Abstract

We investigate the impact of macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty on G7 financial markets around COVID-19 pandemic using two real-time, real-activity indexes recently constructed by Scotti (2016). We applies the wavelet analysis to detect the response of the stock markets to the macroeconomic surprise and an uncertainty indexes and then we use NARDL model to examine the asymmetric effect of the news surprise and uncertainty on the equity markets. We conduct our empirical analysis with the daily data from January, 2014 to September, 2020. Our findings indicate that G7 stock markets are sensitive to the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty and the effect is more pronounced at the long term than the short term. Moreover, we show that the COVID-19 crisis supports the relationship between the macroeconomic indexes and the stock prices. The results are useful for investment decision-making for the investors on the G7 stock indices at different investment horizons.

Keywords: New financial risks, COVID-19, Macroeconomic surprise, Uncertainty, NARDL

1. Introduction

Macroeconomic indicators are crucial for any change in the economic cycle, policy making and investment decisions of a country. Any abrupt change in these indicators influences the economy as well as the performance of the financial market in various ways. Several studies examine the relationships between macroeconomic variables and stock prices (Ratanapakorn and Sharma, 2007, Humpe and Macmillan, 2009, Antonakakis et al., 2017, Bhuiyan and Chowdhury, 2020, Chang et al., 2020, Humpe and McMillan, 2020, Parab and Reddy, 2020). Other studies investigate the effect of macroeconomic news on financial stock markets (Aharon et al., 2022, Akron et al., 2022, Rangel, 2011, Belgacem et al., 2015, Cakan et al., 2015, Balcilar et al., 2017, Esin and Gupta, 2017, Ayadi et al., 2020, Banerjee et al., 2020; Corbet et al., 2020; Hussain et al., 2020; Queku et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). Besides, two recently developed real-time, real-activity indexes describe and measure the changes in macroeconomic news surprises and uncertainty. These indexes are based on macroeconomic indicators (Scotti, 2016) and are used to investigate the sensitivity of stock prices to the underlying state of the economy (see Al-Khazali et al., 2018; Bahloul and Gupta, 2018).

Since the beginning of 2020, the world has experienced a new economic and financial crisis originating from the COVID-19, which has harshly affected the economic cycle as well as financial markets (Amar et al., 2021, Amar et al., 2021; Bai et al., 2020; Baker et al., 2020a, Baker et al., 2020b; Harjoto et al., 2020; Sharif et al., 2020; Goodell and Huynh, 2020; Schell et al., 2020; Yousfi et al., 2021a, Yousfi et al., 2021b; Zhang et al., 2020; Ambros et al., 2021; McKibbin and Fernando, 2021; Huynh et al., 2021). Against the backdrop of the economic and financial consequences of this crisis, we expect the pandemic’s repercussions to strengthen the linkage between the macroeconomic state and the stock price behaviour. However, the growing literature about the financial consequences of COVID-19 crisis on economic conditions and financial markets is mostly limited to the linkage between economic factors and stock markets ignoring the role of news announcements in deriving stock prices. To the best of our knowledge, none or few of the existing literature have investigated the influence of macroeconomic news on financial markets under the effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

The aim of the paper is to examine the symmetric and asymmetric relations between the G7 financial market indices and the macroeconomic news surprise and uncertainty over the period from January 2014 to September 2020 using the wavelet approach and the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) framework. Accordingly, we check the short and long-run responses of the individual G7 stock market returns to the daily change in the macroeconomic news surprise and uncertainty indexes developed by Scotti (2016).

Our study contributes to the crisis effects on stock market literature in many ways. First, while earlier studies limited to the COVID-19 crisis effects on the association between macroeconomic indicators and equity markets, we extend it to investigate influence of the change of macroeconomic news announcement surprises and economic uncertainty on stock markets’ behavior considering the role of COVID-19 pandemic on the interaction. Second, our investigation covers different horizons of relationships over the short and long terms using a time–frequency framework. Hence, one of the distinctive features of our paper is the employment of wavelet analysis to explore the linkage between news surprises and financial markets. Moreover, we focus on the short and long-terms asymmetrical effects between the selected stock markets and macroeconomic condition samples. Finally, our study is based on an interesting dataset of macroeconomic news surprise and uncertainty indexes constructed from a set of economic indicators. Those indexes are developed based on the agent expectations, the macroeconomic surprise index measures the degree of ex-post optimism or pessimism about the state of the economy, whereas, the economic uncertainty index measures the uncertainty related to the current economic condition. We use the change on those indexes to identify the macroeconomic risk and their influence on the equity markets.Our findings show that equity markets react significantly to a change in the two macroeconomic indexes. The reaction is more pronounced during the pandemic period for most developed countries, establishing the role of the pandemic in the connectedness between the real and financial spheres. In fact, the results indicate that the symmetric as well as the asymmetric relationships between most the stock indices and the macroeconomic conditions are more robust over the long-run than the short-run. Our findings show the importance of the role of macroeconomic surprises as well as uncertainties for major developed economies in driving the G7 market indices, especially during the turbulent period of the COVID-19 crisis. Overall, this paper conclude that the COVID-19 crisis acts as a systematic risk and contributes to the change of macroeconomic conditions leading to raising of macroeconomic shock. This risk affects the stock market performance. Such findings suggest that the investors should manage the macro risks increased by macroeconomic factor changes due to the pandemic effects.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the related literature. Section 3 describes the data and the empirical methodology. Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical results. Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature review

Previous studies provide evidence suggesting that the macroeconomic state affects financial asset prices. Empirical literature posits that the arrival of macroeconomic news has an impact on asset returns and volatility. Nowak et al. (2011) investigate the reaction of the emerging bond market returns and volatilities to local macroeconomic announcements and announcements from the US and Germany. The authors find that the returns and volatility are influenced by surprises from global, regional and local macroeconomic announcements. Harju and Hussain (2011) investigate the effect of US macroeconomic surprises on major European stock markets: France, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. They show that US macroeconomic surprises only appear to have a significant influence on stocks’ volatilities. Cakan et al. (2015) use the GJR-GARCH model and 12 emerging stock markets to analyse the impact of US macroeconomic surprises on stock volatilities. They find that five stock volatilities increase with bad news on US inflation and four stock volatilities increase with bad news on US unemployment.

Meanwhile, the volatility in eight countries declines with good news on the employment situation of the United States, which means that the US employment situation and economic growth have an impact on several emerging equity markets and that positive surprises make several emerging stock markets less volatile. On a similar note, Esin and Gupta (2017) examine the effect of US macroeconomic declaration shocks on South African stock market volatility. They show that the turbulence of the South African stock market is not affected by negative reporting regarding US inflation, but that positive news seems to boost it. Unexpected increases in the US rate of unemployment make South African returns more hazardous, whereas unexpected decreases in the US unemployment figures make South African returns less problematic.

