Abstract

Obesity in pregnancy is currently the leading cause of gestational complications for the mother and fetus worldwide. Maternal obesity (MO), common in western societies, impedes development of intestinal epithelium in the fetuses, which causes disorders in the nutrient absorption and intestine-related immune responses in offspring. Here, using a mouse model of maternal exercise (ME), we found that exercise during pregnancy protects the impairment of fetal intestinal morphometrical formation and epithelial development due to MO. MO decreased villus length and epithelial proliferation markers in E18.5 fetal small intestine, which was increased due to ME. The expression of the epithelial differentiation markers, Lyz1, Muc2, and Tff3, in fetal small intestine was decreased due to MO, but protected by ME. Consistently, the biomarkers related to mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism were downregulated in MO fetal small intestine but recovered by ME. Apelin injection to dams partially mirrored the beneficial effects of ME. ME and apelin injection activated AMPK, the downstream target of apelin receptor signaling, which might mediate the improvement of fetal epithelial development and oxidative metabolism. These findings suggest that ME, a highly accessible intervention, is effective in improving fetal intestinal epithelium of obese dams. Apelin-AMPK-mitochondrial biogenesis axis provides amenable therapeutic targets to facilitate fetal intestinal development of obese mothers.

Keywords: AMPK, exercise, fetal epithelium, maternal obesity, mitochondrial biogenesis

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of obesity in women at reproductive age is one of the primary etiological factors for the increasing incidence in gestational diseases and preeclampsia (1). It is well established that maternal obesity (MO) negatively affects metabolic health of mothers and the development of their fetuses (2–7). Notably, MO increases the incidences of cardiovascular and metabolic-related diseases in offspring later in life (8), which is partially mediated by epigenetic inheritance in tissues critical for metabolic homeostasis (9, 10).

Prenatal intestinal development involves extensive cell proliferation, differentiation, and maturation (11), of which mitochondria plays a key role (12). Consistently, pathological conditions such as obesity directly impair the proliferation and self-renewal of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) in mice (13). Consistently, MO induces intestinal inflammation of fetuses and offspring, which may predispose offspring intestine to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) (14). However, the effects of MO on mitochondrial biogenesis and fetal intestinal development remain to be studied.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key mediator of cellular metabolism, and its activation stimulates epithelial cell differentiation (15). We recently found that MO inhibits AMPK activity in fetal tissues, whereas maternal exercise (ME) activates apelin and apelin receptor (APJ; gene symbol, Aplnr) axis, which is known to stimulate AMPK activation (16, 17). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α) is a well-defined AMPK target (18). PGC-1α is a key metabolic regulator of intestinal epithelial cell differentiation (19) and stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism (20). We have also discovered that ME intergenerationally induces PGC-1α expression in fetal/offspring brown fat and skeletal muscle, which is mediated by activation of apelin signaling (16, 17).

Apelin, a peptide regulating glucose metabolism (21, 22), binds to the G protein-coupled receptor, which includes Gαq and Gαi proteins (23). Apelin was initially reported as an enteric peptide localized in the gastrointestinal tract, stimulating gastric/epithelial cell proliferation (24). In addition, apelin enhances the function of gastric epithelial barrier through activating AMPK (25), which is regulated by Gαq protein (23). Furthermore, AMPK promotes PGC-1α-related oxidative transition required for stem cell renewal and differentiation (26, 27), which constantly occurs in the gut epithelium (28).

Although the therapeutic role of exercise in pregnancy on fetal/offspring metabolism has been recognized, the intergenerational role of ME on the intestinal epithelium in regulating digestive capacity and metabolism remains unclear. Thus, we hypothesized that ME in obese mothers enhances fetal intestinal epithelial development, which is mediated by apelin-stimulated AMPK/PGC-1α activation.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

All animal procedures were conducted in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-approved facilities followed by the Animals in Research: Reporting In Vitro Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (29) and approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the Washington State University (ASAF No. 6704).

Mice

Female C57BL/6J mice (8 wk old; the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were randomly separated into two groups: a control group (Ctrl; n = 6 animals) fed a control diet (CD; 10% energy from fat, D12450J, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or an obesity group (n = 12 animals) fed an obesogenic diet (OB; 60% energy from fat, D12492, Research Diets) ad libitum for 8 wk. Then, after 1 wk of adaptation on the treadmill, female mice were mated with the same age male wild-type mice fed a chow diet. Pregnancy was determined by the presence of vaginal plug the morning after mating and considered as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). During pregnancy, the obesity group was additionally assigned into obesity without exercise (OB; n = 6 animals) or obesity with exercise group (OB/Ex; n = 6 animals). To whole of the small intestine of female and male fetuses were collected at E18.5 after 5 h fasting, and fetuses from maternal Ctrl mice were designated as M-Ctrl, those from maternal OB were designated as M-OB, and those from maternal OB/Ex were designated as M-OB/Ex (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Maternal exercise protects impairment of fetal intestinal development due to maternal obesity. A: study design of maternal obesity and exercise. B: illustration of intestinal structure. C: representative H&E images of villi and crypts in the fetal small intestine. Scale bar = 100 μm. D: mean of villus length (up) and crypt length (down) in female and male M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex fetuses (n = 6). Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB and #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 in M-OB vs. M-OB/Ex by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (D). M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice.

