Abstract

Human infections with Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) cause hemorrhagic colitis. The Stxs belong to a large family of ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) that are found in a variety of higher plants and some bacteria. Many RIPs have potent antiviral activity for the plants that synthesize them. STEC strains, both virulent and nonvirulent to humans, are frequently isolated from healthy cattle. Interestingly, despite intensive investigations, it is not known why cattle carry STEC. We tested the hypothesis that Stx has antiviral properties for bovine viruses by assessing the impact of Stx type 1 (Stx1) on bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from cows infected with bovine leukemia virus (BLV). PBMC from BLV-positive animals invariably displayed spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation (SLP) in vitro. Stx1 or the toxin A subunit (Stx1A) strongly inhibited SLP. Toxin only weakly reduced the pokeweed mitogen- or interleukin-2-induced proliferation of PBMC from normal (BLV-negative) cows and had no effect on concanavalin A-induced proliferation. The toxin activity in PBMC from BLV-positive cattle was selective for viral SLP and did not abrogate cell response to pokeweed mitogen- or interleukin-2-induced proliferation. Antibody to virus or Stx1A was most effective at inhibiting SLP if administered at the start of cell culture, indicating that both reagents likely interfere with BLV-dependent initiation of SLP. Stx1A inhibited expression of BLV p24 protein by PBMC. A well-defined mutant Stx1A (E167D) that has decreased catalytic activity was not effective at inhibiting SLP, suggesting the inhibition of protein synthesis is likely the mechanism of toxin antiviral activity. Our data suggest that Stx has potent antiviral activity and may serve an important role in BLV-infected cattle by inhibiting BLV replication and thus slowing the progression of infection to its malignant end stage.

Human infections with Shiga-toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) cause hemorrhagic colitis that can progress to life-threatening sequelae, the hemolytic-uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (7, 31). The predominant disease-causing STEC serotype in North America is O157:H7, but outbreaks have also been traced to several other serotypes (1, 7, 31). The major mode of disease transmission is through ingestion of contaminated bovine food products (31). STEC strains, both virulent and nonvirulent to humans, are frequently isolated from domestic cattle and other ruminants (6, 36, 42, 48). Large-scale surveys routinely find STEC culture-positive cattle with the incidence as high as 99% in some herds (13, 25). STEC strains do not appear harmful to the animal carriers. For example, cattle infected with the O157:H7 serotype, highly virulent in people, are clinically normal (12), as are domestic ruminants of other species harboring O157:H7 or other STEC (6, 36, 48). Interestingly, despite intensive investigations, an explanation as to why cattle carry STEC in the gastrointestinal tract has not surfaced.

Stx type 1 (Stx1) belongs to a large family of ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) that are found in a variety of higher plants and some bacteria. Class 1 RIPs are N-glycosidases that inactivate ribosomes by removing a single adenine in a specific rRNA sequence (17, 18, 28). Class 2 RIPs are composed of an A subunit homologous to class 1 RIPs, joined to one or more B subunits, usually galactose-specific lectins, that facilitate toxin binding and uptake into target cells. Stx1 is a type 2 RIP composed of one A subunit associated with a pentamer of receptor-binding B subunits. Because of their ability to bind to target cells, class 2 RIPs are potent cytotoxins. Stx1 is toxic to cells that express high levels of the toxin receptor, globotriosylceramide (Gb3 or CD77), most notably Vero cells and some microvascular endothelial cells (44).

Plant RIPs of both class 1 (e.g., pokeweed antiviral protein, titrin, and trichosanthin) and class 2 (e.g., ricin) have potent antiviral activities for the plants that synthesize them (51). In addition, these compounds often inhibit viral proliferation in mammalian cells in vitro, and some have been tested in vivo in clinical or laboratory settings. For example, ricin can eliminate latent herpes simplex virus in mice (26). Other plant RIPs inhibited replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) at concentrations nontoxic to uninfected cells (37, 45). Since Stx1A shares structure-function features and identical enzymatic activity with the ricin and other RIP A chains, (10, 27, 50, 52), and because the majority of cattle carry STEC, we hypothesized that Stx1 has antiviral properties in cattle. We tested this hypothesis using PBMC from cows infected with bovine leukemia virus (BLV).

BLV is an oncogenic retrovirus responsible for the enzootic form of bovine lymphosarcoma, the most frequent malignancy of domestic cattle (22). BLV infection results in a 1- to 8-year-long asymptomatic period (23), followed by development of persistent lymphocytosis (PL) in approximately 30% of infected cattle with progression to a malignant lymphosarcoma in fewer than 10% of the animals (23). The PL stage is a benign neoplasia of B lymphocytes, which are the predominant or exclusive targets of BLV (19). This stage of infection is associated with an increased percentage of peripheral B lymphocytes containing provirus as well as increased viral gene expression (41).

A hallmark of PBMC from BLV-infected cattle is that they proliferate spontaneously in vitro (53, 54). This spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation (SLP) is particularly vigorous in PBMC cultures from cattle in the PL stage of infection. Since derepression of viral gene transcription and the synthesis of viral proteins (4, 22, 33) precede and are required for SLP to occur, we tested our hypothesis that Stx1 has antiviral activity by assessing the impact of toxin on SLP. Specifically, our goals were (i) to assess suppression of SLP by Stx1, (ii) to determine whether Stx1 acts selectively on BLV-positive PBMC, and (iii) to test the ability of Stx1 to inhibit expression of BLV proteins. Our results indicate that Stx1 has a potent antiviral activity against BLV-positive bovine lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Friesian-Holstein cows from the University of Idaho dairy were used as blood donors. Cows were identified as BLV positive by the standard method of determining high titers of anti-BLV antibody. Five PL cows were identified by elevated numbers and percentages of B cells (3 standard deviations above normal levels) in peripheral circulation and used as BLV-positive donors. Cows with no detectable anti-BLV antibodies were used as BLV-negative donors.

Toxin.

