Abstract

Objectives

In the Netherlands, a case of euthanasia of an incompetent patient with dementia and an advance euthanasia directive (AED) caused great societal unrest and led to a petition signed by more than 450 physicians. In this paper, we investigate these physicians’ reasons and underlying motives for supporting the ‘no sneaky euthanasia’ petition, with the aim of gaining insight into the dilemmas experienced and to map out topics in need of further guidance.

Methods

Twelve in-depth interviews were conducted with physicians recruited via the webpage ‘no sneaky euthanasia’. General topics discussed were: reasons for signing the petition, the possibilities of euthanasia in incompetent patients and views on good end-of-life care. Data were interpreted using thematic content analysis and the framework method.

Results

Reasons for supporting the petition are dilemmas concerning ‘sneaky euthanasia’, the over-simplified societal debate, physicians’ personal moral boundaries and the growing pressure on physicians. Analysis revealed three underlying motives: aspects of handling a euthanasia request based on an AED, good end-of-life care and the doctor as a human being.

Conclusions

Although one of the main reasons for participants to support the petition was the opposition to ‘sneaky euthanasia’, our results show a broader scope of reasons. This includes their experience of growing pressure to comply with AEDs, forcing them to cross personal boundaries. The underlying motives are related to moral dilemmas around patient autonomy emerging in cases of decision-making disabilities in advanced dementia. To avoid uncertainty regarding patients’ wishes, physicians express their need for reciprocal communication.

Keywords: dementia, euthanasia, advance directive, qualitative research, end-of-life care, older people

Key Points

Pressure on physicians to provide euthanasia based on an advance directive is growing.

Euthanasia based on an advance euthanasia directive (AED) in the case of advanced dementia touches on the personal boundaries of physicians.

Physicians experience moral dilemmas around patient autonomy in cases of decision-making disabilities in advanced dementia.

Reciprocal communication with patients is highly preferable in dealing with euthanasia requests in advanced dementia.

Society would benefit from general education on end-of-life care in advanced dementia.

Introduction

In 2002, the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act was introduced in Dutch law, allowing, but never obliging, physicians to perform euthanasia or physician assisted suicide (EAS) without prosecution, if they follow the due care criteria [1, 2] (Table 1) and report the case to a Regional Euthanasia Review Committee (RERC) [3, 4]. The law was predominantly the codification of the previously existing euthanasia practice in competent patients (with dementia) [5]. The due care criteria were constructed based on a broad professional and moral consensus, among physicians and in society, on self-determination and the social-cultural view on dignified dying [3].

Table 1.

Due care criteria [2]

| The Dutch statutory due care criteria for euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide as stated in the Euthanasia law |

| 1. The patient’s request should be voluntary and well considered |

| 2. The patient’s suffering should be unbearable and without prospect of improvement |

| 3. The patient should be informed about their situation and prospects |

| 4. There are no reasonable alternatives in the patient’s situation |

| 5. At least one other, independent physician, should be consulted and should give a written opinion on whether the due care criteria set out in 1–4 have been fulfilled |

| 6. The termination of patient’s life should be performed with due medical care and attention |

With the enactment of the law, the possibility to allow euthanasia for incompetent patients with dementia, was realised in article 2.2, stating that “the oral request for EAS can be replaced by a written advance euthanasia directive (AED), provided that the due care criteria are met ‘in a corresponding way’” [1]. Herewith, the legislator was taking a step beyond existing practice. Although EAS in general has wide acceptance in the Netherlands [6], euthanasia in dementia based on an AED is rarely performed [7], and (its ethical justification) remains a much-debated topic [4, 8, 9].

In 2016, an elderly care physician (ECP) [10, 11] performed euthanasia in an incompetent patient with advanced dementia based on an AED (case description; Appendix 1 available in Age and Ageing online) [12, 13]. In this case, the RERC concluded that the due care criteria (in particular criteria 1 and 6) were not met, mainly because patients’ AED was open to multiple interpretation and the RERC disagreed with the interpretation made by the physician. As there was no oral euthanasia request at the time of euthanasia performance, and the AED was not sufficiently clear, the RERC concluded there was no (unequivocal) voluntary and well-considered request. In addition, the RERC felt the use of sedatives prior to the euthanasia was questionable since this made communication with the patient regarding the imminent termination of her life impossible. Also, the physical reaction of the patient to the administration of the medication was interpreted by the RECR as a possible act of resistance to euthanasia [12–15].

This case fuelled the societal debate and caused much unrest among physicians, which resulted in a page ad published in 2017 in all national newspapers (Table 2), stating a strong disapproval of what was called ‘sneaky euthanasia’ [16–18] referring to euthanasia based on an AED in cases in which the patient does not realise what is happening to him. The ad was transformed in a website-petition, which was supported by over 450 physicians.

Table 2.

