Abstract

Research on transgender and gender expansive (TGE) youth has highlighted the disproportionate and challenging mental health and developmental outcomes faced by these young people. Research also largely suggests that family acceptance of TGE youth's gender identity and expression is crucial to preventing poor psychosocial outcomes in this community. Recently, family-based treatment has become common practice with TGE youth whose families are available for care, but it is unclear whether research provides outcome data for family interventions with TGE youth. This study follows Preferred Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to systematically review articles that provide outcome data or clinical recommendations for family-based interventions with TGE youth and their families. No quantitative outcome data for family therapy with TGE youth were found, but numerous articles spanning decades (n=32) provided clinical practice recommendations for family-based interventions with this population. Very few articles provided outcome data for family therapy with sexual minority youth (n=2). Over time, clinical strategies have moved from pathologizing to affirming of TGE youths' gender journey. Common clinical strategies of affirming interventions include (1) providing psychoeducation, (2) allowing space for families to express reactions to their child's gender, (3) emphasizing the protective power of family acceptance, (4) utilizing multiple modalities of support, (5) giving families opportunities for allyship and advocacy, (6) connecting families to TGE community resources, and (7) centering intersectional approaches and concerns. Future research should examine the efficacy of family-based interventions that incorporate these clinical strategies and collect quantitative data to systematically determine their effect on psychosocial outcomes.

Keywords: transgender, family therapy, family acceptance, family support, psychoeducation, systematic review, gender nonbinary, youth, best practice recommendations

Research on transgender and gender expansive (TGE) youth has highlighted the disproportionate and challenging mental health and developmental outcomes faced by these young people. Compared with cisgender peers, TGE youth often display higher rates of mental health symptoms, safety risks, and psychosocial complications. In particular, compared with cisgender youth, TGE youth exhibit disproportionately high rates of depression1–4 anxiety,3,5,6 suicidality,1,3,4,7 and nonsuicidal self-injury.3,4,7 Many other negative psychosocial outcomes, such as homelessness,8,9 school absence and dropout,10 survival sex work,11 HIV,11,12 bullying,13 gender-related victimization at school,14 dating violence,15 childhood sexual, psychological, and physical abuse,16 and substance use/abuse,17 are also disproportionally high among transgender youth.

Families frequently play a large role in determining psychosocial outcomes for TGE youth.18 Along these lines, numerous studies suggest that the largest predictor of suicide attempts within the context of minority stress for TGE young people is lack of family support.19–22 Lack of family support can be particularly detrimental for several reasons. First, affirmation in legal, educational, and mental health systems is associated with positive mental health.23–25 Without family support in these domains, TGE youth do not have assistance in navigating complex educational, medical, mental health, and legal systems, further increasing distress. Second and systemically, a critical factor in the development of mental health and psychosocial problems in TGE youth appears to be the lack of acceptance, specifically of the child's gender identity and expression, by the child's family of origin.19–21

Studies focusing on family acceptance show that it is an essential component of TGE youths' affirmation, and that it greatly improves their mental health while decreasing the chances of risk behaviors and self-harm.26–28 For instance, the groundbreaking research of the Transgender Youth Project pioneered by Olson and colleagues has shown that (1) transgender youths' rates of anxiety and depression are similar to those in cisgender children, and (2) psychosocial issues do not reach a clinical range if transgender children are socially affirmed and supported by their families and peers.29,30 Similar results demonstrating the protective role of family acceptance have also been found in the Canadian Trans Youth Health Survey.31,32

Given the centrality of family acceptance to positive mental health in TGE youth, family involvement is crucial to ensuring effective psychological care for this vulnerable population. TGE young people who access family-based support services are 82% less likely to attempt suicide than those who do not access such services.33 Family therapy, specifically, has been shown to be an effective intervention in reducing depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in adolescents.34,35

Reflecting these findings, models of care for TGE children and adolescents are becoming increasingly affirming and inclusive of social and familial contexts.24,25,36–39 Along with the slow increase in gender inclusivity of the mental and medical health fields at large, standards of care have evolved toward a more affirmative, less cisnormative and pathologizing model.40 Of note, treatment models that are affirming of the child's gender identity and expression (i.e., gender-affirmative models) are becoming more widely used,25,41 but research on these models is still limited.42 Family-based treatment has become a common practice with TGE children and adolescents whose families are available for care.24,36,37,43–47

However, researchers have noted the lack of studies providing outcome data for family-based interventions that specifically target TGE youth.48 While a systematic review of empirically supported family therapy interventions for sexual minority youth and their families yielded specific strategies for clinicians working with that population,49 to date no such systematic review has been conducted for TGE youth and their families. Such a review would support the identification of best practice recommendations for family therapy, family engagement, and family acceptance work carried out in clinical and community settings. This article addresses this gap in knowledge by systematically reviewing research on family-based interventions for TGE youth and their families. Owing to the dearth of literature in this area and the frequent overlap of research regarding lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth issues and TGE youth issues,50 a second search was conducted for family-based interventions for LGB youth, with the hope that outcome data from studies on family-based interventions with LGB youth could form an additional basis for clinical and research recommendations for family-based interventions with TGE youth.

Materials and Methods

Database searches

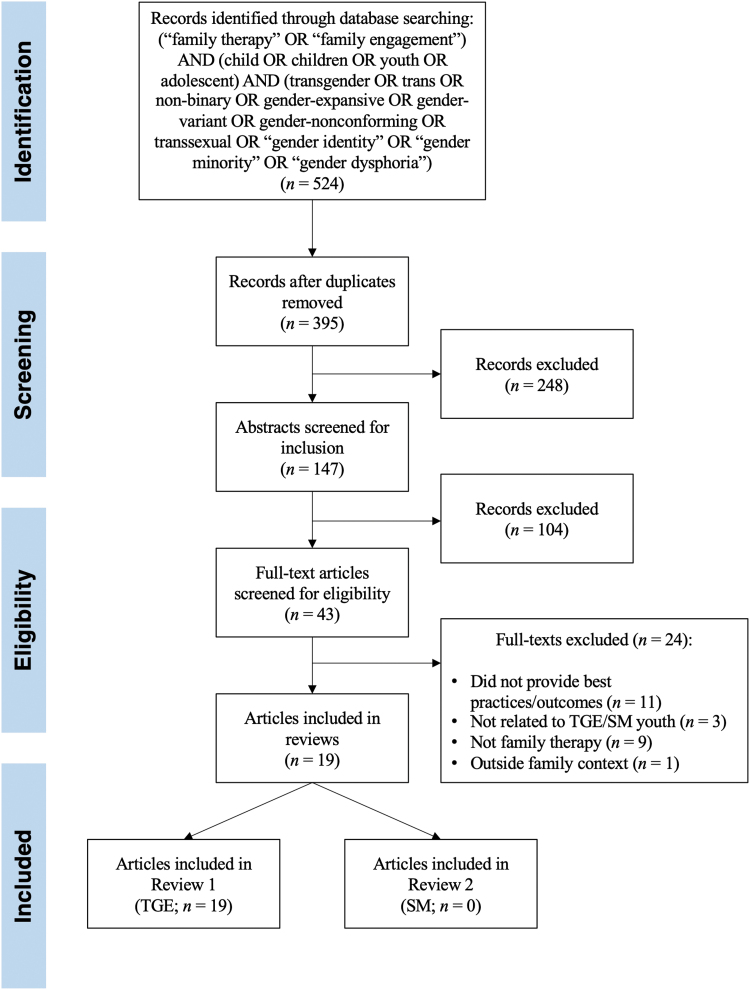

The current systematic review follows the Preferred Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.51 Searches of the PsycINFO, PubMed, ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts International, Web of Science, Embase, Gender Watch, and LGBT Life databases were conducted to find relevant articles published through 2018. Two Boolean statements (i.e., compound statements that use “OR” and “AND” to combine individual search terms) were used to search for articles specifically related to family therapy and family engagement interventions with LGB youth and TGE youth (see Fig. 1 for search terms). The first Boolean statement (Search 1) included terms related to TGE youth, whereas the second Boolean statement (Search 2) included terms related to sexual minority youth. The term “transsexual” was included in the TGE-related search terms to include older articles that describe family-based interventions for the formerly assigned diagnoses of “transsexualism,” or “gender identity disorder,”52 which have since been replaced with “gender dysphoria” with the publication of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).53

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for Search 1. PRISMA, Preferred Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SM, sexual minority; TGE, transgender and gender expansive.

