SUMMARY

Primary tumors are drivers of pre-metastatic niche formation, but the coordination by the secondary organ toward metastatic dissemination is underappreciated. Here, by single-cell RNA-sequencing and immunofluorescence, we identified a population of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2)-expressing adventitial fibroblasts that remodeled the lung immune microenvironment. At steady-state, fibroblasts in the lungs produced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which drove dysfunctional dendritic cells (DCs) and suppressive monocytes. This lung-intrinsic stromal program was propagated by tumor-associated inflammation, particularly the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β, supporting a pre-metastatic niche. Genetic ablation of Ptgs2 (encoding COX-2) in fibroblasts was sufficient to reverse the immune-suppressive phenotypes of lung-resident myeloid cells, resulting in heightened immune activation and diminished lung metastasis in multiple breast cancer models. Moreover, the anti-metastatic activities of DC-based vaccine and PD-1 blockade were improved by fibroblast-specific Ptgs2 deletion or dual inhibition of PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4. Collectively, lung-resident fibroblasts reshape the local immune landscape to facilitate breast cancer metastasis.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Solid cancer metastasis, which remains the major cause of cancer-related death, is a complex process consisting of a series of steps from primary tumor invasion and intravasation, to tumor cell survival in the circulation, to extravasation and distant organ colonization (Lambert et al., 2017). Among these steps, organ colonization is regarded as a rate-limiting step for metastasis due to robust tissue defenses against disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) (Massague and Obenauf, 2016). Successful colonization is only achieved when organ environments coordinate with newly arrived DTCs to engage immune-inhibitory machinery that surpasses the organ’s defensive barriers. A deep understanding of the mechanisms within the organ environment that regulate DTC rejection or acceptance is essential for uncovering the fundamental biology of metastasis and for developing therapeutics against metastasis.

Organ environments and cancer genomic heterogeneity are two primary determinants of metastatic organotropism, a key characteristic of metastasis denoting that the spread of cancer occurs in a non-random manner with certain tumor types inclined to metastasize to specific organs (Gao et al., 2019). Relative to our increasing knowledge of the cancer-intrinsic genes mediating cancer cells’ organotropic metastases, characterization of the metastasis-supporting organ microenvironments, especially the stroma, is lacking. Many fundamental questions remain unanswered, including whether the susceptibility of organs to tumor metastasis is intrinsic to the organ or induced by primary tumors or involves an interplay of both, and what are the key organ-resident components dictating successful DTC colonization. Answering these questions will help unveil the basis of metastatic organotropism and accelerate design of organ-specific targeting strategies in the clinical management of metastases.

The lung is one of the most common sites of metastasis, frequently colonized in various late-stage solid cancers. Formation of the lung pre-metastatic niche, which is initiated by factors secreted from primary tumors, is a key preparation stage prior to the arrival of DTCs (Liu and Cao, 2016; Peinado et al., 2017). Bone marrow (BM)-derived immunosuppressive myeloid cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, are well-characterized components of the pre-metastatic niche (Kaplan et al., 2005; Kitamura et al., 2015). These myeloid cells facilitate building a hospitable environment for future invading DTCs mainly through their suppression of local anti-tumor immunity, as well as their extravasation-promoting and trophic effects on DTCs (Altorki et al., 2019; Kitamura et al., 2015; Spiegel et al., 2016).

In contrast to the known roles of BM-derived myeloid cells, how the lung-resident stromal fibroblasts, which play decisive roles in a variety of lung diseases (Samarelli et al., 2021; Ushakumary et al., 2021), contribute to formation of the pre-metastatic and metastatic niches is less understood. Here, using single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) and immunofluorescence-based spatial profiling, we identified a metastasis-promoting lung adventitial fibroblast population that constitutively expressed high levels of inflammatory genes, including Ptgs2, Cxcl1, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Il6. These Ptgs2hi fibroblasts reprogrammed various types of myeloid cells to be dysfunctional or immunosuppressive. In mouse models of breast cancer, tumor-associated inflammation enhanced this fibroblast-intrinsic modulation of myeloid cells. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the lung fibroblast signaling pathway involving prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) largely restored lung-resident anti-tumor immunity, reduced lung metastasis of breast cancer, and increased the efficacy of immunotherapeutics in treating lung metastasis. Collectively, our work defines a function for lung-resident stromal cells in eliciting a robust immunosuppressive niche. Targeting lung stromal factors could be an effective strategy to treat lung metastases.

Results

Lung fibroblasts endow myeloid cells with a dysfunctional or immunosuppressive phenotype via expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2)

Formation of an immune dysfunctional lung pre-metastatic niche, which is elicited by primary tumor progression, is critical for early-arrived DTCs to escape anti-tumor immunity (Liu and Cao, 2016; Peinado et al., 2017). In a mouse model of orthotopic breast cancer (4T1) (Figure S1A), we indeed found that lung-resident CD24+CD11c+MHC-II+ dendritic cells (DCs) (Headley et al., 2016; Misharin et al., 2013) (Figure S1B), the antigen presenting cells (APCs) triggering anti-tumor adaptive immunity (Vermaelen and Pauwels, 2005), had reduced capacity to stimulate T cell proliferation at the pre-metastatic stage (Figure S1C). To evaluate how the pre-metastatic lung environment modulates DCs and possibly other APCs, we employed an exogenous myeloid cell transplantation system using bone marrow-derived DCs (BM-DCs), which comprise conventional DCs and other antigen presenting myeloid cells (Helft et al., 2015; Lutz et al., 2017). Upon intravenous (IV) injection of fluorescently labeled healthy BM-DCs into naïve and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (pre-metastatic stage), we monitored the implanted cells in lungs and other organs and tissues for their expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II, the primary molecules on DCs that mediate antigen presentation to T cells (Wculek et al., 2020). Exogenous BM-DCs engrafted in lungs had the lowest levels of MHC-I and MHC-II expression compared to those in other organs and tissues examined, including peripheral blood (PB), BM, spleen and liver (Figure 1A). This occurred in both naïve and tumor-bearing mouse recipients (Figure 1A), suggesting that the lung stroma at a steady state has an intrinsic capacity to disable BM-DCs, and that this effect is further reinforced by tumor-bearing conditions.

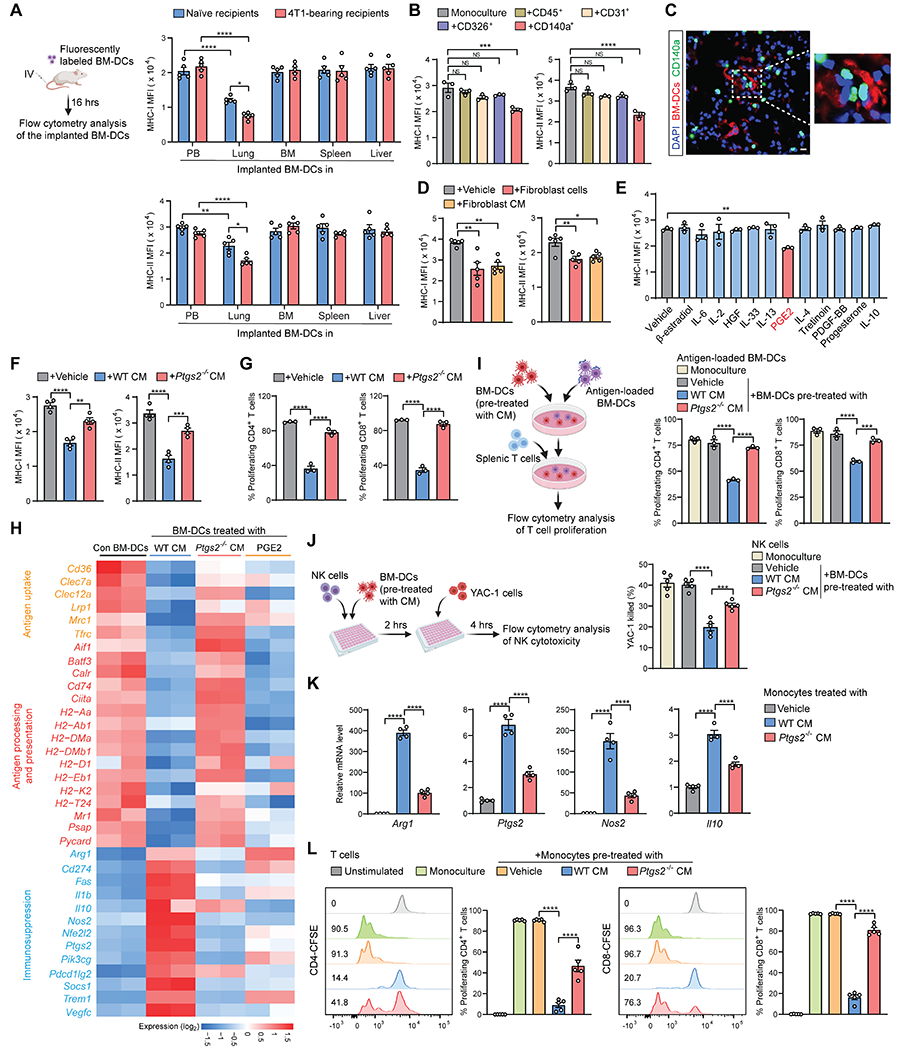

Figure 1. Lung fibroblasts reprogram BM-DCs and monocytes to be dysfunctional or immunosuppressive via COX-2.

(A) MHC-I and MHC-II expression of implanted BM-DCs in different tissues and organs was measured after transfer into naïve or 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (n=5). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

(B) MHC-I and MHC-II expression of BM-DCs was measured after monoculture or co-culture with the indicated lung tissue cells isolated from naïve mice (n=3).

(C) Localization of implanted BM-DCs and resident CD140a+ fibroblasts in lung section of naïve CD140aEGFP mouse. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) MHC-I and MHC-II expression of BM-DCs was measured after co-culture with CD140a+ lung fibroblasts or fibroblast-derived CM (n=5).

(E) MHC-II expression of BM-DCs was measured after stimulation with the indicated factors (n=3).

