Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of yoga therapy (YT) on health outcomes of women suffering from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Interventional studies, with postmenarchal and premenopausal females with PCOS who received YT, with any health outcome reported, were included. Scopus, Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, and Medline databases were electronically searched. Systematic review included 11 experimental studies, representing 515 participants with PCOS, out of which 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included for meta-analysis. Random effects model was applied using Review Manager Software version 5.4.1 and strength of evidence was assessed using GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool, 2020. Meta-analysis showed that YT may significantly decrease menstrual irregularity (MD −.41, 95% CI −.74 to −.08), clinical hyperandrogenism (MD −.70, 95% CI −1.15 to −.26), fasting blood glucose (MD −.22 mmol/L, 95% CI −.44 to −.01), fasting insulin (MD −28.21 pmol/L, 95% CI −43.79 to −12.63), and homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance value (MD −.86, 95% CI −1.29 to −.43). Strength of evidence was “low.” In conclusion, YT may have beneficial effects on health outcomes in women suffering from PCOS. However, low strength of evidence suggests need of conducting well-designed RCTs to assess the efficacy of YT for PCOS.

Keywords: yoga therapy, holistic health, mind–body intervention, polycystic ovary syndrome, lifestyle disorder

Yoga encompasses all the components of lifestyle modification, thereby promoting holistic health

Introduction

Lifestyle changes have caused immense impact on overall health and well-being of an individual giving rise to several health disorders like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) among females. PCOS is emerging as one of the most common endocrine and metabolic disorder affecting 8–13% women 1 of reproductive age group worldwide causing significant health consequences for women impairing quality of life and increasing risk of comorbidity like glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus, systemic inflammation, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. 2 PCOS is also one of the leading causes of infertility among women of reproductive age group 3 and also has an adverse impact on their psychological well-being.4,5

The complexity of the disorder and its impact on quality of life requires timely diagnosis, screening for complications and management strategies. The most common diagnostic criteria for PCOS is Rotterdam criterion 1 defined as at least two of the following three features: oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (cycle length of ≥45 days and/or ≤8 cycles per year); hyperandrogenism (score of ≥6 on modified Ferriman–Gallwey scale or serum testosterone level >82 ng/dL); and polycystic ovaries (presence of more than 10 cysts in each ovary or an ovarian volume greater than 10 cm3 on ultrasound) in the absence of other endocrine etiologies such as thyroid disease, non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and hyperprolactinemia.

Treatment goals in PCOS include improving hormonal imbalance, weight management, and improving quality of life. Lifestyle interventions (dietary, exercise, behavioral or combined) are recommended as first-line management according to latest evidence-based European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology-2018 guidelines for PCOS. 1 Several pharmacological and surgical options target individual reproductive, androgenic, metabolic, weight-related, and psychological symptoms in women of different age groups suffering from PCOS. These conventional therapeutic options may have unwanted side effects, whereas lifestyle modifications offer a holistic treatment by improving underlying hormonal imbalance, optimizing weight, and improving quality of life of women suffering from PCOS. 1

Yoga, a form of mind–body intervention, encompasses all the components of lifestyle modification (diet, exercise, and behavior), thereby promoting holistic health of an individual. 6 Several interventional trials have been conducted which assess the effectiveness of yoga therapy (YT) on neuroendocrine, anthropometric, metabolic, and quality of life factor in women with PCOS. However, to the best of author(s)’ knowledge, currently there is no systematic review or meta-analysis assessing the evidence for effectiveness of specifically YT on health outcomes in women with PCOS. Thus, this review aims at specifically assessing the effect of YT on health outcomes in women with PCOS.

Materials and Methods

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 7 (PRISMA Checklist provided as Supplementary Tables S1a and S1b) and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42021229619.

Eligibility Criteria

Criteria for Systematic Review

In this systematic review, all empirical research studies studying the effect of YT as an intervention for women diagnosed with PCOS were included. Theoretical research studies were excluded from this review in order to reduce heterogeneity. Studies were included if they measured the effect of any form of YT on PCOS-related reproductive, metabolic, anthropometric, or quality of life health outcomes either clinically or by using validated tools.

Criteria for Meta-Analysis

Studies were considered for meta-analysis if they met the following eligibility criteria:

1. Type of studies: randomized controlled trial (RCT).

2. Type of participants: postmenarchal and premenopausal females with PCOS diagnosed on the basis of Rotterdam criteria.

-

3. Type of interventions:

a. Intervention group: YT (defined as structured yogic postures, breathing, meditation, and relaxation techniques) for duration of 12 weeks or more.

b. Control group.

c. Minimal treatment (MT) (defined as either no treatment or standard unstructured minimal dietary, exercise or behavioral advice).

-

4. Type of outcome measures (measured at end of intervention):

-

a. Primary outcome:

-

o. Reproductive:

➢ Menstrual cycle regularity (initiation of menses or significant shortening of cycle length or increase in cycle frequency per month).

-

-

b. Secondary outcomes:

-

o. Reproductive:

➢ Clinical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism assessed clinically by modified Ferriman–Gallwey (mFG) score).

-

o. Metabolic:

➢ Fasting blood glucose (FBG) level,

➢ fasting insulin (FI) level, and

➢ homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).

-

o. Anthropometric:

➢ body mass index (BMI) and

➢ waist-to-hip ratio (WHR).

-

o. Quality of life (psychological):

➢ anxiety and depression (measured by validated scales).

