Abstract

Emotional and behavioral variability are unifying characteristics of borderline personality disorder (BPD). Ambulatory assessment (AA) has been used to assess and quantify this variability in terms of the categorical BPD diagnosis, but growing evidence suggests that BPD instead reflects general personality pathology. This study aimed to clarify the conceptualization of BPD by mapping indices of variability in affect, interpersonal behavior, and perceptions of others onto general and specific dimensions of personality pathology. We studied a sample of participants that met diagnostic criteria for BPD (n=129) and healthy controls (n=47) who reported on their interactions throughout the day during a 21-day AA protocol. Multi-level structural equation modeling was used to examine associations between shared and specific variance in maladaptive traits with dynamic patterns of interpersonal functioning. We found that variability is an indicator of shared trait variance and Negative Affectivity, not any other specific traits, reinforcing the idea BPD is best understood as general personality pathology.

Core symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) are traditionally viewed as vacillating between idealization and devaluation of others, heightened reactivity to perceived interpersonal slights, and engaging in maladaptive behaviors to cope with overwhelming emotions. What unifies these symptoms is temporal variability, or intense, rapid shifts in thought, behavior, and affect in response to internal and external cues, particularly in interpersonal contexts (Schmideberg, 1959). Across clinical theories, variability is a defining indicator of the dysfunctional processes presumed to underlie borderline pathology (e.g., unstable cognitive representations of self and other, emotion dysregulation, unintegrated identity, attachment insecurity; Bateman & Fonagy, 2004; Bender et al., 2011; Clarkin et al., 2006; Linehan, 1993)

Until relatively recently, measurement of the processes proposed by clinical theories have relied on cross-sectional data that fails to capture the dynamic and contextualized nature of variability. Ambulatory assessment (AA), which often involves repeated self-reports over the course of a day or week, has advanced our understanding of these processes by measuring experiences as they unfold across time and contexts. With AA, it is possible to estimate an individual’s average behavior or affect as well as how much their behavior or affect fluctuates from occasion-to-occasion. Thus, unlike cross-sectional measures, AA enables direct quantification of variability across time and across naturalistic contexts.

Accordingly, AA has been used extensively to study BPD. It has been found that BPD and other mood disorder pathologies are associated with similar average levels of negative affect, but BPD is distinguished by more variability in affect compared to other clinical groups (Houben et al., 2015; Houben & Kuppens, 2020; Jahng et al., 2011; Mniemne et al., 2018; Scheiderer, et al., 2016; Trull et al., 2008) or non-clinical groups (Ebner-Priemer, 2007; Hepp et al., 2018; Santagelo et al., 2017). BPD groups have also been associated with more variability in interpersonal behavior (Russell et al., 2007) and self-esteem compared to non-clinical controls (Santangelo et al., 2017). However, other studies have found no differences in affective variability between patients diagnosed with BPD compared to those diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder or bulimia (Kockler et al., 2017; Santangelo et al., 2014; 2016). It has also been found that affect and self-esteem variability in individuals with and without a BPD diagnosis are predicted by the transdiagnostic personality traits and dimensional BPD measures (Hepp et al. 2016; Zeigler-Hill & Abraham, 2006; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2015) and a growing literature shows elevated variability in a range of diagnostic groups (Crowe et al., 2019; Farmer & Kashdan, 2014; Kashdan et al., 2006; Lamers et al., 2018; Sperry & Kwapil, 2019) suggesting it may be a general, transdiagnostic indicator of pathology.

One possible reason research has failed to find a specific link between BPD and variability is that this work has been on the categorical diagnosis. The AA literature has yet to incorporate another major development in the measurement and conceptualization of BPD: dimensional models that distinguish general and specific features of personality pathology. The nearly exclusive focus on the DSM-defined BPD is limiting because the diagnosis is highly heterogenous in clinical presentation and it is more often than not “comorbid” with other disorders (Stinson et al., 2008) making it an imprecise target for linking to pathological processes. Instead, a growing body of research shows that continuous dimensions may be a better match to how personality pathology manifests empirically. Much of this evidence comes from factor analytic work that consistently finds personality disorder symptoms reflect approximately five transdiagnostic traits (e.g., Antagonism, Detachment, Disinhibition, Negative Affectivity, and Psychoticism; Kotov et al., 2017; Krueger, 2012; O’Connor, 2005; Widiger & Simonsen, 2005).

Although these traits represent relatively distinct maladaptive patterns of functioning, there is substantial shared variance among them (Krueger & Markon, 2014). Conceptually, that this general factor encompasses what personality disorder symptoms share aligns with theoretical models that propose a core dysfunction underlying all personality pathology (Livesley & Jang, 2000; Kernberg, 1984; Pincus, 2005)—and evidence suggests that the interpersonal and emotional difficulties characteristic of BPD reflect this dysfunction. For instance, when personality disorder symptoms are statistically partitioned into general and specific variance, BPD criteria exclusively indicate general personality pathology (Ringwald et al., 2019, Sharp et al., 2015; Williams, Scalco, & Simms, 2018; Wright et al., 2016). At the same time, it has been shown that despite diversity in clinical presentation, BPD criteria cohere into a unidimensional construct (Clifton & Pilkonis, 2007; Hallquist & Pilkonis, 2012; Huprich et al., 2015; Wright, 2017). These findings support the possibility borderline pathology reflects a continuum of personality impairment that cuts across diagnoses, and thus is distinguished by degree of dysfunction rather than kind (Bender & Skodol, 2007; Bornstein, 1998).

Although this structural work showing correspondence between BPD and general personality pathology suggests they reflect the same pathological processes, cross-sectional research cannot directly test this idea. AA, however, is an ideal approach to clarify the extent to which everyday patterns of functioning that characterize borderline pathology (i.e., those indicated by variability) are also related to general or specific dimensions of personality pathology. Prior AA work has shown that maladaptive traits associate with increased variability in personality disorder symptoms (Roche et al., 2016; Wright & Simms, 2016), but only one study disentangled their shared and specific variance to investigate associations with general pathology (Ringwald et al, 2020). In this previous study, we found that affective and interpersonal variability was differentially associated with trait-specific variance and general personality pathology. These results suggest that the variability thought to define BPD are indicators of both general and specific pathological processes; however, the non-clinical samples used in our study precluded direct implications for BPD.

The current study replicates and extends our previous work by mapping key indicators of borderline pathology onto transdiagnostic dimensions in a sample enriched with people meeting DSM criteria for BPD. By making more direct connections between variability, dimensional models, and BPD we aimed to produce results with greater clinical relevance to complement our findings in student and community samples. Building on a largely cross-sectional evidence base suggesting BPD aligns with general personality pathology, we examined whether the dynamic patterns of behaviors, emotions, and perception of others thought to define borderline pathology similarly align with the general factor.

