Abstract

Objective

This post-approval safety study assessed the efficacy and safety of exemestane after 2−3 years of tamoxifen treatment among postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) early breast cancer in China.

Methods

Enrolled patients had received 2−3 years of tamoxifen and were then switched to exemestane for completion of 5 consecutive years of adjuvant endocrine therapy. The primary endpoint was the time from enrollment to the first occurrence of locoregional/distant recurrence of the primary breast cancer, appearance of a second primary or contralateral breast cancer, or death due to any cause. Other endpoints included the proportion of patients experiencing each event, incidence rate per annum, relationships between human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status and time to event, and relationship between disease history variables and time to event.

Results

Overall, 558 patients were included in the full analysis set: 397 (71.1%) completed the study, 20 experienced an event, and 141 discontinued [47 owing to an adverse event (AE); 37 no longer willing to participate]. Median duration of treatment was 29.5 (range, 0.1−57.7) months. Median time to event was not reached. Event-free survival probability at 36 months was 91.4% (95% CI, 87.7%−95.1%). The event incidence over the total exposure time of exemestane therapy was 3.5 events/100 person-years (20/565). Multivariate analysis showed an association between tumor, lymph node, and metastasis stage at initial diagnosis and time to event [hazard ratio: 1.532 (95% CI, 1.129−2.080); P=0.006]. Most AEs were grade 1 or 2 in severity, with arthralgia (7.7%) being the most common treatment-related AE.

Conclusions

This study supports the efficacy and safety of exemestane in postmenopausal Chinese women with ER+ breast cancer previously treated with adjuvant tamoxifen for 2−3 years. No new safety signals were identified in the Chinese population.

Keywords: Chinese, early breast cancer, exemestane, tamoxifen, postmenopausal women, estrogen receptor-positive

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women in many countries, including China (1,2). National Comprehensive Cancer Network® guidelines recommend that postmenopausal women with early estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer receive an aromatase inhibitor or tamoxifen as treatment (3). However, aromatase inhibitors, when compared with tamoxifen, have been shown to reduce breast cancer recurrence rates by about one third and reduce 10-year breast cancer mortality rates by approximately 15% in postmenopausal women with ER+ early breast cancer (4).

Exemestane is an irreversible, steroidal aromatase inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with ER+ early breast cancer who have received 2−3 years of tamoxifen and are switched to exemestane for completion of a total of 5 consecutive years of adjuvant endocrine therapy, as well as for the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women whose disease has progressed following tamoxifen therapy. In 2008, exemestane was also approved in China as adjuvant treatment in postmenopausal women with ER+ early invasive breast cancer who received 2−3 years of tamoxifen and are to be switched to exemestane. This approval was based on efficacy and safety results of the international, phase 3, randomized, controlled Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES), which demonstrated improved disease-free survival with exemestane after 2−3 years of tamoxifen compared with 5 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer (5,6).

Currently, there is a lack of systematic collection and analysis of efficacy and safety data for exemestane in the adjuvant setting in the Chinese population. This pragmatic clinical trial was designed to assess efficacy and safety of tamoxifen followed by exemestane in the adjuvant setting among postmenopausal Chinese women with ER+ early breast cancer, as a postmarketing commitment study for the China new drug application (NDA) approval.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a multicenter, single-arm, prospective, and pragmatic clinical study (No. NCT01176916) conducted between February 6, 2011, and November 30, 2018. The study planned to enroll and analyze efficacy and safety data from approximately 550 eligible patients. The study was approved by an independent ethics committee at each study site and conducted in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Eligible patients included postmenopausal women with early invasive ER+ breast cancer confirmed by histology or cytology. These patients had received adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for 2−3 years and 1) had received exemestane treatment for no more than 1 week and were to continue to receive exemestane or 2) were to be switched to receive exemestane treatment (decision to prescribe exemestane necessarily preceded and was independent of the decision regarding the patient’s enrollment). Study exclusion criteria included evidence of a local relapse or distant metastasis of breast cancer or a second primary cancer after adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for 2−3 years and before receiving exemestane treatment, or received other aromatase inhibitors (not exemestane) following the adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for 2−3 years.