-

-

Information Sources and Search Terms

Electronic databases Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, Medline, and Scopus were searched for identification of relevant studies published till July 2020. Also, controlled trials registries Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI), conference abstracts, relevant journals, reference lists of relevant papers, and reviews were electronically hand searched to identify further eligible studies. Searches were re-run prior to the final analysis and submission. Yoga, lifestyle management, complementary and alternative therapy, PCOS, and randomized controlled trials were used as keywords and MeSH terms. Results were refined by selecting only interventional trials which primarily assessed the effect of YT on any health outcomes of women of any age group suffering from PCOS. Summary of search methods is provided in Supplementary Tables S2a and S2b.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Relevant studies, searched from abovementioned databases, were then exported to citation manager (Mendeley version 1.19.4) for filtering and elimination of duplicates. Titles and abstracts of articles thus retrieved were screened individually, and verified and full text versions of potentially eligible studies were obtained. The following information was then extracted from each study: location of study, study design, number of subjects with their mean age, PCOS diagnosis criteria, intervention, follow-up period, and information related to outcomes. Main trial report was used as reference for studies which had multiple publications, and additional details were provided from their secondary research articles. Unit conversion factors applied in this review are provided in Supplementary TableS3.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Quality of included studies were assessed using the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trial (RoB2) 8 and Risk-of-Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. 9 Rating of studies were categorized as per abovementioned scales.

Synthesis of Results

Extraction and summarization of data for health outcome was done by meta-analysis for homogenous studies. Random effects model was used combining data from included studies. For continuous data, mean difference (MD) and related 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between treatment groups were calculated for measurement of treatment effect. Heterogeneity was estimated by I-squared statistics. Data management and analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1 (RevMan 2020, The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Overall Quality of Evidence

Strength of evidence for significant outcomes was assessed using GRADEpro and Cochrane methods. 10 The quality of evidence was assessed on the basis of following GRADE criteria: risk of bias (lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding, incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events, selective outcome reporting, other limitations); inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity or variability in results across studies); imprecision (uncertainty in results due to few patients and events and wide CI around the estimate of the effect); indirectness (evidence does not directly answer the health care question asked); and other considerations like publication bias (selective publication of studies). Based on these criteria, the quality of evidence was assessed into one of the four categories: high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Search Results

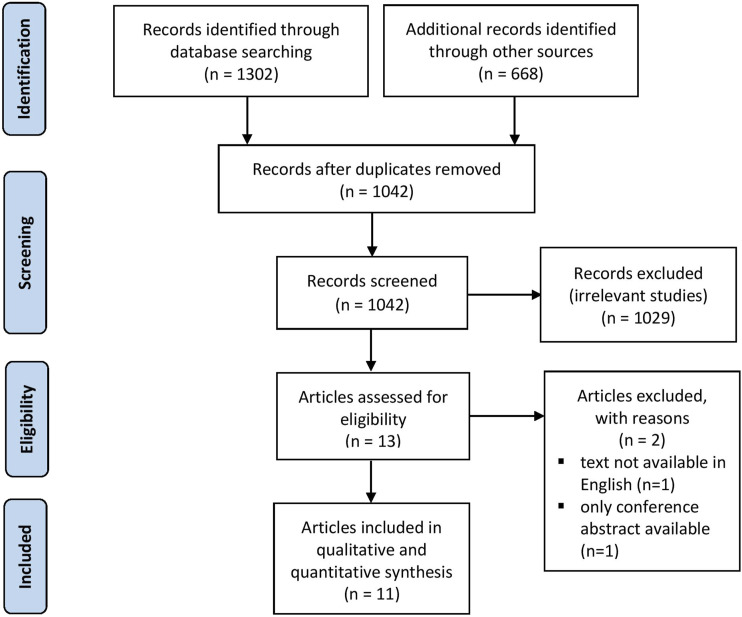

Process of study selection is detailed in PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Initial search retrieved 1302 articles from electronic databases [Scopus (n = 546), Cochrane CENTRAL (n = 249), PubMed (n = 135), and Embase (n = 372)] and 668 trials from CTRI database. Duplicate records were removed to yield 1042 articles which were then screened for irrelevant studies (n = 1029) based on title and abstract. As a result, 13 full text articles were then assessed for eligibility, from which 2 articles were excluded as text of one research article was not available in English and only conference abstract was available for another article. The remaining 11 articles were included for systematic review. Out of these, 3 RCTs belonged to the same study (study by Nidhi et al had 3 publications). Hence, a total of 9 studies were available for this review. Further, 2 RCTs (Nidhi et al, 2012, 2013a, 2013b; Patel et al, 2020) were included for meta-analysis due to homogeneity.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for study selection.

Characteristics of Eligible Studies

Characteristics of eligible studies are provided in Table 1. A total of 11 studies were found eligible for this review which were conducted in India, Iran, and the United States. Out of these studies, 9 were included for this review among which 3 studies were RCTs, 5 were pre-post clinical trials, and 1 was case series. A total number of subjects were 515 which were diagnosed with PCOS on the basis of Rotterdam and other assessment criteria. Intervention provided in these studies primarily consisted of YT. Follow-up duration of these studies ranged from 6 weeks to 4 months. Effect of YT on health outcomes including reproductive, metabolic, anthropometric, and quality of life was assessed in these studies.

Table 1.

Demographic Details of Eligible Studies.

| # | Study, year | Country | Study design | Number of subjects (females) | Mean age ± SD | PCOS diagnosis criteria | Intervention | Follow-up duration | Outcomes measured | Included in systematic review or meta-analysis or both | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga group | Control group | Yoga group | Control group | Yoga group | Control group | ||||||||

| 1 | Bahrami et al, 16 2019 | Iran | RCT | 31 | 30 | 30.77 ± 6.01 | 30.35 ± 5.53 | Cannot be specified | Yoga practices consisting of asanas, pranayama, and relaxation techniques | No intervention | 6 weeks |

Primary: Quality of life,

hirsutism, no. of follicles/ovary, no. of embryos, and

βHCG Secondary: Weight, acne, infertility, and menstrual disorder |

No; article text not available in English |

| 2 | Nidhi et al,11-13 2012 | India | RCT | 42 | 43 | 16.22 ± 1.13 | 16.22 ± .93 | Rotterdam criteria | Yoga practices consisting of asanas, pranayama, relaxation techniques, meditation, and counseling | Similar set of conventional physical exercises along with counseling session | 3 months |

Primary: Serum FI, FBG,

AMH, serum lipids,

a

state anxiety, and trait

anxiety Secondary: BMI, WHR, LH, FSH, TT, prolactin, mFG score, and menstrual cycle length |

