Abstract

Background:

HIV incidence amongst adolescents in Southern Africa remains unacceptably high. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective HIV prevention intervention but there are few data on its implementation among adolescents. We aimed to investigate the safety, feasibility and acceptability of oral PrEP (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/Emtricitabine) as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package in an adolescent population in South Africa

Methods:

Pluspills was conducted in Cape Town and Johannesburg. HIV negative participants between 15–19 years old participated in an open-label oral PrEP study over 52 weeks. Participants took daily PrEP for the first 12 weeks and were then given the choice to opt-in or opt out of PrEP use at three monthly intervals. The primary outcomes were acceptability, use and safety of PrEP. Acceptability was measured by the proportion of participants who reported willingness to take up PrEP and remain on PrEP at each 3 month study time point. Use was defined as the number of participants who continued to use PrEP after the initial 12 week period until the end of the study (week 48). Safety was measured by grade two, three and four laboratory and clinical adverse events.

Findings:

Overall 148 participants were enrolled (median age 18 years; 67% female) and initiated PrEP. STI prevalence at baseline was high 41% (60/148) and remained so throughout the study. PrEP was stopped by 26 (18%) participants at 12 weeks. Cumulative PrEP opt-out at weeks 24 and 36 comprised 41% (60/148) and 43% (63/148) of the total cohort respectively. PrEP was well tolerated with only minor adverse effects including headache, dizziness and nausea.. Tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) concentrations as measured in dried blood spot samples were detectable (>16fmol/punch) in 92% (108/118)) of participants who reported PrEP use at week 12, 74% at week 24 (74/100) and 58% (22/37) by study end.

Interpretation:

In this cohort of self-selected South African adolescents at risk of HIV acquisition, PrEP appears safe and tolerable in those who continued use. PrEP use decreased throughout the course of the study as visit frequency declined. STI incidence remained high, despite low HIV incidence. This population in Southern Africa need access to PrEP with tailored adherence support and possibly the option for more frequent and flexible visit schedules.

Funding:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Keywords: PrEP, HIV Prevention, Adolescents, South Africa

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa carries the largest burden of HIV globally, with an estimated 1·1 million new infections annually1,2.HIV incidence amongst young people in the region remains disproportionately high, with girls accounting for three out of four new infections amongst 15–19 year olds.3,4 The importance of adolescent HIV prevention strategies in tackling the epidemic worldwide is increasingly recognised with a global target from UNICEF to reduce new adolescent HIV infections by 75% by 20203–6.

Adolescent vulnerability to HIV infection is due to a complex interplay between structural, economic, socio-cultural and biological factors during a developmental phase when behaviours associated with HIV acquisition and sexual and reproductive health seeking are initiated4, 7. The multidimensional vulnerability of adolescents and youth to HIV is particularly manifested in South Africa, where young women aged 15–24 accounted for almost 40% of new HIV infections in 20178–10. Despite the importance of HIV prevention efforts to support access to testing and treatment for young people, there are few interventions that have demonstrated HIV infection risk reduction among this group in South Africa and other resource-limited settings11–14. The CHAMPS (Choices for HIV Adolescent Methods of Prevention in South Africa) was a program made up of three different independent protocols designed to explore different HIV prevention options in adolescents in South Africa. Besides medical male circumcision, and a protocol exploring different modes of PrEP delivery, Pluspills was the protocol designed to explore feasibility, safety and uptake of oral PrEP.

PrEP has been proven to be efficacious in a variety of contexts and populations15–17. PrEP studies have largely focused on adults with subsequent inadequate youth representation and minimal data specifically applicable to adolescents and young people in Southern Africa18. While data is emerging on the use of PrEP in at risk youth in the USA19, this may not be broadly applicable to a younger African heterosexual population. The challenge of daily PrEP adherence in younger people in all settings is recognised, with a strong correlation between inadequate adherence to PrEP and reduced efficacy20– 22. Given the HIV incidence rates amongst adolescents in Southern Africa, oral PrEP for this group is likely to have an impact on population-level HIV incidence14, 15, 23. To help inform PrEP implementation strategies, we designed an open-label demonstration study known as Pluspills for adolescents aged 15–19 years in South Africa to examine the safety, use, feasibility and acceptability of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package.

Methods

Study Design

The PlusPills study was an open-label phase 2 clinical trial designed to assess the acceptability, use, adherence to, and safety of daily oral PrEP (TDF/FTC) for HIV prevention among 150 male and female participants between 15–19 years old in Cape Town and Johannesburg. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating study sites, the South African Medicine Control Council and the Division of AIDS (DAIDS) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The trial was conducted in compliance with the ICH-GCP and SA-GCP guidelines and was registered in the public registry database of ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02213328) prior to participant recruitment. The role of Gilead Sciences in the development of the protocol was limited to sections regarding handling of study drugs.

Setting

The two study sites in Cape Town and Johannesburg serve peri-urban low-income communities with a substantial burden of HIV. Both sites have long established relationships with community stakeholders, experienced study staff, adolescent responsive activities as well as sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, and an active adolescent Community Advisory Board (CAB). Multiple recruitment methods were used to recruit participants including community outreach at schools, youth groups, sports clubs, local clinics transport hubs and recruitment drives in the community. Participants were given recruitment materials (pamphlets, brochures and flyers) and those expressing an interest in participating were invited to attend pre- screening information sessions at the research site.

