Abstract

Lysine methylation can modify non-covalent interactions by altering lysine’s hydrophobicity as well as its electronic structure. While ramifications of the former are documented, the effects of the latter remain largely unknown. Understanding electronic structure is important for determining how biological methylation modulates protein-protein binding, and how artificial methylation impacts experiments in which methylated lysines are used as spectroscopic probes and protein crystallization facilitators. Benchmarked first principles calculations undertaken here reveal that methyl-induced polarization weakens electrostatic attraction of amines with protein functional groups – salt bridges, hydrogen bonds and cation-π interactions weaken by as much as 10.3, 7.9 and 3.5 kT, respectively. Multipole analysis shows that weakened electrostatics is due to altered inductive effects that overcome increased attraction from methyl-enhanced polarizability and dispersion. These effects, due to their fundamental nature, are expected to be present in many cases. Survey of methylated lysines in protein structures reveals several cases where methyl-induced polarization is the primary driver of altered non-covalent interactions, and in these cases, destabilizations are found to be in the 0.6–4.7 kT range. The clearest case of where methyl-induced polarization plays a dominant role in regulating biological function is that of the PHD1-PHD2 domain that recognizes lysine methylated-states on histones. These results broaden our understanding of how methylation modulates non-covalent interactions.

Keywords: Electronic Polarization, Inductive Effects, Lysine Methylation, Noncovalent Interactions, Quantum Chemistry

Graphical Abstract

Ammonium methylation weakens its electrostatic attraction with protein functional groups – salt bridges, hydrogen bonds and cation-π interactions weaken by as much as 10.3, 7.9 and 3.5 kT, respectively. Weakened electrostatics is due to altered inductive effects that overcome increased attraction from methyl-enhanced polarizability and dispersion. These effects, due to their fundamental nature, are expected to be present in many cases.

Introduction

Protein methylation[1] is a key regulator of protein-protein binding.[2–4] Changes in protein-protein binding induced by methylation result in many different downstream effects, including those involved in gene expression, DNA repair and apoptosis. Methylation is tightly regulated in eukaryotic cells by the dynamic writing and erasing activities of methyltransferases and demethylases. Aberrations in methylation are associated with several physiological disorders, including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.[2–7]

Here we focus on N-methylation of lysines in which lysine’s side chain amine group accepts up to three methyl groups. Lysine N-methylation does not change lysine’s positive charge, which is, in fact, important to the binding of methylated lysines to methyllysine binding domains of proteins.[8,9] Experiments also show that the specific length of lysine’s side chain,[10] as well as the chemistries of aromatic groups present in methyllysine binding sites are important to the binding of methylated lysines.[11–14]

There are many different methyllysine recognizing protein domains, and each of them is known to have a preference for a specific methylated state of lysine.[15–30] Some preferentially bind to higher methylated states while others prefer binding to lower methylated states of lysines. Their preferences have been rationalized using lysine’s altered hydrophobicity,[4,7] structural features present in methyllysine binding sites,[16,18–21,26,27,30] and presence of binding site functional groups that can engage in hydrogen bonds.[18–20,24,26,27,29–33]

In a recent study,[34] where we proposed a new QM/MM method to predict the effect of lysine methylation of protein-protein binding free energies, we assessed the specific contributions of these features on methylation-state selectivity. We reported that the contributions of these features can be understood in terms of two energetics-based guiding principles. Firstly, methylation, in general, weakens mutual interactions between proteins, which drives binding in favor of lower methylated states. Secondly, methylation lowers the desolvation penalties of proteins, which improve their favorability to engage in binding to other proteins. This latter effect, which results from increased hydrophobicity, biases binding in favor of higher methylated states. The overall effect of methylation on protein-protein binding free energy depends on the balance between these two energetic effects. Survey of methyllysine binding domains indicated that this balance is imparted through several combinations of features outlined above, however, none uniquely determined methylation-state selectivity. In addition, we identified a moderate correlation between selectivity and the extent of which methyl groups are exposed to solvent in complexed states.

Aside from binding site structural/chemical features and altered hydrophobicity modulating methylation-state selectivity, methyl-induced changes in lysine’s electronic structure can also be expected to affect methyllysine binding preferences. Methylation enhances dispersion, which is suggested to drive affinity toward higher methylated states,[15,24] although our recent study[34] revealed no correlation between dispersion changes and methylation-state selectivity. Methyl groups also have a higher polarizability compared to the hydrogens they replace.[35] Therefore, methylation of lysines should increase its polarizability, which could, in turn, strengthen lysine’s non-covalent interactions. In fact, methyl polarizability has been shown to strengthen ion-ligand interactions by several kT (k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature).[36] Finally, methyl groups are also more electronegative than the hydrogens they replace,[37] and so methylation can alter lysine’s permanent electrostatic moments (inductive effect) and impact lysine’s non-covalent interactions.

The relevance of these polarization effects on lysine’s non-bonded interactions goes beyond understanding their effects on protein-protein binding. Over the past decades, lysine alkylation has become an increasingly important tool in biophysical experiments. Specifically, proteins are reductively methylated to facilitate their crystallization for structure determination by X-ray diffraction.[38–40] Lysine methylation is also used for studying protein structure and dynamics by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) experiments, where 13C methyl groups serve as high-sensitivity probes.[41–44] A fundamental understanding of how methyl-induced electronic polarization affects lysine’s non-covalent interactions should benefit the interpretation of results from such experiments.

Experiments have provided important, but limited insights into the effect of methyl-induced polarization on lysine’s non-covalent interactions, and the potential impact that they may have on macroscopic observables. Firstly, gas phase experiments have shown that mono-methylation of ammonium ion decreases its binding free energy with benzene by 0.8 kT.[45] Accompanying quantum mechanical studies,[45] as well as subsequent ones[46,47] indicated that this affinity drop corresponds to a scenario in which the methyl group is added away from the dimer interface, and not at the interface where it will increase cation-π distance. In such a scenario, methyl-induced polarization becomes the dominant driver of altered interactions. Does this imply that ammonium or lysine methylation will also impact their respective affinities with other biochemical groups? If so, then what are the nature and extent of such affinity changes? Secondly, early NMR studies on model systems and proteins,[41] and also more recent studies,[42] have shown systematic effects of lysine methylation on lysine’s pKa, where pKa shifts of more than one unit have been observed. Thirdly, experiments have shown systematic effects of lysine methylation on absorbance spectra in Bradford assays, which indicate that lysine methylation alters lysine’s electrostatic interactions with negatively charged sulfonate groups in the buffer.[48]

The primary challenge associated with investigating polarization effects is to describe accurately the broad range of molecular forces, in particular, charge-redistribution, polarizability and dispersion, which contribute nontrivially to local energetics. A first-principles approach is, therefore, required. Toward this end, we first use “gold-standard” coupled cluster theory with single, double and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) to determine how ammonium methylation changes its dimerization energies with a diverse set of small molecules representing the various chemical groups present in methyllysine binding sites. To understand the physical bases underlying methylation-induced changes in dimerization energies, we analyze contributions from electrostatics, inductive effects, polarizability and dispersion. We then use the CCSD(T) reference data to benchmark a vdW-inclusive density functional theory (DFT) and use it to examine systems containing more than two molecules and determine contributions from many-body terms. Finally, we use benchmarked vdW-inclusive DFT to assess the effects of lysine methylation on non-covalent interactions in protein environments, and also analyze the implications of these findings in modulating methylation-state selectivity.

Results and discussion

Effect of methyl-induced polarization in model systems

We first compute the effect of ammonium methylation on its dimerization energies with four biochemical groups – hydroxyls, carbonyls and carboxylates and aromatics. These biochemical groups are typically found in methyllysine binding pockets, and, in general, also interact with unmethylated lysines in protein environments.[49] We use methanol to represent hydroxyls, formamide to represent carbonyls, formate to represent carboxylates and benzene to represent aromatic groups. We also examine the effect of ammonium methylation on its dimerization energies with two other aromatic groups, phenol and indole. These molecules represent tyrosines and tryptophans, respectively, found frequently in binding pockets of methyllysine reading domains,[49] and there are ongoing efforts to understand their relative roles in binding and selectivity.[12,14]

In these heterodimers, ammonium ions can be methylated in two ways, one in which the methyl groups are added away from the dimer interface, and the other in which methylation interferes physically (sterically) with the dimerization interface. We first consider the former scenario, where changes in dimerization energies will be dominated by changes in electronic structure. For this, we consider monomethylation (Me1), di-methylation (Me2) and trimethylation (Me3) of ammonium. Note that tetra-methylation (Me4) of ammonium ions will interfere directly with its dimerization interfaces, as discussed, a bit later in this subsection.