Petition ‘no sneaky euthanasia’ [16]

|

Opinion

Volkskrant, 21 January 2017, by Boudewijn Chabot (psychiatrist) and on behalf of 33 other physicians |

| Never kill a defenceless person who does not realise what is happening to him. The undersigned believe that physicians should collectively guard the moral frontier that no euthanasia should be performed on defenceless patients who no longer realise what is happening to them. Meaning that they do not realise they are getting an injection that ends life, c.q. that will kill them. |

In this article we investigate the reasons and (underlying) motives for physicians to support the petition ‘no sneaky euthanasia in dementia cases’. The aim of the study is to gain more insight into the experienced dilemmas of the physicians who supported the petition, as well as to identify topics in need for more guidance. Following legal investigation (2018–2019) the Dutch Supreme Court ruled on the above mentioned case after our data-collection. We will reflect upon whether and how this first and so far only ruling on the Dutch Euthanasia Law contributes to the objections and concerns of the contributors of the petition in the discussion.

Methods

Design

A qualitative interview study was performed with Dutch physicians who supported the ‘no sneaky euthanasia’ petition [16]. To present the findings, the Consolidated Criteria for reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) checklist was followed [21].

Participants

Participants were purposefully selected by gender, profession and additional expertise on the subject from the open name-list published on the webpage of ‘no sneaky euthanasia’, which holds 464 names [16]. The sole exclusion criterion was retirement (33 physicians). We started with the invitation of thirty-eight physicians, based on available contact details. Fifteen of these thirty-eight invited physicians agreed to participate (2 declined, 21 no reaction). After the first eight interviews no new themes were found. We performed an additional four interviews to affirm this. Data saturation was reached and confirmed after twelve interviews.

Data collection

Twelve semi-structured, in-depth interviews were held between April and July 2019, based on a predefined topic-list (Table 3). Besides the reason for supporting the petition, the following topics were discussed: (i) the possibilities of euthanasia in case of incompetent patients with dementia and (ii) views on good end-of-life care. All interviews were conducted by the first author (DOC), tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim et literatim. Participants’ characteristics (Table 3) were collected and field notes (background information, non-verbal communication) were made. All participants responded to the member check: a one-page summary of their interview. Seven participants made small additions and corrections.

Table 3.

Key items topic-list

| Topics | Sub-topics |

|---|---|

| The ‘no sneaky euthanasia’ petition | Reasons for signing the petition |

| The applicability of the due care criteria to patients with dementia | |

| Participant’s vision on end-of-life care | |

| Advance euthanasia directives | Frequency of appearance |

| The involvement of stakeholders | |

| Content of AEDa | |

| Reason to refrain from performing euthanasia based on an AEDa | |

| The request for euthanasia | Experience with requests for euthanasia |

| The involvement of stakeholders | |

| Voluntary and well considered request | |

| Unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement | |

| Reasonable alternative treatments | |

| The performance of euthanasia | Experience with performance of euthanasia |

| Experienced dilemmas | |

| Physician’s duty to inform the patient | |

| Verbal or physical resistance during the performance | |

| The use of sedative premedication | |

| The emotional burden | Increasing pressure on physicians |

| The emotional burden on physicians |

This topic-list was composed by the research team (all authors) and based on scientific and grey literature, as well as the public debate and national news items [19]. On account of the iterative process of data collection, the topic-list was revised five times.

AED = advance euthanasia directive.

Data analysis

A cyclical and iterative process was used during data collection and analysis, followed by an application of the constant comparison method. All interviews were read, re-read and coded by the first author (DOC). The first five interviews were double coded by a research assistant (JvE) and discussed within the research team. Codes were based on small text fragments, forming a code tree (Appendix 2 available in Age and Ageing online), which was adjusted multiple times during the process. Consensus on codes and categories was reached by first (DOC), second author (MEdB) and research assistant (JvE). Thematic content analysis and the framework method was used to interpret all data [19,22,23]. The findings were organised into themes and discussed within the research team for further interpretation and verification. Atlas.ti 7&8 (coding) and Microsoft Excel (framework matrix; Appendix 3 available in Age and Ageing online) supported data analysis [24]. An audit trail was kept throughout the entire process.

Ethics

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of Amsterdam UMC, location VU University Medical Centre, has confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) does not apply to the study protocol (2019.018). Participation was voluntary and all participants signed an informed consent form after receiving information on the study (verbally and in writing). All data have been pseudonymised.

Results

In total five general practitioners (GPs) and seven ECPs were interviewed (Table 4). Ten participants declared themselves willing to perform euthanasia in competent patients with dementia, of which five had actual experience. Two ECPs had fundamental objections against euthanasia, in general or in patients with dementia.

Table 4.

