Abstract

Accurate measurements of the oxygen concentration in liquid lead-bismuth eutectic (LBE) alloys are essential for ensuring optimum cooling conditions in heavy liquid metal coolant fast reactors. However, while unavoidable variations in the Bi contents of these alloys can affect the accuracy of these measurements, this issue has not yet been rigorously evaluated. The present work addresses this issue by evaluating variations in oxygen concentration measurements obtained experimentally for oxygen-saturated liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents at different temperatures using a solid electrolyte oxygen sensor. Theoretical relationships are established between sensor voltage, oxygen concentration, temperature, and Bi content under the applied experimental conditions, and excellent agreement is obtained between the experimental and theoretical results. The theoretical relationships establish that the voltage decreases by about 1 mV for every 1 wt% increase in Bi content at a temperature of 400 °C. At a fixed voltage, with the increase of T, the influence of the Bi content on the CO calculation results gradually increased. Finally, the impact of varying Bi contents on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements is evaluated under practical reactor operation conditions, and higher requirements for the control of dissolved oxygen in LBE-cooled fast reactors are proposed.

Keywords: Pb–Bi alloys, Oxygen concentration, Oxygen control, Oxygen sensor, LFR

Pb–Bi alloys; Oxygen concentration; Oxygen control; Oxygen sensor; LFR.

1. Introduction

Liquid lead-bismuth eutectic (LBE) alloys are one of the more promising coolants employed in heavy liquid metal coolant fast reactors and accelerator drive systems (ADSs) [1, 2]. However, lead alloys are highly corrosive to structural steel according to a physical or physicochemical process that can substantially shorten the useful life of these systems. Nonetheless, an appropriate concentration of oxygen in the liquid lead-bismuth alloy can induce the formation of a dense oxide film on the surfaces of steel components that can greatly inhibit this corrosion. Conversely, this protective mechanism becomes negligible when the oxygen concentration is too low due to insufficient oxide layer formation, while an overly high oxygen concentration will lead to coolant oxidation, which will detract from the cooling performance of the liquid, and again shorten the useful life of reactors and ADSs [3, 4]. Therefore, the accurate measurement of oxygen concentration in liquid lead-bismuth alloys is essential for optimizing the cooling and protective film formation performances of these liquid metal systems.

The solid electrolyte oxygen sensors employed for measuring the dissolved oxygen concentration in liquid LBE alloys typically apply a yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) electrolyte owing to its high oxygen ion conductivity. Real-time measurements are obtained according to the oxygen potential difference measured between the liquid lead-bismuth alloy and a reference electrode. Typical reference electrodes currently employed for this purpose include gas reference systems, such as those employing platinum (Pt/air), lanthanum strontium manganite (LSM) (LSM/air), and lanthanum strontium cobalt ferrite (LSCF) (LSCF/air), and metal/metal oxide reference systems, such as Bi/Bi2O3, In/In2O3, and Cu/Cu2O [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. In addition, a number of studies have greatly extended oxygen sensor technology by investigating issues involving the materials, calibration, and drift behavior of oxygen sensors [10, 11, 12]. Of particular note here is that compositional changes in LBE alloys may affect the output signal of oxygen sensors. Nonetheless, current studies typically assume that LBE alloys consistently maintain a standard stoichiometry of 44.5 wt% Pb and 55.5 wt% Bi over the course of measurements. However, this is not the case in practical applications due to variations in the manufacturing process and changes in the working conditions. An example reflecting variations in the manufacturing process can be observed for a lead-bismuth alloy sample supplied by Metaleurop S.A., which was demonstrated to have a Bi content of 57.3 ± 2.0 wt%, which deviates by as much as 3.8 wt% from the standard Bi content of 55.5 wt% [13]. While manufacturers of LBE alloys in China have significantly reduced the compositional variation of these alloys, the Bi content still varies by ±2 wt%. In addition, the composition of liquid LBE alloys varies under practical working conditions due to the evaporation or oxidation of Pb. Therefore, this issue could have potentially serious effects on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements. However, to the best of authors' knowledge, the extent to which changes in the relative Bi concentration of liquid LBE alloys affect the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements has not been rigorously evaluated.