Two reviews were conducted with the articles yielded from both searches. The first was a review of both quantitative outcome data and qualitative data, as well as best practices, and clinical recommendations for family-based interventions with TGE youth and their families (Review 1). The second was a review of quantitative outcome data only for family therapy interventions with sexual minority youth (Review 2). Given the frequent conceptual overlap of research regarding sexual minority issues and gender minority issues,50 it was theorized that the results from the review of family therapy for sexual minority youth (Review 2) could guide future efforts to collect similar quantitative outcome data examining the effectiveness of family-based interventions with TGE youth. The authors hypothesized that, given the relative dearth of family therapy research in transgender populations compared with LGB population,54,55 they would be more likely to identify outcome data pointing to the effectiveness of specific modalities, interventions, and their connection to the well-being of LGB youth and their families.

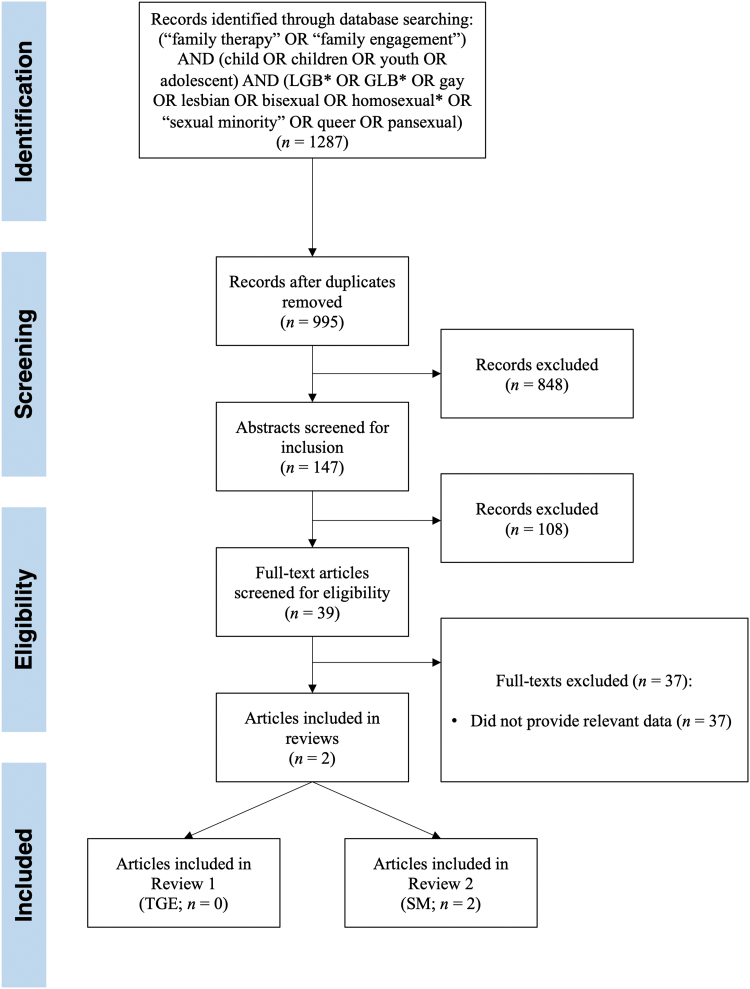

Nonduplicate records yielded from database searching (Search 1: n=395; Search 2: n=995) were screened for inclusion for both reviews by the authors. Abstracts of records that were determined by the authors to be of potential relevance to either review were then examined for inclusion by the three authors (Search 1: n=147; Search 2: n=147). Full text of the resulting articles (Search 1: n=43; Search 2: n=39) were then reviewed by the authors to ensure they satisfied inclusion and exclusion criteria for either Review 1 or Review 2, with disagreement resolved through discussion. Relevant information was then coded from the final set of articles (Search 1: n=19; Search 2: n=2) regarding outcomes and treatment recommendations (described individually for each review hereunder). See Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 for search processes for Review 1 and Review 2 respectively.

FIG. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for Search 2. GLB, gay, lesbian, and bisexual; LGB, lesbian, gay, and bisexual.

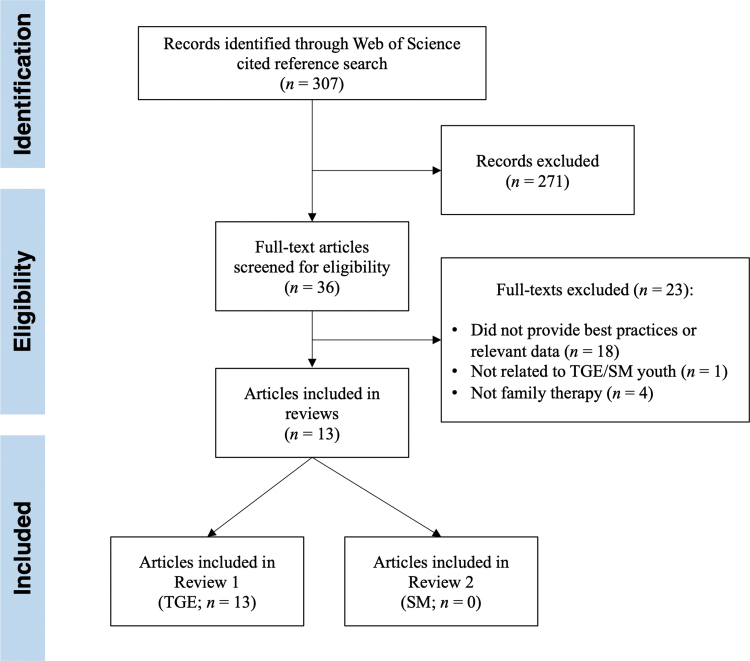

Finally, to include relevant articles that were published during the writing of this review, a cited reference search was completed (Fig. 3). This search was conducted using the Web of Science database to find any peer-reviewed journal articles published through 2019 that cite the included full-texts from Search 1 (n=19) and Search 2 (n=2). Abstracts from this set of new records (n=307) were screened for inclusion using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as described previously. Relevant full-texts (n=37) were reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria, and then relevant information was coded from the final set of articles (n=13) using the same methods as with Search 1 and Search 2 (as described individually for each review hereunder).

FIG. 3.

PRISMA flow diagram for cited reference search.

Review 1: Family therapy for TGE youth

Quantitative and qualitative research articles, as well as articles outlining treatment best practices published in English-language peer-reviewed journals were considered for inclusion in the first review if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the article was published in English, and (2) the article provided treatment strategies, best practices, clinical recommendations, or outcome data related to family therapy or interventions to increase family engagement with transgender and gender expansive (TGE) youth. Based on a previous systematic review of family therapy interventions with sexual minority youth,49 articles were excluded from the first review if they (1) were not related to TGE youth, (2) addressed issues of gender identity and expression in the context of individual or group therapy, rather than family therapy, or (3) only provided treatment strategies, best practices, clinical recommendations, or research results regarding gender identity or expression outside the family context.

