Abstract

Purpose

To analyze refractive changes after neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) posterior capsulotomy in pseudophakic eyes.

Patients and Methods

Patients who underwent Nd:YAG capsulotomy after cataract surgery from January 2013 to April 2022 were included in this retrospective study. Sphere, cylinder, spherical equivalent (SE), axis, and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) were compared pre- and postoperatively in 683 eyes of 548 patients at one month (n = 605 eyes) and one year (n = 211 eyes). Patients with both one-month and one-year follow-ups (n = 133) were also compared. Eyes were stratified into single-piece (n = 330), three-piece (n = 30), and light adjustable lenses (LALs) (n = 16). Pre- and postoperative measurements were analyzed within each group.

Results

Cylinder was significantly decreased at one-month (difference: 0.042±0.448 D, p = 0.006) and one-year (difference: 0.101±0.455 D, p = 0.003) compared to preoperative measurements. No significant change in sphere or axis was observed at follow-up visits (p > 0.05). CDVA significantly improved at both time points (p < 0.05). No significant change in any parameters between the one-month and one-year groups was observed (p > 0.05). There was significant improvement in CDVA in the single and three-piece lens groups (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.026, respectively), with no change in the LAL group (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

There were no changes in sphere, axis, or spherical equivalent after Nd:YAG capsulotomy. However, cylindrical error and CDVA were significantly better after the procedure. Lens type did not impact refractive parameters postoperatively.

Keywords: PCO, posterior capsular opacification, cataract, light adjustable lenses, LAL

Introduction

Posterior capsular opacification (PCO), also known as secondary cataract, is one of the most common complications seen after cataract surgery.1 Studies have shown that PCO has reportedly occurred in 12%, 21%, and 25% of patients in one, three, and almost five years after cataract surgery.2

PCO can be attributed to the postoperative wound healing response resulting from controlled trauma to the eye during cataract surgery.3 McDonnell et al examined intraocular lenses (IOLs) in postmortem patients and suggested that opaque secondary membranes are formed rather than opacification of the posterior capsule itself.4 PCOs result from residual lens epithelial cells (LECs) after cataract surgery where LECs proliferate over the anterior capsule spreading to other surfaces, most importantly the posterior capsule.3 Once the cells begin covering the posterior capsule, they eventually reach the visual axis. Although a thin layer of LECs may not markedly impact the light path, significant growth of LECs may cause light scatter.3 PCO formation is multifactorial, including surgical technique, intraocular lens (IOL) material, and IOL design;5 however, the individual influence of these factors on PCO formation is difficult to distinguish clinically.5

Treatment for PCO involves YAG capsulotomy using a neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser directed beyond the implanted lens and focused on the posterior, opacified portion of the capsule.6 The laser creates an opening in the capsule, allowing light to reach the retina unimpeded, thus removing the opacity.7 This study aims to compare the differences in sphere, cylinder, spherical equivalent (SE), axis, and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) prior to and after YAG capsulotomy to determine whether patients need to be refracted after the procedure.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY, New Hyde Park, NY) Institutional Review Board (IRB number: #A20-12-547-823). The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and HIPAA regulations were followed. Informed consent was obtained from each patient for the procedures and for the use of de-identified clinical data in research.

This is a retrospective, single-center, study of consecutive patients who underwent YAG capsulotomy between January 2013 and April 2022 at a single ambulatory surgical center, EyeSurg of Utah in Draper, Utah. Patients with visually significant PCO, previous cataract surgery, and pre- and postoperative refractive values were included. Patients with ongoing intravitreal injections, eye surgery between visits, concurrent ocular infection or inflammation, and/or absence of refraction data at specified post-operative visits were excluded. Manifest refraction was performed by the surgeon or the optometrist pre- and post-operatively. Preoperative sphere, cylinder, SE, axis, and CDVA were compared to postoperative values at one month and one year. Astigmatism data was entered into the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery astigmatism double-angle plot tool established by Abulafia et al.8 Additional analysis was done to compare these parameters between the one-month and one-year groups. For patients with one-month and one-year follow-up visits, percent distribution of eyes with various cylinder ranges prior to and at one-month and one-year after YAG capsulotomy was determined.

