Abstract

COVID-19 is associated with a range of sequelae, including cognitive dysfunctions as long-standing symptoms. Considering that the number of people infected worldwide keeps growing, it is important to understand specific domains of impairments to further organize appropriate rehabilitation procedures. In this study we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate specific cognitive functions impacted by COVID-19. A literature search was conducted in Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Academic Search Premier, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, and preprint databases (OSF and PsyArXiv via OSF Preprints, medRxiv, bioRxiv, Research Square). We included the studies that compared cognitive functioning in COVID-19 reconvalescents and healthy controls, and used at least one validated neuropsychological test. Our findings show that short-term memory in the verbal domain, and possibly, visual short-term memory and attention, are at risk in COVID-19 reconvalescents. The impact of COVID-19 on cognitive functioning has yet to be studied in detail. In the future more controlled studies with validated computerized tests might help deepen our understanding of the issue.

PsycINFO classification

3360 Health Psychology & Medicine

Keywords: COVID-19 sequelae, Cognitive functions, Short-term memory, Long-term memory, Visual-spatial attention, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Post COVID-19 condition refers to novel symptoms arising after COVID-19 and lasting for at least 12 weeks (Nalbandian et al., 2021). Headaches, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and cognitive deficits (also dubbed ‘brain fog’) are among the most common COVID-19 sequelae (Ellul et al., 2020; Soriano et al., 2021). Systematic reviews of neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19 estimate the prevalence of objective cognitive dysfunction at 20.2 % (Badenoch et al., 2021) and subjective cognitive dysfunction (such as difficulty concentrating) at 23.8 % (Groff et al., 2021). A large-scale cohort study of electronic health records has shown a lower prevalence of cognitive difficulties (7.88 %), however, this study only included patients whose symptoms were severe enough to require medical attention (Taquet et al., 2021).

Cognitive deficits, along with fatigue, have a negative impact on the quality of life. Up to half of the respondents who experience ‘brain fog’ after COVID-19 report that they are unable to work full-time like they used to (Davis et al., 2021). A common theme of patients' self-reports is their inability to carry out basic everyday tasks, they find it difficult to be physically and mentally active, and experience these changes as identity-changing (van Kessel et al., 2022). Up to 47.4 % of patients are not able to return to work, and in among ICU survivors this metric reaches a striking 90 % (Ceban et al., 2022).

Several hypotheses on reasons for cognitive dysfunction have emerged and evidence on the matter seems conflicted (Stracciari et al., 2021). On the one hand, cognitive impairments have a number of medical reasons, such as inflammation (Pandharipande et al., 2013), neuroinflammation and cytokine storm (Alnefeesi et al., 2021; Rengel et al., 2019), critical care, and sedation (Desai et al., 2011; Frontera, 2011; Porhomayon et al., 2016). On the other hand, self-reported cognitive complaints after COVID-19 are associated with anxiety and depression (Gouraud et al., 2021), both of which are considerably increased both in the general population (Cénat et al., 2021; Salari et al., 2020) and in COVID-19 patients, especially with pre-existing conditions (Luo et al., 2020). COVID-19-specific mechanisms of cognitive deficits could also be hypothesized, given that its neurological complications manifest in small diffuse lesions in cortical and subcortical regions (Ghannam et al., 2020).

While systematic reviews focusing on cognitive dysfunctions after COVID-19 are starting to appear, most of them do not collect enough data for performing a meta-analysis. Existing systematic reviews focus on the prevalence of symptoms reported by the patients (Groff et al., 2021; van Kessel et al., 2022) and investigate the association of cognitive complaints with illness severity, hospitalization status and time since symptom onset (Badenoch et al., 2021), proinflammatory markers (Alnefeesi et al., 2021; Ceban et al., 2022), functional impairment, including decreased activity and employment problems (Ceban et al., 2022). Some reviews point out specific domains of cognitive dysfunction, such as working memory, attention, and episodic memory (Bertuccelli et al., 2022; Biagianti et al., 2022; Crivelli et al., 2022; Tavares-Júnior et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022). The only meta-analysis we've discovered compares post-COVID patients' and healthy controls' performance on Montreal Cognitive Assessment that measures overall cognitive impairment (Crivelli et al., 2022). However, no study to date has synthesized the assessments of particular cognitive domains (long-term memory, short-term memory, working memory, attention, etc.) with second-level neuropsychological tests. According to Biagianti et al. (2022) these tests can be useful in detecting subtle cognitive changes in domain-specific functions when global screening provides little information.

This warrants further research, focusing solely on deficits in individual cognitive functions after COVID-19, their types and possible causes. The current systematic review raises the following question: what cognitive functions are impaired in people reconvalescent from COVID-19 in comparison to healthy controls?

2. Materials and methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The protocol of the review was registered on PROSPERO, registration no. CRD42021288003.

2.1. Search and selection

2.1.1. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they compared individual cognitive functions of people reconvalescent from COVID-19 and healthy controls as measured by second-level neuropsychological tests. Exclusion criteria were: (1) presence of psychiatric or neurological comorbidities in either sample (such as dementia); (2) designs utilizing only screening measures of overall cognitive dysfunction (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment), self-report measures and patient complaints. Thus, we included only papers that used at least one validated test to measure cognitive functioning. We only included studies in English.

2.1.2. Information sources

We searched citation databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Academic Search Premier and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition) and preprint databases (OSF and PsyArXiv via OSF Preprints, medRxiv, bioRxiv, Research Square). Initial searches were conducted on October 27, 2021; searches in citation databases were repeated on November 1 and in preprint databases – on November 9.

2.1.3. Search strategy

To identify studies that met our criteria we implemented the following search strategy. Searches included keywords related to COVID-19, cognitive and neurocognitive functioning and impairments, and brain fog. The keywords were identified either on the basis of prior studies on the topic of cognitive impairments in cancer survivors (Dijkshoorn et al., 2021; Hodgson et al., 2013; Ono et al., 2015) and HIV-positive individuals (Deng et al., 2021; Fialho et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2016), or in an automated retrieval of words placed after ‘cognitive’ in the first 4000 titles and abstracts loaded from Web of Science. Search strategies are listed in Suppl.1. Language was limited to English in web interfaces of the citation databases. The search was restricted to the studies published from 2019. Given that preprint databases have more limited search engines, search strategy in Research Square, medRxiv and bioRxiv was simplified to include only papers related to COVID-19 and ‘cognitive’.

