Abstract

Aim:

Our previous studies have demonstrated the importance of dietary factors in the determination of hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats. Since the gut microbiota has been implicated in chronic diseases like hypertension, we hypothesized that dietary alterations shift the microbiota to mediate the development of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease.

Methods:

This study utilized SS rats from the Medical College of Wisconsin (SS/MCW) maintained on a purified, casein-based diet (0.4% NaCl AIN-76A, Dyets) and from Charles River Laboratories (SS/CRL) fed a whole grain diet (0.75% NaCl 5L79, LabDiet). Faecal 16S rDNA sequencing was used to phenotype the gut microbiota. Directly examining the contribution of the gut microbiota, SS/CRL rats were administered faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) experiments with either SS/MCW stool or vehicle (Vehl) in conjunction with the HS AIN-76A diet.

Results:

SS/MCW rats exhibit renal damage and inflammation when fed high salt (HS, 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A), which is significantly attenuated in SS/CRL. Gut microbiota phenotyping revealed distinct profiles that correlate with disease severity. SS/MCW FMT worsened the SS/CRL response to HS, evidenced by increased albuminuria (67.4 ± 6.9 vs 113.7 ± 25.0 mg/day, Vehl vs FMT, P = .007), systolic arterial pressure (158.6 ± 5.8 vs 177.8 ± 8.9 mmHg, Vehl vs FMT, P = .09) and renal T-cell infiltration (1.9-fold). Amplicon sequence variant (ASV)-based analysis of faecal 16S rDNA sequencing data revealed taxa that significantly shifted with FMT: Erysipelotrichaceae_2, Parabacteroides gordonii, Streptococcus alactolyticus, Bacteroidales_1, Desulfovibrionaceae_2, Ruminococcus albus.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate that dietary modulation of the gut microbiota directly contributes to the development of Dahl SS hypertension and renal injury.

Keywords: diet, faecal microbiota transfer, gut microbiota, hypertension, immune cells

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

High blood pressure is the largest modifiable risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD), where in accordance with the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, 46% of the US population is now estimated to have hypertension.1 Approximately 30%-50% of these individuals experience a ≥10% increase in blood pressure in response to high sodium intake and are considered to have salt-sensitive hypertension.2,3 In African Americans, the prevalence of salt-sensitive hypertension is greatly enhanced (~75%), which likely contributes to the higher rates of stroke, end-stage renal disease and mortality seen in this population.4,5

Microbiota-related research has been a rapidly developing area of interest within the field of hypertension and has been gaining recognition as an important mechanism linking diet to host health and disease. Emerging human and pre-clinical data provide evidence for strong links between the gut microbiota and the development of hypertension, where both hypertensive humans and animal models exhibit gut dysbiosis and decreases in microbial diversity compared to normotensive controls.6,7 Collectively, these studies strongly support the role of the gut microbiota in hypertension.

The Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rat is a well-established animal model of salt-induced high blood pressure and kidney disease which recapitulates many of the hallmarks typically observed in humans with salt-sensitive hypertension, including albuminuria, severe glomerulosclerosis, insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia.8 Dahl SS rats bred at the Medical College of Wisconsin (SS/MCW) are maintained on a highly purified, 0.4% NaCl casein-based diet (AIN-76A, Dyets Inc).9 Dahl SS rats from Charles River Laboratories (SS/CRL), whose colony originated from SS/MCW breeders in 2001, are instead maintained on a 0.75% NaCl grain-based diet (5L79, LabDiet) and found to be remarkably protected from salt-induced hypertension and renal damage compared to SS/MCW rats fed the purified diet.10,11 Over a decade's worth of research has demonstrated that the differences in the severity of salt-sensitive hypertension between the colonies is mediated by dietary components other than salt.12-15 More specifically, this effect of the purified vs grain diet has been attributed to the difference in dietary protein source (casein vs wheat gluten),12 where there is a clear contribution of the adaptive immune system.13-15 Our recent efforts to understand the influence of the non-sodium components of the diet on salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage have demonstrated that these changes are related to substantial differences in DNA methylation16 and gene expression11 in T-lymphocytes which alter the inflammatory phenotype and ultimately disease severity. As a result of the significant immune-mediated dietary effects observed in the Dahl SS rat and the increasing evidence for the role of the gut microbiota in hypertension and immunity, we hypothesized that the gut microbiota compositions of SS/MCW and SS/CRL are driven by these dietary alterations. More specifically, we sought to explore these diet-induced changes to the gut microbiota as cause for the significant phenotypic divergence between SS/MCW and SS/CRL. To test this hypothesis, the current study characterized the SS gut microbiota in the presence of dietary alterations and performed faecal microbiota transfer experiments to examine the direct contribution of the gut microbiota to the development of hypertension and renal disease.

2 ∣. RESULTS

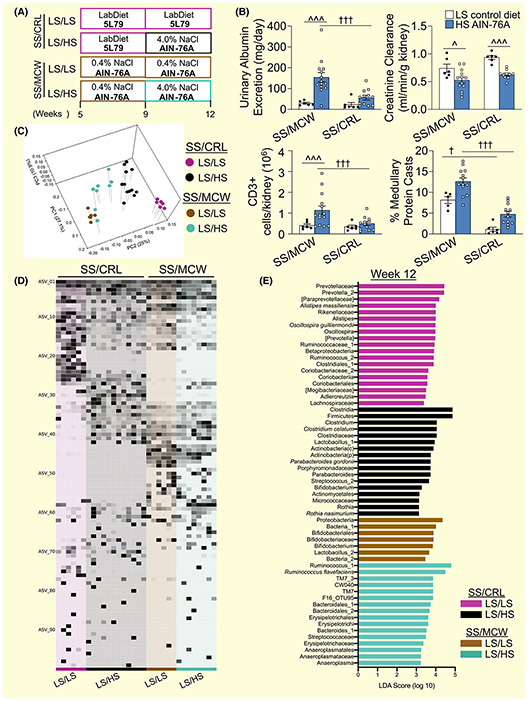

2.1 ∣. 5L79-fed SS/CRL rats are significantly protected from the development of salt-induced renal damage and immune cell infiltration compared to AIN-76A-fed SS/MCW

Figure 1A illustrates the protocol for the phenotyping experiments of the SS/MCW and SS/CRL male rats. Shown in Figure 1B, SS/CRL rats weigh significantly less than the SS/MCW throughout the experiment (332.9 ± 4.6 vs 355.5 ± 6.7 g, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW at Week 12, P < .001). After 3 weeks of HS, SS/CRL kidneys weigh less than the SS/MCW (4.65 ± 0.14 vs 5.85 ± 0.27 g/kg kidney/body weight, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW, P = .0011), indicating a protection from salt-induced renal hypertrophy, with no differences in creatinine clearance. At Week 8, no differences in urinary renal damage indices were observed between SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats. At Week 12, SS/CRL have an elevation in urinary sodium excretion (44.3 ± 1.5 vs 31.2 ± 2.9 mEq/day/kg BW, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW at Week 12, P = .011) which is accompanied by significantly lower proteinuria (109.5 ± 13.7 vs 293.0 ± 27.2 mg/d, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW, P < .001) and albuminuria (56.3 ± 10.9 vs 154.2 ± 22.5 mg/d, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW, P < .001) compared to SS/MCW rats after HS challenge (Figure 1C). SS/CRL also exhibited fewer renal infiltrating immune cells after 3 weeks of HS compared to SS/ MCW. Shown in Figure 1D, there were fewer CD45+ total leukocytes (59.1% less in SS/CRL vs SS/MCW), CD11b/c+ monocytes and macrophages (59.0%), CD3+ T-cells (56.2%), CD3+CD4+ T helper cells (57.3%), CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (54.2%), and CD45R+ B-cells (70.4%). This coincided with qualitatively fewer protein casts formed in the renal medulla, improved glomerular morphology, and a significant reduction in the urinary presence of renal epithelial injury marker KIM-1 (31.2 ± 3.3 vs 146.2 ± 30.8 ng/d, SS/CRL vs SS/MCW, P < .001) in the SS/CRL compared to SS/MCW (Figure 1E,F). These data altogether demonstrate the substantial protection of the 5L79-fed SS/CRL rats to salt-induced renal injury and inflammation when compared to the disease-prone SS/MCW.

