Abstract

Gang and violence intervention programs have become a staple in American cities. These programs often find themselves navigating turbulent political environments, a challenge that can be exacerbated during times of societal upheaval, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study examines how the pandemic impacted the forms and functions of the Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver (GRID). While GRID coordinates many strategies and collaborates with government and community groups across Denver, its centerpiece intervention entails multidisciplinary teams and street outreach, the focus of this qualitative study. We draw on 197 hours of field-based observation and 19 semi-structured interviews gathered as part of an evaluation of this intervention—initiated prior to the pandemic—to arrive at three key conclusions on the impact of COVID-19. First, upper-level administrative support can be a critical factor in agency efficacy and morale. City government's tenuous familiarity and ties with GRID was consequential to non-essential classification at the early stage of the pandemic. Second, agency leaders are crucial advocates for their agency, as GRID navigated many challenges without stable leadership and suffered as a result. Finally, interagency collaboration and relationships are slow to develop and easy to lose, made even more fragile in times of crisis. We discuss these findings in the context of large-scale federal investment in community violence intervention.

Keywords: Gang intervention, COVID-19, Street outreach, Multidisciplinary teams, Violence reduction

Owing to high levels of violence and the service needs among gang populations, organizations tasked with gang intervention are a staple in American cities (e.g., Ervin et al., 2022; Tita & Papachristos, 2010), including the site of our study, Denver. Some are grassroots organizations, such as the Gang Rescue and Support Project. They rely on contracts, donations, and grants to sustain their services. Others are nested within city government, such as the Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver (GRID), supported by general fund allocations. A common theme uniting just about all agencies and programs tasked with gang intervention is the enduring challenge of organizational instability. Political priorities, leadership, personnel, resources, and the gangs themselves are constantly evolving in cities throughout the country.

These issues are magnified when societies experience instability, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and a record increase in homicide in 2020 and its continuance through 2021, which has been attributed, in part, to fluctuations in gang activity. Headlines such as “L.A.'s Surge in Homicides Fueled by Gang Violence, Killings of Homeless People” (Rector & Santa Cruz, 2020) and “At Least 5 Shooters Involved in Downtown Sacramento Shooting, Which Police Called Gang-Related” (Ahumada & Stanton, 2022), are mainstays of American news coverage and often elicit outcry from the public and responses from politicians and law enforcement (Maxson, Curry, & Howell, 2002). However, research in cities like Los Angeles has demonstrated that the volume of gang violence has remained stable (Brantingham, Tita, & Herz, 2021). Still, since most organizations are often funded by taxpayer dollars, they are beholden to political expectations. Programs such as the Little Village Project in Chicago (Spergel, 2007) and SafeFutures in St. Louis (Decker & Curry, 2002) operated in a space between political turmoil and executing their programmatic model within communities.

This study examines gang intervention in the COVID-19 era in Denver, Colorado. We focus on the pandemic-induced disruptions to, and adaptations made by, the Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver (GRID), housed in the City and County of Denver's Department of Public Safety. GRID's core intervention components—multidisciplinary teams and outreach workers—are the focus of this article, as they were the subject of an impact and a process evaluation prior to the onset of the pandemic. Having been in the field since mid-2019, this afforded a unique opportunity to assess how COVID-19 impacted the forms and functions of the predominant gang intervention in the Denver area. We draw on 19 semi-structured interviews with individuals involved in the GRID network and 197 hours of field observation of meetings and shadowing outreach workers to explore how COVID-19 disrupted program referrals and service provision, as well as adaptations made by GRID and network partners in response to restrictions imposed by the pandemic and local government.

We frame COVID-19 as an extreme shock to the system but in a similar vein to other stressors, such as natural disasters, with immediate and long-term impacts. It is important to note that events such as COVID-19 has required agencies—from municipalities to the federal government—to make difficult decisions about their operations and services (e.g., Ansell, Boin, & t'Hart, P., 2014). This was most evident when local governments across the United States determined who was and was not an essential service provider. We begin by situating the current study within the tumultuous history of gang interventions. Next, we briefly discuss Denver's gang history and key events that led to the creation of GRID. We then present the qualitative methods used to understand the extent to which COVID-19 altered gang intervention in Denver. After presenting our findings, which focus on how COVID-19 impacted the practices and strategies of street outreach and the operations of the multidisciplinary teams, we discuss these findings in the context of gang intervention during times of economic, political, and social instability and offer suggestions to bring about greater stability in organizations, which takes on added importance in light of federal priorities supporting alternatives to business-as-usual approaches to gangs and violence—policing, prosecution, and corrections—with community-based violence intervention and prevention (The White House, 2021, The White House, 2022a). Gravel, Bouchard, Descormiers, Wong, and Morselli (2013) noted, however, that program evaluations have been lacking in clear objectives, processes to achieve objectives, and some did not include evaluations at all.

1. The challenges of gang intervention

Even under “normal” circumstances gang interventions are replete with turbulence. Spergel, Sosa, and Wa (2004) noted that there are many factors leading gang interventions to fail, including weak implementation, interagency conflict, and insufficient resources, among others. Vargas (2019) provided an example of interagency conflict. An agency in Little Village, Chicago, whose leadership made key decisions to protect its funding and political clout by excluding other agencies from meetings with political leaders, was accused by other agencies of engaging in what Vargas called “gangstering for grants.”

In an evaluation of what has become known as the Comprehensive Gang Model,1 Spergel (2007) stated that comprehensive, community-based “gang projects that require institutional change are highly vulnerable to failure. Few innovative—if even effective—programs survive, or develop further, unless they serve and sustain important organizational and political interests” (p. 327). Spergel detailed how the Chicago Police Department was supposed to have taken charge of the project, but priority was given to other projects such as community policing. Chicago PD's leadership decided it was not interested in working with other agencies unless they aligned with their focus on suppression strategies. Spergel emphasized that the project was targeting the right individuals and providing services (e.g., employment or educational) that reduced risk of arrest (for both violence and drugs). Still, the decisions made by the Chicago PD's leadership and a lack of support from key stakeholders, such as the mayor and community organizations, ensured that program termination was inevitable. The inability of organizations to unite around common problems is not unique to Chicago or the Little Village Project.

Decker and Curry (2002) studied the implementation of the Comprehensive Gang Model in St. Louis as part of the SafeFutures intervention. Some agencies would find reasons to not cooperate or deliver the services they received money to implement. Service providers often found themselves ill-equipped to serve those who were gang involved. Community-based agencies held contentious relationships with the police department because some of their staff were former gang members. Decker and Curry discussed “program drift,” that is, straying away from the original goals or constructing new ones, as the agencies attempted to adapt to the “realities of program implementation and operation” (p. 209). Evaluations of other gang comprehensive model sites, including Indianapolis, Los Angeles, San Antonio, and Riverside, illustrated challenges associated with implementation, interagency cooperation, and political pressures (Cahill et al., 2015; Spergel, Wa, & Sosa, 2005a; Spergel, Wa, & Sosa, 2005b; Thelin, Stucky, Nagle, & Newby, 2012).

The above examples illustrate the volatile nature of gang programming. Political pressures, competition for resources, and organizational instability are just some of the many challenges faced by agencies delivering services to a population that itself can be difficult to work with. Further, these challenges are not unique to the comprehensive gang model and they apply to government-led responses, such as the Los Angeles Mayor's Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (Cahill et al., 2015), and non-government-led responses, such as Cure Violence (Papachristos, 2011; Wilson & Chermak, 2011). As we will discuss, GRID is not impervious to any of the challenges that gang interventions often face. The difference is that we seek to understand how an external shock to the system—the coronavirus 2019 pandemic—impacted the predominant gang intervention in the Denver area. While criminologists have written extensively about the COVID-19 pandemic (Piquero, 2021), focusing on crime (Abrams, 2021; Miller & Blumstein, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020), policing (Nielson, Zhang, & Ingram, 2022; Nix, Ivanov, & Pickett, 2021), and corrections (Novisky, Narvey, & Semenza, 2020; Pyrooz, Labrecque, Tostlebe, & Useem, 2020), to the best of our knowledge, only a brief case study exists of a community-based violence reduction program in Rochester, New York, which was tangentially related to gang violence (Altheimer, Duda-Banwar, & Schreck, 2020). Having been in the field conducting an impact and process evaluation of GRID before the onset of the pandemic, we were well positioned to document continuities and changes to the forms and functions of GRID.