The present work addresses this issue by evaluating variations in oxygen concentration measurements obtained experimentally for oxygen-saturated liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents at various temperatures. Here, we employ a ceramic/air reference system based on LSCF and gadolinium-doped ceria (GDC) (LSCF-GDC/air) owing to its excellent low temperature performance. In addition, we compare the test results with previously published experimental results. Theoretical relationships are established between sensor voltage, oxygen concentration, temperature, and Bi content under the applied experimental conditions, and excellent agreement is obtained between the experimental and theoretical results. Accordingly, these relationships facilitate a rigorous accounting of the influence of Bi content on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements. Finally, the impact of varying Bi contents on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements is evaluated under practical reactor operation conditions, and higher requirements for the control of dissolved oxygen in LBE-cooled fast reactors are proposed. Accordingly, the present work provides technical support for the development of oxygen sensors for the use in liquid LBE alloy coolant environments.

2. Experimental

2.1. Oxygen sensor

A schematic and image of the LSCF-GDC/air sensor employed in this study are given in Figure 1. The oxygen sensor adopted a short ceramic thimble of yttria partially stabilized zirconia (YPSZ) with high mechanical stability serving as the solid electrolyte and a composite LSCF-GDC cathode material serving as the LSCF-GDC/air reference system. The commercial LSCF-GDC composite powder was applied into the YPSZ thimble. An SS304 stainless steel (SS) lead wire was connected between the BNC connector and the cathode.

Figure 1.

Schematic (left) and image (right) of the LSCF-GDC/air oxygen sensor employed in this study.

2.2. Experimental apparatus

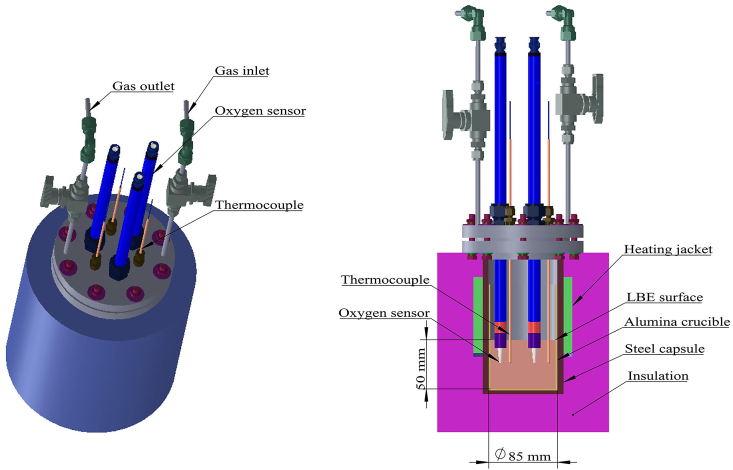

The experimental apparatus employed in the measurements and a schematic of its cross section are presented in Figure 2a and b, respectively. All tests employed 3.5 kg of a liquid LBE alloy residing within an alumina crucible enclosed in a sealed capsule. Gas inlets and outlets enabled the introduction of a mixed purging gas of high-purity argon with 5 vol% molecular H2 (Ar+5%H2), high-purity Ar alone, or air at a controlled rate of flow above the liquid metal surface. The crucible was externally heated, and the temperature was monitored and controlled via three K-type thermocouples residing within the liquid LBE alloy to provide high-accuracy temperature measurements. The thermocouples included a protective sleeve composed of 316L SS material Each oxygen sensor was inserted into the liquid metal to a depth of about 50 mm below the liquid surface to ensure that the entire short needle-shaped ceramic head was lying below the liquid level. The thermocouples were inserted to the same depth as well. In addition, the thermocouples and sensors were installed at the same radius with respect to the vertical centerline of the crucible, and the horizontal distance between the thermocouples and sensors was about 2 mm. This ensured that the measured temperature was as close as possible to the actual temperature at the tip of the oxygen sensor, which is required for obtaining accurate measurements under the saturated oxygen concentration condition.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental apparatus employed in the measurements and (b) a schematic of its cross section.