FIGURE 1.

SS/CRL rats fed the 5L79 diet demonstrate attenuated HS-induced renal damage and immune cell infiltration compared to SS/MCW rats fed the 0.4% NaCl AIN-76A diet. A, Visual schematic of experimental protocol. B, Body weight measured at 5, 8 and 12 wk of age, with left kidney weight and creatinine clearance measured at the end of the experiment. Urinary sodium excretion, proteinuria and albuminuria (C), renal infiltrating immune cells (D), histopathology of medullary protein cast formation and glomerular damage (E), and urinary renal epithelial injury marker KIM-1 (F) between SS/MCW and SS/CRL before (Week 8) or after (Week 12) three weeks of HS challenge. CD45+: leukocytes, CD11b/c+: monocyte/macrophages, CD3+: T-cells, CD4+: helper T-cells, CD8+: cytotoxic T-cells, CD45R+: B-cells. n = 12-14. †P < .05, ††P < .01, †††P < .001 vs SS/MCW HS with Student's t test, Two Way ANOVA or Two Way RM ANOVA

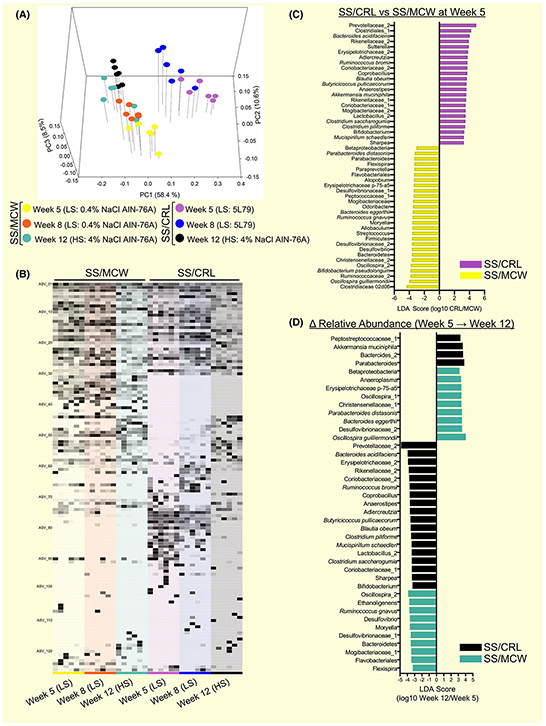

2.2 ∣. Differential high salt-induced effects on renal damage and gut microbiota composition in SS/MCW and SS/CRL

Figure 2A depicts the SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats maintained on their respective control, low salt diet (LS; SS/MCW = 0.4% NaCl AIN-76A, SS/CRL = 5L79) or challenged with 3 weeks of HS. High salt challenge resulted in increased urinary albumin, renal infiltration of CD3+ T lymphocytes and greater medullary protein cast formation compared to age-matched, low salt AIN-76A diet-fed SS/MCW rats (Figure 2B). This was significantly attenuated in SS/CRL rats, where HS challenge caused only modest increases in these parameters compared to age-matched, 5L79 diet-fed SS/CRL rats. However, HS challenge caused a significant decrease in creatinine clearance in both SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats. Shown in the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot in Figure 2C, SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats have significantly different gut microbiotas while on 0.4% NaCl AIN-76A and 5L79, respectively, as well as after 3 weeks of the same HS challenge. Interestingly, within each group, HS treatment also resulted in significant shifts in gut microbiota composition. To highlight more specific differences, Figure 2D demonstrates the relative abundance of identified amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) at Week 12 across these 4 groups. A full list of these defined ASVs can be found in the Supplemental Excel File. Additionally, linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was used to calculate a linear discriminate analysis (LDA) score to indicate ASVs that significantly characterize CRL LS/LS (purple), CRL LS/HS (black), MCW LS/LS (brown), MCW LS/HS (teal) at Week 12 (Figure 2E). These data importantly show the effect of the 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A (HS) diet on both the renal injury phenotype as well as on the gut microbiota composition in SS/ MCW and SS/CRL rats.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of salt on renal damage phenotype and gut microbiota of SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats. A, Experimental protocol of SS/CRL and SS/MCW rats maintained on either low salt 5L79 or AIN-76A diet, respectively, or challenged with 4.0% NaCl HS AIN-76A diet. B, Urinary albumin excretion, creatinine clearance, CD3+ renal T lymphocytes and medullary protein casts formation in SS/CRL and SS/MCW rats, respectively, maintained on either low salt 5L79 or AIN-76A, or on HS for 3 wk (Week 12). n = 12. †P < .05, †††P < .001 vs SS/MCW, ^P < .05, ^^^P < .001 vs LS, with Two Way ANOVA. C, Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the weighted UniFrac distance matrix showing SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats have significantly distinct gut microbiotas driven by salt treatment. (CRL LS/LS vs CRL LS/HS (P = .001), CRL LS/LS vs MCW LS/LS (P = .005), CRL LS/LS vs MCW LS/HS (P = .001), CRL LS/HS vs MCW LS/LS (P = .001), CRL LS/HS vs MCW LS/HS (P = .001) and MCW LS/LS vs MCW LS/HS (P = .004), PERMANOVA analysis at P < .05). D, Relative abundance of identified ASVs at Week 12 in SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats respectively maintained on either 0.4% NaCl AIN-76A or 5L79 (LS/LS) or challenged with 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A (LS/HS). E, Positive linear discriminate analysis (LDA) scores indicate ASVs that significantly changed and characterize each of the treatment groups at Week 12. Purple (CRL LS/LS), black (CRL LS/HS), brown (MCW LS/LS), teal (MCW LS/HS). Significance obtained by LDA effect size at P < .05 (Kruskal-Wallis test) and Z-scores > 2.0

2.3 ∣. SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats have distinctly different gut microbiotas throughout the entire course of the experiment

