Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) sexual transmission among men who have sex with men (MSM) has increased markedly in Beijing, China in the past decade. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly efficacious biomedical prevention strategy that remarkably reduces HIV-transmission risk. This study examined PrEP awareness among MSM and the factors influencing it. From April to July 2021, respondent-driven sampling was used to conduct a cross-sectional survey among MSM in Beijing, China. Demographic, behavior, and awareness data regarding PrEP were collected. The factors influencing PrEP awareness were assessed using univariate and multivariable logistic regression. In total, 608 eligible responders were included in the study. Among the respondents, 27.9% had PrEP awareness, 3.3% had taken PrEP, and 57.9% expressed interest in receiving PrEP, if required. Greater odds of PrEP awareness were associated with higher education level (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.525, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.013–6.173, P < 0.0001), greater HIV-related knowledge (aOR 3.605, 95% CI 2.229–5.829, P < 0.0001), HIV testing (aOR 2.647, 95% CI 1.463–4.788, P = 0.0013), and sexually transmitted infections (aOR 2.064, 95% CI 1.189–3.584, P = 0.0101). Lower odds of PrEP awareness were associated with higher stigma score (aOR 0.729, 95% CI 0.591–0.897, P = 0.0029). The findings indicate sub-optimal awareness and low utilization of PrEP in Beijing and highlight PrEP inequities among MSM with stigma. Strengthening the training of peer educators in disseminating PrEP knowledge and reducing stigma are critical for improving PrEP awareness.

Subject terms: HIV infections, Epidemiology

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) in China are at a risk of HIV infection. HIV prevalence among MSM has increased from 0% in 2001 to 22.91% in 20181. Sexual transmission by MSM is the most commonly reported route of HIV transmission in Beijing. This group is disproportionately affected by HIV and accounts for 77.97% of newly diagnosed cases2. Accordingly, MSM is considered a critical group to access and use antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP, a biomedical HIV prevention method, reduces the risk of sexual acquisition by more than 90% when taken with high adherence3.

Furthermore, PrEP is cost-effective based on modeling studies conducted in Germany, UK, and the Netherlands4–6. The World Health Organization has recommended the use of PreP in 2014 after the first PrEP studies have been published7. PrEP is an important biomedical tool for HIV prevention, and more than 50 countries and regions have approved its use8. In China, considering the price, as well as the adherence and potential risk of PrEP use, its actual acceptance is limited. PrEP only became available for uninfected people in 20209. National guidelines based on oral emtricitabine/tenofovir were issued in 202110. Individuals who require PrEP needs to be aware of its existence. However, related studies in China are limited. The most recent study was conducted in southern China with awareness of 43.1% in 201711 and 52.7% in 201912. Considering that PrEP knowledge is a prerequisite (although not sufficient) for its acceptability, the current study aimed to elucidate the behavioral and demographic parameters that are correlated with PrEP. These parameters toned to be identified to provide population-specific information. We aimed to study the factors associated with PrEP awareness among MSM. The results of our analysis will help policymakers conceptualize better strategies to increase awareness and use of PrEP among MSM.

Methods

Study design and participants

Cross-sectional surveys were conducted from April to July 2021 in Beijing. The target population included MSM aged 18 years or above who reported oral or anal sex with at least one male sex partner in the half past year. Individuals with mental disabilities were excluded from the survey.

Sampling and recruitment

The survey was administered using the respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method13,14. RDS is a peer-referral sampling methodology for the estimation of the characteristics of underserved groups that cannot be randomly sampled. It is often implemented to identify hidden populations at risk for HIV.

From April to July 2021, nine MSM with different demographic characteristics were selected as survey seeds, and three recruitment cards were issued to each participant. They subsequently selected three MSM from their friends to participate in the survey. The seeds had to meet the following inclusion criteria15: (a) willing to recruit other MSM participants, (b) have a wide range of contacts in the MSM community, and (c) have a selection of seeds from across all types of demography. Seeds were selected according to age, marital status, education, sexual orientation, and HIV testing, and they exhibited various types of these five aspects. Each participant had a recruitment card to participate in the survey. After completing the survey, each participant received three recruitment cards. Recruitment was continued until the sample reached stability.

