Introduction:

The COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide restriction measures have disrupted health care delivery and access for the general population. There is limited evidence about access to care issues (delayed and forgone care) due to the pandemic among people with disability (PWD).

Methods:

This study used the 2020 National Health Interview Survey data. Disability status was defined by disability severity (moderate and severe disability), type, and the number of disabling limitations. Descriptive analysis and multivariate logistic regression (adjusted for sociodemographic and health-related characteristics) were conducted to estimate delayed/forgone care (yes/no) between PWD and people without disability (PWoD).

Results:

Among 17,528 US adults, 40.7% reported living with disability. A higher proportion of respondents with severe and moderate disability reported delaying care than PWoD (severe=33.2%; moderate=27.5%; PWoD=20.0%, P<0.001). The same was true for forgone medical care (severe=26.6%; moderate=19.0%; PWoD=12.2%, P<0.001). Respondents with a moderate disability {delayed [odds ratio (OR)=1.33, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.19, 1.49]; forgone [OR=1.46, 95% CI=1.28, 1.67]} and a severe disability [delayed (OR=1.52, 95% CI=1.27, 1.83); forgone (OR=1.84, 95% CI=1.49, 2.27)] were more likely to report delayed medical care and forgone medical care compared with PWoD. These findings were consistent across the models using disability type and the number of limitations.

Conclusions:

PWD were more likely to experience COVID-19-related delays in or forgone medical care compared with PWoD. The more severe and higher frequency of disabling limitations were associated with higher degrees of delayed and forgone medical care. Policymakers need to develop disability-inclusive responses to public health emergencies and postpandemic care provision among PWD.

Key Words: people with disability, COVID-19 Pandemic, delayed care, forgone care

The population of people with disabilities (PWDs) has increased during the past 2 decades along with aging population.1,2 As of 2018, nearly 1 in 4 US adults are estimated to live with a disability.3 Changing demographics and increased prevalence of PWD with various chronic conditions pose multifaceted health, social, and economic challenges, resulting in increased demands for health care. The complex health care needs of PWD require that patient-centered and comprehensive health services be available, affordable, and accessible to them. Timely receipt of high-quality health care is important for PWD and their families. However, PWD have more unmet health care needs (defined as situations in which an individual needed health care but did not, or was not able to, receive it) compared with people without disabilities (PWoD).4–8 For example, people with physical disabilities have 75% higher odds of having unmet medical needs in general, and PWD with serious mental illness have 65% higher odds of reporting unmet mental service needs than PWoD.4,6 Unmet health care needs may exacerbate existing health condition(s) for PWD and lead to serious adverse health outcomes.8,9

Of recent concern, the COVID-19 pandemic (the “pandemic”) and nationwide restriction measures have disrupted health care delivery and access for the general population as well as PWD. Previous studies showed as high as 40% of US adults reported forgone needed health care during the pandemic, raising concerns about adverse health outcomes at a population level. PWD are at greater risk of pandemic-related outcomes (such as people with vision limitation are more likely to contract the virus, and PWD may also be at higher risk of COVID-19 caused mortality),10–12 and they are disproportionally affected by restrictions and other mitigation-related policies.13 Considering the considerable health care needs and issues of unmet health care among the PWD before the pandemic, it is imperative to understand how the pandemic differently affected access to health care between PWD and PWoD. Providing up-to-date population-based evidence could help inform policymakers and our health care system of the need for disability-inclusive responses and preparedness in this ongoing pandemic.

Several studies showed an increased prevalence of delayed and forgone health care during the pandemic.14–17 However, most studies have focused on the general population, and to our knowledge, no known study has examined access to health care among PWD in the United States. Some perspective papers discussed the impact of the pandemic on health care issues among PWD,18–20 and other studies examined health care access among PWD using samples from European or East Asian countries.21,22 Because of this lack of nationally representative studies, less is known about the risks of disrupted health care access for PWD in the United States during the pandemic. To address these gaps, we aimed to examine the association between the presence of disability and access to care issues (delayed and forgone care) because of the pandemic among US adults using the 2020 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

METHODS

Study Sample

We used data from the 2020 NHIS, a nationally representative survey covering noninstitutionalized populations in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.23 NHIS uses a complex and multistage sampling framework and typically was conducted in-person at the respondent’s home.23 However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most interviews in 2020 were conducted by telephone from March of 2020 to December of 2020. The final adult response rate for the 2020 sample was 48.9%, which was lower than previous years.23 Our analytic sample includes 17,528 adults (representing 249,969,381 US adults) aged 18 years and older with information on all measures of interest who were interviewed in the third and fourth quarter of 2020. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida as the data were de-identified and publicly available.

