Abstract

Background

There are little data on diverticular disease and cancer development other than colorectal cancer.

Methods

We conducted a population-based, matched cohort study with linkage of nationwide registers to the Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden histopathology cohort. We included 75 704 patients with a diagnosis of diverticular disease and colorectal histopathology and 313 480 reference individuals from the general population matched on age, sex, calendar year, and county. Cox proportional hazards models estimated multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for associations between diverticular disease and overall cancer and specific cancers.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 6 years, we documented 12 846 incident cancers among patients with diverticular disease and 43 354 incident cancers among reference individuals from the general population. Compared with reference individuals, patients with diverticular disease had statistically significantly increased overall cancer incidence (24.5 vs 18.1 per 1000 person-years), equivalent to 1 extra cancer case in 16 individuals with diverticular disease followed-up for 10 years. After adjusting for covariates, having a diagnosis of diverticular disease was associated with a 33% increased risk of overall cancer (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.31 to 1.36). The risk increases also persisted compared with siblings as secondary comparators (HR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.21 to 1.32). Patients with diverticular disease also had an increased risk of specific cancers, including colon cancer (HR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.60 to 1.82), liver cancer (HR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.41 to 2.10), pancreatic cancer (HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.42 to 1.84), and lung cancer (HR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.39 to 1.61). The increase in colorectal cancer risk was primarily restricted to the first year of follow-up, and especially early cancer stages.

Conclusions

Patients with diverticular disease who have colorectal histopathology have an increased risk of overall incident cancer.

Diverticular disease is among the most common gastrointestinal disorders in Western countries. In the United States, more than 60% of the population aged 70 years and older are affected by diverticulosis (1), which is asymptomatic in most circumstances; however, many develop complications, including diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding (2), which lead to substantial morbidity and health-care costs. In 2014, diverticular disease accounted for 1.9 million clinic visits and 208 000 hospital admissions in the United States, with an aggregate cost of 2 billion dollars (3).

Diverticular disease and cancer are generally thought to reflect different disease processes. However, several lines of evidence indicate that they may be associated. Diverticular disease and cancer share major risk factors, including older age, obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, and a Western dietary pattern low in fiber and high in red and processed meat (4,5), and these common risk factors alone could contribute to an association. Modern theories suggest that chronic inflammation may play a role in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease (6). Diverticular disease has been associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as cardiovascular disease (7,8). In a recent prospective nested case-control study, prediagnostic circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 were associated with increased risk of diverticulitis (9). Because chronic inflammation predisposes to the development of cancer and promotes all stages of tumorigenesis (10), a causal link of diverticular disease with cancer is possible.

Previous studies have documented an association between diverticular disease and an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), particularly within the first year after the diagnosis of diverticular disease (11-15). This has been attributed to screening effects or misclassification (12). There have also been limited data suggesting an association between diverticular disease and cancers other than CRC (16,17). However, whether diverticular disease increases risk of overall cancer and specific cancers in the long-term remains inconclusive.

We hypothesized that diverticular disease was associated with an increase in the subsequent risk of overall cancer and specific cancers such as CRC. Thus, we conducted a nationwide study of all adults in Sweden with a diagnosis of diverticular disease and colorectal histopathology to examine the long-term risk of incident cancer and specific cancers using the Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden (ESPRESSO) cohort. We also examined whether the association differed according to the histological features of diverticular disease.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a population-based, matched cohort study using the ESPRESSO cohort (18). ESPRESSO includes a total of 6.1 million histopathology records between 1965 and 2017 from all pathology departments (n = 28) in Sweden. Each report consists of a unique personal identification number and histopathology date and describes topography and morphology using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) system. We linked ESPRESSO to validated, nationwide registers with data regarding demographics, comorbidities, prescribed medications, incident cancers, and death. ESPRESSO was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board. Informed consent was waived because of the register-based nature of the ESPRESSO database.

For this study, as the source population for patients with diverticular disease, we first identified all individuals aged 18 years and older with a recorded topographical T67-T68 (colorectal) histopathology specimen since 1987 (the start of complete national coverage of the Swedish National Patient Register). We excluded individuals with a previous record of colectomy, those who had emigrated before the study entry despite having a histopathology in Sweden, or those with a diagnosis of cancer at baseline. We also excluded those with SNOMED codes for earlier surgery (4650, 4651, 4652, 4653, 4654, JFH00, JFH01, JFH11, JFH20, JFH30, JFH33, JFH40, or JFH96).

Ascertainment of diverticular disease and reference individuals

Diverticular disease was defined as anyone with a hospital record (inpatient or outpatient) listed under the following International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes—ICD-8 (562.10; 562.11; 562.18; 562.19), ICD-9 (562B), ICD-10 (K57.2, K57.3, K57.4, K57.5, K57.8, K57.9)—since 1987 in the National Patient Register as well as a SNOMED code relating to T67-T68 (colorectal). In a previous validation study of 112 men with diverticular disease defined as discharge or death with a primary or secondary diagnosis (ICD codes) identified in the Swedish Inpatient Register, the diagnosis was verified in all (107 of 107) cases for whom medical records could be retrieved (19). ICD codes for diverticular disease also yielded a positive predictive value of 91%-98% in similar National Register of Patients from Denmark that included both inpatient and outpatient diagnoses (20). In our study, date of diagnosis was the second of either the first ICD code for diverticular disease or colorectal histopathology (whichever occurred later).

Patients meeting our criteria for diverticular disease were subsequently categorized into those with diverticula form (M327, M32700, M32710, M46400, M4642), inflammation (M40-44, M4000, M4100, M4211, M4300, M4502, M4500), or normal histology (M00100, M00110).

Each patient with diverticular disease was matched to up to 5 reference individuals from the general population without recorded diverticular disease from the Total Population Register (21) according to age, sex, calendar year, and county of residence. To reduce the influence of shared early environmental and genetic risk factors, we also included siblings as a secondary comparator group for those who had siblings. Identical exclusion criteria were applied for patients with diverticular disease and reference individuals (Supplementary Figure 1, available online).

