Abstract

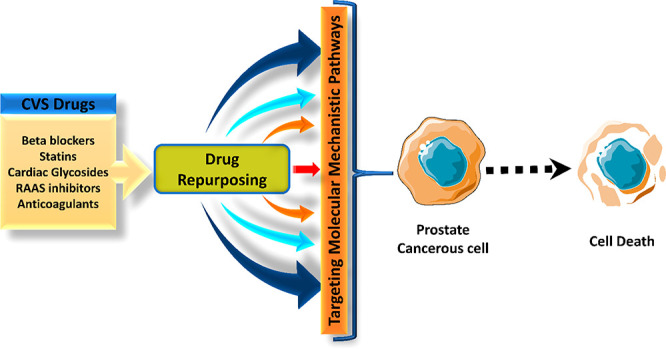

Prostate cancer (PCA), the most common cancer in men, accounted for 1.3 million new incidences in 2018. An increase in incidences is an issue of concern that should be addressed. Of all the reported prostate cancers, 85% were detected in stages III and IV, making them difficult to treat. Conventional drugs gradually lose their efficacy due to the developed resistance against them, thus requiring newer therapeutic agents to be used as monotherapy or combination. Recent research regarding treatment options has attained remarkable speed and development. Therefore, in this context, drug repurposing comes into the picture, which is defined as the “investigation of the off-patent, approved and marketed drugs for a novel therapeutic indication” which saves at least 30% of the time and cost, reducing the cost of treatment for patients, which usually runs high in cancer patients. The anticancer property of cardiac glycosides in cancers was tested in the early 1980s. The trend then shifts toward treating prostate cancer by repurposing other cardiovascular drugs. The current review mainly emphasizes the advantageous antiprostate cancer profile of conventional CVS drugs like cardiac glycosides, RAAS inhibitors, statins, heparin, and beta-blockers with underlying mechanisms.

1. Introduction: Why Repurposing?

Drug repurposing investigates off-patent, approved, and marketed drugs for a novel therapeutic indication. It can be summed up as “teaching new tricks to old drugs”. Currently, it has gained a high demand owing to the time-saving factor and cost-effectiveness, where clinical trials have already deemed them safe, time-saving, and effective considering their pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and toxicity profiles. Viewing a drug molecule with a fresh set of lenses may help further explore its therapeutic benefits beyond its conventional use. An estimated 2–3 billion USD is invested in bringing a single new drug molecule from bench to bedside over an average period of 12–13 years. Taking into account the value of time to control the rate of mortality, it is a crucial juncture to shift our focus to drug repositioning, which can save at least 30% of the time and cost, overcoming a large fraction of financial overload, longer duration of studies, and the uncertainty of desirable outcomes. Therefore, a huge inclination toward methodologies extracting the most from existing approved and marketed drugs becomes highly desirable.1

Although the drug action is target-specific, it usually shows several side effects, some of which can be beneficial in other scenarios. Unexpected clinical trial results have pushed researchers to focus on new mechanisms of drug action that can be termed “bedside to bench”. A new drug indication is claimed based on numerous off-target studies conducted preclinically. This approach is mostly directed toward chronic conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and other orphan diseases.1 Overcoming cancer therapeutic bottleneck attrition has become the growing need of the hour. Opportunities with growing knowledge in oncology can curb the mortality rate and enhance the clinical relevance of mechanistic studies. General de novo drug discovery and development method demand 4–8 long years for preclinical phases to determine drug safety and efficacy with robust data. Preformulation studies, drug design, and experimental in vitro and in vivo models require much funding, trained technical researchers, and long working hours, yet often produce dissatisfactory success rates expected for anticancer drugs. About 5% of oncology drugs befitting phase 1 clinical trials are finally approved, while only 1 in 5,000–10,000 prospective anticancer drugs are granted FDA approval.2 Drug repurposing strategy allows us to skip over phase 1 and swiftly progress to phases 2 and 3 of clinical trials with fewer pharmacodynamic uncertainties.2 Numerous studies on cardiovascular drugs have demonstrated a hallmark response when indicated for antitumor therapy. Despite multiple attempts to find safer yet efficacious alternatives and thousands of drugs being developed, cancer remains one of the deadliest diseases known to humanity.

Cancer treatment has been an exception to the general risk:benefit ratio. Highly toxic drugs, causing harmful and life-threatening side effects, are still used for anticancer chemo- and radiotherapy. The main objective of the treatment is the survival of the patient. Resistance to therapy remains at the top of the innumerable challenges faced in developing an effective dosage regimen. Prostrate cancer (PCA) is classified as a type of adenocarcinoma, where neoplasia of glandular (secretory) cells is observed. This pathophysiology can be closely matched with a target of drugs conventionally used in cardiovascular (CVS) diseases. This cross-link between pathways has been suggested by an imbalance of androgens–testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and androstenedione (steroid hormones), which play a prominent role in inducing PCA. Therefore, corrective hormonal therapy is widely indicated for its treatment.3

Moreover, CVS drug repurposing through experimental studies might help us lay a hand on better alternative or potentially synergistic mechanisms with fewer side effects which can aid in combating PCA. With the advancement in the course of the research, it is now known that various biomarkers of cardiovascular disorders possess similarities with the pathophysiological imbalance of biomarkers observed in PCA. This review focuses on the advantageous anticance profile of conventional CVS drugs like cardiac glycosides, RAAS inhibitors, statins, heparin, and beta-blockers, as multiple studies are proving the same. Epidemiologically proven data regarding the anticancer property of digitalis in the early 1980s was based on studies conducted on BC tissue samples taken from cardiac heart failure patients by Stenkvist and colleagues.4 Cytotoxic activity of many CVS drugs has been a major focus of mechanistic studies elaborating the precise cellular pathways leading to cell death or an increase in sensitivity of tumors toward chemo- and radiotherapy.

Because PCA is the second most common cancer among men, research regarding its treatment options has attained remarkable speed and development. Globally, the highest rates of PCA have been reported in Australia/New Zealand (104.2/100,000), right after Europe and North America.5 The average mortality-to-incidence rate ratio (MR/IR) is observed to be greater in China than in North America, as the patients were already in advanced stages at the time of diagnosis.5 New incidences of PCA, as high as 1.3 million, have been reported in 2018 alone.6 In India, the average annual PCA detection range was 5.0–9.1 per 100,000, whereas the US statistics show 180.9 for African Americans and 110.4 for whites. The absence of statistically sound studies in India has accounted for a limitation whereby researchers cannot report and comprehend the exact situation and distribution of the disease in the country. Rigorous implementation of reporting mechanisms, as well as general awareness, may help gain clarity on the situation.5 Among all PCA cases in India, 85% were detected late (stages III and IV), whereas, in the US, this number was only 15%.5 The current trends, drawbacks of conventional therapies for PCA, and the need to repurpose cardiovascular drugs for PCA are discussed in this article.

2. Limitations of Conventional Therapies for Prostate Cancer

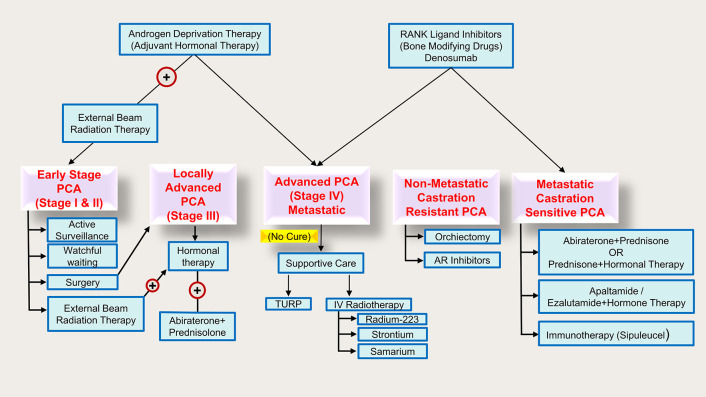

Over the decades, localized tumors have been subjected to surgery and radiotherapy, while advanced and aggressive tumors which become resistant to localized treatment are subjected to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) via medical or surgical castration. However, relapse has been noted despite ADT treatment in which the cancer cells grow aggressively and develop castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPCA).7Figure 1 demonstrates all the currently available treatment approaches for PCA.

Figure 1.

Treatment of PCA by stages.

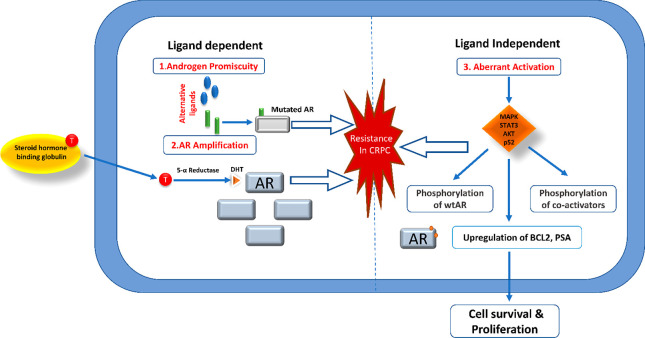

It is important to note that hormonal therapy is not the magic bullet for PCA. The metastatic tumor is initially subjected to antiandrogen-based hormonal modulation, but subsequent resistance cannot be ignored. Hormonal therapy can shrink the tumor size and even inhibit further growth; however, the effectiveness of the therapy is debatable. It is known to interfere with the patient’s life span and quality of life. Elucidating chemo-resistant pathways has become equally important. Patients who will not benefit from chemotherapeutic drugs can be identified and protected from drug-induced toxicities. Research focuses on deriving an alternative treatment option, as not much can be done once the tumor resists therapy. AR amplification-induced hypersensitivity, mutations in AR, cofactors, activators, androgen-independent AR activation, and intratumoral production of androgen are various mechanisms shown to incorporate resistance in CRPCA8 (Figure 2). Another major issue is the limited solubility of some anticancer drugs in an aqueous vehicle due to their hydrophobic nature and low bioavailability. The risk of toxicity, accumulation, and resistance multiplies due to poor aqueous solubility. Multidrug resistance is a major factor responsible for the failure of chemotherapy. Nonspecificity of anticancer drugs increases the risk factor exponentially as they potentially target the healthy dividing cells in the body.9

Figure 2.