To explore the mediatory roles of apelin, after 8 wk of diet intervention (control diet vs. obesogenic diet) as described in the exercise study, animals were assigned to a control diet with PBS injection (CD/PBS; n = 6), an obesogenic diet with PBS injection (OB/PBS; n = 6), or an OB with [Pyr1]apelin-13 (0.5 µmol/kg/day; AAPPTec, Louisville KY) injection (OB/APN; n = 6). Apelin or PBS was intraperitoneally injected daily for 16 days from E1.5 to E16.5, as described previously (17). PBS was used for a control against apelin treatment. Two days after the last bout of exercise or apelin/PBS injection to avoid acute effects of exercise or injection, at E18.5, one female and one male fetus were collected from one dam after 5 h fasting (Fig. 4B). Genetic sex of fetus was determined by simplex PCR (30).

Figure 4.

Apelin supplementation enhances fetal epithelial development. A: cropped Western blots of apelin in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). B: research design of the apelin supplementation study. C: gene expression related to intestinal epithelium (Lyz1, Muc2, Tff3) in female and male fetal small intestine of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN (n = 6). D: cropped Western blots of MUC2 (up) and E-Cadherin (down) in female and male fetal small intestine of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN (n = 6). Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in M-OB vs. M-OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A–D). CD, control diet; CD/PBS, control diet with PBS; M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice; OB/APN, obesity with [Pyr1]apelin-13; OB/PBS, obesity with PBS.

Treadmill Exercise Protocol

Animals were subjected to daily aerobic treadmill exercise training for 16 days (E1.5 to E16.5), based on our established method (31). Briefly, 1 wk before mating, all female mice were subjected to acclimation on the treadmill for 10 min at 10 m/min intensity three times per week for a week. Animals performed treadmill (0° angle) exercise training every morning for an hour based on the three steps: warming up (5 m/min for 10 min), exercise (10–14 m/min for 40 min), and cool down (5 m/min for 10 min) (31).

Tissue Collection

At E18.5, small intestines, including duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, were collected from one female and male fetus per dam for gene expression and immunoblotting analyses. In an additional set of one female and male fetus per dam, small intestine was collected for histological analysis.

Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number

Mitochondrial DNA copy number was analyzed using NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (Nd1) normalized with the nuclear DNA lipoprotein lipase (Lpl; genomic DNA) via the PCR method, as previously described (17).

Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from the fetal small intestine by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). cDNA was synthesized using 500 ng of total RNA with an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Then, RT-qPCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). mRNA expression was normalized with 18S rRNA as previously reported (32), which was the most stable of three housekeeping genes tested (18S, 0.018; 36B4, 0.035; ACTB, 0.018; NormFinder) (33), and the expression level was calculated through a comparative method (2−ΔΔCt) (16, 32). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR analysis

| Gene Name | Forward/Reverse | Primer Sequence | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyz1 | F | 5′-GGAATGGATGGCTACCGTGG-3′ | NM_013590.4 |

| R | 5′-CATGCCACCCATGCTCGAAT-3′ | ||

| Muc2 | F | 5′-TCCTGACCAAGAGCGAACAC-3′ | NM_023566.4 |

| R | 5′-ACAGCACGACAGTCTTCAGG-3′ | ||

| Tff3 | F | 5′-TTGCTGGGTCCTCTGGGATAG-3′ | NM_011575.2 |

| R | 5′-TACACTGCTCCGATGTGACAG-3′ | ||

| Ppargc1a | F | 5′-CCATACACAACCGCAGTCGC-3′ | NM_008904.3 |

| R | 5′-GTGGGAGGAGTTAGGCCTGC-3′ | ||

| Tfam | F | 5′-CCAAAAAGACCTCGTTCAGC-3′ | NM_009360.4 |

| R | 5′-CTTCAGCCATCTGCTCTTCC-3′ | ||

| Cox7a1 | F | 5′-CAGCGTCATGGTCAGTCTGT-3′ | NM_009944.3 |

| R | 5′-AGAAAACCGTGTGGCAGAGA-3′ | ||

| Cpt1a | F | 5′-TCGCTCATTCCGCCGC-3′ | XM_036161416.1 |

| R | 5′-GAGATCGATGCCATCAGGGG-3′ | ||

| Cpt2 | F | 5′-TTCTGCAGTGCGGTTTCTGA-3′ | NM_009949.2 |

| R | 5′-GTGTCACTTCTGGCAGGGTT-3′ | ||

| Acadm | F | 5′-AGGGTTTAGTTTTGAGTTGACGG-3′ | NM_007382.5 |

| R | 5′-CCCCGCTTTTGTCATATTCCG-3′ | ||

| 18S | F | 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ | OW971800.1 |

| R | 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′ |

Immunoblotting Analysis

Protein extracts were prepared from fetal intestinal samples using a lysis buffer (100 mM Tris·HCl pH = 6.8, 2.0% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4). And the BCA Protein Assay Kit II (BioVision, Milpitas, CA) was used to determine the concentration of proteins. Primary antibodies included those against MUC2 (dilution, 1:1,000; NBP1-31231; RRID: AB_10003763; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), E-Cadherin (dilution, 1:1,000; Cat. No. 3195; RRID: AB_2291471), VDAC (dilution, 1:1,000; Cat. No. 4661; RRID: AB_10557420), p-AMPKα (dilution, 1:1,000; Cat. No. 2535; RRID: AB_331250), t-AMPKα (dilution, 1:1,000; Cat. No. 2532; RRID: AB_330331; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), PGC-1α (dilution, 1:1,000; Cat. No. 66369-1-Ig; RRID: AB_2828002), Apelin (dilution, 1:500; Cat. No. 11497-1-AP; RRID: AB_2877771; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL), COX4 (dilution, 1:500; Cat. No. sc-376731; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), PRDM16 (dilution, 1:1,000; PA5-20872; RRID: AB_11154178; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL), and β-tubulin (dilution, 1:200; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). Secondary antibodies are anti-mouse (dilution, 1:10,000; IRDye680) and anti-rabbit (dilution, 1:10,000; IRDye800CW; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Protein bands were detected by an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) (32).