Ascertainment of incident cancer and covariates

Incident overall cancer was ascertained from the Swedish Cancer Register, which is complete for more than 96% of all cancers (22) and in which all cases are confirmed and classified by specialists using established histopathological or radiographical criteria. We additionally examined specific cancer types, including hematologic cancer and cancers of solid organ (colon, rectum, pancreas, stomach, liver, gallbladder, lung, prostate, and breast) (Supplementary Table 1, available online). We also collected detailed information regarding demographics and comorbidities (Supplementary Methods, available online) (21,23–25).

Statistical analysis

The baseline for patients with diverticular disease was defined as the second of either the first ICD code for diverticular disease or colorectal histopathology (whichever occurred later) and the baseline for reference individuals as set as the corresponding baseline of the matched patient with diverticular disease. Person-time was calculated from baseline to incident cancer, death, emigration, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2017), whichever occurred earlier.

We plotted unadjusted cumulative incidence of overall cancer and cancer subtypes comparing patients with diverticular disease with matched reference individuals from the general population using Kaplan-Meier curves over 15 years. We also used stratified Cox proportional hazard models accounting for matching factors (age at baseline, sex, calendar year, and county) to estimate multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for education level and comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and alcohol-related diseases. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by testing the statistical significance of the association between Schoenfeld residuals and time, and no violation was observed. We calculated cancer-specific hazards for specific cancer outcomes.

For a subset of patients who had siblings, we included their full siblings as secondary comparator group. We also separately examined diverticular disease and cancer risk according to diverticula or inflammation and normal histology.

We conducted stratified analysis and evaluated the associations between diverticular disease and the development of cancer in subgroups. We also conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. Details are described in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

We included 75 704 patients with both colorectal histopathology and a diagnosis of diverticular disease and 313 480 reference individuals from the general population and 60 956 siblings as a secondary comparator. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. The mean age was 62 years for patients with diverticular disease and reference individuals from the general population, and the siblings were slightly younger, with a mean age of 55 years. The level of education was similar between patients with diverticular disease and reference individuals. The median time between histopathology and diagnosis of diverticular disease was 6 months. Patients with diverticular disease had a higher number of clinic visits and comorbidities, such as obesity or dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohorta

| Characteristics | Patients with diverticular disease | Reference individuals from general population | Sibling comparators |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 75 704) | (n = 313 480) | (n = 60 956) | |

| Sex | |||

| Men, No. (%) | 31 841 (42) | 136 451 (44) | 31 664 (52) |

| Women, No. (%) | 43 863 (58) | 177 029 (56) | 29 292 (48) |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.6 (13.6) | 61.6 (13.6) | 54.6 (11.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 64 (54-73) | 62 (53-72) | 56 (47-63) |

| Range, min-max | 18-99 | 18-100 | 18-84 |

| Categories, No. (%) | |||

| <30 | 1031 (1) | 4793 (2) | 1652 (3) |

| 30-39 | 3380 (4) | 15 700 (5) | 5150 (8) |

| 40-49 | 8679 (11) | 39 512 (13) | 12 583 (21) |

| 50-59 | 15 850 (21) | 69 264 (22) | 18 984 (31) |

| 60-69 | 21 628 (29) | 89 385 (29) | 16 782 (28) |

| 70-79 | 17 479 (23) | 67 336 (21) | 5621 (9) |

| 80+ | 7657 (10) | 27 490 (9) | 184 (0) |

| Country of birth, No. (%) | |||

| Nordic | 71 432 (94) | 286 445 (91) | 60 444 (99) |

| Other | 4270 (6) | 27 026 (9) | 512 (1) |

| Missing | 2 (0) | 9 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Level of education, No. (%) | |||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 y | 25 180 (33) | 103 547 (33) | 17 587 (29) |

| Upper secondary school (10-12 y) | 29 030 (38) | 115 616 (37) | 27 218 (45) |

| College or university (≥13 y) | 14 852 (20) | 69 664 (22) | 13 635 (22) |

| Missing | 6642 (9) | 24 653 (8) | 2516 (4) |

| Start year of follow-up | |||

| 1987-1999 | 13 196 (17) | 58 554 (19) | 6490 (11) |

| 2000-2009 | 30 354 (40) | 126 582 (40) | 23 731 (39) |

| 2010-2016 | 32 154 (42) | 128 344 (41) | 30 735 (50) |

| Time between first diagnosis and biopsy, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (6.0) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.0-5.8) | ||

| In/out visits/admissions for 365 d before, No. (%) | |||

| 0 | 28 455 (38) | 212 372 (68) | 38 691 (63) |

| 1 | 16 322 (22) | 42 816 (14) | 8949 (15) |

| 2 | 9566 (13) | 20 691 (7) | 4614 (8) |

| 3+ | 21 361 (28) | 37 601 (12) | 8702 (14) |

| Prior inflammatory bowel disease, No. (%) | 1752 (2.3) | 264 (0.1) | 219 (0.4) |

| Prior cardiovascular disease, No. (%) | 5949 (7.9) | 14547 (4.6) | 2032 (3.3) |

| Prior ischemic heart disease, No. (%) | 2551 (3.4) | 6478 (2.1) | 1063 (1.7) |

| Prior thromboembolic disease, No. (%) | 1117 (1.5) | 1943 (0.6) | 275 (0.5) |

| Prior deep venous thrombosis, No. (%) | 507 (0.7) | 887 (0.3) | 119 (0.2) |

| Prior cerebrovascular disease, No. (%) | 1660 (2.2) | 5114 (1.6) | 610 (1.0) |

| Prior congestive heart failure, No. (%) | 1426 (1.9) | 2889 (0.9) | 271 (0.4) |

| Prior respiratory disease, No. (%) | 7184 (9.5) | 15 130 (4.8) | 3352 (5.5) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 1364 (1.8) | 3438 (1.1) | 618 (1.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, No. (%) | 843 (1.1) | 1304 (0.4) | 233 (0.4) |

| Obesity/dyslipidemia, No. (%) | 2483 (3.3) | 5243 (1.7) | 1185 (1.9) |

| Alcohol-related disease, No. (%) | 569 (0.8) | 1425 (0.5) | 363 (0.6) |

Baseline comorbidities are defined as any hospital contact within 5 years before index. IQR = interquartile range.