Exemestane was administered orally in accordance with the Chinese exemestane prescribing information. Patients received one 25-mg tablet once daily after a meal in the absence of recurrence or contralateral breast cancer until completion of 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy or until the occurrence of a protocol-defined event. Patients received the study drug as outpatients, with interim clinic visits at 6-month intervals. Endpoint data were collected at each study visit. For each patient, the final visit occurred at completion of the study drug or at the occurrence of any of the events signifying treatment termination. The end of the study was defined as the last visit of the last patient. Investigators reviewed and analyzed all visit data relevant to the primary and secondary endpoints.

Upon request and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Efficacy and safety

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to event, defined as the time from d 1 (enrollment and first dose of study drug) to the earliest occurrence of any of the following: locoregional/distant recurrence of the primary breast cancer (locoregional recurrence was defined as any recurrence in the ipsilateral breast, chest wall, or axillary lymph nodes), appearance of a second primary or contralateral breast cancer, or death from any cause.

Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients experiencing each event and the number of events in relation to the total exemestane exposure (in years). Additional exploratory analyses included relationships between human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status and time to event, and between disease history variables [ie, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS)] at diagnosis; current tumor, lymph node, and metastasis (TNM) stage; hormone receptor status] and time to event.

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded from the time a patient received ≥1 dose of study treatment through the patient’s last visit and were graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Statistical analysis

All summaries of efficacy parameters were reported for the full analysis set (FAS), defined as all patients who received ≥1 dose of exemestane during the observation period. Baseline characteristics (eg, demographics, breast cancer history, primary diagnosis, laboratory data, location of primary diagnosis, histopathological classification and grade, and TNM stage) and safety parameters were reported in the safety analysis set, defined as all enrolled patients who received ≥1 dose of exemestane. Patients who completed the study were those who received 2−3 years of tamoxifen and switched to exemestane to complete a total of 5 consecutive years of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Patients discontinued if they experienced an event, were lost to follow-up, were no longer willing to participate in the study, had objective progression or relapse, had a protocol violation, had an AE related or not related to study drug, or death. Patients lost to follow-up and those who were still being followed up at the time of analysis with no documented event were censored at the last date the patient was known to be event-free. The Kaplan-Meier non-parametric estimate was used to summarize the survival distribution and median time to event. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the median time to event (Brookmeyer-Crowley method) (7) and 95% confidence bands for the survival distribution (Hall-Wellner method) (8) were computed. The relationship between HER2 status level (binary) (9) and time to event was assessed by fitting a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Another Cox proportional hazards regression model for time to event analyses including terms for HER2 status and disease history variables was fitted to determine the influence of these factors on the time to event, with the hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding two-sided 95% CI estimated. A Cox proportional hazards regression model for time to recurrence included terms for HER2 status and disease history variables [ECOG PS at diagnosis, current TNM stage, and hormone receptor status: ER/progesterone receptor (PR) status]. The method for selecting factors for the Cox regression model was based on significant results of a univariate analysis or clinical judgement. A stepwise selection method for the final independent variables was used. HER2 status and hormone receptor (ER/PR) status were removed (P>0.15) and ECOG PS and TNM stage at initial diagnosis remained in the final model by the stepwise selection method. A post hoc time to event analysis was performed in patients who were treated with tamoxifen for ≤2.5 years and in those treated with tamoxifen for >2.5 years. Moreover, a sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded patients with ER-negative disease to investigate whether the inclusion of these patients affected the outcome of the time to event analysis among all patients in the FAS.