We compute heterodimer binding energies as

| (1) |

where Edimer is the energy of the isolated dimer, and E1 and E2 are the energies of isolated small molecules. In these calculations, heterodimers as well as the individual molecules are all subjected to separate geometry relaxations using PBE0+vdW, and the relaxed geometries are then used for compute ΔE2body from LNO-CCSD(T) in the complete basis set (CBS) limit. During geometry relaxation, no restraints are placed on atoms except in the cases of interactions with formates, where the ammonium (or methylammonium) nitrogen and the formate carbon are constrained at a distance of 4.2 Å to prevent intermolecular proton transfer.

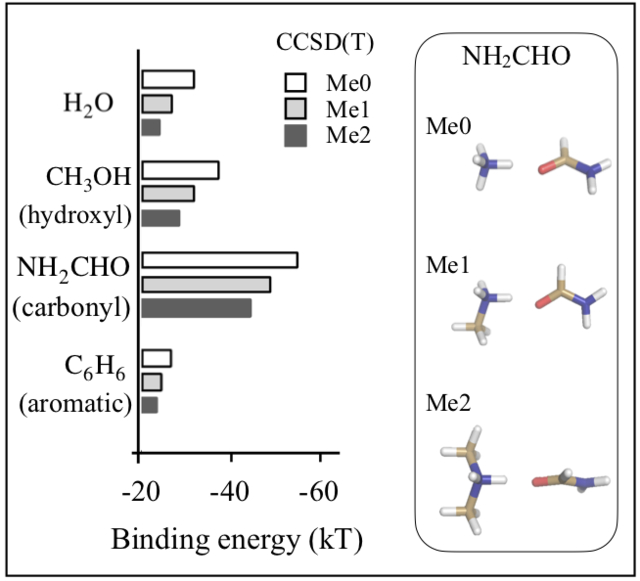

Figure 1 shows the results of these calculations. We note that ammonium methylation reduces its affinities with all biochemical groups. Additionally, in all cases, we note that increased methylation results in larger drops in affinity. The highest affinity drop is noted in the case of ammonium-formate dimers, where mono-methylation weakens binding by 5.9 kT and di-methylation weakens binding by 10.3 kT. In ammonium binding to water, methanol and formamide, mono-methylation weakens hydrogen bonds effectively by, respectively, 3.5, 4.2 and 4.7 kT, and di-methylation weakens them by 5.9, 6.8 and 7.9 kT. Ammonium methylation also weakens cation-π interactions, although the effect of methylation is the smallest among these cases. Mono- and di-methylation result in, respectively, 1.6 kT and 2.3 kT drops in binding energy with benzene. A similar effect is also noted for interactions of ammonium ions with phenol and indole. Consistent with earlier work,[14] we also note that the methylated ammonium ions bind most strongly to indole, followed by phenol and benzene. Overall, we find that in the scenario where methyl groups are added away from the dimer interface, dimer affinities drop substantially.

Figure 1:

Binding energies (ΔE2body) of methylated ammonium ions with small molecules determined from LNO-CCSD(T)/CBS. Me0, Me1, Me2, Me3 and Me4 refer, respectively, to unmethylated, monomethylated, dimethylated, trimethylated and tetramethylated states of ammonium ion. The plotted ΔE2body values are also listed in Table S1 of the Supplementary Information. The inset on the right provides geometries of ammonium-benzene dimers in their energy minimized conformations. Geometries of ammonium dimers with other small molecules are provided in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Information.

In the alternative scenario where methylation interferes directly with dimerization interfaces, affinity drops will be even larger. In ammonium interactions with water, methanol and formamide, such a methylation will break hydrogen bonds, and in interactions with formate, this will break ammonium-carboxylate salt bridge. Finally, in the case of ammonium interactions with aromatic groups, this will increase cation-π distance. The expected larger drop in affinity associated with methyl groups interfering with dimerization interfaces can also be gauged from the substantial drop in affinity associated with ammonium tetramethylation compared to ammonium mono-, di- or trimethylation (Figure 1).

Next, we examine how ammonium methylation negatively impacts interaction energies without interfering directly with dimerization interfaces.

Competing actions of altered inductive effects and altered polarizability

In principle, methylation can alter interactions without interfering with dimerization interfaces by altering ammonium’s zero-field electron density (inductive effect) and its field response. The latter will expectedly strengthen interactions. Therefore, the observed negative impact is due to altered inductive effects, whose contributions should be large enough to overcome stabilization from enhanced polarizability and dispersion. In the heterodimers studied above, ammonium methylation does enhance dispersion, but other than those involving aromatics, its energetic contribution is relatively small (Table S2 of the Supplementary Information). The higher stabilization from dispersion in the case of aromatics perhaps explains why ammonium methylation has the smallest effect on its interaction with them.

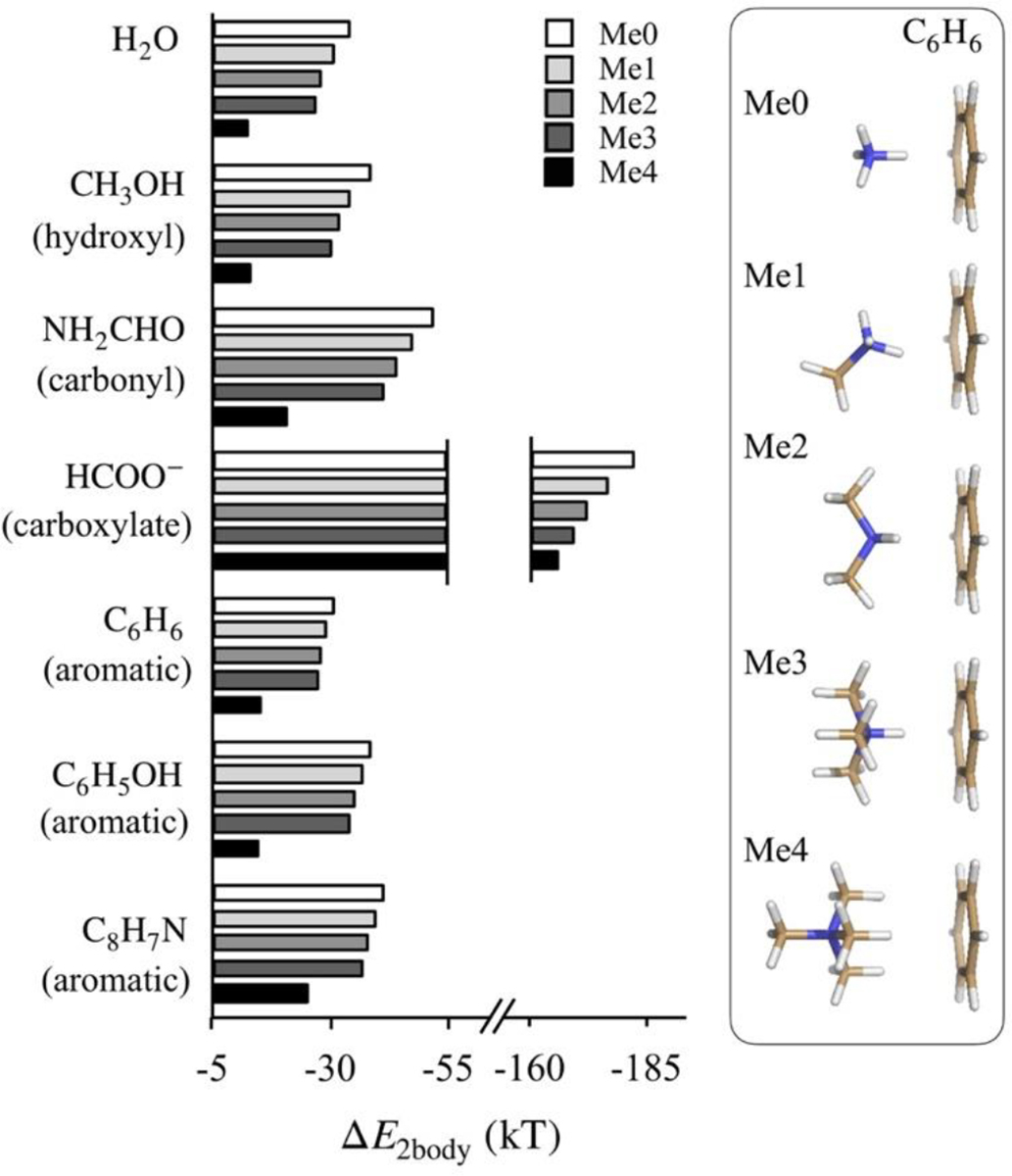

To examine quantitatively the relationship between altered polarizability and inductive effects, we compare electron densities of ammonium and methylammoniun ions as a function of an applied external electric field. To compare electron densities, we use multipole expansion. For this we define a common reference frame in which nitrogen atoms are placed at the origin, and one of their N-H bond vectors are aligned () (Figure 2a). The hydrogen atoms of these vectors are the ones that would interact directly with dimeric partners. Electron densities are obtained from Moller-Plesset second-order perturbation (MP2) theory.[50]