According to Hussain et al. (2020), the intraday returns and volatility of Brazil and Mexico's stock markets in reaction to US macroeconomic media releases during the times of the US and European economic turmoil have been studied. To summarise, these results show that the market indices' returns are more delicate to economic and financial headlines than are their volatilities; the uncertainty of these indices is acutely susceptible to US news surprises, while a stronger reaction to surprises in Brazil's economy is observed in the Brazilian index. Although other macroeconomic variables have also shown an impact on volatility, it appears that the FOMC's interest rate choices have the most impact. Similarly, Corbet et al. (2020) explored the relation between news reporting and bitcoin returns by constructing an opinion index using news items that follow the declarations of four economic factors: GDP, unemployment, and Consumer Price Index (CPI), and household items. They suggest that the still-emerging cryptocurrency, bitcoin, is further evolving as a result of interactions with economic news. Bitcoin's price tends to decline when there is more positive news after statements on unemployment and consumer durables, while there is a positive correlation between an increase in the number of negative stories accompanying these statements and a rise in the price of bitcoin. On the other hand, it has been discovered that the news about the GDP and CPI does not have any major links with bitcoin.

When it comes to Indian index futures returns, Banerjee et al. (2020) investigate the impact of macroeconomic event shocks. They claim that macroeconomic factors shocks have a major impact on return volatility and market cap and that the reaction of indices futures markets to macroeconomic events is rapid and substantial. Evidence suggests that the impact of macroeconomic events on index futures trading is not always equal. Queku et al. (2020) use Toda, Yamamoto, and Granger's no-causality method and monthly time series data from 1996 to 2018 to investigate the causal linkages between share prices and variations in macroeconomic indicators (MEI) in Ghana. They indicate bidirectional causation between MEI (GDP, interest rate, and money supply) and share prices and a linear link flowing from MEI (currency rate and overseas direct investment) to share prices.

Another corpus of studies focuses on developing a new measure of macroeconomic uncertainty. There is no fundamental indicator of economic unpredictability since volatility has been employed as a measure of uncertainty, as per Scotti (2016). Using the VXO index as an example, Bloom (2009) employs uncertainty as a measure. the variance risk premiums and stock market volatility, all of which are decomposed by Bekaert et al. (2013). Survey expectation data are used by Bachmann et al. (2013) to build time-varying business-level uncertainty. Using data from the IFO Business Climate Surveys and the Business Outlook Surveys, they estimate the level of uncertainty in Germany and the United States. For their study, Leduc and Liu (2016) used data from Thomson Reuters in the US and the Industrial Trends Survey in the UK to gauge the level of perceived uncertainty among consumers and businesses. Baker et al. (2016) developed a measure of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) depending on the frequency of news article links to the size of income tax code requirements set to expire in coming periods, dissent among economic forecasting models about policy-relevant factors, and economic unpredictability. The recent literature shows increasing interest in the use of the economic policy uncertainty (EPU) measure to investigate the effect on asset prices (see Das et al., 2019; He et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Kannadhasan and Das, 2020; Sharif et al., 2020). Li et al. (2020) suggest that EPU can lead to high stock market volatility, which helps predict volatility and can negatively affect the stock returns.

For the United States and other countries, Scotti (2016) has created and constructed two indices: a macroeconomic shock index, which quantifies the discrepancy from general agreement preconceptions and represents how positive or negative outcomes representatives are about the economic system. The second is an uncertainty index showing how much agents are uncertain about the current economic situation in the US, Canada, Europe, the UK and Japan. These two indexes are used in Bahloul and Gupta’s (2018) recent study to investigate the impact of Brent crude oil futures and West Texas Intermediate returns and volatility using the GARCH (1,1) model. They find strong evidence of macroeconomic surprises and uncertainty effects, especially for volatility rather than returns. Furthermore, Al-Khazali et al. (2018) examine the response of gold and bitcoin returns and volatility to positive and negative macroeconomic news surprises originating from major developed economies using the GARCH(1,1) and E-GARCH (1,1) models. The results show an asymmetric effect and provide evidence that gold is different from bitcoin. Gold’s returns and volatility react systematically to macroeconomic surprises in a manner consistent with its traditional role as a safe haven asset, whereas bitcoin’s returns and volatility are mostly not sensitive in a similar manner.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data

In this study, we investigate the effect of macroeconomic surprises and uncertainty on the G7 stock market prices. To achieve our objective, we use two real-time, real-activity indexes for the US, Canada, the euro area, the UK and Japan, proposed by Scotti (2016), which are available for download at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1803dSciJEV_UP1c-XQYv4wDmXULLnpUQ/view. We extract the daily prices from Bloomberg to compute the returns of the stock market indices of the G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US) as the difference in the logarithm prices. The two indexes are a news surprise index, which measures the extent of optimism and pessimism of agents about the economic condition of the economy, and a real-activity uncertainty index, which measures uncertainty pertains to the situation of the economy. These indexes are developed for five countries – the US, Canada, the euro area, the UK and Japan – and cover five economic indicators for each country, except the US, which has six variables.

The selection of indicators by Scotti (2016) is guided by several factors. He employs a collection of factors that are widely used by governments, businesses, and central banks as a real-time indicator of the economy's condition. Quarterly real GDP, monthly industrial production (IP), employees on non-agricultural payrolls (or unemployment rate), monthly retail sales, and a survey of the manufacturing sector make up the collection of variables used in this analysis The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) personal income is an extra statistic for the United States. If there is no new data to update these indices, they are identical by construction to their values from the previous day, as evidenced by the fact that the macroeconomic shock and uncertainty indexes are produced daily and updated whenever fresh information becomes available (2016). A modification in these indexes is therefore seen as a sign that new evidence has been made available. If the macroeconomic shock index goes up, it implies that the economy is getting great than predicted, and vice versa, but if the uncertainty index goes up, it shows that individuals are more unclear about the present economy's status. We conduct our empirical analysis with the daily data from January 2014 to September 2020. Notably, our sample period covers the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

Fig. 1 describes the time series prices and squared returns of the G7 stock markets. Notice that each market experiences a significant decrease in prices and high volatility clustering at the beginning of 2020, which can be explained as its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Time series prices and squared returns of the G7 stock markets.

The summary statistics of our sample stock markets are presented in Table 1. The G7 markets exhibit a positive mean of returns, but it is very weak, close to 0, during the sample period, except for the UK market, which presents a negative mean value. Japan’s market has a lower standard deviation, while the Italian and US stock indices exhibit the highest. The Jarque–Bera test shows that the G7 equities are far from being normally distributed, and the ARCH LM test explores the existence of a high ARCH effect, which can be explained by a case of robust clustering, as we can see in Fig. 1. Based on the ADF test, all series are stationary in the first difference. 1

Table 1.