Study Participants

Inclusion criteria required the following: for participants to be sexually active; have a parental or guardian proxy give informed consent for participants <18years and assent in minors; individual consent for those >18yrs and willing to participate in study-required procedures, including taking TDF/FTC as PrEP for the first 12 weeks of the study. Potential participants were deemed ineligible if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, HIV positive or had any significant co-morbidities: >Grade 2 hypophosphatemia; acute or chronic hepatitis B infection; renal dysfunction with creatinine clearance <75 ml/min or a history of unexplained bone fractures. Female participants agreed to use contraceptive methods during the study with implantable, injectable and oral hormonal contraception being provided by the study sites. All participants were evaluated for symptoms of acute HIV infection prior to enrollment.

Study Procedures:

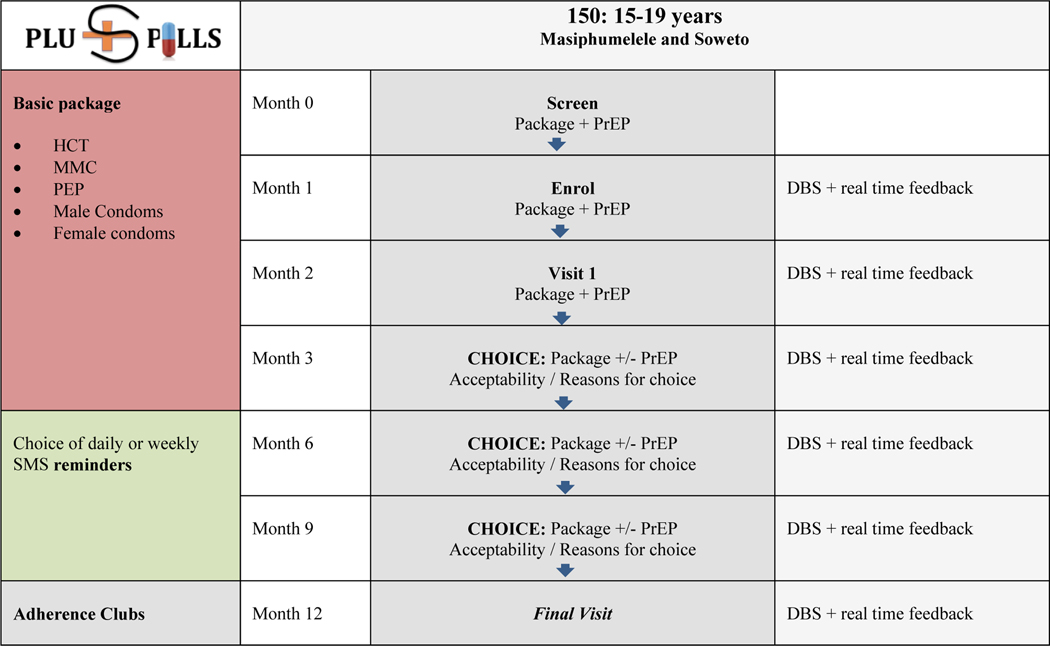

Participants were invited to screen for this study following an HIV prevention education session. Those determined to be eligible were requested to return for an enrollment visit at which they were asked to take PrEP as part of a comprehensive prevention package for at least 12 weeks. During this time, participants made monthly visits for adherence counselling and HIV testing. Results of drug concentration sampling were used as an adherence-enhancing strategy for those participants who elected to receive this information during follow up visits. Those who chose not to receive these results received standard motivational adherence counselling during study visits. Participants were given the option to opt out of PrEP but to remain in the study at the 12 week visit, and then every three months thereafter until follow up ended at week 52 (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Study Design for CHAMPS: Pilot study B: “PlusPills

Outcomes

The primary outcomes included acceptability, use and safety of PrEP. Acceptability was measured by the proportion of participants who reported willingness to use the study regimen, take up PrEP and remain on PrEP at each 3 month study time point. Use was defined as the number of participants who continued to use PrEP after the initial 12 week period until the end of the study (week 48). PrEP discontinuation was defined as participants who attended a visit and refused PrEP. Safety was measured by grade two, three and four laboratory and clinical adverse events using the DAIDS table for grading the severity of adult and paediatric adverse events, version 1.0 December 2004 (clarification August 2009).

The secondary outcomes related to adherence to PrEP, sexual risk behaviours and HIV and STI infections. Adherence was measured by the proportion of participants on PrEP with detectable plasma drug levels and tenofovir diphosphate concentrations. Sexual activity was defined as a minimum of one act of self-reported vaginal sex in the last 12 months. Sexual risk behaviours included the number of regular and casual sex partners and condom use, captured by participant responses to interviewer-administered questionnaires. HIV and Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) incidence was measured as the number of infections per person time at risk. STI prevalence was measured as the proportion of participants with STI’s at the 12 and 48 week visits.

Drug concentrations: Intracellular tenofovir- diphosphate (TFV-DP) DBS and plasma samples for tenofovir (TFV) were collected at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48. TFV-DP concentrations were measured in dried blood spots at the University of Cape Town using a validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) assay, originally developed and validated at the University of Colorado 24. Plasma tenofovir was measured with a validated LC/MS/MS assay at the University of Cape Town. Intracellular TFV-DP in DBS was used as an objective measure of product adherence with a detectable level of >16 fmol/punch and a threshold level for high adherence of 500 fmol/punch at four weeks and 700 fmol/punch thereafter, based on time for intracellular TFV-DP levels to reach steady state 25, 26, 27. Plasma tenofovir drug concentrations were an alternative measure of product adherence with a cut off of 10 ng/ml to indicate any use (a detectable level) and 40 ng/ml as adherent use28.