Results

Patients

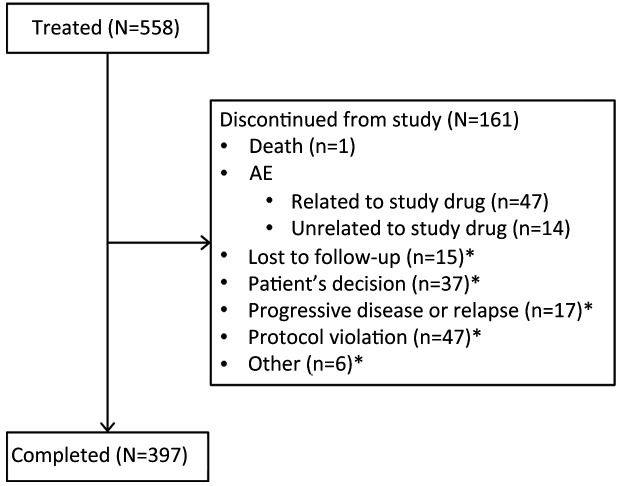

In total, 558 patients received exemestane treatment (FAS; Figure 1). Overall, 397 (71.1%) patients received 2−3 years of tamoxifen and switched to exemestane to complete a total of 5 consecutive years of adjuvant endocrine therapy, and 161 (28.9%) patients discontinued from the study (inclusive of patients with an event). Among patients who discontinued, 47 discontinued owing to an AE related to the study drug and 37 were no longer willing to participate in the study (Figure 1). Mean (range) age was 51 (36−88) years, and most patients (84.6%) were aged 45−59 years (Table 1). Mean weight and body mass index were 60.6 (42.0−90.0) kg and 23.7 (16.9−34.7) kg/m2, respectively. All patients had a primary diagnosis of breast cancer, with mean disease duration of 2.9 (1.9−5.3) years. In the FAS, median duration of treatment (tamoxifen plus exemestane) was 29.5 (0.1−57.7) months, with 453 patients receiving exemestane after tamoxifen for ≥12 months.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event. *, Relationship to study drug unknown.

Table 1. Patients’ demographics and baseline clinical characteristics (N=558).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; *, Weight was not available for 93 patients; therefore, weight and BMI were calculated for 465 patients; †, Mean height was calculated for 544 patients; #, Other included patients whose tumor and lymph node stage were not collected and metastasis stage was confirmed as 0. | |

| Age (year) | |

|

51±6 |

| Range | 36−88 |

| Age group (year) | |

| 36−44 | 38 (6.8) |

| 45−59 | 472 (84.6) |

| ≥60 | 48 (8.6) |

| Weight (kg)* | |

|

60.6±8.4 |

| Range | 42.0−90.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | |

|

23.7±3.0 |

| Range | 16.9−34.7 |

| Height (cm)† | |

|

159.7±4.8 |

| Range | 144.0−178.0 |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 339 (60.8) |

| 1 | 131 (23.5) |

| 2 | 3 (0.5) |

| Not reported | 85 (15.2) |

| TNM stage at initial diagnosis | |

| I | 181 (32.4) |

| IIA | 164 (29.4) |

| IIB | 91 (16.3) |

| IIIA | 63 (11.3) |

| IIIB | 8 (1.4) |

| IIIC | 25 (4.5) |

| Unknown | 7 (1.3) |

| Other# | 19 (3.4) |

| Histologic type | |

| Ductal carcinoma | 503 (90.1) |

| Lobular carcinoma | 18 (3.2) |

| Papillary carcinoma | 4 (0.7) |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 10 (1.8) |

| Other | 23 (4.1) |

| ER status | |

| Positive | 549 (98.4) |

| Negative | 9 (1.6) |

| PR status | |

| Positive | 453 (81.2) |

| Negative | 74 (13.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Not performed | 30 (5.4) |

| HER2 immunohistochemistry status | |

| 0 | 154 (27.6) |

| 1+ | 140 (25.1) |

| 2+ | 123 (22.0) |

| 3+ | 73 (13.1) |

| Unknown | 10 (1.8) |

| Not performed | 58 (10.4) |

Time to event (primary endpoint)