Measures

The 2 binary health care access-related outcomes were captured using respondents’ answers to the following 2 questions which were added to the 2020 NHIS in July of 2020,23 respectively: (1) was there any time when you delayed getting medical care because of the coronavirus pandemic? (2) was there any time when you needed medical care for something other than coronavirus, but did not get it because of the coronavirus pandemic? Respondents who answered “yes” to the first question were defined as “yes” for delayed any medical care (delayed care); those who answered “no” were defined as having no delayed care. Similarly, adults who responded “yes” to the second question were classified as experiencing forgone non-COVID-19-related care (forgone care); those who answered “no” considered as no forgone care reported.

Functional disability status was derived using 6 questions: (1) do you have difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses? (2) do you have difficulty hearing even when using your hearing aid(s)? (3) do you have difficulty remembering or concentrating? (4) do you have difficulty walking or climbing steps? (5) do you have difficulty with self-care, such as washing all over or dressing? (6) Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have difficulty doing errands alone such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping? The NHIS used a 4-point scale (no difficulty, some difficulties, a lot of difficulties, or you cannot do this at all) to ascertain the severity of the disability. After previous studies, we first categorized the presence of functional disability into three levels by severity: (1) no functional disability (reference group, if respondents answered “no difficulty” to all the 6 questions), (2) moderate disability (if they responded “some difficulties” to any of the 6 questions and did not report “a lot of difficulties” and “cannot do at all” to any of the questions), and (3) severe disability (if they answered “a lot of difficulties” or“ cannot do at all” to any of above 6 questions).24 Next, we categorized included adults into 6 groups by type of functional disability based on their responses to the above 6 questions: (1) no functional disability, (2) hearing limitation only, (3) vision limitation only, (4) cognitive limitation only, (5) mobility or complex activity limitation only (if “yes” to either item 4, 5, or 6 and “no” to the remaining items), and ≥2 limitations.7,9 Finally, we categorized the respondents by number of limitations into 4 groups (0, 1, 2, and ≥3).9

To control for potential confounding, our analysis included covariates based on Anderson’s behavioral model of health care utilization, which includes predisposing, enabling, and need factors.9,25 Covariates are: age (18–49, 50–64, ≥65), sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other), marital status (married, single, other), education level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college/associate degree, college graduate), worked last week (yes, no, unknown), income to federal poverty ratio (<200%, 200%–400%, >400%), number of children in family (0, 1, 2, 3+), interview date in 2020 (July–September, October–December), census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), urban/rural (large central metro, large fringe metro, medium/small metro, nonmetropolitan), having a usual source of care (yes, no), insurance coverage (private, public/other, none), ever smoker (yes, no), drinking status (never, former, current), health status (excellent, very good, good, fair/poor), and the number of chronic conditions, including heart diseases, chronic lung diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer (0, 1, ≥2).

Statistical Analysis

We first compared the sociodemographic and health-related characteristics by the severity of disability (none, moderate disability, and severe disability) using χ2 tests. We then constructed 6 separate series of multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to investigate associations for functional disability with delayed and forgone medical care. We used Akaike Information Criterion to determine the model fit.26 To further understand the disparities in delayed and forgone medical care across different age groups,27 we used an interaction term (age*severity of disability) in the models to estimate the risk of delayed (P=0.049) and forgone medical care (P=0.042) for those aged 50–64 years and 18–49 years compared with their counterparts aged older than or equal to 65 years, within each disability severity group. To account for the complex survey design of the NHIS, we used survey data analysis procedures with recommended sampling weights provided by the NHIS to produce nationally representative estimates. To adjust for multiple testing, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure,28 and adjusted P-values are reported. We conducted all analyses using SAS 9.4 and assessed the statistical significance level at 0.05. Finally, we used STROBE as a reporting guideline for this study.

RESULTS

Overall, nearly one-third (32.0%) and 8.7% of adults reported a moderate disability and a severe disability, respectively. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the study sample and bivariate analysis based on degree of disability. A higher percentage of respondents with a severe disability were aged older than or equal to 65 years, were female, were non-Hispanic White, were single, did not have a high school education, did not work in last week, had family income level at <200% federal poverty level, had zero child in the family, resided in the South census region, had public insurance coverage, had a usual source of care, had ever smoked, had fair/poor self-reported health status, and had ≥2 chronic conditions compared with PWoD. Similar distributions were detected among respondents with a moderate disability compared with PWoD.

TABLE 1.