2. The Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver

The contemporary gang landscape of Denver can be traced back to the 1980s (Durán, 2013). Latino gangs began to appear in the west side of Denver and concentrating in neighborhoods like Westwood (Durán, 2013). According to one GRID outreach worker, gangs like Byers Hood, Ruthless Menace Gang, Westwood Huds, and Inca Boyz are some of the dominant gangs in the west and southwest of Denver. Predominantly Black gangs are generally located in the eastern and northeastern part of Denver. The Rollin 30s Crips of Denver formed in 1985 operating out of the Five Points neighborhood and the Park Hill Bloods shortly thereafter several blocks to the east near Holly Square (Rubinstein, 2021).2 Some of Denver's oldest gangs, like the East Side Oldies and the Chiqui 30s are also located in the east/northeast neighborhoods such as Montbello and Globeville. Key events such as the 1993 “Summer of Violence” and the 2007 murder of Denver Broncos player Darrent Williams—both events garnered national and statewide attention to gang violence—spurred heavy reactions from Denver city officials to address gang violence (Brown, 2007). One such response was Denver developing a protocol for collecting intelligence in a gang database. The policy went so far as to state that even if the criteria to identify someone as a gang member was not met, the police could, at their discretion, consider someone a “gang associate” (Bond, 2004). The result was 2 out of 3 young Black men being classified as gang members (D. Johnson, 1993). Denver police began mobilizing against gangs in the 1980s with grants, the establishment of a gang task force, and training from Los Angeles police (Durán, 2013). However, as Durán (2013) noted it was in the 1990s—with the 1993 Summer of Violence as a major catalyst—that Denver officials cracked down on gangs with the establishment of gang units operating at the federal, local, and prosecutorial levels. Other tactics, like allowing schools to ban certain colors, curfews, and lower ages for juvenile to adult transfers, were enacted.

Shortly after the Darrent Williams murder, GRID was established in 2009 to address gang violence in Denver (Tomberg & Butts, 2016). Based on the comprehensive gang model, GRID is involved in the development and support of various prevention, intervention, and suppression programs and strategies while also serving as a network hub connecting various government agencies and community organizations. The focus of the larger impact and process evaluation and this article is on the centerpiece of GRID's violence reduction efforts: the use multidisciplinary teams and street outreach workers to promote disengagement from gangs and desistance from crime among people referred for services.

At any given time, GRID may consist of up to eight employees: a director, program coordinator, outreach coordinator, and five outreach workers. Outreach workers participate with representatives from partnering agencies—regular partners include juvenile probation, Denver pre-trial services, community corrections (e.g., halfway houses), Denver Police Department, Denver Department of Human Resources, CO Department of Corrections (e.g., parole)—to form two multidisciplinary teams, one for juveniles (the Intervention Support Team) and one for adults (the Adult Systems Navigation team). Each multidisciplinary team is scheduled to meet monthly to develop and execute coordinated case plans for the clients referred to GRID, which come from a variety of sources.3 GRID aims to serve young people with ties to the city of Denver who are actively involved in gangs and have expressed a willingness to change.4 While expressing a willingness to change is not a requirement for GRID services, it can guide in whom GRID invests its resources or whether a referral is submitted by an agency (see also Cheng, 2017). Lastly, GRID will only accept referrals for incarcerated individuals if their expected release date is no more than 30 days.

It has been commonplace for gang intervention programs to make use of street outreach workers to engage with gang members and serve as violence interrupters (Arbreton & McClanahan, 2002; Brunson, Braga, Hureau, & Pegram, 2015; Hureau et al., 2022; Klein, 1971; Tita & Papachristos, 2010). While many programs employ former gang members, GRID's outreach team is comprised of people with different backgrounds, including former gang members, former justice agency workers, or mental health services backgrounds. Lopez-Aguado (2013) argued that outreach workers often possess “street liminality” which allows them to navigate working with gang members while simultaneously working with city agencies, including those in criminal justice. This may be especially salient for GRID's outreach workers as they are employed directly by the city of Denver. Decker and colleagues (2008) outlined the models under which outreach workers may serve:

-

1.

A clinical model using clinical social workers to deliver services.

-

2.

Program-based models task outreach workers to engage with youth on the street and refer them to services.

-

3.

Street-based interventions requiring their outreach workers to mediate conflicts as a means of violence reduction and potentially refer youth to services.

The GRID outreach workers generally fall under the program-based model as they are expected to engage with clients and connect them with the appropriate services. Their role on the multidisciplinary teams is to advise on gang dynamics unlikely to be documented and/or interpreted by partner agencies, such as intra- and inter-gang conflicts occurring in neighborhoods or schools, while suggesting appropriate services needed by the client as part of their coordinated case management. Outreach workers are also tasked with identifying three specific areas of improvement for their clients that directly addressed their gang involvement which is to be shared with the multidisciplinary teams.

Fig. 1 illustrates the sequencing of services and program involvement in GRID. All people accepted into the GRID program are vetted by the outreach coordinator before beginning at the engagement level. These referrals must be unanimously approved by the corresponding multidisciplinary team at the monthly meeting to advance to level 1. Subsequent movement is not voted upon but may be discussed if a multidisciplinary team partner raises objections. Caseloads for the GRID outreach workers are ideally between 20 and 25 clients. Outreach workers were encouraged to assist their clients with issues such as attending supervisory meetings (e.g., probation) or obtaining essential documents (e.g., identification). Outreach workers would also visit their youth clients at their respective schools to make sure they were attending and keeping up with their work. Taking clients out to eat at fast food restaurants was also common. While these activities were encouraged, outreach workers were often warned to not become “chauffeurs” or “free meal tickets” for their clients (see also Cheng, 2018). Clients were often visited or picked up at their homes by their outreach worker.

Fig. 1.

GRID outreach levels of services.

FTF=face-to-face. GRID has two additional levels that are not part of the chronological movement of services: Level 4 and Hold. Clients are automatically moved to level 4 when they are put into custody for less than 30 days. A client being held for longer than 30 days is closed as unsuccessful. The hold level is reserved for clients on the run. Outreach workers are only allowed phone contact to encourage their client to turn themselves in.

3. Methods

The formal impact and process evaluation of GRID began in 2019. The research team initiated a randomized controlled trial and field-based observations of multidisciplinary team and GRID meetings in June. About 9 months later, when the state of Colorado was subject to stay-at-home orders on March 16th, 2020, the evaluation had to be revamped to facilitate virtual data collection. Field observations were shut down for a six-week period while GRID determined how to move their meetings online and to re-envision service delivery. At the pandemic's early stage, based on initial observations of GRID's operational adjustments, we pursued IRB amendments to expand qualitative data collection tailored to COVID-19 and its perceived impacts on service delivery specifically and the network generally. Prior to the formal evaluation the research team had spent nearly two years conducting a pilot study (Pyrooz, Weltman, & Sanchez, 2019), creating familiarity and trust with the GRID leadership, outreach workers, and many partners in the network. The lead author spearheaded qualitative data collection in the full-scale evaluation.