All hypotheses and analyses were pre-registered and can be found on the Open Science Framework along with all supplementary materials (OSF; https://osf.io/5phwv/).1 A number of hypotheses follow from the large number of associations we investigated, but for the purpose of the current study, we detail only those related to our principal goal of evaluating how processes of borderline pathology relate to general and specific dimensions. We hypothesized that emotional and interpersonal problems implicated in BPD reflect general personality pathology that cuts across traits; thus, we expected that general personality pathology would be associated with more negative affect and less positive affect during social interactions, a tendency to express more hostility and perceive others as being more hostile, as well as more variability in affect and interpersonal behavior. Additionally, we hypothesized that maladaptive traits have unique features, so we expected they would have some associations with interpersonal patterns over and above general pathology.

Methods

Participants

This sample consists of a subsample of participants drawn from a longitudinal study examining suicidal behavior in relation to BPD. Participants for the study were recruited from inpatient and outpatient clinics as well as from the surrounding community by advertisement. Data collection began in 1990 and ended in 2020. At enrollment, participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 45. Exclusion criteria included lifetime diagnosis of any psychotic or bipolar disorder, clinical evidence of organic brain disease, physical disorders or treatments with known psychiatric consequence (e.g., lupus, steroids), and IQ < 70. More detailed description of the parent study protocol has been reported elsewhere (Soloff et al., 2017).

Participants were recruited to be part of a BPD group or a healthy control group. The diagnosis of BPD was determined by standardized semi-structured diagnostic interviews conducted by masters-level research clinicians. For inclusion, participants had to meet probable or definite lifetime diagnosis determined by the International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE; Loranger et al., 1994). Diagnoses were confirmed in a consensus conference by raters and two research psychiatrists using all available data, including medical records where available. Participants recruited as part of the healthy control group were required to have no lifetime Axis I or II diagnoses determined by the IPDE or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, respectively. For the purpose of the current investigation, participants were pooled to represent a range of symptom severity consistent with a dimensional conceptualization of personality functioning (Stanton et al., 2020).

A subsample of participants completed an AA protocol (N = 197). To increase the statistical reliability of our AA measurements, we excluded participants that reported fewer than ten interactions over the course of the study (i.e., our pre-registered threshold of minimum observations per person needed to obtain reliable estimates of each individual’s interaction patterns; n = 14). Because we included gender as a covariate in every model, participants who reported their gender as transgender or “other” were also excluded (n = 7) as we could not statistically account for a category that small.2 As a result, the final sample size used in our analyses was 176 (n = 129 diagnosed with BPD).3 Most participants in the BPD group also met criteria for other DSM diagnoses, with the most common being major depression (n = 111 met criteria), alcohol use disorder (n = 69), and generalized anxiety disorder (n = 67; complete diagnostic frequencies are reported in the supplement). The sample was mostly female (83%) and white (72%) with a mean age of 32.4 (SD = 9.6).

Procedure

All participants completed a baseline assessment battery including clinical interviews and self-report questionnaires adapted from the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior (see Soloff et al. [2005] for a full description of measures). Self-reported maladaptive traits were assessed in 2017 when the AA protocol was introduced.

The 21-day AA protocol was completed using a smartphone provided by the study. Participants were compensated $40 for the initial set-up and training. If they completed over 75% of the AA surveys in the first week, they received an additional $30, $40 for the second week, and $65 for the third week. Six randomly initiated surveys were delivered each day by push notifications administered through the MetricWire smartphone application (MetricWire, Inc., 2019). In each survey, participants indicated whether an interpersonal interaction lasting more than ten minutes had occurred since the last prompt. Because participants received six surveys per day, there would typically be no more than a few hours in between the interaction and the report. When interaction(s) had occurred, participants were instructed to report on the “most impactful” interaction and rated their own affect and behaviors and the behaviors of the person they interacted with. If an interaction was not reported, participants answered a different survey about mood and non-interpersonal stressors. For this study, only reports from the interaction condition will be used.4 The average number of surveys completed per participant was 49 (SD = 24.6). A total of 8,646 interactions were included in the final analyses.

Measures

Personality pathology.

Maladaptive traits were assessed using The Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 provided by the American Psychiatric Association (PID-5; Krueger et al., 2012). The PID-5 is comprised of 220 items rated on a Likert scale (0—Very False/ Often False; 1 – Sometimes/ Somewhat False; 2—Sometimes/ Somewhat True; 3—Very True or Often True). Items were averaged to produce dimensional scores for 25 narrow trait facets. Corresponding facets (three per trait) are averaged to assess broader trait domains of Negative Affect (Emotional Lability, Anxiousness, Separation Insecurity; ω = .90), Detachment (Withdrawal, Anhedonia, Intimacy Avoidance; ω = .77), Antagonism (Manipulativeness, Deceitfulness, Grandiosity; ω = .86), Disinhibition (Irresponsibility, Impulsivity, Distractibility; ω = .88), and Psychoticism (Unusual Beliefs, Eccentricity, Perceptual Dysregulation; ω = .88).

Momentary affect.

Affect during interactions was measured using emotion adjectives derived from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark & Tellegen, 1988). Questions were adapted for momentary measurement and asked: “How ADJECTIVE did you feel during this interaction?”). Each adjective was rated on a Likert scale (1 – Very Slightly or Not at all, 2 – A Little; 3 – Moderately; 4 – Quite a Bit; 5 – A great deal). The adjectives Angry, Nervous, Sad, and Irritated were averaged for each interaction to assess negative affect (ωwithin-person = .74, ωbetween-person = .91), and positive affect was measured by the mean of the adjectives Happy, Excited, and Content (ωwithin-person = .85, ωbetween-person = .89).

Momentary interpersonal behavior.

Following each interaction, participants reported on their own behavior and behavior of the person they interacted with. The question prompts were: “Please rate YOUR BEHAVIOR toward the other person during the interaction” or “Please rate how the OTHER PERSON BEHAVED toward you during the interaction.” For both self and other, Dominance (“Accommodating/Submissive/Timid” to “Assertive/Dominant/Controlling”) and Warmth (“Cold/Distant/Hostile” to “Warm/Friendly/Caring”) were rated on 101-point slider scales (−50 to +50). These items correspond to two, broad dimensions of interpersonal behavior covering a comprehensive range of personality disorder symptoms (Wilson et al., 2017).

