Abstract

Background

The role of pharmacists has expanded beyond dispensing and packaging over the past two decades, and now includes ensuring rational use of drugs, improving clinical outcomes and promoting health status by working with the public and other healthcare professionals.

Objectives

To examine the effect of pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services on patient outcomes, health service utilisation and costs in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Search methods

Studies were identified by electronically searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (February 2010), MEDLINE (1949 to February 2010), Scopus (1960 to March 2010) and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to January 2010) databases. An update of this review is currently ongoing. The search was re‐run September 2012 and the potentially relevant studies are awaiting classification.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, non‐randomised controlled trials, controlled before‐after studies and interrupted time series analyses comparing 1. pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services targeted at patients versus (a) the same services provided by other healthcare professionals, (b) the same services provided by untrained health workers, and (c) usual care; and 2. pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services targeted at healthcare professionals versus (a) the same services provided by other healthcare professionals, (b) the same services provided by untrained health workers, and (c) usual care in low‐ and middle‐income countries. The research sites must have been located in low or middle income countries according to World Bank Group 2009 at the time of the study, regardless of the location or the origin of the researchers.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently reviewed studies for inclusion in the review. Two review authors independently extracted data for each study. Risk of bias of the included studies was also assessed independently by two authors.

Main results

Twelve studies comparing pharmacist‐provided services versus usual care were included in this review. Of the 12 studies, seven were from lower middle income countries and five were from upper middle income countries. Eleven studies examined pharmacist‐provided services targeted at patients and one study evaluated pharmacist interventions targeted at healthcare professionals. Pharmacist‐provided services targeting patients resulted in a small improvement of clinical outcomes such as blood pressure (‐25 mm Hg/‐6 mm Hg and ‐4.56 mm Hg/‐2.45 mm Hg), blood glucose (‐39.84 mg/dl and ‐16.16 mg/dl), blood cholesterol (‐25.7 mg/dl)/ triglyceride levels (‐80.1 mg/dl) and asthma outcomes (peak expiratory flow rate 1.76 l/min). Moreover, there was a small improvement in the quality of life, although four studies did not report the effect size explicitly. Health service utilisation, such as rate of hospitalisation and general practice and emergency room visits, was also found to be reduced by the patient targeted pharmacist‐provided services. A single study examined the effect of patient targeted pharmacist interventions on medical expenses and the cost was found to be reduced. A single study that examined pharmacist services that targeted healthcare professionals demonstrated a very small impact on asthma symptom scores. No studies assessing the impact of pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services that targeted healthcare professionals reported health service utilisation and cost outcomes. Overall, five studies did not adequately report the numerical data for outcomes but instead reported qualitative statements about results, which prevented an estimation of the effect size.

Studies for the comparison of patient targeted services provided by pharmacists versus the same services provided by other healthcare professionals or untrained healthcare workers were not found. Similarly, studies for the comparison of healthcare professional targeted services provided by pharmacists versus the same services provided by other healthcare professionals or untrained healthcare workers were not found.

Authors' conclusions

Pharmacist‐provided services that target patients may improve clinical outcomes such as management of high glucose levels among diabetic patients, management of blood pressure and cholesterol levels and may improve the quality of life of patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and asthma. Pharmacist services may reduce health service utilisation such as visits to general practitioners and hospitalisation rates. We are uncertain about the effect of educational sessions by pharmacists for healthcare professionals due to the imprecision of a single study included in this review. Similarly, conclusions could not be drawn for health service utilisation and costs due to lack of evidence on interventions delivered by pharmacists to healthcare professionals. These results were heterogenous in the types of outcomes measured, clinical conditions and approaches to measurement of outcomes, and require cautious interpretation. All eligible studies were from middle income countries and the results may not be applicable to low income countries.

Plain language summary

The effect of using pharmacists to provide services other than medicine dispensing in low‐ and middle‐income countries

Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a review to evaluate the effect of using pharmacists to provide services other than medicine dispensing in low‐ and middle‐income countries. After searching for all relevant studies, they found 12 studies that met their requirements. Their findings are summarised below.

The use of pharmacists to provide services other than dispensing medication

Traditionally, the main role of the pharmacist has been to prepare and dispense medicines. Recently, however, the number of tasks that are expected of them has grown.They are now often expected to make sure that patients use their medicines properly, help patients solve medicine‐related problems and to give health information that can help patients improve their health.

All of the studies in this review took place in middle income countries, either at outpatient departments, community pharmacies or primary healthcare centres.

In 11 of the studies, pharmacists gave education and counselling to patients with chronic illnesses such as asthma and diabetes. Pharmacists gave the patients information about how to use their medicines properly and about possible side effects of the medicines, and helped them to identify and solve problems with their medicines. They also gave the patients information about the disease and advice about self‐management and the importance of a healthy lifestyle. The patients who were given these services were compared to patients who were given the usual pharmacist services without education or counselling.

In one study, pharmacists gave education to general practitioners (GPs) about care of children with asthma. These GPs were compared to GPs who were given usual pharmacist services.

No studies were found where pharmacist‐provided services were compared to the services provided by other health workers.

What happens when pharmacists provide services other than dispensing medication?

When pharmacists give education and counselling to patients with chronic illnesses:

· patients may experience small improvements in health outcomes such as blood pressure levels and glucose levels (low quality evidence),

· patients may use health services less (for instance fewer visits to the doctor, fewer stays in hospital) (low quality evidence),

· patients probably experience small improvements in quality of life (moderate quality evidence),

· patients’ medication costs may be lower (low quality evidence).

When pharmacists give education and counselling about asthma care to GPs:

· their patients may experience slightly fewer asthma symptoms (low quality evidence).

Summary of findings

Background

Over the past two decades the role of pharmacists has expanded beyond medication dispensing (for example giving medicines to patients), packaging (for example counting and putting pills in a bottle to be given to patients) and compounding (WHO 1998). Pharmacists are increasingly considered as a part of the healthcare system whether in community pharmacies, primary health centres or hospitals (Ghani 2010; WHO 1998).

In light of factors such as socio‐economic status; lifestyle; accessibility; management of acute, chronic and recurrent illness; public health and environmental factors; health sector reforms; availability of new products; and demographic and epidemiological factors there is a trend towards self‐medication and self‐care (WHO 1998). Pharmacists can play an important role in self‐medication and self‐care by providing and interpreting information regarding appropriate health care and medication choices and they promote the rational use of drugs. Furthermore, increased health demand, an increasingly complex range of medicine uses, and poor adherence to prescribed medication have provided additional opportunities for pharmacists to deliver patient targeted services (WHO 2006). The concept of “the seven star pharmacists” was developed by a WHO consultative group, which states that the well‐rounded pharmacist should be a compassionate caregiver, decision‐maker, active communicator, lifelong learner and good manager, and should possess the qualities of a good leader, teacher and researcher (WHO 1997). According to Hepler and Strand 1990, pharmacists are responsible for providing ‘pharmaceutical care’ to improve patients' quality of life; this involves a) identifying potential and actual drug‐related problems, b) resolving actual drug‐related problems, and c) preventing potential drug‐related problems (Hepler 1990). Recently, the concept of medication therapy management (MTM) has been used to further describe collaborative methods to achieve optimal patient outcomes and promote safe and effective medicine use (APAaNAoCDS 2008). MTM services are focused on patient centred care rather than product centred care and are targeted to prevent medication‐related morbidity and mortality. They can be considered as an activity when pharmacists (including but not limited to hospital and community pharmacists) are reimbursed for reviewing patients’ medications and advising them and their carers about necessary changes but without dispensing. MTM services include a medication regimen review, the provision of personal medication records, the construct of a medication‐related action plan (which may include therapeutic recommendations, a provider referral), documentation and follow‐up as needed.

Various patient targeted services, which may be either drug or health‐related, are performed by pharmacists. Pharmacists can compile and maintain information on a patient’s drug history, assist physicians in the rational prescribing of drugs, ensure a patient's understanding of the dosing regimen and method of administration, and help in improving patient adherence (Lipton 1994; WHO 1994). In addition, they may collect and maintain information on all medicines, particularly newly introduced medicines, and provide advice to all healthcare professionals, as necessary (Lipton 1992; WHO 1994). From a public health standpoint, pharmacists may be actively involved in health promotion campaigns like tobacco control; moderate alcohol use; nutrition and healthy lifestyle; routine immunization; management and prevention of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and diarrhoea; and in the management of mental health and other chronic diseases (Aderemi‐Williams 2007; Rosen 1978; WHO 1994).