Demonstration of different mechanisms of resistance in CRPCA.

The diagnosis, treatment, and related expenses incur a major financial setback for the patients and their families. Prolonged duration of treatments and their side effects also account for the overwhelming healthcare cost borne by the affected individual, especially in a country like India, where the cost of cancer treatment is financially overbearing because of improper healthcare systems and inadequate health insurance policies, making the cost of treatment absurd for many.10 Immunosuppression is a well-known side effect of highly cytotoxic tumor-suppressing agents, eliciting high chances of opportunistic diseases. Because PCA is located near several vital structures, many normal body functions, such as urination, are hindered, along with bowel, sexual, and erectile dysfunctions.11 A drop in platelet count, often resulting in anemia, bleeding, and reduced heart function, is a well-known side effect of chemotherapy with docetaxel.12 Due to a depressed immune system, fatal infection is a recurrent after effect displayed by cabazitaxel, requiring periodic blood transfusion to counter anemia and platelet loss.12 As for hormone therapy, the increased risk of acquired osteoporosis, diabetes, heart attack, and decreased muscle mass is concerning, and prolonged therapy eventually leads to hypogonadism. Unfortunately, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, as equivalently effective as castration, participate in the pathogenesis of hypo-gonadal bone loss by activating the parathyroid-mediated osteoclasts and increasing skeletal sensitivity to parathyroid hormone.13 Even during initial therapy, a decrease of 2% to 3% in bone mineral density has been reported.13 Therefore, it can be acknowledged that the treatment options proposed so far for PCA come with special baggage of side effects and are often insufficient. Table 1 compiles all the current treatment approaches to treat PCA and their associated limitations.

Table 1. Current Treatments for PCA.

| Sr. No. | Type of Treatment | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Active Surveillance | Cancer may regrow or spread, making treatment more difficult and impossible to cure. | (11), (14), (15) |

| B | Watchful Waiting | May feel anxiety over the uncertainty of your condition. | |

| C | Local Treatments | ||

| (1) Surgery: | |||

| (a) Radical (open) Prostatectomy | ED or urine incontinence | ||

| (b) Robotic or Laparoscopic Prostatectomy | Lack of tactile input is the only drawback; side effects are identical to radical prostatectomy (open surgery). | ||

| (c) Bilateral Orchiectomy | Hot flashes, Sterility, Erection problems, Loss of sexual desire | ||

| (d) Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) | Temporary loss of bladder control (incontinence) and UTIs, “dry orgasm” or “dry climax” (retrograde ejaculation), and TUR syndrome can cause CVS issues in rare cases. | ||

| (2) Radiation Therapy: | |||

| (a) External Beam Radiation Therapy: | Gastrointestinal tract (GIT) side effects. May be expensive. IMRT includes patient immobilization and target localization, the need for accurate target delineation, unresolved problems in organ contouring, and management of interfraction target movements. | ||

| -IMRT | |||

| -Proton Therapy | |||

| (b) Brachytherapy (IRT) | The radiation-emitting device(s) must be implanted under anesthesia. Urinary urgency and frequency, burning during urine, ED, and difficulties emptying the bladder are all possible side effects. Rectal bleeding, rectal ulcers, bowel frequency, and urgency are some less prevalent adverse effects. | ||

| (c) Cryosurgery/Cryotherapy/Cryoablation | There is no defined treatment or standard of care to treat newly diagnosed PCA. | ||

| (3) Focal Therapies High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) | Low tumor volume does not ensure unifocal and enhanced detection of Focal PCA Problems with diagnostic tools: for example, men who have had recent biopsies often present with bleeding, which restricts MRI accuracy, leave some tissue untreated, and inevitably leads to an increase in prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and the majority of these treatments have not been approved as standard treatment options. | ||

| D | Systemic Treatments | ||

| (1) Hormonal Therapy: | Hormonal therapy will have adverse effects that normally go away when treatment has been completed, except in patients who have undergone an orchiectomy. The following are some common side effects: | ||

| (a) Bilateral Orchiectomy | Loss of libido | ||

| (b) LHRH Agonists | ED | ||

| (c) LHRH Antagonists: | Weight gain | ||

| -Degarelix, Relugolix | |||

| (d) AR Inhibitors: | Gynecomastia, depression, cognitive impairment, and memory loss | ||

| -Apalutamide, Darolutamide, Enzalutamide | |||

| (e) Androgen Synthesis Inhibitors: | Heart disease and heart problems | ||

| -Abiraterone, Ketoconazole | |||

| (f) Combined Androgen Blockade: | Osteopenia (lower bone density than normal) or osteoporosis (bones become brittle and fragile). | ||

| -AR Inhibitors + Bilateral Orchiectomy/LHRH Agonists | |||

| (g) Intermittent Hormonal Therapy | Hot flashes with sweating | ||

| (2) Targeted Therapy (Poly ADP ribose polymerase-PARP Inhibitors): Olaparib, Rucaparib | Development of drug resistance | ||

| (3) Chemotherapy: Docetaxel, Cabazitaxel | Fatigue, sores in the throat and mouth, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, blood disorders, impairments in cognitive functioning, nervous system impacts, sexual impotence, and reproductive problems, anorexia, pain, and alopecia. Chemotherapy’s side effects generally fade when treatment is done. On the other hand, some adverse effects may persist, reappear, or develop later. | ||

| (4) Immunotherapy: Sipuleucel-T | Skin reactions, weight fluctuations, flu-like symptoms, and diarrhea | ||

| (5) Radiopharmaceuticals: Radium-223, Strontium-89, Samarium-153 | Do not extend life; these drugs deplete numbers of healthy blood cells in those who receive them. | ||

| (6) Bone-Modifying Drugs: Denosumab, Zoledronic acid, Alendronate, Risedronate, Ibandronate, Pamidronate | Osteonecrosis of the jaw is exposed, necrotic bone (very rare) in the maxillofacial region. The signs of jaw osteonecrosis are swelling, inflammation, infection of the jaw, exposed bone, and loose teeth. | ||

3. Repurposing of CVS Drugs for Prostate Cancer Treatment

3.1. Lipid Lowering Agents

A. Statins

The primary human plasma cholesterol source is de novo (an alteration in gene) biosynthesis by cells or dietary intake. Statins lower plasma cholesterol levels by inhibiting biosynthetic cholesterol production and triggering low-density lipids (LDLs) receptor expression changes.16 Statins are the most extensively prescribed lipid-lowering medications that inhibit the hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) enzyme, the rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate (MVA) pathway.17 In addition to antihypolipidemic action, they also have pleiotropic effects like antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, antioxidants, etc. These effects result in anticancer/antitumor properties.18

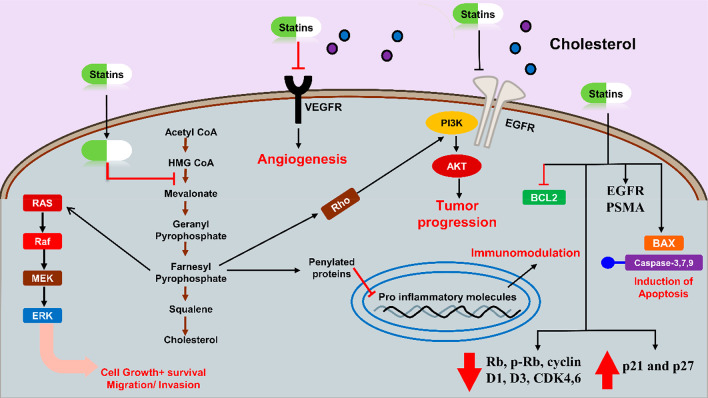

Cholesterol stimulates sex hormone-dependent PCA growth and breast cancer (BC) by supplying androgens and estrogens, respectively.19 Suppression of HMGCR results in a decrease in rate-limiting step in MVA pathway and downstream cholesterol production and the suppression of other isoprenoid metabolites important for post-translational modification of cell signaling proteins and several cellular functions.20In vitro evidence has revealed that statins prevent various hallmarks of cancer, including angiogenesis, tumor metastases, tumor cell proliferation, and activation of apoptosis.21 Depending on their classification, atorvastatin and simvastatin, due to their lipophilic nature, display more pleiotropic effects, potentially more effective as antineoplastic medicines.17 MVA pathway flux is fundamental for all cells, including cancer or tumor cells. Yes-associated protein (YAP) and Tafazzin (TAZ) are responsible for tumor and normal organ growth.22 Statins affect the YAP/TAZ-dependent transcriptional responses by blocking the MVA pathway, reducing cancer cells’ growth.23 Statins are affordable, less toxic, and better tolerated than conventional available chemotherapies, where researchers evaluated the potential of statin in PCA by a drugs repurposing approach.16 Akt is an essential target molecule in the pathophysiology of PCA.19 ATO inhibits proliferation, invasion, EMT, and PTEN/AKT pathways and promotes apoptosis in breast tumor cells.24

A study on 4,204 males underwent prostate biopsy revealed that those who were on statins had a significantly reduced risk (8%) of PCA than those who were not on statins.25 Statin uses also lower the incidence of PTEN-negative and lethal PCA.26 Lovastatin and simvastatin inactivate RhoA in PCA, induce apoptosis and arrest the cell cycle in the G1 phase. Induction of apoptosis is mediated by cytochrome C-dependent and cytochrome C-independent signaling pathways. Both lovastatin and simvastatin increased the activation of caspase-3,8 and, to a limited extent, caspase-9.