Analytic Plan

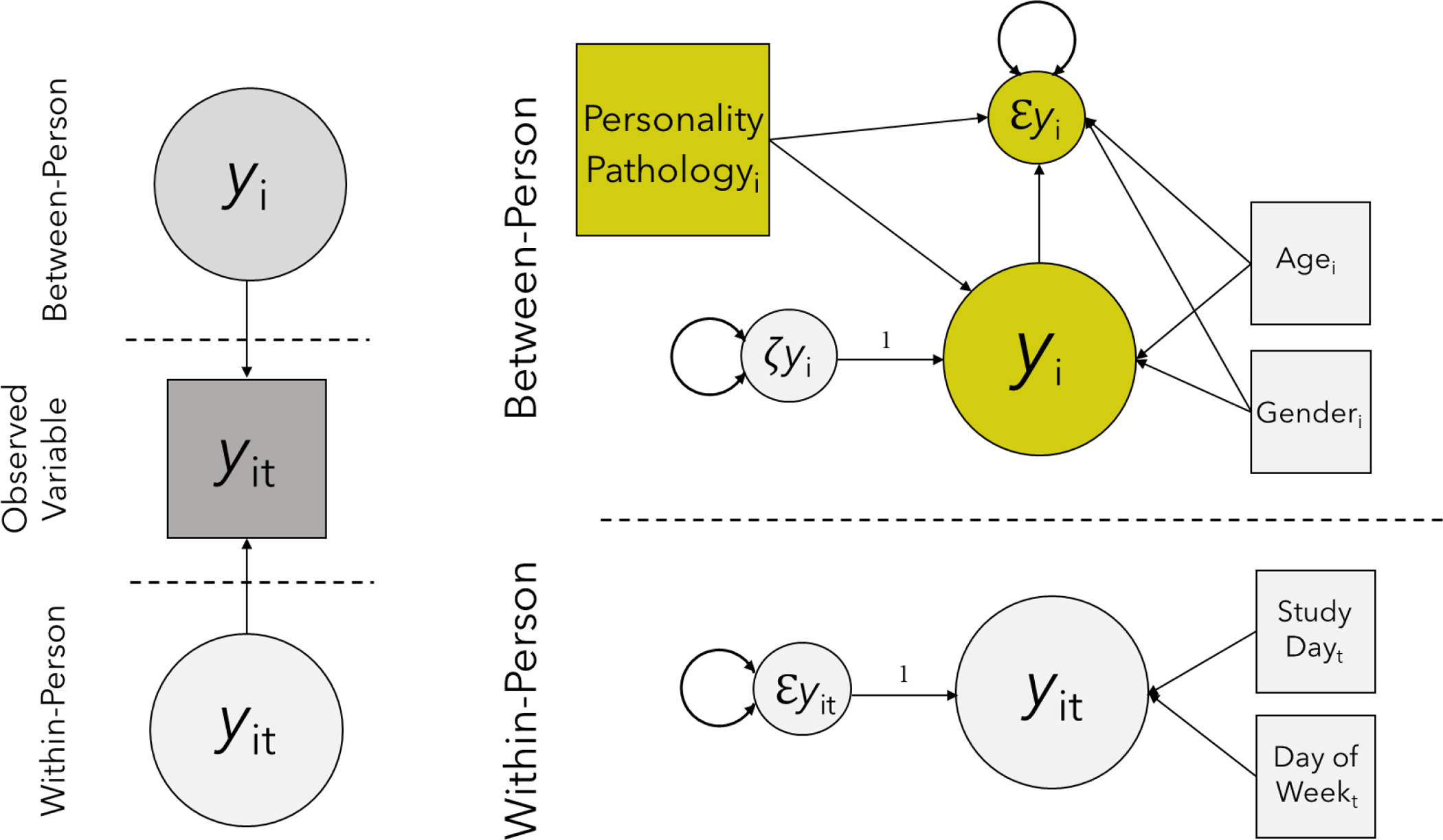

All analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Figure 1 depicts the models used in this study, and model syntax is provided on OSF.

Figure 1.

Diagram of multi-level structural equation models used for analysis

Note. The left panel shows the latent decomposition of observed variables y into within person (yit) and between-person (yi) variance for individual i during interaction t. The right panel shows the model used for all analyses. Single-headed arrows represent regression paths, double headed arrows represent variances. Circles indicate latent variables and squares are observed variables. Note that the predictor, Personality Pathologyi, is shown as an observed variable but in the general personality pathology models it is a latent variable. ℇyi reflects individual differences in within-person variance, and yi is the estimate of an individual’s average. 𝜁yi represents variance in yi not accounted for by predictors in the model.

Multi-level structural equation modeling (MSEM) was used to accommodate the nested structure of the data (i.e., interactions nested within participants). Using MSEM, total variance in the observed measures of affect, interpersonal behavior, and perception during interactions was decomposed into within- and between-person latent variables. That is, each momentary variable was partitioned into a random intercept capturing individual differences in average endorsement (Level 2), and departures from individual averages during a given situation (Level 1). This is similar to calculating person means (Level 2) and then person-mean centering the momentary variables as is often done in standard multi-level modeling, except the partitioning is estimated as part of the model and not done manually (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2019; Lüdtke et al., 2008). To investigate cross-situational variability, the residual variances of the within-person part of the variables (Level 1), which are usually assumed to be homogeneous across people, were modeled as a random effect (i.e., allowing individual differences in variability or heterogeneous variances across people). These residuals reflect how much an individual tends to fluctuate from their average from situation-to-situation. With latent decomposition in MSEM, individual differences in these residuals become a variable at the between-person level (Level 2) allowing us to examine trait predictors of variability in addition to person-specific means. This latent variable approach to modeling variability is an alternative to more commonly used measures like the mean squared of successive differences (MSSD). The MSSD compares adjacent observations and so only indexes sequential variation whereas the approach we used is time-unstructured enabling detection of a broader pattern of fluctuations from an individual’s baseline. In exploratory (not pre-registered) models, we repeated our analyses using the MSSD to measure variability for comparison to our primary results.

Bayesian estimation was used because it allows residual variances of variables at the within-person level to be modeled as random effects. No prior information about parameter values were specified (i.e., non-informative priors that are the default in Mplus were used). Inferences were made from point estimates drawn from their posterior distribution and associated 95% credibility intervals. We considered coefficients in which the credibility interval did not include zero to be significantly different from zero. Data was considered missing at random and was modeled using Bayesian estimation, which is a full information method that uses all available data, similar to full information maximum likelihood estimation. This approach asymptotically provides the same results as full information maximum likelihood (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2010). There were ten participants with incomplete trait data and 36 observations (i.e., AA surveys) missing data on either interpersonal behavior or affect.

In the first set of models, to provide a basis of comparison for models separating shared and specific variance, we examined bivariate associations between maladaptive traits and average affect, interpersonal behavior, and perception, as well as variability in these variables adjusting only for gender and age. In these models, the random intercept (i.e., average level) and within-person residual variance (i.e., degree of variability) for the AA variables were regressed on each trait. Next, all traits were entered simultaneously as covariates to estimate specific associations with each AA variable’s average and variability. Finally, to evaluate associations with general personality pathology, each AA variable’s random intercept and residual variance was regressed on a latent variable estimated from the shared variance among traits. In every model, the within-person residuals (i.e., individual differences in variability) were also regressed on the random intercept (i.e., average level) to adjust for their statistical dependency.