2.1.4. Paper selection

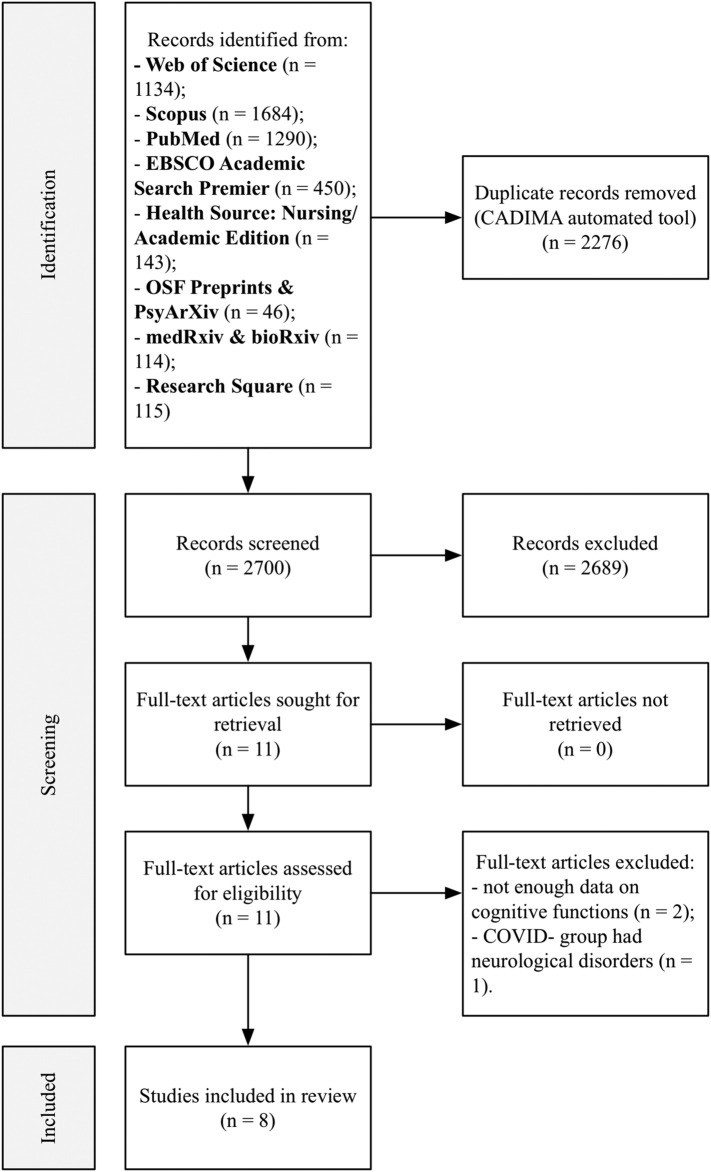

Citations were imported into CADIMA tool for systematic reviews (Kohl et al., 2018) for automated duplicate removal by title and screening. Titles and abstracts were screened by three reviewers (PM, AKh and AR) independently. PRISMA flowchart depicting the results of the selection process is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study identification and selection.

2.1.5. Data collection

The following information was extracted from the studies: sample characteristics (n, % of women, age, number of days since the onset of symptoms), study design, cognitive measures (cognitive functions they measure, stimuli modality, scores for COVID+ and control groups). Data extraction was conducted by three reviewers (AR, PM and AKh). Three studies (Hampshire et al., 2021; Woo et al., 2020; Wild et al., 2021) did not present cognitive testing data for either post-COVID sample or healthy controls. We made an attempt to contact corresponding authors in order to get the missing data. Only one author replied and provided required information (Wild et al., 2021), thereby two studies (Hampshire et al., 2021; Woo et al., 2020) were excluded from analysis due to the lack of data.

2.2. Analytic strategy

2.2.1. Outcomes and measures

The main outcomes were scores of cognitive functioning (memory, attention). The measures are described in detail in Table 1 . Given the small number of studies and a large variety of tests and scores used to assess cognitive functions we categorized them according to a specific function measured by the test (such as short-term memory, working memory, long-term memory, attention), stimulus type (visual-spatial or verbal) and score type (accuracy / number of correct answers or reaction time).

Table 1.

Measures used in the selected studies.

| Function and modality | Measure | Authors | Scores | Test description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Short-term memory – verbal | 1.1. Word List Recognition Memory Test | Guo et al. | % correct*, RT**, d' | Participants are presented with a small list of words and instructed to memorize as many of the words in the list as possible. In the second presentation, old stimuli are mixed with the new ones. Participants try to recognize familiar words. |

| 1.2. California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) – Immediate recall | Mattioli et al. | % correct* | The task includes 16 words and requires participants to recall the list over five trials. | |

| 1.3. Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry Danish Version – Verbal learning test | Miskowiak et al. | % correct* | The verbal learning test includes three subtests. Participants study lists of 10 words with immediate feedback after each presentation of the list. | |

| 1.4. Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia –Verbal memory test | Poletti et al. | % correct* | Participants are presented with a set of words and then asked to recall as many as possible. | |

| 1.5. Word memory – Immediate memory test | Zhao et al. | mean accuracy*, RT** | The same as Word List Recognition Memory Test (1.1). | |

| 2. Short-term memory – visual-spatial | 2.1. Pictorial Associative Memory Test | Guo et al. | % correct*, RT** | Participants memorize a series of several pairs of items of different categories. Each pair is presented on the screen for a short time. After that, participants are presented with one item from the first category and several items from the second category. The task is to choose the right pair from the proposed options. |

| 2.2. Rey figure copy (Rey–Osterrieth complex figure test) Immediate recall | Mattioli et al. | % correct* | Participants copy a complex geometric shape, and then reproduce it from memory. | |

| 2.3. Object memory – Immediate memory test | Zhao et al. | % correct*, RT** | Participants compare numbers presented sequentially. If the current number coincides with the number just presented, they have to press a key. | |

| 2.4. Paired associates | Wild et al. | % correct* | The testing was administered via the Cambridge Brain Sciences platform (https://www.cambridgebrainsciences.com/science/tasks/digit-span). Paired associations (PA) are an assessment of associative and episodic memory. Participants are presented with a set of pairs of words that they should try to remember. After that, they are presented with single words, and asked to remember and reproduce the word associated with the presented one. | |

| 2.5. Continuous Performance Test Part 3 | Zhou et al. | no. of correct*, error, missing, RT** | The test is administered on an iPad and consists of three progressively more complex parts. In part 3 three animal pictures are displayed, and participants decide if they are similar to the previously displayed combination of pictures. | |

| 3. Short-term memory – spatial span | 3.1, Spatial short-term memory capacity – Spatial span | Zhao et al. | maximum sequence length correctly recalled* | Participants are presented with a grid of boxes on the screen. Individual cells light up in a certain sequence. Participants have to memorize this sequence and click on the corresponding cells in the right order. Each new sequence is one unit longer than the previous one. Performance is determined by the average number of boxes remembered during the task. |

| 3.2. Spatial span | Wild et al. | maximum sequence length correctly recalled* | The same as spatial short-term memory capacity (3.1). | |

| 4. Long-term memory – verbal | 4.1. California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) Delayed recall | Mattioli et al. | % correct* | Delayed recall version of 1.2. |

| 4.2. Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry Danish Version – Verbal Learning Test – Delayed recall | Miskowiak et al. | no. of correct words* | Delayed recall version of 1.3. | |

| 4.3. Word memory – Delayed memory test | Zhao et al. | mean accuracy* | The participants are required to memorize a sequence of words randomly drawn from three different categories. | |

| 5. Long-term memory – visual | 5.1. Rey figure copy (Rey–Osterrieth complex figure test) Delayed recall | Mattioli et al. | % correct* | Delayed recall version of 2.2. |

| 2.3. Object memory – Delayed memory test | Zhao et al. | % correct*, RT | Delayed recall version of 2.3. | |

| 6. Working memory | 6.1. 2D Mental Rotation Test – % Correct | Guo et al. | % correct*; RT | The test measures the ability to spatially rotate objects in the mind. Participants identify which one of the presented objects is the same as the target object but rotated by 90, 180 or 270 degrees. |

| 6.2. Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry Danish Version – Working memory test | Miskowiak et al | no. of letters recalled* | The task consists of eight trials of recalling three consonants, which are distributed among four conditions: no delay, delays of 3, 9, or 18-s. | |

| 6.3. Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia – Working memory | Poletti et al. | no. of correct responses* | Participants are presented with sets of numbers. The length of numbers increases each time. They are asked to say the numbers from lowest to highest. | |

| 6.4. Digital Span Test | Zhou et al. | the average no. of digits correctly remembered* | The test assesses concentration, instantaneous memory, and resistance to information interference. The participants are presented with a sequence of numbers and are asked to repeat the presented numbers in the same order or in the reverse order. | |

| 6.5. Digit span | Wild et al. | max. Correct sequence* | Participants are presented with a sequence of digits, one at a time and asked to repeat the sequence by entering the numbers from the keyboard. | |

| 6.6. Monkey ladder | Wild et al. | max. Correct sequence** | Participants click on boxes searching for a hidden token. Clicking on the same box ends the trial. | |

| 6.7. Token search | Wild et al. | max. Correct sequence** | Participants memorize a grid with numbers and click on them in the ascending order after they are hidden. | |