Figure 2:

Effect of ammonium methylation on electrostatic interactions. (a) Coordinate frame for calculating multipoles of ammonium and methylammonium ions. Nitrogen atoms are placed at the origin, and a negative point charge is placed along one of their respective N-H bond vectors (). and are the components of permanent dipoles and quadrupoles along . (b) Dipole moments of ammonium and methylammonium ions as functions of their respective distances |r| from point charges. Note that the distance |r| is represented in terms of the electric field ξr generated by the negative point charge at the location of nitrogen atoms, and so a field of ξr = 0 represents an isolated molecule with . The vertical dashed lines denote electric fields generated by small molecules at the nitrogen atoms of ammonium and methylammonium ions in their respective dimers listed in Figure 1. ΔEΔμ is the difference between the interaction energies of methylammonium and ammonium dipoles with point charges. (c) Quadrupole moments of ammonium and methylammonium ions as a function of distance |r| from point charge. Also shown is the difference between their interaction energies with point charge, ΔEΔQ.

The results of these calculations are shown in Figure 2. We note that in the absence of any applied electric field, the dipole and quadrupole moment components, μr and Qrr along , of ammonium are zero, but those of methylammonium are in the negative direction. Contributions from these permanent moments will, therefore, weaken the electrostatic attraction of methylammonium ions. These methyl-induced changes in ammonium’s permanent electrostatic moments can be understood by decomposing electron densities over atoms and functional groups using Bader’s atom-in-molecules approach (Table S3 of Supporting information).[51,52] Note that while there are no unique ways to decompose electron densities over atomic centers, the molecular dipoles and quadrupoles that we analyze below do not rely on any assumptions underlying electron density decomposition.

In the presence of a negative point charge placed along the N-H bond vector (Figure 2a), we find that the induced moments in methylammonium are larger than those in the ammonium ion. However, electric fields generated by none of the dimeric partners listed in Figure 1 are high enough for the induced moments of methylammonium to overcome the difference in permanent moments, implying that energetic contributions from these moments should make methylammoium dimers weaker compared to corresponding ammonium dimers. Figures 2b and 2c also show the effects of multipole differences on interaction energies with point charges. For dipoles, , where ξr is the electric field generated by the negative point charge at the location of nitrogen atoms. For quadrupoles, since induced moments in ammonium and methylammonium ions are similar in the range of electric fields examined, contributions of ΔEΔQ can be approximated as . At small electric fields, as produced by benzene, the differences in dipoles and quadrupoles result in a combined energetic difference of ~ 1.1 kT. At a higher field, as produced by formate, ΔEΔμ + ΔEΔQ ~ 5.6 kT. We note that these differences are nearly similar to those reported in Figure 1.

Effect of many-body interactions on methyl-induced polarization

Methyllysine binding sites in proteins comprise of multiple functional groups, and, in general, lysines in protein environments interact with multiple functional groups. This raises the question of how many-body interactions or interactions between multiple functional groups modulate the negative impact of methylation on two-body interactions. To address this, we consider trimers consisting of ammonium or methylammonium ions and two other small molecules. In these methylammonium clusters, ammonium ions are methylated at positions away from their two dimerization interfaces. We compute three-body terms as

| (2) |

where Etrimer is the energy of the trimer, Eij are energies of its constituent dimers, and Ei are the energies of its constituent monomers.[53] All energies are computed using the PBE0+vdW functional, which performs well against CCSD(T) data (see Methods). Just as in the study of dimers, the trimer geometries are subjected to geometry relaxations, however, when the monomers and dimers constituting the trimers are extracted for computing Ei and Eij, respectively, they are not subjected to further geometry relaxations.

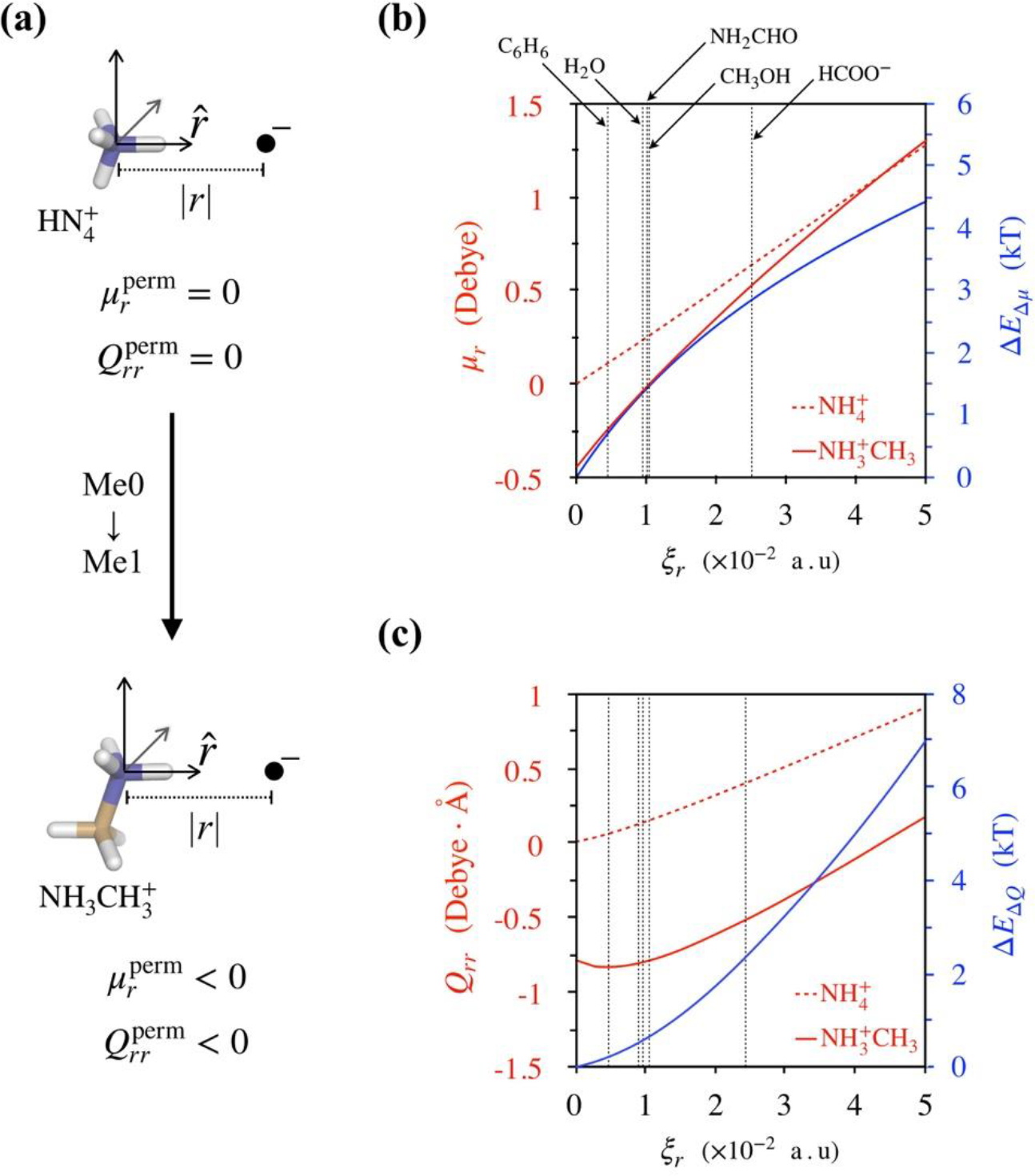

The results of these calculations are shown in Figure 3. As expected, we find that E3body is repulsive (positive). Ammonium methylation weakens this repulsive force, which implies that it would reduce the negative impact of methylation observed in two-body systems. However, except in the case of clusters containing benzenes, the effect of methylation on the magnitude of E3body is rather small compared to the destabilization brought on by methylation in two-body interactions. Therefore, in general, we can expect that the overall negative impact of altered inductive effects will be smaller. We can also expect that the overall negative impact of altered inductive effects to be only minor in methyllysine binding sites that comprise of aromatic cages. In fact, aromatic cages are a typical structural feature present in almost all methyllysine binding sites that select for higher methylated states of lysine.[49,54,55]

Figure 3:

Effect of ammonium methylation on three-body terms E3body. Ammonium methylation weakens E3body, but only slightly compared to the destabilization brought on by methylation in ammonium dimers, with the exception of clusters containing benzenes.