(F and G) MHC-I and MHC-II expression (F) and T cell priming capacities (G) of BM-DCs were measured after stimulation with WT or Ptgs2−/− lung fibroblast CM (n=3-4).

(H) Heatmap showing the expression of selected genes from the RNA-seq data of BM-DCs.

(I-J) Effect of BM-DCs on proliferation of T cells (I) or cytotoxicity of NK cells (J) was analyzed after stimulation with WT or Ptgs2−/− lung fibroblast CM (n=3-5).

(K-L) Expression of indicated genes (K) and effect on T cell proliferation (L) of BM-derived monocytes was measured after stimulation with WT or Ptgs2−/− lung fibroblast CM (n=4-5).

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least five independent experiments (A-G, I-L) and shown as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; ****p< 0.0001; NS, not significant, by one-way ANOVA (B, D-G, I-L) or two-way ANOVA (A). See also Figure S1.

Using ex vivo co-culture of BM-DCs with various types of lung tissue cells, including CD45+ leukocytes, CD31+ endothelial cells, CD326+ epithelial cells and CD140a (PDGFRα)+ fibroblasts, we identified CD140a+ fibroblasts as being able to inhibit MHC-I and MHC-II expression (Figure 1B) and antigen uptake ability of BM-DCs (Figure S1D). Supporting this, a close proximity of implanted BM-DCs to CD140a+ cells within the lung interstitium was detected in vivo (Figure 1C). Despite this, direct cell-cell contact was not necessary for lung fibroblasts to modulate BM-DCs, as lung fibroblast-conditioned medium (CM) was as effective as lung fibroblast cells in modulating BM-DCs (Figures 1D and S1E). These results suggested that DC dysfunction is elicited by lung-resident fibroblasts via soluble factors.

To identify the lung fibroblast-derived soluble factor(s), we leveraged the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from BM-DCs without and with treatment by lung fibroblast CM. By Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, we obtained the top upstream regulator candidates (Figure S1F) that may stimulate changes in BM-DCs. With MHC-II expression as a DC functional indicator, PGE2 was screened as the most effective factor in repressing MHC-II expression on BM-DCs (Figure 1E). PGE2, a prostaglandin playing multifaceted roles in inflammation and cancer, is generated from arachidonic acid via the actions of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, COX-1 and COX-2 (Nakanishi and Rosenberg, 2013). As expected, lung fibroblasts isolated from naïve mice secreted PGE2 (Figure S1G). At the transcriptional level, lung fibroblasts expressed a higher level of Ptgs2 (encoding COX-2) than Ptgs1 (encoding COX-1) (Figure S1H). Furthermore, PGE2 in lung fibroblasts was almost exclusively contributed by COX-2, with no apparent compensatory activity from COX-1, as lung fibroblasts isolated from Ptgs2 knockout (KO) mice showed minimal PGE2 production (Figure S1I). In the ex vivo co-culture system, Ptgs2 ablation in lung fibroblasts largely abrogated their regulatory effects on BM-DCs (Figures 1F and S1J). Consequently, the antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell hyporesponsiveness induced by lung fibroblast-exposed BM-DCs was substantially reversed by Ptgs2 deficiency in fibroblasts (Figure 1G). Therefore, COX-2-PGE2 is essential for lung fibroblasts to endow BM-DCs with a dysfunctional phenotype.

By further probing the transcriptomic profiles of BM-DCs, we found that lung fibroblasts, in a COX-2-dependent manner, inhibited the expression of genes associated with antigen uptake, processing, and presentation in BM-DCs, and purified PGE2 acted similarly to lung fibroblasts (Figure 1H). In addition, the expression levels of multiple immunosuppression-associated genes, including Arg1, Cd274, Il10, Nos2, Ptgs2, and Pdcd1lg2, were increased in BM-DCs upon stimulation by wild type (WT) lung fibroblasts (Figure 1H). Further analysis of the BM-DC transcriptomes precluded the possibility of lung fibroblast-mediated DC differentiation into macrophages (Figure S1K), which can be immunosuppressive (Pathria et al., 2019). Induction of these immunosuppression-associated genes in BM-DCs was primarily dependent on lung fibroblast-derived COX-2, but to a lesser extent on PGE2, as Ptgs2-KO in lung fibroblasts reversed the effect on most of these genes, while PGE2 alone only activated a subset (Figure 1H). We reasoned that COX-2-derived other prostaglandins than PGE2 (Funk, 2001) in lung fibroblasts may be involved in this immunosuppression-associated gene induction in BM-DCs. As a functional consequence, lung fibroblast CM-educated BM-DCs served to suppress antigen-specific T cell proliferation (Figure 1I) and the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells (Figure 1J), which are pivotal to restraining DTCs at the early colonization stage (Li et al., 2020b; Lopez-Soto et al., 2017). Again, these effects were dependent on lung fibroblast-derived COX-2 (Figures 1I and 1J). Therefore, via COX-2-PGE2 and possibly other COX-2-derived prostaglandins, lung fibroblasts endow exogenous BM-DCs with dysfunctional and immunosuppressive capacities.

Next, we asked whether this stromal-myeloid cell interaction also occurs in other myeloid lineage cells. Monocytic cells play crucial roles in a diversity of lung diseases and metastasis (Baharom et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2011), and we therefore determined whether monocytic cells are altered by lung fibroblasts. Upon stimulation with lung fibroblast CM, BM-derived monocytes (Figure S1L) increased their expression of a series of immunosuppressive genes, including Arg1, Ptgs2, Nos2 and Il10, which was partially dependent on lung fibroblast-derived COX-2 (Figure 1K). Correspondingly, lung fibroblast-educated monocytes suppressed T cell proliferation (Figure 1L) and NK cell cytotoxicity (Figure S1M), in a lung fibroblast COX-2-dependent manner. In accordance with these ex vivo results, monocytes showed a tissue-specific gene expression pattern in vivo, with higher expression of immunosuppressive genes in lung-infiltrating monocytes than those isolated from BM or PB, which was more prominent under tumor-bearing conditions (Figure S1N). Taken together, lung fibroblasts, via expression of COX-2, reprogram various myeloid cell types to be dysfunctional or immunosuppressive.

Ptgs2-expressing lung fibroblasts modulate the lung-resident immune microenvironment at the steady state

To determine whether the COX-2-dependent stromal-immune interaction is specific to the lung, we employed Ptgs2Luc reporter mice (Ishikawa et al., 2006) to compare COX-2 signals in different organs isolated from naïve mice. Compared to other organs tested, including brain, bone (femur and tibia), intestine, stomach, heart, liver, spleen, pancreas and kidney, the lungs expressed a higher level of Ptgs2 (Figures 2A and S2A). In human, a similarly high PTGS2 expression in lungs was detected (Figure 2B) through analyses of human tissue microarray data (Rhodes et al., 2004). The characteristically high levels of Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 production in the lung were mainly contributed by lung fibroblasts, shown by comparison of the major types of lung cells isolated from naïve mice (Figure 2C). Further, lung fibroblasts were superior to fibroblasts isolated from other tested tissues (bone, heart, liver, spleen and mammary glands) in their Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 secretion (Figure 2D) and endowed myeloid cells (monocytes) with a more potent immunosuppressive phenotype (Figure S2B). Thus, the lung is a unique organ with constitutively high Ptgs2 (or PTGSE2) expression, predominantly in resident fibroblasts.

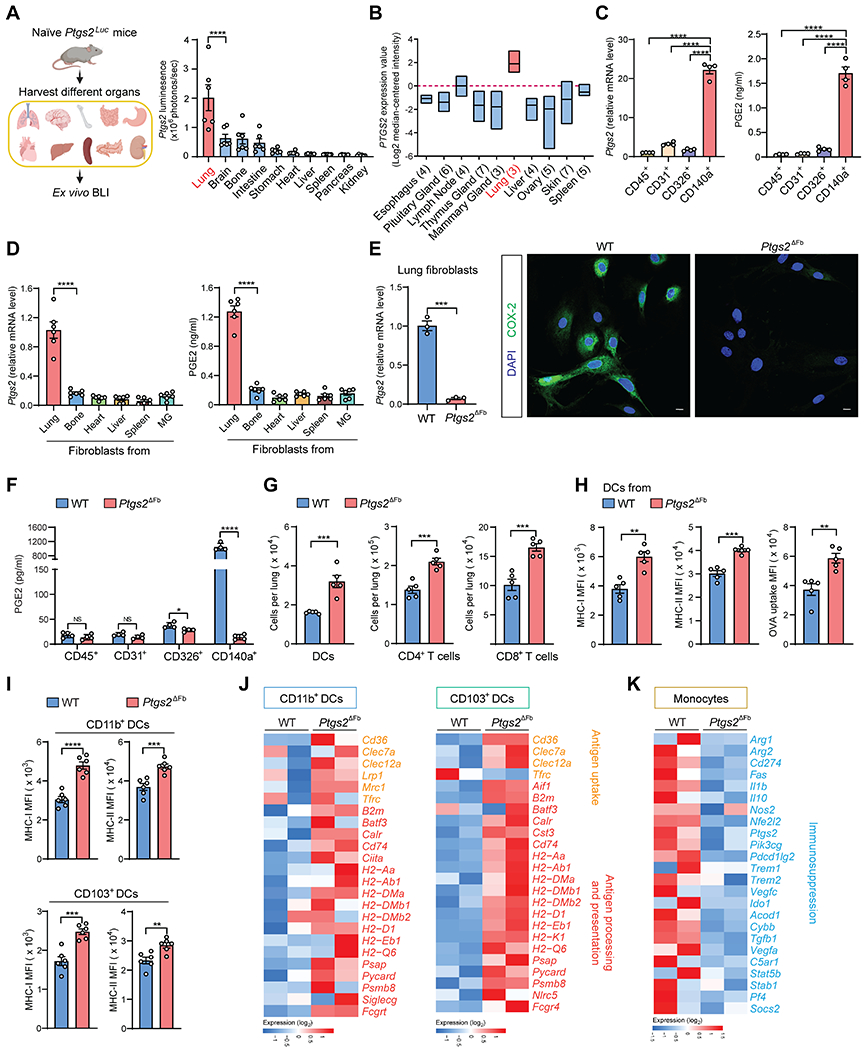

Figure 2. Ptgs2-expressing lung fibroblasts modulate the lung resident immune microenvironment at the steady state.

