Abstract

β-1,2-linked oligomannoside residues are present, associated with mannan and a glycolipid, the phospholipomannan, at the Candida albicans cell wall surface. β-1,2-linked oligomannoside residues act as adhesins for macrophages and stimulate these cells to undergo cytokine production. To characterize the macrophage receptor involved in the recognition of C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannoside we used the J774 mouse cell line, which is devoid of the receptor specific for α-linked mannose residues. A series of experiments based on affinity binding on either C. albicans yeast cells or β-1,2-oligomannoside-conjugated bovine serum albumin (BSA) and subsequent disclosure with biotinylated conjugated BSA repeatedly led to the detection of a 32-kDa macrophage protein. An antiserum specific for this 32-kDa protein inhibited C. albicans binding to macrophages and was used to immunoprecipitate the molecule. Two high-pressure liquid chromatography-purified peptides from the 32-kDa tryptic digest showed complete homology to galectin-3 (previously designated Mac-2 antigen), an endogenous lectin with pleiotropic functions which is expressed in a wide variety of cell types with which C. albicans interacts as a saprophyte or a parasite.

The use of molecules derived from the yeast cell wall has led to the elucidation of both binding and signaling roles for lectin receptors present on macrophage membrane (48). Based on the use of mannan or zymosan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two macrophage surface proteins involved in carbohydrate recognition have been characterized. The macrophage mannose receptor (MMR) (47), a 175-kDa calcium-dependent lectin, has been described as a receptor specific for α-mannosides (49). A β-glucan receptor (5) first identified as a protein of 160 to 180 kDa (6) specific for zymosan (54) was subsequently shown to be made up of a ligand-binding 20-kDa subunit which was specific for a β-1,3-heptaglucoside (53). Based on its specificity for zymosan (43), the αM β2-integrin CR3 (Mac-1, CD11b/CD18) was also shown to serve as a macrophage β-glucan receptor. The sugar specificity of CD11b/CD18 was examined using methylated monosaccharides, and a cation-independent lectin site was located C-terminal to the I domain of CD11b (55, 57). Both methylglucosides and methylmannosides, but not mannan, were recognized by CR3 (58), showing that in contrast to MMR, CR3 could bind a wide range of individual sugar but not the corresponding polymers.

Both MMR and CR3 are involved in the phagocytosis of unopsonized, heat-killed S. cerevisiae yeasts by murine macrophages (18). Binding and phagocytosis of Candida albicans yeasts also involve the MMR (10, 32), and C. albicans stimulates macrophage secretory activities through its mannan and the binding of α-linked mannose (15, 37), although some of the activities are partly mediated by β-glucan (3). However, cumulative evidence (13, 27, 30, 31) suggests that recognition of C. albicans by macrophages may also involve a sugar interaction independent of both α-linked mannose and β-linked glucan, leading to the hypothesis of the existence of an alternative lectin system for C. albicans binding.

In contrast to S. cerevisiae mannan, C. albicans mannan displays in its acid-labile fraction—bound to the rest of the molecule by phosphodiester bridges—a special type of sugar consisting of β-1,2-linked mannopyranose units (16, 51). These oligomannoses interact with macrophages (13, 31) and stimulate these cells for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production (27). Although β-1,2-oligomannoside interaction with these cells has been shown to initiate signal transduction (25, 26), the nature of the macrophage molecule responsible for the binding of β-1,2-oligomannosides has not been characterized yet. This was the objective of the present study. For this purpose, we used the murine macrophage J774 cell line, which recognizes β-1,2-oligomannosides but is devoid of MMR expression (13). Through a series of experiments involving protein extracts of J774 cells and either S. cerevisiae or C. albicans yeast cells or a neoglycoprotein constructed with C. albicans-derived β-1,2-mannotetraose, we repeatedly isolated a 32-kDa protein which specifically binds these residues. A specific antiserum raised against the 32-kDa β-1,2-mannose-binding protein which inhibited C. albicans recognition by J774 cells was used to immunoprecipitate the 32-kDa molecule. Two major peptides were sequenced, and both had complete sequence homology to galectin-3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Except for reagents of stated origin, all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chimie, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France. The monoclonal antibody (MAb) AF1, a murine immunoglobulin M (IgM) to C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannosides (56), was kindly provided by A. Cassone, Department of Bacteriology and Medical Mycology, Istituto Superiore di Sanita, Rome, Italy (2). The anti-MMR rat polyclonal antibody was a gift from P. D. Stahl, Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo. The corresponding horseradish peroxidase and fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugates (i.e., goat anti-mouse IgM and goat anti-rat Ig) were obtained from Zymed (San Francisco, Calif.).

Yeast cells and oligomannosides.

The VW32 strain of C. albicans (serotype A) (9) and the SU1 strain of S. cerevisiae (45) were used throughout the study. Yeast cells were maintained at 4°C. Before experiments, yeast cells were cultured for 24 h at 28°C on Sabouraud dextrose agar. β-1,2-oligomannosides were purified from the cell wall of C. albicans as previously described (9). Briefly, phosphopeptidomannan was extracted by the method of Kocourek and Ballou (28). The acid-labile fraction of phosphopeptidomannan was obtained by hydrolysis in 10 mM HCl for 30 min at 100°C. After cooling and neutralization with NaOH, acid-stable phosphopeptidomannan was removed by precipitation with 70% ethanol. β-1,2-oligomannosides from the acid-labile fraction were separated by gel filtration chromatography on Bio-Gel P2 (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, England).

Cell lines and animal-derived cells.

The mouse macrophage-like cell line J774 (ECACC 85011428) is derived from a tumor of a female BALB/c mouse (41). Adherent J774 cells were cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Biowhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with glutamine (2 mM), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), penicillin (50 μg/ml), and 10% fetal calf serum.