The current study draws on semi-structured interviews and field observations of various people and groups involved in gang intervention in Denver, including shadowing outreach workers and observing their delivery of gang intervention services. Shadowing outreach workers had originally been scheduled to start summer 2020 but the emergence of COVID delayed this until summer 2021 when safety protocols were relaxed. Qualitative methods allow for the “understandings of experiences, perceptions and processes, in context and from the perspective of those being studied” (Tewksbury, 2009, p. 54). In short, field observation and qualitative interviews allow us to explore how the GRID team and the multidisciplinary team partners process, adapt to, and interpret changes to their work because of the pandemic. Interviews were conducted with 19 people between August 2020 and March 2021. Although these interviews were conducted as part of a larger evaluation of GRID, all participants were asked questions pertaining to COVID-19.

Our recruitment procedures relied on convenience and snowball sampling. The lead author regularly attended multidisciplinary team meetings, which made the recruitment of core participants a prudent starting point. Members of the juvenile and adult multidisciplinary teams were contacted individually via email to request their participation in an interview. Any person who agreed to interview signed a form indicating their consent to participate in the study. The only criterion for inclusion in the interviews was involvement with the GRID network at any point in their careers, although all participants were actively or recently involved. At the conclusion of an interview the participants were asked if they were aware of anyone else in their agency or elsewhere with experience working with GRID. While convenience and snowball sampling may have their limitations—namely, selection bias—the method has long been used to access populations that could not be otherwise studied (Atkinson & Flint, 2001; Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981; Wright, Decker, Redfern, & Smith, 1992) and is well-suited for the study of multidisciplinary teams and street outreach (e.g., Cheng, 2017, Cheng, 2018).

The final sample consisted of eight current or former employees of GRID, four employees of local law enforcement who work closely with GRID, four employees from juvenile justice agencies, two members of adult-serving city and county agencies, and one outreach worker from a community organization that partners with GRID. We attempted to recruit more representatives from adult serving agencies. A total of 5 additional people were contacted, however, two refused and three ignored our attempts. Pseudonyms were assigned to participants to maintain confidentiality. Of the 19 total interviews, 13 took place via a videoconferencing program (Zoom). Interviews began in August 2020 and stay-at-home orders had been relaxed, so participants were given an option to do the interview online or in-person. The interviews ranged from 20 min to almost two hours in length. An interview script was developed for these interviews; however, the interviews were semi-structured such that questions were not always asked in order and were merely meant to guide the conversation.

Field observations were split into two distinct periods: pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19. Field observations are well-suited to observe the processes of the multidisciplinary team meetings and outreach worker activities (Gobo & Marciniak, 2011), which is a core part of GRID's model. This includes service delivery to people who were referred, enrolled, and serviced by GRID, as well as understanding the changes in GRID's operations once COVID-19 took hold. With few exceptions, a member of the research team attended every monthly youth and adult multidisciplinary team meeting from June 2019 to December 2021. All the multidisciplinary team members were made aware of the research team's presence and reason for attending. Starting in June 2021 we would shadow the outreach workers during a workday and observed them interact with their clients.

A total of 197 hours of field observation were logged, of which 39.5 hours were pre-COVID-19 and 157.5 hours of observations occurred after March 16, 2020, which is when the stay-at-home order went into effect. The pre/post period allow us to contrast changes brought about by COVID-19, a rare feature in qualitative research generally and gang intervention research specifically. Of the 39.5 pre-COVID-19 hours, 22 were collected from multidisciplinary team meetings, 14 from internal GRID meetings, and four additional hours from impromptu meetings with GRID. About 38 of the COVID-19 era field hours were from multidisciplinary team meetings, 75 from internal meetings, and 45 came from field-based shadowing of outreach workers.

All the interviews were transcribed by a professional agency and, along with the field notes, were stored on a secure server at the university with which the authors are affiliated. Coding was done using the MaxQDA software. A priori codes were developed to help focus on the key questions such as COVID-19 and Violence, but open coding was also conducted to avoid depriving the current study of potentially key ideas (Richards, 2020). The codes were then housed under individual abstract themes to aid with the organization of the data. The current study leverages these organized data to highlight the impact of COVID-19 not only on GRID, but other agencies tasked with gang intervention and violence reduction.

4. Results

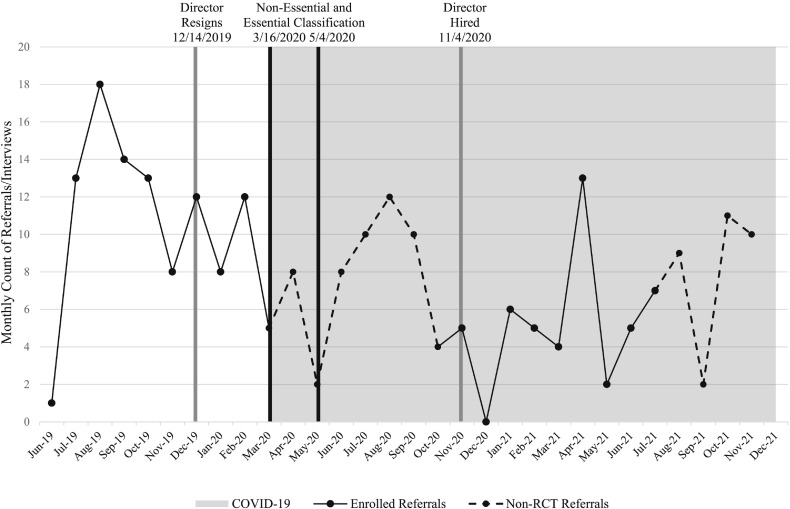

Fig. 2 contains a timeline of key events and processes over the study period, June 2019 to December 2021. Prior to the pandemic, GRID was receiving an average of 11 referrals per month. This number dropped to an average of 7 per month after COVID-19. Being that GRID employs outreach workers to deliver services to gang involved clients, referrals from partnering agencies are the lifeblood of GRID. Both these data and our qualitative data affirm the impact of COVID-19 on referrals to GRID. Other agencies experienced severe restrictions on their service delivery and had to adapt to the evolving landscape (e.g., halfway houses), which in turn was consequential for GRID, as we elaborate upon in the sections below.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of GRID referrals, qualitative interviews, and key events.

The figure also highlights four key events that took place. The first was the resignation of the GRID director in late 2019. GRID's director had been a key figure in the program's establishment over a decade ago, its development into a city agency, and growth as Denver's marquee gang intervention agency. It took nearly 11 months for a new director to be hired. Not illustrated in the figure, but also impactful, was the departure of the longstanding program coordinator about two months prior to the director's resignation. The coordinator had effectively served as the deputy director and handled GRID's day-to-day affairs and oversaw the outreach workers. This left GRID with only one administrator shortly before the outbreak of COVID-19. An interim director was assigned to GRID, but it was the remaining coordinator that had to assume the day-to-day responsibilities of the director and both coordinator roles. This led to a tense relationship between him and the outreach workers. As we discuss below, the 11-month wait to hire a new director was a strategic move by city administration to aid with budgeting pressures but had unintended ramifications. The next two key events were the initial classification of GRID as a non-essential agency for approximately six weeks, followed by reclassification as essential once an increase in violence became evident.

It is also critical to note that even before the pandemic, GRID had a cynical view of the leadership in Denver. From attending the team meetings, we observed several instances where the outreach team and the coordinators discussed how representatives from the mayor's office, city council, and Denver Department of Public Safety administration would attend team meetings and express a desire to “ride” (i.e., observe) with the outreach workers but, to the best of our knowledge, the administrators never followed through. These feelings of discontent frame how several of the outreach workers believe city officials view them and their work.

Our analysis of observational and interview data resulted in several key themes, which we organize into two sections: (1) the delivery of gang outreach services during COVID-19, which included subthemes of worker classification and service delivery, and (2) the impact of the pandemic on the multidisciplinary teams, which included subthemes of the online transition and organizational instability. The following sections will elaborate on these themes, which are supported by quotations and field notes.