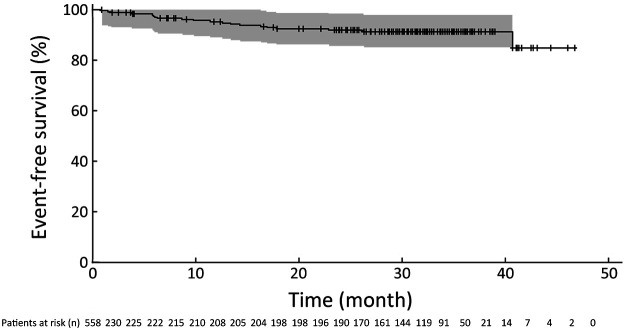

In the FAS, among the 161 patients who discontinued from the study, 20 patients (3.6%) experienced an event (17 locoregional/distant recurrence of the primary breast cancer events, 1 second primary breast cancer event, 2 death events) (Table 2). Median time to event was not reached because only a small number of patients (20/558) had experienced an event by the end of the study (Table 2). In the FAS, event-free survival probability at 36 months was 91.4% (95% CI, 87.7%−95.1%) (Figure 2). In a sensitivity analysis in which 9 patients with ER-negative disease were removed from the FAS, the event-free survival probability at month 36 was 91.7% (95% CI, 88.0%−95.4%) (Table 3). Thus, these results are consistent with the results in the FAS and do not affect the main conclusion of the study.

Table 2. Type of event experienced by patients (N=558).

| Events | n (%) |

| *, One patient experienced locoregional/distant recurrence of primary breast cancer, appearance of second primary or contralateral breast cancer, and died from disease under study. Another patient experienced locoregional/distant recurrence of the primary breast cancer and died. Thus, these two patients were counted only for the event that occurred earliest for time to event evaluation. | |

| Patients with event, by type of event | 20 (3.6) |

| Locoregional/distant recurrence of primary breast cancer |

17 (3.0) |

| Appearance of second primary breast cancer | 1 (0.2)* |

| Death due to any cause | 2 (0.4)* |

| Patients censored | 538 (96.4) |

| Patients remained in follow-up | 0 (0) |

| Patients completed study | 397 (71.1) |

| Patients discontinued from study | 141 (25.3) |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to event. Shaded area represents 95% confidence band calculated from the Hall-Wellner method.

Table 3. Post hoc analyses of type of event.

| Events | n (%) | ||

| Subset excluding patients with ER-negative disease at baseline (N=549) |

Patients treated with tamoxifen ≤2.5 years (N=282) |

Patients treated with tamoxifen >2.5 years (N=276) |

|

| ER, estrogen receptor. | |||

| Patients with event, by type of event | 19 (3.5) | 19 (6.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Locoregional/distant recurrence of primary breast cancer |

16 (2.9) | 16 (5.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Appearance of second primary breast cancer | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Death due to any cause | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Patients censored | 530 (96.5) | 263 (93.3) | 275 (99.6) |

| Patients remained in follow-up | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patients completed study | 393 (71.6) | 132 (46.8) | 265 (96.0) |

| Patients discontinued from study | 137 (25.0) | 131 (46.5) | 10 (3.6) |

Among patients treated with tamoxifen for ≤2.5 years (n=282), 19 events occurred and event-free survival probability at month 36 was 75.2% (95% CI, 65.0%−85.3%) (Table 3). Among patients treated with tamoxifen for >2.5 years (n=276), only 1 event occurred (locoregional/distant recurrence of the primary breast cancer) and event-free survival probability at month 36 was 100%. Because of the small number of events, no other conclusions can be drawn.

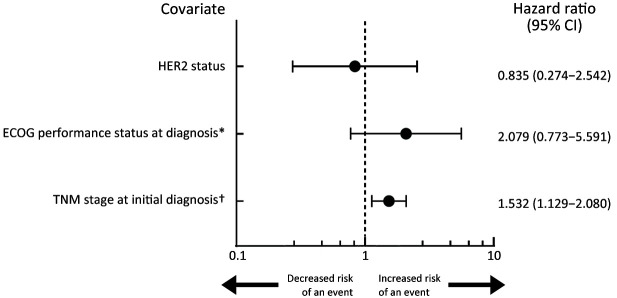

Secondary endpoints

The event incidence was 3.5 events/100 person-years (20/565). The HR for the time to event analysis according to HER2 status (HER2-positive vs. HER2-negative) was 0.854 (95% CI, 0.281−2.597), with a P value of 0.781. For TNM stage at initial diagnosis, the HR was 1.593 (95% CI, 1.16−2.19) with a significant P value of 0.004.