Female BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were obtained from IFFA-CREDO (L'Arbresle, France). Peritoneal exudate cells were elicited by injecting two or three mice intraperitoneally with 1 ml of sterile 10% proteose peptone broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) 72 h before the assay. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the peritoneal exudate cells were recovered by rinsing of the peritoneal cavity with 5 ml of DMEM. The cells were washed twice in DMEM containing 5% FCS and allowed to adhere at 37°C in culture medium in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 24 h, the nonadherent cells were washed out and macrophages were cultured for a further 24 h to allow maturation.

Biotinylation and extraction of the J774 cells.

Protein extracts from adherent J774 cells were made from either biotinylated or unlabeled cells. For surface biotinylation, plated cells were washed with 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) (PBS) containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (buffer A). Then, 100 μg of succinimidyl-6-(biotinamido)hexanoate in 1 ml of buffer A was added. After an incubation of 30 min at 20°C, the cells were washed in buffer A. Biotinylated or unlabeled J774 cells were gently scraped with a rubber policeman and pelleted at 300 × g for 10 min at 20°C. A total of 1.5 × 107 cells were extracted for 20 min in ice with 1 ml of PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 μM aprotinin, 1 mM leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples containing the extracted material were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g in a microcentrifuge to remove insoluble material.

In some experiments, membrane-enriched fractions from J774 cells were obtained by a differential centrifugation procedure. J774 cells were subjected to four freeze-thaw cycles in water containing the protease inhibitors mentioned above. The cells were centrifuged for 30 min at 15,000 × g, the resulting supernatants were centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 × g, and pellets containing the cell membranes were extracted using 0.5% Triton X-100. Membrane protein extracts were then clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g.

Neoglycoprotein.

Biotinylated neoglycoprotein was used either for fluorescence examination of β-1,2-oligomannoside binding to J774 membranes or as a probe to detect J774 proteins reacting with β-1,2-oligomannosides by ligand blotting. Unlabeled neoglycoprotein was used in affinity purification experiments. Both bovine serum albumin (BSA) and biotinylated BSA (biot-BSA) (1 μmol) (Sigma) were incubated for 7 days at 37°C with 300 μmol of C. albicans-derived β-1,2-mannotetraose in 2.5 ml of PBS containing 1.59 mmol of NaBH3CN and 1 drop of toluene (19). The neoglycoproteins were then purified from unbound sugars by gel filtration chromatography. Under these conditions, the sugar-to-protein ratio was 6:1 (mole/mole). The presence of β-1,2-oligomannosides within the neoglycoproteins was examined by blotting with the anti-β-1,2-oligomannoside MAb AF1.

Fluorescence analysis.

J774 cells (105 cells per well) were cultured at 37°C in eight-well Lab-Tek tissue culture chambers (Nunc, Naperville, Ill.). After an 18-h incubation, 150 μl of biotinylated neoglycoprotein in DMEM (25 μM sugar) was added for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were then washed and fixed with 2% Formol. Bound neoglycoprotein was revealed with 200 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed) (1:500 dilution in PBS) and mounted for microscopy examination.

Affinity purification.

Affinity chromatography experiments were performed using either live yeast cells or unlabeled neoglycoprotein coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose beads. For this purpose, 5 to 10 mg of β-1,2-oligomannoside conjugated to BSA (β-1,2-Man–BSA) in 3 ml of coupling buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate [pH 8.3], 0.5 M NaCl) was incubated for 2 h at 20°C with 1 ml of CNBr-activated Sepharose beads. The beads were then centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min and blocked with 10 ml of 1 M ethanolamine (pH 4)–0.5 M NaCl. β-1,2-Man–BSA-coupled beads were then equilibrated in PBS.

Extracted biotinylated proteins (800 μg in 3 ml of PBS) were incubated with 6.5 × 108 C. albicans or S. cerevisiae yeast cells or with β-1,2-Man–BSA-coupled beads for 1 h at 4°C. After several washes in PBS to remove unbound material, the bound proteins were desorbed by boiling at 100°C for 5 min with 40 μl of Laemmli sample buffer without β-mercaptoethanol and clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 8 min.

Western blotting.

J774 proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide) before being blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL [Amersham, Little Chalfont, England]) for 1 h at 400 mA in a semidry transfer system. After being stained with 0.1% Ponceau S in 5% acetic acid to confirm even loading and transfer, the membrane was blocked by incubation for 1 h at 20°C with TNT (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween) containing 5% milk. For experiments involving affinity-purified biotinylated J774 surface proteins, purified proteins were detected by probing the blot with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1:1,000 dilution) in TNT containing 0.5% BSA (TNT-BSA). In experiments based on direct detection of proteins reacting with β-1,2-oligomannosides, the membranes were probed with biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin. In experiments involving antibody detection, blotted J774 proteins were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of immune sera for 1 h at 37°C in TNT. After being washed, the membranes were probed with the corresponding alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antisera (1:2,000 dilution) in TNT.

Preparation of the anti-32-kDa membrane protein rat serum.

Fisher rats were immunized with 200 μl of PBS containing 20 μg of 26- to 35-kDa J774 proteins electroeluted from electrophoretically separated protein extracts together with 200 μl of complete Freund adjuvant. The animals were boosted every 15 days for 2 months with the same antigens but in 200 μl of incomplete Freund adjuvant. Throughout the entire period, the immune response induced in the sera was monitored by Western blotting onto J774 protein extracts.

Inhibitory effect of anti-32-kDa antibody.

The inhibitory activity of the day 60 rat immune serum was tested on binding of C. albicans blastoconidia to J774 cells (105 cells per well) were cultured at 37°C in eight-well Lab-Tek tissue culture chambers. After 18 h, a 1:100 dilution in DMEM of either preimmune or immune anti-32-kDa polyclonal antibody was added to the culture for 30 min. C. albicans yeast cells were then added for 10 min at a yeast-to-cell ratio of 50:1. The slides were then washed, fixed with 2% Formol, and mounted for microscopy examination.

Sequence homology.