4.1. Gang outreach during COVID-19

4.1.1. “They should have known better”: Worker classification and GRID

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic thrust city agencies into a state of rapid organizational change, exemplified by the decision of Denver city officials to exclude GRID from the agencies and services given essential status, such as the police, gun shops, and marijuana dispensaries (KDVR, 2020). These decisions intersected at a time when GRID was already undergoing major changes. At the start of 2020, GRID was operating with four vacancies: two outreach workers had left the organization, the departure of a coordinator, and the director's resignation. GRID had started the outreach worker hiring process to fill one outreach vacancy in late 2019 and by mid-February a new outreach worker had been hired. This outreach worker, Albert, had the misfortune of having March 16th, 2020, as his first day on the job, when stay-at-home orders were issued. We spoke to him about this experience, and he said it was a tough start because his training was done virtually, and he could not shadow the more experienced outreach workers.

The other three positions were also supposed to be filled in early 2020, but the pandemic brought the hiring process to a halt. It was then decided by the interim director and other officials to leave them unfilled for a longer period to meet the city's budget cut requirements. This meant that the GRID team had to work with three key vacancies and a non-essential classification at the onset of COVID-19. These decisions made by key leadership figures were met with skepticism and frustration by the outreach workers, who believed that city officials did not understand the nuances, processes, or mechanisms of GRID as a program. Lamont, formerly an outreach worker who had been recently promoted to coordinator, expressed that as one of the smallest agencies in the city, GRID is easily overlooked and forgotten, which may have contributed to GRID being initially classified as non-essential. Matthias, a former GRID outreach worker, when asked about GRID's relationship with the “higher ups,” said:

"I would honestly say in watching some of the City Council meetings online and seeing how the city represents GRID in meetings, they know absolutely nothing about what we do. I mean other than they [GRID] do gang outreach [emphasis added]."

The GRID team believed that if city officials had a clearer understanding of the program and its effect on gang violence, they would have been allowed to continue doing field work. Moriah, a former GRID employee who worked with a partner law enforcement agency, added support to the notion that city leaders may not understand GRID:

"I think because nobody knew how to…Again, not understanding the model and…That's a tough call. I honestly can't tell you what I would have done if I was running GRID at that time. Or I guess I could, but I can't, you [can't] Monday morning quarterback what they did. I think it was nobody really understands the role of the outreach worker [emphasis added]."

The outreach workers partly blamed their leadership void for this lack of knowledge by city officials. Matthias and Mike, one of GRID's coordinators, both expressed that GRID has been historically bad at making its “brand known,” and it got worse once the director left and no one could effectively advocate for GRID in meetings with city officials. Director.

When we probed the outreach workers about how they were managing to maintain cohesion and prevent a drop in morale without stable leadership, the team highlighted the presence of Matthias as a stabilizing presence. Matthias was the longest tenured GRID outreach worker when the evaluation began but left GRID in October 2020 after not being promoted to program director. The impact Matthias' departure may have had on the GRID team was mitigated by the new director being someone the team was already familiar with.

GRID was not reclassified as an essential agency until the first week of May 2020. Mike had learned other cities had classified their gang interventions as essential (e.g., Ren, Santoso, Hyde, Bertozzi, & Brantingham, 2022) and according to the GRID team, this further proved Denver city officials did not appreciate their work. During interviews with the GRID team, it was consensus opinion that Denver's rise in violence (Garrison, 2021) led to the agency being reclassified as essential. Nick, a GRID outreach worker, stated:

"I think it was purely from a COVID standpoint. So, we weren't essential to the safety of the community, in terms of COVID. Like, minimizing the spread of COVID, which we're still not essential to. But I think they saw the uptick in violence and then were like, oh shit, we need to address this…I think the violence that started occurring is what changed the minds of politicians [emphasis added]."

Pam, an administrative member of GRID, mentioned that she met with city officials and was able to get their permission to put the outreach workers back into the field. She leveraged the fact that GRID's reason for existing was to address violence. Mike, described that his warning to city officials fell on deaf ears:

"They waited till after the fact that we had a quite a bit of violence to allow us to be an essential…if they valued our work, they would have valued that we're an essential and we need to be out there at this time. I warned them this was going to happen and they didn't listen."

Mike put responsibility for the increase in violence on Denver officials saying, “they should have known better” when it came to decisions on essential vs. non-essential classification. During our interviews with the partnering agencies, we asked about the importance of GRID to Denver and whether they felt GRID should have been classified as an essential agency from the start. All but one of the participants from partnering agencies we interviewed expressed that GRID was critical to addressing Denver's gang problem. To this end, Luca, a probation officer, stated:

"In my opinion, I think it's imperative [speaking about GRID], if you think outside the box and try to point down or figure out any other, gang intervention program, there's not a whole lot to choose from. And just knowing that it's city funded, and they got some really good people when you get to know them."

Luca further explained he believed GRID should have been on the field because the outreach workers can better relate to gang members than someone like him, “a middle-aged white guy.” Jason, a member of law enforcement in Denver, spoke to GRID's essential status stating: “I think that I would probably look at them as, in retrospect maybe, as being more essential than they probably were designated.”

We learned from Lamont that reclassification also meant GRID only had to cut 7.5% instead of 12% of their budget. During one conversation with Mike, he mentioned the city told GRID they would provide them with personal protective equipment such as masks and hand sanitizer but did not do so until mid-February 2021. This was about 9 months since GRID's reclassification, and it had become yet another source of frustration as the outreach workers were left to equip themselves out-of-pocket. Mike stated they were accustomed to the “lip service” and thus the delay was not surprising.

4.1.2. “It's changed everything we do”: Service provision and violence during COVID-19

Attending GRID outreach team meetings provided insight to concerns the outreach workers may have when delivering services during a pandemic. One of their worries was the fact they could no longer go inside clients' homes. Due to safety restrictions, the outreach workers would meet clients on their porch, backyard, or nearby parks. This presented challenges in the winter months when the weather was extremely cold or snowy. The group felt uneasy for the very issues they sought to address: meetings in public places left them susceptible to violence, such as a drive-by shooting. Lamont expressed the need for vigilance to the team and encouraged them to try and meet clients outside of “hot zones,” or areas with high levels of gang violence.

The unpredictability brought about by the pandemic was concerning to the outreach workers. Albert spoke about his concern:

"It's been kind of stressful how to work it out because every day is different…with the pandemic, there is no routine…the next day I might be meeting you in person, I might be meeting you online. So, it changes constantly."

Albert was referring not only to the reclassification that GRID had to go through but also the change from meeting virtually, to being allowed to have small team meetings in-person, and then moving back online when COVID-19 cases spiked in late summer 2020. We experienced several instances when team meetings would be changed from in-person to remote on short notice. Renato, an outreach worker for GRID, told us that it was annoying having to change his schedule or routines on the fly but that eventually he just stopped caring, “[d]ecided to roll with the punches and go one step at a time.”

Prior to COVID-19, GRID would often spearhead community events, such as Safe Havens, following an act of gang violence in efforts to prevent retaliation. These events provided people from the community a safe space to connect with services (e.g., mental health providers) and cope with violence. The outreach workers would leverage their community connections to gather information from attendees to mediate conflicts. Community canvassing was no longer a viable information stream once GRID was deemed non-essential. Normally, a Safe Haven event would result in representatives from many agencies congregating with community members to gather and share information. Instead of being able to put their expertise to use, GRID became dependent on what the outreach workers viewed as unreliable and more distant avenues.