The final set of articles that met all inclusion and exclusion criteria for Review 1 (n=32) were then coded for the following information: (1) population of interest, (2) treatment modalities used, (3) outcome data (if any) and/or empirical support, (4) clinical strategies suggested, and (5) additional relevant themes explored. A summary of this information is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Articles on Family Therapy with Transgender and Gender Expansive Youth (Review 1)

| Citation | Sample of interest | Treatment modalities | Outcome data/empirical support | Clinical strategies | Additional themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green et al.56 | “Very feminine young boys and their parents (n=4) | Behavior modification | Clinical observation of “reorientation” toward cisgender identification and expression after treatment in four case studies | • Develop a relationship of trust and affection between the male therapist and the boy. • Heightened parental concern about the problem so that parents begin to disapprove of feminine interests and no longer covertly encourage them. • Sensitize parents to the interpersonal difficulties that underlay the tendency of the mother to be overly close with the son and for the father to emotionally divorce himself from family. • Sensitize the child to “feminine” behaviors. |

• Pathologizing and similar to conversion therapy. • Cisnormative/binary construction of masculinity, femininity, and gender identity development. |

| Higham57 | Children and adolescents with a “gender disorder” (n=4) | Rehabilitative approach | Clinical observation that the two older patients showed “improvement” (i.e., desistance). | • Sex role stereotypes, including choice of friends and activities, should be presented as social options rather than sex-linked imperatives. • Educate family and child with respect to sex differences (e.g., menstruation and gestation in women). • After initial investigation, consultations are as needed, with the long-term goals of achieving independence, a satisfying life work, and gratifying personal and sexual relationships for the child. |

• Pathologizing (i.e., desistence from transgender identity conceptualized as a positive outcome). |

| Newman58 | “Extremely feminine boys” (trans and nonbinary AMAB children 5–12 years old) (n=5) | Weekly individual play therapy (psychoanalytic and behavioral) and weekly parental counseling | Anecdotal report of behavior and identity change based on four years of treatment with AMAB youth | • Pretreatment (assessment of major “pretranssexual” behavior) with parents and child. • Weekly individual child treatment and parental counseling. • Post-treatment follow-up focusing on family dynamic and marital relationship. • Address mother's ambivalence, dependence on son, father's absence and avoidance, and marital dissatisfaction. |

• Pathologizing and similar to conversion therapy. • Cisnormative/binary construction of masculinity, femininity, and gender identity development. • Views gender diversity as aberration often caused by unhappy marriages and dependent mothers. |

| Wrate and Gulens59 | Transfeminine children of heterosexual parents | Systems family therapy | “Successful” reduction in feminine behavior observed by clinician in one family case study (one transfeminine child, two heterosexual parents) | • Increase parental emotional involvement. • Improve parents' behavioral control over children. • Increase parents' sense of achievement and satisfaction. • Increase emotional separation of child from mother. • Provide child a peer support group of those with behavioral disturbance. |

• Pathologizing and similar to conversion therapy. • Addressing parental anxiety is key to youth's adjustment. |

| Bradley and Zucker60 | Children and adolescents with GID | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Have a strong alliance with parents to help them work through ambivalence toward treatment. • Have short-term goals of reducing social ostracism/conflict and alleviating associated psychopathology. |

• Parental ambivalence toward treatment is more common when referral is from outside the family. • Intervention during childhood can lead to greater reduction in gender identity conflict than intervention in adolescence. • Long-term goal for treatment is prevention of “transsexualism”/homosexuality. |

| Sugar61 | Children with GID | Psychoanalytic therapy | Single case example with 4-year-old AMAB child | • Treatment should consist of weekly psychoanalytic individual treatment, parent guidance sessions, and family/couples therapy (as needed). • History-taking should include details about daily routines, esp. on boundaries with parents. • Set limits for the child within the therapeutic context. • Encourage parents to set limits on cross-gender behavior at home and at school, especially regarding gender boundaries between child and mother. |

• Takes a psychoanalytic approach to gender identity development and GID (psychosexual stages, castration anxiety, etc.). • GID can develop from improper limit-setting by the mother and passivity/absence of the father. • Reduction in cross-gender behavior seen as a positive treatment outcome. |

| Saeger62 | Transgender child and their parents | Family work and play therapy | Single case example | • Help parents practice supporting pronouns and appearance. • Collaborate with the child's school. • Meet with grandparents (and potentially include in treatment). |

• Uses Lev's conceptualization of stages of adaptation to the child's gender.63 • Discusses authenticity of identity vs. family dynamics. |

| Behan64 | Families with a transgender child/adolescent | Not specified | N/A | • Provide family with gender psychoeducation. • Sometimes advocacy with school is necessary. • Ask the transgender child to give their family time to process the transition. • Put families in contact with other families with trans youth (e.g., support groups) to create a feeling of “belonging.” • Delay in puberty should be provided to transgender adolescents who want it with consent of parents. • Provide positive and resilient images of transgender identities, rather than viewing it as a problem. |

• Families often suffer at “losing the child they knew” and their imagined future. • Sometimes the family slows down the child's transition, which is often experienced as fast because of prior concealment of gender identity. |

| Butler65 | “SGM” individuals | SGMT and systemic practice | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Self-reflect on how (sexual) identity influences work with clients (e.g., using CMM). • Therapist should engage in thoughtful disclosure that contributes to conversations. • Take a “not-knowing” approach to the clients' sexuality, etc. • Encourage connection with wider SGM communities and perspectives. • Resist applying principles extrapolated from work with non-SGM clients. • Link families to resources and support networks so they can share experiences. • Help family members reflect on range of emotional reactions. • Rehearse discussions of disclosure with those outside the family. • Help parents grieve the loss of the heterosexual child and associated expectations. • Assist parents to “come out” to combat homophobia and discrimination. |

• A variety of identity-related factors can impact how families respond to their child's coming-out (religion, gender, race, etc.). • Focuses on LGB/sexual identity questions more than TGE/gender identity questions. |

| Lev66 | Lesbian parents with gender-expansive kids | Family therapy | Recommendations derived from literature and clinical experience | • Promote a home life where the child has flexibility and room to fully explore their gender. • Help families decenter heteronormativity/cisnormativity. • Help family members understand their own relationship to gender. |

• Kids raised in queer homes have less rigid gender roles. • It might be easier for kids to come out as queer to queer parents. |

| Parker et al.67 | Families with GLBT youth | Family therapy, Kite in Flight model | Case example | • Promote personal empowerment and self-agency through dating relationships. • Increase differentiation through identity development in dating. |

• Stresses importance of context and environmental influences, including race, ethnicity, rural/urban, SES, religion, etc. • Link between dating, romantic relationships, gender identity and family engagement not specifically made. |

| Malpas43 | Transgender and gender-nonconforming children and their families | MDFA | Case example and recommendations derived from clinical experience | • Assess parental acceptance, rejection, and knowledge of issues related to transgender children, and emphasize the critical role of parents in affirming the child's development and choices. • Through direct encounter with the child, assess the child's level of distress with their assigned sex at birth. • Offer multi-dimensional support, including: support groups for caregivers and youth, family therapy, parental coaching and child individual/family assessment. • Flexibility of modalities (individual, family and group). • Create thoughtful system of transfer of information between modalities and interventions. |

• Coaching parents empowers them to serve as a resource for their child, facilitates resolution of marital and parental discord around the child's gender nonconformity, and guides them through difficult decisions (e.g., social and medical transition). • Family sessions help support a positive and functional family climate, repair the relational bond between parents and child, and mobilize collaborative problem-solving to negotiate gender expression in and out of the home. • Multi-family groups provide parent/children with a community of peers dealing with similar questions and a processing space to reflect on their own experiences. |

| Bernal and Coolhart68 | Transgender children and youth and families | Family therapy | Case example | • Clinician serves in clinical assessment/gatekeeping role. • Advocate for children with family, school, and other providers. • Be knowledgeable of standards of care and medical intervention options to effectively counsel families (including risks and benefits, consent and custody issues, etc.). |