Recombinant Stx subunit A (Stx1A), StxA with the E-to-D amino acid substitution at position 167 (referred to throughout as E167D), and StxB were purified as previously described (3, 27, 58). Stx1A was purified from E. coli SY327(pSC25). Concentrated periplasmic proteins were adsorbed to Matrex Gel Green A agarose (Amicon) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and Stx1A eluted as a single protein peak with approximately 0.3 M NaCl in a 0.15 to 1.0 M NaCl gradient. The E167D mutant was purified from E. coli SY327(pSC25.1) using the same protocol as for the wild-type StxA. Stx1B was purified from E. coli JM105(pSBC32). Periplasmic proteins were fractionated by ammonium sulfate precipitation, and Stx1B was separated by isoelectric focusing and native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Holotoxin was reconstituted in vitro by combining Stx1A and Stx1B at a 1:10 molar ratio in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0). The association of A and B subunits was confirmed by immunoblotting of proteins separated by analytical discontinuous native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Before use in cultures, toxins were dialyzed exhaustively against 10 mM PBS, and concentrations were measured using a Bio-Rad assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Lymphocyte culture and proliferation assay.

Blood was collected by jugular venipuncture into acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) (one part to four parts whole blood). PBMC were purified by density gradient centrifugation using Accu-Paque (1.086 g/ml; Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.) as previously described (20). Erythrocytes were lysed by incubation in warm ammonium chloride, and the PBMC preparation was washed several times in PBS-ACD mix (4:1) to remove platelets. PBMC were cultured in 96-well culture plates (Corning) at the initial density of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml (0.5 × 106 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. To assay cell proliferation, [3H]thymidine was added to the wells (1.0 μCi/well) 48 h after the start of cell culture and 16 to 18 h prior to cell harvest. Cells were harvested on a semiautomated 96-well plate harvester (Skatron Inc., Sterling, Va.) and the amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated was determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy (Packard Instrument Co., Downers Grove, Ill.) and expressed as counts per minute. In all experiments, measurements were obtained in at least four replicate samples. The percentage inhibition of proliferation was expressed as follows: (cpm of cultures with toxin/cpm of control cultures without toxin) × 100.

Flow cytometry.

Single-color surface staining of cells for flow cytometric analysis was performed using a standard protocol as previously described (14, 20). Percentages of blast-size cell populations were calculated using the forward scatter (FSC) and right angle side scatter (SSC) properties of cells and either CELLQuest or Macintosh Attractors software. Cells were designated as either blast size or non-blast size based on the greater linear FSC of blast-size cells. The population of nonviable cells was designated based on the increased log SSC of dead cells.

BLV expression assay.

PBMC suspended at the initial density of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml were placed in culture dishes (4.0 ml per dish) without toxin or with 1.0 μg of Stx1A per ml. The cells were harvested at 12, 18, 24, 48, and 72 h, centrifuged, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.5) with 0.1 M EDTA and 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples were subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles until cells were lysed, as determined microscopically. Supernatant was transferred to nitrocellulose using a 96-well blotter, and cell lysates were probed with the murine monoclonal antibody BLV-3 against the BLV 24-kDa protein (referred to throughout as anti-p24) and anti-mouse antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Immunoblots were developed using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma) as substrate, according to manufacturer's instruction, and scanned with a Hewlett-Packard densitometer; the results were quantitated with the Molecular Analyzer analytical program. The cultures of BLV-negative PBMC served as negative controls.

Reagents.

Concanavalin A (ConA) and pokeweed mitogen (PWM) were purchased from Sigma. Human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) was purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, N.Y.). Polyclonal antibody to Stx1A was generated by standard technique in New Zealand White rabbits. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). Murine monoclonal antibodies BLV-1 against the 51-kDa glycoprotein of BLV (referred to throughout at anti-gp51) and control antibody COLIS69A of the same isotype (immunoglobulin G1) were purchased from WSU Monoclonal Antibody Center (Pullman, Wash.).

Statistical analysis.

The results are presented as arithmetic means ± standard errors (SE). In all experiments, measurements were made from four or more replicates. Unless otherwise stated, the results are means of three or more experiments. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to establish statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Stx1 suppresses SLP in cultures of PBMC from BLV-infected cows.

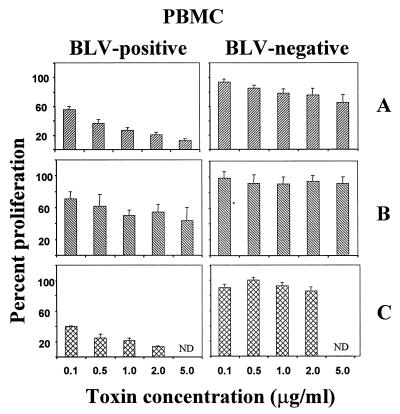

PBMC from five BLV-positive cows in the PL stage of infection invariably proliferated in vitro, and this SLP was consistently suppressed by Stx1 (Fig. 1). Holotoxin and Stx1A were potent suppressors of SLP, acting in a dose-dependent manner over the range of concentrations tested. The effects of Stx1A or holotoxin were significantly different at 0.1 and 0.5 μg/ml because the 95% confidence intervals of the percent proliferation values did not overlap. Stx1B was far less potent than Stx1A in suppressing SLP even at molar concentrations more than fourfold higher than those of Stx1A. Moreover, in contrast to Stx1A, Stx1B did not act in a dose-dependent fashion. The 95% confidence intervals of the percent proliferation values were overlapping for all concentrations of Stx1B.

FIG. 1.

Effect of Stx1 on lymphocyte proliferation. PBMC from PL (BLV-positive) or healthy (BLV-negative) cows were incubated with Stx1 holotoxin (C) or Stx1A (A) or Stx1B (B). BLV-negative cells were induced to proliferate by PWM (5.0 μg/ml). Cell proliferation was measured as incorporation of tritiated thymidine and expressed as a percentage of the cell proliferation in identical cultures without toxin. Data are means + SE from 3 (holotoxin) or 10 (Stx1 subunits) experiments. ND, not done.

