Abstract

Objective

To determine the extent to which family physicians closed their doors altogether or for in-person visits during the pandemic, their future practice intentions, and related factors.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Six geographic areas in Toronto, Ont, aligned with Ontario Health Team regions.

Participants

Family doctors practising office-based, comprehensive family medicine.

Main outcome measures

Practice operations in January 2021, use of virtual care, and future plans.

Results

Of the 1016 (85.7%) individuals who responded to the survey, 99.7% (1001 of 1004) indicated their practices were open in January 2021, with 94.8% (928 of 979) seeing patients in person and 30.8% (264 of 856) providing in-person care to patients reporting COVID-19 symptoms. Respondents estimated spending 58.2% of clinical care time on telephone visits, 5.8% on video appointments, and 7.5% on e-mail or secure messaging. Among respondents, 17.5% (77 of 439) were planning to close their existing practices in the next 5 years. There were higher proportions of physicians who worked alone in clinics among those who did not see patients in person (27.6% no vs 12.4% yes, P<.05), among those who did not see symptomatic patients (15.6% no vs 6.5% yes, P<.001), and among those who planned to close their practices in the next 5 years (28.9% yes vs 13.9% no, P<.01).

Conclusion

Most family physicians in Toronto were open to in-person care in January 2021, but almost one-fifth were considering closing their practices in the next 5 years. Policy makers need to prepare for a growing family physician shortage and better understand factors that support recruitment and retention.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer la mesure dans laquelle les médecins de famille avaient complètement fermé leurs cliniques ou encore fermé leurs portes aux visites en personne durant la pandémie, leurs intentions quant à la pratique future et les facteurs connexes.

Type d’étude

Une enquête transversale.

Contexte

Six régions géographiques à Toronto (Ontario) qui concordaient avec les régions des équipes Santé Ontario.

Participants

Des médecins de famille pratiquant la médecine familiale complète en cabinet.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Les activités de la pratique en janvier 2021, le recours aux soins virtuels et les projets pour l’avenir.

Résultats

Parmi les 1016 (85,7 %) personnes qui ont répondu à l’enquête, 99,7 % (1001 sur 1004) ont indiqué que leur clinique était ouverte en janvier 2021; 94,8 % (928 sur 979) voyaient des patients en personne et 30,8 % (264 sur 856) dispensaient des soins en personne aux patients ayant des symptômes de la COVID-19. Les répondants estimaient avoir consacré 58,2 % de leur temps de soins cliniques aux rendez-vous téléphoniques, 5,8 % aux rendez-vous par vidéo et 7,5 % à des courriels ou une messagerie sécurisée. Parmi les répondants, 17,5 % (77 sur 439) prévoyaient fermer leur pratique au cours des 5 prochaines années. Les médecins qui travaillaient seuls en clinique représentaient des proportions plus élevées parmi les médecins qui n’avaient pas vu de patients en personne (27,6 % non c. 12,4 % oui, p<,05), parmi ceux qui n’avaient pas vu de patients symptomatiques (15,6 % non c. 6,5 % oui, p<,001) et parmi ceux qui prévoyaient fermer leur pratique au cours des 5 prochaines années (28,9 % oui c. 13,9 % non, p<,01).

Conclusion

La plupart des médecins de famille à Toronto étaient réceptifs aux soins en personne en janvier 2021, mais près du cinquième de ces médecins de famille envisageaient la fermeture de leurs pratiques au cours des 5 prochaines années. Les décideurs doivent se préparer à une pénurie grandissante de médecins de famille et mieux comprendre les facteurs favorables au recrutement et à la rétention.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed inordinate stress on primary care, the front door of our health care system. Most family physicians in Canada and the United States are self-employed individuals running independent practices and were suddenly responsible for enacting numerous changes to keep themselves, their patients, and staff safe. To see patients in person safely, family physicians needed to adopt a range of measures including personal protective equipment, improved ventilation, enhanced cleaning, passive and active symptom screening, physical distancing in the waiting room, and reducing the number of providers and patients who were in the office at any one time.1,2 To accomplish the latter, they were asked to take a virtual-first approach and assess patients by telephone, video, e-mail, or secure messaging before bringing them into the office.3 At the same time, many saw a dramatic drop in practice income owing to total reduced visits in the first few months of the pandemic when patients were told to defer nonurgent care.4,5 Family physicians were also asked to support health system responses, for example, by staffing COVID-19 assessment centres and helping in long-term care homes, overcrowded emergency departments (EDs), and hospital wards, and later on by contributing to vaccination efforts.5-7

As a result of these dramatic changes, there were concerns that the front door to our health care system was temporarily closed to some patients. Regulatory colleges have indicated they received complaints from patients of family physicians not seeing patients in person months into the pandemic,8 and some within the profession, particularly those staffing EDs, have contended the same.9 Others have raised concerns that practices were closing altogether.10-12 However, there were limited data to validate these anecdotal observations or understand the extent of these problems and the underlying reasons. In Canada, studies using administrative data have found that, 1 year into the pandemic, approximately 60% of primary care visits were conducted virtually13,14; it is unclear what proportion of these visits were conducted by telephone versus video, and there are no data on what proportions were conducted by e-mail or secure messaging. Patients seem to want virtual care to continue,15 but it is unclear whether physicians agree and what support physicians need to sustainably integrate virtual platforms into practice.