Statistical properties for dailly data.

| S&P500 | S&P/TSX60 | CAC40 | DAX | FTSE MIB | FTSE 100 | NIKKEI 225 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.038714 | 0.011532 | 0.007969 | 0.019198 | 0.000359 | -0.008615 | 0.024427 |

| Median | 0.064258 | 0.072314 | 0.076189 | 0.077265 | 0.059884 | 0.044698 | 0.070017 |

| Maximum | 8.968323 | 11.29453 | 8.056082 | 10.41429 | 8.549457 | 8.666807 | 7.731376 |

| Minimum | -12.76522 | -13.17580 | -13.09835 | -13.05486 | -18.54114 | -11.51243 | -8.252933 |

| S.D | 1.183512 | 1.068050 | 1.300638 | 1.342784 | 1.598076 | 1.097171 | 1.348218 |

| Skewness | -1.282447 | -2.038857 | -1.253516 | -0.810275 | -1.723529 | -1.055544 | -0.234596 |

| Kurtosis | 24.58913 | 46.70078 | 14.66150 | 13.71833 | 21.02616 | 16.81878 | 7.880269 |

| J-B | 30231.14 | 123208.4 | 9099.729 | 7515.669 | 21542.73 | 12498.44 | 1537.377 |

| Prob J-B | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ARCH LM | 736 | 677 | 301 | 312 | 185 | 415 | 181 |

| Prob | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Note: S.D, J-B, and Prob denote the standard deviation, Jarque-Bera Statitics and p-value.

3.2. Methodology

We aim to examine the response of the equity markets to macroeconomic surprises and uncertainty at different investment horizons. We employ the time-frequency approach to detect the co-movements between the G7 stock markets and macroeconomic shocks and uncertainty over the short and the long run. In addition, we employ the nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) model to examine the asymmetrical effect of macroeconomic surprises and uncertainty on the G7 stock markets. Grinsted et al. (2004) wavelet approach is used in this work because of its capacity to detect co-movements among two-time series that are both stagnant and persistent. This allows us to better grasp the link and causation between time-frequency. We apply continuous wavelet transforms (CWT) and then wavelet coherence to describe the movements of each series of data and the coherence between each variable pair.

3.2.1. Wavelet analysis

The continuous wavelet transform displays the projection of a wavelet (.) in contrast to the time sequence, that is,

| (1) |

An essential feature of CWT is its potential to decompose consequently and seamlessly recreate a time series :

| (2) |

Furthermore, this method can preserve the power of the observed time series sequence:

| (3) |

Wavelet coherence, a flexible method for determining the successiveness among two series in a multivariate regression model, may help us reach our research objectives. The co-movement between stock markets and macroeconomic surprises or uncertainty indexes can be analysed using both time scales by considering a widely implemented technique irrespective of the time series, such as the wavelet coherence framework. In practice, the cross-wavelet power and the cross-wavelet transform must first be defined. To better understand the cross-wavelet transform, Torrence and Compo (1998) suggest that two-time series and as follows:

| (4) |

where and represent two continuous transforms, the time sequence of and , and a shows the location index while b is the measure, whereas the composite conjugate is shown by (*). The cross-wavelet transform can be used to calculate the wavelet power as . When looking at the time series data, the cross-wavelet power spectrum may be used to identify the area where highly energetic clustering is evident (the cumulus of the restricted variability). It is possible to detect the areas of the time–frequency domain where the connectivity patterns of the observed time series exhibit unexpected and large changes. Torrence and Webster (1999) present the equation for the coefficient of the adjusted wavelet coherence technique:

| (5) |

where N is the smoothing mechanism. The value of the wavelet squared coherence ranges between 0 and 1 (0 ≤ ≤ 1) and displays the range of squared wavelet coherence coefficients. There is no association (no co-movement) if the correlation is near 0, but a large correlation (a scale-specific squared correlation) is visible when the correlation is close to 1. By employing the Monte Carlo approach, a theoretical allocation of wavelet coherence is studied. Squared coherence cannot distinguish between favourable and unfavourable linkages, but the WC approach allows us to investigate lead and lag links between two-time data series. Relationships and causation are depicted by the arrows pointing in the same direction (Torrence and Webster, 1999, Tiwari, 2013, Ftiti et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2017, Pal and Mitra, 2019, Jiang and Yoon, 2020, Louhichi et al., 2021). There are positive (negative) correlations when the arrows point to one side or the other. To further illustrate this point, the up-right arrows imply an up-left arrow indicates a downward arrow. This means that first series follows the second, whereas the second episode leads its predecessor. A set of arrows pointing up and down indicates that the first one is dominating and the second one is following.

3.2.2. The NARDL model: short and long terms asymmetric reaction

In the last step of our analysis, we assess the asymmetric reaction of macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes based on NARDL model, developed by Shin et al., (2014). The general form of the asymmetric ARDL approach can be writing as follows:

| (6) |

where SP is the stock market, Surp and Unc are the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes used as a first and a second independent variable. Whereas, is a vector of long-run parameters to be estimated. The Eq. (1) the and , are the partial positive and negative change sums of surprise and uncertainty indexes. They are calculated as follows:

To assess the long-run equilibrium linkage and the dynamic adjustment process, we rewrite the model (6) as follows:

| (7) |

Where, , are the partial sum coefficients in Eq. (6), which explore whether the change of macroeconomic conditions has an asymmetric effect on the equity markets.

4. Empirical results and discussion

To investigate the reaction of the equity markets to the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes of Scotti (2016), we first use the time–frequency framework to detect the symmetric linkage between the stock indices and macroeconomic conditions at different investment horizons and we then apply the NARDL model to examine the asymmetrical effect of surprises and uncertainty on the G7 markets.