The 32-kDa β-1,2-mannose-binding protein was purified from J774 cell membrane extract (2 mg of proteins) by immunoprecipitation using 400 μl of rat immune serum and protein G-coupled beads. Precipitated material was eluted with 40 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide), and tested for β-1,2-oligomannoside reactivity by ligand blotting using biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA as described above. After staining with amido black (0.003% [wt/vol] in 45% methanol–10% acetic acid–45% water), the corresponding band was cut out and air dried in a vacuum centrifuge before being subjected to tryptic digestion (1 μg of trypsin/ml). The resulting peptides were separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) through a DEAE-C18 column with acetonitrile–0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Two different peptides were sequenced, and homologies to existing proteins were examined in the Swiss Prot database using the BLAST Program (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

RESULTS

C. albicans but not S. cerevisiae binds to a 32-kDa J774 cell protein.

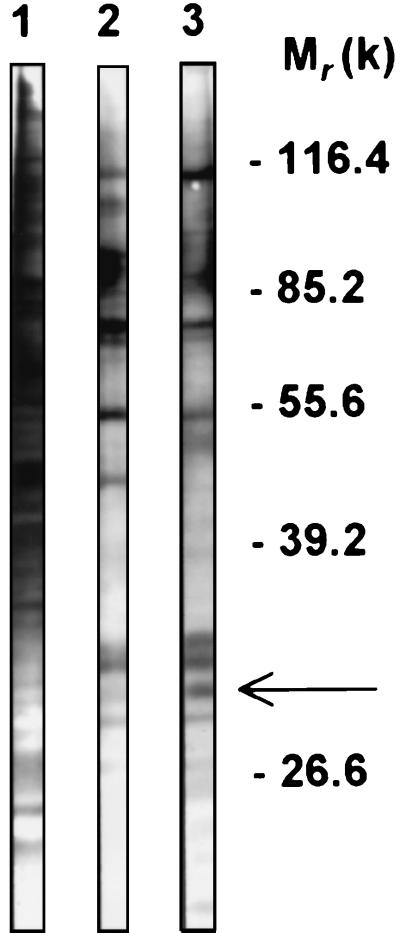

After surface biotinylation of the J774 cells, the labeled proteins were extracted with Triton X-100 and incubated with either S. cerevisiae or C. albicans blastoconidia to examine differential binding on these two yeast species. Elution of bound proteins and disclosure by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin showed a large array of macrophage proteins from 50 to 100 kDa that bound to both yeast species (Fig. 1). Beside these molecules, a large amount of material in the 30- to 35-kDa range was predominantly bound to C. albicans yeast cells (Fig. 1, compare lane 2 and 3). In this material, a 32-kDa protein was repeatedly identified. The presence of this protein at the cell membrane was confirmed when Triton X-100 extracts from membrane-enriched fractions of biotinylated J774 cells were used in the same type of experiments (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Binding analysis of J774 surface membrane proteins to yeast cells. Plasma membrane proteins from J774 cells were biotinylated and extracted using Triton X-100. Soluble extracts were incubated with either S. cerevisiae (lane 2) or C. albicans (lane 3) blastoconidia. After the samples were washed, the bound proteins were eluted, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to blotting with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin. Lane 1 contains total extract from biotinylated cells. The arrow indicates the major protein differing between the two yeast-associated proteins. Molecular weights (in thousands) are shown on the right.

C. albicans mannan-derived β-1,2-oligomannosides conjugated to BSA bind to the 32-kDa protein.

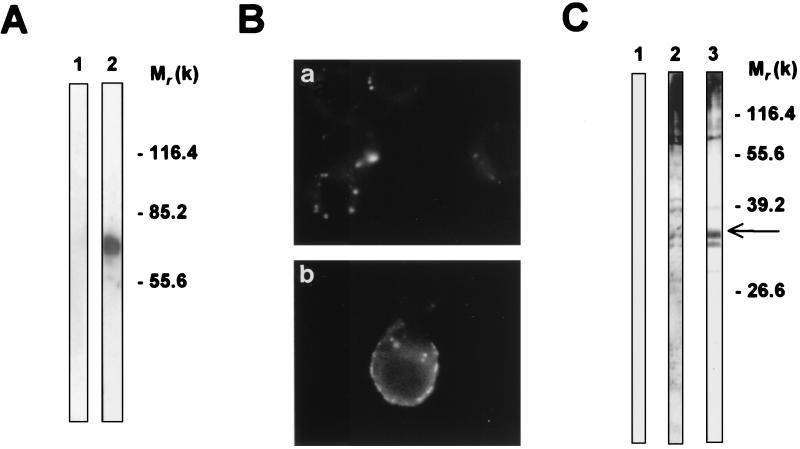

Since a major difference in surface molecules between C. albicans and S. cerevisiae lies in the presence of β-1,2-linked oligomannose residues in the former yeast species, we examined the role of these residues through the construction of a neoglycoprotein. We conjugated a β-1,2-linked mannotetraose derived from C. albicans mannan to BSA (β-1,2-Man–BSA). Figure 2A shows the coupling efficiency as evidenced by the positivity of Western blotting with MAb AF1 specific for β-1,2-oligomannoside epitopes of β-1,2-Man–BSA (lane 2) compared to that obtained with BSA alone (lane 1). Identical results were obtained after conjugation of the mannotetraose to biot-BSA (data not shown). Using equal amounts of biotinylated proteins either conjugated or not conjugated, fluorescence experiments performed on J774 cells showed that compared to biot-BSA, which accumulated at low levels within cell vesicles, biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA was associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 2B). Forty percent of cells exhibited strong biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA staining at the plasma membrane.

FIG. 2.