(A) Quantification of Ptgs2 expression in different organs isolated from naïve Ptgs2Luc mice (n=6).

(B) Analysis of PTGS2 expression in human normal tissue microarray data (GSE7307).

(C-D) Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 production was measured in the indicated lung tissue cells (C) or different tissue-derived fibroblasts (D) isolated from naïve mice (n=4-6). MG, mammary gland.

(E) Ptgs2 expression (left) and COX-2 protein level (right) was detected in lung CD140a+ fibroblasts from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice. Scale bars, 10 μm.

(F-G) PGE2 production of indicated lung tissue cells (F) and the total number of lung DCs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (G) was measured in WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice (n=4-5).

(H) MHC-I and MHC-II expression and OVA uptake ability was determined in lung DCs from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice (n=5).

(I) MHC-I and MHC-II expression was determined in lung CD11b+ and CD103+ DCs from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice (n=6).

(J and K) Heatmap showing expression of indicated genes from the RNA-seq data of lung CD11b+ or CD103+ DCs (J) and conventional monocytes (K) from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice.

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least three (A, D, I) or five (C, E-H) independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; ****p< 0.0001; NS, not significant, by one-way ANOVA (A, C-D) or unpaired Student’s t-test (E-I). See also Figure S2.

To better understand the role of the COX-2-dependent lung fibroblast program in reprogramming the lung-resident immune microenvironment, we generated fibroblast-targeted Ptgs2 conditional KO (cKO) mice (Ptgs2ΔFb). With Ptgs2 deficiency, lung fibroblasts lost COX-2 expression and PGE2 production (Figures 2E and 2F). Upon profiling the lung immune microenvironment (Figures S1B and S2C) of naïve WT and Ptgs2ΔFb mice, we found that the total numbers of adaptive immunity-related cells, including DCs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, were increased in Ptgs2ΔFb mice (Figure 2G). In contrast, the frequencies of lung myeloid cells (alveolar macrophages, neutrophils and conventional monocytes) were comparable between cKO and WT mice, except for an increase in non-alveolar macrophages in cKO mice (Figure S2D).

Aside from these cell frequency changes, ablation of fibroblast Ptgs2 led to increased expression of MHC-I and MHC-II on lung-resident DCs, along with their increased capacity to take up antigens (Figure 2H). Further characterization of the two primary types of lung-resident DCs, CD103+ and CD11b+ DCs (Desch et al., 2013; Neyt and Lambrecht, 2013), showed that fibroblast-COX-2-mediated MHC-I and MHC-II suppression occurred similarly in both DC subtypes (Figure 2I). Beyond MHC molecules, a broad spectrum of genes associated with antigen uptake, processing and presentation were increased in both CD11b+ and CD103+ lung-resident DCs isolated from Ptgs2ΔFb mice, compared to those from WT mice (Figures 2J and S2E). Such COX-2 loss-induced lung-resident DC changes were reversed by injection of PGE2 into Ptgs2ΔFb mice, confirming the role of COX-2-PGE2 signaling in modulation of lung-resident DCs in vivo (Figure S2F).

As for the lung-infiltrating conventional monocytes, their expression of a series of immunosuppressive genes, including Arg1, Arg2, Cd274, Ptgs2, Nos2 and Il10, was reduced by Ptgs2 cKO (Figures 2K and S2G). In contrast to the above transcriptional changes in myeloid cells, expression of genes encoding essential mediators of anti-tumor immunity, including T cell cytokines interferon γ (IFNγ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin 12 (IL-12), cytotoxic protein perforin-1, chemokines C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9 and CXCL10, and transcriptional factors signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and eomesodermin (EOMES) (Vesely et al., 2011), were elevated in CD45+ immune cells isolated from Ptgs2ΔFb mouse lungs compared to WT mice (Figure S2H). In accordance with the results from bulk RNA-seq and quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Table S1), lung immune profiling by scRNA-seq showed similar changes induced in lung-resident DCs and monocytes by Ptgs2 cKO (Figures S2I–S2L). Collectively, loss of COX-2 in CD140a+ fibroblasts led to quantitative and qualitative reprogramming of the lung immune microenvironment characterized by diminished immune dysfunction and immunosuppression, together with augmented anti-tumor adaptive immunity.

Identification of the Ptgs2-expressing fibroblasts by scRNA-seq

To identify the specific lung fibroblast subset expressing Ptgs2, we performed scRNA-seq on sorted CD45−CD31−CD326− cells, which include CD140a+ fibroblasts and other stromal cells. Unbiased clustering through Seurat identified 15 clusters. Upon removal of the contaminating cells, five major stromal cell types were classified, including CD140a+ fibroblasts, mesothelial cells, pericytes, smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts, based on their specific marker gene expression (Habermann et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2018; Zepp et al., 2017) (Figures S3A). Among the five types of stromal cells, Ptgs2 was predominantly expressed in CD140a+ fibroblast clusters, and was particularly highly enriched in cluster 1 (Figures S3B and S3C), which accounted for ~25% of all CD140a+ fibroblasts (Figures S3B and S3D).

Analysis of other signature genes of the Ptgs2hi fibroblast cluster (cluster 1) revealed Has1 as the most prominent (Figure S3C). Has1 encodes hyaluronan synthase 1 (HAS1), which can be induced in mesenchymal lineage cells in response to inflammatory stimuli, including PGE2, and serves as a mediator of inflammation (Siiskonen et al., 2015). In a work studying human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a unique human HAS1hi extracellular matrix (ECM)-producing lung stromal population was characterized (Habermann et al., 2020). We thus speculated that these HAS1hi human stromal cells correspond to Ptgs2hi fibroblasts in mice. Through analysis of human lung scRNA-seq data (Habermann et al., 2020) (Figure S3E), the PTGS2-expressing human lung stromal cells fell into the PDGFRA+ HAS1+ cluster (Figure S3F). Thus, scRNA-seq analyses identified a unique lung Ptgs2hi CD140a+ fibroblast population in mouse and human.

As the Ptgs2hi cells were exclusively CD140a+ fibroblasts, we next purified CD140a+ lung cells using CD140aEGFP mice for higher-resolution scRNA-seq (Figure 3A). Within the CD140a+ lung fibroblasts, 6 distinct clusters were revealed by unbiased clustering analysis and, among them, cluster 0 was identified as the Ptgs2hi fibroblasts (Figure 3B). Other genes encoding the key enzymes of the PGE2 synthesis pathway were not co-clustered with Ptgs2 (Figure 3C). The top 10 enriched genes in this Ptgs2hi lung fibroblast subset were, without exception, inflammation-associated genes. In addition to Ptgs2 and Has1, signature genes include Cxcl1 (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1), Il6 (interleukin 6), Tnfaip6 (TNF alpha induced protein 6), Mt1 (metallothionein-1), Zfp36 (zinc finger protein 36 homolog), Ccl7 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 7), Ptx3 (pentraxin 3) and Ccl2 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 2) (Figure 3D). All of them play crucial roles in different stages of inflammation and are inducible by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) (Doni et al., 2019; King et al., 2009; Mackay, 2001; Mittal et al., 2016; Samad et al., 2001; Sanduja et al., 2012; Siiskonen et al., 2015; Subramanian Vignesh and Deepe, 2017; Tanaka et al., 2014). The expression of other canonical inflammatory genes appeared independent of Ptgs2, as the transcriptional levels of the majority of them remained unaltered upon Ptgs2 deletion in CD140a+ fibroblasts (Figure 3E). Based on the gene expression profile, we surmised that the Ptgs2hi fibroblast subset is a pro-inflammatory signal-responsive lung stromal element that modulates local immune responses.

Figure 3. Identification of Ptgs2-expressing fibroblasts by scRNA-seq.

(A) Workflow depicts isolation of CD140a+ lung fibroblasts from naïve CD140aEGFP mice for scRNA-seq.

(B) t-SNE plots (left) and feature plots (right) showing the Ptgs2hi fibroblasts (cluster 0) among lung CD140a+ fibroblasts.

(C) Schematic showing the PGE2 synthesis pathway (left), and violin plots (right) showing the expression levels of the indicated genes across each cluster.

(D) Heatmap showing the expression of the top-rated marker genes across each cluster.

(E) mRNA expression of the indicated genes was measured in lung fibroblasts isolated from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb naïve mice (n=6).

(F) Enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology terms in Ptgs2hi fibroblasts (cluster 0).

(G) Heatmap showing transcription factor activity analysis of the three major fibroblast subsets (clusters 0, 1 and 2).

(H) Heatmap showing co-expression analysis of human genes co-expressed with PTGS2 from human normal tissue microarray data (GSE3526). LN, lymph node.

(I) Dot plots showing expression of the selected genes across each cluster.

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (E). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ****p< 0.0001; NS, not significant, by unpaired Student’s t-test (E). See also Figure S3.

In line with the inflammatory gene expression, a series of inflammation-related pathways were enriched in the Ptgs2hi lung fibroblast subset, such as “Inflammatory response” and “Cellular response to interleukin-1” (Figure 3F). Analysis of the transcription factor (TF) activities indicated that, compared to two other major fibroblast subsets (clusters 1 and 2, Figure 3B), the Ptgs2hi fibroblasts possess more robust activities of TFs associated with inflammation, such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), nuclear factor kappa b subunit 1 (NFKB1), and cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 (CREB1) (Taniguchi and Karin, 2018; Wen et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2009) (Figure 3G). By analyzing human normal tissue transcriptome data (Roth et al., 2006), a large proportion of the mouse Ptgs2hi fibroblast signature genes were found within the top listed genes co-expressed with PTGS2, including IL6, CCL2, CXCL1, PTX3 and TNFAIP6, in the human lung, but not other human tissues and organs examined (Figure 3H). This co-expression profile was similarly detected in mice upon analysis of the scRNA-seq data from CD140a+ fibroblasts (Figure 3I). Collectively, these data suggested that the Ptgs2hi lung fibroblast subset is an intrinsic stromal component that maintains an inflammation-prone immunoregulatory milieu in the lung at the steady state.

Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts are mainly located within the lung adventitial space

Given that Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts could be an inflammation-regulatory stromal population, we wondered how this subset of stromal cells spatially interacts with resident inflammatory cells of the lung. To this end, we leveraged published scRNA-seq datasets with available information on gene expression profiles associated with anatomical locations in mouse and human lungs (Travaglini et al., 2020). By mapping reported signature genes of eight anatomically annotated mouse lung stromal subsets onto our scRNA-seq data (Figure S3A), we found that naïve mouse lung CD140a+ fibroblasts mainly comprise three known stromal subsets -- adventitial fibroblasts (AdvF), alveolar fibroblasts (AlvF) and lipofibroblasts (LipF) (Figure 4A). In particular, the Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts (cluster 1, Figure 4A) were characterized as a subpopulation of the Serpinf1- and Pi16-expressing AdvFs (Figures 4B and 4C), which are fibroblasts localized around arteries, veins, and airways in the lung playing critical roles in pulmonary vascular remodeling and tissue immunity (Dahlgren and Molofsky, 2019; Stenmark et al., 2011). Similar to the mouse findings, PTGS2-expressing human lung stromal cells mostly fell into the AdvF subset (Figure 4D). Therefore, the Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts were categorized as a subpopulation of AdvF.

Figure 4. Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts localize primarily within the lung adventitial space.

(A) t-SNE plots showing lung CD140a+ fibroblasts from the scRNA-seq data in Figure S3A. AdvF, adventitial fibroblast; AlvF, alveolar fibroblast; LipF, lipofibroblast.

(B and C) Violin plots (B) and dot plots (C) showing expression of the indicated genes across each cluster. Gen, general fibroblast; MyoF, myofibroblast; FibM, fibromyocyte; ASM, airway smooth muscle; VSM, vascular smooth muscle; Peri, pericyte.

(D) Violin plots showing expression of the indicated genes in human lung stromal cells from a published dataset (EGAS00001004344). Meso, mesothelial cells.

(E and F) Representative images showing the localization of CD140a-GFP+ COX-2+ cells in naïve mouse lung adventitia or alveolar space (E), and the percentage of COX-2+ cells among CD140a+ fibroblasts was quantified in these two regions (F). For the percentage calculation, two pictures were chosen for each region from each mouse lung section; n = 5 mice per group. Scale bars, 50 μm. aw, airway; bv, blood vessel.

(G-J) Representative images showing the localization of CD140a-GFP+ COX-2+ cells and myeloid cells (G), CD11b+ DCs (H), CD103+ DCs (I), or conventional monocytes (J) in pre-metastatic lung sections of AT3 tumor-bearing mice. Scale bars, 50 μm.

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (E-J). ****p< 0.0001, by unpaired Student’s t-test (F).

Using immunofluorescence, we further pinpointed the spatial localization of Ptgs2hi fibroblasts in the lung, as well as their interactions with myeloid cells. In naïve lungs, we compared the distributions of COX-2+ fibroblasts within the adventitial versus alveolar regions. These cells mainly resided within the lung adventitial space (Figures 4E and 4F), consistent with the scRNA-seq analysis. Moreover, in the pre-metastatic lung, COX-2+ fibroblasts were physically close or adjacent to a diversity of myeloid cells, including CD11b+ DCs, CD103+ DCs and Ly6C+ monocytes (Figures 4G–4J). Based on their expression of myeloid cell chemokines (CXCL1, CCL7 and CCL2), immunomodulators (COX-2 and TNFAIP6), and ECM modulator (HAS1), we speculated that the adventitial location of COX-2+ fibroblasts favors recruitment and reprograming of infiltrated inflammatory cells to form an immunosuppressive pre-metastatic lung niche. Hence, Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts were identified as a subpopulation of AdvF that physically interact with various types of resident myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic lung.

IL-1β reinforces the phenotype of Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts

To define whether tumor-bearing conditions impact the COX-2-dependent lung stromal program, we employed AT3 and AT3-gcsf orthotopic breast tumor models that enabled us to decouple the effects of tumor versus host inflammation. The AT3 line originates from an MMTV-PyMT tumor and induces marginal host inflammation (Stewart and Abrams, 2007), whereas the AT3-gcsf line was constructed to overexpress granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) that stimulates strong host inflammation, specifically neutrophilia (Gong et al., 2022), similar to the 4T1 model used above.

At the pre-metastatic stage of the AT3 and AT3-gcsf orthotopic models (Figure S4A), CD140a+ lung fibroblasts were isolated for comparison of their Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 production. While transcriptional and protein levels of COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in lung fibroblasts were mildly increased by AT3 tumor-bearing, they were all further induced in the AT3-gcsf model (Figures 5A and S4B). In addition, the total number of CD140a+ fibroblasts was increased in AT3-gcsf tumor-bearing mice (Figure S4C). Consistent with COX-2-PGE2 upregulation in lung fibroblasts, elevated host inflammation reinforced myeloid cell reprogramming (MHC-I and MHC-II expression in exogenous BM-DCs) in the pre-metastatic lung in vivo (Figure S4D). Therefore, host inflammation (neutrophilia) served to heighten the COX-2-dependent lung fibroblast program.

Figure 5. IL-1β reinforces the phenotype of Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts.

(A) Ptgs2 expression (left), PGE2 production (middle), and frequency of COX-2+ cells (right) was measured in lung CD140a+ fibroblasts from naïve, AT3 and AT3-gcsf tumor-bearing mice (n=3-6).

(B) Expression of the indicated genes in ex vivo cultured WT and Il1r−/− lung fibroblasts upon stimulation by vehicle or IL-1β (n=3).

(C) COX-2 protein level in ex vivo cultured naïve mouse-derived lung fibroblasts stimulated with vehicle or IL-1β.

(D) Ptgs2 expression (left) and PGE2 production (right) was measured in lung CD140a+ fibroblasts after stimulation with IL-1β in the absence or presence of NFκB pathway inhibitor MLN120B (n=3).

(E and F) Heatmap showing expression of the indicated genes in the RNA-seq data of lung fibroblasts.

(G) Volcano plots showing fold change and P-value for the comparison of IL-1β-treated and vehicle-treated lung fibroblasts based on the RNA-seq data.

(H and I) As depicted in the schematic (H), the frequency of COX-2+ fibroblasts was measured among lung CD140a+ fibroblasts upon treatment by IL-1β (I) (n=7). Negative control IgG is shown.

(J) Cell number (left) and IL-1β production (right) of lung neutrophils was quantified in naïve, AT3 and AT3-gcsf tumor-bearing mice (n=5).

(K) Expression of the indicated genes was measured in lung fibroblasts after co-culture with lung neutrophils isolated from AT3-gcsf tumor-bearing mice in the absence or presence of anti-IL-1β (n=4).

(L) Representative images showing the localization of CD140a-GFP+ COX-2+ cells and neutrophils in pre-metastatic lung sections. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(M) Schematic showing that the immunoregulatory program by Ptgs2hi lung AdvF can be reinforced by IL-1β.

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least five independent experiments (A-D, I-L) and shown as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; ****p< 0.0001; NS, not significant, by one-way ANOVA (A, D, J-K) or unpaired Student’s t-test (B, I). See also Figure S4.

Based on the scRNA-seq result showing “Cellular response to interleukin-1” as one of the top enriched pathways in Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts (Figure 3F), we speculated that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1 could be a relevant host inflammation-associated factor. Indeed, exogenous addition of IL-1β stimulated lung fibroblasts to highly express Ptgs2, as well as Ptgs1 and Ptges, albeit not as strongly (Figure 5B), which was abrogated by IL-1 receptor (Il1r1) deficiency in lung fibroblasts (Figure 5B). This IL-1β-dependent COX-2 regulation in lung fibroblasts was further confirmed at the protein level (Figures 5C and S4E). Pharmacological inhibition of the NFκB pathway mitigated IL-1β-induced Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 production in lung fibroblasts (Figure 5D), confirming a functional role for the high level of NFκB activity detected in Ptgs2hi lung fibroblasts (Figures 3G and S4F). Thus, an IL-1β-IL-1R-NFκB signaling axis was revealed in the regulation of COX-2-PGE2 in lung fibroblasts.

By RNA-seq, IL-1β was found to elicit broad transcriptional changes in lung fibroblasts ex vivo. In addition to prostaglandin synthesis genes (Figure 5E), expression levels of the majority of Ptgs2hi lung fibroblast signature genes, particularly Ptgs2, Il6, Ccl7, Cxcl1 and Ccl2, were elevated in lung fibroblasts after IL-1β stimulation (Figures 5F and 5G). In vivo, IL-1β treatment increased the percentage of COX-2+ lung fibroblasts but not the total number of fibroblasts (Figures 5H, 5I, and S4G), and stimulated expression of Ptgs2hi lung fibroblast signature genes in lung fibroblasts (Figures S4H and S4I). Moreover, host deficiency of Il1r1 led to a reduction in the proportion of COX-2+ lung fibroblasts in vivo under steady-state, suggesting an essential role for endogenous IL-1β-IL-1R signaling in lung fibroblast modulation (Figure S4J). Human lung fibroblast-like cells similarly elevated their expression of Ptgs2hi fibroblast signature genes (PTGS2, IL6, CCL2, CCL7 and CXCL1) and PGE2 production upon IL-1β treatment, partially dependent on NFκB (Figure S4K). Thus, in both mouse and human, IL-1β was revealed to be a key regulator of the lung fibroblast program.

Finally, we determined the cellular source of IL-1β. Similar to our previous finding showing potent expression of Il1b in lung-infiltrating neutrophils in the 4T1 model (Li et al., 2020a), lung neutrophils in the AT3 models released abundant soluble IL-1β (Figure 5J). Ex vivo, lung fibroblast expression of Ptgs2, Il6, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Cxcl1 was exclusively elevated upon co-culture with lung neutrophils isolated from AT3-gcsf tumor-bearing mice. Neutralization of IL-1β partially abolished this effect, indicating the indispensable role of neutrophil-derived IL-1β in neutrophil-lung fibroblast crosstalk (Figure 5K). Corroborating these ex vivo findings, a spatially close interaction was detected between COX-2+ lung fibroblasts and Ly6G+ neutrophils in the pre-metastatic lung (Figure 5L). Taken together, these data support a model whereby the myeloid cell regulatory program intrinsic to Ptgs2hi lung AdvF can be further reinforced by neutrophil-derived IL-1β during progression of tumor-associated inflammation (Figure 5M).