The present study employed five different Bi contents of 50.27 wt%, 53.92 wt%, 55.43 wt%, 56.44 wt%, and 60.16 wt%, which were all verified by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analysis with a measurement accuracy of ±1 ppm. The alloys (provided by Chalco Zhengzhou Nonferrous Metals Research Institute) were produced by a vacuum smelting method, where fluctuations in the Bi content were controlled within ±1%, and the concentrations of all impurities, such as Cr, Ag, Cu, As, Sb, Sn, Zn, Fe, Cd, Ni, Al, Mg, Hg, Te, Si, Co, and Mo, were less than 10 ppm. The total impurity content was less than or equal to 50 ppm. The Bi content of each alloy sample was then measured at the upper, middle, and lower positions by ICP-AES, and the measurement accuracy of Bi content mass fraction is ±0.3%. In the static experimental tank, only a single oxygen sensor was installed for each lead-bismuth alloy sample, but three K-type thermocouples were installed along the same circumference and uniform horizontal position of the oxygen sensor. The accuracy of the measurement results was ensured to the greatest extent possible by employing the same experimental device and oxygen sensor for all LBE alloy samples with different Bi contents, while different alumina crucibles were employed for each sample.

2.3. Experimental procedure

The same experimental procedure was employed for measuring the oxygen concentrations of all liquid LBE alloy samples with different Bi contents. The electromotive force (EMF) of the oxygen sensor was measured every 10 s using an Agilent DAQ970A data acquisition system with a high input resistance (>10 GΩ). First, a 3.5 kg sample of the LBE alloy of interest was introduced into the crucible, and the capsule was closed and heated at a rate of 2 °C/min to a temperature of 200 °C under purging with a mixed Ar+5%H2 gas flowing at 50 sccm until a liquid was obtained. Then, the sensors and thermocouples were inserted into the liquid metal, and the enclosed capsule was again heated at a rate of 2 °C/min to 600 °C, while still purging with Ar+5%H2 flow at 50 sccm. The capsule was maintained at a temperature of 600 °C for a relatively short period of time. Meanwhile, air was introduced into the capsule at a carefully controlled flow rate (typically 20sccm) that maintained a stable oxygen sensor signal. Accordingly, the liquid LBE alloy state remained in the vicinity of oxygen saturation. Once stable thermal and oxygen concentration conditions had been obtained, the inflowing gas was switched to high-purity argon at a flow rate of 50 sccm, and the temperature of the capsule was allowed to cool at a constant rate of −0.1 °C/min down to 400 °C. Throughout the cooling process, the oxygen sensor output voltage was compared to the zero-current potential corresponding to the Pb/PbO equilibrium (EPb/PbO) calculated at the instantaneous temperature of the liquid metal.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Oxygen sensor voltage in molten Pb–Bi alloys

Prior to presenting the experimental results, we first establish the expected oxygen sensor voltage theoretically under the applied experimental conditions in terms of the temperature of the molten metal (T), the partial pressure of oxygen on the reference electrode (Pr), and the electron transfer number (n) of the reaction. In addition, we assume static conditions, where the Bi content remains constant over the period of testing. Based on the Nernst equation, the theoretical electromotive force (Eth) can be given as follows [14]:

| (1) |

where R is the gas constant, F is the Faraday constant, and is the partial pressure of oxygen in the liquid LBE alloy. For the composite ceramic/air reference system, the value of Pr can be given as Pr = 0.21P0, where P0 is standard atmospheric pressure (i.e., 1 bar). Therefore, Eth can be given as

| (2) |

Therefore, we can determine the oxygen sensor voltage theoretically if the value of can be calculated independently.