After evaluating and comparing the overall group, eyes were stratified by intraocular lens (IOL) type, including single and three-piece lenses. Patients with three-piece lenses were further filtered to light adjustable lenses (LALs). Patients without a documented lens type were referral patients and were excluded from the lens stratification analysis but kept in the total group analysis. A cruciate pattern for YAG capsulotomy was used in all patients; therefore, no analysis of cruciate versus circular pattern was possible.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means, standard deviations (SDs), and ranges for the sphere, cylinder, SE, axis, and CDVA measurements. Normality of data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Two-tailed paired t-tests compared pre- and postoperative refractive values, SE, and CDVA for normally distributed data. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests were used for non-normally distributed data. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Surgical Methods

Patients were dilated with one drop of tropicamide 1% followed by phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% about five to ten minutes later. Once the patients’ eyes were dilated sufficiently, they were anesthetized with topical proparacaine hydrochloride 0.5%. Nd:YAG capsulotomy procedure was performed using the UltraQ machine (Ellex, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) in a cruciate pattern. After the procedure, patients were given one drop of either apraclonidine 0.5% or brimonidine 0.2%. Once their eye pressure was checked and confirmed to be within normal limits, they were placed on prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension 1% one drop four times per day for four days.

Results

A total of 683 eyes in 548 patients (mean age 69.3±9.9 years) were included in this study. There were 254 (46.4%) males and 294 (53.6%) females. Six hundred and five eyes had one-month follow-up data, while 211 eyes had one-year follow-up data. The mean time between cataract surgery and YAG capsulotomy was 47.8±43.6 months (range, 1.1 months to 22.1 years). The average amount of energy delivered to each eye was 98.2±62.4 mJ (range, 25.6 to 450.0 mJ).

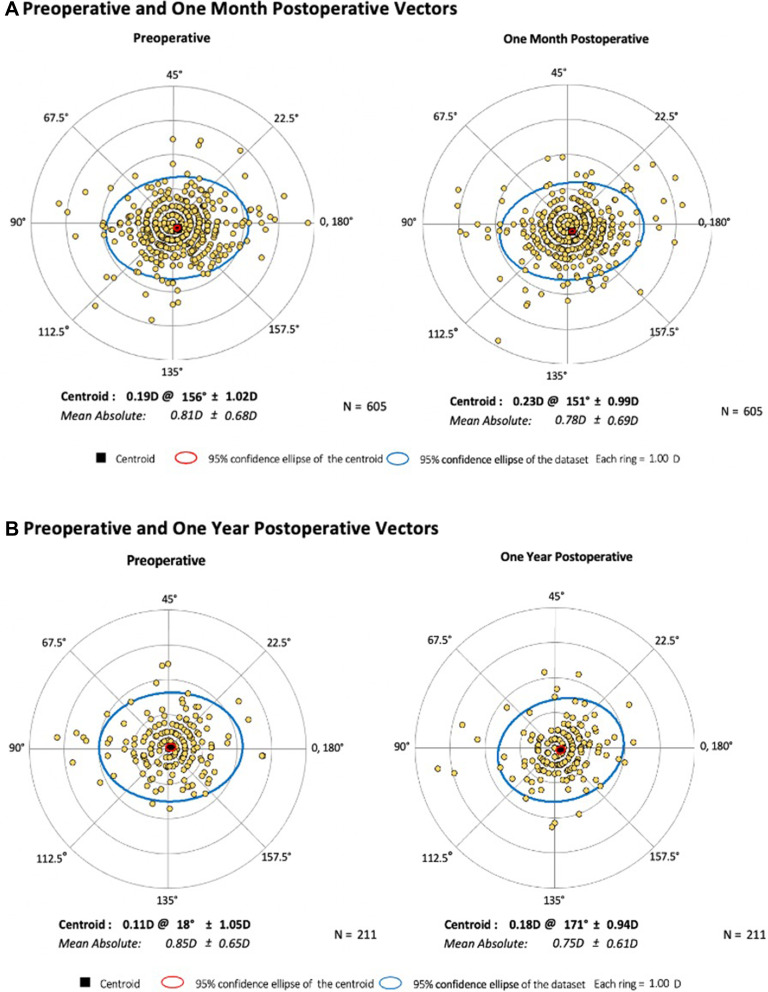

Both the one-month (difference: 0.042±0.448 D, p = 0.006) and one-year (difference: 0.101±0.455 D, p = 0.003) postoperative cylinder measurements were significantly decreased compared to preoperative values (Table 1). CDVA significantly improved at both timeframes compared to preoperative values (p < 0.0001). Changes in sphere and SE measurements were not statistically significant at either follow-up interval (p > 0.05). In the one-month group, the mean preoperative axis was 91.11±54.96°, and the mean postoperative axis was 89.04±54.62°. In the one-year group, the mean preoperative axis was 101.90±51.91°, and the mean postoperative axis was 96.73±52.19°. There was a statistically insignificant clockwise change in axis direction at both intervals (p = 0.803 and p = 0.231, respectively). Double-angle plots compared average centroid preoperatively to one month (Figure 1A) and one year (Figure 1B). When compared to the one-month mark, preoperative centroid was 0.19D at 156°±1.02D and postoperative centroid was 0.23D at 151°±0.99D. Compared to one-year postop, preoperative centroid was 0.11D at 18°±1.05 D, and postoperative centroid was 0.18D at 171°±0.94D.