Even after reclassification, when GRID was allowed to go back into the field and meet with clients, they had strict guidelines to which they adhered. They viewed this as a hinderance because even though meeting in-person was better than phone-based or virtual, it was still not considered optimal. The safety orders meant that outreach workers could no longer engage in some of the services they had previously provided, including driving clients to different locations. Matthias talked about how safety guidelines changed his usual procedures:

"It's changed everything that we do from wearing a mask to carrying hand sanitizer to the way we visit our clients. We used to go into their homes, sit down at a dining room table or in their living room and have conversations with them. Now, we all, we have to stand outside, we have to stay six feet apart, we have to wear all the protective gear, sanitize every single time…So, I think it's changed everything we do [emphasis added]."

These changes in the provision of services, in turn, were believed by the GRID team to be impactful in stunting the core aim of GRID: reducing gang violence.

During one of the outings with Nick, we met a client at his home and spoke to him on the front porch. After a few minutes, the client told Nick that he was feeling ill. Nick quickly took a few steps back and said “[D]ude, you have to tell me this before we get so close.” The client assured us he had not contracted COVID-19 but rather had the flu. On another occasion, Albert went to a motel—where a room had been reserved by a community organization—to meet a new client who was supposed to have been released from prison. When we got there, we learned that the client had not yet checked in and later learned this was due to having been quarantined prior to his release.

Building rapport and engaging clients was a concern among all the GRID outreach workers. Nick gave his thoughts on not being able to meet with clients face-to-face:

"[A]nd to be honest, when we weren't essential and we were stuck at home, making phone calls to clients, it was so frustrating. Because half these kids don't have phones…[a]nd even when they do have a phone, I mean you have such a less engaging conversation [than] in person [emphasis added]."

This reflects their feelings that it is crucial for them to be able to do field work and meet their clients face-to-face. GRID outreach prides itself in being able to engage with gang members in order to be “agents of change” who facilitate crime desistance. From our outings with the outreach workers, we gathered that unannounced visits to schools was one of the most fruitful methods the outreach workers had to meet clients. This approach did not yield an overall high success rate—which they perceived ranged from 25% to 40%—but they felt it mitigated their clients' unreliability in following through on scheduled appointments. However, because of non-essential status and later safety protocols, dropping in on their clients was not feasible or restricted which the outreach workers felt made their jobs harder.

Denver reported its second highest number of homicides (a total of 95) in 2020, a 51% increase over 2019 (FBI, 2019; Schmelzer, 2021). Study participants were asked to reflect on the reasons they believed Denver was seeing such a drastic increase in violence, specifically gang violence. The reasons as to how or why COVID-19 contributed to violence varied even within agencies. For example, Albert said:

"Oh, I believe it got worse. It got worse when we came off because I believe a lot of the violence is happening on social media. And then when we got let out, that's when it goes crazy."

The belief that gang members were increasing their online activity, fomenting online conflicts with offline consequences once stay-at-home orders were relaxed, was shared by other study participants, such as Lamont and Diego, the latter of whom is an outreach worker for a community-based gang intervention agency that partnered with GRID.5 Diego spoke about how COVID-19 forced institutions such as schools to close, which in turn forced young people to rely more on their phones and computers. Diego felt these transitions exacerbated feuds on online platforms which then spilled over to the streets once stay-at-home orders were relaxed. Every time we shadowed an outreach worker, we asked them about keeping tabs on their clients through social media. It was unanimous among the outreach workers that social media was a key tool for them. They all admitted to daily searches of Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok for any gang related activities associated with their clients. While this practice was commonplace even before COVID, the outreach workers stated they increased their efforts to keep tabs on their clients' online activity since they felt the pandemic had shifted a lot of gang activity online. Devvon went as far as saying:

"Yo, it be crazy what the kids be putting on Facebook these days, you know what I'm sayin’? They straight up don't [care] who's watching those videos."

Mike believed that it all came down to gang members adhering to stay-at-home orders for a short period of time before returning to the streets while GRID and their partnering agencies remained unable to do work in the communities.

4.2. The impact of COVID-19 on GRID's multidisciplinary teams

Prior to the pandemic, multidisciplinary team meetings had been held in-person and run by the GRID program coordinator. When our evaluation began, the program coordinator had several years of experience leading the meetings, which were well-organized with a clear agenda. The meetings often exceeded their allotted two-hour schedule by 10–15 min. The program coordinator left GRID in November 2019 and meetings were then run by GRID's director, resulting in several noticeable changes. Off-topic conversations and jokes became rare despite the GRID director never discouraging such interactions. This change in tone was also observed during internal GRID meetings. Meeting cancellations became more common. The content of the discussion was also less consistent. During one meeting, the director had a clear agenda that had been sent out days in advance, outlining which clients would be discussed and asked every outreach worker for three goals to address gang involvement with their new client. During another meeting, the agenda was sent out about a day before and the outreach workers were not asked about client goals. After the program coordinator and director resigned, the task of running the meetings was assumed by Mike. Mike reestablished the structure of the program coordinator. However, the Mike-led multidisciplinary team and internal meetings were only held in-person for January and February 2020, as COVID-19 restrictions took effect and meetings were moved online.

4.2.1. “We will lose the human quality of the relationships”: Multidisciplinary teams and the online transition

The onset of COVID-19 forced GRID to make several decisions. First, multidisciplinary team meetings were cancelled for the month of April before resuming virtually in May. There were several noticeable differences between the in-person and virtual multidisciplinary team meetings which we highlight in Table 1 . The first key difference observed was the reduced number of attendees. The second was attendee engagement during the meeting. In contrast to in-person meetings led by the program coordinator, we observed no informal interactions during virtual meetings. Other than the GRID staff and the lead author, multidisciplinary teams partners kept their cameras turned off, which meant that body language went unobserved. Finally, the virtual meetings always fell short of their allotted two hours. The shortest meeting, an adult meeting lasted only 30 min while the longest, a juvenile meeting, lasted about 115 min—well below the duration pre-COVID-19.

Table 1.

Differences between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 meetings

| Pre-COVID | During COVID | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Support Team (Youth) | ||

| Observations | 7 | 28 |

| Attendees (Mean)a | 10 | 6 |

| Minutes | ||

| Mean | 127 | 113 |

| (SD) | (19) | (49) |

| Range | 105–135 | 60–115 |

| Adult Systems Navigation (Adult) | ||

| Observations | 4 | 20 |

| Attendees (Mean)a | 7 | 3 |

| Minutes | ||

| Mean | 105 | 51 |

| (SD) | (50) | (21) |

| Range | 55–120 | 30–60 |

Note: a. Mean number of attendees do not include the GRID team.

Unlike the internal GRID meetings, which were allowed to happen in-person once reclassification went into effect, the multidisciplinary team meetings had to remain online because of the number of people who may attend them. Most of the outreach workers stated that they disliked the meetings being held online. Matthias mentioned that they seemed to have “lost their character” because everyone was so "serious" and "business-like". Partner agencies brought up changes in the quality of the meetings. They shared how the conversations before and after the meetings prior to the pandemic helped build “comradeship” among the partners. None of the participants felt the work could not get done virtually, but “missed the human interaction.” Jibril, an employee for a juvenile justice agency, expressed this concern:

"[I] think the risk of what's happened since COVID is … it's making it less personal as far as the relationship building…I'm afraid that once we perfect doing it this way, no one will go back to the other way and then we will lose the human quality of the relationships."

This illustrates a point made by others. Not only is it necessary to engage personally with clients but also with colleagues and other members of the multidisciplinary team. Jibril also mentioned that virtual meetings felt “dehumanizing.”

Not everyone felt this way about the meetings, however. Mary, an administrator at a juvenile justice agency, mentioned that she would prefer an online format:

"[I] actually really like it. I think we're actually a little more efficient. It's what most of my meetings, we're bullshitting a little bit less as we get together, we get started a little faster. People are a little more focused."