Contrary to the situation in high income countries, pharmacists are underutilised for patient care in low‐ and middle‐income countries; and the importance of their role as healthcare professionals in hospitals, community pharmacies and healthcare teams has not been well recognized (Anderson 2002). Moreover, although the World Health Organization (WHO) is trying to promote Good Pharmacy Practice (GPP) in all countries, pharmacy practice in low‐ and middle‐income countries is very poor as compared to that in high income countries (Ghani 2010, Smith 2009). GPP is the national standard set for “the promotion of health, the supply of medicines, medical devices, patient self‐care, and improving prescribing and medicine use by pharmacists’ activities” (FIP 1997). Major barriers for effective pharmacy practice in low‐ and middle‐income countries include an acute shortage of qualified pharmacists, the preference of pharmacists to work in urban areas rather than rural areas, failure to implement the separation of dispensing practices between doctors’ clinics and pharmacies, especially in countries where the pharmacists are not the sole dispenser and doctors are allowed to dispense as well, weak regulatory enforcement of drug sales, irrational use of medicines, reliance on untrained health workers for delivery of services, and general poverty (Fabricant 1987; Geest 1987; WHO 1994). Furthermore a focus on profits, which is characteristic of certain dispensing practices, rather than the provision of optimal health care promotes irrational use and prescribing of drugs; this issue may not be unique to low‐ and middle‐income countries. The marketing strategies (the push) of pharmaceutical companies to promote sales combined with the demand for (the pull) or the desirability of modern medicines and their role in preventing diseases are also causes of the irrational use of drugs (Fabricant 1987; Geest 1987; le Grand 1999; WHO 1994). In addition, cultural norms such as the prestige of physicians and the prevalence of polypharmacy, including combining traditional medicines with allopathic medicines, contribute to the irrational use of drugs. The public health consequences of this kind of haphazard drug utilisation result in lethal effects due to inappropriate self‐medication (for example underdosing or overdosing, inappropriate medication selection), antibiotic resistance due to overusage as well as undertherapeutic‐dosage usage, drug dependence due to the use of tranquillizers and painkillers, and high risk of infection due to the improper usage of injections (Geest 1982; Kamat 1998; le Grand 1999). With the serious and widespread public health problem of the irrational use of medicines (Holloway 2006) and the need to improve health outcomes, it is necessary to examine the impact of pharmacists' clinical patient care interventions in addition to standard dispensing and compounding in low‐ and middle‐income countries (WHO 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

Previous systematic reviews have focused on high and low‐ and middle‐income countries, specific settings such as ambulatory care, acute care and long‐term care, and specific patient groups (Beney 2000; Blenkinsopp 2003; Christensen 2006; Horn 2006; Kaboli 2006; Kane 2003; Nkansah 2010; Royal 2006; Singhal 1999; Tully 2000). None of these reviews have evaluated the effects of pharmacist interventions on patient outcomes, health service utilisation and costs by focusing solely on low‐ and middle‐income countries.

The protocol for this review was based on the Cochrane review entitled “Expanding the roles of outpatient pharmacists: effects on health service utilization, costs, and patient outcomes” published in 2000, which included eligible studies published from 1966 to 1999 (Beney 2000) and the updated version of that review, which included studies published up until 2008 (Nkansah 2010). However, the updated review (Nkansah 2010) included only randomised controlled trials whereas the original review (Beney 2000) included a broad range of study designs such as controlled before and after studies, non‐randomised controlled trials and interrupted time series analyses. Few studies (Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Sookaneknun 2004) included in the reviews (Beney 2000; Nkansah 2010) were from low‐ and middle‐income countries and the applicability of the findings of those reviews to low‐ and middle‐income countries are uncertain. Our review includes a broad range of study designs such as randomised controlled trials, controlled before and after studies, non‐randomised controlled trials and interrupted time series analyses.This review, differs from the other two reviews (Beney 2000; Nkansah 2010) by (i) focusing solely on low‐ and middle‐income countries, according to the World Bank’s country classification (World Bank Group 2009), and (ii) by searching for studies with a variety of designs that were published up until January 2010 that met the inclusion criteria.

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effect of pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services on patient outcomes, health service utilisation and costs in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

The following main research questions were examined.

1. In low‐ and middle‐income countries, what are the effects of the delivery of patient targeted services by pharmacists on patient outcomes, the use of health services and costs compared to:

a. delivery of the same services by other healthcare professionals?

b. delivery of the same services by untrained health workers?

c. usual care?

2. In low‐ and middle‐income countries, what are the effects of the delivery of healthcare professional targeted services by pharmacists on patient outcomes, the use of health services and costs compared to:

a. delivery of the same services by other healthcare professionals?

b. delivery of the same services by untrained health workers?

c. usual care?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included in this review.

1. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) randomising either patients or pharmacists or practices (pharmacies) or geographical areas

2. Non‐randomised controlled trials (NRCT)

3. Controlled before‐after studies (CBA) (with at least two intervention sites and two control sites)

4. Interrupted time series analyses (ITS) (with clearly defined dates and at least three data points before as well as after the intervention)

Types of participants

The participants included in this review were pharmacists (or pharmacies) delivering services in outpatient settings other than or in addition to drug compounding and dispensing. Studies analysing services to patients in hospitals or nursing homes were excluded. Studies of pharmacists delivering services to an outpatient pharmacy attached to a clinic or hospital, community pharmacies or primary health centres were included in the review. In studies that were randomised by pharmacy or geographical area, the pharmacy services could have been delivered by pharmacists or pharmacy technicians. Therefore, the profession of the individuals who actually delivered the pharmacy services was determined. The research sites or pharmacies must had been located in low or middle income countries at the time of the study regardless of the location or the origin of the researchers. The low‐ and middle‐income countries were selected according to the World Bank’s country classification (World Bank Group 2009).

Types of interventions

All pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services were considered as an intervention. However, there is no agreed upon terminology that defines pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services, and various terms have been used interchangeably to refer to the same services for example non‐distributive or non‐dispensing services. In this review, this term refers to drug‐related patient targeted services delivered by pharmacists other than drug compounding and dispensing. Other services not related to pharmaceutical products, such as the selling of cosmetics, were excluded. To be included, educational or counselling sessions had to be extended or patients had to be continuously followed‐up compared to the one to two minute basic counselling typically offered. The content of each intervention including recipients, format, source, timing, setting, and cost were noted, when available.

Types of outcome measures

Our outcomes of interest included patient outcomes (clinical outcomes, quality of life) and healthcare process outcomes such as health service utilisation (rate of hospitalisation and number of general physician visits) and costs. Subjective outcomes such as self‐reporting of symptom or satisfaction level were not included in this review. Studies were included only if they reported objective measurement of an outcome. If the study measured only subjective outcomes, it was excluded. We did not include adverse effects as we did not anticipate that any studies would measure them.

Search methods for identification of studies

Studies were identified by electronically searching the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2010), MEDLINE (1949 to September 2010), Scopus (1960 to 2010) and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to January 2010). An update of this review is currently ongoing. The search was re‐run September 2012 and the potentially relevant studies are awaiting classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). In MEDLINE, a broad search was conducted by using the MeSH headings ‘pharmacy’, ‘pharmacist’ and various publication types such as ‘randomised controlled trial’, ‘controlled clinical trial’ along with synonyms for ‘low or middle‐income countries’ and names of low‐ and middle‐income countries according to the World Bank’s list (World Bank Group 2009). The search strategies were modified according to the database indicated in Appendix 2. In addition, the reference lists of all eligible studies were checked.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently selected the trials to be included in the review. Disagreements were resolved by discussion of the articles by at least two of the authors of the review. Two phases of study selection were performed. Firstly, only titles and abstracts were assessed for inclusion. In the next phase, the full texts of potentially eligible studies were reviewed thoroughly. Only studies excluded in the second phase were presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies, with the reason for exclusion. In the case of ambiguity, further information was sought from the authors to make a decision about eligibility. References were managed using Endnote X3.

Data extraction and management

Data from the eligible studies were independently extracted by two authors using an electronic data extraction checklist. The included studies are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. Studies that were excluded are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table with the reasons for exclusion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two authors using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) data extraction checklist for each included study design. The discrepancies were adjudicated by discussion of the studies.

1. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled trials without random allocation (quasi‐RCTs): sequence generation; concealment of allocation (protection against selection bias); similar baseline outcome measurements, similar baseline characteristics, blinded assessment of outcome(s) (protection against detection bias); incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, protection against contamination, free from selective outcome reporting and free from other risks of bias.

2. Interrupted time series analyses (ITS): intervention independent of other changes, shape of the intervention effect pre‐specified, intervention unlikely to affect data collection, knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study, incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, study free from selective outcome reporting and study free from other risks of bias.

3. Controlled before and after studies (CBA): sequence generation; concealment of allocation (protection against selection bias); baseline outcome measurement similar, baseline characteristics similar, blinded assessment of primary outcome(s) (protection against detection bias); incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, protection against contamination; free from selective outcome reporting and free from other risks of bias.

The risk of bias for outcomes was summarized either as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias for each individual study. For included studies, the risk of bias characteristics are described in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Measures of treatment effect

Results for baseline (pre‐intervention) and end‐of‐study (post‐intervention) periods were reported, if available, in the Data and analyses tables. Where possible, pre‐post intervention differences for each outcome for the control and intervention groups and the difference in the pre‐post intervention change between study groups were calculated. For each outcome, statistical significance was provided in the significance column and, if available, whether the results were statistically significant were reported. The outcomes reported in each study are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table and the results for each outcome are reported in the Data and analyses tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As variations in outcomes and interventions were anticipated, the results were not statistically combined.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analysis was conducted as quantitative synthesis of results was not anticipated.

Results

Description of studies

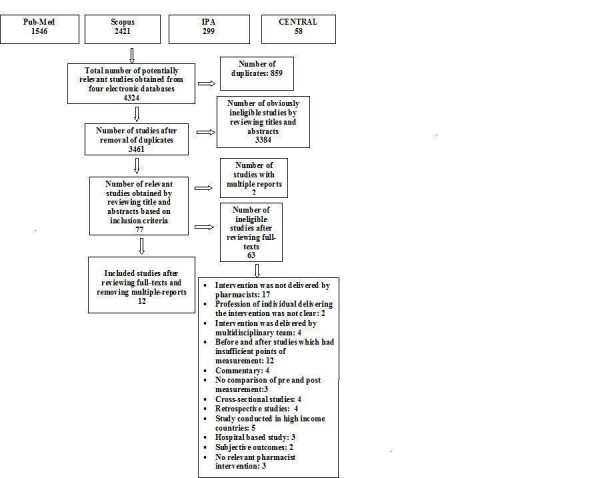

The full texts of 77 studies were retrieved (Figure 1). Of these, two studies were multiple reports and 63 studies did not meet the review inclusion criteria. Twelve studies were included. All of these were randomised controlled trials (RCT). Of the 12 studies, seven were from lower middle income countries and five were from upper middle income countries. Details of the included studies are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1.

Prisma flow chart.

Characteristics of the interventions

Of the 12 included studies, 11 examined pharmacist interventions targeted at patients (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005) and one study evaluated a pharmacist intervention targeted at healthcare professionals (Zwarenstein 2007).

All studies involved comparisons between pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services and usual care. Comparisons of pharmacist‐provided services targeted at patients versus services delivered by other healthcare professionals or untrained healthcare workers were not found. Similarly, comparisons of pharmacist‐provided services targeted at healthcare professionals versus services delivered by other healthcare professionals or untrained healthcare workers were not found. Eleven of 12 studies were randomised by patient and one study was cluster randomised by general practice.

In 11 studies targeted at patients, the main aim of the pharmacist intervention was patient education and counselling (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009; Lugo 2007; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005). The main content of educational sessions and counselling included information about the mechanism of disease and associated risk factors, pharmacotherapy (dosage, duration, route of administration, possible adverse effects of medications and training on using medication devices) and non‐pharmacological measures of controlling disease including lifestyle, diet modifications and self‐management. Four of 11 studies involved complete pharmaceutical care follow‐up by providing patient education; pharmaceutical therapy optimisation; monitoring of disease control; compliance assessment; identifying and resolving drug‐related problems; and maintaining manual records for each patient by recording personal data such as drug therapy, adherence to treatment, lifestyle, drug‐related problems and other clinical variables such as blood pressure and level of triglycerides (Ebid 2006; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Sookaneknun 2004). Specifically designed educational booklets explaining the disease, medication and lifestyle modifications were also provided to patients in seven of 11 studies (Adepu 2007; Ebid 2006; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005). Counselling using a booklet and a special medication container were also provided to the patients in one study (Suppapitiporn 2005). Details are in Table 3.

1. Comparison between interventions (Analysis 1c).

| Patient Outcomes (∆I ‐ ∆C) | Health Service utilisation (∆I ‐ ∆C) | Costs (∆I ‐ ∆C) | ||||||

| Intervention | Blood Glucose Outcome | Blood Pressure (BP) Outcome | Blood Cholesterol | Asthma/COPD outcome | Arthritis Outcome | Rate of Hospitalisation | GP Visits | Medication Cost |

| Counselling/ Patient Education |

Arun et al 2008 Fasting plasma glucose: ‐39.84 mg/dl † Suppapitiporn et al 2005 Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) mg%: ‐19.26† HbA1c (mg %): ‐1.23† |

No studies |

Gonzalez et al 2003 PAQLQ score emotion: 1.3† activities:2.1† symptoms: 1.7† Spirometric values FVC: ‐.14‡ FEV1: ‐.1‡ |

No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | |

| Counselling/ Patient Education + Booklet |

Adepu et al 2007 Random Blood Glucose level (BGL): ‐53.71 mg/dl QOL significantly improved in I group as compared to C group * Suppapitiporn et al 2005 Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) mg%: ‐10.44† HbA1c (mg %): ‐.99† |

No studies | No studies |

Petkova et al 2008 PEF (l/min.): 1.76† QOL: 0.61† |

Petkova et al 2009 Small but statistically significant improvement in QOL (Arthritis interference in patient’s daily routine) in I group as compared to C group* |

Petkova et al 2008 <2‐3 times: 19.2%† >6 times: ‐4.6%† |

Petkova et al 2008 ‐15.7%† |

No studies |

|

Counselling + Drug Review |

No studies | No studies | No studies |

Abdeilhamid et al 2008 non‐significant improvement in Peak Expiratory Flow rate* |

No studies |

Abdeilhamid et al 2008 decreased significantly in intervention group (P<0.05) while non‐significantly increased (P>0.05) in control group |

No studies | No studies |

| Pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up +Patient education +Booklet | No studies |

Lugo de Ortellado et al 2007 Systolic BP: ‐25 mmHg† Diastolic BP: ‐‐6†mmHg Sookaneknun et al 2004 Systolic BP: ‐4.56 † mmHg Diastolic BP: ‐2.45 mmHg† |

Paulos et al 2005 Blood Cholesterol : ‐25.7 mg/dl† Blood Triglyceride Systolic BP : ‐80.1 mg/dl † QOL: significant improvement* |

Ebid et al 2006 HRQOL: Significant improvement in I group as compared to C group for both patients of asthma and COPD* |

No studies |

Ebid et al 2006 Number of ER visits and hospitalisation for both patients of asthma and COPD: Significantly decreased in I group as compared to C group* |

Ebid et al 2006 Number of visits to PCs or OPCs: Significantly decreased in I group as compared to C group for both patients of asthma and COPD* |

Ebid et al 2006 Significantly reduced in I group as compared to C group for both patients of asthma and COPD* |

| Counselling + Booklet+ Special medication container |

Suppapitiporn et al 2005 Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) mg%: ‐26.25 † HbA1c (mg %): ‐1.08† |

No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Counselling + Special medication container |

Suppapitiporn et al 2005 Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) mg%: ‐7.57† HbA1c (mg%): ‐0.75† |

No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Notes | I = Intervention (∆I ‐ ∆C): Change due to intervention (intervention versus control group) C = Control * Exact value not reported †Significant ‡ Not significant QOL: Quality of Life |

|||||||

Four of 11 studies were conducted in the outpatient departments of hospitals (Abdelhamid 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Suppapitiporn 2005), five studies took place in a community pharmacy (Adepu 2007; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009), one study was conducted in primary health centres (Arun 2008; Sookaneknun 2004) and one study took place in both a primary health centre and community pharmacy (Sookaneknun 2004). The duration of the intervention ranged from 20 to 50 minutes with three to 11 interventions conducted over a period of nine weeks to six months.