• Four areas of competencies for ethical treatment of trans youth and families: (1) Standards of care, letter writing, and GI development; (2) Community resources (groups, peers, providers); (3) Advocacy and sensitivity training in larger systems (incl. School training); (4) Updated research and sociopolitical context. • Informed consent and transparency of the opinion of the therapist are essential. |

| Coolhart et al.69 | TGNC youth and their families | Individual youth, parental and family counseling | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Support parents struggling with social transition and gender-neutral language with psychoeducation on family acceptance and blockers. • Connect families to support systems, groups, advocacy orgs, etc. • Connect youth to community and support resources beyond the family and school. • Use combinations of sessions with family together, youth alone, parents alone, and extended family. • Family assessment should include gathering information about the child's gender development, early childhood, etc. and assessing family attitudes and behaviors. • Therapist should play an active role in the school context by training and capacity-building. |

• Working with parents alone is particularly important if parents are rejecting or struggling to accept. • Article describes an assessment tool for youth readiness for medical treatment. |

| Harvey and Stone Fish70 | Queer youth and families | Intersectional systemic treatment | Three clinical case examples | • Hold complexity and multiple aspects of youth and family experience, including homophobia and need for love, and empathy. • Provide psychoeducation and guidance regarding coming out and social issues. • Connection families to community and resources for queer youth. • Facilitate a safe space that can provide honesty and compassion while tolerating difference. • Maintain awareness of the effects of multiple cultural contexts and identities. • Maintain awareness of the effects of power dynamics and oppression. • Help parents in accepting and integrating queerness into the family by providing an expanded vision of family life. |

• Takes an intersectional and queer-affirmative approach. • Honors hidden resiliency and the “gift of queerness.” |

| Giammattei71 | TGNC families | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Ask clients their name, pronoun, and gender description, and use these when interacting with the family. • Share research with parents showing positive effects of family support and role models on transgender youth. • Give parents a space to discuss and grieve for lost hopes and dreams for their child (support groups can help with this). • Couples therapy and parent coaching may be warranted if parents differ in support. |

• Parents may need to reconcile beliefs, understand fears, and grieve loss of dreams they had for child before they can truly support their transgender child. • Families may need tremendous support in navigating social transition. • Parents may particularly struggle with nonbinary gender identities. • Model of family therapy is less important than for the treatment to be affirming of clients' identities. |

| Wahlig72 | Transgender children and their parents | Not specified | Not specified | • Be knowledgeable of multiple models of loss to better support the variety of family member reactions to transition. • Guide families to label the ambiguous loss as a major source of stress. • Meet with multiple family members so that individual perspective can be expressed and heard by others. • Provide psychoeducation regarding transition and normalize grief responses. • Direct families to other peer and professional resources (e.g., parent support groups). • Provide a safe space for parents to find meaning in their loss. • Explore role changes and potential renegotiations with families. |

• Parents may experience both types of ambiguous loss—psychological presence and physical absence, and physical presence and psychological absence. • Treatment goal is to develop a greater ability to tolerate the ambiguity of the “loss,”73 which can be impacted by the family's cultural beliefs and values. • Both physical and psychological connection of the family can be a source of resilience. • Some parents may not experience loss or may be more equipped to handle its ambiguity. |

| Whyatt-Sames74 | Transgender children in foster care | Gender-affirmative model25 and MDFA43 | Single case study | • Maintain a nonjudgmental stance and allow the child to guide social transition. • Assess pros/cons of social transition with the child. • Identify necessary changes for social transition, develop a timeline, and utilize role-play to anticipate changes. • Utilize multiple treatment approaches (e.g., parents alone, child alone, family together). • Regularly assess progress. • Identify and engage all stakeholders (i.e., family members). • Have families use local support resources (e.g., LGBT groups). |

• Treatment recommendations based on the gender-affirmative model and the MDFA.25,43 |

| Coolhart and Shipman75 | Families of TGNC youths | Gender-affirming family therapy | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Two-stage model of treatment: (1) Assessing and increasing family attunement; and (2) Exploring and supporting gender expression and transition. • Assessment should evaluate whether the child's gender is persistent, consistent, and insistent. • Utilize different modalities for treating families (i.e., treat family together and subsystems separately) • Provide group treatment for families. • Involve multiple generations in treatment. • Provide psychoeducation on gender and treatment to families. |

• “Both/and” approach involves being attuned to parents' reactions while affirming/protecting the child • Goal is to help families understand, become attuned to, and become advocates for their child. • Advocacy is important in care as well as in larger social contexts (e.g., school). • Flexibility is important in treatment pace and clinical configuration. • Alliance with parents is key to success in treatment. |

| Ehrensaft et al.42 | Trans youth and their families | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Link youth and families with peer support resources. • Provide families with psychoeducation on gender identity and TGE family issues. • Promote parent engagement as a risk prevention strategy. • Emphasize the importance of professional and peer support for family acceptance. • For social transition, differentiate gender identity from expression, balance affirmation with safety, and consider affirmation as nonbinary. |

• Families can socially transition their child well without family therapy or help of professionals. • Clinical approaches of (prepubertal) gender-expansive children fall under three categories: reparative, watchful waiting, and affirmative. • Mental health providers are particularly important before puberty because medical treatment is not necessary at this stage. |

| Bull and D'Arrigo-Patrick76 | Parents of transgender children who are transitioning | Not specified | Phenomenological methodology, face to face interviews (n=8) | • Hold the loss narrative loosely and engage with curiosity. • Frame social transition as family-level event (i.e., “big T” vs. “little t” transition). • Explore intersecting identities (race/ethnicity, religion, etc.). • Explore the parents' relationship to records of youth (e.g., photos) from pretransition and what purpose they serve. • Connect families to resources in their communities. |

• Stands out because using a certain form of technology, centers parents experience (as opposed to whomever created the questions) |

| Coolhart et al.77 | Transgender male youth (n=6 families of trans male youth) | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Help parents verbalize array of feelings (including ambiguous loss). • Identify positive, useful, and relevant coping strategies. • Use therapy as a space for parents to tell stories of the child they feel they are losing and listen to other family members' experiences. • Connect parents with other parents of trans youth to share experiences. • Explore the dynamics of family's gender and how this impacts experiences of the child's transition. |

• Ambiguous loss encompasses physical absence and psychological presence, as well as physical presence and psychological absence. |

| Abreu et al.78 | Transgender and gender diverse children and their parents | Not specified | Systematic literature review | • Acknowledge and normalize negative family reactions to the child's coming out. • Help families to increase cognitive flexibility, develop affirming values, cultivate positive meaning-making, and create narratives of strength and hope for the TGE child. |

• Family members experience trans-related stigma by empathizing with TGE youth, which can increase risk for mental health problems in family members. |

| Ashley79 | Transgender and gender creative youth | Not specified | Not specified | • Be attentive to potential of being over supportive of binary transgender identity (which can lead to perception that child will only be accepted if trans, and hamper development of nonconforming gender expressions). • Respect (and help families respect) the child's wishes for social transition. • Be aware of potential clinical biases before treating and maintain critical openness to being wrong about assessments of treatment readiness due to these biases. • Integrate the work of trans communities and scholars into clinical work. • Seek to understand how/why families struggle with their child's gender and support parents in their difficulties with their child's gender by working alongside support groups for parents of trans youth. |

• Social transition facilitates, rather than inhibits, gender exploration. • Clinical hesitancy for puberty blocking treatment is unjustified. • Goal should not be to assess the child's gender, but rather to provide them with the tools to explore their gender. |

| Edwards et al.80 | Transgender people and their families | Ecological Systems Theory81 | Not specified | • Assess family resilience, strengths, and available sources of support. • Reflect on one's own power/privilege and how one's identity affects the therapeutic relationship. • Consider family's' experiences through an intersectional lens. • Prioritize the child's expressed goals. • Maintain lists of current and affirming medical and community resources for families (including support groups and advocacy organizations) and connect families to broader LGBTQ community. • Support all family members through transition and reorganization of family structures, while emphasizing flexibility. • Ensure clinic environment is affirming (e.g., inclusive materials, all-gender bathrooms). • Promote laws supporting transgender families and visibly advocate for the community by attending advocacy events. |