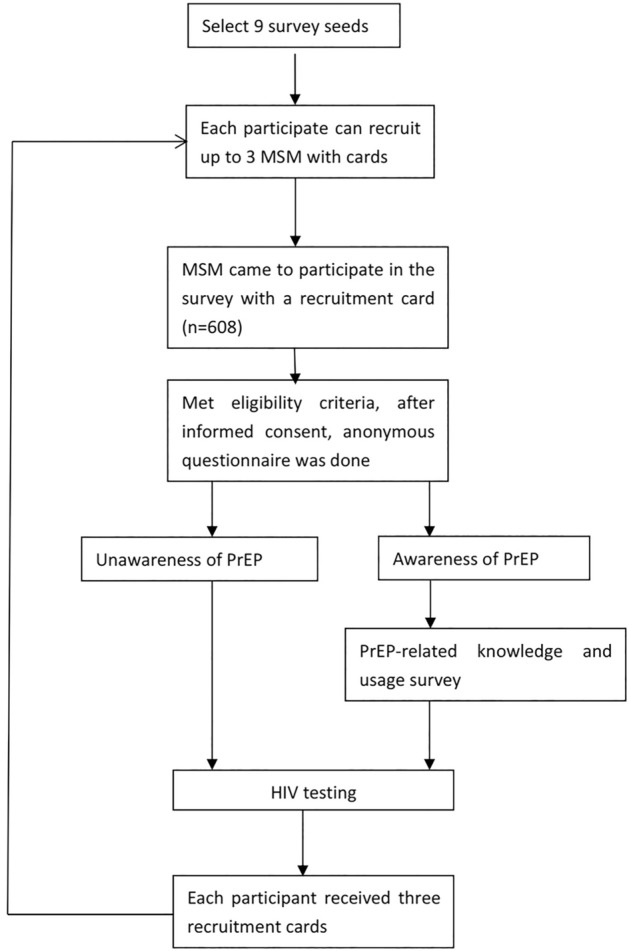

After obtaining written informed consent from the participants, each subject underwent an anonymous interview for data gathering. The participants were interviewed by skilled interviewers in a private room at the voluntary counseling and testing clinic of the Beijing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A cash reward of 50 Chinese Yuan (CNY; approximately 7–8 United States dollars) was awarded for participation in the questionnaire survey. Upon recruiting three MSM, each participant received a reward of 100 CNY. As part of the national HIV sentinel surveillance program16,17, this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, China CDC, (IRB0000276 and FWA00002958). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of eligibility and enrollment.

Sample size

Recruitment was continued until the overall sample reached stability or ‘‘equilibrium’’ and the projected sample sizes were met18. Stability was assessed by monitoring the progress of key variables throughout the recruitment process and is considered to be achieved when the proportion of these indicators does not substantially change with the subsequent waves of participants (the cumulative sample proportion at each wave does not change by more than 1.0%)14,19. Stability in age, education, marital status, sexual orientation, and HIV test in the past year were tracked. During the investigation, the sample equilibrium test of the main indicators was carried out continuously.

Measurements

The research team developed a structured questionnaire. Except for PrEP-related questions, a survey questionnaire that had been previously used in annual MSM surveys20 in Beijing for more than 10 years was employed. PrEP-related issues were added by the research team in 2021 and pre-tested in 12 young adults (not included in the study).

The questionnaire was used to collect data, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, education, marital status, and residency), frequency of condom usage during sexual contact, and previous HIV testing. PrEP awareness among MSM was assessed by asking about their awareness in PrEP [‘Have you ever heard of PrEP and its intended purpose? Please explain’]. In the evaluation of the willingness of MSM to use PrEP, only people with PrEP awareness and did not take it were asked about their willingness to use it [‘Would you like to use PrEP?’]. The willingness to use PrEP was asked based on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = definitely will not, 2 = unsure/probably will, 3 = definitely will). Participants were classified into the “willing to use PrEP” group when they endorsed responses 2 or 3. Participants who did not know about PrEP were not asked any further questions.

Participants who knew about PrEP but had not used it were asked about their reasons for declining its usage. Eight knowledge questions were included in this survey, and five of which were extracted from the United Nations General Assembly Special Session21. The statements were as follows: (1) people can protect themselves from contracting HIV by having sex with only one faithful, uninfected partner; (2) people can protect themselves from contracting HIV by using condoms; (3) a healthy-looking person can have HIV; (4) a person can acquire HIV from mosquito bites; and (5) a person can acquire HIV by sharing a meal with someone who is infected. The remaining three questions regarded the HIV transmission route: (1) a person can acquire HIV from receiving HIV-infected blood, (2) a person can acquire HIV by sharing needles with an infected individual, and (3) children born to HIV-infected women may contract HIV. All correct answers were considered as “good knowledge of HIV” and otherwise considered as “poor knowledge of HIV”. The participants’ degree of stigmatization of homosexuality was determined by asking the respondents three questions as follows22: “If a relative is part of the MSM population, will others feel ashamed?”; “Would you hide your MSM identity to avoid discrimination?”; and “Are you ashamed after having sex with other men?” Participants rated each item on a 3-point scale (0 = never/strongly disagree, 1 = sometimes/partially agree, 2 = very often/strongly agree). The final stigma score was the sum of the three responses.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire data were entered and cleaned using EpiData software (version 3.1, Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark). All results in this analysis were reported in crude by using SPSS software (Version 19.0, SPSS, Inc.,Chicago, IL,USA). For the data collected by RDS, weighting was used to adjust for respondents’ social network size23 (i.e., the larger a social network, the greater the likelihood that someone might be recruited by other participants in his social network) and recruitment patterns. The size of the social network of a MSM was measured as the number of other MSM they knew by name or nickname, by face, and who were 18 years or older, lived in Beijing, and whom they could reach. RDS adjustment was calculated using RDS Analyst Software (version 0.57) based on the differences in the social network sizes of participants24. Individualized weights of HIV (outcome variable) were calculated using RDS Analyst Software, and then exported to SAS (version 9.2). Factors associated with PrEP awareness were analyzed using survey logistic regression models by presenting odds ratio (OR) and adjusted OR (aOR). Independent variables with P < 0.10 in univariate analysis were included in multivariable regressions. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Population characteristics