Yes (included in systematic review and meta-analysis) |

| 3 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | United States | RCT | 13 | 9 | 30.9 ± 1.2 | 31.2 ± 2.3 | Rotterdam criteria | Yoga practices consisting of mental body scan, pranayama, asanas (vinyasa and restorative), and meditation | Wait list, no intervention was given | 3 months |

Primary: Serum

testosterone level Secondary: Menstrual cycle length, mFG score, DHEA, DHEAS, A4, FBG, FI, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, WHR, BMI, BAI score, and BDI-II score |

Yes (included in systematic review and meta-analysis) |

| 4 | Rao et al, 19 2018 | India | RCT | 32 | 32 | 29.23 ± 5.34 | 29.27 ± 5.06 | Rotterdam criteria | Ayurvedic treatment consisting of Panchakarma practices and Ayurvedic medicines along with yoga practices consisting of asanas, pranayama, relaxation techniques, and meditation | Ayurvedic treatment consisting of Panchakarma practices and Ayurvedic medicines | 3 months | AMH, prolactin, testosterone, FSH, LH, T3, T4, TSH, ovarian mass, HbA1C, weight, anxiety, and depression | Included in systematic review |

| 5 | Ratnakumari et al, 23 2018 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 25 | 25 | 23.77 ± 5.33 | 25.05 ± 4.83 | Rotterdam criteria | Yoga intervention consisting of asanas, pranayama, relaxation techniques and kriyas and naturopathic intervention consisting of hydrotherapy, mud therapy, manipulative therapy, fasting, and diet | Wait list, no intervention given | 12 weeks |

Primary: Ovarian

morphology Secondary: Body weight, BMI, chest circumference, waist circumference, hip circumference, and WHR |

Included in systematic review |

| 6 | Shalini et al, 17 2019 | India | Case series | 10 | — | Not provided | — | Cannot be specified | Asanas along with varma stimulations and internal medication | — | 3 months | Irregular menstrual cycle, duration of bleeding, and BMI | Included in systematic review |

| 7 | Shanthi et al, 18 2014 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 10 | — | 25 ± 5.23 | — | Cannot be specified | Kayakalp yogic exercises | — | 3 months | FSH, LH, Hb, PP blood glucose, and cholesterol | Included in systematic review |

| 8 | Selvaraj et al, 15 2020 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 102 | 102 | 33.42 ± 7.33 | 22.87 ± 12.15 | PCOS risk assessment questionnaire | Yoga practices consisting of asanas, pranayama, relaxation techniques, meditation, counseling, and brisk walking | No intervention | 4 months | PCOS risk minimization | Included in systematic review |

| 9 | Sode et al, 24 2017 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 30 | — | Cannot be specified | — | Rotterdam criteria | Yoga module comprising of asanas, pranayama, and meditation | — | 1 month | Level of depression | Included in systematic review |

| 10 | Vanitha et al, 22 2018 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 40 | — | 26.13 ± 5.30 | — | Rotterdam criteria | Yoga nidra | — | 3 months |

Primary: Blood glucose

levels, lipid profile, and

HbA1C Secondary: BMI, WHR, SBP, and DBP |

Included in systematic review |

| 11 | Verma et al, 21 2017 | India | Pre-post clinical trial | 30 | — | Cannot be specified | — | Cannot be specified | Yoga | — | 3 months | FBG, FI, and HOMA-IR | No; only conference abstract available for this study |

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; βHCG, positive beta human chorionic gonadotropin; FI, fasting insulin; FBG, fasting blood glucose; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; TT, total testosterone; mFG, modified Ferriman–Gallwey; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; A4, androstenedione; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; Hb, hemoglobin; PP, post-prandial; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin.

aSerum lipids: total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TRIG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), TC/HDL.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

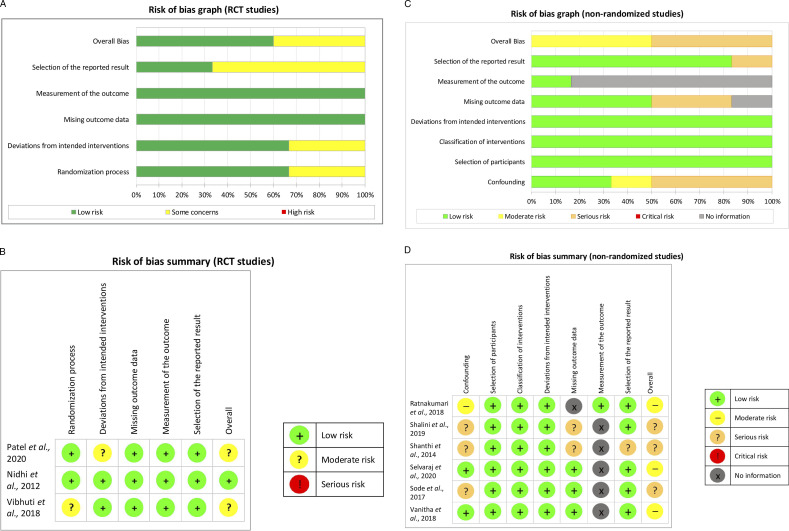

Among RCT studies, 1 study was assessed with low overall risk of bias and the other 2 studies with moderate overall risk of bias. Among non-randomized studies, 3 studies were assessed with moderate overall risk of bias and 3 studies with serious overall risk of bias. Thus, among all 9 studies included for this review, 1 study was assessed to be of high quality, 5 were of moderate quality, and remaining 3 studies were of low quality. Risk of bias graph and summary for RCT and non-randomized studies is shown in Figures 2A-2D.

Figure 2.

(A) Risk of bias graph (randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies). (B) Risk of bias summary (RCT studies). (C) Risk of bias graph (non-randomized studies). (D) Risk of bias summary (non-randomized studies).

Overall Quality of Evidence

Summary of findings presented in Table 2 evaluates the overall quality of body of evidence for review outcomes including menstrual regularity, clinical hyperandrogenism, glucose tolerance, BMI, WHR, and anxiety level. Outcome data were extracted from included studies and comparisons were formatted in data tables for preparation of “Summary of Findings” table. Evidence quality was then classified into high, moderate, low, or very low according to GRADE criteria and incorporated into reporting of the results for each outcome.