Laboratory Testing: Pregnancy testing, HIV and Hepatitis B testing and safety bloods (full blood count, creatinine, phosphate, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, urine dipstick) were performed at screening. HIV and pregnancy tests were taken at enrolment and weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48. HIV rapid testing was done in parallel using Determine™ HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo and Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® HIV-1/2. If the rapid HIV test was reactive, an HIV-1 RNA qualitative assay (Abbot) was performed. A positive test was confirmed with a second blood sample collected a week later. Self-collected vaginal swabs (females) and urine (males) was collected and tested for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhea (NG) using GeneXpert® (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) and HSV-2 testing (KALON) was conducted at screening, and at weeks 12 and 48 with appropriate treatment provided.

Safety and tolerability were assessed during the study. Proteinuria, creatinine clearance, glycosuria and liver enzymes were monitored regularly, and all adverse events were graded, recorded and assessed. Neurological side effects such as headaches and dizziness, gastrointestinal side effects and social harms were recorded. Those who tested positive for HIV at screening or throughout the study were referred for ongoing HIV care and management. Expedited Adverse Event (EAE) reporting followed standard reporting requirements as defined in the DAIDS Manual for Expedited Reporting of Adverse Events version 2·0, March 2011 and adverse events were discussed and were discussed contemporaneously with the Protocol Safety Team. An external Data and Safety Monitoring Board reviewed study safety data on three occasions at six-month intervals during trial implementation and recommended that the study continue to completion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of the baseline data were performed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp). College Station, TX) Demographic and other baseline characteristics were summarized using appropriate descriptive statistics for continuous variables, descriptive statistics include medians and interquartile ranges. Factors affecting adherence were compared between youth who were adherent to PrEP (TFV-DP ≥ 700 fmol/punch) and youth who were non adherent to PrEP using a logistic regression with mixed effects modelling.

Role of the Funding source:

The work reported herein was also made possible through funding by the South African Medical Research Council through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the SAMRC Postdoctoral Program from funding received from the South African National Treasury. The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or the funders.

The University of Cape Town Clinical PK Laboratory is supported in part via the Adult Clinical Trial Group (ACTG), by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, and UM1 AI106701; as well as the Infant Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT), funding provided by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01 AI068632), The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Institute of Mental Health grant AI068632.

The tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine co-formulated study medication was donated and the funding for the and the funding for the Tenofovir drug level measurements in dried blood spots was received as a grant for this study from Gilead Sciences.

The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

Participants and baseline characteristics

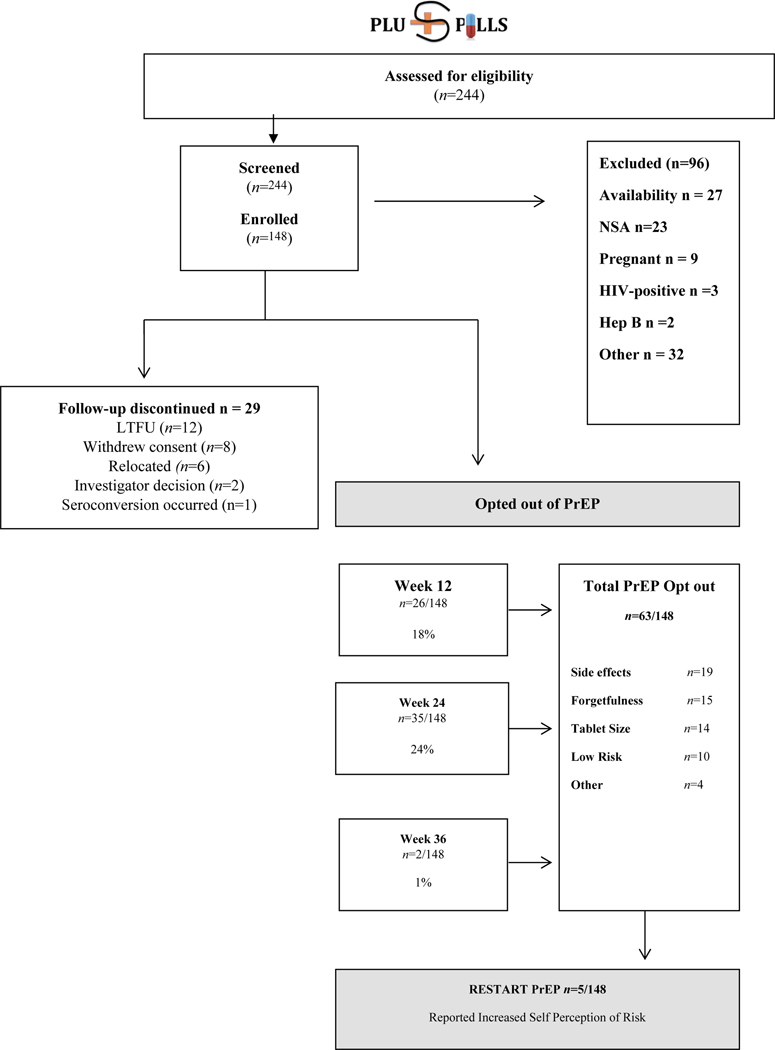

Between April 2015 and February 2016, 244 participants were screened and 148 participants enrolled across both sites (Fig 2). The most common reason for ineligibility was being unavailable for all trial visits and procedures (n=27), followed by not being sexually active (n=23), pregnancy (n=9), HIV seropositivity (n=3) and hepatitis B surface antigen positivity (n=2). Table 1 shows cohort characteristics at enrolment. The median age of participants was 18 (IQR17–19). 99 were female (67%) and 49 were male (33%) with older female participants aged 18 and 19 comprising 42% of the cohort. Participants less than 18 years made up 33% (48/148) of the cohort. Three quarters of participants attended high school (n=111) and 10% (n=15) were in tertiary education. 80% (n=119) of participants lived with at least one or both parents, the remainder lived with another family member or caregiver. 28 participants were prematurely discontinued from the study with reasons for non-completion shown in figure 2. Overall study retention was 81%.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram for CHAMPS: Pilot study B: “PlusPills”

