Abstract

Direct and indirect costs of care influence patients’ health choices and the ability to implement those choices. Despite the significant impact of care costs on patients’ health and daily lives, patient decision aid (PtDA) and shared decision-making (SDM) guidelines almost never mention a discussion of costs of treatment options as part of minimum standards or quality criteria. Given the growing study of the impact of costs in health decisions and the rising costs of care more broadly, in fall 2021 we organized a symposium at the Society for Medical Decision Making’s annual meeting. The focus was on the role of cost information in PtDAs and SDM. Panelists gave an overview of work in this space at this virtual meeting, and attendees engaged in rich discussion with the panelists about the state of the problem as well as ideas and challenges in incorporating cost-related issues into routine care. This article summarizes and extends our discussion based on the literature in this area and calls for action. We recommend that PtDA and SDM guidelines routinely include a discussion of direct and indirect care costs and that researchers measure the frequency, quality, and response to this information.

Keywords: shared decision making, patient decision aids, cost conversations, financial toxicity

Given the growing study of the impact of costs on health decisions and the rising costs of care more broadly, in fall 2021, we organized a symposium at the Society for Medical Decision Making’s annual meeting. The focus was on the role of cost information in patient decision aids (PtDAs) and shared decision making (SDM). Panelists gave an overview of work in this space at this virtual meeting, live streamed and available as a recording for several months. Attendees engaged in rich discussion with the panelists about the state of the problem as well as ideas and challenges in incorporating cost-related issues into routine care. In this article, several of the presenters at the symposium (M.C.P., R.C.F., J.J.) and 2 other thought leaders in the field (A.J.H. and G.E.) who attended the session and helped contribute to the ideas presented and ongoing work in this space summarize the key themes from the discussion. We build on the ideas discussed in the symposium, including questions and comments raised by attendees, expand on it with key references and literature in this area, and call for specific guidance and resources to facilitate a discussion of cost as part of SDM and PtDA standards.

Over the past decade, many people have highlighted the substantial psychological, social, behavioral, and health-related impacts of the rising costs of health care.1 Financial toxicity is often described as the cost-related hardship and associated burden of those costs on patients. It is associated with delaying or forgoing care deemed necessary2,3 and skipping prescribed medications,4 and it even influences mortality.5 Financial toxicity can lead patients to reduce their spending on other needs such as heating, food, clothing, childcare, and leisure activities.6 Indirect costs of care, including missing work to get tests or attend clinical encounters, can exacerbate the financial strain on patients and their families.7 A patient with breast cancer in one of our studies commented, “It’s a big financial burden . . . ‘cause you don’t stop. You know . . . this is an ongoing thing. I mean, you develop so many other things after you even have the cancer . . . [so] do I want to go forward with [treatment] because of the financial piece of it? It’s a big part of it.”8 Another commented, “You know, it took about three-and-a-half years to pay off my surgeries.”8 Although financial toxicity is often discussed in the context of cancer, it also affects patients with long-term illnesses such as hepatitis C virus, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.9–11

Financial toxicity is an international problem,12–16 but it is more pronounced in the United States given the lack of universal insurance coverage and high out-of-pocket costs even among those with insurance.17,18 More than 30 million people in the United States lack insurance to cover any of the costs of care.19 However, clinicians are typically hesitant to address costs as part of routine discussions.20 In one of our studies in the context of breast cancer treatment decisions, we found that clinicians initiated cost discussions as part of SDM only about one-third of the time, compared with two-thirds of the time with training and an intervention prompting a cost discussion.21 Similarly, in a study of almost 2000 outpatient visits about care for mental health, arthritis, or cancer, only about 30% of encounters discussed costs.22 When clinicians and patients do discuss costs, though, they are often able to identify strategies to lower those costs.22,23 Patients often appreciate when clinicians address costs as part of treatment discussions, finding them trustworthy, honest, and transparent when they do.24

When clinicians do not initiate cost discussions, many patients feel the need to ask questions about costs to prepare for their bills or find out about lower-cost, effective options. One patient in a study about cancer treatment and its associated costs told us,