Table 1.

Refractive Changes at One Month and One Year After Nd:YAG Capsulotomy

| Follow-Up Intervals | Before Capsulotomy | After Capsulotomy | Difference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (Range) | Mean ± SD (Range) | Mean ± SD (Range) | ||

| One month, n=605 | ||||

| Sphere, (D) | −0.039±1.060 (−6.50 to +5.50) | −0.068±0.975 (−4.00 to +5.25) | −0.029±0.604 (−4.75 to +4.25) | 0.050 |

| Cylinder, (D) | −0.813±0.678 (−5.00 to 0.00) | −0.771±0.688 (−5.00 to 0.00) | 0.042±0.448 (−2.25 to +2.00) | 0.006* |

| SE, (D) | −0.453±1.038 (−8.25 to +5.13) | −0.473±0.941 (−5.25 to +4.88) | −0.020±0.590 (−4.75 to +4.25) | 0.141 |

| Axis, degrees | 91.11±54.96 (1.00 to 180.00) | 89.04±54.62 (1.00 to 180.00) | −2.066±56.53‡ (−178.00 to +170.00) | 0.803 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.171±0.198 (−0.13 to +1.00) | 0.048±0.120 (−0.60 to +1.30) | −0.123±0.192 (−1.00 to +1.30) | <0.0001* |

| One year, n=211 | ||||

| Sphere, (D) | 0.011±1.083 (−4.25 to +5.50) | 0.036±1.012 (−3.00 to +6.00) | 0.025±0.570 (−2.00 to +3.00) | 0.851 |

| Cylinder, (D) | −0.851±0.647 (−3.25 to 0.00) | −0.750±0.612 (−3.50 to 0.00) | 0.101±0.455 (−1.00 to +2.00) | 0.003* |

| SE, (D) | −0.415±1.059 (−4.75 to +5.13) | −0.340±1.003 (−3.25 to +5.00) | 0.075±0.561 (−1.50 to +3.13) | 0.271 |

| Axis, degrees | 101.90±51.91 (3.00 to 180.00) | 96.73±52.19 (3.00 to 180.00) | −5.20±52.00‡ (−171.00 to +175.00) | 0.231 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.179±0.199 (0.00 to +1.301) | 0.056±0.161 (−0.13 to +1.48) | −0.122±0.196 (−0.90 to +0.88) | <0.0001* |

Notes: *Statistically significant with a p-value <0.05. ‡Positive differences refer to counterclockwise change, negative differences refer to clockwise change.

Abbreviations: CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; D, diopter; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; Nd, neodymium; YAG, yttrium-aluminum-garnet; SD, standard deviation; SE, spherical equivalent.

Figure 1.

Pre- and Postoperative Double-Angle Plots.

Abbreviation: D, diopter.

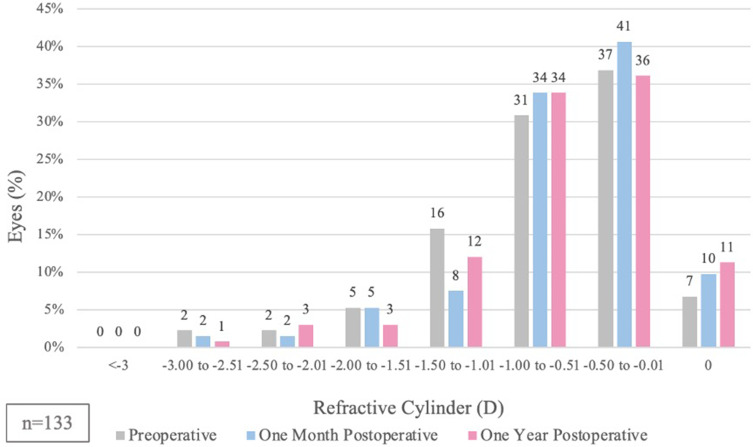

133 eyes had one-month and one-year follow-up visits (Table 2). Between the preoperative and one-month visits for these 133 eyes, the cylinder measurements and CDVA were significantly improved (p = 0.011 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Compared to the preoperative values, only the CDVA was improved at the one-year visit (p < 0.0001). Differences in sphere, cylinder, SE, axis, and CDVA values were not statistically significant between the one-month and one-year timeframes (p > 0.05). For these 133 eyes with both follow-up visits, the percent distribution of eyes within cylinder ranges was plotted for pre- and postoperative visits (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Refractive Changes in Patients with Preoperative, One Month, and One Year Measurements