The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis did not reveal an association between HER2 status (binary) and time to event [HR, 0.835 (95% CI, 0.274−2.542); P=0.751] (Figure 3). Multivariate analysis according to all patients’ demographics and baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1) showed an association between TNM stage at initial diagnosis and time to event [HR, 1.532 (95% CI, 1.129−2.080); P=0.006], in which patients with a later TNM stage may have an increased risk of experiencing an event.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of Cox proportional hazard’s regression model. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; *, ECOG performance status at diagnosis level included 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4. †, TNM stage at initial diagnosis included 1 (Stage I), 2 (Stage IIA), 3 (Stage IIB), 4 (Stage IIIA), 5 (Stage IIIB), and 6 (Stage IIIC).

Safety

In total, 345 of 558 (61.8%) patients experienced all-causality AEs, and 222 (39.8%) reported treatment-related AEs (Table 4). The majority of AEs were grade 1 or 2 in severity. A total of 38 (6.8%) patients experienced all-causality serious AEs (SAEs), and 3 (0.5%) patients reported treatment-related SAEs, including unstable angina, ankle fracture, and cerebral infarction. None of the grade 5 AEs were considered treatment-related AEs. Discontinuation due to all-causality AEs occurred in 11.1% of patients and discontinuation due to treatment-related AEs occurred in 8.4% of patients. No patient had a dose reduction owing to an AE. Incidences of AEs are listed in Table 5. The most frequently reported treatment-related AE was arthralgia in 43 patients (7.7%), which was the only treatment-related AE reported by >5% of patients. All treatment-related AEs of arthralgia were grade 1−2 in severity except for 1 patient who experienced grade 3 arthralgia. Eight patients permanently discontinued and 2 patients temporarily discontinued from the study owing to treatment-related arthralgia. A total of 4 deaths were reported by the end of the study. No deaths were considered directly related to exemestane. Overall, 62 (11.1%) patients permanently discontinued from the study because of AEs, of whom 47 (8.4%) discontinued owing to treatment-related AEs.

Table 4. Summary of patients with all-causality and treatment-related AEs (N=558).

| AEs | n (%) | |

| All- causality |

Treatment- related |

|

| AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event. Patients were counted only once in each row. | ||

| AEs | 345 (61.8) | 222 (39.8) |

| SAEs | 38 (6.8) | 3 (0.5) |

| Grade 3 or 4 AEs | 30 (5.4) | 11 (2.0) |

| Grade 5 AEs | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Discontinued owing to AEs | 62 (11.1) | 47 (8.4) |

| Reduced dose owing to AEs | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Temporarily discontinued owing to AEs | 28 (5.0) | 14 (2.5) |

Table 5. AE incidence (N=558).

| AEs | n (%) |

| AE, adverse event; *, Including one patient with an AE of missing or unknown severity. | |

| All-causality AEs in ≥2% of patients | |

| Arthralgia | 50 (9.0) |

| Vaginal hemorrhage | 33 (5.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 22 (3.9) |

| Osteoporosis | 19 (3.4) |

| Hepatic steatosis | 15 (2.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 15 (2.7) |

| Hypertension | 14 (2.5) |

| Hepatic cyst | 14 (2.5) |

| Osteopenia | 13 (2.3) |

| Uterine leiomyoma | 13 (2.3)* |

| Lymphadenopathy | 12 (2.2)* |

| Treatment-related AEs in ≥1% of patients | |

| Arthralgia | 43 (7.7) |

| Vaginal hemorrhage | 25 (4.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 18 (3.2) |

| Osteoporosis | 15 (2.7) |

| Insomnia | 10 (1.8) |

| Osteopenia | 10 (1.8) |

| Bone pain | 7 (1.3) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase increased | 7 (1.3) |

| Hepatic steatosis | 7 (1.3) |

| Uterine leiomyoma | 7 (1.3)* |

| Alopecia | 6 (1.1) |

A total of 415 patients with ≥1 laboratory test measurement while on study treatment or during lag time were evaluable for laboratory data, and 180/415 (43.4%) patients had laboratory test abnormalities (Supplementary Table S1). The most frequently reported laboratory abnormalities (without regard to baseline abnormality) were elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [63 (19.0%)], elevated triglycerides [51 (14.7%)], and elevated uric acid [28 (7.3%)].