It was helpful to ask questions. . . . A nurse came back, and said, “Wow, I can’t believe it’s $100.00 [for 5 days of the medication]. Let me see what I can do.” They had some benefit card, and then it ended up being nothing. . . . They wouldn’t have said anything, though, if I hadn’t said like, “Wow, that’s a lot for a medication for five days.” I would’ve just ended up paying it. . . . Nobody tells you if you don’t ask.”25

Yet patients worry that talking about costs will make them appear as if they do not value or prioritize their health or that they may be suspicious of being offered substandard care.26,27 They often feel embarrassed or ashamed that cost is a factor affecting their choices.27,28 Many with limited health literacy or limited health insurance literacy might not know how to prompt this discussion. Patients should not be tasked with initiating cost discussions and coping with the anxiety associated with medical bills and debt on top of an illness.25,29

In addition to talking about upfront direct costs, there are many indirect and downstream costs and challenges that can affect patients’ care choices and the value of those choices. Patients with multiple chronic conditions can become overwhelmed by the impact of care on their daily lives when it involves many uncoordinated appointments, complex medication regimens, and the responsibility of undertaking at-home interventions.30 The burden of care choices can affect both direct costs (e.g., cost for copayments, medications, support services, home health aides) as well as indirect costs (e.g., time off work, transportation, time off caregiving duties, and disruption to one’s daily routine). Discussing the impact of a choice that an individual makes, beyond the physical pros and cons of how well it works to treat an illness and associated side effects, can facilitate “care that fits” each individual patient and family.31 Discussing the practical issues that affect the implementation of patients’ choices, from monetary costs to care coordination to the impact on one’s social life and relationships, can help guide patients’ preference-consistent decisions.32 Costs extend beyond the monetary impact of one’s immediate health care choice. Table 1 summarizes the importance of costs during shared decision making.

Table 1.

Summary of Importance of Direct and Indirect Costs of Care and Shared Decision Making

| Financial toxicity (burden of high costs of care) is prevalent across conditions and countries1–16 |

| Clinicians rarely bring up costs without prompts and training |

| Patients want clinicians to bring up costs as part of treatment discussions, in some contexts finding clinicians trustworthy, honest, and transparent when they address costs24 |

| Patients often worry that if they bring up cost, it will lead to biases and lower-quality care26–28 |

| Patient decision aids and standards rarely include relative costs to compare options53,54 |

| When costs are discussed, they rarely include downstream direct or indirect costs (e.g., costs that build over time, relating to frequent monitoring or ongoing morbidity)31 |

| Making space to ask about costs supports broader care goal conversations and practical issues affecting implementation31,32,55 |