Characteristics of participants

| Participant (P) | Sex | Age group | Personal life philosophy | Profession | Additional profession | Other work activities | Years of work experience in current profession | Experience with euthanasia | Experience with euthanasia in patients with dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | M | 65-74 | None | ECPa | SCEN-physicianc, physician Euthanasia Expertise Centre | Additional education in Philosophy | 37 | Yes | Yes, in competent patients |

| II | F | 55-64 | None | ECP | Additional education in palliative care | 34 | Yes | No | |

| III | M | 65-74 | None | GPb | SCEN-physician | 38 | Yes | No | |

| IV | M | 55-64 | None | GP | SCEN-physician | 30 | Yes | Yes, in competent patients | |

| V | M | 65-74 | Levinas philosophy | ECP | Additional education in palliative care and primary care, consultant palliative care | 40 | Yes | No | |

| VI | M | 55-64 | None | GP | Additional education in palliative care | 25 | Yes | Yes, in competent patients | |

| VII | M | 55-64 | Christian (non-practicing) | GP | Additional education in care for older patients | 43 | Yes | No (fundamental objections) | |

| VIII | M | 65-74 | Christian (non-practicing) | ECP | GP, social geriatrician | Additional education in psycho-geriatrics | 4 | No (fundamental objections) | No |

| IX | F | 45-54 | None | ECP | Additional education in palliative care | 23 | Yes | No | |

| X | F | 45-54 | Christian | ECP | Additional education in palliative care | 24 | Yes | Yes, in competent patients | |

| XI | F | 45-54 | Humanist | ECP | Additional education in palliative care, consultant palliative team, consultant CCEd, member of PaTz-teame | 15 | Yes | No | |

| XII | M | 65-74 | Christian (non-practicing) | GP | SCEN-physician | Additional education in philosophy, member of the regional Euthanasia Review Committee | 45 | Yes | Yes, in competent patients |

ECP = elderly care physician

GP = general practitioner

SCEN = support and consultation for Euthanasia in the Netherlands [20]

CCE = centre for consultation and expertise (main focus: behavioural problems in patients with severe dementia)

PaTz-team = member of palliative care at home team.

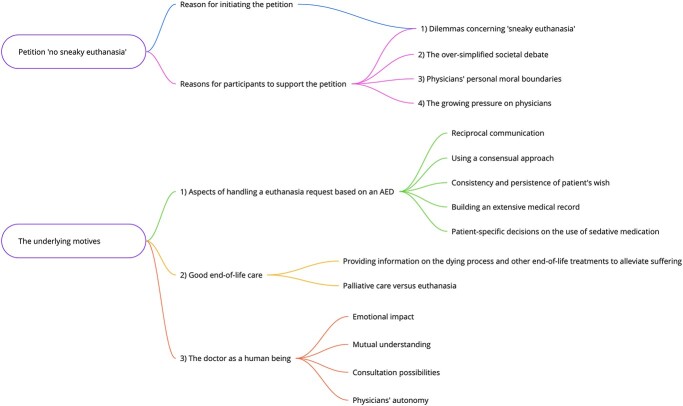

Overall, physicians’ reflections on why they signed the petition were found to be rather broad and beyond the main reason for initiating the petition (the opposition to ‘sneaky euthanasia’). We identified three additional reasons for supporting the petition. In-depth analysis revealed three underlying motives contributing to these reasons (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons and underlying motives for supporting the petition.

Reasons for supporting the petition

Dilemmas concerning ‘sneaky euthanasia’

Physicians were opposed to the performance of euthanasia in patients who no longer realise what is happening to them. This opposition derives from the difficulty physicians experience in performing euthanasia in incompetent patients:

‘I believe that the explicit elimination of the will, by which we sideline someone as a human being, and then kill him, [silence] it worries me’ (pI).

Since most of these patients are impaired in (verbal) communication, physicians face moral dilemmas concerning patient autonomy:

‘When does autonomy end and when do you start making decisions regarding someone?’ (pVII).

This lack of (verbal) communication strikes as acting ‘secretive’ (pI) to physicians.

The over-simplified societal debate

The second reason was given by physicians who did not engage with the societal debate on euthanasia and end-of-life care. Physicians felt this debate is dominated by a ‘black and white’ (pVI) approach, whereby euthanasia is (too) easily linked to a ‘good death’ (pVI) and a solution for human suffering. Physicians also had difficulties with the public’s opinion moving towards ‘. . .if you’re going to sign something [an AED], then it should be done’ (pX). Participants argue the reality of euthanasia and end-of-life care in dementia is more complex and ‘dissenting opinions should be heard’ (pX). They emphasise the question lying behind a request for euthanasia is often fear for suffering. Despite the fact that life with dementia is ‘of course very hard’(pVII), they believe that the process of dying is part of life. These physicians feel the debate should be focused more on their view, which entails:

‘Euthanasia [should be used] as an emergency solution. And not a preferred option’ (pXI).

Physicians’ personal moral boundaries

The third reason is related to the concern that physicians’ personal moral boundaries are at stake. Physicians emphasise how moral conflicts sometimes lead to the crossing of personal boundaries:

‘It is extremely difficult […] to arrive at the choice for euthanasia in a conversation with a patient. If you can no longer consult with the person I couldn’t do it.’ (pII).

Gaining respect for such boundaries is not always easy:

‘[People] are very emotional during that discussion. ‘Okay, you demand your autonomy, but do you also respect the autonomy of a physician who says up to here and no further’’ (pXI).

For some this crossing of personal boundaries leads to emotional distress, with potentially far-reaching consequences:

‘If you have to do it [performing euthanasia], while you can’t completely convince yourself that you’re doing the right thing [. . .] because you can’t ask the person anymore. Then I think I’m no longer a contributor to my profession. [. . .] Then, I have to stop.’ (pXI).

