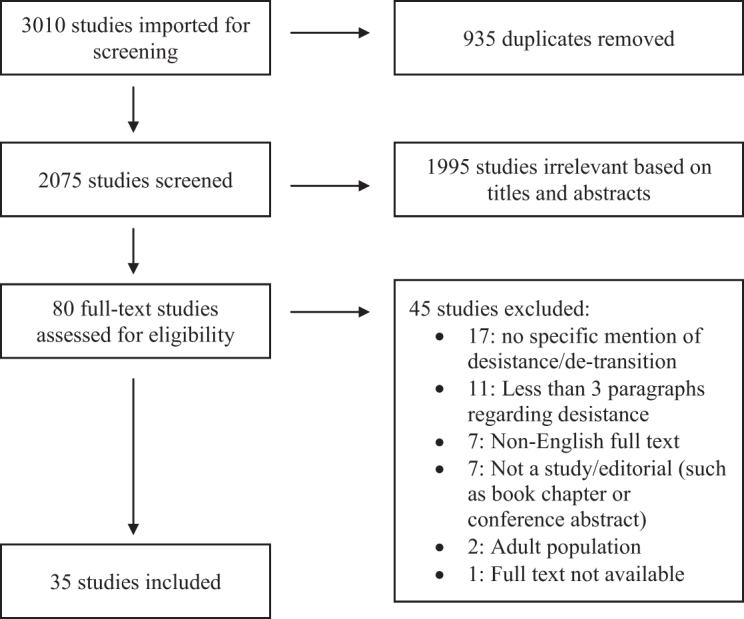

One qualitative study, 2 case studies, 5 quantitative studies, 5 ethical discussions, and 22 editorials were assessed. Quantitative studies were all poor quality, with 83% of 251 participants reported as desisting. Thirty definitions of desistance were found, with four overarching trends: desistance as the disappearance of gender dysphoria (GD) after puberty, a change in gender identity from TGE to cisgender, the disappearance of distress, and the disappearance of the desire for medical intervention.

Conclusions:

This review demonstrates the dearth of high-quality hypothesis-driven research that currently exists and suggests that desistance should no longer be used in clinical work or research. This transition can help future research move away from attempting to predict gender outcomes and instead focus on helping reduce distress from GD in TGE children.

Keywords: transgender and gender expansive youth, desistance, gender identity, barriers to care

Introduction

There is a large debate regarding which gender-affirming care (GAC) services should be provided to transgender and gender expansive (TGE) youth, especially around social transition and puberty blockers,1–6 despite most aspects of GAC being the Standard of Care according to international organizations such as World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH).7–9 A central part of the debate is harm: is more harm done by providing GAC, or by watchful waiting, an approach that advocates observing a child's gender journey to see how the child's gender identity and expression evolve?10–12 Proponents point to the beneficial mental health impact of social transition and using puberty blockers, as well as the reversible nature of interventions and the previous, well documented, use of puberty blockers in the management of the pathological condition precocious puberty.6,13 Critiques of puberty blockers point to the lack of rigorous research surrounding the intervention on physiologically healthy children, research that shows decreased fertility preservation in children who commenced puberty suppression, and finally the idea that puberty is a time of gender consolidation and that beforehand, it is impossible to make a diagnosis of “true” gender dysphoria (GD) as gender often fluctuates.1,4,5,10

A qualitative study conducted by Vrouenraets et al. of 17 treatment teams for TGE youth found 7 main domains relating to physician concerns surrounding puberty blockers.14 These include (1) ambiguity on the etiology of GD; (2) confusion around whether GD is a mental disorder or normal variation; (3) possible influence of puberty on gender; (4) the presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions; (5) possible harm from the treatments; (6) the decisional capacity of children; and (7) the portrayal of immediate treatment for GD in media and society as the answer for all problems.15 A sense of confusion or uncertainty is apparent in almost all of the seven domains, highlighting the discomfort that can surround this treatment.

An unspoken component of these arguments is desistance.16 While a standard definition of desistance does not appear to exist,7,17 desistance alludes to the idea that GD or a TGE identity in pre-pubertal children will either “persist” through puberty or will “desist,” and the child will no longer have GD/a TGE identity after puberty. Articles from the 1960s to 1980s are often cited as the foundation for research on “desistance.”18–21 One of the most significant studies is from a book published by Richard Green in 1987 entitled “The ‘Sissy Boy Syndrome’ and the Development of Homosexuality.”22

Despite being the foundation for desistance research, these early articles and books never mention desistance, rather focusing on the “gender deviant” behavior of femininity in people designated male at birth, and how this behavior is more often a predictor of homosexuality rather than “transsexualism.”18–21 No one designated female at birth was included in the studies conducted at this time, and all of these studies employed techniques to actively decrease the gender-deviant behavior, leading to psychological trauma for many of the participants.23 Furthermore, gender was still considered a binary construct since the first published use of genderqueer did not emerge in print until the late 1980s, early 1990s in activist groups.24,25

As language continuously evolves around gender, more modern research has begun to explore the experiences of nonbinary and gender expansive youth, although this area of experience is still very understudied and research often is not up to date with the most current understandings of gender identity and gender expression.26 These early studies also set a link between sexual orientation and gender identity, two distinct concepts with no overlap outside of societally enforced ideals.27

Desistance as a word has its origins in criminal research,28 and Zucker explains that he was the first person to use desistance in relation to the TGE pre-pubertal youth population in 2003 after seeing it being used for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).29 In either case, desistance is considered a good outcome in criminal research and ODD. Acknowledging this history of the term is important as it reflects the pathologizing of gender identity (in relation to ODD) and the negative perspectives that have been associated with being TGE (in relation to crime).

With the word desistance now introduced, the focus of the more recent literature in the late 2000s is interested in rates of desistance and determining childhood factors before puberty, which can be used to predict desistance after puberty commences,30–33 often seen as a way to help clinicians decide on whether GAC should be provided. From all of these collections of studies emerged the commonly used statistic stating that ∼80% of TGE youth will desist after puberty, a statistic that has been critiqued by other works based on poor methodologic quality, the evolving understanding of gender and probable misclassification of nonbinary individuals, and the practice of attempting to dissuade youth from identifying as transgender in some of these studies.4,16,34–36

Recently, several proposed bills in the United States and a completed court ruling in the United Kingdom have focused on regulating the care provided for TGE youth, preventing physicians from giving medical GAC, such as puberty blockers, to TGE youth younger than 16 or 18 years.37–39 This effectively makes puberty blockers illegal, as physiologic puberty commences before 13–14 years of age.40 These proposed bills tend to focus on two arguments: the first being that GAC medical services are harmful and the second being that these children will regret their decision to “poison their bodies” when they no longer experience GD after puberty.41

With the surge in attention to these children in legislation, the media, and medical journals,42 an increased scrutiny is warranted to recent research on desistance and how exactly it has been defined. The aim of this article is to elucidate how desistance is defined. This includes reviewing the existing literature on desistance and exploring how desistance has been defined.

Methods

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were set before starting the literature search. Studies were included if articles had been published as a peer-reviewed study, editorial, or thesis. Book chapters were not included as they did not have to undergo the peer review process, and conference abstracts were not included because there was not enough material to fully explore the themes around how desistance was defined. Any methodology (quantitative and/or qualitative) could be included.

Articles had to contain reference, either explicitly or implicitly, to desistance in the abstract, and at least three paragraphs, of any length, specifically discussing desistance in the full text. Three paragraphs were used as this provided clarity of how the authors defined and used the idea of desistance.