One of 12 studies targeted healthcare professionals. In this study, pharmacists provided educational sessions to general practitioners (GPs) which contained eight key messages aimed at improving diagnosis, prescribing and follow‐up care for children with asthma. The intervention was academic detailing and tools such as visual aids were used (Table 4). Educational sessions were conducted in general practices. The duration of the intervention was 30 minutes and two interventions were conducted over 12 weeks (Zwarenstein 2007).

2. Comaprison between interventions (Analysis 2c).

| Patient Outcomes (∆I ‐ ∆C) | Health Service utilisation (∆I ‐ ∆C) | Costs (∆I ‐ ∆C | ||||||

| Intervention | Blood Glucose Outcome | Blood Pressure (BP) Outcome | Blood Cholesterol | Asthma/COPD outcome | Arthritis Outcome | Rate of Hospitalisation | GP Visits | |

| Academic detailing to GP + visual aids | No studies | No studies | No studies |

Zwarenstein et al 2007 Asthma symptom score: ‐0.85 † |

No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Notes | I = Intervention (∆I ‐ ∆C): Change due to intervention (intervention versus control group) C = Control * Exact value not reported †Significant ‡ Not significant |

|||||||

The control group received usual care in each of the 12 studies. Usual care entailed traditional care provided by pharmacies or primary healthcare units without comprehensive pharmaceutical care and follow‐up or patient education or counselling. However, in one of the studies the control group received the intervention at the end of the study ( Adepu 2007). In one study there was one control group and four intervention groups (Suppapitiporn 2005). In this study, diabetic drug counselling was provided by a pharmacist to all intervention groups; one group had an additional diabetes booklet, another had special medication containers and the third group was provided with diabetes education, a diabetes booklet and special medication containers.

Characteristics of providers delivering the intervention

In all studies, the interventions were performed either by practicing pharmacists or research pharmacists. In four studies, a single pharmacist provided the intervention (Abdelhamid 2008; Paulos 2005; Sookaneknun 2004, Suppapitiporn 2005; Zwarenstein 2007). However, the number of pharmacists was not clear in most of the studies (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Lugo 2007). In two studies the intervention was delivered by both a pharmacist and pharmacy students who had passed an examination in pharmaceutical care (Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009).

Target population

All 11 studies targeted patients based on their disease state. Three targeted patients with asthma (Abdelhamid 2008; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Petkova 2008), three selected patients suffering from type‐2 diabetes mellitus (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Suppapitiporn 2005) and one targeted patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Ebid 2006). Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2009 and Sookaneknun 2004 selected patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis and hypertension respectively.

In a study examining pharmacist interventions with GPs, participants were selected based on their location, in Mitchells Plain, Cape Town South Africa (Zwarenstein 2007). The main aim of the study was to improve diagnosis, prescribing and follow‐up care provided by GPs for children with asthma.

The number of participants ranged from 21 to 360 patients and 43 general practices. One patient targeted study included pediatric patients and another study targeted participants aged 14 years and over. The other studies targeted adults aged 18 years and over.

Characteristics of countries

Single studies were conducted in Sudan, Egypt, Paraguay and South Africa (Characteristics of included studies). In addition, two studies were conducted in each of Chile, Thailand, Bulgaria and India. Of the 12 studies, seven were from lower middle income countries and five were from upper middle income countries. Eligible studies conducted in low income countries were not identified (Characteristics of excluded studies).

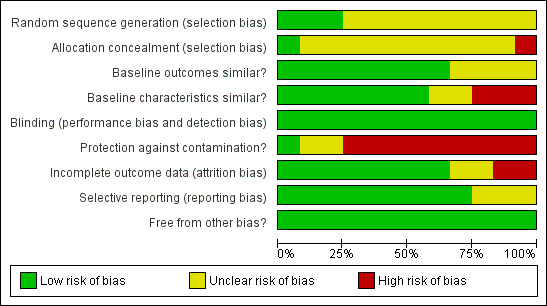

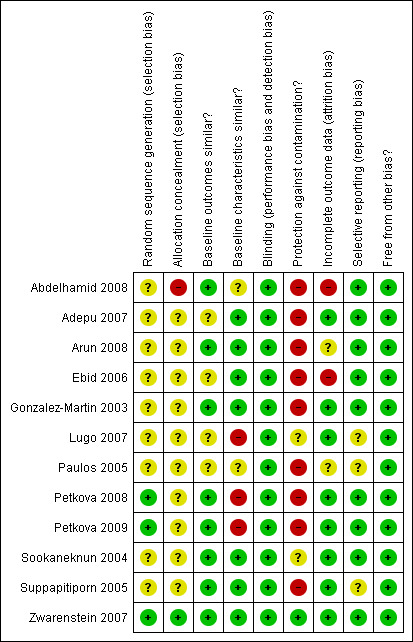

Risk of bias in included studies

The analysis of the risk of bias present in the included studies is presented in the Risk of bias in included studies table under each study in the section presenting the Characteristics of included studies. A graphical representation of risk of bias is given in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Eleven of the 12 studies in this review had a risk of bias. Only three of 12 studies had an adequately generated sequence for randomisation (Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009; Zwarenstein 2007). Ten of 12 studies did not explicitly describe whether allocation concealment was done (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003,Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005) and in one study an on‐site computer system was used for the allocation concealment (Zwarenstein 2007). Baseline measurements of outcomes were comparable in only four of 12 studies (Abdelhamid 2008; Arun 2008; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Petkova 2008), however it was unclear in the other four studies (Adepu 2007; Ebid 2006; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005). Baseline characteristics were similar between the intervention group and control group in seven of 12 studies (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005; Zwarenstein 2007), however it was unclear in the other two studies (Abdelhamid 2008; Paulos 2005). Furthermore, there was high risk of bias for the protection against contamination in nine studies (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009; Suppapitiporn 2005) and unclear in two studies (Lugo 2007; Sookaneknun 2004). As only objective outcomes were included in this review, all studies were coded as having blinded assessment of outcomes. There was high risk of bias in assessment of outcome data in two of 12 studies (Abdelhamid 2008; Ebid 2006), unclear in two studies (Arun 2008; Paulos 2005) and at low risk of bias in the rest of the studies. The absence of selective reporting of results could not be assessed in Gonzalez‐Martin 2003, Paulos 2005 and Suppapitiporn 2005 as the outcomes to be measured was not listed in the methods sections of the studies. Other forms of bias were not identified in all 12 studies.

Effects of interventions

for the main comparison.

| 1(c) Comparison of the delivery of patient targeted services by pharmacists versus usual care | |||

|

Patient or population: Pharmacies or pharmacists delivering services in outpatient settings and patients with various diseases* Settings: Chile (2), Thailand (2) , Bulgaria (2), India (2), Sudan (1), Egypt(1) and Paraguay (1) Intervention: Counselling/Patient Education (3), Counselling/Patient Education + Booklet (4), Counselling + Drug Review (1), Pharmaceutical plan with scheduled follow‐up + Patient education + Booklet (4), Counselling + Booklet + Special medical container (1), Counselling + Special medical container (1) Comparison: Usual care provided by pharmacists | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Clinical outcomes (fasting blood glucose,random blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin, systolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, peak expiratory flow rate; follow‐up: 16 to 24 weeks) (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Lugo 2007; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Sookaneknun 2004; Suppapitiporn 2005; Zwarenstein 2007) |

Small improvements in outcomes | 1791 (10) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

|

Quality of life (measured with asthma specific assessment form, brief pain inventory for arthritis, paediatric asthma quality of life questionnaire, SF‐36, diabetes dependent quality of life questionnaire, health related quality of life for asthma/COPD; follow‐up 9 to 24 weeks) (Abdelhamid 2008; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009) |

Small improvements in quality of life | 777 (7) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 |

|

Health service utilisation (rate of hospitalisation, emergency room visits, general practitioner visits; follow‐up: 18 to 20 weeks) (Abdelhamid 2008, Ebid 2006; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009) |

Decreased health service utilisation | 590 (4) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

|

Cost (follow‐up: 6 months) (Ebid 2006) |

Reduction in cost |

350 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1. The quality of evidence was downgraded to 'low' because of study limitations (risk of bias) in most of the studies and due to the inconsistencies (heterogeneous outcome)

2. The quality of evidence was downgraded to 'moderate' due to the inconsistencies (heterogeneous outcome)

3. The quality of evidence was downgraded to 'low' because of the inclusion of a single study and imprecision round the estimate of effect .