The value of is established according to the thermodynamic equilibrium of PbO, which is considered to be the most stable oxide in the liquid LBE alloy system. Under oxygen saturation conditions, the Pb, PbO, and free oxygen constituents in the melt form the following chemical equilibrium:

It can be seen from this reaction that the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the liquid LBE alloy is limited by the formation of PbO. However, liquid LBE alloys form a non-ideal solution. Therefore, the excess Gibbs free energy () after mixing is provided by Gokcen et al. [15] as follows:

| (3) |

where is the molar fraction of Bi in the LBE melt. The relationship between the activity coefficient of Pb in liquid LBE alloys, , and T is given as follows [16]:

| (4) |

According to the definition of activity (aPb) as the product of and the molar fraction of Pb (xPb) in the melt, and Eqs. (3) and (4) above, the relationship between , , and T in a liquid LBE alloy can be obtained as follows.

| (5) |

In terms of the balance between Pb and PbO, we note that the standard molar formation energy of PbO in equilibrium can be defined as

| (6) |

In addition, the value of can be related exclusively to T as follows [17]:

| (7) |

Due to the low solubility of PbO in liquid LBE alloys, PbO will precipitate first under saturated oxygen conditions. Therefore, = 1, and Eqs. (5), (6), and (7) can be combined to obtain the following relationship between and under saturated conditions.

| (8) |

Finally, combining Eqs. (2) and (8) yields the following theoretical formula for calculating the oxygen sensor voltage under oxygen saturation conditions as a function of and T only.

| (9) |

An analysis of Eq. (9) indicates that this formula can be greatly simplified according to the following form:

| (10) |

where the first terms involving on the right hand side of Eq. (9) have been combined into a single constant b, and the terms modifying T have been combined into a single coefficient k. The Bi contents of the various LBE alloy samples tested, and the values of k and b calculated based on Eq. (9) and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bismuth contents, and temperature coefficients (k) and constants (b) calculated based on Eq. (9) at oxygen saturation voltage Eth.

| Sample | Bi content (wt%) | Bi content (mol%) | Temperature coefficient (k) | Constant (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50.27 | 50.06 | −5.810 × 10−4 | 1.129 |

| 2 | 53.92 | 53.71 | −5.843 × 10−4 | 1.128 |

| 3 | 55.43 | 55.22 | −5.858 × 10−4 | 1.128 |

| 4 | 56.44 | 56.23 | −5.868 × 10−4 | 1.127 |

| 5 | 60.16 | 59.95 | −5.908 × 10−4 | 1.126 |

The oxygen sensor voltages obtained experimentally and theoretically for liquid LBE alloy samples with different Bi contents under oxygen-saturated conditions and high input resistance (>10 GΩ) in the temperature range of 600 °C to about 400 °C are presented in Figure 3 as a function of time. In addition, the temperature and percent deviation between the experimental and theoretical voltages are also plotted with respect to time. The predicted linearity of the results is clearly evident, and the deviations between the experimental and theoretical voltages are generally less than ±0.1%, except in the very early stage of testing when the balance associated with may have not fully reached equilibrium. Accordingly, the theoretical values obtained using Eq. (9) can be employed to analyze a full range of temperature and Bi content conditions not available in the experimental results.

Figure 3.

Oxygen sensor voltages obtained experimentally as a function of time for liquid LBE alloy samples with various Bi contents under oxygen-saturated conditions in the temperature range of 600 °C to about 400 °C with an LSCF-GDC/air reference electrode and the corresponding theoretical values calculated based on Eq. (9) as a function of temperature. In addition, the temperature and percent deviation between the experimental and theoretical voltages are also plotted with respect to time.

A number of studies have established the relationship given in Eq. (10) between the theoretical oxygen sensor voltage and the temperature of a liquid LBE alloy in the standard eutectic state under saturated oxygen concentration and PbO equilibrium conditions. Of the samples employed the present study, the Bi content of 55.43 wt% is the closest to the standard eutectic state. Therefore, the values of the temperature coefficient k and constant b for a Bi content of 55.43 wt% were obtained by fitting to the experimental values recorded in Figure 3 according to Eq. (10). The plot of Eth = kT + b obtained by fitting to the experimental results is presented in Figure 4 along with corresponding plots based on theoretical values of k and b obtained in past studies for liquid LBE alloys in the standard eutectic state under oxygen-saturated conditions. The results given here are generally in quite good agreement. In addition, compared with the theoretical values in Table 1, it can also be well matched. Therefore, the oxygen sensor output voltages recorded herein can be expected to be accurate.