The words desistance, persistence, or detransition/de-transition had to be used in these paragraphs. Importantly, detransition (an umbrella term referring to the identity and actions of someone who identifies with their gender designated at birth and who previously identified as TGE) and desistance (a research term focusing on youth) are two distinct concepts with overlap, and detransition was included to catch the overlap.43 If there was no abstract, then only the three-paragraph rule was used. The study population had to be younger than 16 years for those designated male at birth, or 14 years for those designated female at birth, which marks the cutoff for delayed puberty.40

Literature discussing the additional considerations regarding GAC for neuro-atypical people was outside the scope of this review. Due to limited resources, only English language articles were considered. There was no time limit to studies included to ensure proper understanding of how desistance definitions evolved.

Search strategy

Six databases were chosen to search: MEDLINE® (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), LGBT Life (EBSCO), and Web of Science. These provide a comprehensive review of clinical, psychological, nursing, and LGBT articles.

A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE and adapted to the other databases. Truncations and wildcards were used throughout to ensure different spellings were captured.44 Wildcard involves the use of a symbol to capture different spellings (colo?r captures color and colour). Truncation uses a different symbol to search multiple variations on a word stem (color* captures color and colors). Three ideas were explored in the search strategy. The first idea revolved around TGE identity, the next idea focused on children, and the final idea focused on desistance (Table 1). The idea of desistance is inherently linked to children, making a section focusing on children possibly extraneous. However, desistance keywords, such as “discontinue,” “detransition,” or “persist,” have been applied to both pre-pubertal and older TGE individuals and therefore the inclusion of the childhood search was to ensure only articles concerning desistance in pre-pubertal children were identified. There are no subject headings relating to desistance to the author's knowledge.

Table 1.

Search Keywords Used in Systematic Review

| Transgender | Transgender* OR trans-gender* OR transvestite* OR trans-vestite* OR transsex* OR trans-sex* OR genderqueer OR two-spirit OR agender* Gender ADJ3 (incongruen* OR non-binary OR nonbinary OR diverse OR creative OR fluid OR variant OR bender OR non-conforming OR queer OR neutral) |

| Youth | Adolescen* OR child* OR youth* OR young* OR teen* OR young adult* OR young person* OR puberty OR pubescen* OR pre-pubescen* OR minor* OR underage* OR juvenile* OR pediatric* OR paediatric* |

| Desistance | Desist* OR discontinue OR detransition OR de-transition OR transition OR persist* |

While the keyword “transition” drastically decreased the specificity of the search, the contribution to the sensitivity was considered great enough to merit its inclusion. This was not true for LGBT Life, where the sensitivity also decreased with the addition of the word transition, and therefore, this was the only database in which “transition” was not included. All studies were transferred into Endnote X9 (Clarivate Analytics) and then uploaded into Covidence (Melbourne, Australia) for screening.

Study selection

Covidence programming was used to detect duplicates, which were checked by a single author due to limited resources and funding. Initial screening was conducted using titles and abstracts to determine those that appeared to discuss desistance. Desistance was considered to be referenced to in the abstract if there was direct mention of desistance/persistence, if there was mention of change in gender identification from children to adolescents or adults, or if the study considered the prediction of gender development. Discussion of the ethical considerations regarding GAC was not considered to reference desistance, unless explicitly stated, because there are many ethical considerations with treating minors, such as informed consent and fertility preservation.45

Screening at this stage was intentionally kept broad to ensure comprehensive selection. A full text screen was then performed using inclusion criteria. If a study was excluded during full text screening, the specific reason was documented.

Data analysis

Search results were separated into groups based on their methodology. These groups were as follows: quantitative hypothesis-driven research, qualitative hypothesis-driven research, case series, ethical discussions, and editorials (defined here as not hypothesis-driven, peer-reviewed articles) that discussed desistance. Articles in the editorial group were further divided. A article was considered a clinical perspective if it was based on the author's clinical experience, a critical analysis if it critiqued the literature, a review article if it provided an overarching exploration of the field, and a response article if it was written in response to another article.

The data from the quantitative research group were synthesized using total and weighted means. Since only one qualitative study was found, no synthesis was done.

The definitions of desistance from articles in all groups were compiled into a table to explore common themes using constant comparative method.46 The table also included whether the article explicitly defined desistance or if the definition was inferred. If inferred, language mirroring the author's original language was used.

Quality assessment

Follow-up studies were assessed as part of data synthetization using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, which was chosen for its focus on reporting and methodology.

There are 14 items in this tool (Table 2), although only 3 were considered essential for good quality: item 7 addresses if there was sufficient time for pre-pubescent children to explore their identity, item 13 addresses what percentage of participants were lost to follow-up, which can greatly influence analysis, and item 14 asks if the authors considered outside factors, such as if participants were in supportive homes and communities. A follow-up age of >24 was considered sufficient follow-up period as this age is the maximum age to be considered a young adult by the Federal Interagency Forum on Children and Family Statistics in the United States.47

Table 2.

National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool of Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies Questionnaire

| (1) | Was the research question or objective in this article clearly stated? |

| (2) | Was the study population clearly specified and defined? |

| (3) | Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? |

| (4) | Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? |

| (5) | Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? |

| (6) | For the analyses in this article, were the exposure(s) of interest measured before the outcome(s) being measured? |

| (7) | Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? |

| (8) | For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? |

| (9) | Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? |

| (10) | Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? |

| (11) | Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? |

| (12) | Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? |

| (13) | Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? |

| (14) | Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? |

Items 7, 13 and 14 were considered essential to good quality for this group of studies. For a study to be considered good quality, all three of these items must be met.

For a study to be considered good quality, all three of these items must be met. To be classified as fair quality, a study had to meet at least two of the three, and for poor quality, a study met less than or equal to one of the three. Qualitative studies, case reports, ethical discussions, and editorials were not quality assessed.

Conceptual framework

The author views gender through the lens of the gender affirmation model.48 This model has five pillars: all gender identities and expressions are healthy; gender is diverse and varies across cultures; gender incorporates aspects of biology, development, and socialization; gender may or may not be a static experience, meaning that changes in gender do not invalidate any previous gender expressions; and gender itself is not pathological and the mental health problems such as depression or anxiety that may arise in the TGE child's life are secondary to societal reactions to a child's gender.

Consequently, this model advocates that a child's gender should be affirmed in all situations. Because this model conflicts with other desistance ideas that state a child's gender should be cautiously affirmed only in more extreme dysphoric instances,30,32 all attempts were made to limit the influence of this model on interpretations. However, unconscious biases can still remain, and reflexive practice requires that the theoretical model preferred by the author be acknowledged.

Ethics approval

The ethics committee at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has reviewed this project and has deemed it not in need of ethics approval due to its nature as a literature review.