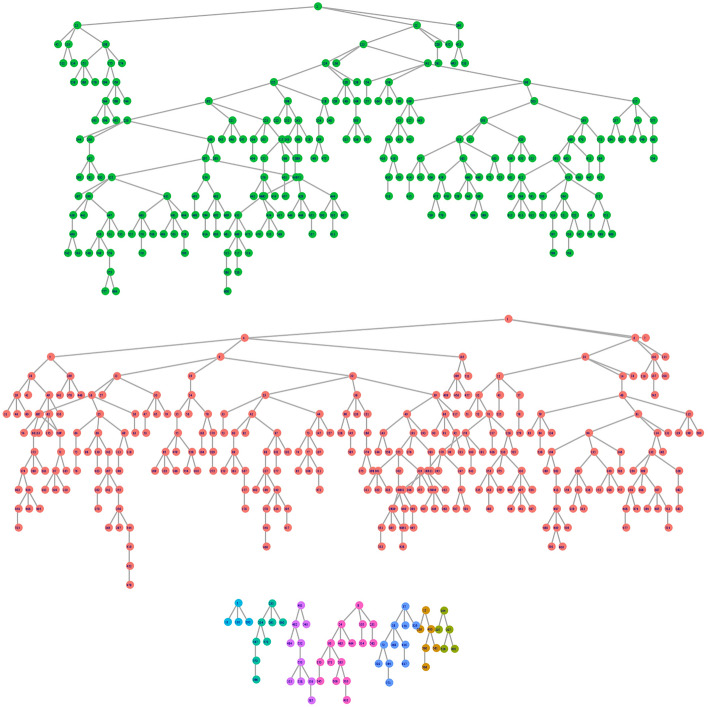

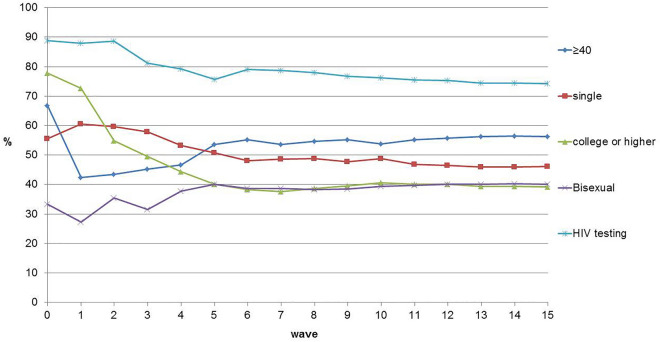

A total of 608 MSM were enrolled in this study. The recruitment trees used in the study are shown in Fig. 2. The main demographic indicators of age, marriage, education level, sexual orientation, and HIV testing in the past 12 months were balanced at waves 12, 12, 11, 7, and 10 (Fig. 3). The sample is then considered to be in equilibrium.

Figure 2.

Recruitment trees of MSM in 2021. Each point represents a participant, the recruitment order is from top to bottom, and the short line represents the recruitment relationship. Dots of the same color indicate those recruited by the same seed.

Figure 3.

Sample equilibrium by age, martial status, education, sexual orientation and HIV testing.

The average age of MSM was 41.6 years (SD ± 11.0). Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of demographics, condom use, HIV testing history, and HIV knowledge among the recruited MSM. Among the respondents, 37.9% had a college degree or higher. Homosexual orientation was observed in 58.3% of participants. Consistent condom use in sexual intercourse during the preceding 6 months was observed in 53.0% of the study population, and the self-reported history of contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) was 16.6%. Among the surveyed MSM, 33.2% were involved in sexualized drugs used in the past 6 months, and 70.9% were tested for HIV within the past 12 months. During the study, 81.7% of MSM received peer-educator support. HIV knowledge was identified in 49.0% of the MSM. The average stigma score was 3.7 (SD ± 1.2).

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral characteristics of MSM recruited in 2021 in Beijing, China (N = 608).

| Categorical variables | Crude | RDS-adjustment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | % | 95%CI | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 25 | 27 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 2.9–6.7 |

| 25–39 | 239 | 39.3 | 37.0 | 32.3–41.7 |

| ≥ 40 | 342 | 56.3 | 58.2 | 53.1–63.2 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 281 | 46.2 | 44.1 | 38.5–49.7 |

| Married/cohabiting | 238 | 39.1 | 41.1 | 35.9–46.2 |

| Divorced/widowed | 89 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 11.5–18.3 |

| Education | ||||

| Middle school or lower | 370 | 60.9 | 62.1 | 56.2–68.0 |

| College or higher | 238 | 39.1 | 37.9 | 32.0–43.9 |

| Time in Beijing (years) | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 523 | 86.0 | 85.9 | 82.5–89.3 |

| < 2 | 85 | 14.0 | 14.1 | 10.7–17.5 |

| Monthly income (CNY) | ||||

| < 5000 | 279 | 45.9 | 47.5 | 42.6–52.4 |

| 5000–10,000 | 218 | 35.9 | 35.2 | 30.9–39.4 |

| ≥ 10,000 | 111 | 18.3 | 17.4 | 13.8–21.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Bisexual | 243 | 40.0 | 41.1 | 36.3–45.9 |

| Homosexual | 362 | 59.5 | 58.3 | 53.5–63.1 |

| Heterosexuality | 2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0–0.7 |

| Asexual | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0–0.6 |

| Main means of meeting partners | ||||

| Face-to-face directly | 224 | 36.8 | 37.8 | 33.4–42.2 |

| Internet | 384 | 63.2 | 62.2 | 57.8–66.6 |

| Self-assessed risk of HIV infection | ||||

| Low | 472 | 77.6 | 76.8 | 72.9–80.6 |

| High | 136 | 22.4 | 23.3 | 19.4–27.1 |

| Awareness of PrEP | 185 | 30.4 | 27.9 | 23.7–32.2 |

| Previous PrEP use | 21 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 1.3–5.2 |