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data

| Characteristic | Female (n=99) | Male (n=49) | All (n=148) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 18 (16–19) | 18 ( 17–18) | 18 ( 17–18.5) |

| Ethnicity – Black African | 99 (100%) | 49 (100%) | 148 (100%) |

|

Location

Cape Town Soweto |

52 (53 %) 47 (47 %) |

23 (47 %) 26 (53 %) |

75 (51%) 73 (49%) |

| School attendance | 72 (73%) | 39 (80%) | 111 (75%) |

| Highest completed grade (median, IQR) | 10 (10–12) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–12) |

| Attending tertiary education | 9 (9 %) | 6 (12 %) | 15 (10%) |

|

Household

Living with mother and/or father |

82 (83%) |

37 (76%) |

119 (80%) |

| Consistent condom use in the last year | 70 (71%) | 30 (61%) | 100 (67%) |

| Condom use (last sexual act) | 70 (71%) | 38 (76%) | 108 (74%) |

| Any positive STI test | 50 (51%) | 10 (20%) | 60 (41%) |

| Multiple partners in last year | 22 (22%) | 27 (55%) | 49 (33%) |

| Had a partner > 5 years older in last year | 24 (24%) | 6 (12%) | 30 (20%) |

| Transactional sex in last year | 4 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (3%) |

Safety and tolerability

In total, 11% (16/148) of the participants experienced either a grade 2 or 3 transient adverse health events. The most common grade 2 events were headaches and dizziness, (n=4) and nausea and vomiting (n=4). Participants also reported abdominal pain (n=2) diarrhoea (n=2) and skin rash (n= 2). Two participants experienced grade 3 weight loss, which was deemed related to the study drug and resolved fully when PrEP was discontinued. There were no bone fractures and no PrEP interruptions occurred due to renal impairment. Four participants experienced a grade 3 or 4 serious adverse event that was deemed unrelated to study drug. Adverse events are reported in Table 4 (web appendix). One participant overdosed on study medication in a para-suicide attempt unrelated to study participation following an argument with her mother. She received support from the site, was referred for psychological support and made a full recovery. Side effects were cited as a reason for stopping PrEP in 13% of the cohort (n=19/148). One incident of social harm was attributed to study participation, where a participant was assaulted by her partner after he found the tablets and assumed she had been concealing her HIV status. The participant was assisted to report the incident to the police, was referred for counselling and withdrew from the study. One 14 year old participant was inadvertently enrolled and exited from the study following a discussion with the safety team and Ethics Committee.

Sexual Risk Behaviour

Median age at sexual debut was 15 (IQR 14–16). A third of the participants (n=49/148) reported multiple partners in the last year and 20% (n=30/148) reported age- disparate relationships (sexual partners aged ≥5 years than participant) (Table 1). A third of participants=48/148 gave a history of inconsistent condom use at baseline with no significant differences between the sexes (p=0.5). Less than 10% of participants reported previous anal intercourse (n=10 ). More than half of the participants (n=83/148) reported alcohol use in the preceding 12 months. A quarter (n=25/148) had used recreational drugs in the previous 12 months, with marijuana as the most commonly reported drug used. (n=23/148; 15.5%).

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Table 2 shows STI prevalence during the study stratified by sex. The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections was high at baseline with 60 participants (41%) testing positive for at least one STI. Half of the females (50/99) had at least one STI at baseline versus 20% (10/49) of male participants (p= 0.001). STI prevalence remained high throughout the study despite treatment, counselling and partner treatment. Chlamydia trachomatis was the most frequently occurring infection with a prevalence of 30% (45/148) at baseline, 17% (21/124) at week 12 and 26% (24/91) at study end. HSV-2 was the second most common infection with 16% (n=24/148) seropositive at baseline and overall incidence of HSV-2 was 8·3 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 4·31 – 16). There were no incident pregnancies reported during study follow up. There was one reported HIV seroconversion in a 19-year-old female participant who had stopped PrEP 24 weeks prior to diagnosis. The overall HIV incidence was 0·76 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 0·1– 4·3) and 1·16 per 100 girl-years (95% CI: 0·2– 6·29).

Table 2.