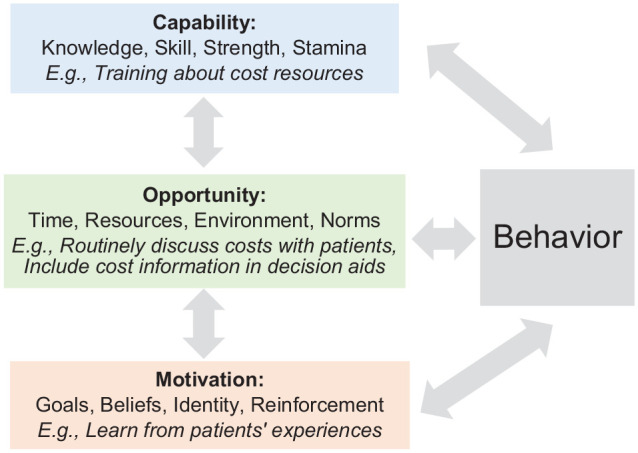

Barriers to Addressing Cost and Value during SDM

To change behavior, individuals need capability (e.g., knowledge, skills), opportunity (e.g., social norms, support, incentives), and motivation (e.g., perceived value, self-efficacy; see Figure 1).33,34 Despite recognizing its importance, some researchers have suggested that patients, clinicians, and PtDA developers cannot discuss the direct costs of care because they do not have the capability or knowledge of each individual’s health care expenses given the complexity of insurance, especially in the United States. In the United States, individuals are responsible for various amounts of the total cost of care, from a flat copayment to a percentage of the total cost, to all of the costs of care up to a certain amount of their calendar year deductible.35–37 Patients are not always able to find health insurance plans that meet their needs,38–40 and both clinicians and patients can be surprised by patients’ care cost responsibility on top of premiums (monthly bills) to maintain insurance.41 In other words, many in the United States remain underinsured even if they have insurance to help offset bills.17,29,36 This burden affects patients across income levels, including those 400% to 600% above the federal poverty level.37 One insured patient with cancer commented, “I had to write a $600 check the other day for them to do that biopsy.”42 Her clinician was shocked. Another patient with colorectal cancer commented, “The medications are quite expensive. We ended up having to pay quite a bit for that, almost $2,000 out-of-pocket, even though the insurance did cover quite a bit. It was still very expensive.”25 There are some researchers and organizations that have incorporated direct costs into comparator tools and decision aids,43–46 but generating personalized cost estimates and updating them over time is complex and requires substantial resources to maintain.

Figure 1.

Capacity & Opportunity & Motivation – Behavior model of behavior change as applied to cost discussions.33,34

In addition, some lack motivation to incorporate costs into SDM given limited opportunity associated with external structures and social norms. Perhaps some disagree with including cost information as part of treatment discussions because they consider it a form of “rationing” health care, something that is laden with political and societal implications. One grant reviewer of a federal agency in 2021, when discussing the significance of a proposal that aimed to prompt cost discussions during SDM, commented, “We have built a health care system where patients and physicians can choose treatment options based on clinical criteria and not be biased on costs; therefore, introducing cost conversation prior to treatment decision seems contrary to the philosophy of our health care system.” Such comments dismiss the fact that in the absence of high-quality insurance policies, direct health care costs are unaffordable to most people. It is clear that rationing care happens routinely based on the affordability of care. Increased cost sharing and out-of-pocket costs lead patients to forgo needed care, a form of self-rationing.47 Discussing costs, especially when there are alternative lower-cost, similarly effective options, can help improve care.6,48

Others object to incorporating practical issues and indirect care costs because of limited evidence about the impact of doing so. There have been recent movements to address this limitation through engaging patients as partners in evidence summaries, using a framework to systematically and rigorously screen, search, and identify relevant evidence about practical issues patients face upon implementing care choices and following a framework to explore the most meaningful practical issues to patients.32 For example, in addition to out-of-pocket cost information, understanding the logistical details and possible side effects of treatment can inform patients’ transportation arrangements, coverage for household and family responsibilities, and accommodations at work. In the case of cancer, patients are more likely than their peers to be unemployed,49 and up to 63% of people with cancer make employment changes.50,51 Using systematic processes to shape and apply relevant evidence can improve the opportunity, social norms, and capability or self-efficacy for incorporating indirect costs into care.

A Call to Action for SDM and PtDA Guidelines

We propose several recommendations to include cost information as part of informed consent for treatment,52 PtDAs, and SDM (see Table 2). We also propose that experts conduct a systematic review to identify when and how PtDAs address costs of care to build on this work and create practical guidelines and standards for incorporating costs in ways that are feasible, acceptable, and sustainable.

Table 2.

Summary of Action Items to Support Cost Conversations during Shared Decision Making

| Include cost information in patient decision aids and shared decision-making guidelines |

| Train those involved in decision discussions to mention direct and indirect costs with all patients; referrals can be made for more details when needed given time constraints in clinical encounters |

| Engage stakeholders to propose solutions to cost transparency at multiple levels of the care system that extend beyond current legislation and focus on translating this start into routine care |

| Measure the impact of direct and indirect cost information on decision quality and outcomes |

First, PtDA and SDM guidelines should include direct and indirect cost information.32 Although the latest Ottawa Decision Support Framework and International Patient Decision Aids Standards update discusses implementation challenges and costs to the health care system in the form of health care use/overuse, they do not explicitly mention the cost burden on patients.54 Ideally, PtDAs should support identifying patients’ direct costs or possible range of costs. Although some tools have started to include cost information, the discussion is often limited to phrases such as “check with your insurance about your costs for this treatment.” In the United States, costs are both opaque and potentially financially crippling to patients. In other countries with more universal health insurance coverage, guidelines should address where to identify out-of-pocket costs for patients and the person on the care team responsible for doing so.