Genetic ablation of Ptgs2 in CD140a+ fibroblasts mitigates lung metastasis

Using the Ptgs2ΔFb model, we next determined the functional contribution of Ptgs2hi lung AdvF in breast cancer lung metastasis. To define their role in the pre-metastatic niche to accommodate DTC colonization, we utilized a modified experimental lung metastasis model, in which luciferase-labeled AT3 (AT3-Luc) cells were IV injected into WT and Ptgs2ΔFb mice bearing orthotopic AT3 tumors (unlabeled) at their pre-metastatic stage. Two weeks later, while the primary tumors did not differ between the two mouse strains, metastatic colonization by AT3-Luc cells in Ptgs2ΔFb mouse lungs was 4-fold lower than in WT mice (Figure 6A). Depletion of DCs (Figure S5A) and possibly other myeloid cells using clodronate liposomes (Perruche et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2016) partially reversed this effect (Figure 6B), indicating that myeloid cells are functionally involved in Ptgs2hi AdvF-mediated modulation of metastasis in vivo. Using a different syngeneic breast tumor line, E0771, this mitigation of metastatic colonization in Ptgs2ΔFb mice was similarly detected (Figures S5B and S5C). These results support a colonization-promoting role of Ptgs2hi lung AdvF.

Figure 6. Genetic ablation of Ptgs2 in CD140a+ fibroblasts mitigates lung metastasis of breast cancer.

(A) As depicted in the schematic (left), lung metastatic colonization in WT or Ptgs2ΔFb recipient mice was measured by ex vivo bioluminescent imaging (BLI). The primary tumor weight was also compared between the two recipient mice (n=9).

(B) As depicted in the schematic (left), lung metastatic colonization was determined in WT or Ptgs2ΔFb mice treated with control or clodronate liposomes (n=9).

(C and D) As depicted in the schematic (left), the percentage of AT3-mCherry cells was measured in WT or Ptgs2ΔFb mice (C) (n=10). Representative images were taken from (C) to show mCherry+ AT3 cells in lung sections (D). Scale bars, 25 μm.

(E) Comparison of spontaneous lung metastases occurring in MMTV-PyMT Ptgs2ΔFb mice and their WT littermates (n=14). Representative histological lung sections stained with H&E are shown and arrowheads indicate metastatic lesions. Scale bars, 1mm.

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments (A-C, E) and shown as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01; NS, not significant, by Mann-Whitney test (A-C, E). See also Figures S5 and S6.

To rule out possible confounding effects of CD140a-lineage hematopoietic cells that however do not express CD140a (Miura et al., 2021) (Figures S6A and S6B), we also generated BM-chimeric mice in which WT hematopoietic cells were engrafted in lethally irradiated WT or Ptgs2ΔFb mice (Figures S6C and S6D). Using this BM-chimeric Ptgs2ΔFb model, we validated that loss of Ptgs2 in CD140a+ fibroblasts led to similar changes in lung-resident immune cells (Figures S6E–K), as detected in the original Ptgs2ΔFb model. Accordingly, targeted deletion of Ptgs2 in fibroblasts in the BM-chimeric model reduced lung colonization by breast tumor cells (Figure S6L).

To better recapitulate human breast cancer patients with metastases, we exploited a spontaneous lung metastasis model in which metastases were assessed 2 weeks after surgical removal of the primary tumors (Figure 6C, left). We observed fewer lung metastases spontaneously occurring in Ptgs2ΔFb mice, compared to WT mice (Figures 6C and 6D). Lastly, we evaluated the impact of fibroblast-specific Ptgs2 deficiency on spontaneous metastases in the genetically engineered MMTV-PyMT model by crossing the Ptgs2ΔFb strain with the MMTV-PyMT strain. Consistent with the transplantation models, deletion of Ptgs2 in CD140a+ fibroblasts reduced spontaneous lung metastases developed in MMTV-PyMT mice (Figure 6E). In sum, the COX-2-PGE2-dependent lung fibroblast program functions to promote breast cancer metastasis to the lung.

Targeting COX-2-PGE2 signals synergizes with immunotherapeutics in controlling lung metastasis

Given the essential role of the COX-2-PGE2 pathway in lung fibroblasts in reprogramming the lung immune microenvironment and facilitating metastatic progression, we endeavored to target this pathway in preclinical models as a strategy to boost local anti-tumor immunity and thereby improve efficacy of clinically used immunotherapeutics such as DC vaccine and immune checkpoint blockade (Palucka and Banchereau, 2013; Sharma and Allison, 2015). When we first tested a selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, it was found ineffective in reducing metastatic colonization in the AT3 model (Figure S7A). As a possible explanation, celecoxib did not reduce PGE2 levels in the lungs of naïve or tumor-bearing mice (Figure S7B). We reasoned that this might be due to a compensatory effect from another COX isoform, COX-1, and therefore we speculated that blockage of PGE2 receptors may represent a more effective approach to repress PGE2 signals in vivo.

In lung-resident DCs and conventional monocytes, EP2 and EP4 were expressed at high levels among the four mouse PGE2 receptors (EP1-EP4) (Figure S7C). While administration of either EP2 or EP4 antagonist was ineffective in reducing AT3 tumor colonization, possibly due to compensatory effects between these two PGE2 receptors, administration of the two antagonists together showed a greater than 10-fold reduction of metastatic colonization in the modified experimental metastasis model (Figure 7A). Consistent with this potent efficacy in treating metastasis, MHC molecule expression and antigen uptake ability of lung DCs, as well as the proportion of lung-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, were all elevated by dual EP2 and EP4 inhibition (Figure S7D). In addition to the AT3 model, the effectiveness of dual EP2/EP4 inhibition in mitigating lung metastasis was further validated in 4T1 and E0771 transplantation models, representative of triple negative and luminal B breast cancer subtypes, respectively (Le Naour et al., 2020; Pulaski and Ostrand-Rosenberg, 2001) (Figures S7E and S7F), as well as in the MMTV-PyMT model (Figures 7B and 7C). Therefore, targeting both EP2 and EP4 was effective to control lung metastasis of breast cancer.

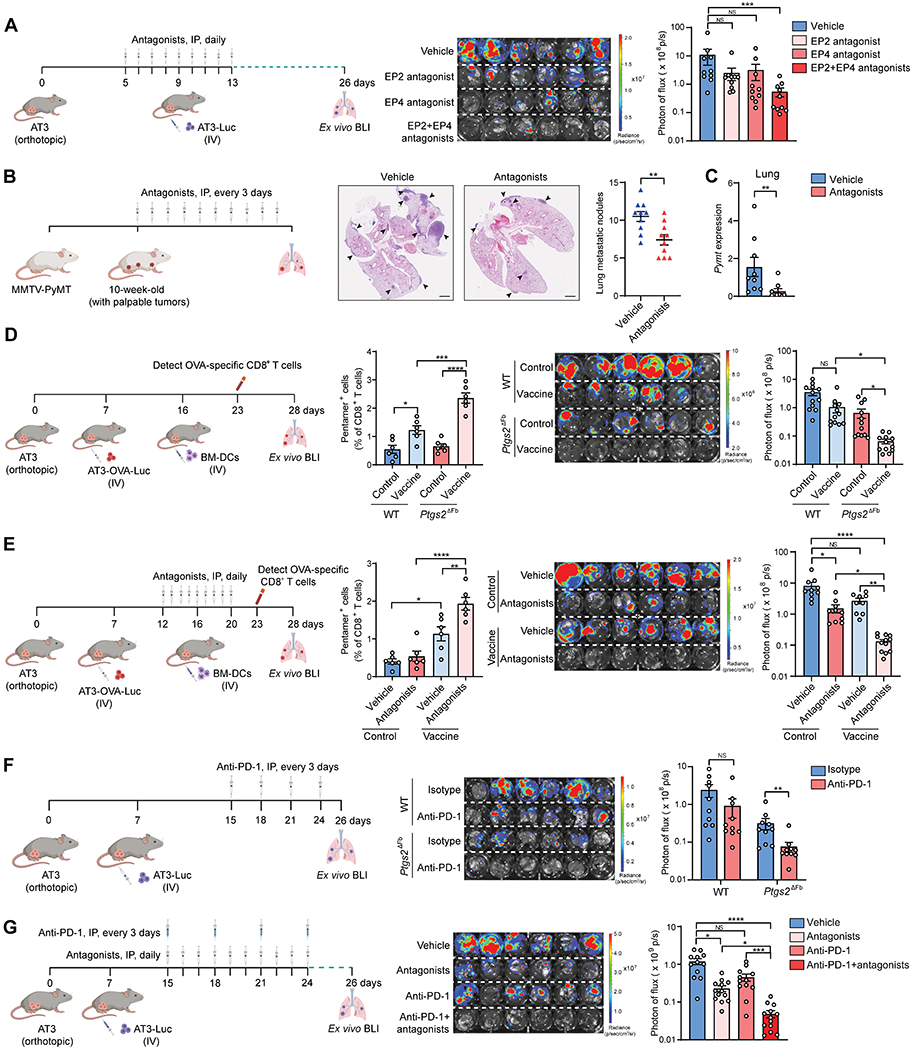

Figure 7. Targeting COX-2-PGE2-EP2/EP4 pathway synergizes with DC vaccine or anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in controlling lung metastasis.

(A) As depicted in the schematic (left), the effect of the single inhibition of EP2 or EP4, or dual inhibition of both receptors, in controlling lung metastatic colonization was determined (n=10).

(B and C) As depicted in the schematic (left), the effect of dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 in controlling spontaneous lung metastases was determined. Representative H&E images of lung sections are shown, and the number of lung metastatic nodules was counted (B) (n=10). Mammary tumor-specific Pymt mRNA level in the lungs was quantified (C) (n=9).