Identification and localization of the 32-kDa macrophage protein recognized by β-1,2-Man–BSA. (A) After conjugation, the presence of β-1,2-oligomannosidic epitopes on biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA was examined using Western blotting with anti-β-1,2-oligomannoside MAb AF1 (lane 2). Lane 1 shows the reactivity of MAb AF1 with uncoupled BSA. (B) J774 cells were incubated with biot-BSA (a) or biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA (b). Bound protein was revealed with fluorescein-conjugated streptavidin. (C) Extracts from J774 cells were subjected to blotting with biot-BSA (lane 1), biot-α-Man–BSA (lane 2), or biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA (lane 3) and revealed with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. The arrow indicates the position of the 32-kDa protein. These experiments were performed three to five times with identical results. Molecular weights (in thousands) are given on the right of panels A and C.

We then examined the nature of the J774 membrane molecule binding biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA. Extracts from J774 cells were subjected to blotting with different biotinylated BSA probes: uncoupled biot-BSA, biot-BSA coupled to α-methyl mannopyrannoside (biot-α-Man–BSA) and biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA. biot-BSA did not bind to macrophage extracts (Fig. 2C, lane 1). Both biot-α-Man–BSA and biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA bound to macrophage components of >55 kDa, including poorly defined polydispersed material and a single band around 80 kDa (lanes 2 and 3). Beside these bands, biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA bound selectively to a doublet with a molecular mass of 31 to 32 kDa (lane 3).

The 32-kDa protein recognized by C. albicans and not by S. cerevisiae binds to β-1,2-oligomannosides in a calcium-independent way.

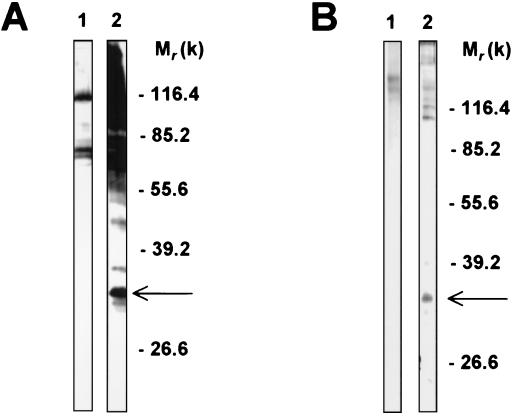

Identity between the 32-kDa macrophage membrane protein that bound to C. albicans yeast cells and the protein that bound to the β-1,2-oligomannosides, as evidenced through biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA binding to J774 extracts, was confirmed by experiments based on affinity purification. Macrophage proteins were either incubated with C. albicans blastoconidia (Fig. 3A) or passed through a column consisting of β-1,2-Man–BSA-coupled Sepharose (Fig. 3B). After being transferred to nitrocellulose, the eluted materials were detected either with biot-BSA or with biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA. After passage through C. albicans yeasts (Fig. 3A), biot-BSA revealed mainly two large bands with masses of 80 and 120 kDa. Coupling to β-1,2-mannotetraose resulted in recognition by the neoglycoprotein of several other proteins eluted from C. albicans. Among them, three proteins with masses of 31 to 32, 37, and 45 kDa could be clearly identified. Blotting of material eluted from β-1,2-Man–BSA-coupled Sepharose with biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA revealed mainly two groups of molecules, one with a mass of >90 kDa and a well-defined 32-kDa protein. In both experiments, supplementation with divalent cations during either affinity binding or blotting had no effect on the results.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of macrophage proteins recognized by β-1,2-Man–BSA and C. albicans blastoconidia. J774 extracts were incubated with C. albicans yeast cells (A) or with Sepharose beads coupled with β-1,2-Man–BSA (B). Bound material was eluted, electrophoresed, and blotted with biot-BSA (lanes 1) or biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA (lane 2). The arrows indicate the position of the 32-kDa protein. Experiments were repeated at least five times with identical results. Molecular weights (in thousands) are given on the right of the panels.

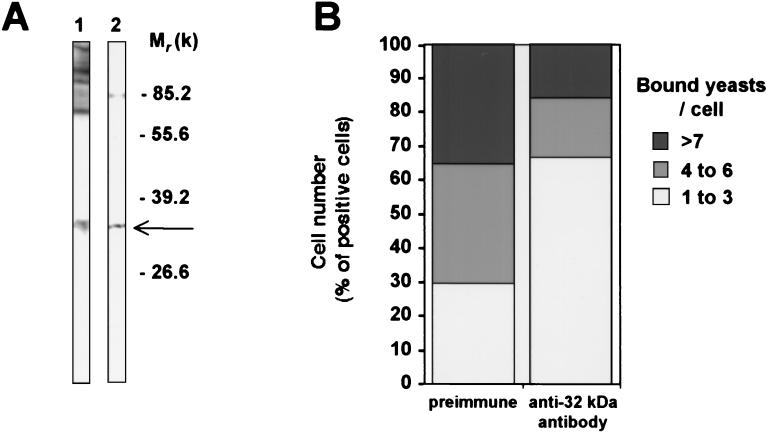

An antiserum raised against the 32-kDa protein inhibits C. albicans binding to J774 cells.