Histological Analysis

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunocytochemical (ICC) staining, fetal small intestines were embedded in paraffin after 24 h of fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Five-micrometer-thick sections were used for H&E or MUC2 (NBP1-31231; Novus Biologicals; dilution 1:50) ICC staining, as described previously (4). Then, anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 555 secondary antibody (Cat. No. 406412; BioLegend, San Diego, CA; dilution 1:200) was used. Images were generated by a microscope (EVOS XL Core Imaging System (Mil Creek, WA) and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, NIH) (17). Three randomly selected images per sample were utilized and the definition of villi length and crypt depth were followed according to Fig. 1B.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS (IBM, Corp., Armonk, NY), visualized by Prism, Ver. 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and presented as means ± SE. Regarding to the sample size, statistical power was determined based on our previous studies (n = 6; 80% power, α = 0.05) (4, 32, 34). For the statistical analysis of differences among three groups, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc (Tukey’s test) analysis was used. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, and no samples or animals were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

Maternal Exercise Protects against Impairment in Fetal Epithelial Development Due to Maternal Obesity

We previously showed that ME improves fetal brown fat and muscle development, leading to metabolism enhancement in offspring (16, 17). However, the role of ME in other fetal tissues remains to be examined. We assessed the effects of obesity and exercise during pregnancy on epithelial development of fetal intestine at E18.5 (Fig. 1, A and B). H&E staining showed that the fetal intestine from the mothers with obesity (M-OB) underwent progressive villus and crypt shortening, whereas ME protected its length shortening in both female and male M-OB/Ex fetuses (Fig. 1, C and D). Consistently, MO reduced the number of MUC2 positive cells, which was elevated by ME in both female and male M-OB/Ex fetal intestine (Fig. 2, A and B). Consistently, the expression of intestinal epithelial biomarkers, including Lyz1, Muc2, and Tff3, was lower in the M-OB compared with M-Ctrl, but increased in M-OB/Ex, showing the beneficial effects of ME (Fig. 2C). Consistent with morphometrical and mRNA analyses, MO downregulated the protein levels of MUC2 and E-Cadherin in the female and male fetal intestines. However, their levels were increased in response to exercise during pregnancy (Fig. 2, D and E). Thus, fetal epithelial development is impaired due to MO, which is alleviated by ME.

Figure 2.

Maternal exercise enhances epithelial development in fetal intestine. A and B: representative images of MUC2 immunohistochemical staining (A) and the number of MUC2+ cells per villus (B) in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). Scale bar = 100 μm. C: relative gene expression of Lyz1, Muc2, and Tff3 in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). D and E: cropped Western blots of MUC2 (D) and E-Cadherin (E) in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in M-OB vs. M-OB/Ex and $$P < 0.01 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB/Ex by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (B–E). M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice.

Exercise in Pregnancy Enhances Oxidative Metabolism in Fetal Small Intestine

To test whether changes in energetic metabolism accompanies fetal intestinal epithelial development, we assessed the mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in fetal intestine in response to MO and ME. Consistently, mitochondrial DNA copy number and the expression of biogenic genes were decreased in M-OB compared with M-Ctrl. By contrast, exercise (M-OB/Ex) increased mitochondrial biogenesis compared with M-OB (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, although the protein levels of mitochondrial biogenic markers were dramatically decreased in the fetal intestine of MO, exercise protected these adverse changes due to MO (Fig. 3C). PRDM16 improves intestinal epithelial differentiation and function via enhancing oxidative metabolism, especially in duodenum (35). To test, we further analyzed and found near absence of PRDM16 in MO fetal small intestine, but dramatically increased in M-OB/Ex group (Fig. 3D). We next examined the mitochondrial metabolic markers, showing their downregulation in M-OB but upregulation in M-OB/Ex (Fig. 3E). Together, these data demonstrate that exercise in pregnancy stimulates intestinal mitochondrial biogenesis in the fetus of MO and protects against fetal intestinal deterioration due to MO. In addition, the enhanced oxidative metabolism in ME fetal intestine is positively correlated to the expression of PRDM16, improving intestinal oxidative metabolism.

Figure 3.

Maternal exercise enhances oxidative metabolism in fetal small intestine. A: mitochondrial DNA copy number in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). B: mitochondrial biogenesis-related gene expression in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). C and D: cropped Western blots of PGC-1α, VDAC, COX4 (C), and PRDM16 (D) in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). E: gene expression related to mitochondrial input (Cpt1a and Cpt2) and oxidative metabolism (Acadm) in female and male fetal small intestine of M-Ctrl, M-OB, and M-OB/Ex (n = 6). Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in M-OB vs. M-OB/Ex; and $$P < 0.01 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB/Ex by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A–E). M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice.

Beneficial Effects of ME on Epithelial Development Are Partially Mediated by Apelin Activation

Interestingly, we found that ME stimulates apelin expression in fetal intestine of MO, alleviating developmental deterioration of MO fetal intestine (Fig. 4A). To examine the mediatory roles of apelin, we injected apelin or PBS daily to maternal mice during pregnancy (Fig. 4B). Consistently, MO downregulated the expression of epithelial development-related genes, which was elevated by apelin injection (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, protein markers of epithelial development were also lower in OB/PBS compared with CD/PBS whereas their protein levels were highly expressed in OB/APN (Fig. 4D). Together, these data show that apelin administration has a critical role in enhancing MO fetal intestinal development due to ME.