Cellular proliferation in spontaneously proliferating cultures of BLV-positive PBMC almost exclusively involves B lymphocytes (19, 30, 41). To evaluate Stx1 activity on normal B cells, we measured Stx1 inhibition of PWM-induced proliferation of normal BLV-free PBMC. Normal B cells do not proliferate in culture unless stimulated to do so. Since a more appropriate control was not obvious, the PWM lectin, which is a B-cell mitogen, was used as the cell division stimulant. In contrast to SLP, PWM-induced proliferation of BLV-free PBMC was only weakly sensitive to Stx1 (Fig. 1). Low doses of Stx1A or Stx1 (0.1 μg/ml), sufficient to reduce SLP by 45 and 60%, respectively, caused <10% inhibition of proliferation induced by PWM. Stx1A at the highest concentration tested inhibited the PWM-induced proliferation by only 30%, whereas Stx1B and holotoxin either were marginally inhibitory or had a weak stimulatory effect in cultures from some donors.

To determine whether bovine T lymphocytes constitute targets for Stx1, we tested the impact of Stx1 on PBMC proliferation induced by ConA, a lectin that induces T-cell proliferation by specific interaction with the T-cell receptor complex. T-cell proliferation induced by ConA was not affected by Stx1 holotoxin or toxin subunits (data not shown).

These results indicated that SLP of BLV-positive PBMC is susceptible to Stx1-mediated inhibition and that the inhibitory effect is mediated by the A subunit of holotoxin. Subsequent experiments to further characterize toxin activity were performed with purified Stx1A or -B.

Anti-Stx1A serum prevents inhibition of SLP by Stx1.

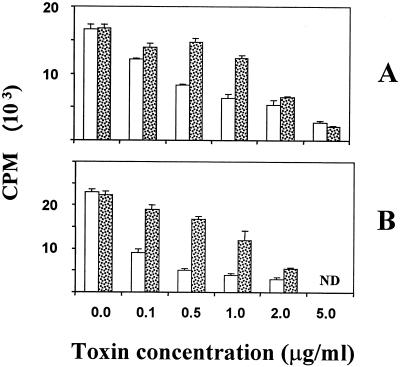

To determine if a spurious inhibitor was present in our toxin preparations, we tested the ability of anti-Stx1A immune serum to neutralize Stx1 or Stx1A suppression of SLP. Antitoxin neutralized Stx1 or Stx1A activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2) and did not affect cellular proliferation in cultures without toxin (data not shown). The antitoxin was effective within a range of titers from 1:1,000 to 1:50 but did not have a neutralizing ability outside this range (data not shown). Within this range, the ability of antitoxin to neutralize increasingly greater doses of Stx1A was directly proportional to concentration. For example, antitoxin restored about 80 or >50% of the thymidine incorporation in BLV-positive cultures treated with up to 1.0 μg of Stx1A or Stx1, respectively, per ml (Fig. 2). A two-way ANOVA indicated statistically significant differences among the effects of various concentrations of toxin and antitoxin as well as a significant interaction of these two factors.

FIG. 2.

Effect of antitoxin on Stx1-mediated inhibition of SLP in PBMC cultures from persistently lymphocytotic (BLV-positive) cows. PBMC from BLV-positive cows were incubated with various concentrations of toxin (A, A subunit; B, holotoxin), with normal rabbit serum containing irrelevant antibodies (open bars) and with polyclonal anti-Stx1A antibodies diluted 1:100 (stippled bars). Cell proliferation was measured as incorporation of tritiated thymidine and expressed as counts per minute. Data are means ± SE from four replicates from a representative experiment. ND, not done.

BLV-positive PBMC treated with Stx1A retain responsiveness to immunostimulation.

To determine the mechanism of SLP suppression by Stx1, it was important to assess whether the impact of the toxin on SLP was mediated by selective targeting or by indiscriminate suppression of the ability of BLV-positive PBMC to respond to immunostimulation. We tested the impact of Stx1A on cellular proliferation in cultures of BLV-positive PBMC supplemented with PWM or IL-2, a potent B-cell activator. The addition of IL-2 (1.0 ng/ml) to BLV-positive cultures strongly augmented proliferation, evidenced by a gain of about 6.0 × 104 cpm per well (Table 1). This IL-2-induced proliferation was preserved even in the presence of Stx1A at 1.0 μg/ml, a toxin concentration sufficient to cause almost complete suppression of SLP. Moreover, proliferation in these cultures exceeded proliferation in cultures of BLV-negative PBMC treated with combination of Stx1A and IL-2 (Table 1). BLV-positive cultures treated with Stx1A also retained the ability to respond to stimulation with PWM (Table 1). These results suggest that inhibition of SLP by Stx1 involves selective action on a subpopulation of PBMC and does not alter the ability of B cells not targeted by the toxin to respond to immunostimulation.

TABLE 1.

Effects of Stx1A and IL-2 on proliferation of BLV-positive and BLV-negative PBMCa

| PBMC | Stx1A (μg/ml) | Mean cpm (10) ± SE (n = 4)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No stimulant | IL-2

|

PWM (5.0 μg/ml) | |||

| 0.1 ng/ml | 1.0 ng/ml | ||||

| BLV positive | 0 | 77.3 ± 4.8 | 97.3 ± 3.2 | 136.0 ± 1.5 | 118.2 ± 1.9 |

| 0.1 | 38.3 ± 1.3 | 60.5 ± 1.9 | 123.0 ± 1.1 | 112.3 ± 3.1 | |

| 1.0 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 22.1 ± 0.2 | 61.5 ± 2.2 | 101.4 ± 0.8 | |

| BLV negative | 0 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 42.5 ± 0.3 | 103.4 ± 2.2 |

| 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 34.1 ± 0.5 | 83.7 ± 3.2 | |

| 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 25.9 ± 1.1 | 61.7 ± 0.6 | |

Toxin and mitogens were added at the beginning of culture.

IL-2 and PWM induce substantial T-cell blastogenesis. In BLV-negative PBMC cultures up to 40 to 60% of blast-size cells are classified as T cells (defined as CD5-positive cells lacking B-cell markers). Since Stx1 did not inhibit T-cell proliferation, T-cell division may have masked Stx-mediated inhibition of B-cell blastogenesis. The percentage of B cells enlarged to blast size in PWM-stimulated cultures ranged from 20% (BLV positive) to 40% (BLV negative) and was not affected by the presence of Stx1A at 1.0 μg/ml. However, in IL-2-stimulated cultures, the percentage of blasts was reduced by toxin (from 60% to 30%) in BLV-negative PBMC, although no such reduction occurred in BLV-positive cultures. This Stx1A activity correlated with the lack of CD5 expression on B cells. Among BLV-negative PBMC, in which CD5-negative cells predominate, toxin inhibited B-cell enlargement whereas among BLV-positive PBMC, in which CD5-positive B-cells predominate, toxin did not inhibit B-cell enlargement.

We also examined the impact of Stx1A on PBMC cultures stimulated with LPS. This gram-negative bacterial cell wall component can significantly influence immune responses and was shown to stimulate BLV expression in cultures of BLV-positive PBMC (34). LPS used at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml increased proliferation of BLV-positive PBMC twofold but did not induce normal PBMC cultures to proliferate, indicating that only BLV-positive cultures were susceptible to mitogenic stimulation by low concentration of LPS. The increased proliferation resulting from LPS application was completely abrogated by treatment with Stx1A (data not shown), further indicating that cells involved in SLP constitute the cellular targets of Stx1A.

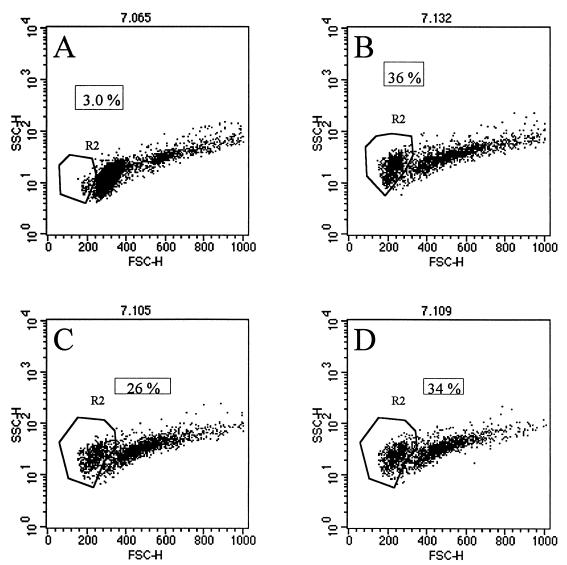

Stx1A suppression of SLP is not accompanied by increased cytotoxicity.

Additional support for the premise that Stx1 targets a selected and probably minor subpopulation of B cells comes from the finding that cell death, detected by trypan blue inclusion or cell shrinkage measured by flow cytometry, was not greater in cultures treated with Stx1A than in cultures without toxin. We analyzed PBMC from five PL cows incubated with and without toxin over a 3-day culture period and observed no differences in the number of dead cells. Results from a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 3. After 3 days in culture, 36% of the cells incubated without toxin were nonviable B cells (Fig. 3B); likewise, 26 and 34% of the cells incubated with Stx1A at 0.1 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, were nonviable B cells (Fig. 3C and D). The finding that treatment with Stx1A did not increase B-cell death is consistent with the fact that although the majority of B cells from cows in PL stage contain provirus, very few PBMC from BLV-positive cattle express viral proteins (4, 11, 24, 39).

FIG. 3.

Effect of Stx1A on B-cell viability. Flow cytometry was used to gate PBMC from PL BLV-positive cows on the basis of surface expression of bovine B-lymphocyte markers. The percentages of dead cells (boxes) were ascertained from dot plots of SSC versus FSC. Cells exhibiting shrinkage (low FSC value) and increased granularity (high SSC) were considered nonviable (marked as R2 [region 2]). (A) Time zero, PBMC ex vivo; (B, C, and D) PBMC cultured for 3 days with 0, 0.1, and 0.5 mg of Stx1A per ml, respectively.

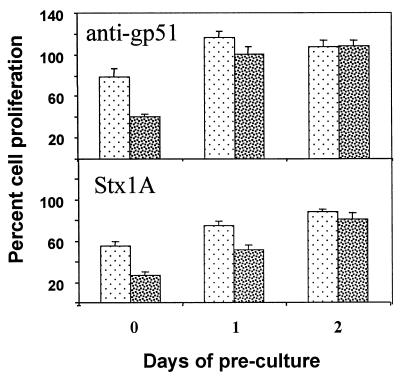

Inhibition of SLP by antiviral antibody or Stx1A is time dependent.

SLP in cultures of BLV-positive PBMC is preceded within 24 h of culture by de novo synthesis of viral proteins and dissemination of viral particles (4). It is known that anti-BLV serum can block SLP (55). To assess whether viral proteins accessible to antibody were required to sustain SLP, we examined the ability of antiviral antibody to interfere with SLP over a 2-day period. Monoclonal anti-gp51 was able to reduce thymidine incorporation in spontaneously proliferating cultures by 60% (Fig. 4). However, this inhibition required application of anti-gp51 at the beginning of cell culture (Fig. 4). Inhibition of SLP by anti-gp51 was due to a specific interaction with viral proteins, since this antibody did not affect IL-2-induced proliferation of BLV-negative PBMC, and control monoclonal antibody of the same isotype had no effect on SLP (data not shown). These results are in agreement with the findings that dissemination of BLV proteins is involved in initiation of SLP, but they also suggest that BLV proteins are not required for continuation of an established SLP event.

FIG. 4.

Effect of preculture on the ability of anti-BLV antibody or the Stx1 subunits to inhibit SLP in cultures of PBMC from persistently lymphocytotic (BLV-positive) cows. Anti-gp51 monoclonal antibody or toxins were added to PBMC cultures on day 0 (without preculture) or after PBMC had been precultured for 1 or 2 days in medium. Antibody was applied at 2.0 μg/ml (light stipple) and 20.0 μg/ml (dark stipple). Toxins were applied at 0.1 μg/ml (light stipple) and 1.0 μg/ml (dark stipple). Cell proliferation was measured as incorporation of tritiated thymidine and expressed as a percentage of the cell proliferation in control cultures treated with control monoclonal antibody. Data are means ± SE from three or more experiments.

To determine if toxin also acts on SLP in a time-dependent fashion, we administered Stx1A or Stx1B to cultures of BLV-positive PBMC at various times after the start of cell culture. Similar to treatment with anti-gp51, the ability of Stx1A to inhibit SLP was reduced if cells were precultured in medium for 24 h before toxin application (Fig. 4). Stx1A applied on day 2 of culture at concentrations of up to 1.0 μg/ml had only minimal impact on SLP (Fig. 4), and even 5.0 μg of Stx1A per ml applied on day 2 of culture reduced thymidine incorporation in spontaneously proliferating cultures by only 30 to 40% (data not shown). These results suggest that inhibition of SLP by Stx1A is time dependent and are likely based on the ability of the toxin to interfere with the initiation of spontaneous proliferation. The fact that susceptibility of SLP to inhibition by either Stx1A or anti-gp51 lessens within 24 h of culture argues that the cells involved in dissemination of viral proteins and the initiation of SLP constitute targets for Stx1.

In contrast to Stx1A, the relatively minor effect of Stx1B on SLP did not change when Stx1B was applied after a preculture without toxin (data not shown). This difference suggests that Stx1B and Stx1A have different modes of action and likely affect different subpopulations of PBMC.

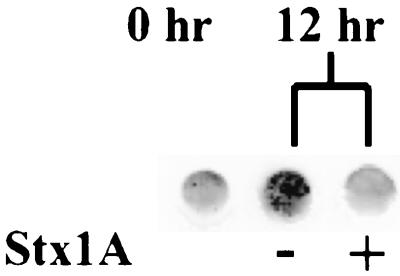

Stx1A reduces expression of BLV core protein.

To directly test antiviral activity of Stx1, we assayed the expression of BLV p24 core protein in PBMC cultured with or without Stx1A. Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates of PBMC cultured for 12 h showed a lesser amount of p24 protein in cells treated with toxin (1.0 μg/ml) than in cells in the control cultures without toxin (Fig. 5). The optical density of the immunoreaction in the sample treated with toxin was 442-fold less than the immunoreaction in the sample without toxin, suggesting that toxin suppressed viral protein synthesis.

FIG. 5.

Effect of Stx1A on the expression of BLV protein in cultured PBMC from BLV-positive cows. PBMC were harvested after 12 h of culture with or without 1.0 μg of Stx1A per ml; washed cells were lysed and blotted onto nitrocellulose. The blot was probed with anti-p24 monoclonal antibody. Sample obtained prior to culture (0 h) shows p24 protein in unstimulated ex vivo PBMC.

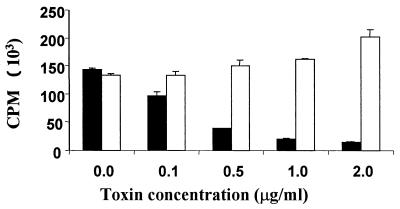

Stx1A enzymatic activity is required for antiviral affect.

We used a well-characterized site-specific mutant of the Stx1A chain to determine if the protein synthesis-inhibitory enzymatic activity of the toxin was required for its antiviral affect. The E167D catalytic center mutant maintains structural integrity but has enzymatic activity several orders of magnitude less than that of wild-type toxin (27). In contrast to wild-type Stx1A, the E167D mutant toxin had no inhibitory activity, and PBMC from BLV-positive cows treated with mutant toxin proliferated as if they were not treated with toxin (Fig. 6). This observation suggests that toxin-mediated protein synthesis inhibition is the mechanism by which Stx1A suppressed viral protein expression in cultures of BLV-positive PBMC and without viral proteins, the hallmark SLP does not occur.

FIG. 6.

Effect of decreased enzymatic activity of Stx1A on the inhibition of SLP. PBMC from PL BLV-positive cows were incubated with various concentrations of wild-type Stx1A (solid bars) or the site-specific mutant E167D (open bars). Cell proliferation was measured as incorporation of tritiated thymidine and expressed as counts per minute. Data are means + SE from four replicates from a representative experiment.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that Stx1 has antiviral activity in cattle, the animal reservoir for STEC. We accomplished this aim by examining the ability of Stx1 to inhibit BLV-dependent SLP of PBMC from cows in the PL stage of BLV infection. Our results provide the first demonstration of antiviral activity of Stx and are consistent with a copious body of research showing antiviral activity of the RIP family of toxins in the plants that express them (reviewed in reference 51). We showed that Stx1 specifically suppresses BLV-induced SLP (the hallmark of this viral infection) and that toxin does not suppress cytokine- or mitogen-induced cell proliferation in either BLV-infected or normal bovine cells. In addition, we show that toxin does not induce increased or indiscriminant cell death. The most likely explanation for these results is that Stx1 has a specific adverse impact on the cells that express the virus.

A high proportion (up to 70% and possibly more) of the B cells from BLV-infected cattle carry provirus, but due to repression of the BLV genome, only a small proportion (<1%) of these cells express viral proteins initially in culture (22). It is well established that SLP is preceded and accompanied by synthesis of viral proteins (32, 53). BLV-specific antibody inhibition of SLP is also well established (54, 55) and may result from interference of the release of BLV particles from cultured cells (16). The premise that Stx1 has antiviral activity is supported by our findings that maximal SLP sensitivity to Stx1 was exhibited within the first 24 h of culture. We also found a similar time-dependent loss of sensitivity of SLP to anti-gp51-mediated inhibition. Both of these findings are consistent with the fact that the expression of BLV particles in culture reaches maximum after 12 to 24 h of cell culture (57). Finally, we demonstrated that cell cultures treated with Stx1 express less BLV p24 protein. This could be due either to the nonlethal suppression of viral protein synthesis or Stx1-mediated death of the cells expressing viral proteins. Our assays did not allow distinction between these possibilities, since our determination of the p24 protein level was limited to the protein present within cells harvested from the cell cultures at a given time.

Similar to ricin, the archetype of the A:B RIPs, Stx1 holotoxin is composed of an enzymatically active A chain and a cell receptor-binding B-chain pentamer. The A subunit alone was able to abrogate SLP and was similarly efficacious as holotoxin. Thus, sensitivity of target cells in BLV-positive culture to Stx1 occurs via a mechanism that does not require the B subunit. This is in sharp contrast to the receptor-based mechanism by which Stx1 gains entry to Vero cells and other cellular targets described thus far (5, 29). For example, others have shown that human B lymphocytes are sensitive to Stx and this sensitivity parallels expression of CD77 that can bind the B subunit. However, normal bovine lymphocytes are not sensitive to toxin, and bovine cells have not been shown to express the CD77 ligand. Also, a precedence of antiviral activity without the B subunit has been set by many plant RIPs. Type 1 RIP hemitoxins composed solely of an enzymatic A chain are potent antiviral agents; examples include inhibition of HIV replication by pokeweed antiviral protein (45), bryodin (56), and trichosanthin (9). Similar anti-HIV activity is exhibited by an isolated A chain of ricin (45). Typically, inhibition of HIV-1 replication by plant RIPs occurs at the concentrations nontoxic to uninfected cells (37, 45).

The mechanism of Stx anti-BLV activity was not investigated; however, our finding that the E167D mutant lacks antiviral activity, along with the fact that this catalytic center has been highly conserved among all RIPs, strongly suggests that directed protein synthesis inhibition is the likely mechanism of antiviral activity. It should be noted, however, that inhibition of protein synthesis may not be the only mechanism of antiviral activity. Plant RIPs were shown to inhibit HIV-1 integrase via topological activity on long terminal repeats of viral DNA (37), and these proteins show structural similarities to retroviral reverse transcriptases (49). Inhibition of HIV infection by plant RIPs involves regions of these proteins which are not required for ribosome inactivation, suggesting that the anti-HIV activity of ribosome-inactivating proteins may not be the result of N-glycosidase activity alone (38). Interestingly, some antiviral activity of RIPs has been associated with the B subunit. For instance, ricin can agglutinate hog cholera virus (a small RNA virus) due to a galactose-binding ability of B subunit (43). Ricin was also able to agglutinate cells of a variety of leukemic cell lines, including NIH 3T3 cells infected with Moloney leukemia virus (35).

Elucidation of the mechanism by which the A subunit enters cells was beyond the scope of this investigation. However, it is possible that Stx1A uptake by target cells in our experiments was facilitated by the cell membrane perforation. A variety of mammalian cells infected by virus display this type of increased membrane permeability (21), and it may occur in cells with replicating BLV. Another possibility is that internalization of Stx1A by target cells involved nonspecific endocytosis. This mechanism could explain the fact that proliferation of PWM-induced normal PBMC was somewhat reduced by high concentration of Stx1A. Since SLP is preceded by de novo synthesis of BLV proteins, the elevated metabolism of cells expressing BLV could increase the susceptibility of these cells to Stx1A. However, internalization of Stx1A by nonspecific endocytosis does not explain all of our findings. Specifically, endocytosis does not account for the fact that the spontaneously proliferating cultures became less sensitive to Stx1A within 24 h of preculture without the toxin, and it does not explain the inhibition of SLP by Stx1A used at concentrations which only marginally affected the proliferation of normal PBMC. These findings imply that BLV-expressing cells are exceedingly sensitive to Stx1 and that the toxin acts via a selective mechanism.

Very little information exists regarding the action of Stx1 on bovine cells. A recent publication (40) describes the impact of Stx1 on the metabolic rate of the bovine leukemic cell line BL-3 and on normal bovine PBMC. In both cell types, the metabolism was reduced by Stx1A but only if basal metabolism was first increased by a mitogen such as PWM, ConA, or phytohemagglutinin or by LPS. If cell metabolism was not stimulated to increase, Stx1 had no effect on basal metabolic rate. In agreement with our results, Menge et al. did not detect a cytotoxic impact of Stx1 on PBMC, even when Stx1 caused a 50% reduction of the metabolic rate (40). Since these authors did not clarify the BLV status of their PBMC donors, it is possible that these effects were due to antiviral activity of Stx1. Interestingly, the authors state that the BL-3 cell line was secondarily infected with BLV and with bovine diarrhea virus; however, the BLV activation in these BL-3 cells was not characterized.

BLV infections in cattle are chronic, and in most animals the disease does not progress to the malignant stage. Although antibodies to BLV are clearly important in viral repression (8, 47), they do not always prevent progression of BLV infection to the PL and malignant stages. Consequently, other factors interfering with BLV replication may play a role in a suppression of this virus. Our results indicate that Stx1 may serve a protective role in BLV-infected cows. Gastrointestinal STEC release toxin systemically, because cattle have anti-Stx antibodies in serum and colostrum (46). More evidence to support the movement of the toxin out of the gastrointestinal tract comes from tissue culture experiments. Biologically active Stx1 is capable of moving across a monolayer of intact polarized human intestinal epithelial cells (2), which suggests that Stx1 may also be capable of crossing the intestine in cattle harboring STEC. Stx1 is not cytotoxic to normal bovine PBMC (40), and consequently the presence of Stx in tissues or body fluids of cattle harboring BLV could benefit these animals by causing deletion of the BLV-expressing cells and/or inhibiting viral protein expression and propagation.

These findings have implications for the pathogenesis and epidemiology of STEC as well as maintenance of its bovine reservoir. Ultimately, analyses to correlate gastrointestinal STEC and/or systemic Stx with a delayed progression of BLV disease are needed to demonstrate a selective advantage for cattle to harbor STEC. Future work is planned to assess the antiviral activity of other members of the Shiga toxin family and to more thoroughly study the role of previously identified enzymatic and translocation domains of the Stx1A subunit in antiviral activity (15, 27, 52).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Idaho Agriculture Experiment Station, Public Health Service grant AI33981 from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Agriculture NRICGP grant 95-37201-1979, and grants from the United Dairymen of Idaho and the Idaho Beef Council.

We thank Diana M. Stone and Linda L. Norton for comments and suggestions and for providing blood from BLV-infected cows. The technical expertise of P. R. Austin in providing purified Stx1 is greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Publication no. 00529 of the Idaho Agriculture Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson D W K, Keusch G T. Which Shiga toxin-producing types of E. coli are important? ASM News. 1996;62:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acheson D W K, Moore R, DeBreucker S, Lincicome L, Jacewicz M, Skutelsky E, Keusch G T. Translocation of Shiga toxin across polarized intestinal cells in tissue culture. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3294–3300. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3294-3300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin P R, Hovde C J. Purification of recombinant Shiga-like toxin type I B subunit. Protein Expr Purif. 1995;6:771–779. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baliga V, Ferrer J F. Expression of the bovine leukemia virus and its internal antigen in blood lymphocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1977;156:388–391. doi: 10.3181/00379727-156-39942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bast D J, Sandhu J, Hozumi N, Barber B, Brunton J. Murine antibody responses to the verotoxin 1 B subunit: demonstration of major histocompatibility complex dependence and an immunodominant epitope involving phenylalanine 30. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2978–2982. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2978-2982.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutin L, Geier D, Steinriick H, Zimmermann S, Scheutz F. Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy domestic animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2483–2488. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2483-2488.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser M F, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrant R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruck C, Rensonnet N, Portetelle D, Cleuter Y, Mammerickx M, Burny A, Mamoun R, Guillemain B, van der Maaten M J, Ghysdael J. Biologically active epitopes of bovine leukemia virus glycoprotein gp51: their dependence on protein glycosylation and genetic variability. Virology. 1984;136:20–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byers V S, Levin A S, Malvino A, Waites L, Robins R A, Baldwin R W. A phase II study of effect of addition of trichosanthin to zidovudine in patients with HIV disease and failing antiretroviral agents. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:413–420. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calderwood S B, Auclair F, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T, Mekalanos J J. Nucleotide sequence of the Shiga-like toxin genes of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4364–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee R, Gupta P, Kashmiri S V, Ferrer J F. Phytohemagglutinin activation of the transcription of the bovine leukemia virus genome requires de novo protein synthesis. J Virol. 1985;54:860–863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.3.860-863.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cray W C, Jr, Moon H W. Experimental infection of calves and adult cattle with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1586–1590. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1586-1590.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cray W C, Jr, Thomas L A, Schneider R A, Moon H W. Virulence attributes of Escherichia coli isolated from dairy heifer feces. Vet Microbiol. 1996;53:369–374. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis W C, Naessens J, Brown W C, Ellis J A, Hamilton M J, Cantor G H, Barbosa J I, Ferens W, Bohach G A. Analysis of monoclonal antibodies reactive with molecules upregulated or expressed only on activated lymphocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;52:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(96)05581-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deresiewicz R L, Calderwood S B, Robertus J D, Collier R J. Mutations affecting the activity of the Shiga-like toxin I A-chain. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3272–3280. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driscoll D M, Onuma M, Olson C. Inhibition of bovine leukemia virus release by antiviral antibodies. Arch Virol. 1977;55:139–144. doi: 10.1007/BF01314487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endo Y, Mitsui K, Motizuki M, Tsurugi K. The mechanism of action of ricin and related toxic lectins on eukaryotic ribosomes. The site and the characteristics of the modification in 28 S ribosomal RNA caused by the toxins. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5908–5912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endo Y, Tsurugi K, Yutsudo T, Takeda Y, Ogasawara T, Igarashi K. Site of action of a Vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and of Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. RNA N-glycosidase activity of the toxins. Eur J Biochem. 1988;171:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteban E N, Thorn R M, Ferrer J F. Characterization of the blood lymphocyte population in cattle infected with the bovine leukemia virus. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3225–3230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferens W A, Davis W C, Hamilton M J, Park Y H, Deobald C F, Fox L, Bohach G. Activation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations by staphylococcal enterotoxin C. Infect Immun. 1998;66:573–580. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.573-580.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Puentes C, Carrasco L. Viral infection permeabilizes mammalian cells to protein toxins. Cell. 1980;20:769–775. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrer J F. Bovine lymphosarcoma. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1980;24:1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrer J F, Marshak R R, Abt D A, Kenyon S J. Relationship between lymphosarcoma and persistent lymphocytosis in cattle: a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175:705–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta P, Kashmiri S V, Ferrer J F. Transcriptional control of the bovine leukemia virus genome: role and characterization of a non-immunoglobulin plasma protein from bovine leukemia virus-infected cattle. J Virol. 1984;50:267–270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.1.267-270.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heuvelink A E, van den Biggelaar F L, Zwartkruis-Nahuis J, Herbes R G, Huyben R, Nagelkerke N, Melchers W J, Monnens L A, de Boer E. Occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 on Dutch dairy farms. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3480–3487. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3480-3487.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hino M, Sekizawa T, Openshaw H. Ricin injection eliminates latent herpes simplex virus in the mouse. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:1270–1271. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.6.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hovde C J, Calderwood S B, Mekalanos J J, Collier R J. Evidence that glutamic acid 167 is an active-site residue of Shiga-like toxin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2568–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igarashi K, Ogasswara T, Ito K, Yutsudo T, Takada Y. Inhibition of elongation factor-1 dependent aminoacyl-tRNA binding to ribosomes by Shiga-like toxin I (VTI) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and by Shiga toxin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson M. Structure-function analyses of Shiga toxin and the Shiga-like toxins. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen W A, Sheehy S E, Fox M H, Davis W C, Cockerell G L. In vitro expression of bovine leukemia virus in isolated B-lymphocytes of cattle and sheep. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;26:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90117-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaper J B, O'Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerkhofs P, Adam E, Droogmans L, Portetelle D, Mammerickx M, Burny A, Kettmann R, Willems L. Cellular pathways involved in the ex vivo expression of bovine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1996;70:2170–2177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2170-2177.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kettmann R, Portetelle D, Mammerickx M, Cleuter Y, Dekegel D, Galoux M, Ghysdael J, Burny A, Chantrenne H. Bovine leukemia virus: an exogenous RNA oncogenic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1014–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kidd L C, Radke K. Lymphocyte activators elicit bovine leukemia virus expression differently as asymptomatic infection progresses. Virology. 1996;217:167–177. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koga M, Ohtsu M, Funatsu G. Cytotoxic, cell agglutinating, and syncytium forming effect of purified lectins from Ricinus communis on cultured cells. Gann. 1979;70:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudva I T, Hatfield P G, Hovde C J. Characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli isolated from sheep. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;35:892–899. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.892-899.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee-Huang S, Huang P L, Bourinbaiar A S, Chen H C, Kung H F. Inhibition of the integrase of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 by anti-HIV plant proteins MAP30 and GAP31. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8818–8822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee-Huang S, Kung H F, Huang P L, Bourinbaiar A S, Morell J L, Brown J H, Tsai W P, Chen A Y, Huang H I, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) inhibition, DNA-binding, RNA-binding, and ribosome inactivation activities in the N-terminal segments of the plant anti-HIV protein GAP31. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12208–12212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy D, Kettmann R, Marchand P, Djilali S, Parodi A L. Selective tropism of bovine leukemia virus (BLV) for surface immunoglobulin-bearing ovine B lymphocytes. Leukemia. 1987;1:463–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menge C, Wieler L H, Schlapp T, Baljer G. Shiga toxin 1 from Escherichia coli blocks activation and proliferation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations in vitro. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2209–2217. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2209-2217.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirsky M L, Olmstead C A, Da Y, Lewin H A. The prevalence of proviral bovine leukemia virus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells at two subclinical stages of infection. J Virol. 1996;70:2178–2183. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2178-2183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montenegro M A, Biilte M, Trumpf T, Aleksic S, Reuter G, Bulling E, Helmuth R. Detection and characterization of fecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1417–1421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1417-1421.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neukirch M, Moennig V, Liess B. A simple procedure for the concentration and purification of hog cholera virus (HCV) using the lectin of Ricinus communis. Arch Virol. 1981;69:287–290. doi: 10.1007/BF01317343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obrig T G, Louise C B, Lingwood C A, Boyd B, Barley-Maloney L, Daniel T O. Endothelial heterogeneity in Shiga toxin receptors and responses. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15484–15488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson M C, Ramakrishnan S, Anand R. Ribosomal inhibitory proteins from plants inhibit HIV-1 replication in acutely infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:1025–1030. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirro F, Wieler L H, Failing K, Bauerfeind R, Baljer G. Neutralizing antibodies against Shiga-like toxins from Escherichia coli in colostra and sera of cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1995;43:131–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00089-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portetelle D, Bruck C, Mammerickx M, Burny A. In animals infected by bovine leukemia virus (BLV) antibodies to envelope glycoprotein gp51 are directed against the carbohydrate moiety. Virology. 1980;105:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pradel N, Livrelli V, De Champs C, Palcoux J B, Reynaud A, Scheutz F, Sirot J, Joly B, Forestier C. Prevalence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle, food, and children during a one-year prospective study in France. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1023–1031. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1023-1031.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ready M P, Katzin B J, Robertus J D. Ribosome-inhibiting proteins, retroviral reverse transcriptases, and RNase H share common structural elements. Proteins. 1988;3:53–59. doi: 10.1002/prot.340030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ready M P, Kim Y, Robertus J D. Site-directed mutagenesis of ricin A-Chain and implications for the mechanism of action. Proteins Struct Func Genet. 1991;10:270–278. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stirpe F, Barbieri L, Battelli M G, Soria M, Lappi D A. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from plants: present status and future prospects. BioTechnology. 1992;10:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nbt0492-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suhan M L, Hovde C J. Disruption of an internal membrane-spanning region in Shiga toxin 1 reduces cytotoxicity. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5252–5259. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5252-5259.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takashima I, Olson C. Relation of bovine leukosis virus production on cell growth cycle. Arch Virol. 1981;69:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01315157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorn R M, Gupta P, Kenyon S J, Ferrer J F. Evidence that the spontaneous blastogenesis of lymphocytes from bovine leukemia virus-infected cattle is viral antigen specific. Infect Immun. 1981;34:84–89. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.1.84-89.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trueblood E S, Brown W C, Palmer G H, Davis W C, Stone D M, McElwain T F. B-lymphocyte proliferation during bovine leukemia virus-induced persistent lymphocytosis is enhanced by T-lymphocyte-derived interleukin-2. J Virol. 1998;72:3169–3177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3169-3177.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wachinger M, Samtleben R, Gerhauser C, Wagner H, Erfle V. Bryodin, a single-chain ribosome-inactivating protein, selectively inhibits the growth of HIV-1-infected cells and reduces HIV-1 production. Res Exp Med. 1993;193:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02576205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zandomeni R O, Carrera-Zandomeni M, Esteban E, Donawick W, Ferrer J F. Induction and inhibition of bovine leukaemia virus expression in naturally infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1915–1924. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zollman T M, Austin P R, Jablonski P E, Hovde C J. Purification of recombinant Shiga-like toxin type I A1 fragment from Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1994;5:291–295. doi: 10.1006/prep.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]