| No of MSM partners in the preceding 6 months | ||||

| 1 | 168 | 27.6 | 28.7 | 24.4–33.0 |

| 2–9 | 352 | 57.9 | 58.0 | 53.8–62.2 |

| ≥ 10 | 88 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 10.2–16.3 |

| Condom use in MSM anal sex during the preceding 6 monthsa | ||||

| Consistent | 268 | 54.5 | 53.0 | 48.1–58.0 |

| Inconsistent | 224 | 45.5 | 47.0 | 42.1–52.0 |

| Sexualized drug used during the preceding 6 months | 207 | 34.0 | 33.2 | 28.8–37.6 |

| STIs history | 113 | 18.6 | 16.6 | 13.6–19.5 |

| Peer education in preceding year | 501 | 82.4 | 81.7 | 78.1–85.3 |

| HIV testing in the preceding 12 months | 451 | 74.2 | 70.9 | 65.9–76.0 |

| Good knowledge of HIV | 308 | 50.7 | 49.0 | 44.2–53.8 |

| Continuous variable | Mean | SD | Mean | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmab | 3.7 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 3.6–3.8 |

a492 MSM had MSM anal sex during the preceding 6 months.

bmeasured on a 7-point scale from 0 to 6, 6 = extremely stigma.

Awareness, knowledge, and use of PrEP

Among the participants, 27.9% had heard of PrEP before participating in the study. A few respondents (3.3%) had taken PrEP. Table 2 shows the knowledge of PrEP among MSM. A total of 57.9% indicated intention to use PrEP in the future, if required. Participants who had heard PrEP but never taken it were asked about the reasons, and among the participants who responded to these items, 35.2% agreed that they would not take PrEP, because they preferred using condoms as protection for HIV, 28.6% had a fluke mentality, 15.1% are concerned about side effects, and 9.3% felt that they could not afford it.

Table 2.

Knowledge of PrEP among MSM recruited in 2021 in Beijing, China (n = 185) (Calculated for those who knew about PrEP).

| Crude | RDS-adjustment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | % | 95%CI | |

| Where to purchase PrEP | ||||

| Know | 150 | 81.1 | 79.8 | 72.0–87.7 |

| Unknown | 35 | 18.9 | 20.1 | 12.3–28.0 |

| Reasons for not takinga | ||||

| Expensive | 17 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 4.1–14.6 |

| Side effects | 24 | 14.6 | 15.1 | 8.7–21.5 |

| Stigma | 4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0–5.3 |

| Consistent condom use | 59 | 36.0 | 35.2 | 25.3–45.1 |

| Fluke mentality | 44 | 26.8 | 28.6 | 18.4–38.8 |

| Unknowing how to access | 4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0–5.3 |

| Previously HIV positive | 12 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 1.3–12.0 |

| Likelihood of using PrEPb | ||||

| Yes | 98 | 57.6 | 57.9 | 50.4–65.5 |

| No | 72 | 42.4 | 42.1 | 34.5–49.6 |

aCalculated for those who had not used PrEP, n = 164.

bCalculated for those who were HIV negative, n = 170.

Factors related to PrEP awareness

Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed to explore possible factors associated with PrEP awareness (Table 3). Multivariable regression results showed that MSM were three more likely to be aware of PrEP if they had a college or higher degree (aOR 3.525, 95% CI 2.013–6.173, P < 0.0001). MSM with good HIV knowledge were more likely to hear about PrEP (aOR 3.605, 95% CI 2.229–5.829, p < 0.0001). Other factors, including the use of sexualized drugs in the past 6 months (OR 2.059, 95% CI 1.276–3.322, P = 0.0031), HIV testing in the past 12 months (aOR 2.647, 95% CI 1.463–4.788, p = 0.0013), and STI infection (aOR 2.064, 95% CI 1.189–3.584, P = 0.0101) were associated with increased PrEP awareness. MSM who had higher stigma score (aOR 0.729, 95% CI 0.591–0.897, P = 0.0029) were less likely to hear about PrEP.

Table 3.

Factors associated with the PrEP awareness among MSM recruited in 2021 in Beijing, China.

| Categorical variables | Awareness | Unawareness | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR (95%CI) | P | aOR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ≥ 40 | 67 | 19.6 | 275 | 80.4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–39 | 108 | 45.2 | 131 | 54.8 | 3.832 (2.583–5.685) | < 0.0001 | 1.450 (0.803–2.619) | 0.2182 |

| < 25 | 10 | 37.0 | 17 | 63.0 | 2.372 (0.971–5.796) | 0.0581 | 1.180 (0.348–3.996) | 0.7905 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 124 | 44.1 | 157 | 55.9 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married/cohabitating | 39 | 16.4 | 199 | 83.6 | 0.251 (0.159–0.397) | < 0.0001 | 0.555 (0.286–1.076) | 0.0814 |

| Divorced/widowed | 22 | 24.7 | 67 | 75.3 | 0.376 (0.212–0.664) | 0.0008 | 0.695 (0.325–1.486) | 0.3478 |

| Time in Beijing (years) | ||||||||

| < 2 | 17 | 20.0 | 68 | 80.0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 168 | 32.1 | 355 | 67.9 | 1.771 (0.973–3.226) | 0.0616 | 1.249 (0.622–2.507) | 0.5311 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Middle school or lower | 58 | 15.7 | 312 | 84.3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| College or higher | 127 | 53.4 | 111 | 46.6 | 6.290 (4.165–9.500) | < 0.0001 | 3.525 (2.013–6.173) | < 0.0001 |

| Monthly income (CNY) | ||||||||

| < 5000 | 47 | 16.8 | 232 | 83.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5000–10,000 | 75 | 34.4 | 143 | 65.6 | 2.700 (1.723–4.231) | < 0.0001 | 1.117 (0.620–2.014) | 0.7125 |