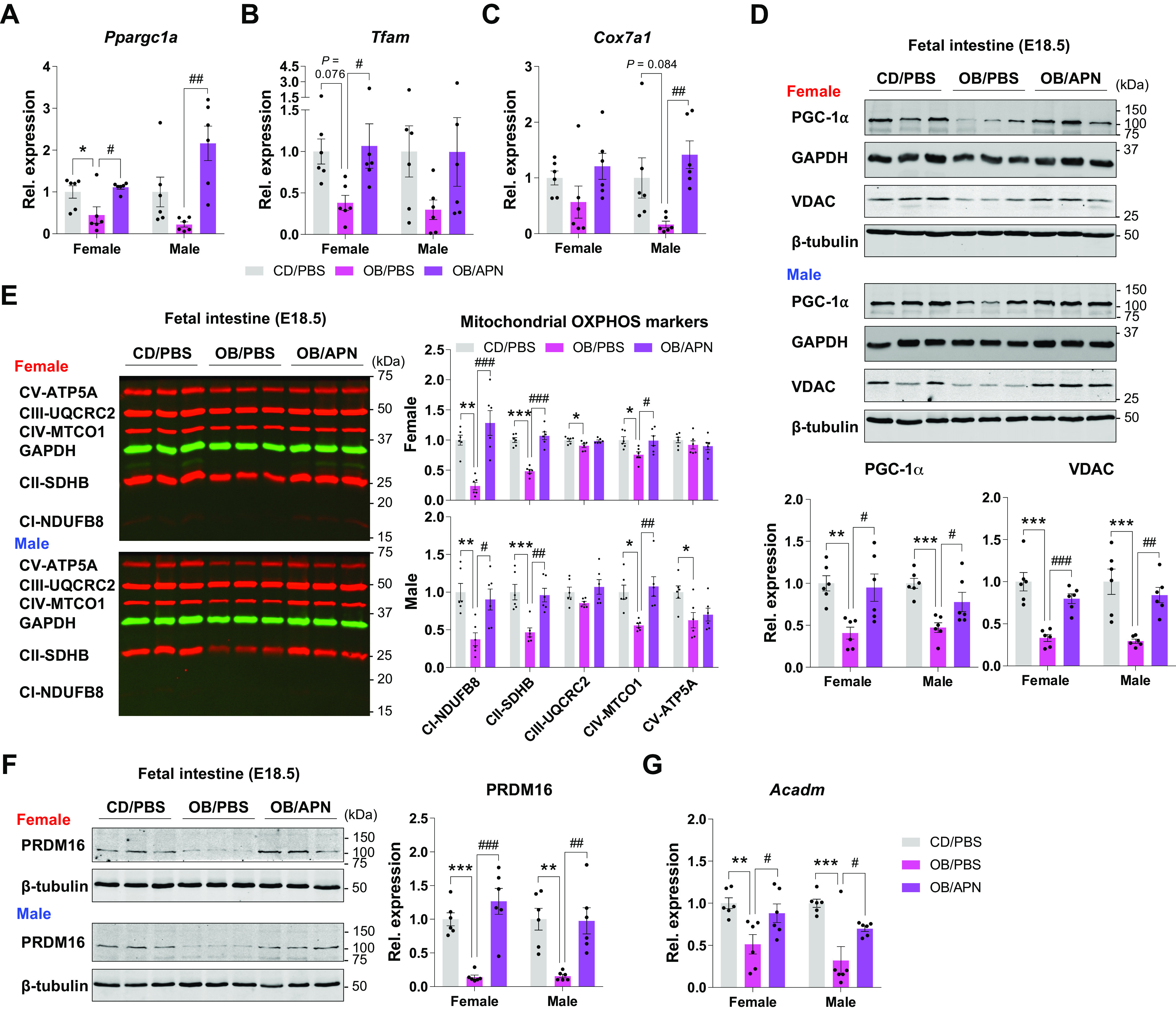

Apelin Administration Partially Mirrors the Benefits of ME on Mitochondrial Metabolism

Given that ME induces epithelial cell development and mitochondrial biogenesis in fetal intestine and apelin administration can mimic these effects of ME (Figs. 1–4), we further analyzed the mediatory role of apelin on energy metabolism. Ppargc1a, Tfam, and Cox7a1 mRNA expression were consistently downregulated in OB/PBS compared with CD/PBS, and their expression was upregulated in OB/APN (Fig. 5, A–C). We further measured the protein levels of mitochondrial biogenic markers, which was decreased in OB/PBS, but increased in OB/APN (Fig. 5D). Consistent changes were also observed in the expression of oxidative markers of mitochondria (Fig. 5, E–G). In short, apelin administration mirrors the beneficial effects of ME on mitochondrial metabolism in the fetal intestine.

Figure 5.

Apelin administration enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in fetal small intestine. A–C: expression of mitochondrial biogenic genes (Ppargc1a, Tfam, and Cox7a1) in female and male fetal small intestine of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN (n = 6). D–F: cropped Western blots of PGC-1α and VDAC (D), OXPHOS (E), and PRDM16 (F) in female and male fetal small intestine of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN (n = 6). G: gene expression of Acadm in female and male fetal small intestine of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN (n = 6). Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in OB/PBS vs. OB/APN by one-way ANOVA followed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A–F). CD, control diet; CD/PBS, control diet with PBS; M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice; OB/APN, obesity with [Pyr1]apelin-13; OB/PBS, obesity with PBS.