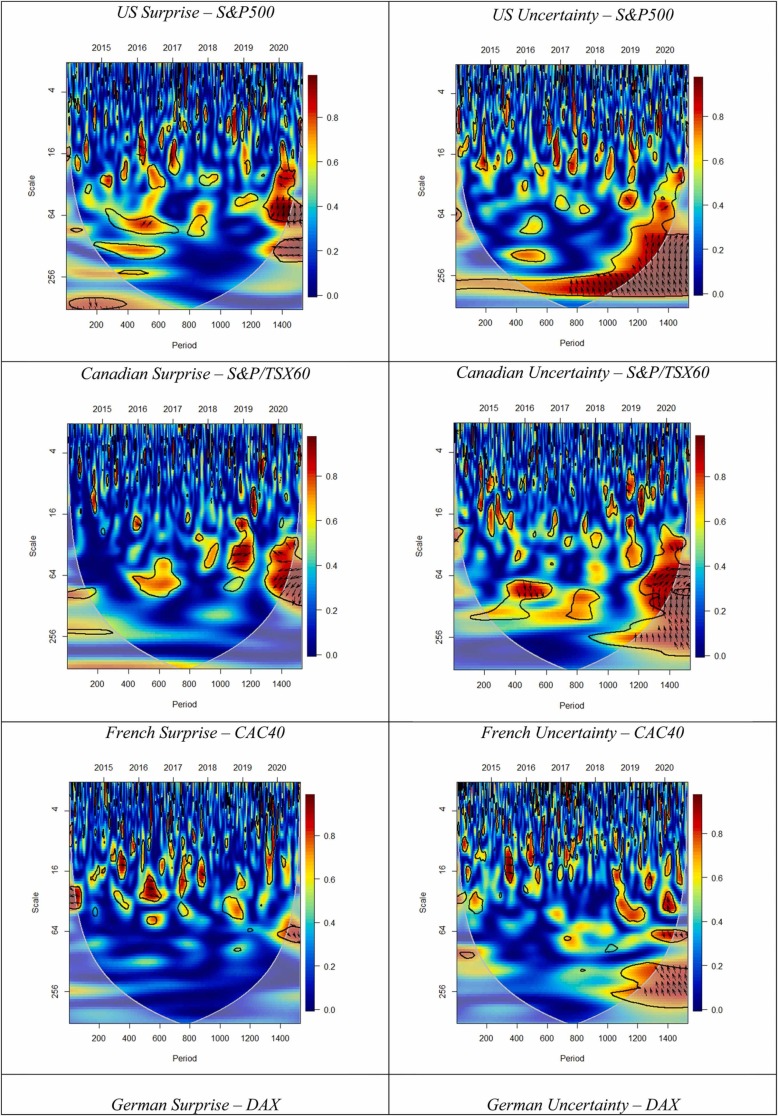

4.1. Stock markets’ reaction to macroeconomic news surprises and uncertainty: Multi-scale analysis

Applying the wavelet coherence, we examine the co-movements between the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes and the G7 stock markets. The plots of coherence between the pairs are presented in Fig. 2. Let us start our analysis with the connectedness between the macroeconomic surprises and the G7 equity markets. Overall, we identify several regions with a high degree of co-movement between all the couples before and during the COVID-19 crisis, especially over the low scale. In a comparison of the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods, we find that a vast area with a high degree of co-movements between the surprise index and the stock markets occurs during the pandemic period in the cases of the US and Canada, while France, Germany, Italy and Japan present small regions of coherence. Although the euro area shows a weak movement of the surprise index, it has a high degree of co-movement with the CAC 40, DAX and FTSE MIB stock indices. Whereas the UK index is not correlated with macroeconomic news during the pandemic, it shows strong coherence around 2014 and 2018. In the US case, the direction of the arrows is mostly up-right and up-left, respectively, indicating that the surprise index is positively correlated with the S&P 500 index, in which macroeconomic surprises lead and lag, respectively. The Canadian pair establishes a negative relationship, in which the surprise index leads the S&P/TSX 60 indexes. The euro area surprise index and stock market pairs present a positive correlation according to the direction of the arrows, which the stock market leads. In the UK’s case, the arrows point up-left around 2014, which means that the pair is negatively correlated when the FTSE 100 leads. Furthermore, the surprise index is negatively correlated with the UK stock market around 2018, and the surprise index leads. Finally, the linkage between the Japanese index and macroeconomic surprises is positive over the middle scale and negative over the long scale during the pre-COVID-19 period. On the other hand, an in-depth look at the wavelet coherence plots between the uncertainty index and the stock market pairs shows that the pandemic period is characterized by vast regions of high connectedness. From the arrows’ directions, we identify bidirectional causality between each coupled pair, and the correlation oscillates between a positive and a negative relationship, especially during the pandemic. To conclude, these results clearly indicate that the pandemic has enforced the relationships between most of the G7 indexes and news surprises as well as economic uncertainties. Overall, looking at the wavelet coherence plots between each pair, we can see over the high scale that the cold colour is dominant; however, we identify a very small number of small islands of high connectedness. Thus, we can say that, although there are some small areas of concentration of co-movements, the response of G7 markets to macroeconomic surprises and economic uncertainty is very weak compared with that in the long run before and during the pandemic period.

Fig. 2.

The Wavelet Coherence function, Note: Time period is presented on the horizontal from January, 2014 to September, 2020 and the frequency is presented on the vertical axis. On the estimated WC plots, the black contour shows the 5% significance level, the warmer colors (red) is the regions with strong co-movements, whereas colder colors (blue) represent regions with weak co-movements. The relative phasing of two series represented by arrows.

4.2. Asymmetric linkages: Evidence from NARDL model

Before investigating the short and long-run asymmetric linkages between the stock market and the macroeconomic conditions measured by the surprise and uncertainty indexes of Scotti (2016), we first check the stationarity of the series using a classical unit root test which are the ADF test and the result are presented in the Appendix A. The unit root test reveals, for different countries, that the different stock markets as well as the macroeconomic index are integrated with an order of I(0) and I(1). There is no variable integrated at the order I(2). Thus, we can continue to examine the long and short-term nexus with the NARDL Model. We also investigate the cointegration of time series. Table 2 summarize the results of bound test. Looking to the results, we reject the null hypothesis of cointegration for all countries based on the F-statistic, its great of the I(1) critical value or upper bound. We may conclude that cointegration exists among the assets under study, except the Japan case. For Japan, the F-statistic lies between the lower and upper bound critical values suggesting that the bound test is inconclusive. Overall, we may conclude that cointegration exists among the assets under study, which means that the variables move together in the long-run.

Table 2.

Bounds test for Cointegration.

| US | CA | FR | GR | IT | UK | JP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistics | 11.2782*** | 10.4544*** | 5.58642*** | 4.96753*** | 5.38297*** | 4.39777*** | 3.32970*** |

| Cointegration | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Note: the critical values have been obtained from Pesaran et al. (2001) for the lower and upper bound. * , * * and * ** denote rejection of the null hypothesis of significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

In the following, we investigate the asymmetric response of G7 stock markets to macroeconomic surprise and economic uncertainty indexes using the NARDL model. The results for whole sample period are presented in Table 3. We note first that the asymmetric effects of macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty is mixed for all stock markets. In the one side, the short-run coefficients related to positive change on surprise is positive at 1% significance level for the case of Italy and Japan, while the negative change of surprise is positive for US and Japan and it negative for UK and Canada at 5% significance level. For the positive and negative change of economic uncertainty, we note that the short-run coefficients related to positive change have a negative influence at 5% significance level on US, France, Germany and Italy stock markets. Whereas, the negative change of uncertainty have a positive impact on Canada, France and Germany indexes. For the Japan, we find that the stock index responds positively and negatively to the negative change of uncertainty based on the result of selected t, t-6 and t-8. In another side, looking to the long-run coefficients shows asymmetric effects of macroeconomic conditions on most stock markets. For US, the positive change of uncertainty has a positive effect on the stock index at 5% significance level. Similar results are obtained for the Canadian market. Whereas, Japan index negatively impacted by the negative surprise and positive uncertainty. Meanwhile, the negative uncertainty has a positive repercussion on the Japan market. However, the asymmetric results for Euro countries and UK indicate no asymmetric response to the macroeconomic indexes at the long-run.