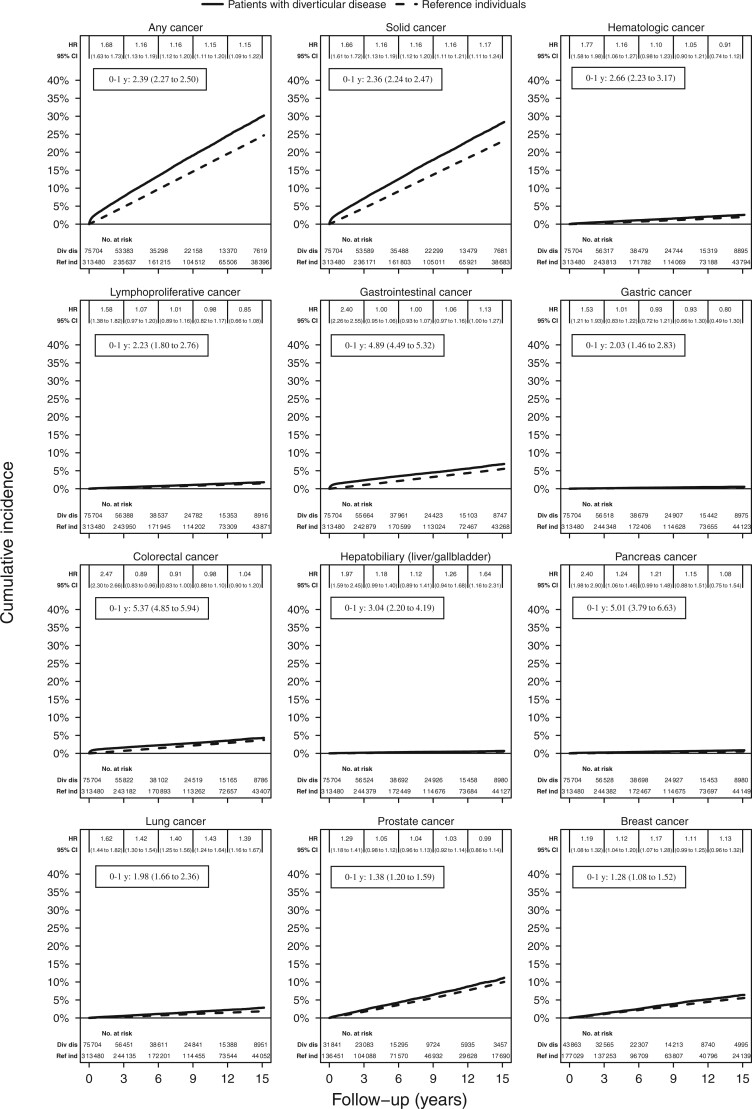

Overall cancer incidence

Over a median follow-up of 6 years, we documented 12 846 incident cancers among patients with diverticular disease (24.5/1000 person-years [PY]) and 43 354 incident cancers among reference individuals from the general population (18.1/1000 PY), yielding an absolute rate difference of 6.4/1000 PY (Table 2). This is equal to 1 extra cancer in 16 patients with diverticular disease followed-up for 10 years. A Kaplan-Meier curve showed an increased risk of overall cancer in 15 years, in particular during the first year of follow-up (Figure 1). After multivariable adjustment, the risk for incident overall cancer was 33% higher among patients with diverticular disease compared with reference individuals (95% CI = 1.31 to 1.36).

Table 2.

Risk of any cancer and specific cancer in patients with diverticular disease (N = 75 704) and matched reference individuals from the general population (N = 313 480)

| Cancers | Events, No. (%) | Median follow-up years (IQR) | Incidence rate/1000 PY (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Stratifieda | Adjusted Ib | Adjusted IIc | Adjusted IIId | ||||

| Any cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 12 846 (17.0) | 5.5 (2.5-10.0) | 24.5 (24.1 to 24.9) | 1.36 (1.33 to 1.38) | 1.34 (1.31 to 1.36) | 1.34 (1.31 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.36) |

| Reference individuals | 43 354 (13.8) | 6.2 (3.0-10.9) | 18.1 (18.0 to 18.3) | |||||

| Solid cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 11 999 (15.8) | 5.6 (2.5-10.0) | 22.8 (22.4 to 23.2) | 1.35 (1.32 to 1.38) | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) |

| Reference individuals | 40 668 (13.0) | 6.2 (3.1-10.9) | 17.0 (16.8 to 17.1) | |||||

| Hematologic cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1002 (1.3) | 6.1 (2.9-10.7) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | 1.38 (1.29 to 1.49) | 1.34 (1.24 to 1.44) | 1.34 (1.24 to 1.44) | 1.34 (1.24 to 1.44) | 1.34 (1.24 to 1.44) |

| Reference individuals | 3248 (1.0) | 6.7 (3.3-11.6) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) | |||||

| Lymphoproliferative cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 689 (0.9) | 6.1 (2.9-10.7) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 1.26 (1.16 to 1.38) | 1.23 (1.12 to 1.34) | 1.23 (1.12 to 1.34) | 1.24 (1.13 to 1.35) | 1.24 (1.13 to 1.35) |

| Reference individuals | 2445 (0.8) | 6.7 (3.3-11.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 3103 (4.1) | 6.0 (2.8-10.7) | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.7) | 1.48 (1.42 to 1.54) | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.54 | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.53) | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.53) | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.53) |

| Reference individuals | 9424 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.3-11.5) | 3.7 (3.7 to 3.8) | |||||