| ≥ 10,000 | 63 | 56.8 | 48 | 43.2 | 7.002 (4.123–11.889) | < 0.0001 | 1.494 (0.718–3.108) | 0.2825 |

| Sexual orientationa | ||||||||

| Bisexual | 56 | 23.0 | 187 | 77.0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Homosexual | 128 | 35.4 | 234 | 64.6 | 1.856 (1.249–2.758) | 0.0022 | 0.687 (0.408–1.155) | 0.1562 |

| Main means of meeting partners | ||||||||

| Face-to-face directly | 55 | 24.6 | 169 | 75.4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Internet | 130 | 33.9 | 254 | 66.1 | 1.492 (1.003–2.220) | 0.0483 | 0.888 (0.528–1.492) | 0.6529 |

| Self-assessed risk of HIV infection | ||||||||

| Low | 144 | 30.5 | 328 | 69.5 | 1 | |||

| High | 41 | 30.1 | 95 | 69.9 | 0.942 (0.603–1.472) | 0.7940 | / | |

| Knowledge of HIV | ||||||||

| Poor | 46 | 15.3 | 254 | 84.7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Good | 139 | 45.1 | 169 | 54.9 | 4.700 (3.115–7.091) | < 0.0001 | 3.605 (2.229–5.829) | < 0.0001 |

| No of MSM partners in the preceding 6 months | ||||||||

| 1 | 41 | 24.4 | 127 | 75.6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2–9 | 114 | 32.4 | 238 | 67.6 | 1.665 (1.061–2.612) | 0.0266 | 1.245 (0.705–2.198) | 0.4502 |

| ≥ 10 | 30 | 34.1 | 58 | 65.9 | 1.797 (0.989–3.265) | 0.0542 | 0.897 (0.407–1.973) | 0.7861 |

| Condom use in MSM anal sex during the preceding 6 monthsb | ||||||||

| Consistent | 87 | 32.5 | 181 | 67.5 | 1 | |||

| Inconsistent | 74 | 33.0 | 150 | 67.0 | 0.964 (0.640–1.454) | 0.8628 | / | |

| Sexualized drug used during the preceding 6 months | ||||||||

| No | 90 | 22.4 | 311 | 77.6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 95 | 45.9 | 112 | 54.1 | 3.031 (2.060–4.460) | < 0.0001 | 2.059 (1.276–3.322) | 0.0031 |

| HIV testing in the preceding 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 26 | 16.6 | 131 | 83.4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 159 | 35.3 | 292 | 64.7 | 3.278 (1.997–5.380) | < 0.0001 | 2.647 (1.463–4.788) | 0.0013 |

| STI history | ||||||||

| No | 140 | 28.2 | 356 | 71.8 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 45 | 40.2 | 67 | 59.8 | 1.935 (1.221–3.069) | 0.0050 | 2.064 (1.189–3.584) | 0.0101 |

| Peer education in preceding 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 29 | 27.1 | 78 | 72.9 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 156 | 31.1 | 345 | 68.9 | 1.456 (0.877–2.419) | 0.1462 | / | |

| Continuous variable | Awareness | Unawareness | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | OR (95%CI) | P | aOR (95%CI) | P | |

| Stigma scorec | 3.3 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 0.674 (0.573–0.792) | < 0.0001 | 0.729 (0.591–0.897) | 0.0029 |

a Sexual orientation removes heterosexuality and nonsexuality.

b 492 MSM has MSM anal sex during the past six months.

c measured on a 7-point scale from 0 to 6, 6 = extremely stigma.

Discussion

This study was the first to investigate the awareness and use of PrEP among MSM in China by using RDS method. The results showed that the awareness and willingness on PrEP use were low. MSM with high education level, using sexualized drug, and undergoing HIV testing had a high awareness rate of PrEP, high MSM stigma would reduce the awareness rate. Peer education and MSM-related websites did not affect the promotion of PrEP.

RDS is a long-chain peer referral recruitment method and is a quasi-probability sampling method that allows population-based inferences through statistical adjustments25. A review26 of more than 120 RDS studies conducted worldwide found that RDS is an effective technique when designed and implemented appropriately for the sampling of most-at-risk populations for HIV biological and behavioral surveys. Samples generally reached equilibrium at approximately 10 waves27. The main indicators in this study reached equilibrium at waves 7–12. The sample represents MSM in Beijing to a certain extent.

Awareness and willingness uptake of PrEP

In the present study, 27.9% of MSM had heard about PrEP. This awareness is better than those from surveys conducted in previous years in China (22.4% in 201728, 22%29 and 11.2%30 in 2010), but it is lower than that in a recent research (52.7% in 201912). Awareness on PrEP use also varies widely by geographical region; the rate of PrEP awareness among the present MSM was higher than that reported in Myanmar in 2014 (5%)31 and lower than the reported values in US in 2018 (54.8%)32 and Brazil and Malaysia in 2016 (61.3%33 and 44%34). This finding was obtained possibly because if PrEP is promoted for a long time28–34 and the HIV infection rate is high12, the promotion of PrEP will be accelerated. In addition, the survey carried out in the unit promoting PrEP will also result in increased awareness12. Therefore, the results of a study in one region or one study might not be generalizable worldwide.