Efficiency was the overarching theme among those who had a favorable view to the meetings being held online. Pam mentioned people no longer had to worry about needing to find parking or go through security (which included metal detectors and scanning property), something others had mentioned as an annoyance. Pam believed that participation and attendance was higher since moving online. Yet the data we gathered do not comport with this perception, because as we demonstrate in the next section, juvenile and adult meeting attendance fell.

4.2.2. “They weren't doing referrals during COVID”: Organizational consequences of instability

One of GRID's key functions is to serve as a network hub for community organizations and government agencies, brokering the dissemination of information across partners in the network. This function took a hit with the onset of the pandemic as some agencies were classified as essential and had to respond to other issues (e.g., Denver PD navigating COVID-19 and protests of police brutality). Multidisciplinary team meeting attendance suffered. Table 1 demonstrates the drop in multidisciplinary team partner attendance, which contradicts Pam's assessment of participation.

Referrals to GRID also dropped drastically (see Fig. 2), especially adult referrals. Lamont had the following to say:

"[O]ur referrals dipped quite a bit in terms of adult referrals because at one point in time we had more adult clients than juvenile clients. Just before coronavirus hit, Tooley Hall [halfway house] closed down, which hit us hard in terms of adult referrals. And then coronavirus pretty much finished off adult referrals. So, we're now trying to rebound and recover and get those adult referrals going again…It's difficult because most of the halfway houses are still not allowing anybody from the outside."

GRID went one month with zero referrals and one without a single adult referral because their biggest source of adult referrals (halfway houses) was in turmoil as COVID-19 was impacting the Colorado Department of Corrections. Halfway houses are populated by people released from prison, but COVID-19 outbreaks resulted in people not being released in a timely fashion. Halfway houses would often receive as little as a 24-hour notice that someone would not be released to them due to the person being quarantined.

For youth referrals, GRID relied heavily on juvenile probation and Denver's Pre-Trial Release. Those referrals dropped as well. When asked about the drop in referrals, Pam stated:

"My conversation with the supervisor for juvenile probation, because the probation officers had the same problem, they weren't doing referrals during COVID. Now that COVID is done and the courts are starting to open back up, the referrals are going to increase."

Pam was optimistic that referrals would pick up, and as Fig. 2 illustrates, there was a spike during the summer months. However, as the delta variant took hold, referrals dropped again.

The low number of adult referrals reduced adult multidisciplinary team meeting attendance which led GRID to cancel several of them. These cancellations contributed to attenuating interagency relationships with some partners, which proved challenging to recover. Mike told us that he had warned against cancelling the adult meetings as even with no cases to discuss they were vital for interagency relationship maintenance.

5. Discussion

On May 5th, 2021, United States Attorney General Merrick Garland released a statement in which he claimed a multi-pronged approach would be taken to address gang violence, and grants would be available to support such efforts, echoing the Biden Administration's support of community violence intervention. To this end, the Biden Administration called on U.S. Congress to invest $200 million in evidence-based community violence intervention programs (The White House, 2022a). The American Rescue Plan established community violence interventions could receive funds from the $2 billion allocation (The White House, 2022b). Since 2019, the Bureau of Justice Assistance has awarded almost $160 million in grants to implement community violence interventions (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2023). Other agencies, such as the National Institute of Justice and the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, have followed suit. Cities across the United States have established departments and offices devoted to violence reduction (e.g., Oakland, Austin, St. Louis). By the end of the study period, GRID had begun the process to rebrand.6 One major reason was to expand their violence reduction efforts beyond just gangs and set themselves up to be competitive for federal funding. Many of these programs and studies supported by this federal investment will have to navigate the usual challenges of gang and violence intervention, not unlike GRID. And many will be faced with extreme shock of their own, not unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented us with the opportunity to learn about how they operated, made decisions, and carried out their activities while adapting to evolving conditions. Three major points merit further consideration.

First, not all agencies—even those within the criminal justice system—are created and treated equally. Regardless of GRID being house under the Department of Public Safety, it was deemed a non-essential entity at the start of the pandemic. GRID's sole mission is to mitigate violence by addressing gangs. Despite warning city officials, it was ultimately decided GRID was not providing a critical enough service to be granted essential status. Scholars have highlighted that the actions taken by those in decision making positions are often driven by values which in turn shape the strategies that are implemented in a given environment (Dutton, 1986; Dutton, Fahey, & Narayanan, 1983; Ginsberg, 1990; Lachman, Nedd, & Hinings, 1994). A conflict is created when the messages transmitted by leaders are incongruous with their decisions. Argyris and Schon (1974) contended that it is not uncommon to see perpetuated values differ from what is implemented. This was apparent in GRID's case. Denver's mayor has made statements regarding the significance of gang violence and his support for GRID (e.g., Schmelzer, 2019; Takahara, 2020). City officials repeatedly told GRID team members about their support for the program and their desire to learn more about gang intervention. As far as GRID is concerned, these have been hollow words. This perception of how the agency is viewed was bolstered when the emergence of COVID-19 destabilized violence intervention in Denver; non-essential classification was interpreted as GRID being told to “go home” because they—and the gang violence they sought to disrupt—were not important enough. It is critical to reiterate, however, that cities across the United States were operating under immense pressure with limited knowledge, and leaders made the decisions they felt were “right” and that included Denver (Foss, 2020).

Actions can play a pivotal role in the perceptions of line workers and either inspire confidence in leadership or engender cynicism as seen with the GRID team (Schraeder, 2009). Trust is critical in times of disruption, when the general public and organizations look to their leaders for guidance. Saying an agency is critical to the safety of people but consistently failing to provide support can alienate employees. The incongruous messaging has impacted the way the GRID team view their place within the larger network of agencies, feeling they were an afterthought. GRID found itself in a situation not unlike the SOAR Boston program out of Boston, MA which experienced issues with managerial and administrative instability (McDonald, 2022).

A second major observation from this study was the importance of leadership. Leaders guide organizations, implement new ideas, set goals, and manage subordinates (Harborne & Johne, 2003; McDonough III, 2000; Sethi, 2000). The importance of leadership—in GRID's case, a lack thereof—is amplified during times of crisis. Some studies have suggested that leadership during a time of crisis can impact how an organization is perceived and its reputation among stakeholders and partners (e.g., Garcia, 2006; James, Wooten, & Dushek, 2011). In fact, one study highlighted that organizations benefit when their leaders act as spokespeople or advocates for their organizations during times of crisis (Lucero, Kwang, & Pang, 2009). This was salient in our data gathered from the GRID outreach workers. The outreach workers felt that because they lacked stable leadership, they also lacked someone who could advocate for the agency, which directly contributed to their non-essential status. Leaving leadership positions unfilled was a strategic move to comply with mandated budget cuts. While the move aided GRID in achieving their task of reducing their budget, there were unintended consequences. Having the outreach coordinator handle two additional roles (program coordinator and director) and act as the main source of leadership led to contention between them and the rest of the team. The lack of leadership also impacted GRID's relationship with their partnering agencies.

Finally, the pandemic amplified the fragility of interagency relationships. Johnson and colleagues (2003) concluded that commitment, communication, leadership, knowledge of agency culture, resources, turf issues, and pre-planning are seven critical domains to strong interagency collaborating. Our findings are consistent with this research. Interagency relationships can be fragile and require maintenance. As a bigger emphasis is placed on community violence intervention (see: The White House, 2021), which requires interagency cooperation as part of successful implementation, it is critical to remain cognizant that verbal commitments and handshake agreements do not make successful cooperation. The decision makers for these agencies need to put forth a good faith effort into establishing and maintaining working relationships, a challenge regularly documented in gang intervention. A breakdown in leadership could result in the collapse of these relationships which, as GRID learned, can be challenging to restore.

