Abstract

The Early Jurassic angiosperm Nanjinganthus has triggered a heated debate among botanists, partially due to the fact that the enclosed ovules were visible to naked eyes only when the ovary is broken but not visible when the closed ovary is intact. Although traditional technologies cannot confirm the existence of ovules in a closed ovary, newly available Micro-CT can non-destructively reveal internal features of fossil plants. Here, we performed Micro-CT observations on three dimensionally preserved coalified compressions of Nanjinganthus. Our outcomes corroborate the conclusion given by Fu et al., namely, that Nanjinganthus is an Early Jurassic angiosperm.

Subject terms: Evolution, Plant sciences

Introduction

The discovery of the Early Jurassic angiosperm Nanjinganthus1 triggered a heated botanical debate among botanists2–6. When they claimed the existence of two or more ovules within an ovary of Nanjinganthus1,6, there was a dilemma for Fu et al.: in a single specimen of Nanjinganthus flower, the ovule is either visible when the ovary is broken or is invisible when the ovary is intact and closed, but no ovule is visible in an intact closed ovary, as traditional technologies do not allow to demonstrate both ovules and the intact enclosing ovary in a single specimen. Technically, if these two features (ovules and closed ovary) cannot be proven in a single specimen, the angiospermous affinity of Nanjinganthus remains speculative. This leaves Fu et al.1,6 vulnerable to criticism. The application of Micro-CT technology enables us to non-destructively reveal the internal features that are otherwise hard or impossible to show in fossil plants7. To expel this final doubt over Nanjinganthus, we performed Micro-CT observations on three-dimensionally preserved coalified compressions of Nanjinganthus. The outcomes corroborate the conclusion that Nanjinganthus is an Early Jurassic angiosperm.

Results

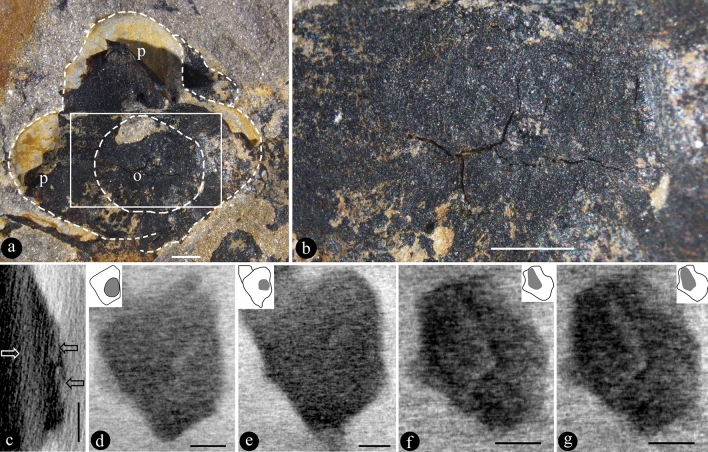

PB22279 is a coalified flower compressed top-down (Fig. 1a). The diameter of the flower is approximately 8.6 mm, while the diameter of the ovary is approximately 3.5 mm (Fig. 1a). The epigynous flower bears petals and sepals on the upper rim of the ovary (Fig. 1a). The original ovary roof is integral, sealing the ovary completely, and only vaguely visible in the Micro-CT virtual section of the flower (Fig. 1a–c). The ovules are eclipsed by the ovary roof (Fig. 1a,b). Micro-CT observation results exhibit that there are at least two ovules within the ovary (Fig. 1c–g). The ovules vary in size, form, and orientation (Fig. 1c–g). One ovule is oval, 2.22 × 1.95 mm (Fig. 1d,e), while the other ovule is truncate-cuneate, 2.0 × 1.24 mm (Fig. 1f,g). The ovules are 0.22 to 0.27 mm in thickness (Fig. 1c). The order of occurrence of ovules, ovary, and petals in a video agreed with that the flower is epigynous (Supplementary Video V1, V2).

Figure 1.

Nanjinganthus dendrostyla and its ovules within the ovary. PB22279. All scale bar = 1 mm. (a) Top-down view of the coalified compression, with an ovary (o) in the centre and one of the petals (p) peeling off from the sediments. The outlines of petals and ovary are marked with broken lines. Reproduced from Fu et al.6. (b) Integral ovary roof, with cracks due to preservation. (c–g) are micro-CT virtual sections. Reproduced from Fu et al.6. (c) Vertical section showing two ovules (black arrows) covered by the ovary roof (white arrow). (d,e) Two transverse sections showing one oval ovule within the ovary, refer to the inset, in which an ovule is grey in colour. (f,g) Two transverse sections showing another truncate-cuneate ovule in the ovary, refer to the inset, in which an ovule is grey in color.