| Gastric cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 223 (0.3) | 6.2 (2.9-10.8) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.4) | 1.20 (1.04 to 1.40) | 1.17 (1.00 to 1.37) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.36) | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.38) | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.38) |

| Reference individuals | 826 (0.3) | 6.7 (3.4-11.6) | 0.3 (0.3 to 0.3) | |||||

| Colorectal cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1992 (2.6) | 6.1 (2.9-10.7) | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 1.43 (1.36 to 1.51) | 1.41 (1.34 to 1.49) | 1.41 (1.33 to 1.48) | 1.42 (1.34 to 1.50) | 1.42 (1.34 to 1.49) |

| Reference individuals | 6241 (2.0) | 6.7 (3.3-11.5) | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.5) | |||||

| Colon cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1564 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.9-10.7) | 2.8 (2.6 to 2.9) | 1.71 (1.61 to 1.81) | 1.70 (1.60 to 1.81) | 1.70 (1.59 to 1.80) | 1.71 (1.60 to 1.82) | 1.71 (1.60 to 1.82) |

| Reference individuals | 4103 (1.3) | 6.7 (3.3-11.6) | 1.6 (1.6 to 1.7) | |||||

| Rectal cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 433 (0.6) | 6.1 (2.9-10.8) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.8) | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.97) | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.96) | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98) | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.97) |

| Reference individuals | 2205 (0.7) | 6.7 (3.3-11.6) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | |||||

| Hepatobiliary (liver/gallbladder) cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 277 (0.4) | 6.2 (3.0-10.8) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.5) | 1.46 (1.27 to 1.67) | 1.43 (1.24 to 1.65) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 1.38 (1.19 to 1.59) | 1.37 (1.19 to 1.58) |

| Reference individuals | 849 (0.3) | 6.8 (3.4-11.6) | 0.3 (0.3 to 0.4) | |||||

| Liver cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 161 (0.2) | 6.2 (3.0-10.8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 1.93 (1.61 to 2.32) | 1.81 (1.49 to 2.20) | 1.78 (1.46 to 2.17) | 1.72 (1.41 to 2.10) | 1.72 (1.41 to 2.10) |

| Reference individuals | 373 (0.1) | 6.8 (3.4-11.6) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | |||||

| Gallbladder cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 93 (0.1) | 6.2 (3.0-10.8) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.25) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.28) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.28) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.27) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) |

| Reference individuals | 416 (0.1) | 6.8 (3.4-11.6) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | |||||

| Pancreas cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 356 (0.5) | 6.2 (3.0-10.8) | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | 1.64 (1.45 to 1.85) | 1.65 (1.45 to 1.87) | 1.64 (1.44 to 1.86) | 1.62 (1.42 to 1.84) | 1.62 (1.42 to 1.84) |

| Reference individuals | 973 (0.3) | 6.8 (3.4-11.6) | 0.4 (0.4 to 0.4) | |||||

| Lung cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1077 (1.4) | 6.1 (2.9-10.8) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 1.52 (1.42 to 1.63) | 1.51 (1.40 to 1.62) | 1.51 (1.40 to 1.62) | 1.51 (1.40 to 1.62) | 1.50 (1.39 to 1.61) |

| Reference individuals | 3182 (1.0) | 6.7 (3.3-11.6) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) | |||||

| Prostate cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1737 (5.5) | 5.8 (2.7-10.2) | 7.6 (7.3 to 8.0) | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.22) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.19) |

| Reference individuals | 7061 (5.2) | 6.3 (3.2-11.1) | 6.6 (6.5 to 6.8) | |||||

| Breast cancer | ||||||||

| Diverticular disease | 1432 (3.3) | 6.1 (2.9-10.7) | 4.4 (4.2 to 4.6) | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) |

| Reference individuals | 5349 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.3-11.5) | 3.8 (3.7 to 3.9) | |||||

Stratified = stratified analysis on matched pair. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IQR = interquartile range; PY = person years.

Adjusted I = stratified + adjustment for education level.

Adjusted II = adjusted I + adjustment for comorbidities: cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Adjusted III = adjusted II + adjustment for comorbidities: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and alcohol-related disease.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves (up to 15 years). Curves and hazard ratios (HRs) are unadjusted. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) during the first year of follow-up are shown in the black boxes.

This association was similar among women (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.27 to 1.34) and men (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.33 to 1.41; Table 3). The association appeared to be stronger during the first year of follow-up (HR = 2.27, 95% CI = 2.15 to 2.38) but remained statistically significant after 5 years (HR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.14 to 1.22). Among patients with cardiovascular disease, having a diagnosis of diverticular disease was still associated with a 47% increased risk of overall cancer (95% CI = 1.35 to 1.60). The statistically significant, positive association between diverticular disease and incidence of overall cancer was similar across strata defined by other factors. Individuals with an ICD code before the SNOMED code had a slightly lower hazard ratio (1.28, 95% CI = 1.25 to 1.31) than those with a SNOMED code before the ICD code (HR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.42 to 1.52).

Table 3.

Risk of any cancer in patients with diverticular disease and matched reference individuals from the general population

| Subgroups | No. (%) in diverticular disease | No. (%) in reference individuals | PY in diverticular disease | PY in reference individuals | Events in diverticular disease (%) | Events in reference individuals (%) | Incidence rate/1000 PY in diverticular disease (95% CI) | Incidence rate/1000 PY in reference individuals (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | HR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 75 704 (100) | 313 480 (100) | 524 187 | 2 389 417 | 12 846 (17.0) | 43 354 (13.8) | 24.5 (24.1 to 24.9) | 18.1 (18.0 to 18.3) | 1.34 (1.31 to 1.36) | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.36) |

| Follow-up | ||||||||||

| <1 y | 75 704 (100) | 313 480 (100) | 70 678 | 302 553 | 2662 (3.5) | 4766 (1.5) | 37.7 (36.2 to 39.1) | 15.8 (15.3 to 16.2) | 2.28 (2.17 to 2.39) | 2.27 (2.15 to 2.38) |

