Abstract

Background

The risk of dementia is higher in women than men. The metabolic consequences of estrogen decline during menopause accelerate neuropathology in women. The use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the prevention of cognitive decline has shown conflicting results. Here we investigate the modulating role of APOE genotype and age at HRT initiation on the heterogeneity in cognitive response to HRT.

Methods

The analysis used baseline data from participants in the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) cohort (total n= 1906, women= 1178, 61.8%). Analysis of covariate (ANCOVA) models were employed to test the independent and interactive impact of APOE genotype and HRT on select cognitive tests, such as MMSE, RBANS, dot counting, Four Mountain Test (FMT), and the supermarket trolley test (SMT), together with volumes of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions by MRI. Multiple linear regression models were used to examine the impact of age of HRT initiation according to APOE4 carrier status on these cognitive and MRI outcomes.

Results

APOE4 HRT users had the highest RBANS delayed memory index score (P-APOE*HRT interaction = 0.009) compared to APOE4 non-users and to non-APOE4 carriers, with 6–10% larger entorhinal (left) and amygdala (right and left) volumes (P-interaction= 0.002, 0.003, and 0.005 respectively). Earlier introduction of HRT was associated with larger right (standardized β= −0.555, p=0.035) and left hippocampal volumes (standardized β= −0.577, p=0.028) only in APOE4 carriers.

Conclusion

HRT introduction is associated with improved delayed memory and larger entorhinal and amygdala volumes in APOE4 carriers only. This may represent an effective targeted strategy to mitigate the higher life-time risk of AD in this large at-risk population subgroup. Confirmation of findings in a fit for purpose RCT with prospective recruitment based on APOE genotype is needed to establish causality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-022-01121-5.

Introduction

More than two-thirds of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients are women [1, 2]. The recent 2022 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report shows that the age-standardized dementia prevalence is higher in women (female-to-male ratio= 1.69 (1.64–1.73)) [3]. Thus, higher incident cases in women cannot simply be explained by greater life expectancy [2, 4, 5]. The neurophysiological impact of estrogen decline during menopause is emerging as the main aetiological basis for the higher prevalence of AD in females [6, 7]. Estrogen receptors are expressed throughout the brain, with estrogen regulating multiple physiological processes including neuronal synaptic plasticity, neuroinflammation, brain macronutrient utilization, DHA metabolism, and blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity [8–10].

Consequently, the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) during the menopausal transition and post-menopausal period is being considered as a strategy to mitigate cognitive decline. Early observation studies showed that oral estrogen may be protective against dementia [11], with a risk reduction of 34% in an early meta-analysis [12]. However, results of clinical trials have been inconsistent [13, 14] or even shown harmful effects [15]. For example, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study (WHIMS), in women over the age of 65 years, showed that the use of oral estrogen alone (conjugated Equine Estrogen, CEE) or CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) resulted in a 49% or 76% increased risk of dementia respectively [16]. A recent meta-analysis showed that the negative effect of HRT on global cognition has been predominately tested in those >60years. In this meta-analysis, only two studies recruited participants <60years, with one showing no impact of oral estrogen on global cognition and the second showing a positive impact of CEE plus MPA on global cognition [17]. Limited recent, mainly preclinical, data has identified APOE genotype and age of HRT initiation as potential modulators of the HRT cognitive response [7, 18, 19].

APOE genotype is the most important common genetic determinant of cognitive decline and AD risk. In Caucasians, a 3–4-fold and 12–15-fold increased risk of AD is evident in APOE3/E4 and APOE4/E4 relative to the wild-type APOE3/E3 genotype with several years earlier age of onset [20]. A greater penetrance of an APOE4 genotype in females, first reported in the early 90s [6, 21], is likely to be an important contributor to the higher AD rates in women [6]. This somewhat understudied association has been reiterated over the years [22–24]. More decline in MMSE, immediate and delayed memory scores was observed with an increasing number of APOE4 alleles in women compared to men [25].

The other possible contributor of inconsistencies to the impact of HRT on AD risk is the timing of its initiation [26]. For cognition and AD risk, HRT intervention may be most beneficial if introduced before a certain threshold of neuronal damage accumulates [7], with potentially a ‘critical window’ where HRT can be neuroprotective [27, 28]. This critical window is likely to be during the transition to menopause, where gradual estrogen decline increases the brain liability to AD-related pathologies. In a UK BIOBANK analysis, despite showing that cumulative life-time estrogen exposure was associated with increased brain aging (measured by cortical thickness, and cortical and subcortical volumes), a subgroup analysis revealed that women who started HRT earlier had less apparent brain aging compared to later starters. Importantly, this effect of HRT timing was only evident in APOE4 carriers [29], raising the notion that the interaction of APOE and HRT initiation might have a significant effect on brain health later in life. However, to date, there are no comprehensive analyses investigating APOE genotype and HRT interactions on multiple cognitive and MRI outcomes in humans, which the current study addresses.

Therefore, we hypothesize that HRT will have more cognitive benefits in APOE4 compared to non-APOE4 women, in particular when introduced early during menopausal transition. The independent and interactive effect of APOE genotype and HRT use on select cognitive function tests and medial temporal lobe–related MRI brain volumes was tested cross-sectionally in the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) cohort.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design of the EPAD cohort

The European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) project started in 2015 [30]. Its main objectives were to develop longitudinal models over the entire course of AD prior to dementia clinical diagnosis. These datasets will help in setting up a proof-of-concept trial (PoC) for the secondary prevention of AD [31]. Participants were included if they were above 50 years, with no dementia diagnosis at baseline. They should not have had any medical or psychiatric illness that could potentially exclude them from a future PoC trial. Recruitment was carried out in ten European countries.

The current analysis was carried out on the EPAD-LCS-v.IMI dataset, released in October 2020 and accessed from the Workbench of the Alzheimer’s Disease Data Initiative (ADDI) Portal website: https://portal.addi.ad-datainitiative.org/. The baseline (V1) data from 1906 participants was included, with numbers varying according to the availability of cognitive test scores and neuroimaging data.

Demographics, APOE genotype, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) data

Participants’ sex, age, years of education, handedness, and marital status were downloaded and analyzed. Those with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale score > 1.0 were excluded, as scores ≥ 1 are indicative of cognitive impairment [32].

APOE genotype data were categorized into a non-E4 group, which included E2/E2, E2/E3, and E3/E3, and the E4 group, which included E3/E4 and E4/E4. E2/E4 genotype was excluded from the analysis as it includes both the protective and risk alleles.

HRT treatment data was used for women who were current or previous users of estrogen alone (estradiol, estriol, and estrone preparations) or combined estrogen plus progestogens preparations (native progesterone or progestins), via both oral and transdermal routes of administration, and at different doses. Age at HRT initiation was calculated by subtracting the duration of HRT use from the age of the participant.