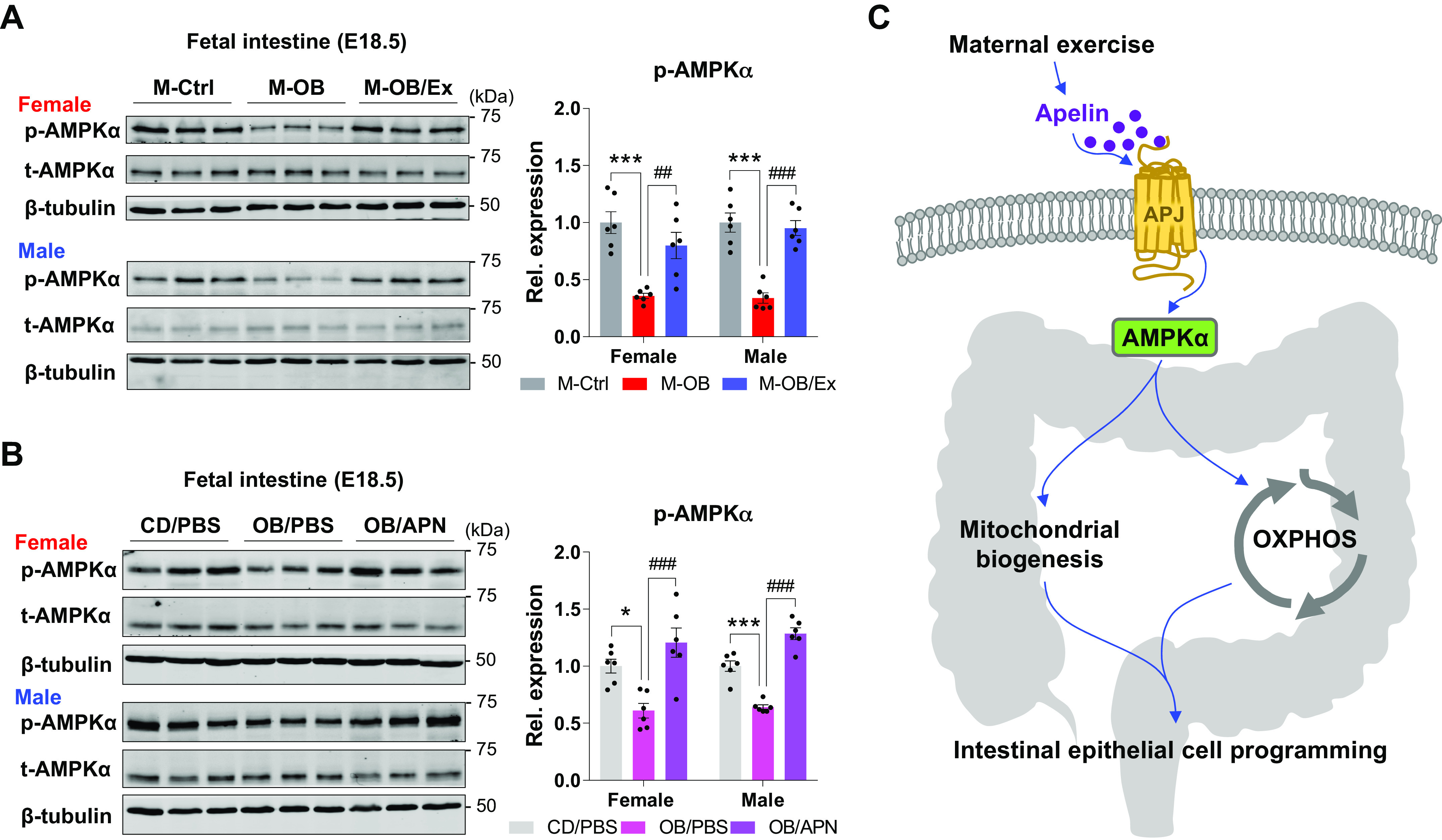

Maternal Exercise-Induced Apelin Activates AMPK and Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Previously, we reported that AMPK activity is required for epithelial cell proliferation (36). In addition, AMPK induces Ppargc1a expression, which promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism (37). Therefore, we further analyzed AMPK activity in fetal tissues from the ME study and the apelin supplementation study. As we expected, ME (M-OB/Ex) and apelin injection (OB/APN) alleviated the downregulation of AMPK phosphorylation due to MO (Fig. 6, A and B). Taken together, ME induces apelin expression and facilitates AMPK activation, leading to mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidation metabolism during fetal intestinal development. Consistent with ME, apelin partially mirrors the beneficial effects of ME in the development of fetal intestinal epithelium (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Maternal exercise and apelin administration activate AMPK in fetal small intestine. A and B: cropped Western blots of AMPK phosphorylation in fetal small intestine of the maternal exercise study (A) and apelin supplementation study (B; n = 6). C: a potential mechanism explaining the improvement in fetal intestinal development due to ME, involving apelin signaling, AMPK activation and mitochondrial biogenesis. Data are represented as means ± SE, and each dot represents one pregnancy. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 in M-Ctrl vs. M-OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS and ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 in M-OB vs. M-OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN by one-way ANOVA followed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A and B). CD, control diet; CD/PBS, control diet with PBS; M-OB, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity without exercise; M-OB/Ex, fetuses from maternal mice with obesity with exercise; M-Ctrl, fetuses from maternal control mice; OB/APN, obesity with [Pyr1]apelin-13; OB/PBS, obesity with PBS.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have demonstrated that MO impairs the epithelial development of fetal small intestine, which is improved due to exercise training during pregnancy. We showed that exercise protects the impairment of villus/crypt morphometrical parameters due to MO, consistent with changes in developmental markers of the intestinal epithelium, including Lyz1 (a marker of Paneth cell), Muc2 (a marker of Goblet cell), and Tff3 (a marker of columnar epithelium). Intestinal stem cells proliferate and differentiate to form the gut epithelial layer, which is closely associated with the cellular metabolic transition and mitochondrial biogenesis (38). Importantly, we discovered that ME-dependent hormone, apelin, partially mimics mitochondrial biogenesis and epithelial development in fetal small intestine. Moreover, we found that intestinal AMPK is deactivated by MO but activated by exercise, establishing AMPK as a downstream target of the ME-apelin axis in improving epithelial development of fetal intestine.