Respondents’ Sociodemographic and Health-related Characteristics by Disability Severity (N=17,528, Weighted N=249,969,381)

| Disability Severity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None n=9654 (Weighted n=148,102,805) | Moderate n=6138 (Weighted n=80,026,065) | Severe n=1736 (Weighted n=21,840,511) | |||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | P |

| Age group (y) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 18–49 | 64.5 | 63.1–65.8 | 40.7 | 38.8–42.6 | 25.7 | 22.5–28.9 | |

| 50–64 | 22.2 | 21.1–23.3 | 28.3 | 26.8–29.9 | 28.9 | 26.2–31.7 | |

| ≥65 | 13.3 | 12.6–14.1 | 31.0 | 29.4–32.6 | 45.4 | 42.0–48.7 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 49.7 | 48.4–51.1 | 47.1 | 45.4–48.8 | 42.3 | 39.1–45.5 | |

| Female | 50.3 | 48.9–51.6 | 52.9 | 51.2–54.6 | 57.7 | 54.5–60.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||

| NH White | 59.9 | 57.8–62.0 | 67.9 | 65.7–70.2 | 65.5 | 61.7–69.4 | |

| NH Black | 11.8 | 10.5–13.1 | 11.3 | 10.0–12.6 | 12.2 | 9.8–14.7 | |

| Hispanic | 18.5 | 16.6–20.3 | 14.2 | 12.3–16.0 | 15.0 | 11.7–18.3 | |

| Other | 9.8 | 8.7–10.9 | 6.6 | 5.5–7.8 | 7.2 | 5.0–9.4 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married | 52.6 | 51.0–54.1 | 51.4 | 49.6–53.1 | 37.9 | 34.7–41.0 | |

| Single | 35.5 | 34.1–36.9 | 38.4 | 36.6–40.1 | 50.3 | 47.1–53.6 | |

| Other | 11.9 | 11.0–12.8 | 10.3 | 9.1–11.4 | 11.8 | 9.4–14.2 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less high school | 11.2 | 10.1–12.3 | 16.4 | 14.8–18.1 | 29.7 | 26.5–33.0 | |

| High school graduate | 25.1 | 23.8–26.4 | 27.8 | 26.2–29.4 | 28.6 | 25.9–31.3 | |

| Some college/associate degree | 28.6 | 27.4–29.8 | 31.4 | 29.9–33.0 | 27.6 | 25.0–30.3 | |

| College graduate | 35.1 | 33.6–36.6 | 24.3 | 23.1–25.6 | 14.1 | 12.3–15.8 | |

| Worked last week | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 69.4 | 68.2–70.5 | 52.0 | 50.3–53.7 | 18.4 | 15.9–20.9 | |

| No | 27.3 | 26.2–28.5 | 45.7 | 44.0–47.4 | 77.1 | 74.3–79.9 | |

| Unknown | 3.3 | 2.8–3.8 | 2.4 | 1.8–2.9 | 4.5 | 3.0–6.1 | |

| Family FPL | <0.001 | ||||||

| >400% | 45.7 | 44.0–47.4 | 36.6 | 34.9–38.4 | 19.0 | 16.5–21.4 | |

| 200%–400% | 30.1 | 28.7–31.5 | 31.0 | 29.4–32.5 | 28.5 | 25.6–31.4 | |

| <200% | 24.2 | 22.8–25.7 | 32.4 | 30.5–34.3 | 52.5 | 49.1–55.9 | |

| Number of children in family | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 60.1 | 58.7–61.6 | 73.7 | 72.1–75.2 | 81.1 | 78.1–84.1 | |

| 1 | 16.1 | 15.0–17.3 | 11.9 | 10.7–13.1 | 11.3 | 8.8–13.9 | |

| 2 | 15.1 | 14.1–16.1 | 8.9 | 8.0–9.9 | 4.3 | 2.8–5.9 | |

| 3+ | 8.6 | 7.8–9.5 | 5.5 | 4.6–6.4 | 3.2 | 2.0–4.4 | |

| Interview date (2020) | 0.1443 | ||||||

| July–September | 50.7 | 48.9–52.4 | 48.6 | 46.6–50.5 | 50.7 | 47.3–54.0 | |

| October–December | 49.3 | 47.6–51.1 | 51.4 | 49.5–53.4 | 49.3 | 46.0–52.7 | |

| Census region | 0.003 | ||||||

| Northeast | 18.1 | 16.6–19.5 | 17.0 | 15.3–18.8 | 14.7 | 12.3–17.1 | |

| Midwest | 19.8 | 18.3–21.4 | 22.5 | 20.8–24.3 | 20.7 | 17.9–23.5 | |

| South | 37.8 | 35.8–39.8 | 37.0 | 34.8–39.1 | 43.2 | 39.4–46.9 | |

| West | 24.3 | 22.5–26.1 | 23.5 | 21.3–25.6 | 21.4 | 17.8–25.0 | |

| Urban/rural | <0.001 | ||||||

| Large central metro | 33.0 | 30.4–35.6 | 27.9 | 25.3–30.4 | 25.6 | 21.8–29.4 | |

