Abstract

Objective:

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC; malignant ascites or implants) occurs in approximately 45% of advanced gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) patients and associated with a poor survival. The molecular events leading to PC are unknown. The YAP1 oncogene has emerged in many tumor types, but its clinical significance in PC is unclear. Here we investigated the role of YAP1 in PC and its potential as a therapeutic target.

Methods:

Patient-derived PC cells, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and orthotopic (PDO) models were used to study the function of YAP1 in vitro and in vivo. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and single-cell RNA-Seq (sc-RNA-Seq) were used to elucidate the expression of YAP1 and PC cell heterogeneity. LentiCRISPR/Cas9 knockout of YAP1 and a YAP1 inhibitor were used to dissect its role in PC metastases.

Results:

YAP1 was highly upregulated in PC tumor cells, conferred CSC properties and appeared to be a metastatic driver. Dual staining of YAP1/EpCAM and sc-RNA-Seq revealed that PC tumor cells were highly heterogeneous, YAP1high PC cells had CSC-like properties, and easily formed PDX/PDO tumors but also formed PC in mice, while genetic knockout YAP1 significantly slowed tumor growth and eliminated PC in PDO model. Additionally, pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 specifically reduced CSC-like properties and suppressed tumor growth in YAP1 high PC cells especially in combination with cytotoxics the in vivo PDX model.

Conclusions:

YAP1 is essential for PC that is attenuated by YAP1 Inhibition. Our data provide a strong rationale to target YAP1 in clinic for GAC patients with PC.

Keywords: YAP1, gastric adenocarcinoma, peritoneal metastases, cancer stem cells

Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) is a major health problem in the United States and globally. In the United States, 27,510 new cases of GC and 11,140 deaths from GAC are expected in 2019(1). In general, more than 90% of all cancer-associated deaths are caused by metastases(2). Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC; malignant ascites or cells from implants) affects ~45% of GAC patients(3). PC is a challenge for the patients and for the treating team alike, and the survival of patients with PC is short (4–10). Very little, in terms of molecular biology and potential therapeutic targets, is known for this disease. PC currently imposes a serious unmet need. Deeper understanding of PC at the molecular level could uncover drivers of this disease and reveal rational therapeutic approaches.

Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) is a transcriptional coactivator that developmentally regulates organ size and proliferation(11, 12). YAP1 is frequently overexpressed in several cancer types and plays an oncogenic role in cancer progression(13–15). YAP1 overexpression and its activation (nuclear localization) correlate with poor outcomes in several tumor types (15–17). We have reported that YAP1 is overexpressed in esophageal cancers and confers CSC properties (13), endows an aggressive phenotype, and leads to therapy resistance (14, 18, 19). YAP1 is often the terminal node of many oncogenic pathways(20) and facilitates resistance to therapy(21).

The role of YAP1 in cancer metastases is emerging. Overexpression of YAP1 in cancer cell lines can promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and metastases(22). Lamar et al. reported that YAP1 promotes metastases in breast cancer and melanoma through its TEAD-interaction domain(2). A study from Massague and colleagues showed that L1CAM drives transcriptional programs for metastasis initiation through upregulation of YAP1 and myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF) in breast cancer(23). However, the expression and functional role of YAP1 in GAC with PC is unknown, and whether YAP1 can be a therapeutic target remains unexplored.

In this study, by using patient-derived PC cells, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and patient-derived orthotopic (PDO) models, we show that YAP1 is highly upregulated in PC tumor cells, plays an essential role in conferring CSC properties, and appears to be a metastatic driver. We observed that PC tumor cells are heterogeneous and that YAP1high PC cells have an aggressive phenotype, acquire CSC-like properties, and easily form tumors and PC in the PDX and PDO models, while the knockout of YAP1 by LentiCRISPR/Cas9 significantly slows tumor growth and PC in mice. Additionally, pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 strongly reduced the aggressive phenotype, CSC-like properties, and suppresses tumor growth in the PDX models. Our results suggest that YAP1is essential for PC and could be a promising target for therapy against PC.

Methods

Patients and ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. All patients who volunteered to provide research specimens signed an approved written consent document.

More detailed materials and methods can be found in the online Supplementary Methods.

Results

YAP1 is highly expressed only in PC malignant cells and peritoneal biopsy tissues

PC cells (from ascites) represent a complex tumor microenvironment that includes tumor cells, stromal cells, and immune cells. We profiled PC cells by CyTOF in 20 PC specimens using notable genes representing different cell types and signaling activation including YAP1 (Supplemental Table 1) and found that YAP1 was highly expressed in PC specimens and mainly enriched in tumor cells that co-expressed with cytokeratin and EpCAM but less co-existed with non-epithelial markers-vimentin or CD3 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. YAP1 is highly expressed only in PC malignant cells and peritoneal biopsy cancer cells.

A. CyTOF analysis of PC cell composition in 20 PC samples using epithelial markers EpCAM, cytokeratin and nonepithelial marker-vimentin, CD3 as well as YAP1 as described in Materials Methods. B. Expression of YAP1 was determined by IHC staining using anti-human YAP1 antibody in PC cell block slides (top) and peritoneal biopsy tissue formalin- fixed paraffin-embedded slides (bottom). scale bar:20μm; C. Representative PC cases were stained by dual-immunofluorescent staining of YAP1 and EpCAM, an epithelial tumor marker as described as Materials &Methods; Scale: 2520μm; D. Representative PC cases were co-stained YAP1 with immune marker CD45, macrophage CD163 and stromal marker vimentin by dual-immunofluorescence staining using their antibodies respectively. Scale: 2520μm; E. The association of YAP1 expression with GC patients’ survival in 631 advanced GAC patients from TCGA database (kmplot.com). p<0.001.