Since the 32-kDa protein was one of the main molecules which appeared to be recognized both by C. albicans and by β-1,2-oligomannosides but not by S. cerevisiae or by uncoupled BSA, we hypothesized that this molecule could be involved in the recognition of β-1,2-oligomannosides by the J774 cells. To characterize the J774 32-kDa protein, we prepared a rat antiserum by immunization with this molecule electroeluted from preparative polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. We first examined the antigenic specificity of this antiserum. For this purpose, material eluted from C. albicans was blotted either with biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA, used as positive control (Fig. 4A, lane 1), or with the anti-32-kDa antiserum (lane 2). The antiserum selectively stained a 32-kDa band, which comigrated with the 32-kDa protein, revealed by the neoglycoprotein. We then examined whether the anti-32-kDa antiserum displayed inhibitory activity toward binding of C. albicans to the J774 cells. J774 cells were incubated in the presence of preimmune serum or anti-32-kDa antiserum and then cocultivated with C. albicans blastoconidia (13). When the number of cells that bound more than three yeasts was determined, the presence of the anti-32-kDa antiserum led to a decreased number of positive cells (5% ± 5% inhibition with the preimmune serum compared to 37% ± 3% inhibition with the anti-32-kDa antiserum). However, the antiserum inhibited only part of the interaction of the yeast with the cells, suggesting that not all lectin systems involved in the recognition of C. albicans by the J774 cells were altered by the anti-32-kDa antiserum (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Specificity of the anti-32-kDa polyclonal antibody that inhibits C. albicans binding to J774 cells. (A) J774 proteins eluted from C. albicans blastoconidia were revealed either with biot-β-1,2-Man–BSA (lane 1) or with the rat polyclonal antibody raised against the 32-kDa protein (lane 2). (B) J774 cells (105 cells per well) were cultured at 37°C in eight-well Lab-Tek tissue culture chambers in the presence of a 1:100 dilution of either preimmune or immune anti-32 kDa polyclonal antibody. C. albicans yeast cells were then added at a yeast-to-cell ratio of 50:1. The slides were washed, fixed, and mounted for microscopy examination. Data are expressed as the number of J774 cells in relation to the number of yeasts ingested by cell. Experiments were repeated at least five times with similar results. Molecular weights (in thousands) are given on the right of panel A.

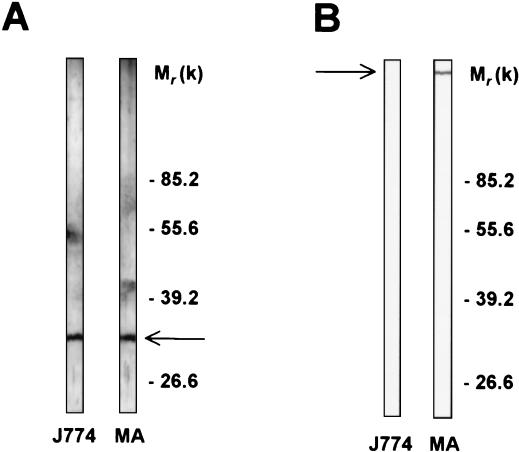

The 32-kDa protein is expressed by mouse peritoneal macrophages and is different from the MMR.

To verify that the 32-kDa protein was present at the membrane of primary cells, the anti-32-kDa antiserum was allowed to react on blots of protein extracts prepared from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Staining of a 32-kDa molecule, which comigrated with the 32-kDa protein observed with the J774 cells, demonstrated the presence of the same antigen on primary macrophages (Fig. 5A). To explore possible cross-immunological identities between the 32-kDa molecule and the MMR, blotted membrane extracts from either mouse peritoneal macrophages or J774 cells were stained with an anti-MMR polyclonal antibody (Fig. 5B). As expected, the MMR was recognized in macrophage extracts but was absent in J774 extracts (Fig. 5B, lane MA). In none of the cell extracts was a 32-kDa molecule stained by the anti-MMR polyclonal antibody, demonstrating the absence of cross-reactivity between the two macrophage membrane mannose-binding proteins.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of antigenicity of the 32-kDa protein and the MMR. Extracts of mouse peritoneal macrophages (MA) or from J774 cells (J774) were blotted with either anti-32-kDa (A) or anti-MMR (B) polyclonal antibodies and revealed with specific antiserum conjugated to peroxidase. Experiments were repeated at least three times with identical results.

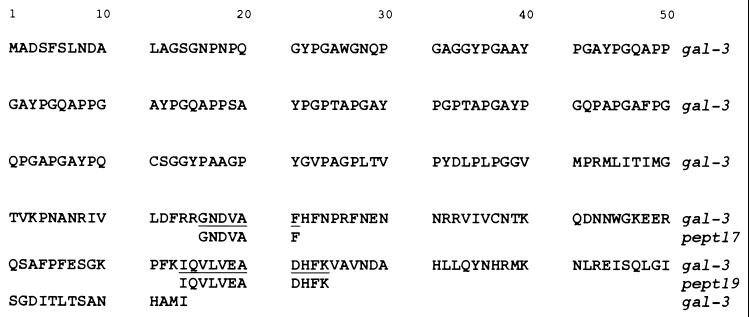

Peptides from the J774 32-kDa protein have sequence homology to galectin-3.

The 32-kDa protein was immunoprecipitated from J774 protein extracts with the anti-32-kDa serum, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to trypsin digestion. Peptides were separated by HPLC. Of these, two major peptides (Pept17 and Pept19) were sequenced and the sequences were subjected to homology analysis with the Swiss-Prot database. Both peptides were 100% homologous to sequences localized in different portions (positions 166 to 171 and 214 to 224) of galectin-3 (Fig. 6), previously designated macrophage cell surface antigen Mac-2.

FIG. 6.

Sequence homologies between two peptides of the 32-kDa protein and galectin-3. The J774 cell 32-kDa protein was immunoprecipitated with the anti-32-kDa antiserum, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to trypsin digestion as described in Materials and Methods. Peptides were separated by HPLC. Homologies of two peptides (pept17 and pept19) to known proteins were examined with the Swiss-Prot database.

DISCUSSION

The recognition of systemic candidiasis as a major medical problem in hospital patients (40) has generated unprecedented scientific interest in the understanding of its pathophysiology. Basic microbiological studies have addressed signal transduction pathways (4) and gene regulation mechanisms controlling C. albicans characteristics considered essential for virulence, i.e., filamentation (29), adhesion (14), enzyme secretion (7, 17), and phenotypic switching (38). Immunological studies have begun to unravel the complex immunoregulatory circuits by which the immune system directs the predominance of the CD4+ Th1 or Th2 subset (36). However, very little is known yet about which C. albicans molecules, among those encoded by more than 6,000 genes, play a major role in eliciting reactions that protect the host or the microbe.