HFD-induced obesity is closely associated with metabolic diseases and intestinal epithelial dysfunctions (39). Consistently, obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases are associated with hyperglycemia (40), which drives intestinal barrier dysfunction (41). Furthermore, obesity negatively regulates the intestinal immunity (42), which is closely associated with intestinal barrier function and epithelial layer homeostasis (43–45), and also affects host-microbial interactions (46). In addition to the direct effect of obesity on intestinal metabolism and development, intergenerational effects of obesity during pregnancy similarly deteriorate gut inflammation and epithelial barrier function of nonobese diabetic offspring mice (47). Nevertheless, the adverse effect of MO on the development of fetal epithelium remains poorly characterized.

Mitochondrial activity regulates epithelial development in the intestine (48), and mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolic transition are required for intestinal stem cell differentiation (49). In particular, PGC-1α is a key transcription coactivator driving mitochondrial biogenesis, which mediates intestinal epithelial cell respiration and oxidative metabolism (19), and its expression is tightly regulated along the crypt-villus axis (50). Consistently, mature intestinal epithelial cells have high levels of mitochondrial contents and activity (50, 51). Similarly, PRDM16, initially identified to be critical for adipose tissue thermogenesis (52), stimulates oxidative metabolism of the intestinal epithelium (35). Furthermore, AMPK, a master regulator of energy metabolism, stimulates PGC-1α, which is required for enhancing gut epithelial differentiation and barrier function (15). Importantly, AMPK is a therapeutic target for intestinal dysfunction (53) and its activation improves metabolic homeostasis in the intestine (54).

In addition, hypoxia-induced apelin activation enhanced intestinal epithelial cell proliferation (55). Consistently, we recently reported that ME induces hypoxic response (56), which may be a possible explanation for the elevated apelin expression in MO fetal small intestine due to ME. Furthermore, we conducted daily injection of apelin to maternal mice during pregnancy. Indeed, apelin injection stimulated mitochondrial biogenesis and improved the fetal intestinal development, similar to ME. To conclusively establish the mediatory roles of apelin signaling, apelin receptor knockout will be needed, which will be addressed in future studies.