| Large fringe metro | 26.4 | 23.8–29.0 | 22.7 | 20.2–25.2 | 19.7 | 16.5–22.9 | |

| Medium/small metro | 28.8 | 25.9–31.8 | 33.4 | 30.1–36.8 | 33.6 | 29.3–38.0 | |

| Nonmetropolitan | 11.8 | 10.4–13.2 | 16.0 | 14.3–17.7 | 21.1 | 18.0–24.1 | |

| Usual source of care | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 88.3 | 87.3–89.3 | 91.2 | 90–92.4 | 95.0 | 93.0–97.0 | |

| No | 11.7 | 10.7–12.7 | 8.8 | 7.6–10.0 | 5.0 | 3.0–7.0 | |

| Insurance coverage | <0.001 | ||||||

| Private | 68.7 | 67.2–70.2 | 54.2 | 52.2–56.1 | 34.7 | 31.7–37.7 | |

| Public/other | 18.2 | 17.0–19.3 | 35.1 | 33.3–36.9 | 60.7 | 57.5–63.8 | |

| None | 13.2 | 11.9–14.4 | 10.8 | 9.4–12.1 | 4.6 | 3.0–6.2 | |

| Ever smoker | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 27.7 | 26.6–28.9 | 41.9 | 40.1–43.7 | 49.3 | 46.1–52.5 | |

| No | 72.3 | 71.1–73.4 | 58.1 | 56.3–59.9 | 50.7 | 47.5–53.9 | |

| Drinking status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 16.1 | 14.8–17.3 | 12.7 | 11.4–14.1 | 21.0 | 18.0–23.9 | |

| Former | 13.2 | 12.4–14.1 | 19.6 | 18.3–20.9 | 34.4 | 31.3–37.5 | |

| Current | 70.7 | 69.3–72.1 | 67.7 | 65.9–69.4 | 44.7 | 41.3–48.0 | |

| Health status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Excellent | 33.5 | 32.3–34.8 | 13.2 | 12.0–14.4 | 3.2 | 2.2–4.2 | |

| Very good | 37.9 | 36.6–39.3 | 31.7 | 30.2–33.2 | 10.9 | 8.9–12.9 | |

| Good | 23.8 | 22.6–25 | 37.4 | 35.8–39.0 | 29.2 | 25.8–32.6 | |

| Fair/poor | 4.7 | 4.1–5.3 | 17.7 | 16.4–19.0 | 56.7 | 53.2–60.2 | |

| Number of chronic condition | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 62.7 | 61.5–64.0 | 38.6 | 36.9–40.3 | 20.0 | 17.0–23.0 | |

| 1 | 26.8 | 25.7–27.9 | 33.9 | 32.4–35.4 | 26.3 | 23.3–29.4 | |

| ≥2 | 10.5 | 9.7–11.2 | 27.5 | 26.0–29.0 | 53.7 | 50.3–57.1 | |

CI indicates confidence interval; FPL, federal poverty level; NH, non-Hispanic.

Table 2 presents the proportions of delayed and forgone medical care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic reported by disability status. Higher percentages of respondents with both severe and moderate disability reported delaying care than did people without a disability (severe=33.2%; moderate=27.5%; PWoD=20.0%, P<0.001). The same was true for forgone medical care (severe=26.6%; moderate=19.0%; PWoD=12.2%, P<0.001). When looking at the number of limitations, results also showed that respondents with ≥3 disabling limitations had the highest percentages of delayed medical care (35.2%) and forgone medical care (28.2%). By disability type, individuals with multiple limitations had the highest percentages of both delayed medical care (32.3%) and forgone medical care (24.5%), followed by respondents with only a cognitive limitation for delayed medical care (26.3%) and respondents with only mobility or complex activity limitation for forgone medical care (24.5%).

TABLE 2.