Notably, the percentage of MSM who reported PrEP use was extremely low. The 3.3% uptake rate in the present study was similar to that in study of MSM in US in 2018 (2.5%)32. MSM who had previously heard of PrEP were much more likely to accept PrEP in the future12,28. However, in the present study, a brief introduction to PrEP did not effectively increase the willingness to use. Only 57.9% of MSM who had heard about PrEP indicated intent to use it in the future. This finding is similar to that in other studies in China (e.g. 64.0%30, 67.8%12, 71.3%35) and among YMSM in America (55.3%)36 and Lebanon (53.5%)37.

Similar to other studies38–40, the most common barrier to PrEP utilization is the belief that condom use is a more feasible form of HIV prevention than PrEP. In addition, although oral Tenofovir-based PrEP regimens are effective and safe for MSM41–44, 15.1% of MSM in the present sample were concerned about PrEP’s side effects. Even 28.6% believe that they are safe from HIV infection during unprotected sex. Therefore, the detailed effectiveness and safety profile of PrEP should be prioritized for PrEP initiation to maximize informed decision-making among potential users45. Therefore, physicians need to build awareness among at-risk populations who may benefit from PrEP and strengthen their knowledge training about PrEP.

Factors associated with awareness of PrEP

Demographic characteristic

Consistent with previous studies, higher education levels were the associated with PrEP awareness among MSM46–49. This finding may be related to the unique national conditions and policies regarding the promotion of PrEP or a strong understanding and acceptance of new modalities.

High-risk sexual behavior

The influence of different risky behaviors on PrEP awareness was different. MSM who took sexualized drug had better awareness than those who did not. However, the number of sexual partners and anal condom use did not affect the awareness of PrEP.

Sexualized drug use refers to the use of any psychoactive substance before or during sexual intercourse50. Psychoactive substances adversely affect users’ capacity to perceive and respond to risks during sexual encounters, leading to high-risk sexual practices51 and infection with HIV and other STIs52. In the present study, one-third of MSM took sexualized drug within six months, which is higher than the reported value in Hong Kong 2018 (14.1%)53 and lower than those in UK (41%)54 and Australia (54%)55. Mathematical models suggested that achieving 75% PrEP coverage among high-risk HIV-negative MSM in China would prevent 25.7% of new HIV infections among all MSM56. MSM with experience on recent sexualized drugs may be a priority group for future PrEP implementation. In the present study, although MSM using sexualized drug had a higher awareness of PrEP, approximately 60% of the MSM who took sexualized drug remained unaware of PrEP, highlighting that effective strategies to promote PrEP are needed for this group of MSM in China.

Consistent with other studies46,49,57,58, the awareness of PrEP in the present study was not associated with the number of MSM partners or condom use in MSM anal sex. This finding was obtained possibly because the popularity of PrEP is insufficient (less than half of MSM had heard of PrEP), especially among MSM with risky sexual behaviors.

MSM and PrEP stigma

In the present study, MSM had moderate MSM stigma. Low stigma levels related to sexual orientation are also related to increased PrEP awareness. Stigma can be perceived as a threat to social identity among MSM. The negative effect of stigma on PrEP awareness may be explained by social isolation and the lack of supportive networks. This finding corroborates the findings of other studies59–61. MSM stigma is also inextricably linked to PrEP stigma62,63, because MSM are currently the main recipients of PrEP for HIV infection prevention.

Although PrEP stigma was not serious in the present study, it remarkably affected the use of PrEP in previous studies. Rather than being viewed as merely an alternative and equally acceptable-prevention strategy, PrEP is considered a less honorable prevention choice64. This finding was obtained possibly because of the high degree of stigmatization of homosexuality65 and PrEP use being seen as a marker of promiscuity66. Considering the use of PrEP, safe behavioral constraints are lifted, and they are free to engage in sexual activity and condomless sex without fear of infection. Although the participants in this study stated that their PrEP stigma was low, this finding may not reflect the actual situation possibly because of PrEP stigma, in which many people said that they only rely on condoms 100% and do not need to take PrEP.

HIV testing and intervention services

PrEP awareness among MSM who have been tested is 2.647 times than those in untested people. Survey participants who underwent HIV-testing in the previous year had received a certain degree of HIV-related counseling, which should include education regarding prevention. Consistent with previous studies, previous HIV testing could be a marker of higher awareness for HIV risky behavior or reflect previous counselling67. These findings also supported the use of HIV testing as an entry point for biomedical and behavioral HIV prevention, including PrEP58. Previous STIs can also increase PrEP awareness, indicating that PrEP knowledge is received during healthcare consultation. However, approximately 60% of MSM who had been tested for STIs remained unaware of PrEP, highlighting a missed opportunity for targeted counseling.

Well-trained peer educators are critical in terms of delivering accurate knowledge of HIV68 and promoting harm-reduction interventions (e.g., condom use, encouraging regular HIV testing, and psychological support) through outreach activities68–70 and decreasing stigma-related HIV71. In the present study, the majority of MSM received peer education in the past 12 months. However, this condition was not related to PrEP awareness. However, peer educators may play an important role in future PrEP implementation72,73, because they are the main providers of HIV testing services for MSM in Beijing. Therefore, considering that PrEP is a relatively novel HIV prevention method, health departments should target counselling providers and peer educators for training on PrEP education and referral resources. This may help improve awareness and access to PrEP for at-risk MSM.