Results

Search results

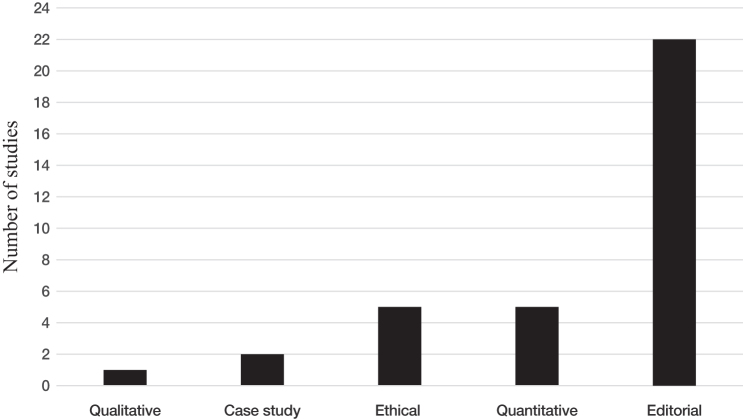

The search strategy identified 3010 studies. After duplicates were removed, 2075 study abstracts were screened, and 1995 studies were deemed irrelevant based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the Methods section. After reviewing the full text of the remaining 80 studies, a total of 35 studies were included in this analysis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of study selection procedure. This figure has a total of seven text boxes, four lined vertically on the left and three lined vertically on the right. The first box in the upper left contains the total studies found, with an arrow pointing to the right of this box toward a box that details the number of duplicates removed. There is an arrow pointing downwards on the left to the box below. This second box down from the upper left contains the total number of studies eligible for review. There is an arrow pointing to the right of this box toward a box that details the number of irrelevant studies based on title and abstract. The third box down from the upper left contains the total studies reviewed in full text. There is an arrow pointing to the right of this box toward a box that details the number of records removed based on full text screening with a breakdown of why these studies were excluded. The fifth box from the upper left corner has the total number of studies included in this review.

Study characteristics

Of the 35 studies, five were quantitative studies, all of which were follow-up design. Two were from the Netherlands, two from Canada, and one from the United States. Of the remaining 30 studies, there was 1 qualitative study based in the Netherlands, 2 case series, 1 from Germany and 1 from the United States, 5 ethical discussions, and 22 editorials (Fig. 2). Of these 22 editorials, the majority were clinical perspectives from the United States. Table 3 provides an overview of all the studies.

FIG. 2.

A bar graph describing the total number of studies found based on methodology used. The y-axis is labeled as “number of studies” and goes up in increments of 2 from 0 to 24. The x axis, from left to right, goes “qualitative,” “case study,” “quantitative,” “ethical,” and “editorial.” All the bars are black. The qualitative bar goes up to one. The case study bar goes up to two. The quantitative bar goes up to five. The ethical bar goes up to five. The editorial bar goes up to 22.

Table 3.

Summary of Studies

| Study title | First author | Country of article/first author | Year | Design | Participants | Findings | Desistance explicitly mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUALITATIVE RESEARCH | |||||||

| Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study | Steensma | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2011 | Individual interviews performed by first author at clinic or at participants' home | 53 Total adolescents eligible: age ≥14 years old, diagnosed with GIDC, competent in Dutch language. 25 Interviewed—based on principle saturation: 14 adolescents applied for sex reassignment at the Gender Identity Clinic, 11 adolescents who had no further contacts with the clinic after childhood and were classified as desisters. Mean age at childhood assessment: 9.41 years old. Mean age at follow-up: 16.11 years old. |

“They (adolescents) regarded the changing social environment (of secondary school) as important” “Anticipated feminization or masculinization of the body during puberty created severe distress” “… associated with the persistence or desistence of childhood gender dysphoria was the experience of falling in love and sexual attraction” “Cautious attitude towards the moment of transitions” |

Yes |

| CASE STUDIES | |||||||

| Gender identity disorder in adolescence: outcomes of psychotherapy | Meyenburg | Frankfurt, Germany | 1999 | Case study | 4 People: three participants 17 years old at initial consult; one participant 13 years old at initial consult. |

If adolescents present with “clear-cut symptoms” of transsexualism, most will have sex reassignment procedures performed eventually | No |

| Understanding pediatric patients who discontinue gender-affirming hormonal interventions | Turban | Massachusetts, United States | 2018 | Case study | 1 Person: initially presented as a trans woman at 15 years; after course of GnRH analog and estrogen, discontinued both; currently identifies as nonbinary. |

“… we have observed that some gender-questioning adolescents benefit from a period of exploration that includes hormonal intervention to consolidate their gender identity” “Extrinsic factors must also be considered when a patient expresses a desire to stop gender-affirming hormones.” |

No |

| QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH | |||||||

| A follow-up study of 10 feminine boys | Davenport | Ohio, United States | 1986 | Follow-up interview inquiring into gender and sexual orientation | 10 Children assigned male at birth: 8 presented w/desire to be a girl; 2 presented with “anatomic dysphoria”; 6 received treatment. At follow-up: 7 were identified as heterosexual; 2 were identified as homosexual; 1 was identified as transsexual. |

Children who are persistent in cross-gender behavior and unwilling/unable to inhibit this behavior are “at risk of a transsexual outcome” | No |

| A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder | Drummond | Toronto, Canada | 2008 | Follow-up with in-person interviews measuring cognitive function, sex typed behavior, gender identity, sexual orientation, and social desirability | 37 Eligible children assigned female at birth from gender identity service: ≤17 years old between 1975 and 2004: 30 contacted (remaining either not available or not reachable); 25 agree to participate (4 parents refuse to give contact info of children, 1 participant declined). 25 Children participated in study: 15 met criteria GID at initial assessment; 4 were intersex; 80% Caucasian. Mean age at initial assessment: 8.88 (3.17–12.95). Mean age at follow-up: 23.24 (15.44–36.58). |

“The percentage of girls with persistent gender dysphoria (12%) was modest, but arguably higher than the base rate of GID in the general population of biological females” “Percentage of girls who differentiated a later bisexual/homosexual sexual orientation was moderate, but clearly higher than the base rates” |

Yes |

| Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children | Wallien | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2008 | Follow-up with in-person interviews measuring gender identity/GD and sexual orientation | 77 Children eligible: ≤16 years old between 1989 and 2005, when first seen at clinic: T0 had 77, 23 did not respond at T1. T1 had 54 children (40 “boys” and 14 “girls”): 75% of the 77 had GID at T0; 21 participants gender dysphoric at follow-up; 100% had GID at T0; 23 participants were home evals because no longer seen at clinic; 10 did not want to participate themselves and had parents fill out; these kids were included in desistance group; 69% had GID diagnosis at T0. Mean age at initial assessment: ∼8 years old. Mean age at follow-up: ∼19 years old. |

27% of total group (77) had persistent GD in adolescence “Girls” were more likely to be persistent than “boys” “Both boys and girls with more extreme gender dysphoria were more likely to develop adolescent/adult GID” “Childhood gender dysphoria thus seems to be associated with a high rate of later same-sex or bisexual sexual orientation” |

Yes |

| A follow-up study of boys with gender identity disorder | Singh | Toronto, Canada | 2012 | Follow-up with initial assessment measuring cognitive function, sex-typed behavior, behavior problems, peer relationships; follow-up appointment measuring: cognitive functioning, behavioral functioning, psychiatric functioning, and psychosexual variables (gender identity, sexual orientation, victimization) | 294 Children eligible: assigned male at birth and ≤16 years old between 1975 and 2009 and assessed at Gender Identity Clinic at CAMH 132 contacted (remaining not due to lack of resources/time—no discussion on how 132 were picked). Additional 32 participants recruited from gender identity clinic at CAMH, came in for: 7—participant/parent contact for GD; 6—participant/parent-concerned sexual orientation; 18—participant/parent-concerned mental health (depression, substance abuse, etc.). 139 Participants total from routine contact (113) or clinical involvement with Gender Identity Service (32) w/6 participants declining: 63.3% were threshold for GIDC; 84.9% Caucasian. Mean age initial assessment 7.49 (3.33–12.99). Mean age follow-up 20.58 (13.07–39.15). |

“17 participants (12.2%) were classified as persisters …” “This study extended previous follow-up studies of boys with GID and, in addition to examining rates of persistent gender dysphoria and sexual orientation outcome, attempted to identify within-group childhood factors that were predictive of long-term psychosexual outcomes.” “Childhood social economic status and severity of cross-gender behavior was identified as predictors of long-term gender identity outcome” |