We conducted a survey of family physicians in Canada’s largest city, Toronto, Ont, to understand whether they had kept their practices open, especially to in-person visits, during the height of the second wave of COVID-19; possible reasons for practice closures; and associated physician and practice characteristics. We were also interested in family physician provision of virtual care, desired virtual care support, acceptance of new patients, and future plans for their practices.

METHODS

Setting and context

Toronto is Canada’s largest city, with a population of 2.7 million.16 In 2015 to 2016, Toronto had approximately 3500 primary care physicians, of whom 2230 were thought to be providing comprehensive family medicine care (ie, longitudinal office-based care for a panel of patients of different ages and backgrounds).17 Approximately 80% of Toronto family physicians practise under a patient enrolment model, a group of 3 or more physicians who have shared responsibility for after-hours access and receive some blended payments.18 Of those in an enrolment model, just over half are paid primarily by capitation with some incentives and fee-for-service income; the remaining are paid primarily fee-for-service with some incentives and only a small monthly capitation fee (personal communication from Peter Gozdyra, Medical Geographer, ICES; 2016). Approximately 20% of capitation practices are part of family health teams (FHTs) that receive funding for other health professionals such as social workers and pharmacists and have added accountability for services provided. Finally, less than 2% of physicians practise in a community health centre—a team-based, salaried model that traditionally serves more structurally marginalized communities. On March 14, 2020, new temporary virtual billing codes were introduced in Ontario to compensate physicians for telephone or video visits; no billing codes were introduced for e-mail or secure messaging with patients.19 Telephone and video codes were given the same fee-for-service dollar value as the analogous in-person visit billing codes and were considered in-basket within capitation models.

Study design and population

Between March and June 2021, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of family physicians practising in 6 geographic areas in Toronto recently aligned with Ontario Health Teams (Appendix 1, available from CFPlus*). Our intent was to survey all family physicians with active, comprehensive, office-based practices. Because there is no single validated database of actively practising family physicians in Ontario, we identified eligible family physicians using local knowledge and data from the regulatory college. First, family physician collaborators across these 6 geographic areas provided contact information to project staff for all family physicians who they believed were actively practising office-based, comprehensive family medicine in their areas. Second, this information was supplemented with publicly available information from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario gathered from a previous outreach initiative.20 We excluded physicians who had not practised office-based primary care in the 6 months prior to the pandemic (September 2019 to February 2020), had moved their practices outside Toronto, were on parental leave, or were no longer practising comprehensive family medicine (eg, had focused practices, had closed their practices, had retired).

The project was initiated by family physician leaders in Toronto to directly inform regional policy and planning. It was sponsored by the regional health authority, Ontario Health Toronto Region, and supported by provincial partners including the Ontario College of Family Physicians and the Ontario Medical Association. The project was reviewed by institutional authorities at Unity Health Toronto and deemed to require neither research ethics board approval nor written informed consent from participants.

Survey

Three versions of a survey were developed, 1 each for e-mail, fax, and telephone distribution (Appendix 2, available from CFPlus*). The e-mail survey was the most comprehensive and included questions on practice changes during the pandemic, practice operations in January 2021 (including whether physicians were seeing patients in person), virtual care, future plans, and demographic characteristics as well as relevant probes (eg, what factors influenced a decision not to be open to in-person visits). The fax included only a few questions from each of these areas, with limited probes. The telephone survey had the fewest questions and was designed to elicit responses from either the physician or their reception staff; it included key questions about practice changes during the pandemic, practice operations in January 2021, and demographic characteristics, with no probes. In cases where project staff were unable to speak to a physician or receptionist, they noted relevant information from the practice voice mail greeting, when it was available.

The surveys were developed with local and provincial family physician collaborators, a senior administrator at the regional health authority, and a survey methodologist. They were piloted by approximately 10 practising family physicians and revised accordingly. The e-mail survey was hosted on Qualtrics, the fax survey was paper-based, and the telephone survey was administered orally by trained project staff.

Data collection

The survey was first sent electronically to all family physicians for whom we had e-mail addresses. Physicians were each sent a unique survey link and were sent up to 3 completion reminders over a 4-week period. Physicians who did not respond to the e-mail survey, or for whom we had no e-mail addresses, were sent the fax version of the survey; faxed surveys had unique identifiers corresponding to individual physicians. We sent 1 fax reminder 1 week after the initial fax had been sent. Physicians who did not respond to the e-mail or fax surveys were then contacted by telephone by trained project staff. After obtaining verbal consent, project staff asked questions of the reception staff or were directed to speak with the physician in some cases. If there was no answer, staff left a voice mail and conducted 1 follow-up telephone call 1 week after the initial telephone outreach. In cases where staff were unable to speak to a physician or receptionist, they noted relevant information from the practice voice mail greeting, when it was available.

E-mail and fax survey introductions were signed by a local family physician collaborator. No financial incentive was provided for physicians to participate. Once data collection was complete, all personal identifiers were removed from the data set and replaced with study identification numbers; physician names corresponding to the study identification numbers were kept in a separate linking log.

Analysis

We compared survey respondents with nonrespondents using publicly available self-reported data from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario on gender and medical school graduation year. We analyzed responses to surveys where at least 1 question had been answered.

Descriptive statistics were calculated; denominators were specified based on the number of physicians responding to a question. Chi-squared tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess whether there were associations between physician or practice characteristics and whether physicians were seeing patients in person, were seeing patients with COVID-19 symptoms, or intended to close their practices in the next 5 years. A P value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant. All analyses were done in R, version 4.0.0.