Weighted Unifrac PCoA (Figure 3A) revealed that SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats have significantly distinct gut microbiotas from each other at all timepoints examined (SS/MCW vs SS/CRL at Week 5 (P = .004), Week 8 (P = .005), and Week 12 (P = .005)), which was also significantly altered by HS diet (Week 8 vs Week 12 in SS/MCW (P = .004) and SS/CRL (P = .004)). Demonstrating global differences, Figure 3B displays the relative abundance of identified ASVs from 16S rRNA gene sequencing in SS/MCW rats and SS/CRL rats at Weeks 5, 8 and 12. A full list of these defined ASVs can be found in the Supplemental Excel File. LEfSe analysis determined LDA scores at Week 5 (Figure 3C), where positive LDA scores indicate ASVs that characterize SS/CRL (purple) and negative LDA scores indicate ASVs that characterize SS/MCW (yellow). LEfSe was also used to identify discriminant ASVs that underwent significant relative abundance changes from Week 5 to Week 12 (Δ Relative Abundance, Figure 3D). Positive LDA scores indicate enrichment and negative LDA scores indicate depletion of ASVs in either SS/CRL (black) or SS/MCW (teal). Additionally, alpha diversity analysis revealed higher microbial diversity in SS/MCW rats compared to SS/CRL, which was significantly altered by salt and age (Figure S1). Together, these data indicate that SS/MCW and SS/CRL have distinctly specific gut microbial community compositions that are driven by diet.

FIGURE 3.

Faecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing demonstrates SS/MCW and SS/CRL have distinctly different gut microbiotas. A, Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the weighted UniFrac distance matrix showing SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats have significantly distinct gut microbiotas (SS/MCW vs SS/CRL at Week 5 (P = .004), Week 8 (P = .005), and Week 12 (P = .005)), which also significantly shifts because of salt and age (Week 8 vs Week 12 in SS/MCW (P = .004) and SS/CRL (P = .004), PERMANOVA analysis at P < .05). B, Relative abundance of identified ASVs in SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats at Weeks 5, 8, and 12. C, Positive linear discriminate analysis (LDA) scores indicate ASVs that significantly changed in SS/CRL (purple) and negative LDA scores indicate ASVs that significantly changed in SS/MCW (yellow). D, Identification of discriminant ASVs that underwent significant relative abundance changes from Week 5 to 12 in SS/CRL (black) and SS/MCW (teal). n = 6. Significance obtained by LDA effect size at P < .05 (Kruskal-Wallis test) and Z-scores > 2.0

It should be noted that these same renal injury, renal inflammation and gut microbiota composition parameters were also assessed in SS/MCW rats fed a nutritionally matched diet containing a protein substitution of wheat gluten for casein (SS/MCW gluten, Figures S2 and S3) as well as in female rats (Figures 4 and 5).

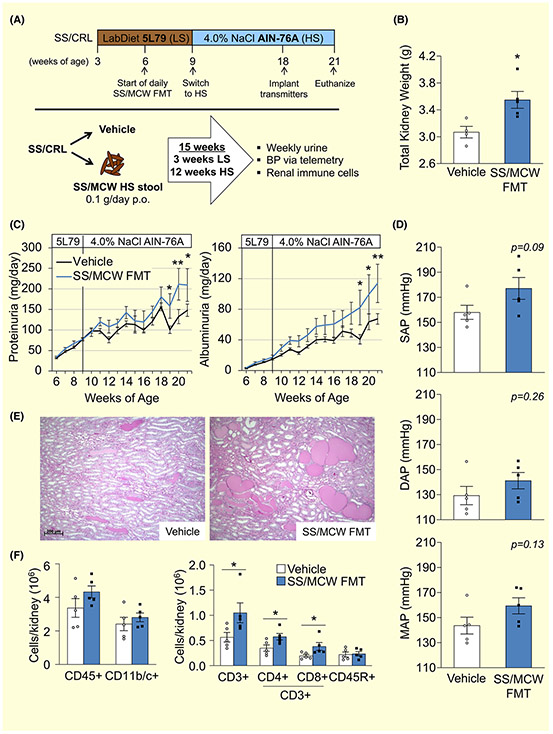

FIGURE 4.

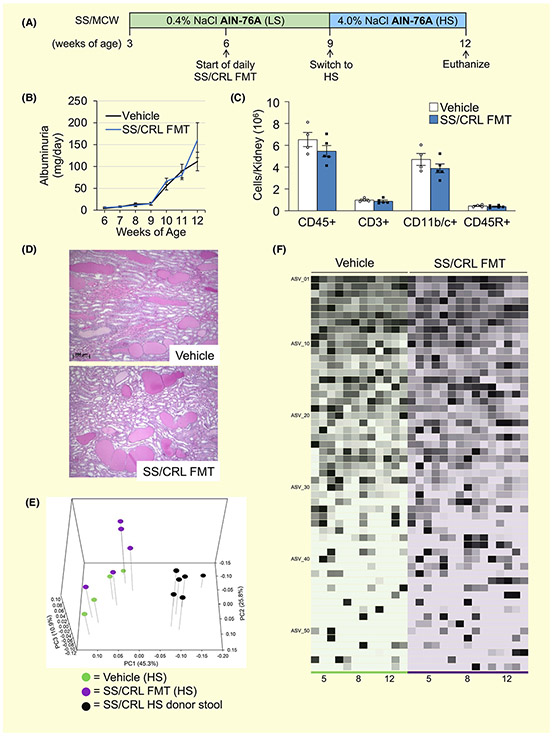

Faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) experiment reveals SS/MCW gut microbiota-driven elevations in renal damage, blood pressure and renal inflammation in protected SS/CRL recipients fed HS. A, Detailed schematic of FMT experimental protocol. B, Total kidney weight increased in the SS/MCW FMT group at the end of the 21-week experiment. Exacerbation of salt-induced renal damage indices, proteinuria and albuminuria (C), systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure (D), renal medullary protein cast formation (E) and renal immune cell infiltration (F) in SS/MCW FMT versus Vehicle-treated rats. CD45+: leukocytes, CD11b/c+: monocyte/macrophages, CD3+: T-cells, CD4+: helper T-cells, CD8+: cytotoxic T-cells, CD45R+: B-cells. n = 5-6. *P < .05, **P < .01 vs Vehicle with Student's t test, Two Way ANOVA or Two Way RM ANOVA

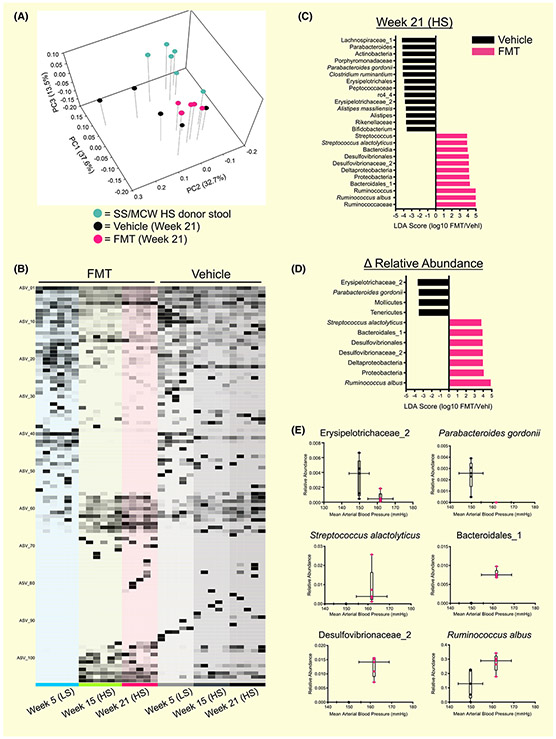

FIGURE 5.