Yes |

| Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study | Steensma | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2013 | Follow-up with mailed questionnaire on childhood variables, gender identity/GD, body image, sexual orientation, and psychological function and quality of peer relationships | 225 Children eligible: referred to clinic between 2000 and 2008, ≥15 years old during follow-up period of 2008–2012: 127 selected (not say if more than 127 were eligible). 127 Adolescents (79 “boys” and 48 “girls”) who were referred and diagnosed in childhood (<12 years old): 47 persisters based on continued treatment in the clinic; 100% participation; 80 desisters based on discontinued care at the clinic; 46 participated, 6 had parents fill out questionnaire. Mean age at initial assessment: ∼9 years old. Mean age at follow-up: ∼16 years old. |

“Persisters reported higher intensities of gender dysphoria, more body dissatisfaction, and higher reports of a same- (natal) sex sexual orientation compared to desisters” “Chance of persisting was greater in natal girls with GD than in boys” “Psychological function and quality of peer relationships did not predict the persistence of GD” “Cognitive and/or affective gender identity responses on the GIIC and social role transitions … were associated with the persistence of GD” “For natal boys, gender-variant behaviors, their gender role presentation, and parent reports on the intensity of gender role behaviors provide indicators of … future development.” “… it seems important to provide extra focus on girls' own experiences of cross-gender identification and wishes” |

Yes |

| ETHICAL DISCUSSIONS | |||||||

| Hormone treatment of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: an ethical analysis | Abel | Massachusetts, United States | 2014 | Ethical discussion | N/A | “Hormone treatment for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria is ethically challenging” “Respect for a child's autonomy combined with an emphasis on beneficence suggests … hormone therapy should be supported …” “… counterargument is provided through an examination of the principle of nonmaleficence, particularly in light of the likelihood that desisting minors would be left sterile.” |

Yes |

| Ethical issues raised by the treatment of gender-variant pre-pubescent children | Drescher | New York, United States | 2014 | Ethical discussion | N/A | Article focuses on posing question around different aspects of treatment Informed consent should include the following information: Best treatment is subject of controversy No way to predict desist/persist Unclear if an adult transgender outcome can be prevented If social transition, possibility that child might transition back Intervention/nonintervention both carry risks |

Yes |

| Importance of being persistent. Should transgender children be allowed to transition socially? | Giordano | Manchester, United Kingdom | 2019 | Ethical discussion | N/A | “A clinician who has supported ST (social transition) in a child who will later persist will not have been responsible for unnecessary bodily harm … A clinician who has supported ST in a child who will later desist will have violated no moral principle of nonmaleficence” “ST should not be viewed strictly speaking only as a ‘treatment.’ It should also be viewed and used as a tool to allow the child and the meaningful others, including the clinicians, to determine what is the right trajectory for the particular child.” |

Yes |

| The right to best care for children does not include the right to medical transition | Laidlaw | California, United States | 2019 | Ethical discussion | N/A | “Watchful waiting with support for GD children and adolescents is the current standard of care worldwide until the age of 16, not GAT’ “Children and adolescents have neither the cognitive nor the emotional maturity to comprehend the consequences of receiving treatment” |

Yes |

| Transgender children and the right to transition: medical ethics when parents mean well, but cause harm | Priest | Arizona, United States | 2019 | Ethical discussion | N/A | “Transgender adolescents should have the legal right to access puberty-blocking treatment without parental approval” “There is now well-documented evidence that transgender youth who lack access to PBT suffer both physically and emotionally” “The State has a role to play in publicizing information about gender dysphoria and appropriate treatment” |

Yes |

| Editorials (not hypothesis-driven research) | |||||||

| On the “natural history” of gender identity disorder in children | Zucker | Toronto, Canada | 2008 | Clinical perspective | N/A | Written in anticipation of Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis31 article “Will … these three approaches (work with children/parents to lessen gender dysphoria, watchful waiting, and encouraging transition) result in different long-term psychosexual outcomes for these youngsters?” “… whether these different therapeutic approaches will result in different or distinct long-term outcomes with regard to the child's more general psychosocial and psychiatric adjustment?” |

Yes |

| Review of World Professional Association for Transgender Health's Standards of care for children and adolescents with gender identity disorder: a need for change? | de Vries | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2009 | Review article | N/A | “There is a woeful absence of research supporting the ideas about management of GID in young people …” “A few minor changes (for the upcoming seventh edition of the SOC) should be considered” |

Yes |

| The discursive and clinical production of trans youth: gender-variant youth who seek puberty suppression | Roen | Oslo, Norway | 2011 | Critical analysis | Cautiously optimistic about potential of puberty suppression Concerned about the ways in which this treatment may be involved in producing some trans subjects as desisters and others as persisters Critical of normative understandings bound up in clinical endeavors to determine who is, and who is not, a likely trans subject |

Yes | |

| Gender transitioning before puberty? | Steensma | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2011 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “It is conceivable that the drawbacks of having to wait until early adolescence (but with support in coping with the gender variance until that phase) may be less serious than having to make a social transition twice” “Because the chances are high that the gender dysphoria will disappear by early adolescence, it seems advisable to be very careful when taking steps that are difficult to reverse” |

Yes |

| Gender identity: on being versus wishing | Daniolos | Iowa, United States | 2013 | Clinical perspective | N/A | Overview of Steensma et al.53 quantitative follow -up study | Yes |

| Management of juvenile gender dysphoria | Hembree | New York, United States | 2013 | Review article | N/A | Review of care for juvenile GD Open discussions about the needs and options for children and adolescents with GD will occasion opportunities for treatment Persistent GD in early adolescents can be effectively managed by pubertal suppression, followed by sex steroid treatment, should become the accepted standard of care |

Yes |

| Controversies in gender diagnoses | Drescher | New York, United States | 2014 | Clinical perspective | N/A | Presents the author's thoughts on gender diagnosis controversies during his tenure at the DSM-5 Workgroup and Attempt to present alternative opinions |

Yes |

| Found in transition: our littlest transgender people | Ehrensaft | California, United States | 2014 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “We as a mental health community contribute to the well-being of our youngest transgender children by facilitating them being found in transition …” | Yes |

| If we listen: discussion of Diane Ehrensaft's “listening and learning from gender-nonconforming children” | Weinstein | New York, United States | 2014 | Response article | N/A | “There is no area where true neutrality … is more mandatory than in our treatment of gender, where a genuine respect for the child's desire must include the ability to listen and not act” “Until we can reliably predict in whom gender dysphoria will persist, the possibility remains that encouraging puberty blockers will foreclose the potentially organizing experience of development” |

Yes |

| Pre-pubescent transgender children: what we do and do not know | Olson | Washington, United States | 2016 | Clinical perspective | N/A | Focus on two frequent misunderstandings: Transgender identity largely desists during development Studies based on kids who did not see themselves as transgender We do not know which gender-dysphoric children have a transgender identity in adulthood Knowing whether a child consistently claims the “other” gender identity might be the best single predictor of later transgender identity Need prospective studies |

Yes |

| More than two developmental pathways in children with gender dysphoria? | Steensma | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2015 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “Studies encompassing much longer follow-up periods might show a prevalence higher than 16% if individuals with persistence-after-interruption are included” | Yes |

| Gender-nonconforming and transgender children/youth: family, community, and implications for practice | Alegria | Nevada, United States | 2016 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “In collaboration with primary care providers, specialists experienced in working with gender-nonconforming/transgender children and youth can provide guidance with watchful waiting and gender-affirming care” “By providing a receptive and nurturing environment, establishing an effective interdisciplinary team, and incorporating a familiarity with the trajectory of gender nonconformance and resources, primary care providers can elevate the health of this underserved and stigmatized population” |