Respondents’ Delayed Care and Forgone Care by Disability Status

| Delayed Care | Forgone Care | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability Status | Weighted No. | No % (95% CI) | Yes % (95% CI) | P | No % (95% CI) | Yes % (95% CI) | P |

| Disability severity | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 148,102,805 | 80.0 (78.8–81.1) | 20.0 (18.9–21.2) | 87.8 (86.8–88.7) | 12.2 (11.3–13.2) | ||

| Moderate | 80,026,065 | 72.5 (71.0–74.1) | 27.5 (25.9–29.0) | 81.0 (79.6–82.4) | 19.0 (17.6–20.4) | ||

| Severe | 21,840,511 | 66.8 (63.9–69.7) | 33.2 (30.3–36.1) | 73.4 (70.6–76.2) | 26.6 (23.8–29.4) | ||

| Disability, by number of limitations | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 148,102,805 | 80.0 (78.8–81.1) | 20.0 (18.9–21.2) | 87.8 (86.8–88.7) | 12.2 (11.3–13.2) | ||

| 1 limitation | 51,563,290 | 74.8 (73.0–76.6) | 25.2 (23.4–27.0) | 83.2 (81.4–84.9) | 16.8 (15.1–18.6) | ||

| 2 limitations | 26,773,081 | 70.3 (67.4–73.1) | 29.7 (26.9–32.6) | 78.8 (76.3–81.3) | 21.2 (18.7–23.7) | ||

| ≥3 limitations | 23,530,206 | 64.8 (62.1–67.6) | 35.2 (32.4–37.9) | 71.8 (69.1–74.3) | 28.2 (25.6–30.9) | ||

| Disability, by type of limitation | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 148,102,805 | 80.0 (78.8–81.1) | 20.0 (18.9–21.2) | 87.8 (86.8–88.7) | 12.2 (11.3–13.2) | ||

| Hearing, only | 11,168,845 | 75.6 (72.1–79.0) | 24.4 (21.0–27.9) | 83.1 (80.0–86.2) | 16.9 (13.8–20.0) | ||

| Vision, only | 14,333,232 | 75.8 (72.3–79.3) | 24.2 (20.7–27.7) | 84.5 (81.5–87.4) | 15.5 (12.6–18.5) | ||

| Cognitive, only | 12,023,393 | 73.7 (69.2–78.1) | 26.3 (21.9–30.8) | 84.7 (80.7–88.7) | 15.3 (11.3–19.3) | ||

| Mobility/complex activity, only | 14,037,820 | 74.2 (70.8–77.6) | 25.8 (22.4–29.2) | 80.6 (77.5–83.7) | 19.4 (16.3–22.5) | ||

| ≥2 limitations | 50,303,287 | 67.7 (65.7–79.7) | 32.3 (30.3–34.3) | 75.5 (73.7–77.3) | 24.5 (22.7–26.3) | ||

CI indicates confidence interval.

Table 3 shows selected results from the 6 multivariable logistic regression models to examine the relationships of functional disability status with delayed medical care and forgone medical care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. When using 3-level disability severity as the independent variable, respondents with a moderate disability [delayed (OR=1.33, 95% CI=1.19, 1.49); forgone (OR=1.46, 95% CI=1.28, 1.67)] and a severe disability [delayed (OR=1.52, 95% CI=1.27, 1.83); forgone (OR=1.84, 95% CI=1.49, 2.27)] were more likely to report delayed medical care and forgone medical care compared with PWoD. When using the number of disabling limitations as the independent variable, respondents with each limitation count group were more likely to report the 2 health care access measures (all P<0.05) than respondents with none, with the strongest associations among those with ≥3 limitations for delayed medical care (OR=1.69, 95% CI=1.41, 2.03) and forgone medical care (OR=2.06, 95% CI=1.70, 2.51). Finally, when using disability type as the independent variable, individuals with only a cognitive limitation were significantly more likely than PWoD to report delayed medical care (OR=1.43, 95% CI=1.12, 1.82), whereas individuals with only a hearing limitation (OR=1.48, 95% CI=1.16, 1.90) and with only mobility or complex activity limitation (OR=1.38, 95% CI=1.10, 1.73) were more likely to report forgone medical care compared with PWoD.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Multivariable Logistic Regression Models of the Relationship Between Delayed Care and Forgone Care With Presence of Disability

| Delayed Care | Forgone Care | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR* | 95% CI | P | Adjusted P† | OR* | 95% CI | P | Adjusted P† | ||

| Disability severity | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Moderate | 1.33 | 1.19 | 1.49 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 1.46 | 1.28 | 1.67 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Severe | 1.52 | 1.27 | 1.83 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 1.84 | 1.49 | 2.27 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Disability, by number of limitations | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1 limitation | 1.23 | 1.09 | 1.40 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 1.33 | 1.14 | 1.55 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| 2 limitations | 1.49 | 1.26 | 1.75 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 1.66 | 1.38 | 1.98 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| ≥3 limitations | 1.69 | 1.41 | 2.03 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 2.06 | 1.70 | 2.51 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Disability, by type of limitation | ||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Hearing, only | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.49 | 0.091 | 0.094 | 1.48 | 1.16 | 1.90 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Vision, only | 1.21 | 0.98 | 1.49 | 0.071 | 0.076 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 1.56 | 0.092 | 0.102 |

| Cognitive, only | 1.43 | 1.12 | 1.82 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 1.23 | 0.89 | 1.71 | 0.205 | 0.203 |

| Mobility/complex activity, only | 1.11 | 0.91 | 1.36 | 0.315 | 0.315 | 1.38 | 1.10 | 1.73 | 0.006 | 0.007 |

| ≥2 limitations | 1.56 | 1.35 | 1.80 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 1.82 | 1.56 | 2.13 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

Adjusted for: age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, worked last week, number of children in family, family poverty level, interview date, census region, urbanization, usual source of care, insurance coverage, smoking status, drinking status, health status, and number of chronic conditions.