Table 2.

Summary of Findings.

| Yoga therapy compared to minimal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome | ||||

| Patient or population: Women

with polycystic ovary syndrome Setting: Residential college, wellness center Intervention: Yoga therapy Comparison: Minimal treatment (exercise or no intervention) | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated effects | Effect estimate a (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Reproductive outcome: Menstrual regularity (frequency in months) | YT may reduce menstrual irregularity (frequency in months) by .41 (improvement of .74 to .08) | MD −.41 [−.74, −.08] | 72 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕○○LOWb,c |

| Reproductive outcome: Clinical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism) (mFG score) | YT may reduce clinical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism) (mFG score) by .70 (reduction of 1.15 to .26) | MD −.70 [−1.15, −.26] | 94 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Metabolic outcome: FBG (mmol/L) | YT may reduce FBG by .22 mmol/L (reduction of .44 mmol/L to .01 mmol/L) | MD −.22 [−.44, −.01] mmol/L | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Metabolic outcome: FI (pmol/L) | YT may reduce FI by 28.21 pmol/L (reduction of 43.79 pmol/L to 12.63 pmol/L) | MD −28.21 [−43.79, −12.63] pmol/L | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Metabolic outcome: HOMA-IR value | YT may reduce HOMA-IR value by .86 (reduction of 1.29 to .43) | MD −.86 [−1.29, −.43] | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Anthropometric outcome: BMI (kg/m2) | YT may reduce BMI by 1.38 kg/m2 (reduction of 2.37 kg/m2 to .40 kg/m2) | MD −1.38 [−2.37, −.40] kg/m2 | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Anthropometric outcome: WHR | YT may slightly reduce WHR by .02 (reduction of .03 to .01) | MD −.02 [−.03, −.01] | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

| Quality of life: Anxiety level score | Uncertain of effect of YT on anxiety level score | SMD −.13 [−.54, .28] | 94 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕○○ LOWc,d |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference; SMD, standardized mean difference; YT, yoga therapy; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FI, fasting insulin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

GRADE working group grades of evidence: ⊕⊕⊕⊕: True effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. ⊕⊕⊕○: True effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. ⊕⊕○○: True effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. ⊕○○○: True effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

aRisk in intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on assumed risk in comparison group and relative effect of intervention (and its 95% CI).

bDowngraded one level for inconsistency: only one study reported this outcome.

cDowngraded one level for imprecision: few number of participants.

dDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: high attrition rate of participants.

Systematic Review

Summary of effect of YT on health outcomes as mentioned in included studies among women suffering from PCOS is presented in Tables 3–6.

Table 4.

Systematic Review: Change in Metabolic Outcomes After Intervention Among Women with PCOS.

| # | Study, year | Group | Metabolic outcomes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FI | FBG | HOMA-IR | Lipid profile | HbA1C | |||||||||||||

| n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | |||

| 1 | Nidhi et al, 12 2012 | YT | 35 | ↓9.04 ± 32.31 | < .001 b | 35 | ↓.24 ± .39 | < .001 b | 35 | ↓.38 ± .92 | <.05 a | 35 | TRIG ↓.15 ± .12 TCHL ↓.24 ± .29 HDL ↑.03 ± .04 LDL ↓.21 ± .25 VLDL ↓.06 ± .05 |

<.001

b

<.001 b <.001 b <.001 b <.001 b |

NS | NS | NS |

| C | 36 | ↑11.09 ± 56.85 | <.001 b | 36 | ↑.04 ± .44 | .47 | 36 | ↑.29 ± 1.56 | .19 | 36 | TRIG ↓.07 ± .12 TCHL ↓.07 ± .46 HDL ↑.03 ± .58 LDL ↓.07 ± .39 VLDL ↓.03 ± .06 |

<.001

b

.15 <.01 b .13 <.001 b |

NS | NS | NS | ||

| 2 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | YT | 13 | ↓6 ± 69.55 | .824 | 13 | ↓.09 ± .11 | .387 | 13 | ↓.3 ± 2.31 | .693 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| C | 9 | ↓12.6 ± 20.12 | .328 | 9 | ↑.16 ± .21 | .403 | 9 | ↓.48 ± .86 | .382 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| 3 | Shanthi et al, 2014 | YT | NS | NS | NS | 10 | ↓1.2 ± .40 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10 | TCHL ↓1.01 ± .37 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 4 | Vanitha et al, 22 2018 | YT | NS | NS | NS | 40 | ↓.42 ± .68 | .001 b | NS | NS | NS | 40 | TRIG ↓.38 ± .69 TCHL ↓.31 ± .84 HDL ↑.11 ± .18 LDL ↓.46 ± .77 VLDL ↓.05 ± .15 |

.001

b

.001 b .0001 b .0001 b .0001 b |

40 | ↓.62 ± .57 | .0001 a |

| 5 | Vibhuti et al, 2018 | YT + A | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 30 | ↓1.13 ± .54 | .017 a |

| A | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 30 | ↑2.11 ± .51 | .035 a | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; FI, fasting insulin; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; YT, yoga therapy; C, control; A, Ayurveda; NS, not specified.

aSignificant at P < .05.

bSignificant at P < .01.

Table 5.