To elucidate the expression patterns of YAP1 in PC cells (from ascites and peritoneal biopsies), we stained PC specimens from 123 patients using IHC/immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 1B, YAP1 was expressed mostly in tumor cells in PC specimens by IHC (ascites cells [top] and biopsies [bottom]). The expression patterns varied among cases but YAP1 was mostly in the nucleus and some staining was noted in the cytoplasm of tumor cells in some PC cases. In the biopsies (Fig. 1B, bottom), YAP1 was strongly expressed in PC tumor cells that were surrounded by fibrosis and stromal cells which further confirmed by dual immunofluorescent staining of YAP1 with other immune and stromal markers. As indicated in Figure 1C in representative PC cases, YAP1 expression was enriched in malignant tumor cells, while fewer YAP1expression in CD45+ immune cells, vimentin+ stromal cells, or CD163+ macrophages (Figure 1D). In mRNA level, YAP1 was highly expressed in malignant PC cells compared to normal and adjacent non-tumorous cells by Q-PCR in sorted EpCAM+ cells and CD45+/EpCAM− cells (Supplemental Fig.1A–1C) which was further confirmed by multi-flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig.1D). Stratification of GAC patients by YAP1 expression revealed that YAP1 level was significantly associated with shorter survival in 631 advanced GAC patients (Fig.1E) This suggests that YAP1 overexpression is a poor prognosticator and may play an important role in PC.

Heterogeneity of malignant PC cells by YAP1/EpCAM dual immunofluorescent staining and scRNA Seq

EpCAM is an established diagnostic biomarker for epithelial malignancies(24, 25). We co-stained EpCAM and CD45 using immunofluorescence and found EpCAM had membranous staining in PC tumor cells, clearly distinguishable from CD45 stained immune cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). Then, we double-stained YAP1 and EpCAM in 123 PC samples using dual-immunofluorescence and noted membranous EpCAM and nuclear/nuc-cyto YAP1 co-expressing in PC tumor cells in 55 cases (45%) (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, EpCAM and YAP1 are not always co-expressed in PC tumor cells. Nearly, 55% of PC samples had discrepant expression of YAP1 and EpCAM. As shown in Fig. 2A, some PC tumor cells shared the membranous expression of EpCAM and nuclear YAP1(red arrow), while others expressed only nuclear YAP1 (white arrow) or membranous EpCAM (green arrow) indicating tumor cell heterogeneity within and among PC samples. The proportion of YAP1 and EpCAM shared expression or either alone is shown in Figure 2B. sc-RNA-Seq in additional 20 PC samples was performed(26) to further demonstrate tumor heterogeneity. As shown in Fig. 2C, among tumor cell clusters (here we excluded all immune cells), expression of YAP1 and EpCAM was heterogeneous with some cells co-expressed both YAP1 and EpCAM (orange), while some tumor cell clusters expressed only EpCAM (green) or only YAP1(red). The status of EpCAM+ or YAP1+cells alone or shared cells from sc-RNA Seq is shown in Figure 2C (right). On the basis of these results, we hypothesized that YAP1 or/and EpCAM positive cells may represent different tumor cell states with varying metastatic potential.

Figure 2. Heterogeneity in PC cells by YAP1/EpCAM co-staining and sc-RNA Seq.

A. Expression of YAP1 (red) and EpCAM (green) was determined by dual-immunofluorescence staining using anti-mouse EpCAM and anti-YAP1 rabbit antibody in 123 cases of PC. Discrepant expression of YAP1 and EpCAM within and between PC samples was noted. Nuclear YAP1 (red arrow) and membranous EpCAM (green arrow) within a specimen or among PC specimen were demonstrated. B. The numbers of PC cases expressing both YAP1 and EpCAM; and those with high YAP1 or high EpCAM, and expressing only YAP1 or only EpCAM are shown in the table. C. Expression analysis of EpCAM and YAP1 was performed by sc-RNA-Seq in tumor cell clusters from 20 PC samples as described in online Materials&Methods.