| 1-5 y | 67 256 (88.8) | 290 776 (92.8) | 214 799 | 946 978 | 4597 (6.8) | 16 105 (5.5) | 21.4 (20.8 to 22.0) | 17.0 (16.7 to 17.3) | 1.21 (1.17 to 1.25) | 1.21 (1.17 to 1.25) |

| >5 y | 40 906 (54.0) | 184 538 (58.9) | 238 710 | 1 139 886 | 5587 (13.7) | 22 483 (12.2) | 23.4 (22.8 to 24.0) | 19.7 (19.5 to 20.0) | 1.18 (1.15 to 1.22) | 1.18 (1.14 to 1.22) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Women | 43 863 (57.9) | 177 029 (56.5) | 307 892 | 1 362 262 | 6977 (15.9) | 23 335 (13.2) | 22.7 (22.1 to 23.2) | 17.1 (16.9 to 17.4) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.35) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.34) |

| Men | 31 841 (42.1) | 136 451 (43.5) | 216 295 | 1 027 155 | 5869 (18.4) | 20 019 (14.7) | 27.1 (26.4 to 27.8) | 19.5 (19.2 to 19.8) | 1.37 (1.33 to 1.42) | 1.37 (1.33 to 1.41) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18-29 y | 1031 (1.4) | 4793 (1.5) | 7766 | 37 299 | 42 (4.1) | 109 (2.3) | 5.4 (3.9 to 7.3) | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.5) | 1.71 (1.19 to 2.46) | 1.71 (1.17 to 2.50) |

| 30 y-39y | 3380 (4.5) | 15 700 (5.0) | 28 430 | 136 010 | 188 (5.6) | 629 (4.0) | 6.6 (5.7 to 7.6) | 4.6 (4.3 to 5.0) | 1.43 (1.21 to 1.69) | 1.45 (1.22 to 1.72) |

| 40 y-49y | 8679 (11.5) | 39 512 (12.6) | 75 860 | 359 148 | 851 (9.8) | 3018 (7.6) | 11.2 (10.5 to 12.0) | 8.4 (8.1 to 8.7) | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.42) | 1.30 (1.20 to 1.41) |

| 50 y-59y | 15 850 (20.9) | 69 264 (22.1) | 128 767 | 597 841 | 2463 (15.5) | 8877 (12.8) | 19.1 (18.4 to 19.9) | 14.8 (14.5 to 15.2) | 1.28 (1.22 to 1.34) | 1.27 (1.21 to 1.33) |

| 60 y-69y | 21 628 (28.6) | 89 385 (28.5) | 149 106 | 674 133 | 4291 (19.8) | 14 807 (16.6) | 28.8 (27.9 to 29.7) | 22.0 (21.6 to 22.3) | 1.33 (1.28 to 1.38) | 1.32 (1.28 to 1.37) |

| 70 y-79y | 17 479 (23.1) | 67 336 (21.5) | 102 802 | 455 107 | 3756 (21.5) | 12 371 (18.4) | 36.5 (35.4 to 37.7) | 27.2 (26.7 to 27.7) | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.42) | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.42) |

| 80+ | 7657 (10.1) | 27 490 (8.8) | 31 457 | 129 879 | 1255 (16.4) | 3543 (12.9) | 39.9 (37.7 to 42.2) | 27.3 (26.4 to 28.2) | 1.48 (1.37 to 1.59) | 1.47 (1.37 to 1.59) |

| Year | ||||||||||

| 1987-1999 | 13 196 (17.4) | 58 554 (18.7) | 165 439 | 812 579 | 3396 (25.7) | 13 853 (23.7) | 20.5 (19.8 to 21.2) | 17.0 (16.8 to 17.3) | 1.23 (1.18 to 1.28) | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.27) |

| 2000-2009 | 30 354 (40.1) | 126 582 (40.4) | 254 642 | 1 140 636 | 6400 (21.1) | 21 396 (16.9) | 25.1 (24.5 to 25.8) | 18.8 (18.5 to 19.0) | 1.33 (1.29 to 1.36) | 1.32 (1.29 to 1.36) |

| 2010-2016 | 32 154 (42.5) | 128 344 (40.9) | 104 107 | 436 201 | 3050 (9.5) | 8105 (6.3) | 29.3 (28.3 to 30.4) | 18.6 (18.2 to 19.0) | 1.53 (1.47 to 1.60) | 1.54 (1.48 to 1.61) |

| Country of birth | ||||||||||

| Nordic | 71 432 (94.4) | 286 445 (91.4) | 496 951 | 2 203 820 | 12 327 (17.3) | 40 947 (14.3) | 24.8 (24.4 to 25.2) | 18.6 (18.4 to 18.8) | 1.32 (1.30 to 1.35) | 1.32 (1.29 to 1.35) |

| Other | 4270 (5.6) | 27 026 (8.6) | 27 214 | 185 561 | 519 (12.2) | 2407 (8.9) | 19.1 (17.5 to 20.8) | 13.0 (12.5 to 13.5) | 1.29 (1.03 to 1.63) | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.56) |

| Level of education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 y | 25 180 (33.3) | 103 547 (33.0) | 180 116 | 808 963 | 4834 (19.2) | 16 727 (16.2) | 26.8 (26.1 to 27.6) | 20.7 (20.4 to 21.0) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.35) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.35) |

| Upper secondary school, 10-12 y | 29 030 (38.3) | 115 616 (36.9) | 199 986 | 849 633 | 4526 (15.6) | 14 542 (12.6) | 22.6 (22.0 to 23.3) | 17.1 (16.8 to 17.4) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.36) | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.36) |

| College or university, ≥13 y | 14 852 (19.6) | 69 664 (22.2) | 96 919 | 499 181 | 2224 (15.0) | 7970 (11.4) | 22.9 (22.0 to 23.9) | 16.0 (15.6 to 16.3) | 1.37 (1.30 to 1.43) | 1.36 (1.30 to 1.42) |