Effect of methyl-induced polarization in protein environments

Interaction geometries in protein environments are expectedly different from those considered in model systems above and, therefore, the overall effects of electronic-level changes observed in protein environments can be different from those observed in model systems.[46] Furthermore, dispersion contributions from methylation can also be expected to be higher in denser non-bonded complexes, which could help negate the negative impacts from changes in inductive effects.

To examine this and also gauge the extent of this destabilization in protein environments, we extract local environments of thirty methylated lysines from the protein data bank (PDB) – ten each of mono-, di- and tri-methylated states. An amino acid is considered to be part of a local environment if any of its atoms are within 6 Å from the lysine amine nitrogen. In all of these cases, coordinates of lysine’s methyl carbons were resolved. Details of these 30 cases are provided in Table S4 of the Supporting Information. Note that this test set includes both naturally occurring and artificially engineered methylations.

In these clusters, we determine how de-methylation of lysine alters its interaction energies with the cluster, that is, we determine

| (3) |

Here and are the energies of the clusters containing lysines in their methylated and un-methylation states, respectively. and are, respectively, the energies of an isolated lysine side chain (butylammonium) in its methylated and un-methylation states. and are determined from relaxed geometries, and their lowest energy conformations are selected from sets of twenty random structures after subjecting each one of them to separate geometry relaxation.

and are computed after adding missing hydrogens, capping the non-contiguous backbones and relaxing geometries with position constraints on backbone heavy atoms. By applying position constraints on backbones, we make the physical assumption that while side chains are free to move during relaxation, methylation does not alter protein secondary structure. All calculations are performed using the PBE0+vdW density functional (see Methods for comparison between predictions from PBE0+vdW and CCSD(T)).

Based on the studies above of ammonium ion interactions, we expect that lysine demethylation will, in general, strengthen interactions, that is, −ΔEdMe > 0. This is also supported by our calculations in Tables S3 and S5 of the Supplementary Information, which show that methylation-induced charge-redistribution in lysines (butylammonium) is similar to that in ammonium ions, and methylation-induced changes in ΔE2body of lysine (butylammonium) dimers are similar to those of ammonium dimers.

As discussed in a previous section, de-methylation induced strengthening (or methylation induced weakening) could be due to two reasons. Firstly, it could be due to decrease in distances between lysines and the functional groups in the cluster. Such a compaction of the cluster will occur if lysine methylation had interfered physically with lysine’s interactions with cluster functional groups. Secondly, it could be due primarily to changes in lysine’s electronic structure, and in such cases, de-methylation will not alter distances between lysines and cluster functional groups. To differentiate between these two mechanisms, we quantify the extent to which lysine de-methylation alters distances between lysine and the interacting cluster. For this, we determine , where the superscripts designate methylation states, di are distances between lysine amine nitrogens and the heavy atoms in the cluster, and n denotes the number of heavy atoms in the cluster that were not constrained during optimization. In addition, we determine , and a Δd′ < 0 would imply a cluster compaction resulting from lysine de-methylation.

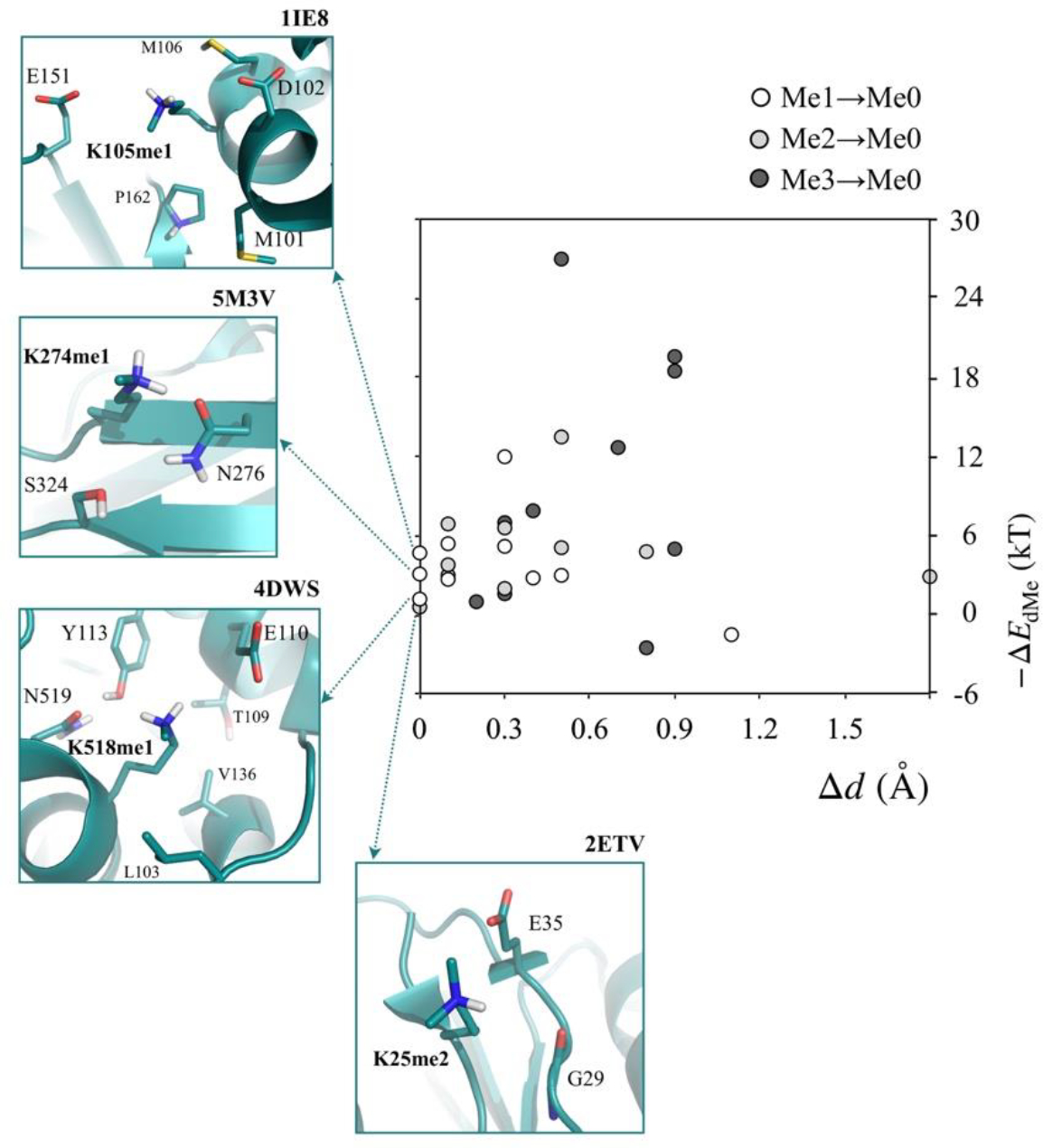

Figure 4 shows the relationship between ΔEdMe and Δd. We note first that in all, but two cases, lysine de-methylation strengthens its interactions with the cluster. The two cases in which de-methylation weakens interactions, instead of strengthening them, are due to breakage of hydrogen bonds present in the methylated state, as discussed in Figure S2 of the Supporting Information. The next observation we make is that in most cases where −ΔEdMe > 0, lysine de-methylation also alters distances between lysine amine nitrogens and the heavy atoms in the cluster. Examination of Δd′ (Table S4 of Supplementary Information) shows that in these cases, de-methylation compacts binding sites, and so in these cases structural compaction contributes to strengthened interactions.