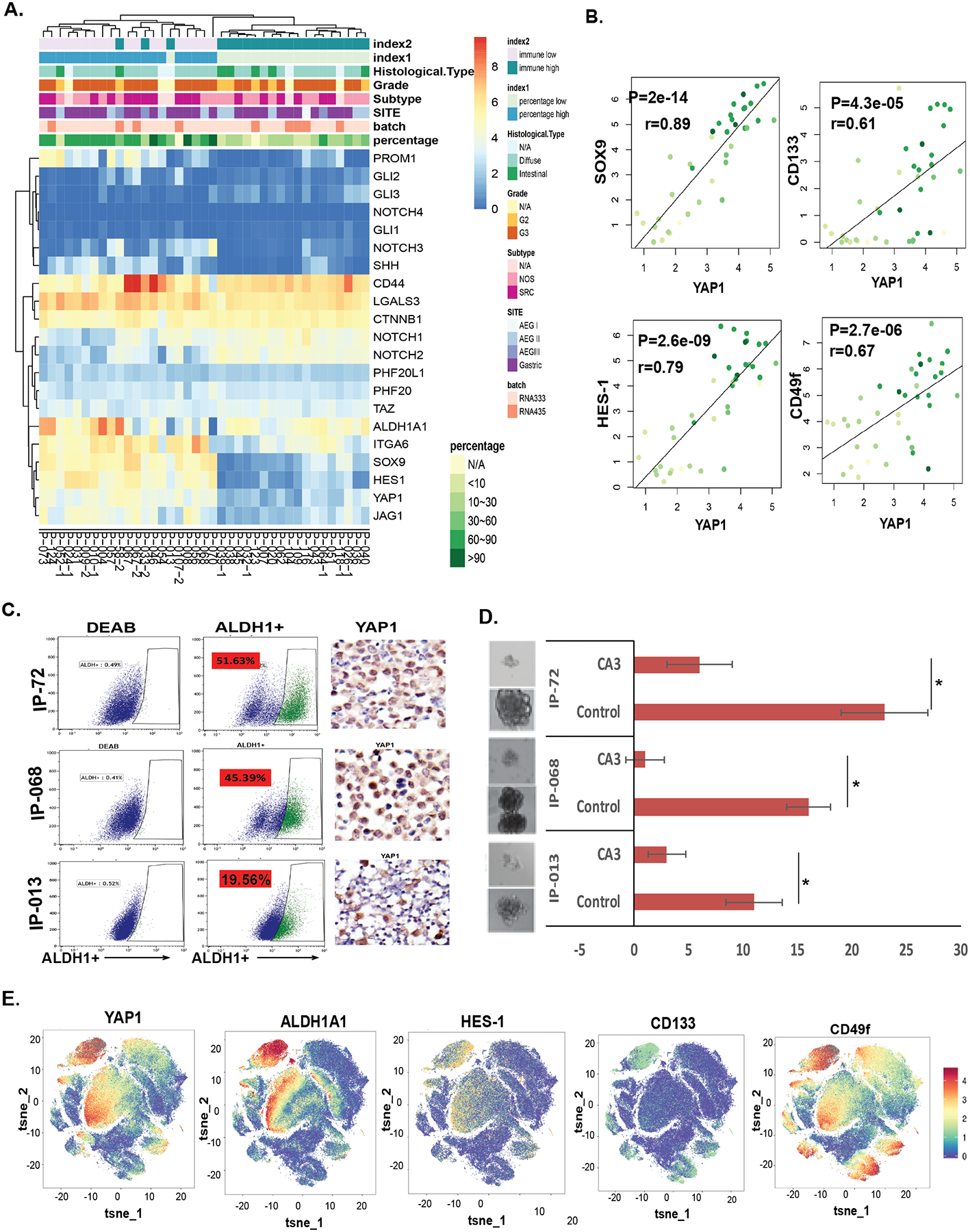

YAP1 expression highly associates with CSC properties

Analyses of the expression levels of 21 stem cell associated genes including genes in Hippo, Wnt, Notch, Hh pathways, and known CSC-associated genes- ALDH1A1, ITGA6 (CD49f), PROM1 (CD133), and CD44 in bulk RNA Seq data of 39 PC samples, we found that YAP1 expression is associated with CSC genes (Fig. 3A&3B). YAP1 expression significantly correlates with CSC genes such as SOX9 (P=2e-14), HES1 (p=2.6e-09), PROM1 (CD133) (p=4.3e-05), and ITGA6 (CD49f) (p=2.7e-06) (Fig. 3B). SOX9 is a gastrointestinal tract stem cell marker and a reported YAP1 target that controls CSC features in esophageal cancer12. HES1 is a Notch signaling target and has been reported to regulate CSC features in the gastrointestinal tract, and CD133 and CD49f are reported CSC markers in many tumor types(27–29). Furthermore, YAP1 expression correlated with the population of ALDH1+ cells in PC specimens (Fig. 3C). Functionally, we have assessed the tumor sphere formation capacity in these PC cases (IP-013, IP-068 and IP-72) and found that YAP1 nuclear expression is highly correlated with their tumor sphere forming capacity which significantly suppressed by YAP1 inhibitor CA3 (Fig.3D). CyTOF analyses further revealed that YAP1 expression is highly associated with ALDH1, HES1, CD133, and CD49f (Fig. 3E), suggesting that high YAP1 expression correlates with a CSC signature in PC.

Figure 3. YAP1 expression is strongly associated with CSC properties in PC specimen by RNA-Seq.

A. RNA-Seq profiling of 39 PC samples using a panel of notable CSC-related genes. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed on the normalized RNA expression data of these genes. B. Significant associations between YAP1 and notable CSC-related markers SOX9, HES1, CD133, and CD49f are depicted in scatter graphs from RNA-Seq data in the 39 PC samples. P values were calculated by the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. C. Isolated ascites cells from three PC samples (IP-013, IP-068 and IP-72) were labeled for the ALDH1+ cell population using an ALDH1 labeling kit. Shown are the ALDH1+ percentage of the population in each PC sample and IHC staining of YAP1 in relative PC cell blocks. D. Tumor sphere capacity of these three PC samples treated with or without YAP1 inhibitor CA3 at 0.5μM were determined as described in Materials and Methods. E. Expression of YAP1 and CSC markers ALDH1, HES1, CD133, and CD49f was analyzed in CyTOF data of 10 separated PC samples.

YAP1high PC cells easily form PDXs in mice irrespective of PC tumor cell purity

We hypothesized that YAP1high PC cells represent undifferentiated cells with CSC traits and have high tumorigenicity and metastatic potential. To test this hypothesis, we generated PDX tumors from PC specimens by subcutaneously injecting PC cells into nude/SCID mice (5×106 cells from one patient per mouse). Of the 57 cases, 19 (33.3%) generated PDXs successfully. Upon detailed analyses, we noted that the PDX tumor formation is significantly associated with YAP1 nuclear expression, while not associated with tumor cell purity in these PC specimen (Supplemental Table 2). Of the 19 mice that formed PDXs, 16 had YAP1 high expression in nuclear or nuclear/cytoplasm of tumor cells regardless of tumor cell percentage and EpCAM expression; some had either low tumor purity and low EpCAM expression. As shown in Fig. 4A, two representative PC samples, IP-116 and IP-013, with YAP1high staining but low EpCAM expression (IP-116) or no EpCAM expression (IP-013), easily formed PDXs and even formed PC metastasis in nude mice (Fig. 4A, right). The morphology of these PDX tumors and the expression of YAP1 seen in the patient PC samples were preserved in these PDX tumors (Fig. 4A [bottom]. High YAP1 nuclear expression was found in more PDX tumors from additional PC samples (Supplemental Fig. 3). To further elucidate YAP1 high PC cells represent CSCs and tumor initiating cells, we sorted EpCAM+/YAP1− or EpCAM+/YAP1+ and EpCAM−/YAP1+ cells after depleting of CD45+ cells in PC sample as indicated in Supplemental Figure 4. After confirming the cells expression of YAP1 or YAP1/EpCAM using dual staining, we injected the EpCAM+/YAP− or EpCAM+/YAP1+ (Supplemental 4A lower right) and EpCAM−/YAP1+ cells (Supplemental 4A lower left) subcutaneously into NOD/SCID mice (1×105 cells per mouse). In around 11 days, the tumorigenicity of these cells were observed and we found that every mouse (5 out 5 mice) in EpCAM−/YAP1+ cells had tumors at 11 days, while only 50% of EpCAM+/YAP1− or EpCAM+/YAP+ group (2 out of 4 mice) had tumors indicating EpCAM−/YAP1+ cells are more tumorigenic than that of EpCAM+/YAP−or EpCAM+/YAP+ cells (Supplemental 4B&4C). This further confirms our hypothesis that YAP1 high cells represent CSCs and have high tumorgenicity and might have high metastatic potential to form PC.