| 7. Attention – visual-spatial | 7.1. Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia – Attention and speed of information processing | Poletti et al. | no. of correct numbers* | Participants write numbers from 1 to 9 to match the symbols on a response sheet for 90 s. |

| 7.2. Spatial visual attention – Target detection | Zhao et al. | total no. of identified target shapes* | Participants are presented with targets and distractor shapes; their task is to identify targets. | |

| 7.3. Feature match | Wild et al. | no. of correct responses* | There are two fields containing different abstract shapes. The participant is asked to determine if the presented fields are identical or not. The task consists of identifying and clicking on a target shape presented among distractors. | |

| 7.4. Sign Coding Test | Zhou et al. | no. of correct responses* | Similar to Symbol coding tasks (7.1.). Performed on an iPad with a 90 s. time constraint. | |

| 8. Attention – visual-spatial – RTs | 8.1. TEA attention test (Italian for TAP – Test of Attentional Performance) | Mattioli et al | RT* | Participants are tasked with pressing a key as soon as a stimulus appears or pressing a key after a certain cue. |

| 8.2. Attention Network Test – Incongruent No cue Trials | Lamontagne et al. | RT in no cue trials* | Participants are presented with a spatial cue, followed by five arrows in either top or bottom of the screen. Their task is to indicate the direction of the third arrow. |

Note: * – scores pooled in meta-analysis; ** – scores included in sub-analyses; RT – reaction time; no. – number.

2.2.2. Quality assessment

To assess the quality of individual studies we used the Johanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies (Moola et al., 2020). While originally we planned to use the JBI Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool, we decided against it, as we had no studies of prevalence, and most of the studies we selected were cross-sectional. The papers were assessed by three reviewers (PM, AKh, and AR) independently; the consensus was reached in a group discussion.

2.2.3. Data analysis

The data was analyzed in R 3.6.3 using packages meta ver. 4.19-2 (Balduzzi et al., 2019), dmetar ver. 0.0.9 (Harrer et al., 2019) and metafor ver. 3.0-2 (Viechtbauer, 2010). Random-effects models with standardized mean differences (Cohen's d) and Hartung-Knapp adjustment were used due to significant heterogeneity in the methods, scores and participant characteristics in the studies. The models were run for each group of cognitive tests indicated in the section above. Forest plots were used to visualize effects from the studies grouped by cognitive function and modality. Heterogeneity was assessed by I2. It was decided that Q wouldn't have enough statistical power (due to a small number of studies yielded by the search). Sensitivity leave-one-out analysis was run for models with no less 5 studies.

The models were used on raw means and standard deviations (SDs) that were extracted from study results or converted from other values where necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and characteristics

We included 8 studies in our analysis; 5 published papers and 3 non-peer-reviewed preprints. The characteristics of the studies are listed in Table 2 . Given the novelty of the field, as we expected, no controlled trials could be found. Most studies were uncontrolled and observational in nature (6 studies were cross-sectional, among them 1 study was planned as a longitudinal one, and 2 recruited COVID-19 groups utilizing prospective cohort design).

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Design | Location | Demographic characteristics |

COVID characteristics |

Outcome measures |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls |

Post-COVID group |

|||||||||||||

| n | nF | Age | Edu | n | nF | Age | Edu | Time elapsed | Severity | Memory | Attention | |||

| Guo et al., 2021* | Cross-sectional | UK 137 + 130; North America 24 + 33 | 185 | 118 | [18–61+] | 28.2 % PSE | 181 | 130 | [18–61+] | 63 % PSE | 3–31+ weeks | NA | Word List Recognition Memory Test; Pictorial Associative Memory Test; 2D Mental Rotation Test |

– |

| Lamontagne et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Canada 11 + 35; USA 39 + 15 | 50 | 35 | 29.14 ± 9.87 [20–53] | 15.54 ± 2.93 | 50 | 29 | 30.8 ± 7.79 [19–60] | 16.12 ± 2.95 | 14–312 days | 4 % asymptomatic; 52.1 % moderate cases; 2 % hospitalized | – | Attentional Network Test |

| Mattioli et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Italy | 30 | 22 | 45.73 [23–62] | 18 [8–18] | 120 | 90 | 47.86 [26–65] | 16 [8–18] | 12–215 days (mean − 125.92 days) | 118 mild-moderate; 2 in ICU | California Verbal Learning Test; Rey figure copy and recall | TEA attention test |

| Miskowiak et al., 2021 | Prospec-tive cohort | Denmark | 100 | 59 | 56 ± 6.9 | 14.3 ± 3 | 29 | 12 | 56.2 ± 10.6 | 14.3 ± 3.9 | 3–4 months | 100 % hospitalized patients | SCIP-D Verbal learning Test & Working memory Test | – |

| Poletti et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Italy | 165 | 72 | 40.57 ± 11.79 | 13.45 ± 3.79 | 312 | 17 | 52.63 ± 8.81 | 12.94 ± 3.76 | 1, 3, 6 months | 86 % hospitalized; 4 % of them in ICU | BACS Verbal memory & Working memory | BACS Attention test |

| Wild et al., 2021* | Prospec-tive cohort | NA | 7832 | 5539 | 42.76 ± 14.44 | 75.61 % PSE | 478 | 341 | 43.41 ± 13.17 | 82.47 % post-sec | 3 ± 2 months | 15 asymptomatic; 403 mild COVID; 67 hospitalized, 17 in ICU | Spatial Span; Monkey Ladder; Paired Associates; Token Search; Digit Span |

Feature Match |

| Zhao et al., 2021* | Cross-sectional | NA | 46 | 24 | 25.03 ± 7.33 | NA | 36 | 25 | 27.71 ± 8.51 | NA | 167.3 ± 127.9 days | 100 % mild cases, no hospitalization | Object episodic memory; Word memory; Spatial Span | Target detection |

| Zhou et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 29 | 17 | 42.48 ± 6.94 | 12.38 ± 3.14 | 29 | 11 | 47 ± 10.54 [30–64] | 12.59 ± 2.78 | 2–3 weeks | NA | Continuous Performance Test; Digital Span Test | Sign Coding Test |

Note: * – non-peer-reviewed preprint; nF – number of women; Edu – education in years or % of sample with a degree; PSE – post-secondary education; NA – information not available; STM – short-term memory; LTM – long-term memory; WM – working memory; BACS – Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; SCIP-D – Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry Danish Version. Data format – mean ± SD [range].

The overall sample included 9672 participants (6541 women, 68 %) aged 18–65 (mean age across studies in post-COVID group – 43.66; in control group – 40.24); among them 1235 participants reconvalescent from COVID-19 and 8437 healthy controls. The participants were from the UK and Ireland (n = 267, 3 %), USA and Canada (n = 157, 2 %), Italy (n = 627, 6 %), Denmark (n = 129, 1 %), and China (n = 54, 0.6 %). Out of 4 studies that recruited participants online (Guo et al., 2021; Lamontagne et al., 2021; Wild et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021) two (combined n = 8392) didn't report their location (Wild et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). Control groups were recruited online or in hospitals (among COVID-negative health-care workers and patients) except for two studies (Poletti et al., 2021; Wild et al., 2021) that used pre-pandemic data.

Time after the initial symptom onset or hospitalization for post-COVID groups ranged between 3 and 44 weeks. COVID-19 severity was reported in 6 studies and encompassed 17 asymptomatic, 245 mild-moderate non-hospitalized outpatients (and those who didn't require medical attention at all), and 367 hospitalized cases including those who needed ICU and/or ventilation (n = 29). Guo et al. (2021) grouped post-COVID participants according to the severity of their symptoms: 42 participants reported full recovery, 53 had prolonged mild symptoms and 66 experienced severe symptoms.

Means and standard deviations for cognitive ability tests were presented in all studies except for Lamontagne et al., 2021 and Mattioli et al., 2021. Lamontagne et al., 2021 utilized means and standard errors that were converted to standard deviations (standard error multiplied by square root of n). Mattioli et al., 2021 presented the results as medians and ranges; to convert these we used formulas from Hozo et al. (2005).