Systematic Review: Change in Anthropometric Outcomes After Intervention Among Women with PCOS.

| # | Study, year | Group | Anthropometric outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | BMI | WHR | |||||||||

| N | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | |||

| 1 | Nidhi et al, 12 2012 | YT | 37 | ↓.04 ± 1.34 | .882 | 35 | ↓.11 ± .51 | .32 | 35 | ↓.01 ± .05 | .53 |

| C | 35 | ↑.79 ± 4.13 | 36 | ↑.31 ± 1.63 | .66 | 36 | 0 ± .05 | .42 | |||

| 2 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | YT | NS | NS | NS | 13 | ↓.3 ± 1.95 | .38 | 13 | ↓.013 ± .016 | .32 |

| C | NS | NS | NS | 9 | ↑.2 ± 3.3 | 0.4 | 9 | ↑.011 ± .02 | .34 | ||

| 3 | Ratnakumari et al, 23 2018 c | YT + N | 22 | ↓6 (4, 8) | <.001 a | 22 | ↓2.36 (1.6, 3.28) | <.001 a | 22 | ↑.01 (−.03, .02) | .777 |

| C | 22 | 0 (−1.5, 2) | 22 | 0 (−.49, 0.84) | 22 | ↑.01 (−.04, .01) | |||||

| 4 | Shalini et al, 17 2019 | YT + S | NS | NS | NS | 10 | ↓.6 ± .81 | <.001 a | NS | NS | NS |

| 5 | Vanitha et al, 22 2018 | YT | 40 | ↓4.34 ± 12.56 | .001 a | 40 | ↓1.83 ± 4.59 | .001 a | 40 | ↓.04 ± .03 | .02 a |

| 6 | Vibhuti et al, 2018 | YT + A | 30 | ↓.51 ± 16.55 | .607 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| A | 30 | ↓.85 ± 9.58 | .396 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; YT, yoga therapy; C, control; N, naturopathy; S, Siddha; A, Ayurveda; NS, not specified.

aSignificant at P < .05.

bSignificant at P < .01.

cValues provided in median (quartile 1, quartile 3).

Table 3.

Systematic Review: Change in Reproductive Outcomes After Intervention Among Women with PCOS.

| # | Study, year | Group | Reproductive outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual cycle regularity | Ovarian volume | mFG score | Testosterone | AMH | FSH | LH | |||||||||||||||||

| N | Mean change ±SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | n | Mean change ± SD | P | |||

| 1 | Nidhi et al, 12 2012 | YT | 37 | ↑.89 ± .66 | .049 a | NS | NS | NS | 37 | ↓1.14 ± 1.44 | .002 b | NS | NS | NS | 37 | ↓2.51 ± 2.92 | .006 b | 37 | ↓.40 ± 2.27 | .474 | 37 | ↓4.09 ± 9.99 | .005 b |

| C | 35 | ↑.49 ± .98 | NS | NS | NS | 35 | ↑.06 ± 1.51 | NS | NS | NS | 35 | ↓.49 ± 2.20 | 35 | ↓.31 ± 2.70 | 35 | ↑3.00 ± 7.48 | |||||||

| 2 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | YT | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 13 | 0 ± 0.6 | .95 | 13 | ↓1.72 ± .95 | .041 a | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| C | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 9 | 0 ± 0.6 | .99 | 9 | ↓.03 ± 1.46 | .967 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| 3 | Ratnakumari et al, 23 2018 c | YT + N | 22 | 29 days | .124 | 22 | Right ↓1.67 (−3.8, 7.04) Left ↓3.68 (1.1, 8.44) |

.307 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| C | 22 | 33 days | 22 | Right ↑1.02 (−4.06, 3.7) Left ↑.79 (−4.5, 4.33) |

.032 a | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||

| 4 | Shalini et al, 17 2019 | YT + S | 10 | ↓1.80 ± .60 | <.001 b | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 5 | Shanthi et al, 2014 | YT | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10 | ↓.17 ± 1.18 | NS | 10 | ↓11.97 ± 6.67 | NS |

| 6 | Vibhuti et al, 2018 | YT + A | NS | NS | NS | 30 | Right ↓1.70 ± 4.38 Left ↓2.76 ± 3.86 |

.003

b

089 |

NS | NS | NS | 30 | ↓2.94 ± 6.86 | .003 b | 30 | ↓2.86 ± 2.43 | .004 b | 30 | ↓.35 ± 16.06 | .728 | 30 | ↓2.77 ± 6.25 | .006 b |

| A | NS | NS | NS | 30 | Right ↓1.99 ± 4.58 Left ↓1.25 ± 5.59 |

.376 .167 |

NS | NS | NS | 30 | ↓1.11 ± 6.32 | .266 | 30 | ↓2.76 ± 3.71 | .006 b | 30 | ↓1.23 ± 3.36 | .218 | 30 | ↓1.27 ± 5.06 | .204 | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; mFG, modified Ferriman–Gallwey; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; YT, yoga therapy; C, control; N, naturopathy; S, Siddha; A, Ayurveda; NS, not specified.

aSignificant at P < .05.

bSignificant at P < .01.

cValues provided in median (quartile 1, quartile 3).

Table 6.

Systematic Review: Change in Quality of Life Outcomes After Intervention Among Women with PCOS.

| # | Study, year | Group | Quality of life outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | |||||||

| n | Mean change ± SD | P | N | Mean change ± SD | P | |||

| 1 | Nidhi et al, 12 2012 | YT | 35 | ↓14.97 ± 9.87 | .002 a | NS | NS | NS |

| C | 36 | ↓7.42 ± 7.57 | NS | NS | NS | |||

| 2 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | YT | 13 | ↓3.1 ± 2.59 | .037 | 13 | ↓8.75 ± 2.47 | <.0001 a |

| C | 9 | ↓1.1 ± 2.57 | .633 | 9 | ↓6 ±1.91 | .06 a | ||

| 3 | Sode et al, 24 2017 | YT | NS | NS | NS | 30 | ↓13.51 ± 7.37 | <.0001 a |

| 4 | Vibhuti et al, 2018 | YT + A | 30 | ↓6.30 ± 3.54 | <.001 a | 30 | ↓6.08 ± 3.85 | <.001 a |

| A | 30 | ↓4.64 ± 3.12 | <.001 a | 30 | ↓3.79 ± 3.48 | <.001 a | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; YT, yoga therapy; C, control; A, Ayurveda; NS, not specified.

aSignificant at P < .05.

bSignificant at P < .01.

Reproductive Outcomes

Menstrual cycle regularity significantly increased (P < .001) in the study by Shalini et al, 2019; right ovarian volume significantly decreased (P = .001) in the study by Vibhuti et al, 2018; mFG score significantly decreased (P = .002) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012; testosterone levels significantly decreased (P = .002 and P = .041) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012 and Patel et al, 2020, respectively; anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels significantly decreased (P = .006 and P = .004) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012 and Vibhuti et al, 2018, respectively; and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels significantly decreased (P = .005 and P = .006) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012 and Vibhuti et al., 2018, respectively.