It is possible that the findings of this study may not be generalizable to the experiences of gang intervention organizations in other cities. As is common in qualitative inquiry, this study was limited to a single geographical location within the United States. Other states and cities responded to the pandemic in different ways, so it is possible that our data and findings are unique to Denver. Further research from organizations located in other cities is warranted. It is also possible that people not represented in our data could share a different perspective on the impact of COVID-19 on gang intervention in Denver. While the core of the GRID network was well represented, not all GRID partners were included in our sample. Some representatives from adult serving agencies either refused to participate or ignored our communication attempts. The rapid evolution, including peaks and troughs, of COVID-19 is also important to consider. It is possible that as organizations settle into emerging norms, outputs, and routines, new issues could present a different set of challenges to organizations like GRID. Despite these limitations, there are critical lessons that can be learned.

6. Conclusion

The implications of this study are not limited to the rare event of a global pandemic. We interpreted COVID-19 as system stressor, not unlike natural disasters, social unrest, or economic downturns, which have both immediate and long-term impacts. Community-based gang and violence intervention programs have proliferated in the United States with the infusion of federal support, and GRID's model—while government funded and housed in a government agency—is consistent with non-law enforcement solutions to violence reduction. It is critical for key stakeholders to not only assess the importance of such programs but clearly communicate with the leaders of the program and maintain that communication. This may be especially salient for programs such as GRID, who serve as a bridge between community and government. During times of chaos, it may be prudent to heed the warnings of those who work in the liminal spaces that outreach workers do and allow them to be a part of crisis planning.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Justice (award # 2018-75-CX-0028).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jenn Tostlebe and Kyle Thomas for their feedback on previous drafts of this paper. We also thank the editor and anonymous reviewers.

Footnotes

The comprehensive gang model is known by various names: Comprehensive Community Model, Spergel model, or simply the Comprehensive Model (Gebo, Bond, & Campos, 2015). What is critical is that gangs should be addressed through a multipronged approach of prevention, intervention, and suppression, along with organizational change (Gebo et al., 2015). It was adopted by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, featuring heavily in their outputs concerning gangs and gang programming.

The original Rolling 30s gang originated in Los Angeles. Los Angeles has influenced Denver gangs as people migrated from Los Angeles to Denver. Gangs like Florencia 13, the Crenshaw Mafia Bloods, and Rolling 30s are originally from Los Angeles but can now be found in Denver (Durán, 2013; Rubinstein, 2021).

From June 24th, 2019 to November 30th, 2021 GRID received 237 referrals. Approximately 23% of those referrals were adults and 77% were juveniles. Thirty seven percent of GRID's juvenile referrals came from juvenile probation and Denver Pre-Trial Release. Halfway houses made up over 15% of their referrals making them their biggest source of adult referrals. Other sources, such as Denver Department of Human Services, Denver Public Schools, Denver Department of Public Safety Youth Programs, and Denver PD, will also refer to GRID.

Even though GRID is a Denver agency, living in Denver is not a requirement. A potential client only needs to have significant ties to the city (e.g., works or attends school in Denver). GRID will also accept people who have reported loose gang affiliations, but they are geared towards working with people with higher levels of gang embeddedness such as members of prison gangs classified as STGs, which took on added salience after the 2013 murder of the executive director of Colorado's Department of Corrections by a 211 Crew gang affiliate (Pyrooz, 2022).

Online gang activity, especially on social media, is an emerging body of literature that lends some credence to the belief that online activity can spill out to the streets (e.g., Patton, Pyrooz, Decker, Frey, & Leonard, 2020; Pyrooz, Decker, & Moule, 2015; Storrod & Densley, 2017).

Soon after the current study was ended, GRID was renamed the Office of Community Violence Solutions (OCVS). GRID is now simply the name of the overall network of OCVS and their partners.

References

- Abrams D.S. COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of Public Economics. 2021;194 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahumada R., Stanton S. The Sacramento Bee. 2022, April 6. At least 5 shooters involved in downtown Sacramento shooting, which police called gang-related.https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/crime/article260174710.html [Google Scholar]

- Altheimer I., Duda-Banwar J., Schreck C.J. The impact of Covid-19 on community-based violence interventions. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;45(4):810–819. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09547-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell C., Boin A., t’Hart, P. The Oxford handbook of political leadership. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2014. Political leadership in times of crisis; pp. 418–433. [Google Scholar]

- Arbreton A.J., McClanahan W.S. Public/Private Ventures; 2002. Targeted outreach: Boys & girls clubs of America’s approach to gang prevention and intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris C., Schon D.A. Jossey-bass; 1974. Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R., Flint J. Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update. 2001;33(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki P., Waldorf D. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research. 1981;10(2):141–163. doi: 10.1177/004912418101000205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L. The Gangs All Here. Westword. 2004, June 3. https://www.westword.com/news/the-gangs-all-here-5079588

- Brantingham P.J., Tita G., Herz D. The impact of the City of Los Angeles Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) comprehensive strategy on crime in the City of Los Angeles. Justice Evaluation Journal. 2021;1–20 doi: 10.1080/24751979.2021.1887709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown F. The Denver Post. 2007, July 12. Gang fear lurks in shadows.https://www.denverpost.com/2007/07/12/gang-fear-lurks-in-shadows/ [Google Scholar]

- Brunson R.K., Braga A.A., Hureau D.M., Pegram K. We Trust You, But Not That Much: Examining Police–Black Clergy Partnerships to Reduce Youth Violence. Justice Quarterly. 2015;32(6):1006–1036. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2013.868505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Assistance Past funding. Bureau of Justice Assistance. 2023. https://bja.ojp.gov/funding/expired Retrieved December 13, 2022, from.

- Cahill M., Jannetta J., Tiry E., Lowry S., Becker-Cohen M., Paddock E., Serakos M. 2015. Evaluation of the Los Angeles gang reduction and youth development program: Year; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T. Violence prevention and targeting the elusive gang member. Law and Society Review. 2017;51(1):42–69. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T. Recruitment through rule breaking: Establishing social ties with gang members. City & Community. 2018;17(1):150–169. doi: 10.1111/cico.12272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decker S.H., Curry D.G. Rational choice and criminal behavior: Recent research and future challenges. Routledge; 2002. I’m down for my organization: The rationality of responses to delinquency, youth crime and gangs. [Google Scholar]

- Decker S.H., Bynum T.S., McDevitt J., Farrell A., Varano S.P. Street outreach workers. Best Practices and Lessons Learned. 2008;24 [Google Scholar]

- Durán R. 1st ed. Columbia University Press; 2013. Gang life in two cities: An insider’s journey. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E. The processing of crisis and non-crisis strategic issues. Journal of Management Studies. 1986;23(5):501–517. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Fahey L., Narayanan V.K. Toward understanding strategic issue diagnosis. Strategic Management Journal. 1983;4(4):307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin S., Robin L., Cramer L., Thompson P., Martinez R., Jannetta J. Group, and gang violence interventions. Urban Institute; 2022. Implementing youth violence reduction strategies: Findings from a scan of youth gun; pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- FBI Reported UCR Part I Offenses. 2019. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZTg4NzFiMDAtMzM2Ny00YTdiLTg3NDUtNTlkYWQ4MjkyYmQyIiwidCI6IjFkYzNlZmNmLTVlMTQtNGRkNS1iMjE3LWE3NTBjNWIxMzIyZCIsImMiOjN9

- Foss N.J. Behavioral strategy and the COVID-19 disruption. Journal of Management. 2020;46(8):1322–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia H.F. Effective leadership response to crisis. Strategy & Leadership. 2006;34(1):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison R. Denver 7 Colorado news (KMGH) 2021, March 9. CBI report shows crime in Colorado is on the rise amid the pandemic.https://www.denver7.com/news/crime/cbi-report-shows-crime-in-colorado-is-on-the-rise-amid-the-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- Gebo E., Bond B.J., Campos K.S. The OJJDP comprehensive gang strategy. The Handbook of Gangs. 2015:392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg A. Connecting diversification to performance: A sociocognitive approach. Academy of Management Review. 1990;15(3):514–535. [Google Scholar]