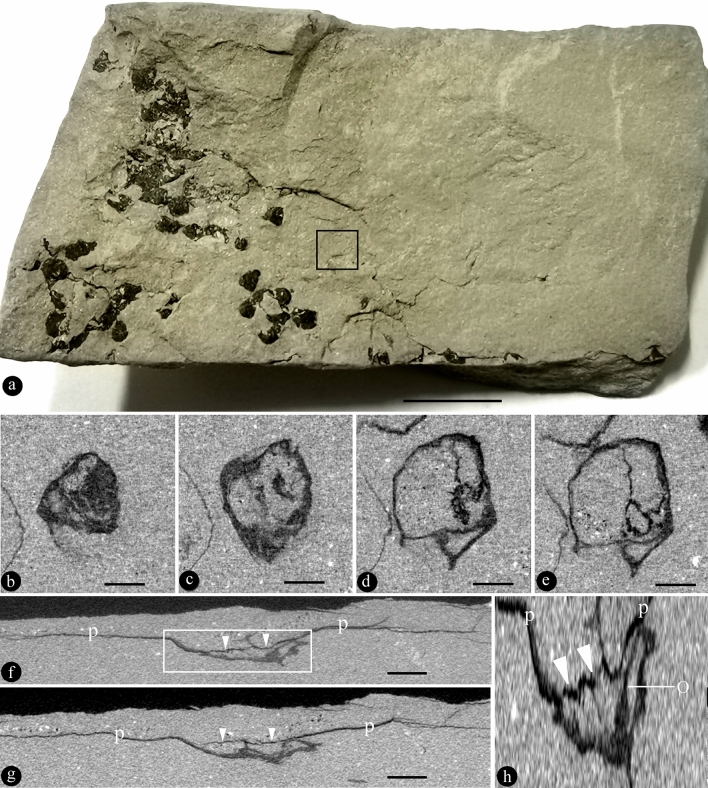

PB180516 has multiple coalified flowers cumulated in the sediment (Fig. 2a). The flower focused on in this study is fully embedded in the sediment and thus invisible to naked eyes (Fig. 2b–h). The flower is preserved three-dimensionally, with an ovary including bowl-formed basal part and an ovary roof (Fig. 2b–h). The diameter of the ovary is 2.5–3.4 mm. On the top of the ovary is a thin layered ovary roof sealing the ovary, and around the ovary are petals (Fig. 2f–h). At least two ovules are recognizable within the ovary (Fig. 2b–h). In a virtual vertical section, an ovule can be seen attached to the side wall of the ovary through a funiculus (Figs. 2f,h, 4; Supplementary Video V3, V4).

Figure 2.

Nanjinganthus dendrostyla and its ovules within the ovary. PB180516. All scale bars = 1 mm, except annotated. (a) Several coalified compressions embedded in siltstone. Scale bar = 1 cm. (b–e) Virtual cross sections, in an ascending order, of the ovary of a flower fully embedded (invisible, in the rectangle in a) in the specimen shown in (a). (f,g) Two virtual vertical sections of the flower shown in (b–e), showing an ovary with an ovary roof (triangles) and petals (p). (h) A detailed view of the rectangular region in (f), showing a funipendulous ovule (o) attached to the inner wall of the ovary that has a roof (triangles) and petals (p). To make it easy to observe, the figure is vertically stretched by 700%.

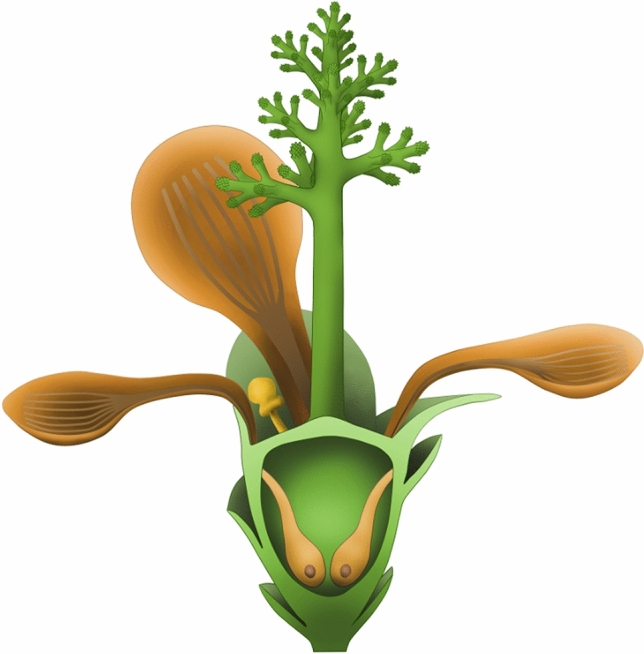

Figure 4.