(D and E) As depicted in their respective schematic (left), the combined effect of DC vaccine with host fibroblast Ptgs2 ablation (D) or dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 (E) in treating lung metastatic colonization was determined. The frequency of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood was analyzed (middle) (n=6), and lung metastatic colonization was determined (right) (n=12 for D, and n=9-12 for E).

(F and G) As depicted in their respective schematic (left), the combined effect of anti-PD-1 with host fibroblast Ptgs2 ablation (F) or dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 (G) in treating lung metastatic colonization was determined (right) (n=10 for F, and n=12-13 for G).

n is the number of biological replicates. Data are representative of at least three (A-C, F-G) or two (D-E) independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; ****p< 0.0001; NS, not significant, by Mann-Whitney test (B-C, F) or one-way ANOVA (A, D-E, G). See also Figure S7.

Next, we tested whether blockade of COX-2-PGE2-EP receptor signaling could reverse exogenous DC suppression and thereby improve the therapeutic efficacy of DC vaccines. After validating the effectiveness of the IV injection route to deliver ovalbumin (OVA)-pre-loaded BM-DCs (DC vaccine) (Figures S7G and S7H), we compared the efficacy of IV administered DC vaccine in treating lung metastasis in WT versus Ptgs2ΔFb mice using an experimental metastasis model induced by AT3-OVA-Luc cells, which expressed the OVA antigen (Figure 7D, left). Accompanied by higher numbers of circulating OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in Ptgs2ΔFb mice than in WT mice, DC vaccine was shown to be therapeutically effective in reducing lung metastases in Ptgs2ΔFb mice, but not in WT mice (Figure 7D). However, the elevation of activated T cells by Ptgs2 cKO was not detected in tumor- or lung-draining lymph nodes (Figure S7I), suggesting that lymph node stromal COX-2 signaling is likely not involved in modulation of exogenous DC functions. Recapitulating the result from genetic deletion of COX-2, dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 similarly improved the therapeutic efficacy of DC vaccine as reflected by increased circulating OVA-specific CD8+ T cells and mitigated lung metastasis (Figure 7E). Thus, blockade of the COX-2-PGE2-EP2/EP4 signaling pathway improved the therapeutic potential of DC vaccine in treating lung metastasis.

Furthermore, we speculated that eradication of the immunosuppressive lung microenvironment through targeting of lung stromal signaling would enhance efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade, which is known to be undermined when tumors have robust immunosuppressive microenvironments (Saleh and Elkord, 2020). Indeed, administration of anti-PD-1 did not have a significant effect in alleviating established lung metastases in the AT3 model in WT mice, whereas it was effective in Ptgs2ΔFb mice (Figure 7F). Furthermore, the combination of anti-PD-1 with dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 was more effective than anti-PD-1 alone, reducing the metastatic burden by approximately 20 times compared to untreated controls (Figure 7G). Taken together, targeting lung fibroblast-associated COX-2-PGE2-EP2/4 signaling represents an effective means to treat breast cancer lung metastasis, as well as a promising combination therapy in synergy with immunotherapies for lung metastasis management.

Discussion

Despite numerous reports describing metastasis-promoting roles of BM-derived myeloid cells, little is known about whether these cells are intrinsically tumor-regulatory or acquire such capacities when they infiltrate organs. From the perspective of clinical translation, understanding tissue-specific immunity is critical for designing precise and effective therapeutics to treat organotropic metastases. In the present study, we found that exogenously implanted myeloid cells became dysfunctional or immunosuppressive only in the lung and not in any of several other tissues examined, indicating that immune cells can be reprogrammed in a distinct manner that depends on the tissue environment into which they are transmitted. Thus, our results will stimulate further studies on organ-specific immune responses in controlling organotropic metastases.

Stromal-immune cell interactions have drawn increasing attention in immunological research (Davidson et al., 2021; Koliaraki et al., 2020). During tissue homeostasis and tissue damage repair in various types of immunological diseases, structural stromal cells such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells are known to play fundamental roles in instructing immune cell development, survival, trafficking and function. With high-throughput sequencing technologies, stromal-immune cell interactions have started to be investigated at the single cell and tissue-specific levels (Buechler et al., 2021; Krausgruber et al., 2020). A growing number of such studies have focused on tissue homeostasis and immune diseases, whereas stromal-immune cell interactions remain less well characterized in cancer. Our results, by revealing COX-2+ fibroblast-mediated reprogramming of diverse myeloid cells in the lung pre-metastatic niche, suggest that targeting organ stromal cells could be a more efficient strategy to reshape an immune microenvironment than targeting a single population of myeloid cells in metastasis treatment.

COX-2 inhibitors have been proposed as promising therapeutics in breast cancer management (Mazhar et al., 2006; Regulski et al., 2016). However, some clinical trials using COX-2 inhibitors, such as the European Celecoxib Trial in Primary Breast Cancer (REACT), have not shown significant benefit for breast cancer patients (Coombes et al., 2021; Hamy et al., 2019; Hawk et al., 2018; Strasser-Weippl et al., 2018). This is also reflected in our mouse finding that celecoxib was ineffective in controlling lung metastasis of breast cancer. It is plausible that pharmacological inhibition of COX-2 may not be sufficient to reduce tissue-resident PGE2 levels due to compensatory effects by the COX-1 isoform. In our study, Ptgs2 cKO significantly reduced lung tissue PGE2 levels at both naïve and tumor-bearing states. We posit that this might be due to the de novo nature of the fibroblast Ptgs2 deletion, which further disrupts the fibroblast COX-2-PGE2-dependent induction of Ptgs2 expression in myeloid cells. Based on our results from mouse breast cancer models, blockade of PGE2 receptors, which remains less explored in clinical settings than inhibition of COX enzymes (Pannunzio and Coluccia, 2018; Reader et al., 2011), could be an effective approach in prevention and treatment of lung metastasis. Emerging data from multiple mouse models of solid cancers have shown promising effects from the combination of EP4 antagonists and PD1/PD-L1 blockade in inhibiting primary tumor growth (Lu et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2022; Sajiki et al., 2020; Tokumasu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021). In our work, dual inhibition of EP2 and EP4 was required to suppress lung metastasis, possibly owing to the potent immunosuppressive lung microenvironment. The preclinical efficacy of the combination of EP2 and EP4 inhibition with either DC vaccine or immune checkpoint inhibitor in our work is expected to stimulate translational studies of their application with immunotherapies to treat metastatic disease.

Given that the COX-2+ lung fibroblast program acts to remodel the lung microenvironment even in the absence of distal primary tumors, we expect that our results will also have relevance to a broad range of immune-associated pathologies other than metastasis, such as primary lung tumors, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary infections. In these pathological conditions, abnormalities of the innate and adaptive immune responses, excessive inflammation, and immunosuppression are major challenges from the standpoint of both mechanistic understanding and clinical treatment (Desai et al., 2018; Iams et al., 2020; Mizgerd, 2012). However, the underlying mechanisms driving these challenges remain poorly characterized, and current immune-based therapies are largely limited to targeting a single or a few types of immune cells (Goswami et al., 2022; Kolahian et al., 2016). Based on our findings, resident stromal cells, and in particular fibroblasts, represent a master switch in the lung immune microenvironment which broadly reshapes the lung immune landscape. Pharmacological targeting of lung stromal factors, such as COX-2-PGE2, is a promising avenue in the treatment of the immune-associated lung diseases.

Limitations of the study

In this work, we mainly relied on immunofluorescence, single cell and bulk RNA-seq, exogenous myeloid cell transplantation, and ex vivo co-cultures. The in situ molecular mechanisms and cell-cell interaction dynamics of COX-2+ AdvF-elicited reprograming of different lung-resident myeloid cells at spatial-temporal levels should be further investigated by leveraging currently advancing spatial transcriptomics and metabolomics approaches, as well as intravital imaging techniques. In addition, we characterized the role of COX-2+ AdvFs only in the context of lung metastasis models; future efforts will be required to more fully understand this lung fibroblast subset in maintaining lung-resident immunity in homeostasis, inflammation, lung cancer and other lung diseases.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Guangwen Ren (Gary.Ren@jax.org).

Materials Availability

All unique and stable materials generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact under a Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

Bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq data generated from this study were deposited in public data repositories and the accession numbers are listed in the KEY RESOURCES TABLE. All these data are publicly available as of the date of publication.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

The following datasets were downloaded and reanalyzed: microarray datasets for human normal tissues: GSE7307 and GSE3526 (Roth et al., 2006); scRNA-seq datasets for human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis samples: GSE135893 (Habermann et al., 2020); scRNA-seq datasets for human lung tissues: EGAS00001004344 (Travaglini et al., 2020).