Used Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

CI indicates confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

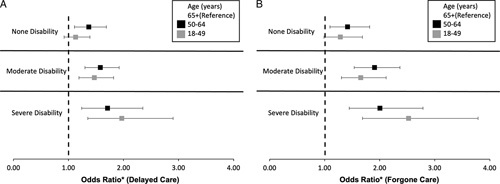

Figure 1 shows selected results from the multivariable logistic regression models with an interaction term (age* disability severity). Among respondents with a moderate disability, individuals aged 50–64 and 18–49 years were more likely to report delayed medical care (Fig. 1A) and forgone medical care (Fig. 1B) than their older counterparts. Similar patterns were found among the respondents with a severe disability (all P<0.05).

FIGURE 1.

Interaction effects of age and disability severity with delayed and forgone care in the multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models. *Adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, worked last week, number of children in family, family poverty level, interview date, census region, urbanization, usual source of care, insurance coverage, smoking status, drinking status, health status, and number of chronic conditions.

DISCUSSION

To understand the disparities in health care access during the early stage of the pandemic, we investigated the prevalence of delayed medical care and forgone medical care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among US adult populations by the presence of a disability. We found people with a severe disability experienced the highest percentages of delayed medical care (33.2%) and forgone medical care (26.6%) compared with people with a moderate disability (27.5% and 19%) and PWoD (20% and 12.2%). Multivariable logistic regression models showed that PWD had higher odds of reporting delayed or forgone medical care compared with PWoD, and the odds ratios increased as the severity of disability increased. In our subgroup analysis, individuals of working age (18–49 and 50–64 y) were more likely to report delayed and forgone medical care among PWD.

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected PWD compared with PWoD. Especially during the first wave of the pandemic, which hit nursing homes and assisted living facilities significantly, PWD were not only at higher risk of COVID-19 infection but also at a greater risk of poor COVID-19 outcomes and death.29–31 Our findings also suggested PWD were at higher risks of pandemic-related delays in and forgone medical care. The likelihoods of delayed and forgone medical care were significantly higher among those with a severe disability or a higher number of disabling limitations. Our observations of health care access disparities caused by the pandemic may be closely related to implementation of public health-related measures such as self-quarantine, isolation, and social distancing, which disrupted services provision for PWD.13 These included both direct health care services and other social services that may have affected health care–seeking behaviors among PWD, such as interpretation services for individuals with hearing limitations. Given the larger prevalence of lower socioeconomic status and poor health outcomes among PWD compared with PWoD,1–3 as well as the lack of disability-inclusiveness in COVID-19 pandemic responses,32 it is unsurprising that PWD experienced excessive challenges in accessing needed health care.

Our study reconfirmed that the associations between disability status and health care access may vary by disability subgroup. We found that individuals with only a cognitive limitation were more likely to report delayed medical care, whereas adults with only mobility/complex activity limitations were at a higher risk of forgone medical care than PWoD. Previous studies found these 2 disability subgroups were also especially at greater risks of adverse mental health care utilization and mental health outcomes.6,9,33 Therefore, these types of disabling limitations may be associated with the worst health conditions and highest barriers to seeking timely health care. This calls for further attention to improving access for PWD to timely and quality care during the pandemic and postpandemic period.

We also found that adults within the same disability severity group who were of different ages were affected differently by the COVID-19 pandemic. Working-age (≤65 y) PWD had a higher likelihood of reporting both delayed and forgone medical care than PWD aged older than or equal to 65 years. This finding is consistent with the patterns before the COVID-19 pandemic.3 A study by Reichard and colleagues34 found that having insurance coverage was the strongest predictor of avoiding delayed or forgone necessary health care (rather than other sociodemographic characteristics such as education, employment status, and poverty status) among working-age adults, especially for those with disabilities. In the current US health care system, working-age adults (including individuals with functional disabilities who are not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid) largely rely on employer-based health insurance coverage. Layoff, furlough, and job loss were more prevalent for those unable to work remotely from home during the initial COVID-19 pandemic.35 Loss of medical health coverage because of temporary or permanent job loss can instantly reduce an individual’s ability to pay for medical care, consequently leading to health care access problems among those affected. In contrast, older adults with Medicare coverage were significantly less likely to be affected by health insurance interruption during the pandemic. A study found Medicare beneficiaries may experience limited care access during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic but have improved care access over time.15 Another potential explanation could be the less perceived health care needs and evaluated needs among the younger groups compared with their elderly counterparts. Within the same disability group, younger adults have better health status in general, thus they may believe themselves less vulnerable to adverse health outcomes than older adults when delaying or forgoing care. In addition, as nonurgent health care resources were very limited during the initial stages of the pandemic, older adults with more chronic conditions may have been more likely to get appointments from health care providers based on evaluated needs.