FMT from SS/MCW donor rats into SS/CRL recipients fed AIN-76A induced significant shifts in gut microbial composition that correlate with blood pressure. A, PCoA plot of the weighted UniFrac distance matrix demonstrating that FMT from SS/MCW donors significantly shifted the gut microbial community of SS/CRL recipients (PERMANOVA (all) P = .001; Pairwise PERMANOVA: Donor vs FMT P = .006, Donor vs Vehicle P = .004, Vehicle vs FMT P = .029). B, Global differences in relative abundance of identified ASVs in FMT and vehicle-treated rats at Weeks at Weeks 5, 15 and 21. C, Positive linear discriminate analysis (LDA) scores indicate ASVs that significantly changed in FMT rats (pink) and negative LDA scores indicate ASVs that significantly changed in vehicle (black). D, Identification of discriminant ASVs that underwent significant relative abundance changes from Week 5 to 21. Significance obtained in (C) and (D) by LDA effect size at P < .05 (Kruskal-Wallis test) and Z-scores > 2.0. (E) Significant ASVs found in 5D between FMT and vehicle rats that shift with MAP. n = 5-6

2.4 ∣. Faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) of SS/MCW gut microbiota into protected SS/ CRL recipient rats raises blood pressure, increases renal damage and increases renal T cell infiltration while on the 4.0% NaCl (HS) AIN-76A diet

To determine the contribution of the gut microbiota to the development of hypertension and renal disease, we performed an FMT experiment by taking the SS/MCW gut microbiota (or Vehicle) and transplanting it into protected SS/CRL rats while fed the HS diet. Figure 4A represents the schematic for the FMT protocol. Significant renal hypertrophy was observed in the SS/MCW FMT group compared to vehicle (Figure 4B, 3.6 ± 0.1 vs 3.1 ± 0.1 g, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .02), with no difference in body weight throughout the entire duration of the FMT study (data not shown). Shown in Figure 4C, the SS/CRL rats receiving SS/MCW FMT also exhibited significantly greater renal damage than the vehicle group in response to the HS diet, evident by significant increases in proteinuria (209.4 ± 39.8 vs 148.0 ± 15.0 mg/d, FMT vs Vehicle at Week 21, P = .024) and albuminuria (113.7 ± 25.0 vs 67.4 ± 6.9 mg/d, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .007). A slight increase in systolic arterial pressure (SAP) with a notable trend towards significance was observed in the SS/CRL receiving SS/MCW FMT while fed the HS diet (Figure 4D, 177.1 ± 8.7 vs 158.0 ± 5.6 mmHg, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .09). The same trend was true for mean arterial pressure (159.4 ± 6.4 vs 143.6 ± 6.7 mmHg, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .13) but to a lesser extent for diastolic arterial pressure (141.2 ± 6.5 vs 129.3 ± 7.3 mmHg, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .26). While the SS/CRL Vehicle rats could certainly be described as hypertensive, it is important to note that the disease resistant nature of the SS/CRL is what has allowed these rats to survive a 12 week-long high salt challenge. Additionally, there were no significant changes in heart rate between the two groups (375.0 ± 3.4 vs 362.4 ± 10.1 bpm, FMT vs Vehicle, P = .31, data not shown). Hourly telemetry data can be found plotted in Figure S6. At the end of the experiment, there was also an observed increase in medullary protein cast formation in the FMT group (Figure 4E). Interestingly, examination of the infiltrating immune cells into the kidneys revealed a significant and specific increase in CD3+ T cells (1.9-fold increase, FMT vs Vehicle), CD3+CD4+ T helper cells (1.7-fold), CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (2.0-fold) (Figure 4F), but no difference in CD11b/c+ monocytes/macrophages or CD45R+ B cells in the SS/MCW FMT group fed HS. There were no differences observed in either urinary sodium or potassium excretion (Na+: 12.0 ± 1.0 vs 14.2 ± 1.1 mEq/d, P = .17; K+: 1.8 ± 0.2 vs 2.0 ± 0.1 mEq/d, P = .31, FMT vs Vehicle at Week 21, data not shown), creatinine clearance (0.60 ± 0.06 vs 0.63 ± 0.05 mL/min/g kidney, FMT vs Vehicle at Week 21, P = .77, data not shown), or urinary KIM-1 or nephrin excretion (data not shown) between FMT and Vehicle-treated rats. It should also be mentioned that the amount of sodium and potassium present in the donor stool is negligible compared to that normally consumed by the rats via their chow (79.0 ± 25.3 μg Na+ and 27.5 ± 8.2 μg K+ in 0.1 g SS/MCW donor HS stool). Because the FMT is the only variable that differed between groups, there is strong evidence indicating a cause-effect relationship (Koch's 3rd postulate) and that the exacerbation of HS-induced hypertension and renal damage in the FMT group is because of the transferred gut microbiota. While it is likely that the transferred SS/MCW gut microbiota thrived because of the concomitant switch to the HS AIN-76A diet, these data provide the first evidence that the gut microbiota of SS/MCW rats fed the AIN-76A diet contains bacteria and associated factors that initiate a cascade of events ultimately driving and exacerbating hypertension, renal damage, and inflammation.

2.5 ∣. FMT from hypertensive SS/MCW donor stool into SS/CRL recipient rats induced shifts in gut microbial composition while on the 4.0% NaCl HS AIN-76A diet

Shown in the PCoA plot in Figure 5A, FMT of SS/MCW HS donor stool induced significant shifts in the gut microbial community of SS/CRL recipients compared to those only receiving vehicle (FMT vs Vehicle at Week 21, P = .029). It is important to note that a significant difference remained between donor stool and FMT recipients (P = .006), reflecting an intermediate composition, which perhaps explains the lack of a robust effect in the blood pressure phenotype. There was also a significant alteration because of salt and age (Week 5 LS vs Week 21 HS in Vehicle-treated rats, P = .01, data not shown). Figure 5B highlights the global differences in relative abundance of identified ASVs in FMT and vehicle-treated rats at Weeks 5, 15 and 21. A complete list of these defined ASVs can be found in the Supplemental Excel File. LEfSe analysis was used to determine discriminant ASVs at Week 21 between FMT and vehicle recipient rats (Figure 5C), where the set of ASVs that characterize vehicle rats (black) are represented by negative LDA scores and FMT rats (pink) by positive LDA scores. Discriminant ASVs that underwent significant relative abundance change from Week 5 to Week 21 (Δ Relative Abundance, Figure 5D) were also identified between FMT recipient rats and Vehicle rats. With ASV relative abundance plotted against MAP, LEfSe analysis identified the following statistically significant ASVs that shift with FMT: Erysipelotrichaceae_2, Parabacteroides gordonii, Streptococcus alactolyticus, Bacteroidales_1, Desulfovibrionaceae_2, Ruminococcus albus (Figure 5E). Because the transfer of the gut microbiota was the only variable that differed between the two groups, we were able to demonstrate a cause-effect relationship between alterations in the gut microbiota (ASVs) and the subsequent change in all measured endpoints (blood pressure, renal damage, renal inflammation).