Cognitive test

The cognitive tests analyzed were based on the recommendations of the EPAD scientific advisory group [33] and included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Dot counting to evaluate verbal working memory [34], and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) total score and its five main indices that score for attention, delayed memory, immediate memory, language, and visuo-construction. Items comprising each index were also analyzed where necessary [35]. The RBANS total score is taken as the primary outcome of EPAD [36] due to its ability to detect and track very early cases of cognitive decline [37]. The Four Mountain Test (FMT) was used to detect changes in the allocentric and orientation spatial memory [38]. The supermarket trolley virtual reality test (SMT) was used to test for changes in egocentric space [39].

MRI brain volumetric parameters

MRI volumetric brain neuroimaging data were downloaded from the ADDI portal. The protocols used, quality controls, and data transfer are described in detail elsewhere [36]. Briefly, brain MRI scans were carried out using standardized acquisition protocols. Regional gray matter volumes were determined through the 3D-T1 weighted images using a segmentation process based on atlas propagation with the Learning Embeddings for Atlas Propagation (LEAP) framework [40]. The analysis focussed on the medial temporal lobe (MTL) as the main brain region regulating cognition and memory processing [41]. The MTL includes the hippocampus (right and left), parahippocampus (right and left), entorhinal cortex (right and left), and amygdala (right and left). A wider exploratory analysis for 20 different brain regions was carried out separately and presented in the supplemental document.

Statistical analysis

All data files were processed using RStudio and the statistical analysis was conducted by SPSS version 28 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Variables were checked for normality; box cox transformation and z-scoring were performed when required. Regional MRI volumes were adjusted to whole brain volume before statistical analysis.

Demographic analysis

Age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR scores were compared between non-APOE4s and APOE4s, and HRT users and non-users. Independent t-tests were used to determine differences in normally distributed variables (age, years of education, and age at HRT initiation), with the Mann-Whitney test used for skewed variables (duration of HRT use). Chi-square test was used for categorical variables (marital status, handedness, CDR, and cardiovascular medication use).

Analysis of the impact of APOE genotype and HRT on cognition and volumes of medial temporal lobe components

Analysis of covariate analysis (ANCOVA) was used to investigate the main and interactive effects of APOE genotype and HRT use, on cognition and MTL brain volumes. Multivariate ANCOVA (MANCOVA) was used on RBANS indices and MTL regions. HRT and APOE genotype were the independent variables, while select cognitive tests and regional brain volumes were the dependent variables. Adjustment of the brain volumes to the whole brain volume was carried out before statistical analysis. Age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR were used as covariates in the ANCOVA model.

Correction for multiple comparisons was carried out for each of the eight MTL regions (8 × 3) using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method. Uncorrected p-values for other brain regions (n=23) are represented in the supplemental information (Supplemental Table 1). Similarly, FDR correction for multiple testing was carried out for the cognitive tests (10 tests × 3).

To measure the magnitude of HRT-use effect on cognitive tests and MRI brain regions in APOE4 carriers versus non-carriers, an effect size analysis was carried out. Cohen’s d [42] was used to compare the mean values between HRT users and non-users within each genotype group using the following equation: ( MeanHRT-meanno-HRT)/ standard deviation. In addition, partial Eta squared was used to measure the proportion of variance and was reported from the between-subject effect of the ANCOVA model.

Regression analysis

Multiple linear regression was carried out to determine the association between the age of HRT initiation with cognition and MTL-specific areas as dependent variables. Model-1 covariates: Age + years of education + handedness + marital status + CDR. Model-2: Model 1 covariates + age of HRT initiation. Reported results are for model-2.

Results

Demographics of women of the EPAD study at baseline according to APOE genotype

There was no difference in age, marital status, handedness, CDR, number of HRT users, and duration of HRT use between the APOE4 and non-APOE4 groups. APOE4 carriers had less formal education (P= 0.014) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Select baseline characteristics in women according to APOE genotype status

| Non-E4 (n=675) | E4 (n=399) | Total (n=1074) | PAPOE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 65.2 (7.3) | 65.1 (7.3) | 65.1 (7.3) | NS |

| Years of education (mean, SD) | 14.4 (3.8) | 13.8 (3.6) | 14.1 (3.7) | 0.014 |

| Marital status (n, %) | NS | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 443 (65.6) | 280 (70.0) | 723 (67.5) | |

| Divorced | 108 (16.0) | 48 (12.0) | 156 (14.3) | |

| Single | 64 (9.5) | 31 (7.8) | 95 (8.5) | |

| Widowed | 59 (8.7) | 40 (10.0) | 99 (9.6) | |

| Handedness (right/left) | 614/46 | 371/17 | 985/63 | NS |

| CDR (n, %) | NS | |||

| 0.0 | 477 (71.6) | 265 (68.5) | 742 (70.2) | |

| 0.5 | 189 (28.4) | 122 (31.5) | 337 (29.8) | |

| HRT use | NS | |||

| Yes/no | 52/623 | 31/368 | 83/991 | |

| Current/past users | 46/6 | 30/1 | 76/7 | |

| Duration in years (mean, SD) | 7.2 (6.26) | 8.0 (7.17) | 7.5 (6.58) | |

| Age at HRT initiation (years) | 56.2 (8.36) | 56.5 (7.01) | 56.4 (7.83) | |

| Current CV medication (n, %) | 196 (29.0) | 130 (32.5) | 326 (30.4) | NS |

NS non-significant, CDR Clinical Dementia Rating, CV cardiovascular

Impact of APOE genotype and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use on cognitive status in women

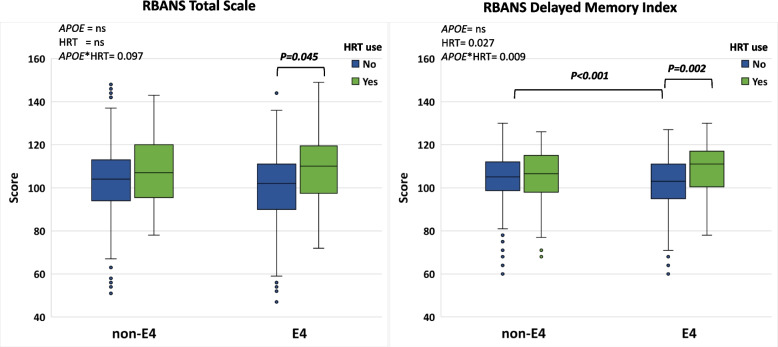

A trend towards an APOE*HRT interaction (P-interaction = 0.097) was evident for the total RBANS score which was significant for the RBANS delayed memory index (P-interaction = 0.009), with scores consistently higher in APOE4 HRT users compared to all other groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cognitive outcomes scores (mean±SEM) according to HRT use and APOE4 genotype status