Additionally, they decrease the expression of Rb, p-Rb, cyclin D1, D3, and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK4,6) but increase p21 and p27 in PCA cells.19 Combining simvastatin with valproic acid increases the sensitivity of metastatic CRPCA cells to docetaxel. It reverts resistance to docetaxel via MVA pathway/YAP axis activation in in vivo and in vitro models27 (see Table 2 and Figure 3 for the mechanism of statins).

Table 2. Anticancer Effects of Statins for PCA in Preclinical Studies.

| Name (Statins) | Dose (Study type) | Combination agent | Outcomes | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simvastatin and Fluvastatin | 0–10 μM (In vitro) | Inhibit cell proliferation and promote apoptosis | Downregulate the phosphorylation of AKT/FOXO1 | (31) | |

| Simvastatin | 0–50 μM (In vitro) | Irinotecan | Combined therapy suppresses tumor growth and induces apoptosis | Inhibit MCL-1 | (32) |

| 2 mg/kg (In vivo) | Suppress tumor growth | Inhibit Akt and reduce PSA expression | (33) | ||

| 0–100 μM (In vitro) | |||||

| Atorvastatin | 0–50 μM (In vitro) | Irradiation | Improves the radiosensitivity of hypoxia-induced PCA cells | Decreased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) | (34) |

| 0–5 μM (In vitro) | Caffeine | Combined therapy inhibits proliferation and increases apoptosis | Decreased p-Akt, p-Erk1/2, Bcl-2, and survivin levels | (35) | |

| 5 mg/kg or10 mg/kg (In-vivo) | Celecoxib | Combination suppresses tumor growth and progression inhibition in SCID mice and Lymph node carcinoma of the prostate (LNCaP) PCA | Akt, Erk1/2, and NF-κB activation | (36), (37) | |

| 0–10 μM (In vitro) | It also induces autophagy (PCA-3 cells) | Induction of light chain 3 (LC3) transcription | |||

| Atorvastatin, Mevastatin, Simvastatin, and Rosuvastatin | 0–10 μM (In vitro) | Lower migration and colonies (PCA-3 cells) | Inhibit GGPP synthesis | (38) | |

| Lovastatin and Simvastatin | 0–2 μM (In vitro) | Induction of apoptosis induction and cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase | RhoA inactivation | (19) |

Figure 3.

Demonstration of anticancer/antitumor mechanism of statins.

Temporal modulation of an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) by statins on the tumor cell surface improves the activity of mAb cetuximab,28 huJ591, and panitumumab, thus proving the tumor-binding capacity synergistic effect.28 Unfortunately, a minority of patients who received ADT for advanced PCA developed recurring bone CRPCA. But recent studies have revealed that statins can decrease castration-induced bone marrow adiposity and PCA growth.29 Patients with metastatic castration-resistant PCA appear to therapeutically benefit from the combination of statins with the new antiandrogens, suggesting prolonged overall life without a significant adverse effect.30

B. Fibrates (FB)

Fibrates, a class of hypolipidemic medication that reduces TGs and cholesterol (LDL) in the bloodstream, subsequently reduce the risk of cholesterol-associated CVS complications.39,40 These drugs have agonistic activity for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α), primarily expressed on the hepatocytes, myocytes, and skeletal muscles.41

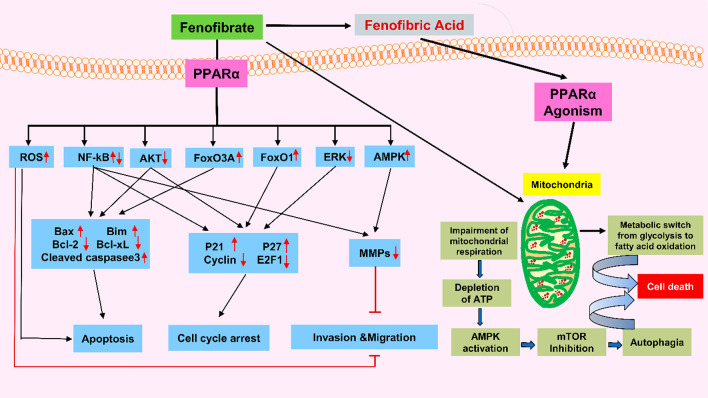

Recently, PPAR-α agonists demonstrated anticancer effects in various cancers, like AML (acute myeloid leukemia),42,43 CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia),44 and solid tumors of liver,45 ovary,46 breast, skin, and lungs.47 Chemically, fenofibrate is propane-2-yl 2-[4-(4-chlorobenzoyl)phenoxy]-2-methylpropanoate. Activation of PPAR-α mediates the lipid-lowering effects of FB.48 LNCaP (PCA cell line) treatment by FB arrested the cell cycle in the G1 stage mediated by downregulation of cyclins D1 and E2F1. Meanwhile, it reduced the Bcl-2 and increased the Bcl-2-associated x protein (Bax) level, ultimately leading to apoptosis.48

Moreover, it diminished the androgen receptor (AR) and androgen receptor target genes (ARTG) by reducing the p-Akt level. Apoptotic effects of FB are also mediated by inducing oxidative stress, further reducing the superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) activity. Conversely, pretreatment with NAC considerably decreases FB-mediated apoptosis in LNCaP cells.49 Clofibrate, another drug from the same class, inhibits cell proliferation mediated by altering the levels of cell cycle inhibitors, checkpoint kinases, and tumor suppressors, possibly in BC.50 The mechanism described above is demonstrated in Figure 4, and in vitro studies are compiled in Table 3. Table 4 lists examples of repurposed drugs for PCA.

Figure 4.

Mechanism involved in the anticancer action of FB.

Table 3. Compilation of In Vitro Studies of Fenofibrate in PCA Cell Line.

| Cell lines | Outcomes | Probable Mechanism | PPAR-α Dependent | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNCaP | Promoted cell cycle arrest and death | (−) Akt Phosphorylation (+) ROS | NA | (51) |

| DU145 | Suppression of cells motility | (+) ROS | X | (52) |

| Increase functions of endothelial barrier (upsetting the adhesion of EC) | (+) ROS | √ | (53) | |

| Reduce metastasis by impairing the cell’s motile activity |

Table 4. Examples of Repurposed Drugs for PCA with Their Strategies for Repurposing.

| Drug Name | Original Indication | Postulated Antitumor Mechanisms | Methods Used for Repurposing | Methods Used for Validation | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naftopidil | α-Blocking activity | -Inhibits prostate tumor growth | Theoretical | In vivo | (76) |

| -Inhibits phosphorylation Akt | In vitro | ||||

| Niclosamide | Antihelminthic | -Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibition | Theoretical | In vitro | (77) |

| -Induces low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP6) degradation | |||||

| Ormeloxifene | EMR | -Inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) progression and β-catenin signaling | Theoretical | In vitro | (78) |

| -Inhibits growth and metastasis of prostate tumor | In silico | ||||

| In vivo | |||||

| Nelfinavir | Antiretroviral | -Suppression of regulated membrane proteolysis | Theoretical | In vitro | (79) |

| -Inhibit cancer cell proliferation | In silico | ||||

| -Apoptosis inducer in PCA | |||||

| Glipizide | Hypoglycemic activity | -Inhibit angiogenesis | Theoretical | In vivo | (80) |

| Ferroquine | Antimalarial | -Negatively regulate HIF-1α and Akt kinase | Theoretical | In vivo | (81) |

| -Inhibiting autophagy | In vitro | ||||

| Nitroxoline | Antibacterial | -AMPK-mediated autophagy induction | Theoretical | In vitro | (82) |

| -Cell cycle arrest (G1), followed by apoptosis | |||||

| Triclosan | Antibacterial | -Blocks the enoyl reductase | Practical | In vitro | (83) |

| -Suppression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) | |||||

| Clofoctol | Antibacterial | -Cell cycle arrest (G1) in PCA cells | Practical | In vivo | (84) |

| -Activation of UPR pathways | In vitro | ||||

| Risperidone | Antipsychotic | -Inhibits 17HSD10 | Computer modeling/simulation | In vivo | (85) |

| In vitro | |||||

| In silico | |||||

| Dexamethasone | Anti-inflammatory | -ERG modulator | Computer modeling/simulation | In vitro | (86) |

| In silico | |||||

| Zenarestat | Aldose reductase inhibitor | -Antagonistic activity for NF-κB pathway | Computer modeling/simulation | (87) |

3.2. Beta-Blockers (BBs)

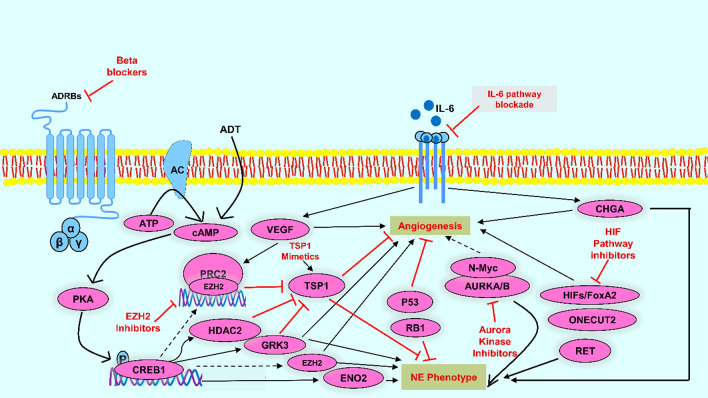

BBs are generally viewed as cardioprotective medications utilized in many conditions (e.g., CAD or hypertension) attributed to their antagonist action on the adrenergic system through inhibition of β-adrenergic receptors.54 Several preclinical and in vitro studies suggest that adrenergic stimulation modifies apoptosis and increases angiogenesis and other cancer hallmarks, and BBs can help eliminate these effects.55 BBs have been investigated for cancer treatment due to their antagonist activity on receptors involved with mechanisms that progress carcinogenesis, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis, which may decrease the high expenditure of cancer treatments and increase survival rates, especially in BC56 In the past, BBs were known to block β-adrenergic signaling and the activation of PKA-CREB1. BBs were recently investigated for their antineoplastic activity as β-adrenergic receptors’ activation is linked with angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, and migration.57,58 Epidemiological studies suggest that cancer patients (melanoma, lungs, breast, and prostate cancer) on BBs for CVDs showed superior clinical results as compared to the controlled patients.57,59,60 BBs might prove an effective and reliable therapy for neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPCA). Propranolol treatment downregulates NE markers’ expression, inhibiting angiogenesis and developing NEPCA cell-derived xenografts by perturbing the CREB1-EZH2-TSP1 pathway61 (see Figure 5). For tumorigenic activity, the human prostate cancer cell line (PC3) PCA cells require basal flux of autophagy.62 Propranolol administration increases p62 and LC3-II levels (autophagy markers). The 2DG + propranolol combination increased cell death by 4.9× in PC3 cell lines.63 Human PCA cells demonstrated a rise in the level of cAMP after β-ARs agonist administration (terbutaline > isoproterenol > epinephrine > NE). The nonspecific BBs, CGP 12177, and propranolol were detected to suppress this function up to 80–96%, suggesting their role in PCA cells.64 BBs use also curtailed PCA-specific fatality in patients apperceived with ADT.65

Figure 5.