STI prevalence by sex

| Female | Male | All | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Baseline (n=99) | W-12 (n=82) | W-48 (n=58) | Baseline (n=49) | W-12 ( n=42) | W-48 (n=33) | Baseline (n=148) | W-12 (n=124) | W-48 (n=91) |

| Chlamydia | 38 (38%) | 18 (22%) | 23 (40%) | 7 (14%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 45 (30%) | 21 (17%) | 24 (26%) |

| Gonorrhoea | 6 (6%) | 8 (10%) | 6 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 8 (5%) | 8 (6%) | 6 (7%) |

| Herpes | 20 (20%) | 20 (24 %) | 18 (31%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (12%) | 6 (18%) | 24 (16%) | 25 (20%) | 23 (25%) |

| Any | 50 (51%) | 29 (35%) | 29 (50%) | 10 (20%) | 6 (14%) | 6 (18%) | 60 (41%) | 35 (28%) | 37 (41%) |

Acceptability

PrEP acceptability was recorded at every follow-up visit. The acceptability instrument (a twelve-item graded Likert scale) assessed the usability of PrEP and the motivation for continued PrEP use. At week 12, 83% (104/126) of participants indicated that they “liked” or would “like to continue” taking PrEP and 79% (100/126) of participants collected their PrEP prescription at the study site. At 12 weeks 98% (123/126) of participants taking PrEP indicated that they “liked” PrEP as they felt protected from HIV. This preference remained constant throughout the study.

Medication adherence and study opt-out

DBS tenofovir levels indicated that 95% (141/148) of participants had a detectable drug level during the study with 5% (7/148) not having used PrEP at all. Plasma tenofovir levels similarly showed that 82% (121/148) of participants had a detectable drug level at any time during the study. In total 43% (63/148) of the cohort chose to stop taking PrEP at any point during the study. Side effects were the most commonly cited reason for choosing to stop (19/63, 30%). Other reasons included forgetting (15/63, 24%), tablet size (14/63, 22%) and decreased perception of risk (10/63, 16%). 8% (5/63) chose to start taking PrEP again after stopping citing increased risk as the reason.

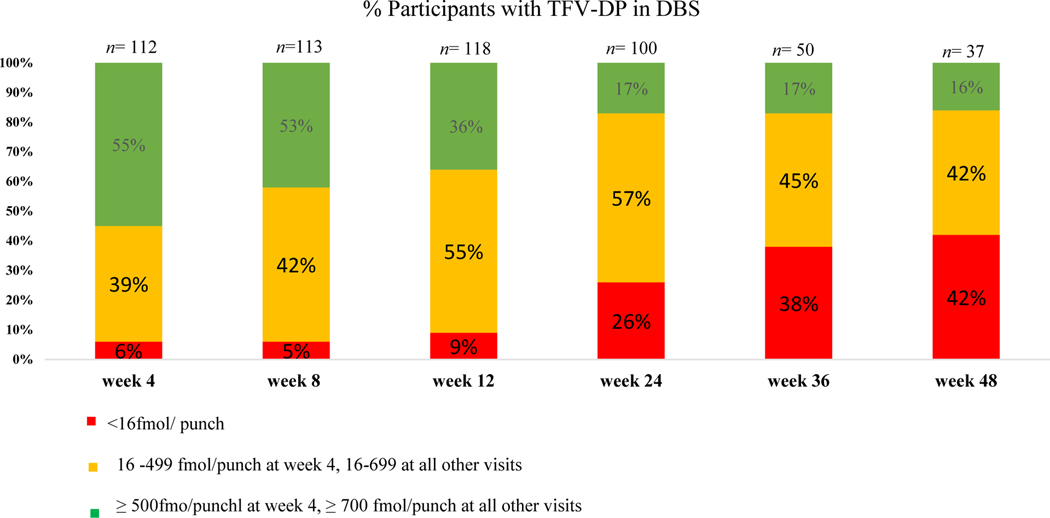

First 12 weeks: Drug levels were relatively constant in the first three-month phase with 94% (105/112) of participants having detectable TFV-DP levels at week 4, 94% (107/113) at week 8 and 92% (108/118) at week 12. In contrast, 71% (79/112) of participants had detectable plasma tenofovir levels at week 4, 67% (76/113) at week 8 and 54% (64/118) at week 12. Thereafter, 26 participants (18%) chose to stop taking PrEP at the 12-week visit (figure 2).

Weeks 24–48: Twenty four percent of the cohort (35/148) chose to opt-out of PrEP at the 24 weeks visit with a further 1% (2/148) opting-out of PrEP at the week 36 visit. There was also a decline in TFV-DP levels from the week 24 visit, with detectable levels seen in 74% (74/100) of participants who chose to continue PrEP. Plasma tenofovir levels declined to detectable plasma levels seen in 41% (41/100) of participants who chose to continue PrEP. This remained constant over the following 24 weeks with 58% (22/37) and 46% (17/37) of participants on PrEP having a detectable level according to DBS and plasma samples at the week 48 visit. Table 3 shows a mixed effects logistic regression model for factors predicting adherence. Time (adjOR 0.89; 95% CI 0.86, 0.92) and age (adjOR 0.57; CI 0.40, 0.82) were the only statistically significant predictors of adherence (p <0.001 and p <0.003 respectively). The most common reasons given for poor adherence were that participants forgot, lost or ran out of tablets (41%). Other reasons given included being worried about potential side effects (6%), being too busy (5%) or being away from home (5%). Figure 3 demonstrates TFV- DP DBS levels by week.

Table 3.