• Framework was adapted from Ecological Systems Theory,81 which views human development as an interaction between the individual and multiple nested systems (relational, community, and societal) at a particular time. • Article speaks about transgender individuals of all ages but recommendations not particularly applying to youth and their families. |

| Hidalgo and Chen82 | Families with transgender/gender-expansive prepubertal children | MDFA-based treatment43 | Results of qualitative research with cisgender parents on experiences of gender minority stress | • Use parent psychoeducation and coaching to help parents build gender-affirming capacity. • Cognitive-behavioral approaches (e.g., cognitive restructuring) can be used to target parents' negative future expectations regarding their child. • Parental coaching builds off psychoeducation by promoting parents as resources and decision-makers for issues related to child's well-being. • Consider integrating mindfulness and acceptance strategies with parents. |

• Topics for psychoeducation can include gender development, research findings, pediatric gender dysphoria, and importance of parental acceptance and advocacy. • Nonaffirming family members may be more amenable to acceptance than rejecting family members. |

| Golden and Oransky83 | Transgender adolescents and their families | Gender-affirmative family therapy | Four case studies | • Challenge own assumptions about identities and treat families as experts in their own identities and experiences.84 • Provide youth-focused individual and group therapy to address family and societal rejection, as well as resulting psychopathology. • Use parent individual therapy and support groups to help them understand how intersecting identities influence reactions to their child's gender (including understanding parental identities). • Explore risks the adolescent may face that may be compounded by other identities. • Work with families to understand how their identities support/restrict their ability to affirm their child. |

• Incorporate tenets of intersectionality.85 • Family reactions to the child's gender are often embedded in the context of other aspects of identity, and support is best accessed when placed in the context of these identities. • Families return to therapy together once they gain psychological and social resources that have validated their identities and understood their point of view. |

| Miller and Davidson86 | Young people with diverse gender identifications and their families | CMM | Two case studies | • The first meeting can provide an opportunity for the clinician to discover families' stories and hopes for treatment. • When there is disagreement within families, have members collaborate and consider if it's possible to move forward while holding different perspectives. • Use circular questioning to make connections between family's stories, meanings, and different contexts. • Consider different aspects of family members' identities and how they may impact how they define and conceptualize their gender. • Meet with schools and other extra-familial networks to negotiate supportive outcomes, while supporting the perspectives of all parties. • Use “both/and” approach to understand reciprocal influence of individual and social contexts on understanding of gender and foster nonjudgmental acceptance of gender identity issues. • Collaborate with professionals from different specialties (e.g., pediatric endocrinologist). • Allow mourning processes to occur • Foster hope in youth and their families. |

• Therapeutic aims derived from Di Ceglie.87 • Three principles of CMM: (1) there are multiple social worlds, (2) social worlds are made in interactions and through conversations with others, and (3) we are all active agents in the making of social worlds.88 • Conceptualization of gender fits well within a social constructionist paradigm. • CMM facilitates collaborative relationships and having families “constructing gender together.” |

| Okrey-Anderson and McGuire89 | Gender minority youth and their families | Not specified | Not specified | • Support families that worry that support for their gender minority child will lead to ostracism from their religious or social community. • Be careful with unsolicited psychoeducation, which may result in defensiveness and resistance in conservative or religious families. • Establish rapport, foster trust, and assist families to navigate relationships without condemning families or affirming transphobic attitudes • Seek opportunities to increase competency in working affirmingly with gender minority youth and their families. |

• Selective positioning and value-based referrals are ineffective, because religious practitioners may need to treat a religious family with a gender minority child. • Advising partial or conditional support can negatively impact the child and family. • Cognitive flexibility can lead to closer and more stable relationships with gender minority youth through the coming out process. • Feelings of ambiguous loss are more likely to occur in conservative religious families where there is strong emphasis on traditional gender roles. • Families may need to distance themselves from strict theology and family expectations to develop resilience, cognitive flexibility, and stronger relationships with their gender minority child. |

| Oransky et al.90 | TGNC adolescents and young adults | Family therapy drawing from MDFA43 and Family Acceptance Project91 | Case example | • Intervene (or have child do so on their own behalf) in transphobic discrimination by educating school personnel on rights of TGNC students and the impact of discrimination on their mental health. Remove barriers to care (treating those without insurance, provide multiple avenues for program entry, etc.) and connect with legal experts who can help with name/gender changes on documentation. • Ensure staff/clinicians, forms and clinic environment are affirming and welcoming • Coordinate care with other health providers ( medical doctors, social workers, etc.). • Provide early psychoeducation regarding effects of transphobia and the importance of an affirmative approach to care. • Utilize a variety of treatment modalities (parental coaching, child therapy, family therapy, parent support groups, etc.). • Explore caregivers' assigned meaning to gender and validate their fears and concerns. • Use DBT/CBT approaches adapted for use with TGNC populations. |

• Encourage use of group treatment for TGNC youth to foster community support and peer education in responding to minority stress. |

| Reilly et al.92 | Young children with gender nonconforming behaviors and preferences | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Resist prematurely predicting the child's path in terms of gender identity development. • Have parents explicitly tell the child they're exploring together “what feels right,” and that the family will support any outcome (i.e., “follow the child's lead”). • Have families consider an open social transition rather than “going stealth.” • Acknowledge to parents that the child's gender nonconformity represents a deviation from their envisioned child. |

• Parent support groups can help families navigate the complexities of gender dysphoria/transition. • It is preferable to have families open about the child's gender nonconformity with extended family, community, and school. • Families may experience child's gender nonconformity as a loss of the child they dreamed of and initially had. |

| Wren93 | Gender diverse children and adolescents | Not specified | Not specified (recommendations derived from clinical experience) | • Build with families a shared understanding of the child's gender identity development. • Assess for current/past distress and make sense of its associations with gender conflict and desire for bodily change. • Explore with child motivations for seeking gender-related treatment. • Consider the meaning of sexual intimacy and fertility for the developing young person. • Communicate to families at all stages the known/unknown benefits/drawbacks of proposed interventions. • Assess youth for capacity for consent and scaffold such discussions appropriately. • Acknowledge how social, personal, and professional locations lead to certain biases. • Work with other stakeholders to build affirming public attitudes toward gender nonconforming youth. |

• Clinicians should be aware if the treatment given is in the best interest of the child |

CMM, Coordinated Management of Meaning; DBT/CBT, dialectical behavior therapy/cognitive behavioral therapy; GID, gender identity disorder; GLBT, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender; LGB, lesbian, gay, and bisexual; MDFA, Multi-Dimensional Family Approach; N/A, not applicable; SGM, sexual and gender minority; SGMT, sexual and gender minority therapy; TGE, transgender and gender expansive; TGNC, transgender or gender nonconforming.

Review 2: Family therapy for LGB youth

A similar review process was undertaken for articles on family therapy interventions with sexual minority youth. For this second review, however, only articles that provided quantitative outcome data were considered for inclusion. For inclusion in the second review, articles must have met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the article was published in English, and (2) the article provided quantitative outcome data related to family therapy or interventions to increase family engagement with sexual minority youth. Articles were excluded from the second review if they (1) were not related to sexual minority youth, (2) addressed issues of sexual orientation or identity in the context of individual or group therapy, rather than family therapy, or (3) only provided treatment strategies, best practices, clinical recommendations, or research results regarding sexual orientation or identity outside the family context.