To test whether the SS/CRL gut microbiota could attenuate the HS-induced hypertensive phenotype, an alternative experiment of transferring SS/CRL gut microbiota into disease-prone SS/MCW rats was performed while maintaining the recipients on the AIN-76A diets. As shown in Figure 6, FMT of the protected SS/CRL gut microbiota did not offer SS/MCW rats protection from the development of salt-induced renal damage (Figure 6B-D) while fed HS diet. This was likely because of the inability of the SS/CRL FMT to significantly shift the gut microbiota composition (Figure 6E,F), which might be attributed to the SS/CRL microbiota being unable to flourish with the AIN-76A diet. In theory, placing the SS/CRL FMT on the 5L79 diet may have allowed the microbiota to flourish, but because of the lack of hypertension and renal damage with the 5L79 diet itself, experimentally this approach would give us a very narrow phenotypic window to observe additional protective effects of the SS/CRL FMT. It should further be noted that the alternative experiment was not carried out for 21 weeks because of the severity of disease in the SS/MCW recipients who would not survive a 12 week HS challenge.

FIGURE 6.

No effect of SS/CRL faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) into SS/MCW recipient rats fed AIN-76A. A, Timeline of SS/CRL FMT into SS/MCW rats. Daily FMT of SS/CRL donor stool into SS/MCW recipient rats for 6 wk resulted in no significant change in (B) albuminuria, (C) renal immune cell infiltration or (D) renal medullary protein cast formation (Two Way ANOVA or Two Way RM ANOVA). E, Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the weighted UniFrac distance matrix showing that FMT from SS/CRL donors was unable to significantly shift the gut microbial community of SS/MCW recipients (Pairwise PERMANOVA: FMT vs Vehicle at Week 12, P = .096). F, Relative abundance of identified ASVs at Weeks 5, 8, and 12 demonstrate similar community composition in Vehicle and FMT rats. CD45+: leukocytes, CD3+: T-cells, CD11b/c+: monocyte/macrophages, CD45R+: B-cells. n = 4-5

3 ∣. DISCUSSION

The present study has demonstrated that a whole-grain diet not only attenuates salt-sensitive hypertension, renal damage, and inflammation when compared to a purified casein diet, but also induces significant shifts in the gut microbiota composition of the SS/MCW rat. While the AIN-76A diet likely dictates which organisms thrive from the transplanted SS/MCW microbiota and what factors they can synthesize from the substrates available in the food provided, faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) experiments have determined that a causative, pathogenic factor(s) of microbial origin drives hypertension and renal disease in SS/MCW rats specifically fed the AIN-76A diet. Our work highlights the potential power of gut microbiota modulation through nutritional intervention and dietary management in the regulation of blood pressure and kidney disease.

There is supportive evidence from other animal models of hypertension also demonstrating pathogenic factors derived directly from the hypertensive gut microbiota. Normotensive WKY rats were shown to develop hypertension after a single transfer of cecal contents from spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats.17 Similarly, a single transplantation of faeces from hypertensive humans results in elevated blood pressure in germ-free mice.18 The first study to use SS rats, demonstrated that a single transfer of salt-sensitive cecal contents into Dahl salt-resistant rats did not affect blood pressure, but the reverse transfer (Dahl salt-resistant cecal contents into Dahl salt-sensitive rats) actually elevated blood pressure.7

The gut microbiota and the diet are intimately influenced by each other, where dietary habits not only shape gut microbiota composition, but bacteria also dictate metabolite production and drive the ultimate systemic effects of the diet. Substantial research efforts in our laboratory have focused on understanding the underlying mechanisms by which dietary protein modulates the severity of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Corroborating our findings that a plant-based whole grain diet protects from salt-induced high blood pressure and renal disease, there is extensive observational evidence stressing the benefit of plant protein consumption on cardiovascular disease.19,20 A number of studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between plant protein intake and blood pressure,21-24 and dietary interventional trials have highlighted the health benefit associated with greater plant protein consumption.25,26 Plant-based diets have been associated with a distinct herbivorous microbiota signature27 and linked to an improved Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, unique bacterial speciation, and more faecal short-chain fatty acids.28 While the diet clearly drives microbial composition, the gut microbiota itself plays a critical role in digestion, proteolysis29 and the proper fermentation of dietary proteins essential for amino acid balance, utilization, and bioavailability.30,31 Therefore, both gut microbiota composition and the diet play important and reciprocal roles critical for maintenance of host health.

High salt consumption has been shown to alter the composition of the gut microbiota,32 affect protein digestion in mice,33 and aggravate gut inflammation.34 By running low salt controls in our study, we were able to distinguish a change in phenotype and a significant shift in the gut microbiota because of the effect of salt alone (Figure 2). Additionally, our previous studies have found that wheat gluten is the primary protein source and dietary component responsible for the protection observed in the whole grain diet12,15; Dahl SS rats maintained on a modified version of the AIN-76A diet containing wheat gluten in place of casein resulted in changes to both the salt-sensitive phenotype as well as gut microbiota composition (Figures S2 and S3). These experiments provided a more controlled, nutritionally matched approach since these diets differ by only a single dietary substitution (the replacement of casein for wheat gluten). Interestingly, casein has been shown to increase microbial density and decrease microbial diversity, leading to worsened inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of DSS-induced colitis.35 This is in line with more recent evidence which suggests that inflammation and immune mechanisms link microbial dysbiosis to the progression of chronic disease. Wilck et al have attributed the salt-sensitive hypertensive effects in a model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis to a depletion in Lactobacillus murinus, which occurs in a T helper 17 (TH17) cell-dependent manner.32 Interestingly, we have only observed IL-17 effects in an angiotensin II-induced model in the Dahl SS rat,36 and instead have determined that mechanisms related to IL-6 signaling37 and NOX2-derived free radical production in immune cells38 appears to drive salt-sensitivity. The gut dysbiosis observed in both hypertensive human subjects and experimental mice has more recently been associated with increased intestinal inflammation and activation of antigen presenting cells.39 The effect of diet on the renin-angiotensin system, cytokines, free radical production, intestinal inflammation and the characterization of the specific immune cells residing in gut tissue of the Dahl SS rat all remain to be investigated, and is the focus of our immediate studies. Other closely related and potentially involved mechanisms include perturbations to short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and the renal sensory receptors responsible for their action,40,41 β-hydroxybuyrate42 and LPS,18,43,44 all of which remain to be explored between SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats. An additional influence that should be importantly considered is sex. The current study also examined female SS/MCW and SS/CRL rats, which revealed substantial protection from renal damage (Figure S4) and significant differences in gut microbiota composition when compared to males (Figure S5) after HS. This is in line with other literature highlighting sex as a major factor in the determination of the gut microbial profile.45,46 For future studies, we are interested in delving into the role sex hormones play in driving these significant differences in gut microbiota composition, including FMT studies performed between sexes.