Univariate factor model and Multivariable mixed effects logistic regression model for high adherence (TFV- DP levels ≥ 700 fmol/punch)

| Univariate model | Multivariate Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | OR | Confidence interval | P value | Adjusted OR | Confidence interval | P value |

| Consistent condom use | 1.32 | 0.66 – 2.67 | 0.42 | |||

| Transactional sex | 1.34 | 0.5–3.59 | 0.56 | |||

| Anal Sex | 0.32 | 0.074–1.4 | 0.13 | |||

| STI at baseline | 0.64 | 0.33–1.27 | 0.2 | |||

| Sexual debut in years | 0.99 | 0.92 – 1.06 | 0.8 | |||

| >1 sex partner | 1.3 | 0.76– 1.5 | 0.21 | |||

| Time in weeks | 0.89 | 0.86 – 0.92 | 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.86 – 0.92 | 0.001 |

| Age in years | 0.65 | 0.5–0.85 | 0.002 | 0.57 | 0.40 – 0.82 | 0.003 |

| Gender (male) | 0.73 | 0.36– 1.51 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.20 – 1.47 | 0.3 |

| Site (Soweto) | 1.36 | 0.69– 2.68 | 0.38 | 1.5 | 0.62 – 3.91 | 0.34 |

Figure 3.

TFV-DP levels by week for CHAMPS: Pilot study B: “PlusPills”

Plasma TFV vs TFV-DP

Plasma TFV and TFV- DP drug level results were correlated and reached agreement in 77% (425/552) of samples. 13% of the samples (73/552) had high plasma TFV with low TFV- DP suggesting possible white coat dosing with a dose taken prior to the study visit but otherwise poor adherence in the preceding month. 10% of the samples (54/552) had low plasma TFV with high TFV-DP suggesting good adherence in the preceding month but no dosing prior to the study visit.

Discussion

PlusPills is the first oral PrEP study in a heterosexual adolescent population in Africa and provides important safety and adherence data for young people in South Africa and in the region. Oral PrEP was safe and relatively well tolerated by participants, with reported side effects temporary and similar to those described in adult PrEP studies. Acceptability of PrEP and study participation remained high throughout.

This study demonstrated the feasibility of enrolment and retention of young men and women who appear to be at substantial risk of HIV acquisition. The significant levels of STI’s both at baseline and during the study, together with self-reported sexual risk behaviour, suggest a population suitable for PrEP use, obviating the need for complex risk assessment tools for selection.

HIV incidence was low in this open label single arm study, with a single HIV seroconversion occurring in one participant who had opted out of PrEP earlier in the study. The incidence rate of 0.76 per 100 person years is 73% lower than the HIV incidence rate that is estimated nationally for sexually active adolescents aged 15–19 (2.81 per hundred person years if assuming one third male and two thirds female, as in our study population21.) While this study was not powered to measure HIV incidence or designed as an efficacy study, the low incidence rate, relative to the national average, suggests a possible benefit from PrEP. The STI prevalence and incidence throughout the study indicates that young people in this setting remain engaged in sexual risk behaviour even within a context of supportive and adolescent-responsive health services. Incorporating PrEP as an added measure into adolescent sexual and reproductive services is critical to allow holistic and targeted care for young people during this vulnerable period.

The rationale for offering PrEP opt-in and opt-out at intervals during the PlusPills study was to replicate real-world PrEP use according to “seasons” of HIV risk 29– 32. A possible explanation for the low HIV incidence in this study despite high levels of STIs suggesting condomless sex, is that participants identified their own seasons of risk and successfully used event or season-based PrEP. This possibility warrants further study. Implementation programmes should aim to support and empower the adolescent to use PrEP for specified periods of anticipated HIV exposure instead of relying on traditional adherence messaging and measures such as pill-counts still in use in some ARV clinics in resource-limited settings. Using PrEP according to a specified season of risk should be recognised as different to event-based PrEP. The ADAPT (HPTN 067) study33, also conducted in Cape Town albeit in a slightly older group of women, found that daily oral PrEP was more successful than intermittent use in terms of number of sex acts that were “covered” by drug exposure. More research into dosing and dosing schedules is urgently required among young heterosexual people. It is likely that an individualised and non-judgmental approach to PrEP is likely to improve uptake and adherence. Another consideration is that pluspills required parental proxy consent for participation of adolescents younger than 18 years. This likely led to the lower numbers of younger people in the cohort and may also have contributed to recruitment of individuals with lower HIV incidence.

Daily PrEP adherence is a considerable challenge for younger populations, including in this study and has been reported in North American adolescent and young adult PrEP studies. In particular in ATN 110 15, 34 and ATN 113 15, 35 TFV-DP concentrations in blood samples declined as the frequency of study visits were reduced per protocol. Adherence also decreased with increasing age and this may reflect increased familial support in the younger participants who needed parental consent to participate. In pluspills one third of the population was younger than 18 years. Fewer than 60% of participants had detectable TFV-DP levels by week 48, and 40% of the study population had chosen to discontinue PrEP by week 36, although participants were retained in the study and continued to receive the range of adolescent-friendly SRH services offered. This further underlines the importance of integrating PrEP into SRH services so that PrEP can be offered regularly to young people attending health services. Young people on PrEP may benefit from more frequent PrEP visits to augment and support adherence as appropriate. Work is needed to identify successful adolescent-specific strategies to address adherence including mobile technology to enhance clinic contact frequency, adherence support groups, peer mentors and cash incentives.

Drug levels measured in plasma and dried blood spots correlated reasonably well indicating that in this population either could be used to provide objective measures of PrEP use. In Pluspills, the recommendation to participants was that they take the oral PrEP daily and these measures provide some additional information in understanding patterns of PrEP use. In those individuals who choose to use PrEP intermittently according to sexual exposure risk, the interpretation of these measures of adherence will remain challenging.