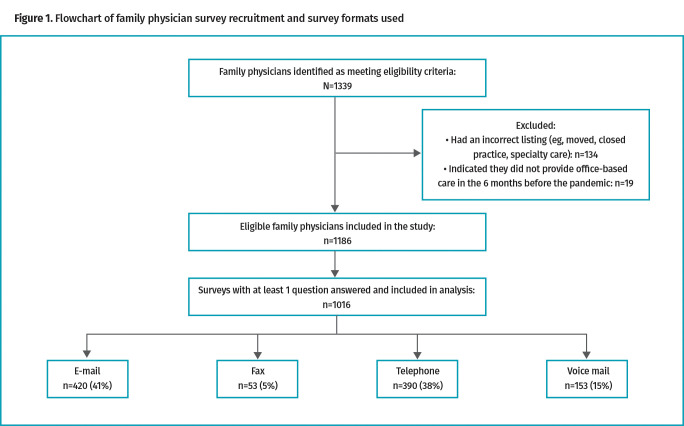

RESULTS

We identified 1339 family physicians who met eligibility criteria based on publicly available information and information from our collaborators. Of these, 134 had incorrect listings and an additional 19 responded to the survey indicating they did not provide office-based care in the 6 months before the pandemic and were thus excluded (Figure 1). We received and analyzed 1016 survey responses from the remaining 1186 eligible family physicians: 420 from e-mail, 53 from fax, 390 from telephone, and 153 from voice mail greetings (overall response rate 85.7%). Compared with nonresponders, those who responded to the survey had a more recent graduation year (mean [SD]: 1998 [14.2] vs 1994 [15.6], P<.01) and a higher proportion were female (61.5% vs 49.4%, P<.01).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of family physician survey recruitment and survey formats used

Respondents had a mean graduating year of 1998 and mean estimated practice size of 1215 patients; 61.5% were female (Table 1). Most worked in group settings, with only 12.8% reporting they were the only physician in their clinic: 46.9% worked in either FHTs or community health centres, 27.0% in a non-team capitation model, and 21.5% in either enhanced or straight fee-for-service models. Just 2.7% of practices provided only walk-in services.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of family physicians who responded to the survey (N=1016)

| CHARACTERISTIC | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Gender (n=1013),* n (%) | |

| • Female | 623 (61.5) |

| • Male | 390 (38.5) |

| Medical school graduation year (n=1013)* | |

| • Mean (SD) | 1998 (14.2) |

| • Median (IQR) | 2001 (1986-2011) |

| Medical school graduation year (categorical; n=1013), n (%) | |

| • Before 1970 | 24 (2.4) |

| • 1970-1979 | 113 (11.2) |

| • 1980-1989 | 177 (17.5) |

| • 1990-1999 | 165 (16.3) |

| • 2000-2020 | 534 (52.7) |

| Practice remuneration model (n=755), n (%) | |

| • PEM: enhanced fee-for-service† | 146 (19.3) |

| • PEM: blended capitation without team‡ | 204 (27.0) |

| • PEM: family health team | 308 (40.8) |

| • Community health centre | 46 (6.1) |

| • Traditional fee-for-service | 16 (2.1) |

| • Other | 35 (4.6) |

| Office practice setting (n=811), n (%) | |

| • Group setting (2-5 physicians in clinic) | 253 (31.2) |

| • Group setting (>5 physicians in clinic) | 429 (52.9) |

| • Only physician in clinic | 104 (12.8) |

| • Works in multiple office settings | 25 (3.1) |

| Provides walk-in services only (n=778), n (%) | |

| • Yes | 21 (2.7) |

| • No | 757 (97.3) |

| Estimated panel size (n=435) | |

| • Mean (SD) | 1215 (901) |

| • Median (IQR) | 1000 (775-1500) |

IQR—interquartile range, PEM—patient enrolment model.

Gender and year of graduation information are from publicly available data from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; other demographic variables are from respondent self-report.

Enhanced fee-for-service includes the family health group and comprehensive care models.

Blended capitation includes the family health organization and family health network models.

Whether practices were open in January 2021

Almost all respondents (99.7%; 1001 of 1004) indicated their practices were open to in-person or virtual visits in January 2021, with 94.8% (928 of 979) saying they saw patients in person. Among those not seeing patients in person, 100.0% (15 of 15) said they had arrangements for their patients to be assessed elsewhere, with 60.0% reporting this was with another physician in their office or practice group. The most important factor for the decision not to see patients in person was health concerns (93.7% or 15 of 16 reported this as a fairly or very important factor) followed by supply of personal protective equipment (26.7% or 4 of 15 reported this as a fairly or very important factor). Sixty percent (9 of 15) reported not seeing patients in person for more than 6 months. Comparing physicians who did and did not see patients in person, there were statistically significant differences in mean medical school graduation year (mean [SD]: 1990 [18.1] among those seeing patients in person vs 1999 [13.7] among those not seeing patients in person, P<.001) and office practice setting (among those seeing patients in person, 12.4% were the only physicians in their clinics vs 27.6% for those not seeing patients, P<.05).