When possible, identifying out-of-pocket costs for patients is ethical and necessary to support patients through health choices. However, if precise costs are not yet known, clinicians and PtDA developers need not understand patients’ exact costs or the exact practical burden on patients’ lives in order to talk about relative costs of care or lower-cost care options. For example, some tools list the out-of-pocket costs without insurance such that patients can view their relative costs.57,58 After discussing relative costs of options (or more precise costs if known or included from insurance support and/or cost comparison tools43,45,46,59), there are referrals that clinicians or PtDAs can suggest for members of care teams that can help patients navigate the specific direct or indirect cost implications of care (e.g., social workers, financial navigators, insurance representatives, community resources), although few currently do so.21,48 By mentioning costs and helping patients consider those costs in the context of SDM, patients could seek support earlier to better prepare for direct and indirect costs, should they continue to choose or need expensive or burdensome care.6,32 Even in situations in which the costs are roughly equivalent between options, patients often need or want to know that so that they can focus on factors that differ between options. Supporting clinicians in understanding their capability to discuss costs, even when exact costs are unknown or costs are similar, can be a first step providing space and opportunity to normalize these conversations. It can build motivation and value in engaging in these conversations.

When the field of PtDAs was new, many were hesitant to include probabilities associated with outcomes of options, stating that numeric population-based estimates of risk and possible outcomes are hard to quantify and do not always apply to individuals with varying risk factors.60,61 The field soon realized that PtDA developers can make the best effort to identify the highest-quality evidence, acknowledging individual variation or uncertainty about point estimates and/or confidence intervals. Many have studied how to convey this uncertainty in PtDAs or SDM conversations.62,63 For several decades, SDM and PtDA guidelines have stated that numeric probabilities, when available, should be included in SDM discussions and PtDAs so as not to bias patients’ risk/benefit perception.64,65 Even when the evidence is conflicting or limited, guidelines suggest including the best possible information because it is so essential to patients’ choices. Omitting necessary information can bias patients’ choices, implementation of those choices, and outcomes of those choices. PtDA and SDM leaders should provide the same guidance about cost discussions using the best available models and evidence.

Next, we propose training those engaging in SDM to include a discussion of direct and indirect costs. At the core of SDM is ensuring that patients make decisions that are aligned with their values, preferences, and context.66 A high-value treatment that offers good clinical outcomes and is favored by the clinician can become of low value to an individual patient if the negative consequences and cost of that treatment outweigh the clinical benefit. To ensure that a treatment has the highest possible value for a patient, it is essential to understand and appreciate the effect treatment has on the patient’s life to limit the negative impact as much as possible. When the direct or indirect costs to the patient are burdensome, patients often have higher expectations for the potential benefits that can be gained from treatment. Thus, costs should be considered when making a benefit/harm tradeoff during SDM, and training should directly address the importance of costs during decision making.

We and others recommend initiating cost conversations with all patients, rather than waiting for patients to bring up costs.6,48,55 Patients might wait until there is a crisis or critical need to bring up the impact of costs on their lives. Yet many experience cost-related burdens, and addressing costs upfront can facilitate discussions about broader care needs and goals. It also creates the opportunity to normalize talking about cost, value, and burden such that if costs become a problem later on, patients know there is space to seek support.55 Initiating the discussion need not add much time to the encounter, but it can start the conversation and identify implementation challenges; others on the care team can continue to address cost or practical burden on patients.

When affecting change, the first step involves acknowledging and understanding the problem and its impact.67 Clinician training in cost conversations should include data on the range of adjustments patients make to address the high cost or burden of care. For example, many clinicians are surprised to learn that patients ration medications or spend less on basic needs to pay for care.68 Training can highlight how common these financial stresses are by discussing the number of individuals with medical debt and medical bankruptcy69 and how that affects patients’ quality of life, employment, social and emotional health, and overall health outcomes.