This study supports the hypothesis that oral PrEP is safe and acceptable for young people while also reinforcing the view that adherence is challenging for young people. PrEP roll out in South Africa is being prioritized to groups most at risk, including sex workers, men who have sex with men and most recently, adolescent girls. Prioritizing PrEP for at risk young women can be cost effective considering that there may be costly obstacles to initiating treatment for HIV positive youth using the same drug.36– 39. Oral PrEP in combination with other proven HIV prevention interventions should be offered to South African adolescents and young people in a tailored fashion including developmentally appropriate support for effective PrEP use.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study:

We searched electronic databases Medline, Embase, Pubmed, African Index Medicus and the Cochrane database of systematic reviews to identify studies of PrEP in adolescents in which the primary outcomes were safety and acceptability. We included studies published up to September 2019, in any language. Our search included keywords “PrEP” OR “Pre-exposure prophylaxis OR “tenofovir/emtricitabine” AND “safety” OR “acceptability” AND “adolescent” OR “young” AND “Africa”. We screened abstracts to retrieve full text articles for assessment of eligibility and checked reference lists of relevant studies and reviews for additional references.

While there was plenty of evidence for the safety and acceptability of PrEP in adult populations and a limited number of studies in adolescent MSM in North America we were unable to find any studies meeting our search terms in an African adolescent context.

The Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) 113 and ATN 110 studies have been reported; These tested the acceptability, safety and adherence to PrEP among 78 MSM ages 15–17 years and 200 MSM 18–24 years respectively. The ATN studies showed that although acceptability to oral PrEP use was high, there was lower adherence among these youth compared with adults. The studies also show that over time, adherence to oral PrEP waned. The use of oral PrEP to prevent HIV in youth may be viewed as a time-limited strategy that could bridge the developmental period between sexual debut and adulthood. While the potential relevance and plausibility of an oral PrEP strategy as a safe, powerful and time-limited tool for HIV prevention among high risk people is widely acknowledged, a number of questions regarding the use of PrEP in young people still need to be addressed. These issues include, but are not limited to, the identification of the best drug(s) and optimal dosing regimens in terms of efficacy, safety, adherence and cost-efficiency, designing an effective message that does not reduce the salience of reducing sexual risk behaviours, and the acceptability of a PrEP prevention strategy within different populations. Thus, the feasibility of recruiting and retaining young participants in a PrEP study, the evaluation of the acceptability of such a study among adolescents, and the evaluation of adherence to the PrEP regimen were all issues that needed to be urgently addressed.

Added value of this study:

Pluspills is the first study to investigate the safety and acceptability of oral PrEP within an African adolescent population. The study provides safety, acceptability and adherence data which builds on the sparse but growing evidence from adolescent and young adult populations. The study was also designed to replicate real-world PrEP use and to understand patterns of uptake and use in a population who are especially at risk for HIV.

Implications of all the available evidence:

This study supports the hypothesis that oral PrEP is safe and acceptable for adolescents. It also underscores the view that adherence is challenging for young people. PrEP roll out in South Africa is being prioritized to groups most at risk for HIV, including sex workers, men who have sex with men and most recently, adolescent girls. An evidence base for this type of information will inform policymakers and practitioners on how to best implement and promote an oral PrEP regimen for African adolescents.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the study teams at both sites.We would also like to thank Dr Sinead Delany-Moretlwe, Dr Kathy Mngadi, Dr Shaun Barnabas and Dr Frances Cowan for providing their expertise on the data safety and monitoring calls.

Funding:

NIH Grant #: R01AI094586, NCT02213328

Abbreviations:

- PrEP

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: JFR is an employee and stockholder of Gilead Sciences. All other authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The corresponding author had full access to all data and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: JFR is an employee and stockholder of Gilead Sciences.

Data Sharing: De-identified data that underlie the results in this manuscript will be made available on request.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). [Internet]. UNAIDS; 2018. Switzerland [updated 2019 Jul 20; cited 2020 26 Feb]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kharsany A, Karim Q. HIV Infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Status, Challenges and Opportunities. The Open AIDS Journal. 2016; 10(1):34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNICEF. ALL IN to end the adolescent AIDS epidemic. Switzerland. UNICEF; [updated 2016 Dec 16; cited 2019 Apr 9]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ALLIN2016ProgressReport_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, Swartz Alison Swartz, Lurie M. Sustained High HIV Incidence in Young Women in Southern Africa: Social, Behavioral, and Structural Factors and Emerging Intervention Approaches. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. [Internet]. 2015. Dec [cited 2019 Apr 09]; 12(2):207–215. Available from: URL 10.1007/s11904-015-0261-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS by the numbers, AIDS is not over, but it can be. Switzerland. UNAIDS; 2016. [updated 2016 Nov 21; cited 2019 Apr 9]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/AIDS-by-the-numbers [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramaphosa MC Let Our Actions Count: South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. South African National AIDS Council. [Internet]. Pretoria. SANAC; 2017. [updated 2018 Mar 9; cited 2019 Apr 9] Available from: https://sanac.org.za/download-the-full-version-of-the-national-strategic-plan-for-hiv-tb-and-stis-2017-2022/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buvé A, Bishikwabo-Nsarhaza K, Mutangadura G. The spread and effect of HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. [Internet]. 2002. Jun [cited 2019 Apr 09]; 359(9322):2011–2017. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08848-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention [Internet]. Avert. 2019. [cited 31 October 2019]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis

- 9.Women and HIV. A spotlight on adolescent girls and young women [Internet].UNAIDS. 2019. [cited 31 October 2019]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019_women-and-hiv_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.ART Adherence in Adolescents [Internet]. South Africa: SA HIV Clinicians Society; 2018. [cited 31 October 2019]. Available from: https://sahivsoc.org/Files/1A_Juliet-Houghton.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemmott JB 3rd., Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, Ngwane Z, Lewis DA, Bellamy SL, et al. HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention efficacy with South African adolescents over 54 months. Health Psychol. [Internet]. 2015. Jun [cited 2019 Apr 09]; 34(6): 610–21. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fhea0000140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurth AE, Celum C, BaetenSten JM, Vermund H, Wasserheit JN Combination HIV Prevention: Significance, Challenges, and Opportunities. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. [Internet]. 2011. Mar [cited 2019 Apr 09]: 8(1): 62–72. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3036787/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang LW, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Gray RH, and Reynolds SJ Combination implementation for HIV prevention: moving from clinical trial evidence to population-level effects. Lancet Infect Dis. [Internet]. 2013. Jan [cited 2019 Apr 09]:13(1):65–76. Available from: doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70273-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AVERT. Global information and education on HIV and AIDS. [Internet]. United Kingdom. AVERT; 2017. [updated 2017 Aug 30; cited 2019 Apr 9]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/overview [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Delany-Moretlwe S. Bekker LG. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. Journal of the Int AIDS Soc. [Internet]. 2016. Oct [cited 2019 Apr 09] 19:21107. Available from: doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holly J, Lawrence C, Ramjee Gita, Carpp LN, Lombard C, Cohen MS et al. Weighing the Evidence of Efficacy of Oral PrEP for HIV Prevention in Women in Southern Africa. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. [Internet]. 2018. Aug [cited 2019 Apr 09] 34(8): 645–646. Available from: 10.1089/aid.2018.0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson KA, Baeten JM, Mugo NR, Bekker LG, Celum CL, Heffron R. Tenofovir-based oral preexposure prophylaxis prevents HIV infection among women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. [Internet]. 2016. Jan [cited 2019 Apr 09] 11(1):18–26. Available from: doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. [Internet]. Atlanta. CDC; 2019. [updated 2019 Apr 10; cited 2019 Apr 9]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. [Internet]. 2016. Jul [cited 2019 Apr 09]; 31; 30(12): 1973–83. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4949005/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machado D, de Sant’Anna Carvalho A, Riera R. Adolescent pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2017; Volume 8:137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson LF, Chiu C, Myer L, Davies MA, Dorrington RE, Bekker LG, et al. Prospects for HIV control in South Africa: a model-based analysis. Glob Health Action. [Internet]. 2016. Jun [cited 2019 Apr 09]; 9(1): Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3402/gha.v9.30314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maljaars L, Gill K, Smith P, Gray G, Dietrich J, Gomez G et al. Condom migration after introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV-uninfected adolescents in South Africa: A cohort analysis. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2017; 18(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettifor A, Stoner M, Pike C, Bekker L. Adolescent lives matter. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2018; 13(3):265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:384–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson P, Liu A, Castill-Mancilla J, et al. TFV-DP in Dried Blood Spots (DBS) Following Directly Observed Therapy: DOT-DBS Study. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). Seattle, WA USA, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:151ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips T, Sinxadi P, Abrams, et al. Comparison of Plasma Efavirenz and Tenofovir, Dried Blood Spot Tenofovir-Diphosphate, and self-reported adherence to predict virologic suppression among South African women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019. Jul 1; 81(3):311–318. Doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002032. PubMed PMID: 30893125; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6565450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanoni B, Archary M, Buchan S, Katz I, Haberer J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adolescent HIV continuum of care in South Africa: The Cresting Wave. 2020. BMJ Global Health 2016; 1:e000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bekker L, Rebe K, Venter F, Maartens G, Moorhouse M, Conradie F et al. Southern African guidelines on the safe use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in persons at risk of acquiring HIV-1 infection. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2016; 17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eakle R, Venter F, Rees H. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in an era of stalled HIV prevention: Can it change the game? Retrovirology. 2018; 15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren E, Paterson P, Schulz W, Lees S, Eakle R, Stadler J et al. Risk perception and the influence on uptake and use of biomedical prevention interventions for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review. PLOS ONE. 2018; 13(6):e0198680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bekker LG., Roux S, Sebastien E, Yola N, Amico KR, Hughes JP, et al. Daily and non-daily pre-exposure prophylaxis in African women (HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town Trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. [Internet]. 2017. Oct [cited 2019 Apr 16]; 5(2): Available from: DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30156-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosek S, Rudy B, Landovitz R, Kapogiannis B, Siberry G, Rutledge B et al. An HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project and Safety Study for Young MSM. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2017; 74(1):21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machado D, de Sant’Anna Carvalho A, Riera R. Adolescent pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2017; Volume 8:137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez GB, Borquez A, Case KK, Wheelock A, Vassall A, Hankins C. The cost and impact of scaling up pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a systematic review of cost-effectiveness modelling studies. [Internet]. 2013. Mar [cited 2019 Jun 10]; 10(3): Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar S, Corso P, Ebrahim-Zadeh S, Kim P, Charania S, Wall K . Cost-effectiveness of HIV Prevention Interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. EClinicalMedicine. 2019; 10:10–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.B Holmes KK. Major Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions to Prevent HIV Acquisition; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamieson L, Gomez G, Rebe K et al. The impact of self-selection based on HIV risk on the cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis in South Africa. [Internet] AIDS: January 30, 2020. Available from doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.