| Missing | 6642 (8.8) | 24 653 (7.9) | 47 166 | 231 640 | 1262 (19.0) | 4115 (16.7) | 26.8 (25.3 to 28.3) | 17.8 (17.2 to 18.3) | 1.52 (1.42 to 1.62) | 1.50 (1.41 to 1.60) |

| Diverticular disease | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis before biopsy | 49 839 (65.8) | 214 246 (68.3) | 370 058 | 172 898 | 8539 (17.1) | 30 942 (14.4) | 23.1 (22.6 to 23.6) | 17.9 (17.7 to 18.1) | 1.28 (1.25 to 1.31) | 1.28 (1.25 to 1.31) |

| Biopsy before diagnosis | 25 150 (33.2) | 95 833 (30.6) | 149 155 | 639 332 | 4199 (16.7) | 12 029 (12.6) | 28.2 (27.3 to 29.0) | 18.8 (18.5 to 19.2) | 1.48 (1.43 to 1.53) | 1.47 (1.42 to 1.52) |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 5949 (7.9) | 14 547 (4.6) | 24 748 | 68 154 | 844 (14.2) | 1617 (11.1) | 34.1 (31.8 to 36.5) | 23.7 (22.6 to 24.9) | 1.47 (1.36 to 1.60) | 1.47 (1.35 to 1.60) |

| Respiratory disease | 7184 (9.5) | 15 130 (4.8) | 31 136 | 72 063 | 919 (12.8) | 1466 (9.7) | 29.5 (27.6 to 31.5) | 20.3 (19.3 to 21.4) | 1.47 (1.35 to 1.60) | 1.48 (1.36 to 1.61) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1752 (2.3) | 264 (0.1) | 9840 | 1333 | 196 (11.2) | 32 (12.1) | 19.9 (17.2 to 22.9) | 24.0 (16.4 to 33.9) | 0.81 (0.56 to 1.18) | 0.82 (0.56 to 1.20) |

| Hepatitis C | 62 (0.1) | 143 (0.0) | 272 | 729 | 4 (6.5) | 3 (2.1) | 14.7 (4.0 to 37.7) | 4.1 (0.8 to 12.0) | 5.11 (0.99 to 26.27) | 7.41 (1.13 to 48.34) |

Stratified Cox. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PY = person-years.

Stratified Cox + adjustment for education level and comorbidities: cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and alcohol-related disease.

We also compared patients with diverticular disease with their siblings as a secondary comparator in a subset who had siblings (Supplementary Table 3, available online). We documented 4305 incident cancers among patients with diverticular disease (19.2/1000 PY) and 6544 incident cancers among their sibling comparators (14.4/1000 PY), yielding an absolute rate difference of 4.8/1000 PY. The multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio showed a 26% increased risk of overall cancer among patients with diverticular disease compared with their siblings (95% CI = 1.21 to 1.32).

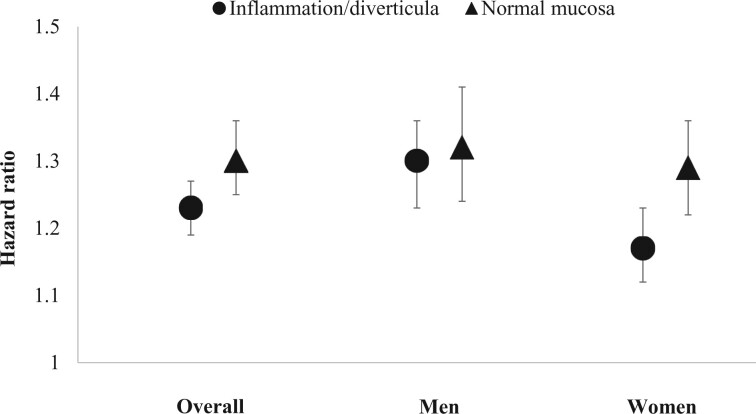

The rates of incident overall cancer slightly differed according to the histological features of diverticular disease (Figure 2). Compared with the matched general population, the absolute rate differences and corresponding hazard ratios were 3.8/1000 PY (HR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.19 to 1.27) for diverticular disease with diverticula or inflammation and 5.9/1000 PY (HR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.25 to 1.36) for diverticular disease with normal histology (Pinteraction = .02).

Figure 2.

Risk of any cancer in patients with diverticular disease with inflammation or diverticula or normal histology and matched reference individuals from the general population. Models were stratified by matching pair and adjusted for education level and comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and alcohol-related disease. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Incidence of cancer types

Compared with reference individuals from the general population, patients with diverticular disease had higher rates of developing CRC and gastrointestinal cancer, in particular during the first year of follow-up (Figure 1). The rates of CRC were 3.5/1000 PY in patients with diverticular disease and 2.5/1000 PY in reference individuals, yielding a multivariable hazard ratio of 1.42 (95% CI = 1.34 to 1.49; Table 2). This excess risk corresponded to 1 extra CRC case in 1000 patients with diverticular disease followed-up for 1 year. A greater percentage of early T-stage CRC was found in patients with diverticular disease compared with reference individuals (Supplementary Table 4, available online). We also analyzed colon and rectal cancer separately and found that patients with diverticular disease had an increased risk of colon cancer (HR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.60 to 1.82) but a decreased risk of rectal cancer (HR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.79 to 0.97) compared with reference individuals.

Diverticular disease was also associated with increased risk of other gastrointestinal cancers, including gastric cancer (HR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.38) and liver cancer (HR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.41 to 2.10). The rates for gastrointestinal cancer were 5.5/1000 PY in patients with diverticular disease and 3.7/1000 PY in reference individuals, with an overall risk of 47% higher (95% CI = 1.41 to 1.53) in patients with diverticular disease.