Upon closer examination of the statistically significant ASVs that shifted with MAP in the experimental transfer of SS/MCW gut microbiota to the protected SS/CRL rats, we can gain insight on potential bacterial functions and gut microbiota-derived metabolites that may be responsible for the ultimate pathological effects. Erysipelotrichaceae_2, which decreased in the SS/MCW FMT group while on the HS diet, is a butyrate-producing class of bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum that has been shown to be reduced in inflammation-related gastrointestinal diseases like Irritable Bowel Syndrome.47 Butyrate is known for its role in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier and restoring levels of this SCFA has been shown to have beneficial effects in experimental models of hypertension.42,48 Parabacteroides gordonii, whose genus Parabacteroides has been shown to decrease in response to a high fat diet and is one of several gut bacteria with anti-inflammatory attributes,49 was also decreased in the SS/MCW FMT group. Streptococcus alactolyticus, Desulfovibrionaceae_2 and Ruminococcus albus were all found to positively shift with transfer of the SS/MCW gut microbiota. The Streptococcus genus has been documented in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR)17,50 and also found to be enriched in obese Zucker rats.51 Desulfovibrionaceae_2 are producers of bacterial hydrogen sulfide, which is known to degrade the mucus layer of the gut, exposing the epithelium to bacteria and toxins, thus promoting inflammation.52 Finally, Ruminococcus albus ferments glucose to acetate, ethanol, formate and CO2.53 Interestingly, formate has been utilized as a urinary marker of blood pressure and CVD risk,54 and can serve as a substrate for Desulfovibrio species.55

A major limitation of the current study is the complexity of the SS/CRL 5L79 whole grain diet, and thus was the impetus for the parallel studies performed in SS/MCW rats fed a nutritionally matched wheat gluten-based diet (Figures S2-S5), where the only difference between groups was the source of dietary protein. Furthermore, there are different sources of fibre between the two diets (insoluble fibre in AIN-76A, soluble fibres in 5L79) that likely contribute to varying circulating SCFA levels,56 which are known to protect against hypertension and end organ damage.57,58 The measurement of gut microbiota-metabolites produced by the fermentation of fibre, along with studies parsing out the contribution of these varying fibre sources are part of future, ongoing studies. The potential differences between SS/MCW and SS/CRL in their intestinal and renal sodium handling capabilities also remain to be explored, as this may provide important clues into how other components of the diet affect the susceptibility to salt-driven effects. Additionally, there are certainly limitations to our FMT strategy, including the potential for the gut microbiota to indirectly alter blood pressure, survival of anaerobes, the use of Nutella as another alteration to the diet and the potential impact of using low vs high salt stool from SS/MCW donors. However, it is important to note that our strategy did not utilize an antibiotic pre-treatment to ablate the gut microbiota of recipient rats. It is known that antibiotic treatment itself alters the gut microbiome community composition as well as the hypertensive phenotype.59,60 Additionally, there is evidence demonstrating successful FMT without the use of antibiotics.61 Therefore, prior to FMT, our approach does not alter the native gut microbiota of the SS rat nor alters the basal hypertensive phenotype, both of which are known to be affected by antibiotic treatment. Despite these limitations, we present evidence that gut microbiota manipulation can indeed alter high salt-induced hypertension, renal damage and renal inflammation. Furthermore, and perhaps just as important, the current study highlights changes in the gut microbiota composition and hypertensive phenotype between animals from different facilities and on different diets, which should be seriously considered in this age of data rigor and reproducibility.

In summary, 5L79-fed SS/CRL rats are protected from developing salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage compared to AIN-76A diet-fed SS/MCW rats. Examination of the gut microbiota of these two groups revealed the influence of the diet on gut bacterial composition. Through gut microbiota transfer experiments, we have provided strong evidence for a cause-effect relationship where the transfer of the SS/MCW gut microbiota into SS/CRL rats worsened their disease progression while on the 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A diet. Therefore, we have demonstrated that the gut microbiota of SS/MCW rats contains hypertensive and renal damage-causative bacteria and associated factors which, likely through indirect mechanisms, is at least in part responsible for driving salt-sensitivity in SS/MCW rats fed the AIN-76A diet. While much work remains in determining the intermediate metabolites that connect the diet to microbiota, epigenetics, and immunity, the current study highlights the power of dietary modifications and nutritional interventions in the management of salt-sensitive hypertension.

4 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its supplementary files. All DNA sequencing data generated from these studies have been made available in NCBI's Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA636903.

4.1 ∣. Animals, diets and stool collection

Experiments were performed at the Medical College of Wisconsin on age-matched, inbred, individually housed male and female Dahl SS rats obtained from two colonies maintained on different diets. The data from male SS rats are presented in the main figures (Figures 1-6, Figures S1-S3), while data from female SS rats are presented in Figures S4 and S5. Inbred SS/JrHsdMcwi rats (denoted SS/MCW) have been maintained as a closed colony at the Medical College of Wisconsin since 1991 and fed a 0.4% NaCl purified casein-based AIN-76A diet (#113755, Dyets Inc).62 Breeding pairs from this colony were sent to Charles River Laboratories (SS/JrHsdMcwiCrl) in 2001 (denoted SS/CRL) and maintained on a 0.75% NaCl grain diet (5L79, LabDiet). The compositions for the 5L79 and AIN-76A diets are provided in Figure S7. Further, it is important to note that while the SS/MCW and SS/CRL colonies have been separated for nearly 20 years, the two strains have been found to exhibit only minor genetic drift (0.00001%). However, embryo transfer experiments have demonstrated these detrimental effects observed in the SS/MCW to be entirely because of the differences in diet, specifically the maternal diet during gestation and lactation, and not because of their genetic difference.10 Experimental SS/CRL rats arrived at MCW as 3 week old weanlings. Both groups of experimental rats were maintained on their respective diets from weaning through 9 weeks of age, where all rats were then switched to the high salt, casein-based diet (HS, 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A, #113756, Dyets Inc) for 3 weeks. A fresh stool sample was collected directly from the anus of rats at Weeks 5 8, and 12, flash frozen, and stored in −80°C until DNA extraction. A schematic of this experimental protocol can be found in Figure 1A. A major strength of this study was the adherence to the major considerations (housing, sex, sampling, controls) stated in the Guidelines for Transparency on Gut Microbiome Studies in Essential and Experimental Hypertension.63 All protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). We have also provided a consort diagram depicting the number of animals included in this study and the reason for any exclusions (Figure S8). The numbers of animals proposed for each protocol were calculated a priori with a statistical power analysis (SigmaPlot 14.0) taking into account the type of statistical analysis to be performed (one- or two-way ANOVA), the variability of the assays to be performed, and the minimum changes we expected to observe.

4.2 ∣. Urinalysis

Overnight urine was collected once during the low salt period (LS, Week 8) and once at the completion of the experiment after 3 weeks of 4.0% NaCl AIN-76A (HS, Week 12). Overnight urine is collected for approximately 18 hours (3:00 pm-9:00 am) in metabolic cages. Urine electrolytes were measured by flame photometry (Model 410, Corning), urinary protein was measured with an autoanalyzer (ACE, Alfa Wasserman), and urinary albumin was quantified with a fluorescent assay that utilizes Albumin Blue 580 dye (Molecular Probes) and a fluorescent plate reader (FL600, Bio-Tek).