Updated reconstruction of Nanjinganthus dendrostyla. Note that the configuration of the ovule is slightly modified according to the new information revealed by Micro-CT.

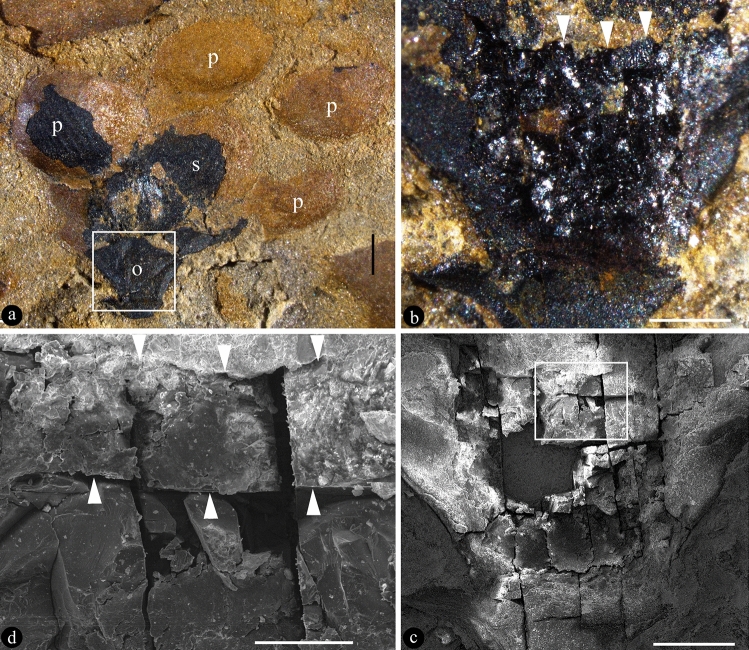

PB22281 is a laterally compressed coalified flower embedded in the sediment (Fig. 3a). Through dégagement, the peripheral portion of the ovary in foreground is removed, exposing the details near the ovary roof (Fig. 3b–d). The ovary roof is some flatly domed, making the ovary secluded (Fig. 3b–d). The ovary roof has smooth outer and inner surfaces, 122 μm thick, across the top of the ovary (Fig. 3b–d). The absence of sediment in the ovary suggests that the ovary is completely closed by the ovary roof (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Nanjinganthus dendrostyla. PB22281. (a) A coalified laterally compressed flower with ovary (o), sepal (s), and petals (p), embedded in siltstone. Reproduced from Fu et al.1. Scale bar = 1 mm. (b) Detailed view of the basal portion of the flower shown in (a), showing clear border (triangles) between the sediment and ovary roof, exposed through dégagement. Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (c) SEM view of the portion shown in (b). Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (d) Detailed view of the rectangular region in (c), showing the ovary roof (between triangles) secluding the ovary from the exterior. Scale bar = 0.1 mm.

Discussions

It is obvious that Nanjinganthus is a reproductive organ, not a vegetative organ. Among all known reproductive organs, there are microspores, sporangia sensu stricto, and accessary foliar structures (e.g., bracts, sepals, petals, and involucrum). The ovules in the ovary of Nanjinganthus are of millimetric dimensions, 2.22 × 1.95 mm and 2.0 × 1.24 mm, and three dimensional (Fig. 1d–g). The forms and dimensions of these ovules and their connection to the ovary wall by a funiculus (Figs. 2f,h, 4) distinguish them from all accessory foliar structures frequently seen in reproductive organs. The dimensions of the ovules are much bigger than those of a microspore, which are usually not greater than 0.2 mm in any dimension. Sporangia sensu stricto are rarely known completely enclosed in a structure in any plants, with rare exceptions in Marsilea (which is morphologically distinct from Nanjinganthus, however). In contrast, the ovules in Nanjinganthus are enclosed, eliminating the possibility of these ovules being sporangia sensu stricto. These comparisons exclude microspore, sporangia, and accessory foliar structures from our consideration, leaving only two alternatives, an ovule/megaspore. The occurrence of a funiculus (the connection to the ovary wall) of the ovule (Fig. 2f, h) excludes megaspores from further consideration, as a megaspore (at least a mature one) is not connected to a mother plant. The variation of ovule forms seen in a single ovary of Nanjinganthus implies that the ovules may be asynchronous in development, a phenomenon frequently seen in extant angiosperms8.