- Gobo G., Marciniak L.T. Ethnography. Qualitative Research. 2011;3(15–34) [Google Scholar]

- Gravel J., Bouchard M., Descormiers K., Wong J.S., Morselli C. Keeping promises: A systematic review and a new classification of gang control strategies. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2013;41(4):228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne P., Johne A. Creating a project climate for successful product innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management. 2003;6(2):118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hureau D., Wilson T., Jackl H., Arthur J., Patterson C., Papachristos A. 2022. Exposure to gun violence among the population of Chicago community violence interventionists. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James E.H., Wooten L.P., Dushek K. Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Academy of Management Annals. 2011;5(1):455–493. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. The New York Times; 1993, December 11. 2 of 3 young black men in Denver listed by police as suspected gangsters.https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/11/us/2-of-3-young-black-men-in-denver-listed-by-police-as-suspected-gangsters.html [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.J., Zorn D., Tam B.K.Y., Lamontagne M., Johnson S.A. Stakeholders’ views of factors that impact successful interagency collaboration. Exceptional Children. 2003;69(2):195–209. doi: 10.1177/001440290306900205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- KDVR . FOX31 Denver. 2020, March 26. These businesses are considered ‘essential’ during Colorado’s stay-at-home order.https://kdvr.com/news/coronavirus/these-businesses-are-considered-essential-during-colorados-stay-at-home-order/ [Google Scholar]

- Klein M.W. Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs; NJ: 1971. Street gangs and street workers. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman R., Nedd A., Hinings B. Analyzing cross-national management and organizations: A theoretical framework. Management Science. 1994;40(1):40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Aguado P. Working between two worlds: Gang intervention and street liminality. Ethnography. 2013;14(2):186–206. doi: 10.1177/1466138112457310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero M., Kwang A.T.T., Pang A. Crisis leadership: When should the CEO step up? Corporate Communications. An International Journal. 2009;14(3):234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Maxson C.L., Curry G.D., Howell J.C. In: Responding to gangs: Evaluation and research (p. 107) Reed W.L., Decker S.H., editors. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of; 2002. Youth gang homicides. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D. Boston Globe; 2022, June 16. ‘They’re not doing anything’: Boston’s gang intervention program is in disarray, sources say - the Boston globe.https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/06/16/metro/theyre-not-doing-anything-bostons-gang-intervention-program-is-disarray-sources-say/ [Google Scholar]

- McDonough E.F., III Investigation of factors contributing to the success of cross-functional teams. Journal of Product Innovation Management: An International Publication of the Product Development & Management Association. 2000;17(3):221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.M., Blumstein A. Crime, justice & the COVID-19 pandemic: Toward a National Research Agenda. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;45(4):515–524. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09555-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., Short M.B., Sledge D., Tita G.E.…Brantingham P.J. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson K.R., Zhang Y., Ingram J.R. The impact of COVID-19 on police officer activities. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2022.101943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix J., Ivanov S., Pickett J.T. What does the public want police to do during pandemics? A national experiment. Criminology & Public Policy. 2021;20(3):545–571. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novisky M.A., Narvey C.S., Semenza D.C. Institutional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in American prisons. Victims & Offenders. 2020;15(7–8):1244–1261. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2020.1825582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos A.V. Too big to fail: The science and politics of violence prevention. Criminology & Public Policy. 2011;10(4):1053–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00774.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D.U., Pyrooz D., Decker S., Frey W.R., Leonard P. When twitter fingers turn to trigger fingers: A qualitative study of social media-related gang violence. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. 2020;2(2):160. doi: 10.1007/s42380-019-00020-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R. The policy lessons learned from the criminal justice system response to COVID-19. Criminology & Public Policy. 2021;20(3):385–399. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrooz D., Weltman E., Sanchez J. Intervening in the Lives of Gang Members in Denver: A Pilot Evaluation of the Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver. Justice Evaluation Journal. 2019;2(2):139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrooz D.C. The prison and the gang. Crime and Justice. 2022;000–000 doi: 10.1086/720944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrooz D.C., Decker S.H., Moule R.K. Criminal and routine activities in online settings: Gangs, offenders, and the internet. Justice Quarterly. 2015;32(3):471–499. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2013.778326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrooz D.C., Labrecque R.M., Tostlebe J.J., Useem B. Views on COVID-19 from inside prison: Perspectives of high-security prisoners. Justice Evaluation Journal. 2020;1–13 doi: 10.1080/24751979.2020.1777578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rector K., Santa Cruz N. Los Angeles Times; 2020, October 29. L.A.’s surge in homicides fueled by gang violence, killings of homeless people.https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-10-29/gangs-homelessness-cited-in-lapd-report-on-surge-in-killings [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Santoso K., Hyde D., Bertozzi A.L., Brantingham P.J. The pandemic did not interrupt LA’s violence interrupters. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. 2022 doi: 10.1108/JACPR-10-2022-0745. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Sage Publications Limited; 2020. Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein J. 1st ed. Picador; 2021. The Holly: Five bullets, one gun, and the struggle to save an American neighborhood. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer E. The Denver Post; 2019, October 20. Turf, ego and dollars: Denver anti-gang activists rethink strategy as new “hybrid gangs” form.https://www.denverpost.com/2019/10/20/denver-hybrid-gangs-teen-gun-violence/ [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer E. The Denver Post; 2021, January 31. Denver’s 2020 homicide numbers highest in city since 1981 as police, communities navigate “state of normlessness.”.https://www.denverpost.com/2021/01/31/denver-2020-crime-homicides/ [Google Scholar]

- Schraeder M. Incongruence in the value of employees: Organizational actions speak louder than words. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal. 2009;23(2):4–5. doi: 10.1108/14777280910933702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi R. New product quality and product development teams. Journal of Marketing. 2000;64(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel I.A. Altamira Press; 2007. Reducing youth gang violence: The little village gang project in Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel I.A., Sosa R.V., Wa K.M. School of Social Service Administration, University of Chicago; 2004. Evaluation of the Tucson comprehensive community-wide approach to gang prevention, intervention and suppression program. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel I.A., Wa K.M., Sosa R. Vol. 231. 2005. Evaluation of the San Antonio comprehensive community-wide approach to gang prevention, intervention and suppression Program. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel I.A., Wa K.M., Sosa R.V. 2005. Evaluation of the Riverside comprehensive community-wide approach to gang prevention, intervention and suppression. Unpublished Report. Retrieved on August, 17, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Storrod M.L., Densley J.A. ‘Going viral’ and ‘going country’: The expressive and instrumental activities of street gangs on social media. Journal of Youth Studies. 2017;20(6):677–696. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1260694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara D. FOX31 Denver; 2020, July 14. Mayor Hancock ‘sounds the alarm’ on youth violence in Denver.https://kdvr.com/news/mayor-hancock-sounds-the-alarm-on-youth-violence-in-denver/ [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury R. Qualitative versus quantitative methods: Understanding why qualitative methods are superior for criminology and criminal justice. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology. 2009;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- The White House FACT SHEET: More details on the Biden-Harris Administration's Investments in Community Violence Interventions. 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/07/fact-sheet-more-details-on-the-biden-harris-administrations-investments-in-community-violence-interventions/

- The White House . The White House; 2022, February 3. President Biden announces more actions to reduce gun crime and calls on congress to fund community policing and community violence intervention.https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/02/03/president-biden-announces-more-actions-to-reduce-gun-crime-and-calls-on-congress-to-fund-community-policing-and-community-violence-intervention/ [Google Scholar]