Patients with diverticular disease also had statistically significantly higher rates of developing nongastrointestinal cancers, including pancreatic cancer (HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.42 to 1.84), lung cancer (HR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.39 to 1.61), prostate cancer (HR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.07 to 1.19), breast cancer (HR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.24), solid cancer (HR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.30 to 1.36), hematologic cancer (HR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.24 to 1.44), and lymphoproliferative cancer (HR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.13 to 1.35). Analyses with siblings as the comparator yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 5, available online).

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings were robust across all sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table 6, available online). The association between diverticular disease and cancer was similar in different calendar periods (1987-1999, 2000-2009, 2010-2016). The association with cancer did not substantially change when restricting to those with diverticular disease diagnosis and colorectal histopathology within a short time interval of less than 1 year (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.27 to 1.34) or less than 30 days (HR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.24 to 1.33). Since 2001, the National Patient Register has covered outpatient doctor visits. In our analysis restricted to individuals with the start of follow-up after 2002, diverticular disease diagnosed in both inpatient (HR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.28 to 1.43) and outpatient (HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.34 to 1.44) was associated with increased risk of overall incident cancer. Our finding also persisted after excluding patients with previous inflammatory bowel disease (HR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.31 to 1.37). Finally, when we restricted to patients with diverticular disease as the primary diagnosis, diverticular disease was still associated with an increased risk of overall cancer (HR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.22 to 1.29).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study using data from established national registers in Sweden, patients with diverticular disease and a colorectal biopsy were shown to have a 33% increased risk of overall incident cancer compared with a general population without diverticular disease. The risk for cancer was greater within the first year after diagnosis of diverticular disease but remained modest in the long term; of note, absolute excess risks were small. Patients with diverticular disease also had an increased risk of specific cancers, including colon cancer, other gastrointestinal cancers such as liver cancer, as well as nongastrointestinal cancers such as lung cancer. Statistically significant excess cancer incidence was apparent in diverticular disease both in patients with a normal colorectal histopathology and in those with inflammation or diverticula or normal histology.

Our study extends our knowledge of diverticular disease and cancer by quantifying the long-term risk of both overall cancer and specific cancers in a nationwide, population-based histopathology cohort. Previous studies have focused mainly on CRC and reported an increased risk among patients with diverticular disease, in particular within the first year after diagnosis (11–13,15). We had similar findings in our study. Our results also revealed a persistent increase in the risk of overall cancer in the long term after diagnosis of diverticular disease, which was primarily driven by liver cancer and lung cancer. Some limited data have suggested a link between diverticular disease and cancers other than CRC (16,17). In a cohort study based on the Danish registers, patients with venous thromboembolism and diverticular disease had a modest increase in the incidence of overall cancer (17). Diverticular disease was also associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer among men with hypertension (16).

The observed association between diverticular disease and cancer could be explained by several reasons. First, patients with undiagnosed cancer might be misclassified as having diverticular disease at initial examination because of overlapping symptoms such as abdominal pain and change in bowel movement, but later a diagnosis of cancer is confirmed. Second, diverticular disease and the presence of diverticulosis are likely to be confirmed on imaging tests (abdominal computed tomography or ultrasound) of routine screening through which cancers are concurrently diagnosed, leading to an increase in cancer incidence, in particular during the first year after the screening (26,27). Third, according to the US and European guidelines for the management of diverticulitis, a follow-up colonoscopy is recommended to be conducted after diagnosis of diverticulitis to rule out a missed malignancy (28), and thus patients with a history of diverticulitis may have more colonoscopies and thus a higher chance of CRC diagnosis, particularly within the first year of diagnosis. Overall, patients with diverticular disease may be under closer medical scrutiny (misclassification, screening effect, and follow-up colonoscopy after diverticulitis) and therefore have a higher chance to be diagnosed with cancer. This is supported by our findings that early-stage CRC was seen more often in diverticular disease than in reference individuals. The reduced risk of rectal cancer in diverticular disease needs to be explored further, which might be due to the fact that rectal cancer is more likely to be detected at initial examination for diverticular disease.

Given that we observed a persistent increase in the risk of overall cancer in the long-term after the diagnosis of diverticular disease, a biological link between diverticular disease and cancer is possible. A growing body of evidence has implicated a role for chronic inflammation and gut dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease that mimics irritable bowel syndrome and even inflammatory bowel disease (29,30). Patients with diverticular disease showed markedly increased macrophage infiltration in both the diverticular region and at distal sites as well as depletion of gut microbiota members with antiinflammatory properties (31). Circulating levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein were associated with incidence and histological damage in diverticulitis (9,32). Besides cancer, patients with diverticular disease were also found to have an increased risk of other chronic inflammatory diseases such as cardiovascular disease (7,8). These lines of evidence collectively provide support for chronic inflammation as a potential mechanism contributing to the link between diverticular disease and cancer.

Intriguingly, we found that the association between diverticular disease and cancer was observed regardless of the histology (inflammation or diverticula vs normal histology) or severity (inpatient vs outpatient). The slightly stronger association between diverticular disease with normal histology and cancer might be due to chance given we included many comparisons. Alternatively, patients with normal histology were less likely to have symptoms, and thus the indications for patients with diverticular disease and normal histology having a colorectal histopathology may be different from those with inflammation.