Care of patients with COVID-19 symptoms

Close to one-third of respondents (30.8%, 264 of 856) said that in January 2021 they provided in-person care in their offices to any patients reporting symptoms consistent with COVID-19. Among those who reported not seeing any symptomatic patients in person, 59.3% (172 of 290) said they would refer symptomatic patients to local testing centres and assess them in person following negative COVID-19 test results, while 33.8% (98 of 290) said they sent all symptomatic patients to their local EDs or urgent care centres if in-person assessment was necessary. When comparing physicians who did and did not see symptomatic patients in person, there was a statistically significant difference in mean estimated panel size (mean [SD]: 921 [671] vs 1328 [969], P<.001), mean graduation year (mean [SD]: 2000 [12.7] vs 1996 [14.4], P<.001), practice remuneration model (P<.001), and office practice setting (P<.001) (Table 2). Among those who saw symptomatic patients in person, 69.5% were in FHTs and 80.0% were in group settings with more than 5 physicians compared with 27.3% and 40.8%, respectively, among those who did not see symptomatic patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of family physicians who did and did not report seeing patients with COVID-19 symptoms in their clinic in January 2021 (N=856): Cell sizes <6 have been suppressed.

| CHARACTERISTIC | SAW PATIENTS WITH COVID-19 SYMPTOMS |

DID NOT SEE PATIENTS WITH COVID-19 SYMPTOMS |

P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n=856),* n (%) | |||

| • Female | 172 (65.2) | 350 (59.1) |

.11 |

| • Male | 92 (34.8) | 242 (40.9) | |

| Medical school graduation year (n=856) | |||

| • Mean (SD) | 2000 (12.7) | 1996 (14.4) |

<.001 |

| • Median (IQR) | 2003 (1992-2011) | 1998 (1985-2010) | |

| Medical school graduation year (categorical; n=856), n (%) | |||

| • Before 1970 | <6 (<2.3) | 12 (2.0) |

<.001 |

| • 1970-1979 | 15-25 (5.7-9.5) | 81 (13.7) | |

| • 1980-1989 | 29 (11.0) | 129 (21.8) | |

| • 1990-1999 | 51 (19.3) | 92 (15.5) | |

| • 2000-2020 | 159 (60.2) | 278 (47.0) | |

| Practice remuneration model (n=712), n (%) | |||

| • PEM: enhanced fee-for-service† | 21 (8.8) | 118 (24.9) |

<.001 |

| • PEM: blended capitation without team‡ | 22 (9.2) | 169 (35.7) | |

| • PEM: family health team | 166 (69.5) | 129 (27.3) | |

| • Community health centre | 21 (8.8) | 25 (5.3) | |

| • Traditional fee-for-service | <6 (<2.5) | 10 (2.1) | |

| • Other | <6 (<2.5) | 22 (4.6) | |

| Office practice setting (n=765), n (%) | |||

| • Group setting (2-5 physicians in clinic) | 20-35 (8.2-14.3) | 214 (41.2) |

<.001 |

| • Group setting (>5 physicians in clinic) | 196 (80.0) | 212 (40.8) | |

| • Only physician in clinic | 16 (6.5) | 81 (15.6) | |

| • Works in multiple office settings | <6 (<2.4) | 13 (2.5) | |

| Provides walk-in services only (n=732), n (%) | |||

| • Yes | <6 (<2.8) | 16 (3.1) |

.52 |

| • No | 195-210 (92.0-99.1) | 504 (96.9) | |

| Estimated panel size (n=414) | |||

| • Mean (SD) | 921 (671) | 1328 (969) |

<.001 |

| • Median (IQR) | 800 (500-1100) | 1100 (850-1550) | |

IQR—interquartile range, PEM—patient enrolment model.

Gender and year of graduation information are from publicly available data from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; other demographic variables are from respondent self-report.

Enhanced fee-for-service includes the family health group and comprehensive care models.

Blended capitation includes the family health organization and family health network models.

Virtual care

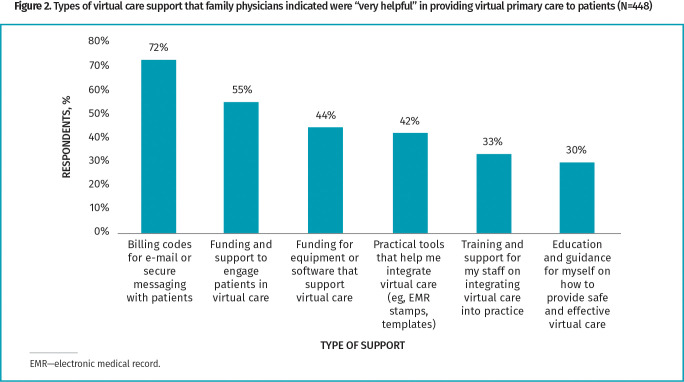

Respondents estimated spending 27.2% of clinical care time in January 2021 doing in-person visits, 58.2% doing scheduled telephone assessments, 5.8% doing scheduled video assessments, and 7.5% using secure messaging or e-mail (Table 3). However, only 14.2% (64 of 450) and 8.2% (37 of 450) reported they were fairly or very likely to offer telephone and video appointments, respectively, if virtual billing codes did not continue. In contrast, 93.6% (421 of 450) and 55.7% (250 of 449) said they were fairly or very likely to offer telephone and video appointments, respectively, if virtual billing codes continued. The most-desired additional forms of support for virtual care were billing codes for e-mail and secure messaging (72.3% [323 of 447] indicated this was very helpful) followed by funding and support to enable patients to engage in virtual care (54.7% [245 of 448] indicated this was very helpful) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Estimated time spent by family physicians doing in-person and virtual care (N=450): Responses based on the question “Think about all of the time you spent providing clinical care to patients in your office during January 2021. What portion of your time did you spend doing the following? (Please respond so that the total equals 100%).”

| INTERACTION TYPE | MEAN (SD) PROPORTION, % | MINIMUM PROPORTION OF TIME, % | MAXIMUM PROPORTION OF TIME, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-person visits* | 27.2 (20.6) | 0 | 100 |

| Scheduled telephone assessments | 58.2 (22.7) | 0 | 100 |

| Scheduled video assessments | 5.8 (11.5) | 0 | 95 |

| One-way e-mail or secure messaging platform | 2.9 (5.0) | 0 | 28 |

| Two-way e-mail or secure messaging platform | 4.6 (7.8) | 0 | 50 |

Including time spent on infection prevention and control before or after visit.