| Non-E4 | E4 | PAPOE | PHRT | PAPOE*HRT | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-HRT | n | HRT | n | Total | n | p-HRT | No-HRT | n | HRT | n | Total | n | p-HRT | ||||

| MMSE total score | 28.49 ±0.07 | 603 | 28.43 ±0.36 | 50 | 28.49 ±0.07 | 653 | 0.607 | 28.15 ±0.11 | 350 | 28.22 ±0.30 | 30 | 28.16 ±0.10 | 380 | 0.960 | 0.565 | 0.724 | 0.782 |

| Dot counting score | 16.60 ±0.22 | 389 | 17.05 ±1.06 | 32 | 16.62 ±0.22 | 421 | 0.726 | 16.24 ±0.30 | 235 | 17.44 ±0.71 | 21 | 16.32 ±0.29 | 256 | 0.848 | 0.953 | 0.942 | 0.710 |

| RBANS scores | |||||||||||||||||

| RBANS total scale | 103.57 ±0.62 | 600 | 105.04 ±2.78 | 49 | 103.63 ±0.61 | 649 | 0.921 | 100.52 ±0.85 | 351 | 106.68 ±3.44 | 29 | 100.88 ±0.83 | 380 | 0.045 | 0.488 | 0.128 | 0.097 |

| RBANS attention index | 97.65 ±0.70 | 601 | 102.61 ±2.73 | 28 | 97.86 ±0.68 | 629 | 0.222 | 97.23 ±0.93 | 352 | 102.23 ±3.34 | 29 | 97.51 ±0.90 | 381 | 0.706 | 0.818 | 0.297 | 0.652 |

| RBANS delayed memory index | 102.09 ±0.59 | 602 | 102.07 ±2.46 | 28 | 102.09 ±0.58 | 630 | 0.757 | 98.29 ±0.85 | 352 | 108.37 ±2.79 | 29 | 98.85 ±0.81 | 381 | 0.002 | 0.695 | 0.027a | 0.009a |

| RBANS immediate memory index | 106.55 ±0.58 | 602 | 105.18 ±30 | 28 | 106.49 ±0.57 | 630 | 0.854 | 101.65 ±0.87 | 352 | 105.59 ±3.83 | 29 | 101.87 ±0.85 | 381 | 0.150 | 0.434 | 0.307 | 0.209 |

| RBANS language index | 100.10 ±0.47 | 602 | 100.79 ±2.61 | 28 | 100.13 ±0.47 | 630 | 0.752 | 99.30 ±0.69 | 353 | 101.50 ±2.84 | 29 | 99.42 ±0.67 | 382 | 0.303 | 0.399 | 0.536 | 0.311 |

| RBANS visuo-constructional index | 105.16 ±0.65 | 602 | 106.82 ±2.95 | 28 | 105.23 ±0.63 | 630 | 0.310 | 104.66 ±0.92 | 352 | 108.32 ±2.91 | 29 | 104.87 ±0.88 | 381 | 0.483 | 0.163 | 0.938 | 0.233 |

| FMT total score | 8.31 ±0.43 | 32 | 9.33 ±0.33 | 3 | 8.40 ±0.40 | 35 | 0.803 | 7.48 ±0.55 | 33 | 10.50 ±1.50 | 3 | 7.77 ±0.56 | 36 | 0.195 | 0.449 | 0.271 | 0.439 |

| SMT total score | 6.54 ±0.63 | 34 | 6.33 ±0.88 | 3 | 6.53 ±0.58 | 37 | 0.781 | 5.14 ±0.54 | 33 | 10.00 ±1.53 | 4 | 5.53 ±0.55 | 37 | 0.158 | 0.549 | 0.451 | 0.241 |

Mean ± SEM of cognitive test scores stratified according to APOE genotype and HRT use. Significant P values for APOE genotype, HRT, and APOE*HRT are shown, using the ANCOVA model (MANCOVA for RBANS scores). p-HRT within each APOE genotype is calculated using the pairwise comparison of the estimated marginal mean with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparison. Age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR were used as covariates. HRT hormone replacement therapy, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, RBANS Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. FMT four mountain test, SMT supermarket trolley test. P-significant <0.05. a insignificant after FDR correction for multiple comparison. Bold: significant after FDR correction

Within APOE genotype group comparisons shows that HRT users have a higher RBANS total scale score (p= 0.045) and delayed memory index (p=0.002), only in APOE4 carriers (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Effect size analyses (Cohen’s d and parial eta squared calculations) show a large effect of HRT use on FMT (Cohen’s d=0.988, parial eta squared = 0.08), and SMT (Cohen’s d=1.2, parial eta squared = 0.11) test scores. This large effect was found only in APOE4 carriers. Similarly, a moderate-to-large effect of HRT on the left entorhinal volume was observed in APOE4 carriers (Cohen’s d = 0.63, parial eta squared = 0.04) (Supplemental Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Box plots showing the mean scores of RBANS total scale (left) and RBANS delayed memory index (right) in non-APOE4 versus APOE4 stratified according to HRT use. Pairwise comparison within each genotype group was carried out on the estimated marginal mean (within the MANCOVA model), after adjustment for age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR). Statistical results in the upper left corner show P values of APOE genotype, HRT, and APOE*HRT for RBANS total scale (left) and delayed memory index (right) using the MANCOVA model. Non-APOE4 n= 630 (no-HRT n=602, HRT n= 28), APOE4 n= 381 (no-HRT n=352, HRT n= 29)

Impact of APOE genotype and intake of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on MRI volumes of medial temporal lobe–specific regions in women