To account for differences in affect and social behavior on the weekend versus the weekday, all within-person variables were regressed on the day of week an interaction occurred. Day of week was coded as a binary variable with zero representing weekday and one representing weekend. Within-person variables were also adjusted for when in the study an interaction occurred to account for potential anchoring or fatigue effects. Time in study was indexed by the average duration of the AA protocol in hours (24 hours × 21 days) and centered at the mid-point of the study so that the random intercept for within-person variables could be interpreted as the person’s average levels on weekdays.

MSEM with Bayesian estimation and random effects does not provide traditional global model fit indices. Because the models without a latent personality pathology variable are fully saturated (i.e., df = 0), in a maximum likelihood framework without random effects these models would have perfect fit. A separate model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation to obtain fit indices for the latent general personality pathology variable.

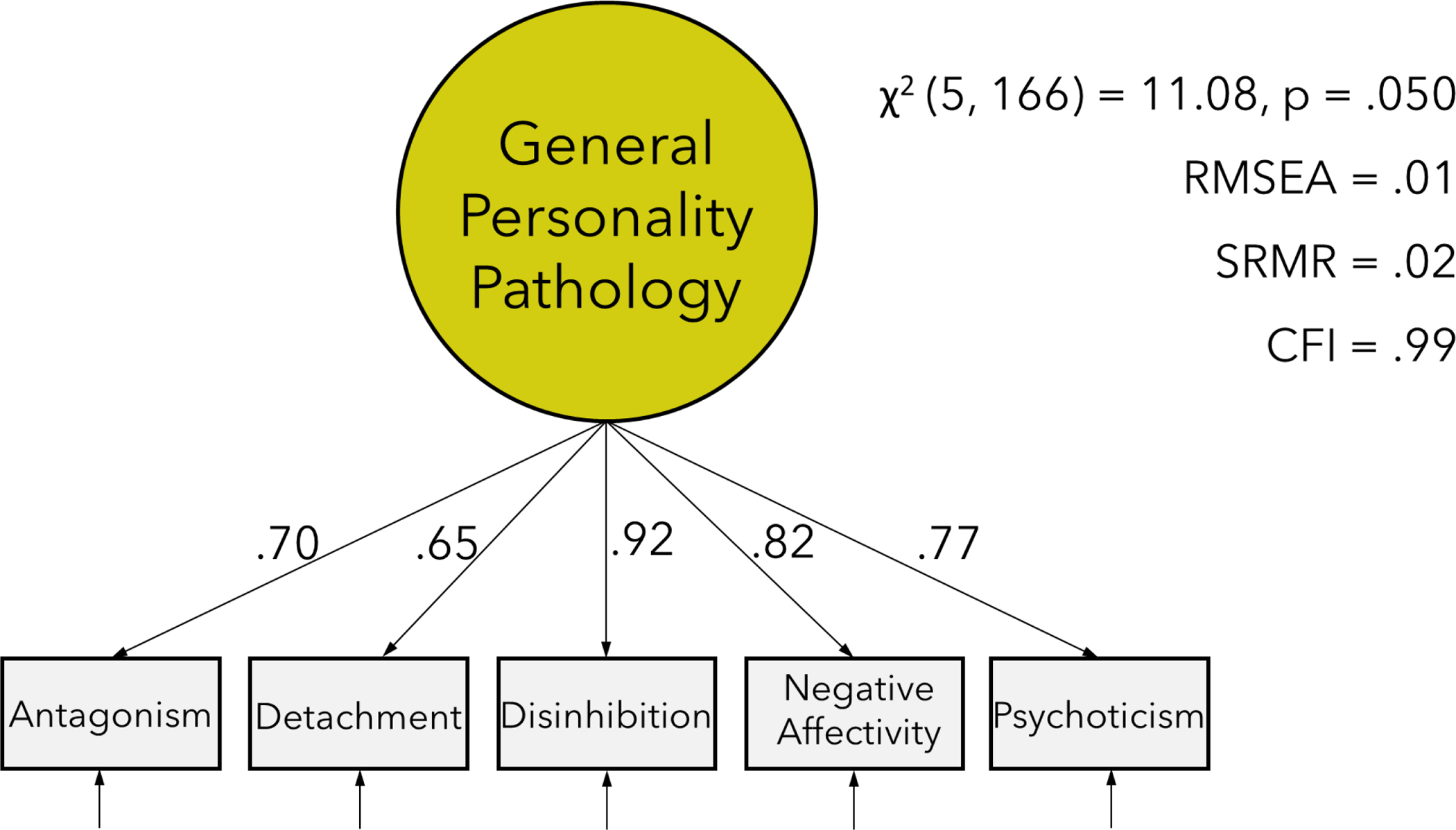

Results

Results from the bivariate models are presented in Table 1a. Shared and specific interpersonal patterns associated with traits are in Table 1b. Figure 2 shows the factor loadings and global fit statistics for the general personality pathology variable. All factor loadings were significant, and fit indices indicated good model fit.

Table 1.

Associations between momentary interpersonal variables and maladaptive traits

| a. Bivariate trait associations | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Averages | Variability | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Personality Pathology Meas. | NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other | NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Antagonism | .41 (.28, .53) | −.13 (−.26, .05) | −.06 (−.20, .08) | −.14 (−.29, .04) | .09 (−.09, .26) | −.11 (−.27, .03) | .26 (.15, .38) | .23 (.09, .39) | .27 (.07, .42) | .28 (.13, .43) | .39 (.21, .53) | .23 (.07, .36) |

| Detachment | .54 (.44, .64) | −.51 (−.62, −.38) | −.04 (−.20, .14) | −.29 (−.44, −.14) | .08 (−.08, .25) | −.24 (−.41, −.07) | .26 (.12, .38) | .15 (−.05, .34) | .25 (.09, .41) | .26 (.11, .39) | .28 (.10, .48) | .25 (.10, .40) |

| Disinhibition | .53 (.41, .62) | −.21 (−.35, −.07) | −.15 (−.29, −.02) | −.12 (−.27, .03) | .00 (−.17, .19) | −.11 (−.25, .06) | .33 (.19, .44) | .24 (.09, .39) | .32 (.04, .48) | .35 (.23, .50) | .46 (.30, .59) | .25 (−.08, .46) |

| Negative Aff. | .63 (.50, .70) | −.34 (−.47, −.21) | −.05 (−.22, .11) | −.19 (−.33, −.03) | .12 (−.06, .27) | −.15 (−.29, .01) | .45 (.33, .58) | .31 (.16, .46) | .32 (.09, .48) | .44 (.25, .56) | .45 (.28, .58) | .37 (.25, .50) |