Figure 2.

Types of virtual care support that family physicians indicated were “very helpful” in providing primary care to patients (N=448)

Acceptance of new patients, practice closure, and future practice intentions

Regarding new patients, 4.9% (22 of 448) of physicians said they were actively seeking to grow their practices and 11.6% (52 of 448) said they were accepting any new patients who contacted their offices seeking care; 45.5% (204 of 448) said they only accepted family members of current patients, while 37.9% (170 of 448) were not accepting any new patients.

Six physicians reported closing their practice permanently during the pandemic, some as previously planned and some earlier than planned; 3.4% (34 of 1016) of respondents reported hiring a locum to manage their patients, while 2.4% (24 of 1016) reported temporarily closing their practices without locum coverage at some point between March 2020 and January 2021. The most commonly reported reason for temporarily hiring a locum was “needed a break” (43.5% [10 of 23] reported as very important).

At the time of the survey, 3.9% (17 of 439) of physicians were planning to close their existing practices in the next year, with an additional 13.7% (60 of 439) planning to close in the next 2 to 5 years. When comparing those who did and did not plan to close their practices in the next 5 years, there were statistically significant differences in medical school graduation year (mean [SD]: 1980 [8.8] vs 1998 [13.3], P<.001), mean estimated panel size (mean [SD]: 1361 [809] vs 1195 [927], P<.05), gender (P<.01), office practice setting (P<.01), and whether providing only walk-in services (P<.05) (Table 4). Among those who planned to close their practices, 58.4% were male, 28.9% were the only physician in their clinic, and 7.9% were providing only walk-in services compared with 38.7%, 13.9%, and 2.2%, respectively, among those not planning to close their practices.

Table 4.

Characteristics of family physicians who did and did not report they were thinking of closing their practices in the next 5 years (N=439): Cell sizes <6 have been suppressed.

| CHARACTERISTIC | THINKING OF CLOSING THEIR PRACTICE IN THE NEXT 1 TO 5 YEARS | NOT THINKING OF OR NOT SURE OF CLOSING THEIR PRACTICE IN THE NEXT 1 TO 5 YEARS | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n=439),* n (%) | |||

| • Female | 32 (41.6) | 222 (61.3) |

<.01 |

| • Male | 45 (58.4) | 140 (38.7) | |

| Medical school graduation year (n=439) | |||

| • Mean (SD) | 1980 (8.8) | 1998 (13.3) |

<.001 |

| • Median (IQR) | 1979 (1975-1985) | 1999 (1987-2009) | |

| Medical school graduation year (categorical; n=439), n (%) | |||

| • Before 1970 | <6 (<7.8) | <6 (<1.7) |

<.001 |

| • 1970-1979 | 36 (46.7) | 30-40 (8.3-11.0) | |

| • 1980-1989 | 26 (33.8) | 72 (19.9) | |

| • 1990-1999 | 6 (7.8) | 69 (19.1) | |

| • 2000-2020 | <6 (<7.8) | 180 (49.7) | |

| Practice remuneration model (n=433), n (%) | |||

| • PEM: enhanced fee-for-service† | 25 (32.9) | 76 (21.3) |

.34 |

| • PEM: blended capitation without team‡ | 28 (36.8) | 137 (38.4) | |

| • PEM: family health team | 17 (22.4) | 100 (28.0) | |

| • Community health centre | <5 (<6.6) | 12 (3.4) | |

| • Traditional fee-for-service | <5 (<6.6) | 13 (3.6) | |

| • Other | <5 (<6.6) | 19 (5.3) | |

| Office practice setting (n=436), n (%) | |||

| • Group setting (2-5 physicians in clinic) | 29 (38.2) | 130 (36.1) |

<.01 |

| • Group setting (>5 physicians in clinic) | 20-25 (26.3-32.9) | 169 (46.9) | |

| • Only physician in clinic | 22 (28.9) | 50 (13.9) | |

| • Works in multiple office settings | <6 (<7.9) | 11 (3.1) | |

| Provides walk-in services only (n=435), n (%) | |||

| • Yes | 6 (7.9) | 8 (2.2) |

<.05 |

| • No | 70 (92.1) | 351 (97.8) | |

| Estimated panel size (n=423) | |||

| • Mean (SD) | 1361 (809) | 1195 (927) |

<.05 |

| • Median (IQR) | 1200 (887-1600) | 1000 (750-1500) | |

IQR—interquartile range, PEM—patient enrolment model.

Gender and year of graduation information are from publicly available data from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; other demographic variables are from respondent self-report.

Enhanced fee-for-service includes the family health group and comprehensive care models.

Blended capitation includes the family health organization and family health network models.