The growing pressure on physicians

The final reason was participants’ wish to resist the pressures of society with regard to euthanasia requests:

‘People [. . .] assume that it’s simply a right and something the physician must do.’ (pII).

They worry about the trend for the public to [incorrectly] assume that an AED is a binding contract, which obliges physicians to carry out euthanasia:

‘If you’re going to sign something [an AED], then it should be done.’ (pX).

Underlying motives

Aspects of handling a euthanasia request based on an AED

The following five aspects are, according to the participants, important in order to allow for the performance of euthanasia in an incompetent patient with dementia based on an AED.

Reciprocal communication

Participants identify some form of reciprocal communication as essential in dealing with euthanasia requests. This reciprocal communication is essential in order to achieve ‘a clear conscious’ (pVII) when performing euthanasia, and to be able to ‘imagine how it [the patient’s unbearable suffering] feels’ (pVIII). This reciprocal communication can be achieved by means of a confirmatory question (i.e. ‘Do you want me to perform euthanasia, which means I will give you an injection that causes you to die’?):

‘I think that the most important thing you have [as a person] is that you should be able to answer that [the confirmatory question] in a positive way, that shouldn’t be up to someone else’. (pVIII).

However, reaching such a reciprocal patient-physician conversation is complicated in patients with advanced dementia:

‘[The patient] does not understand the context in which the euthanasia is performed. So, can’t say a heartfelt “yes” to it either’. (pVIII).

Lack of communication leads to interpretation, which is for many physicians not desirable:

‘If someone can’t tell me that [the reason for their euthanasia wish] then I have to interpret it. How I interpret it is then decisive in whether it can or cannot be done’. (pIX).

When no reciprocal communication can be reached, this poses moral dilemmas on physicians:

‘We still have to come up with a solution for that or we have to decide that it [euthanasia] cannot be done’. (pXII).

Using a consensual approach

If reciprocal communication with the patient is impossible, physicians suggest making use of ‘a consensual assessment’ (pXII). The central aim of such a consensual approach is to reach consensus, with both care professionals and family members, on the due care criteria:

‘That you say, yes, indeed, […] we all agree that now is the time [for euthanasia] even though it may not seem like it [consensus on all due care criteria] is 100% legally verifiable because there is still room for subjectivity’ (pXII).

In addition, it would be of great value to physicians if they could include an early judgement of the RERC in their consensual assessment:

‘A prior [assessment], perhaps not obligatory, but if it were an option, to be able to provide further consultation in complex cases’ (pVI).

Consistency and persistence of patient’s wish

Physicians report uncertainty regarding the consistency and persistence of patient’s wishes for euthanasia:

‘A lot of people saying “suppose… then…[I want euthanasia]”. But, it is not often that people actually follow through with it [euthanasia] once the moment is there. I do see boundaries shifting, .. until at some point it [wish for euthanasia] is no longer an issue’ (pIV).

This uncertainty poses moral dilemmas in how to interpret the euthanasia wish as laid down in the AED, especially when no reciprocal communication with the incompetent patient is possible and the interpretation needs to be done by the physician. Therefore, a certain degree of consistency and persistence of the euthanasia request is seen as fundamental:

‘[A euthanasia request should] have some clear continuity in time to make clear that it is an unequivocal, […] persistent wish’. (pIV).

Building an extensive medical record

In addition to the AED, the existence of a rich medical record is stressed as important:

‘The physician’s record keeping is very important, as [it] is the independent assessment of the decisional capacity’. (pIV).

Such an extensive medical record should include a report of advance care planning [25], as well as documentation on the consultation of experts when dealing with treatable causes of discomfort. Besides, physicians find it crucial for patients to formulate their AED ‘as explicitly as possible and in [their] own words’ (pIV). Participants describe that patients incorrectly assume their euthanasia request ‘is settled’ (pX) when having a signed statement, while the majority of physicians approach AEDs as ‘a document to start a conversation’ (pVI).

Patient-specific decisions on the use of sedative medication

Opinions regarding the use of sedatives prior to the euthanasia procedure differ among participants. The principle of its use (to reduce symptoms of stress and anxiety) are not disputed:

‘To give something beforehand to put someone to sleep […], I think it is very justifiable to be honest […]. A form of reducing […] or alleviating suffering’ (pIV).

Uncertainty in terms of ambiguous verbal or physical expressions of the incompetent patient during the euthanasia performance leads to dilemmas in the decision on whether or not the use of sedatives is justified:

‘You are going to interpret that [resistance]. Is it because he didn’t want it [euthanasia]? Or is it because he didn’t understand what was going to happen?’ (pIX).

Opinions on the use of sedatives to prevent resistance are mixed. Some physicians reason:

‘My justification would be:, “should I find myself in such a situation [of physical resistance of a patient], then you should treat that [the resistance] as if it were a thing you should prevent”’. (pXII).

Others express an opposite opinion:

‘To prevent that you’ll have a struggle, […] I don’t think you should’. (pVIII).

According to the participants, decisions on the use of sedatives should be made tailored to the individual situation and thus should be prevented from becoming ‘normal practice’:

‘Don’t go normalizing it. Don’t go making some kind of guideline for it either. No, that’s a very negative development’. (pVI).