Perspectives and Significance

In summary, we found that MO impairs fetal intestinal development and mitochondrial biogenesis, and the adverse effects of MO are recovered by ME. Administration of apelin, a metabolic mediator, partially mirrors the beneficial effects of ME on fetal epithelial development and mitochondrial biogenesis/oxidative metabolism. Furthermore, our data suggest that AMPK and PGC-1α mediate the effects of ME and apelin signaling in improving fetal intestinal development.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HD067449 (to M.D.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.A.C., J.S.S., M.D., and M.-J.Z. conceived and designed research; S.A.C. performed experiments; S.A.C., J.S.S., and M.-J.Z. analyzed data; S.A.C., J.S.S., J.M.d.A., M.D., and M.-J.Z. interpreted results of experiments; S.A.C. prepared figures; S.A.C. drafted manuscript; S.A.C., J.S.S., M.D., and M.-J.Z. edited and revised manuscript; S.A.C., J.S.S., J.M.d.A., M.D., and M.-J.Z. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen YT, Zhang T, Chen C, Xia YY, Han TL, Chen XY, He XL, Xu G, Zou Z, Qi HB, Zhang H, Albert BB, Colombo J, Baker PN. Associations of early pregnancy BMI with adverse pregnancy outcomes and infant neurocognitive development. Sci Rep 11: 3793, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83430-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kusuyama J, Alves-Wagner AB, Makarewicz NS, Goodyear LJ. Effects of maternal and paternal exercise on offspring metabolism. Nat Metab 2: 858–872, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00274-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang QY, Liang JF, Rogers CJ, Zhao JX, Zhu MJ, Du M. Maternal obesity induces epigenetic modifications to facilitate Zfp423 expression and enhance adipogenic differentiation in fetal mice. Diabetes 62: 3727–3735, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db13-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen YT, Hu Y, Yang QY, Son JS, Liu XD, de Avila JM, Zhu MJ, Du M. Excessive glucocorticoids during pregnancy impair fetal brown fat development and predispose offspring to metabolic dysfunctions. Diabetes 69: 1662–1674, 2020. doi: 10.2337/db20-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qiao L, Wattez JS, Lim L, Rozance PJ, Hay WW Jr, Shao J. Prolonged prepregnant maternal high-fat feeding reduces fetal and neonatal blood glucose concentrations by enhancing fetal β-cell development in C57BL/6 mice. Diabetes 68: 1604–1613, 2019. doi: 10.2337/db18-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stanford KI, Takahashi H, So K, Alves-Wagner AB, Prince NB, Lehnig AC, Getchell KM, Lee MY, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Maternal exercise improves glucose tolerance in female offspring. Diabetes 66: 2124–2136, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db17-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anwer H, Morris MJ, Noble DWA, Nakagawa S, Lagisz M. Transgenerational effects of obesogenic diets in rodents: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 23: e13342, 2022. doi: 10.1111/obr.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang CH, Liu XY, Zhan YW, Zhang L, Huang YJ, Zhou H. Effects of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy outcomes. Asia Pac J Public Health 27: 620–630, 2015. doi: 10.1177/1010539515589810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou L, Xiao X. The role of gut microbiota in the effects of maternal obesity during pregnancy on offspring metabolism. Biosci Rep 38: BSR20171234, 2018. doi: 10.1042/BSR20171234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuhle S, Muir A, Woolcott CG, Brown MM, McDonald SD, Abdolell M, Dodds L. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and health care utilization and costs in the offspring. Int J Obes (Lond) 43: 735–743, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drozdowski LA, Clandinin T, Thomson AB. Ontogeny, growth and development of the small intestine: Understanding pediatric gastroenterology. World J Gastroenterol 16: 787–799, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rath E, Moschetta A, Haller D. Mitochondrial function - gatekeeper of intestinal epithelial cell homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 497–516, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aliluev A, Tritschler S, Sterr M, Oppenländer L, Hinterdobler J, Greisle T, Irmler M, Beckers J, Sun N, Walch A, Stemmer K, Kindt A, Krumsiek J, Tschöp MH, Luecken MD, Theis FJ, Lickert H, Böttcher A. Diet-induced alteration of intestinal stem cell function underlies obesity and prediabetes in mice. Nat Metab 3: 1202–1216, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00458-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yan X, Huang Y, Wang H, Du M, Hess BW, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Zhu M-J. Maternal obesity induces sustained inflammation in both fetal and offspring large intestine of sheep. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 1513–1522, 2011. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun X, Yang Q, Rogers CJ, Du M, Zhu MJ. AMPK improves gut epithelial differentiation and barrier function via regulating Cdx2 expression. Cell Death Differ 24: 819–831, 2017. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Son JS, Zhao L, Chen Y, Chen K, Chae SA, de Avila JM, Wang H, Zhu MJ, Jiang Z, Du M. Maternal exercise via exerkine apelin enhances brown adipogenesis and prevents metabolic dysfunction in offspring mice. Sci Adv 6: eaaz0359, 2020. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Son JS, Chae SA, Wang H, Chen Y, Bravo Iniguez A, de Avila JM, Jiang Z, Zhu MJ, Du M. Maternal inactivity programs skeletal muscle dysfunction in offspring mice by attenuating apelin signaling and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Rep 33: 108461, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jäger S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12017–12022, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. D'Errico I, Salvatore L, Murzilli S, Lo Sasso G, Latorre D, Martelli N, Egorova AV, Polishuck R, Madeyski-Bengtson K, Lelliott C, Vidal-Puig AJ, Seibel P, Villani G, Moschetta A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1alpha) is a metabolic regulator of intestinal epithelial cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 6603–6608, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016354108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98: 115–124, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dray C, Knauf C, Daviaud D, Waget A, Boucher J, Buleon M, Cani PD, Attane C, Guigne C, Carpene C, Burcelin R, Castan-Laurell I, Valet P. Apelin stimulates glucose utilization in normal and obese insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab 8: 437–445, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castan-Laurell I, Dray C, Attane C, Duparc T, Knauf C, Valet P. Apelin, diabetes, and obesity. Endocrine 40: 1–9, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yue P, Jin H, Xu S, Aillaud M, Deng AC, Azuma J, Kundu RK, Reaven GM, Quertermous T, Tsao PS. Apelin decreases lipolysis via G(q), G(i), and AMPK-dependent mechanisms. Endocrinology 152: 59–68, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang G, Anini Y, Wei W, Qi X, OCarroll A-M, Mochizuki T, Wang H-Q, Hellmich MR, Englander EW, Greeley GH Jr.. Apelin, a new enteric peptide: localization in the gastrointestinal tract, ontogeny, and stimulation of gastric cell proliferation and of cholecystokinin secretion. Endocrinology 145: 1342–1348, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dray C, Sakar Y, Vinel C, Daviaud D, Masri B, Garrigues L, Wanecq E, Galvani S, Negre-Salvayre A, Barak LS, Monsarrat B, Burlet-Schiltz O, Valet P, Castan-Laurell I, Ducroc R. The intestinal glucose-apelin cycle controls carbohydrate absorption in