Figure 4:

Effects of lysine de-methylation on their interaction energies with clusters (ΔEdMe) and average distances of their amine nitrogens from cluster heavy atoms (Δd). Also shown are the local structures of the four cases where de-methylated resulted no structural change, that is, Δd < 0.05 Å.

We also identify four cases in which de-methylation strengthens interactions without changes in distances between lysine amine nitrogen and cluster heavy atoms (Δd < 0.05 Å). In these four cases, interactions strengthen due primarily to methylation-induced changes in lysine’s electronic structure. The observed range in −ΔEdMe is between 0.6 and 4.7 kT. The local environments of these four cases are shown in Figure 4. In the 1IE8 (PDB ID) case, we note that K105 interacts with two negatively charged residues, D102 and E151, and based on studies of model systems above, its de-methylation should strengthen its electrostatic moments, which would increase electrostatic attraction. The overall effect is, however, weaker than that expected from results on 2-body systems, and we attribute this to three factors: longer salt-bridge distances compared to those present in 2-body systems, presence of many-body interactions, and increased contribution of dispersion. In the 5M3V case, K274 demethylation essentially strengthens its hydrogen bond with N276. In the 4DWS case, K518 de-methylation strengthens its salt bridge with E110 and also its electrostatic attraction to N519 and Y113. Finally, in the 2ETV case, K25 de-methylation strengthens its electrostatic interaction with E35 and the backbone carbonyl of G29.

While this survey provides a clear set of examples of the effect of methyl-induced changes in electronic structure on non-covalent interactions, it does not directly suggest any biological role of electronic structure changes. In all four cases, we note that lysines were methylated artificially to improve protein crystallization. [56–58]

Biological role of methyl-induced polarization

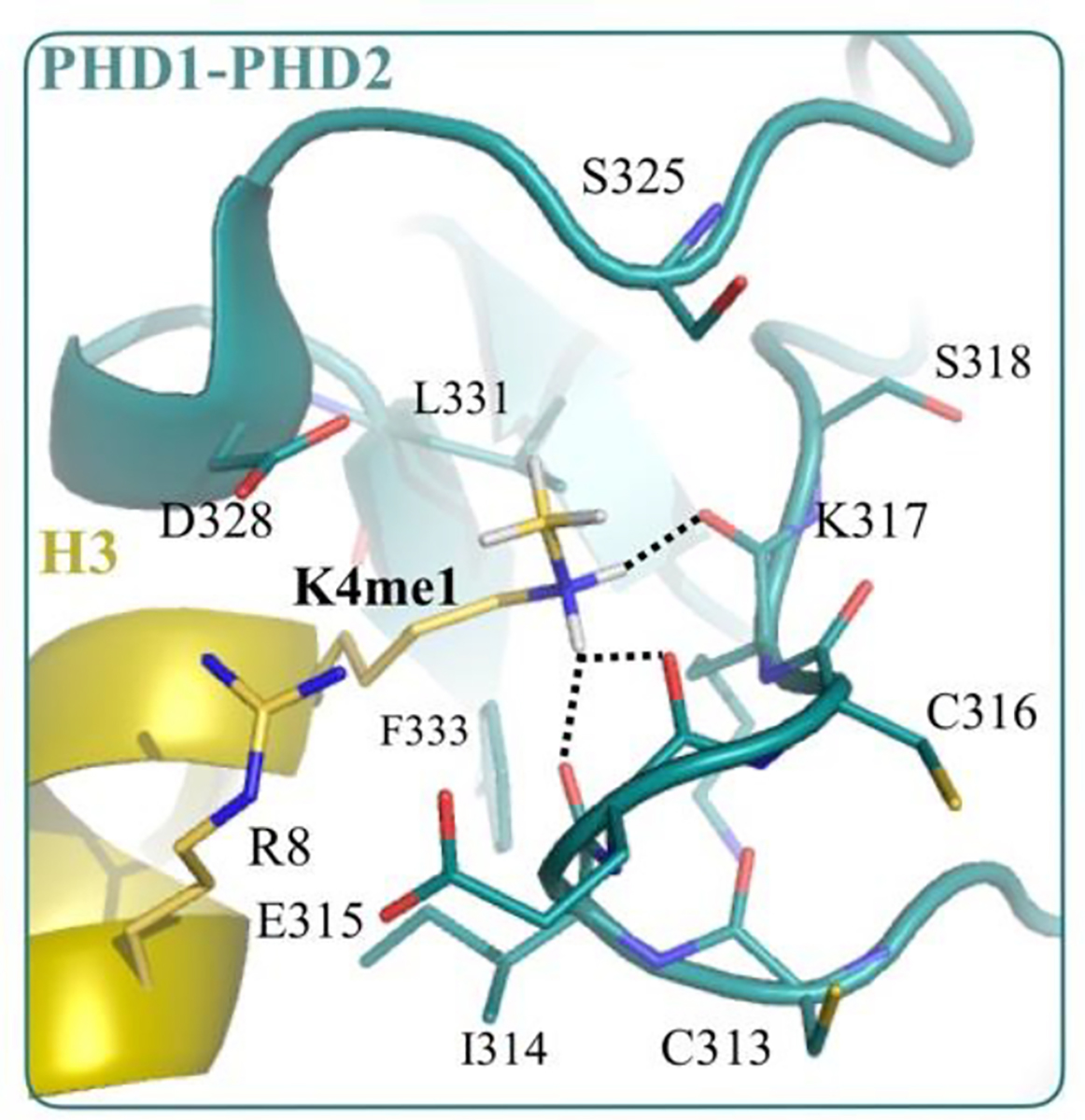

To examine the biological role of methylation-induced changes in electronic structure, we examine the set of fourteen cases that we studied recently[34] where biological methylation is used by cells to alter protein-protein binding for regulating cellular processes. We had found one specific case in which the effect of methylation on protein-protein binding free energy could not be rationalized in terms of lysine’s altered hydrophobicity or local features present in its methyllysine binding pockets. This belonged to the PHD1-PHD2 domain, which helps the BRG1/BRM-associated factor (BAF) complex recognize methylated lysines on histone tail to control chromatin remodeling for gene transcription.[59] Kinetic experiments show that, in its isolated form, the PHD1-PHD2 domain binds to a histone-derived peptide more strongly when its lysine (K4) is unmethylated compared to when the lysine is monomethylated.[30] The binding free energy difference between the two states is kT.

This selective preference could not be rationalized in terms of binding site structural features because X-ray structural studies show that peptide lysine methylation has a negligible effect on the structure of its complex with PHD1-PHD2 (Cα RMSD < 0.04 Å).[30] In the absence of structural change, methylation should have strengthened binding free energy, and not weakened it, as methylation makes it easier to partially dehydrate a methylated protein (hydrophobic effect) and place it into a protein-protein complex.[34,60]

Nevertheless, our QM/MM calculations, which reproduced experimental , also showed that the main driving factor that offsets the peptide’s altered dehydration penalty was the methylation-induced drop in mutual interaction between peptide and PHD1-PHD2 domain. Our computed −ΔEdMe = 3.5 kT, which offsets the effect of methylation on hydration energy to yield a computed kT. The decrease in mutual interaction in the absence of structural change can now be rationalized on the basis of the effect that methylation has on electronic structure. Figure 5 shows the local environment of the methylated lysine in the peptide complexed with the PHD1-PHD2 domain. Lysine’s amine group hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyls of residues I314, E315 and K317 belonging to the PHD1-PHD2 domain, and based on our studies on model systems, it is clear that lysine methylation reduces the strengths of these hydrogen bonds, thereby negatively impacting the electrostatic attraction between lysine and the PHD1-PHD2 domain. This drop in electrostatic attraction is due to altered inductive effects that alter lysine’s multipoles. This provides direct evidence for the biological role of inductive effect altered by methylation.