The paper by Miskowiak et al., 2021 contained a misprint in the mean for working memory in control group (1.9 vs. 18.2 in post-COVID group and 19.9 expected score). The mean was computed using the provided Cohen's d.

Given that several studies (Guo et al., 2021; Lamontagne et al., 2021) included participants with acute COVID (n = 20 and 18 respectively), we excluded them and recalculated the means and standard deviations from the remaining groups using the StatTools online calculator (Chang & Sahota, n.d.).

3.2. Study quality

To assess the quality of individual studies we used the Johanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies (Moola et al., 2020). While originally we planned to use the JBI Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool, we decided against it, as we had no studies of prevalence, and most of the studies we selected were cross-sectional. Item 3 (“Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?”) was not relevant in our case, as the studies had no exposure. The results of the quality check are presented in Table 3 . As the JBI tools do not have cut-off values, we used both numeric scales to indicate the quality of the study (7 being the maximum attainable number). 3 studies showed excellent quality (100 % positive checks), and 5 studies had fair quality (sum score on the ratings 5.5–6.5 or 92–93 % given that some items were inapplicable to all studies). Methodological concerns included a small sample size, a large disparity between groups and recruitment of specific professional groups (health-care workers). All studies used objective tests. In case of Zhao et al. several tests designed close to western analogues were supposed to measure different functions (e.g., attention test was close to a typical simple span task), so they were included in the groups according to their described methodology rather than intended use.

Table 3.

Study quality assessment.

| Studies | 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | 5. Were confounding factors identified? | 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Total score / Mean score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo et al., 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6.5 / 93 % |

| Lamontagne et al., 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | 6 / 100 % |

| Mattioli et al., 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Unsure | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | 5.5 / 92 % |

| Miskowiak et al., 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | 6 / 100 % |

| Poletti et al., 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 / 100 % |

| Wild et al., 2021 | Yes | Unsure | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6.5 / 93 % |

| Zhao et al., 2021 | Yes | Unsure | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6.5 / 93 % |

| Zhou et al., 2020 | Yes | Unsure | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | 5.5 / 92 % |

Notes: % = Total score / Number of applicable items * 100 %.

3.3. Results of individual studies

Study statistics (means and standard deviations for cognitive test scores in post-COVID and healthy control groups) and corresponding effect sizes (Cohen's d, standard error and confidence interval) are listed in Suppl. 2.

3.4. Data synthesis results

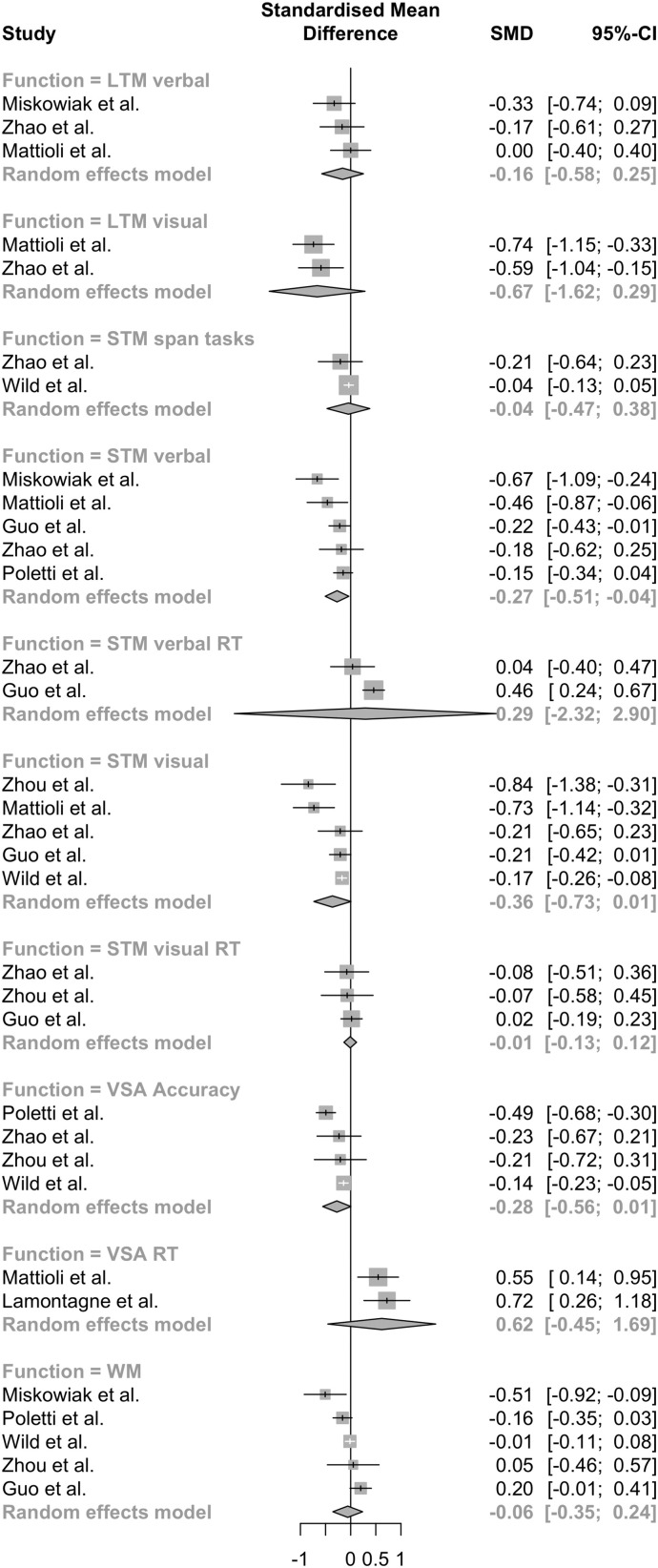

Given the small amount of studies and the large number of and disparity between measures we conducted a series of random-effects models for each domain and type of measure. The overall result is shown on a forest plot (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for all random effects models: STM – short-term memory, LTM – long-term memory, WM – working memory, VSA – visual-spatial attention, RT – reaction times.

3.4.1. Verbal short-term memory

Results from five studies (Guo et al., 2021; Mattioli et al., 2021; Miskowiak et al., 2021; Poletti et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021) were pooled (n = 1204). There were significant differences in verbal short-term memory scores between post-COVID and control groups (d = −0.27, 95 % CI – [−0.513; −0.020], t = −3.00, p = 0.04). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 36.5 %; 95 % CI – [0 %; 76.3 %]).

Egger's test did not indicate funnel plot asymmetry (I = −2.406; [−4.74; −0.07] t = −2.019, p = 0.137 (Suppl. 3a). Sensitivity leave-one-out analysis showed that changes in effect sizes ranged from −0.34 to −0.20; the study by Poletti et al. contributed the most to effect sizes, and the study by Miskowiak et al. was the main source of heterogeneity (Suppl. 4).

We also pooled effects from measures of reaction times in verbal short-memory tasks. There were only two studies (Guo et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021) with such scores (n = 426). The differences were insignificant (d = 0.29, 95 % CI – [−2.3192; 2.9035], t = 1.42, p = 0.390). Heterogeneity was moderate to high (I2 = 65.2 %, 95 % CI – [0 %; 92.1 %]).

3.4.2. Visual short-term memory

Results from five studies (Guo et al., 2021; Mattioli et al., 2021; Wild et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020) were pooled (n = 8944). The differences between groups were close to significance levels (d = −0.37, 95 % CI – [−0.743; 0.001], t = −2.77, p = 0.05). Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 67.3 %; 95 % CI – [15.4 %; 87.4 %]).

Egger's test showed no funnel plot asymmetry (intercept – -2.084, 95 % CI – [−3.83; −0.34], t = −2.34, p = 0.101) (Suppl. 3b). Sensitivity analysis showed that changes in effect sizes ranged from −0.454 to −0.196. Removing Wild et al. provided the biggest impact on effect size. Matiolli et al. and Zhou et al. were the largest sources of heterogeneity (Suppl. 5).