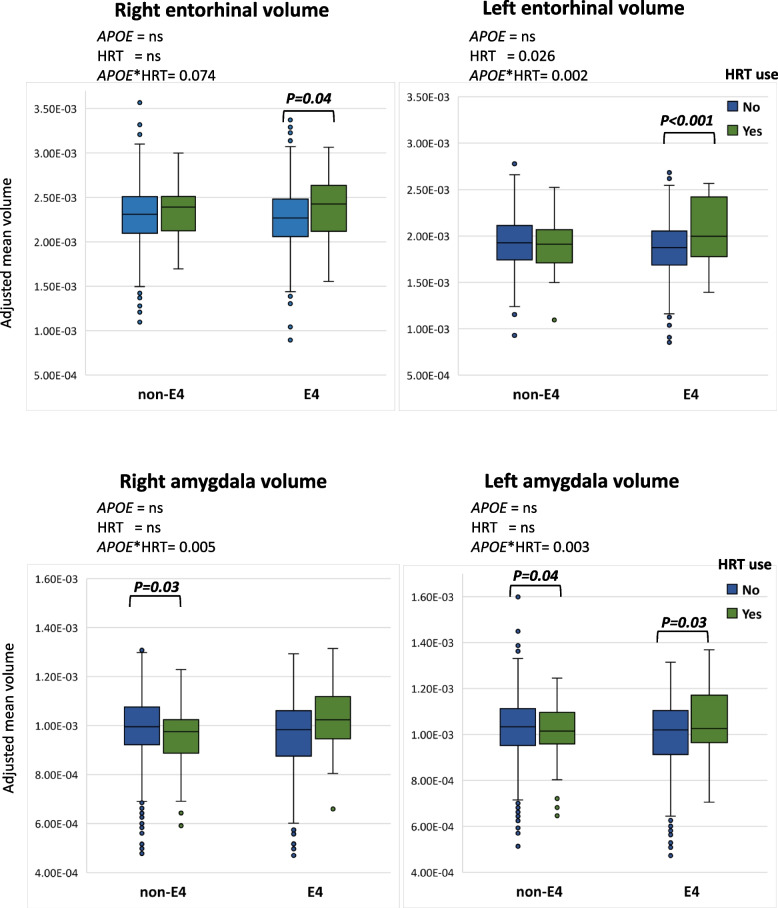

Entorhinal (left) and amygdala (left and right) volumes were larger in APOE4 HRT users compared to non-APOE4 and non-HRT users (P-interaction= 0.002, 0.003, and 0.005, respectively) (Table 3). Similar trends were observed for the right entorhinal volume (P-interaction= 0.074). HRT users had larger left entorhinal (P= 0.03) smaller anterior cingulate gyrus (right and left, p= 0.003 and 0.062) and larger left superior frontal gyrus volumes (p= 0.009) than non-users, independent of their APOE genotype (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3.

MRI volumes (mean±SEM) of medial temporal lobe–specific regions, according to APOE genotype status and HRT use

| Non-E4 | E4 | PAPOE | PHRT | PAPOE*HRT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-HRT (n=591–593) | HRT (n=48–50) | Total (n=639–643) | p-HRT | No-HRT (n=345–347) | HRT (n=29) | Total (n=374–376) | p-HRT | ||||

| Right hippocampus | 2360 ±13 | 2383 ±60 | 2362 ±13 | 0.367 | 2298 ±22 | 2384 ±37 | 2304 ±21 | 0.568 | 0.903 | 0.920 | 0.313 |

| Left hippocampus | 2284 ±13 | 2335 ±57 | 2288 ±12 | 0.690 | 2227 ±22 | 2333 ±43 | 2235 ±20 | 0.378 | 0.889 | 0.652 | 0.345 |

| Right parahippocampal | 2670 ±13 | 2735 ±50 | 2675 ±13 | 0.693 | 2624 ±20 | 2670 ±52 | 2628 ±19 | 0.370 | 0.430 | 0.660 | 0.966 |

| left parahippocampal | 2930 ±15 | 2971 ±46 | 2933 ±14 | 0.602 | 2840 ±20 | 2946 ±59 | 2849 ±19 | 0.801 | 0.587 | 0.698 | 0.302 |

| Right entorhinal | 2422 ±15 | 2444 ±53 | 2426 ±14 | 0.943 | 2378 ±22 | 2529 ±69 | 2373 ±22 | 0.040 a | 0.432 | 0.116 | 0.074 |

| Left entorhinal | 2026 ±12 | 2014 ±43 | 2029 ±12 | 0.426 | 1967 ±17 | 2172 ±55 | 1974 ±17 | <0.001 | 0.106 | 0.026 a | 0.002 |

| Right amygdala | 1031 ±07 | 987 ±21 | 1029 ±06 | 0.030a | 1002 ±11 | 1062 ±31 | 999 ±10 | 0.063 | 0.178 | 0.888 | 0.005 |

| Left amygdala | 1073 ±07 | 1038 ±23 | 1072 ±06 | 0.039a | 1039 ±10 | 1105 ±33 | 1038 ±10 | 0.031 a | 0.204 | 0.661 | 0.003 |

| Ventricular volume | 25444 ±814 | 22262 ±1725 | 25201 ±763 | 0.949 | 24244 ±825 | 24265 ±3507 | 24245 ±805 | 0.860 | 0.987 | 0.858 | 0.920 |

| Right cerebral WMV | 10951 ±106 | 11287 ±351 | 10977 ±102 | 0.658 | 10697 ±140 | 10584 ±510 | 10688 ±135 | 0.291 | 0.908 | 0.266 | 0.576 |

| Left cerebral WMV | 11052 ±120 | 11408 ±372 | 11080 ±114 | 0.764 | 10847 ±146 | 10581 ±467 | 10826 ±140 | 0.961 | 0.630 | 0.886 | 0.842 |

Mean (mm3) ±SEM of medial temporal lobe–specific MRI brain volumes, according to APOE4 genotype and HRT use. Significant P values for APOE genotype, HRT, and APOE*HRT are shown. MANCOVA model was used. p-HRT within each APOE genotype is calculated using the pairwise comparison of estimated marginal mean with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparison. Adjustment of the brain regions to the whole brain volume was carried out before statistical analysis. Age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR were used as covariates. p-significant <0.05. a insignificant after FDR correction for multiple comparison. Bold: significant after FDR correction. WMV white matter volume

Within APOE genotype group comparison shows that HRT users had larger entorhinal (right and left) and amygdala (left) volumes only in APOE4 carriers. In non-APOE4 carriers, amygdala volumes were smaller in HRT-users compared to non-users (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Boxplot showing the mean adjusted volumes of right and left entorhinal (up) and right and left amygdala volumes (down) in non-APOE4 versus APOE4 carriers, stratified according to HRT use. Pairwise comparison within each genotype group was carried out on the estimated marginal mean (within the MANCOVA model), after adjustment for age, years of education, marital status, handedness, and CDR. Volumes were adjusted to the whole brain volume: Statistical results in the upper left corner of the four brain regions show P values of APOE genotype, HRT, and APOE*HRT for each region using the MANCOVA model. Non-APOE4 n= 641 (no-HRT n=591, HRT n= 50), APOE4 n= 375 (no-HRT n=346, HRT n= 29)