As with Review 1, the final set of articles that met all inclusion and exclusion criteria for Review 2 (n=2) were then coded for the following information: (1) population of interest, (2) treatment modalities used, (3) outcome data (if any) and/or empirical support, (4) clinical strategies suggested, and (5) additional relevant themes explored. A summary of this information is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Articles with Quantitative Outcome Data for Family Therapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth (Review 2)

| Citation | Sample of interest | Treatment modalities | Outcome data/empirical support | Clinical strategies | Additional themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willoughby and Doty94 | Nonheterosexual youth and their family (n=1) | Brief CBFT | Moderate increases in GARF scores over the course of treatment. Subjective parent-reported increase in comfort with son's sexual orientation |

• Teach listening and problem-solving skills to bolster adaptive family functioning and support family adjustment of sexual identity. • Addressing the family members' cognitions that influence family life will have to be addressed to modify dysfunctional family patterns. • Identify and challenge automatic thoughts (e.g., “this is a phase” or “We've failed as parents”) that are reflective of cognitive schemas. • Provide psychoeducation related to sexual identity. • Assign and check homework assignments (e.g., contact with gay people). • Expose families to salient topics and have them stay with the emotions they elicit. • Provide behavioral alternatives that increase positive family interactions, as well as communication and problem-solving skills. • Family communication: speaker listener, ask history of sexuality in supportive place |

• Important to be able to define the crisis that brought the family in and establish agreement among family members about what the central problem is. • Maintain a directive stance in entering into the family to actively introduce change |

| Diamond et al.95 | Self-identified LGB suicidal adolescents and their parents (n=10) | Attachment-Based Family Therapy | Significant decreases in suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms over the course of treatment. Nonsignificant decreases in attachment-related anxiety and avoidance over the course of treatment |

• Spend increased time with parents to help reconcile religious beliefs with child's sexuality, address fears about rejection from family of origin, and address concerns for child welfare. • Focus early on promoting access to and participation in LGB-affirmative resources. • Help parents gain access to educational materials about positive LGB lifestyles and community support (e.g., PFLAG). • Help adolescents reframe acceptance as an ongoing process. • Identify and eliminate potentially invalidating parental comments or behaviors (i.e., microaggressions). |

• Conversations with both parents and adolescents about acceptance allow them to work through the acceptance process together without breaking the attachment bond. |

CBFT, cognitive-behavioral family treatment; GARF, Global Assessment of Relational Functioning; PFLAG, Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays.

Results and Discussion

The first review (quantitative and qualitative research articles on family-based interventions with TGE youth) yielded 32 articles examining family-inclusive interventions with TGE youth (Table 1), whereas the second review (quantitative research articles on family therapy with LGB youth) yielded only two studies (Table 2).

Quantitative data

As previous research suggested,48 this review found that there is a glaring absence of quantitative outcome data on family therapy and family-based interventions with LGBT youth in general and with TGE youth in particular. Put simply, this review yielded no published quantitative outcome studies demonstrating the efficacy of family therapy interventions with TGE youth. Only one study provided outcome data regarding the application of evidence-supported Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT)35 to LGB youth.95 Developed by Gary Diamond and his team, ABFT is based on the premise that family relationships are improved by identifying and attending to attachment ruptures, such as family rejection and cutoffs, between family members. This small study (n=10) of LGB adolescents in Israel with a history of suicide attempts shows that ABFT leads to a significant decrease in suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in sexual minority youth.95 It also shows a moderate (but nonsignificant) decrease in attachment-related anxiety and avoidance, indicating that treatment may have resulted in improved parent–child relationships.

Qualitative data

Although there are no quantitative outcome studies on family therapy or family-based interventions with TGE youth, there are: (1) a small number of qualitative studies (n=6) based on small samples of caregivers, (2) case studies (n=9) arguing for the effectiveness of family-based interventions for TGE youth and their families, and (3) a large number of clinical recommendations and a few theoretical models based on authors' clinical and research experience often spanning up to decades (n=17).24,42,43,63,69–71,96 Of note among these qualitative data are: (1) the change of clinical stance on families of TGE youth over time, (2) the theoretical models often cited and used, (3) the most frequently recommended best clinical practices when working with TGE and their families, and (4) the commonalities of these best practices with outcome data on family therapy with LGB youth. We explore the results in these four domains hereunder.

Change of the clinical stance over time

Table 1 organizes the included articles in chronological order and emphasizes how the stance on family care for TGE youth, including prepubertal children, has shifted over time. Approaches have generally evolved from a gender diversity pathologizing to a gender diversity affirming stance.97

Articles published between 1972 and the late 1990s reflect a clinical position anchored in traditional interpretations of the psychodynamic model, where gender diversity was considered an emotional and developmental disorder to treat and correct. Families (often mothers) were blamed for causing noncisgender identifications (e.g., “effeminate” or “feminine”) in male-assigned at birth children mostly.58,59 Such an understanding of gender diversity in childhood was used to justify an approach generally described as “reparative,” where cisnormative gender roles and identifications were encouraged, and transgender and nonbinary identifications and expressions were “avoided.” This stance discourages social transition and promotes adherence to cisnormative gender identity and expression in children and families.58,59 Parents were most often assessed for psychopathology and engaged in parent–child sessions to reinforce gender stereotypical identifications in the family.

The rise of more rigorous research on gender diverse pre- and postpubertal children from the (now-called) Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam led to the establishment of a second approach.98 The commonly known “Watchful Waiting” model argued that, in part based on longitudinal outcomes of a small sample of gender-diverse youth in the Netherlands, 73% of noncisgender identifying prepubertal children studied would desist at adolescence, not identify as transgender, and not pursue gender affirming medical care (yet scholars have argued with the validity of these findings).25,97,99–103 Extrapolating from these numbers, the model argues that the safest approach would be to block and delay genetically induced puberty to allow children and families additional time to clarify whether adolescents identified as transgender and seek permanent medical interventions such as cross-sex hormone therapy and surgeries. We owe to this model the establishment of puberty suppression as a global standard of care. In this model, the approach to families is supportive and aims at providing psychoeducation on gender identity development; decreasing gender dysphoria, stress, and stigma related to gender diversity; and decreasing family rejection.98

A third and last model emerged around 2010, under the umbrella of gender-affirmative approaches.25,43,46,96,97 This model argues that the differentiation between TGE and cisgender children could be made at an earlier stage of the child's development than previously thought.104 Proponents of this model recommend social transition as an affirmative intervention with prepubertal and postpubertal children. A gender social transition or social affirmation refers to a change in gender expression of a child such as hair, pronoun, clothing, or name in a particular setting to align more closely with their gender identity. Partial transition/affirmation indicates the child lives in their affirmed gender part of the time (i.e., at home only) and full transition/affirmation in all social settings (i.e., school, extended family, and community). This model also recommends puberty blocking intervention at Tanner Stage 2 and cross-sex hormonal therapy at an age closer to the genetically induced puberty in cisgender children. The approach to families of origin and caregivers is supportive and psychoeducational, and aims to increase family acceptance of gender diversity in the child, family, and community.24,46,96 Over the past few years, the gender-affirmative model has increasingly emphasized the inclusion of nonbinary identifications and expressions, as well as considerations of the racial, class, cultural, and religious identities of the child and of their family.71,79,83,105,106 There is consensus that a gender-affirmative approach is absolutely necessary to support families, decenter cisnormativity, and embrace gender diversity. This model of care must be family inclusive and should incorporate family engagement and psychoeducation while attending to caregivers' experiences of minority stress in raising a TGE child.24,46,82,96 All gender-affirmative approaches share the importance of: (1) affirming the child's gender identity from the onset of clinical interactions by adopting chosen name and appropriate pronouns in the clinical setting; (2) evaluating the child's mental health, developmental and community needs; and (3) addressing previous family ruptures, traumas, and rejections, related and unrelated to gender identity development.

Theoretical family therapy models

Under the gender-affirmative umbrella, the search yielded three models focusing specifically on family-based interventions: “Transgender Family Emergence,”63,96 the “Multi-Dimensional Family Approach,”43 and “Working Toward Family Attunement,”69 all of which conceptualize the clinical support of families of TGE youth based on the extensive clinical and/or research experience of their respective authors.