DISCUSSION

Our survey of Toronto-area family physicians found that 99.7% of practices remained open and 94.8% were seeing at least some patients in person in January 2021, during the height of the second wave of COVID-19 in Ontario,21 prior to the widespread availability of vaccinations. Personal health concerns were the most common reason physicians identified for not seeing any patients in person; all physicians who reported not seeing patients in person in January 2021 had made arrangements for their patients to be seen by a colleague if needed. Less than one-third of physicians reported seeing any patients with COVID-19 symptoms in their offices. However, among the two-thirds who reported not seeing symptomatic patients in person, 59.3% said they would do so after a patient had received a negative COVID-19 test result. A higher proportion of those seeing symptomatic patients reported being part of team-based practices and working in clinics with more than 5 other physicians. Almost 1 in 5 physicians reported thinking about closing their practices in the next 5 years; a higher proportion were males who had graduated less recently and had reported being the only physicians in their clinics.

Our findings run counter to a popular narrative that family physician offices were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.22 However, our results raise concerns about a shrinking work force, with a substantial number of physicians considering closing their practices in the near future—a worrisome finding in the context of 1 in 10 Canadians already reporting not having a regular family physician.23 Our results are in keeping with other research that suggests the pandemic has caused some family physicians to stop working and potentially accelerate their retirement plans.10,24,25 Our study did not explore reasons for wanting to leave practice in the next 5 years, but possible hypotheses include health concerns, financial issues, and burnout.12,26-28

Physicians in our study reported that in January 2021 more than two-thirds of care was delivered virtually, the majority by telephone. Most physicians wanted to continue to provide scheduled, appointment-based telephone care after the pandemic, but only if virtual billing codes continued. The most-desired support for virtual care was for billing codes for e-mail or secure messaging, suggesting physicians see value in integrating these interactions into clinical care despite our finding that only 7.5% of clinical time was used on these methods. Previous studies have also found that secure messaging was popular for both patients and physicians,29 and physician remuneration was a potential facilitator for increased uptake.30 Other research has found that most patients are comfortable with virtual care and want it to continue after the pandemic.31 Fortunately, a new physician services agreement was ratified in Ontario in March 2022 that includes permanent fee codes for scheduled telephone appointments as well as funding for secure messaging pilots.32 Physicians in our study also wanted support for patients to engage in virtual care—a finding that aligns with research that has found virtual care leaves some groups of patients behind.31,33,34

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted variation in primary care infrastructure and accountability. In our study, more physicians who worked alone in clinics reported not seeing patients in person, not seeing symptomatic patients, and considering closing their practices in the next 5 years compared with physicians who worked in groups with more than 5 physicians. These findings highlight the particular challenges of traditional, fee-for-service solo practice in the pandemic and are in keeping with calls for payment and organizational reform in primary care.35-37 Team-based practices in Ontario have dedicated administrative support as well as formal accountabilities, including reporting for timely access,38 which may explain why more physicians in these models reported seeing symptomatic patients in clinic. We also hypothesize that team-based and group practices have larger waiting rooms, allowing for more patients to be seen in person safely.

Limitations

Our study has strengths and limitations. We conducted a systematic survey of all family physicians practising in 6 geographic areas in Toronto and achieved an 85.7% response rate on our core questions of whether a practice was open and seeing patients in person. However, our sample is open to nonresponse bias; it is possible that those who did not respond were more likely to have been closed or not seeing patients in person. As well, family physicians self-reported whether they were open or closed and may have been reluctant to disclose their practice closures. Physician self-report may also have been different from patient perceptions of whether a practice was open; the latter may be influenced by longer wait times during the pandemic, but our study was not designed to assess this. Despite our extensive outreach and high response rate, we had fewer respondents working in enhanced or straight fee-for-service models relative to population distribution. Neighbourhoods in Toronto were differently affected by COVID-19,39 and our survey did not explore the impact of neighbourhood context on family physician decisions. Results may also not be generalizable to other contexts. Finally, we asked respondents to reflect on practice patterns 2 to 5 months prior to the time of the survey, which may have influenced accuracy of recall. It is also worth noting that there are no Canadian data we are aware of on how specialist physician practices responded to the pandemic.

Conclusion

Our survey results indicate that most family physician practices in Canada’s largest city were open and seeing patients in person during the COVID-19 pandemic—even before widespread vaccination of health care workers and the general population. Our findings contrast with media stories of patients reporting their family physicians were not seeing patients—an important perspective that warrants further study. Our findings also highlight the challenge of operating a solo family practice during the pandemic and support calls to expand group practice opportunities and access to team-based models that include administrative support and accountability—policy directions that may also influence more medical graduates to choose family medicine as a career.36,40 Recruiting and retaining the primary care work force is particularly important given that 1 in 5 physicians in our study said they were thinking about closing their practices in the next 5 years. Understanding and addressing root causes of burnout will be important to preventing physicians from exiting practice. Finally, to integrate virtual care into routine practice after the pandemic, we need to consider appropriate financial remuneration for physicians—including for e-mail or secure messaging—as well as support for patients who struggle with virtual connectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Thank you to primary care collaborators in Toronto who co-led this effort, including Dr David Kaplan, Dr Tia Pham, Dr Art Kushner, Dr Karen Fleming, Dr David Schieck, Leanne Clarke, Dr Elizabeth Muggah, Dr Allan Grill, Dr Alan Monavvari, staff who supported the outreach, and other members of the project working group, including Dorothy Wedel and Valeria Rodriguez. Thank you to members of the MAP Survey Research Unit at St Michael’s Hospital who also supported outreach, including Alexandra Carasco, Natalie Johnson, Annika Khan, and Olivia Spandier. Thanks to Raphael Goldman-Pham, Hilarie Stein, and Jennifer Truong, who supported an earlier outreach effort that informed this work, as well as to Dr Adam Cadotte for help identifying physicians practising in Toronto, Kirsten Eldridge for administrative support, and Amy Craig-Neil for initial coordination support. This project received funding from the INSPIRE Primary Health Care Research Program, which is funded through the Health Systems Research Program of the Ontario Ministry of Health. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by the Ontario Ministry of Health is intended or should be inferred. Dr Tara Kiran is the Fidani Chair of Improvement and Innovation in Family Medicine at the University of Toronto and is supported as a Clinician Scientist by the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto and at St Michael’s Hospital.