In the present study, online promotion did not improve PrEP awareness. MSM constitute a hidden population, and it is difficult to disseminate health-related information through the mass media. MSM-related and institutional websites have become the main channels of awareness. Since 2019, the China CDC has implemented programs and mobilized funding to support the Beijing Health Department and non-governmental organizations in PrEP implementation. They also provided extensive PrEP information online, which can be an effective resource for education/outreach programs. MSM who use the Internet as their main way of meeting sexual partners may also come across with MSM-related or institutional websites containing information about preventive measures74. However, no such connection was observed in the present study possibly because of insufficient online PrEP promotion.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. First, considering the cross-sectional design, only the association was evaluated and not the causality of the risk factors for PrEP awareness. Second, although RDS was used to improve sample representation, some biases were incurred based on how the “seeds” were selected and how MSM recruited. For example, the monetary incentives for participation in RDS may have had a much stronger appeal to the lower socio-economic status MSM than higher SES MSM75. Lastly, behavioral information relied on self-reporting, which might have been influenced by recall and social desirability biases.

Conclusions

MSM at high risk of HIV infection have moderate awareness of PrEP and low willingness to use PrEP. PrEP requires more promotion that focuses on at-risk MSM who have lower education, risky sexual behavior, and use sexualized drugs. Additionally, efforts should be made to reduce PrEP-related stigma and strengthen the training of healthcare providers and peer educators to improve the dissemination of PrEP knowledge.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Haijun Yue, Xingang Fan, and our partner organization (Na Mo community) for their assistance in recruiting participants as well as to all the members of the research team.

Author contributions

G.L., H.L., D.L., Y.S. conceived and designed the study. Y.S. did the statistical analyses, made the figures and wrote the first draft. G.L., H.L., J.Y. and D.L. checked and supervised the statistical analyses. All authors have reviewed the latest version of the manuscript and have approved its content.

Funding

This research was funded through resources provided by (1) Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (D171100006717002). Hongyan Lu received the award. http://kw.beijing.gov.cn/ (2) Cultivation Fund of Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Beijing Research Center for Preventive Medicine (No.2019-BJYJ-13). Yanming Sun received the award. https://www.bjcdc.org/ (3) China Capital's Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2022-1G-3011). Jingrong Ye received the award. http://www.bjhbkj.com:81/publogin.jsp. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dong MJ, et al. The prevalence of HIV among MSM in China: A large-scale systematic analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:1000. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4559-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, He S, Li Y, Lu H. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics of HIV/AIDS in Beijing. Capital J. Public Health. 2018;12:282–284. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of Prevention Strategies to Reduce the Risk of Acquiring or Transmitting HIV. (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/estimates/preventionstrategies.html#anchor_1562942347.

- 4.van de Vijver D, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget effect of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in Germany from 2018 to 2058. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1800398. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.7.1800398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cambiano V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men in the UK: A modelling study and health economic evaluation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30540-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols BE, Boucher CAB, van der Valk M, Rijnders BJA, van de Vijver DAMC. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in the Netherlands: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinner CD, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): A review of current knowledge of oral systemic HIV PrEP in humans. Infection. 2016;44:151–158. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AVAC. Country Updates. (2019). https://www.prepwatch.org/in-practice/country-updates.

- 9.Xu J, et al. Expert consensus on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in China. Chin. J. AIDS STD. 2020;26:1265–1271. [Google Scholar]