Figure 4. YAP1high PC cells easily form PDXs in mice irrespective of PC tumor cell purity or EpCAM expression.

A. Samples harvested from malignant ascites in representative PC cases (IP-116 and IP-013) underwent immunofluorescence (IF) staining of YAP1 and EpCAM and were also injected into nude mice for generation of PDX tumors, which were then stained by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) to determine morphology and subjected to dual-immunofluorescence staining with anti-mouse EpCAM and anti-YAP1 rabbit antibody. B. Successful knockout of YAP1 in GA051816 cells using LentiCRISPR/Cas9. C. Tumor sphere formation (left) and invasion capacity (right) in GA051816 parental cells were compared with that of the YAP1 knockout cells. **p<0.01. Experiments repeat at least three times. D. GA051816 PC cells with or without YAP1 knockout were labeled for ALDH1+ cell population using an ALDH1 labeling kit. The ALDH1+ population in each group is shown in the bar graph. E. Tumorigenicity at serial dilution was assessed in GA051816 control cells compared with YAP1 knockout cells on day 21 after cells inoculation. 10 mice per group. F. Bulk RNA-Seq was performed in GA051816 control cells and YAP1 knockout cells, and critical mediators in CSCs (red arrow) and EMT signaling (green arrow) were identified and depicted.

Genetic knockout of YAP1 reduced tumorigenicity of YAP1high PC cells in the PDX model

To dissect if YAP1 played a critical role in tumorigenesis and metastases, we knocked out YAP1 using LentiCRISP/Cas9 in YAP1High GA051816 cells which were generated from IP-013 PC cells. YAP1 knockout guide RNAs was listed in Supplemental Table 3 and detailed in online Supplemental Methods. Successful knockout of YAP1 strikingly decreased tumor sphere formation and invasive capacity in two individual subclones of GA051816 as compared to parental cells (Figs. 4B & 4C). Knockout YAP1 significantly decreased CSCs ALDH1+ population (19.5% to 2.07%) (Fig. 4D). Further, serial dilutions of 1×105, 1×104, 1×103 cells from control and YAP1-knockout GA051816 cells were injected subcutaneously in nude mice. YAP1 knockout significantly delayed and reduced tumor growth at each dilution suggesting that YAP1 is critical for GAC progression (Fig.4E).

To examine the mechanism through which YAP1 regulates the acquisition of stemness and tumorigenicity, RNA-Seq studies found depletion of YAP1 significantly decreased the expression of genes whose expression is associated with CSCs signaling—SOX9, HES1, EGR3, and ALDH3A1(red arrow) and EMT signaling-CDH11, DKK1, MFAP5 and IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 (green arrow) shown in Fig.4F. These EMT genes were significantly decreased upon knockdown of YAP1 in GA051816 cells with FDR q-value at 2.64e−6 (Supplemental Table 4). Most importantly, most YAP1 regulated CSCs and EMT genes are associated with poor survival in GC patients (Supplemental Fig.5) suggesting that YAP1 mediated stemness and PC in part through regulation of CSCs and EMT.

YAP1 is essential for PC in the PDO model

To further explore the role of YAP1 in PC, we transfected YAP1high GA051816 cells with mCherry-Luciferase and confirmed high luciferase activity in mCherry-Luciferase GA051816 cells (Fig. 5A). mCherry-Luciferase GA051816 cells with or without depletion of YAP1 (1×105 cells) were mixed with Matrigel and injected into the stomach wall of NOD/SCID mice (PDO model). Tumor growth in the stomach wall and metastases to the peritoneal cavity or other organs were monitored by bioluminescence weekly. As shown in Figs. 5B–5D, among mice given control GA051816 cells, 100% (4/4) formed tumors in the stomach and 75% (3/4) had PC, while among mice given YAP1−knockout GA051816 cells, only 33% (1/3) formed a small tumor in the stomach, and none (0/3) had PC (Fig. 5D, left). Furthermore, YAP1 knockout significantly prolonged overall survival compared with that in mice with parental cells (Fig. 5D, right).

Figure 5. YAP1 is essential for PC metastases in PDO model.

A. GA051816 PC cells transfected with mCherry-Luciferase were visualized under microscope (top). High luciferase activity in mCherry-Luciferase transfected GA051816 cells (bottom)) was confirmed by luciferin. B. mCherry-Luciferase GA051816 control or YAP1 knockout cells were injected into the stomach wall of NOD/SCID mice, and tumor growth in the stomach wall and metastases to the peritoneal cavity or other organs were monitored by bioluminescence weekly. C. Representative image of peritoneal metastasis of GA051816 parental cells and no metastasis in GA051816 YAP1 knockout cells. D. Survival of mice implanted with GA051816 parental cells compared with mice implanted with GA051816 YAP1 knockout cells. E. Analysis of ALDH1 labeling using ALDH1 labeling kit in cells from primary tumor and PC from same mouse. Results are repeated in at least three mice. F. Expression of YAP1, SOX9, and other CSC markers was detected in primary and PC cells from the same mouse using Western blot and quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Tumor sphere formation capacity is depicted as well. G. Association of expression of YAP1 and ALDH1 was detected using dual immunofluorescence in GA051816 PC cells.

Further analyses of primary tumor cells with paired PC cells in the PDO models from YAP1high control group, we found that the PDO-PC cells were enriched in CSCs with high YAP1 and SOX9 expression, formed larger tumor spheres, and had a high ALDH1+ population compared with the primary tumor cells (Figs. 5E&5F). The expression of YAP1 was strongly associated with that of ALDH1 (Fig. 5G). Similarly, other CSC genes were significantly upregulated in PC cells compared to primary tumor cells of the PDO model by Q-PCR (Fig. 5F, bottom).