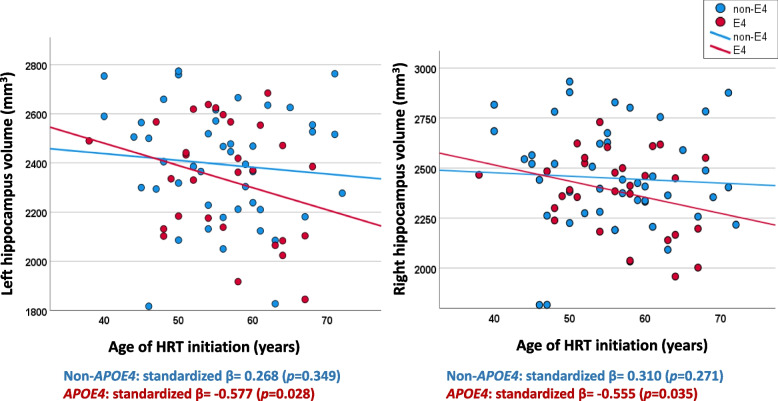

Earlier introduction of HRT was associated with larger hippocampal volumes only in APOE4 carriers

In APOE4 carriers, a significant negative association between age of HRT initiation and hippocampal volumes was observed. Early HRT introduction was associated with larger right hippocampal volume (standardized β= −0.555, p=0.035) and left hippocampal volume (standardized β= −0.577, p=0.028). This association was not evident in non-APOE4 carriers (Fig. 3). The association between right and left hippocampal volume and age of HRT initiation without stratification by APOE genotype was not significant (right hippocampus: standardized β= −0.086, p=0.601, left hippocampus: standardized β= −0.220, p=0.192). Associations of age of HRT initiation with entodhinal and amygdala volumes were not significant (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Association between right and left hippocampal volumes with age of HRT initiation. Multiple linear regression model showing the association between left and right hippocampal volumes and age of HRT initiation in non-APOE4 carriers (blue) and APOE4 carriers (red). Model-1 covariates: Age + years of education + handedness + marital status + CDR. Model-2: Model 1 covariates + age of HRT initiation (as an independent variable). Reported results are of model-2. APOE4 n= 27. non-APOE4 n= 46

Discussion

Higher AD risk and progression necessitates a more focused preventive approach in women. Results of the use of HRT for the prevention of cognitive decline have been inconsistent [14], or even harmful [15]. Here we demonstrate that APOE genotype and the age of HRT initiation are important modulators of the effect of HRT intervention on cognitive function and cognition-related brain volumes and can explain some of the discrepant outcomes. We report that APOE4 women are most responsive to HRT. APOE4 HRT users had larger entorhinal cortex and amygdala volumes compared to APOE4-non-HRT users and scored higher in the RBANS delayed memory index. We also importantly show that the earlier the age of HRT initiation, the larger the hippocampus volume, an association only observed in APOE4 women. To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates that HRT can have a beneficial effect on a range of cognitive function tests and cognition-related regional brain volumes in APOE4 women.

In non-HRT users, APOE4 carriers had a 3% lower delayed memory index score than non-APOE4 (Table 2). This result is consistent with literature showing that delayed and immediate memory are lower in at-risk APOE4 women [25, 43, 44]. HRT was found to influence cognition in an APOE-dependent manner. The use of HRT in APOE4 women was associated with a 10% higher delayed memory scores. A recent meta-analysis of 23 RCTs showed no impact of oral estrogen alone or CEE plus MPA on delayed memory scores, even at a younger age (<60 years), with an overall negative effect on global cognition. However, no sub-group analysis according to APOE genotype was carried out [17].

There is limited evidence of a positive effect of HRT on cognitive tests and cognition-related brain region in APOE4 carriers. In a sub-group analysis of the WHIMS RCT based on APOE genotype, a significant APOE × HRT interaction on the change in modified mini-mental status examination (3MSE) scores was observed, with the beneficial effect being exclusive to the homozygous APOE4 carriers [45]. However, the analysis did not expand to include other cognitive tests or MRI findings [45]. In a UK BIOBANK analysis (age=40–69 years), early HRT use (oral and transdermal) was associated with less evident brain aging in APOE4 carriers only [29]. In a small 2007 cross-sectional study, HRT use (n= 83) was associated with larger hippocampal volume in APOE4 (n=15) compared to APOE3 carriers [46].

Consistent with our cognitive data, APOE4 HRT users had 6–10% larger right and left entorhinal and right and left amygdala volumes. Both the entorhinal cortex and amygdala play an important role in cognition, with the entorhinal cortex being one of the first regions to be affected by AD-related pathological changes, even before the hippocampus [47], independent of aging-related pathology [48, 49]. Consequently, reduction in entorhinal volume was considered as a better predictor than hippocampus volumes in the conversion from MCI to AD [50]. In APOE4 carriers, smaller entorhinal volume in normal cognition [51] and with cognitive decline [52] have been observed. In the current study, no overall effect of APOE genotype on the entorhinal volume was evident. This is in line with previous studies which showed that at baseline, there were no differences in entorhinal volumes according to APOE genotype [53]; however, the rate of atrophy increases more with time in APOE4 carriers, specifically in females [54].

Here we show that APOE genotype status influences the response to HRT, with larger entorhinal volume observed in APOE4 carriers than non-carriers. The effect of HRT on cognition-related brain regions generally showed conflicting results [55, 56]. To our knowledge, only one study has showed that long-term HRT use was associated with larger hippocampus volume in APOE4 carriers compared to APOE3, with associated higher N-acetylaspartate neuronal metabolic marker. However, no changes in cognitive test scores were observed [46]. In addition, in EPAD we also observed that HRT use (for an average of 8 years) is associated with a differential effect on the amygdala with higher volumes only in APOE4 carriers.

Large effect of HRT use on FMT (Cohen’s d=0.988), and SMT (Cohen’s d=1.2) test scores were observed. These large effects were found only in APOE4 carriers. Similarly, a moderate-to-large effect of HRT on the left entorhinal volume was observed in APOE4 carriers (cohen d = 0.63). With the entorhinal cortex playing an important role in spatial navigation [57], and is affected in the early stages of AD pathology [47], one can deduce that the larger entorhinal volume could contribute to higher FMT and SMT scores in APOE4 HRT-users. Further research in human and experimental models are needed to confirm the strength of the association and causal relationships.

The amygdala plays an important role in cognition and emotion, which are inextricably linked [58]. In a recent meta-analysis, the volume of the hippocampus, parahippocampus, and amygdala was smaller in 2262 MCI patients compared to controls, [59]. Indeed, distinct amygdala radiomic features were able to distinguish between 97 AD patients, 53 MCI patients, and 45 normal controls, showing that microstructural changes in the amygdala can occur early during the course of AD [60]. The difference in amygdala volumes as a function of APOE genotype and HRT use is of interest, with a trend towards smaller volume in non-APOE4 HRT users. One could speculate that this might be due to the amygdala, as compared to other brain regions, being enriched in estrogen receptor (ER) alpha (ERα) but not ERβ [61]. This difference in enrichment may affect the structural and perfusion differences within this region [62]. This requires further future investigation.