| Psychoticism | .45 (.29, .56) | −.20 (−.36, −.06) | −.08 (−.23, .06) | −.14 (−.28, .03) | .06 (−.12, .22) | −.09 (−.24, .06) | .21 (.07, .33) | .25 (.10, .38) | .21 (.01, .36) | .15 (−.10, .36) | .31 (.12, .46) | .18 (−.10, .39) |

| b. Trait-specific associations | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Averages | Variability | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Personality Pathology Meas. | NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other | NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Antagonism | .04 (−.15, .19) | .06 (−.14, .23) | .07 (−.14, .26) | −.08 (−.28, .12) | .11 (−.08, .30) | −.09 (−.28, .14) | .07 (−.10, .24) | .04 (−.15, .22) | .09 (−.12, .28) | .02 (−.16, .26) | .16 (−.11, .37) | −.04 (−.24, .15) |

| Detachment | .27 (.09, .41) | −.48 (−.61, −.32) | .07 (−.16, .25) | −.31 (−.48, −.10) | .08 (−.09, .28) | −.27 (−.46, −.04) | .15 (−.01, .30) | −.07 (−.26, .11) | −.03 (−.24, .18) | −.06 (−.24, .17) | .14 (−.14, .41) | −.05 (−.23, .14) |

| Disinhibition | .04 (−.17, .23) | .15 (−.09, .36) | −.29 (−.51, −.02) | .22 (−.03, .43) | −.29 (−.51, −.04) | .15 (−.11, .40) | .02 (−.19, .23) | −.03 (−.21, .17) | .19 (−.07, .46) | .06 (−.17, .29) | .07 (−.25, .51) | .19 (−.06, .46) |

| Negative Aff. | .46 (.28, .62) | −.23 (−.44, −.03) | .11 (−.15, .34) | −.12 (−.34, .11) | .21 (−.02, .39) | −.08 (−.32, .16) | .40 (.27, .57) | .27 (.03, .50) | .23 (−.05, .43) | .40 (.18, .58) | .13 (−.24, .50) | .22 (.00, .46) |

| Psychoticism | .01 (−.18, .21) | .09 (−.13, .25) | −.04 (−.28, .16) | .03 (−.16, .24) | .01 (−.19, .22) | .05 (−.19, .26) | −.04 (−.21, .11) | .11 (−.05, .25) | −.02 (−.22, .18) | .02 (−.19, .20) | −.15 (−.39, .08) | .04 (−.16, .21) |

| c. Associations with shared variance | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Averages | Variability | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other | NA | PA | Dom | Warm | Dom Other | Warm Other | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| General PP. | .63 (.51, .72) | −.30 (−.44, −.13) | −.14 (−.28, .05) | −.18 (−.33, −.03) | .05 (−.11, .21) | −.13 (−.31, .03) | .47 (.34, .59) | .30 (.16, .45) | .43 (.28, .55) | .43 (.29, .56) | .53 (.34, .65) | .38 (.24, .50) |

Note. Table 1a presents bivariate associations with each trait from models including each trait as an independent predictor; Table 1b presents specific associations with each trait adjusted for shared variance with the other traits from models including all traits as covariates; Table 1c presents associations with general personality pathology (GPP; i.e., a latent variable estimated from shared variance between maladaptive traits). Random intercepts at the between-person level were used to estimate average levels and the within-person residual variances were used to estimate variability. Within-person variability was adjusted for average levels by regressing the residuals on the random intercepts. Associations with averages and variability for each momentary construct were estimated in the same models. All models include age and gender as covariates. Point estimates are standardized regression coefficients; 95% credibility interval presented in parenthesis; bolded values indicate credibility interval does not contain zero. Dom = self dominant behavior; Warm = self warm behavior; Dom Other = perception of other’s dominance; Warm Other = perception of other’s warmth; NA = negative affect; PA = positive affect; Traits measured by Personality Inventory for DSM-5.

Figure 2.

Latent variable model of general personality pathology

Note. Maladaptive traits were measured using the Personality Inventory for DSM-5. Model was estimated using only participants with complete trait data (n = 166). Traits are adjusted for age and gender. Factor loadings are standardized values. RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual.

Exploratory Analyses

To reinforce the link between general personality pathology and BPD and lay the groundwork for our primary analyses, we conducted exploratory analyses that were not pre-registered. Note, however, these were decided upon and conducted after the pre-registration. We first conceptually replicated previous research on categorical BPD by establishing associations between clinician and self-rated dimensional BPD measures and momentary affect and interpersonal functioning. Clinician-rated, dimensional scores of borderline personality disorder criteria (i.e., sum of criteria scored from 0-absent, 1-probable, and 2-definite) were derived from the IPDE, and self-reported borderline personality disorder symptoms were derived from the Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline features (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991). Consistent with prior studies, we found that higher levels of BPD features were associated with more negative affect, less positive affect, and more hostile (i.e., less warm) behavior on average as well as more variability in all affective and interpersonal variables.

We then confirmed the association between BPD and general personality pathology which has been found in previous structural research by showing that general personality pathology (i.e., the shared variance between traits) was strongly correlated with both measures of BPD (rIPDE = .86; rPAI-BOR = .97). These results can be found in the supplementary material.

General Personality Pathology Associations

Having replicated associations between BPD and AA measures of affective and interpersonal functioning, and cross-sectional associations between BPD and general personality pathology in this sample, our primary analyses examined the correspondence between momentary manifestations of general personality pathology and BPD. The pattern of associations with general personality pathology was nearly identical to those found in the exploratory BPD models. As hypothesized, general personality pathology was associated with more negative affect, less positive affect, and more hostile behavior on average in interpersonal situations. It was also strongly associated with more variability in all affective and interpersonal variables.

Bivariate and Trait-Specific Associations

Finally, we examined associations between the momentary variables and maladaptive traits. In the bivariate models, almost every trait was associated with higher average negative affect and lower average positive affect across situations as well as more variability in affect, interpersonal behavior, and perception. Detachment and Negative Affectivity were further associated with less warm behavior on average, with Detachment additionally associated with less perceived warmth. Disinhibition was associated with less dominant behavior.

After adjusting for general pathology, most associations between traits and average affect became non-significant. The exceptions were Detachment and Negative Affectivity, which remained associated with average levels of affect, but these effects were moderately to substantially attenuated. The negative association between Negative Affectivity and warm behavior became non-significant. In contrast, negative associations of dominant behavior and perceived dominance with Disinhibition increased in magnitude indicating a suppression effect.

Most distinguishing between general and specific pathologies were the associations with variability. After adjusting for general personality pathology, 23 out of these 26 associations with variability became non-significant. Only Negative Affectivity was associated with more variability in affect and warm behavior over and above general personality pathology.

We also repeated our pre-registered analyses using the MSSD to measure variability instead of residual variances to allow for comparison to this more commonly used index. There were no substantive differences between results using either method. These results are reported in the supplementary materials.