Potential anticancer properties of BBs.

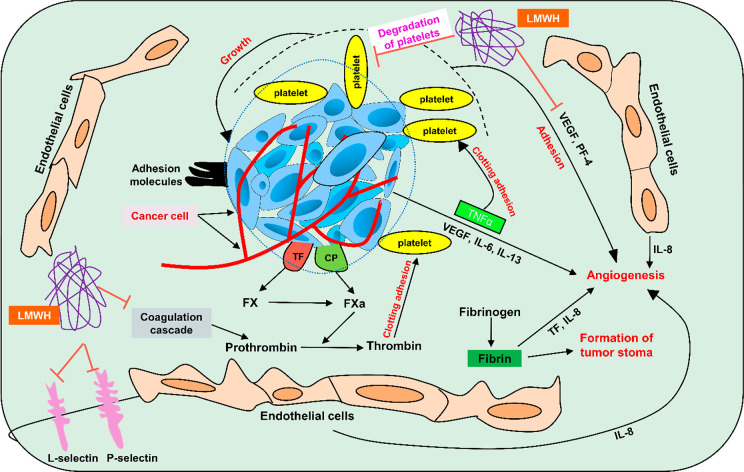

3.3. Heparin

For a decade, heparin has been the most commonly prescribed anticoagulant. Recently, researchers shifted their interest to exploring its nonanticoagulant properties. Data from several studies suggest its potential as an anti-inflammatory and antimetastatic agent in cancerous cells. Molecularly, it disturbs the expression, synthesis, and function of cytokines, adhesion molecules, angiogenic factors (VEGF), and complement proteins.66 Tumor-mediated coagulation cascade activation results in hemostasis dysregulation, which further causes VTE, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and PE in cancerous patients. VTE is considered the prominent cause of cancer-related illness and fatality.67

Additionally, various tumor-associated coagulation factors (tissue factor, fibrin, thrombin, and plasmin) are implicated in tumor cell survival and progression, including tumor stroma formation, migration and adhesion, antitumor immune evasion, induction of oncogenes, and angiogenesis.68,69 Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) presents an antiangiogenic action via fibrin structural changes, inhibiting the endothelial factor pathway and directly inhibiting ligand binding to VEGF receptor.70 Heparin additionally demonstrated antimetastatic action mediated by blocking P- and L-selectin, chemokines regulation, and suppressed heparinase activity71−73 (mechanism depicted in Figure 6). Furthermore, heparin dramatically decreased metastases in a murine CRPCA model.74

Figure 6.

Mechanism of heparin as an anticancer agent.

The cancerous growth of prostate cells is associated with dysregulated expression of different growth factors and allied receptors. In recent years, intensive research has been conducted on FGF2 family signaling, having a demonstrated role in the initiation and progression of PCA. Clinically, FGF2 is linked with malignant prostate growth and higher serum FGF2 levels found in PCA patients.75 HARP, or pleiotropic, is a vital modulator of FGF2 stimulatory actions.

3.4. Cardiac Glycosides (CGs)

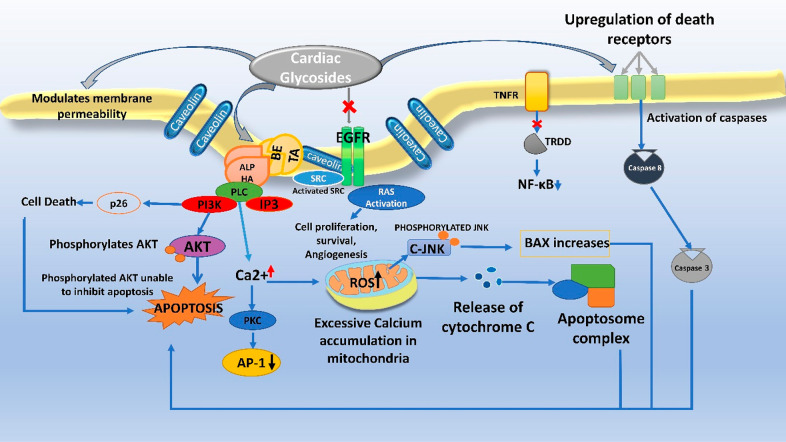

Cardiac glycosides such as digitoxin, digoxin, ouabain, strophanthidin, and peroxides are steroid-like structures used therapeutically in congestive heart failure (CHF), atrial fibrillation, and atrial flutter for decades. Their fundamental pharmacological action is to increase the rate of contraction of cardiac muscles, where the major mechanism of action is blocking of cellular Na+/K+-ATPase and increasing intracellular calcium concentration. CGs are known to have a narrow therapeutic index; therefore, an in-depth study of in vitro models giving reproducible, robust data is expected before planning in vivo studies.88 Studies demonstrate that certain mutations in the Na+/K+ pump lead to the proliferation of tumor cells.89 Due to the understanding that abnormalities and deregulations in Na+/K+-ATPase pumps are frequently observed in malignancies, CGs have emerged as a promising candidate for the treatment of solid tumors targeting the apoptotic pathways, cell cycle arrest, and sensitizing the cancer cells to chemo- and radiotherapies. Signaling pathways like p38 MAPK, EMT, PI3K/Akt/mTOR (PAM), cholesterol homeostasis, and p21 Cip, which are involved in the pathogenesis of PCA cells, are linked with alpha and beta subunits of Na+/K+-ATPase.90 Proteases targeted by cardiac glycosides are now being explored for anticancer effects. The glycosylated β-subunit, a chaperone for the enzyme, is involved in cancerous cell metastasis, and the α-subunit, catalytic in nature, is downregulated during the disease. Regulation of beta subunit in normal physiological conditions shows active involvement in structural maturation of the Na+/K+-ATPase; however, the suppression of a beta subunit in pathological conditions is responsible for loss of the tight junctions and the subsequent motility leading to metastasis.90 The clinical indication of CGs in PCA has appreciable safety. Still, the efficacy parameter needs improvement because the clinical study results have not been significant, owing to the small sample size. Therefore, considerable sample size and randomized and controlled trials are needed to have a robust data set to improve the clinical relevance of these findings further.91

Postulated Mechanisms

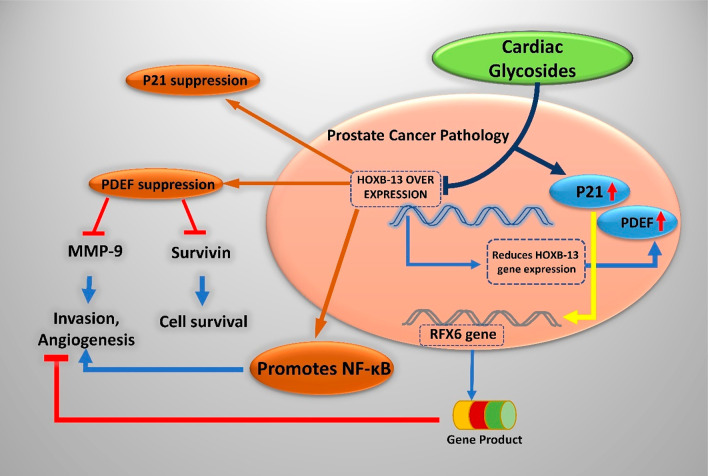

Cardiac glycosides of the category cardenolides have a plant origin (5-membered butyrolactone ring at 17th carbon), and bufadienolides obtained from animals like frog skin and carotid gland toads (6-membered pyrone-unsaturated lactone ring) are being repurposed for anticancer activity. A common structural feature of these glycosides is a steroidal ring of 17 carbon atoms, an unsaturated lactone ring on 17th carbon in beta conformation, and a sugar moiety on 3-OH. The sugar moiety, the glycone part of CGs, modulates the pharmacokinetic property of the drug, while the aglycone moiety elicits pharmacological responses. They kill the cancerous cells by induction of apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest and suppress the cytokine storm, which induces antiproliferative action, first demonstrated by Johnson et al.90 The anticancer activity of CGs can be categorized into antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity. Certain CGs like Huachansu, which are bufadienolides, also can enhance radiotherapy sensitivity.91 A genetic-level understanding helps the researcher pinpoint the disease’s biomarkers precisely. The HOXB-13 gene is the master transcriptional factor regulating PCA’s metastasis by suppressing prostate-derived Ets factor (PDEF) expression in PC3 cell lines while also green signaling cell migration and invasion. It is involved in unmasking the metastatic characteristics of prostate tumors.92 Techniques like DNA microarray analysis and gelatin zymography assay hint toward the altered expression of the transcription factor, HOXB-13 gene, which is a homeodomain, being responsible for tumorigenesis of the prostate, ovary, and breast tissues.92 From the results obtained for the human PC3 cell line, it has been established that ouabain and digitoxin trigger apoptosis by inhibiting the expression of HOXB-13, hPSE/PDEF hepatocyte nuclear factor-3α, and survivin.93 Survivin essentially blocks the apoptotic pathway. The novel HOXB13 G84E variant has been attributed to the gene associated with the risk of hereditary PCA, with mutations occurring in this gene segment feared to be inherited by the next generation. Inhibiting genetic expression thereby halts the mechanistic cascade that results in the formation of survivin, which is a beneficial approach in combating PCA.93

Ouabain has shown remarkable anticancer activity in nanomolar concentrations against androgen-independent PCA. Patented by the United States as Anvirzel (oleandrin and oleandrigenin extract),94 it is another promising candidate whose activity results in the loss of telomeric DNA. It can arrest the cell in G2 or the M phase by bringing the cyclins and CDK functioning to a halt, thereby inducing apoptosis in human PC3 and C-42 cells. It is remarkable to note that the effects seen are produced in nontoxic doses. It has been postulated to decrease the TRF2 levels, induce endomitosis, and enhance DNA fragmentation which is also linked to Anvirzel administration. Oleandrin with EC50 of 0.001–0.002 μg/mL shows activation of caspases, PARP, downregulation of procaspase-3, and inhibitory activity toward NF-κB and FGF-2 regulates cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase.95 Ouabain causes endocytosis of Na+/K+-ATPase and degradation, whereas the cell cycle inhibitor p21 Cip shows enhanced expression.96 Ouabain, independent of the Na+/K+-ATPase alpha subunit, downregulates another marker of cancerous cells STAT3 while inhibiting its protein synthesis.