mice. Gastroenterology 144: 771–780, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vazquez-Martin A, Corominas-Faja B, Cufi S, Vellon L, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez OJ, Joven J, Lupu R, Menendez JA. The mitochondrial H(+)-ATP synthase and the lipogenic switch: new core components of metabolic reprogramming in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Cell Cycle 12: 207–218, 2013. doi: 10.4161/cc.23352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dzeja PP, Chung S, Faustino RS, Behfar A, Terzic A. Developmental enhancement of adenylate kinase-AMPK metabolic signaling axis supports stem cell cardiac differentiation. PLoS One 6: e19300, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanpain C, Horsley V, Fuchs E. Epithelial stem cells: turning over new leaves. Cell 128: 445–458, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20: 256–260, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tunster SJ. Genetic sex determination of mice by simplex PCR. Biol Sex Differ 8: 31, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13293-017-0154-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chae SA, Son JS, Zhu M-J, de Avila JM, Du M. Treadmill running of mouse as a model for studying influence of maternal exercise on offspring. Bio Protoc 10: e3838–e3838, 2020. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang Q, Liang X, Sun X, Zhang L, Fu X, Rogers CJ, Berim A, Zhang S, Wang S, Wang B, Foretz M, Viollet B, Gang DR, Rodgers BD, Zhu MJ, Du M. AMPK/alpha-ketoglutarate axis dynamically mediates DNA demethylation in the prdm16 promoter and brown adipogenesis. Cell Metab 24: 542–554, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Ørntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res 64: 5245–5250, 2004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chae SA, Son JS, Zhao L, Gao Y, Liu X, Marie de Avila J, Zhu MJ, Du M. Exerkine apelin reverses obesity-associated placental dysfunction by accelerating mitochondrial biogenesis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 322: E467–E479, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00023.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stine RR, Sakers AP, TeSlaa T, Kissig M, Stine ZE, Kwon CW, Cheng L, Lim HW, Kaestner KH, Rabinowitz JD, Seale P. PRDM16 maintains homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium by controlling region-specific metabolism. Cell Stem Cell 25: 830–845.e8, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu MJ, Sun X, Du M. AMPK in regulation of apical junctions and barrier function of intestinal epithelium. Tissue Barriers 6: 1–13, 2018. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2018.1487249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 121–135, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Urbauer E, Rath E, Haller D. Mitochondrial Metabolism in the Intestinal Stem Cell Niche-Sensing and Signaling in Health and Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 8: 602814, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.602814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xie Y, Ding F, Di W, Lv Y, Xia F, Sheng Y, Yu J, Ding G. Impact of a high-fat diet on intestinal stem cells and epithelial barrier function in middle-aged female mice. Mol Med Rep 21: 1133–1144, 2020. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.10932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martyn JA, Kaneki M, Yasuhara S. Obesity-induced insulin resistance and hyperglycemia: etiologic factors and molecular mechanisms. Anesthesiology 109: 137–148, 2008. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181799d45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thaiss CA, Levy M, Grosheva I, Zheng D, Soffer E, Blacher E, Braverman S, Tengeler AC, Barak O, Elazar M, Ben-Zeev R, Lehavi-Regev D, Katz MN, Pevsner-Fischer M, Gertler A, Halpern Z, Harmelin A, Aamar S, Serradas P, Grosfeld A, Shapiro H, Geiger B, Elinav E. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science 359: 1376–1383, 2018. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li H, Lelliott C, Håkansson P, Ploj K, Tuneld A, Verolin-Johansson M, Benthem L, Carlsson B, Storlien L, Michaëlsson E. Intestinal, adipose, and liver inflammation in diet-induced obese mice. Metabolism 57: 1704–1710, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alizadeh A, Akbari P, Garssen J, Fink-Gremmels J, Braber S. Epithelial integrity, junctional complexes, and biomarkers associated with intestinal functions. Tissue Barriers 10: 1996830, 2022. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2021.1996830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barbara G, Barbaro MR, Fuschi D, Palombo M, Falangone F, Cremon C, Marasco G, Stanghellini V. Inflammatory and microbiota-related regulation of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Front Nutr 8: 790387, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.790387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 141–153, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336: 1268–1273, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xue Y, Wang H, Du M, Zhu MJ. Maternal obesity induces gut inflammation and impairs gut epithelial barrier function in nonobese diabetic mice. J Nutr Biochem 25: 758–764, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berger E, Rath E, Yuan D, Waldschmitt N, Khaloian S, Allgäuer M, Staszewski O, Lobner EM, Schöttl T, Giesbertz P, Coleman OI, Prinz M, Weber A, Gerhard M, Klingenspor M, Janssen KP, Heikenwalder M, Haller D. Mitochondrial function controls intestinal epithelial stemness and proliferation. Nat Commun 7: 13171, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rogers RP, Rogina B. Increased mitochondrial biogenesis preserves intestinal stem cell homeostasis and contributes to longevity in Indy mutant flies. Aging (Albany NY) 6: 335–350, 2014. doi: 10.18632/aging.100658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rodríguez-Colman MJ, Schewe M, Meerlo M, Stigter E, Gerrits J, Pras-Raves M, Sacchetti A, Hornsveld M, Oost KC, Snippert HJ, Verhoeven-Duif N, Fodde R, Burgering BM. Interplay between metabolic identities in the intestinal crypt supports stem cell function. Nature 543: 424–427, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature21673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jeynes BJ, Altmann GG. A region of mitochondrial division in the epithelium of the small intestine of the rat. Anat Rec 182: 289–296, 1975. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091820303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seale P, Conroe HM, Estall J, Kajimura S, Frontini A, Ishibashi J, Cohen P, Cinti S, Spiegelman BM. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 96–105, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI44271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun X, Zhu MJ. AMP-activated protein kinase: a therapeutic target in intestinal diseases. Open Biol 7: 170104, 2017. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Harmel E, Grenier E, Bendjoudi Ouadda A, El Chebly M, Ziv E, Beaulieu JF, Sané A, Spahis S, Laville M, Levy E. AMPK in the small intestine in normal and pathophysiological conditions. Endocrinology 155: 873–888, 2014. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Han S, Wang G, Qi X, Lee HM, Englander EW, Greeley GH. Jr. A possible role for hypoxia-induced apelin expression in enteric cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1832–R1839, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00083.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Son JS, Liu X, Tian Q, Zhao L, Chen Y, Hu Y, Chae SA, de Avila JM, Zhu MJ, Du M. Exercise prevents the adverse effects of maternal obesity on placental vascularization and fetal growth. J Physiol 597: 3333–3347, 2019. doi: 10.1113/JP277698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]