Editor’s key points

▸ In January 2021, during the peak of the second wave of COVID-19 in Ontario, almost all family physicians (99.7%) in Toronto had their practices open and most (94.8%) were seeing at least some patients in person. This finding runs counter to media reports of widespread closures of family physician offices.

▸ The 30.8% of family physicians who reported providing in-person care to patients who had COVID-19 symptoms were more likely to be part of team-based practices and work in clinics with more than 5 other physicians. This highlights the challenges of operating solo family practices and the need to expand group practice opportunities and access to team-based models.

▸ Provision of virtual care represented a high proportion of survey respondents’ clinical time in January 2021 in the form of scheduled telephone assessments (58.2%), video assessments (5.8%), and e-mail or secure messaging (7.5%). Future willingness to provide care virtually was linked to the continuation of virtual billing codes as well as funding to enable patients to engage in virtual care.

▸ Approximately 1 in 5 family physicians surveyed were considering closing their practices in the next 5 years. Those more likely to be considering closing their practices tended to have larger panel sizes and were more likely to be in solo practices.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ En janvier 2021, durant le pic de la deuxième vague de la COVID-19 en Ontario, presque tous les médecins de famille (99,7 %) avaient gardé leur clinique ouverte, et la plupart (94,8 %) voyaient au moins certains patients en personne. Cette constatation contredit les rapports des médias sur des fermetures généralisées de cabinets de médecins de famille.

▸ Les 30,8 % des médecins de famille qui ont signalé avoir dispensé des soins en personne à des patients porteurs de symptômes de la COVID-19 faisaient plus probablement partie de pratiques en équipe et travaillaient le plus souvent dans des cliniques comptant plus de 5 autres médecins. Cette constatation met en évidence les défis que représente la pratique familiale en solo, de même que la nécessité d’élargir les possibilités de pratique en groupe et l’accès à des modèles en équipe.

▸ En janvier 2021, la prestation des soins virtuels représentait une grande proportion du temps clinique des répondants à l’enquête, sous forme d’évaluations téléphoniques sur rendez-vous (58,2 %), d’évaluations par vidéo (5,8 %) et de courriels ou messagerie sécurisée (7,5 %). La volonté de prodiguer des soins de façon virtuelle à l’avenir était liée au maintien des codes de facturation pour soins virtuels, de même qu’au financement visant à permettre aux patients de recevoir des soins virtuels.

▸ Environ 1 médecin de famille répondant sur 5 envisageait de fermer sa clinique au cours des 5 prochaines années. Ceux qui considéraient fermer probablement leur clinique avaient tendance à avoir des listes de patients plus nombreuses et à pratiquer en solo.

Footnotes

Appendices 1 and 2 are available from https://www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Contributors

Dr Tara Kiran conceived of the study and designed it together with members of the study working group and Survey Research Unit (SRU). The SRU collected the data in collaboration with regional primary care collaborators. Ri Wang, Cheryl Pedersen, and the SRU team conducted the analysis. All authors helped interpret the data. Dr Kiran drafted the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Infection prevention and control for COVID-19: interim guidance for outpatient and ambulatory care settings. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2021. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/interim-guidance-outpatient-ambulatory-care-settings.html. Accessed 2021 Nov 15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context. Interim guidance, 1 June 2020. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-essential_health_services-2020.2. Accessed 2021 Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiran T. From virtual-first to patient-directed: a new normal for primary care. CMAJ Blogs 2021. Jul 21. Available from: https://cmajblogs.com/from-virtual-first-to-patient-directed-a-new-normal-for-primary-care/. Accessed 2021 Dec 9.

- 4.Barnett ML, Mehrotra A, Landon BE.. Covid-19 and the upcoming financial crisis in health care [commentary]. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2020;1(2). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemire F, Slade S.. Reflections on family practice and the pandemic first wave. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:468 (Eng), 467 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barzin A, Wohl DA, Daaleman TP.. Development and implementation of a COVID-19 respiratory diagnostic center. Ann Fam Med 2020;18(5):464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson E, Jetty A, Petterson S, Jabbarpour Y, Westfall JM.. Primary care’s historic role in vaccination and potential role in COVID-19 immunization programs. Ann Fam Med 2021;19(4):351-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.COVID-19 FAQs for physicians. Toronto, ON: College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; 2021. Available from: https://www.cpso.on.ca/Physicians/Your-Practice/Physician-Advisory-Services/COVID-19-FAQs-for-Physicians. Accessed 2021 Aug 23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladouceur R. Family medicine is not a business [Editorial]. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:396 (Eng), 397 (Fr). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neprash HT, Chernew ME.. Physician practice interruptions in the treatment of Medicare patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2021;326(13):1325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abelson R. Doctors are calling it quits under stress of the pandemic. New York Times 2020. Nov 15. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/15/health/Covid-doctors-nurses-quitting.html. Accessed 2021 Dec 13.