Discussion

This study replicated previous AA research showing BPD is associated with variability and cross-sectional and retrospective studies that find BPD symptoms relate to general personality pathology, but we took an additional step towards clarifying the conceptualization of borderline pathology by showing patterns of everyday affective and interpersonal functioning associated with BPD were nearly identical to those associated with general personality pathology. Our results are consistent with clinical theories that propose borderline pathology captures the continuum of dysfunction underlying all forms of personality disorders (Kernberg, 1987) and by directly linking the clinically relevant, everyday manifestations of BPD and general personality pathology, we can build on BPD-related theory and research to understand the nature of that dysfunction.

In line with previous research showing that no single interpersonal style describes BPD (Hopwood & Morey, 2007; Wright et al., 2013; cf. Wilson et al., 2017), we found that both BPD and general personality pathology were not associated with average behavior or perception of others besides less overall warmth. Interpersonal and affective variability, on the other hand, were strong, clear indicators of BPD and general personality pathology in our study. Variability across domains and emotional valences, in turn, may be indicative of pathological interpersonal processes.

The associations between general personality pathology and variability in warm behavior and perceived warmth in others shown in this study are consistent with oscillations between craving closeness and angry disengagement, and between viewing others as caring in one moment and rejecting in the next (Stern, 1938). Associations with variability in dominant behavior and perceived dominance may be indicative of difficulties with agency involving shifts between being dependent and controlling as well as sensitivity to perceived social status of others. General personality pathology was also characterized by interactions with more negative affect and less positive affect overall, as well as more affective variability in line with dysregulated emotional responses to interpersonal situations. Each of these pathological processes suggested by variability have been typically viewed as BPD-specific processes, but our results suggest such emotional and interpersonal functioning is the core of personality pathology rather than being a distinct “type” of personality disorder (Hopwood et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2004).

Unlike general personality pathology, traits had unique associations with average behavior and perception beyond their shared variance, not variability, revealing relatively consistent interpersonal styles. These findings mirror research showing stability in levels of specific maladaptive trait variance (i.e., after accounting for general personality pathology) over the course of years, while general pathology tends to decline (Hopwood et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2016). Two behavioral patterns were found suggesting trait-specific difficulties in interpersonal functioning: Detachment was associated with less warmth (i.e., more coldness), whereas Disinhibition was associated with less dominance (i.e., more submissiveness). The results for Detachment have precedent in research on the trait’s dispositional interpersonal style (Girard et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2012) and make sense given the primary feature of social withdrawal. Findings for Disinhibition, on the other hand, have been mixed with some studies finding associations with submissiveness like we did (Wright & Simms, 2014) but others finding no association (Ringwald et al., 2020) or associations with higher dominance (Hopwood, Koonce, & Morey, 2009; Girard et al., 2017; Williams & Simms, 2016; Wright et al., 2012). Given the suppression effects in our study, we are hesitant to overinterpret this result, but it underscores the need for more focused research on the interpersonal expression of this trait.

Psychoticism and Antagonism did not appear to have unique interpersonal profiles. Although other work has shown Psychoticism is associated with interpersonal problems (Williams & Simms, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2012), our results also suggest that the trait-specific features are less evident in everyday interpersonal interactions. In contrast, our finding that the interpersonal and emotional variability associated with Antagonism in the bivariate models were completely accounted for by general personality pathology aligns with cross-sectional research showing antagonistic features tend to mark the general factor rather than form a specific trait (Hallquist & Wright, 2014; Ringwald et al., 2019; Sharp et al., 2015). The near redundancy of Antagonism and the general factor across studies and analytic methods further supports an interpretation of general personality pathology as impaired interpersonal functioning.

Our finding that associations between trait Negative Affectivity and interpersonal behavior and perception were almost entirely accounted for by shared variance with other traits—yet retained specific associations with affect—may bear on the question of whether personality pathology meaningfully differs from chronic mood disorders marked by trait negative emotionality (e.g., unipolar depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder; Brown & Barlow, 2009). These results suggest that pathology related to trait Negative Affectivity, net general personality pathology, is characterized by low mood and variable affect and warmth. The sample we used had considerable representation of mood pathology, but the study design did not allow us to directly test whether personality pathology and mood disorders can be differentiated by affective and interpersonal indicators; however, our results do open the possibility for this to be investigated further. This evidence for non-overlapping processes is consistent with clinical theories that posit personality pathology is distinguished, in part, by the situations which evoke the emotional responses indicated by variability; namely, interpersonal situations (Hopwood, Pincus, & Wright, 2019; Pincus & Ansell, 2003). By measuring interpersonal behavior and perception of others, our study provides insight into the most theoretically relevant aspects of borderline pathology not afforded by most of the AA literature, which has heavily prioritized affect. The only other study that has measured interpersonal variability in BPD using AA found individuals with the diagnosis reported more variability in dominance and warmth compared to healthy controls (Russell et al., 2007), consistent with our results. Our study expands on this previous work by showing that interpersonal variability reflects processes shared among different styles of personality pathology, but which are distinct from a general predisposition towards negative affect.

Interpersonal variability may be a primary, distinguishing characteristic of personality pathology, and at the same time, nearly all forms of psychopathology affect interpersonal functioning. It is likely that some of the same processes underlying variability in our sample of people enriched for BPD also contribute to interpersonal problems associated with psychopathology not traditionally considered a personality disorder. For instance, rejection sensitivity is a hallmark feature of borderline pathology possibly indicated by variability in perceived warmth, but rejection sensitivity is also associated with depression, anxiety, and body dysmorphic disorder (Gao et al., 2017). Further research is needed to differentiate between the processes indicated by interpersonal variability and whether some are specific to personality pathology. Understanding the mechanisms that influence variability, and which are overlapping versus distinct among various mental health outcomes, has implications for clinical research and practice that extend beyond personality pathology.

Another implication of the transdiagnostic interpersonal processes we found evidence for is that BPD can be a clinically useful construct if reconceptualized as general personality pathology. Instead of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, we present a bridge between the rich empirical and theoretical literatures on BPD and the dimensional models personality psychopathologists are shifting towards (Hopwood et al., 2019). BPD criteria, particularly interpersonal and affective variability, are clear indicators of the presence of personality pathology. Accurately identifying personality pathology is relevant across clinical contexts, as co-occurring personality disorders complicate first-line treatment of other psychiatric (Bank & Silk, 2001; Reich, 2003) and health problems (Moran et al., 2001). Despite its prognostic value, exhaustive evaluation of all possible manifestations of personality disorder is not feasible in most clinical settings (Tyrer, Reed, & Crawford, 2015). Alternatively, BPD symptoms conceived along a continuum of severity could provide an efficient first-stage screening. Recasting BPD as general personality pathology also suggests transdiagnostic processes that could be targeted with treatment. The most well-established therapies for personality disorder were designed for BPD, but when viewed as general personality pathology, these treatments could be applied to more patients (viz. Clarkin et al., 2006). Similarly, to the extent some processes cut across mood disorders with established treatments, these could be adapted for treatment of personality pathology. Perhaps more importantly, knowing what aspects of a patient’s personality are relatively stable and should be accommodated rather than expected to change in therapy (i.e., disentangling general dysfunction from trait style), can refine approaches to treatment planning and interventions regardless of diagnosis (Hopwood, 2018b).