Metabolic Outcomes

FI level significantly decreased (P < .001) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012; FBG level significantly decreased (P = .001) in the study by Vanitha et al, 2018; lipid profile significantly improved (P = .001) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012 and Vanitha et al, 2018; and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) level significantly decreased (P = .0001 and P = .01) in the study by Vanitha et al, 2018 and Vibhuti et al, 2018, respectively.

Anthropometric Outcomes

Weight of the study participants significantly decreased (P < .001) in the study by Ratnakumari et al, 2018 and Vanitha et al, 2018; BMI significantly decreased (P < .001) in the study by Ratnakumari et al, 2018, Shalini et al, 2019, and Vanitha et al, 2018; and WHR significantly decreased (P < .02) in the study by Vanitha et al, 2018.

Quality of Life Outcomes

Anxiety level significantly decreased (P = .002, P < .001) in the study by Nidhi et al, 2012 and Vibhuti et al, 2018, respectively and depression level significantly decreased (P < .0001, P < .0001, P < .001) in the study by Patel et al, 2020, Sode et al, 2017, and Vibhuti et al, 2018, respectively.

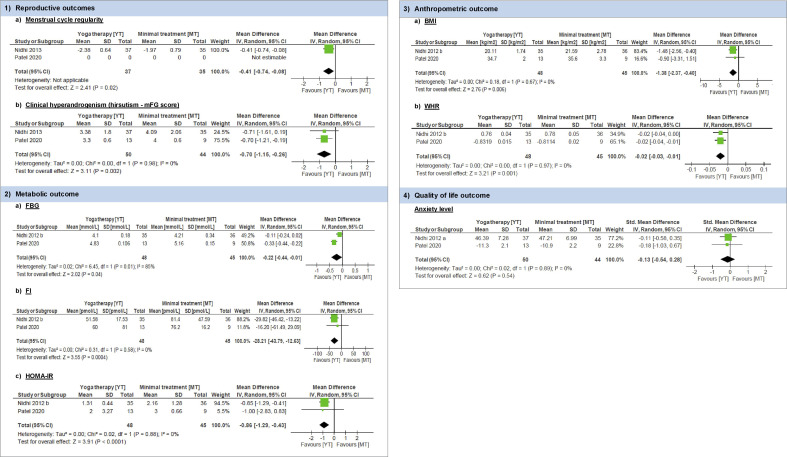

Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted for two of the included studies for primary and secondary health outcomes as defined in this review and is presented as forest plots in Figure 3. Comparison of health outcomes of included studies is represented in Table 7.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of health outcomes.

Table 7.

Comparison of Health Outcomes.

| # | Study, year | Outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual cycle regularity | mFG score | FBG | FI | HOMA-IR value | BMI | WHR | Anxiety level | |||||||||||||||||||

| Group | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | n | Mean change | P | ||

| 1 | Patel et al, 14 2020 | Yoga therapy | — | — | — | 13 | 0 ± .6 | .95 | 13 | ↓.09 ± .11 | .387 | 13 | ↓6 ± 69.55 | .824 | 13 | ↓.3 ± 2.31 | .693 | 13 | ↓.3 ± 1.95 | .38 | 13 | ↓.013 ± .016 | .32 | 13 | ↓3.1 ± 2.59 | .037 |

| No intervention | — | — | — | 9 | 0 ± .6 | .99 | 9 | ↑.16 ± .21 | .403 | 9 | ↓12.6 ± 20.12 | .328 | 9 | ↓.48 ± .86 | .382 | 9 | ↑.2 ± 3.3 | .40 | 9 | ↑.011 ± .02 | .34 | 9 | ↓1.1 ± 2.57 | .633 | ||

| 2 | Nidhi et al, 12 2012 | Yoga therapy | 37 | ↑.89 ± .66 | .049 | 37 | ↓1.14 ± 1.44 | .002 | ↓.24 ± .39 | <.001 | 35 | ↓9.04 ± 32.21 | <.001 | 35 | ↓.38 ± .92 | <.05 | 35 | ↓.11 ± .51 | .32 | 35 | ↓.01 ± .05 | .53 | 35 | ↓14.97 ± 9.87 | .002 | |

| Exercise | 35 | .49 ± ↑.98 | 35 | ↑.06 ± 1.15 | ↑.04 ± .44 | .47 | 36 | ↑11.09 ± 56.85 | <.001 | 36 | ↑.29 ± 1.56 | .19 | 36 | ↑.31 ± 1.63 | .66 | 36 | 0 ± .05 | .42 | 36 | ↓7.42 ± 7.57 | ||||||

Abbreviations: mFG, modified Ferriman–Gallwey; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FI, fasting insulin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Primary Outcome

Reproductive

Menstrual cycle regularity (defined as initiation of menses or significant shortening of cycle length or increase in cycle frequency per month): Only one study11-13 reported on this outcome. This study reported the data as mean ± SD menstrual cycle frequency per month for YT vs MT [2.38 ± .64 vs 1.97 ± .79, MD .41, 95% CI −.74 to −.08, P = .02] suggestive of YT resulting in a greater increase in menstrual cycle frequency per month as compared to MT (exercise).

Secondary Outcomes

Reproductive

Clinical Hyperandrogenism (hirsutism assessed clinically by mFG score) was assessed in both included studies by reporting changes in mFG scores. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in a greater decrease in hirsutism (mFG score) (MD −.70, 95% CI −1.15 to −.26, I2 = 0%) compared to MT, with very low heterogeneity.

Metabolic

1. FBG level was measured in both included studies. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in slight decrease in hirsutism (mFG score) (MD −.22 mmol/L, 95% CI − 44 to −.01, I2 = 85%) compared to MT, with high heterogeneity.

2. FI level was measured in both included studies. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in slight decrease in FI level (MD −28.21 pmol/L, 95% CI −43.79 to −12.63, I2 = 0%) compared to MT.

3. HOMA-IR was measured in both included studies. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in slight decrease in HOMA-IR value (MD −.86, 95% CI −1.29 to −.43, I2 = 0%) compared to MT.