Table S1. Laboratory test abnormalities in 180/415 patients, without regard to baseline abnormality.

| Parameters | Patients with evaluable laboratory data | |

| N | n (%) | |

| HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; ULN, upper limit of norma; LLN, lower limit of normal; N=number of participants with ≥1 observation of the given laboratory test while on study treatment or during lag time; n=number of participants with a laboratory abnormality meeting specified criteria while on study treatment or during lag time. | ||

| Hematology | ||

| Platelets (>1.75× ULN) (103/mm3) | 373 | 2 (0.5) |

| White blood cell count (>1.5× ULN) (103/mm3) | 374 | 1 (0.3) |

| Lymphocytes (%) | ||

| <0.8× LLN | 359 | 10 (2.8) |

| >1.2× ULN | 359 | 13 (3.6) |

| Neutrophils (%) | ||

| <0.8× LLN | 359 | 6 (1.7) |

| >1.2× ULN | 359 | 3 (0.8) |

| Basophils (>1.2× ULN) | 355 | 17 (4.8) |

| Eosinophils (>1.2× ULN) | 355 | 8 (2.3) |

| Monocytes (>1.2× ULN) | 354 | 8 (2.3) |

| Liver function | ||

| Total bilirubin (>1.5× ULN) (mg/dL) | 398 | 17 (4.3) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (>3.0× ULN) (IU/L) | 398 | 1 (0.3) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (>3.0× ULN) (IU/L) | 399 | 2 (0.5) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (>3.0× ULN) (IU/L) | 385 | 8 (2.1) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | ||

| <0.8× LLN | 398 | 1 (0.3) |

| >1.2× ULN | 398 | 1 (0.3) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||

| <0.8× LLN | 398 | 1 (0.3) |

| >1.2× ULN | 398 | 4 (1.0) |

| Renal function (mg/dL) | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen (>1.3× ULN) | 379 | 3 (0.8) |

| Creatinine (>1.3× ULN) | 388 | 1 (0.3) |

| Uric acid (>1.2× ULN) | 385 | 28 (7.3) |

| Lipids (mg/dL) | ||

| Cholesterol (>1.3× ULN) | 347 | 14 (4.0) |

| HDL cholesterol (<0.8× LLN) | 332 | 20 (6.0) |

| LDL cholesterol (>1.2× ULN) | 331 | 63 (19.0) |

| Triglycerides (>1.3× ULN) | 346 | 51 (14.7) |

| Clinical chemistry (other) | ||

| Glucose (>1.5× ULN) (mg/dL) | 363 | 17 (4.7) |

Discussion

This was a multicenter, single-arm, prospective clinical trial to assess the efficacy and safety of exemestane in the adjuvant setting in the Chinese population. These efficacy and safety data provided a reference for exemestane use in clinical practice in China. In this study, median time to event was not estimable because only a small number of patients [20 (3.6%)] experienced an event by the end of the study. The event incidence was 3.5 events/100 person-years (20/565), indicating that the less frequently that events occurred, the more patients benefitted from exemestane therapy during the total exposure time. Event-free survival probability at 36 months was 91.4%.

Some of these results were similar to those in the IES, an international, randomized controlled trial of exemestane, which assessed disease-free survival after switching to exemestane after 2−3 years of tamoxifen vs. continuing tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer (5,6). Disease-free survival was 91.5% in the exemestane group 3 years after randomization [HR, 0.68 (95% CI, 0.56–0.82); P<0.001)] (5). Overall, results from the IES demonstrated that switching to an aromatase inhibitor after 2−3 years of tamoxifen compared with continuing tamoxifen can reduce the risk of disease recurrence by 32% and result in an absolute benefit in disease-free survival of 4.7% (5). Moreover, a meta-analysis of the IES, the Italian Tamoxifen Anastrozole trial, Arimidex-Nolvadex 95 trial, and the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group 8 trial (N=9,015 total) concluded that switching to an aromatase inhibitor after 2−3 years of tamoxifen resulted in significantly lower recurrence rates compared with continuing tamoxifen (10). Based on data from these randomized trials and other trials of adjuvant treatment, the American Society of Clinical Oncology updated their practice guidelines to recommend that postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer consider an aromatase inhibitor as either primary adjuvant therapy or sequential adjuvant treatment after 2−3 years of tamoxifen (11). Overall, the data presented in the current, single-arm study add to the body of literature that highlights the benefit of switching to an aromatase inhibitor after 2−3 years of tamoxifen therapy.