2.

| 2(c) Comparison of the delivery of healthcare professional targeted services by pharmacists versus usual care | |||

|

Patient or population: Pharmacies or pharmacists delivering services in outpatient settings and asthmatic patients Settings: South Africa (1) Intervention: Educational sessions to general practitioners (GPs) aimed at improving diagnosis, prescribing and follow‐up care Comparison: Usual services | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Patient Outcome Asthma symptom score (0‐9 score, where 9 indicates maximum impairment and 0 indicates no impairment) (follow‐up: 3 months) |

Mean difference of asthma symptom score was ‐0.85 between intervention and control group | 43 general practices/ 318 asthmatic children (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

| Health Service Utilisation | No Studies | ||

| Cost | No Studies | ||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1.The quality of evidence was downgraded to 'low' due to imprecision and only one study included.

All included outcomes are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table and the Data and analyses tables.

No studies were identified that met the criteria for comparison of the delivery of patient targeted services by: (a) pharmacists versus other healthcare professionals, and (b) pharmacists versus untrained health workers.

Comparison of the delivery of patient targeted services by pharmacists versus usual care

Eleven of 12 studies that compared the effect of pharmacist interventions targeted at patients versus usual care were included in this review. Detailed descriptions are presented in Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (c) Comparison of the delivery of patient targeted services by pharmacists versus usual care, Outcome 1 Outcomes.

| Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes |

Pre‐ Intervention (intervention vs. control group) |

Post‐ Intervention (intervention vs.control group) |

Change due to intervention (intervention vs. control group) |

Result‐interval(ΔI‐ΔC) | Significance | Notes |

| Abdelhamid 2008 | PATIENT 1) Peak expiratory flow rate |

not reported | not reported | not reported | non‐sig.** | p>0.05 | *calculated from reported data **exact value not reported |

| Abdelhamid 2008 | PROCESS 1) Rate of hospitalisation |

not reported | not reported | not reported | decreased significantly in intervention group (p<0.05) while non‐significantly increased (p>0.05) in control group | p<0.05† | †p‐value for intervention vs. control at the end of study |

| Adepu 2007 | PATIENT 1) Blood Glucose level(BGL) 2) ADDQOL score |

198.31 mg/dl vs 173.6 mg/dl not reported |

142 mg/dl vs 171 mg/dl not reported |

‐56.31 vs ‐2.6 not reported |

‐53.71 mg/dl Significant improvement in intervention group as compared to control group † |

p<0.01* p<0.001* |

†exact value not reported * statistically significant |

| Adepu 2007 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Arun 2008 | PATIENT 1) Fasting Plasma glucose level (mg/dl) 2) Over all Health related Quality of life (HRQoL) |

140.04 (24.16) vs 134.38 (20.46) 11.70 vs. 11.87 |

115.1 vs 149.28 16.94 vs. 11.66 |

‐24.94±12.54 vs.14.9±11.24 5.24 vs. ‐0.21 |

‐39.84† 5.45† |

p=0.0001* not reported |

*Statistically significant ‡not significant †calculated from reported data |

| Arun 2008 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Ebid 2006 | PATIENT Patients with COPD 1) HRQOL a.General Health b.Unhealthy days (physically) c. Unhealthy days (mentally) d. Days of activity limitation 2. PEFR,% predicted Asthmatic patients 1) HRQOL a. General Health b. Unhealthy days (physically) c. Unhealthy days (mentally) d. Days of activity limitation 2) PEFR,% predicted |

a. not reported b.not reported c.not reported d. not reported 2.51.2± 8.6 vs 50.3 ±8.5 a. not reported b. not reported c.not reported d.not reported 2. not reported |

a. 3.8±0.9 vs. 1.9±0.7 b. 4.8±1.0 vs.8.1±2.3 c. 5.1±1.0 vs. 7.5±2.3 d. 6.2±1.3 vs. 12.0±3.1 2. 56.2±19.4 vs. 50.3±18.1 a. 4.1±0.7 vs. 2.5±0.9 b. 3.6±0.8 vs. 7.7±2.3 c. 4.5±0.9 vs. 6.8±2.3 d. 4.3±0.8 vs. 10.2±3.7 2. 87.2±11.2 vs.70.8±13.2 |

a. not reported b. not reported c. not reported d. not reported 2. 5.0 vs 0 a. not reported b. not reported c.not reported d. not reported 2. not reported |

a. not reported b. not reported c. not reported d. not reported 2. 5.0 a. not reported b. not reported c. not reported d. not reported 2. not reported |

a. p* b. p* c. p* d. p* 2. p† a. p* b. p* c. p* d. p* 2. p* |

*exact value not reported, however, significant improvement in the intervention group as compared to control group †Not significant |

| Ebid 2006 | PROCESS Patients with COPD 1) Number of visits to PCs or OPCs 2) Number of ER visits and hospitalisation 3) Costs for patient with COPD Asthmatic patients 1) Number of visits to PCs or OPCs 2) Number of ER visits and hospitalisation 3) Costs for patient with Asthma |

1) not reported 2) not reported 3) not reported 1) not reported 2) not reported 3) not reported |

1)1.8±0.4 vs. 3.9±0.9 2) 0.81±0.16 vs.1.9±0.68 3) 340±116 vs.902±342 1) 1.1±0.20 vs. 2.2±0.51 2) 0.34±0.10 vs. 0.73±0.27 3) 225±77 vs.491±177 |

1) not reported 2) not reported 3)not reported 1) not reported 2) not reported 3) not reported |

1)not reported 2) not reported 3) not reported 1) not reported 2) not reported 3) not reported |

1) p* 2) p* 3) p* 1) p* 2) p* 3) p* |

*exact value not reported, however, significant improvement in the intervention group as compared to control group |

| Gonzalez‐Martin 2003 | PATIENT 1) Paediatric asthma quality of life questionnaire (PAQLQ) score 1) emotion 2) activities 3) symptoms 2) Spirometric values a. FVC b. FEV1 |

1) 5.2±0.4 vs. 5.2±0.4 2) 3.8 ±0.3 vs. 4.0±0.3 3) 4.1±0.5 vs. 4.6±0.4 a. 3.08±0.97 vs. 2.66 ± 0.19 b. 2.41 ±0.76 vs. 2.34 ±0.22 |

1) 6.5 vs. 5.2‡ 2) 6 vs. 4.1‡ 3) 6 vs. 4.8‡ a. 3.13±1.14 vs. 2.85±0.29 b. 2.48±0.89 vs. 2.51±0.27 |

1) 1.3vs 0† 2) 2.2 vs. 0.1† 3) 1.9 vs. 0.2† a. 0.05 vs. 0.19† b. 0.07 vs. 0.17† |

1) 1.3

2) 2.1 3) 1.7 a. ‐.14 b. ‐.1 |

1) p<0.01 2) p<0.01 3) p<0.02 a. p=n.s* b. p=n.s* |

* exact p‐value not provided †calculated from reported data ‡data extrapolated from a graph |

| Gonzalez‐Martin 2003 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Lugo 2007 | PATIENT 1) Systolic‐ blood pressure (mmHg) 2) Diastolic‐ blood pressure (mmHg)† 3) Percentage of patients in various categories of hypertension † |

1) 147 vs. 148 2) 89 (intervention group) 3) 45% in stage II, 42% in stage I, 9% in pre‐hypertension and 3% in normal (intervention group) |

1) 128 vs. 154 2) 83 (intervention group) 3) 9% in stage II, 45% in stage I, 39% in pre‐hypertension and 6% in normal (intervention |

1) ‐19 vs. 6 2) ‐6 vs. 0 ** 3) ‐36% in stage II, ‐3% in stage II, 30% in pre‐hypertension and 3% in normal (intervention group) |

1) ‐25 2) ‐6 3) not reported |

1) p<0.05* 2) p<0.05* 3)p<0.0001*‡ |

‡p‐value for change in intervention group over study period *statistically significant **no change in control group reported †exact value for control group is not reported |

| Lugo 2007 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Paulos 2005 | PATIENT 1) Blood Cholesterol level (mg/dl) 2)Triglyceride level (mg/dl) 3) % of patients with decrease in total cholesterol 4) % of patients with decrease in triglyceride level. 5) QOL index |

1) 205.1±44.7 vs. 203.2±40.6 2) 190.7±88.7 vs. 163.6±116. 3) not reported 4) not reported 5) not reported |

1) 178.1±31.1 vs. 199.1±37.6 2) 140.3±47.6 vs. 193.2±108.0 3) 72.8 vs. 33.3 4) 77.3 vs. 27.8 5) not reported |

1) ‐27.1±41.1 vs. ‐1.4±37.2 2)‐50.5±80.3 vs. 29.6±118.5 3) not reported 4) not reported 5) not reported |

1) ‐25.7 2) ‐80.1 3) not reported 4) not reported 5) Significant improvement in intervention as compared to control |

1) p=0.0266* 2) p=0.0169* 3) not reported 4) not reported 5)p<0.002† |

*p‐value for change in intervention group over study period †p‐value for intervention vs. control at the end of study |

| Paulos 2005 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Petkova 2008 | PATIENT 1) PEF rate (L/min.) 2) QOL |

1) 335.45±15.73 vs. 332.14±14.49 2) 3.55±1.33 vs. 3.39±0.68 |

1)338.64±12.55 vs. 333.57±14.00 2) 3.77±1.02 vs. 3.00±0.90 |

1) 3.19 vs. 1.43 2) 0.22 vs. ‐.39 |

1) 1.76 2) 0.61 |

1) p<0.05* 2) p<0.001† p=0.039‡ |

*p‐value for intervention vs. control at the end of study †‐p‐value for change in intervention over a study. ‡p‐value for change in control over a study period |

| Petkova 2008 | PROCESS 1)Hospitalisation rate 2) Visit to G.P i) <2‐3 times ii) >6 times |

1) 36.4% vs. 85.7% 2) i) 63.7% vs. 17.9% ii) 9.1% vs.3.6% |

1) 13.6% vs. 78.6% 2) i)86.4% vs. 21.4% ii) 4.5% vs. 3.6% |

1) ‐22.8% vs. ‐7.1% 2) i) 22.7 % vs. 3.5% ii) ‐4.6% vs.0% |

1) ‐15.7% 2) i) 19.2% ii) ‐4.6% |

1) p=0.001* 2) p=0.018† |

*p‐value for intervention vs. control at the end of study †‐p‐value for change in intervention over a study |

| Petkova 2009 | PATIENT Arthritis interference in patients’ daily routine. Pain interference with i) General activity ii) Mood iii) Walking ability iv) Normal Work v) Relation with other people vi) Sleep vii) Enjoyment of life |

i) 7.63±1.235 vs. 7.67±1.229 ii) 7.16±1.851 vs. 7.14±1.612 iii) 7.93±1.370 vs.8.00±1.272 iv) 6.81±2.228 vs. 6.51±2.120 v) 4.26±2.391 vs. 4.00±2.370 vi) 7.98±1.752 vs. 8.09±1.231 vii) 6.95±1.812 vs. 6.93±1.737 |

i) 7.47±1.316 vs. 7.63±1.134 ii) 6.95±1.690 vs. 7.09±1.630 iii) 7.72±1.368 vs.7.88±1.258 iv) 6.67±2.212 vs. 6.56±1.980 v) 4.14±2.210 vs. 3.74±2.183 vi) 7.79±1.390 vs. 8.02±1.282 vii) 6.58±1.803 vs. 7.09±1.90 |

i) ‐0.16 vs. ‐0.04* ii) ‐0.21 vs. ‐0.05* iii) ‐0.21 vs. ‐0.12* iv) ‐0.14 vs. 0.05* v) ‐0.12 vs. ‐0.26* vi) ‐0.19 vs.‐0.07* vii) ‐0.37 vs. 0.16* |

i) ‐0.12 ii)‐0.16 iii) ‐0.09 iv) ‐0.19 v) 0.14 vi) ‐0.12 vii) ‐0.53 |

i) p <0.05 ‡ ii) p <0.05 ‡ iii) p <0.05 ‡ iv) p <0.05 ‡ v) p <0.05‡ vi)p <0.05‡ vii) p <0.05‡ |

*calculated from the reported data. ‡p value for change in intervention group over a study period. |

| Petkova 2009 | PROCESS Visits to GP i) Not at all ii)More than six times |

i) 7% vs. 7% ii) 23.3% vs. 18.6% |

i) 18.6% vs.2.3% ii)9.3% vs.18.6% |

i)11.6% vs.‐4.7% ii) ‐14% vs.0% |

i) 16.3% ii)‐14% |

p=0.003‡ p<0.05‡ |

‡p value for change in intervention group over a study period. |

| Sookaneknun 2004 | PATIENT 1) Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 2) Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 3)% of patients controlled for systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure |

1) 144.76±19.69 vs. 142.41±19.81 2) 85.72±13.56vs 85.86±12.94 3) 22.88 vs. 17.94 |

1)121.47±14.90 vs.

124.77±17.97 2) 71.55±10.80 vs. 74.23±11.87 3) 66.10 vs.57.26 |

1) ‐23.29 ±19.10 vs. ‐18.64±17.67 * 2) ‐14.18 vs. ‐11.73* 3) 43.22 vs. 39.32 * |

1) ‐4.56 2) ‐2.45 3) 3.9 |

1) p<0.001 2) p<0.001 3) p =0.061 |

*calculated from reported data |

| Sookaneknun 2004 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

| Suppapitiporn 2005 | PATIENT a. All Intervention group vs. Control group 1) FPG (mg %) 2) HbA1c (mg%) b.Intervention1 vs. Control 1) FPG (mg %) 2) HbA1c (mg %) c.Intervention 2 vs. Control 1) FPG (mg %) 2) HbA1c (mg %) d. Intervention 3 vs. Control group 1) FPG (mg %) 2) HbA1c (mg %) e. Intervention 4 vs. Control 1) FPG (mg %) 2) HbA1c (mg %) |

a. 1) 152.36±39.73 vs. 150.16±41.78 2) 8.16±1.44 vs. 8.01±1.51 b. 1) 147.46±36.07 vs. 150.16±41.78 2) 8.20±1.07 vs. 8.01±1.51 c. 1)139.78±33.15 vs.150.16±41.78 2) 7.92±1.40 vs. 8.01±1.51 d. 1) 168.60±39.30 vs. 150.16±41.78 2) 8.36±1.74 vs. 8.01 ±1.51 e. 1) 162.42±44.42 vs. 150.16±41.78 2) 8.07±1.53 vs. 8.01±1.51 |

a. 1) 145.20±46.0 vs. 159.16±54.90 2) 7.91±1.27 vs. 8.80±1.36 b. 1)130.21±33.96 vs.159.16±54.90 2) 7.91±1.11 vs. 8.80±1.36 c. 1) 141.21±45.8 vs. 159.16±54.90 2) 7.96±1.31 vs. 8.80±1.36 d. 1)158.34±57.81 vs. 159.16±54.90 2) 7.92±1.04 vs. 8.80±1.36 e. 1)160.98±50.39 vs. 159.16±54.90 2) 7.87±1.47 vs. 8.80±1.36 |

a. 1) ‐7.16 vs. 9 2) ‐0.25 vs. 0.79 b. 1) ‐17.25 vs. 9 2)‐.29 vs. 0.79 c. 1) 1.43 vs. 9 2) 0.04 vs. 0.79 d. 1) ‐10.26 vs. 9 2) ‐0.44 vs. 0.79 e. 1) ‐1.44 vs. 9 2) ‐0.2 vs. 0.79 |

a. 1) ‐16.16 2) ‐1.04 b. 1) ‐26.25 2) ‐1.08 c. 1) ‐7.57 2) ‐0.75 d. 1) ‐19.26 2) ‐1.23 e. 1)‐10.44 2) ‐.99 |

a. 1) p=0.013*† 2) p<0.001*† b. 1) p=0.016*‡ 2) p=0.001*‡ c. 1)n/a 2) p=0.005*‡ d. 1) not reported 2) not reported e. 1) not reported 2) p=0.000*‡ |

*statistical significant difference †p‐value for intervention vs. control at follow up ‡p‐value for change in intervention group over a study. |

| Suppapitiporn 2005 | PROCESS n/a |

||||||

Clinical outcomes

All studies targeting patients reported patient outcomes. Patient targeted pharmacist interventions resulted in improvement in most of the clinical outcomes, although the improvement was not always statistically significant. The peak expiratory flow rate increased by 1.76 l/min in the intervention group as compared to the control group in one study (Abdelhamid 2008) however the result was not statistically significant. The effect size of the improvement of peak expiratory flow rate was not reported in the other study although the result was statistically significant (Petkova 2008). In patients with asthma, a statistically significant difference was not found in forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory flow (FEV) from spirometry testing before and after the intervention (Gonzalez‐Martin 2003). Two studies demonstrated a reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Lugo 2007; Sookaneknun 2004). Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure due to pharmacist intervention (Lugo 2007; Sookaneknun 2004) was ‐25 mm Hg and ‐6 mm Hg and ‐4.56 mm Hg and ‐2.45 mm Hg, respectively. However, in one study, reporting of standard deviations was incomplete (Lugo 2007). Two studies targeting diabetic patients showed a statistically significant reduction in the fasting plasma glucose level (Arun 2008; Suppapitiporn 2005) and one study showed a statistically significant reduction in the random blood glucose level (Adepu 2007). The reduction in fasting plasma glucose levels due to pharmacist interventions (Arun 2008; Suppapitiporn 2005) was ‐39.84 mg/dl and ‐16.16 mg/dl, respectively. In patients with diabetes, the glycosylated haemoglobin level decreased by ‐1.04% in the intervention group as compared to the control group (Suppapitiporn 2005). When each intervention versus control was analysed in this study, the mean percentage point difference between the intervention and control groups ranged from ‐0.75% to ‐1.23 %. In one study, the total cholesterol level and triglyceride level of the dyslipidemic patients decreased by ‐25.7 mg/dl and ‐80.1 mg/dl in the intervention group as compared to the control group, respectively (Paulos 2005). In the same study, there was an increase in the proportion of patients with decreased cholesterol.

Overall, pharmacist‐provided services targeted towards the patient point to small improvements in some of the clinical outcomes such as management of high glucose levels among diabetic patients and management of blood‐pressure and cholesterol levels. For outcomes such as peak expiratory flow rate and forced vital capacity, we could not rule out the role of chance in these findings.

Quality of life outcomes

Seven of 11 studies reporting patient outcomes collected data on quality of life outcomes (QOL) by using various QOL questionnaires (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009). One study targeted at diabetic patients showed a statistically significant improvement in QOL; however numerical data for this effect were not reported (Adepu 2007). A second study targeting diabetic patients reported an increment in QOL score by 5.45 (score range 0 to 30) in the intervention group, but it was not clear whether this result was statistically significant (Arun 2008). In Gonzalez‐Martin 2003, there was an increment of the emotion, activities and symptom score (on a scale range from 1 to 7 for each item) by 1.3, 2.1 and 1.7, respectively, in the intervention group as compared to control group. The mean difference of the QOL score assessed by using an asthma specific assessment form (score range 1 to 5) was 0.61 between the intervention and control groups in Petkova 2008. Small but statistically significant improvements in QOL were reported in a study targeting arthritic patients (Petkova 2009). A study targeting dyslipidemic patients also showed a statistically significant improvement in QOL (Paulos 2005), however the effect size was not reported. Lastly, another study targeting patients with asthma and COPD demonstrated a statistically significant increment in QOL score in the intervention group, but the difference between the intervention and control groups was not reported (Ebid 2006). Due to the poor reporting, the overall effect size of improvement in QOL by the pharmacist intervention could not be estimated as the included studies used different measures of QOL or reported different outcomes. However, most of the studies showed a statistically significant improvement in QOL score.

In summary, the measurement of QOL in the seven studies varied greatly but suggests that pharmacist interventions targeting patients may improve the QOL outcomes.

Process outcomes (health service utilisation and cost)

Four of 11 studies targeting patients reported process outcomes (Abdelhamid 2008; Ebid 2006; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009). In two studies, the rate of hospitalisation decreased statistically significantly in the intervention groups as compared to the control groups (Abdelhamid 2008; Petkova 2008). Effect sizes for health service utilisation were not reported in two studies (Abdelhamid 2008; Ebid 2006). The hospitalisation rate of asthmatic patients decreased by 15.7%; the 'need for visits to general practitioners (GP) less than two to three times' parameter increased by 19.2% and the 'need for visits to GPs greater than six times' parameter decreased by 4.6% (Petkova 2008). In arthritic patients, the 'no need of visit to GP' parameter increased by 16.3% and the 'need of visit to GP for more than six times' parameter decreased by 14% (Petkova 2009). Similarly, in another study the number of visits to private clinics (PCs) or outpatients clinics (OPCs) and emergency rooms of hospitals decreased in the intervention group in both asthmatic patients and patients suffering from COPD (Ebid 2006). Specific effect sizes were not reported. In the same study, medication costs for patients with COPD and asthma were also decreased.

Overall, pharmacist‐provided services were able to reduce health service utilisations such as GP visits and hospitalisation rate.

Comparison between interventions

The pharmacist interventions targeting patients were counselling and patient education; counselling with patient education plus an educational booklet; counselling and drug review; a pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up; counselling, booklet and special medication container; and counselling and special medication container (Table 3). For the blood glucose outcome, counselling and 'counselling plus a booklet plus medication container' were the most effective interventions as compared to other interventions such as 'counselling plus medication container' or 'counselling plus a booklet' (Suppapitiporn 2005). A pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up also showed an effective result (Arun 2008) for this outcome. For blood pressure, a pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up was more effective in Lugo 2007 as compared to Sookaneknun 2004. A pharmaceutical care plan also showed an effective result for the improvement of blood triglyceride and cholesterol levels (Paulos 2005). 'Counselling and booklet' (Petkova 2008) was more effective in improving peak expiratory flow rate as compared to 'counselling and drug review' (Abdelhamid 2008) among asthmatic patients. The effect of 'counselling plus a booklet' on arthritic patients was small but significant (Petkova 2009). The rate of hospitalisation decreased by 19.2% and GP visits decreased by 15.7% among asthmatic patients when assessing 'counselling and a booklet' (Petkova 2008). Similarly, 'counselling and a booklet' was assessed in Petkova 2009 and increased the 'no need to visit to GP' parameter by 16.3% and 'the need to visit a GP for more than six times' parameter by 14%. The single study assessing the effect of the pharmacist intervention on medication costs assessed an intervention of a pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up (Ebid 2006). The pharmaceutical care significantly reduced the medication costs in Ebid 2006. Most of the studies did not report effect sizes, hence it was not possible to compare the pharmacist interventions. Overall, counselling plus a booklet and a pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up were the most effective interventions.

Comparison 2(c): comparison of the delivery of healthcare professional targeted services by pharmacists versus usual care

One study that compared the effectiveness of a pharmacist intervention targeted at healthcare professionals versus usual care was included in this review (Zwarenstein 2007). A single pharmacist delivered outreach visits in this study and the improvement in the asthma symptom score due to the intervention was 0.85 with a P value of 0.03 (with little or no difference in symptoms at the lower end of the CI). A detailed description is presented in Analysis 1.1.