The lack of consensus on the criterion for identifying fossil angiosperms has caused controversies in the study of early angiosperms. For example, Herendeen et al.9, Sokoloff et al.2, and Bateman4 have advanced mutually conflicting criteria for fossil angiosperms: Herendeen et al.9 put several characters as “unique angiosperm features”, Sokoloff et al.2 appeared to focus on pentamery of flowers, while Bateman4 preferred double fertilization and closed carpel. It became especially embarrassing when a reader finds that Bateman is a member of Sokoloff et al. and these two conflicting publications2,4 were online almost at the same time. Interestingly, either of these three criteria, if adopted, would annihilate almost all fossil angiosperms (including those published by the authors themselves), implying their inapplicability6. After a systematic survey of pollination in conifers, Tomlinson and Takaso10 found that some conifers do seclude their seeds (although such a seclusion occurs only after pollination), therefore “angiospermy” is not a feature unique of angiosperms, instead “ovules enclosed before pollination” draws a clear demarcation between gymnosperms and angiosperms. This criterion was adopted by Fu et al.1,6 and thus applied to determine that Nanjinganthus was an early angiosperm.

In surface view, the ovary roof is intact and integral in PB22279 (Fig. 1a,b), suggesting a closed ovary. Although obvious to naked eyes, the ovary roof in PB22279 is only vaguely observed in Micro-CT rendering. Similarly, ovary roof is seen as a thin seam in PB180516. This may be attributed to the top-down compression during the fossilization and the flowers in both specimens are similarly oriented and compressed. This explanation becomes more plausible when a laterally compressed flower is observed. As seen in Fig. 3a–d, the thickness of the ovary roof in PB22281 is less affected by the lateral compression during fossilization. Therefore, we can measure the thickness of the ovary roof, which is much thicker and more conspicuous than in PB22279 and PB180516. Although there are cracks in the ovary roof (Figs. 1b, 3c,d), these cracks can be attributed to artefacts from desiccation. The lack of sediments in the ovary (Fig. 3b) favours the integrity of the ovary roof. Taking all together, it is reasonable to say that the original ovary roof of Nanjinganthus is integral, and it secludes the ovary completely from the exterior.

Although Fu et al.1,6 demonstrated that the ovules were in the ovary in Nanjinganthus and they applied an over-strict criterion of angiosperms (it may lead some botanists to incorrectly place some angiosperms into gymnosperms), their argument is imperfect: (1) their conclusion was based on a comparison among over two hundred specimens, and (2) the ovules were demonstrated only in broken ovaries1. There is thus a paradox about Nanjinganthus: any ovules demonstrated are in broken ovaries, and no ovule is shown inside an intact ovary, then no one knows whether there really are ovules in an intact ovary of Nanjinganthus, since ovules and closed ovary, as two features, have never been demonstrated in the same specimen of Nanjinganthus hitherto. Thanks to the inventive Micro-CT technology, we can now demonstrate both these features (ovules and closed ovary) in PB22279 (Fig. 1a–g) and PB180516 (Fig. 2a–h), expelling this last doubt over Nanjinganthus. The in-ovary position of the ovules (Figs. 1d–g) suggests that angio-ovuly occurs in Nanjinganthus, satisfying the above over-strict criterion for angiosperms.

The early age (Early Jurassic) of Nanjinganthus is in line with increasing other fossil evidence11–20 as well as molecular studies and phylogenetic analyses21–27 suggesting an earlier origin of angiosperms (in the Jurassic and even the Triassic). It is time to update our knowledge about the early history of angiosperms.

STAR methods

The materials studied here include two specimens that have been published previously in Fu et al.1,6 as well as one new specimen (Fig. 2). These specimens are from the same locality and the information of fossil locality, stratigraphy, and age is available in Fu et al. (2018). Details of the fossils were observed and photographed using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope equipped with a Digital Sight DS-Fi1 camera. Two specimens (PB22279, PB180516) were scanned using a GE v|tome|x m300&180 micro-computed-tomography scanner (GE Measurement & Control Solutions, Wunstorf, Germany), housed at the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. The data set has a resolution of 23.298 µm and the scan was carried out at 120 kV and 150 µA. One frame per projection was acquired by a timing of 2000 ms for a total of 2500 projections. One specimen (PB22281) was observed using a MAIA3 TESCAN SEM housed at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Nanjing, China. All images were recorded in TIFF or JPEG format, the videos were saved in avi format, all figures organized together using a Photoshop 7.0 for publication.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB26000000) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (42288201, 41688103, 91514302). We thank Mr. Yan Fang for his help with SEM observation. This is dedicated to the 90th birthday of Prof. Dr. Zhiyan Zhou.