Good end-of-life care

The second underlying motive voiced by the participants is the (need for more attention to the) importance of good end-of-life care. According to the physicians, good end-of-life care starts with providing information to patients, family members and fellow physicians. This includes information about palliative care, while its limitations are recognised.

Providing information on the dying process and other end-of-life treatments to alleviate suffering

Participants are of the opinion that alternative palliative treatment options to alleviate the unbearable suffering which led to the (request for euthanasia based on an) AED should be part of end-of-life conversations with patients and family members. According to the participants, patients and family members, and sometimes even fellow physicians, lack such knowledge. Furthermore, a lack of understanding, in society in general and in ‘young physicians too’ (pX), of the normal dying-process is experienced.

Palliative care versus euthanasia

Participants indicate the importance of good palliative care, but also recognise that palliative care cannot provide the answer to all end-of-life questions, such as when dealing with extreme behavioural problems associated with advanced dementia. In these kinds of situations participants consider palliative care as insufficient. According to some physicians, sedation can be used in such situations ‘even if it leads to less eating and drinking and therefore speeds up the process’ (pX), while others refer to this specific practice of palliative sedation as ‘a slippery slope’ (pIX).

The doctor as a human being

Physicians stress the importance of their own personal role as a doctor within euthanasia procedures. Some argue euthanasia is developing from ‘a non-normal medical intervention’ (pVIII) into ‘normal medical practice and part of the duty of good doctoring’. (pVIII). We distinguish four relevant subthemes.

Emotional impact

Performing euthanasia is experienced as ‘tough’ (pXI). Euthanasia performance affects sleeping behaviour and stress-levels. A lack of awareness of this emotional impact of euthanasia on physicians is reported:

‘They [patient and family] had no idea of the impact it had on me. […] They really thought: “it is common for a physician”’. (pII).

However, emotional stress decreases when patients or family members express gratitude:

‘That lady was so grateful. It’s a kind of reward that I take with me. It does make it easier. Not to do it, but to be at peace with it’. (pII).

Mutual understanding

Mutual understanding, which is described as achieving a shared insight between patient and physician, is experienced as beneficial to dealing with feelings of stress and tension:

‘That feeling of coming to a conclusion together, that this is the only option’ (pII).

The understanding of each other’s perspective is seen as a core element of this mutual understanding:

‘We were able to take each other along. She had questions, I had questions, and we came to an agreement at some point’. (pVII).

Consultation possibilities

Another way to manage the emotional impact of dealing with euthanasia is discussing cases with colleagues:

‘It is a form of support’. (pII).

Physicians, especially general practitioners, perceive there are limited possibilities to consult experts in cases of euthanasia in incompetent patients with dementia.

Physicians’ autonomy

Participants appreciate the grey area in the law which gives physicians the opportunity to remain in control and make case-dependent decisions as medical experts. Not all can or should be regulated by law. Too much clarification of the grey area possibly leads to the detriment of their autonomy:

‘That’s also a plea, to have that grey area, that it continues to exist’. (pVI).

An additional motive for this plea is the belief that such a grey area contributes to the societal debate:

‘It improves the conversation […] and perhaps even the debate. Because you are going to talk about “when does autonomy end and when do you start making decisions regarding someone”?’ (pVII).

Physicians argue for such a debate to be held among physicians and in society, not in court.

Discussion

This article provides an overview of the reasons and underlying motives of physicians to support the petition ‘no sneaky euthanasia in dementia’ (Table 2) [16]. Remarkable, and unexpected to us as researchers, is the broad scope of reasons which were presented by the participants. Beyond reasons more in line with the initiation of the petition, participants contemplated extensively on broader reasons and were very nuanced in the discussion of them. We suspect that the mentioned case of euthanasia based on an AED (Appendix 1 available in Age and Ageing online) functioned as ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’, resulting in the petition being an easy way for physicians to vent their dissatisfaction with the development of the Dutch euthanasia practice. In support of this speculation are the matching statements made by several participants on their way out after the official interview, a known phenomenon referred to as the “doorknob phenomenon” [26, 27].

In addition to the expected opposition to euthanasia based on an AED without informing the patient (the opposition to ‘sneaky euthanasia’) as a main reason for physicians to support the petition, we identified three additional reasons: ‘the over-simplified societal debate’, ‘physicians’ personal moral boundaries’ and ‘the growing pressure on physicians’. After in-depth analysis, three underlying motives to these reasons were identified, each with several subthemes (Figure 1). These motives are: ‘the aspects of handling a euthanasia request based on an AED’, ‘good end-of-life care’ and ‘the doctor as a human being’. Several of the interviewed physicians who supported the petition were not completely opposed to euthanasia based on an AED or opposed to the use of sedative medication, provided that this medication was given to prevent anxiety before the actual performance euthanasia.