Anthropometric

1. BMI was measured in both included studies. Both included studies observed no significant change in BMI in both groups. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in slight decrease in BMI (MD − 1.38 kg/m2, 95% CI − 2.37 to − .40, I2 = 0%) compared to MT.

2. WHR was measured in both included studies. Both included studies observed no significant change in WHR in both groups. Pooled analysis of results show that YT may result in slight decrease in WHR (MD − .02, 95% CI − .03 to − .10, I2 = 0%) compared to MT.

Quality of Life (Psychological)

Anxiety level was measured in both included studies. Both included studies observed significant change in experimental group. One study11-13 showed significant changes in trait anxiety scores in experimental group. Other study 14 showed significant change in Beck Anxiety Inventory scores in the experimental group. However, pooled analysis of results shows uncertainty about the effect of YT on anxiety levels (SMD − .13, 95% CI − .54 to .28, I2 = 0%) as compared to MT.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed at investigating the effect of YT on health outcomes in women with PCOS. Data from these studies showed evidence of beneficial effect of YT on reproductive (menstrual irregularity and clinical hyperandrogenism), metabolic (FBG, FI, and HOMA-IR values) and anthropometric outcomes (BMI and WHR) as compared to MT. However, pooled results show uncertainty about the effect of YT on quality of life outcome (anxiety level) as compared to MT.

Findings

Reproductive Outcomes

The RCTs included in meta-analysis are suggestive of beneficial effects of YT on reproductive health outcomes such as menstrual regularity and clinical hyperandrogenism.

Menstrual regularity was however reported as an outcome measure in only one 13 of the studies included in meta-analysis. A recent study involving adolescent girls conducted in India 15 reported slight improvement on menstrual conditions after 2 months of YT intervention along with 2 months of brisk walking. Another study involving females suffering from infertility in Iran 16 reported a significant reduction in menstrual disorders (P < .001) after 6 weeks of YT intervention. Also, a case series study conducted in India 17 reported significant improvement in menstrual cycle regularity (P < .001) after 3 months of YT intervention along with Siddha medication among females suffering from PCOS.

The effect of YT intervention on biochemical hyperandrogenism (in the form of androgen excess) was reported for different endocrine hormones and showed reduction in serum and total testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, LH, and AMH levels of participants in the intervention group. A clinical trial conducted on females with PCOS reported significant decrease in LH level (P < .001) after 3 months of YT intervention. 18 Also, a RCT reported significant decrease in levels of LH (P = .006), testosterone (P = .003), and AMH (P = .004) in females with PCOS after 3 months of YT along with Ayurveda treatment. 19

This meta-analysis assessed the effect of YT intervention on clinical features of hyperandrogenism, mainly hirsutism, in the form of reduction in mFG scores. Findings of meta-analysis are suggestive of beneficial effect of YT in reducing hirsutism. This is consistent with the results of latest Cochrane review 20 on lifestyle changes in women with PCOS which suggests that lifestyle treatment may improve biochemical and clinical hyperandrogenism which is in agreement with recommendations of international ESHRE-2018 guidelines for PCOS. 1

Metabolic Outcomes

In terms of metabolic outcomes, the included trials showed positive effects of YT in reduction of levels of FBG, FI, and HOMA-IR. The results are similar to the findings of another study conducted in India which reported significant reduction in these metabolic outcomes (P < .01) after 12 weeks of YT intervention. 21 A clinical trial conducted on females with PCOS reported significant decrease in post-prandial blood sugar (PPBS) level (P < .001) after 3 months of YT intervention. 18 An RCT reported significant decrease in HbA1C level (P = .017) in females with PCOS after 3 months of YT along with Ayurveda treatment. 19 Also, another study similarly reported significant improvement in metabolic outcomes (FBG, PPBS, and HbA1C) (P < .001) of study participants after 3 months of YT intervention. 22 This is consistent with the evidence-based recommendation of ESHRE-2018 guidelines 1 that multicomponent lifestyle intervention should be recommended in all those with PCOS and excess weight, for reductions in weight, central obesity, and insulin resistance.

Similarly, changes in lipid profile after YT intervention was reported in only one 13 of the studies included in meta-analysis which reported significant improvement in lipid profile of participants in the intervention group. A clinical trial conducted on females with PCOS reported significant decrease in cholesterol level (P < .001) after 3 months of YT intervention. 18 A similar trial reported significant improvement in lipid profile (P < .001) of study participants after 3 months of YT intervention. 22

Anthropometric Outcomes

Anthropometric outcomes including BMI and WHR were found to be modestly affected by YT intervention provided in the studies included in meta-analysis. This is consistent with the findings of other studies15,17,19,23 which assessed the effect of YT intervention and reported slight reduction in BMI and WHR of participants. This may be due to presence of heterogeneity in baseline anthropometric parameters of included participants across studies. Only one clinical trial reported significant reduction in BMI (p < .001) of study participants after 3 months of YT intervention. 22

Quality of Life Outcomes

Both studies included in meta-analysis \reported significant improvement in quality of life as measured by level of anxiety or depression. A study which evaluated the effect of 4 months of YT intervention along with brisk walking on PCOS risk reduction also reported similar finding. 15 Similarly, a clinical trial reported significant change in level of depression (p < .01) among study participants after 1 month of YT intervention. 24 Also, a RCT reported significant decrease in level of anxiety and depression (p < .001) in females with PCOS after 3 months of YT along with Ayurveda treatment. 19 Similar findings were reported in latest Cochrane review 20 which suggests that lifestyle intervention may improve quality of life scores in the domains of emotions and infertility in women with PCOS. This is consistent with the clinical consensus recommendations ESHRE-2018 guidelines 1 that lifestyle interventions could include behavioral strategies to optimize weight management, healthy lifestyle, and emotional well-being in women with PCOS.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis add to the knowledge about effects of YT on health outcomes of women with PCOS. YT encompasses all domains of lifestyle modification, that is, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications. Published reviews on the effect of lifestyle modification on PCOS also include studies with YT as an intervention, but the need for this systematic review is supported by the fact that sufficient number of research studies have been published which exclusively assess the effect of YT on PCOS. Hence, to the best of author(s)’ knowledge, this study is the first and most updated and comprehensive data analysis on this topic.