Three studies (Guo et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020) also provided reaction time scores (n = 484). The differences were not significant (d = −0.009, 95 % CI – [−0.136; 0.118], t = −0.31, p = 0.783). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0 %, 95 % CI – [0 %; 89.6 %]).

Two studies used number span tests in addition to object-related tasks (Wild et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). We did not include them in the overall model (because of a dissimilarity between them and other visual memory tasks that implied operations with shapes), but tested them as a part of certainty checks. Including span tasks lessened the effect size (d = −0.35, 95 % CI – [−0.779; 0.075], t = −2.29, p = 0.08) and raised heterogeneity (I2 = 79.7 %). Span measures on their own (k = 2; n = 8392) did not yield significant effects either (d = −0.05, 95 % CI – [−0.476; 0.385], t = −1.33, p = 0.41).

3.4.3. Long-term memory

Verbal long-term memory scores were pooled from three studies (Mattioli et al., 2021; Miskowiak et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021; n = 361). The differences between groups were not significant (d = −0.16, 95 % CI – [−0.579; 0.255], t = −1.67, p = 0.237). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0 %, 95 % CI – [0.0 %; 89.6 %]).

Visual long-term memory was estimated only in 2 studies (n = 232) and the difference was not significant (d = −0.67, 95 % CI – [−1.615; 0.270], t = −9.06, p = 0.070). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0 %).

3.4.4. Working memory

Working memory was measured in five studies (Guo et al., 2021; Miskowiak et al., 2021, Poletti et al., 2021, Zhou et al., 2020, Wild et al., 2021; n = 9318). Group differences were insignificant (d = −0.059, 96 % CI – [−0.359; 0.241], t = −0.54, p = 0.616). Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 65.8 %, 95 % CI – [10.6 %; 86.9 %]).

Wild et al. provided several alternative tests of working memory: Digit Span, Monkey Ladder and Token Search (Table 1). Initially Digit Span was chosen because a similar task was used by Zhou et al. Models including other measures were tested then as a part of certainty checks. Neither of them provided significant effects and between-study heterogeneity raised in both. Working memory comparisons including Monkey Ladder test: d = −0.108, 96 % CI – [−0.416; 0.199], t = −0.98, p = 0.384; I2 = 72 %; Token Search test: d = 0.006, 96 % CI – [−0.382; 0.199], t = 0.04, p = 0.967; I2 = 86.1 %.

Egger's test shows no funnel plot asymmetry (intercept – -0.746, 95 % CI – [−3.88; −2.39], t = −0.467, p = 0.673) (Suppl. 3c). According to sensitivity analysis, the study by Guo et al. had the largest influence on effect size and second-to-largest on heterogeneity, with Miskowiak et al. having the largest influence on the latter (Suppl. 6).

3.4.5. Visual-spatial attention

Visual-spatial attention was measured by two types of scores: reaction time and accuracy. Two studies (Lamontagne et al., 2021; Mattioli et al., 2021) utilized reaction time scores (n = 232). The difference was not significant (d = 0.623, 96 % CI – [−0.4762; 1.7228], t = 7.20, p = 0.088). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0 %).

Accuracy scores for visual-spatial attention were pooled from four studies (Poletti et al., 2021, Zhao et al., 2021, Wild et al., 2021, Zhou et al., 2020; n = 8927). The difference was close to being significant (d = −0.276, 95 % CI – [−0.557; 0.005], t = −3.13, p = 0.052). Heterogeneity was moderate, approaching high (I2 = 71.5 %, 95 % CI – [18.8 %; 90.0 %]).

Egger's test shows no funnel plot asymmetry (intercept – −1.192, 95 % CI – [−4.73; −2.35], t = −0.659, p = 0.578) (Suppl. 3d).

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the results

The present study aimed to investigate specific cognitive functions impacted by COVID-19. No significant differences were discovered in long-term memory (for verbal and visual tasks), working memory and visual-spatial attention. COVID-19 survivors, however, performed significantly worse on verbal short-term memory tasks.

Duration of cognitive deficits. COVID-19 reconvalescents included in the overall sample completed cognitive tests at a different time after the onset of the disease. Given the small number of papers and the lack of the relevant data in several studies subgroup analysis could not be performed. Although cognitive symptoms can persist as far as one year after the illness (e.g., Lamontagne et al., 2021), there is evidence that they might improve from 3-month to 6-month follow-up (Poletti et al., 2021) or after approximately 4 months (Lamontagne et al., 2021).

Medical hypothesis of cognitive deficits. Short-term memory deficits in COVID-19 reconvalescents can be corroborated by similar impairments in the survivors of other major life-threatening illnesses (such as cancer or HIV) that induce impairments in short-term and working memory, language skills and processing speed (Peukert et al., 2020; Simó et al., 2013; Spies et al., 2020). Studies of classical (as opposed to COVID-19-related) acute respiratory distress syndrome show that 37–55 % of the survivors experience impairments in memory and executive functions (Fazzini et al., 2022). A risk factor for cognitive impairments after COVID-19 is intensive care that is necessary for 10 %–20 % of COVID-19 patients (Jain & Yuan, 2020; Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2020). Critical care in general is associated with cognitive dysfunction, depression and PTSD (Desai et al., 2011), but sedation seems to posit a particular risk for delirium, which exacerbates long-term cognitive dysfunction (Frontera, 2011; Porhomayon et al., 2016).

Explanations from the neurocognitive perspective cite changes in the gray and white matter as a source of these impairments. These changes might occur early in the treatment due to the neurotoxicity of chemotherapy, heightened cytokine levels or hormonal changes and persist for at least a year after treatment cessation (Simó et al., 2013). Neuroinflammation can cause functional and cognitive impairments, the most impacted cognitive functions being memory, attention and processing speed (Rengel et al., 2019). Neuroinflammation can arise from significant cytokine (interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β) increase reported in COVID-19, which is suggested as a key mechanism of attention and memory deficits (Alnefeesi et al., 2021).

Another brain structure known for its associations with cognitive functioning and at risk both in cancer and COVID-19 is hippocampus (Peukert et al., 2020); inflammation in this structure produces significant short-term memory deficits according to animal models of chemotherapy (Matsos & Johnston, 2019). Hippocampus is vulnerable to pro-inflammatory cytokines (Simó et al., 2013), which drastically increase in severe and critical cases of COVID-19 (Mulchandani et al., 2021).

Cognitive deficits can be associated with specific COVID-19-related mechanisms. The way COVID-19 specifically targets sustentacular olfactory cells arguably forms the basis of nose-to-brain infection route, which means central nervous system is particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus (Butowt & von Bartheld, 2021). Another danger comes from the fact that SARS-CoV-2 affects cells with human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors frequently found in the nervous system (Camargo-Martínez et al., 2021). The most frequent neurological complication of COVID-19 is stroke, manifesting as small diffuse lesions in cortical and sub-cortical regions (Ghannam et al., 2020). While rare and associated with severe cases, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, necrotizing encephalopathies (Zamani et al., 2021) and autoimmune anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis (Vasilevska et al., 2021) can lead to diminished cognitive capacity (namely, in working memory) and psychiatric manifestations (altered state of consciousness, hallucinations). The virus can also affect brain regions involved in higher level cognition indirectly, given the fact that olfactory system has projections onto regions among which are orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus (Patel & Pinto, 2014).

A link between cognitive deficits after COVID-19 and illness severity would be a proof of the medical hypothesis. Although it exists, it must be noted that in the samples where illness severity was described only a small percentage of post-COVID-19 participants reported ICU admission or ventilation. Most cases in our meta-analysis were asymptomatic, mild or moderate, requiring no hospitalization and getting treatment at home; thus, short-term memory impairment was not associated with illness severity for the most part of the sample. However, studies with more severe cases might have been excluded because they included participants who could not complete objective cognitive tasks (e.g., patients with delirium). It must be noted that including more severe cases could bring forth a different picture of cognitive deficits and yield more support to the medical hypothesis of their origin.