STAT3 is overexpressed in malignancy.97 Marginal toxic doses or chronic low doses (below 100 nM) of digitoxin, digoxin, and ouabain, which tend to be non-lethal, modulate the PDEF gene expression in the human PCA cell line LNCaP,98 and there is a considerable down-regulation of prostate-specific antigen and prostate regulated Ets factor expression revealed by RT-PCR and immunoblot. A 30% decrease in prostate-derived Ets factor expression is reported when LNCaP cells were exposed to 25 nM digitoxin.98 Malignant epithelial cells resist apoptosis, bypassing the natural process of “anoikis” (apoptosis due to detachment of epithelial cells from the extracellular matrix), which ensures and facilitates the survival of the tumors.99 Two thousand off-patent drugs and certain natural products were screened to find a novel anoikis sensitizer. Five potent candidates belongs to the family of cardiac glycosides ouabain, digoxin, digitoxin, strophanthidin, and peruvoside.99 The ouabain induces hypo-osmotic stress and sensitizes the anoikis-resistant neoplastic cells to apoptosis, thereby controlling cancer cell proliferation.99 In addition to the known Na+/K+-ATPase inhibition, digoxin also blocks HIF-1 alpha protein synthesis, which is overexpressed in PCA.100 A screening of two drug libraries, which included over 1700 FDA-approved compounds, aimed at finding inhibitors of TGFβ-induced CAF (cancer-associated fibroblasts) differentiation, highlighted a novel repositionable modality of cardiac glycosides (digoxin).101 At nanomolar concentrations, digoxin shows potent inhibitory effects on TGFβ-induced fibronectin expression without observable cytotoxicity and hinders the suppression of multiple CAF biomarkers as a result, inhibiting the contraction of fibroblasts in extracellular matrix and emerges as a new focus for antiprostate cancer drug regime along with other solid tumor cancers, evident through multiple fibroblasts cell lines testing using real time qPCAR.101 Digitoxin and digoxin decreased E-26 factor gene expression that brought down PSA levels. Table 5 enlists all CGs with their potentials in PCA, while Figure 7 depicts general mechanism of CGs involved in anticancer activity and Figure 8 shows genetic regulation by CG in PCA.

Table 5. Anticancer Effects of Cardiac Glycosides for PCA in Preclinical Studies.

| Drugs | Aglycone/Active Moiety | Dose | Brand Name | MOA | Other Indications | Repurposed Target | Obstacles Overcome Incurrent Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouabain | Ouabagenin | 1–10 μM | Strodival109 | Nonselective inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase109 | Antivirus,110 effective against BC,99 radio-sensitizer for cervical cancer111 | Increases expression of PAR 4, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential,112 reduces HOXB-13 gene expression, inhibits topoisomerase 1 and 2 | Downregulation of STAT3 is independent of Na+/K+-ATPase inhibition |

| Strophanthidin | Tamarin, k-strophanthidin | Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor | Antiviral | Induces apoptosis in anoikis-resistant prostate cancer cells99 | |||

| Digitoxin | Digitoxigenin | 1–10 μM | Lanoxin | Antiangiogenic | Inhibits HIF-alpha 1 synthesis, AR- antagonist,100 reduces HOXB-13 gene expression | Selective toxicity against solid tumors113 | |

| Digoxin | Digoxigenin | 1–10 μM | Cardoxin | High-risk myelodysplastic syndrome,114 medulloblastoma115 | Inhibits HIF-alpha synthesis, AR- antagonist.100 Inhibits TFGβ-induced CAF differentiation | Selective toxicity against solid tumors113 | |

| Thevetia | Peruvoside | Encordin | Myeloid leukemia, breast, lung, and liver116 cancer116 | Androgen receptor antagonist | Potent inhibitor of androgen-sensitive and resistant PCA. Induces AR degradation | ||

| Oleandrin | Oleandrigenin | 0.001 μg/mL, 0.002 μg/mL | Anvirzel | Increases calcium-induced calcium release CICR | Anti-inflammatory, anti-HIV, neuro-protective, antimicrobial, antioxidant | Na+/K+-ATPase, caspase activation. Inhibits export of FGF-2117 | Effective in nontoxic doses, given in combination with cisplatin exhibits synergy118 |

| Huachansu | Bufalin | Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor | Hypertensive, respiratory stimulator, anesthetic, anti-inflammatory119 | Downregulation of aurora A recruitment delays mitotic entry and mitotic arrest120 | Cytostatic, synergistic with nintedanib, when administered via albumin submicrospheres121 |

Figure 7.

Anticancer mechanism of cardiac glycosides.

Figure 8.

Genetic regulation in PCA by cardiac glycosides.

3.5. RAAS Inhibitors

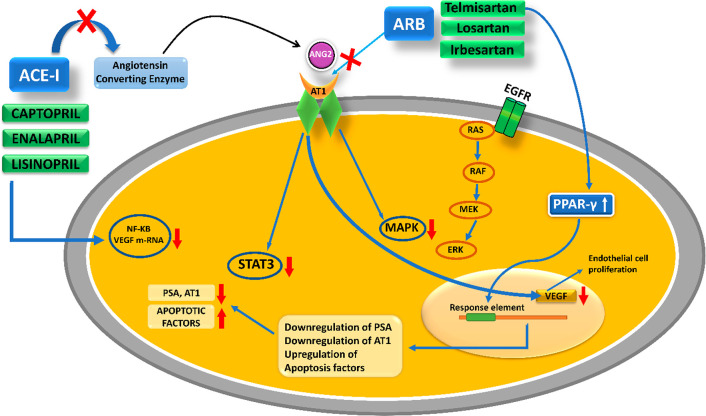

The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is a crucial hormonal regulatory system involved in the homeostasis of blood volume and systemic arterial pressure. Angiotensin 2 (ANG2) is the most important bioactive peptide among all the other RAAS cascade intermediates. It modulates sodium and water absorption by stimulating zona glomerulosa cells to secrete aldosterone and acts as a potent vasoconstrictor. These 3 regulatory components of aldosterone act to raise arterial blood pressure, contract the vascular smooth muscles, and alter renal sodium water absorption.102 Long-term regulation of blood pressure is under neuro-hormonal control of RAAS. Renin, an aspartic protease, and ANG2, the bioactive octapeptide hormone a potent vasoconstrictor, are major targets for treating hypertensive disorders. Recent investigations have shifted the dimensional view from the endocrine (systemic) functions of RAAS toward its autocrine or paracrine(local) role. Studies correlating antihypertensive medications with cancer have brought a broader perspective of repurposing RAAS inhibitors. Rediscovering drugs targeting reno-cardiovascular system abnormalities is now emerging to aid anticancer dosage regimens. Paracrine activity and participation of ANG2 in cell differentiation and growth have linked its role to cell proliferation and hyperplasia in various cancers.103 On examining the expression of cellular localization of ANG2 and AT1 proteins in normal prostate and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) for their immunohistochemical characteristics, it was observed that in the hyperplastic acini of diseased prostate, the immunoreactivity of ANG2 was elevated. In contrast, the AT1 receptor immunoreactivity was decreased, suggesting downregulation of the receptor by an increased local level of ANG2.103 Angiotensin II type I receptors (AGTR1) are an AT4 system that is also supposedly local to the glandular epithelium and might be responsible for glandular secretions in the prostate gland. The paracrine functions of AT1 and ANG2 have devised a role in cell growth, differentiation, and smooth muscle tone in the human prostate. The claim has been backed up by studies showing the presence of ANG2, specifically in the basal layer of epithelium in the prostate and AT1 receptor in stromal muscles.103 A retrospective cohort study performed by Lever et al. resulted in a positive possibility of the protective function of ACE inhibitors against PCA.104 In a UK database, it is evident that captopril users show a comparatively lower risk of developing PCA.105 Captopril crosses the blood seminal plasma barrier and reduces the incidence of PCA in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Once-preventive effects of captopril were noticed through various mechanisms like bringing oxidative stress under the limit, reducing its intensity, and acting as an anti-inflammatory.106 The DNA damage marker 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels are lowered by administering captopril. Enalapril, another ACE-I, downregulated VEGF mRNA and transcription factor NF-κB in mice genetically engineered to demonstrate the pathology of PCA. Neovascularization is expected with ANG2-triggered expression of different growth factors like angiopoietin 2, vascular endothelial factor (EF), FGF, PDGF, and EGF (epidermal growth factor) while, in tumoral experimental models, the blockade of ANG2 has produced antineoplastic and angiogenesis inhibitory effects.107 The altered expression of ANG2 provides direction to several signaling pathways that upregulate the transcriptional proteins HIF-1 alpha and Ets-1 and stimulate the EGF receptor, which gears up tumor proliferation. MAPK and STAT3 pathways are also triggered. Additionally, ANG2 is said to exhibit cancer pathology by producing the signal protein VEGF, which causes the stimulation of angiogenesis. VEGF provides nutrients to the tumor to meet its energy demands and enhance cell proliferation.107 Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are potentially indicated for blocking the cancerous pathological pathways triggered by ANG2. ARB blocks ANG2-activated MAPK and STAT3 and ones stimulated by EGF.108 ARBs negatively target the phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK and suppresses the paracrine loop of cytokine secretion from the prostate stromal cells. ACE inhibitors are not as strong as ARB in anticancer activity for two reasons. Primarily ACE inhibitors do not inhibit completely ANG2 production, whereas ARBs block AT1 receptors and prevent its activation by ANG2. Second, ARBs produce antiproliferative effects by increasing the bioavailability of ANG2.108 Telmisartan, irbesartan, and other ARBs were tested in vitro on LNCaP and PC3 cell lines. Telmisartan is a potent PPAR-gamma stimulator known to induce early apoptosis in cells. For a graphical demonstration of the RAAS inhibitor’s mechanism, see Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Postulated anticancer mechanism of ARB and ACE-I against PCA.