| ParameterN=133 | Preop Mean ± SD (Range) | One Month Postop Mean ± SD (Range) | p-valuea | One Year Postop Mean ± SD (Range) | p-valueb | Differencec Mean ± SD (Range) | p-valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphere, D | −0.006±1.169 (−4.25 to +5.50) | 0.036±1.065 (−3.00 to +5.25) | 0.570 | 0.004±0.961 (−3.00 to +5.00) | 0.731 | −0.032±0.585 (−4.00 to +1.75) | 0.979 |

| Cylinder, D | −0.828±0.609 (−2.75 to 0.00) | −0.737±0.570 (−3.00 to 0.00) | 0.011* | −0.735±0.557 (−3.00 to 0.00) | 0.058 | 0.002±0.457 (−1.38 to +1.50) | 0.874 |

| SE, D | −0.427±1.140 (−4.75 to +5.13) | −0.361±1.051 (−3.75 to +4.88) | 0.588 | −0.364±0.970 (−3.25 to +4.63) | 0.566 | −0.003±0.674 (−4.00 to +2.25) | 0.901 |

| Axis, degrees | 99.51±49.31 (3.00 to 180.00) | 100.70±52.72 (1.00 to 180.00) | 0.375 | 95.08±51.24 (4.00 to 180.00) | 0.313 | −5.66±48.20‡ (−167.00 to +164.00) | 0.572 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.173±0.201 (0.00 to +1.00) | 0.046±0.113 (−0.12 to +0.80) | <0.0001* | 0.069±0.193 (−0.13 to +1.48) | <0.0001* | 0.023±0.145 (−0.18 to +1.30) | 0.124 |

Notes: *Statistically significant with a p-value <0.05. ‡Positive differences refer to counterclockwise change, negative differences refer to clockwise change. aComparing preoperative and one month measurements. bComparing preoperative and one year measurements. cDifferences between one month and one year postoperative values. dComparing one month and one year postoperative measurements.

Abbreviations: CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; D, diopter; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SD, standard deviation; SE, spherical equivalent.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Eyes Within Cylinder Ranges Pre- and Postoperatively.

Abbreviation: D, diopter.

Eyes were stratified based on lens type (Table 3). CDVA for single (n = 330) and three-piece lenses (n = 33) were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). Sphere, cylinder, SE, and axis measurements were not significantly different postoperatively (p > 0.05). In the LAL subgroup (n = 16), no statistically significant changes in sphere, cylinder, SE, axis, or CDVA were found.

Table 3.

Refractive Changes with Different Lens Types

| Type of Lens | Before Capsulotomy | After Capsulotomy | Difference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (Range) | Mean ± SD (Range) | Mean ± SD (Range) | ||

| Single piece, n=330 | ||||

| Sphere, D | 0.025±0.968 (−4.25 to +3.50) | 0.036±0.854 (−3.00 to +2.75) | 0.011±0.528 (−1.50 to +4.25) | 0.404 |

| Cylinder, D | −0.786±0.671 (−5.00 to 0.00) | −0.774±0.689 (−5.00 to 0.00) | 0.013±0.449 (−2.25 to +1.75) | 0.339 |

| SE, D | −0.368±0.925 (−4.75 to +2.38) | −0.352±0.825 (−3.75 to +2.25) | 0.017±0.510 (−1.63 to +4.25) | 0.543 |

| Axis, degrees | 90.97±52.10 (1.00 to 180.00) | 92.56±53.18 (1.00 to 180.00) | 1.59±51.00‡ (−178.00 to +179.00) | 0.337 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.168±0.202 (0.00 to +1.00) | 0.045±0.1094 (−0.60 to +0.60) | −0.123±0.193 (−1.00 to +0.20) | <0.0001* |

| Three piece, n=33 | ||||

| Sphere, D | −0.189±1.366 (−2.75 to +5.50) | −0.174±1.282 (−2.75 to +5.25) | 0.015±0.414 (−1.00 to +1.00) | 0.859 |

| Cylinder, D | −0.750±0.590 (−2.25 to 0.00) | −0.659±0.655 (−2.25 to 0.00) | 0.091±0.318 (−0.50 to +0.75) | 0.106 |

| SE, D | −0.564±1.363 (−3.38 to +5.13) | −0.504±1.297 (−3.13 to +4.88) | 0.061±0.419 (−0.75 to +1.00) | 0.400 |