These frameworks commonly conceptualize the family processes of caregivers of TGE youth as nonlinear stage models that span from rejection and/or shock to acceptance and/or attunement, and from coming out to integration of diverse gender identities into the family system. They all emphasize attending to the youth's well-being, clinical needs, and identity development, as well as the caregivers' experiences, needs, parenting processes, and identity development. Although it is not always explicitly stated, they tend to focus on the experiences and processes of cisgender and nonqueer-identified caregivers. All models share a multifactorial theory of change, emphasizing the need to work on multiple aspects of the family experience: supporting individuals, increasing relational attunement and empathy, assessing and modifying gender norms and expectations within the family system, and mobilizing family members to work toward changing social gender norms in their larger contexts (community, medical, educational, legal, political, etc.).

Common atheoretical clinical recommendations

The results in Table 3 summarize the common recommendations for optimal clinical care included in the 26 articles published after 2000 under a gender-affirming stance on youth and families. These recommendations provide an atheoretical framework for best practices with gender diverse youth and their families that are repeated across multiple authors, service contexts, and geographic locations. Table 4 displays whether each respective reference includes any of the most common clinical recommendations and the total frequency of each recommendation across gender-affirmative references.

Table 3.

Clinical Recommendations for Family Therapists Working with Transgender and Gender Expansive Youth and Their Families

| 1. Provide caregivers with psychoeducation on gender diversity, gender identity development, medical and social interventions, youth and family resilience. |

| 2. Provide caregivers space for their own process, including negative, neutral and positive reactions such as grief, fear, loss, surprise, sadness, joy, relief, gratitude, desire to support and advocate. |

| 3. Frame family acceptance and engagement as youth protective factor. |

| 4. Use multiple modalities and interventions flexibly: work with families all together, work separately with caregivers, siblings and youth, groups and community gatherings. |

| 5. Facilitate access to advocacy and training supporting allyship in extended family and community, including training for schools, places of faith, caregiver's workplace, etc. |

| 6. Connect with community of peers, youth and adults, including other families, support groups, community-based resources to increase connection and reduce isolation. |

| 7. Center intersectional and contextual approaches including race, class, religion, legal statuses in all dimensions of care and services. |

Table 4.

Frequency of Recommendations in Transgender and Gender Expansive Youth Only

| Citation | Recommendation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provide psychoeducation | Provide space for caregivers' process | Family acceptance protective factor | Use multiple intervention modalities flexibly | Facilitate access to advocacy | Connect with community | Center intersectional approach | |

| Green et al.56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Higham57 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Newman58 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wrate and Gulens59 | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | — |

| Bradley and Zucker60 | — | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sugar61 | — | — | — | ✓ | — | — | — |

| 1. Saeger62 | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — |

| 2. Behan64 | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — |

| 3. Butler65 | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4. Lev66 | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | ✓ |

| 5. Parker et al.67 | — | — | — | ✓ | — | — | ✓ |

| 6. Malpas43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 7. Bernal and Coolhart68 | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | ✓ |

| 8. Coolhart et al.69 | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — |

| 9. Harvey and Stone Fish70 | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | ✓ |

| 10. Giammattei71 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — |

| 11. Wahlig72 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 12. Whyatt-Sames74 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — |

| 13. Coolhart and Shipman75 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 14. Ehrensaft et al.42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — |

| 15. Bull and D'Arrigo-Patrick76 | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 16. Coolhart et al.77 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | ✓ | — |

| 17. Abreu et al.78 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — |

| 18. Ashley79 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | ✓ |

| 19. Edwards et al.80 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 20. Hidalgo and Chen82 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — |

| 21. Golden and Oransky83 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 22. Miller and Davidson86 | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | — | ✓ |

| 23. Okrey-Anderson and McGuire89 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | ✓ |

| 24. Oransky et al.90 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 25. Reilly et al.92 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | — |

| 26. Wren93 | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ |

| Total of 26 | 22 | 21 | 19 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

Provide psychoeducation

Twenty-two of 26 articles specifically articulate the need to educate caregivers about gender diversity. Authors recommend that family engagement and guidance include three clusters of content, covering: (1) the differences between the continua of assigned sex, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual/romantic orientations; (2) the standards of multidisciplinary care for prepubertal and adolescent TGE youth, including social transition, nonbinary affirmation, hormonal and surgical interventions, legal advocacy and rights/support in school; and (3) the stages of gender identity development for transgender and cisgender family members, including studies about the developmental trajectories of TGE youth, and a balanced set of information about adult transgender and nonbinary lives, highlighting both risks owing to transphobia and the resilience of TGE communities. Psychoeducation should not be patronizing or imposed on families and caregivers at the expense of forming a strong alliance; instead, many authors recommend distilling it as part of an open inquiry about caregivers' fears, misconceptions, and desire for agency and information.

Provide space for caregivers' process

Twenty-one of 26 articles advise providers working with family members to conceptualize, plan for, and offer separate and confidential supportive spaces where caregivers can freely share their experiences, struggles, fears, feelings, and questions regarding their TGE child. These articles identify the relevance of such spaces beyond the intake appointment, lasting along the entire family treatment duration. Attention paid to caregivers should be properly balanced with providing youth with individual and peer support, access to community resources, and advocacy to ensure their safety and wellbeing. A separate support space allows caregivers to process their experience at a different pace and using a language that, while authentic to their own experience, might not affirm their child. For instance, while it is best practice for the therapist to use the pronouns that the TGE young person uses for themselves,107 it is sometimes impossible to initially engage a caregiver while imposing a use of language that they oppose. Comparable with the empirically validated ABFT approach to LGB youth and their families,95 parental coaching, by spending extended and confidential time focusing on the caregivers and their experiences, informs clinicians on the caregivers' history, upbringing, socializations, values, and affiliations. A layered and complex understanding of the family members' perspectives elucidates the identification of the family's idiosyncratic and cultural experience of gender, parenting, safety, resilience, cultural loyalty, and room for change. These conversations often reveal specific conflicts of values, including cultural and/or religious dilemmas and fears experienced by the family. It also allows addressing marital or family conflicts regarding the handling of the child's gender diversity outside the presence of the young person.

Frame family acceptance/engagement as a protective factor

Nineteen of 26 articles recommend that the clinician establishes the very participation of the family in support of their TGE child as one of the most effective and empirically validated modes of protecting their young person from negative developmental, social, and emotional outcomes. Caregivers engaged in family therapy are invited to share a common framework, beyond specific interventions and activities, that “[family] acceptance is protection” (p. 468).43 This treatment philosophy rests on the research of the Family Acceptance Project.21,91 If youth experience love, acceptance, and respect at home—whether in the form of nonviolent communication, use of appropriate name and pronouns, or approval of binary or nonbinary gender expression fitting with the child's identity—they are much less likely to be depressed, anxious, self-harming, or suicidal. They are also better equipped to deal with a binary and transphobic world, knowing that their true self is seen and embraced at home. However, the notions of what each family and community consider most protective should be discussed openly and in a culturally humble way. The systemic oppression and violence experienced by Black and POC families and youth at the hand of law enforcement or social service agencies,108,109 as well as the intracommunity violence against gender diverse youth, specifically transgender feminine persons of color,110 need to be acknowledged when discussing what behaviors each family member considers to be safe. Ultimately, facilitating consensus around the pros and cons of safety strategies might help families have more honest conversations and more effective mutual support.