Figure 5:

Local environment of methylated lysine in the complex formed between PHD1PHD2 domain (green) and a peptide (yellow) derived from Histone H3 tail (PDB ID: 5SZC). The dotted black lines indicate hydrogen bonds between lysine amine and the backbone carbonyls of residues I314, E315 and K317 belonging to the PHD1-PHD2 domain. The structure of complex in the unmethylated K4 state (PDB ID: 5SZB) is almost identical to this complex, with no change in hydrogen bond network. The hydrogens were not resolved in the X-ray structure, and their positions were obtained from QM energy minimization, as reported in our previous study.[34]

Conclusions

Lysine methylation can alter non-covalent interactions by changing lysine’s hydrophobicity as well as its electronic structure. While the consequences of lysine methylation on hydrophobicity are well-documented, the specific effects of methyl-induced changes in electronic structure on lysine’s non-covalent interactions remain largely unknown. Understanding these effects is important for determining how biological methylation modulates protein-protein binding, and how artificial methylation impacts experiments in which lysines are methylated to facilitate protein crystallization and create NMR probes.

Here we take a systematic approach to study the role of methyl-induced polarization in modulating lysine’s non-bonded interactions in model systems as well as protein environments. In model systems, we find that methylation rearranges the zero-field electron density (inductive effect) of lysine’s amine group and introduces permanent multipoles that weaken its electrostatic attraction with protein functional groups. Expectedly, methylation also increases stabilizing contributions by enhancing polarizability and dispersion, but we find that their combined energetic effect is smaller than the impact from altered inductive effects. Consequently, these methyl-induced changes in electronic structure weaken the non-covalent interactions of amines.

The magnitude of the negative impact depends on the extent of methylation as well as the type of the interaction. It is noted to be the largest for salt bridges and the smallest for cation-π interactions. In ideal situations, di-methylation can weaken salt-bridges by as much as 10.3 kT, hydrogen bonds by 7.9 kT and cation-π interactions by 3.5 kT. In essence, these findings provide a molecular basis for the systematic effect of methylation on the absorbance spectra in Bradford assays that depend on electrostatic interactions of lysines with negatively charged groups in the buffer.[48] Our calculations also show that many-body interactions reduce the magnitude of the negative impact of methylation observed in two-body systems (heterodimers). Therefore, in typical lysine sites in proteins, the negative impact can be expected to be smaller even when lysine interactions are at ideal distances.

These effects, due to their fundamental nature, will expectedly be present in many cases. A survey of naturally occurring and engineered methylated lysines in proteins reveals a clear set of cases in which methyl-induced changes in electronic structure plays a dominant role in modulating non-covalent interactions. In these test cases, methyl-induced polarization is noted to weaken lysine’s non-covalent interactions in the range of 0.6 to 4.7 kT. A more extensive survey will provide a better quantification for the magnitude and range of polarization effects.

In principle, such changes in non-covalent interaction energies can potentially modulate both protein structure and dynamics. Early experiments on a lysozyme,[38] however, indicated only little effects of lysine methylation on structure, with the larger changes limited to surface loops. Therefore, perhaps such a change in electrostatics is not large enough to modulate intrinsic protein structure under low-temperature crystallographic conditions. Nevertheless, these results do recommend a more detailed and targeted study. Additionally, these results also recommend evaluating the effect of lysine methylation on protein dynamics. This is because altered interaction energies typically imply altered thermal fluctuations, and such changes in interactions could impact the interpretations of dynamics studied in NMR experiments where methylated lysines are themselves used as probes for recording protein dynamics.[42,43]

From a biological standpoint, these observed effects explain the selective preference of PHD1-PHD2 domains for histone methylation states, linking methyl-induced polarization effects to their biological role. In chromatin, the methylation of histone lysine is tightly regulated, serving as a major constituent within the epigenetic landscape.[61] Specifically, lysine methylation regulates transcriptional activity by recruiting chromatin readers and orchestrating the deposition of other posttranslational modifications.[49,62] Furthermore, lysine methylation on non-histone proteins regulates a variety of biochemical pathways including DNA repair and cell signaling.[63]

In light of these findings, we anticipate future studies examining the specific roles of electronic polarization in other types of protein and DNA methylations, including arginine N-methylation, and different forms O- and C-methylation, all of which play vital roles in biological processes. In fact, in arginine N-methylation, polarization effects have been suggested to contribute to methylation-state selectivity,[64] although specifics remain undetermined. We also anticipate that our energetic and structural data will have direct implications in guiding ongoing efforts to design synthetic receptors for methylated amino acids with applications in sensing, tagging and enzymatic assays.[65,66] Additionally, we also expect them to facilitate the development of therapeutic molecules targeting methyl-lysine binding proteins.[67,68]

Methods

CCSD(T) calculations

CCSD(T), with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation,[69,70] is used for computing two-body binding energies, ΔE2body, of methylated ammonium ions for all structures energy-optimized via the vdW-inclusive DFT method described below. CCSD(T) calculations are accelerated by the local natural orbital (LNO) scheme[71,72] of the MRCC suite of quantum chemical programs.[73,74] The LNO-CCSD(T) results are extrapolated toward the approximation-free CCSD(T) energy using the Tight and very Tight LNO threshold sets.[72,75] Corresponding local error estimates are assigned to the extrapolated energies following Ref. 75. Dunning’s augmented correlation-consistent basis sets (aug-cc-pVXZ, X=T, Q, 5) and the frozen core approach are utilized. A basis set incompleteness (BSI) error estimate is also assigned to the CBS(Q,5) interaction energies obtained by the difference of CCSD(T)/CBS(Q,5) and CCSD(T)/CBS(T,Q) energies. The resulting error estimates accounting for both local and BSI uncertainties indicate that the reported LNO-CCSD(T)/CBS(Q,5) interaction energies approach the approximation-free CCSD(T)/CBS ones within ±0.3 kT.

vdW-inclusive DFT calculations

The hybrid PBE0 exchange-correlation functional,[76–78] with self-consistent corrections for dispersion (PBE0+vdW),[79] is used for computing 2-body binding energies (ΔE2body) of methylated lysines, carrying out many-body analysis of model systems, and also for computing ΔEdMe for clusters taken from protein structures. These calculations are performed using the FHI-AIMS package[80] with ‘really tight’ basis sets. Electron densities are converged to within 10−5 electrons, and total energies are converged to within 10−6 eV. Geometry optimizations are carried out with a force criterion of 10−3 eV/Å.