An effect on cerebral blood flow (CBF) may explain the large entorhinal and amygdala volumes in APOE4 HRT users. Previous studies show that APOE4 carriers have higher CBF than non-carriers [63, 64]. This observation was seen at a younger age, with lower CBF observed in older age [65, 66]. HRT use in early menopause has been shown to improve peripheral vascular function [67], and in a recent study, estrogen use was associated with reduced cerebral vessels’ smooth muscle tone in a menopausal mouse model [68]. It is possible that a HRT-mediated effect on CBF in APOE4 could in part underpin the impact on brain volume and associated improved memory, which is worthy of future investigation.

Another possible explanation for the select benefits in APOE4 carriers is the complex interaction between APOE4 genotype and age with neurophysiology and neuropathology. Although carrying the APOE4 genotype increases the risk for cognitive decline and AD in older adults, select studies suggest that APOE4 can be associated with enhanced cognitive performance at a younger age [69–71]. While the differential penetrance of APOE4 by age is not well understood, it may be partly due to dysfunctional DHA metabolism [72, 73], β-amyloid clearance [74], or higher neuroinflammation [75] in older adults which all contribute to accelerated neuronal damage and loss, which may be mitigated by HRT use.

Besides APOE genotype, timing of HRT initiation is gaining attention as a mediator of the cognitive impact of HRT use, leading to the ‘critical window’ hypothesis [76]. This hypothesis suggests that the neuroprotective effects of HRT are only evident when it is introduced during the menopausal transition or early post-menopausal period [27]. Indeed, in the WHIMS RCT (age > 65 years), the use of oral CEE alone or CEE plus progestogen for up to 8 years was associated with 76% increased risk of dementia [16], and reduction in the hippocampus and total brain volumes [77]. However, there was no impact of HRT intervention on cognition in a younger subgroup (age 50-55 years, WHIMSY) (age 50–55) [78, 79]. Similarly, an observational study showed that the introduction of HRT in midlife (age 48.7 years) was associated with a 26% reduced risk of dementia compared to 48% increased risk when HRT was initiated in later life (age 76 years) [80]. In a recent meta-analysis in healthy post-menopausal women, HRT use was associated with reduced global cognition, which was less evident for those younger than 60 years old [17]. Our results are consistent with these findings, with our findings specifically observing that this impact of early initiation is specific to APOE4 carriers. To our knowledge, the only study that looked at APOE*age of HRT initiation was carried out by De lange et al. [29], where less brain aging (calculated by machine learning) was associated with earlier HRT initiation in APOE4 carriers.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional analysis precluding the establishment of causal relationship. Data about age of menopause, or if there was a gap between age at menopause and the start of HRT is not available, which would allow further granularity in our analysis. Information regarding the type of estrogen in the ERT formulation, and for example the use of conjugated estrogen versus estradiol was not available for some of the participants. In addition, doses of HRT were not available for some prescriptions. A further limitation is the small number of participants in the APOE4 HRT user’s subgroup (n= 29–31) which did not allow for stratification according to the use of estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestogens preparation. The neurogenic effects of progestogen preparations are still controversial and require further investigations, with the available studies being mostly pre-clinical or carried out on small sample sizes [81–83].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we show that HRT had more cognitive benefits in APOE4 carriers. APOE4 women on HRT performed better in delayed memory tasks and had large entorhinal and amygdala volumes than non-HRT users. Earlier HRT initiation was associated with larger hippocampus volume, an effect only seen in APOE4 carriers. These results highlight the importance of personalized medicine in the prevention of AD. This work provides the rationale for the conduct of an RCT which examines the impact of early (perimenopause or early post-menopause) HRT introduction on cognition and brain atrophy according to APOE4 carrier status to confirm the observed associations. Finally, the findings highlight the heterogenous nature of AD with the effectiveness of HRT in APOE4 carriers only, indicating differences in the mechanistic basis of cognitive decline and pathology relative to non-carriers.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental table 1. Brain structural outcomes (MRI), volumes (mean±SEM) in mm3, according to HRT use and APOE4 genotype status.

Additional file 2: Supplemental table 2. Effect sizes for the use of HRT on select cognitive test scores and regional brain volumes according to APOE genotype.

Additional file 3: Supplemental figure 1. Association between entorhinal (up) and amygdala volumes (down) with age of HRT initiation. Multiple linear regression model showing the association between entorhinal (left and right) and amygdala (left and right) volumes with age of HRT initiation in non-APOE4 carriers (blue) and APOE4 carriers (red). Model-1 covariates: Age + years of education + handedness + marital status + CDR. Model-2: Model 1 covariates + age of HRT initiation (as an independent variable). Reported results are of model-2. APOE4 n= 27. non-APOE4 n= 46.