There are limitations to our study that should be noted. We found fewer specific associations than in our previous study using non-clinical samples. This was likely due, in part, to loss of statistical power in the current study’s relatively smaller sample, as the effect sizes were similar but not statistically significant. Despite being a larger sample than most other AA studies of BPD, many of the coefficients hypothesized to be significant had credibility intervals that narrowly included zero (e.g., by |.03|). Another possible reason for the sparse trait-specific effects is that by using a sample enriched with borderline pathology, participants were essentially selected for general personality pathology rather than a balanced sample of each trait domain. The sample composition was advantageous for our study as it enabled direct comparison with previous BPD literature and provided a strong signal to interpret the general factor, whereas the healthy control group prevented issues related to range restriction (Stanton et al., 2020). Despite these advantages, by selecting participants along the dimension of severity rather than by style, distinct expressions of psychopathology were not well-represented. Relatedly, the evidence we found for the isomorphism of BPD and general personality pathology may be, in part, a function of the sample enriched for BPD symptoms. To comprehensively evaluate transdiagnostic associations with variability and other important, clinical outcomes, wider representation of psychopathologies will be necessary. Another limitation of our sample is that participants were primarily white and female, thus a wider representation of demographic characteristics is also needed to ensure our results generalize to other racial/ethnic groups and genders.

Our study replicated and extended prior work by directly linking the everyday patterns of emotional and interpersonal functioning associated with BPD to general personality pathology. Correspondence between key pathological processes and general and specific dimensions suggest a path forward for integrating the wealth of theoretical and empirical work on BPD into transdiagnostic models: the emotional and interpersonal dysfunction associated with borderline symptoms may be what underlies all personality pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH048463, R01MH100095, R01MH119399, R01AA026879, L30MH101760), the University of Pittsburgh’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program (UL1 TR001857). The CTSA program is led by the NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and grants from the University of Pittsburgh Central Research Development Fund and a Steven D. Manners Faculty Development Award from the University of Pittsburgh University Center for Social and Urban Research. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and not those of the funding source.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

The pre-registration included analyses in a second sample. After pre-registration, we determined that the second data set’s sampling strategy was inappropriate to test our study hypotheses and we therefore do not report these results in the paper. Full results including post-hoc analyses and explanation of our rationale for not reporting on that sample are included in the supplementary materials.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate whether inclusion of these participants counted as female or as male substantively altered our results. Effects of interest to this study differed by less than .02 when the seven participants were included.

The projected sample size reported in the pre-registration was 183. This did not account for the unanticipated decision to drop non-binary gendered participants.

Sensitivity analyses using affect reports from all surveys (not just those from the interaction condition) showed a nearly identical pattern of results and are reported in the supplement.

References

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2019). Latent variable centering of predictors and mediators in multilevel and time-series models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26(1), 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2010). Bayesian analysis using Mplus: Technical implementation. Unpublished Manuscript. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/Bayes3.pdf

- Bank PA, & Silk KR (2001). Axis I and axis II interactions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 14(2), 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, Dinu-Biringer R, Spitzer C, & Lang S (2010). Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(3), 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A & Fonagy P (2004). Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Mentalisation based treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bender DS, Morey LC, & Skodol AE (2011). Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM–5, Part I: A review of theory and methods. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 332–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender DS, & Skodol AE (2007). Borderline personality as a self–other representational disturbance. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21,500–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein RF (1998). Reconceptualizing personality disorder diagnosis in the DSM‐V: The discriminant validity challenge. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, & Yeomans FE, & Kernberg OF. (2006). Psychotherapy for borderline personality: Focusing on object relations. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton A, & Pilkonis PA (2007). Evidence for a single latent class of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders borderline personality pathology. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(1), 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe E, Daly M, Delaney L, Carroll S, & Malone KM (2019). The intra-day dynamics of affect, self-esteem, tiredness, and suicidality in major depression. Psychiatry Research, 279, 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Kleindienst N, Welch SS, Reisch T, Reinhart I, . . . Bohus M (2007). State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychological Medicine, 37(7), 961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AS, & Kashdan TB (2014). Affective and self-esteem instability in the daily lives of people with generalized social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 187–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist MN, & Pilkonis PA (2012). Refining the phenotype of borderline personality disorder: Diagnostic criteria and beyond. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3(3), 228–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist MN, & Wright AGC (2014). Mixture Modeling Methods for the Assessment of Normal and Abnormal Personality, Part I: Cross-Sectional Models. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(3), 256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepp J, Lane SP, Wycoff AM, Carpenter RW, & Trull TJ (2018). Interpersonal stressors and negative affect in individuals with borderline personality disorder and community adults in daily life: A replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(2), 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepp J, Carpenter RW, Lane SP, & Trull TJ (2016). Momentary symptoms of borderline personality disorder as a product of trait personality and social context. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(4), 384–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ (2018a). Interpersonal dynamics in personality and personality disorders. European Journal of Personality, 32(5), 499–524. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ (2018b). A framework for treating DSM‐5 alternative model for personality disorder features. Personality and Mental Health, 12(2), 107–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Wright AGC, Ansell EB, & Pincus AL (2013). The interpersonal core of personality pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(3), 270–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Malone JC, Ansell EB, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM,…Morey LC. (2011). Personality assessment in DSM–V: Empirical support for rating severity, style, and traits. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(5), 305–320. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Thomas KM, Markon KE, Wright AGC, & Krueger RF (2012). DSM-5 personality traits and DSM-IV personality disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(2), 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Pincus AL, & Wright AGC (2019). The interpersonal situation: Integrating personality assessment, case formulation, and intervention. In Samuel D & Lynam D (Eds.), Using basic personality research to inform personality pathology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, & Morey LC (2007). Psychological conflict in borderline personality as represented by inconsistent self–report item responding. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(9), 1065–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Koonce EA, & Morey LC (2009). An exploratory study of integrative personality pathology systems and the interpersonal circumplex. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 4(31), 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, & Kuppens P (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 901–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben M, & Kuppens P (2020). Emotion dynamics and the association with depressive features and borderline personality disorder traits: Unique, specific, and prospective relationships. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(2), 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Huprich SK, Paggeot AV, & Samuel DB (2015). Comparing the Personality Disorder Interview for DSM–IV (PDI–IV) and SCID–II Borderline Personality Disorder Scales: An Item–Response Theory Analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(1), 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Solhan MB, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, & Trull TJ (2011). Affect and alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment study of outpatients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(3), 572–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Steger MF, & Julian T (2006). Fragile self-esteem and affective instability in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(11), 1609–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler DJ (1996). Contemporary interpersonal theory and research: Personality, psychopathology, and psychotherapy. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kockler TD, Tschacher W, Santangelo PS, Limberger MF, & Ebner-Priemer UW (2017). Specificity of emotion sequences in borderline personality disorder compared to posttraumatic stress disorder, bulimia nervosa, and healthy controls: An e-diary study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 4(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, . . . Zimmerman M. (2017). The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. doi: 10.1037/abn0000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Derringer J, Markon KE, Watson D, & Skodol AE (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, & Markon KE (2014). The role of the DSM-5 personality trait model in moving toward a quantitative and empirically based approach to classifying personality and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 477–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers F, Swendsen J, Cui L, Husky M, Johns J, Zipunnikov V, & Merikangas KR (2018). Mood reactivity and affective dynamics in mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, & Jang KL (2000). Toward an empirically based classification of personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 14(2), 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, & Jacobsberg LB (1994). The international personality disorder examination: The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(3), 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke O, Marsh HW, Robitzsch A, Trautwein U, Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2008). The multilevel latent covariate model: a new, more reliable approach to group-level effects in contextual studies. Psychological Methods, 13(3), 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MetricWire Inc. (2019). MetricWire (Version 4.2.8). [Mobile application software].