After understanding the problem and its impact, the next part of the change process should include stakeholder engagement to foster communication and propose solutions at different levels of the health care system.67 At the hospital level, we call for including more cost transparency by engaging financial counselors or navigators to discuss patient-level direct costs upfront. This process can serve as a natural extension to recent guidelines calling for more cost transparency70,71; implementation of that often results in posting opaque costs to hospital websites that do not always help patients understand their specific bills or care needs. At the patient level, we can provide support for patients exploring insurance coverage options, seeking financial assistance from foundations and company-sponsored programs, and asking questions about the direct and indirect costs of care. We should also consider our work at the social and policy levels of influence. Evidence generated through ongoing financial strain research can help inform policy approaches that influence health insurance, calling for more universal coverage, and the health care system. Overall, the goal is to improve capability, opportunity, and motivation to address both direct and indirect costs of care.

From a research design perspective, we recommend measuring the impact of direct and indirect cost conversations during SDM and in PtDAs. Many have described the problem, but few have provided actionable solutions and tested those during clinical encounters or health decision making. Measurement can include the quality of the specific SDM encounter and PtDA, but it also extends beyond just a single encounter with a patient. Measuring the frequency of cost conversations and their impact over time is needed to gauge how patients respond to these conversations and better understand their cost-related burden, which might change after they make a treatment decision. Patients’ experience can be dynamic as their health condition, insurance, and financial well-being continue to evolve after the treatment decision. Those that have incorporated longer-term measurement of the overall care burden have shown promising results.55

Conclusion

We cannot afford to wait for patients to discuss costs after problems arise. Many with limited health literacy or fear of being mistreated or judged could stay silent even as the costs of care and burden of those costs build over time. Cost is often mentioned after patients are described as “nonadherent,” as a possible reason why a treatment did not work.55 This delay can contribute to health disparities for the most vulnerable patients or those who hesitate to describe challenges to care implementation. We can think of no other sphere of life in which costs are both opaque and potentially crippling financially. It is time for the field to address this glaring omission and provide recommendations, guidance, and standards for including direct and indirect costs into PtDAs and SDM conversations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Peter Ubel who was part of the 2021 symposium discussion panel that led to this article.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Politi was a consultant for UCB BioPharma in 2022. Dr. Elwyn has developed Option Grid patient decision aids, which are licensed to EBSCO Health. He receives consulting income from EBSCO Health and may receive royalties.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided in part by the Center for Collaborative Care Decisions, which is supported by the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital (award No. 5799) and the Department of Surgery’s Surgery and Public Health Research (SPHeRe) Collaborative. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in writing and publishing the report. Funding for open access for this article was made possible by grant R13HS027098 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The views expressed in publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

ORCID iDs: Mary C. Politi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9103-6495

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9103-6495

Ashley J. Housten  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7379-0678

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7379-0678

Jesse Jansen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7739-0049

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7739-0049

Contributor Information

Mary C. Politi, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, MO, USA.

Ashley J. Housten, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, MO, USA

Rachel C. Forcino, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

Jesse Jansen, School for Public Health and Primary Care CAPHRI, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Glyn Elwyn, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA.

References

- 1. Hamel L, Norton M, Pollitz K, Levitt L, Claxton G, Brodie M; Kaiser Family Foundation. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. Menlo Park (CA): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas A, Valero-Elizondo J, Khera R, et al. Forgone medical care associated with increased health care costs among the U.S. heart failure population. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9(10):710–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knight TG, Deal AM, Dusetzina SB, et al. Financial toxicity in adults with cancer: adverse outcomes and noncompliance. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(11):e665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1484–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mols F, Tomalin B, Pearce A, Kaambwa B, Koczwara B. Financial toxicity and employment status in cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(12):5693–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boateng J, Lee CN, Foraker RE, et al. Implementing an electronic clinical decision support tool into routine care: a qualitative study of stakeholders’ perceptions of a post-mastectomy breast reconstruction Tool. MDM Policy Pract. 2021;6(2):23814683211042010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. George N, Liapakis A, Korenblat KM, et al. A patient decision support tool for hepatitis C virus and CKD treatment. Kidney Med. 2019;1(4):200–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slavin SD, Khera R, Zafar SY, Nasir K, Warraich HJ. Financial burden, distress, and toxicity in cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2021;238:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rat A-C, Boissier M-C. Rheumatoid arthritis: direct and indirect costs. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Honda K, Gyawali B, Ando M, et al. Prospective survey of financial toxicity measured by the comprehensive score for financial toxicity in Japanese patients with cancer. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fitch MI, Longo CJ. Emerging understanding about the impact of financial toxicity related to cancer: Canadian perspectives. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2021;37(4):151174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nogueira L, de A, Lenhani BE, Tomim DH, Kalinke LP. Financial toxicity. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(2):289–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gordon LG, Walker SM, Mervin MC, et al. Financial toxicity: a potential side effect of prostate cancer treatment among Australian men. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(1):e12392. DOI: 10.1111/ecc.12392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ngan TT, Van Minh H, Donnelly M, O’Neill C. Financial toxicity due to breast cancer treatment in low- and middle-income countries: evidence from Vietnam. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(11):6325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carroll AE. Opinion. The New York Times, July 7, 2022. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/07/opinion/medical-debt-health-care-cost.html. Accessed 10 August, 2022.