- 10.HIV/AIDS Hepatitis C Research Group of Chinese Medical Association of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (2021 edition) Chin. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;39:715–735. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W, et al. Awareness of and preferences for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among MSM at high risk of HIV infection in Southern China: findings from the t2t study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021;2021:6682932. doi: 10.1155/2021/6682932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng L, et al. Willingness to use and adhere to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:2620. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heckathorn DD. Respondent driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 2022;49:11–34. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckathorn DD. Respondent driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 1997;44:174–199. doi: 10.2307/3096941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris TG, et al. HIV care cascade and associated factors among men who have sex with men, transgender women, and genderqueer individuals in Zimbabwe: Findings from a biobehavioural survey using respondent-driven sampling. Lancet HIV. 2022;9:e182–e201. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin W, et al. Is the HIV sentinel surveillance system adequate in China? Findings from an evaluation of the national HIV sentinel surveillance system. Western Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2012;3:76–85. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2012.3.3.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for AIDS, STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention . National AIDS Sentinel Surveillance Implementation Program Operation Manual. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatib A, et al. Reproducibility of respondent-driven sampling (RDS) in repeat surveys of men who have sex with men, Unguja, Zanzibar. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:2180–2187. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1632-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gile KJ, Johnston LG, Salganik MJ. Diagnostics for respondent-driven sampling. J. R. Stat. Soc. A Stat. Soc. 2015;178:241–269. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, et al. The development of HIV/AIDS surveillance in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S33–S38. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304694.54884.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . Monitoring the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS: guidelines on construction of core indicators. UNAIDS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Zhang H, Xu J, Zhang G, Yang H, Fan J. Relations between self-discrimination of MSM and sexual behavior and psychological factors. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2010;44:636–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdul-Quader AS, et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: Findings from a pilot study. J. Urban Health. 2006;83:459–476. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto K, Cao M, Kuhns LM, Li D, Schneider JA. Statistical adjustment of network degree in respondent-driven sampling estimators: Venue attendance as a proxy for network size among young MSM. Soc. Netw. 2018;54:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, et al. A comparison between respondent-driven sampling and time-location sampling among men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China. Arch. Sex Behav. 2015;44:2055–2065. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0350-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, Kerr LR, Rifkin MR, Rutherford GW. Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4 Suppl):S105–S130. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirtz AL, et al. Comparison of respondent driven sampling estimators to determine HIV prevalence and population characteristics among men who have sex with men in Moscow, Russia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han J, et al. PrEP uptake preferences among men who have sex with men in China: results from a National Internet Survey. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25242. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in western China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:137–141. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou F, et al. Willingness to accept HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among Chinese men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draper BL, et al. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among gay men, other men who have sex with men and transgender women in Myanmar. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21885. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macapagal K, Kraus A, Korpak AK, Jozsa K, Moskowitz DA. PrEP awareness, uptake, barriers, and correlates among adolescents assigned male at birth who have sex with males in the US. Arch. Sex Behav. 2020;49:113–124. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-1429-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoagland B, et al. Awareness and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1278–1287. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim SH, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in Malaysia: Findings from an online survey. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, et al. Understanding willingness to use oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in China. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holloway IW, et al. Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in California. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31:517–527. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Storholm ED, et al. Gearing up for PrEP in the Middle East and North Africa: An initial look at willingness to take PrEP among young men who have sex with men in Beirut, Lebanon. Behav. Med. 2021;47:111–119. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1661822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mimiaga MJ, et al. Reactions and receptivity to framing HIV prevention message concepts about pre-exposure prophylaxis for Black and Latino men who have sex with men in three Urban US Cities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30:484–489. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolle CP, et al. Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young black MSM. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017;76:250–258. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolle CP, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black and White men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2017;28:849–857. doi: 10.1177/0956462416675095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baeten JM, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choopanya K, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thigpen MC, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mijiti P, et al. Awareness of and willingness to use oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples: a cross-sectional survey in Xinjiang, China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui Z, et al. Low awareness of and willingness to use PrEP in the Chinese YMSM: An alert in YMSM HIV prevention. HIV Med. 2021;22:185–193. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garnett M, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Franks J, Hayes-Larson E, El-Sadr WM, Mannheimer S. Limited awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York city. AIDS Care. 2018;30:9–17. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1363364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iniesta C, et al. Awareness, knowledge, use, willingness to use and need of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) during World Gay Pride 2017. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankis J, Young I, Flowers P, McDaid L. Who will use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and why?: Understanding PrEP awareness and acceptability amongst men who have sex with men in the UK–A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edmundson C, et al. Sexualised drug use in the United Kingdom (UK): A review of the literature. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2018;55:131–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurtz SP. Post-circuit blues: Motivations and consequences of crystal meth use among gay men in Miami. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2019;63:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Mo PKH, Ip M, Fang Y, Lau JTF. Uptake and willingness to use PrEP among Chinese gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men with experience of sexualized drug use in the past year. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:299. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hibbert MP, Brett CE, Porcellato LA, Hope VD. Psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with sexualised drug use and chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. Sex Transm. Infect. 2019;95:342–350. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2018-053933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan KE, et al. Implications of survey labels and categorisations for understanding drug use in the context of sex among gay and bisexual men in Melbourne, Australia. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2018;55:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, et al. A mathematical model of biomedical interventions for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18:600. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3516-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schueler K, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and use within high HIV transmission networks. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1893–1903. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taggart T, Liang Y, Pina P, Albritton T. Awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among Black and Latinx adolescents residing in higher prevalence areas in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prati G, et al. PEP and TasP awareness among Italian MSM, PLWHA, and high-risk heterosexuals and demographic, behavioral, and social correlates. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koblin BA, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis awareness, knowledge, access and use among three populations in New York City, 2016–17. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2718–2732. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oldenburg CE, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2015;29:837–845. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sullivan PS, Mena L, Elopre L, Siegler AJ. Implementation strategies to increase PrEP uptake in the South. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnold T, et al. Social, structural, behavioral and clinical factors influencing retention in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) care in Mississippi. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calabrese SK, Underhill K. How stigma surrounding the use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis undermines prevention and pleasure: A call to destigmatize "Truvada Whores". Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105:1960–1964. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang J, et al. Preference for daily versus on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and correlates among men who have sex with men: The China real-world oral PrEP demonstration study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021;24:e25667. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Golub SA. PrEP stigma: Implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mehta SA, Silvera R, Bernstein K, Holzman RS, Aberg JA, Daskalakis DC. Awareness of post-exposure HIV prophylaxis in high-risk men who have sex with men in New York City. Sex Transm. Infect. 2011;87:344–348. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pande G, et al. Preference and uptake of different community-based HIV testing service delivery models among female sex workers along Malaba-Kampala highway, Uganda, 2017. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19:799. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4610-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zablotska IB, et al. Australian gay men who have taken nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis for HIV are in need of effective HIV prevention methods. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011;58:424–428. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230e885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holland CE, et al. Access to HIV services at non-governmental and community-based organizations among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Cameroon: An integrated biological and behavioral surveillance analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abubakari GM, et al. HIV education, empathy, and empowerment (HIVE(3)): A peer support intervention for reducing intersectional stigma as a barrier to HIV testing among men ho have sex with men in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:13103. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoff CC, et al. Attitudes towards PrEP and anticipated condom use among concordant HIV-negative and HIV-discordant male couples. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:408–417. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Schneider J, Garofalo R, Fujimoto K. Use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in young men who have sex with men is associated with race, sexual risk behavior and peer network size. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1376–1382. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1739-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kudrati SZ, Hayashi K, Taggart T. Social media & PrEP: A systematic review of social media campaigns to increase PrEP awareness & uptake among young Black and Latinx MSM and women. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:4225–4234. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kendall C, et al. An empirical comparison of respondent-driven sampling, time location sampling, and snowball sampling for behavioral surveillance in men who have sex with men, Fortaleza, Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.