| Axis, degrees | 81.85±59.84 (3.00 to 180.00) | 94.39±63.98 (2.00 to 180.00) | 12.55±69.13‡ (−178.00 to +170.00) | 0.324 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.112±0.181 (−0.13 to +0.80) | 0.049±0.154 (−0.13 to +0.80) | −0.062±0.141 (−0.48 to +0.13) | 0.026* |

| LAL, n=16 | ||||

| Sphere, D | −0.672±1.052 (−2.75 to +0.75) | −0.563±0.951 (−2.75 to +0.75) | 0.109±0.408 (−0.50 to +1.00) | 0.301 |

| Cylinder, D | −0.422±0.405 (−1.75 to 0.00) | −0.375±0.500 (−1.75 to 0.00) | 0.047±0.306 (−0.50 to +0.50) | 0.558 |

| SE, D | −0.883±1.160 (−3.38 to +0.50) | −0.750±1.067 (−3.13 to +0.75) | 0.133±0.448 (−0.75 to +1.00) | 0.254 |

| Axis, degrees | 76.50±66.66 (10.00 to 180.00) | 113.60±61.28 (35.00 to 180.00) | 37.13±80.01‡ (−116.00 to +170.00) | 0.092 |

| CDVA, logMAR | 0.084±0.137 (−0.13 to +0.48) | 0.0572±0.072 (0.00 to +0.18) | −0.027±0.131 (−0.48 to +0.13) | 0.875 |

Notes: *Statistically significant with a p-value <0.05. ‡Positive differences refer to counterclockwise change, negative differences refer to clockwise change.

Abbreviations: CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; D, diopter; LAL, light adjustable lens; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SD, standard deviation; SE, spherical equivalent.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of YAG capsulotomy on refraction, SE, and CDVA in a large sample of patients based on pre- and postoperative assessments.

We found no change in sphere or axis at either one-month or one-year follow-up visits when compared to preoperative values. CDVA was significantly improved from baseline at both time intervals, as expected, given the nature of the YAG procedure. Interestingly, there was also a statistically significant reduction in cylinder one month and one year postoperatively compared to preoperative values (differences of 0.042±0.448 D and 0.101±0.455 D, respectively). Upon stratification of cylinder (Figure 2), postoperative values demonstrated an improvement in the distribution of cylindrical power compared to preoperative values, confirming that cylinder improves after YAG capsulotomy. Although the exact cause for this difference is unclear, it may be due to a potential shift in lens position with time or a larger capsulotomy.9,10 Uzel et al analyzed 29 patients undergoing YAG capsulotomy for PCO and noted a statistically significant decrease in angle of tilt after the procedure but no effect on decentration.11 Given that tilt and decentration of an IOL causes astigmatism,11 their findings support our results regarding cylinder decrease. Considering this present study is limited by the absence of data on lens position, tilt, and decentration, we are unable to confirm that the observed cylinder change is a result of these lens changes. Since there was no observed change between the one-month and one-year postoperative measurements (Table 2), we can rule out extenuating circumstances after capsulotomy as being the cause of significant cylinder change observed at the analyzed timepoints.

It is also possible that by cleaning the medium and resolving the central opacities as a result of YAG capsulotomy, patients can discern the error of the cylinder better. In other words, patients are able to see better after YAG capsulotomy and can detect subtleties in their vision. Thus, true cylinder measurements are obtained with no real change in measurements caused by capsulotomy. This hypothesis is strengthened by the lack of observed statistical significance in SE or axis at the one-month and one-year timeframes. However, this decrease in cylindrical power at one-month and one-year postoperatively may not be clinically significant. There does not seem to be a large centroid shift at either timeframe nor does there seem to be a substantial shift in distribution (Figures 1 and 2). However, we cannot say with certainty that the cylinder decrease is clinically irrelevant as in-depth analysis showed a statistically significant p-value.

Although existing studies analyzed similar parameters, they are considerably smaller in sample size, have limited follow-up intervals, and are somewhat conflicting (Table 4). Many studies have concluded that refractive changes after YAG capsulotomies are not significant.11–22 Three studies noted a hyperopic shift after the procedure,23–25 while two observed a myopic change.26,27 Many of these studies do not assess cylinder independently. Of the six that did, only two noticed a statistical change in cylinder at the latest follow-up visit, with both of those changes decreasing in magnitude,26,28 supporting our results. Khambhiphant et al found a decrease in cylinder one week postoperatively, which returned to the preoperative level at the three-month mark.29 However, this study suggested that this transient change may not be clinically significant.

Table 4.