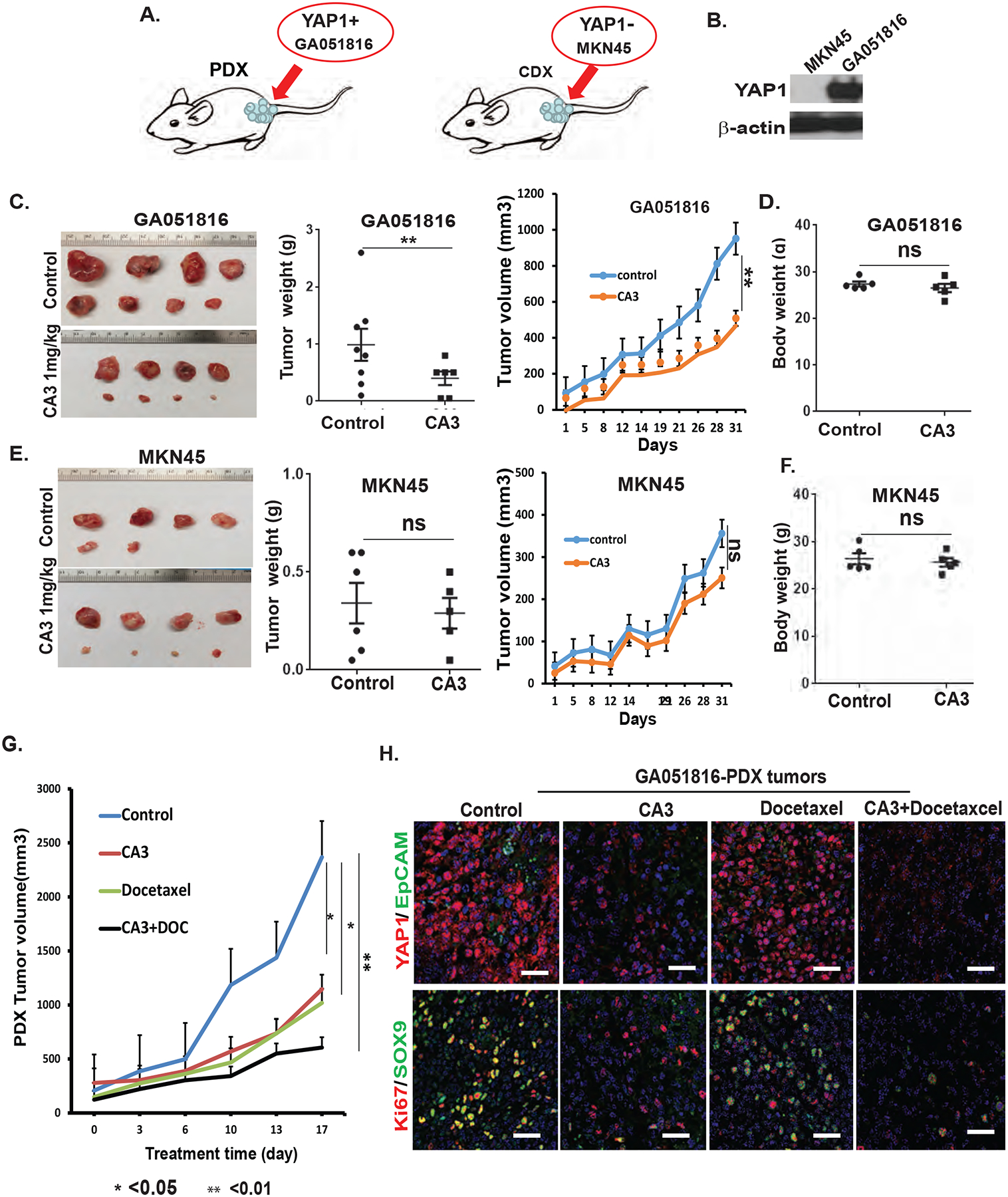

Pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 reduced CSC properties and PDX tumor growth

CA3, a novel specific YAP1 inhibitor, was reported to inhibit YAP1 expression and its transcriptional activity in esophageal cancer.(30) We aim to investigate whether pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 by CA3 reduce CSC properties and PDX tumor growth in PC. We observed that CA3 suppressed YAP1 expression, tumor sphere formation, and ALDH1+ population in aggressive GA051816 cells (Fig.6A–6C). Three additional PC cells were also investigated. CA3 strongly suppressed YAP1 expression and reduced tumor sphere formation in all three PC samples (Fig. 6D). Further, we noted that cells with YAP1high expression were sensitive to CA3 at lower doses (0.25 μM and 0.5 μM), while two stable YAP1 knockout clones (YAP1 KO1 and YAP1 KO2) were resistant to CA3 (Fig.6E). In addition, CA3 effectively suppressed colony formation and tumor sphere formation in YAP1high GA051816 cells but not in MKN45 GC cells with no YAP1 (Fig. 6F&6G). These data indicate that the antitumor activity of CA3 depends on YAP1 expression.

Figure 6. Pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 specifically suppress patient-derived cells growth and colony formation in YAP1 high cells.

A, Expression of YAP1 was determined by immunoblotting in GA051816 cells treated with CA3 at indicated dosage for 48 hours. B. Tumor sphere formation in GA051816 cells treated with CA3 at different dosages was assessed. C. GA051816 PC cells treated with CA3 at 0.5 μM for 48 hours and then labeled for ALDH1+ cell population using an ALDH1 labeling kit. The ALDH1+ population in each group is shown in the bar graph. Data represent as mean and standard deviation from three experiments. D. Expression of YAP1 was determined by immunoblotting in three additional PC cells from patients (GA070716, GA011017, and GA011317) treated with CA3 at 1 μM for 48 hours (upper). Tumor sphere formation for GA070716, GA011017, and GA011317 cells treated with CA3 at 1 μM for 10 days (lower panel). E. Cell viability in GA051816 parental and YAP1 knockout cells treated with CA3 at the indicated dosage for 3 days. YAP1 high parental cells are more sensitive to CA3. **p<0.01. F&G. Colony formation and tumor sphere formation were assessed in GA051816 (YAP1 high) and MKN45 (YAP1 none) GC cells treated with CA3 at the dosage indicated. Colony number and tumor sphere number were calculated after 14 days. **p< 0.01; ***p<0.0001.