In the Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination (ATAC) clinical study, anastrozole taken for 5 years showed superior efficacy to 5 years of tamoxifen, with a 17% relative risk reduction in disease-free survival in the intention-to-treat population (12). The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group MA-17 trial also showed a significant improvement in disease-free survival favoring patients who received adjuvant tamoxifen for 5 years and were then randomized to letrozole vs. placebo (13). Currently, 5 years of an aromatase inhibitor is a treatment option for postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. Whether there is a survival benefit with the use of an aromatase inhibitor after 2−3 years of tamoxifen compared with 5 years with only aromatase inhibitor therapy has been previously assessed in the literature. In the phase 3 FATA-GIM3 trial, the 5-year disease-free survival rate of 3,697 enrolled patients receiving aromatase inhibitor treatment was 88.5%, which was not superior to 2 years of tamoxifen followed by 3 years of aromatase inhibitor (89.8%; P=0.23) (14). These data suggest the results of the current study are meaningful and can guide current treatment strategies.

There are several reasons why physicians consider the benefits of using tamoxifen upfront. One reason is that both the previous studies and the current study enrolled patients with amenorrhea after chemotherapy. The mean age of patients enrolled in the current study is 51 years, which suggests that about 50% of patients were premenopausal when diagnosed with breast cancer. Premenopausal patients initially treated with an aromatase inhibitor had to undergo ovarian function suppression (OFS) [eg, with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists GnRHa)], or ovariectomy. For those unwilling to accept ovariectomy, OFS became a preferred option. However, some data showed incomplete suppression of ovarian function with OFS. Other studies have shown that a small number of patients had ovarian castration escape with GnRHa. In the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial Estrogen Substudy (SOFT-EST), estrogen levels during GnRHa treatment were monitored, and it was found that 17% of patients had ovarian escape within 1 year after medication (estrogen suppression was not complete) (15). Similar results were observed in a retrospective, real-world study by Burns et al. in 2021, with 24% of patients experiencing ovarian escape (16), and a previous retrospective study demonstrated 6.86% of patients with ovarian escape when receiving GnRHa. Age was an independent influencing factor of castration escape, with younger patients more likely to escape from castration [odds ratio (OR): 0.869 (95% CI, 0.756−0.999); P=0.049)] (17). Therefore, patients can be treated with tamoxifen first, while ovarian function gradually declines over time. Switching to an aromatase inhibitor after tamoxifen may result in a positive clinical outcome; thus, 2−3 years of tamoxifen followed by an aromatase inhibitor may be an effective treatment option, especially in Chinese patients who are considered younger at breast cancer diagnosis (median age, 48−50 years) than in other (high-income) countries (eg, US median age, 64.3 years) (18).

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis suggested that patients with a later TNM stage may have an increased risk of experiencing an event. Also, another advantage treating with tamoxifen first is the potential for bone protection (19). Patients who receive aromatase inhibitors have an increased risk of bone loss and arthralgia compared with those treated with tamoxifen (20). The mechanism for the accelerated bone loss may be the suppression of estrogen synthesis (21). Moreover, in the BIG 1-98 trial of letrozole vs. tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer, bone fractures were significantly more frequent with letrozole than with tamoxifen (5.7% vs. 4.0%; P<0.001) (22). As the current study uses upfront tamoxifen for 2−3 years, this treatment regimen may be beneficial to patients by protecting bone density.