- 12.Rubin R. COVID-19’s crushing effects on medical practices, some of which might not survive. JAMA 2020;324(4):321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, Frymire E, Kopp A, Kiran T.. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2021;193(6):E200-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiran T, Glazier R.. Primary care in the COVID era. Toronto, ON: MAP Centre for Urban Solutions; 2020. Available from: https://maphealth.ca/primary-care-covid-era/. Accessed 2021 Nov 15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.What Canadians think about virtual health care. Nationwide survey results - May 2020. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 2020. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/virtual-care/cma-virtual-care-public-poll-june-2020-e.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toronto population 2021. Canada Population; 2021. Available from: https://canadapopulation.org/toronto-population/. Accessed 2021 Nov 15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glazier RH, Gozdyra P, Kim M, Bai L, Kopp A, Schultz SE, et al. Geographic variation in primary care need, service use and providers in Ontario, 2015/16. Toronto, ON: ICES; 2018. Available from: https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2018/Geographic-Variation-in-Primary-Care. Accessed 2021 Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchison B, Glazier R.. Ontario’s primary care reforms have transformed the local care landscape, but a plan is needed for ongoing improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(4):695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Info bulletin. Changes to the schedule of benefits for physician services (schedule) in response to COVID-19 influenza pandemic effective March 14, 2020. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/4000/bul4745.aspx. Accessed 2021 Aug 23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiran T. Keeping the doors open: maintaining primary care access and continuity during COVID-19. Toronto, ON: MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions; 2021. Available from: https://maphealth.ca/keeping-doors-open/. Accessed 2021 Nov 15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detsky AS, Bogoch II.. COVID-19 in Canada: experience and response to waves 2 and 3. JAMA 2021;326(12):1145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beattie S. Patients frustrated, concerned as some Ontario doctors slow to return to in-person appointments. CBC News 2021. Sep 6. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/patients-frustrated-concerned-as-some-ontario-doctors-slow-to-return-to-in-person-appointments-1.6160171. Accessed 2021 Dec 9.

- 23.Health fact sheets. Primary health care providers, 2019. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2020. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2020001/article/00004-eng.htm. Accessed 2021 Aug 23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiran T, Green ME, Wu FC, Kopp A, Latifovic L, Frymire E, et al. Family physicians stopping practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. Ann Fam Med 2022;20(5):460-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Physicians Foundation 2020 survey of America’s physicians: COVID-19 impact edition. Boston, MA: Physicians Foundation; 2020. Available from: https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020-Survey-of-Americas-Physicians_Exec-Summary.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buerhaus PI, Auerbach DI, Staiger DO.. Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA 2020;323(18):1777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etz R; Larry A. Green Center Advisory Group; Primary Care Collaborative . Quick COVID-19 primary care survey, series 29 [preprint]. Richmond, VA: Larry A. Green Center; 2021. Available from: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/168418. Accessed 2021 Aug 23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couto Zuber M. Nearly 75 per cent of Ontario doctors experienced burnout during pandemic, survey finds. Canadian Press 2021. Aug 18. Available from: https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/nearly-75-per-cent-of-ontario-doctors-experienced-burnoutduring-pandemic-survey-finds-1.5552218. Accessed 2021 Dec 9.

- 29.Enhanced access to primary care: project evaluation final report. Toronto, ON: Women’s College Hospital Institute for Health Systems Solutions and Virtual Care; 2019. Available from: https://otn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/eapc-evaluation-report.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girdhari R, Krueger P, Wang R, Meaney C, Domb S, Larsen D, et al. Electronic communication between family physicians and patients. Findings from a multisite survey of academic family physicians in Ontario. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:39-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal P, Wang R, Meaney C, Walji S, Damji A, Gill N, et al. Sociodemographic differences in patient experience with primary care during COVID-19: results from a cross-sectional survey in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 2022;12(5):e056868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ontario’s doctors ratify new three-year agreement with province [news release]. Toronto, ON: Ontario Medical Association; 2022. Available from: https://www.oma.org/newsroom/news/2022/march/ontarios-doctors-ratify-new-three-year-agreement-with-province/. Accessed 2022 Oct 11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, Haynes N, Khatana SAM, Nathan AS, et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2031640. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(2):e211913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML.. Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40(2):349-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goroll AH, Greiner AC, Schoenbaum SC.. Reform of payment for primary care—from evolution to revolution. N Engl J Med 2021;384(9):788-91. Epub 2021 Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedden L, Banihosseini S, Strydom N, McCracken R.. Family physician perspectives on primary care reform priorities: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open 2021;9(2):E466-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips RL Jr, McCauley LA, Koller CF.. Implementing high-quality primary care: a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. JAMA 2021;325(24):2437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran K, Webster F, Ivers NM, Laupacis A, Dhalla IA.. Are quality improvement plans perceived to improve the quality of primary care in Ontario? Qualitative study. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:759-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Allen K, Mendleson R, Bailey A.. Toronto’s COVID-19 divide: the city’s northwest corner has been ‘failed by the system.’ Toronto Star 2020. Jun 28. Available from: https://www.toronto.com/news-story/10054217-toronto-s-covid-19-divide-the-city-s-northwest-corner-has-been-failed-by-the-system-/. Accessed 2021 Dec 9.

- 40.Mitra G, Grudniewicz A, Lavergne MR, Fernandez R, Scott I.. Alternative payment models. A path forward [Commentary]. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:805-7 (Eng), 812-7 (Fr). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.