Quality of the evidence (GRADE analysis)

A Grade analysis was done to determine the quality of the evidence for the clinical outcomes, quality of life, health service utilisation and cost for comparisons 1(c) and 2(c) (Table 1; Table 2). There was a small improvement in clinical outcomes with the patient targeted pharmacist‐provided services as compared to usual care and the quality of the evidence was graded low. There were small improvements in the quality of life scores and the quality of evidence was graded low. The health service utilisation was also decreased for this comparison and the quality of evidence was graded low. Medication cost was also decreased by the pharmacist interventions and the quality of evidence was low. The study that targeted healthcare professionals comparing pharmacist provided services to usual care showed that the intervention decreased the asthma symptom score, however the quality of evidence was graded low.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The three studies that demonstrated little impact had small sample sizes (21 to 90), which may explain the lack of statistical significance (Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009). Five of 11 studies did not present data supporting statements about the outcomes thus making it difficult to estimate the magnitude of effect (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Paulos 2005). We tried to contact the authors, but none of them responded. Only a single study discussed the clinical importance of the intervention effect on the outcome (Zwarenstein 2007). Among the eligible studies, there was great heterogeneity in comparison groups, intervention type, outcomes assessed, duration of intervention, length of follow‐up and the measurement used for outcomes. An attempt was made to perform a meta‐analysis by subgrouping studies based on the disease state and outcome type. Unfortunately, there were insufficient data across the 12 included trials to perform subgroup analyses for any disease state. For example, in the two studies assessing disease control in adult asthmatic patients, studies used different quality of life questionnaires (Abdelhamid 2008; Petkova 2008). Due to the different outcome measures and measurement units, pooling data from these outcomes was not possible. As single studies assessed outcomes for hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and arthritis, meta‐analysis was not possible. Although three studies (Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Suppapitiporn 2005) assessed the effectiveness of the interventions on blood glucose, only one study (Suppapitiporn 2005) reported the pre‐intervention and post‐intervention value of the outcome and its standard deviation. Hence, meta‐analysis could not be performed. For similar reasons it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis for blood pressure‐related outcomes. Consequently, data were presented separately for each included study.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review has demonstrated that pharmacist interventions targeting patients may improve patient outcomes and health service utilisation in middle income countries. Pharmacist interventions targeting patients resulted in a small improvement of clinical outcomes. A small Improvement in quality of life was demonstrated in most of the studies although some studies did not report a measure of effect. Although few studies assessed process outcomes (health service utilisation and cost), health service utilisation such as the rate of hospitalisation and the need for general practitioner visits were also found to be reduced in all of the studies that reported these outcomes. Regarding cost, only medication costs were assessed in a single study and were found to be reduced (Ebid 2006). However, a number of studies did not report this outcome. None of the included studies specifically mentioned the clinical significance or beneficial effect, however clinical significance or beneficial effect can be deduced from the data.

Only one study examined pharmacist interventions targeting healthcare professionals and it found very small improvements in asthma symptom scores with little or no difference in symptoms at the lower end of the confidence interval. In addition, a single pharmacist delivered outreach visits to healthcare professionals in this study, which might preclude the generalisability of the result due to the pharmacist's personality and personal rapport with practices.

There was heterogeneity noted in the type of pharmacist interventions delivered and the outcome variables measured. However, 'counselling plus a booklet' and a pharmaceutical care plan with scheduled follow‐up showed mostly positive outcomes. Interventions differed by site of delivery (for example the outpatient department of hospitals, primary care clinic, community pharmacy), the length of each intervention session (for example 20 minute session with pharmacist, 50 minute session with pharmacist) and the frequency of the intervention (for example 11 sessions per 22 weeks, six sessions over six months).

The most common interventions provided involved simple patient education. Few studies assessed complete pharmaceutical care follow‐up, by providing medication therapy optimisation, monitoring of disease control, compliance assessment, identifying and resolving drug‐related problems and maintaining manual records for each patient. The terminology used for these services in the studies was ‘pharmaceutical care’, but this is likely to be similar to what is now called 'medication therapy management' (MTM). However, most of the pharmacist interventions targeting patients in other studies conducted in high income countries were complex and comprehensive; these services included MTM consisting of medication optimisation, monitoring of disease control, adverse drug reactions, identification of drug‐drug interactions, compliance assessment and patient education (Nkansah 2010). The only included study targeted towards healthcare professionals involved academic detailing and tools such as visual aids for improving diagnosis, prescribing and follow‐up. Pharmacist interventions targeting healthcare professionals in high income countries included oral or written recommendations to physicians regarding therapy modifications or resolution of medication‐related problems with multiple follow‐up visits with patients extending over several months, ranging from one month to 12 months (Nkansah 2010). In the studies conducted in high income countries, the duration of each intervention was longer, ranging from 14 to 120 minutes with one to 22 intervention events conducted over the longer study period that spanned from six weeks to 23 months, compared to low‐ and middle‐income countries. In the studies conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries, the duration of the intervention ranged from 20 to 50 minutes with three to 11 interventions conducted over a period of nine weeks to six months.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Studies which compared the effect of pharmacist‐provided non‐dispensing services targeted at patients and healthcare professionals with services delivered by other healthcare professionals or untrained workers could not be found. Thus, this review could not assess all of the listed objectives. Only 12 studies which compared pharmacist interventions versus usual care were included in this review. All eligible studies were from middle income countries. Hence, the result of this review is highly applicable to those types of countries. Unfortunately studies conducted in low income countries could not be found. Most of the excluded studies were before and after uncontrolled studies that had few points of measurement before and after the intervention. These studies were also conducted in middle income countries. Thus, there is a need to design and conduct higher quality studies in both low as well as middle income countries. Inclusion of high quality studies from a diverse range of countries would increase the external validity of this comparison.

Eleven of 12 studies included in this review examined pharmacist interventions targeting patients and the remaining one examined the effect on pharmacist interventions targeting healthcare professionals. Only four studies measured health service utilisation; a single study measured medication cost and all 12 studies assessed patient outcomes. Five studies did not report enough data to calculate an effect size for outcomes and instead only provided qualitative statements about results (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006; Paulos 2005). Some outcomes reported were subjective, however only objective outcomes were included in this study to reduce the risk of bias. Most of the studies enrolled small numbers of participants, that is less than 100 in number (Adepu 2007; Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Paulos 2005; Petkova 2008; Petkova 2009).

As noted above, the findings of this review are applicable to middle income countries. There are various reasons such as lack of resources; variation in the organisation of services, qualifications of pharmacists; and cultural barriers which might preclude the applicability of the results to low income countries. In addition to the pharmacist, there should be sufficient resources such as access to medicines or diagnostic tests in order to successfully implement pharmacist interventions. In addition, the qualifications of pharmacists might vary between low income countries and middle income countries, which can cause the results of pharmacist interventions to differ.

Quality of the evidence

A number of studies had some limitations in their methodological quality. Although most studies were blinded, many did not explicitly report methods to conceal allocation of participants to the intervention and control groups. Given the nature of practice‐based interventions, it is not always possible to blind patients or pharmacists. The impact of a lack of blinding was likely to be minimal as the outcome variables included in this review were objective (for example blood pressure measurement, validated quality of life questionnaire etc). Although most of the studies described the sequence generation as simple randomisation or computer generation, baseline values of variables other than the primary outcomes were not comparable between the intervention and control groups. This may be a consequence of small sample sizes rather than the method of randomisation. In a few studies, baseline measurement of primary outcomes was not reported. A single study met the protection against contamination criteria (Zwarenstein 2007). This is challenging to accomplish in studies conducted in low resource settings as most studies occur within one clinic setting or one healthcare practice group (with multiple health professionals).

Four studies did not explicitly report clinical importance for patient outcomes such as the blood pressure outcome and blood glucose level outcome or worthwhile effects on health service utilisation of the pharmacist interventions (Abdelhamid 2008; Adepu 2007; Arun 2008; Ebid 2006). Even if there are statistically significant changes in outcomes due to pharmacist interventions, mention of clinical importance or worthwhile effect could help the reader better interpret the implications of study results. Hence, ideally, clinical importance or worthwhile effects should be reported in the studies along with statistical significance for each outcome.

In summary, this review demonstrates that pharmacist interventions targeting patients can improve a number of clinical outcomes and health service utilisation, although the effect size was not always large or statistically significant. In some studies, due to the poor reporting of numerical values, the effect size and statistical significance for outcomes, the results were not interpretable. Meta‐analysis, which is performed by pooling data from multiple studies, might have helped in determining the true effect and magnitude of the pharmacist interventions. However, due to limitations in the data reported in studies and heterogeneity in the types of outcomes, clinical conditions and approaches to measurement of outcomes, a meta‐analysis could not be performed. Overall, the greatest limitation was the poor reporting of study results, such as no explicit reporting of means and standard deviations along with the exact value of statistical significance, which thus precluded the estimation of the strength of the effect. In addition, limitations in reporting of methodological components such as allocation concealment, sequence generation and follow‐up of patients and professionals impacted our ability to thoroughly assess study quality. Therefore, standardised outcome measures for various clinical conditions, proper reporting of outcome data and methodological improvements could help in assessing the impact of pharmacist interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings are consistent with the results of other reviews (Beney 2000; Nkansah 2010). All the reviews indicated that pharmacist interventions can lead to improved patient outcomes and health service utilisation for multiple disease states, although effect size may not always be substantial or statistically significant.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.