The findings endorse those of our previous literature review [28] which supports the doctors’ view that, within the context of good end-of-life care, euthanasia should not be classified as ‘normal medical practice’. It should, rather than a ‘preferred option, be considered as a ‘last resort’. Participants also considered that society associates severe dementia too easily with unbearable suffering, and hence consider euthanasia to be a legitimate and desirable euthanasia [28]. In line with previous research it was stressed that society in general would benefit from education about the dying process and (alternative) palliative treatment options to alleviate the unbearable suffering of patients with dementia [29–33], with specific attention to the treatment of severe behavioural problems in advanced dementia, which continues to be challenging [34, 35].

In handling complex EAS requests, our results highlight the importance of using a ‘consensual approach’ [32, 36]. Before performing euthanasia, it is crucial for our participants (to try) to achieve ‘reciprocal communication’ with their patient. This ‘reciprocal communication’ consists of being able to have a conversation with a certain degree of reciprocity. Physicians underline the importance of having the possibility to verify whether their patient still supports their AED, as people are known to adapt to new situations and tend to change or postpone their wish for euthanasia [4, 8, 37]. In addition, prior literature on the subject shows that physicians find it also difficult to assess the due care criterion ‘unbearable suffering with no future improvement’ in an incompetent patient with dementia [38]. Furthermore, the participants indicate the need for this ‘reciprocal communication’ in order to achieve a shared insight with their patient, which is referred to as ‘mutual understanding’ [39]. For example, as previously mentioned [39], knowledge of patients’ perspective on the past, present and future is essential in understanding their perception of unbearable suffering (the 2nd due care criteria of the Dutch euthanasia law). ‘Reciprocal communication’ and the ensuing ‘mutual understanding’ therefore require a sufficient level of competence of the patient. However, ‘reciprocal communication’ does not necessarily lead to ‘mutual understanding’ between patient and physician. ‘Mutual understanding’ entails being able to hear and accept each other’s point of view, and having respect for each other’s norms and values. When reciprocal communication is indeed possible but both parties cannot reach understanding of each other’s point of view, mutual understanding cannot be accomplished. Without this mutual understanding the performance of euthanasia is putting a substantial amount of emotional burden on physicians. In cases in which reciprocal communication, and thus mutual understanding, is no longer possible due to the fact that there is no possibility to communicate with the patient in any form, some participants argue for a ‘consensual approach’ as an alternative to the ‘reciprocal communication’. This ‘consensual approach’ entails an approach by which consensus can be reached in consultation with third parties, such as other care professionals and family members, provided an extensive and well-documented preparation process has been completed.

Concern is raised by the participants about the increasing influence of patient autonomy. Prior to the law, the euthanasia practice was based on the principles of respect for autonomy and compassion, but remained limited to competent patients and current autonomy [5]. Article 2.2 of the law extended this autonomy, beyond existing practice, to incompetent patients by adding AEDs [1]. This causes pressure on physicians and dilemmas around respecting the expressions of the current incompetent patient with dementia which may conflict with their wishes laid down in their AED [32, 33]. Physicians are confronted with a huge responsibility in this respect, an issue which remains underexposed in the euthanasia debate according to the participants in our study. They fear a scenario in which physicians are pressured to execute AEDs, and state: ‘the law should regulate a practice, not shape it’. Further, they experience additional pressure from people who perceive an AED as a binding contract for euthanasia [32, 40]. Participants rather use AEDs as a document supporting doctor-patient communication, and highlight their struggles with moral boundaries and decreasing respect for their autonomy. In line with previous research [32, 41–44], participants express the need to set personal and professional moral boundaries regarding euthanasia based on an AED. Against this background, participants embrace the ‘grey area’ in the current law, as it provides leeway to retain their (professional) physician autonomy in decision-making.

Reflections on the outcome of the legal investigation

The Supreme Court’s ruling acquitted the physician involved of all charges, which means her actions were within legal norms. The same ruling explained several premises with regard to the fulfilment of the due care requirements [12]. Although the Court’s ruling mentions that there may be ‘circumstances in which a request cannot be granted’ (such as ‘behavior or verbal expressions’ inferring the patient’s actual condition does not match the one provided for in the AED) and that the ‘requirement of unbearable suffering in particular requires special attention in cases of advanced dementia’, no further guidance on these points is provided. In addition, more leeway is given to physicians by including that the physician has ‘room to interpret the written request’ and may ‘administer medication in advance’ in case the physician considers ‘irrational or unpredictable behaviour’ of the patient. Reflecting on this outcome, the chairman of the Royal Dutch Medical Association concluded that this Court’s ruling ‘does not end all the dilemmas that faced physicians’, and rather ‘puts an extra burden on the physician’. Put differently: a huge responsibility is placed on physicians without providing guidance on how to deal with the current expressions of a patient with dementia deemed to be incompetent. In this context it is surprising that in the judgements of the Supreme Court no explicit reference is made to fundamental rights [45], such as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) [46] or the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [47], of which the latter was adopted after the Dutch Euthanasia law [1]. Although the Euthanasia law is thought to be generally consistent with these conventions, reference to some of its treaty provisions might have been in support to the concerns of the physicians who signed the petition ‘no sneaky euthanasia’ [16], and deserves further exploration. For example, the emphasis of the CRPD on the own will and preferences of people with decision-making disabilities and the concept of supportive decision-making supports the concerns of physicians with regard to sidelining the expression of people with advanced dementia in relation to euthanasia based on an AED.