Table 3.

The dynamic nonlinear estimation: Full sample period.

| US | CA | FR | GR | IT | UK | JP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0.165038 | -0.032932 | 0.246092 | 0.170708 | 0.131085 | -0.042550 | 0.131447 |

| SP (−1) | -0.827196a | -0.663929a | -0.599982a | -0.565143a | -0.629449a | -0.551482a | -0.592190a |

| Surp P(−1) | -0.136959 | -0.385717a | -0.106851 | 0.084386 | 0.015581 | -0.212321 | 0.559481 |

| Surp N(−1) | -0.085924 | -0.182219 | 0.054930 | -0.012237 | 0.028758 | -0.171146 | -0.753048b |

| Unc P(−1) | 0.124729b | 0.495209b | 0.169384 | 0.088413 | 0.162230 | -0.040666 | -0.530834c |

| Unc N(−1) | 0.084294 | 0.258710 | -0.034160 | 0.241259 | 0.160555 | -0.087176 | 0.865636c |

| Short-run coefficient | |||||||

| D Surp P(−3) | – | – | – | – | 2.448908a | 6.296937a | |

| D Surp N(−2) | – | – | – | – | – | -3.364433b | |

| D Surp N(−5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6.426906a |

| D Surp N(−6) | 0.814398b | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D Surp N(−8) | – | -2.858621b | – | – | – | ||

| D Unc P | – | – | -5.987523a | -5.260998a | -5.610534a | – | – |

| D Unc P(−4) | -1.098900a | – | – | – | – | ||

| D Unc N | – | – | – | – | -3.272438b | ||

| D Unc N(−4) | – | – | 3.906597a | 3.532656b | – | – | |

| D Unc N(−6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | -5.226019b |

| D Unc N(−8) | – | 1.595064c | – | – | – | – | 8.968766a |

| Long-run coefficient | |||||||

| L Surp N | -0.103874 | -0.274456 | 0.091553 | -0.021653 | 0.045688 | -0.310339 | -1.271633b |

| L Surp P | -0.165571 | -0.580961a | -0.178091 | 0.149317 | 0.024754 | -0.385001 | 0.944766 |

| L Unc N | 0.101904 | 0.389665 | -0.056935 | 0.426899 | 0.255072 | -0.158076 | 1.461753c |

| L Unc P | 0.150785b | 0.745877b | 0.282316 | 0.156444 | 0.257734 | -0.073740 | -0.896392c |

| Diagnostic Checking | |||||||

| R2 | 0.696763 | 0.709410 | 0.578454 | 0.560521 | 0.586870 | 0.551803 | 0.534806 |

| X2SC | 0.565118 | 1.113881 | 1.656827 | 1.353410 | 1.289927 | 0.248467 | 0.227165 |

| X2HET-BPG | 0.808537 | 0.936392 | 1.783607 | 2.044765 | 0.417468 | 1.940251 | 1.282054 |

| X2RS | 0.066540 | 1.944763 | 1.486123 | 0.473382 | 0.056505 | 1.338155 | 0.955606 |

| X2J-B | 5469,102a | 2332,72a | 2400, 859a | 1076,038a | 5089,168a | 4733,745a | 560,7217a |

Note: a, b and c indicates the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. We did not report the short-term coefficients that are not significant. X2SC, X2HET-BPG, X2RSand X2J-B represent the LM serial correlation test, Breusch–Pagan Godfrey test for heteroscedasticity, Ramsey reset test for model specification and Jarque–Bera normality test, respectively. Based on diagnostic tests, the estimates model appears to surpass all diagnostic tests, except normality test.

In the following, we examine the asymmetric linkage during the COVID-19 crisis period using the NARDL model to explore the role of the pandemic on the asymmetric response of the G7 market to the macroeconomic index. As the date of beginning of lockdown period is different from country to another,2 the COVID-19 sample starts from the first day of the lockdown to the end of the sample period for each country.

The results concerning the short and long-run asymmetric linkages between the stock market and both macroeconomic condition indexes during the COVID-19 outbreak are presented in Table 4. Concerning the short-run findings, we find that the positive change of surprise has a positive influence on Italy and Germany stock markets at 5% significance level. Whereas, it have a negative effect on France index only at 1% significance level. While, the negative change of the surprise coefficient is positive for France, Germany, Italy and Japan at 1% significance level. Nevertheless, for the short-run uncertainty impacts, we find that the positive change affect negatively France, Germany and Italy markets at 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively. Furthermore, the negative change of uncertainty has a negative influence on the three euro index at 1% significance level, whereas it affect positively at 1% significance level the Japan market. While US, Canada and UK show a symmetry linkage at the short-run. In contrast, for the long-run asymmetric effects of macroeconomic condition on stock markets, we find that the negative change of the surprise affect negatively the US, France, Italy and Japan index at 1% and 10% significance levels, and it affects positively the German index. Whereas, the positive change of the surprise shows a negative influence on France and Japan stock markets. However, it has a positive impact on German stock index. Moreover, the negative and positive change of uncertainty also present a long-run effect on most stock markets. German stock market responds negatively to negative uncertainty, whereas, France and Japan stock market respond positively. The positive change of uncertainty affects positively the France market and also exhibit a negative impact on US and German stock markets. However, the Canadian and UK indexes show a symmetry linkage.

Table 4.

The dynamic nonlinear estimation: COVID-19 period.

| US | CA | FR | GR | IT | UK | JP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | -2.595255a | 1.300733a | -1.915031c | -0.549048 | -2.462924a | 0.082439 | 0.662684b |

| SP (−1) | -1.480819a | -1.619504a | -1.112619a | -0.956074a | -0.972070a | -1.068590a | -1.383543a |

| Surp P(−1) | -7.85E-05 | -0.007030 | -0.047647a | 0.008475a | -0.006004a | -0.000353 | -0.017499a |

| Surp N(−1) | -0.002900c | 0.006983 | -0.049954a | 0.008063a | -0.009570 | -0.000542 | -0.017655a |

| Unc P(−1) | -0.034412c | 0.015416 | 0.111716a | -0.043164 | 0.010769 | -0.004947 | 0.011645 |

| Unc N(−1) | -0.023894 | -0.007811 | 0.115669a | -0.041836c | 0.020469 | -0.004366 | 0.018461b |

| Short-run coefficient | |||||||

| D Surp P | – | – | -0.067245a | – | – | – | – |

| D Surp P(−1) | – | – | – | – | 0.010265b | – | – |

| D Surp P(−4) | – | – | – | 0.004077b | – | – | – |

| D Surp N | – | – | 0.020559a | 0.012341a | – | – | – |

| D Surp N(−1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.020208a |

| D Surp N(−2) | – | – | 0.013885a | – | 0.024070a | – | – |

| D Unc P | – | – | – | – | -0.057960a | – | – |

| D Unc P(−2) | – | – | -0.100147a | – | -0.085669b | – | – |

| D Unc P(−3) | – | – | – | -0.094315a | – | – | – |

| D Unc P(−4) | – | – | – | -0.033329a | – | – | – |

| D Unc N | – | – | – | -0.083086a | – | – | – |

| D Unc N(−1) | – | – | -0.141895a | – | -0.112985a | – | – |

| D Unc N(−2) | – | – | – | -0.104866a | – | – | – |

| D Unc N(−3) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.484271a |

| Long-run coefficient | |||||||

| L Surp N | -0.001958c | 0.004312 | -0.044898a | 0.008434a | -0.009845a | -0.000507 | -0.012760a |

| L Surp P | -5.30E-05 | -0.004341 | -0.042824a | 0.008865a | -0.006177 | -0.000330 | -0.012648a |

| L Unc N | -0.016136 | -0.004823 | 0.103961a | -0.043759c | 0.021057 | -0.004086 | 0.013343b |

| L Unc P | -0.023238c | 0.009519 | 0.100408a | -0.045147c | 0.011078 | -0.004630 | 0.008417 |

| Diagnostic Checking | |||||||

| R2 | 0.779231 | 0.767146 | 0.811838 | 0.624707 | 0.704485 | 0.573050 | 0.778627 |

| X2SC | 0.476861 | 1.997274 | 0.007944 | 1.064737 | 1.796889 | 1.391516 | 1.350345 |

| X2HET-BPG | 1.580260 | 0.022423 | 1.088075 | 1.278428 | 0.076899 | 0.369576 | 0.412846 |

| X2RS | 0.462855 | 0.316891 | 0.071287 | 0.933661 | 1.910523 | 1.492393 | 0.047369 |

| X2J-B | 67,416a | 52,276a | 5781b | 92,484a | 174,59a | 7249b | 0605 |

Note: a, b and c indicates the level of significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. We did not report the short-term coefficients that are not significant. X2SC, X2HET-BPG, X2RSand X2J-B represent the LM serial correlation test, Breusch–Pagan Godfrey test for heteroscedasticity, Ramsey reset test for model specification and Jarque–Bera normality test, respectively. Based on diagnostic tests, the estimates model appears to surpass all diagnostic tests, except normality test. Only Japan surpass the Jraque-Berra test.

Overall, when comparing between Table 3, Table 4, we can see clearly that the COVID-19 pandemic affects the asymmetric linkages between the macroeconomic conditions and G7 stock markets at both short and long-run. In fact, the euro markets indexes present more asymmetric linkage at both short and long-run during the COVID-19 sample period. Whereas US, Canada and UK show present a symmetry response to the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes at the short-run. For the long-run, the Canadian and UK stock indexes still providing a symmetric linkages. Moreover, we provide evidence that the response of the stock markets at the short and long-run to the positive and negative change of surprise and uncertainty indexes are different between the full sample period and the COVID-19 period. This result confirms the effect of the pandemic crisis on the symmetric and asymmetric linkages at both short and long-term analysis.

5. Results discussion

Our findings provide many important recommendations for speculators and investors in the G7 markets at different investment horizons, considering the effect of macroeconomic news and economic uncertainty on the main stock markets. According to the wavelet approach, the macroeconomic surprise index shows a weak response, and this is related to the effect of the lockdown policy and the harsh restrictions leading to the economic recession during the pandemic. The wavelet coherence exhibits a high level of connectedness between most equity markets and the news surprise and uncertainty indexes over the long-term. Indeed, the effect is most pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic between the economic uncertainty index and the financial stock markets. This finding is expected because the COVID-19 crisis causes damageable consequences for financial markets, and the uncertainty about the end date of this crisis increases the economic uncertainty levels and the fear in the financial markets. Therefore, the repercussions of the pandemic support the connectedness between stock indices and uncertainty (Sharif et al., 2020).

Moreover, the surprise index presents exhibits a strong relationship with the stock indices. We note that the wavelet coherence method shows that the co-movement levels between the sample variables under examination is very weak in the short term, regardless of the existence of very small islands of coherence. The long-run response can be explained by the macroeconomic channels. The nature of composition of the macroeconomic indexes which they cover many economic indicators such as the quarterly real GDP, monthly industrial production (IP), employees on non-agricultural payrolls, when available, or the unemployment rate, monthly retail sales and finally a survey measure of the manufacturing sector. Thus, the literature widely discussed the long-term effect of macroeconomic indicators on financial markets during calm and extreme market period and crisis (see Antonakakis et al. 2017; Celebi and Hönig, 2019, Chang et al., 2020; among others).

We have also investigated the possibility of asymmetric response of stock indexes to the macroeconomic conditions at short and long-term horizons using the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag model. Overall, we find that the G7 market react differently to the macroeconomic surprise and uncertainty indexes over the full sample period and during the COVID-19 crisis. The market reaction depends on the economic state of each country. Asymmetrical effects of macroeconomic states to equities confirmed by several prior studies (see Bahmani-Oskooee and Saha, 2015, Bahmani-Oskooee and Saha, 2016; Cheah et al., 2017; Anjum et al., 2017; Dhaoui et al., 2018; Lee and Ryu, 2018; Erdoğan and Tiryaki, 2018; Alqaralleh, 2020; among others). Nevertheless, the asymmetric findings show that the COVID-19 crisis affects the asymmetric linkages for most stock markets, based on the short and long-run analysis. The macroeconomic conditions are shown to have an asymmetric impact during time of crisis and the effect is more pounced at long-run horizons. More specifically, the asymmetric results show that the long-run linkage is more intense when we focus on the pandemic period compared to the full sample results.

In another hand, as indicated by Koutmos, 1998, Koutmos, 1999, the stock markets respond to bad news faster than the good news. Our findings show that the most financial markets are more sensitive to bad macroeconomic news than good macroeconomic news at long-run during the pandemic period. This was expected due to the economic and financial consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. A bad report about the economic health lead to decrease in the most stocks. In fact, the negative news leads investors to sell stocks.