- Mneimne M, Fleeson W, Arnold EM, & Furr RM (2018). Differentiating the everyday emotion dynamics of borderline personality disorder from major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Personality Disorders, 9(2), 192–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Leese M, Lee T, Walters P, Thornicroft G, & Mann A (2003). Standardised assessment of personality - abbreviated scale (SAPAS): Preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(3), 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC (1991). Personality assessment inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide (Version 8). Los Angeles, CA: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BP (2005). A search for consensus on the dimensional structure of personality disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(3), 323–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Both L, Kumar S, Wilhelm K, & Olley A (2004). Measuring disordered personality functioning: To love and to work reprised. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110 (3), 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL (2005). A contemporary integrative interpersonal theory of personality disorders. In Clarkin J, & Lenzenweger M (Eds.), Major theories of personality disorder (2nd ed., pp. 282–331). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, & Ansell EB (2003). Interpersonal theory of personality. In Millon T & Lerner M (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychology Vol. 5: Personality and social psychology (pp. 209–229). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Reich J (2003). The effect of axis II disorders on the outcome of treatment of anxiety and unipolar depressive disorders: A review. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(5), 387–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald WR, Beeney JE, Pilkonis PA, Wright AGC (2019). Comparing hierarchical models of personality pathology. Journal of Personality Research, 81, 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald WR, Hopwood CJ, Pilkonis PA, & Wright AGC (2020). Dynamic features of interpersonal behavior and affect in relation to general and specific personality pathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche MJ, Jacobson NC, & Pincus AL (2016). Using repeated daily assessments to uncover oscillating patterns and temporally-dynamic triggers in structures of psychopathology: Applications to the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(8), 1090–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC, Sookman D, & Paris J (2007). Stability and variability of affective experience and interpersonal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(3), 578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo PS, Reinhard I, Koudela-Hamila S, Bohus M, Holtmann J, Eid M, & Ebner-Priemer UW (2017). The temporal interplay of self-esteem instability and affective instability in borderline personality disorder patients’ everyday lives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(8), 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo P, Reinhard I, Mussgay L, Steil R, Sawitzki G, Klein C, . . . Ebner-Priemer UW. (2014). Specificity of affective instability in patients with borderline personality disorder compared to posttraumatic stress disorder, bulimia nervosa, and healthy controls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 258–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo PS, Limberger MF, Stiglmayr C, Houben M, Coosemans J, Verleysen G, . . . Ebner-Priemer UW. (2016). Analyzing subcomponents of affective dysregulation in borderline personality disorder in comparison to other clinical groups using multiple e-diary datasets. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 3(1), 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Wright AGC, Fowler JC, Frueh BC, Allen JG, Oldham J, & Clark LA (2015). The structure of personality pathology: Both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(2), 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiderer EM, Wang T, Tomko RL, Wood PK, & Trull TJ (2016). Negative affect instability among individuals with comorbid borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(1), 67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmideberg M (1959). The borderline patient. In Arieti S (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (Vol. 1, pp. 398–416). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, & Chiappetta L (2017). Suicidal behavior and psychosocial outcome in borderline personality disorder at 8-year follow-up. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(6), 774–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Fabio A, Kelly TM, Malone KM, & Mann JJ (2005). High-lethality status in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(4), 386–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry SH, & Kwapil TR (2019). Affective dynamics in bipolar spectrum psychopathology: Modeling inertia, reactivity, variability, and instability in daily life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 251, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton K, McDonnell CG, Hayden EP, & Watson D (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to psychopathology measurement: Recommendations for measure selection, data analysis, and participant recruitment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(1), 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern A (1938). Borderline group of neuroses. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 7, 467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Smith SM, . . . Grant BF. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: Results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(7), 1033–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, Jahng S, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, & Watson D (2008). Affective instability: Measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 647–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P, Reed GM, & Crawford MJ (2015). Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385, 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, & Simonsen E (2005). Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: Finding a common ground. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(2), 110–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TF, Scalco MD, & Simms LJ (2018). The construct validity of general and specific dimensions of personality pathology. Psychological Medicine, 48(5), 834–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TF, & Simms LJ (2016). Personality disorder models and their coverage of interpersonal problems. Personality Disorders: Theory Research and Treatment, 7(1), 15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Stroud CB, & Durbin CE (2017). Interpersonal dysfunction in personality disorders: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(7), 677–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC (2017). The current state and future of factor analysis in personality disorder research. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(1), 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, & Simms LJ (2016). Stability and fluctuation of personality disorder features in daily life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 641–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Hopwood CJ, Skodol AE, & Morey LC (2016). Longitudinal validation of general and specific structural features of personality pathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(8), 1120–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Hallquist MN, Morse JQ, Scott LN, Stepp SD, Nolf KA, & Pilkonis PA (2013). Clarifying Interpersonal Heterogeneity in Borderline Personality Disorder Using Latent Mixture Modeling. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(2), 125–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler–Hill V, & Abraham J (2006). Borderline personality features: Instability of self–esteem and affect. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(6), 668–687. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler-Hill V, Holden CJ, Enjaian B, Southard AC, Besser A, Li H, & Zhang Q (2015). Self-esteem instability and personality: The connections between feelings of self-worth and the big five dimensions of personality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(2), 183–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.