The specificity of CA3 targeting of YAP1 was also demonstrated in vivo PDX. We injected patient derived YAP1 high GA051816 cells and MKN45 GAC cells with YAP1 none subcutaneously (Fig.7A&7B) and treated mice with CA3 at only 1 mg/kg three times per week. Interestingly, we found that CA3 significantly suppressed the growth of implanted YAP1high GA051816 cells (Fig.7C) but had minimal effect in MKN45 (no YAP1) cells (Figs. 7E) with minimal side effects (body weight reduction) in both GA0518 and MKN45 models (Fig.7D&7F). Moreover, when CA3 was combined with the commonly used docetaxel (Supplemental Fig.6A), the reduction in PDX growth was significantly amplified (Figs. 7G & Supplemental Fig.6B&6C). Dual staining of YAP1/EpCAM and Ki67/SOX9 in these PDX tumors revealed that CA3 dramatically decreased the expression of YAP1 and SOX9 in CA3 group, while docetaxel was less effective on inhibition of YAP1 and SOX9 expression but more effective in reducing Ki67+ proliferating cells. The combination of CA3 and docetaxel utmost suppressed expression of both YAP1/SOX9 and Ki67+ population (Fig. 7H) suggesting a great value of targeting YAP1 in combination with cytotoxics in GAC patients with PC.

Figure 7. Pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 significantly inhibit PDX tumor growth in YAP1 high PC cells in Vivo.

A. Diagram demonstrates the PDX tumor formation in GA051816 YAP1high and CDX tumor formation in MKN45 GC cell line with no YAP1expression. B. Expression of YAP1 was detected by western blotting in both MNK45 and GA051816 cells; C. Representative tumors in GA051816 PDX tumors and treated with CA3 at 1mg/kg, three time a week for three weeks are shown, and tumor weights, tumor volumes from each group were calculated. D. mouse body weights in GA051816 PDX tumors were calculated (E) Representative tumor images, tumor weight, tumor volume in MKN45 CDX model treated with CA3, three times a week, 1mg/kg, IP injection. F. mouse body weights in MKN45 CDX tumors were calculated. G. YAP1 inhibitor CA3 enhances the effects of docetaxel in inhibiting growth of PDX tumors. GA051816 patient-derived cells (2×106 cells) were injected subcutaneously in nude mice, at two sites (left and right) per mouse and treated with CA3 alone, docetaxel alone, or the combination with five mice per group for three weeks. Tumor volumes were measured twice per week for three weeks and calculated as described in Materials. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. H. Dual immunofluorescence staining of YAP1/EpCAM and Ki67/SOX9 were performed in PDX tumors of four groups as described in Materials and Methods. Scale bar, 20μm.

Discussion

GAC patients with PC have a poor quality of life and lack effective therapy options. Deeper understanding of PC at the molecular level and uncover novel therapeutic targets using patient-derived cells and models are urgently needed. Although YAP1 is a known oncogene that is upregulated in many tumor types, the role of YAP1 in mediating PC has not been reported. Here, we used patient-derived PC cells in vitro and in vivo to document that YAP1 is overexpressed in malignant PC cells, confers CSC properties, contributes to tumor cell heterogeneity, tumorigenicity, and is a key determinant of PC. RNA-Seq on PC samples confirmed that YAP1 is significantly associated with CSC biomarkers SOX9, HES1, CD133 and CD49f, and ALDH1A1. Intriguingly, YAP1high PC cells readily formed PDXs irrespective of PC tumor cell purity or EpCAM expression. Pharmacologic and genetic knockout of YAP1 reduced CSC properties, PDX tumor formation, and PC in PDO models. These findings define that YAP1 is strongly expressed in PC tumor cells and promotes PC which were reversed by inhibition of YAP1 in patient-derived models. Thus, YAP1 appears to be a valid target to pursue in GC patients with PC.

YAP1 has been reported to play an important role in cancer progression and metastases.(15, 18, 31, 32) However, the majority of these studies are limited to cancer cell lines. Using pancreatic cancer cell lines, it was reported that YAP1 overexpression promotes EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells(33) and YAP1 contributes to NSCLC invasion and migration via the transcription co-factor TEAD in non–small cell lung cancer cell lines (34). Lamar et al. noted that YAP1 promoted metastases through its TEAD-interaction domain in breast and melanoma cancer cell systems using tail-vein injection, which also primarily used established breast and melanoma cancer cell lines(2). However, in our study, we worked predominantly with patient-derived PC cells and patient-derived in vivo PDX or PDO models. We first documented that high expression of YAP1 was mostly in malignant PC cells. Then, using in vivo models, including a model of PDO PC, we clearly demonstrated the role of YAP1 in promoting PC. Knockout of YAP1 completely eliminated formation of PC. Altogether, we demonstrated that YAP1 plays an essential role in PC.

PC is established through a multi-step process, including downregulation of E-cadherin and involvement of CD44, selectins, matrix metalloproteinases, vascular endothelial growth factors, other growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines(35). Single-cell analysis previously revealed a CSC program in human metastatic breast cancer cells(36). We have previously reported that YAP1confers CSC properties in both non-tumor cells and tumor cells (37) and mediates chemoresistance and radiation resistance(14, 19, 20). Our RNA-Seq and CyTOF confirmed that YAP1 is significantly associated with other CSC markers. Interestingly, RNA Seq in patent-derived GA051816 cells and their YAP1 knockout clones demonstrated that YAP1 significantly regulates genes related to CSCs (SOX9, HES-1 and ALDH3A1) and EMT signaling (CDH11, DKK1 and IGFBP2,3 etc) and these genes are significantly associated short survival. Strikingly, YAP1high PC cells easily formed PDX regardless of EpCAM expression or tumor cell purity, and only YAP1high cells formed PC in mice. Our data are consistent with a report suggesting that metastasis-initiating cells have CSC properties (i.e., express SOX2 and SOX9) that allow progression of metastases(38). Another report suggested that L1CAM+ tumor cells-initiated metastases through upregulation of YAP1 and MRTF and that L1CAM and YAP1 signaling enabled the outgrowth of metastasis-initiating cells(23). Similarly, a more recent study demonstrated that tumor metastasis to lymph nodes requires YAP-dependent metabolic adaptation (39).