Overall, this paper indicate that the macroeconomic conditions can plays an important role in driving the stock market behaviours. The unpredictable macroeconomic condition change is the main source of the macroeconomic risk which is an aggregate reflection of economic health for a nation. This risk defined as the change in financial asset prices due to persistent shocks to the real economy (see Winkelmann et al., 2012). Our study reveal that the macro-risk increased during the pandemic due to the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the economy. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the global economic system experienced two shocks i.e. demand and supply shocks, which contributes to the rising of the macroeconomic risk. This is expected because the pandemic is considered as a systematic risk which affect the entire economic factors leading to high macroeconomic risk, and then directly influence the financial markets.

The results of stock markets’ sensitivity to macroeconomic announcements and uncertainty may be applied for asset pricing and portfolio selection and for the assessment of investment horizon decisions with respect to macroeconomic state releases. The reported data about the state of the regional economy impacts stock prices behaviors. Thus, if the statistics about the macro-economic indicators are more (less) that investor’s expectation, this will lead stock prices to go up (down). Nonetheless, the stock market responds more noticeably to unexpected economic changes which can make it unpredictable. Overall, our results highlight that investors should pay more attention to the change on the economic conditions.

6. Conclusion

The effect of macroeconomic indicators on the financial markets is one of the most important topics covered in the literature during the last two decades. This study aims to revisit the relationship between the macroeconomic state and the stock market indices, including the COVID-19 period. To this end, we apply the wavelet approach and the NARDL model to investigate the relationship at different investment horizons and the asymmetrical linkage between the individual G7 stock markets and two real-time indexes: the macroeconomic news surprise and uncertainty indexes developed by Scotti (2016). Our findings from the wavelet coherence documents a high degree of connectedness between the individual G7 stock markets and the news surprise and uncertainty indexes over the low scale. We document that the strongest interconnection is between the G7 stock indices and the uncertainty index, especially during the pandemic. Furthermore, we can see clearly that, in the short term, the connectedness levels are weaker than at the low scale. In another side, the NARDL model reveal evidence of asymmetric linkage between the equity markets and each macroeconomic condition index at short- and long-run for most G7 economies. Overall, we provide that the effect of positive and negative macroeconomic shocks are impacted by the pandemic period, which imply that the COVID-19 crisis affects the asymmetric associations.

Our study highlights the importance of the role played by macroeconomic surprises and economic uncertainty on the stock market behaviors, especially during the COVID-19 crisis. Several practical implications can be derived from such finding for policymakers as well as heterogeneous investors. The macroeconomic risk coming from the change of the economic factors have proven to be highly correlated to the stock market prices at long-term than short-term. Finally, the date concerning the Scotti (2016) indexes is available only for the developed economies. For that reason, we didn’t investigate the effect of macroeconomic surprises for non-G7 countries such as emerging economies (like BRICS and Asian economies). Future research should overcome this limitation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Houssam Bouzgarrou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Zied Ftiti: Data curation, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Waël Louhichi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Project administration. Mohamed Yousfi: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Footnotes

Results of ADF test are available upon authors request.

Canada 13 March, France and Germany 17 March, Italy 9 March, Japan 9 April, UK 24 March and for US the most lockdown periods of the state and territorial, tribal are start since 15 March. We take this dates from https://auravision.ai/covid19-lockdown-tracker/.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aharon D.Y., Demir E., Lau C.K.M., Zaremba A. Twitter-Based uncertainty and cryptocurrency returns. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022;59 [Google Scholar]

- Akron S., Demir E., Díez-Esteban J.M., García-Gómez C.D. How does uncertainty affect corporate investment inefficiency? Evidence from Europe. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022;62 [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khazali O., Elie B., Roubaud D. The impact of positive and negative macroeconomic news surprises: Gold versus Bitcoin. Econ. Bull. 2018;38(1):373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Alqaralleh H. Stock return-inflation nexus; revisited evidence based on nonlinear ARDL. J. Appl. Econ. 2020;23(1):66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Amar A.B., Belaid F., Youssef A.B., Chiao B., Guesmi K. The unprecedented reaction of equity and commodity markets to COVID-19. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros M., Frenkel M., Huynh T.L.D., Kilinc M. COVID-19 pandemic news and stock market reaction during the onset of the crisis: evidence from high-frequency data. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021;28(19):1686–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum N., Ghumro N.H., Husain B. Asymmetric impact of exchange rate changes on stock prices: empirical evidence from Germany. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Res. 2017;3(11):240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis N., Gupta R., Tiwari A.K. Has the correlation of inflation and stock prices changed in the United States over the last two centuries? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017;42:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ayadi M.A., Omrane W.B., Lazrak S., Yan X. OPEC production decisions, macroeconomic news, and volatility in the Canadian currency and oil markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020;37 [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann R., Elstner S., Sims E.R. Uncertainty and economic activity: Evidence from business survey data. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 2013;5(2):217–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bahloul W., Gupta R. Impact of macroeconomic news surprises and uncertainty for major economies on returns and volatility of oil futures. Int. Econ. 2018;156:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmani-Oskooee M., Saha S. On the relation between stock prices and exchange rates: a review article. J. Econ. Stud. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Bahmani-Oskooee M., Saha S. Do exchange rate changes have symmetric or asymmetric effects on stock prices? Global finance journal. 2016;31:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Terry S.J. No. w26983. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. (Covid-induced Economic Uncertainty). [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Bloom N., Davis S.J. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The quarterly journal of economics. 2016;131(4):1593–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Scott R., Bloom Nicholas, Davis Steven J., Kost Kyle, Sammon Marco, Viratyosin Tasaneeya. The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020;10:742–758. [Google Scholar]

- Balcilar M., Cakan E., Gupta R. Does US news impact Asian emerging markets? Evidence from nonparametric causality-in-quantiles test. North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2017;41:32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A.K., Pradhan H.K., Tripathy T., Kanagaraj A. Macroeconomic news surprises, volume and volatility relationship in index futures market. Appl. Econ. 2020;52(3):275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert G., Hoerova M., Duca M.L. Risk, uncertainty and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2013;60(7):771–788. [Google Scholar]

- Belgacem A., Creti A., Guesmi K., Lahiani A. Volatility spillovers and macroeconomic announcements: evidence from crude oil markets. Appl. Econ. 2015;47(28):2974–2984. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan E.M., Chowdhury M. Macroeconomic variables and stock market indices: Asymmetric dynamics in the US and Canada. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020;77:62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cakan E., Doytch N., Upadhyaya K.P. Does US macroeconomic news make emerging financial markets riskier? Borsa Istanbul Review. 2015;15(1):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Celebi K., Hönig M. The impact of macroeconomic factors on the German stock market: evidence for the crisis, pre-and post-crisis periods. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2019;7(2):18. [Google Scholar]