4.3 ∣. Kidney immune cell isolation and flow cytometry

As previously described, rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane for tissue harvest after three weeks of high salt intake.14,15 To isolate renal immune cells, the kidneys were flushed with heparinized dPBS, minced with a razor blade, and incubated in RPMI 1640 media containing l-glutamine, HEPES, collagenase type IV and DNase. Mononuclear cells were separated by Percoll density gradient centrifugation and counted on a haemocytometer. To isolate immune cells from the blood, PBMCs were separated by centrifugation on Histopaque-1083. Isolated mononuclear cells were incubated with extracellular markers anti-CD45 (BioLegend, #202214, Clone OX-1) for leukocytes, anti-CD3 (eBioscience, #46-0030-82, Clone G4.18), CD4 (BioLegend, #201518, Clone W3/25), and CD8 (BioLegend, #201703, Clone OX-8) for T-cells, anti-CD45R (BD Bioscience, #554881, Clone HIS24) for B-cells and anti-CD11b/c (eBioscience, #50-0110-82, Clone OX-42) for monocytes/macrophages. All cells were analysed by flow cytometry (LSRII, Becton Dickinson) with FACSDIVA (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

4.4 ∣. Histology

Kidney tissues were collected for histological analysis and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, cut into 4 μm sections, mounted, and stained with Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Images of medullary casts were taken at 5x magnification and glomeruli were taken at 40x using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope.

4.5 ∣. 16S rRNA sequencing and analysis

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from stool using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen). DNA quality was checked via a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and QuBit (dsDNA HS Assay Kit). 16S rDNA gene sequence libraries were generated using the V3-V4 primer region, prepped using the Ilumina TruSeq DNA library prep system and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform at 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center. 16S rDNA sequencing data was analysed using Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2).64 Sequences were denoized, filtered and trimmed using the DADA2 plugin with a PHRED cut-off of 25.65 Taxonomy was assigned to amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using the GreenGenes66 (v 13_8, 97%) and SILVA67 reference databases. The relative abundance of the identified amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were visualized in Anvi'o.68 Phylogenetic trees were generated by aligning all ASVs via MAFFT69 and constructed with fast-tree2.70 Alpha-diversity metrics, beta-diversity metrics and Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) were estimated using the q2-diversity plugin after samples were rarefied (20 165 for Figure 2; 16 326 for Figure 3; 21 257 for Figure 5; 16 334 for Figure 6; 16 518 for Figure S3 and 1421 for Figure S5). PCoA was visualized in SigmaPlot. The Gneiss plugin in QIIME2 was used to examine differential abundances of ASVs between groups. ASVs were clustered via Ward hierarchical clustering to define the ASVs that commonly co-occur with each other. Results were visualized as dendrogram heatmaps. Linear discriminate analysis effect size (LEFSE)71 was used to determine discriminant ASVs. Discriminant ASVs were plotted in Prism Graphpad v7.

4.6 ∣. Faecal microbiota transfer (FMT) protocol

Starting at 5 weeks of age, SS/CRL rats receiving FMT were trained for one week to consume 1g Nutella/day (vehicle). With this trained oral administration, rats consumed the stool/Nutella mixture immediately upon presentation. This approach was chosen over an oral gavage technique to avoid animal restraint which would interfere with the telemetry unit placed at the nape of the neck. Daily FMT began at 6 weeks of age, where 0.1g of donor SS/MCW HS stool was freshly ground via mortar and pestle, mixed with 1g Nutella, and administered orally to SS/CRL rats. Donor stool was collected via metabolic cages from SS/MCW rats exposed to the HS diet for 3 weeks. Control rats received Nutella vehicle only. At 9 weeks of age, all rats were placed on the HS diet. FMT was administered daily for a total of 15 weeks, together with HS challenge for the last 12 weeks. This prolonged length of high salt exposure was necessary because of the disease-resistant nature of the SS/CRL on the 5L79 diet. Urine was collected overnight via metabolic cages on a weekly basis to track renal damage. At 18 weeks, rats were implanted with telemetry transmitters for the measurement of blood pressure. At 21 weeks, tissues were harvested, and renal immune cells were isolated and assessed via flow cytometry as previously described. A schematic of this experimental protocol can be found in Figure 4A. An alternative FMT was also performed, with SS/MCW rats receiving daily FMT of SS/CRL stool while maintained on the AIN-76A diet for a total of 6 weeks (experimental protocol found in Figure 6A).

4.7 ∣. Blood pressure measurement in FMT animals

At 18 weeks of age, rats were deeply anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane. Using aseptic technique, rats were instrumented with telemetry transmitters (Data Sciences International) into the carotid artery with the body of the transmitter implanted subcutaneously in the back of the animal. Animals were maintained on heating pads during and following the procedure, with analgesia (0.3mg/kg Buprenorphine-SR) administered after surgery. The telemetry data reported in the manuscript (mean, systolic and diastolic arterial blood pressure and heart rate) reflect measurements made a week after surgery, allowing ample time for the full surgical recovery of the rats and the collection of reliable data (Figure S6). Unless specified differently, all telemetry data represents an average of all data continuously collected over 24 hours/d, with the system set to measure for 10 seconds every two minutes, excluding the days where rats were in metabolic cages for urine collection.

4.8 ∣. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± one standard error of the mean. Physiological data were assessed for significance using a t test, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Holm-Sidak post-hoc test, or a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Holm-Sidak post-hoc test, as appropriate, using SigmaPlot Version 14.0. For sequencing data, alpha- and beta-diversity metrics were calculated using the q2-diversity plugin in QIIME2. Alpha (within sample)-diversity metrics used Kruskal-Wallis (P values <.05) followed by Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction to examine community richness and abundance. Alpha diversity measured using Shannon's Diversity was plotted in PrismGraphpad v7. Beta (across sample)-diversity metrics used Pairwise PERMANOVA (P values <.05) followed by Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction to determine if the microbial communities were statistically significantly different. For visualization of β-diversity, we used weighted UniFrac distances72 plotted as a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). To determine significantly enriched bacteria per group, we use LEFSE analysis (Z-scores > 2.0 and P < .05), balances analysis with the GNEISS plugin in QIIME2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Stephanie Kellogg for her assistance in writing sections of the paper related to the microbiome, and Mary Cherian-Shaw, Michael Brands, and Weston Bush for their technical assistance. This work was supported by HL116264, HL137748, AHA-19CDA34660184, F31HL152495, and the Georgia Research Alliance.

Funding information

American Heart Association, Grant/Award Number: 19CDA34660184; Georgia Research Alliance; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: F31HL152495, HL116264 and HL137748

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberger MH. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1996;27(3 Pt 2):481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lackland DT, Egan BM. Dietary salt restriction and blood pressure in clinical trials. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9(4):314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svetkey LP, McKeown SP, Wilson AF. Heritability of salt sensitivity in black Americans. Hypertension. 1996;28(5):854–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberger MH, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Grim CE, Fineberg NS. Definitions and characteristics of sodium sensitivity and blood pressure resistance. Hypertension. 1986;8(6_pt_2):127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65(6):1331–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mell B, Jala VR, Mathew AV, et al. Evidence for a link between gut microbiota and hypertension in the Dahl rat. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47(6):187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigazzi R, Bianchi S, Baldari D, Sgherri G, Baldari G, Campese VM. Microalbuminuria in salt-sensitive patients. A marker for renal and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension. 1994;23(2):195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattson DL, Kunert MP, Kaldunski ML, et al. Influence of diet and genetics on hypertension and renal disease in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Physiol Genomics. 2004;16(2):194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geurts AM, Mattson DL, Liu P, et al. Maternal diet during gestation and lactation modifies the severity of salt-induced hypertension and renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abais-Battad JM, Alsheikh AJ, Pan X, et al. Dietary effects on dahl salt-sensitive hypertension, renal damage, and the T lymphocyte transcriptome. Hypertension. 2019;74(4):854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattson DL, Meister CJ, Marcelle ML. Dietary protein source determines the degree of hypertension and renal disease in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension. 2005;45(4):736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Miguel C, Lund H, Mattson DL. High dietary protein exacerbates hypertension and renal damage in Dahl SS rats by increasing infiltrating immune cells in the kidney. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abais-Battad JM, Lund H, Fehrenbach DJ, Dasinger JH, Mattson DL. Rag1-null Dahl SS rats reveal that adaptive immune mechanisms exacerbate high protein-induced hypertension and renal injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018;315(1):R28–R35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abais-Battad JM, Lund H, Fehrenbach DJ, Dasinger JH, Alsheikh AJ, Mattson DL. Parental dietary protein source and the role of CMKLR1 in determining the severity of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):440–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasinger JH, Alsheikh AJ, Abais-Battad JM, et al. Epigenetic Modifications in T Cells: the role of DNA methylation in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;75(2):372–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adnan S, Nelson JW, Ajami NJ, et al. Alterations in the gut microbiota can elicit hypertension in rats. Physiol Genomics. 2017;49(2):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter CK, Skulas-Ray AC, Champagne CM, Kris-Etherton PM. Plant protein and animal proteins: do they differentially affect cardiovascular disease risk? Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):712–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacks FM, Rosner B, Kass EH. Blood pressure in vegetarians. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;100(5):390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YF, Yancy WS Jr, Yu D, Champagne C, Appel LJ, Lin PH. The relationship between dietary protein intake and blood pressure: results from the PREMIER study. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22(11):745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamler J, Liu K, Ruth KJ, Pryer J, Greenland P. Eight-year blood pressure change in middle-aged men: relationship to multiple nutrients. Hypertension. 2002;39(5):1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott P, Stamler J, Dyer AR, et al. Association between protein intake and blood pressure: the INTERMAP Study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altorf-van der Kuil W, Engberink MF, Brink EJ, et al. Dietary protein and blood pressure: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appel LJ, Sacks FM, Carey VJ, et al. Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;294(19):2455–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(33):14691–14696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH, Allison C. Protein degradation by human intestinal bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132(6):1647–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai ZL, Zhang J, Wu G, Zhu WY. Utilization of amino acids by bacteria from the pig small intestine. Amino Acids. 2010;39(5):1201–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davila AM, Blachier F, Gotteland M, et al. Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host. Pharmacol Res. 2013;68(1):95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature. 2017;551(7682):585–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Huang Z, Yu K, et al. High-salt diet has a certain impact on protein digestion and gut microbiota: a sequencing and proteome combined study. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi B, Titze J, Rykova M, et al. Effects of dietary salt levels on monocytic cells and immune responses in healthy human subjects: a longitudinal study. Transl Res. 2015;166(1):103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim E, Kim DB, Park JY. Changes of mouse gut microbiota diversity and composition by modulating dietary protein and carbohydrate contents: a pilot study. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2016;21(1):57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wade B, Petrova G, Mattson DL. Role of immune factors in angiotensin II-induced hypertension and renal damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018;314(3):R323–R333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashmat S, Rudemiller N, Lund H, Abais-Battad JM, Van Why S, Mattson DL. Interleukin-6 inhibition attenuates hypertension and associated renal damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(3):F555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abais-Battad JM, Lund H, Dasinger JH, Fehrenbach DJ, Cowley AW Jr, Mattson DL. NOX2-derived reactive oxygen species in immune cells exacerbates salt-sensitive hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;146:333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferguson JF, Aden LA, Barbaro NR, et al. High dietary salt-induced dendritic cell activation underlies microbial dysbiosis-associated hypertension. JCI Insight. 2019;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganesh BP, Nelson JW, Eskew JR, et al. Prebiotics, probiotics, and acetate supplementation prevent hypertension in a model of obstructive sleep apnea. Hypertension. 2018;72(5):1141–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pluznick J A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(2):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakraborty S, Galla S, Cheng X, et al. Salt-responsive metabolite, beta-hydroxybutyrate, attenuates hypertension. Cell Rep. 2018;25(3):677–689.e674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss J Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP): structure, function and regulation in host defence against Gram-negative bacteria. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(Pt 4):785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42(2):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Org E, Mehrabian M, Parks BW, et al. Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(4):313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolnick DI, Snowberg LK, Hirsch PE, et al. Individual diet has sex-dependent effects on vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pozuelo M, Panda S, Santiago A, et al. Reduction of butyrate- and methane-producing microorganisms in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Zhu Q, Lu A, et al. Sodium butyrate suppresses angiotensin II-induced hypertension by inhibition of renal (pro)renin receptor and intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2017;35(9):1899–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan TJ, Ahmed YM, Zamzami MA, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on the gut microbiota of high fat diet-induced hypercholesterolemic rats. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santisteban MM, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, et al. Hypertension-linked pathophysiological alterations in the gut. Circ Res. 2017;120(2):312–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petriz BA, Castro AP, Almeida JA, et al. Exercise induction of gut microbiota modifications in obese, non-obese and hypertensive rats. BMC Genom. 2014;15:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ijssennagger N, van der Meer R, van Mil SWC. Sulfide as a mucus barrier-breaker in inflammatory bowel disease? Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(3):190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller TL, Wolin MJ. Formation of hydrogen and formate by Ruminococcus albus. J Bacteriol. 1973;116(2):836–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richards EM, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Kim S. The gut, its microbiome, and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19(4):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rey FE, Gonzalez MD, Cheng J, Wu M, Ahern PP, Gordon JI. Metabolic niche of a prominent sulfate-reducing human gut bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13582–13587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasad KN, Bondy SC. Dietary fibers and their fermented short-chain fatty acids in prevention of human diseases. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018;S0047-6374(18):30013–30017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartolomaeus H, Balogh A, Yakoub M, et al. Short-chain fatty acid propionate protects from hypertensive cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1407–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galla S, Chakraborty S, Cheng X, et al. Exposure to amoxicillin in early life is associated with changes in gut microbiota and reduction in blood pressure: findings from a study on rat dams and offspring. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi Y, Aranda JM, Rodriguez V, Raizada MK, Pepine CJ. Impact of antibiotics on arterial blood pressure in a patient with resistant hypertension - a case report. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:157–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bahr SM, Weidemann BJ, Castro AN, et al. Risperidone-induced weight gain is mediated through shifts in the gut microbiome and suppression of energy expenditure. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(11):1725–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Report of the American Institute of Nurtition ad hoc Committee on Standards for Nutritional Studies. J Nutr. 1977;107(7):1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marques FZ, Jama HA, Tsyganov K, et al. Guidelines for transparency on gut microbiome studies in essential and experimental hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;74(6):1279–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(7):5069–5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41(Database issue):D590–D596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eren AM, Esen OC, Quince C, et al. Anvi'o: an advanced analysis and visualization platform for 'omics data. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Kelley ST, Knight R. Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(5):1576–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.