Patients with PC are in dire need of effective therapies (5–7). Our data suggest that YAP1 is a valuable target to pursue. Our in vitro and in vivo data documents that CA3 specifically targets YAP1high patient-derived cells but not MKN45 cells, which lack YAP1, assuring the specificity of the inhibition of YAP1 by CA3 in PC cells. Furthermore, CA3 combined with docetaxel improved the efficacy of docetaxel in vivo in a PDX model. Dual staining of YAP1/EpCAM and Ki67/SOX9 in these PDX tumors uncovered that CA3 reduced the population of CSCs with YAP1+ and SOX9+, while docetaxel was more effective in killing Ki67+ proliferating cells. The combination of CA3 and docetaxel utmost eliminated both YAP1/SOX9 positive CSCs and Ki67 proliferating cells (Figure 7H). This provides a strong rationale for a clinical trial of targeting YAP1 in combination with conventional chemotherapy in GC patients with PC.

In conclusion, our compelling data, for the first time, demonstrate that YAP1 is highly expressed in tumor cells of PC specimens, confers CSC properties, contributes to tumor cell heterogeneity, and promotes PC but this property can be reversed by pharmacologic and genetic manipulations. Importantly, in the PDO-PC model, knockout of YAP1 can eliminate PC. Altogether, our study provides a strong rationale to target YAP1 in clinic for GAC patients with PC.

Supplementary Material

What is already known on this subject?

Gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) is a major health problem in the United States and globally; often diagnosed at advanced stages. Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC; malignant ascites or cells from implants) is common affecting 45% GAC population. Patients with PC have very poor outcomes with the limited current treatment options. YAP1 has been implicated in many tumor types, but its clinical significance in PC is unclear.

What are the new findings?

In this study, by extensive utilization of patient-derived PC cells, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and orthotopic (PDO) models, we demonstrated that YAP1 is highly upregulated in malignant PC cells, plays an essential role in conferring cancer stem cell (CSC) properties, governs tumor cell plasticity, and appears to be a metastatic driver. We observed that PC cells are heterogeneous and that YAP1high PC cells have an aggressive phenotype and CSC-like properties, and easily form tumors and PC in the PDX and PDO models, while genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of YAP1 strongly reduces aggressive phenotype, CSC-like properties, and suppresses tumor growth in the PDX model and blocked PC in the PDO model. Our results suggest that YAP1 plays an essential role in PC and could be pursued as a novel target of therapy against PC.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our results establish the molecular foundation for YAP1-mediated PC, its progression, and provide a strong rationale for developing a clinical trial to target YAP1 in combination with current chemotherapy such as docetaxel agent in GAC patients with PC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Sheng Ding and Min Xie from the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California, for their generous providence of CA3 used in this study. We also appreciate Sarah Bronson, scientific editor from Department of Scientific publications of MDACC for her excellent edition on English of this manuscript. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant DF56338, which supports the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center (S. Song); an MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant (3-0026317 to S. Song); and grants from Department of Defense (CA160433 to S. Song); and the National Institutes of Health (CA129906, CA138671, and CA172741 to J.A. Ajani).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data and materials availability:

All dataset and materials generated from this study are available for scientific community upon request.