- Chang B.H., Bhutto N.A., Turi J.A., Hashmi S.M., Gohar R. Macroeconomic variables and stock indices: an asymmetric evidence from quantile ARDL model. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Cheah S.P., Yiew T.H., Ng C.F. A nonlinear ARDL analysis on the relation between stock price and exchange rate in Malaysia. Econ. Bull. 2017;37(1):336–346. [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Larkin C., Lucey B. The contagion effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from gold and cryptocurrencies. Finance Research Letters. 2020;35:101554. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D., Kannadhasan M., Bhattacharyya M. Do the emerging stock markets react to international economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk and financial stress alike? North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2019;48:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaoui A., Goutte S., Guesmi K. The asymmetric responses of stock markets. J. Econ. Integr. 2018;33(1):1096–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan L., Tiryaki A. Asymmetric effects of macroeconomic shocks on the stock returns of the G-7 countries: the evidence from the NARDL approach. J. Curr. Res. Bus. Econ. 2018;8(1):119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Esin C., Gupta R. Does the US. macroeconomic news make the South African stock market riskier? J. Dev. Areas. 2017;51(4):15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ftiti Z., Fatnassi I., Tiwari A.K. Neoclassical finance, behavioral finance and noise traders: assessment of gold–oil markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2016;17:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goodell J.W., Huynh T.L.D. Did Congress trade ahead? Considering the reaction of US industries to COVID-19. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinsted A., Moore J.C., Jevrejeva S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2004;11(5/6):561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Harju K., Hussain S.M. Intraday seasonalities and macroeconomic news announcements. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2011;17(2):367–390. [Google Scholar]

- Humpe A., Macmillan P. Can macroeconomic variables explain long-term stock market movements? A comparison of the US and Japan. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2009;19(2):111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Humpe A., McMillan D.G. Macroeconomic variables and long-term stock market performance. A panel ARDL cointegration approach for G7 countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020;8(1):1816257. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S.M., Omrane W.B., Al-Yahyaee K. US macroeconomic news effects around the US and European financial crises: evidence from Brazilian and Mexican equity indices. Global Financ. J. 2020;46 [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T.L.D., Foglia M., Nasir M.A., Angelini E. Feverish sentiment and global equity markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2021;188:1088–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Yoon S.M. Dynamic co-movement between oil and stock markets in oil-importing and oil-exporting countries: Two types of wavelet analysis. Energy Economics. 2020;90 [Google Scholar]

- Kannadhasan M., Das D. Do Asian emerging stock markets react to international economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical risk alike? A quantile regression approach. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020;34 [Google Scholar]

- Koutmos G. Asymmetries in the conditional mean and the conditional variance: evidence from nine stock markets. J. Econ. Bus. 1998;50(3):277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Koutmos G. Asymmetric price and volatility adjustments in emerging Asian stock markets. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 1999;26(1–2):83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Leduc S., Liu Z. Uncertainty shocks are aggregate demand shocks. J. Monet. Econ. 2016;82:20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Ryu D. Asymmetry in the stock price response to macroeconomic shocks: evidence from the Korean market. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2018;19(2):343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Ma F., Zhang X., Zhang Y. Economic policy uncertainty and the Chinese stock market volatility: novel evidence. Econ. Model. 2020;87:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ma F., Zhang Y., Xiao Z. Economic policy uncertainty and the Chinese stock market volatility: new evidence. Appl. Econ. 2019;51(49):5398–5410. [Google Scholar]

- Louhichi W., Ftiti Z., Ameur H.B. Measuring the global economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak: Evidence from the main cluster countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;167 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin W., Fernando R. The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: seven scenarios. Asian Econ. Papers. 2021;20(2):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak S., Andritzky J., Jobst A., Tamirisa N. Macroeconomic fundamentals, price discovery, and volatility dynamics in emerging bond markets. J. Banking & Financ. 2011;35(10):2584–2597. [Google Scholar]

- Pal D., Mitra S.K. Oil price and automobile stock return co-movement: a wavelet coherence analysis. Econ. Model. 2019;76:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Parab N., Reddy Y.V. The dynamics of macroeconomic variables in Indian stock market: a Bai–Perron approach. Macroecon. Financ. Emerging Market Econ. 2020;13(1):89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran M.H., Shin Y., Smith R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001;16(3):289–326. [Google Scholar]

- Queku I.C., Gyedu S., Carsamer E. Stock prices and macroeconomic information in Ghana: speed of adjustment and bi-causality analysis. Int. J. Emerg. Markets. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Rangel J.G. Macroeconomic news, announcements, and stock market jump intensity dynamics. J. Bank. Financ. 2011;35(5):1263–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Ratanapakorn O., Sharma S.C. Dynamic analysis between the US stock returns and the macroeconomic variables. Appl. Financ. Econom. 2007;17(5):369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Schell D., Wang M., Huynh T.L.D. This time is indeed different: a study on global market reactions to public health crisis. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti C. Surprise and uncertainty indexes: real-time aggregation of real-activity macro-surprises. J. Monet. Econom. 2016;82:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif A., Aloui C., Yarovaya L. COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geopolitical risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the US economy: Fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2020;70 doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y., Yu B., Greenwood-Nimmo M. Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt; pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A.K. Oil prices and the macroeconomy reconsideration for Germany: using continuous Wavelet. Econom. Model. 2013;30:636–642. [Google Scholar]

- Torrence C., Compo G.P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998;79(1):61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Torrence C., Webster P.J. Interdecadal changes in the ENSO–Monsoon system. J. Clim. 1999;12(8):2679–2690. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Mbanyele W., Muchenje L. Economic policy uncertainty and stock liquidity: the mitigating effect of information disclosure. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022;59 [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann K., Hentschel L., Suryanarayanan R., Varga K. Macro-sensitive portfolio strategies: how we define macroeconomic risk. MSCI Market Insight. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Cai X.J., Hamori S. Does the crude oil price influence the exchange rates of oil-importing and oil-exporting countries differently? A wavelet coherence analysis. Int. Rev.Econom. Financ. 2017;49:536–547. [Google Scholar]

- Yousfi M., Dhaoui A., Bouzgarrou H. Risk spillover during the COVID-19 global pandemic and portfolio management. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021;14(5):222. [Google Scholar]

- Yousfi M., Zaied Y.B., Cheikh N.B., Lahouel B.B., Bouzgarrou H. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the US stock market and uncertainty: A comparative assessment between the first and second waves. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;167 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Hu M., Ji Q. Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.