No |

| Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes | Olson-Kennedy | California, United States | 2016 | Review article | N/A | “Summarize relevant existing research focused on prevalence, natural history, and outcomes of currently recommended clinical practice guidelines, identifying gaps in knowledge, as well as limitations of and barriers to optimal care.” | Yes |

| Gender dysphoria in childhood | Ristori | Florence, Italy/Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2016 | Review article | N/A | “Care for children with GD should not be aimed at avoiding adult same sex attraction or transsexualism; that no medical intervention should be provided in childhood (before puberty); that counseling should therefore be focused on reducing the child's distress related to the GD, on help with other psychological difficulties, and on optimizing psychological adjustment and well-being” “The child's clinical psychological profile and gender development, as well as the contextual psychosocial characteristic of the child's family should always be taken into account to make balanced decisions.” |

Yes |

| Gender dysphoria in children | American College of Pediatricians | Connecticut, United States | 2017 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “Ethics alone demands an end to the use of pubertal suppression with GnRH agonists, cross-sex hormones, and sex reassignment surgeries in children and adolescents.” “The American College of Pediatricians recommends an immediate cessation of these interventions, as well as an end to promoting gender ideology by school curricula and legislative policies.” |

No |

| Pre-pubertal social gender transitions: what we know; what we can learn—a view from a gender affirmative lens | Ehrensaft | California, USA | 2018 | Critical analysis | N/A | “The conservative watchful waiting approach to the treatment of gender-expansive children … appears to be based on binary notions of gender and pathologizing views of gender diversity.” “Allowing children to socially transition may foster secure attachments and resilience not only in the gender-expansive child but also the entire family as they learn to navigate an often hostile world together.” |

Yes |

| A critical commentary on “a critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistence” theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children” | Steensma | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2018 | Response article | N/A | Response to article Temple Newhook et al.28 Should not have included Steensma et al.32 or Steensma et al.53 Nonresponders most likely “desisters” Do not find cisgender outcomes “better” or “healthier” Amsterdam clinic has changed as understandings have grown “Stress that we do not consider the methodology used in our studies as optimal … or that the terminology used in our communications is always ideal” “Agree that the persistence/desistence terms suggest or even induce binary thinking” “Collaboration in gathering more (and better) information about the development of gender-variant children in different social contexts will better serve the quality of life of transgender children” |

Yes |

| A critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistance” theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children | Temple Newhook | California, United States | 2018 | Critical analysis | N/A | “In this critical review of four primary follow-up studies with gender-nonconforming children … we identified a total of twelve … concerns” “The tethering of childhood gender identity to the idea of “Desistance” has stifled similar advancements in our understanding of children's gender diversity” |

Yes |

| Learning to listen to trans and gender diverse children: a response to Zucker (2018) and Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis (2018) | Winters | California, United States | 2018 | Response article | N/A | A response to points raised by Zucker and Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis. On original critical commentary Original article was a critical commentary and not a literature review Call is to move (longitudinal studies) away from the disproportionate focus on using these studies to predict children's identities as they grow up Justification for exclusion of Green's study22 Childhood social transition is not about encouraging a child toward any particular path, but about removing the obstacles that have been preventing them from living fully and freely Clarifications around critiques of Drummond et al.33 methods “… look forward to a time when we not only ask children who they are but also truly learn to listen.” |

Yes |

| The myth of persistence: response to “a critical commentary on follow-up studies and ‘desistance’ theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children” by Temple Newhook et al. (2018) | Zucker | Toronto, Canada | 2018 | Response article | N/A | Response to Temple Newhook et al.28 Should have included Green22 and Singh52 History of desistance term with first use by Zucker (2003)54 Critique of data analysis, including Steensma et al.32 purposeful selection and overlap with Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis31 patients Those who met DSM III, DSM-III-R, or DSM-IV threshold still had desisters Encouraging social transition is intervention as well and could increase persistence, just as efforts to decrease GD may lead to higher rates desistence Disagree with the implicit message of Temple Newhook et al.28 “research on persistence and desistance should be suppressed: it should just disappear without a trace.” |

Yes |

| Debate: the pressing need for research and services for gender desisters/detransitioners | Butler | Bath, United Kingdom | 2020 | Clinical perspective | N/A | “Research with populations who desist and detransition is in its infancy, and little is known about how best to work with this growing population.” | Yes |

| Deficiencies in scientific evidence for medical management of gender dysphoria | Hruz | Missouri, United States | 2020 | Critical analysis | N/A | “The information presented in this report highlights many of the deficiencies in the existing knowledge base regarding the etiology and prevalence of gender dysphoria and current treatment approaches.” “These data provide a rationale for exercising caution in accepting the currently proposed gender affirmation treatment paradigms that have been advocated by the WPATH and other professional organizations” |

Yes |

Findings are given using authors' own language as much as possible. Whether a study explicitly uses the word “desistance” is noted.

DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; GAT, gender affirming therapies; GD, gender dysphoria; GID, gender identity disorder; GIDC, Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood; WPATH, World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Qualitative study

One qualitative study was found, by Steensma et al., exploring factors associated with desisting and persisting.32 Twenty-five total participants were included, 14 of whom were considered persisters and 11 of whom were considered desisters. Factors associated with persistence included distress at “anticipated feminization or masculinization of the body during puberty,”32 and romantic and sexual attraction to someone with a different sex designated at birth, with persisters often validating their transgender identities with a normative heterosexual orientation. Steensma et al. recommended exploring anticipated body distress and sexual attraction before any intervention is initiated. They further recommend being cautious of social transition based on the “unpredictability of the child's psychosexual outcome”32 and on two interviews from people who were labeled as desisting. These two people stated that transitioning to a cisgender identity from a TGE identity was difficult.

This study included a gender expansive individual who identified as 50% female and 50% male. This individual was labeled as a “desister” with the authors pondering if these feelings were a “passing phase (either into desistance or persistence) or whether they remained a stable characteristic of this person.”32

Case studies

There were two case studies. One case study, by Meyenburg in Germany, was used to explore different possible outcomes of patients who were originally referred for gender identity disorder (GID—the previous iteration of GD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]), or gender identity disorder in childhood (GIDC), who received treatment to reduce “gender-deviant” behavior with psychotherapy.49 Meyenburg states that interventions, including surgery, should not be initiated until 18 years of age based on the varying outcomes of the patients described. While the majority of participants in this study were post-pubertal, the article did include one participant who at presentation was 13 years old. The other case study, by Turban et al. in the United States, was used to explore one patient's gender journey from a trans woman to nonbinary (pronouns they/them), and how they needed a period of estrogen gender-affirming hormone treatment to “consolidate” their gender identity.50 It was used to demonstrate the “sometimes dynamic nature of gender identity among youth,” and to advocate for the acceptability of uncertainty when caring for TGE youth. Since this case report followed this person from before the start of puberty, it was included in this review.