RNA-Seq data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA). The datasets can be fully accessed under the accession number EGAS00001003180. Further information about EGA can be found on https://ega-archive.org (the EGA of human data consented for biomedical research: http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v47/n7/full/ng.3312.html).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69, 7–34 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamar JM, Stern P, Liu H, Schindler JW, Jiang ZG, Hynes RO, The Hippo pathway target, YAP, promotes metastasis through its TEAD-interaction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, E2441–2450 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitayama J, Intraperitoneal chemotherapy against peritoneal carcinomatosis: current status and future perspective. Surg Oncol 23, 99–106 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, Schiller D, Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. Journal of surgical oncology 104, 692–698 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, Fontaumard E, Brachet A, Caillot JL, Faure JL, Porcheron J, Peix JL, François Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN, Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer 88, 358–363 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyrhönen S, Kuitunen T, Nyandoto P, Kouri M, Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. British journal of cancer 71, 587–591 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Gastric cancer 20(Suppl 1),111–121 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satoi S, Fujii T, Yanagimoto H, Motoi F, Kurata M, Takahara N, Yamada S, Yamamoto T, Mizuma M, Honda G, Isayama H, Unno M, Kodera Y, Ishigami H, Kon M, Multicenter Phase II Study of Intravenous and Intraperitoneal Paclitaxel With S-1 for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients With Peritoneal Metastasis. Annals of surgery, 265, 397–401 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata S, Yamamoto H, Yamaguchi T, Kaida S, Ishida M, Kodama H, Takebayashi K, Shimizu T, Miyake T, Tani T, Kushima R, Tani M, Viable Cancer Cells in the Remnant Stomach are a Potential Source of Peritoneal Metastasis after Curative Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 23, 2920–2927 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi C, Yang B, Chen Q, Yang J, Fan N, Retrospective analysis of adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy effect prognosis of resectable gastric cancer. Oncology 80, 289–295 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tumaneng K, Russell RC, Guan KL, Organ size control by Hippo and TOR pathways. Curr Biol 22, R368–379 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tumaneng K, Schlegelmilch K, Russell RC, Yimlamai D, Basnet H, Mahadevan N, Fitamant J, Bardeesy N, Camargo FD, Guan KL, YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K-TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nat Cell Biol 14, 1322–1329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song S, Ajani JA, Honjo S, Maru DM, Chen Q, Scott AW, Heallen TR, Xiao L, Hofstetter WL, Weston B, Lee JH, Wadhwa R, Sudo K, Stroehlein JR, Martin JF, Hung MC, Johnson RL, Hippo coactivator YAP1 upregulates SOX9 and endows esophageal cancer cells with stem-like properties. Cancer Res 74, 4170–4182 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song S, Honjo S, Jin J, Chang SS, Scott AW, Chen Q, Kalhor N, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, Albarracin CT, Wu TT, Johnson RL, Hung MC, Ajani JA, The Hippo Coactivator YAP1 Mediates EGFR Overexpression and Confers Chemoresistance in Esophageal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 21,2580–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang W, Tong JH, Chan AW, Lee TL, Lung RW, Leung PP, So KK, Wu K, Fan D, Yu J, Sung JJ, To KF, Yes-associated protein 1 exhibits oncogenic property in gastric cancer and its nuclear accumulation associates with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 17, 2130–2139 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muramatsu T, Imoto I, Matsui T, Kozaki K, Haruki S, Sudol M, Shimada Y, Tsuda H, Kawano T, Inazawa J, YAP is a candidate oncogene for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 32, 389–398 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, George J, Deb S, Degoutin JL, Takano EA, Fox SB, group AS, Bowtell DD, Harvey KF, The Hippo pathway transcriptional co-activator, YAP, is an ovarian cancer oncogene. Oncogene 30, 2810–2822 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moroishi T, Hansen CG, Guan KL, The emerging roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nature reviews 15, 73–79 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Sabnis AJ, Chan E, Olivas V, Cade L, Pazarentzos E, Asthana S, Neel D, Yan JJ, Lu X, Pham L, Wang MM, Karachaliou N, Cao MG, Manzano JL, Ramirez JL, Torres JM, Buttitta F, Rudin CM, Collisson EA, Algazi A, Robinson E, Osman I, Munoz-Couselo E, Cortes J, Frederick DT, Cooper ZA, McMahon M, Marchetti A, Rosell R, Flaherty KT, Wargo JA, Bivona TG, The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nature genetics 47, 250–256 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keren-Paz A, Emmanuel R, Samuels Y, YAP and the drug resistance highway. Nature genetics 47, 193–194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S, YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell 29, 783–803 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overholtzer M, Zhang J, Smolen GA, Muir B, Li W, Sgroi DC, Deng CX, Brugge JS, Haber DA, Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 12405–12410 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Er EE, Valiente M, Ganesh K, Zou Y, Agrawal S, Hu J, Griscom B, Rosenblum M, Boire A, Brogi E, Giancotti FG, Schachner M, Malladi S, Massague J, Pericyte-like spreading by disseminated cancer cells activates YAP and MRTF for metastatic colonization. Nat Cell Biol 20, 966–978 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeber A, Martowicz A, Spizzo G, Buratti T, Obrist P, Fong D, Gastl G, Untergasser G, Soluble EpCAM levels in ascites correlate with positive cytology and neutralize catumaxomab activity in vitro. BMC cancer 15, 372 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu Q, Bittencourt Mde C, Cai H, Bastien C, Lemarie-Delaunay C, Bene MC, Faure GC, Case Report: Detection and quantification of tumor cells in peripheral blood and ascitic fluid from a metastatic esophageal cancer patient using the CellSearch ((R)) technology. F1000Res 3, 12 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R, Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature biotechnology 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendelson J, Song S, Li Y, Maru DM, Mishra B, Davila M, Hofstetter WL, Mishra L, Dysfunctional transforming growth factor-beta signaling with constitutively active Notch signaling in Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 117, 3691–3702 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varillas JI, Zhang J, Chen K, Barnes II, Liu C, George TJ, Fan ZH, Microfluidic Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells and Cancer Stem-Like Cells from Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Theranostics 9, 1417–1425 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebsbach PH, Villa-Diaz LG, The Role of Integrin alpha6 (CD49f) in Stem Cells: More than a Conserved Biomarker. Stem Cells Dev 26, 1090–1099 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S, Xie M, Scott AW, Jin J, Ma L, Dong X, Skinner HD, Johnson RL, Ding S, Ajani JA, A Novel YAP1 Inhibitor targets CSCs-enriched Radiation Resistant Cells and Exerts Strong Antitumor Activity in Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 17, 443–454 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu MZ, Yao TJ, Lee NP, Ng IO, Chan YT, Zender L, Lowe SW, Poon RT, Luk JM, Yes-associated protein is an independent prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 115, 4576–4585 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KW, Lee SS, Hwang JE, Jang HJ, Lee HS, Oh SC, Lee SH, Sohn BH, Kim SB, Shim JJ, Jeong W, Cha M, Cheong JH, Cho JY, Lim JY, Park ES, Kim SC, Kang YK, Noh SH, Ajani JA, Lee JS, Development and Validation of a Six-Gene Recurrence Risk Score Assay for Gastric Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 22, 6228–6235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan Y, Li D, Li H, Wang L, Tian G, Dong Y, YAP overexpression promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Molecular medicine reports 13, 237–242 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu M, Chen Y, Li X, Yang R, Zhang L, Huangfu L, Zheng N, Zhao X, Lv L, Hong Y, Liang H, Shan H, YAP1 contributes to NSCLC invasion and migration by promoting Slug transcription via the transcription co-factor TEAD. Cell Death Dis 9, 464 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusamura S, Baratti D, Zaffaroni N, Villa R, Laterza B, Balestra MR, Deraco M, Pathophysiology and biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2, 12–18 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawson DA, Bhakta NR, Kessenbrock K, Prummel KD, Yu Y, Takai K, Zhou A, Eyob H, Balakrishnan S, Wang CY, Yaswen P, Goga A, Werb Z, Single-cell analysis reveals a stem-cell program in human metastatic breast cancer cells. Nature 526, 131–135 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song S, Ajani JA, Honjo S, Maru DM, Chen Q, Scott AW, Heallen TR, Xiao L, Hofstetter WL, Weston B, Lee JH, Wadhwa R, Sudo K, Stroehlein JR, Martin JF, Hung MC, Johnson RL, Hippo coactivator YAP1 upregulates SOX9 and endows stem-like properties to esophageal cancer cells. Cancer research, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, He L, Basnet H, Zou Y, de Stanchina E, Massague J, Metastatic Latency and Immune Evasion through Autocrine Inhibition of WNT. Cell 165, 45–60 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CK, Jeong SH, Jang C, Bae H, Kim YH, Park I, Kim SK, Koh GY, Tumor metastasis to lymph nodes requires YAP-dependent metabolic adaptation. Science 363, 644–649 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All dataset and materials generated from this study are available for scientific community upon request.

RNA-Seq data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA). The datasets can be fully accessed under the accession number EGAS00001003180. Further information about EGA can be found on https://ega-archive.org (the EGA of human data consented for biomedical research: http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v47/n7/full/ng.3312.html).