This review is, however, limited by the fact that only two RCTs could be included in meta-analysis as inclusion of other non-RCT studies could result in high heterogeneity in results due to varying study designs. The sample size of both included studies was not large enough and the participants could not be blinded due to intervention characteristics. However, the objective outcomes including menstrual cycles, clinical hyperandrogenism, FBG, FI, HOMA-IR, BMI, and WHR were unaffected by the lack of blinding of participants.

Research Recommendations

More well-designed randomized clinical trials for participants of varied age groups with diverse control group interventions, sufficient sample size, and longer follow-up duration need to be conducted to assess the efficacy of YT as a form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatment for PCOS. As hormonal profile varies considerably among women of different age groups, efficacy of YT intervention should be assessed likewise. For development of standard YT intervention pertaining to a specific health problem, studies of differing duration with variety of YT interventions comprising a combination of asana (physical posture), pranayama (breathing exercise) and dhyana (meditation technique) will apprise the development of clinical guidelines relating to the use of YT as treatment for a range of reproductive health problems.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis, YT may have beneficial effects on some reproductive (menstrual cycle regularity and clinical hyperandrogenism), metabolic (FBG, FI, and HOMA-IR), and anthropometric (BMI and WHR) health outcomes in women suffering from PCOS. Effect of YT on other health outcomes of women with PCOS could not be assessed due to insufficient number of studies. Based on these preliminary results, YT may be suggested as a safer and affordable form of CAM treatment for PCOS. Further, more clinical trials are warranted in order to strengthen the therapeutic role of YT for PCOS.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ajl-10.1177_15598276211029221 for Effect of Yoga Therapy on Health Outcomes in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Anita Verma, Vikas Upadhyay and Vartika Saxena in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine

Author Contributions: AV and VS were involved in defining research question and the study design of the review. AV and VU were involved in conducting search strategy and assessing eligibility of studies for inclusion. AV, VU, and VS were involved in extracting and analyzing data, assessing quality of studies, drafting manuscript, and critical discussion. All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Anita Verma https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6250-2335

Vikas Upadhyay https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5074-1494

References

- 1.Teede H, Misso M, Costello M, et al. International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(3):364-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anagnostis P, Tarlatzis BC, Kauffman RP. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: Long-term metabolic consequences. Metabolism. 2018;86:33-43. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neven A, Laven J, Teede H, Boyle J. A summary on polycystic ovary syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, prevalence, clinical manifestations, and management according to the latest international guidelines. Semin Reprod Med. 2018;36(1):005-012. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deeks AA, Gibson-Helm ME, Paul E, Teede HJ. Is having polycystic ovary syndrome a predictor of poor psychological function including anxiety and depression? Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1399-1407. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: A complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sat Bir K, Cohen L, McCall Timothy TS. The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care. 1st ed. Scotland, UK: Handspring Publishing Limited; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software] . 2020. gradepro.org.

- 11.Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Amritanshu R. Effect of yoga program on quality of life in adolescent polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized control trial. Appl Res Qual Life. 2013;8(3):373-383. doi: 10.1007/s11482-012-9191-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Ram A. Effect of a yoga program on glucose metabolism and blood lipid levels in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):37-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Amritanshu R. Effects of a holistic yoga program on endocrine parameters in adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Alternative Compl Med. 2013;19(2):153-160. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel V, Menezes H, Menezes C, Bouwer S, Bostick-Smith CA, Speelman DL. Regular mindful yoga practice as a method to improve androgen levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, controlled trial. J Osteopath Med. 2020;120(5):323-335. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2020.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvaraj V, Vanitha J, Dhanaraj FM, Sekar P, Babu AR. Impact of yoga and exercises on polycystic ovarian syndrome risk among adolescent schoolgirls in South India. Health Science Reports. 2020;3(4):e212. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahrami H, Mohseni M, Amini LKZ. The effect of six weeks yoga exercises on quality of life in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2019;22(5):18-26. http://ijogi.mums.ac.ir/article_13578.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shalini B, Mirunaleni P, Suresh K, Sundharam MM, Banumathi V. The effect of Siddha Internal Medicine with Asanam & Varmam on Sinaipaineerkatti (PCOS)-a case series. World J Pharm Res. 2019;8(2):1122-1129. doi: 10.20959/wjpr20192-14112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanthi S, Perumal K. Kayakalpa yoga, a treasure hunt for women with PCOS and infertility: a pilot trial. Res Rev A J Unani, Siddha Homeopath. 2015;1(3):12-23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao V, Metri K, Rao SNR. Improvement in biochemical and psychopathologies in women having PCOS through yoga combined with herbal detoxification. J Stem Cells. 2018;13(4):213-222. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim SS, Hutchison SK, Van Ryswyk E, Norman RJ, Teede HJ, Moran LJ. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD007506. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007506.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma A, Gandhi A, Gautam S, Biswas R, Jain AMS. Effect of yoga on insulin resistance in PCOS patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;61(5):193-194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanitha A, Pandiaraja M, Maheshkumar KVS. Effect of yoga nidra on resting cardiovascular parameters in polycystic ovarian syndrome women. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;8(9):1505. doi: 10.5455/njppp.2018.8.0411112082018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratnakumari M, Manavalan N, Sathyanath D, Ayda Y, Reka K. Study to evaluate the changes in polycystic ovarian morphology after naturopathic and yogic interventions Int J Yoga. 2018;11(2):139-147. doi: 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sode JA, Bhardwaj MA. Effect of yoga on level of depression among females suffering from polycystic ovarian syndrome. Int J Arts Manag Humanit. 2017;6(2):178-181. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7154/c114c4eccbf04f2a0444b88b789c1423b77d.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ajl-10.1177_15598276211029221 for Effect of Yoga Therapy on Health Outcomes in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Anita Verma, Vikas Upadhyay and Vartika Saxena in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine