Abstract

Aims

To identify barriers and facilitators to nursing care of individuals with developmental disabilities (DDs).

Background

Individuals with DDs experience health disparities. Nurses, although well positioned to provide optimal care to this population, face challenges.

Design

Narrative review of extant published peer‐reviewed literature.

Data Sources

Electronic databases, ProQuest and EBSCO, were searched for studies published in English between 2000 and 2019.

Review Methods

Three reviewers reviewed abstracts and completed data extraction. Knowledge synthesis was completed by evaluating the 17 selected studies.

Results

Emerging themes were: (1) barriers and challenges to nursing interventions; (2) facilitators to nursing care; and (3) recommendations for nursing education, policy and practice.

Conclusion

Nursing has the potential to be a key partner in supporting the health of people with DDs.

Impact

There is a need for specific education and training, so nurses are better equipped to provide care for people with DDs.

Keywords: developmental disabilities, health disparities, narrative review, nurses, nursing care, nursing competencies, nursing education

1. INTRODUCTION

Nurses have the potential to contribute statistically significantly to the health of individuals with developmental disabilities (DDs) in acute care, community settings and school settings. Yet, there are few nursing interventions and best practice guidelines focussing on nursing care for people with DDs. This leaves an important gap in our knowledge and practice of nursing care for people with DDs. Moreover, there are wide variations in nursing education and care in developmental disabilities internationally; for example, in the United Kingdom Learning Disabilities Nursing education is offered at the university level and the role of Learning Disability Nurse exists, but there are no similar parallels in Canada. This leads to unequal pathways of nursing care across settings.

Individuals with developmental disabilities experience a constellation of health problems complicated by absence of inclusive health promotion, accessible health care and inequitable distribution of social determinants of health (Marks & Sisirak, 2017). Research from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia has highlighted that people with DDs are poorly supported by healthcare systems and services (Fisher, 2004; Krahn et al., 2006; Scheepers et al., 2005; Sullivan et al., 2011). Providing optimal care for this population is often perceived by healthcare professionals as difficult because of clients' disability‐related social, environmental, cultural, cognitive, behavioural and communication needs (Cheak‐Zamora & Teti, 2015; Raemy & Paignon, 2019). Nurses working in healthcare settings, community settings and school settings have reported gaps in education and training to address the complex and varied needs of people with DDs (Betz, 2007; Fisher et al., 2020; Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016; Raemy & Paignon, 2019; Singer, 2013; Weiss et al., 2010). It is important that nursing care for persons with developmental disabilities be enhanced and standardized with a concentrated focus through nursing education and research.

1.1. Background

Developmental disabilities can encompass limitations in multiple aspects of functioning, including in intellectual capacity (intellectual and executive functioning), adaptive skills (impairments in language and communication, behavioural, emotional regulation) and physical functioning. These limitations begin in childhood and are usually life‐long affecting areas of major life activity including ability to self‐care and live independently as adults (CDC, 2017; Services and Support to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008, S.O. 2008, c. 14, 2019). DDs include neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, intellectual disabilities and cerebral palsy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Thapar et al., 2017). The 2017 Canadian Disability Survey (Morris et al., 2018) reports one in five (22% or 6.2 million people) Canadians (15 years and older) live with one or more disabilities (e.g., mental health, mobility, flexibility, mobility and pain impairment), and 315,470 (or 1.12%) Canadians lived with a DDs. In just five years the number of individuals (15 years and older) with a DDs has almost doubled; in 2012, about 160,500 persons lived with a DDs (Arim, 2015) and in 2017 approximately 315,470 persons reported living with a DDs (Statistics Canada, 2020).

Compared to the general population young people with DDs experience more comorbid conditions (Schieve et al., 2012) and have a greater onset of chronic health conditions and higher rates of morbidity in later life (Hamdani & Lunsky, 2016; Thomas et al., 2011). They also face difficulties in self‐management of health (Cheak‐Zamora & Teti, 2015), adhering to treatment (Cooper et al., 2006), voicing their care concerns (Boylan & Ing, 2005) and have reduced capacity to manage challenging situations such as loss and separation from family (Janssen et al., 2002; Tyrer et al., 2006). Health inequities further prevent young adults with DDs from accessing health resources (Emerson et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2019; Marks et al., 2008) and affordable healthcare and mental healthcare services (Crane et al., 2019).

Nurses are well positioned to provide direct and coordinated optimal care to individuals with DDs at all healthcare levels (Giarelli & Gardner, 2012; Mandal et al., 2020) but are not fully equipped to take on this active care role (Anderson et al., 2013; Cieza, 2015). Nurses have reported difficulties in providing care for individuals with DDs due to their clients' communication, social, cognitive, behavioural and physical impairments (Hahn, 2003; Smeltzer et al., 2012). More than ever before the number of individuals with DDs needing health care has increased in acute care, primary care, long‐term care and in the community (Harris‐Kojetin et al., 2016). Without targeted nursing education and training focussed on appropriate and effective health care for people with DDs, who experience a wide range of barriers and life‐stage specific healthcare needs, nurses will encounter increasing challenges in providing high‐quality care tailored to the specific individual needs of clients with DDs (Chiri & Warfield, 2012; Gardner et al., 2016; Giarelli & Gardner, 2012; Johnson et al., 2012). In this paper we present findings from a review of published peer‐reviewed literature on effective training and education approaches for nurses caring for persons with DDs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Aim

Our overall aim was to identify the barriers and facilitators to nursing care of individuals with DDs and provide recommendations. The main objectives of our review were to identify:

Research evidence on nursing strategies and interventions for health promotion and health care of individuals with DDs;

Knowledge gaps in nursing care that promote the health of individuals with DDs; and

The barriers and facilitators to nursing interventions in care of people with DDs.

2.2. Design

We used a narrative literature review approach (Green et al., 2006) to address the issue of how to better prepare nurses to practice quality care of people with DDs. Narratives reviews, also known as unsystematic narrative reviews, are not meant to be systematic or comprehensive searches of all relevant literature on an issue (Davies, 2000). They are used to present a broad perspective and narrative syntheses of previously published information on an identified issue and recommendations to address an issue (Green et al., 2006) and to discuss a theoretical point of view (Bernardo et al., 2004). Narrative reviews have been used as educational tools in the continuing medical education field (Bernardo et al., 2004).

2.3. Search methods

Peer‐reviewed literature published from January 2000 up to January 2019 were reviewed to assess the knowledge on nursing strategies and health promotion interventions for individuals with DDs.

2.4. Literature search strategy

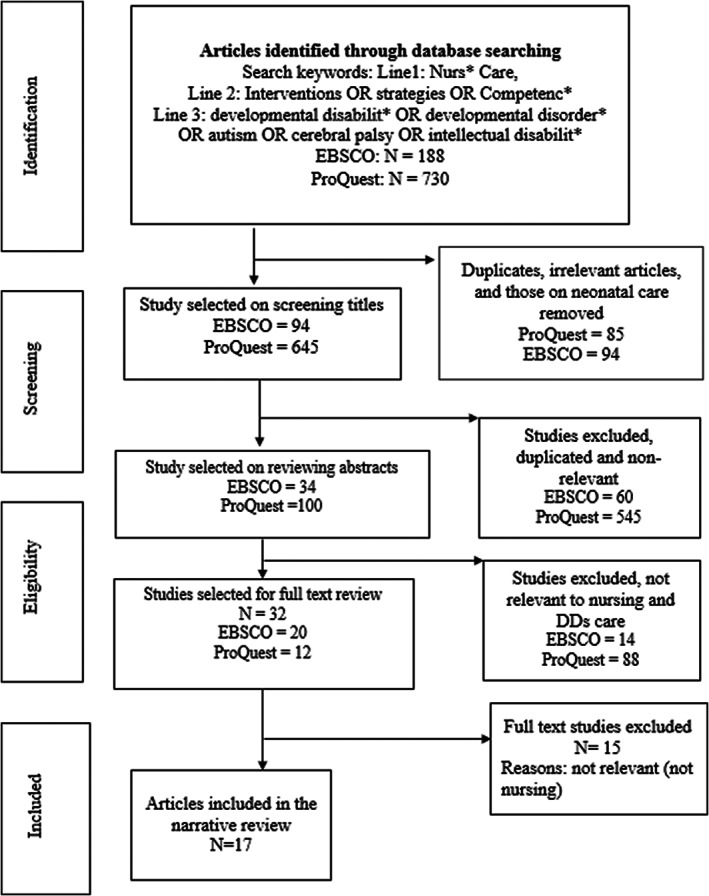

A librarian specialized in health literature searches was consulted to assist with the development of the search strategy. The search was conducted using two electronic databases: ProQuest (included all databases) and EBSCO (included all databases), which focus largely on nursing literature. We used the following search terms: Line1: Nurs* Care; line 2: Interventions OR strategies OR Competenc*; and line 3: “developmental disabilit*” OR “developmental disorder*” OR autism OR “cerebral palsy” OR “intellectual disabilit*” across all databases. Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy undertaken. Two reviewers (2nd author and a research personnel) ran the data base searches and selected articles that met eligibility criteria. All types of studies (including reviews and case studies) that focussed on nursing strategies and health promotion interventions for children, youth, elders and adults with DDs in Canada, USA, UK, Australia and New Zealand were included given their similarities in English language and economies. Studies that did not focus on nursing care of individuals with DDs care and not situated in Canada, USA, UK, Australia and New Zealand were excluded. The initial title search yielded 94 studies from EBSCO and 645 studies from ProQuest databases. After duplicate and non‐relevant studies were excluded 34 studies were selected from EBSCO and 100 from ProQuest for abstract review. Three reviewers (2nd author and two research personnel) reviewed the abstracts for selection of articles for full text review. The involvement of the third reviewer was to help resolve disagreements. They discussed the selected articles after re‐reviewing inclusion and exclusion criteria and disagreements resolved till consensus was reached on selected studies.

FIGURE 1.

Literature review search strategy

2.5. Search outcomes

The PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy for the narrative review from initial identification to selection of eligible studies. A total of 32 studies (12 studies from ProQuest and 20 from EBSCO) were selected for full text review by two reviewers (2nd author and last author). Among these 17 selected articles met the eligibility criteria for the narrative review. The excluded articles did not focus on nursing strategies on the care of individuals with DDs. Those focussing on neonates with DDs were also excluded.

2.6. Quality appraisal

The researchers consulted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews statement (Tricco et al., 2018) as a guidance for a thorough examination of the literature and in the limits of a narrative review that does not require a quality appraisal of studies, appraisal of the process and audit of discarded studies. To ensure credibility of studies, the review incorporated several elements of a systematic review including: (1) enhanced reliability by employing three researchers to review the abstracts and full text studies, and then compare/ contrast selected studies, and extracted information. Further, the knowledge synthesis was reviewed by all authors; and (2) using a pre‐defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to select or discard studies. For example, studies were excluded if they did not focus on nursing care of individuals with DDs care, or examined nursing care of neonates with DDs, or were in countries other than Canada, USA, UK, Australia and New Zealand. The limits of narrative summary in assessing quality of studies have been further discussed in the limitations section.

2.7. Data abstraction and synthesis

Data was extracted onto an Excel file. Discrepancies between the reviewers were discussed and resolved. The specific study characteristics gathered included study goals, research design, description of participants and type of disability, tools and strategies used, and study recommendations. The results of individual studies were then analysed iteratively by two authors to determine major themes in relation to issues, tools, strategies and recommendations. Table 1 presents summary of the characteristics of each study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies

| References and year | Study aim and objectives | Research design | Location and study participants | Type of disability | Tools, strategies used | Findings and challenges | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review studies | |||||||

| 1. Balakas et al. (2015) | To develop an adaptive care plan (ACP) and screening tool for patients with challenging behaviours as an intervention to improve the surgical experience for the children and their families | Review of published studies on screening tools and examining those from two other hospitals |

|

DD |

|

|

|

| 2. Betz (2007) | To review salient issues that adolescents with DDs face as they transition to adulthood | Literature review |

|

All DDs including ID |

|

|

|

| 3. Cockburn‐Wells (2014) | To review the literature on the causes and effects and management of constipation among people with severe learning disabilities | Literature review |

|

Learning disabilities |

|

|

|

| 4. Friese and Ailey (2015) | To describe a programme developed to support nursing care for specific standards of care for people with ID | Standards program review |

|

People with ID and DD |

|

|

|

| 5. McIntosh et al. (2018) | To explore school nurses increasing the compliance of hygiene routines for students with autism spectrum disorder | Literature review |

|

Children with ASD |

|

|

|

| 6. Sheerin (2008) | To identify the diagnoses and interventions that are employed by intellectual disability nurses | Review of professional literature |

|

Developmental disabilities, learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities |

|

|

|

| Quantitative studies and case studies | |||||||

| 7. Drake et al. (2012) | To evaluate the nurse's perception of the effectiveness of a coping kit intervention for children with DDs at increased risk for challenging behaviours | Quantitative study post‐test design |

|

Children and youth with DDs including ASD, Down syndrome, neurological condition and other DDs |

|

|

|

| 8. Kirby and Hegarty (2010) | To examine proficiency, motivation and knowledge about breast cancer screening and awareness of nurses working in an Intellectual Disability setting. Additionally, the study aimed to examine and establish associations between nurses' personal and professional breast awareness practices | Quantitative descriptive design study |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Melville et al. (2005) | To measure the attitudes, knowledge, training needs and self‐efficacy of practice nurses in their work with people with Intellectual disability | Cross sectional study |

|

ID |

|

|

|

| 10. Scarpinato et al. (2010) | To explore the challenges that patients with ASD face when hospitalized and to provide assessment strategies and plan‐of‐care suggestions for nursing caregivers | Clinical case studies and scientific literature evidence |

|

ASD |

|

Not specified |

|

| Qualitative studies | |||||||

| 11. Halpin and Nugent (2007) | To identify generic health visitors' perceptions of their role with families where children may have ASD | Small‐scale qualitative inductive study |

|

ASD | Interviews | Participants felt:

|

|

| 12. Hemsley et al. (2012) | To investigate nurses' expressed concepts of “time” in stories about communicating with patients with DDs and complex communication needs in hospital | Qualitative study |

|

DD and complex communication needs |

|

|

|

| 13. Macdonald et al. (2018) | To explore perceptions and experience of nurses delivering an anticipatory health check for adults with ID | Nested qualitative study in an RCT |

|

ID |

|

|

|

| 14. Narayanasamy et al. (2002) | To analyse how nurses caring for people with learning disabilities respond to clients' spiritual needs | Qualitative approach incorporated the critical incident technique |

|

Learning disability |

|

|

|

| 15. Ndengeyingoma and Ruel (2016) | To explore nurses' representations of caring for people with ID, intervention strategies they currently use, and to identify needs to ensure quality care | Qualitative descriptive study |

|

ID |

|

|

|

| 16. Singer (2013) | To explore the perceptions and challenges of school nurses working with students with intellectual and DDs | Qualitative study | Public schools (elementary and high school) in Northeast part of the United States

|

Students with intellectual and DDs |

|

|

|

| 17. Zwaigenbaum et al. (2016) | To explore the perspectives of health professionals (doctors and nurses) caring for children with ASD in the emergency department and to determine the strategies to optimize care | Qualitative study, grounded theory design |

|

Children with ASD under 18 years | Interview guide collected data on doctors and nurses experiences providing care to the child with ASD in ED encounters, factors challenged and facilitated effective care, strategies or recommendations based on current or past experiences to improve ED care for children with ASD and their families |

|

|

Note: Study participant is defined as an individual who participates in the study or a person on or in respect of whom any study activities are performed. Tools refers to how data was collected and strategies to the interventions. In the United Kingdom “learning disabilitys” refers to ID.

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DD, developmental disability; DDs, developmental disabilities; ED, emergency department; ID, intellectual disability; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

3. RESULTS

Among the 17 eligible studies, six were qualitative, one was mixed methods (nested qualitative study in a randomized controlled study), three were quantitative (two descriptive and one interventional study), one was a clinical case study, and five studies were literature reviews, and one was a program review. The themes identified from our literature review have been organized by overarching themes as: (1) Barriers and challenges to nursing interventions in care of people with DDs; (2) facilitators to nursing care in promoting the health of individuals with DDs; (3) and emerging recommendations for nursing education, policy and practice.

3.1. Barriers and challenges to nursing interventions in care of people with DDs

Our narrative review found nurses experienced overlapping health systems‐based challenges to providing optimal care to people with DDs, which included time constraints and insufficient staffing, communication challenges and insufficient education and training.

3.1.1. Time constraints and insufficient staffing

Nurses reported time constraints in providing accommodations and having additional responsibilities when caring for people with DDs that may include undertaking health checks, providing compassionate care and relaying health information to clients and their caregivers on medical procedures and examination (Ford, 2020; Hemsley et al., 2012). Due to time constraints nurses often avoided direct communication with the patient and depended more upon family carers for communication about procedures and treatment (Hemsley et al., 2012). Not interacting with patients with DDs hindered the development of effective relationships between nurses and their clientele. Shortage of time was also noted to be a barrier to conducting periodic health checks of individuals who have DDs. These comprehensive health assessments, conducted as preventive and diagnostic measures, in primary‐care clinics have been shown to be beneficial for health of people with DDs. The health checks for one patient with DDs typically took 48 min to carry out (Macdonald et al., 2018). The time required to administer the health check was centred around the operational impact on how this intervention impinged on nurses' everyday workload and practice particularly if dealing with larger numbers of patients (Macdonald et al., 2018). Ndengeyingoma and Ruel (2016) identified that nurses had insufficient time to intervene adequately in situations concerning people with DDs in the emergency room and hospital ward, particularly when care was urgent. Patients with DDs required more time for communication for gathering medical histories for their needs to be specified and procedures to be explained (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). Patients with DDs often need more time explaining but, as time is limited, they may feel rushed and not fully absorb the information, which may cause elevated emotions that they have challenges dealing with (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). Thus, rushing urgent care prevented organized care and led to inadequate care approaches, such as use of restraints and sedative medication to prevent injury to clients (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016).

Insufficient staffing magnified the problems associated with managing people with DDs. Nurses reported that because of insufficient staffing providing people with DDs the necessary accommodations were challenging (Macdonald et al., 2018). The nurse—patient ratio did not allow nurses to allocate more time to patients with DDs, thereby respecting their varied needs (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). Nurses were expected to closely monitor and manage patients with DDs concurrently with their regular duties without any reduction in workload. Moreover, during night shifts fewer healthcare providers knowledgeable in ASD were available (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). In the emergency department nurses were under constant stress to complete tasks and procedures and their anxiety was heightened when caring for a child with DDs (Drake et al., 2012).

3.1.2. Communication challenges

Nurse reported communication challenges with individuals with DDs, their caregivers and care staff including other nurses, healthcare providers and multidisciplinary teams (Melville et al., 2005). For example, in healthcare settings, because of difficulties managing communication challenges with people with DDs, nurses had difficulty responding to their patient's needs and explaining the intervention or procedure (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). Families believed that nurses deliberately avoided communication. They perceived this as a negative and discriminatory attitude towards their family members with DDs, which impacted the quality of hospital care their family members with DDs received.

Enhanced communication when caring or supporting people with DDs is crucial at all levels of health care (Hemsley et al., 2012). In the emergency department nurses had to pay close attention to the non‐verbal cues of children with DDs, specifically those with limited verbal ability (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). In the absence of a family caregiver/ parent, the experts on their child's needs, preferences and aversions, the use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) (including gesture or signing systems, interpreters, communication boards or speech generating devices) by persons with DDs to share their needs reduced nurses guessing their needs and was also more comfortable for the patients (Hemsley et al., 2012). Nurses believed that investing time in learning skills in communication would lead to better assessment, and ultimately save time (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). In hospital settings at shift change communication between nurses were typically not sufficient to convey and comprehend information about patients with DDs' medical condition, behaviour, routines and functional abilities in activities of daily living, such as eating preferences (Friese & Ailey, 2015). Communication was hampered by time constraints, and by level of comfort between the nurses and person with DDs (Singer, 2013). In school settings nurses experienced communication challenges with students with DDs, who were not able to articulate their needs. Nurses had difficulty explaining procedures to them and making accurate assessments. Moreover, they were unable to assess if the student had understood their instructions, because not being provided the baseline information on the Individualized Education Program (IEP) they could not assess the developmental levels of their students (Singer, 2013).

3.1.3. Insufficient education and training on supporting individuals with DDs

Nurses tended to be more comfortable if they had previous experience caring for patients with a disability and/ or became familiar with persons with DDs over time (Singer, 2013). Several studies have shown that education and training on disability provided in nursing schools and during continuing education and professional career development were insufficient. A United Kingdom based study on the training needs of primary health care nurses (N = 201) found 86% of practice nurses had communication difficulties during appointments with people with DDs and only 8% of had received training in communicating with this clientele (Melville et al., 2005). In another study nurses in Ireland promoting breasts awareness programs were found to have limited knowledge of women with DDs' cognitive functioning and communication abilities (Kirby & Hegarty, 2010).

Professional development programs to educate nurses on specialized health care for children and adults with DDs' diverse needs were found to be insufficient. Registered Nurses in the United Kingdom with additional training in community public health, also known as Health Visitors, had difficulty identifying the health needs of children with ASD and providing them ongoing support because they lacked education and training on the care of people with ASD (Halpin & Nugent, 2007). Similarly, care staff for adults with severe DDs living in supported accommodation did not have any specialist knowledge in the care of people with DDs, including the risks associated with constipation, a common ailment in this clientele (Cockburn‐Wells, 2014). On a similar note, nurses with several years of nursing experience who transitioned to school nurses had not received any orientation on students with DDs nor were they included in training or staff meetings about this clientele (Singer, 2013). Thus, the school nurses encountered difficulties with communication, screenings and completing health assessments of these students (Singer, 2013).

A study from Quebec, Canada, noted that hospital nurses' learning needs were informational in nature and relational to best practice intervention strategies, ensuring consistent high‐quality personalized care to individuals with DDs (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). The strategies included nurses' ability to recognize features of DDs, identify their clients' needs, and organize the continuity of care. The 18 nurses who participated in the study reported that they did not feel confident about their ability to recognize the characteristics of DDs if a patient presented with the condition. They also were unable to recognize the complex needs of patients with DDs and as a result their clinical evaluations of their patients were often incomplete (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). Health visitors working with families of children with ASD felt they: did not have adequate expertise in child development; lacked competence in their role in identifying children who might have ASD; and would attend training on ASD if offered (Halpin & Nugent, 2007). Registered Nurses at a children's hospital participating in a study examining the effectiveness of a coping kit to manage challenging behaviour in children with DDs, including ASD, reported programs that can train nurses in behaviour management skills were often unavailable in their work settings (Drake et al., 2012). Inadequate training and limited resources (such as time constraints) can heighten nurses' challenges in providing care and support of children with DDs (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Findings from a study examining the use of an evaluation tool (the Adaptive Care Screening Tool) to prepare children with DDs for surgery showed that developing a multidisciplinary team and re‐educating the clinic staff were essential for effective perioperative care for this clientele (Balakas et al., 2015).

Kirby and Hegarty (2010) found all grades of nurses (n = 200) in Southern Ireland experienced challenges in promoting breast awareness and screening for women with DDs. Nurses reported inadequacy in their skills on breast self‐examination, uncertainty in their proficiency in the detection of breast anomalies, and difficulties addressing legal and ethical issues, and obtaining consent from women with DDs.

3.2. Facilitators to nursing care in promoting the health of individuals with DDs

Our review identified several factors, which facilitated nurses in providing enhanced care to people with DDs. These include the use of tools and focussed resources, nursing strategies to manage challenging behaviours and using strategies that improve collaboration with family caregivers and healthcare teams.

3.2.1. Tools and focussed resources for nursing care of individuals with DDs

The need for a comprehensive “health service model” to support the psychosocial, medical and educational/ vocational needs of adolescents with DDs in their transition from child‐focussed to adult‐focussed healthcare system in the United States of America (USA) has been identified (Betz, 2007). Nurses must have knowledge of their client's transitional needs, so they can develop a youth‐centred transition plan along with members of the school's IEP team that addresses their comprehensive health needs (Betz, 2007). The USA based IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 1 ) model of assessment to nursing practice allows nurses, with facilitated verbal input of youth with DDs and their caregivers, to identify interests, needs and preferences of transitioning youth for the future, and to develop a transition plan aligned to the youth's goals in the areas of health care, training, employment and community living (Betz, 2007). On the same note, school nurses suggested that access to standardized assessment tools and more education on assessment would help their practice and to providing better health care to students with DDs (Singer, 2013).

Focussed resources can support and enhance consistency of nursing care and contribute to a safer environment for both nurses and their patients with DDs (Scarpinato et al., 2010). A study examining the benefits of nurse conducted routine health checks in the primary care of people with DDs (the intervention), versus standard health care, found the intervention was most successful with patients whose problems or issues were recognized by nurses, and that further training of nurses would maximize potential benefits for the patients (Macdonald et al., 2018). A written critical incident technique in the United Kingdom helped nurses to pick up cues from their clients with DDs about their religious beliefs and practices and to formulate care plans using a client‐centred approach. This approach helped to identify emotional tensions and turmoil and provide clients the appropriate counselling support to address their spiritual needs (Narayanasamy et al., 2002).

3.2.2. Nursing strategies to manage challenging behaviours

It can be particularly difficult for nurses to provide essential care and treatment for people with DDs with challenging behaviours (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). The unfamiliar setting of the emergency department, the “hustle and bustle”, noise and being seen by multiple unfamiliar health care providers can be disturbing for a child with ASD and cause statistically significant stress and anxiety for people with DDs. Further, negative experiences at the hospital or health care visit can potentially impact the behaviour of child's future visits (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). In addition, the increased sensitivity to touch of some people with DDs makes it more difficult for nurses to complete clinical examination and diagnostic procedures.

Nurses in healthcare and school settings can adopt techniques to calm children and youth with DDs' behaviour and improve treatment delivery (Drake et al., 2012; McIntosh et al., 2018). Optimizing the environment (Singer, 2013) by incorporating “warming up” techniques, moving slowly through procedures and using distraction techniques (e.g., TV, toys and video games) can potentially provide a more positive experience for a child with ASD (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016) and also make patients with DDs feel calm and less frightened (Friese & Ailey, 2015). Changing the environment (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016), using proactive strategies (such as creativity, sensitivity and awareness) and coping kits can potentially alleviate anxiety and increase cooperation in the hospitalized child with ASD (Drake et al., 2012). These strategies help to reduce, prevent and manage challenging behaviours at initiation of every health care visit (Friese & Ailey, 2015). While working with families of children with DDs, availing the parents' expertise reaped increased care benefits (Drake et al., 2012).

The Adaptive Care Plan (ACP) was developed in USA hospitals to improve the surgical experience of children and adolescents with DDs and their families and to manage patients' challenging behaviours (Balakas et al., 2015); it provided nurses an opportunity to learn more about children and adolescents with DDs in their care and to alert them to the child's specific needs. The ACP focussed on several aspects of care including improving the care environment and staffing, educating staff, enhancing communication with clients and increasing parental involvement (Balakas et al., 2015). The ACP also provided guidance on developing and training multidisciplinary team for care of children with DDs (Balakas et al., 2015).

The use of “extrinsic motivation and reinforcement techniques” helped school nurses to promote compliance of hygiene routines for students with ASD (McIntosh et al., 2018). These techniques reduced and managed unwanted attention seeking behaviours in children with ASD. The “give‐get exchange method” used positive reinforcement (such as using verbal praise or gifting candies, stickers or allowing company of favourite toy or person) to motivate the child to do something (McIntosh et al., 2018). Other methods included giving clear, honest explanations paired with a visual aid of what is expected of the child and offering a simple choice. For example, the use of social stories 2 to make children with DDs more calm and less frightened for procedures improved patients' cooperation when care was being provided and reduced behavioural disruptions in hospitals (Friese & Ailey, 2015; Kokina & Kern, 2010). Similarly, in school settings social stories reduced unwanted behaviour and prompted children with ASD to complete essential tasks (McIntosh et al., 2018).

3.2.3. Collaborating with nursing staff, healthcare teams and family caregivers

Family caregivers can be a key resource for the patient with DDs and the healthcare team including nurses (Balakas et al., 2015). Parents' involvement and the support of multidisciplinary team was key in the development and implementation of the ACP screening tool (Balakas et al., 2015). Parents have unique knowledge about their child's likes and dislikes, and what strategies to adopt to help calm their child and, therefore, are essential for care delivery in the emergency department (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016). Showing positive regard to family caregivers for their role and knowledge about the person with DDs' health, medical history, needs and behaviour and communicating with caregivers about type of accommodations that might be beneficial for their child with DDs proved fruitful (Friese & Ailey, 2015; Halpin & Nugent, 2007). Families and caregivers require ongoing support as they are integral to the wellbeing of people with intellectual disabilities (Halpin & Nugent, 2007). While caregiving is a huge physical and psychological burden and can adversely affect caregiver's ability to provide effective care, involving parents in providing a calming environment and training teamwork and collaboration can facilitate nursing care (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016).

By coordinating care with formal care systems and residential placement facilities nurses can support the care of youth with DDs transitioning between inpatient treatment and healthy living in the community (Ndengeyingoma & Ruel, 2016). The community DDs nurses (as transformational leaders) can play a vital role to reduce care deficiencies by coordinating holistic care and encouraging caregivers not having specialist knowledge of certain conditions (Cockburn‐Wells, 2014). A holistic approach involving improvements to adults with DDs' (living in supported accommodation) diets and lifestyles, such as exercise, and improving caregivers' understanding of the risk factors (for example, constipation), is recommended (Cockburn‐Wells, 2014). Shortfalls in collaboration among educational staff and nursing staff at schools pertaining to students on IEPs resulted in heavy reliance of school nurses on classroom staff for assistance on information on students with IEPs (Singer, 2013).

3.3. Emerging recommendations for nursing education, policy and practice

Table 2 summarizes six recommendations emerging from our review for education, policy and practice. These recommendations align with the guiding principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2016) and the Accessible Canada Act Bill C‐81 (2019), which promote the full and equal participation of persons with disabilities in society. The recommendations emphasize that all nurses must be equipped with education and training to have the ability and tools to identify and conduct assessments of clients who have DDs, to apply alternative communication methods, including assistive technology and apply approaches to communicate and collaborate with parents. The findings further highlight the need for employing a nursing quality and performance improvement plan that focuses on increasing the understanding of the unique needs of individuals with DDs, improving communication between clients with DDs, their families and staff.

TABLE 2.

Recommendations for education, policy and practice on nursing strategies and health promotion interventions

| Recommendations from studies | Recommendations from review | Cited in | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to better and more information for nurses |

|

|

|

| Education and training for nurses, staff and multidisciplinary team |

|

|

|

| More collaboration between families, health professionals and staff |

|

|

|

| Improving informal communication and interaction with patients |

|

|

|

| Promoting use of standardized assessment tools |

|

|

|

| Creating a safe environment |

|

|

Nurses play a vital role in inter‐professional healthcare teams, supporting and advocating for clients and their families. The revised Canadian Consensus Guidelines for primary care of adults with intellectual and DDs provide recommendations and appropriate modifications to standard practice to enable family physicians and primary‐care providers improve primary‐care and health outcome of this clientele (Sullivan et al., 2018). Furthermore, tools to support primary‐care providers implement these guidelines have been developed (Surrey Place, 2020). These tools promote preventive care easily overlooked in individuals with DDs, such as immunization, screening and medication reviews. However, in Canada (where we the authors of this review are situated) evidence‐based nursing training and education on providing nursing care for this population are much needed and could have a statistically significant impact on healthcare system change in support of effective and high‐quality nursing care for people with DDs.

4. DISCUSSION

As brought to light by our review and reported by other researchers in the DDs field, multiple challenges impede effective nursing care of people with DDs, including communication barriers (Chew et al., 2009; Ee et al., 2021), limited time to complete tasks that require more time, dearth of staffing with the needed skill mix (Beeber et al., 2014), inadequate education and training on managing individuals with DDs (Ee et al., 2021) and need for more involvement of parents and nurses working with other professionals (Law et al., 2003) including behaviour therapists, occupational therapists (Hines et al., 2019) and speech language pathologists (Auert et al., 2012) when supporting persons with autism. Thompson and colleagues (2008) report similar findings that nurses' busyness impacted their ability to provide complete nursing care and to find or use resources. Moreover, busyness caused emotional and physical strain and sacrifice of nurses' personal time (Thompson et al., 2008).

The highest importance in the training of healthcare professionals working with people with developmental disabilities is situated in the professionals' competence experiences and comfort (Smith et al., 2021). Curricular changes (at educational institutions) are required so nurses are better equipped to take on this very important role. These include providing nurses educational and training resources and using a multi‐level and multidisciplinary approach to capacity‐building. Although developments, such as the model of specialist nursing care in United Kingdom have been observed, transformation on the education, training and recruitment of nurses in the care of people with developmental disabilities is much needed in other countries (Wilson et al., 2022).

The complexity of providing nursing care to individuals with DDs can be further addressed through organizational and workforce development. The World Health Organization emphasizes that to address health disparities it is essential to enhance the development of human resources, such as nursing workforce, which can improve access to services and supports for marginalized and vulnerable populations (e.g., individuals with DDs) (World Health Orgnization, 2016). This review has made visible the challenges and barriers in providing nursing care to people with DDs, the need for support in nursing training and education in the DDs field, and collaborative and organizational approaches to enhance nursing care. Our review further underscores that nursing interventions/ strategies for people with DDs are underdeveloped, with few practice guidelines available and developed. There is also a scarceness of research examining the effectiveness of nursing interventions to improve health outcomes and health care access for people with DDs.

A multidisciplinary and team‐oriented approach is important. For example, health professionals such as behaviour therapists are key in supporting autistic persons. They are educationally prepared to assist nurses in understanding the appropriate techniques to mitigate challenging behaviours observed in autistic persons. Parents are also key in supporting autistic persons and learning the appropriate mitigating behaviour techniques. Behaviour therapists train and educate parents in those techniques and work with them either in the home, or now via Zoom and virtual media.

4.1. Differential impact of the pandemic on persons with DDs

Our narrative review focussed on published literature prior to the pandemic, given the statistically significantly different pre‐pandemic health context. However, it is prudent to note the impacts of the ongoing pandemic on persons with DDs. The current COVID‐19 pandemic has magnified the gaps and disparities in health outcomes of vulnerable populations around the world. Growing evidence indicates that marginalized populations are at an increased risk of COVID‐19 related morbidity and mortality outcomes. People with mental health and developmental disabilities face multiple social and economic barriers, which further exacerbate risks to their health. There is evidence that rates of complications and death due to COVID‐19 infection have been higher among people with DDs than in the rest of the population (Shapiro, 2020) especially for those living in residential settings (Landes et al., 2021).

Pandemic‐related directives such as self‐isolation and physical distancing and intermittent provision of health care and services (Armitage & Nellums, 2020) and medical rationing (Andrews et al., 2020) have impacted this population more than the general population. Developmental disabilities nurses dedicated more time assisting people with varying DDs (and their families) in understanding and coping with the pandemic‐related social changes such as social distancing, not having visitors, changes in daily routine, not being able to attend day programs (Desroches et al., 2021). Most importantly, the pandemic has exposed that level of skilled nursing care for people receiving DD services is associated with COVID‐19 outcomes (Landes et al., 2021).

There have been calls to respect the basic human rights of people with DDs and to adopt a disability lens approach to COVID‐19 initiatives to population health (Spagnuolo & Orsini, 2020). The WHO (2020), the Government of Canada through the Public Health Agency of Canada (Government of Canada, 2020), Ontario Human Rights Commission (Ontario Human Rights Commission, n.d.), disability organizations and scholars have urged healthcare and public health systems to recognize, prepare and address the differentiated impact the pandemic is having on vulnerable sectors of the population (Spagnuolo & Orsini, 2020). Taken together, it is being stressed that public and health workers must ensure vulnerable groups have: (i) access to non‐discriminatory health care; (ii) continuity of caregiving support; (iii) timely access to information in accessible formats and language related to COVID‐19; and (iv) access to vital public health; and free of stigma and discrimination (such as racism, ageism, ableism) in relation to COVID‐19.

4.2. Limitations

We recognize several limitations to our review. First, we applied a narrative review approach and, therefore, limited our examination to readily available literature. However, we have documented the process of study selection in detail and conducted the review with several team members to enhance reliability of decision making in study selection, and information extraction and synthesis. Second, the findings are based on studies available in English only, so are linguistically specific. Third, the studies included in the review had different research designs, and we did not apply an evaluation of strength of design in study selection. However, we believe learning from across study designs is informative to enhance nursing education in the DDs field. Finally, the findings from our review are specific to several English‐speaking countries and may not relate closely to nursing care for people with DDs as practiced in other countries; however, we believe our recommendations can be relevant broadly to nursing educational and training settings.

5. CONCLUSION

Families with DDs face systemic disadvantages across the social determinants of health and interlocking barriers to health care that place them at a high risk for poor health outcomes. It is timely and crucial to generate evidence about effective strategies to educate, train and support nurses to develop their competencies in the delivery of quality health care for people with DDs in all sectors of the health and social care systems. We have highlighted some of the competencies (e.g., removing communication barriers) and professional supports (e.g., staff with skill mix) nurses need to care for people with DDs. We provide recommendations addressing access, education, collaboration, communication, use of standardized tools and creating a safe environment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nazilla Khanlou conceptualized the project and design of the study and supervised all aspects of this work. Attia Khan implemented the research. Attia Khan and Luz Maria Vazquez contributed to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Faculty of Health ‐ Minor Research Grant, York University, ON, Canada, granted to the first author (Nazilla Khanlou) as principal investigator. The fourth author (Rani Srivastava) was a coinvestigator on the project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful for the assistance of Amirtha Karunakaran and Sheena Madzima in review of the literature.

Khanlou, N. , Khan, A. , Kurtz Landy, C. , Srivastava, R. , McMillan, S. , VanDeVelde‐Coke, S. , & Vazquez, L. M. (2023). Nursing care for persons with developmental disabilities: Review of literature on barriers and facilitators faced by nurses to provide care. Nursing Open, 10, 404–423. 10.1002/nop2.1338

Endnotes

A law to include children with disabilities in public school settings and provide them free and appropriate services.

Social stories provide context of an experience in pictures / images to help a child with ASD understand what will happen for particular visits and to make the visit physically, socially and emotionally safe.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. L. , Humphries, K. , McDermott, S. , Marks, B. , Sisirak, J. , & Larson, S. (2013). The state of the science of health and wellness for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(5), 385–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, E. E. , Ayers, K. B. , Brown, K. S. , Dunn, D. S. , & Pilarski, C. R. (2020). No body is expendable: Medical rationing and disability justice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. American Psychologist. Advance online publication. 10.1037/amp0000709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arim, R. (2015). A profile of persons with disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years or older, 2012. Canadian survey on disability, 2012. Statistic Canada Catalogue No. 89‐654‐X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89‐654‐x/89 [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, R. , & Nellums, L. B. (2020, March 17). The COVID‐19 response must be disability inclusive. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e257. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30076-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auert, E. J. , Trembath, D. , Arciuli, J. , & Thomas, D. (2012). Parents' expectations, awareness, and experiences of accessing evidence‐based speech‐language pathology services for their children with autism. International Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 14(2), 109–118. 10.3109/17549507.2011.652673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakas, K. , Gallaher, C. S. , & Tilley, C. (2015). Optimizing perioperative care for children and adolescents with challenging behaviors. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 40(3), 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber, A. S. , Zimmerman, S. , Reed, D. , Mitchell, C. M. , Sloane, P. D. , Harris‐Wallace, B. , Perez, R. , & Schumacher, J. G. (2014). Licensed nurse staffing and health service availability in residential care and assisted living. Journal of the American Geriatrics, 62(5), 805–811. 10.1111/jgs.12786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, W. M. , Nobre, M. C. , & Jatene, F. B. (2004). Evidence based clinical practice: Part II‐searching evidence databases. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, 50(1), 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz, C. (2007). Facilitating the transition of adolescents with developmental disabilities: Nursing practice issues and care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 22(2), 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill C‐81 . (2019, June 21). An act to ensure a barrier‐free Canada. Parliament of Canada. https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42‐1/bill/C‐81/royal‐assent [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, J. , & Ing, P. (2005). ‘Seen but not heard’—Young people's experience of advocacy. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14(1), 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2017). Developmental disabilities. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Cheak‐Zamora, N. C. , & Teti, M. (2015). “You think it's hard now … it gets much harder for our children”: Youth with autism and their caregiver's perspectives of health care transition services. Autism, 19(8), 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew, K. L. , Iacono, T. , & Tracy, J. (2009). Overcoming communication barriers: Working with patients with intellectual disabilities. Australian Family Physician, 38(1/2), 10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiri, G. , & Warfield, M. E. (2012). Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal Child Health Journal, 16(5), 1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieza, A. (2015). Preface. In Hatton C. & Emerson E. (Eds.), International review of research in developmental disabilities: Health disparities and intellectual disabilities (pp. xi–xiv). Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn‐Wells, H. (2014). Managing constipation in adults with severe learning disabilities. Learning Disability Practice, 17(9), 16‐22. 10.7748/Idp.17.9.16.e1582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, S. , Morrison, J. , Melville, C. , Finlayson, J. , Allan, L. , & Martin, G. (2006). Improving the health of people with intellectual disabilities: Outcomes of a health screening programme after one year. JIDR, 50(9), 667–677. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane, L. , Adams, F. , Harper, G. , Welch, J. , & Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 23(2), 477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P. (2000). The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and practice. Oxford Review of Education, 26(3–4), 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Desroches, M. L. , Fisher, K. , Ailey, S. , & Stych, J. (2021). “We were absolutely in the dark”: Latent analysis of developmental disability nurses' experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 8, 23333936211051705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, J. , Johnson, N. , Stoneck, A. V. , Martinez, D. M. , & Massey, M. (2012). Evaluation of a coping kit for children with challenging behaviors in a pediatric hospital. Pediatric Nursing, 38(4), 215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ee, J. , Stenfert Kroese, B. , & Rose, J. (2021). Experiences of mental health professionals providing services to adults with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems: A systematic review and meta‐synthesis of qualitative research studies. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 1–24. 10.1177/17446295211016182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, E. , Hatton, C. , Robertson, J. , Baines, S. , Evison, F. , & Glover, G. (2012). People with learning disabilities in England 2011. Improving Health & Lives: Learning Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. (2004). Health disparities and mental retardation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(1), 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. , Robichaux, C. , Sauerland, J. , & Stokes, F. (2020). A nurses' ethical commitment to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Nursing Ethics, 27(4), 1066–1076. 10.1177/0969733019900310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, M. (2020, February 3). Work pressures ‘pose barrier’ to compassionate learning disability care. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/learning‐disability/work‐pressures‐pose‐barrier‐to‐compassionate‐learning‐disability‐care‐03‐02‐2020/ [Google Scholar]

- Friese, T. , & Ailey, S. (2015). Specific standards of care for adults with intellectual disabilities. Nursing Management, 22(1), 32–37. 10.7748/nm.22.1.32.e1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M. R. , Suplee, P. D. , & Jerome‐D'Emilia, B. (2016). Survey of nursing faculty preparation for teaching about autism spectrum disorders. Nurse Educator, 41(4), 212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarelli, E. , & Gardner, M. R. (2012). Nursing of autism spectrum disorder. Springer Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada . (2020, October 1). Vulnerable populations and COVID‐19. https://www.canada.ca/en/public‐health/services/publications/diseases‐conditions/vulnerable‐populations‐covid‐19.html [Google Scholar]

- Green, B. N. , Johnson, C. D. , & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer‐reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, J. E. (2003). Addressing the need for education: Curriculum development for nurses about intellectual and developmental disabilities. Nursing Clinics, 38(2), 185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, J. , & Nugent, B. (2007). Health visitors' perceptions of their role in autism spectrum disorder. Community Practitioner, 80(1), 18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdani, Y. , & Lunsky, Y. (2016). Health and health service use of youth and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 3(2), 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Harris‐Kojetin, L. , Sengupta, M. , Park‐Lee, E. , Valverde, R. , Caffrey, C. , Rome, V. , & Lendon, J. (2016). Long‐term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long‐Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital & Health Statistics. Series 3, Analytical and Epidemiological Studies, 38(x–xii), 1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Balandin, S. , & Worrall, L. (2012). Nursing the patient with complex communication needs: Time as a barrier and a facilitator to successful communication in hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines, M. , Bulkeley, K. , Dudley, S. , Cameron, S. , & Lincoln, M. (2019). Delivering quality allied health services to children with complex disability via telepractice: Lessons learned from four case studies. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31(5), 593–609. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, C. , Schuengel, C. , & Stolk, J. (2002). Understanding challenging behaviour in people with severe and profound intellectual disability: A stress‐attachment model. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46(6), 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N. L. , Lashley, J. , Stonek, A. V. , & Bonjour, A. (2012). Children with developmental disabilities at a pediatric hospital: Staff education to prevent and manage challenging behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27(6), 742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, S. , & Hegarty, J. (2010). Breast awareness within an intellectual disability setting. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14(4), 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokina, A. , & Kern, L. (2010). Social story™ interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(7), 812–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn, G. , Hammond, L. , & Turner, A. (2006). A cascade of disparities: Health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 12(1), 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes, S. D. , Turk, M. A. , & Wong, A. W. (2021). COVID‐19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability in California: The importance of type of residence and skilled nursing care needs. Disability and Health Journal, 14(2), 101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, M. , Hanna, S. , King, G. , Hurley, P. , King, S. , Kertoy, M. , & Rosenbaum, P. (2003). Factors affecting family‐centred service delivery for children with disabilities. Child Care Health and Developement, 29(5), 357–366. 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, E. , Balogh, R. , Durbin, A. , Holder, L. , Gupta, N. , Volpe, T. , & Lunsky, Y. (2019). Addressing gaps in the health care services used by adults with developmental disabilities in Ontario. ICES; Observatory. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. , Morrison, J. , Melville, C. , Baltzer, M. , MacArthur, L. , & Cooper, S. (2018). Embedding routine health checks for adults with intellectual disabilities in primary care: Practice nurse perceptions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(4), 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, I. , Basu, I. , & De, M. (2020). Role of nursing professionals in making hospital stay effective and less stressful for patients with ASD: A brief overview. International Journal of Advancement in Life Sciences Research, 3(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, B. , & Sisirak, J. (2017). Nurse practitioners promoting physical activity: People with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 13(1), e1–e5. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, B. , Sisirak, J. , & Hsieh, K. (2008). Health services, health promotion, and health literacy: Report from the state of the science in aging with developmental disabilities conference. Disability and Health Journal, 1(3), 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, C. E. , Gundlach, J. , Brelage, P. , & Snyder, S. (2018). School nurses increasing the compliance of hygiene routines for students with autism spectrum disorder. NASN School Nurse, 33(5), 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville, C. , Finlayson, J. , Cooper, S. , Allan, L. , Robinson, N. , Burns, E. , & Morrison, J. (2005). Enhancing primary health care services for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(3), 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S. , Fawcett, G. , Brisebois, L. , & Hughes, J. (2018). Canadian survey on disability: A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Catalogue No. 89‐654‐X2018002. Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanasamy, A. , Gates, B. , & Swinton, J. (2002). Spirituality and learning disabilities: A qualitative study. British Journal of Nursing, 11(14), 948–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndengeyingoma, A. , & Ruel, J. (2016). Nurses' representations of caring for intellectually disabled patients and perceived needs to ensure quality care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(21–22), 3199–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Human Rights Commission . (n.d). Actions consistent with a human rights‐based approach to managing the COVID‐19 pandemic. Queen's Printer for Ontario. http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/actions‐consistent‐human‐rights‐based‐approach‐managing‐covid‐19‐pandemic [Google Scholar]