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Alexa Fluor® 700 anti-mouse CD45 (Clone 30-F11) | BioLegend | Cat#103128; RRID: AB_493715 |

| APC anti-mouse CD45 (Clone QA17A26) | BioLegend | Cat#157605; RRID: AB_2876537 |

| APC/Fire™ 750 anti-mouse CD45.1 (Clone A20) | BioLegend | Cat#110752; RRID: AB_2629806 |

| PE anti-mouse/human CD11b (Clone M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat#101207; RRID: AB_312790 |

| Brilliant Violet 650™ anti-mouse/human CD11b (Clone M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat#101259; RRID: AB_2566568 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD11c (Clone N418) | BioLegend | Cat#117328; RRID: AB_2129641 |

| PE anti-mouse CD11c (Clone N418) | BioLegend | Cat#117307; RRID: AB_313776 |

| APC anti-mouse CD172a (Clone P84) | BioLegend | Cat#144013; RRID: AB_2564060 |

| Anti-mouse/rat XCR1 (Clone QA20A05) | BioLegend | Cat#109402; RRID: AB_2910282 |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6C (Clone HK1.4) | BioLegend | Cat#128001; RRID: AB_1134213 |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6G (Clone 1A8) | BioLegend | Cat#127601; RRID: AB_1089179 |

| Brilliant Violet 570™ anti-mouse Ly-6C (Clone HK1.4) | BioLegend | Cat#128030; RRID: AB_2562617 |

| Pacific Blue™ anti-mouse Ly-6G (Clone 1A8) | BioLegend | Cat#127612; RRID: AB_2251161 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD24 (Clone M1/69) | BioLegend | Cat#101822; RRID: AB_756048 |

| PE anti-mouse H-2Kd (Clone SF1-1.1) | BioLegend | Cat#116607; RRID: AB_313742 |

| PE anti-mouse H-2Kb/H-2Db (Clone 28-8-6) | BioLegend | Cat#114607; RRID: AB_313598 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse I-A/I-E (Clone M5/114.15.2) | BioLegend | Cat#107627; RRID: AB_1659252 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-mouse CD19 (Clone 6D5) | BioLegend | Cat#115522; RRID: AB_389329 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-mouse CD90.2 (Clone 30-H12) | BioLegend | Cat#105318; RRID: AB_492888 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-mouse Ly-6G (Clone 1A8) | BioLegend | Cat#127610; RRID: AB_1134159 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-Mouse Siglec-F (Clone E50-2440) | BD Biosciences | Cat#562680; RRID: AB_2687570 |

| APC anti-mouse CD3 (Clone 17A2) | BioLegend | Cat#100236; RRID: AB_2561456 |

| PE/Cyanine5 anti-mouse CD4 (Clone RM4-5) | BioLegend | Cat#100514; RRID: AB_312717 |

| Brilliant Violet 650™ anti-mouse CD8a (Clone 53-6.7) | BioLegend | Cat#100742; RRID: AB_2563056 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD31 (Clone 390) | BioLegend | Cat#102418; RRID: AB_830757 |

| APC/Fire™ 750 anti-mouse CD326 (Clone G8.8) | BioLegend | Cat#118229; RRID: AB_2629757 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-mouse CD140a (Clone APA5) | BioLegend | Cat#135923; RRID: AB_2814036 |

| COX-2 antibody (Rabbit) | Cayman Chemical | Cat#160126 |

| GAPDH antibody (Rabbit) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5174S |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#31460 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 594. RRID: AB_141637 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21207 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 405 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A48258 |

| Donkey anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A48272 |

| Anti-mouse CD3e (Clone 145-2C11) | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0001-1 |

| Anti-mouse CD28 (Clone 37.51) | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0015-1 |

| Anti-mouse PD-1 (Clone RMP1-14) | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0146 |

| Rat IgG2a isotype control (Clone 2A3) | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0089 |

| Anti-mouse IL-1β (Clone B122) | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0246 |

| APC Pro5® MHC Class I Pentamers | ProImmune | Cat#F093-4A-D |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Collagenase, Type IV, powder | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#17104019 |

| Dnase I | MilliporeSigma | Cat#DN25 |

| Recombinant Murine IL-4 | PeproTech | Cat#214-14 |

| Recombinant Murine GM-CSF | PeproTech | Cat#315-03 |

| Recombinant Murine IL-1β | PeproTech | Cat#211-11B |

| Ovalbumin, Alexa Fluor™ 647 Conjugate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#O34784 |

| Prostaglandin E2 | Cayman Chemical | Cat#14010 |

| MLN120B | Cayman Chemical | Cat#32819 |

| Celecoxib | Cayman Chemical | Cat#10008672 |

| PF-04418948 | Cayman Chemical | Cat#15016 |

| MF498 | Cayman Chemical | Cat#15973 |

| D-Luciferin Firefly, potassium salt | Gold Biotechnology | Cat#LUCK |

| Recombinant Human IL-1β | InvivoGen | Cat#rcyec-hil1b |

| OVA 257-264 | InvivoGen | Cat#vac-sin |

| OVA 323-339 | InvivoGen | Cat#vac-isq |

| Standard Macrophage Depletion Kit (Clodrosome® + Encapsome®) | Encapsula NanoSciences | Cat#SKU# CLD-8901 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Prostaglandin E2 Parameter Assay Kit | R&D Systems | Cat#KGE004B |

| Mouse IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 Quantikine ELISA Kit | R&D Systems | Cat#MLB00C |

| Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus w/ TRI Reagent | Zymo | Cat#R2073 |

| High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#4368814 |

| PowerUp SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A25778 |

| Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/28 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#11-456-D |

| CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C34554 |

| CellTracker™ Orange CMTMR Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C2927 |

| CellTracker™ Deep Red Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C34565 |

| Cytofix/Cytoperm kit | BD Biosciences | Cat#555028 |

| Precision Count Beads | Biolegend | Cat#424902 |

| CD4 (L3T4) Microbeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-117-043 |

| CD8a (Ly-2) Microbeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-117-044 |

| CD90.2 Microbeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-121-278 |

| NK Cell Isolation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-115-818 |

| Monocyte Isolation Kit (BM) | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-100-629 |

| Anti-Ly6G MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-120-337 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-seq data of BM-DCs | This paper | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-11873 |

| RNA-seq data of lung myeloid cells from WT and Ptgs2-cKO mice | This paper | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-11888 |

| RNA-seq data of ex vivo cultured lung fibroblasts | This paper | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-11887 |

| scRNA-seq data of lung stromal cells | This paper | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-11879 |

| scRNA-seq data of lung CD140a+ fibroblasts | This paper | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-11875 |

| scRNA-seq data of lung immune cells from WT and Ptgs2-cKO mice | This paper | GEO: GSE206449 |

| scRNA-seq data of human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis samples | (Habermann et al., 2020) | GEO: GSE135893 |

| scRNA-seq data of hfuman lung tissues | (Travaglini et al., 2020) | EGA: EGAS00001004344 |

| Microarray datasets of human normal tissues | (Roth et al., 2006) | GEO: GSE7307, GSE3526 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 4T1 | ATCC | Cat#CRL-2539 |

| AT3 | Gift from S.I. Abrams | N/A |

| E0771 | CH3 Biosystems | Cat#940001 |

| YAC-1 | ATCC | Cat#TIB-160 |

| 4T1-Luc | (Li et al., 2020a) | N/A |

| 4T1-GFP | This paper | N/A |

| AT3-gcsf | (Gong et al., 2022) | N/A |

| AT3-Luc | (Li et al., 2020a) | N/A |

| AT3-mCherry | (Li et al., 2020a) | N/A |

| AT3-GFP | (Li et al., 2020b) | N/A |

| AT3-gcsf-GFP | This paper | N/A |

| AT3-OVA-Luc | This paper | N/A |

| E0771-Luc | (Li et al., 2020a) | N/A |

| E0771-GFP | This paper | N/A |

| Human lung mesenchymal cells | Sciencell | Cat#7540 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| BALB/cJ | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 000651 |

| C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 000664 |

| OT-I: C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 003831 |

| OT-II: B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 004194 |

| Ptgs2−/−: B6;129S-Ptgs2tm1Jed/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 002476 |

| Ptgs2Luc: B6;129S4-Ptgs2tm2.1Hahe/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 030853 |

| Ptgs2 flox/flox: B6;129S4-Ptgs2tm1Hahe/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 030785 |

| PdgfraCre: C57BL/6-Tg(Pdgfra-cre)1Clc/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 013148 |

| PdgfraCre; Ptgs2flox/flox | This paper | N/A |

| FVB/N-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 002374 |

| MMTV-PyMT: B6.FVB-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/LellJ | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 022974 |

| B6 Cd45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 002014 |

| PdgfaCre; Ptgs2flox/flox; MMTV | This paper | N/A |

| Il1r1−/−: B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 003245 |

| CD140aEGFP: B6.129S4-Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 007669 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 for primer sequences | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLenti CMV Puro LUC (w168-1) | (Campeau et al., 2009) | Addgene#17477 |

| pLV-mCherry | Tsoulfas lab | Addgene #36084 |

| pcDNA3-OVA | (Diebold et al., 2001) | Addgene #64599 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| BD FACSDiva software | BD Biosciences | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/ |

| FlowJo | BD Biosciences | https://flowjo.com |

| R (version 4.0.2) | R Core Team (2020) | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| Seurat (version 3.2.2) | Satija Lab | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| limma (version 3.46.0) | (Ritchie et al., 2015) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html |

| Metascape | (Zhou et al., 2019) | https://metascape.org/ |

| DoRothEA (version 1.1.2) | (Holland et al., 2020) | https://saezlab.github.io/dorothea/ |

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | QIAGEN | https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis/ |

| GraphPad Prism (version 8.2.1) | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Biorender | Biorender | https://biorender.com/ |

| ImageJ (1.53c) | ImageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Other | ||

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

BALB/cJ (JAX #000651), C57BL/6J (JAX #000664), B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (B6 Cd45.1, JAX #002014), C57BL/6-Tg (TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I, JAX #003831), B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J (OT-II, JAX #004194), B6;129S-Ptgs2tm1Jed/J (Ptgs2−/−, JAX #002476), B6;129S4-Ptgs2tm2.1Hahe/J (Ptgs2Luc, JAX #030853), B6;129S4-Ptgs2tm1Hahe/J (Ptgs2 flox/flox, JAX #030785), C57BL/6-Tg(Pdgfra-cre)1Clc/J (PdgfraCre, JAX #013148), B6.129S4-Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor/J (CD140aEGFP, JAX #007669), B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J (Il1r1−/−, JAX #003245), FVB/N-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/J (JAX #002374) and MMTV-PyMT (B6.FVB-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/LellJ (JAX #022974) mice were all obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. B6;129S4-Ptgs2tm1Hahe/J (Ptgs2 flox/flox) and C57BL/6-Tg(Pdgfra-cre)1Clc/J (PdgfraCre) mice were crossed to generate Ptgs2 conditional knockout (Ptgs2ΔFb) mice. The Ptgs2ΔFb mice were further crossed with MMTV-PyMT (B6.FVB-Tg(MMTV-PyVT)634Mul/LellJ) mice to generate PdgfraCre; Ptgs2flox/flox; MMTV-PyMT (MMTV-PyMT Ptgs2ΔFb) mice. Animal handling and experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Jackson Laboratory.

Female mice aged 8–10 weeks were used unless indicated otherwise. For all animal work, mice with similar age and weight were randomized before tumor inoculation. Prior to further treatment, the tumor-bearing mice were randomized with respect to their tumor sizes to ensure all treatment groups had equivalent tumor burden before treatment. All animal experiments were performed in the same well-controlled pathogen-free facility with the same mouse diets.