Use multiple intervention modalities flexibly

Eighteen of 26 articles demonstrate or recommend that youth and families are supported through a flexible and multidimensional setting that allows the family process to unfold through sessions with the young person alone, with the caregivers alone, and with the entire family. It is a departure from more traditional systemic models of family therapy that tend to favor family-as-a-whole sessions as the normative set up.111,112 In addition, supportive services offered to families should go beyond the treatment of the family as a unit and incorporate community building (support groups, listservs, community-based referrals) and work of liaison, advocacy, and education. The flexible structure of treatment reflects the fact that caregivers and youth have wildly different needs, paces, and require sometimes conflicting sensitivity from the clinician or different support in their respective communities.113

Facilitate access to advocacy and training for family and community

Eighteen of 26 articles recommend that family engagement includes extended family and community, such as key community members and professionals that the family intersect with regularly (i.e., pediatrician and medical teams, teachers and school administration, after-school and camp staff, caregivers' workplaces and colleagues, and members of the family's religious community). The engagement should center the youth and family's sense of consent and agency in their respective communities, while lifting up their burden to educate and advocate in isolation. Such community and advocacy work can be performed by a multidisciplinary team working with the primary clinician or by the clinicians themselves, depending on the availability of resources. Providing training and/or advocacy in schools, medical teams, and other social networks is not only a relief for the youth and family who does not need to do it themselves. It also demonstrates that the treatment philosophy, regardless of its theoretical underpinning, is deeply embedded in a social justice framework, questions institutionalized binary cisnormativity, whether in child development or in educational policies, as well as facilitates the change of gender norms of the professional and social communities with which the family frequently interacts.

Connect with community of peers—youth and adult

Seventeen articles of 26 include connecting youth and caregivers to a respective community of peers. Whether it is a support group for children, teens, and/or caregivers, a listserv, or a community-based network, two-thirds of gender affirming authors agree with the necessity to complement purely clinical support with a community-building approach. Indeed, the sense of marginalization and isolation experienced in social settings that privilege cisgender youth and only focus on raising cisgender youth can be counterbalanced by participating in a community-sharing comparable dilemmas, fears, and discoveries. Trans and nonbinary youth groups allow young people to experience their journey as normative and find great relief and joy in connecting with other youth who understand their questions and priorities. Similarly, caregiver groups are an endless source of referrals, information, and validation for families embracing gender diversity. The positive impact of participating in peer groups—whether peer and/or professionally facilitated—is commonly highlighted by most clinicians and researchers. Being surrounded by a diverse group of peers who share the same social and developmental dilemmas profoundly shapes youth and caregivers' sense of normalcy and decreases their sense of social alienation.

Center intersectional and contextual approaches

Sixteen of 26 articles illustrate the importance of taking into account the racial, ethnic, economic, linguistic, religious, and legal status of each family as a foundational ingredient for successful and idiosyncratic engagement with each youth and family. What works best for Black families might be different from what is optimal for Asian communities; what is trust-inducing to White upper middle class folks might be very anxiety-provoking to an undocumented Latinx family. Cultural adaptations and sensitivity should not be considered as add-ons or after thoughts, but instead need to frame the entirety of the process, from the conceptions of gender and family to the social locations of the clinical team. Ensuring access by removing any potential barriers to care—whether financial, geographic, linguistic, and/or cultural—should be a priority in designing the support for all families.

Commonalities with family therapy with LGB youth

It should be noted that many of the most commonly recommended practices with families of TGE youth are close, if not similar, to the only empirically validated model of family therapy for families with LGB youth, ABFT.95 Flexibility of modalities, affirmative language while making room for caregivers' process, length of treatment, and importance of community connections and service resources are all common features established to decrease youth distress and to positively impact family acceptance. Diamond et al. specifically note that, when used with LGBT youth, ABFT should be adapted with increased time spent with caregivers alone to address fears, negative emotions, cultural beliefs, and personal experiences, as well as helping the young person to reframe family acceptance as an ongoing process.95

Limitations and Conclusions

This systematic review of English-speaking peer-reviewed articles confirms the absence of youth and family outcome data as well as empirical research on the specific mechanisms of effectiveness of family therapy and family-based services for TGE youth. It also highlights that the stance of family-based interventions with TGE youth was originally reflective of the pathologization that the mental health community had regarding gender-diverse children and individuals. It has taken several decades for the transphobic tone and cisnormative assumptions of many clinicians and studies to be replaced by approaches celebrating gender diversity in families. The systematic review of qualitative data, case studies, and theoretical approaches reveals a consistent and coherent number of clinical practices and approaches that, in absence of further evidence, can be considered best practice recommendations. These most commonly described features all include close attention to the individual youth, as well as caregivers, family, and community systems at once. They combine individual, family, and group interventions and point at best practices as a thoughtful integration of individual, family, and community health.

This being said, this review and its conclusions present several limitations and concerns. First, we are aware that calling for “intersectional inclusion” (i.e., racial, ethnic, and class) is not enough when acknowledging the realities and legacies of racial and ethnic systemic inequities in both research and service access for minoritized communities. Beyond noting the limitations of a search carried out within an English-speaking and Western context, we call for a deeper reflection on this process and its outcomes. Despite the merits of a protocolized systematic review process, such an epistemological method is embedded within the legacies of systemic exclusion of other voices and knowledges from the academy and beyond. Lack of representation of families and authors of color in these articles, as well as an inherent judgment placed on empirical study rather than decolonized or queered methodologies, have restricted our scope of inquiry and reinforced the White supremacy of the academy in our work. We call for an inclusion of alternative methods of knowledge creation and a change in the hegemonic power structures that dictate expertise in our field—often White, cisgender, and heteronormative.106,114–116 We also know and are limited by our own social locations as an all-White, cisgender authorship and our veil of Whiteness cannot and should not determine best practices for BIPOC communities furthering the legacies of colonialism and slavery.*

Second, further research (quantitative, qualitative, community-based, and participatory) should collect quantitative outcome and process data to provide systematic evidence for the efficacy of family-based interventions for TGE youth and, specifically, for the efficacy of the best practice recommendations highlighted by our search. Evidence-based modalities and practices (family therapy, family groups, etc.) could be tested further through replication and evaluation, paying particular attention to decolonizing methods and participation.

Abbreviations Used

- ABFT

Attachment-Based Family Therapy

- CBFT

cognitive-behavioral family treatment

- CMM

Coordinated Management of Meaning

- DBT/CBT

dialectical behavior therapy/cognitive behavioral therapy

- GARF

Global Assessment of Relational Functioning

- GID

gender identity disorder

- GLB

gay, lesbian, and bisexual

- LGB

lesbian, gay, and bisexual

- MDFA

Multi-Dimensional Family Approach

- N/A

Not applicable

- PFLAG

Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays

- PRISMA

Preferred Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SGM

sexual and gender minority

- SGMT

sexual and gender minority therapy

- SM

sexual minority

- TGE

transgender and gender expansive

- TGNC

transgender or gender nonconforming

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: Malpas J, Pellicane MJ, Glaeser E (2022) Family-based interventions with transgender and gender expansive youth: systematic review and best practice recommendations, Transgender Health 7:1, 7–29, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0165.

Mosley DV, Bellamy P.L. Academics for Black Survival and Wellness Training [Unpublished Online Training]. Academics for Black Lives. 2020. https://www.academics4blacklives.com/

References

- 1. Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. . Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex. 2010;58:10–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKay TR, Watson RJ. Gender expansive youth disclosure and mental health: clinical implications of gender identity disclosure. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2020;7:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, et al. . Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, et al. . Transgender and anxiety: a comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int J Transgend. 2017;18:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Millet N, Longworth J, Arcelus J. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in the transgender population: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Transgend. 2017;18:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marshall E, Claes L, Bouman WP, et al. . Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: a systematic review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi SK, Wilson BDM, Shelton J, Gates GJ. Serving Our Youth 2015: The Needs and Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth Experiencing Homelessness. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quintana NS, Rosenthal J, Krehely J. On the Streets: The Federal Response to Gay and Transgender Homeless Youth. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. . Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson EC, Garofalo R, Harris RD, et al. . Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:902–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, et al. . Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J Sex Res. 2015;52:243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, et al. . The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation's Schools. New York, NY: GLSEN, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dank M, Lachman P, Zweig JM, Yahner J. Dating violence experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:846–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, et al. . Childhood gender nonconformity: a risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics. 2012;129:410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rowe C, Santos G-M, McFarland W, Wilson EC. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among trans*female youth ages 16–24 years in the San Francisco Bay Area. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Westwater JJ, Riley EA, Peterson GM. What about the family in youth gender diversity? A literature review. Int J Transgend. 2019;20:351–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]