Authors’ contributions

RS and AM designed the current study. RS conducted the statistical analysis, analyzed the data, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript. MH critically reviewed the manuscript and gave valuable feedback on shaping the results and data presentation. CR is the chief investigator of the EPAD study, he reviewed and gave feedback on the manuscript. AM: supervised the overall direction and planning of the current study, and comprehensively edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of the Medical Research Council (MRC, UK), NuBrain Consortium (MR/T001852/1).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset is publicly available and can be accessed from the Workbench of the Alzheimer’s Disease Data Initiative (ADDI) portal website: https://portal.addi.ad-datainitiative.org/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a cross-sectional analysis of the online datasets of the EPAD LCS study. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee or other relevant ethical review board for written approval as required by local laws and regulations. A copy of approval is required by the University of Edinburgh as Sponsor before the study commences at each site. The study is designed and conducted in accordance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and with the ethical principles as proclaimed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants are required to provide written informed consent prior to participation in any research activities laid out in the EPAD LCS protocol. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.2021 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(3):327–406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nichols E, Szoeke CEI, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):88–106. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105–ee25. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine K, Laws KR, Gale TM, Kondel TK. Greater cognitive deterioration in women than men with Alzheimer's disease: a meta analysis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34(9):989–998. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.712676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laws KR, Irvine K, Gale TM. Sex differences in cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(1):54–65. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontifex M, Vauzour D, Minihane AM. The effect of APOE genotype on Alzheimer's disease risk is influenced by sex and docosahexaenoic acid status. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;69:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu D, Montagne A, Zhao Z. Alzheimer’s pathogenic mechanisms and underlying sex difference. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(11):4907–4920. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03830-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui J, Shen Y, Li R. Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during aging: from periphery to brain. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(3):197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson VW, St John JA, Hodis HN, McCleary CA, Stanczyk FZ, Shoupe D, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: A randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87(7):699-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.McCarthy M, Raval AP. The peri-menopause in a woman’s life: a systemic inflammatory phase that enables later neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):317. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01998-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Mayer LS, Steffens DC, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease in older women: the Cache County Study. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2123–2129. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, Teutsch SM, Allan JD. Postmenopausal Hormone Replacement TherapyScientific Review. JAMA. 2002;288(7):872–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, van Dyck CH, Sano M, Doody R, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1007–1015. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grady D, Yaffe K, Kristof M, Lin F, Richards C, Barrett-Connor E. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on cognitive function: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Am J Med. 2002;113(7):543–548. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2651–2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, et al. Conjugated Equine Estrogens and Incidence of Probable Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Postmenopausal WomenWomen's Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2947–2958. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou HH, Yu Z, Luo L, Xie F, Wang Y, Wan Z. The effect of hormone replacement therapy on cognitive function in healthy postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis of 23 randomized controlled trials. Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21(6):926–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhao N, Ren Y, Yamazaki Y, Qiao W, Li F, Felton LM, et al. Alzheimer’s Risk Factors Age, APOE Genotype, and Sex Drive Distinct Molecular Pathways. Neuron. 2020;106(5):727–42.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunzler J, Youmans KL, Yu C, Ladu MJ, Tai LM. APOE modulates the effect of estrogen therapy on Aβ accumulation EFAD-Tg mice. Neurosci Lett. 2014;560:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349–1356. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payami H, Montee KR, Kaye JA, Bird TD, Yu CE, Wijsman EM, et al. Alzheimer's disease, apolipoprotein E4, and gender. JAMA. 1994;271(17):1316–1317. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510410028015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortensen EL, Høgh P. A gender difference in the association between APOE genotype and age-related cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57(1):89–95. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beydoun MA, Boueiz A, Abougergi MS, Kitner-Triolo MH, Beydoun HA, Resnick SM, et al. Sex differences in the association of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele with incidence of dementia, cognitive impairment, and decline. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(4):720–31.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, Beekly D, Kuzma A, Gangadharan P, et al. Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Sex Risk Factors for Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1178–1189. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobel Z, Isenberg AL, Raghupathy D, Mack W, Pa J, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I et al. APOE ɛ4 Gene Dose and Sex Effects on Alzheimer’s Disease MRI Biomarkers in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;71:647–658. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maki PM. Critical window hypothesis of hormone therapy and cognition: a scientific update on clinical studies. Menopause. 2013;20(6):695–709. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182960cf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher DW, Bennett DA, Dong H. Sexual dimorphism in predisposition to Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;70:308–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pike CJ. Sex and the development of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1-2):671–680. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Lange AG, Barth C, Kaufmann T, Maximov II, van der Meer D, Agartz I, et al. Women's brain aging: Effects of sex-hormone exposure, pregnancies, and genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(18):5141–5150. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritchie CW, Molinuevo JL, Truyen L, Satlin A, Van der Geyten S, Lovestone S. Development of interventions for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer's dementia: the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia (EPAD) project. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon A, Kivipelto M, Molinuevo JL, Tom B, Ritchie CW. European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia Longitudinal Cohort Study (EPAD LCS): study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;8(12):e021017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan TK. Chapter 2 - Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. In: Khan TK, editor. Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease: Academic Press; 2016. p. 27–48.

- 33.Ritchie K, Ropacki M, Albala B, Harrison J, Kaye J, Kramer J, et al. Recommended cognitive outcomes in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Consensus statement from the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia project. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(2):186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer JH, Mungas D, Possin KL, Rankin KP, Boxer AL, Rosen HJ, et al. NIH EXAMINER: conceptualization and development of an executive function battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(1):11–19. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310–319. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritchie CW, Muniz-Terrera G, Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Tom B, Molinuevo JL. The European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia (EPAD) Longitudinal Cohort Study: Baseline Data Release V500.0. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020;7(1):8–13. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karantzoulis S, Novitski J, Gold M, Randolph C. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Utility in detection and characterization of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28(8):837–844. doi: 10.1093/arclin/act057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moodley K, Minati L, Contarino V, Prioni S, Wood R, Cooper R, et al. Diagnostic differentiation of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease using a hippocampus-dependent test of spatial memory. Hippocampus. 2015;25(8):939–951. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu S, Wong S, Hodges JR, Irish M, Piguet O, Hornberger M. Lost in spatial translation - A novel tool to objectively assess spatial disorientation in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Cortex. 2015;67:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingala S, De Boer C, Masselink LA, Vergari I, Lorenzini L, Blennow K, et al. Application of the ATN classification scheme in a population without dementia: Findings from the EPAD cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(7):1189–1204. doi: 10.1002/alz.12292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raslau FD, Mark IT, Klein AP, Ulmer JL, Mathews V, Mark LP. Memory part 2: the role of the medial temporal lobe. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(5):846–849. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences: Routledge; 2013.