Psychopathological hypothesis of cognitive deficits. Cognitive deficits after COVID-19 (especially, self-reported cognitive complaints) can also be explained from the point of view of psychological distress (Gouraud et al., 2021), namely, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Large scale systematic reviews indicate that the prevalence of depression (16–33 %) and anxiety (15–32 %) has considerably increased after March 2020, as well as stress (30 %) and psychological distress (13 %) (Cénat et al., 2021; Salari et al., 2020). These numbers are even bigger in COVID-19 patients, especially with pre-existing conditions (Luo et al., 2020) and in specific vulnerable groups such as the elderly, residents of nursing homes and healthcare workers (Ciuffreda et al., 2021; Crocamo et al., 2021; Marvaldi et al., 2021).

PTSD symptoms are reported by 22 % of the general population (Cénat et al., 2021), up to 92 % of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (Vindegaard & Benros, 2020) and 10–30 % of survivors after hospital discharge (Vanderlind et al., 2021). Stress can uniquely contribute to cognitive impairment beyond the neurocognitive effects of the virus (Spies et al., 2020), and depression is linked to working memory deficits (Nikolin et al., 2021). Cortisol, also dubbed ‘the stress hormone’, is known to impact retrieval both from short-term and long-term memory (Wolf, 2008). In must be noted that the definition of PTSD in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – 5th edition (APA, 2013) includes difficulties in concentration and sleep disturbances (criterion E, ‘Marked alterations in arousal and reactivity’) so frequently reported by COVID-19 ‘long-haulers’ (Davis et al., 2021; Sarker & Ge, 2021), which offers another explanation for cognitive deficits. There's also evidence on the influence of suggestibility on self-reported cognitive dysfunction (Winter & Braw, 2022), which is an important finding given the spread of information and misinformation about COVID-19 in the mass media and its influence on health-related decisions.

Unfortunately, these relationships could not be tested in the current meta-analysis due to the small number of studies. Most studies that we have included reported measures of mental distress, but they varied in the presentation of the results, and for the most part ran the assessments only in COVID+ groups. About a third of the sample in the study by Wild et al. (2021) had clinically significant scores on anxiety and depression inventories. Higher depression, anhedonia (Lamontagne et al., 2021) and stress (Mattioli et al., 2021) were discovered in COVID-19 survivors. Miskowiak et al. (2021) reported moderate correlations between depression and anxiety scores, and global cognitive functioning, and Poletti et al. (2021) discovered interactions between depression and cognitive functions in their impact on the quality of life. On the contrary, only Zhao et al. (2021) did not yield any significant differences between post-covid and control groups on the measures of depression, anxiety, and apathy.

All of these results point to the association between mental distress and cognitive deficits in COVID-19 reconvalescents. However, the nature of these correlations and the existence of possible physiological confounders are subject to further investigation. Thus the results cannot prove or refute either of the hypotheses on the nature of the deficits.

Comparison to other reviews. Existing systematic reviews of impairments in specific cognitive domains after COVID-19 paint a broad picture. Affected cognitive functions include memory (Biagianti et al., 2022; Crivelli et al., 2022; Daroische et al., 2021;Groff et al., 2021 ; Schou et al., 2021 ; Zeng et al., 2022), specifically, delayed recall (Bertuccelli et al., 2022); executive functions in general (Biagianti et al., 2022; Crivelli et al., 2022), attention (Bertuccelli et al., 2022; Biagianti et al., 2022; Crivelli et al., 2022; Daroische et al., 2021) and concentration (Groff et al., 2021; Schou et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2022), inhibition and set shifting (Bertuccelli et al., 2022), processing speed and working memory (Tavares-Júnior et al., 2022), language abilities and verbal fluency (Daroische et al., 2021; Schou et al., 2021), and praxis abilities (Schou et al., 2021). Visual-spatial abilities do not seem to be affected (Bertuccelli et al., 2022). However none of these reviews included studies with control groups and the authors were unable to synthesize the data.

Our results specify the findings listed above. Verbal short-term memory impairments were corroborated by data synthesis; visual-spatial short-term memory could also probably be affected. However, no long-term memory impairments were found. Attention impairments reported by other studies were not corroborated by the present study, although the effect size was close to significant. It can be hypothesized that the effect size could have been significant had we managed to collect more data. Nevertheless, the results of our meta-analysis are encouraging, considering that self-reported cognitive deficits involve broader domains than our findings show.

4.2. Quality of evidence

Only 8 studies that fit the eligibility criteria were selected for the review. The quality of the studies was rated as fairly good (three were given 100 % ratings, and 5 were rated at 92–93 %). The biggest concern to the quality of the review is the inclusion of a study where post-COVID patients could participate less than a month after the illness (Mattioli et al., 2021).

Picking out effects to make meaningful comparisons (by cognitive function tested and measure specifics) made the groups very small (number of studies ranging from 2 to 5). The small number of studies made it hard to check for publication bias, although a funnel plot with all the effects used in the comparisons seems to be roughly symmetrical (Suppl. 3e), with both significant and non-significant effects present.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study can be attributed to its methodology and the reliance on the ‘gold’ standard of conducting and reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). The criteria we developed in order to select relevant sources was strict enough to exclude studies that relied on self-report measures or tests of global cognitive deficits (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Mini-Mental State Examination). Thus, only the results of the objective cognitive tests were taken in consideration. The studies were also excluded if they did not include a healthy control group. These strict criteria and the rigorous search for relevant studies helped us validate the pooled effect sizes for different cognitive domains and strengthened the claims made as the result of the meta-analysis.

However, the same search criteria also limited the study in a number of ways. The limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis lowers the confidence for the pooled effect sizes. Effect sizes for visual attention and visual short-term memory are small to medium and close to the significance level; although we hypothesize that they are impaired in COVID-19 reconvalescents, more studies could specify both the magnitude and the significance of these changes. We have not found enough studies to perform a number of tests (meta-regressions, subgroup analysis).

The studies also used different objective tests in various settings (e.g., online or supervised, using computer, tablet or pencil-and-paper measures) with various instructions. A number of different indices were used to assess cognitive functioning even within the same domain (e.g., number of correct answers or errors, reaction time). We addressed this issue by running specific models for each subgroup of measures, however this is why some of the models included a very small number of studies.

Most of the original studies were observational cross-sectional by design, meaning that potential confounders could be unnoticed. One of the studies included samples highly differing in size (Wild et al., 2021); and in several studies post-COVID groups were slightly older than healthy controls. Strict exclusion criteria might have cost us important results as we excluded a number of studies that only used self-reported measures.

Lastly, it can take months for articles to be published in peer-reviewed journals, and hence, due to the lack of studies that met our criteria, we had to include three preprints in our analysis in order to enlarge the number of controlled studies. However, we admit that the validity of non-peer-reviewed articles is more questionable than the validity of articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

4.4. Practical implications and future research

4.4.1. Practical implications

The variety of complications after COVID-19 makes it challenging to highlight specific targets for long-term rehabilitation. The findings of our study support that particular cognitive deficits are present in people who have recovered from COVID-19, therefore neuropsychological rehabilitation (especially focusing on short-term memory) must be the key part of long-term rehabilitation procedures. These findings will help healthcare providers to better understand the cognitive profiles of COVID-19 reconvalescents and, thus, organize better service that meets the needs of patients.

Although the impact of risk factors on cognitive deficits after COVID-19 could not be assessed in the current review, existing evidence shows that older age, preexisting cognitive deficits and symptoms of mental distress due to the illness could make individuals more vulnerable to the effects of the disease. Thus, an argument can be made for earlier assessment of cognitive deficits in multiple domains in these specific groups in order to provide tailored interventions for reconvalescents with a worse prognosis.