Cell lines

4T1 and YAC-1 cells were purchased from the ATCC. E0771 cells were purchased from CH3 Biosystems. AT3 cell line was a generous gift from S.I. Abrams at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. To generate AT3-Luc, E0771-Luc or 4T1-Luc cells, the tumor cells were infected with luciferase-expressing lentivirus (Addgene) (Campeau et al., 2009). For OVA labeling, the AT3-Luc cells were transfected with pcDNA3-OVA (Addgene) (Diebold et al., 2001) to generate AT3-OVA-Luc tumor cells. For mCherry labeling, AT3 cells were infected with mCherry-expressing lentivirus (Addgene) to generate AT3-mCherry cells. To overexpress G-CSF, AT3 cells were infected with g-csf (Csf3)-expressing lentivirus (the vector was a gift from R.A. Weinberg, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) to generate AT3-gcsf cells. To generate 4T1-GFP, AT3-GFP, AT3-gcsf-GFP and E0771-GFP cells, the tumor cells were infected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing lentivirus (Addgene). Human lung fibroblast-like cells (mesenchymal stem cells) were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C and confirmed to be mycoplasma free.

Generation of BM-DCs

Bone marrow cells from naïve mice were isolated by flushing femurs, tibias and humeri with RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Following suspension in ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis buffer to lyse red blood cells, bone marrow cells were passed through a 40 μm filter. Then cells were resuspended at a density of 1 × 106 cells per ml, cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium containing GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml). The cultured medium was entirely discarded on day 4 and new warmed medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4 was added. On day 7, the loosely-adherent cells were collected for further experiments.

To screen the lung fibroblast-derived candidate soluble factors to modulate BM-DCs, BM-DCs were treated with the candidate regulators for 16 hours and then MHC-II expression levels in BM-DCs were measured by flow cytometry. The final concentration of each following reagent was used at 10 ng/ml unless indicated otherwise: β-estradiol, interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 2 (IL-2), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interleukin 33 (IL-33), interleukin 13 (IL-13), PGE2, interleukin 4 (IL-4), tretinoin, platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB), progesterone, and interleukin 10 (IL-10).

To determine the impact of tissue environments on BM-DCs in vivo, naïve mice or orthotopic tumor-bearing mice (pre-metastatic stage) were IV injected with CellTracker™ orange dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) labeled BM-DCs (5×106 cells for each mouse). 16 hours later, mice were euthanized, and different tissues and organs were harvested for detection of the labeled BM-DCs and their expression of MHC molecules by flow cytometry.

Primary cell isolation and culture

Splenic CD3+ T cells or NK cells were isolated from naïve mice using anti-CD90.2 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) or NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Splenic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were isolated from naïve OT-II or OT-I mice by using CD4 (L3T4) or CD8a (Ly-2) microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), respectively. BM-derived monocytes were isolated from naïve mice using the Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Neutrophils were isolated from lung tissues of naïve or tumor-bearing mice using anti-Ly6G microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Viability and purity of isolated cells were assessed with flow cytometry to be above 90%.

For the primary culture of lung fibroblasts, sorted CD45−CD31−CD326−CD140a+ fibroblasts were cultured in the MesenCult™ Basal Medium (STEMCELL Technologies). The first to third passages of the primary fibroblasts were used for the ex vivo experiments.

To prepare fibroblast-derived conditioned medium (CM), ex vivo cultured lung fibroblasts or freshly sorted lung CD140a+ fibroblasts were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium at a density of 5×105 cells/ml for 16 hours. Then the supernatant was collected after centrifuging at 1, 000g for 20 min to remove cells and debris. The freshly collected supernatant was used as CM for further experiments.

Tissue dissociation

Peripheral blood (PB) was collected through cardiac puncture in 5 mM EDTA in PBS with 1 ml syringe. Then PB samples were lysed with ACK lysis buffer for 5 min and centrifuged. Cells were filtered through a 40-μm strainer and resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 5% FBS. For BM cells, the tibias and femurs of both hind legs of the mice were flushed with RPMI-1640 medium. Then cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer and passed through a 40-μm strainer. Lungs and livers were extracted and minced, and then digested with 2 mg/ml collagenase IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma) in RPMI-1640 medium for 1 hour at 37 °C. The cells were then filtered through 70-μm strainers to remove small fragments of undigested tissue. Spleens were harvested and ground with syringe plungers and the cell suspensions were filtered through 70-μm strainers. For lung, liver and spleen, the red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer and then homogenized into single cell suspensions with 40-μm strainers.

Flow cytometry and sorting

Prepared single cell suspensions from mouse tissues or ex vivo cultured cells were stained on ice with primary fluorophore conjugated antibodies (1:200 diluted) and then washed with FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS) for identification of cell populations by flow cytometry. 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for dead cell discrimination. For the intracellular staining of COX-2, single-cell suspensions were first stained with Live/Dead Fixable stain BV510 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and surface primary antibodies, then fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then stained with primary antibody against COX-2 (1:500 diluted) for 2h on ice followed with secondary antibody (1:1000 diluted) staining for 1 hour at 4°C. IgG was stained as negative control for flow cytometry gating. Then the samples were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. For cell counting on the flow cytometer, Precision Count Beads™ (Biolegend) were utilized to obtain the absolute counts of cells of interest in each lung tissue according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSymphony A5 cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). Cell sorting was performed on the BD FACSAria II cell sorter with a 100 μm nozzle. All antibodies were purchased from either Biolegend or BD Biosciences. Detailed information regarding antibodies is listed in the KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

Determination of the pre-metastatic stages of breast tumor models

Flow cytometry was used to determine the pre-metastatic versus metastatic stages for the breast cancer models (4T1, AT3, AT3-gcsf and E0771). Using 4T1 model as an example, the mice were orthotopically implanted with 4T1-GFP tumor cells (5 × 105 cells for each mouse), and on days 10, 15, 20 and 25, the percentages of tumor cells in the mouse lungs were quantified by flow cytometry. Primary tumor tissues and naïve mice-derived lung samples (day 0) were set as positive or negative controls, respectively. The pre-metastatic stage was designated as a period before overt metastasis occurs in distant lung tissues, when either no or very few tumor cells were detected. In addition to the flow cytometry method, the evidence of metastasis in the lung was also validated by histological examination. Accordingly, we identified day 15 or earlier as the pre-metastatic stage for the 4T1 model. Similarly, the pre-metastatic stages for AT3, AT3-gcsf and E0771 models are day 15 or earlier, day 15 or earlier, and day 20 or earlier, respectively.

DC functional assays

To measure the antigen-specific T cell priming ability, BM-DCs were pre-incubated with OVA257-264 or OVA323-339 peptide (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 2 hours before washing. Then the BM-DCs were co-cultured with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled OT-I CD8+ T cells or OT-II CD4+ T cells at a ratio of 1:3 for 3 days. T cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry.

To assess the antigen uptake ability, BM-DCs were incubated with OVA-Alexa Fluor 647 (0.1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed and stained with antibodies and presence of Alexa Fluor 647 signal was analyzed by flow cytometry in BM-DCs.

To measure the immunosuppressive ability, BM-DCs were pre-incubated with WT or Ptgs2−/− lung fibroblast CM for 16 hours, and mixed with untreated BM-DCs (pre-loaded with OVA257-264 or OVA323-339 peptide) at a ratio of 1:1. Then the CFSE-labelled naïve splenic T cells (from OT-1 or OT-II mice) were added (CM-treated BM-DCs : antigen-loaded BM-DCs : T cells=1:1:3) and co-cultured for 3 days. T cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry.

Monocyte-mediated T cell suppression assay

To measure the T cell suppression by monocytes, BM-derived monocytes were pre-incubated with WT or Ptgs2−/− lung fibroblast CM for 24 hours before washing. Splenic CD3+ T cells were isolated from naive mice and labeled with CFSE. Then monocytes (2 × 105 cells) were co-cultured with T cells (5 × 105 cells) in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 beads (Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/28, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 days at 37°C. T cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry.

In vitro NK cell cytotoxicity assay

BM-DCs or BM-derived monocytes were pre-treated with lung fibroblast CM for 24 hours, and co-cultured with 2×105 purified splenic NK cells at a ratio of 1:1 for 2 hours in a 96-well round bottom plate. CellTracker™ deep red dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) labeled YAC-1 target cells were then added at the NK cell: target cell ratio of 5:1 and co-cultured for an additional 4 hours. The cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and the percentage of dead target cells was measured with flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence

To determine the localization of implanted BM-DCs and lung-resident fibroblasts in the lung, CD140aEGFP mice were IV injected with CellTracker™ orange dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) labeled BM-DCs (5×106 cells for each mouse). 16 hours later, the lungs were dissected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Then the tissues were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek) and tissue sections (10 μm) were prepared with the CryoStar NX70 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cell nucleus was stained with DAPI.

To detect COX-2 protein level, the lung CD140a+ fibroblasts from WT or Ptgs2ΔFb mice, or vehicle or IL-1β treated lung fibroblasts were first fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 30 min. Then the cells were washed with PBS three times, and incubated with COX-2 primary antibody (1:1000 diluted) overnight at 4°C. The next day, the cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000 diluted) for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, the cells were stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) to label the cell nucleus.

To determine the localization of COX-2+ fibroblasts and their in situ interactions with different types of myeloid cells, the lungs of CD140aEGFP mice were harvested and fixed with 4% PFA. Then the tissues were embedded in OCT compound and sectioned at 10 μm. Cryosections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton, blocked with 5% BSA, and stained with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following antibodies were used to indicate different types of myeloid cells: myeloid cells (CD45 and CD11b), CD11b+ DCs (CD11b and CD172a), CD103+ DCs (CD11c and XCR1), monocytes (Ly6C), and neutrophils (Ly6G). The next day, the lung sections were stained with secondary antibodies (diluted 1:500) for 1 hour at room temperature. All the antibody information is listed in the KEY RESOURCES TABLE. The fluorescent images were captured on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica).

Quantification of PGE2 and IL-1β