Future Directions

Many noteworthy examples have revolutionized the drug discovery process by drug repurposing. Several drugs already approved for other ailments are also approved for cancer.122,123 Although the success rate may not be high, research is about finding novel ideas and rediscovering things to serve humanity. There are many examples where drug repurposing was successful but seldom passed in clinical or preclinical phases. If we talk about CVS drugs, they have shown very promising results with good efficacy in preclinical settings, as discussed earlier. However, the toxicity of the CVS drugs in the in vivo models still needs to be determined. The challenge lies in whether we can repurpose CVS drugs for PCA in clinical settings like the preclinical level. The main challenge is the therapeutic efficacy and responsiveness that needs to be deciphered. Gaining confidence from the previous studies where scientists discovered many drugs that can be repurposed for other ailments, for example, metformin, which was earlier used for diabetes and is now additionally used for polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), was a remarkable breakthrough in the drug discovery process. The main challenge is determining if these drugs make it to clinical settings, considering all regulatory requirements. Because of the promising pharmacological pathways CVS drugs demonstrate, we get scientific proof of therapeutic efficacy by molecular crosstalk, which we discussed for each class. Combination therapies with CVS drugs could be another approach to treating PCA. There is an immense need for further studies to give a big breakthrough in drug discovery against PCA.

Despite all the benefits of CVS drugs in PCA, some barriers prevent its translational use. One is adverse effects and side effects associated with each class of CVS drugs. For instance, studies suggest that heparin use in cancer patients may lead to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and associated complications than in patients without cancer.124 Another example is the use of cardiac glycoside to treat cancer requires a very high concentration and is not tolerated by normal cells. Additionally, CG’s estrogen-like activity also increases the risk of a certain type of cancer (most commonly BC).125 Studies also reported that ACEIs (>5 years) also increase the risk of lung cancer.126 RAAS inhibitors also developed hypertension resistance in cancer patients to control blood pressure. Thus, the efficacy of RAAS inhibitors in blood pressure control in cancer therapy is still unclear.127 The above-mentioned negative impacts of these drugs reduce the optimism for their use in cancer treatment. Moreover, drug repurposing also faces huge challenges like shorter patent duration (3 years) and low return on investment. CVS drug repurposing for PCA is still in the initial phase. Further studies are required to confirm their clinical translation.

Another cause for the failure of these drugs clinically is publications producing misleading research, which cannot be reproduced. This problem with reproducibility in preclinical settings prevents their translatability.128 So, there is a need to develop a proper methodology to test all drugs intended for repurposing to avoid failure in a clinical trial phase with minimum cost. The published publication needs to be cross-checked before going to the first step of translatability. Using artificial intelligence (AI) technology, the drug-repurposing approach can further reduce the attrition rate (failure of clinical translation of drugs) and quicken the drug development process, pharmaceutical productivity, and clinical trials.

4. Conclusion

The drug repurposing method has the potential to break the conspicuous drug shortage bottleneck. The use and production of nononcology drugs has always been the bulk of medication. Many of the serendipitous findings are a boon for drug repositioning. More research, database, and clinical trial records restructuring is required before affirmative statements can be made regarding repurposing CVS drugs against PCA. Cancer continues to be one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Mono- or polycombination therapy can be expected with the repurposed entities, which can be effective add-ons to the existing conventional dosage regime. More research is necessary to determine the repurposed drugs’ efficacy and potency. Nononcology drugs targeting multiple, complex, and intertwined cancer pathways should be explored and repositioned along with current therapies to control metastasis better. CVS drugs have shown immense potential in vitro as antiproliferative agents through various mechanisms. Statistically sound data and well-planned clinical trials with regular follow-ups are required to establish a clear correlation with the disease for which the drug must be repurposed. Some research studies have obtained contradictory results, which need to be validated for repurposed drugs. The clinical importance of drug repositioning is gradually gaining significance with time. These multipurpose drugs shall gain a higher priority in the future; therefore, upcoming research should be diverted in this direction.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the facilities provided by University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- μM

micromolar

- 17HSD10

17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10

- 2DG

2-deoxy-d-glucose

- ACE

1-angiotensin converting enzyme 1

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- AGTR1

angiotensin II type I receptor

- AP

1-activator protein 1

- Akt

protein kinase

- AMPK

AMP activated protein kinase

- ANG2

angiotensin 2

- AR

androgen receptors

- ARBs

angiotensin receptor blockers

- ARTG

androgen receptor target genes

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- AURKA/B

aurora kinase A/B

- BAX

Bcl-2-associated x protein

- BBs

beta blockers

- BC

breast cancer

- BCL2

B cell lymphoma 2

- BCL

XL-B-cell lymphoma-extra-large

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CHGA

chromogranin A

- CP

cancer procoagulant

- CREB

cAMP-response element binding protein

- CRPCA

castration-resistant prostate cancer

- CVS

cardiovascular system

- DVT

deep vein thrombosis

- E2F1

E2F transcription factor 1

- EBRT

external beam radiation therapy

- ED

erectile dysfunction

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ENO2

enolase 2

- ERG

ETS related gene

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- ERK

extra cellular signal-regulated kinase

- Ets

erythroblasts transformation specific

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homologue 2

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- FB

fibrate

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- FGFRs

fibroblast growth factor receptors

- FOXA2

forkhead box protein A2

- FOXO1

forkhead box protein O1

- FOXO3A

forkhead box O3

- FX

factor X

- G1 Phase

gap 1 phase or growth 1 phase

- GGPP

geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate

- GIT

gastrointestinal tract

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- GRK3

G-protein-coupled receptor kinase

- HARP

heparin affin regulatory peptide

- HDAC2

histone deacetylase 2

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HIF1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HIFU

high intensity focused ultrasound

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- hPSE

human pluripotent stem cells

- IL

interleukin

- IMRT

intensity-modulated radiation therapy

- IRT

internal radiation therapy

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LC3

light chain 3

- LDL

low density lipids

- LHRH

luteinizing hormone releasing hormone

- LMWH

low molecular weight heparin

- LNCaP

lymph node carcinoma of the prostate

- LRP6

low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MCL1

myeloid cell leukemia-1

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MVA

mevalonate

- NAC

N-acetyl cysteine

- NE

norepinephrine

- NEPCA

neuroendocrine prostate cancer

- NF

κB-nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells

- ONECUT2

one cut homeobox 2

- p

AKT-phosphorylated kinase protein-B

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- PCA

prostate cancer

- PC3

human prostate cancer cell line

- PDEF

prostate derived Ets factor

- PE

pulmonary embolism

- PF 4

platelet factor 4

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PPAR α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- PSMA

prostate specific membrane antigen

- PTEN

phosphatase and TENsin homologue deleted on chromosome 10

- RANK

receptor activator of NF-κB

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- RET

rearranged during transfection

- RhoA

RAAS homologue family member A

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TAZ

tafazzin

- TCS

triclosan

- TF

tissue factor

- TGs

triglycerides

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane protease serine 2

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TSP1

thrombospondin-1

- TUR syndrome

transurethral resection syndrome

- TURP

transurethral resection of the prostate

- UTIs

urinary tract infections

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

- Wnt

wingless/integrated

- YAP

yes-associated protein

- β-AR

beta adrenergic receptor

Author Contributions

Jonaid Ahmad Malik: Conceptualization and writing original draft; Sakeel Ahmed: Writing original draft; Sadiya Sikandar Momin and Sijal Shaikh: Literature search and writing; Alfnan Ahmed: Critical review; Jowaher Alanazi: Writing and editing; Sirajudheen Anwar: Conceptualization, Supervision, Editing, and finalizing.