- 18. Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff. 2013;32(12):2205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen RA, Cha AE. Health insurance coverage: early release of quarterly estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January 2021-March 2022. National Center for Health Statistics; July 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/quarterly_estimates_2022_q11.pdf. Accessed 30, December 2022.

- 20. de Moor JS, Williams CP, Blinder VS. Cancer-related care costs and employment disruption: recommendations to reduce patient economic burden as part of cancer care delivery. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2022;2022:79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Politi MC, Yen RW, Elwyn G, et al. Encounter decision aids can prompt breast cancer surgery cost discussions: analysis of recorded consultations. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(1):62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunter WG, Zhang CZ, Hesson A, et al. What strategies do physicians and patients discuss to reduce out-of-pocket costs? analysis of cost-saving strategies in 1,755 outpatient clinic visits. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(7):900–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brown GD, Hunter WG, Hesson A, et al. Discussing out-of-pocket expenses during clinical appointments: an observational study of patient-psychiatrist interactions. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(6):610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brick DJ, Scherr KA, Ubel PA. The impact of cost conversations on the patient-physician relationship. Health Commun. 2019;34:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. George N, Grant R, James A, Mir N, Politi MC. Burden associated with selecting and using health insurance to manage care costs: results of a qualitative study of nonelderly cancer survivors. Med Care Res Rev. 2021;78(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrington NG, Scott AM, Spencer EA. Working toward evidence-based guidelines for cost-of-care conversations between patients and physicians: a systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng C-W, McFadden D, Meltzer DO. Barriers to patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):856–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hardee JT, Platt FW, Kasper IK. Discussing health care costs with patients: an opportunity for empathic communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:666–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rau J. Surprise medical bills are what Americans fear most in paying for health care. Kaiser Health News. 2018. Available from: https://khn.org/news/surprise-medical-bills-are-what-americans-fear-most-in-paying-for-health-care/. Accessed 10 August, 2022.

- 30. Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally disruptive medicine: a pragmatically comprehensive model for delivering care to patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3:50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. care that fits. Minimally disruptive medicine. 2020. Available from: https://carethatfits.org/mdm/. Accessed 10 August, 2022.

- 32. Heen AF, Vandvik PO, Brandt L, et al. A framework for practical issues was developed to inform shared decision-making tools and clinical guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Duan Z, Liu C, Han M, Wang D, Zhang X, Liu C. Understanding consumer behavior patterns in antibiotic usage for upper respiratory tract infections: a study protocol based on the COM-B framework. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(5):978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sinaiko AD, Mehrotra A, Sood N. Cost-sharing obligations, high-deductible health plan growth, and shopping for health care: enrollees with skin in the game. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:395–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wong CA, Polsky DE, Jones AT, Weiner J, Town RJ, Baker T. For third enrollment period, marketplaces expand decision support tools to assist consumers. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):680–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glied SA, Zhu B. Catastrophic out-of-Pocket Health Care Costs: A Problem Mainly for Middle-Income Americans with Employer Coverage. April 2020. DOI: 10.26099/X0CX-CP48 [DOI]