As a yeast, a characteristic of C. albicans is to devote an important part of its metabolism to the synthesis of sugars. Among these, mannose residues may represent up to 40% of the cell wall. They are expressed mainly at the cell surface, associated with mannoprotein by either O- or N-glycosylation (16). The archetype of such molecules is the cell wall phosphopeptidomannan (or mannan), the immunological properties of which have been extensively studied in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae. Over the last few years, interest has focused on β-1,2-linked oligomannosides, first described in 1985 by Shibata et al. as being associated with the C. albicans cell wall mannan by phosphodiester bridges (46). It has been shown that an IgM MAb against a β-1,2-linked mannotriose, MAb B6.1, and not an IgM specific for the mannan acid-stable fraction, MAb B6, protects mice in a model of systemic candidiasis (21). In an in vitro assay, MAb B6.1, but not MAb B6, was found to enhance the candidacidal activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the presence of fresh mouse serum, suggesting the involvement of mouse complement in the killing (20).

Both α- and β-methylmannosides are recognized by CR3 (58). In the present study, we demonstrated that β-1,2-oligomannosides derived from C. albicans mannan specifically bound to a 32-kDa protein expressed both on the J774 cell line and on peritoneal murine macrophages. This finding emerged from our (13, 24, 25, 27) and other (30, 31) previous experiments demonstrating a specific interaction of C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannosides with macrophage membrane. The identification of the 32-kDa protein as a β-1,2-mannose-binding protein was based on immunochemical and affinity approaches. These methods were applied to J774 cell membrane proteins and either yeast cells (C. albicans or S. cerevisiae) or β-1,2-Man–BSA. When using an anti-MMR antiserum (49), we found no cross-reactivity with this receptor specific for α-linked mannose residues. This was important for determining that the β-1,2-mannose-binding protein was not an MMR breakdown product, since it has been shown that the MMR was synthesized by J774 cells and rapidly degraded (12). With an antiserum raised against the 32-kDa β-1,2-mannose-binding protein, we found that the 32-kDa protein was also present on mouse macrophage membranes. Binding of C. albicans yeast cells to macrophages was altered by this antiserum, although incompletely. These results are not surprising, since we have already shown that β-1,2-oligomannosides account for only 40% of the C. albicans binding activities to macrophage (13).

Several other proteins with molecular weights similar to those of the α and β chains of CR3 (58) were copurified when S. cerevisiae and C. albicans yeast cells were used. However, these high-molecular-weight proteins were not apparent when neoglycoproteins were used for affinity purification. Conversely, the 32-kDa molecule was never found in experiments in which material devoid of β-1,2-oligomannosides, such as S. cerevisiae yeasts or mannan, or the control neoglycoproteins (BSA or α-Man–BSA) was used, showing the specificity of the recognition.

The identity of the 32-kDa β-mannose-binding protein we isolated to galectin-3 was based on the sequence analysis of two peptides from tryptic digests of the immunoprecipitated protein. Both peptides showed total homologies to peptide sequences localized in distant portions (positions 166 to 171 and 214 to 224) of galectin-3. The identification of the molecule capable of binding β-1,2-oligomannosides as galectin-3 was somewhat surprising, since the definition of the family of galectins is based on the presence of similar carbohydrate recognition domains and affinity for β-galactosides (22), although some galectins, such as galectin-10, recognize mannose with high affinity (52). All of the blotting experiments described here were performed after saturation of nitrocellulose with nonfat milk. Since binding of β-1,2-oligomannosides to the protein could be evidenced under these conditions (in the presence of lactose), this suggested that the lectin has higher affinity for β-1,2-oligomannosides than for β-galactosidase contained in the lactose. An elegant X-ray crystal structure of the galectin-3 carbohydrate recognition domain in complex with lactose and N-acetyllactosamine has furnished an explanation of the differences in specificity between galectin-3 and other members of the galectin family (44). Such fine-interaction studies may be required to determine which parts of the β-1,2-oligomannosides are buried by the protein and their influence on the protein structural arrangement. The striking relationship found between the number of β-1,2-linked mannopyranose residues and the ability to induce TNF-α synthesis by macrophages (27) could represent a good model to study structure-activity relationships for binding and signaling properties. A current basic scientific interest in galectin-3 has shown its subcellular distribution within the nucleus and the cytoplasm, its secretion through a nonclassical pathway (33), its association with the cell surface, and the presence of galectin-3 in intercellular matrices (39). Therefore, much remains to be discovered before the pleiotropic activities of galectin-3 can be explained. The topics that await clarification range from tumor transformation and metastasis, inflammation, nerve injury, immune cell stimulation, and pathogen interaction (1).

Galectin-3 associates with several membrane proteins different from its putative receptor (42). These molecules, expressed on polynuclear and mononuclear phagocytes and epithelial cells, are involved in the binding and phagocytosis of different microbes. Such molecules are represented by the lysosome-associated membrane glycoproteins 1 and 2 (CD107) (11, 23), CD66-a and CD66-b (11), which bind both galectin-3 and bacterial type 1 fimbriae (50), as well as CD98 and CD11b/CD18 (8). Interaction of microorganisms with multimolecular membrane complexes allows colonization and stimulates signaling cascades, which promote intracellular accommodation of the pathogen and/or induction of cytokine release, priming the immune response (35). Interaction of C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannosides and galectin-3 may participate, along with other membrane proteins, in forming macromolecular edifices responsible for stimulating properties. TNF-α synthesis induced by β-1,2-oligomannosides is dependent on a signal involving tyrosine phosphorylation similar to those observed following CR3- or CD66-related stimulations (25). The bacterial lipopolysaccharide LPS, which interacts with both its specific receptor CD14 receptor (59) and galectin-3 (34), initiates a similar signal. Interestingly, we have shown that interaction of live C. albicans cells and macrophages mediated by β-1,2-oligomannosides also involves a glycolipid, the phospholipomannan, which is shed by the yeasts during contact (25).