Strength and limitations

The qualitative design of this study allowed for an in-depth analysis of underexposed, complex and ambivalent topic within the euthanasia debate. Careful qualitative data analysis, and use of the COREQ checklist, added to our study’s internal validity [21]. Reliability of research findings was increased by involvement of multiple researchers [48]. Although this study focuses solely on the Dutch euthanasia practice, our findings may also foster end-of-life debates in other countries involved in (debates on) euthanasia practice.

Recommendations for clinical practice and future research

Although most of the dilemmas discussed above are recognised by the general public [49], the in-depth exploration of physicians’ arguments with regard to these dilemmas not only fosters the debate, but also contributes to further guidance for all physicians in how to carefully handle euthanasia requests from incompetent patients with dementia. This article, in combination with our reflection on Supreme Court’s ruling, reveals several topics on which physicians may benefit from further guidance. For instance, moral dilemmas around patient autonomy emerging in cases of decision-making disabilities in advanced dementia and the (in)acceptability of the use of sedatives. Hereby this sub-study is a stepping stone to the aim of our larger research project (the DALT-project: Dementia, Advance directives and Life Termination) to provide practical guidance for physicians on this topic [50].

Conclusion

Although one of the main reasons for signing the petition was the sentiment of the petition (the opposition to ‘sneaky euthanasia’), our results show a broader scope of reasons presented by our participants related to the developments in Dutch euthanasia practice. This includes their experience of growing pressure to comply with AEDs, forcing them to cross personal boundaries within their view of euthanasia being a ‘last resort’ rather than a preferred option. The underlying motives to sign the petition are related to the moral dilemmas around patient autonomy emerging in cases of decision-making disabilities in advanced dementia. To avoid uncertainty regarding patients’ wishes in such cases, physicians express their need for reciprocal communication, or next best, a consensual approach building on a rich medical file. In addition to the (un)acceptability of the use of sedatives, physicians would benefit from more guidance on these topics. With regard to society physicians might be helped by more general education of the public about end-of-life care in dementia, including euthanasia in the advanced stages of the disease and its emotional impact on physicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jaap Schuurmans and Rob Vunderink for their help in recruiting physicians willing to participate in our research. We extend gratitude to all participating physicians for their time and for sharing their experiences. In addition, our sincere appreciation goes to Jorna van Eijk (JvE) and Melissa van Essen (both research assistants) for their help with transcribing and double coding of the interviews. Lastly, we would like to thank our other project-group-members, not listed as authors of this article, for their input during different stages of this study: Agnes van der Heide, Martin Buijsen, Brenda Frederiks and Nettie Blankenstein.

Contributor Information

Djura O Coers, Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department Medicine for Older People, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Aging & Later Life, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Marike E de Boer, Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department Medicine for Older People, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Aging & Later Life, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Eefje M Sizoo, Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department Medicine for Older People, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Aging & Later Life, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Martin Smalbrugge, Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department Medicine for Older People, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Aging & Later Life, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Carlo J W Leget, University of Humanistic Studies, Care Ethics, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Cees M P M Hertogh, Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department Medicine for Older People, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Aging & Later Life, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This research was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project no. 839120012).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any further details about the data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Rijksoverheid; Beatrix K. A.H., Borst-Eilers, E.. Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding 's-Gravenhage: Staatsblad; 2001. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012410/2021-10-01. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beatrix KAH, Borst-Eilers E. Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. 2001 edition. ‘s-Gravenhage, 2001; 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Legemaate J, Heide Aet al. In: Haag D, ed. Derde evaluatie Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. ZonMw, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartogh GA. Euthanasie op grond van een schriftelijke wilsverklaring. NJB 2017; 1702: 2226–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Jong A, Van Dijk G. Euthanasia in the Netherlands: balancing autonomy and compassion. World Med J 2017; 63: 10–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA 2016; 316: 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. RTE Jaarverslag 2020 . Regional Review Committee. Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, 2020; 17 March 2021.

- 8. Hartogh GA. De wil van de wilsonbekwame patiënt. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidsrecht 2018; 42: 431–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koninklijke Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot bevordering der Geneeskunst. Levensbeeindigend handelen bij wilsonbekwame patienten. Utrecht: Koninklijke Nederlandsche Maatschappij ter bevordering der Geneeskunst, 1993, p.80. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koopmans RTCM, Pellegrom M, Geer ER. The Dutch move beyond the concept of nursing home physician specialists. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017; 18: 746–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verenso . Elderly Care Physicians in the Netherlands, Professional Profile and Competencies. vol. 2015. Zwolle: Verenso, the Dutch Association of Elderly Care Physicians and Social Geriatricians, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vordering tot Cassatie in het Belang der Wet: Hearing before the Parket bij de Hoge Raad, Strafrecht, 2019.

- 13. RTE Oordeel 2016-85: Hearing before the Regionale Toetsingscommissie Euthanasie voor de Regio (RTE), 2016.