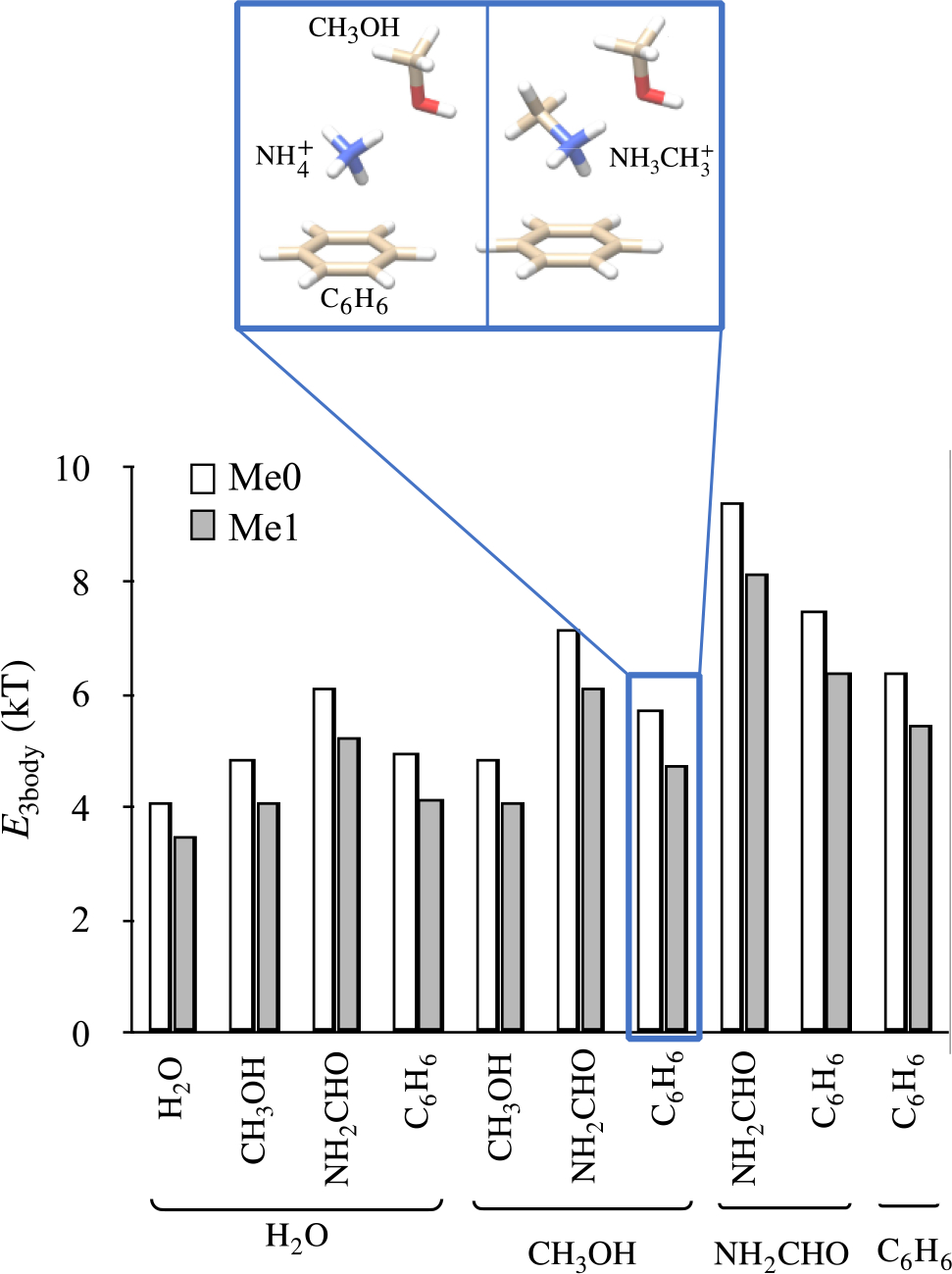

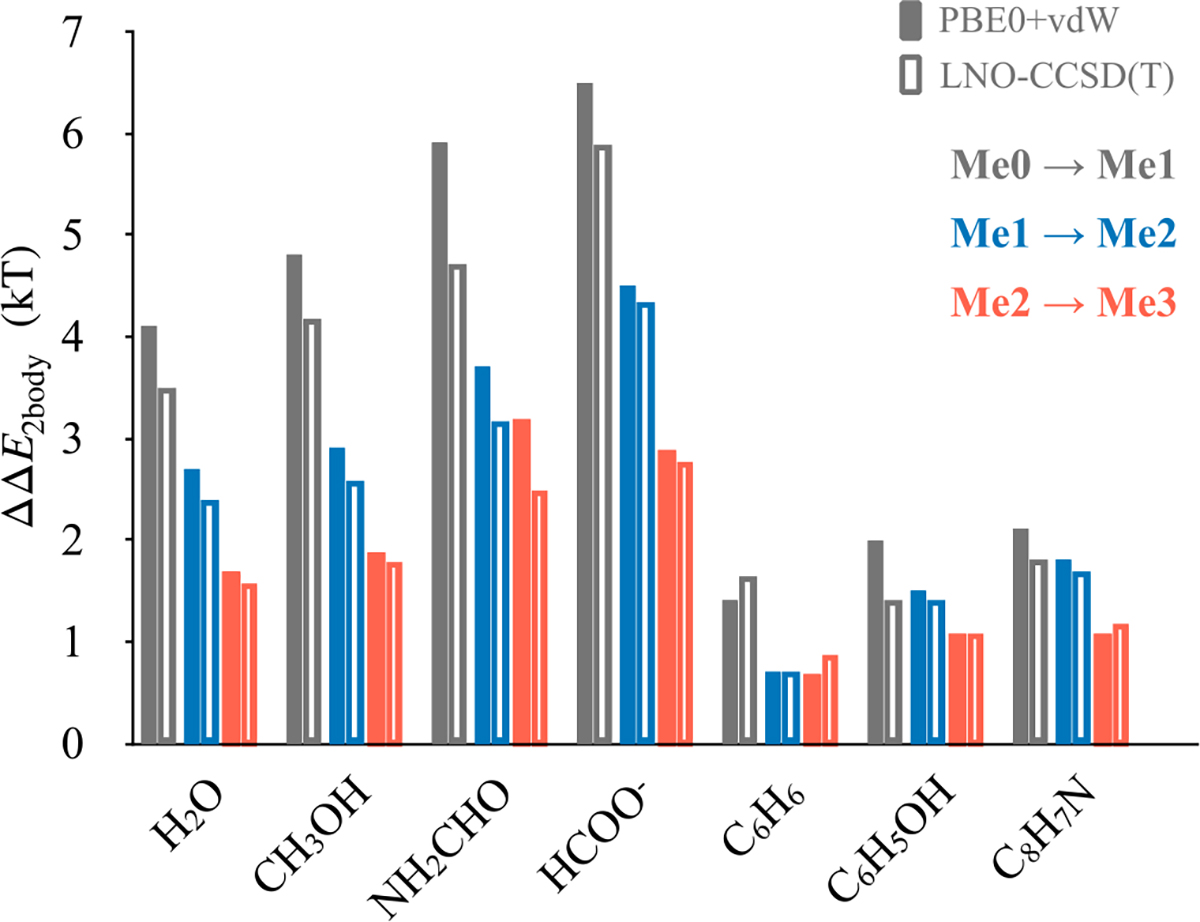

The performance of PBE0+vdW in assessed by comparison against LNO-CCSD(T). From Figure 6, we note that PBE0+vdW slightly overestimates the effect of ammonium ion methylation on ΔE2body with respect of LNO-CCSD(T), with a mean absolute deviation of 0.3 kT. This is within the range of deviations we noted previously for predictions of PBE0+vdW for small and large ion-ligand clusters against CCSD(T), quantum Monte Carlo, and also experimental gas phase energies.[36,81–83]

Figure 6:

Performance of PBE0+vdW against LNO-CCSD(T) in estimating the effect of ammonium methylation on its binding energy with small molecules (ΔΔE2body). Me0, Me1, Me2 and Me3 refer, respectively, to unmethylated, monomethylated, demethylated and trimethylated states of ammonium ion.

MP2 calculations

MP2 theory[50] implemented in Gaussian09[84] is used for computing the dipole and quadrupole moments shown in Figure 2. We use the Dunning’s correlation-consistent basis sets with diffuse functions and note that the difference between values computed using aug-cc-pVTZ and aug-cc-pVQZ basis sets is marginal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of computer time from Research Computing at USF, UL and the DECI resource SAGA (PRACE NN9914K). The authors are also grateful to the National Institute of Health for partially funding this study through grant numbers R01GM118697 and R01-AA026082. PRN is grateful for financial support of NKFIH, Grant No. KKP126451, ÚNKP-20-5 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology and the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Supporting Information contains five tables and three figures.