- 38. Hero JO, Sinaiko AD, Kingsdale J, Gruver RS, Galbraith AA. Decision-making experiences of consumers choosing individual-market health insurance plans. Health Aff. 2019;38(3):464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Politi MC, Kaphingst KA, Kreuter M, Shacham E, Lovell MC, McBride T. Knowledge of health insurance terminology and details among the uninsured. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(1):85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adepoju O, Mask A, McLeod A. Factors associated with health insurance literacy: proficiency in finding, selecting, and making appropriate decisions. J Healthc Manag. 2019;64:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kliff S. Surprise medical bills, the high cost of emergency department care, and the effects on patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1457–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hunter WG, Zafar SY, Hesson A, et al. Discussing health care expenses in the oncology clinic: analysis of cost conversations in outpatient encounters. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(11):e944–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Politi MC, Shacham E, Barker AR, et al. A comparison between subjective and objective methods of predicting health care expenses to support consumers’ health insurance plan choice. MDM Policy Pract. 2018;3(1):2381468318781093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Godolphin W. Shared decision-making. Healthc Q. 2009;12:e186–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Clear Health Costs. Home page. 2011. Available from: https://clearhealthcosts.com/. Accessed 10 August.

- 46. Politi MC, Grant RL, George NP, et al. Improving cancer patients’ insurance choices (I can PIC): a randomized trial of a personalized health insurance decision aid. Oncologist. 2020;25(7):609–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chandra A, Flack E, Obermeyer Z. The Health Costs of Cost-Sharing. Working Paper 28439 February 2021. DOI: 10.3386/w28439 [DOI]

- 48. Sloan CE, Ubel PA. The 7 habits of highly effective cost-of-care conversations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:S33–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. de Boer AGEM, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A, van Dijk FJH, Verbeek JHAM. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301(7):753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. de Moor JS, Kent EE, McNeel TS, et al. Employment outcomes among cancer survivors in the United States: implications for cancer care delivery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(5):641–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, Chubak J. Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):1104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pierson L, Pierson E. Patients cannot consent to care unless they know how much it costs. BMJ. 2022;378:o1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(4):CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa decision support framework: part 3 overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(3):379–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Espinoza Suarez NR, LaVecchia CM, Morrow AS, et al. ABLE to support patient financial capacity: a qualitative analysis of cost conversations in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(11):3249–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Venechuk GE, Allen LA, Doermann Byrd K, Dickert N, Matlock DD. Conflicting perspectives on the value of neprilysin inhibition in heart failure revealed during development of a decision aid focusing on patient costs for sacubitril/valsartan. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(9):e006255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. care that fits. Diabetes medication choice. 2020. Available from: https://carethatfits.org/diabetes-medication-choice/. Accessed 2 November, 2022.

- 58. care that fits. Anticoagulation choice. 2020. Available from: https://carethatfits.org/anticoagulation-choice/. Accessed 2 November, 2022.

- 59. FAIR Health Consumer. Shared decision making. Available from: https://www.fairhealthconsumer.org/shared-decision-making. Accessed 11 August, 2022.

- 60. Rockhill B. Theorizing about causes at the individual level while estimating effects at the population level: implications for prevention. Epidemiology. 2005;16:124–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Diamond GA. What price perfection? Calibration and discrimination of clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:85–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Han PKJ, Strout TD, Gutheil C, et al. How physicians manage medical uncertainty: a qualitative study and conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(3):275–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Han PKJ, Klein WMP, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:828–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bonner C, Trevena LJ, Gaissmaier W, et al. Current best practice for presenting probabilities in patient decision aids: fundamental principles. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(7):821–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Coughlin SS, Moore JX, Cortes JE. Addressing financial toxicity in oncology care. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2021;5:32. DOI: 10.21037/jhmhp-20-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Herrick CJ, Humble S, Hollar L, et al. Cost-related medication non-adherence, cost coping behaviors, and cost conversations among individuals with and without diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(9):2867–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. US Census Bureau. 19% of U.S. households could not afford to pay for medical care right away. 2022. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/who-had-medical-debt-in-united-states.html. Accessed 12 August, 2022.

- 70. The General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Section 228. Available from: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXVI/Chapter111/Section228. [Accessed 2 November, 2022].

- 71. CMS.gov. Hospital price transparency. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/hospital-price-transparency. Accessed 2 November, 2022.