Comparison of Prior Studies Assessing Refractive Changes After Nd:YAG Capsulotomy†

| Study | Year | Eyes, n | Interval Between Both Procedures (Months) | Latest Follow-Up Interval (Months)a | Δ Sphere, D | Δ Cylinder, D | Δ SE, D | Δ Axis, Deg‡ | Δ CDVA, logMAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thornval17 | 1995 | 52 | 23 | ~1 | - | - | −0.06 | - | - |

| Hu28 | 2000 | 53 | 39 | 3 | - | −0.45* | −0.06 | - | - |

| Chua12 | 2001 | 42 | 24 | 1 | - | - | 0.04 | - | - |

| Yilmaz15a | 2006 | 80 | 11.5 | 3 | - | - | 0.38c | - | 0.58* |

| 48 | 0.22c | 0.62* | |||||||

| Ozkurt14 | 2009 | 26 | 15 | 3 | 0.02 | 0.55* | |||

| Levy19 | 2009 | 24 | >6 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.06 | −0.36* | ||

| Vrijman18 | 2012 | 75 | 14 | 3 | - | - | −0.04b | - | −0.07* |

| −0.1*b | |||||||||

| Karahan24a | 2014 | 36 | 32 | 3 | - | - | 0.23* | - | −0.4* |

| 32 | 0.46* | −0.5* | |||||||

| Oztas26 | 2015 | 30 | >6 | 1 | −0.4* | 0.69* | −0.03 | - | −0.47* |

| Khambhi-phant29 | 2015 | 47 | 28.3 | 3 | - | 0.02 | −0.02 | - | - |

| Cetinkaya21 | 2015 | 20 | 26.09 | 1 | - | - | 0 | - | −0.51* |

| 23 | 0.08 | −0.57* | |||||||

| 19 | 0.06 | −0.49* | |||||||

| 23 | 0.05 | −0.49* | |||||||

| Ramachand-ra16 | 2016 | 35 | >6 | 3d | - | - | −0.21 | - | −0.3* |

| Uzel11 | 2018 | 29 | 22.6 | 1 | - | - | 0.16 | - | −0.34* |

| Monteiro22a | 2018 | 55 | 37.8 | 1 | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.12 | - | - |

| 55 | 40.6 | −0.11 | 0.25 | 0 | |||||

| Akmaz27a | 2018 | 35 | 21.2 | 1 | −0.28* | −0.14 | −0.1 | - | −0.25* |

| 30 | 22.3 | −0.19* | −0.01 | −0.17* | −0.24* | ||||

| Cao20a | 2018 | 20 | 12.42 | 3 | - | - | −0.18 | - | −0.58* |

| 21 | −0.14 | −0.42* | |||||||

| Parajuli13a | 2019 | 56 | 3.26 | 1 | - | - | 0.05 | - | - |

| 40 | 2.46 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Sirakaya25 | 2019 | 35 | >6 | 1 | - | - | 0.49* | - | - |

| Lee23a | 2022 | 25 | 9.88 | 1 | - | - | 0.35* | - | −0.5* |

| 34 | 16.03 | 0.16* | −0.45* | ||||||

| Current Study | 2022 | 605 | 47.75 | 1 | −0.03 | 0.04* | −0.02 | −2.1 | −0.12* |

| 211 | 12 | 0.03 | 0.10* | 0.08 | −5.2 | −0.12* |

Notes: *Statistically significant change with a p-value <0.05. †Includes studies in which we could identify differences in pre- and postoperatively mean for at least one of the following parameters: sphere, cylinder, SE, axis. ‡Positive differences refer to counterclockwise change, negative differences refer to clockwise change. aEyes were stratified, so each sample size within the study corresponds to a specific category established by the authors. bCalculated by subjective refraction and autorefraction, respectively. cP-values were not calculated.

Abbreviations: CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; D, diopter; deg: degree; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; Nd, neodymium; YAG, yttrium-aluminum-garnet; SE, spherical equivalent; Δ, change.

The single-piece and three-piece lens groups showed no statistically significant change in sphere, cylinder, SE, or axis between the pre- and postoperative measurements. However, both groups had a significant improvement in visual acuity. Khambhiphant et al assessed changes between 25 eyes with single-piece IOLs and 22 eyes with three-piece IOLs, and they found no statistical change in SE or cylinder in either group postoperatively.29 On the other hand, Akmaz et al found a significant myopic change in spherical error in the single- and three-piece lens groups and a significant myopic change in SE in the three-piece lens group.27