Figure 4.

Plot of (Eth = kT + b) obtained by fitting to the experimental values recorded for a Bi content of 55.43 wt% in Figure 3 according to Eq. (10), along with corresponding plots based on theoretical temperature coefficient (k) and constant (b) values obtained in past studies for liquid LBE alloys in the standard eutectic state under oxygen-saturated conditions.

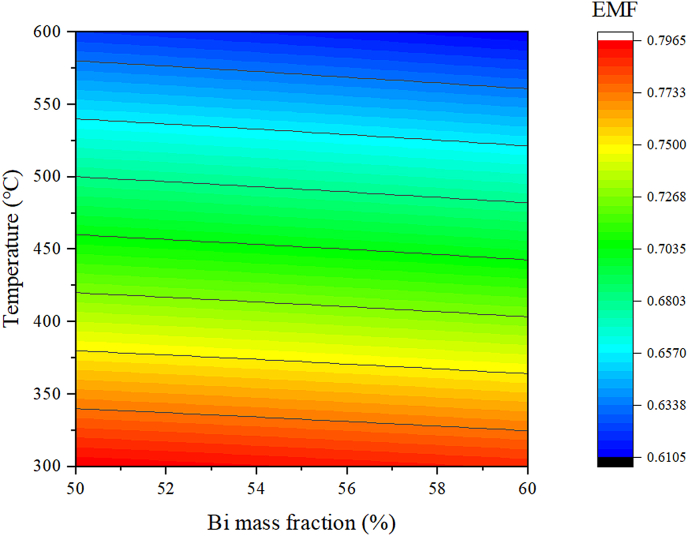

The impact of Bi content on the oxygen sensor voltage can be evaluated according to the values of Eth calculated at T = 400 °C based on Eq. (9) that are plotted in Figure 5 as a function of Bi mass fraction. The further impact of both Bi content and temperature is established by plotting the calculated values of Eth as functions of both T and Bi mass fraction in Figure 6. The results in Figure 5 indicate that Eth decreases from 0.7382 V to 0.7284 V with increasing Bi content from 50.27 wt% to 60.16 wt%. Accordingly, Eth decreases by about 1 mV for every 1 wt% increase in Bi content, which may have a substantial effect on the accuracy of the oxygen concentration measurements. This decrease in Eth with increasing Bi content arises because the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the liquid LBE alloy is limited by the formation of PbO, and changes in the Bi content alter the Pb activity and oxygen partial pressure, which in turn affect the value of Eth [16]. This decrease in Eth with increasing Bi content is further reflected by the black equipotential lines shown in Figure 5. However, we can also see that Eth gradually decreases with increasing temperature as well, which is due to the increasing solubility of oxygen in the liquid LBE alloy with increasing temperature.

Figure 5.

Calculated values of Eth as functions of both T and Bi mass fraction, where the black lines are lines of constant voltage that vary according to both T and Bi content.

Figure 6.

Values of Eth calculated at T = 400 °C based on Eq. (9) as a function of Bi mass fraction.

The results in Figures 5 and 6 clarify why the composition of liquid LBE alloys should be regularly monitored to ensure the accuracy of the obtained oxygen sensor signal voltage.