Author Contributions

† J.A.M. and S.A. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ishida J.; Konishi M.; Ebner N.; Springer J. Repurposing of Approved Cardiovascular Drugs. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14 (1), 1–15. 10.1186/s12967-016-1031-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosengo N. Can You Teach Old Drugs New Tricks?. Nature 2016, 534 (7607), 314–316. 10.1038/534314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder F. H. Prostate Cancer. Cancer Screen. Theory Pract. 2021, 461–514. 10.1201/9780429179587-21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pongrakhananon V. Anticancer Properties of Cardiac Glycosides. Cancer Treat. - Conv. Innov. Approaches 2013, 10.5772/55381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan K.; Padmanabha V. Demography and Disease Characteristics of Prostate Cancer in India. Indian J. Urol. 2016, 32 (2), 103–108. 10.4103/0970-1591.174774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Fuchs H. E.; Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71 (1), 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritch C.; Cookson M. Recent Trends in the Management of Advanced Prostate Cancer [Version 1; Peer Review: 3 Approved]. F1000Research. 2018, 7, 1513. 10.12688/f1000research.15382.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekar T.; Yang J. C.; Gao A. C.; Evans C. P. Mechanisms of Resistance in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC). Transl. Androl. Urol. 2015, 4 (3), 365–380. 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.05.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidambaram M.; Manavalan R.; Kathiresan K. Nanotherapeutics to Overcome Conventional Cancer Chemotherapy Limitations. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. a Publ. Can. Soc. Pharm. Sci. Soc. Can. des Sci. Pharm. 2011, 14 (1), 67–77. 10.18433/J30C7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira C.; Bremner K. E.; Pataky R.; Gunraj N.; Chan K.; Peacock S.; Krahn M. D. Understanding the Costs of Cancer Care before and after Diagnosis for the 21 Most Common Cancers in Ontario: A Population-Based Descriptive Study. C. Open 2013, 1 (1), E1-E8 10.9778/cmajo.20120013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. Z.; Zhao X. K.. Prostate Cancer: Current Treatment and Prevention Strategies. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal.; Brieflands; 2013; pp 279–284. 10.5812/ircmj.6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurgali K.; Jagoe R. T.; Abalo R. Editorial: Adverse Effects of Cancer Chemotherapy: Anything New to Improve Tolerance and Reduce Sequelae?. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 10.3389/fphar.2018.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. R.; Bruland; Pearse; Coleman; Suva; Weilbaecher Treatment-Related Osteoporosis in Men with Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12 (20), 6315s. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebello R. J.; Oing C.; Knudsen K. E.; Loeb S.; Johnson D. C.; Reiter R. E.; Gillessen S.; Van der Kwast T.; Bristow R. G. Prostate Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7 (1), 1–27. 10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto R. R.; Maher K. E. Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2001, 17 (2), 90–100. 10.1053/sonu.2000.23071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Hu J. W.; He X. R.; Jin W. L.; He X. Y. Statins: A Repurposed Drug to Fight Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40 (1), 1–33. 10.1186/s13046-021-02041-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joharatnam-Hogan N.; Alexandre L.; Yarmolinsky J.; Lake B.; Capps N.; Martin R. M.; Ring A.; Cafferty F.; Langley R. E. Statins as Potential Chemoprevention or Therapeutic Agents in Cancer: A Model for Evaluating Repurposed Drugs. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23 (3), 29. 10.1007/s11912-021-01023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalipati N.; Shah J.; Ramakrishan A.; Vasnawala H. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 19 (5), 554–562. 10.4103/2230-8210.163106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque A.; Chen H.; Xu X. C. Statin Induces Apoptosis and Cell Growth Arrest in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17 (1), 88–94. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzerro P.; Proto M. C.; Gangemi G.; Malfitano A. M.; Ciaglia E.; Pisanti S.; Santoro A.; Laezza C.; Bifulco M. Pharmacological Actions of Statins: A Critical Appraisal in the Management of Cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64 (1), 102–146. 10.1124/pr.111.004994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindler K.; Cleeland C. S.; Rivera E.; Collard C. D. The Role of Statins in Cancer Therapy. Oncologist 2006, 11 (3), 306–315. 10.1634/theoncologist.11-3-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo S.; Cordenonsi M.; Dupont S. Molecular Pathways: YAP and TAZ Take Center Stage in Organ Growth and Tumorigenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19 (18), 4925–4930. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino G.; Ruggeri N.; Specchia V.; Cordenonsi M.; Mano M.; Dupont S.; Manfrin A.; Ingallina E.; Sommaggio R.; Piazza S.; et al. Metabolic Control of YAP and TAZ by the Mevalonate Pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16 (4), 357–366. 10.1038/ncb2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.; Gao Y.; Xu P.; Li K.; Xu X.; Gao J.; Qi Y.; Xu J.; Yang Y.; Song W. Atorvastatin Inhibits Breast Cancer Cells by Downregulating PTEN/AKT Pathway via Promoting Ras Homolog Family Member B (RhoB). Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1. 10.1155/2019/3235021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan N.; Klein E. A.; Li J.; Moussa A. S.; Jones J. S. Statin Use and Risk of Prostate Cancer in a Population of Men Who Underwent Biopsy. J. Urol. 2011, 186 (1), 86–90. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allott E. H.; Ebot E. M.; Stopsack K. H.; Gonzalez-Feliciano A. G.; Markt S. C.; Wilson K. M.; Ahearn T. U.; Gerke T. A.; Downer M. K.; Rider J. R.; et al. Statin Use Is Associated with Lower Risk of PTEN-Null and Lethal Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26 (5), 1086–1093. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannelli F.; Roca M. S.; Lombardi R.; Ciardiello C.; Grumetti L.; De Rienzo S.; Moccia T.; Vitagliano C.; Sorice A.; Costantini S. Synergistic Antitumor Interaction of Valproic Acid and Simvastatin Sensitizes Prostate Cancer to Docetaxel by Targeting CSCs Compartment via YAP Inhibition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39 (1), 213. 10.1186/s13046-020-01723-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira P. M. R.; Mandleywala K.; Ragupathi A.; Lewis J. S. Acute Statin Treatment Improves Antibody Accumulation in EGFR- And Psma-Expressing Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26 (23), 6215–6229. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T.; Lin S. C.; Lee Y. C.; Yu G.; Song J. H.; Pan J.; Titus M.; Satcher R. L.; Panaretakis T.; Logothetis C.; et al. Statins Reduce Castration-Induced Bone Marrow Adiposity and Prostate Cancer Progression in Bone. Oncogene 2021, 40 (27), 4592–4603. 10.1038/s41388-021-01874-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariano R.; Tavares K. L.; Panhoca R.; Sadi M. Influence of Statins in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Patients Treated with New Antiandrogen Therapies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2022, 20, eRW6339 10.31744/einstein_journal/2022RW6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J. L.; Zhang R.; Zeng Y.; Zhu Y. S.; Wang G. Statins Induce Cell Apoptosis through a Modulation of AKT/FOXO1 Pathway in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 7231–7242. 10.2147/CMAR.S212643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqudah M. A. Y.; Mansour H. T.; Mhaidat N. Simvastatin Enhances Irinotecan-Induced Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer via Inhibition of MCL-1. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26 (2), 191–197. 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochuparambil S. T.; Al-Husein B.; Goc A.; Soliman S.; Somanath P. R. Anticancer Efficacy of Simvastatin on Prostate Cancer Cells and Tumor Xenografts Is Associated with Inhibition of Akt and Reduced Prostate-Specific Antigen Expression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 336 (2), 496–505. 10.1124/jpet.110.174870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Zhang M.; Xing D.; Feng Y. Atorvastatin Enhances Radiosensitivity in Hypoxia-Induced Prostate Cancer Cells Related with HIF-1α Inhibition. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37 (4), BSR20170340. 10.1042/BSR20170340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang L.; Wan Z.; He Y.; Huang H.; Xiang H.; Wu X.; Zhang K.; Liu Y.; Goodin S.; et al. Atorvastatin and Caffeine in Combination Regulates Apoptosis, Migration, Invasion and Tumorspheres of Prostate Cancer Cells. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26 (1), 209–216. 10.1007/s12253-018-0415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Cui X. X.; Gao Z.; Zhao Y.; Lin Y.; Shih W. J.; Huang M. T.; Liu Y.; Rabson A.; Reddy B.; et al. Atorvastatin and Celecoxib in Combination Inhibits the Progression of Androgen-Dependent LNCaP Xenograft Prostate Tumors to Androgen Independence. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3 (1), 114–124. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer N.; Childress C.; Parikh A.; Rukstalis D.; Yang W. Atorvastatin Induces Autophagy in Prostate Cancer PC3 Cells through Activation of LC3 Transcription. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 12 (8), 691–699. 10.4161/cbt.12.8.15978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.; Hart C.; Tawadros T.; Ramani V.; Sangar V.; Lau M.; Clarke N. The Differential Effects of Statins on the Metastatic Behaviour of Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106 (10), 1689–1696. 10.1038/bjc.2012.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun M.; Foote C.; Lv J.; Neal B.; Patel A.; Nicholls S. J.; Grobbee D. E.; Cass A.; Chalmers J.; Perkovic V. Effects of Fibrates on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2010, 375 (9729), 1875–1884. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun M.; Foote C.; Lv J.; Neal B.; Patel A.; Nicholls S. J.; Grobbee D. E.; Cass A.; Chalmers J.; Perkovic V. Effects of Fibrates on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2010, 375 (9729), 1875–1884. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staels B.; Fruchart J. C. Therapeutic Roles of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Agonists. Diabetes 2005, 54 (8), 2460–2470. 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurora S.; Pizzimenti S.; Briatore F.; Fraioli A.; Maggio M.; Reffo P.; Ferretti C.; Dianzani M. U.; Barrera G. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Ligands Affect Growth-Related Gene Expression in Human Leukemic Cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305 (3), 932–942. 10.1124/jpet.103.049098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatena R.; Nocca G.; De Sole P.; Rumi C.; Puggioni P.; Remiddi F.; Bottoni P.; Ficarra S.; Giardina B. Bezafibrate as Differentiating Factor of Human Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Cell Death Differ. 