This series of studies therefore demonstrates that among C. albicans and host molecules triggering a macrophage response by β-1,2-oligomannosides are the phospholipomannan and galectin-3. Galectin-3 is abundantly expressed on polarized epithelial cells and neutrophils. Both cell types are essential for colonization by C. albicans and limitation of C. albicans infection, respectively. An investigation of the participation of galectin-3 in these basic pathophysiological processes is under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been supported in part by a grant from Sidaction.

We thank G. Cole for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge P. D. Stahl and A. Cassone for the gift of specific antibodies and F. van den Brûle, D. Soll, and A. Casadevall for their help in the redaction of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barondes S H, Cooper D N, Gitt M A, Leffler H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20807–20810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassone A, Torosantucci A, Boccanera M, Pelligrini G, Palma C, Malavasi F. Production and characterization of a monoclonal antibody to a cell-surface, glucomannoprotein constituent of Candida albicans and other pathogenic Candida species. J Med Microbiol. 1988;27:233–238. doi: 10.1099/00222615-27-4-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro M, Ralston N V, Morgenthaler T I, Rohrbach M S, Limper A H. Candida albicans stimulates arachidonic acid liberation from alveolar macrophages through alpha-mannan and beta-glucan cell wall components. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3138-3145.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csank C, Schroppel K, Leberer E, Harcus D, Mohamed O, Meloche S, Thomas D Y, Whiteway M. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2713–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2713-2721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czop J K, Austen K F. A beta-glucan inhibitable receptor on human monocytes: its identity with the phagocytic receptor for particulate activators of the alternative complement pathway. J Immunol. 1985;134:2588–2593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czop J K, Kay J. Isolation and characterization of β-glucan receptors on human mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1511–1520. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Bernardis F, Arancia S, Morelli L, Hube B, Sanglard D, Schafer W, Cassone A. Evidence that members of the secretory aspartyl proteinase gene family, in particular SAP2, are virulence factors for Candida vaginitis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:201–208. doi: 10.1086/314546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong S, Hughes R C. Macrophage surface glycoproteins binding to galectin-3 (Mac-2-antigen) Glycoconj J. 1997;14:267–274. doi: 10.1023/a:1018554124545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faille C, Wieruszeski J M, Michalski J C, Poulain D, Strecker G. Complete 1H- and 13C-resonance assignments for d-mannooligosaccharides of the beta-d-(1→2)-linked series released from the phosphopeptidomannan of Candida albicans VW.32 (serotype A) Carbohydr Res. 1992;236:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)85004-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felipe I, Bim S, Loyola W. Participation of mannose receptors on the surface of stimulated macrophages in the phagocytosis of glutaraldehyde-fixed Candida albicans, in vitro. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1989;22:1251–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feuk-Lagerstedt E, Jordan E, Leffler H, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Identification of CD66a and CD66b as the major galectin-3 receptor candidates in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1999;163:5592–5598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiani M L, Beitz J, Turvy D, Blum J S, Stahl P D. Regulation of mannose receptor synthesis and turnover in mouse J774 macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:85–91. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fradin C, Jouault T, Mallet A, Mallet J M, Camus D, Sinay P, Poulain D. Beta-1,2-linked oligomannosides inhibit Candida albicans binding to murine macrophage. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:81–87. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gale C A, Bendel C M, McClellan M, Hauser M, Becker J M, Berman J, Hostetter M K. Linkage of adhesion, filamentous growth, and virulence in Candida albicans to a single gene, INT1. Science. 1998;279:1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner R E, Rubanowice K, Sawyer R T, Hudson J A. Secretion of TNF-α by alveolar macrophages in response to Candida albicans mannan. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:161–168. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemmill T R, Trimble R B. Overview of N- and O-linked oligosaccharide structures found in various yeast species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1426:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghannoum M A. Extracellular phospholipases as universal virulence factor in pathogenic fungi. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;39:55–59. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.39.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giaimis J, Lombard Y, Fonteneau P, Muller C, Levy R, Makaya-Kumba M, Lazdins J, Poindron P. Both mannose and β-glucan receptors are involved in phagocytosis of unopsonized, heat-killed Saccharomyces cerevisiae by murine macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:564–571. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray G. Antibody to carbohydrate: preparation of antigens by coupling carbohydrates to proteins by reductive amination with cyanoborohydride. Methods Enzymol. 1978;50:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(78)50014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han Y, Cutler J. Assessment of a mouse model of neutropenia and the effect of an anti-candidiasis monoclonal antibody in these animals. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1169–1175. doi: 10.1086/516455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Y, Kanbe T, Cherniak R, Cutler J. Biochemical characterization of Candida albicans epitopes that can elicit protective and nonprotective antibodies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4100–4107. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4100-4107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrick K, Bawumia S, Barboni E A, Mehul B, Hughes R C. Evidence for subsites in the galectins involved in sugar binding at the nonreducing end of the central galactose of oligosaccharide ligands: sequence analysis, homology modeling and mutagenesis studies of hamster galectin-3. Glycobiology. 1998;8:45–57. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inohara H, Raz A. Identification of human melanoma cellular and secreted ligands for galectin-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1366–1375. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jouault T, Bernigaud A, Lepage G, Trinel P A, Poulain D. The Candida albicans phospholipomannan induces in vitro production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha from human and murine macrophages. Immunology. 1994;83:268–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jouault T, Fradin C, Trinel P A, Bernigaud A, Poulain D. Early signal transduction induced by Candida albicans in macrophages through shedding of a glycolipid. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:792–802. doi: 10.1086/515361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jouault T, Fradin C, Trinel P A, Poulain D. Candida albicans-derived beta-1,2-linked mannooligosaccharides induce desensitization of macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:965–968. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.965-968.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jouault T, Lepage G, Bernigaud A, Trinel P A, Fradin C, Wieruszeski J M, Strecker G, Poulain D. Beta-1,2-linked oligomannosides from Candida albicans act as signals for tumor necrosis factor alpha production. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2378–2381. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2378-2381.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocourek J, Ballou C E. Method for fingerprinting yeast cell wall mannans. J Bacteriol. 1969;100:1175–1180. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.3.1175-1181.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leberer E, Ziegelbauer K, Schmidt A, Harcus D, Dignard D, Ash J, Johnson L, Thomas D Y. Virulence and hyphal formation of Candida albicans require the Ste20p-like protein kinase CaCla4p. Curr Biol. 1997;7:539–546. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li R, Cutler J. A cell surface/plasma membrane antigen of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:455–464. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-3-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li R, Cutler J. Chemical definition of an epitope/adhesin molecule on Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18293–18299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marodi L, Kaposzta R, Campbell D E, Polin R A, Csongor J, Johnston R B., Jr Candidacidal mechanisms in the human neonate. Impaired IFN-gamma activation of macrophages in newborn infants. J Immunol. 1994;153:5643–5649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehul B, Hughes R C. Plasma membrane targeting, vesicular budding and release of galectin 3 from the cytoplasm of mammalian cells during secretion. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1169–1178. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.10.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mey A, Leffler H, Hmama Z, Normier G, Revillard J P. The animal lectin galectin-3 interacts with bacterial lipopolysaccharides via two independent sites. J Immunol. 1996;156:1572–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer T F. Pathogenic neisseriae: complexity of pathogen-host cell interplay. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:433–441. doi: 10.1086/515160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy J W, Bistoni F, Deepe G S, Blackstock R A, Buchanan K, Ashman R B, Romani L, Mencacci A, Cenci E, Fe d'Ostiani C, Del Sero G, Calich V L, Kashino S S. Type 1 and type 2 cytokines: from basic science to fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36:109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson R D, Shibata N, Podzorski R P, Herron M J. Candida Mannan: chemistry, suppression of cell-mediated immunity, and possible mechanism of action. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:1–19. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odds E C. Switch of phenotype as an escape mechanism of the intruder. Mycoses. 1997;40:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perillo N L, Marcus M E, Baum L G. Galectins: versatile modulators of cell adhesion, cell proliferation, and cell death. J Mol Med. 1998;76:402–412. doi: 10.1007/s001090050232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfaller M A, Jones R N, Messer S A, Edmond M B, Wenzel R P. National surveillance of nosocomial blood stream infection due to Candida albicans: frequency of occurrence and antifungal susceptibility in the SCOPE Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;31:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ralph P, Prichard J, Cohen M. Reticulum cell sarcoma: an effector cell in antibody-dependent cell-mediated immunity. J Immunol. 1975;114:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberg I, Cherayil B J, Isselbacher K J, Pillai S. Mac-2-binding glycoproteins. Putative ligands for a cytosolic beta-galactoside lectin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18731–18736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross G D, Cain J A, Lachmann P J. Membrane complement receptor type three (CR3) has lectin-like properties analogous to bovine conglutinin and functions as a receptor for zymosan and rabbit erythrocytes as well as a receptor for iC3b. J Immunol. 1985;134:3307–3315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seetharaman J, Kanigsberg A, Slaaby R, Leffler H, Barondes S H, Rini J M. X-ray crystal structure of the human galectin-3 carbohydrate recognition domain at 2.1-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13047–13052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sendid B, Colombel J F, Jacquinot P M, Faille C, Fruit J, Cortot A, Lucidarme D, Camus D, Poulain D. Specific antibody response to oligomannosidic epitopes in Crohn's disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:219–226. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.2.219-226.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibata N, Ishikawa T, Tojo M, Takahashi M, Ito N, Ohkudo Y, Suzuki S. Immunochemical study on the mannan of Candida albicans A-207, NIH B792, and J1012 strains prepared by fractional precipitation with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;243:338–348. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stahl P, Schlesinger P, Sigardson E, Rodman J, Lee Y. Receptor mediated pinocytosis of mannose glycoconjugates by macrophages: characterization and evidence for receptor recycling. Cell. 1980;19:207–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stahl P D. The mannose receptor and other macrophage lectins. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90123-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stahl P D, Ezekowitz R A. The mannose receptor is a pattern recognition receptor involved in host defense. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:50–55. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stocks S C, Ruchaud-Sparagano M H, Kerr M A, Grunert F, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD66: role in the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2924–2932. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki S. Immunochemical study on mannans of genus Candida structural investigation of antigenic factors 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13, 13b and 34. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1997;8:57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swaminathan G J, Leonidas D D, Savage M P, Ackerman S J, Acharya K R. Selective recognition of mannose by the human eosinophil Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (galectin-10): a crystallographic study at 1.8 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13837–13843. doi: 10.1021/bi990756e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szabo T, Kadish J, Czop J. Biochemical properties of the ligand-binding 20 kDa subunit of the β-glucan receptors on human mononuclear phagocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2145–2151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tapper H, Sundler R. Glucan receptor and zymosan-induced lysosomal enzyme secretion in macrophages. Biochem J. 1995;306:829–835. doi: 10.1042/bj3060829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thornton B P, Vetvicka V, Pitman M, Goldman R C, Ross G D. Analysis of the sugar specificity and molecular location of the beta-glucan-binding lectin site of complement receptor type 3 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1996;156:1235–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trinel P, Faille C, Jacquinot P, Cailliez J, Poulain D. Mapping of Candida albicans oligomannosidic epitopes by using monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3845–3851. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3845-3851.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xia Y, Ross G D. Generation of recombinant fragments of CD11b expressing the functional beta-glucan-binding lectin site of CR3 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1999;162:7285–7293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xia Y, Vetvicka V, Yan J, Hanikyrova M, Mayadas T, Ross G D. The beta-glucan-binding lectin site of mouse CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and its function in generating a primed state of the receptor that mediates cytotoxic activation in response to iC3b-opsonized target cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:2281–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu B, Wright S D. LPS-dependent interaction of Mac-2-binding protein with immobilized CD14. J Inflamm. 1995;45:115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]