Quantitative studies

The research question of four of the five quantitative studies focused on ascertaining the gender identity and sexual orientation among participants at follow-up,31,33,51,52 whereas one study focused on factors that may predict persistence and desistence.53 The 4 studies that explored gender identity and sexual orientation outcomes had 251 total participants. Reported desistance rates, with associated DSM diagnostic tools, can be found in Table 4. These studies focused solely on binary transgender identities (e.g., trans boys/trans girls). All studies explored sexual orientation as a possible outcome for societally deemed atypical gender behavior and/or GD. Only Drummond et al. and Singh reported on socioeconomic position (SEP) and racial/ethnic composition of their study populations, with both studies comprising ∼80% Caucasian participants, the majority of whom were of middle-class SEP (defined using Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status).33,52 All four studies ranked as poor quality as none of them met item 7 or item 14. Davenport, Drummond et al., and Singh all met item 13, while Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis did not.31,33,51,52

Table 4.

Summary of Relevant Findings from the Four Quantitative Studies That Explored Desistance

| A follow-up study of 10 feminine boys—Davenport (1986)51 | A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder—Drummond et al. (2008)33 | Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children—Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis (2008)31 | A follow-up study of boys with gender identity disorder—Singh (2012)52 | Total | Weighted average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality assessment | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | — | — |

| DSM criteria used | DSM III | DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV | DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and DSM-IV-TR | DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV | — | — |

| Total eligible participants (with eligibility criteria) | Not discussed (assume 10), all assigned male at birth | 37 Children assigned female at birth eligible: ≤17 years old between 1975 and 2004 | 77 Children eligible: ≤16 years old between 1989 and 2005 when first seen at clinic, assigned male or female at birth | 294 Children assigned male at birth eligible: ≤16 years old between 1975 and 2009 when first seen at clinic | 418 | — |

| How arrived at total participants included | Not discussed | 30 Contacted (remaining either not available or not reachable); 25 agree to participate (4 parents refuse to give contact information of children, 1 participant declined) | T0 had 77 based on chart review; T1 had 54 as 23 participants did not respond (classified as desisters) | 132 Children were contacted (remaining not contacted due to lack of resources/time—no discussion on how 132 were chosen); from 132, 107 agreed to participate (19 could not be reached, and 6 refused to participate); 32 additional patients recruited after they had contacted the clinic (no discussion on how chosen) | — | — |

| Participants included in the study analysis | 10 | 25 | 77 | 139 | 251 | — |

| Percent of participants who met criteria for GIDC at initial assessment | 80% | 60% | 75% (Based on total of 77 participants) | 63.3% | — | 67% |

| Mean age at initial assessment (with range) | 9 (5–14) | 8.88 (3.17–12.95) | ∼8 (5–12) | 7.49 (3.33–12.99) | — | 7.8 |

| Mean age at follow-up (with range) | 20.2 (15–27) | 23.24 (15.44–36.58) | ∼19 (16–28) | 20.58 (13.07–39.15) | — | 20.3 |

| Follow-up interval in years (with range) | 11 | 14.34 (2.99–27.12) | 11 (9–16) | 12.88 (2.77–29.29) | — | 12.4 |

| Reported desistance percentage | 90% | 88% | 73% | 87.8% | — | 83% |

The remaining quantitative study, by Steensma et al., explored possible predictive factors for persistence versus desistance.53 It was also ranked as poor quality as items 7, 13, and 14 were not met. Predictive factors found included higher intensity of GD at diagnosis, history of childhood social transition, and stating that one was a sex that was not designated at birth (e.g., a child who was designated male at birth saying she is a woman rather than saying she wished she was a woman). This study also focused solely on binary transgender identities.

Ethical discussions

All of the five ethical discussions were written during or after 2014 and only one was written outside of the United States. The two articles published in 2014 attempted to take a neutral perspective on GAC. Abel explored the positives and negatives of gender-affirming hormones through the lens of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence,55 while Drescher and Pula attempted to explore both positive and negative arguments around GAC through posing, but not answering, various questions, such as what are the ethical implications of social transitions or should parents be told “transsexualism” can be prevented.56

Of the remaining three articles, two articles argued in favor of GAC, with one article by Giordano endorsing social transition,57 and another article by Priest advocating for state sponsored access to puberty blocker treatment.3 The final article, by Laidlaw et al., argued against GAC in favor of a form of watchful waiting that differs from the standard model, stating that children younger than 16 years did not have the mental or emotional capacity to make such choices.5

Editorial

The majority of editorials, 13 out of 22, were written from the United States. Four articles were written from the Netherlands, two articles from Canada, and one article each from the United Kingdom, Norway, and Italy. There were 11 clinical perspective articles,58–68 4 review articles,13,69–71 3 critical analyses,28,72,73 and 4 response articles.29,74–76

Desistance Definitions

Of the 35 articles, 30 explicitly used the word desistance (Table 5). Only 13 articles provided an explicit definition for desistance.

Table 5.

Desistance Definitions Ordered by Date of Publication and First Author

| First author (year)Ref. | Definition explicit/inferred | Desistance definition | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drummond (2008)33 | Inferred | People with any level of GD who were once 17 years or older no longer had any distress about their gender identity | 3 |

| Wallien (2008)31 | Inferred | People who previously attended the gender clinic and no longer sought services at the gender clinic in Amsterdam | 4 |

| Zucker (2008)58 | Inferred | Children who no longer experience GD | 1 |

| de Vries (2009)69 | Explicit | “GID does not continue (or desists) later in life” | 1 |

| Roen (2011)72 | Explicit | “those who ‘change their minds’ in the course of adolescence” regarding “reassignment” | 4 |

| Steensma (2011)32 | Inferred | No longer meeting criteria for GD for the respective age group | 1 |

| Steensma (2011)59 | Explicit | “Children who transitioned in childhood, but discovered at an older age that they preferred to live in the gender role of their natal sex again” | 2 |

| Singh (2012)52 | Inferred | Children with GID who do not have GID in adulthood | 1 |

| Daniolos (2013)60 | Explicit | Those who in time are able to “settle” into their natal gender | 2 |

| Hembree (2013)70 | Inferred | When the dysphoria that occurs due to variance between natal sex and gender no longer exists after puberty | 1 |

| Steensma (2013)53 | Inferred | No longer meeting criteria for GD for the respective age group | 1 |

| Abel (2014)55 | Explicit | “While many young children will ultimately decide to revert to their natal gender—known as desisting” | 2 |

| Drescher (2014)61 | Inferred | GD that does not continue into adolescence and adulthood | 1 |

| Drescher (2014)56 | Explicit | “The gender dysphoria of the majority of children with GD/GV does not persist into adolescence, and when it does, the children are referred to as ‘desisters’” | 1 |

| Ehrensaft (2014)62 | Explicit | “children who grew out of their gender dysphoria” | 1 |

| Weinstein (2014)74 | Inferred | GD that stops after adolescence, or those who are “lacking a true aversion to their natal body” | 1 |

| Steensma (2015)63 | Explicit | “children for whom the gender-dysphoric feelings desisted in adolescence and who do not reapply for treatment” | 1 |

| Olson (2016)65 | Inferred | Children who no longer identify as transgender (binary) after adolescence | 2 |

| Olson-Kennedy (2016)13 | Inferred | Gender-dysphoric children who do not go on to have GD and/or transgender identities in adolescence and adulthood | 2 |

| Ristori (2016)71 | Inferred | Gender-dysphoric feelings that are no longer felt after puberty | 1 |

| Ehrensaft (2018)58 | Explicit | “Youth (who are gender nonconforming) may “desist” or eventually assert a cisgender identity in adolescence” | 2 |

| Steensma (2018)75 | Explicit | “Persistence and desistence of children's distress caused by the gender incongruence they experience to the point that they seek clinical assistance” | 3 |

| Temple Newhook (2018)28 | Explicit | “gender-nonconforming children… said to have “desisted” from a prior transgender identity” | 2 |

| Winters (2018)76 | Inferred | No longer have a transgender identity after childhood (adolescence and adulthood) | 2 |

| Zucker (2018)29 | Inferred | Children with GD in childhood, who did not have a “developmentally equivalent adolescence or adulthood diagnosis” | 1 |

| Giordano (2019)57 | Explicit | “Gender diverse children whose feelings of gender dysphoria desisted into adolescence OR Gender diverse children who do not have a desire for medical gender-affirming treatment after they enter puberty” | 1 |

| Laidlaw (2019)5 | Inferred | Children who are no longer dysphoric after puberty | 1 |

| Priest (2019)3 | Explicit | “transgender children who revert back to their natal gender” | 2 |

| Butler (2020)68 | Inferred | Children who begin undergoing a gender transition and then choose to stop this journey | 2 |

| Hruz (2020)73 | Inferred | Children who “express gender discordance…and experience reintegration of gender identity with biological sex by the time of puberty” | 2 |

Explicit definitions are in bold. Definitions that are inferred are not in bold.