Our study has several strengths. The population-based cohort with near-complete long-term follow-up for the entire country and prospectively collected data reduced the potential for selection bias and reverse causation. The large sample size permitted detailed subgroup analyses and examination of cancer types. The validity of ICD codes for diverticular disease has been confirmed in a nationwide patient register setting including Sweden (19,20). The colorectal biopsy allowed us to distinguish diverticular disease with inflammation or diverticula vs normal histology. The inclusion of sibling comparators enabled minimizing the influence of shared genetic and early environmental factors. We also calculated absolute risk of overall cancer associated with diverticular disease. Moreover, our results were robust in many sensitivity analyses.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, we restricted our focus to diverticular disease with a colorectal histopathology; thus, our findings may not extend to patients with diverticular disease who do not undergo histopathology. However, any selection bias is likely small because Swedish guidelines have traditionally recommended a follow-up colonoscopy in patients with diverticular disease after the diagnosis (11,33). Second, our reference individuals may have included patients with undiagnosed diverticular disease; however, such misclassification would only have attenuated our association. Third, we could not exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to a lack of lifestyle factors such as smoking, body mass index and diet, or confounding based on having a histopathology. Nevertheless, our results were robust even when we adjusted for respiratory disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as surrogates for smoking as well as other major lifestyle-associated comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and alcohol-related disease). Fourth, we could not distinguish between different categories of diverticular disease (diverticulosis or diverticulitis) or according to severity (asymptomatic vs symptomatic or uncomplicated vs complicated). We were also not able to distinguish histological inflammation in diverticula from generic colonic histological inflammation. Finally, the Swedish population includes primarily Whites, and additional data regarding diverticular disease and cancer in other ethnic groups are needed.

In conclusion, within this large, population-based cohort in Sweden, diverticular disease with colorectal histopathology was associated with increased risk of developing overall cancer, even 5 years after diagnosis. Patients with diverticular disease also had a persistent increase in risk of specific cancers, such as liver cancer and lung cancer. Statistically significant excess cancer incidence was apparent in diverticular disease regardless of the histological features or inpatient or outpatient status. Given the prevalence of diverticular disease is high, these results highlight the need for awareness and preventive strategies such as lifestyle modifications for cancer, not only for CRC, in patients with diverticular disease. Additional research is needed to explore the biological mechanisms underlying the association between diverticular disease and cancer and examine if diverticular disease is associated with total and cause-specific mortality.

Funding

The work is supported by the Swedish Cancer Foundation (JFL). WM reported support from MGH Executive Committee on Research Tosteson and Fund for Medical Discovery Postdoctoral Fellowship Award and American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award (AGA2021-13-01). ATC and LLS reported support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK101495). Dr Chan was supported by a Stuart and Suzanne Steele MGH Research Scholar Award.

Notes

Role of the funder: The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: ATC served as a consultant for Pfizer Inc, Bayer Pharma AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim for work unrelated to the topic. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: JFL, OO; formal analysis: MT; writing—original draft: WM; writing—review and editing: all authors.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Wenjie Ma, Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit and Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Marjorie M Walker, Department of Anatomical Pathology, Faculty of Health and Medicine, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia.

Marcus Thuresson, Statisticon AB, Uppsala, Sweden.

Bjorn Roelstraete, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Filip Sköldberg, Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Ola Olén, Division of Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Sachs’ Children and Youth Hospital, Stockholm South General Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden.

Lisa L Strate, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Andrew T Chan, Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit and Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Cancer Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Jonas F Ludvigsson, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Pediatrics, Orebro University Hospital, Orebro, Sweden; Department of Medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY, USA.

Data availability

In accordance with Swedish regulation the data from this study are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Everhart JE, Ruhl CE.. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):741-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tursi A, Scarpignato C, Strate LL, et al. Colonic diverticular disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Dig Dis. 2012;30(1):35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strate LL, Keeley BR, Cao Y, et al. Western dietary pattern increases, and prudent dietary pattern decreases, risk of incident diverticulitis in a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1023-1030.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strate LL, Morris AM.. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1282-1298.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strate LL, Erichsen R, Horvath-Puho E, et al. Diverticular disease is associated with increased risk of subsequent arterial and venous thromboembolic events. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(10):1695-1701.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tam I, Liu PH, Ma W, et al. History of diverticulitis and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in men: a cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(4):1337-1344. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06949-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma W, Jovani M, Nguyen LH, et al. Association between inflammatory diets, circulating markers of inflammation, and risk of diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(10):2279-2286 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coussens LM, Werb Z.. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Granlund J, Svensson T, Granath F, et al. Diverticular disease and the risk of colon cancer - a population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(6):675-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang WY, Lin CC, Jen YM, et al. Association between colonic diverticular disease and colorectal cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1288-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azhar N, Buchwald P, Ansari HZ, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer following CT-verified acute diverticulitis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(10):1406-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaruvongvanich V, Upala S, Sanguankeo A.. Association between diverticulosis and colonic neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mortensen LQ, Burcharth J, Andresen K, et al. An 18-year nationwide cohort study on the association between diverticulitis and colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):954-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tomer N, Chakravarty D, Ratnani P, et al. Impact of diverticular disease on prostate cancer risk among hypertensive men [published online ahead of print]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41391-021-00454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomsen L, Troelsen FS, Nagy D, et al. Venous thromboembolism and risk of cancer in patients with diverticular disease: a Danish population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:735-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ludvigsson JF, Lashkariani M.. Cohort profile: ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden). Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:101-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosemar A, Angeras U, Rosengren A.. Body mass index and diverticular disease: a 28-year follow-up study in men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(4):450-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erichsen R, Strate L, Sorensen HT, et al. Positive predictive values of the International Classification of Disease, 10th edition diagnoses codes for diverticular disease in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:139-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, et al. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olen O, et al. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(4):423-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bergman D, Hagstrom H, Capusan AJ, et al. Incidence of ICD-based diagnoses of alcohol-related disorders and diseases from Swedish nationwide registers and suggestions for coding. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:1433-1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu CS, Pinsky PF, Kramer BS, et al. The prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial and its associated research resource. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(22):1684-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2345-2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peery AF. Management of colonic diverticulitis. BMJ. 2021;372:n72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tursi A, Elisei W.. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:8328490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, et al. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(10):1486-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barbara G, Scaioli E, Barbaro MR, et al. Gut microbiota, metabolome and immune signatures in patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease. Gut. 2017;66(7):1252-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, et al. Predictive value of serologic markers of degree of histologic damage in acute uncomplicated colonic diverticulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(10):702-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schultz JK, Azhar N, Binda GA, et al. European Society of Coloproctology: guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the colon. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(S2):5-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

In accordance with Swedish regulation the data from this study are not publicly available.