- Raemy, S. , & Paignon, A. (2019). Providing equity of care for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Western Switzerland: A descriptive intervention in a university hospital. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpinato, N. , Bradley, J. , Kurbjun, K. , Bateman, X. , Holtzer, B. , & Ely, B. (2010). Caring for the child with an autism spectrum disorder in the acute care setting. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 15(3), 244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, M. , Kerr, M. , O'Hara, D. , Bainbridge, D. , Cooper, S. , Davis, R. , Fujiura, G. , Heller, T. , Holland, A. , Krahn, G. , Lennox, N. , Meaney, J. , & Wehmeyer, M. (2005). Reducing health disparity in people with intellectual disabilities: A report from health issues special interest research Group of the International Association for the scientific study of intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 2, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve, L. A. , Gonzalez, V. , Boulet, S. L. , Visser, S. N. , Rice, C. E. , Braun, K. N. , & Boyle, C. A. (2012). Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2010. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(2), 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Services and Support to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008, S.O. 2008, c. 14 . (2019, July 1). Ontario e‐Laws. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/08s14 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J. (2020, June 9). COVID‐19 infections and deaths are higher among those with intellectual disabilities. National Public Radio: Special Series. The Coronavirus Crisis. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/09/872401607/covid‐19‐infections‐and‐deaths‐are‐higher‐among‐those‐with‐intellectual‐disabili?fbclid=IwAR2kttqSJDPnE3Xf2pW5l‐SnPa6PMSk0Eg_xhqFpasX8UlmJlhWE‐OG2iWg [Google Scholar]

- Sheerin, F. K. (2008). Diagnosis and interventions pertinent to intellectual disability nursing. International Jounal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 19(4), 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, B. (2013). Perceptions of school nurses in the care of students with disabilities. The Journal of School Nursing, 29(5), 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeltzer, S. C. , Avery, C. , & Haynor, P. (2012). Interactions of people with disabilities and nursing staff during hospitalization. The American Journal of Nursing, 112(4), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. E. , McCann, H. P. , Urbano, R. C. , Dykens, E. M. , & Hodapp, R. M. (2021). Training healthcare professionals to work with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 59(6), 446–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo, N. , & Orsini, M. (2020, March 29). COVID‐19 visitation bans for people in institutions put many at risk in other ways. Canada. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion‐covid‐19‐public‐health‐institutions‐risk‐1.5510546 [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . (2020, November 12). Table 13‐10‐0376‐01 type of disability for persons with disabilities aged 15 years and over, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories. 10.25318/1310037601-eng [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W. , Berg, J. , Bradley, E. , Cheetham, T. , Denton, R. , Heng, J. , & Lunsky, Y. (2011). Primary care of adults with developmental disabilities: Canadian consensus guidelines. Canadian Family Physician, 57(5), 541–553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W. F. , Diepstra, H. , Heng, J. , Ally, S. , Bradley, E. , Casson, I. , Hennen, B. , Kelly, M. , Korossy, M. , McNeil, K. , Abells, D. , Amaria, K. , Boyd, K. , Gemmill, M. , Grier, E. , Kennie‐Kaulbach, N. , Ketchell, M. , Ladouceur, J. , Lepp, A. , … Witherbee, S. (2018). Primary care of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: 2018 Canadian consensus guidleines. Canadian Family Physician, 64(40), 254–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey Place . (2020). Tools for the primary care of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. https://ddprimarycare.surreyplace.ca/tools‐2/ [Google Scholar]

- Thapar, A. , Cooper, M. , & Rutter, M. (2017). Neurodevelopmental disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 339–346. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. , Bourke, J. , Girdler, S. , Bebbington, A. , Jacoby, P. , & Leonard, H. (2011). Variation over time in medical conditions and health service utilization of children with Down syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics, 158(2), 194–200.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. S. , O'Leary, K. , Jensen, E. , Scott‐Findlay, S. , O'Brien‐Pallas, L. , & Estabrooks, C. A. (2008). The relationship between busyness and research utilization: It is about time. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(4), 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , Moher, D. , Peters, M. D. J. , Horsley, T. , Weeks, L. , Hempel, S. , Akl, E. A. , Chang, C. , McGowan, J. , Stewart, L. , Hartling, L. , Aldcroft, A. , Wilson, M. G. , Garritty, C. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer, F. , McGrother, C. , Thorp, C. , Donaldson, M. , Bhaumik, S. , Watson, J. , & Hollin, C. (2006). Physical aggression towards others in adults with learning disabilities: Prevalence and associated factors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(4), 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities . (2016). Guidelines on periodic reporting to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, including under the simplified reporting procedures. www.betheljada.org/images/pdf/Suriname_CRPD_training_Session_4_Reporting_Guidlines‐Handout [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J. A. , Lunsky, Y. , & Morin, D. (2010). Psychology graduate student training in developmental disability: A Canadian survey. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 51(3), 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N. J. , Rees, S. , Northway, R. , & Lewis, P. (2022). Toward mainstream nursing roles specialising in the care of people with intellectual and developmental disability. Collegian. 10.1016/j.colegn.2022.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020, March 26). Disability considerations during the COVID‐19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoV‐Disability‐2020‐1 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Orgnization . (2016). Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131‐eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum, L. , Nicholas, D. B. , Muskat, B. , Kilmer, C. , Newton, A. S. , Craig, W. R. , Ratnapalan, S. , Cohen‐Silver, J. , Greenblatt, A. , Roberts, W. , & Sharon, R. (2016). Perspectives of health care providers regarding emergency department care of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Aurism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1725–1736. 10.1007/s10803-016-2703-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.