Theme 1: desistance as the disappearance of the diagnosis of GD after the start of puberty or during adolescence. Theme 2: as a change in gender identity from TGE to cisgender. Theme 3: desistance as the disappearance of distress around gender identity and body incongruence. Theme 4: desistance as disappearance of the desire for medical intervention. TGE, transgender and gender expansive.

Fifteen articles referred to desistance as the disappearance of the diagnosis of GD after the start of puberty or during adolescence, not related to social or medical interventions.5,29,32,52,53,56–58,61–63,69,71,74 Only three of these included the absence of GD in adulthood as well, again not related to social or medical interventions.29,52,61 Eleven articles used desistance to indicate a change in gender identity from TGE to cisgender.3,13,28,55,59,60,65,67,68,73,76 Two articles used desistance to mean the disappearance of distress around gender identity and body incongruence not related to social or medical interventions.33,75 Two articles considered that desistance involves the disappearance of the desire for medical intervention.31,72

All the articles implied that the disappearance of GD also meant that the TGE child identified as cisgender after puberty. There was no indication of how this conclusion was made.

None of the quantitative studies explicitly defined desistance.31,33,51–53 Three of the quantitative studies had similar inferred definitions based on the disappearance of GD.51,52,53 The other two studies had inferred definitions relating to distress concerning gender identity and desire for medical intervention.31,33

Discussion

Despite the large number of controversies surrounding desistance, no consensus has been reached in universally defining it. Most of the articles reviewed failed to explicitly define desistance, leaving much room for interpretation.

First, there appears to be a mix of time periods associated with when desistance occurs, with some definitions stopping at puberty and others extending into adulthood. This could be because of a perceived gender permanence after adolescence.4,16,61 The assumption is that if GD is not present after the start of puberty, then it must also not be present during adulthood. The distinction between desistance occurring only around puberty and desistance that extends into adulthood is important. Confining desistance solely to gender identity around puberty allows for more gender identity options during adulthood. Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis discuss how some people who identified as TGE in childhood will identify as cisgender during adolescence and then as TGE during adulthood.63 While in this article, the idea was that the gender identity in adulthood was then permanent, allowing gender to be something that can change at any point in one's life will help validate those people who experience a dynamic form of gender.

Second, some definitions of desistance focus on GD, while others focus on gender identity. An almost equal number of articles referred to desistance as the disappearance of GD as did articles that referred to desistance as the change of a transgender identity to a cisgender identity. Disappearance of GD and a change in gender identity are two concepts that, while occasionally connected, remain distinct. GD is associated with significant distress at the differences between gender and body, whereas a TGE gender identity does not require that distress. Therefore, a TGE child could still identify as TGE even if they do not experience GD. Despite having stated difference in these definitions, all the articles conflated these two ideas, implying that the disappearance of GD also meant that the TGE child identified as cisgender after puberty.

Moving forward, however, wording needs to be considered carefully as the implications are profound. If one believes that gender identity may change during adolescence, then interventions such as social transition and puberty blockers appear more harmful than beneficial.

However, if one believes that GD will disappear during puberty, but a TGE identity may remain, then social transition and puberty blockers may be beneficial, with the acknowledgement that someone who identifies as TGE may or may not desire medical interactions and may affirm their gender outside of medicine.

This relates to the idea of gatekeeping, as TGE youth are required to prove to providers that their dysphoria is severe and persistent enough to warrant treatment. For example, both Steensma et al. and de Vries and Cohen-Kettenis suggested that TGE children should be dissuaded from social transitioning in public as they will most likely not continue to have these feelings post-puberty, and the hardships faced in transitioning from a trans to a cisgender identity can be too great for the child.30,32 This opinion is slightly dampened in a later article by Steensma et al., where recommendations were made to instead focus on weighing the benefits and challenges of social transition.53

However, this change still places a great deal of power in the hands of the physician in terms of deciding what constitutes a benefit versus a challenge.

Finally, none of these definitions allow for non-binary or dynamic gender expressions.28,75 According to these definitions, one either desists or persists in a binary transgender identity. Nonbinary and gender expansive individuals have worse health outcomes compared to transgender people with binary gender identities, and significantly less research associated with the unique health concerns of this group.26 Therefore, this exclusion further impairs the ability to support this group by further erasing them from medical literature.

Based on this review of the literature, scarce hypothesis-driven research dedicated to desistance and/or persistence exists, with the majority of publications falling into an editorial category. This is important to note as it highlights the controversy and emotions that encircle TGE children.67 It is puzzling that 22 editorials can argue for or against the provision of GAC based on only 5 quantitative studies, all of which had relatively small sample sizes and substantial risk of bias. While some would argue that there are many more quantitative studies, in reference to the early work done in 1960s–1980s, these works were not explicitly exploring the phenomenon known as “desistance,” nor were they scientifically sound as they occurred in environments that viewed minority sexual orientations and gender identities as pathological and actively attempted to “cure” and/or prevent them.

Clinical Implications

The studies reviewed here tended to focus solely on higher SEP white trans youth. Future studies need to focus on the intersectional factors, such as race/ethnicity and SEP status, which may influence one's ability to explore gender and be able to express their gender, especially considering that TGE people who are racially minoritized have higher health disparities and worse experiences with providers compared to TGE people who are white.77

Based on the discussion above, “desistance” should be removed from clinical and research frameworks, as it does not allow for the varied and complex exploration of gender that is more reflective of reality. The idea of desistance creates a false dichotomy (persistence or desistence) that only hinders provision of care by suggesting a possibility to predict future gender identity. In addition, desistance does not take into consideration the myriad of societal influences that can prevent a person from expressing their gender.78 Clinicians can move beyond attempting to predict gender outcomes to focusing on ways to support TGE youth as they discover themselves. This may look like having continuous discussions with young people to check in on their gender journey—how their goals may remain or change or expand—with validation of gender expansive identities that exist beyond binary gender identities. Some TGE people do not need medical interventions to affirm their gender and can create their gender expression outside of medicine.79,80 If this is the case, health care providers should be supportive and affirming.

Also, clinicians can begin to view changes in gender as normal rather than invalidations of any previously stated gender identity—gender is a constant exploration for many, and therefore all stops along this gender journey are valid, including if a youth who previously identified as TGE currently is identifying as cisgender.12 Cisgender identity does not invalidate transgender identity. There is understandable discomfort with this uncertainty and constant exploration for both families and providers, yet having this freedom to explore can help young people learn what feels right for them in that moment.50 Most importantly, everyone who provides gender care to young people should know that the young people themselves are the experts on their gender identity and expression. As Jules Gill-Peterson states in her book, Histories of the Transgender Child, “we are not worthy of the care of trans children we have accorded ourselves.”81

Strengths and Limitations

This review contributes a novel interpretation of the desistance literature by providing a comprehensive list of desistance definitions.