Aligning with existing evidence,1–3,9 our study sample shows that PWD were older than PWoD; in addition, a higher percentage of PWD had more chronic conditions and reported fair/poor health status. These characteristics can increase their risk of serious adverse health outcomes, including severe morbidity and mortality if they contract the SARS-CoV-2 virus.11 Fear of contracting the virus may affect their decisions for seeking health care during the pandemic. The low supply of life-saving medical equipment in early 2020 may make them feel that they could not receive equitable health care due to their disability, which can further discourage their health care–seeking behaviors. Nevertheless, due to the “thinner margin of health” among PWD,34 they are at greater risk for potential complications and secondary conditions resulting from delayed or forgone needed health care. Therefore, it is critically important to ensure PWD have equal access to high-quality health care, regardless of whether it is related to COVID-19 or other types of needed care. To achieve this requires ongoing efforts from all of society to further reduce stigma and discrimination, ableism, and ageism against PWD.

The health care disparities observed for PWD during the pandemic possibly arise from deprivation in their social participation before the pandemic.36 Policymakers should strive to include the voice of PWD and enhance their effective and meaningful participation in emergency preparedness. Second, changes from the provider side will be also necessary.37 The low awareness of disability culture and health needs among health care providers has been well documented.38 Although the significant contributions and huge self-sacrifices of health care professionals in response to the pandemic should be acknowledged, the low level of disability cultural competence among health care professionals may create more unconscious bias and extra barriers for PWD when seeking health care during this time of limited human and materials resources. For instance, delivery of health care through telehealth was rapidly increased during the pandemic. However, PWD with certain disabling limitations may not be able to communicate with providers effectively through video calls, or some may not have access to stable internet or computer. This may have significant implications for health care utilization among PWD during the pandemic. Therefore, awareness-raising efforts from on-job training at the workplace are urgently needed. Further, incorporating disability cultural competence training in medical school curriculums may address these issues in the long term.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted with caution. First, early pandemic-related restrictions and policies varied from state to state in the United States. The NHIS public use file does not contain geographic information at the state or local level, but instead US census region; and the challenges in health care access among PWD may vary across states either before or during the time period studied. Second, we used binary outcome variables to measure difficulties in access to care, the 2 survey question items which were used to obtain the outcome measures were relatively vague and may be subject to differences in interpretation. Future studies with more specific health care utilization and/or health services type outcome measures may further help understand the disparities in health care access between PWD and PWoD. In addition, the self-reported delayed or forgone care may be influenced by the perceived needs of care,25 future studies based on evaluated needs could more accurately reflect the challenges in access to care. Third, the COVID-19-related items were only asked in quarters 3 and 4 of 2020. Considering the rapidly changing social environment in terms of the pandemic itself, COVID-19 vaccine and treatment developments, and policies in response to the pandemic over the past 2 years, our findings may only accurately reflect the situation in 2020. Thus, future studies with more recent data are warranted. Fourth, the self-reported survey data of the NHIS may suffer from recall bias. In addition, the overall relatively low response rate of the 2020 NHIS requires caution to interpret the prevalence estimates for delayed and forgone medical care caused by COVID-19. However, results from the multivariable logistic regression models dedicated to understanding differences between PWD and PWoD were less affected by this situation. Finally, due to the nature of the cross-sectional data for this study, results should be only interpreted as associations, rather than with any causal inference. To further investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic caused health care disparities between PWD and PWoD, quasi-experimental studies with longitudinal data are preferred.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this nationally representative survey study suggest that PWD were more likely to experience COVID-19-related delays in and forgone medical care compared with PWoD. The more severe and higher frequency of disabling limitations were associated with higher degrees of delayed and forgone medical care. Policymakers need to develop disability-inclusive (eg, including PWD in preparedness and response planning) responses to public health emergencies to reduce these health care disparities.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Zhigang Xie, Email: xiezhigang@ufl.edu.