LALs specifically have not been thoroughly evaluated in YAG capsulotomy procedures. While classified as a three-piece lens, LALs have an adjustable refractive power after surgery,30 which is in stark contrast to non-adjustable IOLs. In the 16 patients with LALs in the present study, YAG capsulotomy had no statistically significant effect on the SE, sphere, cylinder, or axis. However, no significant change in CDVA before and after the YAG procedure was found (p = 0.875). This lack of statistical significance, including the VA, may be attributed to a small sample size bias. While our data suggest that the YAG capsulotomy has little to no impact on refractive values of LALs, additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to substantiate these findings. Due to the nature of their lenses, we believe that patients with LALs may notice more subtle differences in their CDVA caused by opacification compared to patients with other types of lenses. Thus, they may have been more inclined to undergo YAG procedures due to their potentially lower threshold for CDVA changes. Eyes in the LAL group had a better preoperative CDVA logMAR with a mean of 0.084±0.137 while all the other groups in our study had mean CDVA logMAR values of greater than 0.1. The patients with LALs already had better vision before the procedure compared to other groups which may explain the statistically insignificant difference in CDVA afterward.

Another limitation of our study includes lack of patient stratification based on PCO-level classification to determine whether the severity of PCO had an impact on manifest refraction. Although the change in cylinder was determined to be statistically significant, the pre-YAG refraction may be inherently limited due to the PCO, thus potentially drawing an inaccurate comparison between the pre- and post-YAG refraction values. Furthermore, criteria for clinical significance were not established, so it is difficult to confidently say that we do not believe the cylinder change is clinically significant. Additionally, both postoperative timepoints contain different sample sizes with only some overlap. However, we used paired t-tests between the preoperative and two postoperative intervals as well as between the one-month and one-year follow-up timeframes to discern any changes that may have occurred due to and after the procedure. Despite maintaining a large sample size, we suggest future studies include a larger sample size of patients with consistent follow-up visits. We also did not evaluate keratometry values because we surmise that the Nd:YAG laser has hardly any impact on corneal tomography or topography. Because there is no physiological mechanism that would alter the corneal curvature, we did not think there would be any benefit to this analysis. Furthermore, patients were not stratified based on time between the original cataract surgery and YAG capsulotomy. Considering the mean interval between procedures was 47.8±43.6 months (range, 1.1 months to 22.1 years), there may have been some inherent differences in these patients. It is possible that patients undergoing early YAG capsulotomies compared to those undergoing later procedures may have had varying postoperative refractive shifts.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the expected improvement in CDVA at both one month and one year follow-ups as well as in single and three-piece lenses. Our results show that Nd:YAG capsulotomies appear to cause a statistically significant, but arguably clinically negligible, decrease in cylinder magnitude. The type of lens does not alter the change in postoperative refractive measurements. Due to the increasing incidence of cataract surgery,31 the rise of IOL placement will increase the risk of PCO formation and the need for Nd:YAG capsulotomy. Despite lack of clinical change in refractive error and SE after the YAG capsulotomy, we suggest that patients be refracted after the procedure due to their improvement in CDVA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Awasthi N. Posterior capsular opacification. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(4):555. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konopińska J, Młynarczyk M, Dmuchowska DA, Obuchowska I. Posterior capsule opacification: a review of experimental studies. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2847. doi: 10.3390/jcm10132847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wormstone IM, Wormstone YM, Smith AJO, Eldred JA. Posterior capsule opacification: what’s in the bag? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;82:100905. doi: 10.1016/J.PRETEYERES.2020.100905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonnell PJ, Green WR, Maumenee AE, Iliff WJ. Pathology of intraocular lenses in 33 eyes examined postmortem. Ophthalmology. 1983;90(4):386–403. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(83)34558-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nanu RV, Ungureanu E, Instrate SL, et al. An overview of the influence and design of biomaterial of the intraocular implant of the posterior capsule opacification. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2018;62(3):188–193. doi: 10.22336/rjo.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Findl O, Buehl W, Bauer P, Sycha T. Interventions for preventing posterior capsule opacification. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2017:2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003738.PUB3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooksley G, Lacey J, Dymond MK, Sandeman S. Factors affecting posterior capsule opacification in the development of intraocular lens materials. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:6. doi: 10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS13060860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abulafia A, Koch DD, Holladay JT, Wang L, Hill W. Pursuing perfection in intraocular lens calculations: IV. Rethinking astigmatism analysis for intraocular lens-based surgery: suggested terminology, analysis, and standards for outcome reports. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(10):1169–1174. doi: 10.1016/J.JCRS.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findl O, Drexler W, Menapace R, et al. Changes in intraocular lens position after neodymium: YAG capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25(5):659–662. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu CY, Woung LC, Wang MC. Change in the area of laser posterior capsulotomy: 3 month follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(4):537–542. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(00)00645-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uzel MM, Ozates S, Koc M, Taslipinar Uzel AG, Yılmazbaş P. Decentration and tilt of intraocular lens after posterior capsulotomy. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2018;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2018.1443146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua CN, Gibson A, Kazakos DC. Refractive changes following Nd: yAGcapsulotomy. Eye. 2001;15(Pt 3):304–305. doi: 10.1038/EYE.2001.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parajuli A, Joshi P, Subedi P, Pradhan C. Effect of Nd: yAGlaser posterior capsulotomy on intraocular pressure, refraction, anterior chamber depth, and macular thickness. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:945. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S203677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozkurt YB, Sengör T, Evciman T, Haboğlu M. Refraction, intraocular pressure and anterior chamber depth changes after Nd: yAGlaser treatment for posterior capsular opacification in pseudophakic eyes. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92(5):412–415. doi: 10.1111/J.1444-0938.2009.00401.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yilmaz S, Ozdil MA, Bozkir N, Maden A. The effect of Nd: yAGlaser capsulotomy size on refraction and visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 2006;22(7):719–721. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20060901-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandra S, Kuriakose F. Study of early refractive changes following Nd: YAG capsulotomy for posterior capsule opacification in pseudophakia. Indian J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;2(3):221. doi: 10.5958/2395-1451.2016.00048.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thornval P, Naeser K. Refraction and anterior chamber depth before and after neodymium: yAGlaser treatment for posterior capsule opacification in pseudophakic eyes: a prospective study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1995;21(4):457–460. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vrijman V, van der Linden JW, Nieuwendaal CP, van der Meulen IJE, Mourits MP, Lapid-Gortzak R. Effect of Nd: yAGlaser capsulotomy on refraction in multifocal apodized diffractive pseudophakia. J Refract Surg. 2012;28(8):545–550. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20120723-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy J, Lifshitz T, Klemperer I, et al. The effect of Nd: yAGlaser posterior capsulotomy on ocular wave front aberrations. Canadian J Ophthalmol. 2009;44(5):529–533. doi: 10.3129/I09-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao W, Cui HP, Ni S, Guo HK. Influence of size of Nd: yAGcapsulotomy on ocular biological parameters and refraction. Int Eye Sci. 2018;18(10):1847–1850. doi: 10.3980/J.ISSN.1672-5123.2018.10.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cetinkaya S, Cetinkaya YF, Yener HI, Dadaci Z, Ozcimen M, Acir NO. The influence of size and shape of Nd: yAGcapsulotomy on visual acuity and refraction. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2015;78(4):220–223. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20150057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monteiro T, Soares A, Leite RD, Franqueira N, Faria-Correia F, Vaz F. Comparative study of induced changes in effective lens position and refraction after Nd: yAGlaser capsulotomy according to intraocular lens design. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:533. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S156703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CY, Lu T, Meir YJJ, et al. Refractive changes following premature posterior capsulotomy using neodymium: yttrium–aluminum–garnetLaser. J Pers Med. 2022;12(2):12. doi: 10.3390/JPM12020272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karahan E, Tuncer I, Zengin MO. The Effect of ND:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy size on refraction, intraocular pressure, and macular thickness. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2014/846385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sırakaya E, Ağadayı A, Küçük B, Hepokur M. Effect of Nd: yAGLaser capsulotomy on refraction and anterior segment parameters in patients with posterior capsular opacification. Erciyes Med J. 2019;41(3):316–336. doi: 10.14744/etd.2019.65632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oztas Z, Palamar M, Afrashi F, Yagci A. The effects of Nd: yAGlaser capsulotomy on anterior segment parameters in patients with posterior capsular opacification. Clin Exp Optom. 2015;98(2):168–171. doi: 10.1111/CXO.12205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akmaz B, Akay F. Evaluation of the anterior segment parameters after Nd: YAG laser capsulotomy: effect the design of intraocular lens haptic. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(2):322–327. doi: 10.12669/PJMS.342.12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu CY, Woung LC, Wang MC, Jian JH. Influence of laser posterior capsulotomy on anterior chamber depth, refraction, and intraocular pressure. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26(8):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khambhiphant B, Liumsirijarern C, Saehout P. The effect of Nd: yAGlaser treatment of posterior capsule opacification on anterior chamber depth and refraction in pseudophakic eyes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;557. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S80220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz DM, Jethmalani JM, Sandstedt CA, Kornfield JA, Grubbs RH. Post implantation adjustable intraocular lenses. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2001;14(2):339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gollogly HE, Hodge DO, Sauver JL, Erie JC. Increasing incidence of cataract surgery: population-based study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(9):1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/J.JCRS.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]