A major strength of this review was that it was written by someone within the TGE community. While it is not advisable to assume the gender identity of any of the authors, only three articles explicitly stated that the authors had a connection with the TGE community.28,72,76 Arising from the disability community, “nothing about us without us” is a battle cry to stop research on communities without representation of that community on the research team.82

Having only one reviewer limits the collection of data and data analysis, as additional reviewers would challenge each other and possibly introduce different perspectives. To this point, incorporating a TGE adolescent co-investigator would provide an often unheard and much needed perspective on how this research impacts their community. If more time and resources were available, additional sources of data could have been explored, such as book chapters or conference abstracts.

Conclusions

Of the hypothesi- driven research articles pertaining to desistance found in this literature review, most were ranked as having significant risk of bias. A significantly disproportionate number of these articles were not driven by an original hypothesis. The definitions of desistance, while diverse, were all used to say that TGE children who desist will identify as cisgender after puberty, a concept based on biased research from the 1960s to 1980s and poor-quality research in the 2000s. Therefore, desistance is suggested to be removed from clinical and research discourse to focus instead on supporting TGE youth rather than attempting to predict their future gender identity.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all of the people who provided insightful guidance and direction for this project—Dr. Alic Shook, Annie Sansonetti, Anusuya R, Dr. Caroline Salas-Humara, Diana Tordoff, Jessica Massie, Joey Nicholson, Lizzie Jordan, Michelle Diedro, Nimue Smit, Dr. Russell Burke, and Talen Wright. I could not have reached this point without your invaluable input. A special thanks to Dr. Nick Douglas, my advisor—this project would not have happened without your compassion, guidance, and encouragement, especially during this difficult time.

Abbreviations Used

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GAC

gender-affirming care

- GD

gender dysphoria

- GID

gender identity disorder

- ODD

oppositional defiant disorder

- SEP

socioeconomic position

- TGE

transgender and gender expansive

- WPATH

World Professional Association for Transgender Health

Author Disclosure Statement

The author has no commercial associations or conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

No funding was used in this project.

Cite this article as: Karrington B (2022) Defining desistance: exploring desistance in transgender and gender expansive youth through systematic literature review, Transgender Health 7:3, 189–212, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0129.

References

- 1. Byng R, Bewley S, Clifford D, McCartney M. Gender-questioning children deserve better science. Lancet. 2018;392:2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pang KC, Pace CC, Tollit MA, Telfer MM. Everyone agrees transgender children require more science. Med J Aust. 2019;211:142..e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Priest M. Transgender children and the right to transition: medical ethics when parents mean well but cause harm. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19:45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richards C, Maxwell J, McCune N. Use of puberty blockers for gender dysphoria: a momentous step in the dark. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:611–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laidlaw M, Cretella M, Donovan K. The right to best care for children does not include the right to medical transition. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19:75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agana MG, Greydanus DE, Indyk JA, et al. Caring for the transgender adolescent and young adult: current concepts of an evolving process in the 21st century. Dis Mon. 2019;65:303–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People. University of California, San Francisco, CA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869–3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kreukels BPC, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in gender identity disorder: the Amsterdam experience. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dreger A. Gender identity disorder in childhood: inconclusive advice to parents. Hastings Cent Rep. 2009;39:26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ehrensaft D. Gender nonconforming youth: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2017;8:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olson-Kennedy J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BP, et al. Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vrouenraets LJJJ, Fredriks AM, Hannema SE, et al. Early medical treatment of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: an empirical ethical study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright T, Candy B, King M. Conversion therapies and access to transition-related healthcare in transgender people: a narrative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winters K. The “80% Desistance” Dictum: Is It Science? Families in Transition: Parenting Gender Diverse Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults (Lev AI, Gottlieb, AR; eds.) Columbia University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2012 [7th Version]. Available at: https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

- 18. Bakwin H. Deviant gender-role behavior in children: relation to homosexuality. Pediatrics. 1968;41:620–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lebovitz PS. Feminine behavior in boys: aspects of its outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 1972;128:1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Money J, Russo AJ. Homosexual outcome of discordant gender identity/role in childhood. In: Readings in Pediatric Psychology. (Roberts MC, Koocher GP, Routh DK, Willis DJ; eds) Springer, Boston, MA, 1993, pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zuger B. Early effeminate behavior in boys: outcome and significance for homosexuality. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green R. The “Sissy Boy Syndrome” and the Development of Homosexuality. London, UK, Yale University Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bryant K. In defense of gay children? `Progay’ homophobia and the production of homonormativity. Sexualities. 2008;11:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beemyn G. Genderqueer. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/genderqueer Accessed February 21, 2020.

- 25. Tobia J. InQueery: the history of the word “genderqueer” as we know it: them. 2018. Available at: https://www.them.us/story/inqueery-genderqueer Accessed February 21, 2020.

- 26. Scandurra C, Mezza F, Maldonato NM, et al. Health of non-binary and genderqueer people: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagoshi JL, Brzuzy SI, Terrell HK. Deconstructing the complex perceptions of gender roles, gender identity, and sexual orientation among transgender individuals. Femin Psychol. 2012;22:405–422. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Temple Newhook J, Pyne J, Winters K, et al. A critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistance” theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zucker KJ. The myth of persistence: response to “A critical commentary on follow-up studies and ‘desistance’ theories about transgender and gender non-conforming children” by Temple Newhook et al. (2018). Int J Transgend. 2018;19:231–245. [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Vries AL, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Clinical management of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents: the Dutch approach. J Homosex. 2012;59:301–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wallien MS, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1413–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steensma TD, Biemond R, De Boer F, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16:499–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drummond KD, Bradley SJ, Peterson-Badali M, Zucker KJ. A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olson KR, Durwood L, Demeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pyne J. Health and wellbeing among gender independent children: a critical review of the literature. In: Supporting Transgender and Gender Creative Youth: Schools, Families, and Communities in Action. (Elizabeth Meyer, Annie Pullen Sansfacon; eds). New York: Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Serano J. Detransition, desistance, and disinformation: a guide for understanding transgender children debates. Medium, 2016. Available at:https://medium.com/@juliaserano/detransition-desistance-and-disinformation-a-guide-for-understanding-transgender-children-993b7342946e Accessed July 1, 2020.

- 37. Andersson J. The medical, ethical, and legal complications surrounding the puberty blockers case. iNews.com, 2020. Available at: https://inews.co.uk/news/puberty-blockers-legal-case-experts-transgender-1361915 Accessed February 18, 2020.

- 38. U.S. Professional Association for Transgender Health. Statement in response to proposed legislation denying evidence-based care for transgender people under 18years of age and to penalize professionals who provide that medical care. 2020. Available at: https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/Public%20Policies/2020/FINAL%20Joint%20Statement%20Opposing%20Anti%20Trans%20Legislation%20Jan%2028%202020.pdf?_t=1580243903 Accessed February 18, 2020.

- 39. Brooks L. Puberty blockers ruling: curbing trans rights or a victory for common sense? The Guardian, 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/dec/03/puberty-blockers-ruling-curbing-trans-rights-or-a-victory-for-common-sense- Accessed January 27, 2021.

- 40. Nelson JD. Pediatrics, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2020. [Google Scholar]