- 43.O'Bryant SE, Barber RC, Philips N, Johnson LA, Hall JR, Subasinghe K, et al. The Link between APOE4 Presence and Neuropsychological Test Performance among Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites of the Multiethnic Health & Aging Brain Study - Health Disparities Cohort. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2022;51(1):26–31. doi: 10.1159/000521898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anstey KJ, Peters R, Mortby ME, Kiely KM, Eramudugolla R, Cherbuin N, et al. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20–76 years. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7710. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahoney ER, Dumitrescu L, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Keene CD, Corrada MMM, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy has beneficial effects on cognitive trajectories among homozygous carriers of the APOE-ε4 allele. Alzheimers Dementia. 2020;16(S5):e041482. doi: 10.1002/alz.041482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yue Y, Hu L, Tian QJ, Jiang JM, Dong YL, Jin ZY, et al. Effects of long-term, low-dose sex hormone replacement therapy on hippocampus and cognition of postmenopausal women of different apoE genotypes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28(8):1129–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leandrou S, Petroudi S, Kyriacou PA, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Pattichis CS. Quantitative MRI Brain Studies in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Methodological Review. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2018;11:97–111. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2018.2796598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Fennema-Notestine C, McEvoy LK, Hagler DJ, Holland D, et al. One-year brain atrophy evident in healthy aging. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15223–15231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3252-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou M, Zhang F, Zhao L, Qian J, Dong C. Entorhinal cortex: a good biomarker of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27(2):185–195. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickerson BC, Goncharova I, Sullivan MP, Forchetti C, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, et al. MRI-derived entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy in incipient and very mild Alzheimer’s disease☆☆This research was supported by grants P01 AG09466 and P30 AG10161 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22(5):747–754. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burggren AC, Zeineh MM, Ekstrom AD, Braskie MN, Thompson PM, Small GW, et al. Reduced cortical thickness in hippocampal subregions among cognitively normal apolipoprotein E e4 carriers. Neuroimage. 2008;41(4):1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hostage CA, Choudhury KR, Murali Doraiswamy P, Petrella JR. Mapping the effect of the apolipoprotein E genotype on 4-year atrophy rates in an Alzheimer disease-related brain network. Radiology. 2014;271(1):211–219. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spampinato MV, Rumboldt Z, Hosker RJ, Mintzer JE. Apolipoprotein E and gray matter volume loss in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Radiology. 2011;258(3):843–852. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spampinato MV, Langdon BR, Patrick KE, Parker RO, Collins H, Pravata’ E, et al. Gender, apolipoprotein E genotype, and mesial temporal atrophy: 2-year follow-up in patients with stable mild cognitive impairment and with progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroradiology. 2016;58(11):1143–1151. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1740-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kantarci K, Tosakulwong N, Lesnick TG, Zuk SM, Gunter JL, Gleason CE, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on brain structure: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2016;87(9):887–896. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA, Hirsch C, Stefanick ML, Murray AM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and regional brain volumes: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology. 2009;72(2):135–142. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339037.76336.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pilly PK, Grossberg S. How do spatial learning and memory occur in the brain? Coordinated learning of entorhinal grid cells and hippocampal place cells. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012;24(5):1031–1054. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quadt L, Critchley H, Nagai Y. Cognition, emotion, and the central autonomic network. Auton Neurosci. 2022;238:102948. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2022.102948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raine PJ, Rao H. Volume, density, and thickness brain abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment: an ALE meta-analysis controlling for age and education. Brain Imaging Behav. 2022;16(5):2335–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Feng Q, Niu J, Wang L, Pang P, Wang M, Liao Z, et al. Comprehensive classification models based on amygdala radiomic features for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021;15(5):2377–2386. doi: 10.1007/s11682-020-00434-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hwang WJ, Lee TY, Kim NS, Kwon JS. The Role of Estrogen Receptors and Their Signaling across Psychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(1):373. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hays CC, Zlatar ZZ, Meloy MJ, Bondi MW, Gilbert PE, Liu T, et al. Interaction of APOE, cerebral blood flow, and cortical thickness in the entorhinal cortex predicts memory decline. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):369–382. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00245-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dounavi ME, Low A, McKiernan EF, Mak E, Muniz-Terrera G, Ritchie K, et al. Evidence of cerebral hemodynamic dysregulation in middle-aged APOE ε4 carriers: The PREVENT-Dementia study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(11):2844–2855. doi: 10.1177/0271678X211020863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thambisetty M, Beason-Held L, An Y, Kraut MA, Resnick SM. APOE epsilon4 genotype and longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in normal aging. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(1):93–98. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wierenga CE, Clark LR, Dev SI, Shin DD, Jurick SM, Rissman RA, et al. Interaction of age and APOE genotype on cerebral blood flow at rest. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(4):921–935. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sherwood A, Bower JK, McFetridge-Durdle J, Blumenthal JA, Newby LK, Hinderliter AL. Age moderates the short-term effects of transdermal 17beta-estradiol on endothelium-dependent vascular function in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(8):1782–1787. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blackwell JA, Silva JF, Louis EM, Savu A, Largent-Milnes TM, Brooks HL, et al. Cerebral arteriolar and neurovascular dysfunction after chemically-induced menopause in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;323(5):H845–h60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Mondadori CR, de Quervain DJ, Buchmann A, Mustovic H, Wollmer MA, Schmidt CF, et al. Better memory and neural efficiency in young apolipoprotein E epsilon4 carriers. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(8):1934–1947. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rusted JM, Evans SL, King SL, Dowell N, Tabet N, Tofts PS. APOE e4 polymorphism in young adults is associated with improved attention and indexed by distinct neural signatures. NeuroImage. 2013;65:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mitter SS, Oriá RB, Kvalsund MP, Pamplona P, Joventino ES, Mota RM, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 influences growth and cognitive responses to micronutrient supplementation in shantytown children from northeast Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67(1):11–18. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(01)03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yassine HN, Rawat V, Mack WJ, Quinn JF, Yurko-Mauro K, Bailey-Hall E, et al. The effect of APOE genotype on the delivery of DHA to cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8:25. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0194-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martinsen A, Tejera N, Vauzour D, Harden G, Dick J, Shinde S, et al. Altered SPMs and age-associated decrease in brain DHA in APOE4 female mice. FASEB J. 2019;33(9):10315–10326. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900423R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Park DC. Beta-amyloid deposition and the aging brain. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(4):436–450. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calsolaro V, Edison P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(6):719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sherwin BB. The critical period hypothesis: can it explain discrepancies in the oestrogen-cognition literature? J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19(2):77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Espeland MA, Tindle HA, Bushnell CA, Jaramillo SA, Kuller LH, Margolis KL, et al. Brain volumes, cognitive impairment, and conjugated equine estrogens. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(12):1243–1250. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, Manson JE, Brown CM, LeBlanc ES, et al. Long-Term Effects on Cognitive Function of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy Prescribed to Women Aged 50 to 55 Years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(15):1429–1436. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Manson JE, Goveas JS, Shumaker SA, Hayden KM, et al. Long-term Effects on Cognitive Trajectories of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy in Two Age Groups. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(6):838–845. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Zhou J, Yaffe K. Timing of hormone therapy and dementia: the critical window theory revisited. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):163–169. doi: 10.1002/ana.22239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vinogradova Y, Dening T, Hippisley-Cox J, Taylor L, Moore M, Coupland C. Use of menopausal hormone therapy and risk of dementia: nested case-control studies using QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2021;374:n2182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brinton RD, Yao J, Yin F, Mack WJ, Cadenas E. Perimenopause as a neurological transition state. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(7):393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao L, Morgan TE, Mao Z, Lin S, Cadenas E, Finch CE, et al. Continuous versus cyclic progesterone exposure differentially regulates hippocampal gene expression and functional profiles. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplemental table 1. Brain structural outcomes (MRI), volumes (mean±SEM) in mm3, according to HRT use and APOE4 genotype status.

Additional file 2: Supplemental table 2. Effect sizes for the use of HRT on select cognitive test scores and regional brain volumes according to APOE genotype.

Additional file 3: Supplemental figure 1. Association between entorhinal (up) and amygdala volumes (down) with age of HRT initiation. Multiple linear regression model showing the association between entorhinal (left and right) and amygdala (left and right) volumes with age of HRT initiation in non-APOE4 carriers (blue) and APOE4 carriers (red). Model-1 covariates: Age + years of education + handedness + marital status + CDR. Model-2: Model 1 covariates + age of HRT initiation (as an independent variable). Reported results are of model-2. APOE4 n= 27. non-APOE4 n= 46.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is publicly available and can be accessed from the Workbench of the Alzheimer’s Disease Data Initiative (ADDI) portal website: https://portal.addi.ad-datainitiative.org/.