3.2. Calculation of oxygen concentration in molten Pb–Bi alloys with different Bi contents

Atomic oxygen is assumed to be dissolved in the molten LBE alloys, and the dissolved oxygen is therefore assumed to obey Henry's and Sievert's laws up to the solubility limit. Therefore, and the saturated oxygen partial pressure satisfy the following relationship with the oxygen concentration (wt%) and saturated oxygen concentration [16]:

| (11) |

The value of can be obtained for saturated oxygen concentrations in liquid LBE alloys with different compositions according to the following equation provided by Müller et al. [18].

| (12) |

Here, is the standard molar formation energy of Bi2O3, which can be determined by the following equation [17]:

| (13) |

Then, is obtained by combining Eqs. (7), (12), and (13) as follows.

| (14) |

The relationship between and can be obtained by combining Eqs. (8), (11), and (14) as follows.

| (15) |

Then, the following relationship for valid in the temperature range of can be obtained.

| (16) |

Finally, the relationship between , E, and T can be defined as

| (17) |

which identifies the relevant oxygen concentration constants K1 and temperature coefficients K2 for liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents.

The fitted values of K1 and K2 for the liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents are listed in Table 2. These values can now be employed in conjunction with Eq. (16) to determine the oxygen concentration in liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents as a function of T and E. The values of CO (wt%) obtained for E = 0.8185 V are plotted in Figure 7 as functions of both the Bi content and T. In addition, a color scale is provided for CO to better illustrate the observed trends. Here, a value of E = 0.8185 V corresponds to conditions of CO = 1 × 10−6 wt% at T = 400 °C in liquid LBE alloy. It can be seen from the figure that CO increases with increasing T, and decreases with increasing Bi content. For example, at T = 200 °C, a voltage of 0.8185 V corresponds to CO = 1.78 × 10−7 wt% for a Bi content of 50.27 wt%, and CO = 5.52 × 10−8 wt% for a Bi content of 60.16 wt%, which represents a difference of 1.23 × 10−7 wt%. At T = 600 °C, the corresponding CO values are 4.87 × 10−6 wt% and 2.64 × 10−6 wt%, respectively, which represents a difference of 2.23 × 10−6 wt%. The influence of Bi content changes on the calculation results of CO increases gradually with the increase of T. At 400 °C, the calculated results of oxygen concentration in lead-bismuth alloys with Bi contents of 50.27 wt% and 60.16 are 1.52 × 10−6 wt% and 6.78 × 10−7 wt%, respectively, which means that every 1 wt% change in Bi content will lead to a deviation of about 5.5% in the oxygen concentration. These results demonstrate that the effect of Bi content on oxygen concentration measurements cannot be neglected.

Table 2.

Mass fraction and mole fraction of Bi, temperature coefficient, and temperature-independent term of oxygen concentration calculation equation in five liquid lead-bismuth alloys with different Bi contents calculated based on Eq. (17).

| Serial number | Bi mass fraction (%) | Bi mole fraction (%) | Temperature independent term K1 | Temperature coefficient term K2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50.27 | 50.06 | −8.32 | 15581 |

| 2 | 53.92 | 53.71 | −8.30 | 15370 |

| 3 | 55.43 | 55.22 | −8.29 | 15281 |

| 4 | 56.44 | 56.23 | −8.28 | 15222 |

| 5 | 60.16 | 59.95 | −8.27 | 15004 |

Figure 7.

Calculated oxygen concentration plotted with respect to Bi content and temperature at Eth = 0.84 V.