- 14. Miller DG, Dresser R, Kim SYH. Advance euthanasia directives: a controversial case and its ethical implications. J Med Ethics 2019; 45: 84–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asscher ECA, Vathorst S. First prosecution of a Dutch doctor since the euthanasia act of 2002: what does the verdict mean? J Med Ethics 2020; 46: 71–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schuurmans J, Chabot B, Leeuwen P. Niet stiekem bij dementie. Volkskrant 2017. www.nietstiekembijdementie.nl. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schreuder A. Artsen: te lage drempel euthanasie bij dementerenden. NRC 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pijnakker P, Engberts D, Slaets J. Omstreden euthanasie verdient breder perspectief. Medisch Contact 2019; 07: 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kallio H, Pietila AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72: 2954–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jansen-van der Weide MC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Wal G. Implementation of the project 'Support and Consultation on Euthanasia in The Netherlands' (SCEN). Health Policy 2004; 69: 365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soratto J, Pires DEP, Friese S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: potentialities for researchs in health. Rev Bras Enferm 2020; 73: e20190250. 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJet al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 821–832.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finset A. When patients have more than one concern. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 671. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wittink MN, Walsh P, Yilmaz Set al. Patient priorities and the doorknob phenomenon in primary care: can technology improve disclosure of patient stressors? Patient Educ Couns 2018; 101: 214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boer ME, Droes RM, Jonker C, Eefsting JA, Hertogh CM. Advance directives for euthanasia in dementia: do law-based opportunities lead to more euthanasia? Health Policy 2010; 98: 256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CMet al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Low LF, McGrath M, Swaffer K, Brodaty H. Communicating a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic mixed studies review of attitudes and practices of health practitioners. Dementia (London) 2019; 18: 2856–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prins A, Hemke F, Pols J, Moll van Charante EP. Diagnosing dementia in Dutch general practice: a qualitative study of GPs' practices and views. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: e416–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schuurmans J, Vos S, Vissers P, Tilburgs B, Engels Y. Supporting GPs around euthanasia requests from people with dementia: a qualitative analysis of Dutch nominal group meetings. Br J Gen Pract 2020; 70: e833–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schuurmans J, Crol C, Olde Rikkert M, Engels Y. Dutch GPs' experience of burden by euthanasia requests from people with dementia: a quantitative survey. BJGP Open 2021; 5: 9. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zuidema SU, Jonghe JF, Verhey FR, Koopmans RT. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: factor structure invariance of the Dutch nursing home version of the neuropsychiatric inventory in different stages of dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007; 24: 169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pieper M, Achterberg WP, Francke AL, Van der Steen JT, Scherder EJA, Kovach C. The implementation of the serial trial intervention for pain and challenging behaviour in advanced dementia patients (STA OP!): a clustered randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2011; 11: 1–11. 10.1186/1471-2318-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oczkowski SJW, Crawshaw D, Austin Pet al. How we can improve the quality of care for patients requesting medical assistance in dying: a qualitative study of health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021; 61: 513–521.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peisah C, Sorinmade OA, Mitchell L, Hertogh CM. Decisional capacity: toward an inclusionary approach. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25: 1571–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schuurmans J, Crol C, Chabot B, Olde Rikkert M, Engels Y. Euthanasia in advanced dementia; the view of the general practitioners in the Netherlands on a vignette case along the juridical and ethical dispute. BMC Fam Pract 2021; 22: 232. 10.1186/s12875-021-01580-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Vissers KC, Weel C. 'Unbearable suffering': a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics 2011; 37: 727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rozemond K. Mensen hebben het recht om euthanasie te weigeren. Nederlands Juristenblad 2020; Afl. 5: 331–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boer ME, Depla M, Breejen M, Slottje P, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Hertogh C. Pressure in dealing with requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide. Experiences of general practitioners. J Med Ethics 2019; 45: 425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schuurmans J, Bouwmeester R, Crombach Let al. Euthanasia requests in dementia cases; what are experiences and needs of Dutch physicians? A qualitative interview study. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20: 66. 10.1186/s12910-019-0401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haverkate I, Van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Maas PJ, Wal G. The emotional impact on physicians of hastening the death of a patient. Med J Aust 2001; 175: 519–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Snijdewind MC, Tol DG, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Willems DL. Developments in the practice of physician-assisted dying: perceptions of physicians who had experience with complex cases. J Med Ethics 2018; 44: 292–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Buijsen M. Mutatis mutandis…on euthanasia and advanced dementia in the Netherlands. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2022; 31: 40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. European Convention on Human Rights. SAGE Publications, Inc., 1970.

- 47. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol (UNCRPD). United Nations, 2006.

- 48. Mills A, Durepos G, Wiebe E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research, 2010.

- 49. Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, Delden JJet al. Opinions of health care professionals and the public after eight years of euthanasia legislation in the Netherlands: a mixed methods approach. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coers DO, Boer ME, Buijsen MAJM, Leget CJW, Hertogh CMPM. Euthanasie bij gevorderde dementie: het DALT-project. De ontwikkeling van een praktische handreiking over euthanasie bij dementie op basis van een schriftelijke wilsverklaring. Tijdschrift voor Ouderengeneeskunde 2019; 2: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any further details about the data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.