1999, 6 (8), 781–787. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Zang C.; Fenner M. H.; Liu D.; Possinger K.; Koeffler H. P.; Elstner E. Growth Inhibition and Apoptosis in Human Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Lines by Treatment with the Dual PPARα/γ Ligand TZD18. Blood 2006, 107 (9), 3683–3692. 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio G.; Maggiora M.; Oraldi M.; Trombetta A.; Canuto R. A. PPARα and PP2A Are Involved in the Proapoptotic Effect of Conjugated Linoleic Acid on Human Hepatoma Cell Line SK-HEP-1. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121 (11), 2395–2401. 10.1002/ijc.23004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y.; Xin B.; Shigeto T.; Mizunuma H. Combination of Ciglitazone, a Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Ligand, and Cisplatin Enhances the Inhibition of Growth of Human Ovarian Cancers. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 137 (8), 1219–1228. 10.1007/s00432-011-0993-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahy D.; Kaipainen A.; Huang S.; Butterfield C. E.; Barnés C. M.; Fannon M.; Laforme A. M.; Chaponis D. M.; Folkman J.; Kieran M. W. PPARα Agonist Fenofibrate Suppresses Tumor Growth through Direct and Indirect Angiogenesis Inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105 (3), 985–990. 10.1073/pnas.0711281105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staels B.; Auwerx J. Regulation of Apo A-I Gene Expression by Fibrates. Atherosclerosis 1998, 137 (SUPPL), S19. 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X.; Wang G.; Zhou H.; Zheng Z.; Fu Y.; Cai L. Anticancer Properties of Fenofibrate: A Repurposing Use. J. Cancer 2018, 9 (9), 1527–1537. 10.7150/jca.24488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K.; Goswami S.; Sharma-Walia N. Implications of a Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha (PPARα) Ligand Clofibrate in Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (13), 15577–15599. 10.18632/oncotarget.6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Zhu C.; Qin C.; Tao T.; Li J.; Cheng G.; Li P.; Cao Q.; Meng X.; Ju X.; et al. Fenofibrate Down-Regulates the Expressions of Androgen Receptor (AR) and AR Target Genes and Induces Oxidative Stress in the Prostate Cancer Cell Line LNCaP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 432 (2), 320–325. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wybieralska E.; Szpak K.; Górecki A.; Bonarek P.; Miȩkus K.; Drukała J.; Majka M.; Reiss K.; Madeja Z.; Czyz J. Fenofibrate Attenuates Contact-Stimulated Cell Motility and Gap Junctional Coupling in DU-145 Human Prostate Cancer Cell Populations. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26 (2), 447–453. 10.3892/or.2011.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarczyk K.; Wybieralska E.; Baran J.; Borowczyk J.; Rybak P.; Kosińska M.; Włodarczyk A. J.; Michalik M.; Siedlar M.; Madeja Z.; et al. Fenofibrate Enhances Barrier Function of Endothelial Continuum within the Metastatic Niche of Prostate Cancer Cells. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2015, 19 (2), 163–176. 10.1517/14728222.2014.981153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong H. T. Β Blockers in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease. Br. Med. J. 2007, 334 (7600), 946–949. 10.1136/bmj.39185.440382.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja A. S.; Sadaoui N. C.; Lutgendorf S. K.; Ramondetta L. M.; Sood A. K. β-Blockers: A New Role in Cancer Chemotherapy?. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2013, 22 (11), 1359–1363. 10.1517/13543784.2013.825250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Li Y.; Li X.; Chen G.; Liang H.; Wu Y.; Tong J.; Ouyang W. Propranolol Attenuates Surgical Stress-Induced Elevation of the Regulatory T Cell Response in Patients Undergoing Radical Mastectomy. J. Immunol. 2016, 196 (8), 3460–3469. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. W.; Sood A. K. Molecular Pathways: Beta-Adrenergic Signaling in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18 (5), 1201–1206. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnon C.; Hall S. J.; Lin J.; Xue X.; Gerber L.; Freedland S. J.; Frenette P. S.. Autonomic Nerve Development Contributes to Prostate Cancer Progression. Science (80-.) 2013, 341 ( (6142), ). 10.1126/science.1236361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H.; Song T.; Kim T. H.; Choi J. K.; Park J. Y.; Yoon A.; Lee Y. Y.; Kim T. J.; Bae D. S.; Lee J. W.; et al. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Beta Blocker on Survival Time in Cancer Patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140 (7), 1179–1188. 10.1007/s00432-014-1658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S.; Griffith E. J.; Musto G.; Minuk G. Y. Antihypertensive Medications and Survival in Patients with Cancer: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 37 (6), 881–885. 10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zheng D.; Zhou T.; Song H.; Hulsurkar M.; Su N.; Liu Y.; Wang Z.; Shao L.; Ittmann M. Androgen Deprivation Promotes Neuroendocrine Differentiation and Angiogenesis through CREB-EZH2-TSP1 Pathway in Prostate Cancers. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 4080. 10.1038/s41467-018-06177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K.; Sharma A.; Mir M. C.; Drazba J. A.; Heston W. D.; Magi-Galluzzi C.; Hansel D.; Rubin B. P.; Klein E. A.; Almasan A. Autophagic Flux Determines Cell Death and Survival in Response to Apo2L/TRAIL (Dulanermin). Mol. Cancer 2014, 13 (1), 70. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohée L.; Peulen O.; Nusgens B.; Castronovo V.; Thiry M.; Colige A. C.; Deroanne C. F. Propranolol Sensitizes Prostate Cancer Cells to Glucose Metabolism Inhibition and Prevents Cancer Progression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 1–14. 10.1038/s41598-018-25340-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar S.; Alsharidah M. S. Are Beta Blockers New Potential Anticancer Agents?. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15 (22), 9567–9574. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.22.9567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grytli H. H.; Fagerland M. W.; Taskén K. A.; Fosså S. D.; Håheim L. L. Use of β-Blockers Is Associated with Prostate Cancer-Specific Survival in Prostate Cancer Patients on Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Prostate 2013, 73 (3), 250–260. 10.1002/pros.22564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig R. Therapeutic Use of Heparin beyond Anticoagulation. Curr. Drug Discovery Technol. 2009, 6 (4), 281–289. 10.2174/157016309789869001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccioli A.; Prandoni P.; Ewenstein B. M.; Goldhaber S. Z. Cancer and Venous Thromboembolism. Am. Heart J. 1996, 132 (4), 850–855. 10.1016/S0002-8703(96)90321-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrby K. Heparin and Angiogenesis: A Low-Molecular-Weight Fraction Inhibits and a High-Molecular-Weight Fraction Stimulates Angiogenesis Systemically. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2004, 23, 141–149. 10.1159/000216923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. B.; Mahon G. M.; Klinger M. B.; Kay R. J.; Symons M.; Der C. J.; Whitehead I. P. The Thrombin Receptor, PAR-1, Causes Transformation by Activation of Rho-Mediated Signaling Pathways. Oncogene 2001, 20 (16), 1953–1963. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa S. A.; Mohamed S. Inhibition of Endothelial Cell Tube Formation by the Low Molecular Weight Heparin, Tinzaparin, Is Mediated by Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 92 (3), 627–633. 10.1160/TH04-02-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson J. L.; Varki A.; Borsig L. Heparin Attenuates Metastasis Mainly Due to Inhibition of P- and L-Selectin, but Non-Anticoagulant Heparins Can Have Additional Effects. Thromb. Res. 2007, 120 (Suppl. 2), S107. 10.1016/S0049-3848(07)70138-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simka M. Anti-Metastatic Activity of Heparin Is Probably Associated with Modulation of SDF-1-CXCR4 Axis. Med. Hypotheses 2007, 69 (3), 709. 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-P. Heparin, Heparan Sulfate and Heparanase in Cancer: Remedy for Metastasis?. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8 (1), 64–76. 10.2174/187152008783330824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago J. R.; Lombard J. S. Metastasis in the Androgen-lnsensitive Nb Rat Prostatic Carcinoma System. J. Surg. Oncol. 1985, 28 (4), 252–256. 10.1002/jso.2930280403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatziapostolou M.; Polytarchou C.; Katsoris P.; Courty J.; Papadimitriou E. Heparin Affin Regulatory Peptide/Pleiotrophin Mediates Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Stimulatory Effects on Human Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (43), 32217–32226. 10.1074/jbc.M607104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto Y.; Ishii K.; Kanda H.; Kato M.; Miki M.; Kajiwara S.; Arima K.; Shiraishi T.; Sugimura Y. Combination Treatment with Naftopidil Increases the Efficacy of Radiotherapy in PC-3 Human Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143 (6), 933–939. 10.1007/s00432-017-2367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W.; Lin C.; Roberts M. J.; Waud W. R.; Piazza G. A.; Li Y. Niclosamide Suppresses Cancer Cell Growth by Inducing Wnt Co-Receptor LRP6 Degradation and Inhibiting the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. PLoS One 2011, 6 (12), 29290. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez B. B.; Ganju A.; Sikander M.; Kashyap V. K.; Hafeez Z.; Bin; Chauhan N.; Malik S.; Massey A. E.; Tripathi M. K.; Halaweish F. T.; et al. Ormeloxifene Suppresses Prostate Tumor Growth and Metastatic Phenotypes via Inhibition of Oncogenic β-Catenin Signaling and EMT Progression. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16 (10), 2267–2280. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan M.; Su L.; Yuan Y. C.; Li H.; Chow W. A. Nelfinavir and Nelfinavir Analogs Block Site-2 Protease Cleavage to Inhibit Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9698. 10.1038/srep09698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C.; Li B.; Yang Y.; Yang Y.; Li J.; Zhou Q.; Wen Y.; Zeng C.; Zheng L.; Zhang Q.; et al. Glipizide Suppresses Prostate Cancer Progression in the TRAMP Model by Inhibiting Angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27819–27819. 10.1038/srep27819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratskyi A.; Kondratska K.; Vanden Abeele F.; Gordienko D.; Dubois C.; Toillon R. A.; Slomianny C.; Lemière S.; Delcourt P.; Dewailly E.; et al. Ferroquine, the next Generation Antimalarial Drug, Has Antitumor Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 15896–15896. 10.1038/s41598-017-16154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. L.; Hsu L. C.; Leu W. J.; Chen C. S.; Guh J. H. Repurposing of Nitroxoline as a Potential Anticancer Agent against Human Prostate Cancer - A Crucial Role on AMPK/MTOR Signaling Pathway and the Interplay with Chk2 Activation. Oncotarget 2015, 6 (37), 39806–39820. 10.18632/oncotarget.5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]