3.3. Influence of Bi content in Pb–Bi melts on the control range of oxygen concentration

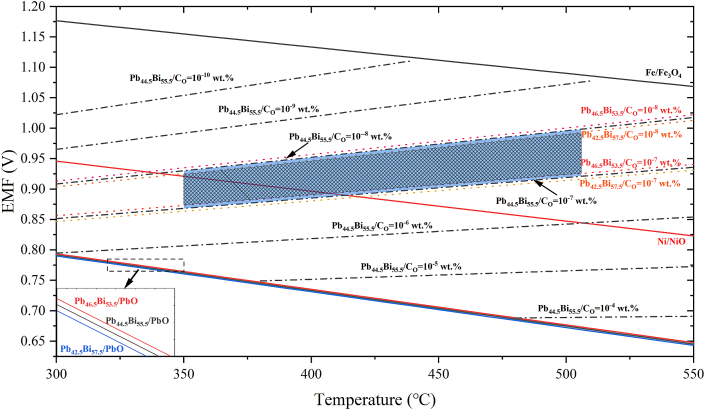

As discussed above, the concentration of dissolved oxygen in liquid LBE alloys should be controlled within an appropriate range to an ensure the useful life of reactors and ADSs. In actual operations, the lower CO limit is defined according the oxygen partial pressure corresponding to the Fe/Fe3O4 equilibrium point, while the upper CO limit is defined according the oxygen partial pressure corresponding to the Pb/PbO equilibrium point. However, the reactor coolant circuit of liquid LBE alloys is a non-isothermal system, and the melt exists in a variable temperature state within a range Tlow–Thigh. Therefore, if the CO control target is set to satisfy all temperature ranges, the upper CO limit should be set to the partial pressure corresponding to the Pb/PbO equilibrium point at Tlow, and the lower CO limit should be set to the partial pressure corresponding to the Fe/Fe3O4 equilibrium point at Thigh. Ideally, the CO control range in liquid LBE alloys operating within a temperature range of 350 °C–520 °C is 5.4 × 10−9–4.3 × 10−5 wt% [17].

Considering the effects of unevenly distributed concentrations of iron, the presence of impurities, and the lower temperature involved with cold shutdowns, the CO control range should be decreased further, and should be conservatively set at 1 × 10−8–1×10−7 wt%. Relationships between oxygen sensor voltage readings E and temperature T are presented in Figure 8 for different oxygen isoconcentration lines in liquid LBE alloys, where the blue shaded region in the figure represents the oxygen sensor range when the dissolved oxygen concentration in Pb44.5Bi55.5 resides within the conservative range of 1 × 10−8–1×10−7 wt%. Considering the influence of compositional changes in the liquid LBE alloy, the theoretical voltage of the oxygen sensor at T = 520 °C is 930.42 mV, 925.76 mV, and 921.01 mV when CO = 1 × 10−7 wt% in the lead-bismuth alloys with Bi contents of 57.5 wt%, 55.5 wt%, and 53.5 wt%, respectively. Accordingly, a change in Bi content of about 2 wt% will produce a voltage difference of about 5 mV in the output signal of the oxygen sensor, which seriously detracts from its measurement accuracy. Therefore, this voltage range should be decreased further, as indicated by the black grid in Figure 8. Here, the lower voltage limit is the voltage obtained for the Pb46.5Bi53.5 alloy when CO = 1 × 10−7 wt%, and the upper voltage limit is the voltage obtained for the Pb42.5Bi57.5 alloy when CO = 1 × 10−8 wt%. Accordingly, this analysis proposes higher requirements for the control of dissolved oxygen in LBE-cooled fast reactors.

Figure 8.

Relationships between oxygen sensor voltage readings and temperature for different oxygen isoconcentration lines in liquid LBE alloys, where the blue shaded region in the figure represents the oxygen sensor range when the dissolved oxygen concentration in Pb44.5Bi55.5 resides within the established conservative range of 1 × 10−8–1×10−7 wt%.