In the current study, exemestane was generally tolerable, and associated AEs were manageable in Chinese postmenopausal women with early invasive breast cancer. The safety profile was consistent with the known safety profile of exemestane. The most frequently reported treatment-related AE was arthralgia, which was the only treatment-related AE reported by >5% of patients. Osteoporosis, osteopenia, insomnia, bone pain and alopecia were expected common AEs associated with exemestane, as indicated in the prescribing information. Other common AEs associated with exemestane, such as hot flushes, nausea, fatigue and increased sweating, were rarely reported in this study (<1% of patients). This might be due to the limitation of pragmatic clinical trials; the frequency of study visits was at the discretion of the investigator according to local clinical practice guidelines and/or the investigator’s clinical judgment. Therefore, the frequency of patient visits was lower than in randomized studies. Another possible explanation may be that patients did not inform their doctors of these symptoms (eg, hot flushes and increased sweating) because they may not have significantly affected quality of life. Overall, the incidence of treatment-related AEs was relatively low (with the majority of all-causality and treatment-related AEs reported by <1% of patients), which may be due to intrinsic limitations of the study design.

In recent years, studies have evaluated an extension strategy of up to 10 years for endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive early breast cancer. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that examined the effect of extended use of letrozole for an additional 5 years showed that treatment with letrozole over 10 years resulted in a significantly improved disease-free survival rate and a lower incidence of contralateral breast cancer compared with placebo treatment (23). Albeit, the rate of overall survival did not differ with letrozole compared with placebo. Currently, there are no standard recommendations regarding extended adjuvant endocrine therapy treatment in early breast cancer.

A limitation of this study was that it was designed as a single-arm, open-label study. Additional randomized, controlled studies among the Chinese population with long-term follow-up are warranted to further determine if switching to exemestane is associated with a significant event-free survival benefit over continuing tamoxifen treatment in patients with ER+ early invasive breast cancer.

Conclusions

An event-free survival probability of 91.4% at 36 months was observed after switching to exemestane after 2−3 years of tamoxifen treatment in Chinese postmenopausal women with early invasive ER+ breast cancer in this study. Exemestane was generally tolerable and exemestane-associated AEs were manageable. The safety profile in the Chinese population was consistent with the known safety profile of exemestane.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Pfizer Inc.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun D, Cao M, Li H, et al Cancer burden and trends in China: A review and comparison with Japan and South Korea. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:129–39. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Breast Cancer Version 1. 2019. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_blocks.pdf

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:1341–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombes RC, Kilburn LS, Snowdon CF, et al Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2−3 years’ tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:559–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. doi: 10.2307/2530286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall WJ, Wellner JA Confidence bands for a survival curve from censored data. Biometrika. 1980;67:133–43. doi: 10.1093/biomet/67.1.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recommended by Breast Cancer Expert Panel Guideline for HER2 detection in breast cancer, the 2019 version. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2019;48:169–75. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, et al Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:509–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, et al American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3784–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, et al Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1793–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Placido S, Gallo C, De Laurentiis M, et al Adjuvant anastrozole versus exemestane versus letrozole, upfront or after 2 years of tamoxifen, in endocrine-sensitive breast cancer (FATA-GIM3): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:474–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellet M, Gray KP, Francis PA, et al Twelve-month estrogen levels in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer receiving adjuvant triptorelin plus exemestane or tamoxifen in the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT): The SOFT-EST substudy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1584–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns E, Koca E, Xu J, et al Measuring ovarian escape in premenopausal estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients on ovarian suppression therapy. Oncologist. 2021;26:e936–42. doi: 10.1002/onco.13722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Yan Y, Jiang H, et al Ovarian suppression efficacy of gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists for patients with premenopausal hormone receptor positive breast cancer: A real-world study. Mil Med Sci. 2021;45:373–9. doi: 10.7644/j.issn.1674-9960.2021.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, et al Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e279–89. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love RR, Mazess RB, Barden HS, et al Effects of tamoxifen on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:852–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203263261302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman RE, Banks LM, Girgis SI, et al Skeletal effects of exemestane on bone-mineral density, bone biomarkers, and fracture incidence in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:119–27. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servitja S, Martos T, Rodriguez Sanz M, et al Skeletal adverse effects with aromatase inhibitors in early breast cancer: evidence to date and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:291–6. doi: 10.1177/1758834015598536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 Collaborative Group, Thürlimann B, Keshaviah A, et al A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2747–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, et al. Extending aromatase-inhibitor adjuvant therapy to 10 years. N Engl J Med 2016;375:209-19.