4.4.2. Future research

Cognitive sequelae of COVID-19 are a novel research problem and have yet to be studied in detail. Although testing specific cognitive functions can be a daunting task both for researchers and their participants, especially those who develop worse outcomes, we agree with Daroische et al. (2021) that testing cognitive functions with objective measures is an important next step in studying the problem. More validated computerized measures like the ones that were used in several studies we included in our analysis (Wild et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020) might help gather more data from vulnerable populations. Using ‘second-level’ neuropsychological tests can be especially useful in patients with relatively mild cognitive impairments who express a need in cognitive rehabilitation, to corroborate their concerns and tailor specific rehabilitation programs for their needs.

We also suggest more extensive data-collection protocols for online studies, as the participants' location, education, socioeconomic status, illness severity and preexisting chronic conditions might constitute important confounding variables. Time after symptoms onset emerges as another problematic variable, given that (1) some people who develop long-term sequelae are asymptomatic and (2) distinguishing between acute COVID-19 and recovery might be difficult, especially in the early stages or when the remaining symptoms significantly decrease the quality of life.

5. Conclusions

The present systematic review and meta-analysis provides an attempt to summarize the impact of COVID-19 on specific cognitive functions to deepen our understanding of possible symptoms in post-COVID condition and gain insights about providing help to those who experience them. Our findings imply that short-term memory in the verbal domain, and possibly, visual short-term memory and attention, are at risk in COVID-19 reconvalescents.

Funding information

This publication has been supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System, project no. 212201-2-000.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103838.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data from the original studies is included in Suppl. 2.

References

- Alnefeesi Y., Siegel A., Lui L., Teopiz K.M., Ho R., Lee Y., Nasri F., Gill H., Lin K., Cao B., Rosenblat J.D., McIntyre R.S. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cognitive function: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.621773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Badenoch J.B., Rengasamy E.R., Watson C., Jansen K., Chakraborty S., Sundaram R.D., Hafeez D., Burchill E., Saini A., Thomas L., Cross B., Hunt C.K., Conti I., Ralovska S., Hussain Z., Butler M., Pollak T.A., Koychev I., Michael B.D., Rooney A.G.… Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Communications. 2021;4(1) doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi S., Rücker G., Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2019;22:153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccelli M., Ciringione L., Rubega M., Bisiacchi P., Masiero S., Del Felice A. Cognitive impairment in people with previous COVID-19 infection: A scoping review. Cortex. 2022;154:212–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagianti B., Di Liberto A., Nicolò Edoardo A., Lisi I., Nobilia L., de Ferrabonc G.D., Zanier E.R., Stocchetti N., Brambilla P. Cognitive assessment in SARS-CoV-2 patients: A systematic review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022;14 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.909661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butowt R., von Bartheld C.S. Anosmia in COVID-19: Underlying mechanisms and assessment of an olfactory route to brain infection. The Neuroscientist. 2021;27:582–603. doi: 10.1177/1073858420956905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Martínez W., Lozada-Martínez I., Escobar-Collazos A., Navarro-Coronado A., Moscote-Salazar L., Pacheco-Hernández A., Janjua T., Bosque-Varela P. Post-COVID 19 neurological syndrome: Implications for sequelae's treatment. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2021;88:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceban F., Ling S., Lui L.M.W., Lee Y., Gill H., Teopiz K.M., Rodrigues N.B., Subramaniapillai M., Di Vincenzo J.D., Cao B., Lin K., Mansur R.B., Ho R.C., Rosenblat J.D., Miskowiak K.W., Vinberg M., Maletic V., McIntyre R.S. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2022;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J.M., Blais-Rochette C., Kokou-Kpolou C.K., Noorishad P.G., Mukunzi J.N., McIntee S.E., Dalexis R.D., Goulet M.A., Labelle P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A., Sahota D. StatTools. Combine means and SDs. http://www.obg.cuhk.edu.hk/ResearchSupport/StatTools/CombineMeansSDs_Pgm.php

- Ciuffreda G., Cabanillas-Barea S., Carrasco-Uribarren A., Albarova-Corral M.I., Argüello-Espinosa M.I., Marcén-Román Y. Factors associated with depression and anxiety in adults 60 years old during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18:11859. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crivelli L., Palmer K., Calandri I., Guekht A., Beghi E., Carroll W., Frontera J., García-Azorín D., Westenberg E., Winkler A.S., Mangialasche F., Allegri R.F., Kivipelto M. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2022;18(5):1047–1066. doi: 10.1002/alz.12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocamo C., Bachi B., Calabrese A., Callovini T., Cavaleri D., Cioni R.M., Moretti F., Bartoli F., Carrà G. Some of us are most at risk: Systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of depressive symptoms among healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;131:912–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daroische R., Hemminghyth M.S., Eilertsen T.H., Breitve M.H., Chwiszczuk L.J. Cognitive impairment after COVID-19: A review on objective test data. Frontiers in Neurology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.699582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H.E., Assaf G.S., McCorkell L., Wei H., Low R.J., Re'em Y., Redfield S., Austin J.P., Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Yan X., Yuan L. Human genetic basis of coronavirus disease 2019. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021;6:344. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S.V., Law T.J., Needham D.M. Long-term complications of critical care. Critical Care Medicine. 2011;39:371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkshoorn A., van Stralen H.E., Sloots M., Schagen S.B., Visser-Meily J., Schepers V. Prevalence of cognitive impairment and change in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psycho-Oncol. 2021;30:635–648. doi: 10.1002/pon.5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellul M.A., Benjamin L., Singh B., Lant S., Michael B.D., Easton A., Kneen R., Defres S., Sejvar J., Solomon T. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurology. 2020;19:767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzini B., Battaglini D., Carenzo L., Pelosi P., Cecconi M., Puthucheary Z. Physical and psychological impairment in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2022;129:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fialho R., Pereira M., Bucur M., Fisher M., Whale R., Rusted J. Cognitive impairment in HIV and HCV co-infected patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2016;28 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1191614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontera J.A. Delirium and sedation in the ICU. Neurocritical Care. 2011;14:463–474. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannam M., Alshaer Q., Al-Chalabi M., Zakarna L., Robertson J., Manousakis G. Neurological involvement of coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review. Journal of Neurology. 2020;267:3135–3153. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09990-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouraud C., Bottemanne H., Lahlou-Laforêt K., Blanchard A., Günther S., Batti S.E., Auclin E., Limosin F., Hulot J.S., Lebeaux D., Lemogne C. Association between psychological distress, cognitive complaints, and neuropsychological status after a severe COVID-19 episode: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.725861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff D., Sun A., Ssentongo A.E., Ba D.M., Parsons N., Poudel G.R., Lekoubou A., Oh J.S., Ericson J.E., Ssentongo P., Chinchilli V.M. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Ballesteros A.B., Yeung S.P., Liu R., Saha A., Curtis L., Kaser M., Haggard M.P., Cheke L.G. medRxiv 2021.10.27.21265563; 2021. COVCOG 2: Cognitive and Memory Deficits in Long COVID: A Second Publication From the COVID and Cognition Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A., Trender W., Chamberlain S.R., Jolly A.E., Grant J.E., Patrick F., Mazibuko N., Williams S.C., Barnby J.M., Hellyer P., Mehta M.A. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M., Cuijpers P., Furukawa T., Ebert D.D. dmetar: companion R package for the guide 'doing meta-analysis in R'. R package version 0.0.9000. 2019. https://dmetar.protectlab.org/