Author contributions

Q.F., conceptualization, resources, writing; Y.H., P.Y., data acquiring and curation, writing; J.B.D., M.G.Á., writing, reviewing; M.P., writing, reviewing; X.W., conceptualization, resources, writing—original draft.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-27334-0.

References

- 1.Fu Q, et al. An unexpected noncarpellate epigynous flower from the Jurassic of China. Elife. 2018;7:e38827. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, El ES, Rudall PJ, Bateman RM. Supposed Jurassic angiosperms lack pentamery, an important angiosperm-specific feature. New Phytol. 2020;228:420–426. doi: 10.1111/nph.15974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coiro M, Doyle JA, Hilton J. How deep is the conflict between molecular and fossil evidence on the age of angiosperms? New Phytol. 2019;223:83–99. doi: 10.1111/nph.15708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman RM. Hunting the snark: The flawed search for mythical Jurassic angiosperms. J. Exp. Bot. 2020;71:22–35. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DW, Li H. Paleobotany: Did flowering plants exist in the Jurassic period? Elife. 2018;7:e43421. doi: 10.7554/eLife.43421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Q, Diez JB, Pole M, García-Ávila M, Wang X. Nanjinganthus is an angiosperm, isn't it? China Geol. 2020;3:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X, Feng M. Micro-CT Technology and its Applications in Plants. Science Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endress PK. Angiosperm ovules: Diversity, development, evolution. Ann. Bot. 2011;107:1465–1489. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herendeen PS, Friis EM, Pedersen KR, Crane PR. Palaeobotanical redux: Revisiting the age of the angiosperms. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17015. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomlinson PB, Takaso T. Seed cone structure in conifers in relation to development and pollination: A biological approach. Can. J. Bot. 2002;80:1250–1273. doi: 10.1139/b02-112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Duan S, Geng B, Cui J, Yang Y. Schmeissneria: A missing link to angiosperms? BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X. Schmeissneria: An angiosperm from the Early Jurassic. J. Syst. Evol. 2010;48:326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2010.00090.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad V, et al. Late cretaceous origin of the rice tribe provides evidence for early diversification in Poaceae. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:480. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z-J, Wang X. A perfect flower from the Jurassic of China. Hist. Biol. 2016;28:707–719. doi: 10.1080/08912963.2015.1020423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X. The Dawn Angiosperms. Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, You H-L, Li X-Q. Dinosaur-associated poaceae epidermis and phytoliths from the early cretaceous of China. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018;5:721–727. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwx145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochuli PA, Feist-Burkhardt S. A boreal early cradle of angiosperms? Angiosperm-like pollen from the middle triassic of the Barents Sea (Norway) J. Micropalaeontol. 2004;23:97–104. doi: 10.1144/jm.23.2.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochuli PA, Feist-Burkhardt S. Angiosperm-like pollen and Afropollis from the middle triassic (Anisian) of the Germanic Basin (Northern Switzerland) Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:344. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos AA, Wang X. Pre-carpels from the middle triassic of Spain. Plants. 2022;11:2833. doi: 10.3390/plants11212833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X. On the origin of outer integument. China Geol. 2022;5:777–778. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Z-Y, Lu A-M, Tang Y-C, Chen Z-D, Li D-Z. The Families and Genera of Angiosperms in China. A comprehensive analysis. Science Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu A-M, Tang Y-C. Consideration on some viewpoints in researches of the origin of angiosperms. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 2005;43:420–430. doi: 10.1360/aps050019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soltis DE, Bell CD, Kim S, Soltis PS. Origin and early evolution of angiosperms. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2008;1133:3–25. doi: 10.1196/annals.1438.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilu, K. in 8th European Palaeobotany-Palynology Conference 117 (Budapest), (2010).

- 25.Smith SA, Beaulieu JM, Donoghue MJ. An uncorrelated relaxed-clock analysis suggests an earlier origin for flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5897–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H-T, et al. Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat. Plants. 2019;5:461–470. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silvestro D, et al. Fossil data support a pre-cretaceous origin of flowering plants. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021;5:449–457. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-01387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.