References

- (1).Ambler RP, Rees MW, Nature 1959, 184, 56–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lee DY, Stallcup MR, Strahl BD, Teyssier C, Endocrine Rev. 2005, 26, 147–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Paik WK, Paik DC, Kim S, Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Murn J, Shi Y, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Han D, Huang M, Wang T, Li Z, Chen Y, Liu C, Lei Z, Chu X, Cell Death & Disease 2019, 10, 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Rowe EM, Xing V, Biggar KK, Brain Research 2019, 1707, 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Luo M, Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6656–6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hughes RM, Wiggins KR, Khorasanizadeh S, Waters ML, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 11184–11188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kamps JJAG, Huang J, Poater J, Xu C, Pieters BJGE, Dong A, Min J, Sherman W, Beuming T, Bickelhaupt FM, Li H, Mecinović J, Nature Comm. 2015, 6, 8911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Al Temimi AHK, Belle R, Kumar K, Poater J, Betlem P, Pieters BJGE, Paton RS, Bickelhaupt FM, Mecinović J, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2409–2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 9459–9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Baril SA, Koenig AL, Krone MW, Albanese KI, He CQ, Lee GY, Houk KN, Waters ML, Brustad EM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17253–17256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Pieters BJGE, Wuts MHM, Poater J, Kumar K, White PB, Kamps JJAG, Sherman W, Pruijn GJM, Paton RS, Beuming T, Bickelhaupt FM, Mecinović J, Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Krone MW, Albanese KI, Leighton GO, He CQ, Lee GY, Garcia-Borràs M, Guseman AJ, Williams DC, Houk KN, Brustad EM, Waters ML, Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 3495–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jacobs SA, Khorasanizadeh S, Science (80-. ). 2002, 295, 2080–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Nielsen PR, Nietlispach D, Mott HR, Callaghan J, Bannister A, Kouzarides T, Murzin AG, Murzina NV, Laue ED, Nature 2002, 416, 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Flanagan JF, Mi LZ, Chruszcz M, Cymborowski M, Clines KL, Kim Y, Minor W, Rastinejad F, Khorasanizadeh S, Nature 2005, 438, 1181–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li H, Ilin S, Wang W, Duncan EM, Wysocka J, Allis CD, Patel DJ, Nature 2006, 442, 91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Botuyan MV, Lee J, Ward IM, Kim JE, Thompson JR, Chen J, Mer G, Cell 2006, 127, 1361–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Li H, Fischle W, Wang W, Duncan EM, Liang L, Murakami-Ishibe S, Allis CD, Patel DJ, Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 677–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Collins RE, Northrop JP, Horton JR, Lee DY, Zhang X, Stallcup MR, Cheng X, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Schalch T, Job G, Noffsinger VJ, Shanker S, Kuscu C, Joshua-Tor L, Partridge JF, Mol. Cell 2009, 34, 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kaustov L, Ouyang H, Amaya M, Lemak A, Nady N, Duan S, Wasney GA, Li Z, Vedadi M, Schapira M, Min J, Arrowsmith CH, J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Iwase S, Xiang B, Ghosh S, Ren T, Lewis PW, Cochrane JC, Allis CD, Picketts DJ, Patel DJ, Li H, Shi Y, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 769–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Du J, Zhong X, Bernatavichute YV, Stroud H, Feng S, Caro E, Vashisht AA, Terragni J, Chin HG, Tu A, Hetzel J, Wohlschlegel JA, Pradhan S, Patel DJ, Jacobsen SE, Cell 2012, 151, 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kuo AJ, Song J, Cheung P, Ishibe-Murakami S, Yamazoe S, Chen JK, Patel DJ, Gozani O, Nature 2012, 484, 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cui G, Park S, Badeaux AI, Kim D, Lee J, Thompson JR, Yan F, Kaneko S, Yuan Z, Botuyan MV, Bedford MT, Cheng JQ, Mer G, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 916 EP –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Simhadri C, Daze KD, Douglas SF, Quon TTH, Dev A, Gignac MC, Peng F, Heller M, Boulanger MJ, Wulff JE, Hof F, J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2874–2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Metzger E, Willmann D, McMillan J, Forne I, Metzger P, Gerhardt S, Petroll K, Von Maessenhausen A, Urban S, Schott AK, Espejo A, Eberlin A, Wohlwend D, Schüle KM, Schleicher M, Perner S, Bedford MT, Jung M, Dengjel J, Flaig R, Imhof A, Einsle O, Schüle R, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 132 EP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Local A, Huang H, Albuquerque CP, Singh N, Lee AY, Wang W, Wang C, Hsia JE, Shiau AK, Ge K, Corbett KD, Wang D, Zhou H, Ren B, Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Cordier F, Barfield M, Grzeseik S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15750–15751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ratajczyk T, Czerski I, Kamienska-Trela K, Szymanski S, Wojcik J, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1230–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Horowitz S, Yesselman JD, Al-Hashimi HM, Trievel RC, J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 18658–18663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rahman S, Wineman-Fisher V, Al-Hamdani Y, Tkatchenko A, Varma S, J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lide DR, Taylor & Francis; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rossi M, Tkatchenko A, Rempe SB, Varma S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 12978–12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Huheey JE, J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 3284–3291. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rypniewski WR, Holden HM, Rayment I, Biochemistry 1993, 32, 9851–9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Rayment I, Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press, 1997, Vol. 276; pp 171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Walter TS, Meier C, Assenberg R, Au KF, Ren J, Verma A, Nettleship JEE, Owens RJ, Stuart DII, Grimes JM, Structure 2006, 14, 1617–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bradbury JH, Brown LR, Eur. J. Biochem. 1973, 40, 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Larda ST, Bokoch MP, Evanics F, Prosser RS, Biomol J. NMR 2012, 54, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wiesner S, Sprangers R, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015, 35, 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bokoch MP, Zou Y, Rasmussen SGF, Liu CW, Nygaard R, Rosenbaum DM, Fung JJ, Choi HJ, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Puglisi JD, Weis WI, Pardo L, Prosser RS, Mueller L, Kobilka BK, Nature 2010, 463, 108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ma JC, Dougherty DA, Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1303–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rapp C, Goldberger E, Tishbi N, Kirshenbaum R, Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2014, 82, 1494–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lin FY, Lopes PEM, Harder E, Roux B, Mackerell AD, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 993–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Brady PN, Macnaughtan MA, Anal. Biochem. 2015, 491, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Patel DJ, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a018754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Møller C, Plesset MS, Phys. Rev. 1934, 46, 618–622. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bader R, Oxford University Press; 1995; Vol. 36; pp 354–360. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Sanville E, Kenny SD, Smith R, Henkelman G, J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Varma S, Rempe SB, Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 3394–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 1025–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Beaver JE, Waters ML, ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kobayashi M, Kubota M, Matsuura Y, J. Appl. Glycosci. 2003, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Skegro D, Stutz C, Ollier R, Svensson E, Wassmann P, Bourquin F, Monney T, Gn S, Blein S, J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9745–9759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Busby JN, Panjikar S, Landsberg MJ, Hurst MRH, Lott JS, Nature 2013, 501, 547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Mashtalir N, D’Avino AR, Michel BC, Luo J, Pan J, Otto JE, Zullow HJ, McKenzie ZM, Kubiak RL, St. Pierre R, Valencia AM, Poynter SJ, Cassel SH, Ranish JA, Kadoch C, Cell 2018, 175, 1272–1288.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Daze KD, Hof F, Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR, Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Ringel AE, Cieniewicz AM, Taverna SD, Wolberger C, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, E5461–E5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Cornett EM, Ferry L, Defossez PA, Rothbart SB, Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Sikorsky T, Hobor F, Krizanova E, Pasulka J, Kubicek K, Stefl R, Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11748–11755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Uhlenheuer DA, Petkau K, Brunsveld L, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2817–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Mullins AG, Pinkin NK, Hardin JA, Waters ML, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5282–5285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 724–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Kaniskan HÜ, Martini ML, Jin J, Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 989–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Karton A, Martin JML, Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 115, 330. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Helgaker T, Klopper W, Koch H, Noga J, J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 106, 9639. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Nagy PR, Kállay M, J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 214106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Nagy PR, Samu G, Kállay M, Chem J. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Kállay M, Nagy PR, Mester D, Rolik Z, Samu G, Csontos J, Csóka J, Szabó PB, Gyevi-Nagy L, Hégely B, Ladjánszki I, Szegedy L, Ladóczki B, Petrov K, Farkas M, Mezei PD, Ganyecz Á, J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 074107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Mrcc, a quantum chemical program suite written by Kállay M, Nagy PR, Rolik Z, Mester D, Samu G, Csontos J, Csóka J, Szabó PB, Gyevi-Nagy L, Ladjánszki I, Szegedy, Ladóczki B, Petrov K, Farkas M, Mezei PD, and Hégely B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Nagy PR, Kállay M, Chem J. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M, Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Ernzerhof M, Scuseria GE, J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 5029–5036. [Google Scholar]

- (78).Adamo C, Barone V, J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar]

- (79).Tkatchenko A, Scheffler M, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 073005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Blum V, Gehrke R, Hanke F, Havu P, Havu V, Ren X, Reuter K, Scheffler M, Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009, 180, 2175–2196. [Google Scholar]

- (81).Wineman-Fisher V, Al-Hamdani Y, Addou I, Tkatchenko A, Varma S, Chem J. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 2444–2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Wineman-Fisher V, Al-Hamdani Y, Nagy PR, Tkatchenko A, Varma S, J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 094115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Wineman-Fisher V, Delgado JM, Nagy PR, Jakobsson E, Pandit SA, Varma S, J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 104113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, V Ortiz J, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ, Gaussian 09 Revision A. 1. 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.