4. Conclusion

The present work addressed the lack of rigorous evaluation of the impacts of variations in the Bi contents of liquid LBE alloys on the accurate measurement of their dissolved oxygen concentrations by evaluating variations in oxygen concentration measurements obtained experimentally for oxygen-saturated liquid LBE alloys with different Bi contents at different temperatures using an LSCF-GDC/air oxygen sensor. Theoretical relationships were established between sensor voltage, oxygen concentration, temperature, and Bi content under the applied experimental conditions, and excellent agreement was obtained between the experimental and theoretical results. These relationships were then employed to obtain a rigorous accounting of the influence of Bi content on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements at different temperatures. The theoretical relationships establish that the voltage decreases by about 1 mV for every 1 wt% increase in Bi content at a temperature of 400 °C. And at a fixed voltage, with the increase of T, the influence of the Bi content on the CO calculation results gradually increased. Finally, the impact of varying Bi contents on the accuracy of oxygen concentration measurements was evaluated under practical reactor operation conditions, and higher requirements for the control of dissolved oxygen in LBE-cooled fast reactors were proposed. These results clearly demonstrate that the composition of LBE alloy coolants should be tested to ensure the accuracy of oxygen sensor measurements. Moreover, the composition of these coolants should be evaluated periodically during long-term operation to establish the accuracy of oxygen sensor signals.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Xian ZENG, Xie MENG, Qingzhi YAN: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Xintong ZHANG: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Wenliang ZHANG: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Xiaoxin ZHANG: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Professor Qingzhi Yan was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1932166).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Shmatko B., Rusanov A. Oxide protection of materials in melts of lead and bismuth. Mater. Sci. 2000;36:689–700. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alemberti A., Smirnov V., Smith C.F., Takahashi M. Overview of lead-cooled fast reactor activities. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 2014;77:300–307. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zrodnikov A., Efanov A., Orlov Y.I., Martynov P., Troyanov V., Rusanov A. Heavy liquid metal coolant–lead–bismuth and lead–technology. Atom. Energy. 2004;97:534–537. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nam H.O., Lim J., Han D.Y., Hwang I.S. Dissolved oxygen control and monitoring implementation in the liquid lead–bismuth eutectic loop: HELIOS. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008;376:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim J., Mariën A., Rosseel K., Aerts A., Van den Bosch J. Accuracy of potentiometric oxygen sensors with Bi/Bi2O3 reference electrode for use in liquid LBE. J. Nucl. Mater. 2012;429:270–275. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colominas S., Abella J., Victori L. Characterisation of an oxygen sensor based on In/In2O3 reference electrode. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004;335:260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manfredi G., Lim J., Rosseel K., Van den Bosch J., Aerts A., Doneux T., et al. Liquid metal/metal oxide reference electrodes for potentiometric oxygen sensor operating in liquid lead bismuth eutectic in a wide temperature range. Procedia Eng. 2014;87:264–267. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manfredi G., Lim J., Rosseel K., Van den Bosch J., Doneux T., Buess-Herman C., et al. Comparison of solid metal–metal oxide reference electrodes for potentiometric oxygen sensors in liquid lead–bismuth eutectic operating at low temperature ranges. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2015;214:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colominas S., Abella J. Evaluation of potentiometric oxygen sensors based on stabilized zirconia for molten 44.5% lead–55.5% bismuth alloy. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2010;145:720–725. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courouau J.-L. Electrochemical oxygen sensors for on-line monitoring in lead–bismuth alloys: status of development. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004;335:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng X., Wang Q., Meng X., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Yan Q., et al. Oxygen concentration measurement and control of lead-bismuth eutectic in a small, static experimental facility. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2020;57:590–598. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurata Y., Abe Y., Futakawa M., Oigawa H. Characterization and re-activation of oxygen sensors for use in liquid lead–bismuth. J. Nucl. Mater. 2010;398:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courouau J.-L., Trabuc P., Laplanche G., Deloffre P., Taraud P., Ollivier M., et al. Impurities and oxygen control in lead alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 2002;301:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marino A., Lim J., Keijers S., Van den Bosch J., Deconinck J., Rubio F., et al. Temperature dependence of dissolution rate of a lead oxide mass exchanger in lead–bismuth eutectic. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014;450:270–277. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gokcen N. The Bi-Pb (bismuth-lead) system. J. Phase Equil. 1992;13:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroer C., Konys J. Citeseer; 2007. Physical Chemistry of Corrosion and Oxygen Control in Liquid lead and lead Bismuth Eutectic. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fazio C., Sobolev V., Aerts A., Gavrilov S., Lambrinou K., Schuurmans P., et al. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; 2015. Handbook on lead-bismuth Eutectic alloy and lead Properties, Materials Compatibility, thermal-hydraulics and Technologies-2015 Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller G., Heinzel A., Schumacher G., Weisenburger A. Control of oxygen concentration in liquid lead and lead–bismuth. J. Nucl. Mater. 2003;321:256–262. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.