Young-Rock Hong, Email: youngrock.h@phhp.ufl.edu.

Rebecca Tanner, Email: rtanner@phhp.ufl.edu.

Nicole M. Marlow, Email: marlownm@phhp.ufl.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Disability and health. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 2.United States Census Bureau. Newsroom archive. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability impacts all of us. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 4.Mahmoudi E, Meade MA. Disparities in access to health care among adults with physical disabilities: analysis of a representative national sample for a ten-year period. Disabil Health J. 2015;8:182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henning-Smith C, McAlpine D, Shippee T, et al. Delayed and unmet need for medical care among publicly insured adults with disabilities. Med Care. 2013;51:1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Z, Tanner R, Striley CL, et al. Association of functional disability with mental health services use and perceived unmet needs for mental health care among adults with serious mental illness. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horner-Johnson W, Dobbertin K, Lee JC, et al. Expert Panel on Disability and Health Disparities. Disparities in health care access and receipt of preventive services by disability type: analysis of the medical expenditure panel survey. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:1980–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichard A, Stolzle H, Fox MH. Health disparities among adults with physical disabilities or cognitive limitations compared to individuals with no disabilities in the United States. Disabil Health J. 2011;4:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61:852–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senjam SS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people living with visual disability. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1367–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashemi G, Kuper H, Wickenden M. SDGs, inclusive health and the path to universal health coverage. Disability and the Global South. 2017;4:1088–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuper H, Banks LM, Bright T, et al. Disability-inclusive COVID-19 response: What it is, why it is important and what we can learn from the United Kingdom’s response. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jesus TS, Bhattacharjya S, Papadimitriou C, et al. Lockdown-related disparities experienced by people with disabilities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review with thematic analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson KE, McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, et al. Reports of forgone medical care among US adults during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2034882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Stimpson JP. Trends in self-reported forgone medical care among medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. InJAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:e214299–e214299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czeisler ME, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns—United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner P, Tur-Sinai A. Prevalence and correlates of forgone care among adult Israeli Jews: a survey conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0260399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtenay K, Perera B. COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: impacts of a pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37:231–236; Epub 2020 May 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabatello M, Burke TB, McDonald KE, et al. Disability, ethics, and health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1523–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright C, Steinway C, Jan S. The crisis close at hand: how COVID-19 challenges long-term care planning for adults with intellectual disability. Health Equity. 2020;4:247–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavanagh A, Hatton C, Stancliffe RJ, et al. Health and healthcare for people with disabilities in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil Health J. 2022;15:101171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Kim J. A country report: Impact of COVID-19 and inequity of health on south Korea’s disabled community during a pandemic. Disabil Soc. 2020;35:1514–1519. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2020. Public-use data file and documentation. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 24.Goyat R, Vyas A, Sambamoorthi U. Racial/ethnic disparities in disability prevalence. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3:635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE transactions on automatic control. 1974;19:716–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verbrugge LM, Yang LS. Aging with disability and disability with aging. J Disabil Policy Stud.. 2002;12:253–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verhoeven KJ, Simonsen KL, McIntyre LM. Implementing false discovery rate control: increasing your power. Oikos. 2005;108:643–647. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chidambaram P, Garfield R. Nursing homes experienced steeper increase in covid-19 cases and deaths in august 2021 than the rest of the country. Available at: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/nursing-homes-experienced-steeper-increase-in-covid-19-cases-and-deaths-in-august-2021-than-the-rest-of-the-country/. Accessed February 17, 2022.

- 30.Landes SD, Turk MA, Formica MK, et al. COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disabil Health J. 2020;13:100969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey G, Kensington S. The National Disability Insurance Scheme and COVID-19: a collision course. Med J Aust. 2020;213:141–141.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage R, Nellums LB. The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Z, Tanner R, Striley CL, et al. Association of functional disability and treatment modalities with perceived effectiveness of treatment among adults with depression: a cross-sectional study. Disabil Health J. 2022;15:101264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichard A, Stransky M, Phillips K, et al. Prevalence and reasons for delaying and foregoing necessary care by the presence and type of disability among working-age adults. Disabil Health J. 2017;10:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groshen EL. COVID-19’s impact on the U.S. labor market as of September 2020. Bus Econ. 2020;55:213–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Cruz M, Banerjee D. ‘An invisible human rights crisis’: The marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic —an advocacy review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doebrich A, Quirici M, Lunsford C. COVID-19 and the need for disability conscious medical education, training, and practice. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13:393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marlow NM, Samuels SK, Jo A, et al. Patient-provider communication quality for persons with disabilities: a cross-sectional analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey. Disabil Health J. 2019;12:732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]