- Hodgson K.D., Hutchinson A.D., Wilson C.J., Nettelbeck T. A meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2013;39:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozo S.P., Djulbegovic B., Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V., Yuan J.M. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2020;65:533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl C., McIntosh E.J., Unger S., Haddaway N.R., Kecke S., Schiemann J., Wilhelm R. Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: A case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environmental Evidence. 2018;7:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13750-018-0115-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne S.J., Winters M.F., Pizzagalli D.A., Olmstead M.C. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: Evidence of mood & cognitive impairment. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health. 2021;17 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvaldi M., Mallet J., Dubertret C., Moro M.R., Guessoum S.B. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;126:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli F., Stampatori C., Righetti F., Sala E., Tomasi C., De Palma G. Neurological and cognitive sequelae of Covid-19: A four month follow-up. Journal of Neurology. 2021;268:4422–4428. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10579-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsos A., Johnston I.N. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments: A systematic review of the animal literature. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019;102:382–399. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskowiak K.W., Johnsen S., Sattler S.M., Nielsen S., Kunalan K., Rungby J., Lapperre T., Porsberg C.M. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID-19 hospital discharge: Pattern, severity and association with illness variables. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moola S., Munn Z., Tufanaru C., Aromataris E., Sears K., Sfetcu R., Currie M., Lisy K., Qureshi R., Mattis P., Mu P. In: JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. JBI; 2020. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulchandani R., Lyngdoh T., Kakkar A.K. Deciphering the COVID-19 cytokine storm: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2021;51 doi: 10.1111/eci.13429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian A., Sehgal K., Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., McGroder C., Stevens J.S., Cook J.R., Nordvig A.S., Shalev D., Sehrawat T.S., Ahluwalia N., Bikdeli B., Dietz D., Der-Nigoghossian C., Liyanage-Don N., Rosner G.F., Bernstein E.J., Mohan S., Beckley A.A., Wan E.Y. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M., Ogilvie J.M., Wilson J.S., Green H.J., Chambers S.K., Ownsworth T., Shum D.H.K. A meta-analysis of cognitive impairment and decline associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2015;5 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolin S., Tan Y.Y., Schwaab A., Moffa A., Loo C.K., Martin D. An investigation of working memory deficits in depression using the n-back task: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;284:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., Moher D.… The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;71 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandharipande P.P., Girard T.D., Jackson J.C., Morandi A., Thompson J.L., Pun B.T., Brummel N.E., Hughes C.G., Vasilevskis E.E., Shintani A.K., Moons K.G., Geevarghese S.K., Canonico A., Hopkins R.O., Bernard G.R., Dittus R.S., Ely E.W., BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R.M., Pinto J.M. Olfaction: Anatomy, physiology, and disease. Clinical Anatomy. 2014;27:54–60. doi: 10.1002/ca.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peukert X., Steindorf K., Schagen S.B., Runz A., Meyer P., Zimmer P. Hippocampus-related cognitive and affective impairments in patients with breast cancer – A systematic review. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10:147. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N., Amos T., Kuo C., Hoare J., Ipser J., Thomas K.G., Stein D.J. HIV-associated cognitive impairment in perinatally infected children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;138 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti S., Palladini M., Mazza M.G., De Lorenzo R., COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study group. Furlan R., Ciceri F., Rovere-Querini P., Benedetti F. Long-term consequences of COVID-19 on cognitive functioning up to 6 months after discharge: Role of depression and impact on quality of life. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00406-021-01346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porhomayon J., El-Solh A.A., Adlparvar G., Jaoude P., Nader N.D. Impact of sedation on cognitive function in mechanically ventilated patients. Lung. 2016;194:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengel K.F., Hayhurst C.J., Pandharipande P.P., Hughes C.G. Long-term cognitive and functional impairments after critical illness. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2019;128:772–780. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P., Alvarado-Arnez L.E., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Franco-Paredes C., Henao-Martinez A.F., Paniz-Mondolfi A., Lagos-Grisales G.J., Ramírez-Vallejo E., Suárez J.A., Zambrano L.I., Villamil-Gómez W.E., Balbin-Ramon G.J., Rabaan A.A., Harapan H., Sah R. Latin American Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19 Research (LANCOVID-19). Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker A., Ge Y. Mining long-COVID symptoms from reddit: Characterizing post-COVID syndrome from patient reports. JAMIA Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou T.M., Joca S., Wegener G., Bay-Richter C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 – a systematic review. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2021;97:328–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simó M., Rifà-Ros X., Rodriguez-Fornells A., Bruna J. Chemobrain: A systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:1311–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano J.B., Allan M., Alsokhn C., Alwan N.A., Askie L., Davis H.E., Diaz J.V., Dua T., de Groote W., Jakob R., Lado M., Marshall J., Murthy S., Preller J., Relan P., Schiess N., Seahwag A. World Health Organization; 2021. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 [Google Scholar]

- Spies G., Mall S., Wieler H., Masilela L., Castelon Konkiewitz E., Seedat S. The relationship between potentially traumatic or stressful events, HIV infection and neurocognitive impairment (NCI): A systematic review of observational epidemiological studies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2020;11:1781432. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1781432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracciari A., Bottini G., Guarino M., Magni E., Pantoni L., “Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology” Study Group of the Italian Neurological Society Cognitive and behavioral manifestations in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Not specific or distinctive features? Neurol. Sci. 2021;42:2273–2281. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05231-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Dercon Q., Luciano S., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Harrison P.J. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: A 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Medicine. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares-Júnior J.W.L., de Souza A.C.C., Borges J.W.P., Oliveira D.N., Siqueira-Neto J.I., Sobreira-Neto M.A., Braga-Neto P. COVID-19 associated cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Cortex. 2022;152:77–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlind W.M., Rabinovitz B.B., Miao I.Y., Oberlin L.E., Bueno-Castellano C., Fridman C., Jaywant A., Kanellopoulos D. A systematic review of neuropsychological and psychiatric sequalae of COVID-19: Implications for treatment. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2021;34:420–433. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kessel S.A.M., Olde Hartman T.C., Lucassen P.L.B.J., van Jaarsveld C.H.M. Post-acute and long-COVID-19 symptoms in patients with mild diseases: A systematic review. Family Practice. 2022;39(1):159–167. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmab076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilevska V., Guest P.C., Bernstein H.G., Schroeter M.L., Geis C., Steiner J. Molecular mimicry of NMDA receptors may contribute to neuropsychiatric symptoms in severe COVID-19 cases. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:245. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02293-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild C., Norton L., Menon D., Ripsman D., Swartz R., Owen A. Seeing through brain fog: Disentangling the cognitive, physical, and mental health sequalae of COVID-19. Preprint (Version 1) Research Square. 2021 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-373663/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D., Braw Y. COVID-19: Impact of diagnosis threat and suggestibility on subjective cognitive complaints. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2022;22 doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf O.T. The influence of stress hormones on emotional memory: Relevance for psychopathology. Acta Psychologica. 2008;127(3):513–531. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo M.S., Malsy J., Pöttgen J., Zai S., Ufer F., Hadjilaou A., Schmiedel S., Addo M.M., Gerloff C., Heesen C., Schulze Zur Wiesch J., Friese M.A. Frequent neurocognitive deficits after recovery from mild COVID-19. Brain Communications. 2020;2 doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamani R., Pouremamali R., Rezaei N. Central neuroinflammation in Covid-19: A systematic review of 182 cases with encephalitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and necrotizing encephalopathies. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2021 doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2021-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng N., Zhao Y.M., Yan W., Li C., Lu Q.D., Liu L., Ni S.Y., Mei H., Yuan K., Shi L., Li P., Fan T.T., Yuan J.L., Vitiello M.V., Kosten T., Kondratiuk A.L., Sun H.Q., Tang X.D., Liu M.Y., Lu L.… A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: Call for research priority and action. Molecular Psychiatry. 2022;6:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01614-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Shibata K., Hellyer P.J., Trender W., Manohar S., Hampshire A., Husain M. Rapid vigilance and episodic memory decrements in COVID-19 survivors. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.06.21260040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Lu S., Chen J., Wei N., Wang D., Lyu H., Shi C., Hu S. The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;129:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data from the original studies is included in Suppl. 2.